Audit of the Behavioral Health Emergency Assistance Response Division’s Effectiveness in Responding to Individuals with Mental Health Crises and Meeting Its Goals

Audit Impact

Summary of Findings

The Behavioral Health Emergency Assistance Response Division (B-HEARD) pilot program is limited in its hours of operation, its geographic distribution, and in the types of calls considered eligible for a response. This means that many people who may need a B-HEARD team are instead provided a “traditional response,” consisting of New York City Police Department (NYPD) officers and an ambulance with two Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs).

During the scope period of the audit, only crises that occurred within the 31 precincts of the pilot and during the 9am to 1am hours of operation were routed to the New York City Fire Department’ Emergency Medical Services (FDNY EMS) for a possible B-HEARD response. Over 14,000 calls determined to be eligible for a B-HEARD team did not receive one because the calls were received during the overnight hours, when the pilot does not operate.

In addition, 13,042 (35%) of the 37,113 calls determined to be eligible for B-HEARD did not receive program services. The reasons these calls did not receive services cannot be discerned because the Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health (OCMH)—which administers the program—does not track this information.

According to OCMH, the program received a total of 96,291 mental health calls within the pilot areas and the program’s hours of operation between Fiscal Years 2022 and 2024. Of these, 59,178 calls (over 60%) were considered “ineligible” for a B-HEARD response by OCMH. However, this number includes not only calls that were assessed and determined ineligible, but all calls that could not be triaged for some reason, which included cases when an FDNY EMS operator was not available to take the call.

The auditors found that OCMH’s overall tracking of program and performance data is inadequate. Therefore, the agency has limited assurance that the goals of the program are being met. OCMH does not track the reasons calls are not triaged for a B-HEARD response, why eligible B-HEARD calls do not result in a B-HEARD response, or whether calls assessed for a traditional response subsequently resulted in a request for a B-HEARD team.

OCMH does not track the reasons B-HEARD teams do not conduct mental health assessments at the scene, as required, or whether individuals in crisis receive treatment after the initial intervention (in instances when the individual did not refuse treatment). This means that OCMH cannot monitor trends or measure the level of its success in increasing patient connection to community-based care, one key goal of the program.

Intended Benefits

This audit assessed the ability of the B-HEARD pilot to provide mental health emergency assistance to New Yorkers dealing with a non-violent mental health crisis and whether program goals are being met and recommends improvements.

Introduction

Background

History of the NYPD and Mental Health Calls

According to a 2015 report by the Treatment Advocacy Center, people with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed by law enforcement. This is further supported by a study conducted by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions and Vanderbilt University, which examined a total of 10,308 incidents involving police shootings between 2015 to 2020 and found that 23% (2,404) of the shootings were associated with individuals that had mental or behavioral health conditions.

Over the years, many violent confrontations between NYPD and individuals experiencing mental health crises have been documented.[1]

- On October 18, 2016, Deborah Danner, age 66, was fatally shot by NYPD officers who were called to the scene by a neighbor claiming that Danner was acting erratically. An emergency medical technician who arrived at the scene first was talking to Danner and had succeeded in getting her to put down a pair of scissors and baseball bat; however, when NYPD arrived, she picked them back up. In response, NYPD shot and fatally wounded her.

- On January 21, 2022, Lashawn McNeil, a 47-year-old Harlem resident with a history of mental illness, was fatally shot, as were two police officers. The victim’s mother dialed 911 from her Harlem apartment to report that her son had threatened her, but made no mention of weapons or violence, or claim that she was at risk of immediate harm. Three police officers arrived at the scene and gunfire ensued, leading to the deaths of McNeil and two officers. In a press conference response to the incident, Mayor Eric Adams stated that mental health professionals should be the first line of response to potential non-violent mental health emergencies.

- On March 27, 2024, Win Rozario age 19, was fatally shot by NYPD, who were called to the scene by the victim himself, while he was having a mental health emergency. His younger brother warned the two officers who arrived at the scene that Rozario was having an episode. Police officers found Rozario standing in the kitchen with his mother nearby. When an officer moved toward the kitchen, Rozario became distressed and picked up a pair of kitchen scissors, which his mother tried to take from his hand. An officer initially shot him with a taser gun several times; however, when Rozario was still holding onto the scissors, another officer fired his gun at least four times, fatally wounding Rozario, less than two minutes from the time the officers entered the family’s home.

B-HEARD was established as a pilot program in 2021 and is intended to provide that “first line of response” referred to by Mayor Adams. B-HEARD is a City initiative that sends social workers and EMTs to mental health crisis 911 calls, instead of police officers. Studies such as those mentioned above, as well as a 2021 article published in the New England Journal of Medicine in combination with real life incidents, have shown that an armed police presence can escalate mental health situations, and individuals experiencing a mental health crisis often require support from trained mental health professionals, rather than law enforcement. [2]

The B-HEARD program is a departure from the traditional police response to mental health crises, which typically consists of a team of uniformed NYPD officers and a basic life support unit from FDNY’s Emergency Medical Services (EMS) division, who receive minimal training to treat people with mental health issues. The program reflects the City’s attempt to treat mental health emergencies as a health issue, not a public safety problem.

B-HEARD: An Alternative to Traditional Responses

B-HEARD is described as a “health-centered” response to 911 mental health calls. In this context, “health-centered” (or “patient-centered”) means that first responders prioritize the needs and preferences of the person experiencing a mental health crisis.

The goals of the B-HEARD program are to: (1) route 911 mental health calls to a health-centered B-HEARD response whenever appropriate; (2) reduce unnecessary use of police resources; (3) increase connection to community-based care; and (4) reduce unnecessary transport to hospitals.[3] The stated intention of the program is to build trust and respect, and to empower patients to make informed decisions about their health. B-HEARD was developed as a coordinated effort by FDNY EMS, New York City Health + Hospitals (H+H), NYPD, and OCMH to respond to mental health emergencies, consisting of mental health professionals (H+H social workers) specially trained to deescalate situations and provide help to people experiencing mental health crises—also referred to by program officials as “emotionally disturbed persons” (EDP).[4]

B-HEARD teams include two FDNY EMTs/paramedics and a mental health professional from H+H. B-HEARD teams are intended to be dispatched as first responders to individuals experiencing mental health emergencies or to incidents involving emotionally disturbed individuals, when there is no known weapon involved or no known imminent risk of harm to self or others.[5] B-HEARD responders must be state-licensed social workers, which requires a Master’s degree that includes 900 hours of internship experience, as well as four weeks of training with EMS responders. This contrasts with NYPD officers, most of whom receive just one week of crisis intervention training during their six months in the Academy.

B-HEARD teams are expected to use their physical and mental health expertise, as well as their experience in crisis response, to deescalate emergency situations and provide immediate care. These teams can respond to a range of behavioral health problems, such as suicidal ideation, substance misuse, and mental health conditions (including serious mental illnesses), as well as physical health problems, which can be exacerbated by mental health problems.

Organizational Structure of the B-HEARD Program

OCMH is responsible for providing programmatic oversight over the B-HEARD program, which includes regular meetings with the B-HEARD staff leads at the operational agencies that implement and support the B-HEARD program. According to OCMH, the office also works closely with agency partners (NYPD, FDNY, and H+H) to identify ways to refine the program and develop necessary programmatic changes to improve operations, monitor how the program is operating, respond to press and media inquiries, and publish all public-facing aspects of the program, such as statistics on OCMH’s website on a variable basis.

The program itself is run by staff from FDNY EMS and H+H social workers, which collectively comprise the B-HEARD teams. FDNY and H+H also manage the teams and provide training and ongoing support.[6] NYPD is only expected to get involved if there is a threat of violence (e.g., if a B-HEARD team is sent to respond to a 911 call and, upon arrival, they deem the situation dangerous/threatening, they can call for assistance from NYPD). If a B-HEARD team is not available to respond to a call that has been deemed eligible, a traditional response is sent, consisting of NYPD officers and an ambulance with two EMT paramedics. The circumstances under which eligible calls do not receive a B-HEARD response are explained in further detail below.

From 911 Call to B-HEARD Response

NYPD and FDNY EMS have established a process for handling EDP calls received by 911 and for determining whether a B-HEARD response is appropriate. (See Appendix I for a flow chart detailing the process.) All emergency calls are initially received by NYPD 911 call-takers who determine the nature of the emergency.[7] If an EDP is involved, operators are trained to ask the following series of questions:[8]

- Does the person have an emotionally disturbed history?

