Comments on New York City’s Fiscal Year 2019 Executive Budget

Executive Summary

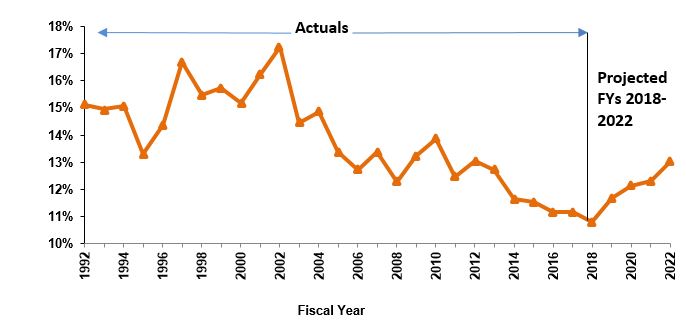

Both the national and local economies are expected to continue to grow in 2018 and for the remainder of the April 2018 Financial Plan period, fueled by a strong labor market and modest increases in wages. Recent Federal fiscal policy actions, including the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), provided a boost to an already healthy economy. However, expansionary federal fiscal policy will create higher budget deficits and rising interest rates. As such, the Comptroller’s Office expects growth to peak in 2018 and taper off in the latter years of the Plan period. Although the Comptroller’s Office is not projecting a recession, the course of the economy over the next two to three years will depend in no small measure on the ability of the Federal Reserve to respond appropriately to economic dynamics.

The Mayor has proposed an $89.1 billion budget for FY 2019, which is balanced by using a budget surplus of $3.7 billion estimated for the current fiscal year. The surplus increased by $1.1 billion in the Plan largely on the strength of a $973 million increase in FY 2018 tax revenues, but remains below the FY 2017 surplus of $4 billion. The boost to FY 2018 tax revenues is related to several factors, including changes in federal tax law, the repatriation of overseas hedge fund earnings, and a booming stock market – nearly all of which are one-time or likely to be transitory.

Overall, FY 2018 City-funds revenues in the current Plan are $1.03 billion more than projected in February. With the exception of FY 2022, the increases do not extend into the outyears, with City-funds revenues remaining relatively unchanged in FY 2019 through FY 2021, showing modest increases of $87 million and $3 million in FY 2019 and FY 2020 and a small decline of $68 million in FY 2021.

In contrast, City-funds expenditures have been revised upwards by more than $1 billion in each of FY 2019 through FY 2022. FY 2019 remains balanced because of an increase in the planned prepayment of FY 2019 debt service, funded primarily by the largely one-time increase in FY 2018 tax revenues. Without any offsetting increase in revenues in the outyears, however, the gaps have increased by $1.03 billion in FY 2020, $1.39 billion in FY 2021 and $509 million in FY 2022. The outyear gaps are now projected to be $3.22 billon, $2.86 billion, and $2.25 billion in FY 2020 through FY 2022, respectively. While these are not unmanageable gaps under current projections, any sharp or sustained slowdown in revenue growth could make them more difficult to manage without imposing difficult choices.

The Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the Financial Plan projects additional budget surpluses of $636 million in FY 2018 and $213 million in FY 2019, followed by larger gaps of $3.5 billion in FY 2020 and $3.0 billion in FY 2021, and a smaller gap of $2.20 billion in FY 2022. The Comptroller’s Office’s revenue forecast is consistently higher than the City’s, driven primarily by a higher tax revenue forecast, which is $706 million above the City’s in FY 2018, and ranging from $201 million to $882 million higher in FY 2019 through FY 2022. The Comptroller’s Office also estimates higher non-tax revenues of $29 million in FY 2019 and $27 million in each of the outyears of the Plan.

Tempering the budget relief from potential higher revenues is the Comptroller’s expenditure estimates, which, on net, are consistently higher than the Plan projections, resulting in net risks to expenditure estimates in every year of the Plan. The expenditure risks begin at $70 million in FY 2018 and grow each year, reaching $857 million by FY 2022. The growth in expenditure risks in the outyears is driven principally by the absence of funding for additional charter school tuition expenses. Despite a change in State legislation which allows charter school tuition to grow at the same rate as public school spending, the Financial Plan does not fund the cost of this growth.

In FY 2018 and FY 2019, the difference between the Comptroller’s Office’s revenue forecast and the City’s outweighs the expenditure risks, leading to the projection of net surpluses. In FY 2020 and FY 2021, the additional revenues forecasted by the Comptroller’s Office are insufficient to offset expenditure risks, resulting in higher projected gaps by the Comptroller’s Office. In the last fiscal year of the Plan, the additional revenues forecasted by the Comptroller’s Office are slightly higher than the expenditure risk, resulting in a modest reduction in the gap.

Despite the generally positive outlook, the Comptroller urges that any additional revenues in FY 2018 be treated as non-recurring and be set aside to bolster the surplus available to the City in future years. The Comptroller also continues to urge the City to undertake a rigorous review of agency budgets to find recurring savings in the form of efficiency and productivity enhancements. Additionally, the rapid growth of spending in several agencies, highlighted in the Comptroller’s Agency Watch List for the Departments of Correction and Education and for citywide homeless services, calls for careful evaluation to determine whether City funds are being used as effectively and efficiently as possible to achieve stated objectives. As it stands, the information necessary for such an evaluation is often incomplete and not publically available (if it is collected). The path to a sustainable fiscal future must begin with a careful examination of current spending. Any savings realized should be set aside to enhance the City’s budget cushion to allow the City to better weather a future slowdown, or downturn, without unnecessary drastic actions.

Table 1. FY 2018 – FY 2022 Financial Plan

($ in millions) |

FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | Change FYs 2018 –2022 Dollar Percent |

|

| Revenues | |||||||

| Taxes: | |||||||

| General Property Tax | $26,383 | $27,974 | $29,477 | $30,891 | $31,880 | $5,497 | 20.8% |

| Other Taxes | 30,585 | 31,046 | 32,151 | 33,150 | 33,894 | 3,309 | 10.8% |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 1,299 | 1,056 | 721 | 721 | 721 | (578) | (44.5%) |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $58,267 | $60,076 | $62,349 | $64,762 | $66,495 | $8,228 | 14.1% |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 7,128 | 6,789 | 6,830 | 6,735 | 6,714 | (414) | (5.8%) |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (2,208) | (1,824) | (1,770) | (1,774) | (1,774) | 434 | (19.7%) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 85 | (15) | (15) | (15) | (15) | (100) | (117.6%) |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $63,272 | $65,026 | $67,394 | $69,708 | $71,420 | $8,148 | 12.9% |

| Other Categorical Grants | 1,088 | 879 | 871 | 866 | 861 | (227) | (20.9%) |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | 646 | 682 | 641 | 638 | 638 | (8) | (1.2%) |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 8,799 | 7,507 | 7,127 | 7,106 | 7,089 | (1,710) | (19.4%) |

| State Categorical Grants | 14,865 | 14,969 | 15,299 | 15,760 | 16,243 | 1,378 | 9.3% |

| Total Revenues | $88,670 | $89,063 | $91,332 | $94,078 | $96,251 | $7,581 | 8.5% |

| Expenditures | |||||||

| Personal Service | |||||||

| Salaries and Wages | $27,146 | $28,717 | $29,611 | $30,359 | $30,060 | $2,914 | 10.7% |

| Pensions | 9,632 | 9,852 | 9,903 | 10,162 | 10,367 | 735 | 7.6% |

| Fringe Benefits | 9,989 | 10,733 | 11,647 | 12,418 | 13,098 | 3,109 | 31.1% |

| Subtotal-PS | $46,767 | $49,302 | $51,161 | $52,939 | $53,525 | $6,758 | 14.5% |

| Other Than Personal Service | |||||||

| Medical Assistance | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $0 | 0.0% |

| Public Assistance | 1,583 | 1,605 | 1,617 | 1,617 | 1,617 | 34 | 2.1% |

| All Other | 30,860 | 29,505 | 28,864 | 29,085 | 29,364 | (1,496) | (4.8%) |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $38,358 | $37,025 | $36,396 | $36,617 | $36,896 | ($1,462) | (3.8%) |

| Debt Service | |||||||

| Principal | $3,023 | $3,056 | $3,591 | $3,517 | $3,658 | $634 | 21.0% |

| Interest & Offsets | 3,207 | 3,906 | 3,920 | 4,386 | 4,951 | 1,743 | 54.4% |

| Subtotal Debt Service | $6,231 | $6,962 | $7,511 | $7,903 | $8,608 | $2,378 | 38.2% |

| FY 2017 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | ($4,180) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $4,180 | (100.0%) |

| FY 2018 BSA | $3,652 | ($3,652) | $0 | $0 | $0 | ($3,652) | (100.0%) |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | $250 | $250 | $250 | $250 | $250 | NA |

| General Reserve | $50 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $950 | 1,900.0% |

| Subtotal | $90,878 | $90,887 | $96,318 | $98,709 | $100,279 | $9,402 | 10.3% |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | (2,208) | (1,824) | (1,770) | (1,774) | (1,774) | 434 | (19.7%) |

| Total Expenditures | $88,670 | $89,063 | $94,548 | $96,935 | $98,505 | $9,836 | 11.1% |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $0 | ($3,216) | ($2,857) | ($2,254) | ($2,254) | NA |

