Comptroller Stringer: Late Night Subway Service Drops 80% As Off-Peak Ridership Soars

Low-Wage Earners and Immigrants Stranded Most by Subway Crisis During Hours Outside “9 to 5”

Stringer Calls for Increased Service in the Early Morning and Evening and for the City to Immediately Fund the Lhota Emergency Plan

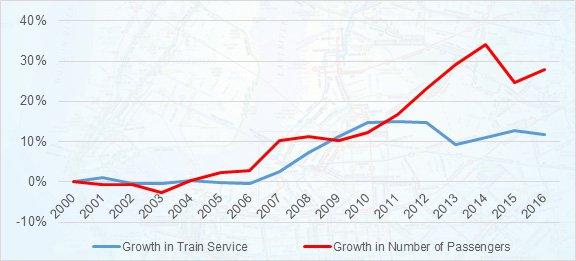

(New York, NY) — A new report by New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer released today revealed a new, less visible but deeply alarming aspect of the MTA subway crisis: the massive drop-off in “off-peak” service. Comptroller Stringer’s new report – “Left in the Dark: How the MTA is Failing to Keep Up with New York City’s Changing Economy” – illustrates that while commuting patterns across New York City have changed, subway service has not. Despite 57 percent of all job growth in the last decade happening in the healthcare, hospitality, retail, restaurant, and entertainment industries, MTA subway service has failed to adapt to spiking ridership among those who don’t work a traditional “9 to 5”. These massive drop-offs in after-hours service affects lower-income, New Yorkers of color, and immigrants most.

This new Comptroller Stringer analysis shows how New York City’s millions of service sector workers are being left in the dark by a subway system that isn’t just deteriorating during rush hours, but fundamentally failing to meet the needs of those who commute early in the morning and later into the evening. Today, the healthcare, hospitality, retail, food services, and entertainment industries account for 40 percent of private sector employment in New York City. Up until 2010, the MTA routinely added trains in the early morning to keep up with increasing ridership. Since the Great Recession, however, while ridership continued to surge between 5 a.m. and 7 a.m., the MTA did not respond accordingly—leaving riders to wait longer periods for trains that are more crowded.

Subway service to and from the Manhattan hub has not kept pace with growing ridership in the early morning (5 a.m. to 7 a.m.)

- In New York City, these commuting and work patterns have been changing for decades. In 1985, half of the daily ridership into the Manhattan central business district occurred between 7 a.m. to 9 a.m. By 2015, this share dropped to just 28 percent.

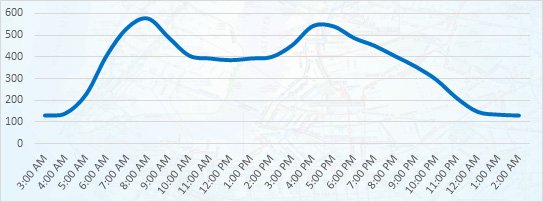

- Driven by the expansion of the city’s service sector, growth in tourism, and changing leisure patterns, off-peak subway ridership has rapidly expanded in the early mornings (5-7 a.m.) and evenings (7-11 p.m.). The MTA, however, has failed to respond to these trends. The MTA runs 60 percent fewer trains citywide from 5 a.m. to 6 a.m. than it does from 8 a.m. to 9 a.m., and 38 percent fewer from 9 p.m. to 10 p.m.

The number of trains beginning their route each hour

“During rush hour, we’re packed into subway cars like sardines. But outside traditional “9 to 5” travel, off-peak service is fundamentally failing to meet demand. It’s a crisis within a crisis, because over the past decade, the nature of our economy has changed and ridership late-nights and early mornings has risen while actual service to match it has not. That means that those who need service to get to work during non-traditional hours are stuck with a crisis not of overcrowding, but of infrequency,” Comptroller Stringer said. “We’ve looked at the human impacts of delays, the economic cost of slow-downs, and the crisis above ground with our bus system. Now, we’re showing how immigrants, New Yorkers of color, and lower-income neighbors are disproportionately affected by the off-peak subway crisis. The time for action is now. We need more service in the early morning and evening and we need to immediately fund the Lhota emergency plan to ensure those trains are actually running on time. Now more than ever, New York City needs to step up to support the MTA in this time of crisis.”

