Comptroller Stringer Proposal Would Allow Residents to Add Rent Data to Credit Histories and Boost Scores for Hundreds of Thousands of New Yorkers

First-of-its-kind analysis and “credit maps” show wide disparities in credit scores based on geography, ethnicity, and income

Report shows that 76% of participating NYC renters would see their credit scores rise if rent payments – the biggest monthly check most New Yorkers write – were factored in

Comptroller Stringer to launch new working group to break down barriers to rent reporting and calls on City to take steps forward

(New York, NY) — New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer today released a report and never-before-done analysis that shows deep disparities in credit scores across the City – and proposes pioneering solutions to help mitigate the problem. The report – “Making Rent Count: How NYC Tenants Can Lift Credit Scores and Save Money” – uses proprietary data to illustrate how an alarming number of New Yorkers have limited or no access to credit. That is a challenge that can limit participation in the broader economy and put a ceiling on individuals’ financial success. As such, Comptroller Stringer is proposing ways to help New York City tenants have their monthly rent payments count toward their credit scores, just like mortgage payments do for homeowners. The analysis shows that if rent were incorporated into credit histories, hundreds of thousands of New York City residents who opted in would see their scores increase – and secure better, consumer-friendly rates for loans, car leases, and more.

Credit scores — which are used to measure the likelihood that an individual will pay back a debt — pull together a number of different data streams from consumers’ individual profiles, including whether they have made timely payments on credit cards, mortgages, and auto loans. Currently, however, most credit scores fail to capture an individual’s positive rental history, and instead are more often used by landlords to report late payments by tenants. To correct that imbalance, the Comptroller’s proposals seek to empower tenants by allowing them to “opt in” to strategies that could allow regular rent payments to count toward their credit scores for the first time.

“When millions of New Yorkers pay their rent on time, they should get credit for it, just like when homeowners pay their mortgage. Allowing New Yorkers’ rent history to boost their credit scores is a simple solution to a real, long-standing problem afflicting New Yorkers, and it’s another way to whittle away at our affordability crisis,” said New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer. “If you’re low-income and don’t have credit, this is a commonsense solution that would help. With New York City becoming increasingly unaffordable, we have a chance to mitigate that massive challenge and make it easier for residents to get by. This is a smart approach that can help millions of New Yorkers raise their credit scores and as a result, pay less on their loans, car payments, and more. That’s why we’re planning to launch a working group with engage stakeholders from across New York to develop and implement strategies to give tenants a leg up.”

The Comptroller’s first-of-its-kind analysis underscores the many potential benefits of incorporating rent payments into credit histories for the City’s 5.4 million renters. Drawing on never before released proprietary data, the Comptroller’s Office studied a representative sample of city tenants paying rents under $2,000 and found that reporting rent history would:

- Raise credit scores for 76 percent of New York City renters who currently hold a credit score. Specifically:

- More than half (57%) would see their score rise between 1 and 10 points;

- Nearly one in five (19%) would have their score boosted by 11 points or more;

- 18 percent would see no change at all;

- Just 6 percent would see a decline in their scores.

- Provide nearly 30 percent of renters with a credit score for the first time. The average new score for these mostly low-income renters – now categorized as “invisible” or “unscorable” because of the relative dearth of financial information in their credit files — would be a prime score of 700.