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

Table 2. Plan-to-Plan Changes

April 2018 Plan vs. February 2018 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 |

| Revenues | |||||

| Taxes: | |||||

| General Property Tax | $114 | $115 | $141 | $273 | $981 |

| Other Taxes | 859 | (38) | (15) | (93) | (109) |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $973 | $77 | $126 | $180 | $872 |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 133 | 77 | (102) | (229) | (79) |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (76) | (67) | (21) | (20) | (20) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $1,030 | $87 | $3 | ($69) | $773 |

| Other Categorical Grants | (10) | 9 | 11 | 11 | 6 |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | (28) | 12 | 35 | 33 | 33 |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 149 | 288 | 154 | 151 | 150 |

| State Categorical Grants | 89 | 1 | (164) | (78) | (8) |

| Total Revenues | $1,230 | $397 | $39 | $48 | $954 |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Personal Service | |||||

| Salaries and Wages | ($127) | $146 | $217 | $322 | $383 |

| Pensions | 42 | 50 | 140 | 484 | 485 |

| Fringe Benefits | 17 | 55 | 90 | 100 | 99 |

| Subtotal-PS | ($68) | $251 | $447 | $906 | $967 |

| Other Than Personal Service | |||||

| Medical Assistance | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Public Assistance | (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All Other | 748 | 1,408 | 797 | 775 | 723 |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $737 | $1,408 | $797 | $775 | $723 |

| Debt Service | |||||

| Principal | ($151) | ($373) | ($4) | ($73) | ($59) |

| Interest & Offsets | (30) | 245 | (148) | (151) | (147) |

| Subtotal Debt Service | ($181) | ($127) | ($153) | ($224) | ($207) |

| FY 2017 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| FY 2018 BSA | $1,068 | ($1,068) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| General Reserve | ($250) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Subtotal | $1,306 | $464 | $1,091 | $1,457 | $1,483 |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | (76) | (67) | (21) | (20) | (20) |

| Total Expenditures | $1,230 | $397 | $1,070 | $1,437 | $1,463 |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $0 | ($1,031) | ($1,389) | ($509) |

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

Table 3. Plan-to-Plan Changes

April 2018 Plan vs. June 2017 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 |

| Revenues | ||||

| Taxes: | ||||

| General Property Tax | $369 | $235 | $374 | $667 |

| Other Taxes | 649 | 0 | (110) | (342) |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 449 | 335 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $1,467 | $570 | $264 | $325 |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 640 | 141 | (33) | (115) |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (393) | (87) | (31) | (30) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $1,814 | $624 | $200 | $180 |

| Other Categorical Grants | 208 | 11 | 12 | 10 |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | (25) | 18 | 39 | 36 |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 988 | 493 | 212 | 205 |

| State Categorical Grants | 446 | 97 | (72) | 33 |

| Total Revenues | $3,431 | $1,243 | $391 | $464 |

| Expenditures | ||||

| Personal Service | ||||

| Salaries and Wages | ($104) | $92 | $185 | $294 |

| Pensions | 60 | (19) | (40) | 157 |

| Fringe Benefits | (122) | (83) | (68) | (87) |

| Subtotal-PS | ($166) | ($10) | $77 | $364 |

| Other Than Personal Service | ||||

| Medical Assistance | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Public Assistance | (11) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All Other | 2,057 | 1,782 | 1,104 | 1,085 |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $2,046 | $1,782 | $1,104 | $1,085 |

| Debt Service | ||||

| Principal | ($151) | ($436) | ($7) | ($74) |

| Interest & Offsets | (147) | 173 | (344) | (354) |

| Subtotal Debt Service | ($297) | ($263) | ($350) | ($428) |

| FY 2017 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | ($11) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| FY 2018 BSA | $3,652 | ($3,652) | $0 | $0 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | ($250) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| General Reserve | ($1,150) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Subtotal | $3,824 | ($2,143) | $831 | $1,021 |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | (393) | (87) | (31) | (30) |

| Total Expenditures | $3,431 | ($2,230) | $800 | $991 |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $3,473 | ($409) | ($527) |

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

Table 4. Risks and Offsets to the April 2018 Financial Plan

($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap)

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | |

| City Stated Gap | $0 | $0 | ($3,216) | ($2,857) | ($2,254) |

| Tax Revenues | |||||

| Property Tax | $0 | $76 | $303 | $785 | $883 |

| Personal Income Tax | 730 | 182 | (117) | (190) | (260) |

| Business Taxes | 0 | 169 | 20 | 44 | 53 |

| Sales Tax | 0 | 91 | 179 | 149 | 85 |

| Real Estate Transaction Taxes | 26 | (23) | (384) | (483) | (79) |

| Audit | (50) | 100 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Subtotal Tax Revenues | $706 | $595 | $201 | $505 | $882 |

| Non-Tax Revenues | |||||

| ECB Fines | $0 | $20 | $20 | $20 | $20 |

| Late Filing/No Permit Penalties | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Motor Vehicle Fines | 0 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Subtotal Non-Tax Revenues | $0 | $29 | $27 | $27 | $27 |

| Total Revenues | $706 | $624 | $228 | $532 | $909 |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Overtime | ($100) | ($153) | ($150) | ($150) | ($150) |

| Charter School Tuition | 0 | 0 | (119) | (281) | (478) |

| DOE Medicaid Reimbursement | (50) | (50) | (50) | (50) | (50) |

| Carter Cases | 0 | (60) | (60) | (60) | (60) |

| CEP School Food Revenue | 0 | 0 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| Homeless Shelters | 0 | (33) | (42) | (42) | (42) |

| NYC Health + Hospitals | 0 | (165) | (165) | (165) | (165) |

| VRDB Interest Savings | 30 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| General Reserve | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | ($70) | ($411) | ($498) | ($660) | ($857) |

| Total (Risks)/Offsets | $636 | $213 | ($270) | ($128) | $52 |

| Restated (Gap)/Surplus | $636 | $213 | ($3,486) | ($2,985) | ($2,202) |

The City’s Economy Outlook

A. COMPTROLLER’S ECONOMIC FORECAST FOR NYC, 2018-2022

Economic growth is expected to continue in both the U.S. and New York City in 2018, and for the remainder of the April 2018 Financial Plan period. We expect growth to be more robust in the current and next calendar years, before tapering off in the outyears. An already healthy national economy, as reflected in the labor market, has received a boost from three major federal fiscal policy actions: the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, and the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2018. While these fiscal stimuli are expected to have a positive impact on real GDP in the short term, the projected $1.5 trillion decline in government revenues as a result of TCJA, combined with higher government expenditures, will lead to higher federal deficits, rising interest rates, and ultimately to slower GDP growth. Additional risks that would affect this economic forecast are a rise in inflation due to a multilateral trade war, geopolitical risks such as an escalation of tensions in the Middle East, or overly aggressive Federal Reserve interest rate increases.

Until recently in this cyclical expansion, New York City’s economy has been outperforming the nation. New York City is still the nation’s leading financial center and banks and financial institutions have been the major beneficiaries of corporate tax cuts, deregulation, and even the rise in interest rates. To the extent that these favorable factors are turned into wages, bonuses, or an increase in hiring, the City’s economy should prosper. Outside of the financial services sector, the City’s continuing strong job market along with modest growth in earnings are expected to fuel consumer spending and allow for moderate growth. The City’s other economic indicators are mixed, but point in the direction of moderate continued growth.

Table 5 shows the Comptroller’s and the Mayor’s forecast of selected economic indicators for 2018 to 2022.

Table 5. Selected Economic Indicators, Annual Averages

Comptroller’s and Mayor’s Forecasts

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

| Selected U.S. Economic Indicators Annual Averages | ||||||

| Real GDP (2009 $, % Change) | Comptroller

Mayor |

2.6

2.7 |

2.2

2.9 |

1.9

2.3 |

1.5

1.9 |

0.8

1.7 |

| Payroll Jobs (Change In Millions) | Comptroller

Mayor |

2.3

2.4 |

2.1

2.7 |

1.7

2.0 |

1.4

1.2 |

0.6

0.8 |

| CPI Inflation Rate (Percent) | Comptroller

Mayor |

2.1

2.2 |

2.3

1.7 |

2.2

2.7 |

2.2

2.5 |

2.1

2.4 |

| Fed Funds Rate (Percent) | Comptroller

Mayor |

1.7

1.8 |

2.5

2.8 |

3.2

3.3 |

3.7

3.4 |

3.2

3.5 |

| Selected NYC Economic Indicators Annual Averages | ||||||

| Real GCP (2009 $, % Change) | Comptroller

Mayor |

2.9

2.8 |

2.7

1.7 |

2.4

1.3 |

1.9

0.7 |

1.3

0.4 |

| Payroll Jobs (Change In Thousands) | Comptroller

Mayor |

64

60 |

46

54 |

43

52 |

37

50 |

10

35 |

| CPI Inflation Rate (Percent) | Comptroller

Mayor |

2.1

1.9 |

2.5

2.0 |

2.4

2.7 |

2.4

2.5 |

2.3

2.4 |

| Wage-Rate Growth (Percent) | Comptroller

Mayor |

3.5

3.2 |

3.6

3.0 |

2.8

2.8 |

2.3

2.9 |

2.0

2.8 |

Note: Comptroller=forecast by the NYC Comptroller’s Office. GCP=Gross City Product. Mayor= forecast by the NYC Office of Management and Budget in the Executive Budget Fiscal Year 2019 Message of the Mayor. NA=not available.

B. FACTORS AFFECTING THE FORECAST

The National Economy

The state of the nation’s economy is solid as reflected in real GDP growth and the tight labor market. The U.S. economy’s upward trend continued in the first quarter of 2018, albeit at a slower pace. Real GDP grew at a seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of 2.3 percent in the first quarter of 2018, after growing 2.9 percent in the fourth quarter of 2017. A strong labor market, modest increase in wages, and the latest fiscal stimuli suggest that this economic growth will continue and likely peak in 2018. However, expansionary fiscal policy will create higher budget deficits and rising interest rates. As a result, we project that economic growth will begin to taper off in the later years of the Financial Plan period, but fall short of a recession.

