CFPB and NYC: How the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Empowers and Protects New Yorkers

Executive Summary

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) is a federal agency charged with protecting American consumers as they navigate our nation’s complex landscape of financial products, ranging from credit cards and payday loans to mortgages and student loans. Created by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act in 2008, the CFPB monitors both traditional financial service providers like banks and credit unions, as well as other providers of consumer financial services like auto lenders, debt collectors and others. In addition, the agency works to educate consumers about financial services products and, through its Office of Consumer Response, helps consumers resolve individual disputes or concerns.

Through its work, the CFPB has returned almost $12 billion to 29 million American consumers and has helped guard hundreds of thousands more against unfair, deceptive, or abusive products and services. And yet numerous proposals in Congress as well as recent legal actions could severely hamper the agency’s ability to serve as a fair and impartial advocate for consumers. Specifically, pending legislation would all but decimate the agency, including legislation that would dismantle the agency, replace the independent director with a five member commission, or change its funding structure to require annual appropriations from Congress.[1]

This report from New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer focuses on how the CFPB has helped protect consumers in the nation’s financial capital, New York City. Drawing on data from the agency’s Consumer Complaints Database, this report highlights the tangible assistance the CFPB has delivered to New Yorkers struggling with financial companies or products. The Database comprises nearly one million consumer complaints dating back to July 2011 and provides a rich set of data about the challenges facing consumers.

Some key facts and trends include:

- New York City residents lodged more than 23,700 complaints between December 1, 2011 and January 13, 2017, dealing with a full spectrum of financial issues.

- As the database has expanded to include more types of products, the number of complaints from New York City residents has risen from about 2,400 complaints per year in 2012, to almost 7,000 per year in 2016.

- Almost 22 percent of New York City complaints focus on mortgages, 19 percent concern credit reporting, and 17 percent pertain to bank accounts, credit cards, and debt collections.

- Over 90 percent of New York City consumers who submitted a complaint to the CFPB received a response from the target of their complaint, receiving either an explanation, a resolution to their issue, or monetary relief.

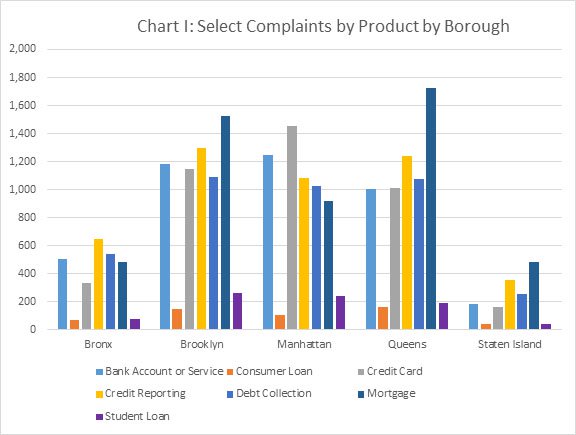

- Reflective of the differences in New York City’s neighborhoods (Chart I), there is variation in the types of complaints based on borough. While mortgages were the issue most frequently raised by residents of Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island, the most frequent complaint from the Bronx concerned credit reporting. The most frequent complaint from Manhattan concerned credit cards.

The increasing number of complaints and CFPB’s effectiveness at helping to resolve them demonstrates the important role that the agency plays in protecting New York City consumers. Proposals to scale back the scope and independence of the CFPB are misguided and should be rejected so that New Yorkers and all Americans can continue to enjoy the benefits of having a strong financial services regulator working to protect consumers every day.

History of the CFPB

In the months following the 2008 financial crisis, as the unemployment rate rose, the stock market tumbled and the country entered the most severe economic crisis since the Great Depression, members of Congress and the Obama Administration sought to create a consumer-focused regulatory agency to help prevent such a crisis from happening again. The resulting agency, the CFPB, was given a mandate to:

Protect consumers from unfair, deceptive, and abusive acts that so often trap them in unaffordable financial products … It will write rules and enforce those rules consistently, without regard to whether a mortgage, credit card, auto loan, or any other consumer financial product or service is sold by a bank, a credit union, a mortgage broker, an auto dealer, or any other nondepository financial company. This way, a consumer can shop and compare products based on quality, price, and convenience without having to worry about getting trapped by the fine print into an abusive deal.[2]

In creating the CFPB, Congress was responding to the specific shortcomings of the consumer financial regulatory regime in the years leading up to the 2008 financial crisis. Specifically, in the years preceding the 2008 financial crisis, the federal regulation of consumer finance was split between as many as twelve different agencies, and none of those agencies saw protecting consumers from abusive financial products as their single mission.[3]

In response to the scale of the financial crisis and the inability of the existing regulatory structure to adequately protect consumer interests, the CFPB was granted primary responsibility for overseeing consumer financial products, including mortgages, checking accounts, credit cards, payday loans, and more. Alongside addressing consumer complaints, the agency was given the authority to supervise certain consumer lenders (including both traditional banks and non-banks), enforce violations of consumer finance laws, and issue new rules and regulations.

