A Message from the Comptroller

Dear New Yorkers,

I am pleased to release my office’s Annual Report on Capital Debt and Obligations for Fiscal Year 2025, part of our commitment to help ensure New York City’s long-term thriving is focusing on the soundness of our infrastructure and our finances.

City capital dollars build the school buildings where our kids are educated, the tunnels that bring us clean water, our public parks, libraries and hospitals, affordable housing for families, the space and technology needed for our municipal government and courts, and the roads and bridges that New Yorkers rely on every day.

The vast majority of the funding of capital assets comes through the City of New York’s municipal bond program administered by the Comptroller’s Office and the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget, but a share of our capital funding also comes from the State and Federal governments.

Earlier this month, my office published a first assessment of the risks posed to New York City by the Trump Administration. These include potential cuts to federal funding for housing, transportation, infrastructure, and climate protection. While the City may not be able to fill all the funding gaps with its own debt, it is now more crucial than ever that the capital program is managed to provide the capacity and the flexibility to address the most pressing priorities.

Since the release of last year’s report the New York State budget for Fiscal Year 2025, which was enacted in April 2024, amended the Transitional Finance Authority (TFA) Act to increase the amount of Future Tax Secured (FTS) bonds not subject to the City’s constitutional debt limit by $8.0 billion beginning on July 1, 2024, and by an additional $6.0 billion beginning on July 1, 2025, for a total of $14.0 billion of additional debt-incurring capacity. In the lead up to the passage of the amendment, my office published a Debt Affordability Study and evaluated the increase in debt-incurring capacity against the City’s capital needs, and debt affordability. Our analysis found that the increase in the City’s constitutional debt limit was adequate to accommodate planned capital investments without breaching affordability thresholds.

This year’s report examines and evaluates how much debt is outstanding, how much borrowing capacity remains available, how the City compares to other U.S. cities, and the affordability of debt service. Some of its key findings are:

- The City had $41.0 billion of debt-incurring power as of July 1, 2024. Despite the $14.0 billion increase in borrowing capacity, debt-incurring power is projected to drop to $33.2 billion by July 1, 2027.

- Debt service as a percentage of City tax revenues was 10.6 percent in Fiscal year 2024, essentially unchanged from the previous year and well below the 15.0 percent ceiling that the City uses to evaluate debt affordability. Under conservative assumptions, future capital spending is expected to push debt service closer to the policy ceiling without exceeding it.

- The City’s credit rating remains strong. NYC’s debt burden is relatively high compared to U.S. peer cities, but not unreasonably so when viewed in context. Rating agencies have maintained NYC’s General Obligation bond rating at Aa2 (Moody’s), AA (S&P and Fitch), and AA+ (Kroll). The rating agencies continue to cite the City’s large and diverse economy, strong financial management, and liquidity among positive credit attributes that support GO ratings. Changes to rating criteria over the last year can be found in my office’s economic newsletters published in March, September, and October of this year.

Though the coming year is not free of risks, especially those stemming from policy changes enacted by the incoming Federal Administration, I am proud to report that our City capital budget and debt obligations are on sound fiscal footing and put us in a strong position to face the challenges ahead.

Brad Lander

New York City Comptroller

I. Executive Summary

The City of New York (the “City”) utilizes long-term debt to finance capital projects including its schools, water supply and sewers, affordable housing, transportation, public safety and justice facilities, parks, libraries, technology, and other infrastructure projects. The City can incur debt, subject to certain exclusions, only up to a limit that is set in the New York State Constitution. In accordance with Section 232 of the City Charter, the City Comptroller is required to report the amount of debt the City may incur within the limit during the current Fiscal Year and each of the three succeeding Fiscal Years.[1] As in previous years, this report provides a comprehensive overview of the City’s debt, of its debt- incurring capacity, and affordability indicators, both over time and compared with a group of other U.S. cities.

Key Findings

- As of the start of Fiscal Year 2025, the amount of outstanding City debt counted against the Constitutional limit[2] was $41.0 billion below the limit of $136.8 billion (i.e., debt-incurring capacity of approximately 29.9 percent of the limit). Even though the City’s indebtedness is projected to grow faster than the debt limit, a combination of the new Transitional Finance Authority (TFA) Act statutory exemption and growth in the General Debt Limit results in the City’s projected remaining debt-incurring power to be $33.2 billion as of July 1, 2027. Table 1 below, drafted in accordance with Section 232 of the City Charter, provides the full projection.

- The analysis of historical capital commitments included in this report suggests that the City could meet and exceed the targets set by the September Capital Commitment Plan, an improvement in the City’s efforts to accurately project and achieve Capital Commitment Plan targets.

- The share of tax revenues dedicated to debt service fell slightly from 10.7 percent in Fiscal Year 2023 to 10.6 percent in Fiscal Year 2024, well below the 15.0 percent ceiling used to evaluate affordability as articulated in the City’s Debt Management Policy. Based on budget assumptions from the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget released in June 2024, the Office of the Comptroller’s tax revenue projections published in August, and using conservative interest rate assumption for future debt issuance, the share is projected to reach approximately 13.9 percent by Fiscal Year 2034.

- New York City’s debt burden is relatively high compared to U.S. peer cities, but not unreasonably so when viewed in context. While debt per capita and relative to taxable value is well above those of the City’s peer group, debt outstanding as a percentage of personal income and debt burden as a percent of revenues is much closer to the average. The City should also be viewed as an essential leader of the global economy with economic strengths that flourish in a high-density environment, which drives the need for greater infrastructure and debt financing.

- The City’s credit ratings remain strong. In Fiscal Year 2024, Moody’s Investors Service maintained the City’s General Obligation (GO) bond rating at Aa2. Standard and Poor’s Global Ratings (S&P) maintained its rating of the City’s GO bonds at AA. Fitch Ratings (Fitch) maintained its rating of GO bonds to AA. Kroll Bond Rating Agency (Kroll) rated the City’s GO bonds AA+.

- The report analyzes the City’s remaining debt-incurring power and debt affordability metrics using the Office of the Comptroller’s debt limit (which is calculated via a formula based on the value of the city’s real property), revenue, and borrowing projections through Fiscal Year 2033. The “achievement scenarios” used in the analysis are based on additional commitments beyond those set forth in the Fiscal Year 2025 September Capital Commitment Plan (September Capital Commitment Plan). The analysis shows:

- The City’s remaining debt-incurring power is expected to reach a low point of $8.3 billion in Fiscal Year 2031 before increasing slightly in subsequent years to $11.1 billion at the end of Fiscal Year 2034. While there is some cushion to absorb additional commitments, if actual commitments outperform projections by 10 percent on average, the City could breach the debt limit in Fiscal Year 2031.

- Debt service as a share of tax revenues is projected to reach a maximum of 14.3 percent in Fiscal Year 2034. However, if actual commitments exceed planned targets by more than 10 percent, or if tax revenues beyond Fiscal Year 2028 grow at 2.75 percent versus the assumed 4.0 percent, debt service as a share of tax revenues could breach the City’s 15.0 percent policy threshold as early as Fiscal Year 2032.

Table 1. Projected NYC Debt-Incurring Power as of July 1st

| Date | July 1, 2024 | July 1, 2025 | July 1, 2026 | July 1, 2027 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal Year ($ in billions) | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 |

| Gross Statutory Debt-Incurring Powera | $136.8 | $140.0 | $148.0 | $153.2 |

| General Obligation (GO) Bonds Outstanding as of July 1, 2024 plus projected bond issuance (net)b | $41.6 | $45.7 | $49.0 | $52.9 |

| Less: Appropriations for GO Principal | ($2.4) | ($2.4) | ($2.4) | ($2.5) |

| Less: Excluded Debt | ($0.0) | ($0.0) | ($0.0) | ($0.0) |

| Plus: Incremental TFA Bonds Outstanding Above Statutory Exemptionc | $28.2 | $26.5 | $30.4 | $34.7 |

| Net Funded Debt Against the Limit | $67.3 | $69.7 | $76.9 | $85.1 |

| Plus: Contract and Other Liability | $28.5 | $29.7 | $33.1 | $34.9 |

| Total Projected Indebtedness Against the Limit | $95.8 | $99.4 | $110.1 | $120.0 |

| Remaining Debt-Incurring Power within General Limit | $41.0 | $40.5 | $38.0 | $33.2 |

| Remaining Debt-Incurring Power (%) | 29.9% | 29.0% | 25.7% | 21.7% |

Source: New York City Office of the Comptroller and select information from the Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Capital Commitment Plan and the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget.

Note: The Statement of Debt Affordability published by OMB in April 2024 presents data for the last day of each Fiscal Year which is June 30th instead. The City’s Statement of Debt Affordability Statement forecasts remaining debt-incurring power is projected to be $27.96 billion at the end of Fiscal Year 2025.

a New York City Office of the Comptroller’s projections as of the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget

b Net adjusted for Original Issue Discount, GO bonds issued for the water and sewer system and Business Improvement District debt.

c In April 2024 the TFA Act was amended to increase the total amount of TFA FTS bonds authorized to be outstanding above the City’s debt limit from $13.5 billion to $21.5 billion beginning on July 1, 2024, and $27.5 billion beginning on July 1, 2025.

