Executive Summary

Since the 1970s – as New York City’s housing challenges have shifted from abandonment and disinvestment to gentrification and skyrocketing rents – the NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) has financed the development and preservation of hundreds of thousands of affordable homes, provided financial support and technical assistance to co-operators, tenants, and building owners, and held landlords accountable to meet standards of habitability.

HPD continues to have an urgent role to play in addressing the city’s housing crisis, with post-pandemic rents at all-time highs, housing starts at extremely low levels, homeownership far beyond the reach of most families, more tenants than ever facing extremely high-rent burdens, and historically high homelessness. Financing the production and preservation of affordable housing remains the City’s most powerful tool in combatting the city’s housing crisis – and HPD is involved in the vast majority of affordable housing projects across the five boroughs.

Between 2013 and 2019, the City of New York increased the workforce at HPD by over 500 full time employees and significantly scaled up housing production – quadrupling the agency’s annual capital expenditures from $414 million in 2013 to $1.68 billion in 2019.[1] However, the staffing crisis that followed the outbreak of COVID-19 hit HPD (and many other City agencies) hard. Between April 2020 and October 2022, HPD lost nearly a third of its full-time employees, including many of its more experienced staff and was not able to rehire to fill many of those positions. In Fiscal Year 2022, the agency spent only 60% of its planned capital commitments.

Over the past year and half, HPD has turned a corner on staffing and was finally able to hire more staff than left the agency. Due to external advocacy, agency leadership and OMB’s removal of certain barriers, HPD has hired an additional 863 full time employees in the past six fiscal quarters while losing only 651 people. In FY 23, the agency increased their rate of capital liquidation to 90% of planned commitments.

Despite the agency’s herculean effort to staff back up in core program areas, the agency’s loss of institutional memory and longstanding technological deficiencies will make it challenging to clear the backlog of affordable housing projects that accumulated over the past two years. In addition to projects delays, the current economy, including broader market trends that have increased interest rates, construction prices, and building operating costs, have created an unsustainable strain on community-based organizations across the five boroughs. To correct for the period of low production of affordable housing, and to help alleviate the financial stress of the City’s community development sector, HPD would need to increase housing starts and completions above recent levels in the upcoming fiscal year. To meet Mayor Adams’ “moonshot” goal for housing production, it would need to do even more.

To be sure, there are additional factors, other than unit count, that should be considered when agency leadership prioritizes projects, including the depth of affordability and number of units that will help individuals and families exit the shelter system, the immediacy of the repairs needed, the impact on the quality of life of the residents, how long the project has been in the pipeline, the loan readiness of the project, and the ability for the borrower to find other sources of funds. These other factors are much harder to track, particularly externally, but increasing the efficiency of the agency and training up existing staff, may help HPD be able to properly weigh all of these factors when making decisions about project prioritization each fiscal year.

To help chart a path forward, the Comptroller’s Office analyzed available staffing reports, budget data, and conducted nearly 40 interviews with former staff, developers, and not-for-profit organizations that work with HPD. The findings reveal that HPD must not only rebuild its staff capacity but address longstanding issues to make the agency more efficient than ever.

The City must dedicate resources (identified in the report) to grow the capacity of new HPD staff and make overdue technological upgrades. HPD leadership should also use this moment to continue its ongoing work of re-evaluating and streamlining certain development processes, building upon recent successful efforts and initiatives. With these recommendations, HPD can build on its historic mission to meet the housing affordability challenges facing New Yorkers.

Key Findings

HPD Production Has Rebounded from Pandemic Declines, but Production Increases are Needed to Hit Goals

- HPD’s affordable housing production hit a low point in Fiscal Year (FY) 2022, dropping significantly below the peak numbers from FY 18 – FY 21, in which the City averaged 14,850 housing starts and 26,410 completions each fiscal year. Production rebounded in FY 23, and the Comptroller applauds the improvements, however it remains slightly below the average rates achieved between FY 18 – 21. To make up for the decrease in production over the past two years and to hit the Mayor’s “moonshot” goal of developing 500,000 units of housing in the next 10 years, HPD would need to increase its production from last year by 42% in the upcoming fiscal year.

- The number of affordable housing starts declined significantly during FY 22, dropping to just 14,793 units – nearly 12,000 units less than the average number of affordable housing starts over the four previous fiscal years (26,411).

- In FY 22, there were only 7,934 units financed through the preservation loan programs, representing just 30% of the average number of units financed in the three years prior to the pandemic.

- Due to the significant loss of staff relative to the high volume of potential projects, the pipeline of pending projects in the predevelopment stages within the preservation loan programs has accumulated.

The Time to Finish Projects and Lease-up Affordable Units Has Increased

- Projects that receive HPD capital through the Special Needs Housing, Preservation and New Construction loan programs are also taking longer to complete – increasing the backlog of projects with outstanding construction loans. The average timeline for completion through loan conversion to permanent financing across those three loan programs was 3.4 years in FY 17 – 19 and 4.3 years in FY 21 – 23, a 25% increase.

- In FY 23, the median time to approve an applicant for lottery unit increased to 192 days, up from 88 days in FY21– which means affordable units are sitting vacant for an average of over six months before a tenant is even approved to move in. The median time to lease a homeless set-aside unit in a new construction project increased from 106 to 243 days, or about 8 months.

- In FY 23, only 21% of lottery units had applicants approved within three months and only 41% of units had applicants approved within six months. Those numbers indicate a huge increase in delays over the past two fiscal years. In FY 21, the highest performing year since the City began tracking the data, 56% of lottery units had applicants approved within three months and 73% of lottery units had applicants approved within six months.

HPD Has Mobilized Impressively to Reverse Pandemic Staffing Losses, but Still Faces Significant Staffing Retention Challenges

- From April 2020 until October 2022, HPD lost almost one-third of the full-time staff at the agency; out of 2,430 full-time employees, 911 departed and the agency was only able to hire 625, resulting in a net loss of 286 people.[2]

- HPD has lost significant institutional memory over the past years, with a particular loss of experienced staff in 2022, in which 225 out of 1,512 staff members with over 5 years of experience left the agency – an unprecedented exit when compared with the preceding ten years.[3]

- The loss of experienced staff within the Office of Development is acute in HPD’s preservation programs, which experienced a 75% staff turnover since 2020 and the backlog of projects is the largest in this program area.

- Staff attrition during the “Great Resignation” paired with City-imposed hiring freezes and the resulting increased workloads (without increased levels of pay) at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, caused many high-performing workers to leave the agency – the City-imposed return to the office five-days-a-week in September 2021 was cited as a decision-point by many former staff. Though the agency has staffed back up, the City must support HPD’s stability by allowing the agency to hire new staff, by providing the agency with opportunities to promote existing agency staff, and by providing all City workers with permanent flexible work location policies. Additionally, HPD should also continue to provide expert training, including training on the history of community development sector within New York City, to ensure new staff can increase their capacity and be retained over time.

Development Process Pain Points that Existed Before the Staffing Shortage Persist

- Many bottlenecks in the development process existed before HPD lost a significant number of staff. Historically, experienced project managers in the Office of Development at HPD played a critical role in alleviating slowdowns. As many of those staff left the agency, existing pain points were exacerbated, especially those in HPD’s Building and Development Services (BLDS), Legal, and Marketing divisions.

- The NYC Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has become increasingly involved in HPD’s underwriting process over time, providing rounds of comments that add significant time to the development process.

HPD Technology Requires Significant Upgrades

- HPD has digitized some of its internal processes that were done exclusively via paper forms prior to the COVID-19 pandemic; however, antiquated, or deficient systems still exist, such as the manner by which staff request an attorney and Housing Connect 2.0 – the system that manages the marketing of all new affordable housing in the City. Existing software doesn’t allow for evaluation of inefficiencies and project delays across the agency as it is primarily built for external reporting functions.

