Addressing the Harms of Prohibition: What NYC Can do to Support an Equitable Cannabis Industry

Over the last several decades, the prohibition of cannabis has had devastating impacts on communities in New York City, extending beyond incarceration to often long-lasting economic insecurity: damaged credit, loss of employment, housing, student loans, and more. Today, thousands of New Yorkers, overwhelmingly Black and Latinx, continue to endure the untold financial and social costs of marijuana-related enforcement, despite steps to decriminalize.[i] As New York joins neighboring jurisdictions in moving closer to legalizing cannabis for adult use, the State and the City must take action to ensure that the communities who have been most harmed by policies of the past are able to access the revenue, jobs, and opportunities that a regulated adult-use marijuana program would inevitably generate.

While the creation of a legal market brings the promise of new wealth, the uneven enforcement of marijuana policies in New York specifically and the lack of diversity in the cannabis industry generally foreshadow potential inequities in who will benefit—and, indeed, who will profit—from a legal adult-use cannabis industry. In anticipation of future legalization, this report, by New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, offers a new neighborhood-by-neighborhood look at cannabis enforcement and charts a roadmap for building equity into the industry.

Utilizing U.S. Census Bureau data and New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services data on the number of marijuana-related arrests in New York City between 2010 and 2017, the Comptroller’s Office identified the neighborhoods in the city that experienced the highest rates of arrest. The analysis shows that disparities in marijuana enforcement exist across not only race and ethnicity but also socioeconomic lines, with the neighborhoods with the highest arrest rates tending to be lower income, having higher unemployment, lower credit scores, and lower rates of home ownership. Specifically, this report finds:

- The Brooklyn neighborhood of Brownsville and Ocean Hill has the highest average marijuana-related arrest rate by far during the period, followed by East New York and Starrett City, also in Brooklyn; Concourse, Highbridge, and Mount Eden in the Bronx; and Washington Heights, Inwood, and Marble Hill and East Harlem in Manhattan.

- The marijuana-related arrest rate in East Harlem is 13 times higher than on the Upper East Side, underscoring the significant disparities even among adjoining neighborhoods.

- Seven of the 10 lowest-income neighborhoods in the city, based on median household income, fall among the top 10 for marijuana-related arrest rate and account for more than one-third (34.3 percent) of all such arrests. The 10 highest-income neighborhoods account for only one-tenth (11.0 percent) of all arrests.

- The average poverty rate among the ten highest-ranking neighborhoods by marijuana-related arrest rate is 32.5 percent, far exceeding the citywide poverty rate of 18.9 percent and more than double the rate among the bottom ten (14.3 percent).

- In four of the five highest-ranking neighborhoods by marijuana-related arrest rate, the unemployment rate exceeds 10 percent; citywide, the unemployment rate is half that (5.2 percent).

- Among the 10 highest-ranking neighborhoods, roughly one in 10 homes are owner-occupied (homeownership rate of 11.4 percent), compared to one in two homes among the 10 lowest-ranking neighborhoods (51.5 percent).

- Marijuana-related arrest rate tracks closely with credit score, with Brownsville having both the highest arrest rate and lowest median credit score (598) in the city.

Together, the report findings show that the neighborhoods most impacted by prohibition are among the most economically insecure and disenfranchised in the city. It is precisely these New Yorkers then—those to whom the benefits of legalization should be targeted—who are most likely to face barriers to accessing opportunities in the industry, in particular financing. In addition to reinvesting tax revenue from legalization in these disproportionally impacted communities, steps should therefore be taken to equip those impacted by prohibition to secure the funding and other resources needed to become cannabis licensees. This report recommends that the City, in partnership with the State, develop a robust cannabis equity program to direct capital and technical assistance to impacted communities interested in participating in the adult-use industry.

Landscape for Legalization

Since 2014, when New York’s medical marijuana program was established, New York State legislators have introduced bills to also legalize marijuana for adult use, citing, among other justifications, the cost and ineffectiveness of enforcement and the damage prohibition has done to communities of color. While the primary bill, the Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act (MRTA), has not yet passed either the Assembly or the Senate, support for legalization has grown exponentially in the past 12 months.

Earlier this year, at the governor’s direction, the New York State Department of Health conducted an impact assessment of an adult-use marijuana program and released a comprehensive report in July, which concluded that the benefits outweigh any potential risks and that the State should move forward with legalization.[ii] Subsequently, the governor formed a workgroup to solicit community input across the state and make recommendations on legislation.[iii] These developments, combined with those in neighboring states and in Canada, make it likely that a legalization bill will land on the governor’s desk in the near-term, possibly as early as the 2019 legislative session.[iv]

The potential to raise hundreds of millions of dollars in tax revenue to help meet community needs is certainly an attractive benefit to legalization. In May 2018, the Comptroller’s Office released a report that assessed the fiscal impact of creating a legal, regulated adult-use marijuana program in New York. Based on the size of the legal markets in Colorado and Washington, the states in which marijuana sales have been legal the longest, the Comptroller’s Office estimated the adult-use market at $3.1 billion per year in New York, with about $1.1 billion of that in New York City. The market could generate roughly $436 million at the state level and an additional $336 million in New York City in annual tax revenue.[v] The report highlighted other benefits to legalization as well, including cost savings in the form of reduced police and court costs as well as the potential reduction in the use of opioids, as more New Yorkers switch to cannabis to treat pain.