- Is the person acting in a rational manner or in a manner that may lead to violence towards themself or others?

- Is the person depressed or suicidal?

- Does the person have weapons or are they acting violent?

- Is the person being influenced by any drugs or alcohol?

NYPD call-takers enter the responses into the Intergraph Computer-Aided Dispatch (ICAD) system and assign a corresponding call type based on the type of emergency.[9]

- If the caller does not require medical or mental aid, the NYPD call-taker transfers the information to an NYPD radio dispatcher, who sends out police officers to respond.

- If the caller expresses any type of medical or mental health issue, the NYPD call-taker transfers the call to an FDNY EMS call-taker while remaining on the line. Information entered by the NYPD call-taker into the ICAD system is transferred to the FDNY’s Emergency Medical System for Computer Aided Dispatch (EMSCAD) system. [10]

There are four stages maintained by FDNY in its EMSCAD system: (1) Initial, (2) Triage, (3) Dispatch, and (4) Final.[11] The responses to the initial questions asked by the NYPD call-taker are transferred automatically into the EMSCAD system.

The FDNY EMS call-taker is responsible for triaging the call by asking the caller a series of questions generated by a Computerized Triage Algorithm (CTA), gathering as much information as possible. This information includes location, nature of the emergency, gender, age, and complaint.[12] The call-taker is also responsible for categorizing the call using codes that denote the call type. Based on the FDNY EMS triage and call type assigned during the triage stage, an FDNY EMS dispatcher sends the designated unit.[13] Calls that include violence, weapons, or imminent threat of harm are coded as an EDPC call type and receive a traditional response, as do calls that involve a health care provider, who is at the scene, and has determined that the person needs to be transported to a hospital (coded as an EDPE call type). Calls that are coded as an EDP-M call type should receive a response from a B-HEARD team.

According to OCMH all calls should be triaged. However, if a call goes unanswered by FDNY EMS or a caller disconnects, the call remains with NYPD. These are categorized as EDP call types because they are not triaged by FDNY EMS. The B-HEARD response to EDP calls has varied over time; between June and December of 2021, and again from June 2024 to the present, EDP calls have resulted in a traditional response. Between December 2021 and June 2024, a mixed traditional and B-HEARD team were dispatched. See Table 1 below for call type codes and the corresponding response.

Table 1: FDNY EMS Call Types, Descriptions, and Associated Responses

| Call Type | Description | Associated Response |

|---|---|---|

| Emotionally Disturbed Patient Critical (EDPC) | Patient is currently violent, suicidal/homicidal, or has a weapon | Traditional Response |

| Emotionally Disturbed Patient Mental (EDP-M) | Patient not known to have a weapon and not currently known to be an imminent threat to themself or others | B-HEARD Team |

| Emotionally Disturbed Person (EDP) | The call has not been triaged and/or not all information is known (prior to triage or during triage)[14] | (a) Traditional Response from 6/6/2021 to 12/12/2021

(b) Mixed B-HEARD Team and Traditional Response from 12/13/2021 to 6/30/2024[15] (c) Traditional Response from 6/30/2024 to Present[16] |

| Emotionally Disturbed Person Evaluation (EDPE)[17] | The call involved a health care provider, who is at the scene, conducted a mental health assessment, and determined that the person needs to be transported to a hospital. | Traditional Response |

The combined total numbers of publicly reported B-HEARD calls and responses for Fiscal Years 2022, 2023, and 2024 were as follows:

- Mental health 911 calls received within B-HEARD areas: 96,291

- Total number of calls deemed eligible for a B-HEARD response: 37,113

- Total number of mental health 911 calls that received a B-HEARD response: 24,071[18]

The B-HEARD Response

When a B-HEARD team responds and arrives at the scene of an emergency, the team is expected to work with the person in need of assistance and, if appropriate, other involved parties. The team uses their experience with crisis response to help deescalate situations, if needed. They conduct physical and mental health assessments and can provide on-site assistance, including but not limited to connecting the person to their existing medical and/or mental health providers, crisis counseling, or, with their consent, connecting them to follow-up services or to a program that can provide long-term care. B-HEARD teams may help individuals access substance abuse programs, therapy, and even medication refills.

Since each call is different and involves individuals suffering from various forms of mental illness, a B-HEARD team can spend 40 minutes or more on a call. If a B-HEARD team determines that they are unable to handle the emergency or assist the individual, the team requests from dispatch either a unit to transport the patient to a hospital or police officers to arrive to the scene for assistance.

As of June 26, 2024, the B-HEARD program operates 18 teams in 31 (40%) of the 78 precincts across four boroughs (Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx); there is no coverage in Staten Island. The program also covers areas within a 30-minute drive of each unit’s location.[19] (See Appendix II for the full listing of precincts.) Teams are on call Monday through Sunday, between the hours of 9am and 1am. FDNY EMS assigns teams to either a day shift or a night shift, with only nine teams operating per shift.[20] According to OCMH, the program’s budget for Fiscal Year 2024 was $35.9 million ($24.9 million for FDNY; $11 million for H+H). For Fiscal Year 2025, the budget is $35.3 million ($22.8 million for FDNY; $12.5 million for H+H).

While there is a stated commitment to expansion, there are no current plans to increase the scope of the pilot.

Patient Survey Results

H+H administers patient experience surveys to those who accepted services from B-HEARD teams. According to H+H, from August 15, 2023 to March 31, 2025, the program surveyed 1,126 of the 5,500 patients who received a mental health assessment from a B-HEARD team (20% response rate), with the following results:[21]

- 99% of respondents felt B-HEARD treated them with courtesy and respect (1,124 responded to this question).

- 98% of respondents felt that the B-HEARD team explained things in a way that they could understand (1,123 responded to this question).

- 96% of respondents felt that B-HEARD helped them (1,122 responded to this question)

- 92% of those who had received an EMS response in the past felt that the B-HEARD response was more appropriate for their needs (395 out of the patients who had received EMS services in the past responded to this question).[22]

This information was not verified by the auditors.

Objectives

The objectives of this audit were to determine whether the goals of the B-HEARD program are being met, as well as the degree to which the program is effectively serving patients.

Discussion of Audit Results with OCMH, FDNY, H+H, and NYPD (B-HEARD Program Officials)

The matters covered in this report were discussed with B-HEARD program officials during and at the conclusion of this audit. An Exit Conference Summary was sent to B-HEARD program officials and discussed at an Exit Conference held on April 10, 2024, and April 14, 2024. On April 25, 2024, we submitted a Draft Report to B-HEARD program officials with a request for written comments. We received a written response from B-HEARD officials on May 9, 2025, which included written comments from all four agencies.[23]

In its response, OCMH agreed with three recommendations (#1, #3, #7), disagreed with one (#5), and stated partial disagreement with three (#2, #4, #6). However, in response to one of these (#6), OCMH’s response indicates agreement when taken as a whole. Although all recommendations were addressed to OCMH, FDNY also provided responses, which oddly, do not fully agree with OCMH’s.

Despite OCMH’s apparent agreement with many of the recommendations, OCMH disputed any need for increased program oversight or for improved metrics.[24] OCMH also asserted that many of the issues identified by the audit were outside of their purview and/or the program goals. The auditors strenuously disagree. The program’s effectiveness is fundamentally undermined by its inability to accept and triage all calls, to provide B-HEARD services to all calls that have been deemed eligible for B-HEARD services, and to accurately measure performance and to assess trends that would facilitate future improvements. These are essential to B-HEARD’s success and must be addressed to ensure services are provided to New Yorkers in need. Moreover, OCMH sits within the Mayor’s Office which has operational purview over all agencies and their programs.

In its response to the Draft Report, OCMH claims that the audit did not address the comprehensive points raised during the 3.5-hour Exit Conference, and that corrections to the report were not fully incorporated. However, OCMH is disingenuous in its response. The auditors fully considered all points and made considerable edits to the draft report.

B-HEARD program officials’ written responses have been fully considered and, where relevant, changes and comments have been added to the report.

The full text of B-HEARD’s responses is included as an addendum to this report.

Detailed Findings

The audit found that the B-HEARD pilot program is limited in its hours of operation, its geographic distribution, and in the types of calls considered eligible for a B-HEARD response, leaving many in need with a traditional response.