This report is organized as follows:

Section II contains an overview of the debt issued directly by the City or on behalf of the City through public benefit corporations or authorities.

Section III provides a description of the City’s general debt limit and estimates of its remaining debt-incurring power. Particular attention is given to the projection of Special Equalization Ratios, which are crucial parameters calculated by the New York State Office of Property Tax Services (ORPTS) that the Office of the Comptroller has studied extensively. This section provides estimates of debt-incurring power at the beginning of the Fiscal Year through 2028 and at the end of the Fiscal Year through 2033.

Section IV presents a description of the City’s Fiscal Year 2025 September Capital Commitment Plan and provides a projection based on historical trends of the variance between target and actual commitments. The projected variance provides the basis for the achievement rate analysis that follows in Section V.

Section V presents measures and scenarios to assess the size of the City’s debt burden and its affordability. Several debt affordability measures are summarized and a comparison of New York City to other selected jurisdictions is provided.

II. Profile of New York City Debt

Debt to support New York City’s capital program is issued directly by the City, or on its behalf, through several different debt-issuing entities. This debt (Gross NYC debt) is used to finance the City’s capital projects and includes the City’s General Obligation (GO) bonds, NYC Transitional Finance Authority (TFA) Future Tax Secured bonds (TFA FTS) and TFA Building Aid Revenue Bonds (TFA BARBs), TSASC Inc. bonds, and other conduit issuers included in the Capital Lease Obligations and Other category (see Table 2). While New York City Municipal Water Finance Authority (NYW) bonds also fund City capital projects, they are not included in Gross NYC debt as they are paid for through charges for water and sewer service set and billed by the NYC Water Board.

In the 1980s, Gross NYC debt grew at an average annual rate of 4.5 percent. During the 1990s, it increased by 6.4 percent annually. The substantial increase during the 1990s resulted mainly from the rehabilitation of facilities that were neglected during the 1970s fiscal crisis. Gross debt outstanding grew at a rate of 4.0 percent per year from Fiscal Year 2000 to Fiscal Year 2024. The Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget and Financial Plan show average annual growth of approximately 6.9 percent through Fiscal Year 2028. Growth rates are expected to change as more detailed information about funding needs becomes available and the Financial Plan gets updated throughout the Fiscal Year.

Composition of Debt

The City issues debt to finance or refinance its capital program primarily through GO and TFA FTS bonds which accounted for 40.1 percent and 48.0 percent of total debt outstanding, respectively at the end of Fiscal Year 2024 (Table 2). Although the City did not issue TFA BARBs for new capital projects in Fiscal Year 2024, TFA BARBs accounted for 7.4 percent of total debt outstanding at the end of Fiscal Year 2024.

Each of the City’s credits are secured by sources of revenue to pay debt service, with residual amounts being remitted to the City’s General fund. GO debt service is backed by the full faith and credit of the City and is paid with Property Tax revenues from the General Debt Service Fund before remittance of the residual to the General Fund. TFA FTS debt service is paid from Personal Income Tax and, if insufficient, Sales Tax before remittance of the residual to the General Fund. To date, Sales Tax transfers have never been required to pay debt service. TFA BARBs debt service is paid from State Building Aid which is appropriated annually and paid by New York State to the TFA before being available to be remitted to the General Fund.

Tax-exempt debt accounted for approximately 81.2 percent of the Gross NYC debt outstanding at the end of Fiscal Year 2024. Taxable debt is issued for projects that have a public purpose but are ineligible for Federal tax exemption, such as housing loan programs, and represents 18.8 percent of Gross NYC debt outstanding at the end of Fiscal Year 2024.

At the end of Fiscal Year 2024 fixed rate debt accounted for approximately $96.6 billion, which represents approximately 92.8 percent of Gross NYC debt outstanding. To diversify interest rate risk and to broaden the investor base, New York City periodically issues variable rate debt. At the end of Fiscal Year 2024, variable debt accounted for $7.5 billion, which represents approximately 7.2 percent of Gross NYC bonds outstanding. Most Gross NYC bonds outstanding are in the form of GO and TFA FTS bonds.

GO bonds and TFA FTS bonds outstanding above $13.5 billion (as of the end of Fiscal year 2024) are the largest components of indebtedness under the general debt limit. In April 2024, the TFA Act was amended to increase the total amount of TFA FTS bonds authorized to be outstanding above the City’s debt limit to $21.5 billion beginning on July 1, 2024, and to $27.5 billion beginning on July 1, 2025. TFA BARBs, TSASC Inc. debt, and GASB 87 capital lease obligations and lease-purchase/conduit debt are not subject to the general debt limit.

Table 2. Gross NYC Bonds Outstanding as of June 30, 2024

| ($ in millions) | GO Bonds | TFA FTS | TFA BARBs | TSASC Inc. | Conduit Debt Issuersa | Gross Debt Outstanding | GASB 87 Capital Lease Obligationsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tax-Exempt | |||||||

| Fixed Rate | $29,038 | $36,468 | $6,952 | $909 | $3,602 | $76,972 | $0 |

| Variable | 4,509 c | 2,762 c | 0 | 0 | 233 c | 7,504 | 0 |

| Subtotal | $33,548 | $39,230 | $6,952 | $909 | $3,834 | $84,476 | $0 |

| Taxable | |||||||

| Fixed Rate | $8,153 c | $10,716 c | $720 c | $0 | $0 | $19,589 | $12,734 |

| Variable Rate | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | $8,153 | $10,716 | $720 | $0 | $0 | $19,589 | $12,734 |

| Total | $41,701 | $49,946 | $7,672 | $909 | $3,834 | $104,063 | $12,734 |

| Percent of Total | 40.1% | 48.0% | 7.4% | 0.9% | 3.7% | 100.0% | N/A |

Source: Annual Comprehensive Financial Report of the Comptroller for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2024.

a Includes $2.552 billion of Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation (HYIC) bonds, $541 million of DASNY bonds related to court facilities, health facilities and community college facilities, $408 million Health and Hospital bonds, $282 million of ECF bonds, $47 million IDA bonds and $4 million of tax lien securities.

b Includes GASB 87 capital lease obligations of $12.7 billion that are reflected in the table to comply with accounting reporting requirements. There are no bonds associated with the figure shown above.

c Interest rates on variable rate debt are reset on a daily, weekly, or other periodic basis.

d NYC GO taxable bond debt includes Build America Bonds (BABs). The TFA FTS and TFA BARBs taxable fixed rate debt includes BABs and Qualified School Construction Bonds (QSCBs). BABs and QSCBs are taxable bonds that were created under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 where the City of TFA receive cash subsidy from the United States Treasury to pay bond interest. These subsidies fluctuate each year due to changes in the amount of bonds outstanding and changes to the discounted rate from federal budget sequestration.

General Obligation Debt

The use of General Obligation debt, which is backed by the faith and credit of the City of New York, increased slightly in Fiscal Year 2024 from Fiscal Year 2023. As of June 30, 2024, GO debt totaled $41.7 billion and accounted for 40.1 percent of Gross NYC debt outstanding, relatively unchanged from its share of total debt outstanding at the conclusion of Fiscal Year 2023.

Debt service for GO bonds is paid from real property taxes which are deposited with and retained by the State Comptroller into the General Debt Service Fund under a statutory formula for the payment of debt service. This “lock-box” mechanism assures that debt service obligations are satisfied before property tax revenues are released to the City’s General Fund.

During Fiscal Year 2024, the City issued $4.4 billion of GO bonds, of which $4.2 billion were issued to raise proceeds for the City’s capital needs and $180 million were refunding bonds that generated savings over the life of the bonds. In addition, $551 million of GO bonds were converted from variable-rate to the fixed-rate interest mode.

A total of $2.5 billion of GO bonds matured during Fiscal Year 2024. GO debt outstanding was approximately $1.6 billion higher at the end of Fiscal Year 2024 than at the end of Fiscal Year 2023.[3]

Transitional Finance Authority Debt

The Transitional Finance Authority (TFA) was created as a public benefit corporation in 1997 with the power and authorization to issue bonds up to an initial limit of $7.5 billion, but after several legislative changes the limit was increased to $13.5 billion. This borrowing does not count against the City’s general debt limit. The City exhausted the $13.5 billion limit in Fiscal Year 2007. In July 2009, the State Legislature authorized TFA to issue FTS bonds beyond the $13.5 billion limit, with the additional borrowing subject to the City’s general debt limit. Thus, the incremental TFA debt issued in Fiscal Year 2010 and beyond, to the extent the amount outstanding exceeds $13.5 billion, has been combined with City GO debt when calculating the City’s indebtedness within the debt limit.