While Comptroller Stringer supports legalization for all of these reasons, legalizing and taxing cannabis alone is not a sufficient path forward. Legalization must also provide for reclassification of past marijuana-related convictions and resentencing of those currently incarcerated for a related offense, both of which the pending New York State bill, the MRTA, includes. Additionally, the tax revenue that legalization would generate should be invested in the communities that have been most impacted by prohibition. To achieve this, the MRTA, for example, would direct 50 percent of tax revenue to a Community Grants Reinvestment Fund that would award funding to community-based organizations providing certain services designed to support those formerly incarcerated, including job placement, adult education, mental health treatment, and substance abuse treatment.[vi] While community input should be embedded in the development of such a fund, it is critical that historical data on marijuana enforcement also inform this process.

Roadmap for Repairing Harms

Repairing the harms of prohibition requires knowing who has been most harmed, and that starts with tracking enforcement activity. While the racial and ethnic disparities in enforcement are well documented, other characteristics are less well known, and limited public data on who has been arrested for marijuana-related offenses exist. Because the consequences of over-policing extend beyond an individual’s experience of incarceration, as families are separated and community members taken out of their local economies, an advantageous method for determining where reinvestment should go is to identify neighborhoods with the highest concentration of marijuana-related law enforcement activity.

Arrests by Neighborhood

To identify the New York City communities in which revenue from a legal adult-use cannabis program should be targeted, the Comptroller’s Office sought first to rank neighborhoods by marijuana-related arrest rate. To do this, the Comptroller’s Office linked precinct-level New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services data from the eight full calendar years between 2010 and 2017 to their corresponding neighborhoods and then used data on population size from the U.S. Census Bureau to produce arrest rates by year. The 55 neighborhoods, which generally align with New York City community districts, were then ranked by average arrest rate over the eight-year period. While the Comptroller’s Office did not at the time of writing have access to precinct-level data prior to 2010, it is important to note that earlier data could be included to show the full scope and impact of enforcement activity over time.

Producing this ranking reveals that the Brooklyn neighborhood of Brownsville and Ocean Hill had the highest average marijuana-related arrest rate by far, followed by East New York and Starrett City, also in Brooklyn; Concourse, Highbridge, and Mount Eden in the Bronx; and Washington Heights, Inwood, and Marble Hill and East Harlem in Manhattan (Table 1). Forest Hills and Rego Park in Queens had the lowest arrest rate, followed by Borough Park, Kensington and Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn and the Upper East Side in Manhattan (Table 2). Notably, the arrest rate in Brownsville, the highest-ranking neighborhood, is roughly 30 times higher than the lowest-ranking neighborhood, Forest Hills and Rego Park. While Forest Hills averaged four arrests per month during the period, Brownsville averaged four per day.

Table 1: Highest Average Marijuana-Related Arrest Rates

| Community District(s) | Neighborhood | Total Arrests (2010-2017) | Average Arrest Rate (per 100,000 people) |

| BK16 | Brownsville & Ocean Hill | 10,395 | 1062 |

| BK5 | East New York & Starrett City | 9,453 | 776 |

| BX4 | Concourse, Highbridge & Mount Eden | 8,143 | 710 |

| MN12 | Washington Heights, Inwood & Marble Hill | 11,849 | 687 |

| MN11 | East Harlem | 6,540 | 670 |

| BX3 & BX6 | Belmont, Crotona Park East & East Tremont | 8,892 | 655 |

| BX7 | Bedford Park, Fordham North & Norwood | 6,526 | 642 |

| BX5 | Morris Heights, Fordham South & Mount Hope | 6,805 | 630 |

| MN9 | Hamilton Heights, Manhattanville & West Harlem | 6,576 | 622 |

| BK9 | Crown Heights South, Prospect Lefferts & Wingate | 5,206 | 587 |

Table 2: Lowest Average Marijuana-Related Arrest Rates

| Community District(s) | Neighborhood | Total Arrests (2010-2017) | Average Arrest Rate (per 100,000 people) |