Half of the GDP gain was from private investment, which grew 7.3 percent. Most of the gains in private investment were in nonresidential fixed investment, which was almost equally divided between structures and equipment.

The surprise in the latest GDP report was the weakness of consumer spending, which grew only 1.1 percent. Consumer spending growth was the lowest in almost five years. Consumer sector has been the driver of the expansion thus far, and we don’t see this as the beginning of a trend. Three indicators — continuing job growth, rising wages, and lower tax rates — show that this sector is poised to contribute more growth. When we consider that American household balance sheets are strong and debt burdens are manageable, consumer spending should rebound to keep the expansion going.

Net exports contributed positively to GDP growth in first-quarter 2018. Higher growth in exports than in imports are an indication of the improvement in the global economy, while import growth is partially due to a stronger dollar vis-à-vis our trading partners. The dollar has been strengthening recently as a result of higher interest rates in the U.S. than in other places around the globe. A strong dollar helps imports but not exports and thus can be a drag on the future GDP growth.

Government expenditures rose 1.2 percent. Defense spending growth led non-defense spending growth 1.8 percent to 1.6 percent. State and local government expenditures rose 0.8 percent in first-quarter 2018 after growing 2.9 percent in fourth-quarter 2017. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, and the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2018 are expected to increase discretionary government expenditure and thus raise economic growth.

Jobs in the U.S. grew at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 1.7 percent in the first quarter of 2018, the highest increase in over a year, and the unemployment rate fell to 4.1 percent in the first quarter of 2018 (and to 3.9 percent in April), the lowest since 2000. A tight labor market led to a rise in wages. Wages, as measured by the average hourly earnings rose 2.4 percent in the first quarter of 2018.

The TCJA also lowered the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, making it the biggest one-time drop in business tax rates ever. This bodes well for corporate profits outlook. Private investment, specifically, real nonresidential investment, is expected to increase. Repatriation of corporate profits from abroad will provide a one-time bonus and a continuing flow as there will be no tax incentive to keep those earnings off-shore. In addition, investment in residential structures will be stronger, as evidenced by an increase in the number of building permits issued by local authorities.

Interest rates are expected to increase due to a rise in inflation caused by stronger economic growth, tight labor markets, and price increases as a result of higher wages.

So while the economy is expected to grow over the Plan period, it is expected to peak in 2018 and then begin to subside.

In general, our outlook for the US economy is slightly more pessimistic than that of the City. We expect growth to decelerate in 2021 and 2022, falling below the rates observed thus far in the recovery.

The New York City Economy

The City’s economy outperformed the nation for the second consecutive quarter in the first quarter of 2018 and it is expected to continue to do so for the remainder of 2018. The City’s relatively strong economic fundamentals and the fiscal stimulus, especially the corporate tax cuts that were signed into law in December of 2017, should fuel the City’s future economic growth.

The City’s economy, as measured by the gross city product (GCP), grew 2.7 percent in the first quarter of 2018, less than the 3.4 percent in the previous quarter, but higher than the 2.3 percent in the nation. Over the forecast horizon through 2022, the Comptroller’s Office is forecasting more robust growth than is being forecast by the Mayor. From 2018 to 2022, the Comptroller is forecasting GCP to grow 8.5 percent compared to the Mayor’s assumption of 4.2 percent, despite the fact that we are forecasting weakening growth rates in 2021 and 2022.

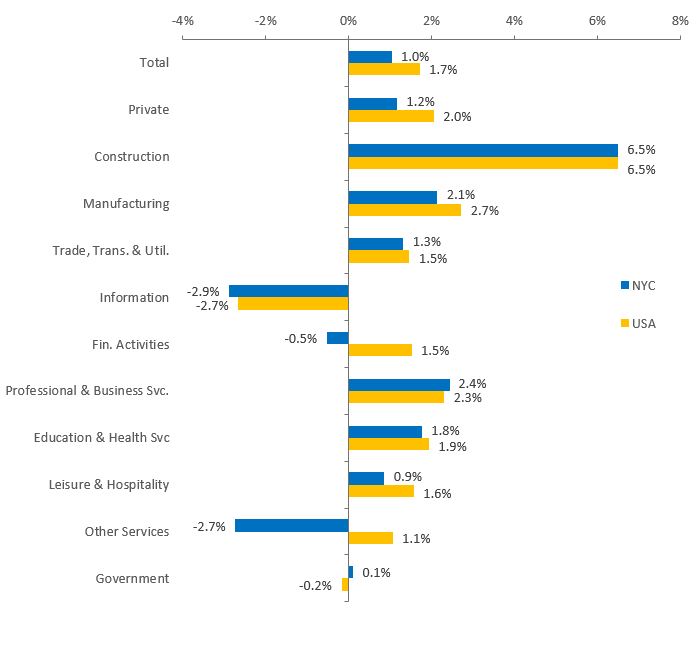

The private sector added 11,300 jobs, or 1.2 percent in the first quarter of 2018, about half of the 25,800 jobs created in the fourth quarter of 2017. U.S. private sector jobs grew 2.0 percent in the first quarter of 2018, faster than the 1.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2017 (Chart 1). Through 2022, the Comptroller is forecasting 200,000 new total payroll jobs compared to the Mayor’s forecast of 251,000. This may seem as a contradiction to the forecasts of GCP, but recent statistics suggest that New York, and the entire northeastern United States, can’t fill all jobs that are available. This supply constraint can keep employment constrained even though the GCP continues to grow at healthy rates.

Chart 1. Jobs Growth (SAAR) in NYC and the Nation

First-Quarter 2018 over Fourth-Quarter 2017

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and NYS Department of Labor.

NYC’s unemployment rate, adjusted for seasonality, fell to 4.3 percent in first-quarter 2018, the lowest rate on record. The unemployment rate can fall either as a result of a decline in the number of unemployed workers, an increase in the labor force, or a combination of both. The decrease in the City’s unemployment rate was due to a decrease in the number of unemployed, which declined by 6,700 in first-quarter 2018. The number of employed City residents increased by 6,000 in first-quarter 2018. As a result, the City’s employment-to-population ratio rose to 58.3 percent in first-quarter 2018, the highest ever. Despite the record percentage of New York City residents who are working, the percent of New Yorkers in the labor force still lags the nation by 2 percentage points, 62.9 percent to 60.9 percent.

Average hourly earnings (AHE) of all private NYC employees, a component of personal income, rose 2.3 percent on a year-over-year basis to $35.84 per hour in first-quarter 2018, less than the 3.3 percent increase in first-quarter 2017. U.S. average hourly earnings increased 2.4 percent in first-quarter 2018, also lower than the 2.8 percent increase in first-quarter 2017. This could partially be explained by the increase in the minimum wage, which grew either 14.3 percent or 18.2 percent (depending on the size of the employer) in 2017 from 2016.[1] The Comptroller’s wage growth forecast of 3.5 percent and 3.6 percent in 2018 and 2019, respectively, is higher than that of the Mayor at 3.2 percent and 3.0 percent. In the out years of the planning horizon the Comptroller’s forecast weakens considerably in line with our view that the economy weakens in those years as well.

The relatively strong labor market, the increase in earnings, and the continuation of U.S. expansion, in general, are expected to lift consumer spending in the City. In addition, private investment in the City is expected to get a lift from the new tax cuts. New York City is the nation’s leading financial center. As such, fiscal and monetary policies impacting the financial sector directly impact the City’s economy. The robust first-quarter 2018 banks’ earnings report bodes well for robust financial sector bonuses which will positively impact 2019 PIT.

The strong business environment and evidence that NYC is still a place where entrepreneurs can start and grow business is also reflected in venture capital investment. According to PwC Money Tree, venture capital (VC) investment in the New York metro area rose 61.2 percent on a year-over-year basis to $2.6 billion in the first quarter of 2018, its second highest first-quarter level on record.

Finally, the City’s latest leading economic indicators may be mixed, but they continue to signal growth.[2]

The FY 2019 Executive Budget

Overview: Changes to FY 2018 and 2019

FY 2018 Budget

The FY 2018 Budget in the April Plan totals $88.67 billion, an increase of $1.23 billion from the February Plan. The increase is primarily in the City-funds portion of the budget which has been increased by $1.03 billion to $63.27 billion. The non-City funds portion of the budget, which is funded by Federal, State and other categorical grants as well as funds from the capital budget, shows a net increase of $200 million.

As shown in Table 6, revisions to tax revenues account for $973 million of the increase in City-funds revenue, driven by an increase of $801 million in the estimate for personal income tax (PIT) revenues. As discussed in “Tax Revenues” beginning on page 26, the boost to the PIT revenue forecast stems from factors related to the Federal tax reform and the reform of the State PIT school tax relief (STAR) program.

Table 6. Changes to FY 2018 City-Funds Estimates from the Preliminary Budget

($ in millions)

| revenues | expenditures | ||

| Property Tax Revenues | $114 | Agency Expenses | $474 |

| Personal Income Tax Revenues | 801 | Miscellaneous Budget | 63 |

| Business Tax Revenues | (29) | Pensions | 42 |

| Sales Tax | 59 | General Reserve | (250) |

| Real Estate Transaction | 28 | State Budget Impact | (1) |

| All Other Tax | 1 | Citywide Savings Program | (366) |

| Subtotal | $973 | Subtotal | ($38) |

| Non-Tax Revenues | $55 | BSA | $1,068 |

| City Savings Program | $2 | ||

| Total | $1,030 | Total | $1,030 |

*Expenses exclude collective bargaining transfers.