In April 2024 the TFA Act was again amended to increase the total amount of TFA FTS bonds authorized to be outstanding above the City’s general debt limit to $21.5 billion beginning on July 1, 2024, and $27.5 billion on July 1, 2025. Starting July 1, 2024, these new thresholds are considered when calculating the City’s indebtedness within the debt limit.

The TFA issues two different types of debt — Future Tax Secured (FTS) bonds, which are payable from Tax Revenues, which consist of Personal Income Tax Revenues and Sales Tax Revenues (if necessary), and Building Aid Revenue Bonds (BARBs), which are paid by State Building Aid, which is appropriated annually and paid by New York State.

At the close of Fiscal Year 2024, TFA FTS and TFA BARBs debt totaled approximately $57.6 billion, comprised of approximately $49.9 billion of FTS debt and approximately $7.7 billion of BARBs debt, an increase of more than 7.5 percent from the close of the prior Fiscal Year. The total share of TFA debt as a percentage of Gross NYC debt outstanding increased from 54.6 percent at the end of Fiscal Year 2023 to 55.4 percent at the end of Fiscal Year 2024.

During Fiscal Year 2024, the TFA issued $7.6 billion of TFA FTS bonds, of which $6.1 billion were issued to raise proceeds for the City’s capital needs and $1.4 billion were refunding bonds that generated savings over the life of the bonds. In addition, $75 million of TFA FTS bonds were converted between modes. The TFA did not have any TFA BARBs financing activity during Fiscal Year 2024. During Fiscal Year 2024 a total of $1.9 billion TFA bonds matured consisting of $1.7 billion TFA FTS bonds and $207 million of TFA BARBs. Total TFA debt outstanding was approximately $4.1 billion higher at the end of Fiscal Year 2024 than at the end of Fiscal Year 2023.[4]

Debt Not Subject to the General Debt Limit

TFA BARBs

In April 2006, the State Legislature authorized the TFA to issue up to $9.4 billion of outstanding BARBs. This debt is used to finance a portion of the City’s five-year educational facilities capital plan and is excluded from the calculation of the City’s debt counted against the debt limit.

There was no TFA BARBs financing activity in Fiscal Year 2024 and as of June 30, 2024, TFA BARBs debt outstanding totaled $7.7 billion. There are currently no plans for future issuance of TFA BARBs to raise proceeds for new capital needs. The Mayor, in concert with the New York City Comptroller’s Office, retains discretion with regard to the specific amount of annual TFA BARBs borrowing subject to statutory and indenture limitations.

TSASC Inc.

TSASC Inc. is a local development corporation created under and subject to the provisions of the Not-for-Profit Corporation Law of the State of New York. TSASC Inc. bonds are secured by tobacco settlement revenues (TSR) as described in the Master Settlement Agreement among 46 states, six jurisdictions, and the major tobacco companies. In January 2017, TSASC Inc. refinanced all bonds issued under the Amended and Restated 2006 Indenture. The refunding bond structure continues to allow the TSRs to flow to both TSASC Inc. and the City, with 37.4 percent of the TSRs pledged (Pledged TSRs) to TSASC bondholders, and the remainder (Unpledged TSRs) going into the City’s General Fund. TSASC Inc. debt is excluded from the calculation of the City’s debt counted against the debt limit.

According to a voluntary Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA) filing dated April 30, 2024, TSASC Inc. stated that based on Pledged TSRs received TSASC Inc. projects it will be required to draw upon its Subordinate Liquidity Reserve Account to make debt service payments due on December 1, 2024. Based on projections in its adopted Fiscal Year 2025 Budget, TSASC Inc. projects it will be unable to support its subordinate debt service requirements starting June 1, 2025. On November 14, 2024, TSASC, Inc.’s Board of Directors authorized TSASC, Inc. to enter into a Security Agreement, which authorizes Unpledged TSRs to provide additional credit support for debt service payments.

There was no TSASC Inc. financing activity in Fiscal Year 2024 and as of June 30, 2024, TSASC Inc. debt outstanding totaled $909 million, which represent a $29 million decrease from the end of Fiscal Year 2023. There currently are no plans for future issuance of TSASC Inc. bonds to raise proceeds for new capital needs.

GASB 87 Capital Lease and Other Obligations

Capital Lease and Other Obligations totaled $16.6 billion as of June 30, 2024. The GASB 87 capital lease component of this total is $12.7 billion and other amounts included in the total are as follows: $541 million of DASNY bonds related to court facilities, health facilities and community college facilities, $408 million NYC Health and Hospital bonds, $282 million of ECF bonds, $47 million IDA bonds, $4 million of tax lien securities and $2.6 billion of Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation bonds.

Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation

The Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation (HYIC) is a not-for-profit local development corporation formed in July 2004 to finance development in the Hudson Yards district of Manhattan — primarily the extension of the Number 7 subway line westward to 11th Avenue and 34th Street, which began operations in September 2015. No Interest Support Payments were made by the City to HYIC in Fiscal Year 2024 nor are any planned for in the future. In August 2018, however, the City Council passed a resolution authorizing the issuance of up to $500 million in additional HYIC debt to fund Phase 2 of the Hudson Boulevard expansion and related park and infrastructure improvements from West 36th Street to West 39th Street in the Hudson Yards Financing district.

As of June 30, 2024, HYIC had $2.55 billion in debt outstanding which consists of $2.46 billion of fixed rate bonds and $90 million which has been drawn upon from a loan facility agreement, which provides $380 million of financing capacity.

Other Issuing Entities

In addition to the financing mechanisms cited above, several independent entities issue bonds to finance infrastructure projects in the City and throughout the metropolitan area. The two largest issuers are NYC Municipal Water Finance Authority (NYW) and the New York State Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Bond proceeds from these entities are used to support capital projects that serve NYC residents. The outstanding indebtedness of these two authorities is summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

New York City Municipal Water Finance Authority

Created by State law in 1984, NYW’s purpose is to finance the capital needs and provide funding for the City’s water and sewer system which is operated by the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Examples of such projects are the construction, maintenance and repair of sewers, water mains, and water pollution control plants. Avoiding the need to build water filtration plants for upstate watersheds continues to be a high priority for DEP. Land acquisition strategies along with conservation-focused local development help the goal of preserving water quality.

Capital commitments, and by extension, projected borrowing continues to be a driver of water and sewer rate increases over the Financial Plan period. Based on the Fiscal Year 2025 September Capital Commitment Plan, DEP’s Fiscal Year 2025 though fiscal 2028 Four-Year Capital Program assumes an average annual cash funding need of approximately $2.7 billion planned average annual authorized City-funds commitment level is approximately $3.0 billion over the same period.

Additionally, the recent re-introduction of the Base Rental Payment will impact water and sewer rates for the foreseeable future. In Fiscal Year 2024, the City requested a base rental payment of $145 million, which represents approximately one half of the maximum annual rental payment. The City’s Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget and June Financial Plan reflects the intent to request the annual base rental payment. Projected base rental payments in Fiscal Year 2025 through 2028 are $295 million, $313 million, $325 million and $369 million, respectively. Base rental payments are subordinate to required daily deposits for Authority expenses, NYW debt service payments, Water Board expenses, and the City’s water and sewer system’s operation and maintenance expenses.

As shown in Table 3, NYW had $32.6 billion in debt outstanding as of June 30, 2024, an increase of $322 million, or approximately 1.0 percent, from Fiscal Year 2023. Debt issued by NYW is supported by fees and charges for the use of services provided by the system.

Table 3. NYW Debt Outstanding as of June 30, 2024

| ($ in millions) | Tax Exempt and Taxable |

|---|---|

| Fixed Rate | $28,703 |

| Variable Rate | 3,861 |

| Bond Anticipation Notes | 11 |

| Total | $32,575 |

Source: NYW Fiscal Year 2024 Financial Statements

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority

The MTA, a State controlled authority, is composed of six major agencies providing transportation throughout the metropolitan area. The MTA is responsible for the maintenance and operation of the New York City Transit bus and subway system as well as the Long Island and Metro-North Railroads and various bridges and tunnels.

Debt issued to fund the MTA’s capital program is secured by several revenue sources: revenues from system operations, surplus MTA Bridges and Tunnels revenue, State and local government funding, and certain taxes imposed in the metropolitan commuter transportation mobility tax district, which includes the counties of New York, Bronx, Kings, Queens, Richmond, Rockland, Nassau, Suffolk, Orange, Putnam, Dutchess, and Westchester.

In September 2024 the MTA adopted its 2025-2029 Capital Plan which totals $68.4 billion over the next five years. In 2019, the State enacted the MTA Reform and Traffic Mobility Act, which states that the MTA’s Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority needs to design, develop, build, and run the Central Business District (CBD) Tolling Program (also known as Congestion Pricing). The CBD Tolling Program along with the 2019 Real Estate Transfer Tax and Internet Sales Taxes aim to provide a stable and recurring source of support to finance the MTA’s capital program needs. These initiatives were expected to fund approximately $25.0 billion of capital projects over the 2020-2024 Capital Plan period and subsequent capital programs, including the 2025-2029 Capital Plan.