During the scope period of the audit, only crises that occurred within the 31 precincts of the pilot and during the hours of operation between 9am and 1am were routed to FDNY EMS to determine eligibility for B-HEARD. Over 14,000 calls determined to be eligible for a B-HEARD team response received a traditional response because they were received during the overnight hours, when the pilot does not operate.

Of the 96,291 mental health calls that were received within the pilot areas and the program’s hours of operation between Fiscal Years 2022 and 2024, 59,178 calls (over 60%) were considered “ineligible” for a B-HEARD response. During FY2024, this included not only calls that were considered potentially dangerous (call type EDPC) or considered ineligible because a mental health professional was already at the scene (call type EDPE, which was revised at the end of FY24), but also calls that were originally routed for triaging but could not be triaged, either because an FDNY EMS call-taker did not take the call, or because all necessary information could not be collected (call type EDP). In other words, the number of calls deemed ineligible included calls that might have been eligible had they been successfully triaged.

Of the remaining 37,113 calls assessed as eligible for a B-HEARD response (call type EDP-M), 24,071 (65%) resulted in a B-HEARD team being dispatched. This means that 13,042 people eligible for B-HEARD (35%) failed to receive program services. This is in addition to the 14,200 eligible calls that came in outside the program’s hours of operation.

The audit found the program’s data collection and performance measures are in need of significant improvement.[25] OCMH does not adequately or effectively assess B-HEARD’s performance and has only limited assurance that the goals of the program are being met. For example, OCMH does not track:

- the reasons calls are not triaged for a B-HEARD response;

- why eligible B-HEARD calls do not result in a B-HEARD response;

- whether calls responded to by NYPD subsequently result in a request for a B-HEARD team;

- why B-HEARD teams did not conduct mental health assessments at the scene, as required by program standards; or

- whether individuals in crisis receive treatment after the initial intervention (in instances when the individual did not refuse treatment). This makes it impossible for OCMH to determine if the program has increased patient connection to community-based care, one of the program’s core objectives.

These weaknesses—and others discussed below—cast serious doubts on the efficacy of this program.

B-HEARD’s Scope is Very Limited: Staffing, Geography, Hours of Operation, and Call Type All Hinder B-HEARD Responses

Two Shifts Are Split Between Just 18 Teams

As of March 2025, there are just 18 B-HEARD teams responding to mental health emergencies, covering two shifts. The number of teams appears to be insufficient to cover all B-HEARD eligible calls. More than a third (35%) of all calls considered eligible for a B-HEARD response—totaling 13,042 calls during the audit scope period—did not receive one.

According to agency officials, this is mostly due to the unavailability of B-HEARD teams; for example, available teams may be responding to other calls. However, there is no data to confirm the accuracy of this statement. OCMH does not track why a B-HEARD team is not sent once the call has been triaged and confirmed to be eligible for a B-HEARD response. This makes it difficult for OCMH to determine how many teams are needed to respond to all calls eligible for a B-HEARD response.

Agency officials claim that they regularly evaluate their staffing to meet the needs of the B-HEARD program, but they were unable to produce the results of these evaluations, claiming that they had no formal analysis “due to the dynamic nature of the pilot.” They acknowledge that they have conducted no analysis to determine how many B-HEARD teams and how much funding would be required to ensure that the program effectively serves all B-HEARD eligible calls, or to expand the program in line with overall need.

Over 14,000 B-HEARD Eligible Calls Came in Outside the Program’s Hours of Operation

B-HEARD teams are only active 16 hours a day—between the hours of 9am and 1am. According to FDNY and OCMH, this timeframe was selected based on an analysis of EDP calls, which found that the highest volume of calls occurred during this window. Although the percentage of calls received between 1am and 9am (the hours not covered by B-HEARD) is lower than at other times, the total volume of calls received during this window is significant. Between January 2022 and September 2024 14,200 eligible mental health calls received a traditional response simply because coverage was not provided overnight. See Table 2 below.

The 14,200 calls that fall into this category are in addition to the 13,042 B-HEARD-eligible calls received between FY2022 and FFY2024 that were within the program’s hours of operations, but that did not receive a B-HEARD response (see further below). Thus, the number of eligible calls that did not receive a B-HEARD response totals over 27,000.

Table 2: Number of EDP Calls Received Outside of B-HEARD Operational Hours[26]

| Calendar Year | Number of Mental Health Calls Received Outside of B-HEARD Hours of Operation | Number of Mental Health Calls Received Outside of B-HEARD Hours of Operation that were Deemed Eligible |

|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 27,780 | 5,720 |

| 2023 | 27,044 | 4,828 |

| 2024[27] | 18,898 | 3,652 |

| Total | 73,722 | 14,200 |

B-HEARD Covers Just 40% of City Precincts, None of Which Are in Staten Island

In addition to limited hours of operation, the program does not cover all precincts, and there are no B-HEARD teams assigned to Staten Island. The B-HEARD program is currently active in 31 (40%) of the 78 precincts in the City. (See Appendix II for a list of precincts). The map below, published on the OCMH website, shows the areas where B-HEARD is currently active, shaded in both dark blue and light blue. The light blue shading represents the areas added (Precincts 43, 45, 47, 49, 50, and 52) as of the second quarter of FY2024.

According to program administrators, precincts covered by the pilot were selected because they had the highest volume of EDP calls. As of June 2024, the precinct boundaries for B-HEARD teams have been eliminated; however, B-HEARD teams will only respond to EDP calls outside of the 31 active precincts if they are located less than 30 minutes from the closest available team. If a B-HEARD team is more than 30 minutes away, they are assigned a traditional response. As noted above, OCMH does not track or report the number of calls that cannot be served due to location. Lack of funding and difficulty finding qualified staff were cited as impediments to expansion of the program.

Figure 1: Map of Active B-HEARD Precincts

OCMH Does Not Track Reasons Mental Health Crises Are Considered Outside the Scope of the B-HEARD Pilot

Only mental health call types categorized as EDP-M are considered eligible to receive a B-HEARD response. All other call types within the pilot—EDPC, EDP, and EDPE—currently receive a traditional response. Between 2022 and 2024 the percentage of calls considered ineligible for a B-HEARD response has fluctuated.

As shown below in Table 3, the percentage of mental health calls eligible for a B-HEARD response has increased overall during the reporting period—from 31% to a peak of 40%—but the percentage of calls not considered eligible after triage, or attempted triage (EDP calls), persistently remains over 60%. This occurs for a variety of reasons, including the involvement of violence, FDNY EMS not picking up the call, insufficient information gathered during the call, an outside physician making an assessment, or a B-HEARD team not being available to respond.

OCMH does not track ineligible calls by reason and lacks data that would shed light on why calls are not triaged at all, or when only partial information is collected. This makes it difficult to evaluate why so many individuals with mental health crises within the pilot area and hours of program operation are not receiving support from trained mental health professionals.[28]

Understanding why certain calls are not eligible for a B-HEARD response is crucial to assess total need and program performance, as well as to identify areas where changes may be needed. It would also help OCMH to determine whether additional call-takers, or enhanced training for existing staff, are needed.

Table 3: Total Number of Mental Health Calls in B-HEARD Areas and Percentages Eligible for a B-HEARD Response[29]

| Time Period | Total Number of Mental Health 911 Calls in B-HEARD Area | Total Number of Calls Eligible for a B-HEARD Response | Percentage of Mental Health Calls Eligible for a B-HEARD Response | Total Number of Calls Not Eligible for a B-HEARD Response | Percentage of Mental Health Calls Not Eligible for a B-HEARD Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022 | 10,920 | 3,391 | 31% | 7,529 | 69% |

| July 1, 2022 to June30, 2023 | 34,042 | 13,181 | 39% | 20,861 | 61% |

| July 1, 2023 to June 30, 2024 | 51,329 | 20,541 | 40% | 30,788 | 60% |

OCMH stressed that B-HEARD remains a pilot program and indicated that more resources would be needed to become fully operational or expand.

Calls Not Triaged or Lacking Complete Information Are Ineligible for a B-HEARD Response

Triage is the process that allows FDNY EMS to assess whether a 911 mental health call warrants the response of a B-HEARD team. As explained previously, based on the call type assigned during the triage stage, an FDNY EMS dispatcher dispatches the designated unit—a B-HEARD team or a traditional response.

However, calls are not triaged when (1) an EMS call-taker is not available to answer a call after it is routed by an NYPD call-taker; or (2) the caller hangs up prior to the triage process or does not have all the information (e.g., a third-party caller).[30] In these cases, the call is categorized as EDP (not all information is known and/or call has not been triaged) and an EMS dispatcher automatically assigns a traditional response instead of a B-HEARD response.