The increase in City-funds expenditures is due entirely to an increase of $1.068 billion in the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) as shown in Table 6. Net of the increase in the BSA, City-funds spending is $38 million less than estimated in the Preliminary Budget. Agency spending is increased by $474 million. More than $250 million of this increase is in the Department of Homeless Services (DHS), with additional funding for shelter operations accounting for $213 million of the increase. Additions to the Department of Education (DOE) budget account for another $118 million of the increase, due primarily to an additional $80 million to fund special education Carter cases, and a $20 million increase in student transportation costs. The remaining increase reflects budgetary adjustments across various agencies. Other increases in the City-funds budget include $63 million in the miscellaneous budget and $42 million in pension contributions. Offsetting these increases are a $250 million takedown in the General Reserve and a new round of the Citywide Savings Program containing spending reductions of $366 million, including $181 million in debt service savings.

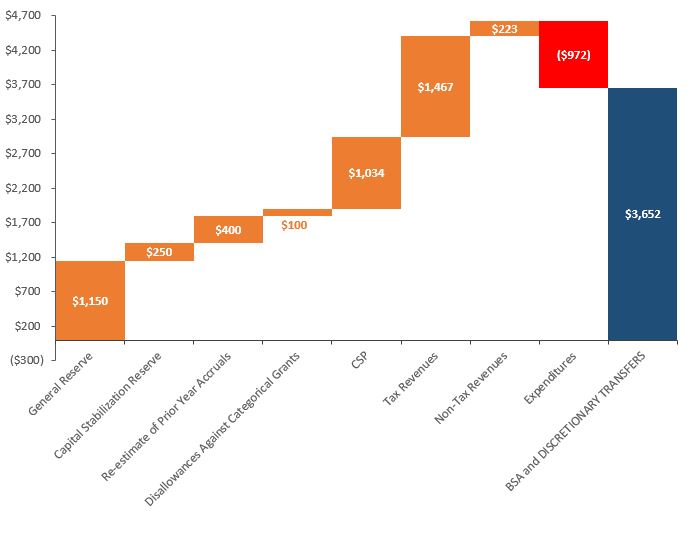

The increase in the BSA brings the total FY 2018 BSA to $3.65 billion. Since the Adopted Budget in June, the City has identified $4.62 billion of additional resources in the FY 2018 budget. About $970 million of the additional resources are used to fund additional spending. The remaining $3.65 billion are used to fund the BSA, which is earmarked to prepay FY 2019 debt service.

As Chart 2 shows, higher revenue forecasts and projected savings from the FY 2018 round of the Citywide Savings Program account for $2.72 billion of the additional resources. The takedown of reserves and adjustments to prior-year accruals account for the remaining $1.9 billion.

Chart 2. Funding the BSA and Discretionary Transfers

($ in millions)

FY 2019 Budget

The FY 2019 Budget in the April Financial Plan totals $89.06 billion, an increase of $397 million from the February Plan. The increase reflects primarily an additional $288 million in Federal categorical grants, discussed in greater detail in “Federal and State Aid” beginning on page 32. In contrast to the modified FY 2018 budget, the City-funds portion of the FY 2019 budget shows only a modest increase of $87 million.

As shown in Table 7, the increase in City-funds revenues is due primarily to an upward revision of $77 million in tax revenues. Property tax and PIT revenue estimates have been revised upward by $115 million and $194 million, respectively. Downward revisions of $115 million and $144 million, respectively, to business and sales tax revenues partially offset the increase in property tax and PIT revenues. The net reduction in sales tax revenues reflect the recognition of the State intercept of $150 million of the City’s sales tax revenues in FY 2019. [3]

Table 7. Changes to FY 2019 City-Funds Estimates from the Preliminary Budget

($ in millions)

| revenues | expenditures* | ||

| Property Tax Revenues | $115 | Agency Expenses | $791 |

| Personal Income Tax Revenues | 194 | Miscellaneous Budget | 155 |

| Business Tax Revenues | (115) | Pensions | 55 |

| Sales Tax | (144) | State Budget Impact | 531 |

| All Other Tax | 27 | Citywide Savings Program | (377) |

| Subtotal | $77 | Subtotal | $1,155 |

| Non-Tax Revenues | $1 | BSA | ($1,068) |

| City Savings Program | $9 | ||

| Total | $87 | Total | $87 |

*Expenditures exclude collective bargaining transfers.

As discussed in “FY 2018 Budget” on page 19, the FY 2018 BSA grew by $1.068 billion resulting in an attendant reduction in FY 2019 debt service. Net of the prepayment of debt service out of the FY 2018 BSA, FY 2019 City-funds expenditures are $1.155 billion above the Preliminary Budget estimates. The increase is driven by additional agency spending of $791 million and a State budget impact of $531 million. Similar to the changes in the FY 2018 budget, the largest increase in agency spending in FY 2019 is in the DHS. The additional spending for homeless shelter operations in FY 2018 is extended to the outyears, but at a lower amount of $160 million annually. The Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) also saw a significant increase of $140 million for FY 2019, driven by a $136 million increase in child care services spending.[4] Spending for child care services is also increased in the outyears but at a lesser amount of $122 million annually. The remaining agency spending increases are distributed across various agencies, with individual agency increases significantly below $100 million.

In addition to increased agency spending for new needs and budgetary adjustments, the enacted State budget resulted in additional City-funds spending in FY 2019 and the outyears through new spending requirements and reduced State support. As Table 8 below shows, the State budget impact will increase City-funds spending by $531 million in FY 2019 and more than $290 million in each of the outyears.

Table 8. State Budget Impact

| ($ in millions) | FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 |

| MTA Subway Action Plan | $0 | $254 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Raise the Age Implementation | 0 | 108 | 131 | 132 | 129 |

| Private Bus Subsidy | (1) | (3) | (3) | (3) | (3) |

| Education Aid Shortfall Backfill | 0 | 136 | 136 | 136 | 136 |

| State Budget Impact on Building Aid | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Close to Home | 0 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Total | ($1) | $531 | $295 | $296 | $292 |

Citywide Savings Program (CSP)

The April 2018 Financial Plan includes another round of the Citywide Savings Plan (CSP) that is expected to provide budget relief totaling $368 million in FY 2018, $386 million in FY 2019, $158 million in FY 2020, $228 million in FY 2021, and $218 million in FY 2022. With the exception of a procurement initiative in the Department of City Planning which is expected to save the agency $200,000 in FY 2020 and $130,000 in each of the remaining outyears of the Plan, all outyear savings are the result of recurring savings from FY 2018 and FY 2019 initiatives. Of the 138 new savings initiatives in the April Plan, 84 are scheduled to begin in FY 2018 with estimated savings of $368 million in FY 2018, $143 million in FY 2019, $103 million in FY 2020, $153 million in FY 2021, and $140 million in FY 2022.[5] Another 53 initiatives are scheduled to begin in FY 2019 with estimated savings of $243 million in FY 2019, $55 million in FY 2020, $75 million in FY 2021, and $78 million in FY 2022.

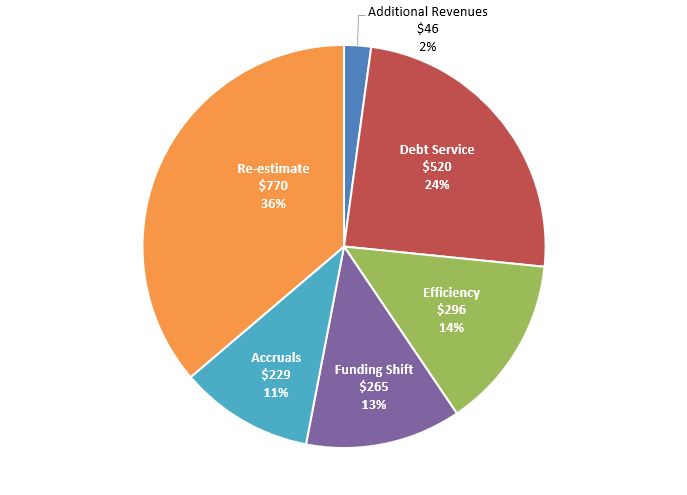

With the current round of CSP, estimated budget relief over the Plan period now totals $4.7 billion. The combined savings in FY 2018 and FY 2019 is $2.13 billon. As Chart 3 shows, debt service and re-estimates together account for 61 percent of the savings. Efficiency initiatives account for 14 percent of the total savings, an improvement from the last fiscal year’s CSP, where efficiency initiatives account for only 7 percent of total savings.[6]

Chart 3. Combined FY 2018 and FY 2019 Citywide Savings Program

($ in millions)

The Outyear Gaps

While FY 2018 and FY 2019 are balanced, the outyear gaps have increased by $1.03 billion in FY 2020, $1.39 billion in FY 2021, and $509 million in FY 2022. Outyear gaps are now projected to be $3.22 billion in FY 2020, $2.86 billion in FY 2021, and $2.25 billion in FY 2022. The increase in the gaps results from additional outyear expenditures which are not supported by additional recurring revenues. As Chart 4 shows, FY 2018 City-funds revenues are increased by $1.03 billion while expenditures are reduced by $38 million, resulting in additional resources of $1.06 billion. Beginning in FY 2019, City-funds expenditures have been increased by more than $1 billion in each year of the Plan. However, the revenue increase in FY 2018 does not extend into the outyears. FY 2019 is balanced because, as discussed above, the additional FY 2018 resources are earmarked to prepay FY 2019 expenses.

Chart 4. Change in the Outyear Gaps since February

($ in millions)

Risks and Offsets

As Table 9 shows, the Comptroller’s Office analysis of the April Plan shows net additional resources of $636 million and $213 million in FY 2018 and FY 2019, respectively, driven by the Comptroller’s Office’s tax revenue forecast, which is higher than the City’s projections in each year of the Plan. The Comptroller’s Office tax revenue forecast is discussed in greater detail in “Tax Revenues” beginning on page 26.

