Audit Report on the Department of Social Services’ Administration of the Pandemic Food Reserve Emergency Distribution Program

To the Residents of the City of New York:

My office has audited the New York City Department of Social Services’ (DSS) Administration of the Pandemic Food Reserve Emergency Distribution Program (P-FRED, or Program). The objectives of the audit were to determine whether: (1) DSS properly administered the Program; (2) DSS properly monitored the contract with Driscoll; and (3) the Program’s intended goals were met. We conduct audits such as this to identify areas where improvements could be made to strengthen the programmatic and fiscal effectiveness of City programs.

The audit found that the Program’s intended goals were broadly met. P-FRED resulted in approximately 2.67 million cases of shelf-stable food and fresh produce being delivered to approximately 400 Emergency Feeding Programs (EFPs), and 90% of survey responses from 198 EFPs were positive. Only 8% of respondents provided negative feedback.

However, the audit found DSS’s controls over the vendor ─ Driscoll Foods (Driscoll) ─ were poor. Due to DSS’s lack of oversight, Driscoll overbilled the City by $9.39 million. $6.44 million was disallowed because it exceeded the allowable budget and $2.95 million were disallowed because Driscoll did not demonstrate the claimed amounts were reasonable and necessary for the Program. While DSS already recouped $2.35 million from Driscoll, a further $7 million should be recouped.

Driscoll also received $5.25 million in supplier rebates which were not passed on to the City. Driscoll also paid $1.6 million to a subcontractor without obtaining approval from DSS as required by the Procurement Policy Board Rules.

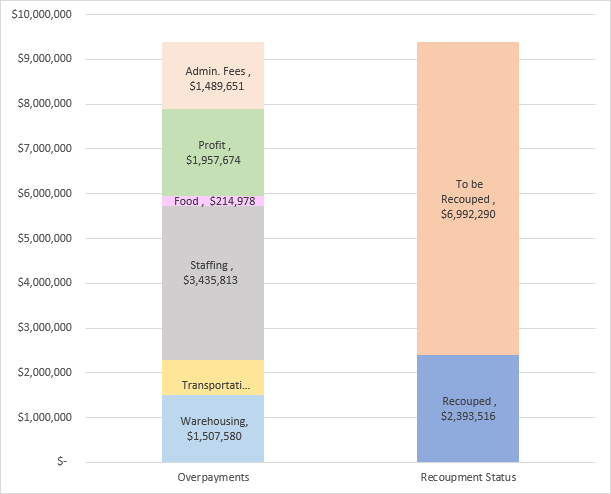

The audit makes eight recommendations including that DSS should recoup $6,992,290 from Driscoll for overpayments identified by the auditors; ensure that vendors comply with contract terms to maintain accurate inventory records when warranted; and require Driscoll to disclose all rebates received for food items supplied to the Program and collect the amount allocated to the Program as an overpayment. DSS has agreed to implement seven recommendations and disagreed with one recommendation.

The results of the audit have been discussed with DSS officials and their comments have been considered in the preparation of this report. DSS’s complete written response is attached to this report.

If you have any questions concerning this report, please email my Audit Bureau at audit@comptroller.nyc.gov.

Sincerely,

Brad Lander

New York City Comptroller

Audit Impact

Summary of Findings

The auditors found that the Pandemic Food Reserve Emergency Distribution Program’s (P-FRED, or Program) intended goals were broadly met. Approximately 2.67 million cases of shelf-stable food and fresh produce were delivered between July 2020 and June 2022 to approximately 400 Emergency Feeding Programs (EFPs), and 90% of survey responses from 198 EFPs were positive. Only 8% of respondents provided negative feedback. This food was an important part of the City’s pandemic response for families who faced food insecurity, such as those who lost employment.

However, the Department of Social Services’ (DSS) fiscal controls over the vendor’s—Metropolitan Foods Inc. d/b/a Driscoll Foods (Driscoll)—responsibilities for providing food services under the P-FRED program were poor. Specifically, the audit found that DSS did not ensure, as it should have, that:

- Claims for payment were the individual budgeted categories, and therefore that money budgeted in the contract for food was actually spent on food;

- Driscoll maintained appropriate inventory records to track the acquisition and distribution of the $61 million spent on food prior to March 1, 2022;

- Program expenses that were claimed and paid for were reasonable and necessary, and supported by documentation that demonstrated the vendor’s claimed expenses were appropriately allocated, actually incurred, and correctly calculated; and that

- All subcontractors were approved prior to issuing payments for related services as required by § 4-13 of the Procurement Policy Board Rules (PPB Rules).

As a result, neither DSS, Driscoll, nor the auditors can be assured that all costs paid for by the Program were reasonable and necessary, or that food acquired through the Program was delivered in its entirety to participating EFPs.

Based on the auditors’ review of Driscoll’s claimed cost and delivery documentation, out of a $90 million contract, Driscoll overbilled DSS for $9.39 million. While DSS disallowed $2.35 million, Driscoll still received approximately $7 million in overpayments as shown in Chart I below:[1]

Chart I: Summary of Overpayments and Recoupment Status

Chart I includes:

- $6.44 million billed that exceeded the allowable budget for the following categories:

- $3.39 million of excess billed for staffing;

- $1.09 million of excess billed for warehousing and storage; and

- $1.96 million of excess for the vendor’s profit.[2]

- $2.95 million in other overpayments:

- $214,978 in overpayments claimed in food costs;

- An additional overpayment of $413,060 for warehousing and storage (above and beyond the $1.09 million disallowed because claimed costs exceeded the allowable budget);

- $780,110 in overpayments claimed for transportation and delivery costs;

- An additional overpayment of $47,412 for staffing (above and beyond the $3.39 million disallowed because claimed costs exceeded the allowable budget);

- $811,194 in incorrectly calculated administrative fees; and

- $678,457 in overpayments related to excessive billing of fees claimed by Driscoll.

While Driscoll was permitted to receive more in profit and in two other expense categories than the budget allowed, Driscoll spent $3.9 million less on food items than it was contracted to provide.

Had DSS and Driscoll maintained better fiscal controls over the Program, the City could have provided more food to those in need.