HPD’s Challenges Create Downstream Complications for Non-Profits and Lower-Capacity Borrowers

- The capacity of borrowers that receive loans from HPD varies significantly. New Construction loan programs tend to have higher capacity borrowers, because of the significant financial requirements of that type of development. However, the borrowers within the preservation loan programs are often small landlords, HDFC co-op boards, or small nonprofits that do not have a dedicated real estate development team. While programs exist to support these borrowers, they are not sufficient to meet the need or backlog that has developed.

- Given the level of HPD’s involvement in the development and preservation of affordable housing, delays at the agency accumulate and can cause significant financial impacts to projects and development organizations, many of which are nonprofits. These delays have ripple effects that in many cases:

- Put nonprofit organizations at risk of defaulting on predevelopment or acquisition loans and strain relationships with lenders and vendors.

- Create missed opportunities for site acquisition because of a lack of faith that HPD will be able to provide financial support in a timely manner.

- Put critical programming, such as workforce development and elder care, at risk due to lack of funding.

- Create pressure to decrease the affordability of the housing units, including raising rents or increasing sales prices of homeownership units, as developers must find ways to fill financing gaps that occur because of delays.

Summary of Recommendations

Institute Process Reforms to Address Development Pain Points

- HPD should follow-through on the implementation of a uniform intake process and a common loan application and establish a dedicated business development team. To the maximum extent feasible, HPD should also ensure there are uniform policies across term sheets and consistent underwriting standards, promote high-capacity staff to generalist or floating project manager positions, and consider creating more specialized roles for new initiatives. According to HPD, the agency has already begun to implement many of these critical reforms. The agency should publicly announce the changes in policy and continue to engage with external stakeholders to ensure the efficiency goals of those reforms are achieved.

- HPD should also continue its ongoing efforts to evaluate and create improvements in the processes of the BLDS, Marketing, and Legal divisions, many of which, according to HPD, have already been implemented and must now be communicated clearly to stakeholders.

- HPD must continue their work to update the agency’s term sheets expeditiously and OMB should fast-track review and approval of those updates. Once OMB has approved the new term sheets for each program, OMB should limit their review of individual project underwriting to ensure capital eligibility in alignment with Directive 10.[4]

Provide More Flexibility and Support for Affordable Housing Developers

- The City should supply funding to HPD to expand the Landlord Ambassador Program to provide critical support to lower capacity borrowers.

- HPD should create more flexibility for developers that have experienced significant pre-development or conversion delays, including increasing project subsidy when appropriate.

- The City should encourage various agencies (FDNY, ConEd, DOT, DEP, and DOB) to prioritize project approvals for HPD’s affordable housing, and should encourage inter-agency coordination toward streamlined approvals.

Enhance Training, Support, and Hybrid Work Options for Staff

- The City should create more opportunity for growth for project management staff at HPD. HPD should provide additional management training to new supervisors and require training on the history of community development in NYC and the role of partnerships between HPD and the nonprofit and for-profit sectors.

- HPD’s HR department should continue to ensure uniform implementation of Tasks and Standards and Annual Evaluations. HPD should additionally develop a consistent onboarding process for loan program staff.

- The City should continue to allow and encourage hybrid work schedules and HPD should work to create a culture of shared responsibility towards accomplishing the agency’s mission.

Upgrade HPD’s Technology

- Create an agency-wide CRM (customer-relationship-management) system for use across all departments at HPD.

- HPD should continue improving file management processes and develop project management best practices across the agency to ease transitions following staff departures and avoid duplication of work.

- The City should continue to invest in improvements to Housing Connect 2.0 and continue to work with marketing agents to identify needed improvements. This would free up the capacity of the marketing team to focus on matching tenants with appropriate affordable units, rather than troubleshooting technology problems.

- To fund these upgrades amidst City budget constraints, funding could be allocated from the Battery Park Joint Purpose Fund or from HDC reserves.

- For future technology projects, the City should permit HPD to participate in the “Expanded Work Allowance” program that the Office of the Comptroller is developing with City Hall, to allow reasonable flexibility for change orders with requiring full contract review.

History of HPD

The Housing Preservation and Development Department (HPD) was created during the fiscal crisis of the 1970s. In 1976, the City passed a law that shortened the length of time a property could be in tax delinquency before becoming eligible for tax foreclosure from three years to one. Instead of causing an uptick in property tax collection as intended, the new rule greatly increased the number of buildings owned by the City of New York – by the end of 1977 the City owned nearly 10,000 buildings, four times the number it owned just 6 months prior. Estimates indicate that about 35,000 apartments located within those buildings were occupied by over 100,000 residents.[5] Saddled with the unfamiliar and difficult task of managing thousands of buildings, including providing essential services to over 100,000 people, the City reimagined the existing Housing Development Authority and established the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD).[6]

HPD’s role in the redevelopment of New York is unique compared with other large cities across the country that were also struggling with capital disinvestment, high crime, and landlord abandonment.[i] HPD enabled New York City to adapt to the lack of federal funding for housing development after the 1970s by providing financing and technical assistance for renovations while frequently maintaining a long-term regulatory role.

From the beginning, HPD partnered closely with local groups that were rebuilding their communities and newly formed private sector financing organizations.[ii] The City transferred ownership and provided funding to a diverse set of entities including community groups, faith institutions, for-profit developers, and groups of tenants and squatters. Organizations utilized an array of approaches, including rehabbing buildings through sweat equity, which further reduced the cost of municipal funds needed to renovate.[7]

Building on the work of the agency during the first six years of his administration, Mayor Edward Koch released New York City’s first-ever 10 Year Housing Plan in 1986, which solidified the role of HPD in community development. The deployment of a significant level of municipal financing – bonds backed by the City’s general obligation – went far beyond other American cities and made a huge investment in the preservation and development of affordable housing. Over the next decade, the City spent nearly $5 billion to develop or renovate approximately 180,000 homes.

The use of City capital for affordable housing continued through the Dinkins, Giuliani, and Bloomberg Administrations, with variations in levels of funding and programmatic focus. In 2014, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a new 10-Year Housing Plan, in clear homage to Koch’s leadership, which represented a significant increase in the City’s goals for affordable housing development. De Blasio set a goal of building or preserving 200,000 units and signaled that the City would commit over $8 billion in capital; he upped the goal in 2017 to 300,000 by 2026 (i.e., over 12 years, continuing 4 years after his term in office was over), along with a focus on deeper affordability.

The long history of municipally financed housing preservation has been essential to maintaining the cultural fabric of New York City. Community and faith organizations, throughout the City, but in particular in the South Bronx, Harlem, the Lower East Side, Williamsburg, Bedford Stuyvesant, South Brooklyn, and Crown Heights acted as anchor institutions, leading the community development process, and thereby increasing social cohesion within neighborhoods. More recently, many of those same communities that experienced high levels of landlord abandonment and capital disinvestment have been subjected to extreme financial speculation.

Thousands of residents faced landlord harassment, including threats of physical violence and the intentional destruction of their homes, and other forms of displacement pressure. In those neighborhoods, and many others throughout the five boroughs, HPD financed and supported affordable housing that continues to operate outside the speculative market functioned as a bulwark against wider spread displacement. Without these affordable rental and co-operative developments, it is likely that many more families and individuals would have been uprooted and pushed out of their homes.