Congress endowed the CFPB with a structure that would help it successfully accomplish this important mission. Unlike the other federal financial regulators that are funded through fees and/or annual appropriations from Congress, Congress made the CFPB a part of the Federal Reserve System (the Fed). This allows the agency to receive its money directly from the Fed rather than from annual Congressional appropriations that could be reduced at the whims of partisan politics. In addition, rather than be led by a multi-member commission that could become prone to deadlock or partisan squabbles, Congress stipulated that the CFPB would be led by a single director who would serve a term of five years.

Agency Accomplishments

In its short five year history, the CFPB has worked diligently to protect consumers, enforce common-sense financial regulation, and promote fairer, better markets for products ranging from auto insurance to home mortgages. Overall, the CFPB has returned almost $12 billion in the form of monetary compensation, cancelled debts, principal reductions, and other forms of relief to 29 million consumers.[4] According to the Center for American Progress, the CFPB has returned five dollars to consumers for every dollar it has spent.[5] The CFPB’s enforcement actions relating to discriminating lending alone has resulted in the return of more than $450 million to approximately 1 million harmed consumers alone.[6]

New York consumers have particularly benefited from the many of the CFPB’s efforts to empower and protect consumers. This report briefly surveys a number of CFPB’s recent accomplishments, highlighting how the CFPB has protected the pocketbooks of consumers in New York and across the country.

Student Loans

The CFPB has undertaken a number of initiatives to better protect students and those with outstanding student loan debt, including more than 900,000 New York City residents working to repay student loans.[7] In 2015, the CFPB initiated a public inquiry into the student loan servicing industry.[8] The resulting report drew on the evidence of over 30,000 comments that described a series of industry-wide issues, including hurdles to loan repayment and adjustment.[9] Ultimately the CFPB has recovered more than $100 million in student loan relief for harmed borrowers.[10] Recently, the CFPB launched a lawsuit against the nation’s largest student loan servicing company, Navient, alleging that the company has “systematically and illegally fail[ed] borrowers at every stage of repayment.”[11] These actions have given tangible help to the population of young New Yorkers with approximately $14 billion in outstanding student loan debt.[12]

Consumer Banking

The CFPB has helped to return money to consumers who have been victims of unscrupulous actions by consumer banks. The agency has initiated legal action against several banks for overcharging consumers, deceptive practices, and fraudulent practices.[13] For example, in September 2016, the CFPB assessed a record $100 million fine on Wells Fargo in response to the “widespread illegal practice of secretly opening unauthorized deposit and credit card accounts,” which also included Wells Fargo paying $2.5 million in monetary relief to consumers who were victimized by this illegal behavior.[14]

Beyond taking punitive action against this kind of behavior, the CFPB has worked to promote safe and affordable banking practices. The CFPB has issued pioneering research on overdraft fees and the plight of the unbanked and underbanked.[15] According to recent estimates, as many as 1.1 million New York City households are unbanked and underbanked and could benefit from the CFPB’s outreach and education activities.[16]

Credit Reporting

The CFPB has taken action on the behalf of consumers to improve credit reporting so that consumer’s credit scores are calculated fairly and accurately. By pressing credit card companies to make free credit scores available to their customers, the CFPB has improved the ability of consumers to access to real time information about their credit histories.[17] The CFPB’s assessment of racial disparities in credit reporting has real ramifications for New York City’s diverse communities and can be the foundation for future policy making.

