Comments on New York City’s Fiscal Year 2020 Executive Budget

Executive Summary

The Mayor’s FY 2020 Executive Budget is $92.47 billion, an increase of $258 million from the February Preliminary Budget. City funds comprise $68.25 billion, up $340 million from the Preliminary Budget. Adjusted for prepayments and reserves, the FY 2020 budget is less than 1 percent larger than the FY 2019 modified budget.

After a relatively gloomy start to the year, the short-term economic outlook has brightened as risk factors have softened. Economic growth is expected to continue in both the U.S. and New York City in 2019 and for the remainder of the plan period, albeit at a slower pace than in 2018. In our forecast, New York City’s economy is expected to grow at a slightly faster pace than the nation as a whole. The biggest risk to continued economic growth currently is the continuing impasse in trade negotiations with China and the imposition of further tariffs.

Since the Mayor’s Preliminary FY 2020 Budget in February, the City has projected an additional $1.13 billion in resources in Fiscal Year 2019, including $618 million in revenues, $264 million in expense budget savings, and a further draw down of $250 million from the General Reserve. These resources were used to fund $785 million in new spending in FY 2019, and an addition of $347 million to the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), bringing it to $3.52 billion. The FY 2019 surplus will be used to prepay a portion of FY 2020 debt service.

The Executive Budget for the first time included what the Mayor referred to as a Program to Eliminate the Gap, or PEG, which totaled $916 million over FY 2019 and FY 2020, which together with the two prior rounds of Citywide Savings Program brings total combined savings for the two years to $2.55 billion. The Executive PEG does not differ significantly from prior rounds of the Citywide Savings Program, with debt service, re-estimates, and funding shifts accounting for the bulk of the savings.

The PEG is insufficient to pay for new spending needs in FY 2019 and FY 2020, which includes $369 million to offset the impact of measures in the enacted State budget, and another $1.4 billion in other new needs. A substantial share of the headcount reductions associated with the hiring freeze and other savings actions are offset by new needs, resulting in net headcount reduction of 121 positions in FY 2020 compared to the February Plan.

As of the Executive Budget, the BSA remains nearly $1.1 billion below the final FY 2018 surplus. Additional tax revenues, which we project will come in $679 million above the City’s estimate, should help bring the BSA closer to last year’s figure. The Comptroller’s forecast for tax revenues over the plan period are consistently higher in every major tax source, most notably the real property tax, yielding additional revenues of nearly $1 billion in FY 2020, rising to just below $1.8 billion in FY 2023.

Higher revenues in our projection are partially offset by expenditure risks, notably for overtime, charter school tuition, and the absence of baseline funding for the Fair Fares program. Taken together, our tax forecast and analysis of expenditure risks yields modest additional surpluses in FY 2019 and 2020, and smaller gaps in fiscal years 2021 through 2023.

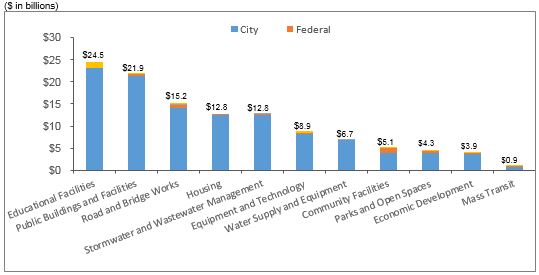

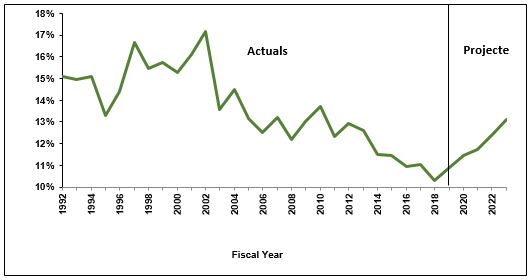

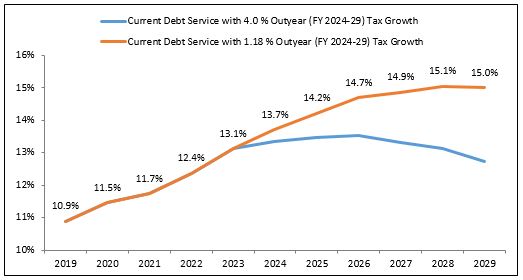

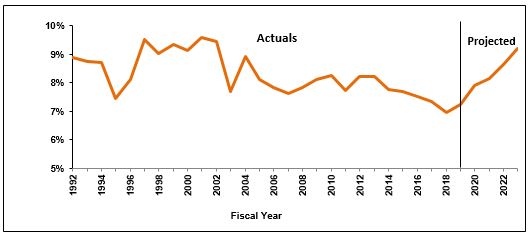

The City’s Ten-Year Capital Strategy, released with the Executive Budget, totals $116.9 billion, a 12.3 percent increase from the Preliminary Ten-Year Capital Strategy published in February. The increase included $8.0 billion for construction of borough-based jails to replace Rikers Island, for a total of $8.75 billion. Over half the total ($59.72 billion) is allocated to maintaining state of good repair in schools, other public buildings, roads and bridges, housing, parks, and other community facilities, with the balance divided between programmatic replacement ($29.67 billion) and program expansion ($27.5 billion). Borrowing to finance the capital program is expected to push debt service to 13.1 percent of tax revenues by FY2023, compared to 10.3 percent in FY 2018 (adjusted for debt service prepayments). This is still below the 15% threshold that is commonly used as a benchmark for affordability.

