Creating a Chief Diversity Officer

New York City’s diverse communities are the cornerstone of our city’s economy. Indeed, our city is home to 3.3 million foreign-born immigrants from 150 countries who make up almost 40 percent of the city’s population and collectively earn about $100 billion annually.[1] What’s more, the almost 540,000 minority-owned businesses and over 413,000 women-owned businesses who collectively employ over 600,000 New Yorkers create jobs and opportunities in every corner of the five boroughs.[2] And, women, who make up almost half of the entire New York City workforce, collectively earn about $100 billion annually.[3] Embracing and investing in this diversity is critical to the foundations of our economy.

Despite these contributions, too many people in these communities still face daunting challenges. For instance, women in New York City are confronted with a persistent wage gap—the difference in average earnings between women and men—that is largest in highly paid occupations, and is most severe for women of color.[4] Across the city, income inequality has grown more severe in the last decade while new job creation has been concentrated most heavily in low-wage industries.[5] Younger New Yorkers, particularly Black and Hispanic residents, were hit hard by the 2008 recession, and the millennial generation is earning less than their counterparts who entered the job market in previous decades.[6] Finally, in many of the city’s economically growing neighborhoods, people of color continue to face significant disparities in finding employment.[7]

Addressing these persistent challenges must be a significant focus of City government and the newly created City Charter Review Commission. For our city to reach its full potential, inclusion must be more than a buzzword. All New Yorkers, whether they have lived in our city for fifty days or fifty years, need to be able to realize their dreams in the city we all call home.

The City possesses a powerful tool to help address these disparities as the purchaser of goods and services. In Fiscal Year (FY) 2017, New York City spent $21 billion of taxpayer money to procure items ranging from pens and paper to food, consulting and legal services. If used effectively, these dollars are a way that the City can help to create new businesses, grow job opportunities, and build wealth in communities across the five boroughs.

However, as the Office of the Comptroller has documented in each of the last four years, when the City purchases goods and services, very little of its business is done with women- or minority-owned firms (M/WBE’s) covered by the City’s M/WBE procurement program.[8] Furthermore, the City’s M/WBE program fails to reach the many businesses owned by historically disadvantaged groups not currently covered by the City’s M/WBE program, including businesses owned by people with disabilities, LGBTQ+ individuals, veterans, and Native Americans. As a result, the City is missing an opportunity to more fully invest in its businesses, build wealth in local communities, and foster competitive procurements that ensure taxpayer dollars are spent most efficiently.

The City’s M/WBE program is governed by Local Law 1 of 2013, which as shown in Chart 1 below, establishes procurement goals in various categories based on race, gender, and business type. As this chart shows, for instance, the City has a goal of awarding 8 percent of its construction contracts to Black-owned businesses.

Chart 1: Procurement Goals under Local Law 1

| Procurement Category | Construction | Professional Services | Standard Services | Goods |

| Black American (BA) | 8% | 12% | 12% | 7% |

| Asian American (AA) | 8% | No Goal | 3% | 8% |

| Hispanic American (HA) | 4% | 8% | 6% | 5% |

| Women (W) | 18% | 17% | 10% | 25% |

Source: Local Law 1 Target Spending Percent.

However, as a whole, the City is falling far short of these goals. Indeed, Chart 2 below documents that the City failed to reach a single one of these goals in FY 2017. In fact, since 2014 when the Comptroller’s Office began its annual evaluation of the City’s M/WBE program, the City has failed to reach any one of these goals in any single year.

Chart 2: FY2017 NYC Performance in Meeting Local Law 1 Procurement Goals

| Procurement Category | Construction | Professional Services | Standard Services | Goods |

| Black American (BA) | 0.67% | 0.88% | 1.14% | 1.17% |

| Asian American (AA) | 3.03% | 8.79% | 2.47% | 1.70% |

| Hispanic American (HA) | 1.45% | 1.76% | 0.59% | 1.62% |

| Women (W) | 3.59% | 3.95% | 3.79% | 6.26% |

Source: New York City Comptroller’s FY2017 Making the Grade report.

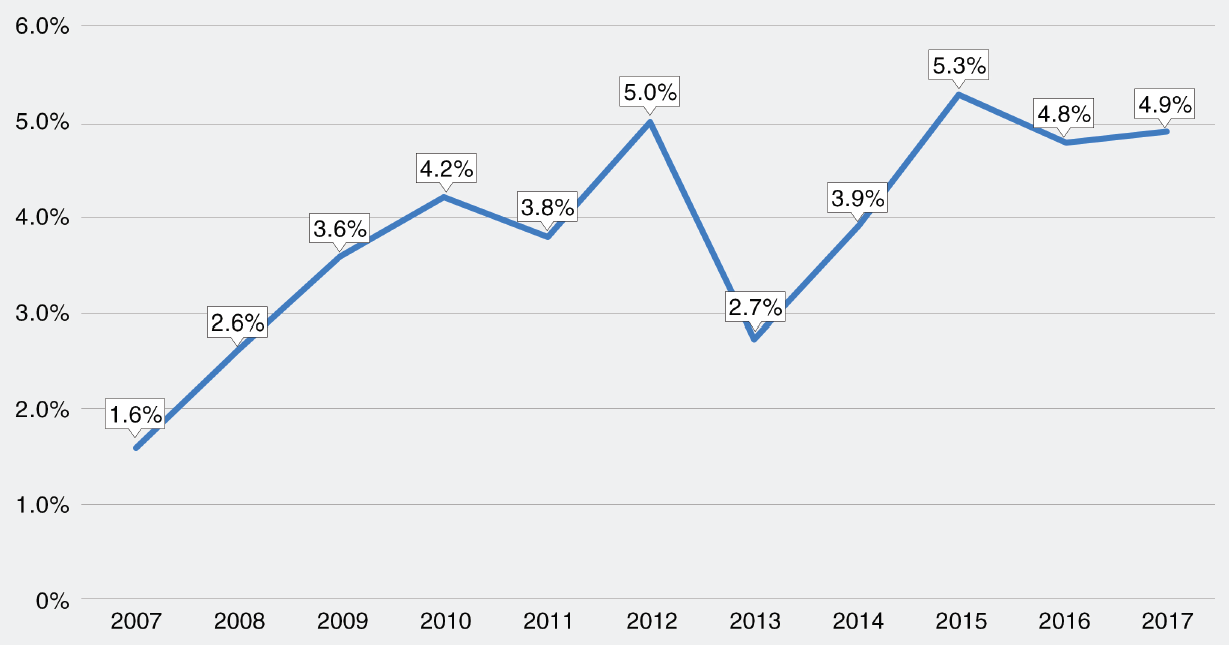

Consistent with the failure to achieve the goals set by Local Law 1, M/WBE firms have historically been awarded a very small share of City contracts. As shown in Chart 3 below, at no point in the last decade has the share of City procurement awarded to M/WBE’s exceeded 5.3 percent, and in FY 2017 less than 5 percent of City contracts were awarded to women- and minority-owned businesses.

Chart 3: M/WBE Share of City Procurement, FY 2007 – FY 2017

Source: Mayor’s Office of Contract Services Agency Procurement Indicators: Fiscal Years 2007 to 2017, and OneNYC: Minority and Women-Owned Business Enterprise Bulletin, Sept. 2015.