Mixed Response or Traditional Response for EDP Calls

Over time, OCMH’s policy changed regarding calls coded as EDP call types―meaning calls routed to FDNY EMS because they potentially warranted a B-HEARD response but were not triaged. As shown above in Table 3, between June and December 2021 and from June 2024 to the present, traditional teams respond to EDP calls. For the period from January to June 2024, EDP-coded call types generated a mixed response, consisting of both a traditional team and a B-HEARD team.

According to OCMH, the practice of sending a mixed response was changed back to a traditional response after June 2024 because the lack of triage made it difficult to determine whether the emergency warranted a B-HEARD team.[31] Agency officials stated that the addition of EDP calls to the eligibility list also created a new set of challenges, because the limited information conveyed to call-takers resulted in the need for NYPD officers to accompany B-HEARD teams for safety reasons. The program administrators also expressed concern that providing a B-HEARD team for EDP calls reduces the number of teams available to respond to calls confirmed eligible for a B-HEARD response (EDP-M calls).

Since EDP call types no longer receive a B-HEARD response, the lack of triage once again results in a traditional response from responders who do not have the same degree of training to deal with a mental health crisis as a B-HEARD team. Typically, these encounters result in transports to the emergency room as opposed to on-site treatment.

B-HEARD is Inconsistent in Providing Intended Services

Over 13,000 Eligible Calls Did Not Receive a B-HEARD Response

Based on the available data, although 24,071 calls received a B-HEARD response, 13,042 of the calls received between 2022 and 2024 that were triaged and determined eligible for a B-HEARD response did not receive one. This data is shown below in Table 4.

Table 4: Number of Eligible Calls and Responses[32]

| Fiscal Year | Calls Eligible for a B-HEARD Response | Calls that Received a B-HEARD Response | Percentage of Eligible Calls Responded to by B-HEARD | Calls that Did Not Receive a B-HEARD Response | Percentage of Eligible Calls Not Responded to by B-HEARD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 3,391 | 1,933 | 57% | 1,458 | 43% |

| 2023 | 13,181 | 7,187 | 55% | 5,994 | 45% |

| 2024 | 20,541 | 14,951 | 73% | 5,590 | 27% |

| Total | 37,113 | 24,071 | 65% | 13,042 | 35% |

The percentage of eligible calls that received a B-HEARD response varied from 55% to 73% during the last three fiscal years. Since the inception of the program, B-HEARD teams have responded to 65% of all calls that were eligible for a B-HEARD response—conversely, 35% of all eligible calls received a traditional response.

OCMH does not track the reasons B-HEARD eligible calls do not receive a B-HEARD response, but the lack of adequate resources is likely one reason. The program does not have enough B-HEARD teams to cover calls when teams are responding to other calls, on breaks, or when exigent circumstances (such as vehicles with mechanical issues) take teams out of commission.

The Percentage of Mental Health Assessments Conducted by B-HEARD Teams is Falling

When responding to a call involving an emotionally disturbed person, B-HEARD teams are expected to conduct on-site physical and mental/behavioral health assessments and provide on-site assistance, such as connecting the person with their existing medical and/or mental health provider, crisis counseling, and connecting them to follow-up services.[33] Care provided by B-HEARD teams offers people in crisis immediate health-centered assessments from trained medical and mental health professionals.

Despite this expectation, many calls responded to by B-HEARD teams did not result in mental health assessments. Although the number of mental health assessments has increased since 2022, the percentage of mental health assessments conducted has decreased over time. During FY2022, only 55% of the calls that B-HEARD teams responded to resulted in a mental health assessment of the patient. This number decreased to 31% in FY2023 and 25% in FY2024—decreases of 24% and 30%, respectively, from FY2022. See Table 5 below.[34]

OCMH does not track the specific reasons mental health assessments were not conducted.[35] It appears the decrease may be due to decreasing contact between B-HEARD teams and patients. Based on the data published during FY2024, B-HEARD made contact with patients during just 50% of the calls to which B-HEARD teams responded. Program administrators attributed the infrequency of contact to the fact that patients leave the scene or refuse contact. In addition, individuals do not always meet the criteria for a mental health assessment, which includes giving priority and precedence to medical emergencies over mental health assessments.[36]

The fact that the percentage of assessments is decreasing indicates that the program is not meeting one of its standards.[37] OCMH needs to try to increase the percentage of mental health assessments to gain an understanding of the patient’s behavioral health so that appropriate referrals can be made. The first step in doing so is to track when and why assessments are not completed. This may help identify ways for B-HEARD teams to increase the number of mental health assessments.[38]

Table 5: Number of Times B-HEARD Teams Conducted Mental Health Assessments for Eligible Mental Health Calls

| Fiscal Year | Number of Mental Health Calls to which B-HEARD Teams Responded | Number of Mental or Behavioral Health Assessments Conducted (Percentage of Eligible Calls where a Mental or Behavioral Health Assessments Conducted) |

|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 1,933 | 1,059 (55%) |

| 2023 | 7,187 | 2,250 (31%) |

| 2024 | 14,951 | 3,691 (25%) |

| Total | 24,071 | 7,000 (29%) |

Lack of Community-Based Care Centers Limits B-HEARD’s Efficacy

The goals of the B-HEARD program include reducing unnecessary hospitalizations and ensuring that people in need are connected to appropriate community-based care. One example of community-based care is Support and Connection centers.[39] These centers were established by the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice and are overseen by the City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH). The centers are intended to provide ongoing mental health services to individuals who require mental health assistance.

Initially, there were two Support and Connection centers: East Harlem Support and Connection Center (operated by Project Renewal) and Bronx Support and Connection Center (operated by Samaritan Daytop Village). However, the Bronx Support and Connection Center closed in May 2024, leaving only one location open. While the East Harlem Support and Connection Center can accept referrals from any borough, the total available capacity to provide support has decreased and individuals referred to East Harlem potentially have farther to travel from their homes.