Intended Benefits

This audit identified overpayments to be collected from Driscoll and improvements to be made in DSS’ oversight and monitoring of vendor contracts. During Fiscal Years 2023 and 2024, five other City agencies did business with Driscoll, spending over $141 million. These agencies may also benefit from closer scrutiny of payments. Most notably, as of April 15, 2024, the Department of Education has three active food contracts with a total contract value of $161 million.

Introduction

Background

The City created P-FRED at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic to address associated food insecurity. The Program was substantially funded by a U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) and placed under DSS’ administration. P-FRED was designed to provide a supply of food to approximately 400 Emergency Feeding Programs (EFPs), food pantries, and community kitchens across the five boroughs, from which it could be distributed to residents in need.

In July 2020, DSS entered an emergency contract with Driscoll to acquire and distribute shelf-stable foods (i.e., no meat, dairy, or ready-to-eat meals) and fresh produce to participating EFPs. The contract ran from July 2020 to June 2022 and provided a maximum budget of $90,975,987 of which DSS paid Driscoll $88,666,342, including $61,904,725 in federal CDBG expenditures.[3] [4]

Between July 2020 and February 2022 Driscoll was reimbursed based on its claimed costs. Driscoll submitted biweekly invoices, with supporting documentation, seeking reimbursement from the City for expenses it claimed to incur under the contract. Under the terms of the contract, Driscoll was entitled to payment in accordance with the approved budget; DSS was also required to comply with the regulations set forth in the Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles and Audit Requirements for Federal Award 2 CFR Part 200 (referred to as the “Super Circular”) governing CDBG funding. Table I, below, lists the five expense categories and associated budgets established in the contract.

Table I: P-FRED Expense Categories and Approved Budget for the Period from July 2020 through February 2022

| Expense Categories | Budget Amount |

| Cost for Sourcing of Food | $65,111,579 |

| Cost for Warehousing and Storage | $3,010,309 |

| Cost for Transportation & Delivery | $3,350,987 |

| Cost for Staffing | $4,194,577 |

| Profit Margin | $5,308,535 |

| Grand Total | $80,975,987 |

For the last few months of the program—from March 2022 to June 2022—the reimbursement structure changed to an all-inclusive fee, which consisted of the cost of food plus a 30% administrative fee (i.e., mark-up).[5] This was limited by a maximum reimbursement to Driscoll of $2.5 million per month.

Objectives

The objectives of the audit were to determine whether DSS properly administered the Program and properly monitored the contract with Driscoll, and whether the Program’s intended goals were met.

Discussion of Audit Results with DSS

The matters covered in this report were discussed with DSS officials during and at the conclusion of this audit. An Exit Conference Summary was sent to DSS and discussed with DSS officials at an exit conference held on December 15, 2023. On April 15, 2024, we submitted a Draft Report to DSS with a request for written comments. We received a written response from DSS on May 3, 2024.

In its response, DSS stated that it agreed with one recommendation, partially agreed with six of the recommendations, and disagreed with one recommendation.

After reviewing the corrective actions outlined in DSS’ response, it appears that DSS actually agreed to implement seven recommendations. The corrective actions include:

- reviewing supporting documentation for the overpayments and rebates Driscoll received and recouping overpayments, as necessary.

- Providing reinforcement training to its staff.

- Standardizing the language regarding cost allocation in its Fiscal Manuals to ensure consistency with all DSS contracts.

- Conferring with the City Law Department to determine whether assessment of liquidated damages is warranted.

DSS disagreed with one recommendation, contending that it already follows all federal, State, and City financial management standards and practices. However, the auditors found that certain Program expenditures did not comply with the Super Circular, §200.403, §200.406, and §200.452.

DSS’ written response has been fully considered and, where relevant, changes and comments have been added to the report.

The full text of DSS’ response is included as an addendum to this report.

Detailed Findings

Each of the auditors’ findings are discussed in detail below.

90% of the EFPs That Responded to the Survey Had Positive Comments about P-FRED

According to Driscoll’s delivery records, approximately 400 EFPs throughout the City received 2.67 million cases of food through the Program from September 2020 through June 2022. The food received by the EFPs was then distributed to the residents of the City.

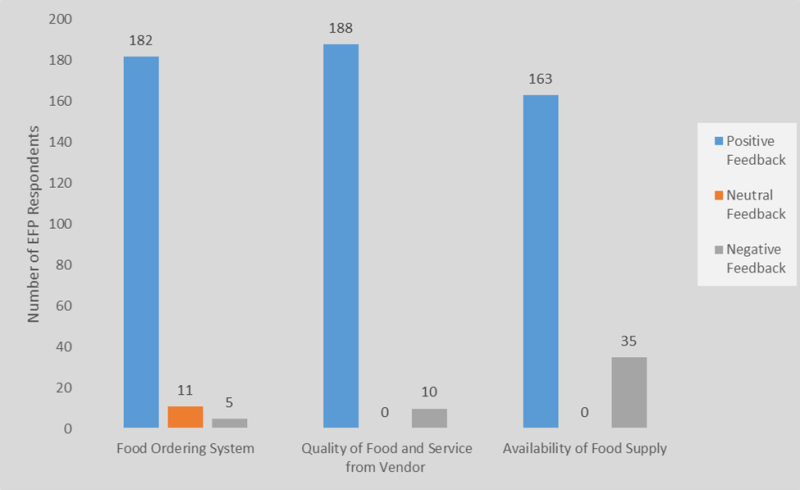

The auditors surveyed participating EFPs based on lists obtained from DSS and Driscoll and received 208 survey responses, with 198 respondents answering the survey questions. Ten respondents stated that they did not participate in the Program and therefore did not complete the survey. The survey asked EFPs to rate satisfaction with three facets of the Program—the food ordering system, food quality, and the availability of supply.

- 90% of all respondents expressed general satisfaction with the quality of the food delivered, the services provided by Driscoll, and the functionality of Driscoll’s ordering portal.

- 8% of all respondents provided negative feedback, concerning the lack of food selection that could be ordered, insufficient supply to satisfy community needs, and communication issues with Driscoll when ordering.

- 2% of all respondents reported neutral feedback, citing certain ordering limitations intrinsic to the Program itself, such as quantity and total dollar value budgeted on food products that could be ordered.

See Chart II below for more detail.