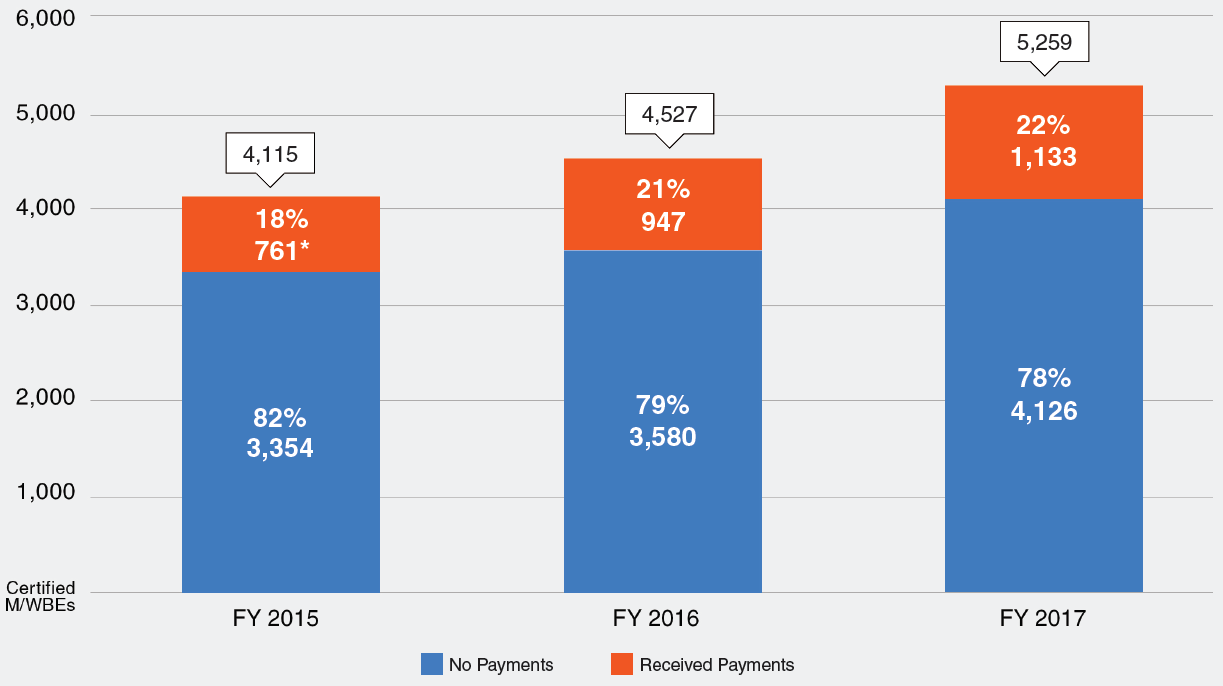

Similarly, while the City has made progress to increase the number of M/WBE firms who are “certified” with the City, little has been done to increase the share of these firms who actually receive City funds. Chart 4 documents that less than a quarter of M/WBE firms who certify with the City’s Department of Small Business Services received payments in each of the last three years.

Chart 4: Certified M/WBEs Receiving Spending: FY 2015, FY 2016, and FY 2017

Source: New York City Comptroller’s FY2017 Making the Grade report.

In recent years, the Mayor has set new goals for the City’s M/WBE program. The City’s current goal is to award $16 billion to M/WBEs by 2025, allocate 30 percent of contracts to M/WBEs by 2021, and grow the number of certified firms to 9,000 by 2019.[9] While these commitments are laudable, given the historical challenges with this program, more structural reforms are needed to ensure that the M/WBE program reaches its important objectives.

Enhancements to the City Charter would help to bolster this program and eliminate barriers that have traditionally prohibited M/WBEs from being awarded a contract with New York City. Currently, under Section 1304 of the City Charter, the City’s M/WBE program is housed in the Department of Small Business Services. That same section of the Charter requires each City agency head to implement an M/WBE program at their agency, and also requires them to designate a senior staff member to advise the agency head on the M/WBE program. In addition to these Charter mandates, as a matter of practice, this Mayor has appointed a senior advisor in the Mayor’s Office to provide high-level support for the M/WBE program.

However, nothing in the City Charter requires that that Mayor’s Office directly assist in the operation of the M/WBE program, and the lack of a Mayoral mandate means that the program may not consistently receive attention at the highest levels of government. Moreover, while agencies are required to make a senior executive responsible for advising the agency head on the program, the implementation of this requirement has been mixed.

To address this shortcoming, the City Charter should be amended to establish a position of Chief Diversity Officer (CDO) within the Office of the Mayor. The CDO would have responsibility for overseeing the entire M/WBE program across all City agencies by improving coordination, sharing best practices, promoting accountability, and ensuring compliance across City agencies so that the program is meeting the City’s goals. The CDO would also ensure that the City’s procurement program is reaching other communities, including people with disabilities, LGBTQ+ New Yorkers, veterans, and Native Americans.

In addition, the Charter should further be amended to require each City agency to designate an agency-level CDO who reports directly to the agency head and who also is accountable to the City’s CDO. Where it has been properly structured, agency level CDO’s have helped to improve their agency’s M/WBE program. For instance, at the Department of Design and Construction, the creation of a well-resourced CDO has helped increase the agency’s M/WBE spending by $470 million.[10] Similarly, in the Office of the Comptroller, the CDO has helped the agency almost double spending with M/WBEs to over 24 percent of its annual procurement spending in FY 2017. In the Comptroller’s Office, the CDO is focused on implementing the agency’s M/WBE program, and to that end is empowered to work directly with department heads to inform procurement decisions, track agency spending, and conduct targeted outreach to current and prospective vendors during the procurement process. While the Comptroller’s Office CDO would not report to the City’s CDO given that the Comptroller’s Office is independent of the mayoral administration, the responsibilities and duties of the Comptroller’s CDO are a model that should be adopted across all City agencies.

Enshrining these policies in the City Charter would help ensure their success and sustainability. As the City’s constitution, the Charter is a statement about the priorities of the local government and a foundation for its policies. By grounding oversight of the M/WBE program and executive employment disparities in the Mayor’s Cabinet, and doing the same at each agency, these reforms would demonstrate the importance of women, people of color, and other historically disadvantaged groups having a seat at the table and provide a single venue for New Yorkers to hold City officials accountable for meeting their goals.

The City Charter should be amended to create the position of Chief Diversity Officer inside the Mayor’s cabinet. The Chief Diversity Officer would be responsible for holding agencies accountable for effectively implementing their individual M/WBE programs, promoting best practices across agencies, and encouraging M/WBEs to bid on City procurement solicitations in addition to finding diverse talent for the City of New York. In addition, the CDO would ensure Citywide accountability for the inclusion of women and people of color.

The City Charter should further be amended to clarify that each agency head should appoint an agency Chief Diversity Officer, whose full-time responsibility would be overseeing agency implementation of the M/WBE program, tracking and measuring diverse talent for the agency, and ensuring accountability for the inclusion of women and people of color.