Risks to the City’s expenditure estimates offset some of the gains from the higher revenue forecast. Risks to the expenditure estimates stem primarily from assumptions of overtime spending and Health + Hospitals (H+H) support, and charter school tuition expenditures. Despite increases to the overtime budget in the current Plan, the Plan’s assumptions are still significantly below recent spending patterns. The Comptroller’s Office’s analysis indicates that overtime could be above Plan by $100 million in FY 2018, $153 million in FY 2019, and $150 million in each of the outyears of the Plan.

While H+H has yet to provide an update on its financial plan, recent improvements in its outlook will likely enable H+H to reimburse the City for fringe benefits expenses and medical malpractice settlements in FY 2018. However, given that H+H has missed these payments in prior years, the Comptroller’s Office continues to hold the assumption of outyear reimbursements at risk until there is a clear indication that H+H can consistently make these reimbursements.

Table 9. Risks and Offsets to the April 2018 Financial Plan

($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap)

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | |

| City Stated Gap | $0 | $0 | ($3,216) | ($2,857) | ($2,254) |

| Tax Revenues | |||||

| Property Tax | $0 | $76 | $303 | $785 | $883 |

| Personal Income Tax | 730 | 182 | (117) | (190) | (260) |

| Business Taxes | 0 | 169 | 20 | 44 | 53 |

| Sales Tax | 0 | 91 | 179 | 149 | 85 |

| Real Estate Transaction Taxes | 26 | (23) | (384) | (483) | (79) |

| Audit | (50) | 100 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Subtotal Tax Revenues | $706 | $595 | $201 | $505 | $882 |

| Non-Tax Revenues | |||||

| ECB Fines | $0 | $20 | $20 | $20 | $20 |

| Late Filing/No Permit Penalties | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Motor Vehicle Fines | 0 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Subtotal Non-Tax Revenues | $0 | $29 | $27 | $27 | $27 |

| Total Revenues | $706 | $624 | $228 | $532 | $909 |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Overtime | ($100) | ($153) | ($150) | ($150) | ($150) |

| Charter School Tuition | 0 | 0 | (119) | (281) | (478) |

| DOE Medicaid Reimbursement | (50) | (50) | (50) | (50) | (50) |

| Carter Cases | 0 | (60) | (60) | (60) | (60) |

| CEP School Food Revenue | 0 | 0 | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| Homeless Shelters | 0 | (33) | (42) | (42) | (42) |

| NYC Health + Hospitals | 0 | (165) | (165) | (165) | (165) |

| VRDB Interest Savings | 30 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| General Reserve | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | ($70) | ($411) | ($498) | ($660) | ($857) |

| Total (Risks)/Offsets | $636 | $213 | ($270) | ($128) | $52 |

| Restated (Gap)/Surplus | $636 | $213 | ($3,486) | ($2,985) | ($2,202) |

In the latter years of the Plan, the Comptroller’s Office projects net risks of $270 million in FY 2020, $128 million in FY 2021, and a modest offset against spending of $52 million in FY 2022. The net risks for FY 2020 and FY 2021 reflect both smaller divergences between our PIT forecast and the Plan, and higher expenditure risks. The higher expenditure risks beginning in FY 2020 are due to the lack of funding for charter school tuition increases. Despite a change in State legislation which allows charter school tuition to grow at the same rate as public school spending, the Plan does not include funding for the cost of this growth. The lack of funding poses a risk to the City’s expenditure assumptions.

Overall, the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the Plan indicates that the City could end FY 2018 and FY 2019 with budget surpluses of $636 million and $213 million, respectively. In the outyears, the Comptroller’s Office analysis shows larger gaps of $3.49 billion and $2.99 billion in FY 2020 and FY 2021, respectively, and a slightly smaller gap of $2.20 billion in FY 2022.

Revenue Analysis

The April 2018 Financial Plan increases total projected revenues by $1.23 billion in FY 2018 to $88.67 billion. The bulk of this increase reflects higher estimated tax revenues from the personal income tax (PIT). The April Plan also raises total revenue projections for FY 2019 by $397 million to $89.06 billion. This revision includes increases to State and Federal grants and City-fund revenues. Total revenues are forecasted to increase by 9 percent over the Plan period, from $88.67 billion in FY 2018 to $96.25 billion in FY 2022. Estimated tax revenues average 68 percent of total revenues over the Plan period. Property tax revenues are forecasted to rise 21 percent from $26.38 billion in FY 2018 to $31.88 billion in FY 2022, while non property tax revenues are expected to increase by 8.6 percent during the same period, from $31.88 billion in FY 2018 to $34.62 billion in FY 2022.[7]

Miscellaneous (non-tax) revenue estimates, excluding private grants and intra-City revenues, increased slightly for FY 2018 and FY 2019 in the April Plan to $4.92 billion and $4.96 billion respectively. The forecast for the outyears declined by a combined $461 million. The downward revision is mainly driven by the removal of revenues from taxi medallion sales assumed in the previous Plan. The current forecast assumes miscellaneous revenue will remain stable averaging $4.97 billion annually.

The April Plan projects total Federal and State aid of $23.66 billion for FY 2018, an increase of $238 million over the February Plan. Similarly, the City has recognized net additional grants of $289 million, almost entirely in Federal aid, in FY 2019. The additional Federal support is predominantly in the areas of social services, education and, to a lesser degree, Homeland Security funding and Community Development Block Grants. Federal and State aid are projected to grow from $22.48 billion in FY 2019 to $23.33 billion in FY 2022 driven mainly by the City’s expectation of State education aid growth.

Tax Revenues

Changes to the City Forecast

The City increased its tax revenue projections by $973 million in FY 2018 and by a combined $1.26 billion in FY 2019 through FY 2022. The increase in FY 2018 largely reflects stronger than anticipated PIT collections in the current fiscal year due to one-time factors related to tax reform. As Table 10 shows, projected PIT revenues increased by $801 million in FY 2018. Estimated property tax revenues increased by $114 million reflecting a decrease in current year reserves, while smaller revisions to other non-property tax revenue projections mainly reflect year-to-date collections through March. In the outyears, revisions to the tax revenue forecast result in net increases ranging from $77 million in FY 2019 to $872 million in FY 2022. The upturn in tax revenue projections results for the most part from increases in PIT and property tax revenue forecasts. Outyear revisions to property tax revenue are mostly driven by a higher than anticipated property tax levy, while forecast increases in PIT revenues result from higher projections for non-withholding PIT collections. Partially offsetting these increases are downward revisions to business, sales, and real estate transaction tax revenues in FY 2019 – FY 2022.

Table 10. Revisions to the City’s Tax Revenue Assumptions

February 2018 vs. April 2018

| ($ in millions) | FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 |

| February 2018 Financial Plan Total | $57,294 | $59,999 | $62,223 | $64,582 | $65,623 |

| Revisions: | |||||

| Property | 114 | 115 | 141 | 273 | 981 |

| Personal Income (PIT) | 801 | 194 | 213 | 120 | 16 |

| Business | (29) | (115) | (121) | (118) | (196) |

| Sales | 59 | (144) | (60) | (86) | 67 |

| Real Estate Transactions | 28 | 0 | (72) | (28) | (10) |

| All Other | 0 | 27 | 25 | 19 | 14 |

| Tax Audit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Revisions-Total | $973 | $77 | $126 | $180 | $872 |

| April 2018 Financial Plan – Total | $58,267 | $60,076 | $62,349 | $64,762 | $66,495 |

Comparison of Projected Tax Revenue Growth

The City and the Comptroller’s Office project tax revenue growth to accelerate in FY 2018 and then taper off for the remainder of the Plan period. As shown in Table 11, the Comptroller’s Office expects total tax revenue growth to accelerate to 7.9 percent in FY 2018, 1.3 percentage points above the City’s 6.6 percent growth projection. This is largely due to the Comptroller’s higher growth projection for PIT revenues in the current year compared to the City’s forecast. In the outyears, both the City and the Comptroller’s Office expect tax revenue growth to slow down to moderate rates as some of the tax revenue sources driving the FY 2018 growth are not expected to recur. The Comptroller’s tax revenue growth projection slows to 2.9 percent in FY 2019 and 3.1 percent in FY 2020 before picking up pace slightly in the latter years of the Plan period. The City and the Comptroller’s Office project overall tax revenue growth to average 3.4 percent annually over the Five Year Plan. A more detailed discussion of our projections and differences from the City’s forecast follows.