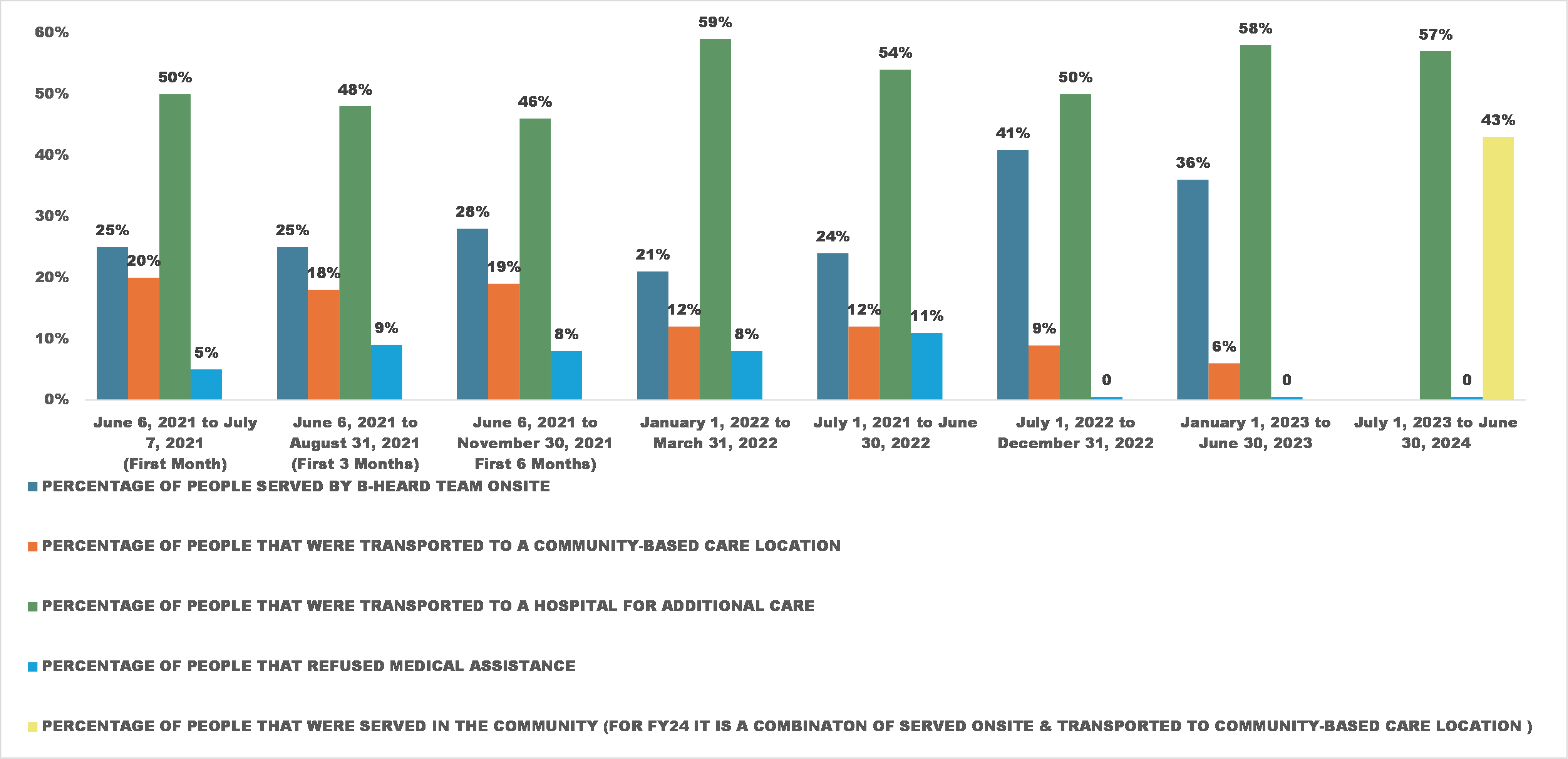

Despite the program goal of limiting unnecessary transports to hospitals, the auditors’ review of data published by OCMH found a decline in the percentage of patients transported to community-based care—from 10% between July 1 and December 31, 2022, to 6% between January 1 and June 30, 2023—and an 8% increase in the number of people taken instead to a hospital over the same period (see Chart 1 below; full data briefs are shown in Appendix III).[40]

When asked about this decline, program officials attributed it to the increase in the number of calls that were not triaged (EDP).

Chart 1: B-HEARD Patient Outcomes Based on Data Briefs in Pilot Areas when Mental Health Assessments were Conducted

In responding to the Draft Report, OCMH took exception to the auditors’ conclusion that the efficacy of the program was impacted by the reduction in available community care centers. In its response, OCMH listed other options that patients have in lieu of the centers, but this contradicts the position of OCMH and other program leaders during the audit, who consistently expressed the need for additional centers. This sentiment was also echoed during the Exit Conference, where OCMH agreed that having only one center in the City hindered the efficacy of the program. OCMH’s written response to the Draft Report also acknowledged that “many behavioral health programs lack the resources to provide care in an acute crisis.”

OCMH Does Not Adequately Assess Program’s Performance or Effectiveness

According to §4.5 of Comptroller’s Directive 1, a sound internal control system “must be supported by ongoing activity monitoring occurring at various organizational levels and during normal operations. Such monitoring should be performed continually and be ingrained throughout an agency’s operations.” In addition, §5.2 of the Directive states that “management, throughout the organization, should be comparing actual functional or activity level performance data to planned or expected results, analyzing significant variances and introducing corrective action as appropriate.”

OCMH is responsible for overseeing, tracking, and assessing the B-HEARD program’s performance. This includes working closely with agency partners, monitoring the program, and publishing briefs with statistics on the OCMH website. OCMH collects data from FDNY and H+H and uses that data to compile and post to its website briefs of 911 mental health calls and dispositions over a six- to 12-month period.

The data briefs prepared by OCMH include the following: (1) number of calls eligible for a B-HEARD response; (2) total number of 911 mental health calls; (3) number of calls that received a B-HEARD response; (4) rate of patient satisfaction with the H+H social workers’ treatment; (5) number of calls the B-HEARD team was able to treat (only reported in the most recent data brief published in FY2024); and (6) the number of emotionally disturbed persons transported to hospitals and community-based centers.

However, the audit found that OCMH and its partner agencies do not, overall, collect sufficient evidence to assess the program’s effectiveness against its stated goals.[41] The program does not review, analyze, or monitor the number of ineligible mental health calls it receives by reason of ineligibility, nor the potentially eligible calls that were not triaged.[42] In addition, the program does not evaluate or quantify the specific reasons a B-HEARD eligible call does not receive a response from a B-HEARD team (and instead receives a traditional response). It also does not quantify the specific reasons contact was not made or a mental health assessment was not conducted when B-HEARD teams do respond.

OCMH stated that, from the start of the program until October 2022, it did track reasons B-HEARD teams did not respond to all calls and based on its prior oversight efforts, they made changes to the program. However, OCMH also stated that as the program expanded, it became increasingly difficult to do so, especially since this information must be manually pulled by FDNY—a task that is seen by FDNY as too tedious and time-consuming to undertake.

During the Exit Conference, OCMH claimed that it was already aware of the general reasons calls are not triaged or eligible calls are not responded to, and stated that, given the expansion of the program, it does not believe that tracking the specific reasons was an appropriate use of its resources. The auditors disagree. Without tracking the reasons calls could not be triaged or why a B-HEARD team was not sent when the need for one was established, OCMH is not able to assess the size of the unmet need for B-HEARD assistance, or to assess how the program could be improved. This is also a matter of transparency; stakeholders should be able to assess the program’s success based on data.

As noted further below, OCMH does not capture changes in coding based on what happens after a response team is sent, assess the number of times NYPD requests a B-HEARD team from the scene, or track outcomes after initial intervention by a B-HEARD team.

OCMH Does Not Ensure that FDNY EMS Changes Coding After Response

OCMH tracks B-HEARD eligibility based on the call code assigned by FDNY EMS; however, circumstances of a call can change at any point in time. For example, if the dispatch call type for an emergency is classified as EDP-M (B-HEARD eligible), but the B-HEARD team arrives on the scene and determines that the emotionally disturbed person has a weapon, the B-HEARD team will request that NYPD officers respond. At this point, the emergency should be reclassified as EDPC, which does not qualify for a B-HEARD team response.

FDNY stated that it routinely advises EMS staff to provide the dispatcher with the updated status of a call when the initial call types do not match what the responders encounter on the scene; however, FDNY could not confirm that this was standard practice. In the above example, if the dispatcher or responder does not update the call type, OCMH would mistakenly count and report the call as a B-HEARD-eligible call, ultimately (if inadvertently) inflating the numbers and skewing program analysis.

Conversely, when NYPD and EMS paramedics arrive at the scene of an emergency initially categorized as not eligible for a B-HEARD response and determine that a B-HEARD team response would be more appropriate, the call should be reclassified as EDP-M—the call type used for non-threatening calls. If the call type is not changed to reflect the situation at the scene, OCMH mistakenly counts and reports the call as an ineligible B-HEARD call. Again, this ultimately causes an inadvertent underreporting of the numbers and skews program analysis. As with the prior scenario, FDNY could not confirm whether the EMS staff were routinely notifying the dispatchers, or whether the dispatchers were in fact updating the call types in the system.

During the Exit Conference, FDNY officials stated that they try to limit the radio communications with EMS dispatchers to an emergency-only basis—to keep the radio lines open for emergency needs. However, updating the call types is not limited to communications through radio lines. EMS dispatchers can be updated with the final status of the call type through other means of communication, or even after assistance is rendered. Accurately updating the final call type is essential to assessing the needs of the program and to reporting meaningful data to the public.

OCMH Does Not Track the Number of Times NYPD Requests On-Site Assistance from a B-HEARD Team

When NYPD is sent to a potentially eligible B-HEARD call (for example, one that was not handled by a B-HEARD team because of coverage or triaging issues), officers can request a B-HEARD team from dispatch if they feel that B-HEARD would be better equipped to deal with the crisis. In these situations, NYPD’s response to the call is a potential waste of resources; given the fact that avoiding such waste is a core goal of the program, this information should be, but is not, tracked.

During the first six months of the program’s operation, NYPD was responsible for tracking and providing statistics to OCMH regarding the number of times NYPD requested on-site assistance from a B-HEARD team. However, NYPD’s tracking was done manually, and due to the expansion of the B-HEARD program, collection of this information ceased.