Chart II: Survey Responses on the Program

Driscoll Diverted Amounts Budgeted for Food to Overspend on Profit, Staffing, and Warehousing and Storage

Driscoll spent less on food than allowed in the budget, and simultaneously claimed—and was paid—more than the allowable budget for its own profit, staffing, and warehousing and storage. Driscoll spent approximately $3.9 million less on food items than the contract provided for. Rather than spending this additional amount to purchase food to assist New Yorkers in need, Driscoll overspent on profit for itself (by nearly $2 million), staffing, and warehousing and storage because DSS and Driscoll did not follow the approved budgets set by category in the contract, as required.

According to the contract with Driscoll, Article V: Payment and Invoicing, Section A: Maximum Reimbursable Amount, “[P]ayments shall be made in accordance with the Budget/Contractor’s Price Proposal, attached hereto as Appendix B” [emphasis added]. As of February 28, 2022, Driscoll had exceeded the budget in three expense categories—Profit Margin, Staffing, and Warehousing and Storage—as shown below in Table II. The amounts in excess of the allowable budget should not have been paid.

Table II: Comparison of Budgets with Approved Payments Before Final Adjustment

| Expense Categories | Budget Amount | Approved Payment Before Final Adjustment | Over-Budget Amount |

| Warehousing and Storage | $3,010,309 | $4,104,829 | $1,094,520 |

| Transportation & Delivery | $3,350,987 | $1,171,467 | $0 |

| Staffing | $4,194,577 | $7,582,978 | $3,388,401 |

| Sourcing of Food | $65,111,579 | $61,205,568 | $0 |

| Profit Margin | $5,308,535 | $7,266,209 | $1,957,674 |

| Over-Budget Claims | $6,440,595 |

After the exit conference, DSS attempted to justify Driscoll’s over-budget spending on the basis that Driscoll was not intended to be reimbursed based on a typical line-item budget basis. However, the contract executed between DSS and Driscoll specifies that payments must be consistent with the Budget/Contractor’s Price Proposal, and in this instance, DSS’ lack of oversight resulted in $3.9 million in the unspent food budget being diverted to other expenses, including Driscoll’s bottom line. On DSS’ watch, Driscoll—a for-profit vendor—was allowed to take $1.96 million more in profit than originally agreed upon and spent $4.48 million more on staffing and warehousing/storage, while simultaneously spending less on food.

P-FRED’s primary goal was to supply food to New Yorkers in need. The unspent $3.9 million in the food budget could have helped address these issues. DSS should recoup the over-budgeted amounts paid to Driscoll.

Program Costs Claimed for the Period from July 2020 to February 2022 Were Not Fully Supported or Reasonable and Necessary

During the period from July 2020 to February 2022, the contract between DSS and Driscoll provided for reimbursement of allowable costs actually incurred by Driscoll plus a percentage of allowable costs for profit. §200.403 of the Super Circular regulating the CDBG also required DSS to limit payments to Driscoll for program costs that were both necessary and reasonable. In addition, Article III (B)(3)(vi) required Driscoll to develop and maintain an inventory system to accurately account for the availability of food items purchased through the Program. However, the auditors found that Driscoll did not maintain the food inventory for the $61 million of the food items purchased and did not generally bill DSS based on actual costs incurred for the Program. This occurred in large part because Driscoll lacked appropriate fiscal procedures to ensure that the food items purchased via the Program were accurately accounted for and delivered to the EFPs and only costs actually incurred for the Program were allocated to the Program.

The overpayments that the auditors identified below include claims that exceed allowable amounts as well as associated claims for profit.

Driscoll Did Not Account for All Food Items Purchased for the Food Reserve

Since the core function of the Program was to create a food reserve for needy New Yorkers, the Program’s budget designated 80%, or $65 million, of the $81 million to purchase food. The contract also required Driscoll to develop and maintain an inventory system that provided an accurate account of the availability of shelf-stable foods and fresh produce for the Program. However, Driscoll officials told the auditors that such an inventory system was never developed. As a result, DSS could not ascertain whether the $61 million Driscoll claimed in food costs resulted in actual food deliveries to EFPs. To do so would have required DSS to conduct a detailed examination of the purchasing (i.e., suppliers’ invoices) and delivery records (i.e., delivery receipts signed by EFP officials) in real time.

The auditors’ comparison of invoiced food items that Driscoll submitted for reimbursements and Driscoll’s delivery records from the inception of the Program through February 28, 2022 found that:

- 58% of the food items paid for as claimed Program expenses did not match the item descriptions of the products (such as package size and/or quantity per case) delivered to the EFPs;

- the quantity of food reserve inventory that the auditors determined to be carried over to March 2022 did not match the $1.6 million of inventory Driscoll reported to DSS;

- according to the records reviewed, certain items that the Program paid for were never delivered to the EFPs, including watercress, blueberries, blackberries, raspberries, strawberries, dill, cilantro, mint, parsley, scallions, leeks, mesclun, brussels sprouts, baby arugula, and sparkling cider; and

- almost all the items that the City reimbursed Driscoll for were listed in quantities that were either understated or overstated when compared to records of deliveries to EFPs. For example, the Program paid for 6,050 cases of bananas from December 2021 to February 2022, but the distribution records provided by Driscoll show that it delivered only 22 cases of bananas to two EFPs in May 2021 and January 2022. In another example, the City only purchased 108,548 cases of pineapples but distribution records provided by Driscoll show that it delivered a total of 119,696 cases of pineapples to the EFPs as of February 28, 2022.

Additionally, the auditors identified foods that were not allowed under the Program but were delivered to the EFPs. These items included: breads, eggs, tofu, and certain frozen foods (i.e., New Zealand lamb loin chop, ground turkey, Dover sole, chicken breast, and collards). Although these exceptions were insignificant when compared to the overall quantity of foods delivered to the EFPs, it demonstrates the importance of having an accurate inventory system to account for the costs of all foods claimed to the Program, and calls into question the accuracy of Driscoll’s claimed reimbursement of food costs.