Giving Communities a Stronger Voice in Land Use Decisions

Decisions about how our land is used is at the core of city government. With our city confronting an affordability crisis driven by a lack of affordable housing and a local government that too often fails to listen to the voices of local residents feeling that crisis most acutely, reforms to local land use policy are urgently needed. While many changes to land use regulations and the processes by which they are approved should be considered for reform—including ways to make the process more efficient, predictable, and responsive to community concerns—many of these changes would more appropriately occur through either agency regulations or changes to the zoning resolution. However, there are many steps that the City should take through reforming the Charter that will better empower communities, encourage sound planning, and strengthen the overall Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) process.

Empowering Community-Based Planning

The following reforms would, in tandem, enhance the ability of local communities to make better informed planning decisions and ensure that the City includes the views of local stakeholders when making decisions that impact residents.

Strengthen Community Boards with Urban Planning Expertise

Community Boards were originally established as Community Planning Councils by Manhattan Borough President Robert F. Wagner in 1951 to conduct comprehensive community-based planning for the growth of the city. In 1975, the Charter Revision Commission extended Community Boards citywide, with 59 Community Boards representing the same number of districts. The Charter revision aimed to decentralize service delivery and make the new Community Boards into what Mayor John Lindsay had called “little city halls.” It ensured that service delivery, such as parks and sanitation, was coterminous with Community Boards, established district service cabinets, and officially created the district manager position. In addition, it gave Community Boards other advisory functions such as budget analysis, capital needs recommendations, oversight of City service delivery, and the creation of district needs assessments.

While the Charter laid the groundwork for local planning through the creation of ULURP (Uniform Land Use Review Procedure) and 197-a plans, it was not until the 1989 Charter Revision Commission that these powers were fully expanded. Specifically, the new Charter required the City Planning Commission to define and adopt rules regarding the review of 197-a plans, gave Community Board representatives the right to attend meetings regarding the environmental impact of proposed land use proposals, and gave boards the power to make recommendations relating to the opening and closing of City facilities. And most importantly, the new structure highlighted the role of Community Boards in ULURP as the local focal point for responding to zoning changes.

Consequently, Community Boards were endowed with dual mandates of both focusing on service delivery for local residents and responding to land use planning issues in their districts. Historically, however, due to limited resources, proactive planning often took a back seat to service delivery.

Yet much has changed since Community Boards were first directed to oversee service delivery. Indeed, since that time, many other elected officials began to professionalize their operations, including through the creation of district offices and hiring of professional staff to respond to constituent needs. As a result, today, constituent services are effectively delivered by a host of government actors including City Council members and Assembly members who have full-time district offices. In addition, with the advent of 311 in 2003, New Yorkers have more places than ever to report noise complaints or get potholes filled.

Therefore, rather than continuing to focus on constituent services, Community Boards should be empowered to better fulfill their intended role as neighborhood planning bodies. As the current development boom reaches deeper into the boroughs, affordable housing has become increasingly scarce, and our transit system is bursting at the seams – neighborhood-based planning that takes the diverse needs of local communities into account is more essential than ever. With Community Boards working more as partners, the City might be more successful in gaining community buy-in for large re-zonings, siting shelters, and moving forward a host of other initiatives to help our city stay fair and affordable for the people who helped build the very neighborhoods that are now targets for development.

Community Boards, however, have historically lacked the resources, capacity and expertise to fulfill their community planning role in a consistently meaningful way. Indeed, community boards face challenges in their ability to adequately review and analyze land use matters due to a lack of resources and expertise. Most boards do not have trained urban planners on staff, and must therefore rely on their volunteer members to analyze land use proposals and to develop recommendations. And yet they are expected to argue their positions against $800 an hour lawyers hired by major developers in front of the City Planning Commission.

As first proposed by Comptroller Stringer in 2010 when he was Manhattan Borough President, Community Boards should be required to have a full-time urban planner on staff to help shape future development on a local level and address the real needs of the neighborhood. The sole responsibility of this planner would be to support the board’s analysis in developing recommendations on land use matters and to coordinate community-based planning activities. The expertise of the urban planner would better enable Community Boards to conduct comprehensive community planning, leveling the playing field between community boards and developers.

The City Charter should be amended to require that Community Boards hire a full-time qualified urban planner with a degree in urban planning, architecture, real estate development, public policy or similar discipline and include the necessary budget appropriations to fund this position. Community Boards require dedicated support and expertise to fulfill their purpose of conducting community-based planning.

Increase the Impact of Community Generated Plans

Currently, the only mechanism for community members to make their own planning decisions is found in section 197-A of the City Charter, which authorizes community boards to propose plans for the development, growth, and improvement of their local community. But, while the Charter allows these plans to be proposed, in reality they have been relatively rare. Indeed, since 1989 only 12 community board-generated 197-A plans have been approved and none since 2009.[11]

A major reason why 197-A plans have been infrequent is that they require significant time and resources for community boards, who often do not have the time, capacity, or expertise available to develop the plans. Other reforms discussed in this section, including providing each community board with an urban planner and creating an Independent Long-Term Planning Office that can work directly with community boards and other local stakeholders, will address these particular hurdles.

But, in addition to these reforms, the City Charter should be modified to ensure that community plans are meaningfully followed once implemented. To do so, the Charter should require that 197-A plans be submitted to all relevant City agencies, require the agencies to formally review, respond to, and integrate the plans as much as possible in their policies. Further, if a City agency believes that it needs to take action that would depart from an approved 197-A plan, the agency should be required to justify that action in writing with an opportunity for the community board and public to respond. Finally, all ULURP actions should also require consideration of integrating 197-A plans when practicable and any inconsistencies should be formally justified in the application materials.

The City Charter should be amended to strengthen 197-A plans by not only requiring that agencies integrate the plans into their policies, but also that any deviation from the plan by either a private actor in public review or an agency should be justified in writing.

Create a Centralized Development Database

Following the City’s land use decision making process is not a simple task, even for the most informed member of the public. Doing so requires a member of the public to have the time and knowledge needed to track the websites of multiple City agencies, read and understand complex City documents, and attend public hearings. For New Yorkers who are already overworked and may have family and other commitments, the amount of time and work it takes to engage in the City’s land use processes is a deterrent to civic participation.

For instance, to determine when and where public discussions and relevant meetings are occurring that pertain to a project involving a “simple” ULURP action, a concerned citizen would need to review multiple information sources, including community board websites as well as those of the City Planning Commission and the City Council. A more complex approval process may also include multiple hearings at the Landmarks Preservation Commission or Board of Standards and Appeals. Further, if a member of the public wants to track the status of a challenge to whether a development is in compliance with the zoning code, that New Yorker must each day check an individual construction site’s landing page on the Department of Buildings’ website. This requires both knowledge of the process, awareness of the zoning challenge process and time to regularly check for an opportunity to comment.

To overcome these challenges, the City Charter should require that the City create and maintain a centralized website for the posting of public notices for hearings and meetings on land use matters being considered by the City Planning Commission, Landmarks and Preservation Commission, Board of Standards and Appeals, Department of Buildings, and any other body making land use decisions. The hearings and/or meetings should be at minimum searchable by date, type of action, project name, and community district. Doing so would facilitate public participation in the land use process by making it easier for the public to obtain notices and other information about land use matters, track the status of a single project or multiple projects, and share their views, which will ultimately improve public participation and the outcomes of land use decisions.