Table 11. Tax Revenue Forecast, Growth Rates

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FYs 2018 – 22 Average Annual Growth | |

| Property | ||||||

| Mayor | 6.9% | 6.0% | 5.4% | 4.8% | 3.2% | 4.8% |

| Comptroller | 6.9% | 6.3% | 6.2% | 6.4% | 3.4% | 5.6% |

| PIT | ||||||

| Mayor | 12.7% | (2.2%) | 4.8% | 3.2% | 2.5% | 2.0% |

| Comptroller | 19.2% | (6.2%) | 2.3% | 2.7% | 2.0% | 0.1% |

| Business | ||||||

| Mayor | 1.0% | 6.6% | 1.9% | 2.2% | (0.2%) | 2.6% |

| Comptroller | 1.0% | 9.6% | (0.6%) | 2.6% | (0.1%) | 2.8% |

| Sales | ||||||

| Mayor | 5.4% | 4.9% | 5.2% | 4.0% | 3.4% | 4.4% |

| Comptroller | 5.4% | 6.1% | 6.3% | 3.5% | 2.6% | 4.6% |

| Real Estate Transactions | ||||||

| Mayor | (5.6%) | 0.2% | (1.6%) | 3.3% | 3.0% | 1.2% |

| Comptroller | (4.6%) | (1.8%) | (16.8%) | (1.1%) | 24.5% | 0.1% |

| All Other | ||||||

| Mayor | 7.2% | 0.5% | 1.2% | 1.7% | 2.3% | 1.4% |

| Comptroller | 7.2% | 0.5% | 1.2% | 1.7% | 2.3% | 1.4% |

| Total Tax with Audit | ||||||

| Mayor | 6.6% | 3.1% | 3.8% | 3.9% | 2.7% | 3.4% |

| Comptroller | 7.9% | 2.9% | 3.1% | 4.3% | 3.2% | 3.4% |

Summary of Revenue Risks and Offsets

As shown in Table 12, the Comptroller’s Office projections show net offsets of $706 million in FY 2018, $595 million in FY 2019, $201 million in FY 2020, $505 million in FY 2021 and $882 million in FY 2022. In the current fiscal year the offset is driven by the Comptroller’s significantly higher PIT revenue projection. In FY 2019, the Comptroller’s Office projects most major tax revenues as well as audit revenues to be higher than the City’s estimates, producing a net offset of $595 million. In the last three years of the Financial Plan, the Comptroller’s Office anticipates shortfalls in most non-property tax revenues. However, the Comptroller’s Office’s higher projection for property tax revenues and audit revenues in the outyears will more than offset projected shortfalls in non-property taxes, leading to a combined $1.59 billion in tax revenues above the April Plan projections in FY 2020 – FY 2022.

Table 12. Risks and Offsets to the City’s Tax Revenue Projections

| ($ in millions) | FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 |

| Property | $0 | $76 | $303 | $785 | $883 |

| PIT | 730 | 182 | (117) | (190) | (260) |

| Business | 0 | 169 | 20 | 44 | 53 |

| Sales | 0 | 91 | 179 | 149 | 85 |

| Real Estate Transaction | 26 | (23) | (384) | (483) | (79) |

| Audit | (50) | 100 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Total | $706 | $595 | $201 | $505 | $882 |

Property Taxes

The Comptroller’s Office projects property tax offsets of $76 million in FY 2019 resulting from a reduction in total assessments between the tentative and final property tax rolls that are smaller than those anticipated by the City. Neither the Comptroller’s Office nor the City incorporate data from the final property tax roll for FY 2019, which will not be available until the end of May, in the forecast.

Although both the City and the Comptroller’s Office project slowing property tax growth, the Comptroller’s Office projects this growth will taper off more gradually, resulting in widening offsets in the outyears of $303 million in FY 2020, $785 million in FY 2021 and $883 million in FY 2022. These property tax offsets are smaller than in our February forecast, primarily as a result of the City increasing its own property tax revenue forecasts.

Personal Income Taxes

The Comptroller’s Office expects FY 2018 personal income tax revenues to grow by almost 20 percent. We concur with the City’s assessment that the boost to PIT revenues to date is driven in large part by non–recurring factors related to Federal tax reform – Public Law 115-97 the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). These include the shifting of income into FY 2018 due to the anticipation and enactment of the TCJA and the limitation of SALT deductibility, and two specific tax provisions: the Repatriation of Non-Qualified Deferred Compensation and the Transition Tax on Foreign Earnings.[8] Finally, a restructuring of the reimbursement of STAR caused withholding revenue to jump in FY 2018.

While these results are boosted by one-time tax related events, at the same time the underlying fundamentals of the City’s economy and Wall Street profitability are also strong. Assessing and distinguishing the impact of non-recurring and recurring factors on revenue is particularly challenging given the complexity of the provisions regarding the repatriation of foreign earnings and the scarcity of data available to assess these. The enactment of these complex provisions so late in the year meant that even tax filers and tax professionals had little time to determine their impact on tax year 2017 liability. Recognizing this, the New York State Department of Taxation and Finance circulated a notice on April 2018, indicating that it would weigh granting waivers for late payments.[9] This underscores the high degree of uncertainty that still surrounds this year’s filing season, which could have a large impact on PIT revenues in the remainder of the tax year. A detailed assessment of these factors and key differences with the City PIT forecast follows.

FY 2018: Based on collections data through the month of April, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that PIT revenue will exceed the City’s projections by $730 million. The City did not have full collections data for April and the month’s final tally was significantly higher ($650 million) than the City’s results indicate. All categories of non-withheld income, including offsets, were much higher than those indicated by the City in the Plan. The remaining months of the fiscal year are expected to build on this strength and upside, although there is considerable uncertainty regarding the second installment payment due June 15th.

FY 2019: As noted, the Comptroller’s Office concurs with the City’s assessment that FY 2018 are boosted by one-time nonrecurring revenues and our projection is that overall PIT will decline by 6 percent in FY 2019, driven by a 23 percent decline in non-withheld income. Even with this decline, non-withheld income is projected to be more than 8 percent higher than in FY 2017. Volatility and trading in the stock markets have picked up recently, suggesting that investors are seeking to realize gains accumulated with the run up in major indices over recent years.

Compared to the City, the Comptroller’s Office’s projected decline in PIT in FY 2019 is higher, but starts from a significantly higher base amount in 2018. Overall revenues therefore could be almost $182 million higher than the City estimates.

FY 2020 – FY 2022: Both the City’s and the Comptroller’s Office’s outyear forecast for PIT are predicated on continued but moderate economic growth with the economy approaching full employment. The Comptroller’s Office expects slightly lower growth in employment, 52,000 fewer jobs by FY 2022, and a marginally lower wage rate. As a result overall PIT revenue could be $260 million lower than the City projects in 2022.

In addition to the usual uncertainty regarding the long term forecast, out-year PIT results should be closely monitored to see if the limitation of SALT deductibility causes taxpayer flight. City PIT revenues could also be adversely impacted if employers opt into the State’s payroll tax, which would take effect starting in tax year 2019. A recent proposal by the Connecticut Department of Revenue Services to craft a tax credit for New York State payroll tax payments suggests that the possibility of opt-ins to the new payroll tax is being taken seriously.

Business Income Taxes

The TCJA also impacted the timing patterns of revenues from the City’s two business taxes, the general corporation tax (GCT) and unincorporated business tax (UBT). The projected decline in federal corporate business income tax rates and the incentive this provided to businesses to defer income into the current tax year was likely a factor explaining a projected FY 2018 decline of almost 6 percent. Conversely, UBT income, which is passed through to individuals, was likely boosted by the limitation imposed on SALT deductions by the TCJA.

Based on collections data through April, the Comptroller’s Office’s forecast for FY 2018 is similar to the City’s. In FY 2019 the difference is due to assumptions regarding the effects of income shifts due to the TCJA. The Comptroller’s Office assumes that the bounce back in GCT from FY 2018’s decline will be higher with growth of 13 percent compared to 9 percent assumed by the City. Similarly, for UBT the forecast growth of 4.2 percent following FY 2018 double digit growth is also marginally higher compared to the City’s forecast. Overall revenues from business taxes combined could therefore be $169 million higher than those shown by the City in FY 2019. In the outyears, the Comptroller’s Office and the City both expect growth in business taxes to moderate along with overall growth in the economy. The overall difference in the business tax forecast is minor in the outyears.

Sales Tax

Collections from the sales tax are projected to strengthen in FY 2018, supported by higher consumer confidence, low unemployment and steady wage and employment growth. The City and the Comptroller’s Office project sales tax revenue growth of 5.4 percent in FY 2018, the fastest growth since FY 2014. In FY 2019, the City forecasts growth in sales tax revenue to slow to 4.9 percent and reach $7.76 billion. This projection is net of the final $150 million in State intercept of sales tax revenues recognized in the April Plan. Over the Plan period, the City projects growth in sales tax revenue to average 4.4 percent annually, slightly below the Comptroller’s Office’s 4.6 percent growth forecast over the same period. The Comptroller’s Office forecasts sales tax revenues will grow by 6.1 percent in FY 2019 and 6.3 percent in FY 2020, producing offsets of $91 million and $179 million respectively. Although the Comptroller’s Office projects sales tax revenue growth to slow towards the end of the Plan, the Office anticipates that continued job and wage growth and strength in tourism will generate sales tax revenue in excess of the City’s forecast, producing offsets of $149 million in FY 2021 and $85 million in FY 2022.

The outyear forecast for Sales tax revenues could be impacted by a current case pending before the U.S. Supreme Court, South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc., which could overturn the physical presence rule for taxing online sales. The outcome of that decision is unknown but New York City could potentially receive a windfall in sales revenue tax revenue from this decision.

Real Estate Transaction Taxes

The City projects a decline of 5.6 percent to $2.39 billion in the combined revenues from the real estate transaction taxes in FY 2018, following a decline of 15.8 percent in FY 2017. In FY 2018, the City projects revenues from the real property transfer tax (RPTT) and mortgage recording tax (MRT) to decline by 0.8 percent and 11.6 percent respectively. Higher interest rates are expected to lower refinancing as well as overall sales in this period. The City projects real estate transaction taxes to average 1.2 percent growth annually over the rest of the forecast period.

The Comptroller’s Office projects a more moderate decline of 4.6 percent in the combined revenues from the real estate transaction taxes in FY 2018, to $2.42 billion, resulting in an offset of $26 million. However, in subsequent years, the Comptroller’s Office projects risks of $23 million in FY 2019, $384 million in FY 2020, $483 million in FY 2021 and $79 million in FY 2022. The Comptroller’s Office projects real estate transaction taxes to average 0.1 percent growth annually over the forecast period. The Comptroller’s Office’s projections of offsets in FY 2018 and risks in outer years are based on the correction in the residential as well as commercial markets after record sales, as well as projected increases in interest rates, slowing growth in Gross City Product, New York City employment and financial markets.