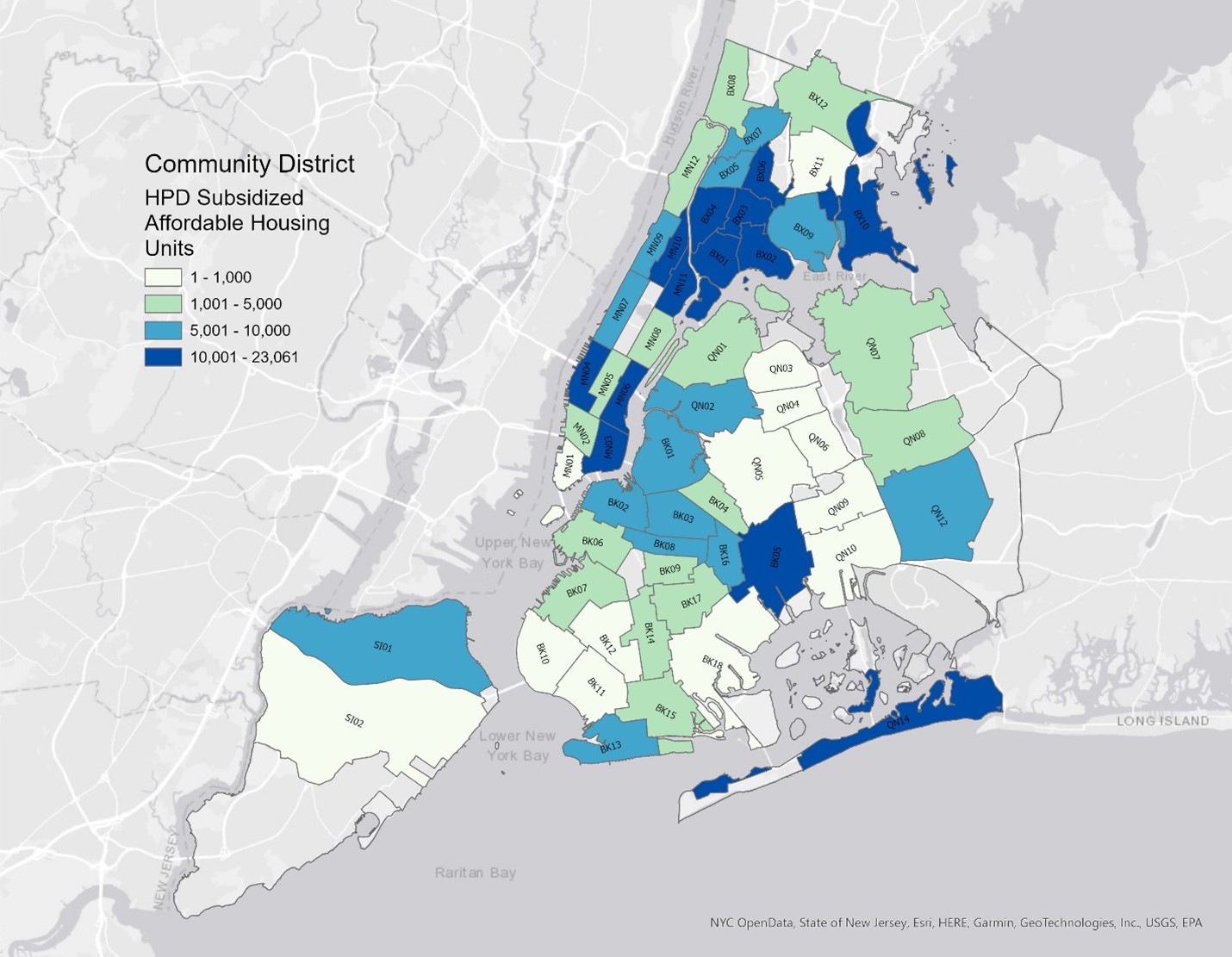

Community District HPD Subsidized Affordable Housing Units

Source: NYU Furman Center

Despite the sanctuary that this housing has provided for many, the pressures of displacement and affordability continue to affect over a million New York families. The 2021 Housing and Vacancy Survey found that the majority of households that rent in New York City (55%) are rent burdened, paying more than 30% of their pre-tax income towards housing costs.[8] Many low-income tenants, nearly 30% or just over 300,000 households, are severely rent-burdened, paying more than 50% of their pre-tax income towards housing costs.[iii] Eviction filings have returned to levels comparable to years preceding the 2020-2022 moratoria and are heavily concentrated in neighborhoods with predominantly Black and Latinx populations, such as the Northwest Bronx and Eastern Brooklyn.[9] Homelessness, which declined during the pandemic due to increased public spending on single-room shelters for New Yorkers living on the street and eviction moratoria, has now reached record highs.

The crisis affects New Yorkers unevenly but families across a wide range of incomes are feeling the pressure and more housing development at a range of affordability levels is needed to address the problem. In the last decade, the New York metropolitan area saw a 6% population growth with only a 3.5% increase in its housing stock. New York City and State need to build more housing, with an attention to fairness, sustainability, and infrastructure through comprehensive planning. Designing a fair tax treatment for new multifamily development, passing good cause eviction protections, and creating a framework for housing development across the metropolitan region are all necessary steps to increasing supply.

Chart 1

Source: Financial Management System

However, building more market-rate housing alone won’t ameliorate the challenges facing low-income New Yorkers nearly quickly enough. Between 2002 and 2021, New York City lost almost half of the apartments that are affordable to individuals or families earning less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level, or $41,182 for a family of three in 2020. The losses were most severe in Brooklyn, in which the number of affordable apartments decreased from 339,500 to 150,800 and Queens, in which the number of affordable apartments decreased from 158,700 to 68,000. These losses occurred across all types of housing, as landlords removed units from rent regulation, raised rents in unregulated housing, and transitioned formerly subsidized homes to market rates at the end of regulatory cycles.[10]

In contrast to Brooklyn and Queens, there was an increase in affordable homes for low-income families in the Bronx between 2014 and 2021, which is likely attributable to development funded through HPD’s capital programs. Ensuring that the new construction and preservation of affordable housing through HPD’s capital programs keeps pace with, and ideally exceeds the rate of production of the past ten years, must therefore be a core pillar of the City’s effort to combat the City’s housing affordability crisis.

Staffing Analysis

The authorized headcount at HPD was fairly stable between FY 2000 and FY 2008, but declined following the Great Recession, from 2,775 full time employees in FY 2008 to just 1,960 in FY 2013. Former Mayor Bill de Blasio increased staffing levels at HPD steadily after taking office in 2014, with the authorized headcount growing from 2,115 in FY 14 to 2,562 in FY 2020. The final budget of the de Blasio administration was passed in June 2020 during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and staffing levels remained stable, increasing by seven full time employees, to 2,569.

Chart 2

Source: City Human Resources Management System

From April 2020 until October 2022, almost a third of the full-time employees that worked at HPD, or 911 people, left the agency. During the same period the agency was only able to hire 625 new people, resulting in a net loss of 286 staff.[iv] Some periods were particularly devastating: between October 2021 to October 2022, 577 staff left the agency, including over 200 people with more than 5 years of experience at HPD – an unprecedented exodus when compared with the preceding ten years.

Chart 3

Source: City Human Resources Management System

The significant number of staffing losses between 2020 and 2022 has hollowed out the institutional memory of the agency, but HPD leadership has turned the tide. From the start of July 1, 2022, through December 31, 2023, HPD has hired hundreds of new staff – bringing on an additional 863 full time employees in the past six fiscal quarters while losing only 651 people. After nearly three and a half years of upheaval, HPD returned to staffing levels comparable with their pre-COVID baseline.

Chart 4

Source: City Human Resources Management System

Chart 5

Source: 2023 Mayor’s Management Report

There was substantial turnover in all of the areas of HPD, including among code inspectors, construction experts, lawyers, and other office personnel. This report is focused on the effect that staffing losses had on the agency’s ability to finance the new construction or preservation of affordable housing. Additional inquiry would be needed to better understand the effect on other core functions of the agency, such as code enforcement or neighborhood planning.

2020-2022: The Great ResignationInterviews with employees who worked at HPD immediately prior to the pandemic and have since left the agency or have left City service altogether provide insight into the agency’s loss of staff following the outset of COVID-19. While City agencies and workplaces in general saw significant loss of staff during this period (sometimes referred to as “the Great Resignation”), interviews with former HPD employees reveal specific workplace conditions that contributed meaningfully to staff burnout and attrition.