The City Charter should be amended to require the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications (DOITT) to maintain a website that allows the public to easily search for all land use matters under consideration in the City.

Update Fair Share Requirements

Section 203 of the New York City Charter requires that the City Planning Commission propose rules relating to the siting of city facilities, known as “Fair Share” rules. The intent of these rules are to ensure that City facilities are fairly distributed throughout the boroughs in order to ameliorate historic environmental inequities.

However, a 2017 report by the New York City Council found that the current fair share rules are failing to accomplish this goal. Indeed, according to the report, low-income communities and communities of color still see far more than their fair share of City facilities that are harmful or burdensome to the local community. In addition, the report found that data on City facilities is difficult to access, local community residents and community boards are often not aware of new facilities being sited in their community, and that there are few to no consequences or mitigation required if a facility is sited in contravention of fair share rules.[12]

Unfortunately, since the release of this report, little action has occurred by City agencies to reform their fair share analysis. In fact, no significant changes have been made to the rules since their creation in 1991.

As such, the City Charter should be modified to require that the City Planning Commission review and update fair share criteria every five years. As part of this process, any proposals to update the criteria should be shared with community boards and borough presidents for comment and subject to a vote by the City Planning Commission. In addition, the Commission should utilize the newly proposed Independent Long-Term Planning Office, discussed in more detail below, to help analyze the concentration of City services to advise on the communities that are oversaturated and inappropriate for future facility sitings.

The City Charter should be amended to require that the City Planning Commission regularly review and update “fair share” requirements no less than every five years.

Reforming Land Use Agencies

The City’s land use process could be improved with the creation of new agencies focused on long-term planning and sustainably developing vacant City-owned property while also reforming the governance of existing agencies.

Encourage Comprehensive Long-Term Planning

Comprehensive planning is a basic tool used by local governments for assessing needs, providing a framework for growth and development, and informing public policy. For instance, in late 2017, the City of London released the “London Plan,” which serves as the “overall strategic plan for London.” To this end, the London Plan provides an “integrated economic, environmental, transport and social framework for the development of London over the next 20-25 years.”[13]

While used in London and elsewhere, this type of comprehensive planning is unfortunately lacking in New York City where responsibility for long-term planning is divided among multiple agencies and no single agency has the authority to direct another agency’s planning actions. Specifically, while discrete zoning and land use policies are developed and evaluated by the Department of City Planning and the City Planning Commission, other elements that are typical to comprehensive planning are handled separately by other City agencies. For example, most transportation planning is conducted by the Department of Transportation; the Department of Parks and Recreation is largely responsible for open space planning; economic development is under the purview of the Mayor’s Office and the Economic Development Corporation; and for the most part, the City’s housing policy is set by the Department of Housing Preservation and Development. Furthermore, each individual agency is responsible for its own capital planning process in the 10-year capital plan. In addition to the work of these City agencies, outside actors like the Regional Plan Association provide context and support for infrastructure planning across the entire New York City region.

The lack of coordinated comprehensive long-term planning makes it difficult for communities across the City to engage with government agencies, evaluate future plans, and ensure that their priorities are reflected in planning decisions. Indeed, these gaps have created a crisis of confidence in many neighborhoods, where local residents no longer trust that government planners have a sufficient framework in place to synthesize community needs and concerns with a broader policy vision. As a result, when the City does undertake more comprehensive planning efforts, such as the large area rezoning plans for East New York or Jerome Avenue, the plans may be incomplete and unsuccessful because mayoral goals may not align with community priorities and inadequate mechanisms exist for integrating community input.

As a result, the City’s current system of planning should be reformed to offer more support for the ability of communities, government representatives, and City agencies to evaluate and make intelligent decisions and to envision the larger purpose and cumulative impact of individual proposals. To do so, the City Charter should establish a new Independent Long-Term Planning Office (ILTPO), with a primary duty of generating a citywide comprehensive plan based on agency needs, citywide development goals, mayoral policies, borough presidents’ Strategic Policy Statements, and community board plans. To be successful, the ILTPO should have the following features:

Independence – The independence of the ILTPO will provide it with the credibility necessary to establish a comprehensive plan while bringing together the perspectives of disparate agencies, similar to the existing Independent Budget Office (“IBO”). Like the IBO, the ILTPO would perform independent analysis for communities and elected officials. Funding for this organization should come from reductions of redundant staffing levels at City agencies, currently responsible for the production of the plans required by the City Charter that would no longer be necessary. The appointment of an ILTPO director should follow the same format as that for the IBO director, who is appointed by a committee of elected officials.

Dissemination of Information – In order to provide sufficient context for the development of a comprehensive citywide plan, City agencies must be mandated by the Charter to provide the ILTPO with information on existing conditions such as as-of-right developments; any known environmental, economic, social service, land use and zoning impacts; and long-term agency needs and goals. The ILTPO would use this information to generate the citywide plan and to assist community boards in developing District Needs Statements and other community-based planning documents.

Ratification of comprehensive plan – To ensure that the comprehensive plan truly represents New York City’s interests and is formally adopted as policy, the ILTPO’s comprehensive plan must be ratified through a public review process. The Charter should establish a process similar to what exists currently in ULURP for reviewing and adopting the comprehensive citywide plan. Community boards and the borough presidents should have the power to review and make recommendations on the plan, and the City Council should have the authority to amend and adopt the plan. The mayor should review the plan and alter it as needed. As with ULURP, if the mayor alters any city council action, the Council should have the authority to overturn the mayoral changes with a vote by two-thirds of the city council.

The City Charter should be amended to establish an Independent Long-Term Planning Office to conduct comprehensive planning for the City of New York and the resulting plan should be ratified by the City Council through a public process.

Create a New York City Land Bank

Addressing New York City’s affordable housing crisis requires using all of the tools at the City’s disposal to build and preserve truly affordable housing. But, for too long the City has left a proven solution out of its toolkit by failing to turn vacant City-owned land and tax delinquent properties into permanently affordable housing.

According to a 2016 audit from the Comptroller’s Office, the City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development controls more than a thousand vacant lots that could potentially be developed for affordable housing. The audit further found that 75 percent of these have been owned by the City for more than 30 years without being developed or otherwise disposed of.[14] A follow up audit, released in 2018, found that these problems persist, despite the agency’s contention that it was in the process of transferring or disposing of many of these vacant lots.[15]

To date, New York City’s primary strategy for developing affordable housing on city-owned lots has been to sell the property to a developer in exchange for a percentage of affordable units for a limited duration. While this model has facilitated the creation of thousands of affordable units, the City loses leverage by transferring title, which weakens its ability to hold developers accountable and negotiate for deeper and permanent affordability.

For this reason, Comptroller Stringer has called on the City to create a new model based around the creation of a New York City Land Bank. Under this new model, the City would:

- Transfer property to a land bank that would be ‘seeded’ with City-owned vacant land to be developed into affordable housing.

- The land bank would then put together a package of subsidies and identify a developer, in most instances a non-profit, with whom to partner. Because these developers do not have the primary goal of making a profit, this partnership would allow for the creation of more housing for lower-income New Yorkers than the current system.

- Finally, instead of selling the land to a developer, the land bank would enter into a long-term lease with a developer, allowing the City to enforce affordability and ensure that the affordability is permanent.