The implementation of the CBD Tolling Program, which is projected to generate revenue to support $15.0 billion of funding for the MTA Capital Program, was paused in early June, just weeks before it was scheduled to go into effect on June 30, 2024. On November 14, the New York State Governor announced a plan to start the CBD Tolling Program on January 5, 2025. The plan was approved by the MTA board on November 18, 2024, and by the Federal Highway Administration on November 22, 2024.

As shown in Table 4, on September 13, 2024, just prior to the release of the 2025-2029 Capital Plan, the MTA had $47.8 billion of debt outstanding.

Table 4. MTA Debt Outstanding as of September 13, 2024

| ($ in millions) | Tax Exempt and Taxable |

|---|---|

| Fixed Rate | $45,099 |

| Variable Ratea | 2,726 |

| Total | $47,825 |

Source: Metropolitan Transportation Authority “Summary of Debt Outstanding” dated September 13, 2024

aVariable rate included $1.90 billion of synthetic fixed rate bonds

New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation

New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation (NYCHH) has issued its own debt to fund capital improvements. These include the construction, renovation, improvement, and reconfiguration of NYCHH facilities and the acquisition and installation of machinery and equipment at NYCHH facilities. NYCHH debt is generally secured by all revenues, income, and receipts received by NYCHH, its providers, or HHC Capital with respect to the operation of the health system. A substantial portion of such monies are derived from Medicaid payments due to its providers. Of particular note, NYCHH bonds are secured by a reserve fund which, if unable to be replenished subsequent to a draw on NYCHH revenues, is to be replenished by City monies as certified by NYCHH to the City, subject to City appropriation. To date, the City has not been called upon to make such a payment. As of June 30, 2024, NYCHH had $408 million of bonds outstanding.

Analysis of Principal and Interest among the Major NYC Issuers

The two major types of debt that finance City capital projects outside the water and sewer system are NYC GO and TFA FTS bonds. TSASC Inc. bonds and TFA BARBs are smaller components of debt outstanding and there are no plans for future issuance of either credit to raise proceeds for capital needs. As a result, any debt for new capital needs is expected to be a mix of GO and TFA FTS bonds. Combined debt outstanding for GO, TFA and TSASC Inc., by Fiscal Year, is shown in Table 5:

Table 5. Projected Combined NYC Debt Outstanding Fiscal Years 2024 through 2034

| Projected Combined NYC Debt Outstanding for GO, TFA, and TSASC Inc., Fiscal Year 2024 – Fiscal Year 2034 ($ in millions) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal Year End | GO | TFA-FTS | TFA-BARB | TSASC Inc. | Total | Percent Change |

| 2024 | $41,701 | $49,946 | $7,672 | $909 | $100,228 | 6.0% |

| 2025 | $45,750 | $54,293 | $7,456 | $879 | $108,377 | 8.1% |

| 2026 | $49,070 | $58,227 | $7,232 | $854 | $115,383 | 6.5% |

| 2027 | $53,002 | $62,351 | $6,821 | $827 | $123,001 | 6.6% |

| 2028 | $57,043 | $66,475 | $6,479 | $800 | $130,797 | 6.3% |

| 2029 | $61,351 | $70,974 | $6,134 | $773 | $139,232 | 6.5% |

| 2030 | $65,720 | $75,260 | $5,771 | $744 | $147,496 | 6.0% |

| 2031 | $69,548 | $78,944 | $5,290 | $716 | $154,499 | 4.8% |

| 2032 | $72,365 | $81,811 | $4,856 | $689 | $159,721 | 3.4% |

| 2033 | $74,511 | $83,671 | $4,403 | $662 | $163,246 | 2.2% |

| 2034 | $75,621 | $84,498 | $3,925 | $635 | $164,679 | 0.9% |

Source: New York City Office of the Comptroller based on future borrowing assumptions from Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget

Based on NYC Office of Management and Budget (OMB) forecasts, the debt outstanding is expected to grow at an annual average rate of 5.2 percent between Fiscal Year 2024 to Fiscal Year 2034, as shown in Table 5. Projected average annual growth rate in the first half of this Financial Plan period (Fiscal Year 2024 through Fiscal Year 2028) is approximately 6.7 percent and average annual growth beyond the Financial Plan period is approximately 3.9 percent. This bifurcation in growth is primarily due to relative uncertainty of capital project specifics in the later years. Projected rates of growth are likely to change as more detailed plans are formulated in the future.

Borrowing is projected to average $11.9 billion annually according to OMB’s Fiscal Year 2025 to Fiscal Year 2034 capital cash flow estimates. This represents an increase of approximately $400 million annually from the Fiscal Year 2024 to Fiscal Year 2033 capital cash flow estimates projected in the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget.

The combined principal and interest composition for GO, TFA FTS, TFA BARBs and TSASC debt service is shown in Table 6:

Table 6. Estimated Principal and Interest Payments for GO, TFA FTS, TFA BARBs and TSASC Inc. as of June 30, 2024

| ($ in millions) | Estimated Principal | Estimated Interest | Estimated Total Debt Service |

Principal as Percent of Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal Year | GO | TFA FTS | TFA BARBs | TSASC Inc. | Total Principal | GO | TFA FTS | TFA BARBs | TSASC Inc. | Total Interest | ||

| 2025 | $2,452 | $1,691 | $216 | $30 | $4,389 | $1,991 | $2,330 | $357 | $45 | $4,724 | $9,114 | 48.2% |

| 2026 | $2,440 | $1,864 | $231 | $25 | $4,569 | $2,245 | $2,561 | $349 | $44 | $5,198 | $9,747 | 46.7% |

| 2027 | $2,428 | $2,024 | $318 | $27 | $4,796 | $2,480 | $2,814 | $335 | $43 | $5,671 | $10,468 | 45.8% |

| 2028 | $2,539 | $2,329 | $357 | $27 | $5,252 | $2,741 | $3,067 | $317 | $41 | $6,167 | $11,419 | 46.0% |

Source: New York City Office of the Comptroller based on future borrowing assumptions from Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget

Based on existing debt outstanding and projected borrowing assumptions in the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget, estimated principal payments in Fiscal Years 2025, 2026, 2027 and 2028 are $4.4 billion, $4.6 billion, $4.8 billion and $5.3 billion, respectively. Principal is estimated to be a 48.2 percent, 46.7 percent, 45.8 percent, and 46.0 percent share of debt service in Fiscal Years 2025, 2026, 2027 and 2028, respectively.

Fiscal Year 2024 Issuance

In Fiscal Year 2024, the City issued a combined nine GO and TFA FTS new money transactions, totaling $10.3 billion, which raised more than $11.1 billion for new money purposes to finance capital projects. The City also issued two refunding transactions that generated $179 million of debt service savings over the life of the bonds.

Finally, the City converted $551 million of GO bonds between variable and fixed rate interest modes and the TFA converted $75 million of TFA-FTS bonds between modes. The conversion did not generate proceeds for new capital projects and did not produce any savings or dissavings over the life of the bonds.

There was no TFA BARBs or TSASC Inc. financing activity in Fiscal Year 2024.

Fiscal Year 2024 Principal Outstanding and Amortization

GO debt outstanding totaled $41.7 billion at the end of Fiscal Year 2024. Of the debt outstanding, $20.8 billion, or approximately 50.0 percent, will mature over the next ten years.

TFA FTS and TFA BARBs debt outstanding totaled $57.3 billion in at the end of Fiscal Year 2024. Of the TFA debt currently outstanding, $23.9 billion, or approximately 41.7 percent, will mature over the next ten years.

Overall, $44.7 billion, or approximately 45.2 percent, of GO and TFA debt outstanding at the end of Fiscal Year 2024 is scheduled to amortize between Fiscal Year 2025 through and including Fiscal Year 2034, as shown in Table 7:

Table 7. Amortization of Principal GO, TFA and TSASC Inc. as of June 30, 2024 ($ in millions)

| Fiscal Years | GO | TFA FTS | TFA BARBs | GO and TFA | Percent of Total | TSASC Inc. | Grand Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025-2034 | $20,836 | $20,205 | $3,661 | $44,701 | 45.2% | $274 | $44,975 |

| 2035-2044 | $14,232 | $22,084 | $3,474 | $39,790 | 40.2% | $185 | $39,975 |

| 2045 and after | $6,633 | $7,387 | $451 | $14,471 | 14.6% | $450 | $14,921 |

| Total | $41,701 | $49,675 | $7,586 | $98,962 | 100.0% | $909 | $99,871 |

Source: Annual Comprehensive Financial Report of the Comptroller for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2024, TFA Fiscal Year 2024 Financial Statements and TSASC Inc. Fiscal Year 2024 Financial Statements

III. Debt-Incurring Power

This section of the report provides a description of the City’s general debt limit and estimates of its remaining debt-incurring power after the subtractions of indebtedness through Fiscal Year 2028. Pursuant to Section 135 of the NYS Local Finance Law, in general terms, indebtedness is defined as the sum of GO bonds, TFA Future Tax Secured bonds outstanding in excess of $21.5 billion (as of July 1, 2024), set to increase to $27.5 billion on July 1, 2025, and capital commitments entered into but not financed with bond proceeds.[5]

In conformance with Section 232 of the NYC Charter, the Comptroller’s Office prepares a table (Table 1 in the Executive Summary and Table 9 below) detailing the City’s debt- incurring power using the prescribed beginning-of-fiscal-year method. Within a Fiscal Year, this method results in the highest amount of debt-incurring power because it coincides with the timing of the appropriation of GO principal. For this reason, this section also provides estimates of debt- incurring power at the end of the fiscal Year, which generally marks the annual low point of debt-incurring power. The section also includes a projection of the City’s remaining debt-incurring power margin through Fiscal Year 2033.