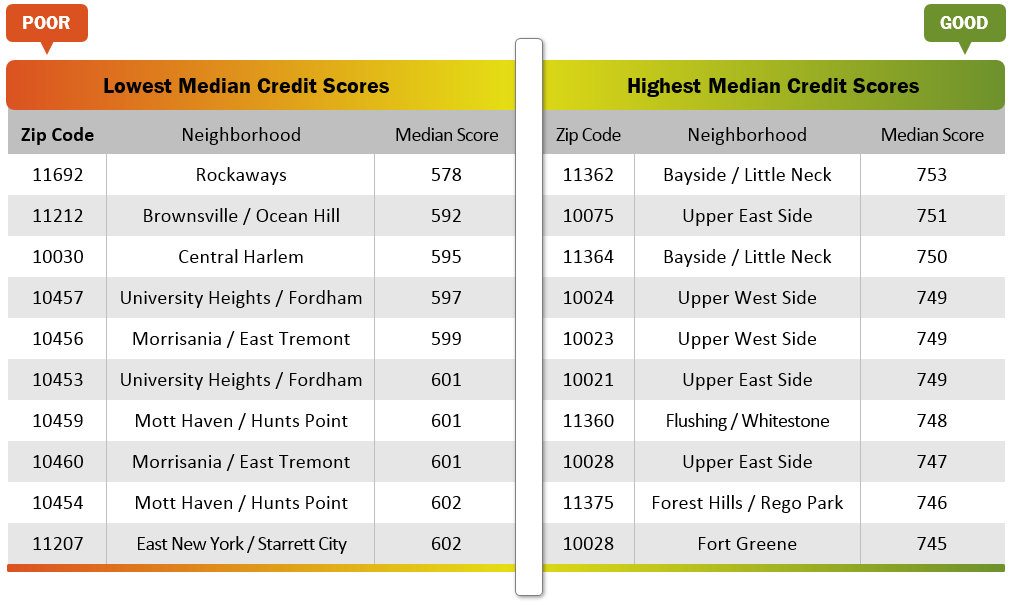

The Comptroller’s analysis also provides a new “credit map” of New York City that shows deep disparities by neighborhood. While the average credit score in New York City is 673 — considered a “prime” score — low median credit scores are concentrated in pockets of Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx, while higher scores are found in Manhattan, Staten Island, and portions of Northeast Queens.

Median Credit Score

By New York City Zip Codes

Mean VantageScore 3.0

To view this data in an interactive map, click here.

The report includes a breakdown of those communities with the lowest and highest median credit scores in New York City. In general, those communities with higher home ownership and car ownership rates – two key drivers of credit scores – boast higher average credit scores, among them Bayside/Little Neck in Queens, and the Upper East and Upper West Sides of Manhattan.

Similarly, the report found a real connection in New York City between low credit scores and factors like race, income level and home ownership rates. In communities where the average credit score is below 630:

- More than 78 percent of residents rent their homes, compared to just 54 percent in neighborhoods where the average credit score is above 700 rent.

- Black and Hispanic New Yorkers account for more than 90 percent of the population.

- NYCHA residents comprise one in ten residents.

- Individuals have an average annual income of roughly $34,500, compared to an average income of $52,500 in communities with mean credit scores of 700 or above.

As part of the report, the Comptroller’s Office used anonymized data from three actual renters of different means in New York City to show how adding rental data to their credit files could lift their scores. One tenant, who regularly pays her $1,300 a month rent, saw her score rise from 650 to 675 – a jump from a non-prime to a prime score. Another tenant – with a limited credit history – saw a rise from 657 to 714 after rental history was factored in.

From housing to finance, an individual’s credit score can be the deciding factor between being denied a loan or securing a good rate, or between having a rental application rejected or put at the top of the pile. In short, a low credit score condemns an individual to worse loan terms, pricier credit cards and insurance policies, and higher utility bills. For example:

- A family with a non-prime credit score applying for a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage on an average-priced home in the Bronx would pay as much as $150,000 more over the life of the loan than a family with a higher credit score.

- A New Yorker with a subprime credit score who received a 36-month, $20,000 auto-loan could end up paying more than $3,700 more than if he or she had a prime credit score.

- An individual with a subprime credit score could pay as much as 91 percent more for home insurance than a consumer with a high score. Similarly, auto insurance premiums could be as much as $1,700 more expensive per year for a driver with poor credit.

The Comptroller’s report also suggests a number of policy changes that would make it easier for New Yorkers to report their history of paying rent in-full and on time to credit bureaus. Proposals include:

- Helping landlords and property managers provide opt-in programs that give tenants the option to let their landlord report rent payment information to credit bureaus. The City should explore policies to incentivize these programs.

- Urging banks and credit unions to leverage innovative strategies to identify rent payments and report them to credit bureaus. Suggestions include:

- Serving as an intermediary where the bank or credit union collects rent checks, verifies them against a lease, reports them to a credit bureau, and then sends the payment to the landlord for those New Yorkers who opt in;

- Offering microloan programs, where the bank or credit union pays a tenants’ full lease, and then collects monthly loan payments from the tenant. For those individuals who opt in, this would be reported to credit bureaus as a standard loan, boosting the tenant’s credit score.

Comptroller Stringer is also urging the City to take a number of steps, including:

- Allowing all NYCHA residents to opt in to a credit reporting program. That could be done by expanding an existing pilot partnership NYCHA has with the Brooklyn Cooperative Federal Credit Union and Urban Upbound Federal Credit Union, which allows tenants to opt-in to report their rent payments to credit bureaus. That program could be scaled to the entire housing system.

- Exploring incorporating rent into its affordable housing programs by incentivizing and informing developers of affordable housing about ways to develop a rent-reporting program.

- Proactively using its Department of Consumer Affairs to develop credit building curriculums which assist renters considering opting into a rent reporting program.

- Implementing a number of credit related consumer protections, including adjusting credit scoring models so that credit checks undertaken by landlords on prospective tenants will not negatively impact credit scores.

- Passing legislation to require landlords who run credit checks on prospective tenants to share credit reports with the applicant and increase consumer credit education initiatives offered by the City.

While not every credit score would be impacted by allowing rent to factor into credit (since not all credit-scoring models incorporate rent in their algorithms and formulas), new models such as FICO 9 and Vantage Score 3.0 do factor rent payments into an individual’s credit profile.

###