- In addition to City-owned properties, the New York City Land Bank would also have the ability to target tax-delinquent vacant properties that it could seek to foreclose upon more quickly than the current system.

The Comptroller’s analysis of how a land bank could be used to develop vacant City-owned land found that a New York City Land Bank focused just on the City’s vacant lots and a smaller sub-set of vacant properties that have failed to pay taxes for multiple years could support the development of more than 57,000 units of permanently affordable units.[16]

Therefore, to realize these benefits, the City Charter should be changed to require the creation of a Land Bank with the mission of constructing permanent affordable housing on blighted city and privately-owned vacant properties.

The City Charter should be amended to create a New York City Land Bank.

Reform the Landmarks Preservation Commission and Board of Standards and Appeals

The decision on how to use land is among the most important functions of City government, requiring the input of diverse stakeholders across City government and the public. And yet, two City agencies with significant roles in land use decisions are overseen by appointed representatives that are accountable to only one public official. As described by Comptroller Stringer in 2010, these agencies are in need of governance reforms to increase their political independence and ensure they are a better able to respond to broader constituencies.

The Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) is responsible for designating landmarks and historic districts across the city and approving any modifications of landmarked structures or historic districts. The Commission consists of 11 members, all of whom are appointed by the mayor. According to the Charter, certain appointees are required to have certain qualifications (three architects, one qualified historian, one city planner or landscape architect, and one realtor) and must represent all five boroughs. While LPC has made important progress to eliminate its backlog in recent years and the Council has passed legislation establishing timelines under which LPC must consider landmark applications, accountability would improve with more systemic reforms.[17]

The Board of Standards and Appeals (BSA) is responsible for issuing special permits, considering appeals to construction-related laws, and approving variances from the Zoning Code. Under the Charter, BSA is governed by five mayoral appointees who must include one planner, one architect, and one professional engineer. No more than two appointees can reside in any one borough. As with LPC, the Council recently adopted a number of reforms to increase transparency and improve operations of BSA.[18]

Fortunately, the City Charter already provides an alternative governance structure for land use agencies through the City Planning Commission (CPC) that ensures mayoral control while building in additional layers of accountability. Under the Charter, the CPC is a thirteen-member body in which the chair and six commissioners are appointed by the mayor, one commissioner is appointed by the public advocate, and each borough president also makes one appointment. All commissioners other than the chair are subject to the advice and consent of the council and are chosen based on their “independence, integrity and civic commitment.” Adopting this type of governance structure can better ensure that there is robust public accountability across all City boards and commissions that oversee land use matters.

The City Charter should be amended to create new governance structures for the Landmarks Preservation Commission. While the majority of commissioners and board members should continue to be appointed by the mayor, the public advocate and each borough president should also be responsible for making appointments, as is done currently on the City Planning Commission.

The City Charter should be amended to create new governance structures for the Board of Standards and Appeals. While the majority of commissioners and board members should continue to be appointed by the mayor, the public advocate and each borough president should also be responsible for making appointments, as is done currently on the City Planning Commission.

Improving Environmental Impact Statements

Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) play a critical role in the City’s land use process. But these long, dense, and costly documents that explain the potential harms of a land use action and ways to limit those adverse impacts are too often inaccessible for the public. The changes discussed below would improve the way that EIS’s are used in the City’s land use decisions.

Ensure Funding for Environmental Impact Statements

Pursuant to section 201 of the New York City Charter, community boards, borough boards, borough presidents, and the land use committee of the city council may file for changes in zoning. This portion of the charter is essential for advancing community generated zoning plans. However, this authority is rendered moot for many of the bodies as state and city law requires that environmental reviews be conducted for any such proposal. These reviews can be expensive, costing millions of dollars that these bodies do not have the budget to pay for.

To address this shortcoming, the City Charter should require the creation of an environmental review fund that would allow these elected officials and boards to fulfill their mission. The funds could be dispersed by the Independent Long-Term Planning office, recommended above or, absent its creation, the City Council.

The City Charter should be amended to create an Environmental Impact Statement Review Fund, which would be managed by the Independent Long-Term Planning office or absent its creation the City Council. The Fund would disperse monies needed by a community board or borough president necessary to conduct an environmental review, which are prerequisites to their charter granted abilities to sponsor ULURPs.

Improve the Metrics Used in Environmental Impact Statements

The purpose of an EIS is to identify any adverse environmental impacts of a proposed land use action, which could include harms to the natural environment, displacement of local residents, or increased school crowding, and identify steps to mitigate those harms. However, historically, residents facing new development have raised concern that the metrics used to analyze potential environmental impacts are incorrect.

Currently, section 192(e) of the City Charter requires the City Planning Commission to oversee the implementation of laws relating to environmental reviews of actions taken by the City, which includes developing the types of metrics studied in EIS’s. While these metrics are determined through the City’s rule-making process that includes a public comment period, that process can be opaque and is generally controlled by the City agency issuing the rule.

To provide the public with greater opportunity to weigh in on the metrics used in EIS’s, the City Charter should be updated to create a public process for reviewing the City Environmental Quality Review framework. This process should include public hearings in each borough and be held at least every five years. Furthermore, the City should establish a commission with members appointed by both the Mayor and the City Council to evaluate the metrics used in EIS’s and any proposed changes to those metrics that result from public review.

The City Charter should be amended to require the City Planning Commission to regularly update the metrics used in Environmental Impact Statements based on the input of the public and a newly created commission of experts.

Release Environmental Impact Statements Sooner for Larger Projects

Currently, EIS’s—which range from being a few hundred pages to thousands of pages—are released at the start of the ULURP process and, over the length of that process, are then converted from their draft form to their final form at the time of the City Planning Commission vote. Among the steps in the ULURP process that occur between the release of a draft EIS and the completion of the final EIS are a community board hearing and vote, borough president review, and a City Planning Commission hearing and vote. This whole process can last no more than 150 days, and for the community board at most 60 days.

While the process may provide a suitable amount of time for the public to review a draft EIS for a relatively standard project, this timeframe is inappropriate for major projects. For example, the Hudson Yards rezoning has an eight volume EIS that total over 6,600 pages while the East New York rezoning, which added less density then Hudson Yards, included an EIS that totaled over 5,200 pages with appendices. This is a significant amount of dense technical reading for both the average member of the public and elected stakeholders to read in a few months.

In order to allow the public and elected officials time to review and understand the potential impacts of major projects, any project that comprises at least 1.5 acres, the minimum size of a large-scale general development per the zoning resolution, the City Charter should mandate that draft EIS’s pertaining to major projects be released at least 60 days prior to a ULURP application being certified by the City Planning Commission.

The City Charter should require that draft Environmental Impact Statements for major projects be released at least 60 days before a ULURP application may be certified by the City Planning Commission.

Strengthening the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP)

The 1976 Charter Revision Commission established the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP). At that time, however, the process was limited to zoning changes. Thirteen years later, as part of the 1989 Charter Revision, the list of actions subject to ULURP has been expanded in recognition of the impact that land use actions other than zoning changes have on the type, density, and height of development, as well as demands on City services. The 2019 Charter Revision Commission should once again use the opportunity to review and improve ULURP, including in the ways discussed below.