| QN6 | Forest Hills & Rego Park | 332 | 36 |

| BK12 | Borough Park, Kensington & Ocean Parkway | 645 | 50 |

| MN8 | Upper East Side | 892 | 51 |

| SI3 | Tottenville, Great Kills & Annadale | 834 | 63 |

| BK11 | Bensonhurst & Bath Beach | 1022 | 69 |

| QN11 | Bayside, Douglaston & Little Neck | 726 | 76 |

| SI2 | New Springville & South Beach | 1035 | 98 |

| QN7 | Flushing, Murray Hill & Whitestone | 2046 | 102 |

| BK15 | Sheepshead Bay, Gerritsen Beach & Homecrest | 1241 | 106 |

| QN9 | Richmond Hill & Woodhaven | 1,468 | 122 |

Between 2010 and 2017, Brooklyn accounted for slightly fewer than one-third of arrests, the most of any borough, followed by Bronx, Manhattan, Queens, and Staten Island. Nearly half of all neighborhoods in the Bronx, however, are among the top ten by arrest rate. Clearly, there are stark disparities in arrest rate depending on geography. And these disparities sometimes exist among adjoining communities. Indeed, the marijuana-related arrest rate in East Harlem is 13 times higher than the arrest rate on the Upper East Side.

Race and Ethnicity

Demographic data on arrests further reveals which New Yorkers have been disproportionately impacted. As cited earlier and recently evidenced in a widely-reported study by the Misdemeanor Justice Project at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Black and Latinx New Yorkers have historically been arrested at far higher rates than their white counterparts, despite the fact that rates of cannabis use are similar across race and ethnicity.[vii]

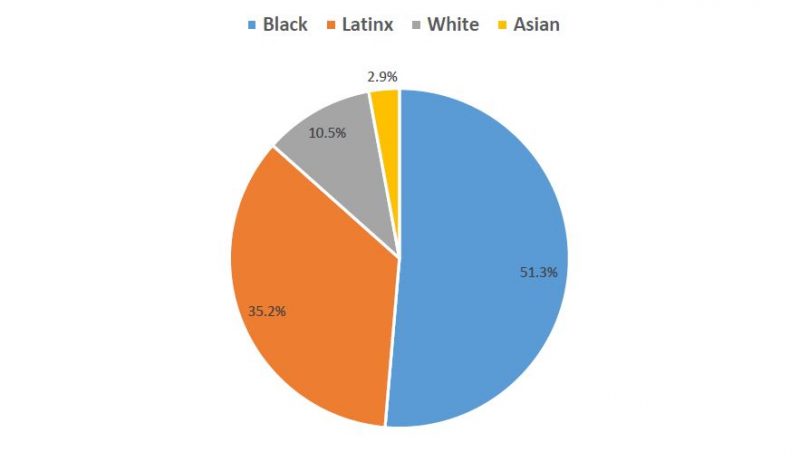

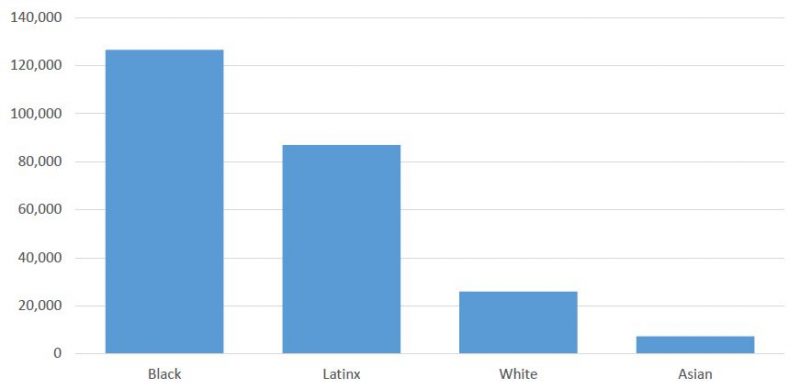

Considering the data on arrests between 2010 and 2017, more than half (51.3 percent) of all arrests were of Black people and more than one-third (35.2 percent) were of Latinx people (Charts 1 and 2). In total, there were eight times as many arrests of Black and Latinx people as there were of white people, 86.5 percent compared to 10.5 percent. Correspondingly, based on the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis, the ten New York City neighborhoods with the largest combined Black and Latinx population accounted for more than one-third (35.1 percent) of all arrests between 2010 and 2017. The ten neighborhoods with the smallest combined Black and Latinx population accounted for just 6.9 percent of arrests.