Many former HPD staff spoke of a “golden age” in 2018 and 2019, a time of peak productivity, staffing, and job satisfaction. This sentiment matches both the staffing and budget analysis conducted by the Comptroller’s office, as production of affordable housing was near all-time highs and exits from the agency were remarkably low. Several interviewees noted that they stayed in government service because they saw themselves as a small part of a larger, meaningful effort to combat the City’s affordability crisis and felt the immediate impact of their work in the lives of New Yorkers, despite widespread acknowledgement that they would make more money at a comparable job in the private sector. Once hiring freezes were put into place in 2020, however, the experience of staff started to change, with dramatic shifts occurring in 2021.

In June 2020, HPD faced a potential 40% cut in City capital in direct response to the COVID-19 pandemic. and capital commitments were not re-secured until October 2020.[11] Following this period of uncertainty there was increased pressure on staff from both the administration and developers to close projects that had been paused.[12] Due to the hiring freeze, the agency was unable to grow their teams or re-hire for staff who left the agency. This loss of staff and pressure to make up for the lag in development during 2020 significantly increased the workload — especially for experienced and high-capacity employees. To accomplish the same amount of work with many fewer people, a round-the-clock, all-hands-on-deck work culture emerged. Under those conditions, the remaining staff were able to accomplish amazing things. For example, the Special Needs Housing team hit an all-time high number of affordable housing starts in FY 2021, despite having fewer staff than the year prior.

However, as time went on and more staff departed, fatigue set in. Project Managers within loan programs felt they were letting down the organizations with whom they worked – project approvals slowed and the timeline between milestones increased with fewer staff across all parts of the agency. One person with whom the Comptroller’s office spoke, stated that a development partner asked them in reference to their ability to get them timely responses and approvals, “What happened? You used to be so good!” This type of feedback was obviously dispiriting to an employee who was working more hours than they previously had for the same level of pay, in the midst of the ongoing global pandemic. Multiple former staff referred to this process as a “death spiral” – as the work increased, more staff left, which only further increased the amount of work for the employees who continued to stick it out.

The departure of more senior staff did create some room for growth, which tends to be limited in government service but is critical for staff retention. Agency leadership did their best to recognize talented, hardworking members of the team – but it was incredibly difficult to get promotions and much needed raises approved by OMB.[13] Several interviewees referred to the City-mandated return to office in September 2021 as the “final straw” – after a difficult 18 months with unsustainable workloads and limited room for advancement, the requirement to work from the office five days a week was cited as a direct cause of their exit from the agency. When all was said and done, 911 staff members had left between April 2020 and October 2022, approximately 45% who had 5 or more years of experience.

The Effect of the Program to Eliminate the Gap on HPD In November 2022, the City rolled out the first of several consecutive Programs to Eliminate the Gap (PEGs) in an effort to achieve savings in the face of out-year budget gaps. These PEG programs have resulted in significant vacancy and headcount reductions at many City agencies. HPD, however, is a unique agency in that nearly 70% of headcount is funded through non-City tax levy (CTL) dollars; only the Department of Environmental Protection and the Department of Cultural Affairs have a higher rate of staff that are paid through non-City sources. Among other factors, the diversity of funding for staff has helped the agency avoid large reductions to date.

The Full Time and Full-Time Equivalent Staffing Levels of the FY 24 adopted budget, which provides forecasting for the fiscal years 2024-2027, authorized a headcount of 2,688 full time employees at HPD, with a reduction to 2,664 forecast by the end of June 2024, a loss of 24 full time employees. This is the first reduction in actual headcount at HPD since the fallout from the 2008 recession. HPD has minimized staffing losses in several key program areas, losing zero full time employee lines in the Office of Development and the Rental Subsidy Programs overall and gaining two staff lines in Housing Maintenance and Sales. The reductions in staff are located within the Office of Housing Preservation and the City’s ability to enforce the Housing and Maintenance Code as well as other key functions within that office should be monitored closely moving forward.

However, HPD does not work within a vacuum and timely approvals from several other City agencies – most importantly the Department of Buildings (DOB) and the Human Resources Administration (HRA) are critical to the successful completion of projects.

Analysis of Affordable Housing Production

Two indicators in the Mayor’s Management Report provide a high-level view of the agency’s ability to develop affordable housing, total affordable housing starts and total affordable housing completions, both measured by unit count. Affordable housing starts refers to the construction loan closing of a project – the time at which HPD provides capital and construction begins. Affordable housing completions refers to projects for which HPD has closed on permanent financing, at which time the project is typically fully stabilized, with tenants residing in the building.[v] There are also some projects where HPD provides a tax exemption or abatement or some other form of incentive in exchange for the owner signing a regulatory agreement and agreeing to maintain some or all of the units as affordable, but does not provide capital for repairs. Those units are also included in the MMR.

The number of affordable housing starts declined significantly during FY 22, dropping to just 14,793– or nearly 12,000 units below the average number of affordable housing starts over the four previous fiscal years. In contrast, after a reduction in affordable housing completions in FY 20 and FY 21, the number of affordable housing completions returned to pre COVID-19 rates in FY 22 and FY 23.

Chart 6

Source: Housing, Preservation & Development Data

But much nuance can be lost by just looking at the MMR or a press release. For instance, in FY23 HPD included the 2,592 of New York City Public Housing Authority (NYCHA) units financed through the Permanent Affordability Commitment Together (PACT) program in their announcement of a “record-breaking” year in the new construction of affordable housing, when similarly financed units had never been counted in the past.[14] If those units had not been included, rather than announcing that it was the second-highest year of production ever, the press release would have had to acknowledge that in FY 23, the City produced the second-lowest number of housing units (after FY 2022) since FY 2017, as was reflected in the MMR.

In order to better understand the impact of the staffing shortage on the City’s ability to finance the new construction and preservation of affordable housing the Office of the NYC Comptroller requested and received additional data from HPD. The data provided by the agency allowed the Comptroller’s office to evaluate the housing starts and completions by loan program and better understand the patterns of production at the agency. To be sure, a number of factors in addition to the staffing shortage affected the development of affordable housing, including a temporary freeze in City capital, rising construction and building operating costs, and inflationary interest rates. However, these factors affected both preservation and new construction projects – making the finding of staffing differences’ effect on production even more salient.

The work of the Office of Development within HPD is divided into New Construction, Special Needs Housing, Homeownership Opportunities, Preservation Finance, and Housing Incentives. While there may be overlap, and there have been some changes in what programs are included within each team over the past decade, the staff of each program currently reports to a distinct Assistant Commissioner within the Office of Development. Our analysis broke down the data provided by HPD into these categories to better match production by loan program to staffing trends.

Chart 7

Source: Housing, Preservation & Development Data

New Construction and Special Needs Housing

There were 3,869 units of newly constructed affordable housing and special needs housing started in FY 20, a significant drop in production from the three previous fiscal years, in which HPD financed, on average, 6,793 units per fiscal year. Construction starts rebounded in FY 21 to an impressive 6,743 units but dropped again in FY 22 to 4,856 units and production has not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels, with 5,923 units started in FY 23.

Chart 8

Source: Housing, Preservation & Development Data

The completions of newly constructed affordable housing and special needs housing have remained fairly stable throughout the past five years. There was an understandable drop in 2020, but levels have since recovered, and the number of units completed in both FY 22 and FY 23 exceeded FY 19 levels.

Chart 9

Source: Housing, Preservation & Development Data

The success of the new construction and special needs housing teams tracks closely to the staffing losses within those two divisions. The new construction team had minimal losses in FY 20 and FY 21 but lost an estimated 10 employees or nearly 50% of the team in FY 22 – the same year production declined after reaching record highs in FY 21. Overall, between FY 20 and FY 22 the Comptroller’s Office estimates that the team lost 19 people and was only able to rehire for 10 of those positions. In contrast, the special needs housing division lost only six full-time employees between March 2020 and October 2023 and each time a team member left the agency was able to replace them within the fiscal year.