Include Zoning Text Amendments in ULURP

Zoning text establishes the rules for use and development of property within zoning districts designated on the zoning map, and as such, amendments to the zoning text present significant policy determinations that warrant public review. For example, the Zoning for Quality and Affordability text, which was described as “one of the most significant updates to the Zoning Resolution in decades,” affected building heights, density for affordable senior housing, reduced parking, and altered rules relating to building design and street frontage. While in this case the administration chose to follow a ULURP-like timeline in getting the text approved, they were not bound to adhere to that timeframe.

That is the case because under the current system, the City Charter only requires that the City Planning Commission notify community boards and borough boards of a text change and be provided with an opportunity to testify at a public hearing with as little as ten days’ notice. While in practice the City Planning Commission typically shares proposed text amendments for 30 to 60 days with community boards, which affords the local community board an opportunity to hold public hearings and vote on a proposed text change, they are not required to do so. However, text amendments could radically change the laws governing development and, therefore, should go through ULRUP. Consequently, the City

Charter should be revised to require full ULURP review for zoning text changes.

The City Charter should require full ULRUP review for zoning text changes.

Certain Licenses Provided by the City Should be Subject to ULURP

Pursuant to section 197-c of the City Charter, acquisition of real property (other than office space) by the City is required to go through ULURP. Acquisition can include the purchase, condemnation, exchange or lease of any real property. However, this provision of the Charter does not include the issuance of licenses, which are valuable tools as they, unlike leases, can generally be entered into for a short period and canceled without penalty. Unfortunately, not including licenses in the ULURP review, can result in public review of important land use decisions being circumvented.

For example, in 2005, the Department of Sanitation received the approval to build a new sanitation garage in Brooklyn. Unfortunately, the funds were cut from the budget and work stopped on the new garage. In 2010, the Sanitation Department sought City approval through ULURP to maintain the existing garages at 525 Johnson Avenue and 145 Randolph Street. But, due to community opposition, the applications were withdrawn at the City Council. Since that time, and despite the Council declining to act on the applications, 8 years later the garages are still in use as a result of the use of licenses. Fortunately, the Department of Sanitation has committed to the Comptroller’s Office to advance a new ULURP application for these two sites.

This process demonstrates that the licensing process can be used to circumvent the public review process and should be reformed. In order to provide City agencies continued flexibility in the use of temporary space, but to prevent abuse of a loophole, the City Charter should be modified to require that licenses lasting more than 5 years go through ULURP.

The City Charter should require that licenses lasting for more than five years be subject to ULRUP review.

Restrict the City Planning Commission from Overruling Local Stakeholders in ULURP Voting

The City Charter provides that the community and borough perspective be significant factors in shaping land use outcomes for the mutual benefit of local communities and the city as a whole. To this end, the Charter provides community boards and borough presidents with the ability to make advisory recommendations on ULURP applications to the City Planning Commission, bringing in local perspectives to improve the projects. Furthermore, ULURP requires that the City Planning Commission provide a written explanation whenever it modifies or disapproves of a community board or borough president recommendation.

The City Planning Commission is a 13-member body composed of seven members selected by the Mayor, one member selected by each borough president, and one selected by the Public Advocate. As such, if the seven Mayoral appointees choose to move forward with a project despite the local community board and borough president registering objections, they can do so without any additional support from other borough presidents or the Public Advocate.

The important, beneficial role of the borough president and community board in improving land use actions should be strengthened to ensure serious consideration of their recommendations by citywide bodies and land use applicants. To that end, the City Charter should require that a supermajority of City Planning Commissioners—nine commissioners instead of seven—be needed to approve an application that has been disapproved by both the community board and borough president. This would require at least two non-mayoral appointees to vote in favor of the action to overcome the objections of the local community and borough. This voting system has a precedent in the Charter in the nine votes that are required to approve site selections for which the borough president and community board both have recommended disapproval and the borough president has identified an alternative site within the subject borough.

The City Charter should be amended to require that any City Planning Commission approval of an application that has previously been disapproved by the local community board and borough president be approved by a supermajority of commissioners.

Disposal of City-Owned Air Rights Should be Subject to ULURP

The disposition of air rights is similar to the disposition of City-owned land, but unlike the disposition of land, it is not subject to ULURP. The transfer of City-owned air rights usually results in new, larger developments that create demands on City services, increase intensity of land uses, and present significant policy issues. As such, when the City disposes air rights that it owns, that disposal should be covered by ULURP.

For example, the City had acquired a property at 35 East 4th Street for the Third Water Tunnel. During negotiations for acquisition, the City decided to sell air rights associated with 35 East 4th Street parcel to an adjacent property. Revenue derived from the transfer of these air rights was intended primarily to offset the acquisition costs for the tunnel site, and facilitate the creation of a new pocket park on the unused portion of the 35 East 4th Street parcel. No public review occurred for the sale of air rights. While the public was generally in favor of these benefits, the sale also resulted in the construction of a building at 39 East 4th Street that is larger than it otherwise could have been. While the local community was concerned about the size of the new proposed building, there was no opportunity to publicly weigh the impacts of selling the air rights.

The Charter Revision Commission should recommend that the disposition of City-owned air rights undergo full ULURP review and approval similar to the disposition of City-owned land. In order to regulate the City’s disposition of air rights, mergers of City-owned zoning lots with privately owned zoning lots should be included in the list of actions requiring ULURP in section 197-c of the Charter.

The City Charter should require the disposal of City-owned air rights to go through ULURP.

The Disposal of Property through Local Development Corporations Should go through ULURP

New York City requires the acquisition and disposition of City-owned property to be subject to public review through ULURP. Entities that are controlled by New York City that are not city agencies, however, do not require such review. The amount of properties potentially purchased and sold through these entities without significant public review is antithetical to the intentions of the Charter.

The challenges this situation poses can be seen most clearly in the case of the New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC), which manages 66 million square feet of real estate and nearly $2.5 billion in City and non-City funds.[19] EDC’s land use decisions are not necessarily subject to ULURP.

For example, in 2016 EDC purchased four sites in the Bronx as part of an effort to encourage their redevelopment, although there was not a specific plan for their use. To that end, two of the sites were purchased above their appraised value based on the justification that the sites could reach the appraised value if converted to market rate housing. However, using any of these four sites for housing will require a rezoning, meaning that if no rezoning occurs then the City will not be able to sell the sites at their purchase price and City funds could potentially be wasted. Critically, because these sites were purchased by EDC, no ULURP was needed and therefore no public review occurred that would enable a robust discussion of whether purchasing these sites was in the best interest of the City.[20]

This entire process has occurred without community consultation through the normal public review process. To date, no ULURP has been filed for a rezoning. Simply put, the current process has resulted in an unclear development plan for properties purchased by the City without public review that may require a rezoning, and could result in the City wasting tax dollars. The requirement that City acquisition of real property go through ULURP is specifically intended to prevent these types of scenarios.

As such, purchases of real property by local development corporations with affiliations to New York City should be required to go through the ULURP process.

The City Charter should require that land purchases by local development corporations with affiliations to New York City be subject to ULURP.