Upcoming regulations

Continuing its long record of consumer-oriented advocacy and regulatory interventions, the CFPB is continuing to develop a number of important consumer protections. Unless disrupted by Congress or the Executive Branch, these proposed rules promise to further safeguard the financial wellbeing of consumers, including New Yorkers. Currently pending with the CFPB are important regulations on issues related to debt collection, mandatory arbitration clauses, overdraft policy, and payday loans.[18]

CFPB’s Consumer Complaint Database

One of the ways that the CFPB carries out its mission is by hearing directly from consumers and working with financial services companies to address consumer’s concerns. Through the CFPB’s Office of Consumer Response, members of the public are able to submit complaints about problems with financial products by phone, mail, email, fax, or online chat. The CFPB reviews those complaints and, if appropriate, shares them with the company named in the complaint so that the company and consumer can discuss the source of the complaint and respond appropriately. The CFPB tracks the outcome of these interactions and gathers input from consumers and companies alike.[19] In December 2016, the CFPB reported that it had handled over one million consumer complaints since opening its doors.[20]

As part of its work to respond to complaints, the CFPB maintains a Consumer Complaint Database that allows the general public to see the inquiries that the Bureau receives. Prior to being included in the public database, the CFPB reviews the complaint to determine if it meets the appropriate criteria and shares the complaint with the named company.[21] Complaints are shown to the public either once the named company has made contact with the consumer or has been in possession of the complaint for 15 calendar days.[22]

In general, complaints listed in the Database include the date that the complaint was made, the state and zip code of the consumer, the type of product that was the subject of complaint, the specific issue with that product, and the company’s response to the complaint, if any. Since its launch the Database has evolved over time to include additional layers of detail and now includes complaints relating to the following types of consumer financial products: bank accounts and services, consumer loans, credit reporting, debt collection, money transfers, mortgages, payday loans, prepaid cards, student loans, and other financial services. [23]

The Consumer Complaint Database in New York City

This analysis from the Office of the Comptroller updates a January 2016 snapshot of complaints within the tristate area, with a more narrow focus on complaints originating from within the five boroughs.[24] As not every complaint includes a zip code, this analysis is unable to provide a complete picture of complaints from New York City residents. However, it does provide insight into the types of consumer financial challenges that New Yorkers face.

Between December 1, 2011 and January 7, 2017, more than 23,700 complaints were filed with the CFPB by consumers from the five boroughs (Chart II). The largest number of complaints were filed from Brooklyn 26.5 percent of total complaints), followed by Queens (27.3 percent), Manhattan (26.1 percent), the Bronx (11.5 percent), and Staten Island (6.5 percent).

Consistent with the CFPB’s January 2016 finding, the number of complaints has risen each year (Chart III). In 2012, the first full year of the Complaint Database, there were 2,418 complaints from New York City while in 2016 there were 6,917 complaints, an increase of 186 percent.

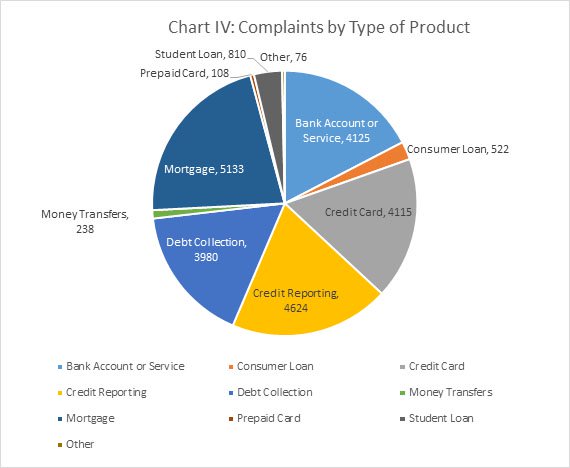

Mortgages account for the majority of complaints, comprising 21.6 percent of total complaints (Chart IV). In addition, other products with large numbers of complaints were credit reporting (19.4 percent), bank accounts and services (17.4 percent), credit cards (17.3 percent), and debt collection (16.8 percent).

Reflective of the differences in New York City’s neighborhoods, there is variation in the types of complaints based on borough (Chart V). While mortgages were the issue most frequently raised by residents of Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island, the most frequent complaint from the Bronx concerned credit reporting. The most frequent complaint from Manhattan concerned credit cards. Regional variations in complaint types demonstrates the CFPB’s ability to address the varying concerns of specific communities, where differing levels of home ownership, credit use, or other financial products may expose consumers to different problems.

Compared to the country overall, New York City residents are more likely to file complaints about bank accounts and credit cards and are much less likely to file complaints about debt collection and slightly less likely to file complaints about mortgages.

The CFPB has helped thousands of New York City consumers resolve their financial problems and issues. According to the Comptroller’s analysis of the CFPB database, 72 percent of complaints were resolved after the consumer received an explanation from the company, 12 percent of complaints resulted in the consumer receiving non-monetary relief (for example changing the terms of an account), and 9 percent of complaints led to the consumer receiving monetary relief (such as a refund). Furthermore, complaints are almost always resolved promptly as New York City consumers who file complaints with the CFPB report receiving a timely response 98 percent of the time.