The General Debt Limit

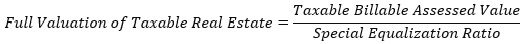

The New York State Constitution, Article VIII, sets limits to the amount of indebtedness of local governments (counties, cities, towns, villages, and school districts). Because, unlike New York City, local governments generally rely on the property tax as their main source of tax revenue, the value of the real estate within their jurisdictions represents a measure of the capacity to repay debt. Debt limits are set as a percentage of the five-year rolling average of the “full valuation of taxable real estate” (FV). In New York City, FV is derived from two sources: the City’s Department of Finance (DOF) Taxable Billable Assessed Value (TBAV) and the New York State Office of Real Property Tax Services (ORPTS) special equalization ratio. The formula is:

New York City’s general debt limit (also referred to here as debt-incurring power) equals 10 percent of the five-year rolling average of FV. Because FV is an underestimate of the value of New York City real estate and because it disregards the City’s diversified tax revenue structure, the Constitutional debt limit does not fully reflect the City’s ability to assume and service debt to finance capital assets.

The New York City Council determines (“fixes”) the annual property tax rates upon approval of the City’s budget, pursuant to section 1516 of the City Charter. The so-called “tax fixing” resolution contains the calculations for the debt limit effective in the upcoming Fiscal Year. Table 8 contains the data for Fiscal Year 2025.

Table 8. Calculation of the Fiscal Year 2025 General Debt Limit

| Fiscal Year | Assessed Valuation of Taxable Real Property | Special Equalization Ratio | Full Valuation of Taxable Real Estate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | $271,688,749,747 | 0.2308 | $1,177,160,960,776 |

| 2022 | $257,560,316,555 | 0.2026 | $1,271,275,007,675 |

| 2023 | $275,614,595,502 | 0.2044 | $1,348,408,001,478 |

| 2024 | $287,719,502,079 | 0.1979 | $1,453,863,072,658 |

| 2025 | $300,109,002,061 | 0.1891 | $1,587,038,614,812 |

| 5-Year Average Value | $1,367,549,131,480 | ||

| 10 Percent of the 5-Year Average | $136,754,913,148 | ||

Source: New York City Council Tax Fixing Resolution for FY 2025 p.5

Taxable Billable Assessed Value and Special Equalization Ratio

The Taxable Billable Assessed Value (TBAV) is determined by the City’s Department of Finance (DOF) through the annual assessment process, which follows several steps, as determined by statute and outlined below:[6]

- Classification of property into one of four classes.

- Estimation of DOF market value.

- Derivation of assessed values using assessment ratios.

- Derivation of TBAV by applying assessed value caps, phase-ins, and exemptions.

NYC’s DOF publishes a preliminary estimate of assessed values (“tentative assessment roll”) for the following Fiscal Year in January and a final estimate (“final assessment roll”) in May. In this report, the forecast of TBAV is based on the Fiscal Year 2025 final assessment roll and is consistent with the property tax revenue estimate published in Comments in NYC’s FY 2025 Adopted Budget. A description of the methodology is included in the Appendix.

Under NYS Real Property Tax Law Article 12-A (sections 1250 through 1254), a special equalization ratio is required for cities with a population of 125,000 or more. As shown in Table 8, each year ORPTS publishes five ratios for the calculation of the debt limit. The ratios are based on the last completed assessment roll (e.g., for the Fiscal Year 2025 limit, this is the Fiscal Year 2024 assessment roll which was finalized in May 2023). This office has published an in-depth analysis of special equalization ratios, detailing how they are constructed and the resulting undervaluation of New York City taxable real estate.

The forecast of the debt limit relies on a forecast of TBAV and special equalization ratios and is described in the Appendix.

Remaining Debt-Incurring Power as of July 1st

Table 9 summarizes the projected change in the City’s debt-incurring power, as of the beginning of Fiscal Years 2025 through 2028, as required by the City Charter. Based on the Office of the Comptroller’s projections as of the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget, the City’s Fiscal Year 2025 general debt-incurring power of $136.8 billion is projected to increase to $140.0 billion in Fiscal Year 2026, $148.0 billion in Fiscal Year 2027 and $153.2 billion in Fiscal Year 2028.

The City’s indebtedness counted against the statutory debt limit is projected to grow from $95.8 billion at the beginning of Fiscal Year 2025 to $120.0 billion by the beginning of Fiscal Year 2028. In April 2024 the TFA Act was amended to increase the total amount of TFA FTS bonds authorized to be outstanding above the City’s debt limit to $21.5 billion beginning on July 1, 2024, and $27.5 billion on July 1, 2025. Giving effect to the new TFA statutory exemptions the Office of the Comptroller projects remaining debt-incurring power of $33.2 billion on July 1, 2027.

Table 9. Projected NYC Debt-Incurring Power as of July 1st

| Date | July 1, 2024 | July 1, 2025 | July 1, 2026 | July 1, 2027 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal Year ($ in billions) | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 |

| Gross Statutory Debt-Incurring Powera | $136.8 | $140.0 | $148.0 | $153.2 |

| General Obligations (GO) Bonds Outstanding as of July 1, 2024 plus projected bond issuance (net)b | $41.6 | $45.7 | $49.0 | $52.9 |

| Less: Appropriations for GO Principal | ($2.4) | ($2.4) | ($2.4) | ($2.5) |

| Less: Excluded Debt | ($0.0) | ($0.0) | ($0.0) | ($0.0) |

| Plus: Incremental TFA Bonds Outstanding Above Statutory Exemptionc | $28.2 | $26.5 | $30.4 | $34.7 |

| Net Funded Debt Against the Limit | $67.3 | $69.7 | $76.9 | $85.1 |

| Plus: Contract and Other Liability | $28.5 | $29.7 | $33.1 | $34.9 |

| Total Projected Indebtedness Against the Limit | $95.8 | $99.4 | $110.1 | $120.0 |

| Remaining Debt-Incurring Power within General Limit | $41.0 | $40.5 | $38.0 | $33.2 |

| Remaining Debt-Incurring Power (%) | 29.9% | 29.0% | 25.7% | 21.7% |

Source: New York City Office of the Comptroller and select information from the Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Capital Commitment Plan and the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget

aNew York City Office of the Comptroller’s projections as of the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget

bNet adjusted for Original Issue Discount, GO bonds issued for the water and sewer system and Business Improvement District debt.

cIn April 2024 the TFA Act was amended to increase the total amount of TFA FTS bonds authorized to be outstanding above the City’s debt limit from $13.5 billion to $21.5 billion beginning on July 1, 2024, and $27.5 billion beginning on July 1, 2025.

The City’s remaining debt-incurring power, the difference between indebtedness (both contractual and funded by bond issuance) and the debt limit, is projected to decrease from $41.0 billion at the beginning of Fiscal Year 2025 to $33.2 billion at the beginning of Fiscal Year 2028. Remaining debt-incurring power as a percent of the debt limit is 29.9 percent on July 1, 2024, and is projected to decrease to 21.7 percent by July 1, 2027. Over this period, the debt limit is projected to grow at an average annual growth rate of 3.9 percent, while total indebtedness against the limit is projected to grow at an annual rate of 7.8 percent.

Remaining Debt-Incurring Power as of June 30th

At the beginning of a Fiscal Year, the remaining debt-incurring power reflects both changes in the debt limit and appropriations for GO principal. Over the course of the year, as capital contracts are entered into, the remaining debt-incurring power declines and reaches its minimum at the end of the Fiscal Year. Absent a decline in the debt limit, the remaining debt-incurring power increases at the beginning of the following year. Table 10 shows the projected debt-incurring power as of the end of the Fiscal Year through Fiscal Year 2028.

Using Office of the Comptroller’s projections as of the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget, projected remaining debt-incurring margin is expected to decline to $20.7 billion by Fiscal Year 2028, or approximately 13.5 percent of the projected general debt limit. Again, the amount of debt-incurring power is buoyed by the increase of the TFA statutory exemption, which increases by $6.0 billion, to $27.5 billion on July 1, 2025.