The Value of Food Delivered to the EFPs was Close to the Amount Paid by the City

Based on a review of the average food costs claimed, the auditors estimate that the food items delivered to the EFPs had a value within 2% of what the City paid. However, without a separate accounting of the P-FRED inventory and independent verification of deliveries to EFPs, neither DSS, Driscoll, nor the auditors can be assured that all food paid for by the Program—$61 million for the period from July 1, 2020 to February 28, 2022—was delivered to EFPs participating in the Program. The auditors are also unable to verify that all costs claimed against the P-FRED Program resulted in food for the Program.

Driscoll Did Not Credit Any of the $5.25 Million in Suppliers’ Rebates to the City

Super Circular, §200.406, requires that “applicable credits refer to those receipts or reduction-of-expenditure-type transactions that offset or reduce expense items allocable to Federal award as direct or indirect (F&A) costs…To the extent that such credits accruing to or received by the non-Federal entity related to allowable cost, they must be credited to the Federal award either as a cost reduction or cash refund, as appropriate.” However, Driscoll did not credit the City for any cash discounts, rebates and/or credits associated with the foods acquired for the Program.

Based on a review of all invoices that Driscoll submitted to support its claims of the $61 million in food costs, the auditors found that Driscoll did not credit the City any of the $5.25 million in rebates it received (purchase discounts). Auditors identified 261 instances where Driscoll received rebates from its suppliers but none of the $5.25 million in rebates that Driscoll received were credited to the City’s billings. The auditors were unable to determine whether additional rebates were received by Driscoll and how much of the rebates should have been allocated and passed-on to the P-FRED Program.[6]

Driscoll Claimed $214,978 in Inappropriate Food Costs

The auditors found that $214,978 was inappropriately claimed and paid because Driscoll’s supporting documentation did not provide sufficient evidence to support the claimed amounts. According to the contract, “[A]ll costs shall be supported by […] invoices, contracts, or vouchers or other official documentation evidencing in proper detail the nature and propriety of the charges.”[7] The summary of inappropriate claims is listed as follows:

- $188,101 were duplicate billings. Driscoll claimed five food items in five invoices more than once. These duplicate claimed items were submitted to the City within the same or subsequent billing cycles.

- A net overcharge of $17,252 for food costs and related charges claimed based on a comparison of the total amount Driscoll charged to the suppliers’ invoices.

- $8,127 was paid for 12 non-food items that were listed on the invoices submitted for payments, which were not allowed under the Program.

- $1,498 of cash discounts DSS received from its suppliers that DSS did not deduct from the claimed costs.

Driscoll Overbilled $1.5 Million for Warehousing and Storage Costs

According to the contract, Driscoll was required to bill DSS based on the actual costs it incurred to provide warehousing and storage. However, Driscoll billed DSS $55,000 every two weeks for space that it owned and for which it did not pay rent. DSS reimbursed Driscoll at a flat rate derived from a flat $25 per pallet and an assumed storage of 2,200 pallets for every two-week period, regardless of how many pallets P-FRED actually stored at any given time.

Driscoll billed the City $419,573 for other warehouse-related costs (i.e., facility and equipment maintenance, utilities, and property insurance) that were unallowable according to §200.452 of the Super Circular, which states that “costs incurred for utilities, insurance, maintenance, janitorial services, repair or upkeep of buildings and equipment are allowable to the extent not paid through rental or other agreements.” Driscoll did not provide documentation to substantiate that it incurred such warehouse-related costs above and beyond what it charged for rent, and was therefore not entitled to be reimbursed for them.

Driscoll also charged an additional $1.4 million over a two-month period for a warehouse it rented from a third-party for $283,630. Driscoll was entitled to claim the $283,630 plus 10% of this for profit, totaling $311,993. The rest was not reimbursable under the terms of the contract. Driscoll overbilled the City by $1,507,580 ($1,088,007 + $419,573) for unallowable warehouse and warehouse-related costs.

Driscoll Failed to Properly Allocate Transportation and Delivery Costs and Overbilled the City by $780,110

A key principle of cost reimbursement contracts is that only actual costs incurred by the program may be billed to the program. In cases such as this, when Driscoll was providing trucks and making deliveries to other private customers and other City agencies and programs, Driscoll was required to segregate and claim only P-FRED-related costs. This is usually done through an approved allocation methodology. However, neither Driscoll nor DSS could provide or document a methodology to show how Driscoll allocated transportation and delivery costs to P-FRED.

The auditors conducted tests to determine whether costs paid by P-FRED were appropriately allocated to ensure only costs incurred by the Program were paid for by the Program. One set of tests was based on trend analysis which resulted in the identification of $96,496 in billings for truck costs, when no deliveries occurred, and $621,148 in estimated overbillings based on Driscoll’s billing pattern of truck costs and delivery pattern to EFPs. Another test was based on a sample review of truck manifests, leases, insurance, and fleet costs incurred for two biweekly billings, which resulted in auditors determining that Driscoll overbilled the City by $62,466.

Both sets of tests raise doubt that P-FRED only paid for Program-related transportation and delivery costs. In total, the trend analysis and records reviewed for the sampled periods disclose $780,110 in costs that did not belong to P-FRED.

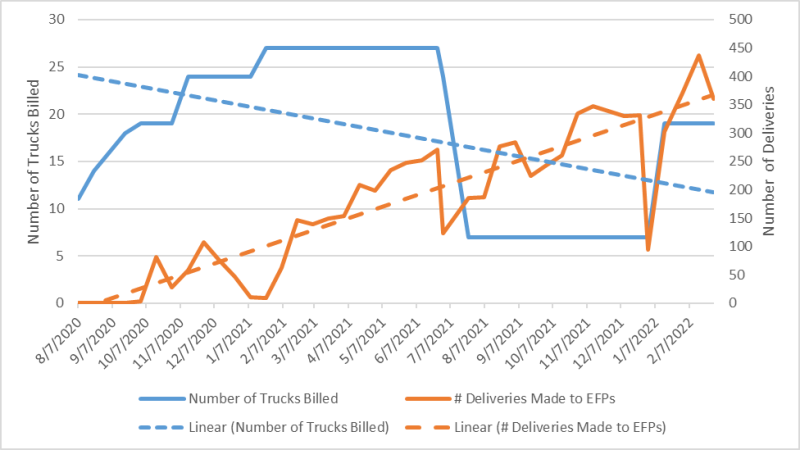

Trend Analysis Results Do Not Support Driscoll’s Claimed Costs

The auditors conducted an analysis of Driscoll’s Transportation and Delivery cost billing patterns and compared them to the delivery data (i.e., number of deliveries and the cases of food being delivered to the EFPs) for the duration of the Program and concluded that Driscoll did not bill the City for actual costs incurred for the Program.