Table 1. FY 2019 – FY 2023 Financial Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | Change FYs 2019 –2023 Dollar Percent |

|

| Revenues | |||||||

| Taxes: | |||||||

| General Property Tax | $27,976 | $29,711 | $31,089 | $32,328 | $33,286 | $5,310 | 19.0% |

| Other Taxes | 31,849 | 32,415 | 33,211 | 34,180 | 35,113 | 3,264 | 10.2% |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 1,058 | 999 | 721 | 721 | 721 | (337) | (31.9%) |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $60,883 | $63,125 | $65,021 | $67,229 | $69,120 | $8,237 | 13.5% |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 8,065 | 6,955 | 6,911 | 6,884 | 6,879 | (1,186) | (14.7%) |

| Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid | 201 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (201) | (100.0%) |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (2,220) | (1,819) | (1,817) | (1,815) | (1,814) | 406 | (18.3%) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 91 | (15) | (15) | (15) | (15) | (106) | (116.5%) |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $67,020 | $68,246 | $70,100 | $72,283 | $74,170 | $7,150 | 10.7% |

| Other Categorical Grants | 1,207 | 928 | 870 | 863 | 863 | (344) | (28.5%) |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | 657 | 735 | 672 | 672 | 672 | 15 | 2.3% |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 8,494 | 7,226 | 7,069 | 6,998 | 6,966 | (1,528) | (18.0%) |

| State Categorical Grants | 15,473 | 15,333 | 15,719 | 16,186 | 16,693 | 1,220 | 7.9% |

| Total Revenues | $92,851 | $92,468 | $94,430 | $97,002 | $99,364 | $6,513 | 7.0% |

| Expenditures | |||||||

| Personal Service | |||||||

| Salaries and Wages | $29,051 | $29,978 | $30,905 | $30,757 | $31,645 | $2,594 | 8.9% |

| Pensions | 9,936 | 9,951 | 10,118 | 10,564 | 10,620 | 684 | 6.9% |

| Fringe Benefits | 10,642 | 11,394 | 11,853 | 12,527 | 13,228 | 2,586 | 24.3% |

| Subtotal-PS | $49,629 | $51,323 | $52,876 | $53,848 | $55,493 | $5,864 | 11.8% |

| Other Than Personal Service | |||||||

| Medical Assistance | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $0 | 0.0% |

| Public Assistance | 1,595 | 1,651 | 1,651 | 1,651 | 1,650 | 55 | 3.4% |

| All Other | 32,312 | 30,426 | 30,411 | 30,718 | 30,958 | (1,354) | (4.2%) |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $39,822 | $37,992 | $37,977 | $38,284 | $38,523 | ($1,299) | (3.3%) |

| Debt Service | |||||||

| Principal | $3,411 | $3,613 | $3,726 | $3,859 | $3,967 | $556 | 16.3% |

| Interest & Offsets | 3,219 | 3,625 | 3,899 | 4,456 | 5,103 | 1,884 | 58.5% |

| Subtotal Debt Service | $6,630 | $7,238 | $7,625 | $8,315 | $9,070 | $2,440 | 36.8% |

| FY 2018 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | (4,576) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,576 | (100.0%) |

| FY 2019 BSA | 3,516 | (3,516) | 0 | 0 | 0 | (3,516) | (100.0%) |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | 0 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | NA |

| General Reserve | 50 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 950 | 1,900.0% |

| Subtotal | $95,071 | $94,287 | $99,728 | $101,697 | $104,336 | $9,265 | 9.7% |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | (2,220) | (1,819) | (1,817) | (1,815) | (1,814) | 406 | (18.3%) |

| Total Expenditures | $92,851 | $92,468 | $97,911 | $99,882 | $102,522 | $9,671 | 10.4% |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $0 | ($3,481) | ($2,880) | ($3,158) | ($3,158) | NA |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 2. Plan-to-Plan Changes April 2019 Plan vs. February 2019 Plan

($ in millions) |

FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 |

| Revenues | |||||

| Taxes: | |||||

| General Property Tax | ($70) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Other Taxes | 271 | 208 | 253 | 299 | 225 |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $202 | $209 | $253 | $299 | $225 |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 432 | 156 | 139 | 137 | 144 |

| Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (66) | (25) | (21) | (21) | (22) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $618 | $340 | $371 | $415 | $347 |

| Other Categorical Grants | 9 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | (33) | 74 | 10 | 11 | 11 |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 23 | (101) | (136) | (135) | (154) |

| State Categorical Grants | 215 | (57) | (118) | (119) | 340 |

| Total Revenues | $832 | $258 | $129 | $173 | $545 |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Personal Service | |||||

| Salaries and Wages | $35 | ($262) | ($353) | ($358) | $3 |

| Pensions | 86 | 0 | (300) | (300) | (450) |

| Fringe Benefits | (1) | (142) | (175) | (178) | (157) |

| Subtotal-PS | $120 | ($404) | ($828) | ($836) | ($604) |

| Other Than Personal Service | |||||

| Medical Assistance | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Public Assistance | 0 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 33 |