Table 10. Projected NYC Debt-Incurring Power as of June 30th

| Date | June 30, 2025 | June 30, 2026 | June 30, 2027 | June 30, 2028 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal Year ($ in billions) | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 |

| General Debt Limita (a) | $136.8 | $140.0 | $148.0 | $153.2 |

| Net GO Bonds Outstandingb | $45.7 | $49.0 | $52.9 | $57.0 |

| Plus: TFA Bonds above Statutory Exemptionc | $32.5 | $30.4 | $34.7 | $39.0 |

| Less: Excluded Debt | ($0.0) | ($0.0) | ($0.0) | ($0.0) |

| Debt Applicable to the Limit (b) | $78.1 | $79.3 | $87.6 | $95.9 |

| Contractual liability, land, and other liabilities (c) | $29.7 | $33.1 | $34.9 | $36.6 |

| Total Indebtedness (d) = (b) + (c) | $107.9 | $112.5 | $122.5 | $132.5 |

| Remaining Debt- Incurring Power (a) – (d) | $28.9 | $27.5 | $25.5 | $20.7 |

| As a % of the General Debt Limit | 21.1% | 19.6% | 17.2% | 13.5% |

Source: New York City Office of the Comptroller and select information from the Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Capital Commitment Plan and the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget

aNew York City Office of the Comptroller’s projections as of the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget

bNet adjusted for Original Issue Discount, GO bonds issued for the water and sewer system and Business Improvement District debt.

cIn April 2024 the TFA Act was amended to increase the total amount of TFA FTS bonds authorized to be outstanding above the City’s debt limit from $13.5 billion to $21.5 billion beginning on July 1, 2024, and $27.5 billion beginning on July 1, 2025.

Debt-Incurring Power: June 30th and July 1st Comparison

Table 11 combines beginning- and end-of-Fiscal Year estimates to show how the remaining debt-incurring margin is depleted through the year by the issuance of debt and new contractual commitments that remain unfunded. For instance, in Fiscal Year 2025 the remaining debt-incurring power started at $41.0 billion and is projected to decline to $28.9 billion by June 30, 2025.

Additional debt-incurring power is created at the beginning of Fiscal Year 2026 by i) the increase of the debt limit from $136.8 billion to $140.0 billion, ii) by the appropriation of funds for the reimbursement of GO principal (the full amount of the appropriation, $2.5 billion in this case, reduces outstanding debt on July 1st , and iii) an additional $6.0 billion of TFA statutory exemption, per the amendment of the TFA Act. After July 1, 2025, there is no additional TFA statutory exemption granted to the City, therefore future debt-incurring power moving from June 30th to July 1st is a result of the increase of the debt limit and appropriation of funds for reimbursement of GO principal.

The Office of the Comptroller projects the increases in debt-incurring power at the beginning of the Fiscal Years are smaller than the additional indebtedness within each year. Therefore, the remaining debt-incurring power drops from Fiscal Year 2025 to Fiscal Year 2028.

Table 11. Comparison of Beginning-and End of Fiscal Year Estimates

| Fiscal Year | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ($ in billions) | Beg. | End | Change | Beg. | End | Change | Beg. | End | Change | Beg. | End | Change |

| Debt limit | $136.8 | $136.8 | $0.0 | $140.0 | $140.0 | $0.0 | $148.0 | $148.0 | $0.0 | $153.2 | $153.2 | $0.0 |

| Debt | $67.3 | $78.1 | $10.8 | $69.7 | $79.3 | $9.7 | $76.9 | $87.6 | $10.7 | $85.1 | $95.9 | $10.8 |

| Contracts not funded | $28.5 | $29.7 | $1.3 | $29.7 | $33.1 | $3.4 | $33.1 | $34.9 | $1.8 | $34.9 | $36.6 | $1.7 |

| Total Indebtedness | $95.8 | $107.9 | $12.1 | $99.4 | $112.5 | $13.0 | $110.1 | $122.5 | $12.5 | $120.0 | $132.5 | $12.5 |

| Remaining debt-incurring power | $41.0 | $28.9 | ($12.1) | $40.5 | $27.5 | ($13.0) | $38.0 | $25.5 | ($12.5) | $33.2 | $20.7 | ($12.5) |

Source: New York City Office of the Comptroller and select information from the Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Capital Commitment Plan and the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget

Chart 1 shows the Office of the Comptroller’s projection of Fiscal Year-end debt-incurring margin through the end of Fiscal Year 2033. From the end of Fiscal Year 2024 the debt limit is projected to grow at an annual average rate of 3.7 percent through the end of Fiscal Year 2033. This rate is below the average annual growth rate of 5.2 percent observed between Fiscal Year 2014 and Fiscal Year 2024, and slightly above the annual growth rate of 3.1 percent observed since Fiscal Year 2020.

Assuming target commitments from the Fiscal Year 2025 Executive Capital Commitment Plan and debt issuance assumptions from the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget, remaining debt-incurring margin is projected to reach a low point of $13.5 billion at the end of Fiscal Year 2031 before slightly increasing the next two Fiscal Years to $14.4 billion at the end of Fiscal Year 2033. The estimates do not factor in offsets from the issuance of premium bonds nor the City’s capacity to issue debt that is not counted toward the limit through various entities, both of which alleviate the erosion of the remaining debt-incurring power.

Chart 1. Historical and Projected Debt-Incurring Power as of June 30th

Source: New York City Office of the Comptroller and select Capital Plan information from the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget released on June 30, 2024.

IV. Capital Commitments

Background

The Capital Commitment Plan published by NYC Office of Management and Budget is a compilation of estimated future contract registrations for all the City’s new construction, physical improvements and equipment purchases that meet capital eligibility requirements. Capital commitments derive from awarded contracts registered with the Office of the Comptroller. Commitments increase indebtedness irrespective of whether expenditures are incurred, or bonds are issued to fund capital projects. This planning document serves as the foundation for the registration of contracts from which future capital expenditures occur. The City’s Capital Commitment Plan is updated three times a year. The Adopted Capital Commitment Plan is typically released in September (referred to as the September Plan) with updates included with the Preliminary Budget (typically released in January) and the Executive Budget (typically released in April).

A capital commitment refers to a contract registration and does not represent a capital expenditure. Capital expenditures occur after a contract is registered, and the related spending against that contract can last several years. Capital expenditures are initially paid out of the General Fund and financing of capital projects takes place after spending occurs to reimburse the City’s General Fund. The City does not finance individual projects in isolation, but rather finances portions of multiple projects simultaneously with each bond issuance.

Fiscal Year 2025 September Capital Commitment Plan

On September 30, 2024, the City released the Fiscal Year 2025 September Capital Commitment Plan that sets forth projected capital investments for the current and future Fiscal Years. The City-funded share of the Fiscal Year 2025 September Commitment Plan’s authorized commitments over Fiscal Year 2025 through Fiscal Year 2028 totals $83.0 billion. This is a $8.5 billion increase from the Fiscal Year 2024 September Capital Commitment Plan. Non-City funding comes from state, federal, and private grants and accounts for only 4.2 percent of the total capital plan.

Five (of 10) programmatic areas comprise 69.0 percent of the City-funded plan, as shown below in Table 12. Education/CUNY related capital projects comprise 21.0 percent of the four-year plan, followed by Housing and Economic Development at 17.7 percent, Environmental Protection at 16.4 percent. Combined, these five areas account for $65.7 billion of the $83.0 billion authorized City-funded plan.

Table 12. September Capital Commitment Plan: Authorized City-Funded Capital Commitments, Fiscal Years 2025-2028

| Categories | Total Committed ($ in millions) | Percent of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Education/CUNY | $17,406 | 21.0% |

| Housing & Economic Development | $14,712 | 17.7% |

| Environmental Protectiona | $13,658 | 16.4% |

| Admin. Of Justice | $11,487 | 13.8% |

| DOT & Mass Transit | $8,469 | 10.2% |

| Other City Operations | $6,755 | 8.1% |

| Citywide Equipment | $4,967 | 6.0% |

| Parks | $3,230 | 3.9% |

| Hospitals | $1,877 | 2.3% |

| Computer Equipment | $481 | 0.6% |

| Total | $83,042 | 100.0% |

Source: NYC Office of Management and Budget, Fiscal Year 2025 September Capital Commitment Plan.

Note: Projects that are funded through NYW and do not count towards the City’s indebtedness.

Table 13 shows City-funded authorized commitments in the last four adopted plans, net of DEP commitments, which are funded through the City’s Water Authority and therefore do not count against the City’s indebtedness. Table 13 shows that in the current plan total authorized commitments, net of DEP, increased by $6.7 billion to $69.4 billion compared with the one year ago, a 10.0 percent increase. This marks a shift from the previous flat year-over-year trend in authorized commitments. Authorized commitments net of DEP, increased by just 1.0 percent between the Fiscal Year 2022 and Fiscal Year 2023 four-year plans and decreased by 4.0 percent between the Fiscal Year 2023 and Fiscal Year 2024 plans.