NYPD generally uses the ICAD system to capture data about 911 calls, but the system’s functionality in relation to the B-HEARD program is limited. For example, the ICAD system lacks any codes that would allow NYPD to identify calls that received a B-HEARD response or calls where NYPD officers requested a B-HEARD team, making data extraction and analysis even more difficult. In the absence of such codes, users must enter and collect information from the detailed notes section of each EDP call individually, making it impractical to analyze key information.[43]

When asked whether NYPD intended to create a code to capture situations in which NYPD requests on-site assistance from B-HEARD, NYPD responded that it would be a tedious process involving other agencies, and that it has no intention of creating such a code.[44] In the absence of accurate, sufficient metrics to determine the reduction of unnecessary police resources attributed to the B-HEARD program, neither OCMH nor any other entity can assess whether police resources are used unnecessarily—again, a key goal of the program. Tracking the number of times that police officers responded to a call that was more appropriate for a B-HEARD response would help to better evaluate the needs and goals of the program, including the reduction of unnecessary use of police resources.

OCMH Does Not Track Whether Individuals Receive Treatment After the Initial Crisis Intervention

The reason B-HEARD responds to 911 calls is to provide emergency behavioral health responses and intervention within minutes to individuals experiencing a mental health emergency. B-HEARD teams refer patients to community-based resources when called for, and follow-up care is provided by the community-based provider.

However, OCMH lacks a dedicated system to track whether referrals to community-based programs were utilized and whether clients received treatment. Therefore, it is unable to monitor trends or measure success against this core objective.

According to information on OCMH’s website, individuals served by B-HEARD are offered follow-up care from the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s (DOHMH) Health Engagement and Assessment Teams, the Department of Homeless Services’ (DHS) outreach teams, and various hospital-based programs, but the rate at which these connections result in care is not tracked. Coordinating with these external sources could help OCMH track the individuals who participate in referrals and would help the agency assess the effectiveness of this part of the program.

The absence of a dedicated system to track the utilization of referrals to community-based programs can result in a disconnect between initial intervention and long-term care. By addressing these gaps with improved coordination, expanded resources, and improved data tracking, the B-HEARD program could better serve people in need of mental health support and ensure that patients receive the appropriate care post-crisis.

Recommendations

To address the abovementioned findings, the auditors propose that OCMH should:

- Formally assess the Citywide need for B-HEARD mental health response teams.

OCMH Response: OCMH agreed with this recommendation.

- Work with partner agencies to expand the reach of the program and the number of B-HEARD teams in line with established need, and to cover the overnight hours.

OCMH Response: OCMH partially agreed with this this recommendation, stating “as part of our ongoing efforts to assess the need for citywide expansion, we will continue to prioritize resources based on the identified needs, and the potential for overnight coverage will be carefully evaluated as part of this assessment to ensure responsible and sustainable growth.”

Auditor Comment: The data demonstrates a clear need for program expansion in two areas: 14,000 calls came in outside of hours, and in addition, over 13,000 calls assessed as B-HEARD eligible were not served. According to OCMH this was likely due to insufficient teams to meet program needs. Increasing hours of operation and the number of teams would surely improve program effectiveness.

- Work with FDNY to explore additional methods (e.g., tuition assistance, livable wages or loan forgiveness) for recruiting additional qualified EMS responders needed to ensure that all eligible calls are triaged and responded to.

OCMH Response: OCMH agreed with this recommendation.

- Work with partner agencies to develop appropriate performance metrics and ensure data necessary to fully evaluate program performance against its goals is collected. This includes:

- The number of ineligible calls received by reason of ineligibility;

- The reasons B-HEARD eligible calls do not receive a B-HEARD response or are not triaged;

- The number of times NYPD responds to a non-violent EDP call due to the unavailability of B-HEARD teams; and

- Quantifying the number of times and the specific reasons contact is not made and/or mental health assessments are not performed when a B-HEARD team responds.

OCMH Response: OCMH partially agreed with this recommendation, stating that “FDNY continues to provide data on the number of ineligible calls received for the B-HEARD program. In addition, OCMH will work with FDNY to identify instances where a traditional response (NYPD and EMS) is dispatched due to the unavailability of B-HEARD units. We also agree to work with FDNY and New York Health + Hospitals to track the number of instances and the reasons mental health assessments are not conducted during B-HEARD team responses.

However, OCMH does not agree with the recommendation to collaborate with partner agencies to develop performance metrics and collect data on the reasons for call ineligibility or untriaged 911 calls. These areas fall outside the scope of the B-HEARD program and are more appropriately addressed within the broader 911 operations framework by FDNY, not OCMH.”

Auditor Comment: OCMH’s willingness to improve some data capture is positive, however, OCMH’s opposition to developing performance metrics and collecting data on the reasons for call ineligibility or untriaged 911 calls is unfortunate. It is also contradictory, given its earlier statement that it is “continuing to assess the factors influencing call eligibility is crucial for ongoing program improvement.” The two are connected. We urge OCMH to reconsider its position.

- Work with FDNY to establish the requirement that EMS responders consistently update the final call type on every call, to more accurately and reliably quantify the number of eligible calls received, irrespective of the methods of communication used to update the call types.

OCMH Response: OCMH disagreed with this recommendation, stating, “this recommendation reflects a misunderstanding of 911 call system operations, a point FDNY has repeatedly clarified regarding its infeasibility. Additionally, this type of recommendation falls outside the scope of the B-HEARD program and OCMH’s oversight role.”

Auditor Comment: OCMH uses call types to report to the public the number of calls received, as well as eligibility status. Updating the call types to reflect the final scenario would ensure that accurate figures are reported to the public. We also note that FDNY recognized the need for this improvement in its response, stating that “we will explore ways to better identify ‘final’ call types more accurately potentially through epcr (electronic patient care reports) data.”

- Continue to develop and implement innovative ways to increase contact with and conduct assessments of patients when B-HEARD teams respond.

OCMH Response: OCMH partially agreed with this this recommendation, stating “We agree with the objective of increasing patient contact and mental health assessments during B-HEARD responses and have consistently worked with B-HEARD agency partners to address this objective. … While we continue to explore and test innovative deployment strategies, it is important to acknowledge that improving patient contact during emergency responses remains a broader system-wide challenge. … Despite these limitations, our focus remains on deploying teams to calls where there is the greatest likelihood of connecting with individuals in crisis and providing timely, on-site support.”

Auditor Comment: OCMH’s response appears to agree with this recommendation.

- Continue to work with the New York State Office of Mental Health and Health Department to expand the network of community-based care centers across all five boroughs. This would provide equitable access to post-crisis mental health services, regardless of geographic location.

OCMH Response: OCMH agreed with this recommendation

Recommendations Follow-up

Follow-up will be conducted periodically to determine the implementation status of each recommendation contained in this report. Agency reported status updates are reported in the Audit Recommendations Tracker available here: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/services/for-the-public/audit/audit-recommendations-tracker/

Scope and Methodology

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (GAGAS). GAGAS requires that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions within the context of our audit objective(s). This audit was conducted in accordance with the audit responsibilities of the City Comptroller as set forth in Chapter 5, §93, of the New York City Charter.

The scope of this audit was January 1, 2022 through September 30, 2024.

- To obtain an understanding of B-HEARD’s operations, as well as OCMH’s involvement in designing, maintaining, and overseeing the B-HEARD program, auditors reviewed: The Office of Community Mental Health’s website

- OCMH Organizational Chart

- H+H Organizational Chart – B-HEARD Mental Health Response Team Reporting Structure as of 9/1/23

- FDNY Organization Chart in relation to the B-HEARD program

- NYPD Organizational Chart in relation to the B-HEARD program

- NYPD Operation Orders Related to B-HEARD: Operation Order Number 42 (Issued 9/28/23), Operation Order Number 53 (Issued 10/24/22), Operation Order Number 17 (Issued 4/4/23)

- EMS OGP 106-34, which sets forth the policy and procedure for the B-HEARD program

- NYC Health + Hospitals B-HEARD Policies, Protocols, Procedures, Requirements, Guidelines

- Classification of call types assigned to 911 mental health calls

- H+H EPIC System disposition data for CYs 2022 and 2023

- Data maintained in EMSCAD pertaining to B-HEARD for CYs 2022, 2023 and January 1, 2024 through September 30, 2024

- Publicly posted data briefs on OCMH’s website

To obtain an understanding of the program and its oversight, the auditors interviewed the following officials and staff of the B-HEARD program:

NYPD: Chief for the Interagency Operations Bureau, Captain for the Interagency Operations Bureau, Lieutenant for the Interagency Operations Bureau, Sergeant for the Interagency Operations Bureau, Captain for the Communications Division, Principal for the Communications Division, and Chief for the Information Technology Bureau.