| All Other | 788 | 1,107 | 942 | 959 | 1,016 |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $788 | $1,141 | $976 | $993 | $1,049 |

| Debt Service | |||||

| Principal | $0 | ($24) | $7 | $10 | $9 |

| Interest & Offsets | (107) | (83) | (40) | (32) | (25) |

| Subtotal Debt Service | ($107) | ($107) | ($33) | ($22) | ($16) |

| FY 2018 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FY 2019 BSA | 347 | (347) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General Reserve | (250) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | $898 | $283 | $115 | $135 | $429 |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | (66) | (25) | (21) | (21) | (22) |

| Total Expenditures | $832 | $258 | $94 | $114 | $407 |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $0 | $35 | $59 | $138 |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 3. Plan-to-Plan Changes April 2019 Plan vs. June 2018 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 |

| Revenues | ||||

| Taxes: | ||||

| General Property Tax | $2 | $234 | $198 | $448 |

| Other Taxes | 803 | 264 | 61 | 286 |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 2 | 278 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $807 | $776 | $259 | $734 |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 1,273 | 224 | 174 | 168 |

| Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid | 201 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (395) | (48) | (41) | (39) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 106 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $1,992 | $952 | $392 | $863 |

| Other Categorical Grants | 327 | 56 | 3 | 2 |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | (25) | 94 | 34 | 34 |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 902 | 97 | (39) | (94) |

| State Categorical Grants | 497 | 31 | (44) | (60) |

| Total Revenues | $3,693 | $1,230 | $346 | $745 |

| Expenditures | ||||

| Personal Service | ||||

| Salaries and Wages | $305 | $358 | $537 | $688 |

| Pensions | 84 | 48 | (44) | 197 |

| Fringe Benefits | (95) | (249) | (561) | (567) |

| Subtotal-PS | $294 | $157 | ($68) | $318 |

| Other Than Personal Service | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Medical Assistance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Assistance | (10) | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| All Other | 1,970 | 1,578 | 1,244 | 1,272 |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $1,960 | $1,612 | $1,278 | $1,306 |

| Debt Service | ||||

| Principal | ($18) | ($23) | $94 | $98 |

| Interest & Offsets | (339) | (212) | (325) | (343) |

| Subtotal Debt Service | ($357) | ($235) | ($231) | ($245) |

| FY 2018 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| FY 2019 BSA | $3,516 | ($3,516) | $0 | $0 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | ($250) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| General Reserve | ($1,075) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Subtotal | $4,088 | ($1,982) | $980 | $1,379 |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | (395) | (48) | (41) | (39) |

| Total Expenditures | $3,693 | ($2,030) | $939 | $1,340 |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $3,260 | ($593) | ($595) |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 4. Risks and Offsets to the April 2019 Financial Plan

($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap)

| FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | |

| City Stated Gap | $0 | $0 | ($3,481) | ($2,880) | ($3,158) |

| Tax Revenues | |||||

| Property Tax | $0 | $200 | $387 | $735 | $1,085 |

| Personal Income Tax | 496 | 385 | 387 | 335 | 237 |

| Business Taxes | 87 | 95 | 128 | 119 | 114 |

| Sales Tax | 65 | 114 | 103 | 34 | (35) |

| Real Estate Transaction Taxes | 31 | 202 | 321 | 299 | 241 |

| Audit | 0 | 0 | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| Subtotal Tax Revenues | $679 | $996 | $1,480 | $1,676 | $1,796 |

| Non-Tax Revenues | |||||

| ECB Fines | $0 | $10 | $10 | $15 | $15 |

| Late Filing/No Permit Penalties | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Other Fines | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Subtotal Non-Tax Revenues | $0 | $13 | $18 | $23 | $23 |

| Total Revenues | $679 | $1,009 | $1,498 | $1,699 | $1,819 |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Overtime | ($195) | ($140) | ($150) | ($150) | ($150) |

| Charter School Tuition | 0 | (0) | (117) | (250) | (399) |

| Fair Fares | 65 | (106) | (212) | (212) | (212) |

| Homeless Shelters | 0 | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) |

| DOE Medicaid Reimbursement | 0 | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) |

| VRDB Interest Savings | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General Reserve | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | ($50) | ($286) | ($519) | ($652) | ($801) |

| Total (Risks)/Offsets | $629 | $723 | $979 | $1,047 | $1,018 |

| Restated (Gap)/Surplus | $629 | $723 | ($2,502) | ($1,833) | ($2,140) |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

The City’s Economy Outlook

Comptroller’s Economic Forecast, 2019-2023

After a relatively gloomy start to the year, the short-term economic outlook has brightened as risk factors have softened. Economic growth is expected to continue in both the U.S. and New York City in 2019 and for the remainder of the plan period, albeit at a slower pace than in 2018. This growth comes as a result of strong employment demand, increasing wages, and monetary policy accommodative to economic growth. Growth is expected to slow as the economic cycle matures, although the risks of recession during the financial plan period have declined – if not to zero, at least compared to the picture in the beginning of the year, when various risks – trade disruptions, more restrictive monetary policy, and other factors – weighed on projections.