Table 13. Authorized Commitments, Net of DEP

| September Capital Commitment Plan | Authorized Commitments ($ in billions) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | FY 2027 | FY 2028 | Total | |

| FY 2022-2025 | $17.8 | $17.5 | $15.3 | $13.9 | $64.5 | |||

| FY 2023-2026 | $18.6 | $18.8 | $15.3 | $12.3 | $65.0 | |||

| FY 2024-2027 | $18.7 | $16.8 | $13.7 | $13.5 | $62.7 | |||

| FY 2025-2028 | $22.7 | $17.0 | $14.5 | $15.2 | $69.4 | |||

Source: NYC Office of Management and Budget

Note: Excludes non-city funded planned commitments.

In each year of the plan, the City sets a “reserve for unattained commitments,” which assumes that projects will move more slowly than reflected in the plan, and therefore some authorized commitments will be pushed outside the plan’s four-year window. These are known as “target commitments.” City-funded commitments, after adjusting for the reserve for unattained commitments of $9.8 billion, total $73.2 billion from fiscal 2025 through Fiscal Year 2028 in the September Capital Commitment Plan.

Net of DEP, target City-funded commitments in the current plan total $61.2 billion, an increase of $5.9 billion from the previous adopted plan, as shown in Table 14. Net of DEP, the September Capital Commitment Plan projects an average of $18.3 billion per year in City-funded target commitments Fiscal Year 2025 through Fiscal Year 2028. This represents an increase of over $1.9 billion from the annual average in last year’s September City-funds Plan of $16.4 billion. The City-funded portion of the Commitment Plan forecast, after the reserve for unattained capital commitments, is not front-loaded, with 24.6 percent of the commitments of the current four-year Plan scheduled in Fiscal Year 2025.[7]

Table 14. Target Commitments, Net of DEP

| September Capital Commitment Plan | Target Commitments ($ in billions) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | FY 2027 | FY 2028 | Total | |

| FY 2022-2025 | $11.6 | $15.4 | $15.4 | $14.4 | $56.8 | |||

| FY 2023-2026 | $12.1 | $16.5 | $15.7 | $13.5 | $57.7 | |||

| FY 2024-2027 | $12.1 | $15.2 | $14.2 | $13.8 | $55.3 | |||

| FY 2025-2028 | $14.8 | $16.2 | $15.1 | $15.1 | $61.2 | |||

Source: NYC Office of Management and Budget

Note: Excludes non-city funded planned commitments.

Table 15 shows the Office of the Comptroller’s projected gross additions to indebtedness based on the September Capital Commitment Plan.[8] Gross additions are target commitments plus other minor components (inter-fund agreements and the cost of bond issuance) as estimated by OMB, with Office of the Comptroller estimated adjustments to account for greater bond premiums and the Office’s higher capital commitment estimates.

Projected variance of actual commitments is the difference between the Office of the Comptroller’s target commitment estimations and OMB’s target commitments. Based on the growth trend of historical commitments, it is estimated that the City could commit $6.3 billion more than the OMB estimated target, which represents an average 110 percent commitment achievement rate over the Plan Years. The “NYC Debt Affordability Analysis” that appears in Section V of this report provides greater detail on how sustained variance between actual commitments and forecasted commitments (called achievement rate) impacts debt incurring power and debt affordability through to Fiscal Year 2034.

The City generally sells premium coupon bonds, meaning the purchase price is greater than par due to the bond’s coupon being higher than current market interest rates. The premium generated from bond sales is an offset to indebtedness that is also not included in the estimate of remaining debt-incurring power. As shown in Table 15, an assumed average issue premium of 5.0 percent could lessen the impact of projected debt issuance on debt-incurring power by $2.5 billion by Fiscal Year 2028.

Table 15. Projected Gross Additions to Indebtedness Fiscal Year 2025 to Fiscal Year 2028, as of September Capital Plan

| ($ in billions) | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | FY 2027 | FY 2028 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target commitment (a) | $14.8 | $16.2 | $15.1 | $15.1 | $61.2 |

| Inter-fund agreements and cost of bond issuance (b) | $0.4 | $0.5 | $0.5 | $0.5 | $1.9 |

| Gross additions to indebtedness (c) = (a) + (b) | $15.2 | $16.7 | $15.6 | $15.6 | $63.1 |

| Projected variance of actual commitments (d) | $0.8 | $0.2 | $2.2 | $3.1 | $6.3 |

| Assumed bond premium offset (e) | -$0.6 | -$0.6 | -$0.6 | $-0.7 | -$2.5 |

| Restated gross additions to indebtedness (c) + (d) | $15.3 | $16.3 | $17.2 | $18.0 | $66.9 |

Source: New York City Office of the Comptroller, NYC Office of Management and Budget

V. Debt Burden and Affordability of NYC Debt

This section presents measures to assess the size of the City’s debt burden and its affordability. No single measure completely captures debt affordability; hence the Office of the Comptroller employs several measures that can be used to assess a locality’s debt burden. The first portion of this section provides several measures: outstanding debt as a percent of personal income, debt service as a percent of local tax revenues, and debt service as a percent of total revenues. The Office of the Comptroller then presents a comparison of key debt affordably measures for three of these measures and comparisons with a peer group of other jurisdictions. The section concludes with an analysis of how various capital commitment achievement rates (or the percent of target commitments actually committed) applied to the Fiscal Year 2025 September Capital Commitment Plan and projected borrowing related could impact remaining debt-incurring power and overall debt affordability.

Upon release of the Fiscal Year 2025 Adopted Budget, the City, through its GO and TFA FTS credits, was projected to borrow an average $12.5 billion annually between Fiscal Year 2025 through Fiscal Year 2028, with the greatest estimated borrowing of $13.2 billion expected to occur in Fiscal Year 2028[9]. The Fiscal Year 2025 September Capital Commitment Plan increased capital commitments in Fiscal Years 2025 through 2028, which the Office of the Comptroller projects will also increase the amount of debt issuance over the same period.

This level of borrowing, if fully executed, may put increased pressure on the operating budget in the event tax revenues are lower and do not meet the Financial Plan’s expectations. In addition, there may be cautionary pressure on the City’s remaining debt-incurring power after Fiscal Year 2028 when capacity is projected to be lower than during the Financial Plan period.

Using updated commitment projections from the Fiscal Year 2025 September Capital Commitment Plan, the Office of the Comptroller’s projects debt service on GO and TFA FTS bonds grows at a compounded annual rate of 6.6 percent from Fiscal Year 2025 to Fiscal Year 2034, to $15.1 billion by Fiscal Year 2034, as illustrated in Chart 2.

It is worth noting, the rate of growth will likely be lower as the projection incorporates conservative long-term bond interest rate assumptions and does not consider the likelihood of refunding issues and/or lower than projected capital commitment (contract registration) rates. However, as discussed later in the report, should some combination of future capital commitments increase, commitments are incurred at a rate greater than projected or actual disbursements relative to the expected timeline accelerate, debt service could grow faster than currently projected.

Chart 2. Debt Service, Fiscal Year 2010 – Fiscal Year 2034

Source: Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports of the New York City Office of the Comptroller, Fiscal Years 2010 through 2024. In this measure of debt service, the New York City Office of the Comptroller includes servicing for GO, TFA FTS, Lease Purchase, and Net-Equity Contribution Adjustments. These are adjusted for prepayment. Note: Fiscal Years 2010 – 2024 are actuals. Fiscal Years 2025- 2034 are forecasts.

Debt Burden

NYC debt outstanding has increased from $69.5 billion to $104.1 billion, or 49.7 percent, from Fiscal Year 2010 through Fiscal Year 2024.[10] Over this same period, NYC personal income grew by 78.2 percent, NYC local tax revenues by 99.4 percent, and total revenues (including state and federal contributions) by 58.9 percent.[11] [12]

Debt Outstanding as a Percent of Personal Income, Fiscal Year 2010 – Fiscal Year 2028

One measure of debt affordability is debt outstanding as a percent of personal income. Chart 3 illustrates the historical and projected trend of gross debt outstanding as a percentage of personal income from Fiscal Year 2010 to Fiscal Year 2028. [13] This ratio has remained relatively steady over the historical period, ranging from a high of 16.6 percent in 2012 to a low of 13.0 percent projected in Fiscal Year 2024. The 1.1 percentage point drop between Fiscal Year 2020 and 2021 stems from a 7.1 percent increase in personal income combined with a 0.9 percent decrease in debt outstanding.

Chart 3. NYC Gross Debt as a Percent of Personal Income, Fiscal Year 2010 – Fiscal Year 2028

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, US Department of Commerce, Fiscal Years 2010 through 2023; Office of the Comptroller’s Debt Service and Tax Revenue Forecasts

Note: Fiscal Years 2010 – 2023 are actuals. Fiscal Years 2024 – 2034 are projected.