Chart 1: Marijuana Arrests by Race and Ethnicity as Proportion of Total Marijuana Arrests (2010-2017)

Chart 2: Total Marijuana Arrests by Race and Ethnicity (2010-2017)

Age

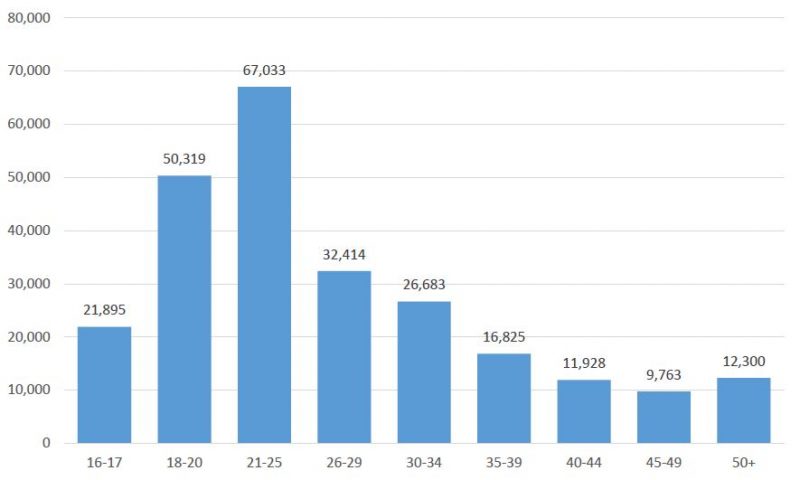

In general, those arrested for marijuana possession since 2010 have tended to be younger. More than half (55.9 percent) of all arrests were of people under the age of 25. As Chart 3 shows, the age group accounting for the single highest number of arrests are 21- to 25-year-olds. The neighborhoods with the highest arrest rates also skew younger, with median age in the low 30s, than those neighborhoods with lower arrest rates, where the median age in most is over 40. For young people, the consequences of arrests and of incarceration can be especially devastating, leading to temporary, if not permanent, disruptions in education, as well as long-term employment instability and economic insecurity. Notably, the New York State legalization bill, the MRTA, would legalize cannabis use for adults 21 and older and entirely remove criminal penalties for young people under 21.[viii]

Chart 3: Marijuana Arrests by Age (2010-2017)

Income, Poverty, and Unemployment

The neighborhoods with the highest rates of arrest due to a marijuana-related offense have lower household income, on average, as well as far higher rates of unemployment and poverty than areas of the city with relatively low arrest rates. The five neighborhoods in the city with median household income below $30,000 accounted for more than 40,000 or 18.9 percent of all arrests, more than twice as many arrests as the six neighborhoods with median household income over $100,000. The average poverty rate among the ten highest-ranking neighborhoods is 32.5 percent, which far exceeds the citywide poverty rate of 18.9 percent and is more than double the rate among the bottom ten (14.3 percent). Additionally, in four of the five highest-ranking neighborhoods by arrest rate—Brownsville and Ocean Hill; Concourse, Highbridge, and Mount Eden; Washington Heights, Inwood, and Marble Hill; and East Harlem—unemployment exceeds 10 percent (Table 3). Citywide, the unemployment rate is half that (5.2 percent).[ix]

Table 3: NYC Neighborhoods by Marijuana-Related Arrest Rate

and Unemployment Rate

| Community District(s) | Neighborhood | Average Arrest Rate (per 100,000 people) | Unemploy-ment Rate |

| BK16 | Brownsville & Ocean Hill | 1062 | 13.9% |

| BK5 | East New York & Starrett City | 776 | 8.7% |

| BX4 | Concourse, Highbridge & Mount Eden | 710 | 12.3% |

| MN12 | Washington Heights, Inwood & Marble Hill | 687 | 12.2% |

| MN11 | East Harlem | 670 | 10.4% |

| BX3 & BX6 | Belmont, Crotona Park East & East Tremont | 655 | 15.6% |

| BX7 | Bedford Park, Fordham North & Norwood | 642 | 12.8% |

| BX5 | Morris Heights, Fordham South & Mount Hope | 630 | 11.7% |

| MN9 | Hamilton Heights, Manhattanville & West Harlem | 622 | 7.5% |

| BK9 | Crown Heights South, Prospect Lefferts & Wingate | 587 | 10.5% |

Because New Yorkers generally cannot have more than $3,000 in assets to be eligible for cash assistance, utilization of the benefit offers an additional indication of a household’s financial resources.[x] Six of the highest-ranking neighborhoods by arrest rate fall among the top ten for proportion of households with cash assistance income: Brownsville and Ocean Hill; Belmont, Crotona Park East and East Tremont; Morris Heights, Fordham South and Mount Hope; Concourse, Highbridge and Mount Eden; East New York and Starrett City; and Bedford Park, Fordham North and Norwood. The Brownsville and Ocean Hill neighborhood has both the highest arrest rate and, at 11.0 percent, the highest proportion of households utilizing cash assistance. While households may have very few assets and not receive cash assistance, the totality of the economic data explored here underscore that the communities most impacted by prohibition are among the more economically insecure in the city.