Audit Revenues

The Comptroller’s Office estimates that current year audit revenues could be $50 million less than indicated by the City in FY 2018. Although audit collections so far seem to be on pace, the last quarter of the current fiscal year anticipates a fairly aggressive tally to reach a record high of almost $1.3 billion in revenues. In contrast in the outyears, the City’s forecast of audit revenues assumes a very sharp fall off from current levels of $1.3 billion to just over $700 million in FY 2022. This decline would be unprecedented. Audit revenues are more likely to remain in a range around $1 billion. We recognize offsets of $100 million in FY 2019 and $200 million annually in subsequent years.

Miscellaneous Revenues

In the April 2018 Financial Plan, the City raised its FY 2018 miscellaneous revenue projection by a net $57 million, to $4.92 billion.[10] The revision includes approximately $2 million in revenue initiatives included in the Citywide Savings Plan. The current year projection is $103 million lower than the total miscellaneous receipts collected in FY 2017. The decline in FY 2018 reflects lower non-recurring revenues such as asset sales and other one-time payments in the current fiscal year. For FY 2019, the Executive Budget forecasts miscellaneous revenue to grow only slightly to $4.97 billion, a net increase of $10 million from the February forecast.

The current miscellaneous revenue projection removes from the Financial Plan $929 million in revenues from the sale of taxi medallions previously anticipated over FY 2019 – FY 2022, which the Comptroller’s Office considered a risk to the City’s Financial Plan. The City last sold taxi medallions in FY 2014, when medallion prices were at their highest level. Since then, the proliferation of ride-sharing services has put downward pressure on medallion prices. According to data from the Taxi and Limousine Commission (TLC), average medallion prices fell below $200,000. The City’s previous Plan assumed an average price of $728,000 per medallion.

Table 13 Changes in FY 2019 Estimates

February 2018 vs. April 2018

| ($ in millions) | February | April | Change |

| Licenses, Franchises, Etc. | $679 | $689 | $10 |

| Interest Income | 179 | 190 | 11 |

| Charges for Services | 985 | 1,005 | 20 |

| Water and Sewer Charges | 1,393 | 1,450 | 57 |

| Rental Income | 254 | 254 | 0 |

| Fines and Forfeitures | 930 | 943 | 13 |

| Other Miscellaneous | 535 | 434 | (101) |

| Total | $4,955 | $4,965 | $10 |

*Water and sewer revenues collected by the Water Board from dedicated water and sewer charges represent reimbursements for operation and maintenance of the water delivery and sewer systems and therefore are not available for general operating purposes.

The FY 2019 miscellaneous revenue budget reflects revisions to nearly all categories of miscellaneous revenue. As Table 13 shows, the largest revisions were in the categories “other miscellaneous”, water and sewer charges, charges for services and fines and forfeitures. Revenue projection for “other miscellaneous” which comprises asset sales, cash recoveries, refunds of prior year expenditure and other non-recurring revenues decreased by a net $101 million. The revision reflects primarily the removal of $107 million in revenues from taxi medallion sales previously assumed in FY 2019. Projections for charges for services and fines and forfeitures increased by $20 million and $13 million respectively. These changes mostly reflect planned increases in passenger and commercial parking meter rates, additional fee revenue from the Affordable Housing Program and higher estimated parking violation fines. Projected revenues from licenses, franchises and permits increased by $10 million to account for higher expected revenues from construction permits and Wi-Fi franchise revenues. Finally, the Plan raised the forecast for interest income by $11 million in FY 2019 to reflect the City’s anticipation of a steady increase in the federal funds rate.

Although the April Plan increased projections for most of the miscellaneous revenue categories in the outyears of the Plan period, the removal from the Plan of revenues from taxi medallion sales results in net declines of $123 million in FY 2020, $249 million in FY 2021, and $99 million in FY 2022 compared to the February Plan. Overall, miscellaneous revenues are expected to remain steady averaging $4.97 billion annually in FY 2019 – FY 2022.

Based on recent collection trend, the Comptroller’s Office expects revenues from fines to be above the City’s forecast by $29 million in FY 2019, and $27 million annually in each of FY 2020 – FY 2022. The Comptroller’s Office believes revenues from Environmental Control Board (ECB) fines could generate an additional $20 million annually in each of FY’s 2019 through 2022. Motor vehicle fines could be higher by $5 million in FY 2019 and $3 million in each of FY’s 2020 – 2022, while penalties from the Department of Buildings (DOB) are likely to exceed the City’s current forecast by $4 million annually in FY 2019 through FY 2022.

Federal and State Aid

The FY 2019 Executive Budget assumes $22.48 billion in Federal and State assistance, reflecting an increase of $289 million since the February Plan. About 82 percent of this total is expected to support education and social services spending. On a year-over-year basis, the FY 2019 assumptions represent a decline of nearly $1.2 billion from projected Federal and State support in the current year, largely attributable to the rapid decline in Sandy-related reimbursement and more conservative estimates of certain Federal grants in FY 2019.

Changes since the February Plan is almost entirely reflected in Federal grants, rising by a net $288 million. Net of Sandy-related funding, the City anticipates $7.3 billion in Federal assistance for FY 2019. Excluding an inter-agency transfer of $150 million for the EarlyLearn program between DOE and ACS, education grants has increased by $56 million from expanded participation in the Federal school food program ($38 million) and revised special education support ($18 million). The Executive Budget also reflects additional funding of $113 million in social services mainly for DHS, including $88 million for family and adult shelters and $17 million for hotel security. Other major changes in the Federal aid projections include increases of $44 million in Homeland Security grants, $37 million in Sandy-related reimbursement and $37 million in Community Development Block Grants mainly for New York City Housing Authority repairs.

In FY 2019, the City anticipates State grants to total nearly $15 billion, including $11.1 billion for education. While the City managed to avoid deep cuts in charter schools, special education and child welfare services totaling $338 million, the Executive Budget still reflects a significant negative impact of $531 million from the enacted State budget. The impact largely stems from unfunded mandates that the State has imposed on the City, which include City payment of $254 million to the MTA for subway improvement and implementation costs of $108 million for the Raise the Age program for adolescent offenders. In addition, the State enacted school aid appropriations that fell short of the City’s expectation by $140 million and eliminated reimbursement for the City’s Close to Home youth residential placement program of $31 million. These reductions in aid have been offset by additional State grants recognized by the DOE for charter schools and preschool special education, as well as additional asset forfeitures, leaving State aid projections virtually unchanged since the February Plan.

However, the City still has not yet reflected a modified formula for tuition payments to charter schools that, without additional State reimbursement or a change in the formula, could pose risks of $119 million in FY 2020, $281 million in FY 2021 and $478 million in FY 2022. The City could also face additional State aid reductions under the extension and expansion of executive budgetary powers adopted last year that provides the State Division of Budget with broad authority to respond to Federal budget cuts. If federal Medicaid receipts to New York State are reduced by $850 million, or if all other federal receipts are reduced by $850 million, in state fiscal years 2018 – 19 through 2019-20, the Division of Budget could present a plan to the Legislature to uniformly reduce related local aid disbursements. If the Legislature fails to adopt an alternative plan within 90 days, the budget director’s proposal would become law.

Over the remainder of the Plan, Federal and State grants are projected to range between $22.43 billion in FY 2020 and $23.33 billion in FY 2022. These projections represent average annual growth of about 1.25 percent from the FY 2019 projections, driven primarily by the City’s expectation of State education aid increases of more than 3 percent annually. Assuming these assumptions hold, the level of Federal and State support for the City’s expense budget would decline from about 25 percent in FY 2019 to less than 24 percent by FY 2022.

Expenditures Analysis

Total-funds FY 2019 expenditures in the April Financial Plan are projected to remain relatively unchanged from FY 2018, growing by a modest $393 million, or less than half a percentage point. However, both the FY 2018 and FY 2019 expenditures include prepayments which lower debt service expenditures in these fiscal years. In addition, expenditures in FY 2018 are further reduced by the take-down of the general reserve and the re-estimates of prior-year accruals. After adjusting for prepayments, and excluding re-estimates of prior-year accruals and reserves, expenditures are projected to grow from $89.55 billion in FY 2018 to $91.47 billion in 2019, a growth of 2.1 percent, as shown in Table 14.

Expenditure growth over the Plan period is driven by spending on wages and salaries, debt service, health insurance, and other fringe benefits excluding pensions. The combined spending in these areas is projected to grow by 19.6 percent over the Plan period, averaging 4.6 percent annually. All other expenditures, net of the General Reserve, Capital Stabilization reserve, and prior-year re-estimates, are projected to decline slightly by 1.5 percent over the same period, with a projected annual average decline of 0.4 percent.