FDNY: Deputy General Counsel/Director, Health Law, Manager of Bureau of Technology Development and Systems, Assistant Chief of EMS Operations, the Deputy Assistant Chief of EMS Operations, the Deputy Chief of EMS Operations, the Deputy Medical Director of Office of Medical Affairs, an Emergency Medical Dispatch Instructor for FDNY/EMS, and the Senior Advisor of the Management Analysis and Planning (MAP).

H+H: Senior Corporate Health Project Advisor for the Masters of Public Administration (MPA) Behavioral Health Administration, Assistant Vice President for the MPA Behavioral Health Administration, Medical Director for Behavioral Health, Director of Operations for Behavioral Health, and the Senior Project Manager for Behavioral Health.

OCMH: Deputy Executive Director for the Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health.

The audit also focused on understanding the role of each agency, assessing communication and data integration between the agencies’ computer systems, and identifying opportunities for improvement to optimize the response to mental health emergencies.

To understand how the NYPD’s systems integrated with B-HEARD processes and whether data was communicated effectively across all the agencies, auditors observed the NYPD’s INET and ICAD Systems and analyzed the processes and procedures followed by 911 call-takers, particularly in identifying and categorizing mental health emergencies. Auditors also interviewed EMS 911 call-takers and reviewed the EMS CAD System to ascertain how EMS dispatchers respond to emergency calls, and how information was recorded and relayed to field responders for the B-HEARD patients. Auditors evaluated FDNY’s Emergency Medical Dispatch (EMD) protocols and how they affected the integration of mental health responses and its data. Auditors explored the role of H+H and observed its computer system (EPIC) in determining its role in providing data related to mental health crisis responses.

Auditors analyzed the FDNY’S MAP unit’s data in managing mental health emergencies and ensuring efficiencies of the data. Auditors assessed the accuracy of the EMSCAD system by comparing FDNY and NYPD data and identifying duplicates within the dataset.[45] Auditors reviewed the data for completeness of the EMSCAD system to ensure that the dataset contained all CAD ID numbers. Subsequently, the audit team analyzed EMSCAD datasets to identify the number of EDP calls that occurred within and outside of B-HEARD operating hours during CYs 2022 and 2023. The audit team also analyzed EMSCAD datasets to identify the number of call types categorized as EDP and EDP-M for CYs 2022 and 2023, as well as EMSCAD datasets to identify the number of call types categorized as EDP, EDP-M for CY2024.

The auditors conducted a meeting with all agencies to evaluate the flow of information and identify any gaps in data sharing or communication that could hinder or delay the mental health response. Following that meeting, the auditors held discussions with all four of the agencies focused on identifying systemic barriers to seamless information sharing between agencies.

The combined results of the analyses and conclusions above, based on the collection of information and interviews with officials, provide sufficient and reliable evidence to support the audit’s findings and conclusions on the B-HEARD program.

Appendix I

Flowchart of the B-HEARD Process

Note: In its response to the Draft Report, FDNY suggested adding additional information in the flowchart that was intentionally omitted for simplification.

Appendix II

Precincts Covered by the B-HEARD Program

| Borough | Precinct | Total Precincts within Each Borough with B-HEARD Teams |

|---|---|---|

| Manhattan | 25, 26, 28, 30, 32, 33, 34 | 7 |

| Bronx | 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 52 | 12 |

| Brooklyn | 63, 67, 69, 71, 73, 75, | 6 |

| Queens | 104, 108, 110, 112, 114, 115 | 6 |

| 31 |

Appendix III

Statistical Data Reported by OCMH

| Time Period | Total Mental Health 911 Calls in B-HEARD Area | Total Number of Calls to which a B-HEARD Team Was Routed[46] | Total Number of Mental Health 911 Calls in Area that Received a B-HEARD Response | *Percentage/Number of People Served by B-HEARD On-site | *Percentage/Number of Clients Transported to a Mental Health Support Center[47] | *Percentage/Numbers of People Transported to a Hospital for Additional Care | *Percentage/ Number of People who Refused Medical Assistance | Number of Times NYPD Requested On-site Assistance from B-HEARD | Number of Times B-HEARD Team Requested Assistance from NYPD | B-HEARD Teams Reached People in Need on Average (MINUTES) | Everyone Served by B-HEARD Was Offered Follow-up Care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 6, 2021 to July 7, 2021 | 552 | 138 | 107 (78%) | 25% | 20% | 50% | 5% | 14 | 7 | UNREPORTED | YES |

| June 6, 2021 to August 31, 2021 | 1,487 | 342 | 283 (83%) | 25% | 18% | 48% | 9% | 44 | 18 | 12 | YES |

| June 6, 2021 to November 30, 2021 | 3,109 | 684 | 564 (82%) | 28% | 19% | 46% | 8% | 72 | 34 | 14 | YES |

| January 1, 2022 to March 31, 2022 | 2,400 | 561 | 383 (68%) | 21% | 12% | 59% | 8% | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED | 14 | YES |

| July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022 | 10,823 | 2,381 | 1,729 (73%) | 24% | 12% | 54% | 11% | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED | 16 | YES |

| July 1, 2022 to December 31, 2022 | 13,350 | 3,948 | 2,092 (53%) |

39% (Q1) 42% (Q2) |

12% (Q1) 7% (Q2) |

49% (Q1) 51% (Q2) |

UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED |

| January 1, 2023 to June 30, 2023 | 20,692 | 9,253 | 5,095 (55%) | 36% | 6% | 58% | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED |

| July 1, 2023 to June 30, 2024 | 51,329 | 20,451 | 14,951 (73%) | UNREPORTED | 43% (1,584)** | 57% (2,107) | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED | UNREPORTED |

* The data reported in Appendix III is based on the data briefs issued by OCMH in previous years. OCMH only reported percentages, not numbers for all periods except FY2024 (July 1,2023 to June 30, 2024).

**For FY2024, OCMH’s reported data did not delineate between the percentage/number of people served by B-HEARD on-site and the percentage/number of clients transported to a Mental Health Support Center. Instead, OCMH reported the combined figures under the title “Served in the Community.” For illustrative purposes, we placed this figure under the column titled Percentage/Number of Clients Transported to a Mental Health Support Center

Addendum

Endnotes

[1] In its response to the Draft Report, NYPD argued that these three incidents were outside the scope of the audit and asked that they be removed. However, the program resulted from a continuous need that first arose several years prior to the scope of the audit. These incidents provide context and help to highlight why the B-HEARD program was created, and what can happen when such services are not provided.

[2] Decoupling Crisis Response from Policing — A Step Toward Equitable Psychiatric Emergency Services. The article highlights how “police responses to psychiatric crises harm patients far too often, especially in minority communities, where a long history of institutional racism informs warranted distrust of law enforcement.” The article goes on to state that “continued reliance on police as mental health first responders in Black and other minority communities leads directly to unnecessary injuries and deaths and increases the stigma against seeking treatment by fostering distrust of health care institutions, thereby limiting access to necessary mental health services.”

[3] The Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health views transport to a hospital emergency room as “unnecessary” if patients would be able to remain in their communities to receive care.

[4] A mental health professional is someone who has significant experience with mental health crises and is trained jointly to use their physical and mental health expertise and experience in crisis response to assess and deescalate emergency situations.

[5] A mental health emergency is defined as a non-life-threatening situation, in which a person experiences an intense behavioral, emotional, or psychiatric response that may be triggered by a precipitating event. The person may be at risk of harm to themself or others, disoriented or out of touch with reality, functionally compromised, or otherwise agitated and unable to be calmed. According to information on OCMH’s website, “risk of harm” could mean the person has suicidal ideations or thoughts of harming others, but the person does not have a weapon and does not seem ready to act on those thoughts.

[6] FDNY provides training and support to EMS staff and H+H does the same for the social workers.

[7] In its response to the Draft Report, NYPD claims the audit “asserts that NYPD call-takers determine whether a call involves an EDP. The report clearly reflects that NYPD call-takers’ task is to determine whether EMS involvement is warranted. The auditors also note, however, that NYPD does have a call type for emergencies that involve an emotionally disturbed person, and its policies and procedures clearly outline the steps call takers should take to process and handle EDP calls.