In our forecast, New York City’s economy is expected to grow at a slightly faster pace than the nation as a whole. Continued strength in the labor market and rising wages will fuel consumer spending.

Table 5. Selected Economic Indicators Comptroller’s and Mayor’s Forecasts

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||

| Selected US Economic Indicators (Annual Averages) | ||||||

| Real GDP (2009 $, % Change) | Comptroller

Mayor |

2.6

2.4 |

1.9

2.1 |

1.6

1.8 |

1.3

1.7 |

1.5

1.6 |

| Payroll Jobs (Change In Millions) | Comptroller

Mayor |

2.0

1.7 |

1.3

1.0 |

1.2

0.5 |

0.6

0.5 |

0.4

0.4 |

| Fed Funds Rate (Percent) | Comptroller

Mayor |

2.4

2.5 |

2.4

2.8 |

2.3

2.9 |

2.3

2.9 |

2.3

2.8 |

| Selected NYC Economic Indicators (Annual Averages) | ||||||

| Real GCP (2009 $, % Change) | Comptroller

Mayor |

2.8

3.0 |

2.1

1.7 |

1.9

1.1 |

1.5

0.9 |

1.2

0.4 |

| Payroll Jobs (Change In Thousands) | Comptroller

Mayor |

69.6

68.9 |

51.5

66.1 |

46.3

53.3 |

28.0

51.3 |

26.6

47.1 |

| Wage-Rate Growth (Percent) | Comptroller

Mayor |

3.6

3.0 |

2.7

2.6 |

2.5

2.5 |

1.8

2.6 |

1.7

2.2 |

Note: Comptroller=forecast by the NYC Comptroller’s Office. GCP=Gross City Product. Mayor= forecast by the NYC Office of Management and Budget in the Executive Budget Fiscal Year 2019 Message of the Mayor. NA=not available.

Factors Affecting the Forecast

The National Economy

The U.S. economy, as measured by real GDP, grew 3.2 percent in the first quarter of 2019 after growing 2.2 percent in the fourth quarter of 2018. This growth was driven primarily by a decline in imports, an increase in private investment (mostly in inventories), consumer spending, and government expenditure.

A strong labor market, modestly increasing wages, the low likelihood of an interest rate hike by the Federal Reserve, and the short term boost from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) suggests that economic growth will continue. As the unemployment rate falls and the labor force tightens, the Comptroller is forecasting growth at a slower pace than the 2.9 percent growth in 2018. If expansionary fiscal policy creates higher budget deficits and ultimately higher long-term interest rates, the growth will taper off. We are projecting economic growth will begin to taper off in the later years of the Financial Plan period but fall short of an actual recession.

Net exports contributed the most to GDP growth in the first quarter of 2019, 1.03 percentage points (pp), mainly because of a 3.7 percent decline in imports. The decline in imports can be attributed to the imposition of tariffs. At the same time, U.S. exports increased despite fears of retaliatory tariffs by our trading partners, as well as an improvement in the economies of our trading partners in the first quarter. The strengthening U.S. dollar as a result of higher U.S. interest rates than in other large nations, however, could ultimately be a drag on future U.S. exports.

Private investment rose 5.1 percent and contributed 0.92 pp to GDP growth in the first quarter. The bulk of this rise was a change in private inventories which was responsible for 0.65 pp of GDP growth. Inventories may grow either because producers expect final demand to grow, which would sustain and extend growth, or because producers produced more goods than the market can absorb, which could result in a slowdown in future production as inventories are absorbed. Time will tell which market condition is being signaled by this component of GDP.

The surprise in the latest GDP report was the weakness in consumer spending, which grew only 1.2 percent and contributed 0.82 pp to the GDP growth. Three indicators, however – continuing job growth, rising wages, and lower tax rates – lead us to expect that this sector is poised to contribute more toward growth throughout 2019. With American household balance sheets strong and debt burdens generally manageable, consumer spending should return to help keep the expansion going.

Government expenditures rose 2.4 percent mainly because of defense spending, which grew 4.1 percent. Non-defense federal spending continued its decline, falling 5.9 percent after declining 6.1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2018. State and local government expenditures rose 3.9 percent in first-quarter 2019 after falling 1.3 percent in fourth-quarter 2018.

Wages, as measured by average hourly earnings, rose 3.3 percent in the first quarter of 2019, the highest first quarter increase since 2009. Jobs in the U.S. grew at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 1.7 percent for the second consecutive quarter in the first quarter of 2019. The unemployment rate rose slightly to 3.9 percent in the first quarter of 2019 from 3.8 percent in the previous quarter. In the latest release, the unemployment rate for April has dropped to a 50 year low at 3.6 percent.

Despite continuing robust job growth and rising wages, inflation remains below the Federal Reserve’s policy target of 2 percent. The Fed’s preferred measure, the personal consumption expenditure deflator, was 0.6 percent in the first quarter of 2019, the lowest rate in three years.

Recent reports of rising labor productivity are positive news for the inflation outlook The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee has decided to keep the Fed Funds rate unchanged in 2019. Fears of an inverted yield curve as a harbinger of recession are overblown.