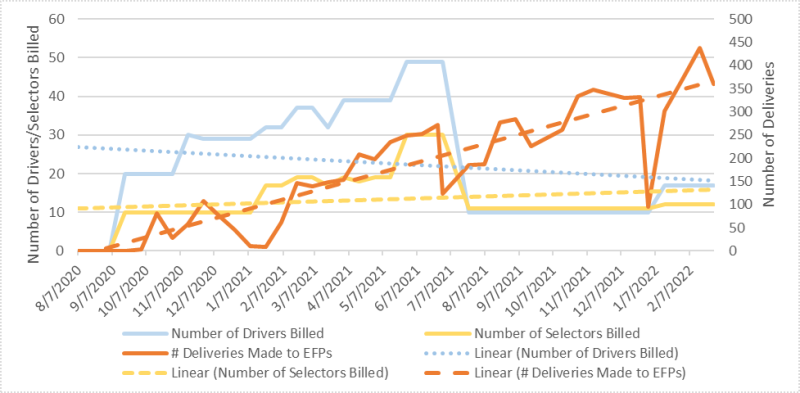

If Driscoll had only billed for transportation and delivery costs incurred for P-FRED, the number of trucks claimed should have increased when the quantity of food or number of deliveries for P-FRED increased. There should be a positive correlation. However, when charted, the trendlines (see Charts III and IV) indicate that Driscoll billed the City for more trucks when there were fewer Program deliveries, and conversely for fewer trucks when deliveries to EFPs increased over time (a negative correlation). These trends call Driscoll’s claimed costs into question.

The number of P-FRED delivery stops compared to the number of trucks Driscoll claimed for reimbursement are shown below in Chart III. For example, over the period from July 2021 to December 2021, Driscoll billed the City for only seven trucks every two weeks, when the data shows it was making as many as 347 P-FRED delivery stops. Conversely, between July 2020 and June 2021, Driscoll billed the City for up to 27 trucks every two weeks when the number of P-FRED delivery stops to EFPs fell below 260. This suggests the allocation of transportation and delivery costs was inaccurate.

As also evident in the data, Driscoll billed the City $96,496 for leasing and other truck-related expenses during the period of July 25, 2020 to September 18, 2020 when the data shows no P-FRED deliveries to EFPs were made (see Chart III below).

Chart III: Number of Trucks Billed vs. Number of Deliveries*

* The auditors assumed Driscoll made only one stop to deliver all foods to each EFP within the same day.

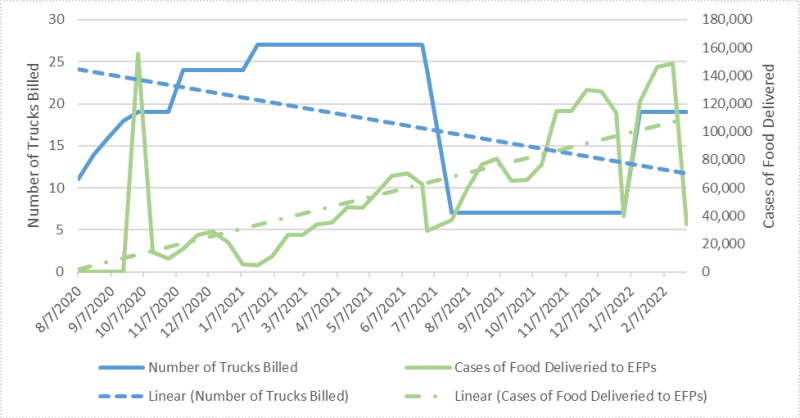

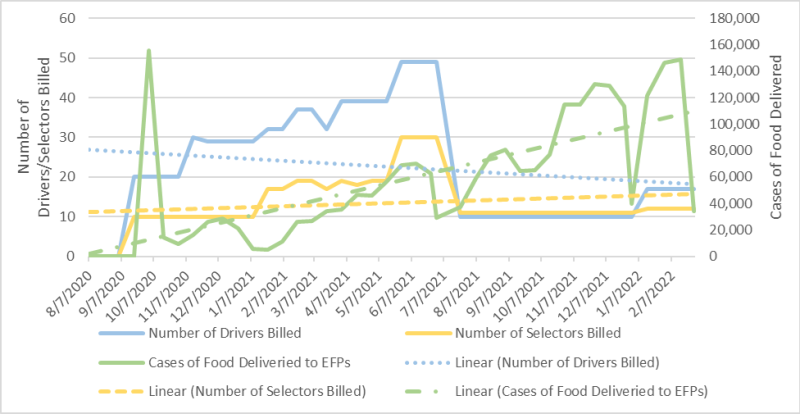

Chart IV shows the number of cases of food delivered by Driscoll compared to the number of trucks Driscoll claimed for reimbursement. Driscoll billed the City for up to 27 trucks every two weeks for the period from July 2020 to June 2021 while the number of cases of food being delivered generally did not exceed 70,000 cases. However, for the period from July 2021 to December 2021, Driscoll billed the City for seven trucks every two weeks and delivered as many as 130,158 cases of food within a two-week period.

Chart IV: Number of Trucks Billed vs. Cases of Food Delivered

Based on the delivery data, Driscoll was able to deliver as many as 130,158 cases of foods using only seven trucks in a two-week period. Using this as a baseline, the auditors allowed Driscoll’s claims for seven trucks throughout the period and disallowed the cost associated with the remaining trucks; this results in an estimated overpayment of $621,148 on Transportation and Delivery Costs for most of the period from September 19, 2020 to February 28, 2022.

For the two biweekly periods from October 17, 2020 to October 20, 2020 and January 23, 2021 to February 5, 2021, the auditors conducted sample-based testing, which resulted in the identification of a further $62,466 in overpayments. See below for details.