NYC Debt Service as a Percent of Tax Revenues

Another measure of debt affordability is annual debt service expressed as a percent of annual local tax revenues. This measure shows the pressure that debt service exerts on a municipality’s locally generated revenues. Oversight entities consider debt unaffordable once it exceeds 15 percent of tax revenue. New York City has not breached this measure of affordability since 2002. Chart 4 shows debt services as a percent of tax revenues since 2010, when debt service was 13.7 percent of tax revenue, this measure has since generally trended downwards, reaching a low of 9.9 percent in Fiscal Year 2022, before increasing slightly to 10.6 percent in Fiscal Year 2024. In this measure of debt service, the Office of the Comptroller includes funding for GO, TFA FTS, Lease Purchase, and Net-Equity Contribution Adjustments. These are adjusted for prepayment.

Debt service as a percentage of tax revenues is projected to climb over the four-year Fiscal Year 2025 to Fiscal Year 2028, reaching 13.0 percent in Fiscal Year 2028. Debt service as a percentage of tax revenues is projected to continue rising to 14.0 percent by the end of Fiscal Year 2033 before dropping to 13.9 percent in Fiscal Year 2034. This is driven by estimated 6.2 percent compounded annual growth of debt service growth from Fiscal Year 2025 to Fiscal Year 2028 compared to 3.6 percent compounded annual growth of local tax revenues over the same period.[14]

Chart 4. NYC Debt Service as a Percent of Tax Revenues

Source: Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports of the New York City Office of the Comptroller, Fiscal Years 2010 through 2024; Office of the Comptroller’s tax revenue forecast as of the June 2024 Financial Plan and Comptroller’s debt service forecast as of the September 2024 Capital Commitment Plan; and NYC Office of Management and Budget Debt Service Documentation

Note: Fiscal Years 2010 – 2024 are actuals. Fiscal Years 2025 – 2034 are projected.

Debt service as a percent of total revenues ranges from 6.7 percent to 8.2 percent over Fiscal Year 2010 through Fiscal Year 2024, as shown in Chart 5. Debt service in this measure differs from Chart 4 in that debt service associated with TFA BARBs (secured by New York State Building Aid) and TSASC Inc. debt (secured by tobacco settlement revenues) are included in addition to the other types of debt service. All are adjusted for prepayment. Over this period, this ratio averaged 7.6 percent. The ratio is forecast to reach 9.9 percent in FY 2028 due to a projected average annual growth rate of debt service exceeding the estimated average annual growth rate of total revenues by a margin of over 6.0 percentage points, 8.5 percent versus 2.5 percent, respectively, from Fiscal Year 2025 to Fiscal Year 2028.[15]

Chart 5. NYC Debt Service as a Percent of Total Revenues

Source: Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports of the New York City Office of the Comptroller, Fiscal Years 2010 through 2024; Office of the Comptroller’s revenue forecast as of the June 2024 Financial Plan and Comptroller’s debt service forecast as of the September 2024 Capital Commitment Plan; and NYC Office of Management and Budget Debt Service Documentation

Note: Fiscal Years 2010 – 2024 are actuals. Fiscal Years 2025 – 2028 are projected.

While New York City has a large amount of outstanding debt, its credit rating remains strong, as shown in Table 16. The rating agencies continue to cite the City’s large and diverse economy, strong financial management, and liquidity among positive credit attributes that support GO ratings. High TFA and NYW ratings reflect their strong legal frameworks and debt service coverage by pledged revenues.

Table 16. Ratings of Major New York City Debt Issuers

| Rating Agency | GO | TFA FTS Subordinatea | TFA BARBs | NYW First Resolution | NYW Second Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S&P | AA | AAA | AA | AAA | AA+ |

| Moody’s | Aa2 | Aa1 | Aa2 | Aa1 | Aa1 |

| Fitch | AA | AAA | AA | AA+ | AA+ |

| Kroll | AA+ | Not Rated | Not Rated | Not Rated | Not Rated |

a There are currently no TFA FTS Senior Bonds outstanding

Comparison with Selected Municipalities[16]

New York City is the largest city in the U.S., with a population over twice as large as that of second ranked Los Angeles, and a complex, varied, and aging infrastructure. The city has more school buildings, firehouses, health facilities, community colleges, roads and bridges, libraries, and police precincts than any other city in the nation. Moreover, NYC has broader responsibilities than the majority of other large cities in the U.S. These responsibilities include city, county, and school district functions and, as a result, NYC has similarities to many county governments. Responsibilities for various functions in other large U.S. cities generally are distributed broadly to state, county, school districts, public improvement districts, and public authority governmental units. NYC has responsibility for all of these functions.

Selection of the Peer Group

NYC has important features that pose challenges when attempting to identify peers among other U.S. cities and in drawing useful comparisons. One of these is its sheer scale and density, including population, infrastructure, and economic activity relative to other large U.S. cities. The other feature to consider is NYC government’s broad scope of responsibilities, an important difference that distinguishes itself from virtually all of its potential peers. Therefore, when selecting an appropriate peer group for the City, it is important to consider both scale and governance. Differences in scale and governance can be partially mitigated with ratio analysis, similar to the efforts of rating agencies, and by using, where appropriate, Direct and Overlapping Debt, in order to address differences in governance structure, when measuring debt burden and debt affordability. As discussed in more detail below, Direct and Overlapping debt includes not only the debt of the peer city, but also other debt (for example, issued by school districts) supported by taxpayers in that jurisdiction.

The Peer Group includes the top 10 most populous U.S. cities, representing different regions and a variety of infrastructure life cycles, and then expanded by adding cities that were both highly ranked in population (that is, ranking at least among the top 25 nationally) which also assumed city and county functions along with direct responsibility for funding and financing their schools.

While NYC may have more in common with other international financial and commercial centers, such as London, Paris, Shanghai, Seoul, Tokyo and others in terms of population and level of business and cultural vibrancy, these were not considered for inclusion in the Peer Group because of the lack of direct comparability in terms of legal structure, funding sources, budgeting, accounting and financing practices.

The Peer Group is shown in Table 17, along with each city’s credit ratings, population, and governing functions and responsibilities.

Table 17. New York City Peer Group Identified for Comparisons

| City | Moody’s | S&P | Fitch | Kroll | Population | City & County Functions | GO School Funding & Borrowing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | National Rank | |||||||

| New York City | Aa2 | AA | AA | AA+ | 8,335,897 | 1 | Yes | Yes |

| Los Angeles | Aa2 | AA | AAA | AA+ | 3,802,725 | 2 | No | No |

| Chicago | Baa3 | BBB+ | A- | A | 2,746,388 | 3 | No | No |

| Houston | Aa3 | AA | AA | – | 2,288,250 | 4 | No | No |

| Phoenix | Aa1 | AA+ | AAA | – | 1,657,035 | 5 | No | No |

| Philadelphia | A1 | A | A+ | – | 1,567,258 | 6 | Yes | No |

| San Antonio | Aaa | AAA | AA+ | – | 1,481,496 | 7 | No | No |

| San Diego | Aa2 | AA | AA+ | – | 1,374,790 | 8 | No | No |

| Dallas | A1 | AA- | AA | AA+ | 1,300,239 | 9 | No | No |

| Austin | Aa1 | AAA | AA+ | – | 981,610 | 10 | No | No |

| San Francisco | Aa1 | AAA | AAA | – | 808,437 | 17 | Yes | No |

| Nashville | Aa2 | AA+ | – | AA+ | 708,144 | 21 | Yes | Yes |

| Washington DC | Aaa | AA+ | AA+ | – | 670,949 | 23 | Yes | Yes |

| Boston | Aaa | AAA | – | – | 650,706 | 25 | Yesa | Yes |

a Formerly consolidated with Suffolk County, MA; county government abolished in 1999.

Source: Population as of 2022; derived from Fiscal Year 2023 ACFRs of each city. Ratings sourced from publicly available credit reports as of October 24, 2024.

Metrics Selected for Comparison between NYC and the Peer Group

The Peer Group metrics provided herein utilize data and calculations from each Peer Group member’s Annual Comprehensive Financial Report (ACFR). Although some of the nuances specific to each city are difficult to conform, the ACFRs provide the most comparable and readily available data. Additionally, when comparing debt metrics between jurisdictions it is important to obtain the data from uniform sources wherever possible. Using the table of Direct and Overlapping Debt from each Peer Group member’s ACFR ensures greater comparability because this table provides the total amount of GO and other property tax levy supported debt obligations that are imposed upon the taxpayers of each Peer Group member, regardless of governance structure. For example, if the Peer Group comparisons utilized Direct Debt rather than Direct and Overlapping Debt, the Chicago Board of Education’s debt would be excluded from Chicago’s calculations since it is a separate entity from City of Chicago and finances its own capital program. As a result, comparability between Chicago and NYC would be reduced because NYC directly finances the capital program for NYC Public Schools, the largest school district in the nation, which is an integral part of the City’s reporting entity and included in its Direct Debt.