On the global front, according to the IMF, global economic growth is expected to continue but at slower pace – down from 3.6 percent in 2018 to 3.3 percent in 2019.[1]

Low probability risks to the economy in the short-run include a curtailment in consumer demand as a result of excess debt fueled by years of cheap money; a commencement of a trade war with Europe; and a drop in the dollar precipitated by the Federal Reserve losing credibility as independent of the Federal government. In the longer term, the risk that the TCJA could result in a higher spending deficit without the promised higher growth is a threat for the outyears.

A higher probability risk would include a continuing impasse in trade negotiations with China and the imposition of further tariffs. Although the U.S. economy’s exposure to trade with China is limited, a prolonged confrontation could ultimately turn into a more significant drag on the economy.

While the economy is expected to grow for the duration of this budget plan, the pace of growth is expected to be less than it was in 2018. In general, the Comptroller’s Office outlook for the US economy is slightly more optimistic than that of OMB for 2019, and slightly more pessimistic in 2020 through 2023. We expect the economy to slow in 2022, but start accelerating in 2023.

The New York City Economy

The City’s economy continued to grow strongly in the first quarter of 2019 and it is expected to continue to do so for the remainder of the year. The City’s relatively strong economic fundamentals and the national fiscal stimulus, especially corporate tax cuts enacted in December of 2017, should fuel the City’s economic growth over the planning horizon.

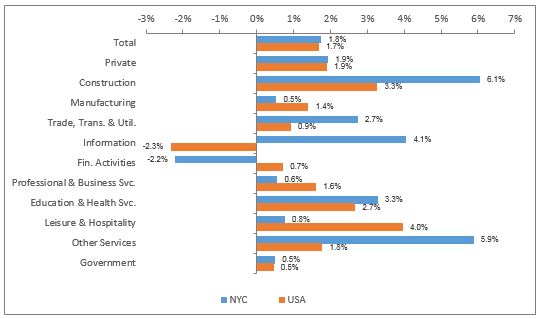

The City’s economy grew 3.0 percent in the first quarter of 2019, less than the 3.2 percent in the nation and the 3.5 percent in the previous quarter. Private-sector job growth slowed, adding 19,200 jobs, or 1.9 percent in the first quarter of 2019, about three-quarters of the 26,200 jobs created in the fourth quarter of 2018. This is comparable to the nation where private sector jobs grew 1.9 percent in the first quarter of 2019, slower than the 2.1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2018 (Chart 1).

Chart 1. Jobs Growth (SAAR) in NYC and the Nation First-Quarter 2019

over Fourth-Quarter 2018

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and NYS Department of Labor.

A softer job market led to a slightly higher unemployment rate. NYC’s unemployment rate, adjusted for seasonality, rose to 4.2 percent in first-quarter 2019 from 4.0 percent in the fourth quarter of 2018. The rise in the City’s unemployment rate was due to an increase in the number of unemployed and a decrease in the City’s labor force. The number of unemployed City residents increased for the second consecutive quarter, increasing by 8,800 in first-quarter 2019. The City’s labor force declined by 1,100 in the first quarter of 2019, although the City’s labor force participation rate remained unchanged from the last quarter’s record high of 60.9 percent.

The number of employed City residents fell by 9,900 in first-quarter 2019. As a result, the City’s employment-to-population ratio fell slightly to 58.3 percent in first-quarter 2019 from 58.4 percent in the previous quarter.

Average hourly earnings (AHE) of all private NYC employees, a component of personal income, rose 4.4 percent on a year-over-year basis to $37.42 in the first quarter of 2019, the highest first-quarter increase since a 9.1 percent rise in 2008. This coincides with an increase in the minimum wage to $15 per hour in 2018 for employers with more than ten employees and an increase to $13.50 for employers with ten or fewer employees, which amounts to a 15.4 percent and a 12.5 percent raise, respectively.[2]

A relatively strong labor market, an increase in earnings, and a strong national economy are expected to lift consumer spending in the City. We also expect that any increase in private investment in the nation will flow through to New York City given that the City is still the nation’s leading financial center. As such, fiscal and monetary policies impacting the financial sector directly impact the City’s economy. This is evident in first-quarter 2019 banks’ earnings report, which most likely helped the City’s first-quarter 2019 economic growth. America’s six largest banks – four of which are headquarter in the City – reported record profits and attributed it to the lower corporate income tax rate.[3]. Net income after taxes rose to a record high of $31.8 billion in the first quarter of 2019, 2.8 percent higher than a year ago. Wall Street profits, as measured by the pre-tax net income of the NYSE member firms, rose 11.3 percent to $27.3 billion in 2018, the highest level since 2010. In addition to lower taxes, banks’ profits could further have increased due to deregulation.[4] Both bank earnings and Wall Street profits are expected to continue increasing in 2019.

Wall Street bonuses play an outsized role in the City’s wages and salaries and personal income. Wall Street bonuses decreased 14.3 percent to $27.5 billion in 2018 from $32.1 billion in 2017 according to the NYS Comptroller.[5] This implies a reduction in the average cash bonus from about $184,000 in 2017 to about $154,000 in 2018, but it still was double the average annual salary in the City’s workforce.[6] Bonuses are expected to bounce back in 2019.