[8] During the audit scope period, mental health calls outside of the pilot area were handled by NYPD and two EMTs arriving in an FDNY ambulance. While these calls were routed to FDNY EMS for triaging, they did not receive a B-HEARD response. As of June 2024, the program expanded to include mental health calls situated within a 30-minute drive from the unit’s location.

[9] NYPD has developed codes that are assigned based on the reasons for the call. For example, a call regarding an emotionally disturbed person will be assigned the code 054E. In its response to the Draft Report, NYPD erroneously—and contradicting what was shared with the audit team during the audit—claimed that code 054E was not the correct code. When the team followed up with NYPD, the agency acknowledged that “the comptroller’s statement is correct, the 054E code is utilized for a person who may be experiencing an emotional and mental health crisis.”

[10] In response to the Draft Report, NYPD claimed, in contrast to what was shared during the audit, that NYPD’s notes within ICAD are not transferred to FDNY EMS. However, when asked to clarify, NYPD acknowledged that “limited information is automatically shared between the individual dispatching systems.”

[11] Initial: The call type used based on information collected by NYPD.

Triage: The call type assigned by the Computerized Triage Algorithm (CTA).

Dispatch: The status of the call type at the time of dispatch.

Final: The call type used at the conclusion of the response to the emergency. If a B-HEARD team arrives to the scene and the individual is no longer present, the call type remains the same as it was at the time of dispatch.

It should be noted that a call type can be updated in any of the stages, if needed.

[12] The CTA questions were prepared by the Office of Medical Affairs within FDNY.

[13] The call type assigned at the dispatch stage will only differ from the triage stage if new information regarding the emergency is learned prior to sending responders. Once responders arrive at the scene of the emergency and assess the situation, a final call type is assigned at the conclusion of the assignment by EMS dispatch based on information shared by the responding team. Depending on the final outcome during treatment, a different call type may be assigned than the one assigned during the prior stages.

[14] Calls can be made by a third party, such as a neighbor, family member, health care provider (until July 2024 when a separate category was created for calls from health care providers) or individual experiencing the crisis. In these cases, the caller either hung up or did not know all needed information; this can occur prior to triage (so the call does not make it to the triage process) or during triage.

[15] On December 22, 2021, a manual process was initiated to assign EDP calls to B-HEARD units in Zone 7 and 8 only – both zones are in Harlem. On December 12, 2022, this process was automated through changes to the CAD system and applied to all operational areas to recommend B-HEARD units for EDP calls.

[16] During most of the audit scope period, EDP call types were assigned mixed B-HEARD/Traditional Responses. Since June 2024, these call types have reverted to exclusively Traditional Responses.

[17] The EDPE call type was created and started being used as of July 1, 2024. Prior to then, calls made by a health care provider were part of the EDP call type.

[18] The data shows that over 13,000 calls that were eligible for a B-HEARD response did not receive a B-HEARD team. This is addressed in the findings sections below.

[19] The precincts were selected based on areas with the highest volume of EDP calls. However, as of June 2024, the precinct boundaries for B-HEARD teams have been eliminated.

[20] Day shifts are from 9am to 5pm and night shifts are from 5pm to 1am.

[21] Of note, not every patient who accepted services from a B-HEARD team responded to the survey, and not every individual surveyed answered all of the survey questions.

[22] 403 respondents stated that they had received assistance from EMS in the past.

[23] Several of the program officials’ comments appear to be based on language in the Exit Conference Summary (ECS) that did not appear in the Draft Report to which they were responding. For example, OCMH stated that, “The report’s implication that any mental health call not responded to by B-HEARD constitutes a failure.” FDNY echoed the same sentiment in its response, stating that “the report implies that any mental health call not responded to by BHEARD is a failure of the program.” FDNY also incorrectly claimed that “the report implies that patients transported to an emergency department are failures of the program.” This information was also removed from the draft report. In any case, the auditors note in this respect that connection to community-based care—rather than hospital emergency rooms—is one of the stated goals of the program.

[24] Although the recommendations were addressed directly to OCMH, FDNY also responded to five of the recommendations—agreeing with the first four recommendations and partially agreeing with recommendation five (the recommendation that OCMH disagreed with). FDNY deferred to OCMH on the last two recommendations.

[25] In its response to the Draft Report, FDNY states, “the report implies that lack of follow up and outcome metrics are a failure of the BHEARD program. This issue is not unique to the BHEARD program. It is also a systemic issue with EMS overall…” However, the fact that this is a known ongoing and systemic issue does not mean that it should continue to go uncorrected.

[26] Calls received after the hours of operation are still triaged. These 14,200 calls were triaged and deemed eligible for a B-HEARD response.

[27] The audit team requested the 2024 data in October 2024. The team received the data for January 1, 2024 through September 30, 2024; therefore, the results for 2024 are representative of this time period.

[28] In its response to the Draft Report, and in an attempt to refute this finding, OCMH reiterated that not all mental health emergency calls are eligible for a B-HEARD response, and further, that this is why B-HEARD resources are strategically deployed only to calls that have been triaged and determined to be likely to benefit from a B-HEARD response. Both facts appear in this report and are undisputed.

[29] The statistics reported in Table 3 are based on the summary data tables published by OCMH in Fiscal Year 2024. OCMH only reports on calls received within hours of operations.

[30] There are two other reasons calls might not be triaged: (1) a B-HEARD team may be flagged down to respond and a call is not placed; or (2) NYPD may request assistance through dispatch. However, in both scenarios, the individual with the mental health crisis would receive a B-HEARD response.

[31] Programmatic decisions about B-HEARD are made jointly by FDNY EMS and H+H, with sign-off and agreement by OCMH.

[32] The data in this table does not include instances where calls came in after hours or from outside the program’s operational areas.

[33] In its response to the Draft Report, H+H asserts that it is “inaccurate to state that B-HEARD teams are ‘required’ to

conduct mental health assessments once they are on the scene, as per the program’s standards” and goes on to list the scenarios in which a patient will not receive an assessment, all of which are indicated in footnote #36 in the report. As acknowledged in the report, there are certain instances where an assessment cannot be conducted. However, the percentage of assessments conducted is falling and the reasons a mental health assessment was not conducted are not tracked. Neither H+H nor any other partner can provide the percentage of assessments that were not conducted for acceptable reasons.

[34] In its response to the Draft Report, OCMH took exception to the statement that the “percentage” of mental health assessments is falling, indicating that it is providing more mental health assessments year over year. The report clearly acknowledges that the number of mental health assessments has increased since 2022. However, the program’s success rate in conducting mental health assessments is declining.

[35] In its response to the Draft Report, H+H claims that “explaining why a mental health assessment did not take place will not increase the number of mental health assessments.” However, it may help H+H identify ways to engage clients and ensure that clients do not leave the scene. It would also validate H+H’s speculation that assessments were not conducted for good reason; this is completely unknown at this stage.

[36] The patient will not receive a mental health assessment in the following instances: the patient has an urgent medical issue that needs to be addressed, the patient is less than six years old, the patient does not have consent from a legal guardian to have a mental health assessment done, or the patient is in the custody of NYPD or the Department of Correction (DOC).

[37] In its response to the Draft Report, OCMH references changes to the program (namely the removal of EDP call types as eligible for a B-HEARD response) and criticizes the audit for omitting the changes from its analysis. However, the changes to the program were made in June 24, 2024. At the time the analysis was conducted, OCMH had only reported data through June 2024, so an assessment of the impact of any changes made to the program could not be conducted.

[38] In its response to the Draft Report, OCMH acknowledged that the percentage of calls resulting in a mental health assessment has declined; however, it attributed the percentage drop “to a much larger denominator—an increase in the total number of 911 mental health calls B-HEARD teams were dispatched to as the program expanded.” One of the goals of the B-HEARD program is to increase connection to community-based care, which cannot be accomplished unless mental health assessments are conducted.

[39] Other examples of community-based treatment include outpatient client, mobile-crisis teams, connecting to NYC Well, crisis respite, as well as connecting an individual with a prior provider.

[40] Within the FY2024 data briefs, OCMH did not report data on the number of individuals served on site by a B-HEARD team, transported to community care facilities or the number of individuals who refused assistance.

[41] The stated goals of the B-HEARD program are to: (1) route 911 mental health calls to a health-centered B-HEARD response whenever appropriate; (2) reduce unnecessary use of police resources; (3) increase connection to community-based care; and (4) reduce unnecessary transport to hospitals.