Sample-Based Testing Shows Driscoll Overbilled P-FRED $62,466 in Transportation and Delivery Costs

The auditors conducted a sample-based analysis of transportation and delivery costs over two biweekly periods from October 17, 2020 to October 20, 2020 and January 23, 2021 to February 5, 2021. This review involved comparing Driscoll’s billings with food delivery records. The auditors found that Driscoll overbilled the City by $62,466 for just these two biweekly periods, which represents 82% of the sampled periods’ claims.

Specifically, for the period from October 17, 2020 to October 30, 2020, Driscoll claimed for the cost of 19 leased trucks and associated automobile insurance and equipment totaling $30,844, on the basis that these were needed for deliveries for P-FRED. However, the truck route manifests, which listed both P-FRED and non-P-FRED deliveries, showed that Driscoll only used a maximum of 14 trucks per week for P-FRED deliveries.

Similarly, for the period from January 23, 2021 to February 5, 2021, the truck route manifests showed Driscoll used a maximum of 20 trucks in a week for all P-FRED deliveries while billing the Program for 27, totaling $43,954.

By comparing the number of delivery stops made for P-FRED shown in the manifests to the total number of stops made, the auditors determined that only 18% of the total truck stops were P-FRED related. The auditors then prorated the P-FRED portion to Driscoll’s total charged amounts, resulting in $62,466 overpayments for trucks and truck-related expenses for these two biweekly periods alone.

Driscoll Overbilled $3,435,813 for Staffing

Driscoll billed for the following staff functions:

- Purchasing staff;

- Warehouse staff;

- Drivers;

- Selectors; and

- Other administrative staff.

However, Driscoll did not provide a methodology that supports the allocation of staffing costs to P-FRED. As with transportation and delivery costs claimed, the auditors conducted a trend analysis and sample-based testing to assess the accuracy of Driscoll’s claimed costs. The auditors determined that Driscoll overbilled DSS by $3,435,813, as shown below.

Data Shows Unsupported Allocation of Reimbursed Costs

A review of delivery data shows that the amounts claimed by Driscoll were not supported as reasonable costs for drivers and selectors. As shown in Charts V and VI below, the trendlines show Driscoll billed for more drivers when the quantities of food delivered were relatively low, during the first year of the Program.

For instance, from September 5, 2020 to June 30, 2021, Driscoll billed the City for between 20 and 49 drivers/driver supervisors, when deliveries ranged from zero to 271 stops. The most cases Driscoll delivered was 70,081 from May 29, 2021 to June 11, 2021, when Driscoll billed $192,103 for 45 drivers and four driver supervisors. However, for the period from July 1, 2021 to February 28, 2022, Driscoll billed for 10 to 15 drivers/driver supervisors, when deliveries ranged from 95 to 347 stops. Driscoll delivered the most cases, 148,740 in total, during the period from February 1, 2022 to February 15, 2022, when Driscoll billed $69,253 for 15 drivers and no driver supervisor.

It is hard to see how Driscoll can claim these costs were necessary and reasonable when fewer drivers/driver supervisors were billed when more deliveries occurred.

Chart V: Number of Drivers/Selectors Billed vs. Number of Deliveries*

* The auditors assumed Driscoll made only one stop to deliver all foods to each EFP within the same day.

The data shows that Driscoll billed the City for 10 to 30 selectors every two weeks for the duration of the Program. This equates to an average of between 295 and 15,590 cases of food per selector, a range too large to be accurate. In addition, the auditors found that Driscoll billed for fewer selectors when the number of cases of food handled increased, and conversely, billed for more selectors when the number of food cases handled decreased.

For example, for the period from May 15, 2021 to July 9, 2021, Driscoll billed the City for 30 selectors who handled a total of 230,535 cases of food. This equates to an average of 1,921 cases of food per selector every two weeks. In contrast, Driscoll billed the City for 11 selectors when it was handling 1,102,804 cases of food for the Program, during the period from July 10, 2021 to December 31, 2021. This equates to an average of 7,712 cases of food per selector every two weeks. This is four times more than the average number of cases handled by the selectors earlier, during the period from May 15, 2021 to July 9, 2021.

The billing pattern shows a negative correlation between the number of selectors being paid to the number of cases of food that each selector handled, again calling into question the accuracy of Driscoll’s claimed costs. In addition, since Driscoll’s data shows each selector may handle a maximum of 15,590 cases of food within a two-week period, the auditors estimate Driscoll overcharged the City $967,972 for the period from September 19, 2020 to February 28, 2022.

Based on the transportation findings above, which found that Driscoll only needed seven trucks for P-FRED deliveries, the auditors allowed salaries for a maximum of seven drivers and estimate that Driscoll overcharged DSS $2,037,777 in driver costs between September 19, 2020 and February 28, 2022. This is on top of the disallowed labor costs which appear below in Chart VI.

Chart VI: Number of Drivers/Selectors Billed vs. Cases of Food Delivered

The auditors used the same disallowance percentages for the transportation and delivery costs to disallow the cost of associated drivers’ salaries and fringe benefits (which were based on the actual number of trucks used for P-FRED) during the two biweekly periods mentioned above. This results in overbillings by Driscoll of $114,741 for drivers’ salaries and fringe benefits.

Driscoll Was Paid for Employing Drivers and Selectors When No Deliveries Were Made

During the period from September 5 to September 18, 2020, Driscoll claimed labor costs for 17 truck drivers, two driver supervisors, one driver manager, fringe benefit costs associated with the drivers, and 10 selectors at a time when Driscoll made no deliveries to the EFPs. These unnecessary labor costs amounted to $88,071.[8]

Driscoll Was Paid for Salespeople Unrelated to P-FRED

Other questionable labor costs that Driscoll billed include $227,252 in salary and fringe benefits for three salespersons; Driscoll was unable to justify how services provided by sales staff were directly related to the Program. Therefore, these costs should be disallowed.

After the exit conference, DSS provided the job description and responsibilities of a salesperson. The description states, among other things, that “the Salesperson will be responsible for growing sales and customer base in the assigned territory” and will “recognize items which customers have stopped buying and try to get them back.” The responsibilities provided in the job description do not align or relate to P-FRED’s programmatic needs.