The strong business environment is also reflected in venture capital investment. According to PwC Money Tree, venture capital investment in the New York metro area rose 64.9 percent on a year-over-year basis to $4.5 billion in the first quarter of 2019, its highest first-quarter level on record.[7]

Finally, the City’s latest leading economic indicators signal continued positive growth. A survey of business conditions among firms in the New York City area is provided by ISM-New York, Inc. Both the current business condition index (which measures the current state of the economy from the perspective of business procurement professionals) and the ISM six-month outlook (which measures where procurement professionals expect the economy to be in six months) were above 50 percent, indicating the expectation of continued expansion. Also, the NY-BCI (which measures the cumulative change in business activity) rose to a record high of 861.6 in the first quarter of 2019 from 840.4 in the fourth quarter of 2018. According to the NYS Department of Labor, initial unemployment claims, which shows the number of applicants for unemployment insurance, declined for the fifth consecutive quarter to its lowest first quarter level on record in the first quarter of 2019. Also, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the total number of building permits in the City surged 22.4 percent from a year ago to 6,329, the highest first-quarter level since 2007.

The FY 2020 Executive Budget

Overview: Changes to FY 2019 and FY 2020

FY 2019 Budget

The FY 2019 Budget in the April Plan totals $92.85 billion, an increase of $832 million from the February Plan, driven primarily by increases in the City-funds and State-funds portion of the budget.[8] The State-funds portion of the budget has increase by $215 million, of which $56 million are reimbursements for prior-year claims for which there are no corresponding receivables. As such, these grants will be used to offset City-funds expenditures, $42 million of which are credited as savings in the current round of the Citywide Savings Program (CSP). Of the remaining $159 million increase, $74 million is due to an upward revision to the State early intervention service grant, a nearly 70 percent increase.

About a third of the increase to City-funds revenues are due to revisions to the tax revenue forecast, as shown in Table 6, driven primarily by an increase of $284 million in personal income tax (PIT) revenues. Tax revenues are discussed in greater detail in “Tax Revenues” beginning on page 18. Upward revisions to non-tax revenues account for another $261 million of the increase to City-funds revenues of which more than half is due to the City’s $142 million share of restitution from Standard Chartered Bank’s settlement for processing transactions in violation of Iranian sanctions. Revenue initiatives in the current round of the CSP account for the remaining $156 million increase in City-funds revenue. The revenues ranged across various agencies and revenue categories including a $35 million surplus transfer from the Education Construction Fund to the Department of Education (DOE), $12 million in additional parking meter revenues in the Department of Finance from the 2018 implementation of a citywide parking meter rate increase, and $50 million in Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reimbursements for prior year costs.

Table 6. Changes to FY 2019 City-Funds Estimates from the Preliminary Budget

($ in millions)

| revenues | expenditures | ||

| Property Tax Revenues | ($70) | Agency Expenses | $682 |

| Personal Income Tax Revenues | 284 | Miscellaneous Budget | 13 |

| Business Tax Revenues | 19 | Pensions | 86 |

| Sales Tax | 18 | General Reserve | (250) |

| Real Estate Transaction Tax | (54) | Collective Bargaining Adjustment | 4 |

| All Other Taxes | 4 | Citywide Savings Program | (264) |

| Subtotal | $201 | Subtotal | $271 |

| Non-Tax Revenues | 261 | BSA | |

| City Savings Program | 156 | 347 | |

| Total | $618 | Total | $618 |

City-funds agency expenditures are almost $700 million higher than estimated in the February Plan. This increase is mitigated by a $250 million reduction in the General Reserve and spending reductions of $264 million in the CSP, resulting in a net increase in spending of $271 million before accounting for changes in the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), as shown in Table 6 above. The largest increase in agency spending is a $203 million increase in payments to parents of special needs children who are eligible for reimbursements for placing these children in non-public schools (Carter Cases). Another $148 million increase is due to the enacted State budget’s 10 percent cut in reimbursement rate for Temporary Assistance to Need Families (TANF) and a shortfall in anticipated TANF funding for Tier II homeless shelters. The City has added $62.7 million in City-funds spending to make up for the cut in TANF reimbursement and $85.5 million in the Tier II homeless shelter budget to meet the shortfall in anticipate TANF funding.

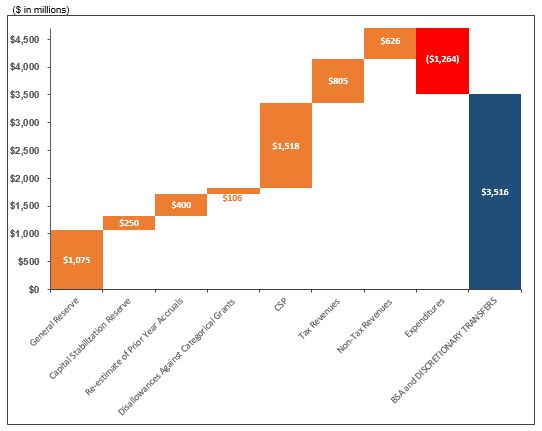

Overall, the $618 million increase in City-funds revenues, offset by the $271 million increase in City-funds expenditures, results in net additional resources of $347 million in FY 2019 to fund the BSA. The increase boosts the FY 2019 BSA to $3.5 billion. As Chart 2 shows, higher revenue forecasts and projected savings from the FY 2019 round of the Citywide Savings Program account for $2.95 billion of the BSA. The takedown of reserves and adjustments to prior-year accruals offset by a $1.26 billion increase in expenditures account for the remaining $563 million.