Home Ownership and Value

Owning a home, one of the most commonly owned assets, is often one of the largest contributors to household wealth. The Comptroller’s analysis additionally finds that neighborhoods with higher rates of arrest tend to have lower rates of home ownership. Among the 10 highest-ranking neighborhoods by arrest rate, roughly one in 10 homes are owner-occupied (homeownership rate of 11.4 percent), compared to one in two homes among the 10 lowest-ranking neighborhoods (51.5 percent). Among the 10 highest-ranking neighborhoods, median home value is roughly $418,000 on average, compared to about $591,000 among the 10 lowest-ranking neighborhoods.

Credit Scores

Based on a 2017 analysis by the Comptroller’s Office, roughly one in four credit scores in New York City are considered subprime (between 300 and 600), a rating that can significantly inhibit access to credit and drive up interest rates offered on loans.[xi] In general, marijuana-related arrest rate tracks closely with credit score, with the neighborhood of Brownsville and Ocean Hill having both the highest arrest rate and lowest median credit score (598) in the city; Forest Hills and Rego Park, on the other end of the ranking by arrest rate, has a median credit score of 738. At roughly 46.7 percent, Brownsville and Ocean Hill also has the highest proportion of consumers with a subprime credit score. Among the ten highest-ranking neighborhoods by arrest rate, only one (Crown Heights South, Prospect Lefferts, and Wingate) has a median credit score that is considered prime, between 661 and 850. The remaining neighborhoods average credit scores that are either subprime or nonprime, between 601 and 660 (Table 4).

Table 4: NYC Neighborhoods by Marijuana-Related Arrest Rate and

Median Credit Score

| Community District(s) | Neighborhood | Average Arrest Rate (per 100,000 people) | Median Credit Score |

| BK16 | Brownsville & Ocean Hill | 1062 | 598 |

| BK5 | East New York & Starrett City | 776 | 613 |

| BX4 | Concourse, Highbridge & Mount Eden | 710 | 603 |

| MN12 | Washington Heights, Inwood & Marble Hill | 687 | 660 |

| MN11 | East Harlem | 670 | 633 |

| BX3 & BX6 | Belmont, Crotona Park East & East Tremont | 655 | 600 |

| BX7 | Bedford Park, Fordham North & Norwood | 642 | 623 |

| BX5 | Morris Heights, Fordham South & Mount Hope | 630 | 599 |

| MN9 | Hamilton Heights, Manhattanville & West Harlem | 622 | 655 |

| BK9 | Crown Heights South, Prospect Lefferts & Wingate | 587 | 664 |

Creating Equity in the Cannabis Industry

The neighborhoods that should receive reinvestment following the development of an adult-use marijuana program are those that likely stand to gain the most from that funding and support. However, the economic conditions in the neighborhoods with the highest rates of marijuana-related arrests additionally suggest that it is precisely these New Yorkers, those who have been most impacted by marijuana-related law enforcement, who will face the most barriers to participating in a legal cannabis industry. Their relatively young age combined with inconsistent work experience, limited assets, and poor credit automatically put them at a disadvantage in accessing potential opportunities in the market, in particular raising funds or securing loans that might be needed to get a new business off the ground.

As the experiences of other states and New York’s own medical marijuana program show, there are a number of structural barriers to participating in the legal industry. People with prior drug-related convictions may be barred from applying for business licenses, and capital requirements and license fees are often prohibitive. In implementing New York’s medical marijuana program, for example, the New York State Department of Health was initially able to issue only five licenses to manufacture and dispense medical marijuana, and applicants for these licenses had to submit a non-refundable application fee of $10,000, plus a refundable registration fee of $200,000.[xii] The latter amount is seven times the median household income in Brownsville. In neighboring Massachusetts, where retail sales of cannabis for adult use began in November, application fees for establishing a marijuana business, such as a cultivator, microbusiness, manufacturer, retailer, or testing laboratory, are minimal by comparison, ranging from $100 to $600. However, annual license fees will cost up to $25,000.[xiii]

The high cost of entry and demand—there were 43 applicants for New York’s five medical licenses, for instance—favors entrepreneurs and enterprises that are already well-resourced.[xiv] But as the Comptroller’s analysis shows, the communities most impacted by cannabis enforcement are likely to have limited access to a range of, if any, financing options. This has been the case in other states that have developed an adult-use program as well, and the results have been unsurprising. The City of Oakland, California received hundreds of cannabis business applications but had only one Black dispensary owner until this year.[xv]

In laying the groundwork for an adult-use marijuana program, New York State and New York City should closely consider other states’ and localities’ approaches. Indeed, some jurisdictions have already heeded the lessons from states that did not incorporate equity provisions in the early stages of legalization. In Massachusetts, the state statute to legalize explicitly required the new Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission to ensure people from communities disproportionately harmed by prohibition are able to participate in the legal industry. As a result, in addition to giving priority to applicants who have lived in “areas of disproportionate impact,” the Commission created a Social Equity Program to further reduce barriers to entry. Applicants who have lived in an area of disproportionate impact for at least five of the past ten years, have a previous drug conviction, or have been married to or are the child of someone with a drug conviction will be considered and, if accepted, offered business development support including with financing and mentorship.[xvi] While it is too early to know if Massachusetts’ cannabis industry will end up being more inclusive of impacted communities than elsewhere, the measures the state has taken are promising steps forward.