Deed Restriction Removals Should be Covered by ULURP

One of the ways that the City exercises the control of property that it has previously sold is by imposing a restriction on the use of that property in its deed. While the City allows the owner of that property to pay the City to remove that deed restriction, the action of removing the deed restriction in exchange for payment is not uniformly covered by ULURP. This shortcoming should be addressed by subjecting all deed restriction removals to ULURP.

Much has been written about the Rivington House deed restriction outlining the failures of the way the City removes or alters deed restrictions previously placed on properties by the City.[21] In response to these failures, the City Council has passed new legislation to make the review process more robust by requiring notice to local communities, a public hearing, and review by two deputy mayors, heads of agencies, and ultimately the mayor.[22] While this process is undoubtedly better than the previous process, it does not provide the same type of thorough review as is done through the ULURP process because it removes the length and depth of the public review normally associated with ULURP, does not provide the City Council with a vote on the project, and prevents the public from multiple chances to influence the ultimate decision.

Subjecting all deed restriction removals to ULURP would also reduce the ambiguity that currently exists when ULURP is actually required. Generally, if a property enters into ULURP for a restricted sale and the Council approves the restrictions, then a change in the deed restriction will likely need to go back through ULURP. However, generally, if the subject site goes through ULURP for an unrestricted sale then no ULURP is necessary to remove the deed restriction. Addressing this inconsistency would ensure that all deed restriction removals would be considered in the same way.

Therefore, the City Charter should be modified to require all changes in deed restrictions to go through the ULURP modification process. Based on the existing rules that distinguish between major and minor changes to previously approved applications, this process would require major changes to go through a full ULURP, with approvals by the City Council.[23] However minor changes could be referred out to the community board and borough president, with a hearing and vote by the city planning commission.

The City Charter should stipulate that deed restriction removals be subject to ULURP.

Reporting Data on the City’s Hiring of People with Disabilities

New York City is home to almost 1 million people with disabilities. Although laws protect them from discrimination, they continue to face economic challenges at much higher rates than people without disabilities.[24] Indeed, according to the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities, median household income for disabled New Yorkers is only $22,020 annually (compared to over $55,000 annually for the total population). The poverty rate for people with disabilities is 31 percent (compared to 20 percent for the population overall).[25] A critical reason is that people with disabilities face persistent barriers in employment; in 2016 the employment rate of working-age people with disabilities in New York State in 2016 was only 33 percent.[26]

To provide greater employment opportunities for people with disabilities, in 2010 President Obama signed Executive Order 13548. It set a goal for the federal government of employing an additional 100,000 people with disabilities over 5 years.[27] The Obama Administration announced in September 2016 that it had met this goal, hiring almost 110,000 part-time and full-time employees with disabilities between FY2011 and FY2015.[28]

But it is unclear how much New York City as an employer recruits and hires people with disabilities in its own workforce. While the City Charter requires the Department of Citywide Administrative Services to publish an annual report on the government workforce—as part of efforts to ensure equal employment opportunities for women and people of color—the report provides no data on the number of municipal workers with disabilities. Including that information in the annual report would help the City evaluate its performance in employing people with disabilities and determine how it can adopt practices to become a better employer for all New Yorkers.

The City Charter should be amended to require that the Department of Citywide Administrative Services annual report on the City’s equal employment practices include data on the City’s hiring of people with disabilities.

Eliminating the Phrase “Mental Retardation” from the City Charter

In 2010, the U.S. Congress passed “Rosa’s Law,” which replaced the term “mental retardation” in various federal statutes with the phrase “intellectual disability.” This was done in light of the fact that the phrase “mental retardation” is “anachronistic, needlessly insensitive and stigmatizing, and clinically outdated.”[29] However, while the federal government has taken these steps, the City of New York has not done so. Currently, the term “mental retardation” appears multiple times in the City Charter, including seven times in Section 15 of the Charter and 12 times in Chapter 22. It also appears in multiple places in the City’s Rules and Administrative Code. The phrase should be removed and replaced in all places where it appears in City law, including the Charter.

The City Charter should be revised to replace the term “mental retardation” and its various iterations with the phrase “intellectual and/or developmental disability.” Similar changes should also be made to the Administrative Code and City Rules.

Performing an Annual Analysis of Pay Disparities in the Municipal Workforce

New York City’s women are a powerful force in the local economy, making up about half of all workers and contributing almost $100 billion in annual earnings to the economy. This is particularly true for the municipal workforce, where sixty percent of employees are women, with almost two-thirds being women of color. These official figures neglect the countless hours of unpaid work that New York City women put in every year caring for children, aging parents, and loved ones in addition to building their local communities.[30]

And yet, as documented by the Comptroller’s Office, New York City women continue to face a persistent gender wage gap that sees them earning less than their male counterparts, with harmful long-term consequences.[31] More recent research from the Comptroller’s Office has documented the gender wage gap—the difference in average earnings between women and men—across occupation and race. Importantly, this analysis found that the gender wage gap is largest among the highest paying occupations and that the gender wage gap is most severely felt by women of color.[32] For instance, in 2016, Black women working full-time in New York City made 57 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men, or roughly $32,000 less per year.[33] A recent analysis of City payroll data by the Public Advocate’s Office highlighted that women in the municipal workforce are similarly underrepresented in higher-paying jobs, contributing to disparities in earnings across gender.[34]

The City has recently adopted policies to confront the gender wage gap, including requirements that prohibit New York City employers (including the City itself) from asking prospective employees about their salary history. Still, more must be done to understand the extent of the City gender pay gap and develop thoughtful strategies to close it.

To this end, the City should evaluate municipal pay disparities each year, and publicize its findings. Currently, the City Charter authorizes the Department of Citywide Administrative Services to issue an annual report on the city government workforce and the equal employment policies of each city agency. But that report is not required to include an analysis of wage disparities within the City workforce. Requiring DCAS to conduct such an analysis, in consultation with the Human Rights Commission and other relevant agencies, would force the City to focus on these issues more aggressively and would bolster accountability.

The City Charter should be amended to require the Department of Citywide Administrative Services to include an analysis of wage disparities within the municipal workforce, disaggregated by gender and race, as part of its annual workforce profile report. In doing so, the Charter should require the agency to consult with the Commission on Human Rights and the Equal Employment Practices Commission.

[1] New York City Comptroller, “Our Immigrant Population Helps Power NYC Economy,” January 2017: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/our-immigrant-population-helps-power-nyc-economy/.

[2] New York City Comptroller, “Making the Grade:” https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/making-the-grade/overview/.

[3] New York City Comptroller, “Power and the Gender Wage Gap: How Pay Disparities Differ by Race and Occupation in New York City,” April 2018: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/power-and-the-gender-wage-gap-how-pay-disparities-differ-by-race-and-occupation-in-new-york-city/.

[4] New York City Comptroller, “Power and the Gender Wage Gap: How Pay Disparities Differ by Race and Occupation in New York City,” April 2018: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/power-and-the-gender-wage-gap-how-pay-disparities-differ-by-race-and-occupation-in-new-york-city/.

[5] New York City Independent Budget Office, “How has the Distribution of Income in New York City Changed Since 2006,” April 2017: http://ibo.nyc.ny.us/cgi-park2/2017/04/how-has-the-distribution-of-income-in-new-york-city-changed-since-2006/. New York City Comptroller, “Comments on New York City’s Preliminary Budget for Fiscal Year 2019 and Financial Plan for Fiscal Years 2018-2022,” March 2018: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/comments-on-new-york-citys-preliminary-budget-for-fiscal-year-2019-and-financial-plan-for-fiscal-years-2018-2022/.