Chart 2. Funding the BSA and Discretionary Transfers

FY 2020 Budget

The FY 2020 Budget in the April Financial Plan totals $92.47 billion, an increase of $258 million from the February Plan. The increase is driven primarily by revisions to the City-funds portion of the budget which is $340 million higher than the February Plan. The non-City portion shows a net reduction of $82 million, primarily from a decline of $101 million in Federal categorical grants. Driving the reduction in Federal categorical grants is the ten percent cut in reimbursement rate for TANF in the enacted State budget, which reduces Federal categorical grants by $125 million and shifts this cost to the City.

As shown in Table 7, the increase in City-funds revenues in FY 2020 is due primarily to an upward revision of $209 million in tax revenues. With the exception of business tax revenues, which were revised downward by $118 million, all other tax revenue estimates were revised upward, with revisions to PIT accounting for $152 million of the increase. Tax revenues are discussed in greater detail in “Tax Revenues” beginning on page 18.

Table 7. Changes to FY 2020 City-Funds Estimates from the Preliminary Budget

($ in millions)

| revenues | expenditures | ||

| Personal Income Tax Revenues | $152 | Agency Expenses | $1,195 |

| Business Tax Revenues | (118) | Miscellaneous Budget | (12) |

| Sales Tax | 98 | Energy Adjustments | (17) |

| Real Estate Transaction | 70 | Lease Adjustments | (36) |

| All Other Tax | 7 | Collective Bargaining Adjustment | 7 |

| Subtotal | $209 | Citywide Savings Program | (449) |

| Subtotal | $687 | ||

| Non-Tax Revenues | 84 | ||

| Citywide Savings Program | 47 | BSA | (347) |

| Total | $340 | Total | $340 |

As discussed in “FY 2019 Budget” above, the FY 2019 BSA increased by $347 million resulting in an attendant reduction in FY 2020 debt service. Net of the prepayment of debt service out of the FY 2019 BSA, FY 2020 City-funds expenditures are $687 million above the Preliminary Budget estimates. The increase is driven by additional agency spending of $1.2 billion, with the impact of the enacted State budget accounting for $306 million of the increase. In addition to having to absorb the $125 million loss in TANF reimbursement, the City will have to fund a reduction in the State reimbursement for non-emergency public health spending and for election reform initiatives, as discussed in “Federal and State Aid” beginning on page 24. Similar to the revisions in FY 2019, the largest increase in the remaining agency spending revisions is for additional funding for Carter Cases. Overall, the largest increase in spending is in the Department of Education (DOE), whose FY 2020 budget is increased by $369 million, before accounting for reductions from the agency’s CSP savings.

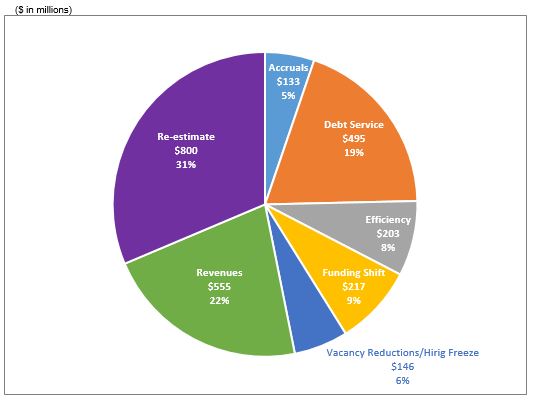

Citywide Savings Program (CSP)

The spending increases in the April 2019 Financial Plan are mitigated by another round of CSP that is expected to provide budget relief totaling $420 million in FY 2019, $497 million in FY 2020, $383 million in FY 2021, $360 million in FY 2022, and $356 million in FY 2023. With the current round of CSP, estimated budget relief over the Plan period now totals $5.17 billion. The combined savings in FY 2019 and FY 2020 is $2.55 billon. As Chart 3 shows, additional revenues from revenue initiatives, debt service and re-estimates together account for 73 percent of the savings. Three one-time revenue infusions into the general fund in FY 2019 account for about half the revenues in the CSP: 1) a $152 million reimbursement from Health + Hospitals (H+H) primarily for prior-year payments of debt service, 2) a $50 million FEMA reimbursement for prior-year administrative costs associated with Superstorm Sandy recovery, and 3) a $35 million surplus transfer from the Education Construction to the DOE. Efficiency initiatives account for 8 percent of the savings.[9]

Chart 3. Combined FY 2019 and FY 2020 Citywide Savings Program

Risks and Offsets

As Table 8 shows, the Comptroller’s Office analysis of the April Plan shows net additional resources ranging from $629 million to $1.05 billion, in each year of the Plan. The additional resources are driven by the Comptroller’s Office’s tax revenue forecast, which is higher than the City’s projections in each year of the Plan, beginning at $679 million in FY 2019 and growing to $1.80 billion by FY 2023. (See “Tax Revenues” beginning on page 18.)