Recommendations

According to a recent Marijuana Business Daily survey, only 10 percent of cannabis business owners identify as Black or Latinx.[xvii] The lack of racial and ethnic diversity among CEOs is not unique, of course, to the cannabis industry, but the fact that Black and Latinx people have disproportionally been the subjects of cannabis enforcement makes it uniquely insidious. This report’s findings suggest that the adult-use cannabis industry in New York will be similarly exclusionary, unless action is taken to ensure equity from the start. To that end, the Comptroller’s Office makes the following recommendations:

Invest tax revenue in impacted communities:

A significant portion of the tax revenue generated by legalization should be awarded on a competitive basis to localities and community-based organizations working in neighborhoods with the highest proportion of marijuana-related arrests and that meet other criteria, such as having high rates of unemployment and a demonstrated need for mental health or substance use treatment. The New York State Community Grants Reinvestment Fund, as envisioned in the MRTA, offers a model for the types of services this funding should support, which include job placement, adult education, mental health treatment, substance abuse treatment, and legal assistance related to reentry.[xviii] In identifying these priority neighborhoods, the state entity charged with implementing the adult-use marijuana program could follow a method similar to the one outlined in this report to track all marijuana-related arrests. While this report covers eight years in the life of prohibition, earlier data should be included to identify the communities most harmed by decades of punitive drug laws.

Adopt inclusive licensee eligibility requirements:

Any State legislation that seeks to create an adult-use marijuana program should include explicit equity provisions so that the adult-use market reflects the communities most impacted by prohibition. Specifically, people with prior marijuana-related convictions should be made eligible for cannabis licenses, as issued by the relevant State agencies. Applicants for licenses and permits should in turn be required to demonstrate how they will support hiring of people with prior convictions. In addition, New York State should consider waiving initial application and licensing fees for applicants from priority neighborhoods and regularly solicit feedback to ensure that fees associated with establishing an adult-use cannabis business are not prohibitive.

Establish a NYC cannabis equity program:

Given the barriers to breaking in to the market and the economic conditions in neighborhoods most impacted by prohibition, New York City should create a citywide equity program that would function as an incubator hub for local entrepreneurs interested in participating in the new adult-use marijuana industry. In addition to providing general technical assistance, this new City office, housed in the NYC Department of Small Business Services, would help interested parties navigate regulations and licensing procedures, as well as secure financing. Priority would be given to New Yorkers with prior marijuana-related convictions and those closely related to someone with a marijuana-related conviction. To facilitate the implementation of the program, state legislation establishing an adult-use marijuana program should allow for a statewide equity program and not preclude local jurisdictions from developing municipal-level equity initiatives.

Data and Methods

To produce the ranking of New York City neighborhoods by arrest rate, the Comptroller’s Office relied on New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services data on PL 221.10 arrests, criminal possession of marijuana in the fifth degree, a class B misdemeanor. As arrests are reported by police precinct, in order to determine arrest rate by neighborhood, precinct-level data were approximated to neighborhood level using a universal crosswalk on file with the Comptroller’s Office. Precinct-level data from the eight full calendar years between 2010 and 2017 were linked to their corresponding neighborhoods, and U.S. Census Bureau data on neighborhood population size were used to produce arrest rates by year.

The table below shows the complete list of neighborhoods ranked by average marijuana-related arrest rate over the eight-year period. Although the Comptroller’s Office did not have precinct-level data prior to 2010 or use data on arrests or summons for other marijuana-related offenses, these should be included to show the full scope of arrests over time.

Complete List of NYC Neighborhoods by Marijuana-related Arrest Rate:

| Community District(s) | Neighborhood | Total Arrests (2010-2017) | Average Arrest Rate (per 100,000 people) | |