Driscoll Claimed at Least $456,684 More in Profit Than It was Entitled To

During the period of July 2020 to February 2022, Driscoll was entitled to a profit margin based on the costs it actually incurred. This meant that as costs went up, so did Driscoll’s profit. It also means that if Driscoll claimed more than actual costs, the profit it was paid must be re-adjusted. Due to inappropriate billings in the categories outlined above, Driscoll should not have received at least $456,684 in profit on the following items:

- $13,594 in costs claimed for warehousing,

- $78,011 in costs claimed for transportation and delivery,

- $343,581 in costs claimed for staff, and

- $21,498 in costs claimed for sourcing food.

These unnecessary payments could have been avoided if DSS had appropriately reviewed Driscoll’s claims for payment prior to approving payment. As noted above, this overpayment is included in the amount of disallowance taken for exceeding the allowable budget for profit.

DSS Overpaid Driscoll $1.5 Million Due to Excessive Billing of Administrative Fees During the Last Four Months of the Program

DSS overpaid Driscoll by $1.5 million for the period of March through June of 2022 due to Driscoll’s excessive application of administrative fees for inventory it had already been paid a profit margin on, and due to Driscoll claiming over 42% as an administrative fee for a period during which it was only entitled to 30%.

Driscoll Excessively Billed $678,457 in Additional Fees for Items It Previously Had on Hand

By the end of February 2022, Driscoll had reported that it retained a supply of 41 food items that had been paid for on a cost-plus-10% profit basis. These were carried over to March 2022, when the reimbursement methodology changed. These carryover food items needed to be delivered to the EFPs before the Program ended in June 2022. When Driscoll submitted the invoices to DSS for the last four months of service, it charged additional administrative fees for the 41 items it previously had on hand. Since these items were purchased prior to March of 2022, Driscoll had already charged DSS 10% profit on each of these items and was not entitled to any additional reimbursement. Auditors determined that the additional administrative fees of $678,457 were overbillings which should be recouped from Driscoll.

Driscoll Misrepresented Administrative Fees Associated with Its Food Costs and Overcharged the City by $811,194

On April 28, 2022, DSS changed the contract’s payment terms for the period from March 1, 2022 through June 30, 2022. Instead of reimbursing Driscoll for the cost of food and other direct costs, DSS arranged to pay Driscoll an all-inclusive price for the foods delivered to EFPs. This consisted of the actual cost of food plus a 30% administrative fee.

Contrary to what was agreed upon, the auditors found that Driscoll inflated its administrative fees by charging 42.8% for all food items listed on the price list submitted to DSS. Driscoll effectively overcharged DSS by 12.8% for every item billed between March 1, 2022 and June 30, 2022. This was done by applying the 30% fee to the sales price, which consisted of the cost of the food plus a mark-up. Driscoll should have applied the 30% administrative fee to cost of food only. As a result of this, Driscoll overbilled the City by $811,194.

Driscoll Did Not Obtain Approval from DSS to Use Subcontractor

According to § 4-13 Subcontracts of the PPB Rules and Article 3 of the Contract in Appendix A, Driscoll was required to obtain pre-approval from DSS for subcontractors providing services for more than $20,000. It was also required to demonstrate that it exercised due diligence in vetting the subcontractor and that hiring the subcontractor was in the best interests of the City.

The auditors found that Driscoll paid a subcontractor $1.6 million during the contract period to provide the selectors’ service to the Program without seeking approval from DSS. Without the proper approval and subcontractor’s information, DSS cannot be assured that Driscoll properly solicited the subcontractor or that the subcontracting was in the best interests of the City.

The contract terms and conditions allow DSS to claim liquidated damages of $100 per day for each day that Driscoll failed to list its subcontractors in the City’s Payee Information Portal and/or failed to report subcontractor payments within 30 days after each payment was made. DSS should explore whether it can claim liquidated damages. If the liquidated damages were claimable, it would amount to $73,000 ($100 x 730 days) in total.

Recommendations

To address the abovementioned findings, the auditors propose that DSS should:

- Recoup $6,992,290 from Driscoll for overpayments identified by the auditors (beyond the $2.35 million in costs that DSS already disallowed).

DSS Response: DSS partially agreed with this recommendation. DSS will complete a review of all supporting documents and recoup, as appropriate.

Auditor Comment: Although DSS partially agreed with this recommendation, DSS’ corrective action plan states that this recommendation will be implemented.

- Ensure vendors comply with contract terms to maintain accurate inventory records when warranted.

DSS Response: DSS agreed with this recommendation.

- Require Driscoll to disclose all rebates received for food items supplied to the P-FRED Program and collect the amount allocated to the Program as an overpayment.

DSS Response: DSS partially agreed with this recommendation. DSS stated that it will complete a review of all supporting documents and recoup, as appropriate.

Auditor Comment: Although DSS partially agreed with this recommendation, DSS’ corrective action plan states that this recommendation will be implemented.

- Ensure that only costs incurred by a program are charged to the program by:

- Establishing written cost allocation guidance for vendors reimbursed based on incurred costs;

- Requiring vendors to submit cost allocation methodologies that are consistent with such guidance, for each cost subject to allocation;

- Training staff to properly review invoices and to test for appropriate allocation of costs; and

- Conducting sample-based reviews of allocated costs to ensure claims for allocated costs are reasonable and program related.

DSS Response: DSS partially agreed with this recommendation. DSS stated that it already has procedures to ensure that only the costs incurred are charged to the program. Additionally, DSS stated that it is in the process of standardizing language regarding cost allocation in both the HRA and DHS Fiscal Manuals to ensure consistency with all agency contracts and will continue to provide reinforcement training during the monthly Contract Managers’ Meetings.

Auditor Comment: Despite having procedures in place as DSS claimed, the procedures performed did not flag Driscoll’s overbilling of the program costs. Additionally, although DSS partially agreed with this recommendation, DSS’ corrective action plan states that this recommendation will be implemented.

- Strengthen its procedures for reviewing claims prior to making payment by:

- Ensuring staff who are responsible for contract oversight are familiar with City fiscal policy and contractual payment terms and conditions;

- Comparing claimed costs with approved budgets and holding vendors to approved budgeted amounts;

- Training invoice review staff to spot expenses claimed on behalf of subcontractors to ensure the use of such subcontractors have been approved; and

- Conducting interim and/or real time reviews to determine whether invoices submitted to DSS are adequately supported and comply with contractual terms.