Preservation

Affordable housing starts within the preservation loan programs reached an all-time high in FY 20, with 22,781 units financed. However, Co-op City, which contains 15,372 apartments, accounted for the majority (68%) of those units.[vi] While large projects in preservation finance have been a regular occurrence since 2017, they are atypical of the type of development that receives financing through HPD’s preservation loan programs; the median size of a project financed between FY 14 and FY 23 is just 87 units.

Chart 10

Source: Housing, Preservation & Development Data

When removing the financing of Co-op City from the data, it is clear that both FY 20 and FY 22 were extremely difficult years within the preservation loan programs. Unit starts in FY 20 were nearly 50% lower than the three previous fiscal years (FY 17 – 19), in which HPD financed, on average 12,899 housing starts per fiscal year. In FY 22, the level of production dropped to just a third of the rate of production for the three years prior to the pandemic, with just 4,120 units being started.

The number of completions also declined significantly in FY 20 and continued to drop for two years, reaching a low point of 3,814 units in FY 22, a third of the average number of units completed in the three fiscal years prior to the pandemic (FY 17 – 19). Completions recovered in FY 23, almost reaching, but not exceeding the average rate from FY 17-FY 19.

Chart 11

Source: Housing, Preservation & Development Data

Low production rates directly correlate to the staffing rates between FY 20 and FY 22. The preservation finance team experienced huge losses – with an estimated 43 employees leaving over the three-year period, meaning approximately 75% of the staff has turned over since 2020.

Housing Incentives

There was a slight decrease in housing starts within the housing incentives programs in FY 20, but the decline was more moderate than other divisions within HPD and has since increased greatly – nearly doubling in FY 21 and remaining at similar levels since. However, external factors unrelated to COVID-19 and agency staffing likely played a role in the increase of starts in FY 21 – 23, most notably the expiration of 421a in June 2022.

Affordable New York, or the most recent iteration of the State’s now-expired 421-a Program, is available to development projects that started construction between January 1, 2016, and June 15, 2022, and are completed on or before June 15, 2026. Modifications to the 421a application process, and a different level of involvement by agency staff between capitally funded projects and projects receiving only a tax abatement, make it difficult to compare the Housing Incentive division directly to other programs at HPD.

Chart 12

Source: Housing, Preservation & Development Data

What’s clear is that a significant number of housing starts in FY 20 – FY 23 (10,572 out of 65,367 or 16%) are attributable to developments incentivized with 421a. The high level of units will likely continue over the next two years as developers who rushed to break ground before June 15, 2022, finish construction and apply for the abatement by the summer of 2026. The deadline is during the final days of FY 25, underscoring the necessity of action in Albany during the 2024 legislative session.

Homeownership

Homeownership starts declined in FY 20 and FY 22 but given the small scale of the homeownership programs it is difficult to make determinations about the changes in production over time.[vii] A number of the programs, including HomeFix, the Senior Citizen Assistance Program, and products made available through partner organizations such as the Center for New York City Neighborhoods and Neighborhood Housing Services, are for small (1-4 unit) owner-occupied buildings. These programs provide support and financial assistance to homeowners who need to refinance existing mortgages or finance repairs. In addition, HPD provides down payment and closing cost assistance to first-time home buyers through the HomeFirst program.[15] The production of the Affordable Neighborhood Cooperative Program and Open Door, the two main programs at HPD that currently provide capital towards the development of new homeownership projects, is quite small – producing just over 1,000 units since 2017.

Chart 13

Source: Housing, Preservation & Development Data

Project Backlog and Increased Project Timelines

The data received from HPD allowed the Comptroller’s office to better understand the patterns of starts and completions within different loan programs at the agency, but it provided little information about the number of applications or the projects that are currently in HPD’s predevelopment pipeline. Projects are not formally tracked until HPD assigns a project manager and identification number, which increasingly occurs a significant time after initial application. This lack of insight into the backlog – driven by inadequate technology – limits the agency’s ability to properly plan and hinders staff’s communication about timelines to developers and partners.

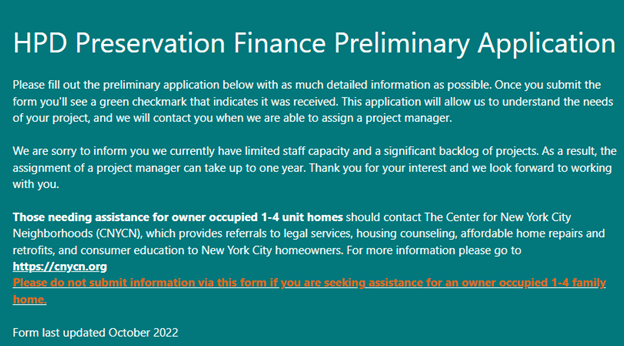

Despite a lack of data, interviews with stakeholders indicate that there is likely some backlog within the new construction, housing incentives, homeownership, and special needs housing divisions at HPD and that the predevelopment timeline for those projects has increased. The most significant backlog, however, is within preservation finance.

As of the release of this report, HPD’s website states that there is such a backlog in the preservation loan programs that it may take up to one year before a project manager is assigned to a project. This notice was placed on the website in early January 2022, and last modified in October 2022, indicating that for over two years, HPD has been forced to triage their acceptance of applicants due to a lack of capacity.

Projects that receive HPD capital through Special Needs, Preservation, and New Construction loan programs are also taking longer to complete – increasing the backlog of projects with outstanding construction loans. As noted throughout the report, the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant effect on construction and operating costs, ability of residents to pay rent, and interest rates. All of these factors impact construction timeframes and a project’s readiness for permanent loan conversion. Many of the recommendations made in this report seek to adapt the City’s processes and policies to be more in line with the current financial climate and to avoid slowdowns caused by a discrepancy in policy and the new reality of costs. With these recommendations, HPD can improve the efficiency of the conversion process from construction to permanent financing.

- From FY 17 – FY 19, it took on average 3.66 years for a project to go from construction loan closing to permanent financing within the New Construction loans programs. That average timeline increased to 4.86 years in the three years following the onset of the pandemic, between FY 21 – FY 23.

- For Preservation projects, the timeline for completion for FY 17 – 19 was 3.22 years, increasing to 4.05 in FY 21- 23.

- For projects within the Special Needs Housing loan programs the average timeline for project completion increased from 3.1 years in FY 17 – 19 to 3.75 years in FY 21 – FY 23.

Chart 14

Effects on the Affordable Housing Ecosystem

The HPD staffing shortage has had a significant ripple effect on the city’s affordable housing ecosystem, directly impacting the organizations that rely primarily on HPD to sustain and support their development of affordable housing. From the inception of the agency, HPD developed close partnerships with community-based organizations to feed its development and preservation pipeline and stabilize neighborhoods in the face of disinvestment and displacement pressures. These groups often take on the hardest projects, and own and manage some of the oldest, and most deeply affordable housing in the five boroughs. In addition to these community development corporations, there is a significant sector of M/WBE developers who specialize in affordable housing. They have become an essential partner, particularly in the new construction programs, and are a key component to the City’s long-term ability to tackle the housing affordability crisis.

HPD does not function without these organizations and vice versa. There is therefore an urgent need for the City to address the impact of HPD’s staffing shortage to maintain the ecosystem of affordable housing and community development within New York City. In addition, HPD leadership should continue to meaningfully engage with the leadership of these organizations, who have decades of experience developing affordable housing as they work to upgrade systems and improve processes.

Financial Burden on Organizations

HPD is involved in some way shape or form in nearly every single affordable housing project that is developed or preserved across the five boroughs, and in many cases, they are heavily involved in almost every step. Given the level of involvement, delays accumulate and can cause significant financial impacts to the individual project and the development organization undertaking it.

Due to a range of factors, including development project delays, nonprofit developers may have trouble making payroll, expanding their mission-driven programs, or retaining staff as projects stagnate and the satisfaction of the work declines. For-profit developers who build both affordable and market rate housing may shift the focus of their business, concentrating on market rate construction and less on affordable housing.