Off-Peak Service is Failing to Meet Demand

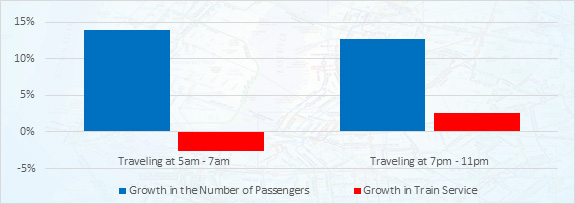

From 2010 to 2016, ridership in and out of the Manhattan hub jumped by 14 percent in the early morning and by 13 percent in the evening. The number of trains supplied by the MTA, however, did not keep pace, falling by three percent between 5 a.m. to 7 a.m. and rising by a meager three percent between 7 p.m. to 11 p.m.

Subway service in and out of the Manhattan hub did not keep pace with growing ridership in the early morning and evening from 2010 to 2016

Jobs during Non-Traditional Hours are Rising

Many jobs in New York’s growing service sector operate outside of the traditional 9-to-5, with employees serving customers, clients, and patients early in the morning and late into the evening. As these sectors have grown – adding more than 350,000 employees in the last decade – it has had a profound effect on commuting patterns and subway ridership.

The share of subway and bus commuters departing for work during “traditional hours” (7-9 a.m.) is falling

Those traveling to work off-peak now account for nearly half (47 percent) of all subway and bus commuters, up from 39 percent in 1990. Further, in the last quarter century, the number of transit commuters departing for work outside of “traditional hours” (from 5 a.m. to 7 a.m.) rose by 39 percent, while the number of “traditional” commuters grew by only 17 percent. That means demand for off-peak service is rising faster than demand for rush-hour service.

Yet service is dramatically diminished during early morning (5:30 a.m. to 6:30 a.m.) and later evening (8:30 p.m. to 10:30 p.m.) travel – just when many service sector workers depend on public transit. During these times:

- In the early morning, only 43 percent of train lines have wait times of less than 10 minutes and zero have wait times of less than five minutes.

- In the evening, under half of subway lines maintain wait times of less than 10 minutes and only 10 percent maintain frequencies of less than 5 minutes.

The problem is particularly acute in neighborhoods with significant retail, restaurant, health, hotel, and cultural employment.

- The neighborhoods most adversely impacted by infrequent train service include Lenox Hill-Roosevelt Island, East Harlem, Washington Heights South, Borough Park, Flushing, Forest Hills, Elmhurst, and Jamaica.

- These are neighborhoods with over 10,000 service sector jobs, which constitute more than half of total employment in the area, and receive 50% less subway service during the early morning (5:30-6:30 a.m) than in rush hour (7:30-8:30 a.m.).

Lower-Income New Yorkers Hurt Most by Subway Crisis

Those departing for work during “traditional” hours (7 a.m. to 9 a.m.) have very different economic profiles than “non-traditional” subway and bus commuters.

New Yorkers commuting between 5 a.m. and 7 a.m. earn $7,000 less than their rush hour counterparts and are more likely to be foreign born, a person of color, without a bachelor’s degree, and working in the service sector.

Economic Profile of Traditional and Non-Traditional Subway and Bus Commuters

| “Traditional” Commuters

(departs 7am-9am) |

“Non-Traditional” Commuters

(departs 5am-7am) |

|

| Median Income | $42,300 | $35,000 |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher (Age 25+) | 52% | 31% |

| Foreign Born | 47% | 56% |

| Person of Color | 64% | 78% |

| Work in Healthcare, Hospitality, Retail, Food Services, or Cultural industries | 36% | 40% |

| Growth in the Last Quarter Century | 39% | 17% |

###