[6] New York City Comptroller, “New York City Millennials in Recession and Recovery,” April 2016: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/new-york-citys-millennials-in-recession-and-recovery/.

[7] New York City Comptroller, “The New Geography of Jobs: A Blueprint for Strengthening NYC Neighborhoods,” April 2017: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/the-new-geography-of-jobs-a-blueprint-for-strengthening-nyc-neighborhoods/.

[8] New York City Comptroller, “Making the Grade:” https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/making-the-grade/overview/.

[9] Mayor de Blasio Announces Bold New Vision for the City’s M/WBE Program, September 2016: https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/775-16/mayor-de-blasio-bold-new-vision-the-city-s-m-wbe-program/#/0. De Blasio Administration Reaches 5,000 City-Certified M/WBEs, May 2017: https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/343-17/de-blasio-administration-reaches-5-000-city-certified-m-wbes.

[10] New York City Comptroller, “Making the Grade: New York City Agency Report Card on Minority- and Women-Owned Business Enterprises,” November 2017: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/Making-the-Grade-2017.pdf.

[11] New York City Department of City Planning: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/community/community-based-planning.page.

[12] New York City Council, “Doing our Fair Share, Getting our Fair Share,” February 2017: https://council.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/2017-Fair-Share-Report.pdf.

[13] Mayor of London, “The London Plan: The Spatial Development Strategy for Great London Draft for Public Consultation,” December 2017: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/new_london_plan_december_2017.pdf.

[14] New York City Comptroller, “Audit Report on the Development of City-Owned Vacant Lots by the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development,” February 2016: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/audit-report-on-the-development-of-city-owned-vacant-lots-by-the-new-york-city-department-of-housing-preservation-and-development/.

[15] New York City Comptroller, “Final Letter Report on the Follow-up Review of the Development of City-Owned Vacant Lots by the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development,” February 2018: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/final-letter-report-on-the-follow-up-review-of-the-development-of-city-owned-vacant-lots-by-the-new-york-city-department-of-housing-preservation-and-development/.

[16] New York City Comptroller, “Building an Affordable Future: The Promise of a New York City Land Bank,” February 2016: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/The_Case_for_A_New_York_City_Land_Bank.pdf.

[17] New York City Council, Int. 0775-2015: http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=2271110&GUID=A66556A6-1DEA-4D5F-8535-92C31B2B2379&Options=ID|Text|&Search=landmark. New York City Landmarks and Preservation Commission: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/lpc/designations/backlog-initiative.page.

[18] “Mayor de Blasio Signs Legislation to Better Promote Safety, Fairness and Transparency for All New Yorkers,” May 30, 2017: http://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/373-17/mayor-de-blasio-signs-legislation-better-promote-safety-fairness-transparency-all-new.

[19] New York City Council, “Report of the Finance Division on the Fiscal 2019 Preliminary Budget and the Fiscal 2018 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report for the Economic Development Corporation,” March 9, 2018: https://council.nyc.gov/budget/wp-content/uploads/sites/54/2018/03/FY19-Economic-Development-Corporation.pdf.

[20] EDC purchased 1047 Home Street, Block 3006 Lot 21 for $800,000 but the property was appraised to only be worth $540,000 with the current zoning. Though its value would be $1,800,000 with a rezoning if used for market rate housing. 1051 Home Street, Block 3006, Lot 9, was purchased for $1,200,000 but appraised for $325,000. Though its value as market rate housing would be $1,400,000. See the following New York City Economic Development Corporation documents: https://www.nycedc.com/sites/default/files/filemanager/EDC_Board_of_Directors_Minutes_9-30-16.pdf https://www.nycedc.com/sites/default/files/filemanager/About_NYCEDC/Financial_and_Public_Documents/NYCEDC_Board_of_Directors_Meeting_Minutes/EDC_Board_Minutes_2-10-2016.pdf https://www.nycedc.com/sites/default/files/filemanager/Minutes_of_the_Regular_Meeting_of_the_Board_of_Directors_8-2-16.pdf.

[21] New York City Comptroller, “Report on the Sale of Two Deed Restrictions Governing Property Located at 45 Rivington Street,” August 2016: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/report-of-the-new-york-city-comptroller-on-the-sale-of-two-deed-restrictions-governing-property-located-at-45-rivington-street/.

[22] New York City Council, Int 1182-2016: http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=2735475&GUID=C514BD10-3BCE-4529-B12B-2C345CD4C387.

[23] New York City Department of City Planning: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/applicants/applicant-portal/step3-non-ulurp-cm-followup.page.

[24] New York City Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities, “New York City People with Disabilities Statistics,” 2016: http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/mopd/downloads/pdf/selected-characteristics-disabled-population.pdf.

[25] New York City Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities, “New York City People with Disabilities Statistics,” 2016: http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/mopd/downloads/pdf/selected-characteristics-disabled-population.pdf. U.S. Census Bureau, Quick Facts New York City: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/newyorkcitynewyork/PST045216.

[26] Cornell University, “2016 Disability Status Report, New York:” http://www.disabilitystatistics.org/StatusReports/2016-PDF/2016-StatusReport_NY.pdf?CFID=8045832&CFTOKEN=555eeea6aacdc1f7-200BB1A7-9378-2208-10AB9649F79EF9FB.

[27] Executive Order 13548 – Increasing Federal Employment of Individuals with Disabilities, July 26, 2010: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/executive-order-increasing-federal-employment-individuals-with-disabilities.

[28] “Federal Disability Employment Annual Report FY15,” September 22, 2016: https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/diversity-and-inclusion/reports/disability-report-fy2015.pdf.

[29] Public Law 111-256, https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-111publ256/html/PLAW-111publ256.htm. S. Rept. 111-244 – Rosa’s Law, August 3, 2010: https://www.congress.gov/congressional-report/111th-congress/senate-report/244/1.

[30] New York City Comptroller, “Power and the Gender Wage Gap: How Pay Disparities Differ by Race and Occupation in New York City,” April 2018: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/power-and-the-gender-wage-gap-how-pay-disparities-differ-by-race-and-occupation-in-new-york-city/.

[31] New York City Comptroller, “Gender and the Wage Gap in New York City,” April 2014: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/gender-and-the-wage-gap-in-new-york-city/.

[32] New York City Comptroller, “Power and the Gender Wage Gap: How Pay Disparities Differ by Race and Occupation in New York City,” April 2018: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/power-and-the-gender-wage-gap-how-pay-disparities-differ-by-race-and-occupation-in-new-york-city/.

[33] New York City Comptroller, “Inside the Gender Wage Gap, Part 1: Earnings of Black Women in New York City,” August 2018: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/inside-the-gender-wage-gap-part-i-earnings-of-black-women-in-new-york-city/.

[34] New York City Public Advocate, “Tipping the Scales: Wage and Hiring Inequity in New York City Agencies,” March 2018: https://pubadvocate.nyc.gov/sites/advocate.nyc.gov/files/agency_wage_hiring_report-final.pdf.