Ultimately, the CFPB has left most New York consumers satisfied. Data indicates that the responses that consumer’s receive to their complaints are generally helpful. Indeed, 75 percent of complaints that were filed reached a resolution that was not disputed by the consumer who filed the complaint.

Stories from New Yorkers

Behind the wealth of statistical data supplied by the CFPB’s database, individual consumer complaints help provide insight into the types of issues that confront New York City consumers. Reviewing a sample of these complaints from the Database illustrates how the CFPB enables individual consumers to have their concerns heard and responded to.[25]

As illustrated above, consumers lodge complaints with the CFPB for issues both large and small. In December 2015, a Brooklyn consumer with a new credit card asked for help:

I signed up for a no annual fee credit card through Bank of America with a 0.00 % introductory APR for 12 months. However, I am being charged a {$1.00} ” Minimum Interest Charge ” on my statement every month. I called customer service the first time I noticed it, and they promised to remove the charge, but this has continued to happen every month since.

The CFPB made contact with the bank in question and was able to win a refund on the behalf of the customer. Given the compounding effect of even small fees, complaints like this one can have a big effect on consumer pocketbooks.

Other complaints demonstrate the CFPB’s ability to use individual complaints to discern larger issues. In November 2015, a Manhattan consumer wrote to the CFPB with an issue relating to a prepaid card:

My direct deposit posted to my Rushcard account on XXXX XXXX. It is 6 days later and due to computer ‘glitches ‘ I still have no access to the funds!

After reviewing the complaint, the CFPB promptly reached out to the prepaid card provider who responded to the complaint and, according to the Database, compensated the consumer. Complaints like these also alerted the CFPB and other federal regulators to more systemic issues involving this specific prepaid card. After finding that thousands of consumers were unable to access their funds for weeks, the CFPB recently ordered that the companies behind the card pay affected customers $10 million in compensation.[26]

Other consumer narratives also presaged larger action by the CFPB. In October of 2016, a consumer with an outstanding student loan wrote to the CFPB from Brooklyn:

Hello, I sent in a check to Navient to pay off one of […] my loans in full. I included a letter with the check and indicated on the check which loan the monies should be applied to. Navient did not apply the monies to the correct loan. The loan does not show it is paid in full. Instead they arbitrarily spread the monies through all (XXXX) loans.

According to the Database, the consumer’s complaint was responded to by Navient and the consumer was granted some relief. This individual case played out just months before the CFPB sued Navient for failing to assist borrowers in paying off loans. The CFPB referenced the complaints filed by “tens of thousands of borrowers and cosigners”.[27] Consumer narratives like these can help policy makers identify issues faced by individual New Yorkers and craft regulations, publish educational materials, or take enforcement actions to address problems plaguing consumers.

Conclusion

This report documents the many important contributions that the CFPB has made to the financial security of New York City residents. Despite these significant accomplishments, however, numerous proposals have been put forward in recent years that would fundamentally weaken the ability of the CFPB to carry out its important mission. Among those include legislation introduced in Congress that would severely restrict the CFPB’s regulatory clout, replace the independent director with a five member commission, or change its funding structure to require annual appropriations from Congress.[28]

In March 2017, as part of ongoing litigation, the Justice Department announced in an amicus brief that it now considers the CFPB’s structure to be unconstitutional. The Justice Department challenged the CFPB’s institutional independence and argued that the president must have the ability to remove the CFPB’s director at will.[29] Eliminating the Bureau’s single director structure could potentially compromise its independence from partisan politics and the influence of large corporations.

Any of these changes, if put into effect, would significantly weaken the ability of the CFPB to carry out its mission, if not dismantle the agency entirely.[30] Consequently, New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer calls on Congress to reject these changes and maintain the current structure of the CFPB so that it can continue to effectively carry out its important mission.

Acknowledgements

Comptroller Scott M. Stringer thanks Nichols Silbersack, Policy Analyst, and Zachary Schechter-Steinberg, Deputy Policy Director for their work crafting this report. The Comptroller also extends his thanks to David Saltonstall, Assistant Comptroller for Policy.

Comptroller Stringer recognizes the important contributions to this report made by:

Devon Puglia, Director of Communications; Tyrone Stevens, Press Secretary; Jack Sterne, Press Officer; Angela Chen, Senior Web Developer and Graphic Designer; and Antonnette Brumlik, Senior Web Administrator.