The current economy, including significant broader market trends that are pushing up interest rates and building operating costs, in particular insurance rates, are straining nonprofit capacity. To provide immediate support to vital community organizations, the State should provide $250 million in Emergency Affordable Housing Preservation Funds, with priority for the most vulnerable portfolios. In addition, the State should pass the legislation submitted with the budget that will prohibit insurance companies from refusing to cover affordable housing.

Acquisition Delays and Pipeline Development

Due to the high costs of land and housing in New York City, it is a rare opportunity to find a site that allows for the development of affordable housing. While some organizations, particularly for-profit organizations, may have enough cash on hand to acquire land or housing without getting a loan – most organizations need financing to purchase a site. Because subsidy from the City will almost always be needed to ensure the project’s long-term affordability, a soft commitment from HPD is often required to secure a loan from a financial institution or philanthropic lender. Several organizations with whom the Comptroller’s office spoke mentioned that due to the significant backlog of projects that has developed over the past several years, HPD has become hesitant to commit to a timeline for the construction closing and is typically unable to provide a written soft commitment. One for-profit developer interviewed by the Comptroller’s office has redirected their business away from affordable housing toward market rate development, as they struggled to gain clarity about HPD’s ability to finance projects in a timely manner.

Pipeline development over time is essential, as even in the best of times the pre-development process can be challenging and time intensive. In addition, market opportunities that financially allow for affordable housing development are rare – passing on the acquisition of sites in this moment means that there will be fewer projects in the queue of each organization and, in the long run, fewer affordable housing units in New York City.

Predevelopment Costs

The predevelopment process of affordable housing is expensive and can be complicated. Due to the significant cost, many organizations – both nonprofit and for-profit – take-out predevelopment or working capital loans to cover the cost. Predevelopment loans typically have a 24-month term with the assumption that they will be repaid with proceeds made available at the construction loan closing. When the process is delayed – sometimes 2 to 3 times the expected length of the time– developers must refinance or risk default. Based on their recent experience, one organization with whom the Comptroller’s office spoke stated that they had started looking for 5-year predevelopment financing to better comport with HPD’s current closing timelines.

A delayed repayment may strain developers’ relationships with the small number of lenders in New York that make these types of loans and requires additional staff capacity to manage the refinancing. It also adds cost to the project, as a new loan closing may require additional expenses, such as attorney fees, or new appraisals and surveys. The process of refinancing also gets more difficult over time, as lenders grow more concerned about the developer’s ability to close on construction financing and may be unwilling to take on the extra risk.

Some predevelopment loans are unsecured, with organizations taking out the loan against their balance sheet, which can tie up significant equity that could otherwise be used to build their pipeline of affordable housing or expand community-based programming. Additionally, any delays in payments to vendors can strain relationships with key partners, including architects, general contractors, and green energy consultants. There is a limited world of partners with whom affordable housing developers work, due to the detailed processes and expertise required to work well with HPD.

To better illustrate the financial impact on predevelopment delays, the Comptroller’s office developed a chart of typical expenses that must be paid prior to the construction closing in the below figure based on interviews with affordable housing developers. Each project is unique, but the estimates are a conservative estimate of a preservation project. Predevelopment costs for new construction projects, particularly ones that include rezonings, can be significantly more expensive. Most developers with whom HPD works have more than one project in pre-development at any one time – often as many as 5 or 10, increasing the amount of money required considerably.

Typical Predevelopment Costs

| Line item | Amount Paid During Pre-Development |

| Environmental Phase I + II | $12,500 |

| Enterprise Green Communities | $15,000 |

| Survey | $2,500 |

| Architectural Services | $35,000 |

| Borrower Legal | $25,000 |

| Appraisal | $10,000 |

| TOTAL | $100,000 |

Reliance on Developer Fees

Many affordable housing organizations rely on developers’ fees. Organizations need staff to vet projects, do the underwriting, and manage the extensive set of experts who are necessary to develop the scope of work for construction. However, developers do not receive a payment to cover the cost of the staff until the construction loan is closed and a portion of their fee is made available. The remaining fee is paid out in increments as the project hits key milestones and may not be paid in full even after the project has been fully stabilized. Interviewees indicated that it is now common practice that a large portion of the developer fee, sometimes up to 50%, is deferred at permanent conversion and paid out of the building’s cash flow over time. A project may take up to 5-8 years, particularly if a rezoning is involved, to work its way through the various approval processes that are required just to get the construction closing – the organization covers the cost of staff during that entire time. Delays on top of the existing long timelines, can cause significant financial strain on organizations, including cash-flow issues, an inability to give raises to staff, and limitations on expanding their pipeline.

In addition, many nonprofit organizations use developer’s fees to supplement philanthropic giving and government contracts that often do not cover the full cost of community-based programming. Delays in receiving developers’ fees can force nonprofits to reduce or close community-based programs, such as workforce development, tenant organizing, and elder or afterschool care.

Distressed Conditions and Decline in Workplace Satisfaction at Partner Organizations

The loan programs within preservation finance in particular tend to be utilized by small landlords, homeowners, affordable co-ops, and nonprofit developers. Delays in preserving and rehabilitating these buildings have a direct impact on the quality of life of low-income New Yorkers who live there.

Conversions of Distressed Buildings to Affordable Housing

The pipeline of key preservation finance and special needs housing programs is comprised of buildings that are currently in physical distress, often with dozens of HPD violations. Nonprofits either buy or are awarded occupied buildings after they have gone through City foreclosure or some other form of transfer of ownership. The nonprofit is tasked with rehabilitating the buildings and preserving the affordability for the existing tenants for the long term. However, there is often little money available prior to the construction loan closing to make interim repairs and stabilize the property. This can put nonprofit organizations in a difficult position and cause significant reputational risk. Additionally, if the renovation process is frequently delayed, it can make building trust with the residents in the buildings much more difficult for nonprofit staff.

In addition to making trust-building with residents more difficult, serious code violations and fines may be issued against nonprofit organizations. A core function of HPD is enforcing the Housing and Maintenance Code by responding to tenants’ complaints made to 311 about conditions. Tenants are absolutely within their rights to complain to HPD if there are any violations of the Housing and Maintenance Code in their buildings or apartments, however, when these violations and fines accumulate while the owner is working in good faith with another part of the agency to close on a construction loan, it can create a cycle of frustration for everyone involved.

Renovations of Existing Portfolio of Affordable Housing

Organizations may also have buildings in their portfolio that were renovated decades ago and require a preservation loan in order to finance upgrades. Most affordable housing is financed with tight margins to disperse City capital across as many projects as possible. This was particularly true of affordable housing that was transferred to community organizations and co-operators in the years following the fiscal crisis well into the 1990s, at which time renovation was frequently under-scoped.

While the cost of routine maintenance and repair are part of the operating budget for any building – extraordinary circumstances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which left many people unemployed and unable to pay their monthly housing costs, can cause serious operating shortfalls that make keeping up with repairs difficult. In addition to a reduction in rent collection, extraordinary increases in operating costs, in particular insurance rates, have destabilized many developments. Affordable housing projects that were about to hit year 15 or 30 from their original loan closing around 2020 may now have a few years of deferred repairs in addition to systems nearing the end of their useful life, making the need for renovation even more dire.

In market rate buildings, landlords or co-op boards can raise the rent or issue onetime assessment fees, but in affordable housing, the public sector is often the only source of funds for repairs. Many affordable housing tenants and landlords have been able to access Emergency Rental Assistance through the State’s program, however, it is understood that the remaining need still far outweighs the funds available and that many of these projects continue to struggle financially.[16] Delays in processing one-shot deals or other forms of temporary rental assistance can also exacerbate the problem. The State of New York should include additional funds in the 2024 budget to address the operational shortfalls at many community development corporations across the City, prioritizing the most vulnerable portfolios.