| 1 | BK16 | Brownsville & Ocean Hill | 10,395 | 1062 |

| 2 | BK5 | East New York & Starrett City | 9,453 | 776 |

| 3 | BX4 | Concourse, Highbridge & Mount Eden | 8,143 | 710 |

| 4 | MN12 | Washington Heights, Inwood & Marble Hill | 11,849 | 687 |

| 5 | MN11 | East Harlem | 6,540 | 670 |

| 6 | BX3 & BX6 | Belmont, Crotona Park East & East Tremont | 8,892 | 655 |

| 7 | BX7 | Bedford Park, Fordham North & Norwood | 6,526 | 642 |

| 8 | BX5 | Morris Heights, Fordham South & Mount Hope | 6,805 | 630 |

| 9 | MN9 | Hamilton Heights, Manhattanville & West Harlem | 6,576 | 622 |

| 10 | BK9 | Crown Heights South, Prospect Lefferts & Wingate | 5,206 | 587 |

| 11 | MN10 | Central Harlem | 6,159 | 573 |

| 12 | BK8 | Crown Heights North & Prospect Heights | 5,558 | 558 |

| 13 | BX9 | Castle Hill, Clason Point & Parkchester | 8,048 | 548 |

| 14 | BX1 & BX2 | Hunts Point, Longwood & Melrose | 6,739 | 528 |

| 15 | BK17 | East Flatbush, Farragut & Rugby | 5,536 | 504 |

| 16 | BX12 | Wakefield, Williamsbridge & Woodlawn | 5,555 | 491 |

| 17 | BK3 | Bedford-Stuyvesant | 4,945 | 453 |

| 18 | QN14 | Far Rockaway, Breezy Point & Broad Channel | 3,628 | 389 |

| 19 | SI1 | Port Richmond, Stapleton & Mariner’s Harbor | 5,317 | 381 |

| 20 | BK4 | Bushwick | 4,134 | 368 |

| 21 | QN12 | Jamaica, Hollis & St. Albans | 6,891 | 366 |

| 22 | MN4 & MN5 | Chelsea, Clinton & Midtown Business District | 4,040 | 353 |

| 23 | BK13 | Brighton Beach & Coney Island | 2,868 | 331 |

| 24 | MN3 | Chinatown & Lower East Side | 4,271 | 330 |

| 25 | MN6 | Murray Hill, Gramercy & Stuyvesant Town | 3,387 | 293 |

| 26 | MN1 & MN2 | Battery Park City, Greenwich Village & Soho | 3,475 | 290 |

| 27 | BX8 | Riverdale, Fieldston & Kingsbridge | 2,382 | 274 |

| 28 | BX11 | Pelham Parkway, Morris Park & Laconia | 2,655 | 264 |

| 29 | QN3 | Jackson Heights & North Corona | 3,677 | 254 |

| 30 | BK2 | Brooklyn Heights & Fort Greene | 2,561 | 250 |

| 31 | QN13 | Queens Village, Cambria Heights & Rosedale | 4,013 | 249 |

| 32 | BK18 | Canarsie & Flatlands | 4,080 | 247 |

| 33 | BK14 | Flatbush & Midwood | 2,980 | 234 |

| 34 | BK7 | Sunset Park & Windsor Terrace | 2,327 | 196 |

| 35 | BK6 | Park Slope, Carroll Gardens & Red Hook | 1,786 | 195 |

| 36 | BK1 | Greenpoint & Williamsburg | 2,335 | 193 |

| 37 | QN8 | Briarwood, Fresh Meadows & Hillcrest | 2,265 | 185 |

| 38 | QN10 | Howard Beach & Ozone Park | 1,954 | 183 |

| 39 | QN5 | Ridgewood, Glendale & Middle Village | 2,356 | 169 |

| 40 | BK10 | Bay Ridge & Dyker Heights | 1,683 | 166 |

| 41 | QN1 | Astoria & Long Island City | 2,261 | 165 |

| 42 | QN4 | Elmhurst & South Corona | 1,852 | 163 |

| 43 | MN7 | Upper West Side & West Side | 2,061 | 132 |

| 44 | QN2 | Sunnyside & Woodside | 1,389 | 130 |

| 45 | BX10 | Co-op City, Pelham Bay & Schuylerville | 1,207 | 129 |

| 46 | QN9 | Richmond Hill & Woodhaven | 1,468 | 122 |

| 47 | BK15 | Sheepshead Bay, Gerritsen Beach & Homecrest | 1241 | 106 |

| 48 | QN7 | Flushing, Murray Hill & Whitestone | 2046 | 102 |

| 49 | SI2 | New Springville & South Beach | 1035 | 98 |

| 50 | QN11 | Bayside, Douglaston & Little Neck | 726 | 76 |

| 51 | BK11 | Bensonhurst & Bath Beach | 1022 | 69 |

| 52 | SI3 | Tottenville, Great Kills & Annadale | 834 | 63 |

| 53 | MN8 | Upper East Side | 892 | 51 |

| 54 | BK12 | Borough Park, Kensington & Ocean Parkway | 645 | 50 |

| 55 | QN6 | Forest Hills & Rego Park | 332 | 36 |

Credit score data were previously provided to the Comptroller’s Office by Experian and informed the analysis presented in the Comptroller’s 2017 report, Making Rent Count: How NYC Tenants Can Lift Credit Scores and Save Money, accessible at https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/Rent-and-Credit-Report.pdf. For the purpose of this report, the Comptroller’s Office estimated credit scores at the neighborhood level using a zip code to PUMA crosswalk developed by Frank Donnelly, Geospatial Data Librarian at Baruch College. Estimates of median credit score were calculated by averaging median credit scores by zip code, weighted for population size.