Endnotes

[1] S. 1804 and H.R. 3118, introduced in the 114th Congress, would repeal the portion of the Dodd-Frank Act that created the CFPB. S. 105, introduced in the 115th Congress, would change the structure of the CFPB to a five member commission. H.R. 5485, introduced in the 114th Congress, would require the CFPB to obtain annual appropriations from Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/1804/related-bills https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/3118 https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/105/text https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/5485

[2] https://www.congress.gov/111/crpt/srpt176/CRPT-111srpt176.pdf

[3] https://www.bu.edu/rbfl/files/2013/10/Levitin.pdf

[4] http://www.banking.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2017/1/banking-committee-democrats-trump-administration-needs-cordray-as-consumer-watchdog#_ftn4

[5] https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/news/2016/07/21/141664/many-happy-returns-for-consumers-the-cfpb-at-5-years/

[6] https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2017/03/28/429270/communities-color-cannot-afford-weakened-cfpb/

[7] Data current to Q4 2012: https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/databank.html

[8] http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb-rfi-student-loan-servicing.pdf

[9] http://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-concerned-about-widespread-servicing-failures-reported-by-student-loan-borrowers/

[10] http://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-recovers-107-million-in-relief-for-more-than-238000-consumers-through-supervisory-actions/

[11] http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201701_cfpb_Navient-Pioneer-Credit-Recovery-complaint.pdf and http://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-sues-nations-largest-student-loan-company-navient-failing-borrowers-every-stage-repayment/

[12] Data current to 2014: http://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/NYC_Millennials_In_Recession_and_Recovery.PDF

[13] http://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-orders-citizens-bank-to-pay-18-5-million-for-failing-to-credit-full-deposit-amounts/; http://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-takes-action-against-mt-bank-for-deceptively-advertising-free-checking/;

[14] http://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/consumer-financial-protection-bureau-fines-wells-fargo-100-million-widespread-illegal-practice-secretly-opening-unauthorized-accounts/

[15] http://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/consumer-financial-protection-bureau-launches-inquiry-into-overdraft-practices/; http://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/blog/forum-on-access-to-checking-accounts/; http://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-takes-steps-to-improve-checking-account-access/

[16] https://www1.nyc.gov/site/dca/media/pr092915.page

[17] http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201402_cfpb_letters_credit-scores.pdf

[18] https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaViewRule?pubId=201610&RIN=3170-AA40

[19] http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201604_cfpb_consumer-response-annual-report-2015.pdf

[20] https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2017/03/28/429270/communities-color-cannot-afford-weakened-cfpb/ https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201612_cfpb_MonthlyComplaintReport. pdf

[21] https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-03-24/pdf/2015-06722.pdf

[22] http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201604_cfpb_consumer-response-annual-report-2015.pdf

[23] http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201604_cfpb_consumer-response-annual-report-2015.pdf

[24] Data drawn from https://data.consumerfinance.gov/dataset/Consumer-Complaints/s6ew-h6mp and http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201601_cfpb_monthly-complaint-report-vol-7.pdf

[25] Comments are drawn directly from the consumer database. The CFPB does redact certain portion of comments to safeguard the identity and financial security of the consumer issuing a complaint. The Comptroller’s Office has made no independent determination as to the accuracy of the excerpted complaints but simply lists each comment as an example of the type of issues the CFPB addresses. Some comments are excerpted for brevity.

[26] http://money.cnn.com/2017/02/01/pf/cfpb-fines-unirush-mastercard-rushcard-blackout/

[27] http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201701_cfpb_Navient-Pioneer-Credit-Recovery-complaint.pdf

[28] S. 1804 and H.R. 3118, introduced in the 114th Congress, would repeal the portion of the Dodd-Frank Act that created the CFPB. S. 105, introduced in the 115th Congress, would change the structure of the CFPB to a five member commission. H.R. 5485, introduced in the 114th Congress, would require the CFPB to obtain annual appropriations from Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/1804/related-bills https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/3118 https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/105/text https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/5485

[29] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/17/business/dealbook/consumer-financial-protection-bureau-justice-department.html and https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2017/03/18/what-happens-when-the-department-of-justice-files-a-brief-against-a-federal-agency/?utm_term=.547220546292

[30] https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/news/2016/07/21/141664/many-happy-returns-for-consumers-the-cfpb-at-5-years/