Loss of Trust with Tenants, Reputational Risk, and Staff Morale

Poor building conditions degrade trust between tenants and landlords, which can make the refinancing and renovation of the building more difficult for nonprofits and small landlords. Tenants lose faith that the project is actually moving forward and grow increasingly frustrated with the representatives from ownership, as they are most frequently the face of the delays. This can make the tenants less willing to cooperate with the process, including any temporary relocation that may be necessary. It can also negatively impact the broader mission of groups. Particularly those whose overall mission is building community power and can be demoralizing to staff, many of whom took the position to help create and secure affordable housing yet are left feeling as if they are seen as a negligent owner.

The “death spiral” conditions described earlier in this report regarding HPD staff during the pandemic can be seen too among the City’s nonprofit partners. In the wake of the “Great Resignation,” nonprofits are also often limited in the financial incentives that they can provide staff to continue doing mission-driven work. It is critical for nonprofit staff to feel the positive impact of their work in order to maintain their job satisfaction. According to interviewees, the delays caused by the staffing shortage at HPD are having the compounding effect of causing more turnover at affordable housing development organizations, further eroding the brain trust of affordable housing expertise in the city. Having experienced staff at both nonprofit organizations and the City is essential to maintaining high quality affordable housing throughout the five boroughs.

Projects Cost More and May Become Less Affordable

In a moment with rising interest rates and inflation, delays also have a significant impact on the affordability of projects. Missing a closing date may require additional subsidy just to maintain the prior affordability levels, as long-term debt service payments are tied to the amount of rent or maintenance fees paid by tenants or shareholders.

Construction loans are riskier, and typically have much higher interest rates than longer term mortgages on stabilized properties. Each month that a project is not able to convert results in an additional month of construction interest that needs to be repaid. While most projects are underwritten with a construction interest reserve in the event of delays, at some point these funds are extinguished and the cost accumulates. It cannot be covered by additional City subsidy at the permanent loan closing because it is not capitally eligible.

At this point in the project, it is very difficult to raise the residential rents or the purchase prices of homeownership units, as the units have already been marketed and in some cases leased up. The developer may be forced to cover this cost through their remaining fee or HPD may have to get creative about how to increase the subsidy to cover the cost. However, if it is still possible, the residential rents or sales prices may be raised to support the cost through additional private debt – either on behalf of the project or the individual homeowner, reducing the overall affordability of the project.

In addition to construction interest that must be paid, interest rates of the permanent loan may rise over time as delays occur, particularly in the current environment. Rising interest rates lower the level of private debt that a project can support and therefore increase the level of public subsidy that is needed to maintain the same level of affordability. The Public Private Apartment Rehabilitation Program (PPAR) available through the New York City Retirement Systems (NYCRS) is helpful in mitigating this risk. The PPAR program can help private borrowers lock in permanent loan interest rates 24 months prior to the completion of construction, but there are limits to the number of extensions that can be provided, as the City’s pension funds need to achieve a risk-adjusted market rate of return for retirees alongside the mission of providing a long-term fixed interest rate for the development of affordable housing in New York City.

HPD Process Pain Points

The effort of the agency to hire up over the past year is impressive. However, our interviews with dozens of organizations that develop affordable housing in New York City and our findings about turnover within key program areas indicate that there will continue to be growing pains as the agency develops new staff and seeks to clear the backlog that developed over the past two years.

While staff turnover among project managers, senior project managers, and members of HPD’s junior leadership team, including Directors, Executive Directors, and Assistant Commissioners, were frequently cited by interviewees as contributing to project delays, five themes were consistently raised when interviewees were asked about pain points: Building and Development Services (BLDS); Legal; and Marketing; the Office of Management and Budget; and deficient technology.

Many interviewed developers and former staff noted that these five pain points existed prior to the staffing shortage and had only been exacerbated by the loss of institutional memory. Before the pandemic, delays and frustrations would occur but were manageable, as previous project managers had learned how to navigate the internal and external processes to get things unstuck and keep projects moving. In contrast, newly hired staff have less support from supervisors and peers and less time to learn the process before leading projects on their own.

Moments of upheaval are also moments for reflection and change. As the agency restabilizes after a period of high staff turnover, HPD leadership should use this moment to continue its ongoing work of re-evaluating and streamlining certain development processes, building upon recent successful efforts and initiatives.

Building and Development Services (BLDS)

BLDS publishes and regularly updates design guidelines for the construction or rehabilitation of affordable housing financed with City capital. The guidelines allow the agency to enact policy goals, such as requiring minimum apartment sizes, allowing residents to age in place, and avoiding the institutional design of affordable housing. The most recent iteration of the design guidelines makes clear that the current primary goal is meeting New York City’s ambitious and critical climate goals.

The design guidelines set consistent expectations while also laying out “reach” goals for resiliency, energy efficiency, health and wellness, accessibility, and age-friendly design, as well as broadband and building operations. These guidelines are essential to ensuring that affordable housing is well-designed and provided with the City capital needed to meet core policy goals. Without making these goals explicit and required, it would likely be very difficult to justify additional capital spending on long-term climate goals, in particular.

BLDS involvement in HPD financed projects varies based on the loan program, the type of construction, and the scope of rehabilitation that is necessary. However, every project financed with City Capital goes through some type of BLDS review process, even if it is just applying for a waiver.[viii]

BLDS staff conduct a design review: evaluating site plans, architectural drawings, and scopes of work to ensure compliance with HPD design guidelines, and accessibility standards. BLDS may also review various proposals from consultants, including conducting a plan and cost review for some projects to ensure cost reasonableness. Staff within BLDS review the environmental reports conducted by experts and some projects also require an engineering review of the structural, mechanical, electrical, and plumbing plans. Once a project closes, BLDS monitors the construction to assure that projects are built according to the as-built plans, are constructed with quality workmanship, and are completed in a timely manner.

In limited cases, BLDS staff may develop the scope of work themselves. The role is particularly impactful for smaller nonprofit owners and co-operatives that may not have the funds necessary to pay private consultants to do this work during the pre-development stage.

The December 2022 Get Stuff Built report, drafted by the Building and Land use Approval Streamlining Taskforce (BLAST), included two recommendations that relate to BLDS. Recommendation 80 states that HPD will develop a two-track process that allows certain projects to be eligible for an expedited and limited design review and will develop a review process checklist and standardized comments. Recommendation 110 states that HPD will outline the requirements for moderate and substantial rehabilitation projects within the preservation loan programs and as applicable will rely on plan and cost reviews done by external partners. Finally, it states that HPD will work to better understand the pain points in the preservation loan process, including streamlining the work of BLDS.[17]

The inclusion of these recommendations in the BLAST report were amplified by many people with whom the Comptroller’s Office spoke who mentioned increased difficulty in receiving BLDS approval on projects since the onset of the pandemic. Some of the key themes included:

- Variation among reviewers, with a lack of oversight to ensure consistency across projects that require the same level of review

- Scope creep, including the provision of comments related to design or layout concerns that are not subject to HPD approval

- Inefficiency in rounds of reviews, including reviewers providing new comments in a subsequent round that were not caught previously

- Inaccessibility of BLDS staff, with increased difficulty meeting with BLDS reviewers directly once a submission has been made, making it more difficult to resolve problems that might be easily solved by a direct conversation

- Significant delays in the completion of in-house services, including BLDS developed scopes of work for occupied buildings with pressing renovation needs

- Increases in the costs of construction for projects with only HPD financing as contractors may factor in delays in payment from HPD as part of their overall cost estimates

HPD has recently accomplished the process updates included within recommendations 80 and 110 of the BLAST report. The agency has provided clarity as to how preservation projects will be classified as moderate or substantial/gut renovations and published detailed process guides for moderate, substantial, and new construction projects, which help developers better understand the requirements. HPD has also included details within the Substantial/Gut Rehabilitation Development Process that help developers ascertain if their project may be eligible for an expedited review.[18] HPD should work to share these updates with relevant development partners.