All other data used in the report are derived from the U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2012-2016 5-Year Estimates. Data on home ownership and home value come directly from the NYU Furman Center’s CoreData.nyc tool.

Endnotes

[i] Latinx, used throughout this report, is a gender-neutral term for people of Latin American descent.

[ii] New York State Department of Health, Assessment of the Potential Impact of Regulated Marijuana in New York State (July 2018), https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/regulated_marijuana/docs/marijuana_legalization_impact_assessment.pdf.

[iii] New York State Governor Andrew M. Cuomo, “Governor Cuomo Announces Workgroup to Draft Legislation for Regulated Adult-Use Marijuana Program” (August 2, 2018), https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-announces-workgroup-draft-legislation-regulated-adult-use-marijuana-program.

[iv] Vermont is allowing adult use: https://legislature.vermont.gov/assets/Documents/2018/Docs/ACTS/ACT086/ACT086%20Act%20Summary.pdf; Licenses for the first retail shops in Massachusetts were recently approved by the State Cannabis Control Commission: https://www.bostonglobe.com/news/marijuana/2018/10/04/first-retail-pot-shops-massachusetts-approved-commission/nWh7YCPplLYsSsGXYCQbKO/story.html; Sales have started in Quebec and Ontario: https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/faq-how-legalized-pot-will-work-in-quebec and https://www.ontario.ca/page/cannabis-legalization#section-4; New Jersey’s governor supports legalization, and legislation is pending: https://www.nj.com/marijuana/2018/11/read_the_details_of_the_how_nj_is_likely_to_legali.html.

[v] The tax revenue that legalization would generate would ultimately depend on the combined State and City taxes imposed on marijuana sales. See New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, Estimated Tax Revenues from Marijuana Legalization in New York (May 2018), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/Legal_Marijuana_051418.pdf.

[vi] See Section 99-DD of S3040b, the Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act, https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2017/s3040b (accessed November 20, 2018).

[vii] The Misdemeanor Justice Project, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Trends in Arrests for Misdemeanor Charges, New York City 1993-2016 (February 1, 2018).

[viii] Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act, https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2017/s3040b (accessed November 20, 2018).

[ix] New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, New York City Neighborhood Economic Profiles 2018 Edition (August 2018), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/Neighborhood_Economic_Profiles_2018.pdf.

[x] In 2016, assets for receipt of TANF were limited to $2,000 or $3,000 for those over the age of 60. Linda Giannarelli, Christine Heffernan, Sarah Minton, Megan Thompson, and Kathryn Stevens, Welfare Rules Databook: State TANF Policies as of July 2016, OPRE Report 2017-82 (October 2017), https://wrd.urban.org/wrd/data/databooks/2016%20Welfare%20Rules%20Databook%20(Final%20Revised%2001%2016%2018).pdf.

[xi] New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, Making Rent Count: How NYC Tenants Can Lift Credit Scores and Save Money (October 2017), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/Rent-and-Credit-Report.pdf.

[xii] New York State Department of Health, “Medical Marijuana Program Applications,” https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/medical_marijuana/application/applications.htm (accessed November 26, 2018).

[xiii] Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission, “Guidance on Marijuana Establishment Application & Annual License Fees,” http://mass-cannabis-control.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Guidance-Application-and-License-Fees.pdf (accessed November 26, 2018).

[xiv] New York State Department of Health, “Medical Marijuana Program Applications,” https://www.health.ny.gov/regulations/medical_marijuana/application/applications.htm (accessed November 26, 2018).

[xv] Oakland City Council, “Ordinance No. 13478,” http://www2.oaklandnet.com/oakca1/groups/cityadministrator/documents/agenda/oak070202.pdf (accessed December 3, 2018); Max Blau, “Legal Pot is Notoriously White. Oakland is Changing That” (March 27, 2018), Politico, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/03/27/oakland-legal-cannabis-hood-incubator-217657.

[xvi] Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission, “Guidance for Equity Provisions,” https://mass-cannabis-control.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/FINAL-Social-Provisions-Guidance-1PGR-1.pdf (accessed November 26, 2018).

[xvii] Eli McVey, “Percentage of cannabis business owners and founders by race” (September 11, 2017), Marijuana Business Daily, https://mjbizdaily.com/chart-19-cannabis-businesses-owned-founded-racial-minorities/.

[xviii] See Section 99-DD of S3040b, the Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act, https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2017/s3040b (accessed November 20, 2018).