DSS Response: DSS partially agreed with this recommendation. DSS stated that it already has robust procedures for reviewing invoices for payment prior to making payments and will continue to provide reinforcement training during the monthly Contract Managers’ Meeting.

Auditor Comment: Despite having robust procedures as DSS claimed, the auditors still found evidence showing that DSS overpaid Driscoll for the program costs. Additionally, although DSS partially agreed with this recommendation, DSS’ corrective action plan states that this recommendation will be implemented.

- Ensure that programs receiving federal grants comply with the federal guidelines for grant expenditures.

DSS Response: DSS disagreed with this recommendation. DSS stated that it already follows Federal, State, and City financial standards and practices.

Auditor Comment: The auditors’ evaluation of the Program revealed that certain expenditures were not in compliance with the Super Circular, §200.403, §200.406, and §200.452. DSS should ensure that programs comply with all federal guidelines, rules, and regulations.

- Assess and collect liquidated damages from Driscoll for not obtaining approval of its subcontractor from DSS as required.

DSS Response: DSS partially agreed with this recommendation. DSS stated that it will confer with the City Law Department to determine whether assessment of liquidated damages is warranted.

Auditor Comment: Although DSS partially agreed with this recommendation, DSS’ corrective action plan states that this recommendation will be implemented.

- Oversee all contract requirements and require vendors to submit full disclosure and request approval for use of their subcontractors.

DSS Response: DSS partially agreed with this recommendation. DSS stated that it will continue to provide reinforcement training during the monthly Contract Managers’ Meeting.

Auditor Comment: Although DSS partially agreed with this recommendation, DSS’ corrective action plan states that this recommendation will be implemented.

Recommendations Follow-up

Follow-up will be conducted periodically to determine the implementation status of each recommendation contained in this report. Agency reported status updates are included in the Audit Recommendations Tracker available here: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/services/for-the-public/audit/audit-recommendations-tracker/

Scope and Methodology

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (GAGAS). GAGAS requires that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions within the context of our audit objective(s). This audit was conducted in accordance with the audit responsibilities of the City Comptroller as set forth in Chapter 5, §93, of the New York City Charter.

The scope of this audit was July 1, 2020 through June 30, 2022.

To achieve the audit objectives, the auditors interviewed DSS officials to obtain an understanding of DSS’s fiscal review processes, including the inspection of the food storage sites, reviewing and approving invoices submitted by Driscoll, and overseeing the Program’s performance. To determine Driscoll’s roles and responsibilities, the auditors reviewed the contract, including the CDBG rider, Super Circular, and two subsequent amendments between DSS and Driscoll, and interviewed Driscoll’s staff to obtain an understanding of Driscoll’s operations, including ordering and delivering process, maintaining inventory records, and billing process.

To determine whether the required inspections on the food storage sites were conducted, the auditors obtained and reviewed the inspection reports that the City provided.[9]

To determine whether the EFPs were located within the City, the auditors obtained a list of EFPs from DSS and reviewed their locations. The auditors also sent a survey to 410 of 491 EFPs to ensure that these EFPs participated in the Program, received food supplies from Driscoll, maintained records for the foods received and distributed, and were satisfied with Driscoll’s performance.[10] The auditors received 208 EFP responses and then reviewed and summarized the EFP responses.

For the period from July 1, 2020 through February 28, 2022, the auditors determined whether Driscoll distributed all the foods that the City paid for to the EFPs by summarizing all the food acquired through Driscoll and comparing to the food delivered to the EFPs. To estimate the value of the food items delivered to the EFPs, the auditors calculated the average price of food items based on food categories. For instance, the auditors grouped all the various potatoes into one food category and determined the average food cost per case regardless of the type of potato or the quantity per case. The auditors then used the average price to multiply the quantity delivered to the EFPs to estimate the value of food items. Based on the estimated value of each food category, the auditors calculated the total estimated value of the food items delivered and compared that amount with the total food costs that DSS reimbursed Driscoll. The auditors also determined whether the types of food that Driscoll acquired and distributed complied with the contract requirements.

To determine whether Driscoll properly billed the City, the auditors judgmentally selected two milestone payments for the period ending October 30, 2020 and February 5, 2021 and reviewed all the supporting documentation. Analytical procedures on Driscoll’s billing pattern were also performed to determine whether Driscoll’s billings were reasonable and necessary. Based on the result of the analytical procedures, the auditors estimated the overcharged program costs when necessary.

For the last four billings that covered the months from March 2022 to June 2022, the auditors reviewed the monthly billings and the supporting documentation to determine whether Driscoll accurately billed the City.

Although the results of the sampling tests were not projectable to their respective populations, these results, together with the results of the other audit procedures and tests, provided a reasonable basis for the auditors to determine whether DSS properly administered the Program and that the Program’s intended goal was met.

Addendum

See attachment.

Endnotes

[1] The auditors deducted $2.35 million DSS final disallowance/adjustment from the $9.39 million overpayments that the auditors determined during the audit.

[2] $456,684 paid to Driscoll for profit would have been disallowed on other grounds had they not been disallowed based on their exceeding the allowable budget.

[3] The total payments to Driscoll went below the total budgeted amount due to the final $2.35 million disallowance/adjustment made by DSS.

[4] P-FRED received a total of $61,907,100 in CDBG during Fiscal Years 2021 and 2022.

[5] Mark-up is an amount added to the cost of an item to arrive at a selling price and may be expressed as a percentage of cost or in dollars.

[6] The auditors reviewed Driscoll’s payment vouchers for payments to its suppliers that included deductions for rebates. However, since these payments and rebates may be for purchases other than for the City’s P-FRED program, the auditors could not determine the dollar amount in rebates that should have been applied to the City. The value of the rebates should have been allocated across all of the entities paying for the food items with rebates.

[7] Article 9 of the CDBG Rider that was attached to the contract.

[8] These disallowed labor costs included salaries/wages and 27.65% of fringe benefits (excluding previously disallowed fringe benefits for selectors).

[9] A separate email was submitted to DSS regarding their non-compliance with the inspection requirement of the contract.

[10] Email contact information for 81 EFPs was not provided.