Table 14. FY 2018 – FY 2022 Expenditure Growth Adjusted for Prepayments and Prior-Year Actions

| ($ in millions) | FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | Growth FYs 18-22 | Annual Growth |

| Salaries and Wages | $26,739 | $28,345 | $29,239 | $29,987 | $29,688 | 11.0% | 2.7% |

| Debt Service | $6,231 | 6,963 | 7,511 | 7,903 | 8,608 | 38.1% | 8.4% |

| Health Insurance | $6,186 | 6,787 | 7,353 | 8,014 | 8,603 | 39.1% | 8.6% |

| Other Fringe Benefits | $3,708 | 3,847 | 4,187 | 4,292 | 4,383 | 18.2% | 4.3% |

| Subtotal | $42,864 | $45,941 | $48,289 | $50,196 | $51,282 | 19.6% | 4.6% |

| Pensions | $9,520 | $9,740 | $9,791 | $10,050 | $10,255 | 7.7% | 1.9% |

| Medicaid | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Public Assistance | $1,583 | $1,605 | $1,617 | $1,617 | $1,617 | 2.1% | 0.5% |

| Judgments and Claims | $712 | $697 | $712 | $727 | $742 | 4.3% | 1.1% |

| Contractual Services | $17,288 | $16,059 | $15,553 | $15,690 | $15,804 | (8.6%) | (2.2%) |

| Other OTPS | $11,668 | $11,508 | $11,422 | $11,491 | $11,641 | (0.2%) | (0.1%) |

| Subtotal | $46,685 | $45,524 | $45,009 | $45,489 | $45,973 | (1.5%) | (0.4%) |

| Expenditures Before Reserves and Prior-Year Re-estimates | $89,548 | $91,465 | $93,298 | $95,685 | $97,255 | 8.6% | 2.1% |

| Prior-Year Accruals Re-estimate | ($400) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | ||

| General Reserve | $50 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | ||

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | $250 | $250 | $250 | $250 | ||

| Total | $89,198 | $92,715 | $94,548 | $96,935 | $98,505 | 10.4% | 2.5% |

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

Headcount

The Executive 2019 Financial Plan projects total-funded full-time headcount of 303,862 for fiscal year-end 2018, an increase of 31 from the February Preliminary Plan. Planned headcount remains relatively stable for FY 2019 and FY 2020, with increases in FY 2021 and FY 2022 to 308,124 and 310,903, respectively, as shown in Table 15.

Table 15. Total Funded Full-Time Year-End Headcount Projections

April 2018 Financial Plan

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | |

| Pedagogical | |||||

| Dept. of Education | 119,613 | 120,720 | 120,968 | 122,410 | 125,095 |

| City University | 4,441 | 4,441 | 4,441 | 4,441 | 4,441 |

| Subtotal | 124,054 | 125,161 | 125,409 | 126,851 | 129,536 |

| Uniformed | |||||

| Police | 36,078 | 36,105 | 36,110 | 36,110 | 36,110 |

| Fire | 10,914 | 10,946 | 10,946 | 10,946 | 10,946 |

| Correction | 10,427 | 10,226 | 10,242 | 10,242 | 10,083 |

| Sanitation | 7,543 | 7,657 | 7,670 | 7,670 | 7,670 |

| Subtotal | 64,962 | 64,934 | 64,968 | 64,968 | 64,809 |

| Civilian | |||||

| Dept. Of Education | 12,271 | 12,358 | 12,444 | 13,111 | 13,387 |

| City University | 1,927 | 1,942 | 1,946 | 1,946 | 1,946 |

| Police | 15,858 | 15,407 | 15,607 | 15,606 | 15,606 |

| Fire | 6,228 | 6,291 | 6,316 | 6,315 | 6,315 |

| Correction | 2,195 | 2,273 | 2,273 | 2,273 | 2,273 |

| Sanitation | 2,268 | 2,302 | 2,302 | 2,302 | 2,302 |

| Admin. For Children’s Services | 7,157 | 7,016 | 7,450 | 7,664 | 7,664 |

| Social Services | 14,713 | 14,670 | 14,725 | 14,725 | 14,725 |

| Homeless Services | 2,613 | 2,577 | 2,577 | 2,577 | 2,577 |

| Health And Mental Hygiene | 5,726 | 5,466 | 5,520 | 5,520 | 5,520 |

| Finance | 2,230 | 2,198 | 2,263 | 2,263 | 2,263 |

| Transportation | 5,395 | 5,384 | 5,505 | 5,502 | 5,501 |

| Parks And Recreation | 4,401 | 4,292 | 4,335 | 4,332 | 4,332 |

| All Other Civilians | 31,864 | 32,177 | 32,104 | 32,169 | 32,147 |

| Subtotal | 114,846 | 114,353 | 115,367 | 116,305 | 116,558 |

| Total | 303,862 | 304,448 | 305,744 | 308,124 | 310,903 |

As shown in Table 16, FY 2018 year-end headcount shows a net increase of 31 as compared to the February 2018 Financial Plan, with more significant increases, of 1,042 in FY 2019, 2,220 in FY 2020, 2,470 in FY 2021 and 2,293 in FY 2022. The change in headcount in FY 2018 mainly reflects budgetary adjustments, while the increases in FY 2019 through FY 2022 are driven primarily by new staffing needs of ranging from 1,114 to 1,195.

Table 16. Full-time Headcount Plan-to-Plan Comparison

April 2018 Financial Plan vs. February 2018 Financial Plan

| FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | |

| Pedagogical | |||||

| Dept. of Education | 0 | 94 | 42 | 42 | 42 |

| City University | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | 0 | 94 | 42 | 42 | 42 |

| Uniformed | |||||

| Police | 160 | 164 | 169 | 169 | 169 |

| Fire | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Correction | 0 | 259 | 259 | 259 | 100 |

| Sanitation | 0 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| Subtotal | 160 | 446 | 451 | 451 | 292 |

| Civilian | |||||

| Dept. of Education | 12 | (37) | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| City University | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Police | (207) | (408) | (220) | (221) | (221) |

| Fire | (2) | 67 | 92 | 92 | 92 |

| Correction | 0 | 71 | 71 | 71 | 71 |

| Sanitation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Admin. for Children’s Services | 0 | 44 | 479 | 693 | 693 |

| Social Services | 0 | (44) | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Homeless Services | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Health and Mental Hygiene | 5 | (27) | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Finance | 0 | (44) | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Transportation | 37 | 179 | 303 | 303 | 302 |

| Parks and Recreation | 0 | (29) | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| All Other Civilians | 26 | 730 | 895 | 932 | 915 |

| Subtotal | (129) | 502 | 1,727 | 1,977 | 1,959 |

| Total | 31 | 1,042 | 2,220 | 2,470 | 2,293 |

Table 17 compares actual headcount on March 31, 2018 to the planned FY 2018 year-end headcount. The current headcount plan shows an expected net increase of 8,407 full-time employees Citywide, from actual total headcount on June 30, 2017 of 295,455. As of March 31, 2017, three-quarters into the fiscal year, Citywide headcount has shown a net increase of only 2,532, a little over 30 percent of the planned increase. This pace of increase suggests that headcount may not meet its target for the current fiscal year.

Table 17. March 31, 2018 Headcount vs. Planned June 30, 2018 Headcount

| 6/30/2017 Actuals | 3/31/2018 Actuals | Change 6/30/2017 Actuals to 3/31/2018 Actuals | 6/30/2018 Executive 2019 Plan | Planned Change 6/30/2017 to 6/30/2018 | Percent of Planned Change Achieved | |

| Pedagogical | ||||||

| Dept. of Education | 118,671 | 119,654 | 983 | 119,613 | 942 | 104.35% |

| City University | 4,449 | 4,536 | 87 | 4,441 | (8) | (1,087.50%) |

| Subtotal | 123,120 | 124,190 | 1,070 | 124,054 | 934 | 114.56% |

| Uniformed | ||||||

| Police | 36,254 | 36,764 | 510 | 36,078 | (176) | (289.77%) |

| Fire | 11,090 | 11,067 | (23) | 10,914 | (176) | 13.07% |

| Correction | 10,862 | 10,873 | 11 | 10,427 | (435) | (2.53%) |

| Sanitation | 7,544 | 7,641 | 97 | 7,543 | (1) | (9,700.00%) |

| Subtotal | 65,750 | 66,345 | 595 | 64,962 | (788) | (75.51%) |

| Civilian | ||||||

| Dept. of Education | 12,528 | 12,735 | 207 | 12,271 | (257) | (80.54%) |

| City University | 1,904 | 1,860 | (44) | 1,927 | 23 | (191.30%) |

| Police | 14,802 | 14,999 | 197 | 15,858 | 1,056 | 18.66% |

| Fire | 6,289 | 6,074 | (215) | 6,228 | (61) | 352.46% |

| Correction | 1,729 | 1,772 | 43 | 2,195 | 466 | 9.23% |

| Sanitation | 2,137 | 2,115 | (22) | 2,268 | 131 | (16.79%) |

| Admin. for Children’s Services | 6,343 | 6,474 | 131 | 7,157 | 814 | 16.09% |

| Social Services | 13,244 | 12,929 | (315) | 14,713 | 1,469 | (21.44%) |

| Homeless Services | 2,341 | 2,369 | 28 | 2,613 | 272 | 10.29% |

| Health and Mental Hygiene | 5,176 | 5,443 | 267 | 5,726 | 550 | 48.55% |

| Finance | 1,931 | 1,910 | (21) | 2,230 | 299 | (7.02%) |

| Transportation | 4,773 | 4,852 | 79 | 5,395 | 622 | 12.70% |

| Parks and Recreation | 4,124 | 4,128 | 4 | 4,401 | 277 | 1.44% |

| All Other Civilians | 29,264 | 29,792 | 528 | 31,864 | 2,600 | 20.31% |

| Subtotal | 106,585 | 107,452 | 867 | 114,846 | 8,261 | 10.50% |

| Total | 295,455 | 297,987 | 2,532 | 303,862 | 8,407 | 30.12% |

Overtime (OT)

The FY 2019 Executive Budget includes $1.350 billion for overtime expenditures, almost 14 percent lower than the current FY 2018 overtime projection of $1.568 billion. While the Comptroller’s Office projects that overtime spending will be lower than FY 2018, the estimated decline is less than the City’s projection. The Comptroller’s Office estimates that FY 2019 overtime spending will total $1.503 billion, $153 million more than the City’s estimate, as shown in Table 18.

Table 18. Projected Overtime Spending, FY 2019

| ($ in millions) | City Planned Overtime FY 2019 | Comptroller’s Office Projected Overtime FY 2019 |

FY 2019 Risk |

| Uniformed | |||