BLDS has also made considerable effort to facilitate inter-agency approval over the past several years, establishing a program that liaises with entities such as MTA and Con-Edison. In addition, HPD hired a Chief of Staff within the BLDS program, a new position, with a job description specifically aimed at continuing to improve the processes of this essential component of the agency.

Legal

HPD’s legal team is responsible for drafting legal documents or making changes to template agreements to fit the needs of each project and negotiating the terms with the owner and their attorney. HPD attorneys represent the City of New York and are responsible for ensuring that risk to the City is mitigated and that the City’s interests are well protected in the near and long term.

Many people that the Comptroller’s office interviewed discussed delays related to legal review. Some of the key themes included:

- Severe staffing shortages that have caused slowdowns in getting attorneys assigned to projects once requested by the Project Managers

- Attorneys being assigned to a project late in the process and raising legal concerns that cause delays

- Attorneys more frequently making unilateral decisions, rather than communicating the potential legal risks and allowing program staff to make determinations or utilize discretion as staff turnover accelerated and institutional memory eroded

- Legal staffing shortages resulting in delays to the creation of larger policy documents, such as updated regulatory agreements for co-operative developments

- Conversions to permanent financing becoming “mini closings” despite a lack of substantive changes to legal terms of the deal

In March 2023, the President of the Housing Development Corporation (HDC) sent a memorandum to the Board that discussed the staffing shortages HPD was experiencing, in particular in the Office of Development and Legal Affairs. The memo stated that HPD and HDC will be entering into a memorandum of understanding to establish the Capacity Accelerator Program, which will be funded with $12.8M from HDC’s unrestricted reserves. As part of the program, HDC issued an RFP for Legal Services that was due on August 4, 2023.

The RFP states that HDC intends to select up to three firms to provide legal services in connection with HPD financed affordable housing development. As of October 24, 2023, the City has entered into contracts with 5 legal service providers for a total contracted amount of $700,000. Several of the firms that were selected through this RFP had existing contracts with the City to perform legal work with HPD, indicating that these contractors had already been successfully assisting HPD’s internal legal department. In addition to entering into contracts with a number of legal providers that can support the work of agency counsel, HPD has also significantly increased the head count of staff within the Office of the General Counsel that close affordable housing transactions.

Given the number of factors that must be considered and lined up in order for a project to convert to permanent financing (See Appendix 1), there should not be delays related to re-negotiating standard legal documents that have not substantively changed since the construction closing. HPD has begun to include auto-conversion language into their loan documents as appropriate, allowing for projects that have hit all necessary milestones to move forward with much more limited legal review. This change will also allow the new conversion unit at HPD to focus on their efforts on difficult projects, that may have conversion issues related to significant changes since construction closing, tenancy problems, open violations, or inter-agency coordination.

Marketing

Once a project has reached 70% construction completion, or is approximately seven months away from occupancy, the owner is required to submit a notice of intent to market the vacant units to HPD and works closely with the agency to lease-up the building.[19] At this time, an HPD project manager within the marketing team is assigned to the project and works with the owner or their designated agent to advertise the vacant units, manage the lottery process, determine eligibility of applicants, and show the units to eligible prospective tenants until someone accepts and moves in.

Prior to 2013, there was no centralized system through which New Yorkers could apply for affordable housing that was financed with capital dollars. Regulatory agreements put in place by the City of New York set forth clear guidelines for affordability levels, but there was a wide variance in the ways in which developers found income-eligible tenants, raising concerns about how fairly those units were distributed. In order to create a fairer system, the City launched Housing Connect in 2013. The system was very bare-bones, but created a centralized process by which New Yorkers interested in affordable housing could apply for project-specific lotteries and through which developers could find eligible tenants.

Soon after launching, HPD scoped the technology upgrades that would be required to make the system function at a higher level, particularly considering the significant uptick of development that was underway following the announcement of former Mayor Bill de Blasio’s housing plan. The original scope for Housing Connect 2.0 from HPD staff was shared with the Office of Technology and Innovation (OTI), then DoITT (the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications), which refined the scope and managed the external procurement process. The contract was awarded to Prutech and signed on March 12, 2018.

Prutech’s Housing Connect 2.0 was an improvement upon the original model but a far cry from the tool that HPD had envisioned. There are significant and frequent glitches that are now the responsibility of HPD staff to solve. To be sure, HPD marketing staff spend a large portion of their time troubleshooting problems that the technology was supposed to solve, taking away staff time that would otherwise be spent on more speedily renting up units.

In Fiscal 2023, the median time to approve an applicant for lottery unit increased from 163 days in FY22 to 192 days – which means affordable units are sitting vacant for an average of over six months before a tenant is even approved to move in. The MMR states, “[t]his is due to the increased volume of units available for lottery without comparable changes to staffing.” Indicating that increased efficiencies will be needed in order to process the high number of currently open projects at HPD that will need to be rented up in the coming fiscal years. Interviewees indicated particular frustration with finding referrals from HRA, which is also undergirded by the MMR data, with the median time to lease a homeless set-aside unit in a new construction project increasing to 243 days (or about 8 months) from 203 days in FY 22.

Organizations with whom with Comptroller spoke also voiced concerns about the incompatibility of the Housing Connect platform for the marketing of homeownership units, both at initial lease-up and upon resale. The platform was developed primarily with rental developments in mind and does not currently allow a prospective purchaser to indicate if they are interested in homeownership or rental opportunities. This means that marketing agents for homeownership projects receive and must sort through a large number of uninterested or unqualified applicants.

Amendments made to Local Law 64 of 2018, which required all affordable housing projects to list their re-rentals or re-sales on Housing Connect, have reduced the burden on the shareholders and boards of HDFC co-operatives. However, a number of buildings that have signed recent regulatory agreements with the City are not exempt from the requirement and must use Housing Connect to market any units that are being resold. Interviewees with whom the Comptroller spoke stated that there is still a lack of clarity surrounding several key policy details that these shareholders or co-operative boards should follow when re-selling a unit. This lack of clarity may undermine the legitimacy of regulatory documents and result in future non-compliance.

The City has signed another contract with Prutech in April 2023 for $2.3 million to make additional upgrades to the Housing Connect system, which may reduce some delays. Both of the issues related to homeownership projects appear to within the scope of work of the contract and should be prioritized.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB)

A significant part of the project manager’s job at HPD is working with the developer and any private lenders to build the financial model or pro forma for the development. Each loan program at HPD has a publicly available term sheet that has been approved by OMB. The term sheet includes key information about eligibility, loan terms, and maximum subsidy amounts. The project manager also uses past actual expenses from a development and/or the current Maintenance & Operations standards, which are published annually by HDC to prepare an estimate of the operating expenses. [20] The project manager also uses either the existing rent roll or the affordability guidelines set forth in the term sheet to set the level of affordability, which dictates the annual income of the project, notwithstanding any commercial rent. Approval and a Certificate to Proceed from OMB is then required prior to the construction closing.

Supply chain issues since 2020 have greatly increased the cost of construction and of building operating expenses. Partners indicated the cost of construction per square foot for a non-prevailing wage job has increased significantly from early 2020 in early 2024[21] and in 2022, HDC announced that the Maintenance and Operations standards had increased 10.15% in just one year.[22] The federal reserve has also been raising interest rates to control for inflation, with the Long-term Applicable Federal Rate increasing from 1.93% to 5.03% between March 2020 and December 2023.[23]

Debt service payments to a private lender are covered from the payment of rent or maintenance by tenants or shareholders living in the affordable housing development. The monthly costs that residents pay are fixed and increases over time are limited. HPD loan programs develop housing for a range of income levels, but there is a policy goal to develop more deeply affordable housing. As operating costs increase and interest rates rise, the amount of private debt that the building can support is reduced. This increases the amount of City subsidy that is needed to reach the same affordability goals.