Risks to the City’s expenditure estimates offset some of the gains from the higher revenue forecast. These risks stem primarily from assumptions of overtime spending and shortfalls in funding for charter school tuition and the Fair Fares initiative. Despite increases to the overtime budget in the current Plan, the Plan’s assumptions are still significantly below recent spending patterns. The Comptroller’s Office’s analysis indicates that overtime could be above Plan by $195 million in FY 2019, $140 million in FY 2020, and $150 million in each of the outyears of the Plan.

Similarly, while the April 2019 Plan increased funding for charter school tuition by $88 million in each of the outyears of the Plan, residual risks ranging from $117 million in FY 2021 to $399 million in FY 2023 remain. The Comptroller’s Office’s risk of Fair Fares funding remains unchanged from February. The funding for the Fair Fares initiative remains at $106 million in FY 2020 with no funding in the outyears. Based on the City’s estimate of a full year cost of $212 million for the program, the funding level in the current Plan represents risks of $106 million in FY 2020 and $212 million in the outyears of the Plan.

Table 8. Risks and Offsets to the April 2019 Financial Plan

($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap)

| FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | |

| City Stated Gap | $0 | $0 | ($3,481) | ($2,880) | ($3,158) |

| Tax Revenues | |||||

| Property Tax | $0 | $200 | $387 | $735 | $1,085 |

| Personal Income Tax | 496 | 385 | 387 | 335 | 237 |

| Business Taxes | 87 | 95 | 128 | 119 | 114 |

| Sales Tax | 65 | 114 | 103 | 34 | (35) |

| Real Estate Transaction Taxes | 31 | 202 | 321 | 299 | 241 |

| Audit | 0 | 0 | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| Subtotal Tax Revenues | $679 | $996 | $1,480 | $1,676 | $1,796 |

| Non-Tax Revenues | |||||

| ECB Fines | $0 | $10 | $10 | $15 | $15 |

| Late Filing/No Permit Penalties | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Other Fines | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Subtotal Non-Tax Revenues | $0 | $13 | $18 | $23 | $23 |

| Total Revenues | $679 | $1,009 | $1,498 | $1,699 | $1,819 |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Overtime | ($195) | ($140) | ($150) | ($150) | ($150) |

| Charter School Tuition | 0 | (0) | (117) | (250) | (399) |

| Fair Fares | 65 | (106) | (212) | (212) | (212) |

| Homeless Shelters | 0 | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) |

| DOE Medicaid Reimbursement | 0 | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) |

| VRDB Interest Savings | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General Reserve | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | ($50) | ($286) | ($519) | ($652) | ($801) |

| Total (Risks)/Offsets | $629 | $723 | $979 | $1,047 | $1,018 |

| Restated (Gap)/Surplus | $629 | $723 | ($2,502) | ($1,833) | ($2,140) |

Overall, the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the Plan indicates that the City could end FY 2019 and FY 2020 with budget surpluses of $629 million and $723 million, respectively. In the outyears, the Comptroller’s Office analysis shows gaps of $2.50 billion, $1.83 billion and $2.14 billion in FY 2021 through FY 2023, respectively.

Revenue Analysis

Total revenues are estimated to grow by $6.51 billion over the forecast period, from $92.85 billion in FY 2019 to $99.36 billion in FY 2023. Estimated City fund revenues average 74 percent of total revenues over the Plan period. These projections reflect the City’s assumption of slower but continued growth in the local and national economies, which is on track to be the longest expansion in history.

Tax revenues are projected to grow by 3.0 percent in FY 2019 to $60.88 billion, following last year’s growth of 8.1 percent. Last year’s growth reflected a one-time boost related to Federal tax reform which contributed to a 19 percent increase in Personal Income Tax (PIT) revenue in FY 2018 that is not expected to recur. Over the forecast period, tax revenue growth is forecast to average 3.2 percent annually. This result is driven by a 4.4 percent average annual growth in property tax revenues and a slower 2.2 percent average annual growth in non-property tax revenues.

Miscellaneous revenue is projected to decline from $5.85 billion in FY 2019 to $5.14 billion in FY 2020. The decline results from an expected drop in one-time revenues. Beginning in FY 2020, non-recurring revenues such as asset sales and restitutions are projected to decline, reducing overall miscellaneous revenue projections to an average of $5 billion annually over the Plan period.

The April Plan reflects $23.97 billion of Federal and State aid for FY 2019, representing nearly 26 percent of the City’s overall revenue projections. Over the outyears of the Plan, Federal and State grants are projected to decline to $22.56 billion in FY 2020 and gradually recover over the remainder of the Plan to reach $23.66 billion by FY 2023. Federal support is projected to fall from $8.49 billion in FY 2019 to a range of $6.97 billion – $7.23 billion in each of FY 2020 – 2023 mainly due to declining Sandy-related reimbursements and the inclusion of rollover Federal funds in FY 2019. Meanwhile, State aid is projected to grow from $15.47 billion in FY 2019 to $16.69 billion by FY 2023, driven primarily by the expectation of school aid increases.

Tax Revenues

Revisions since the February Financial Plan, FY 2019 – FY 2023

In the April Plan, the City projects total tax revenues of $60.9 billion in FY 2019 and $63.1 billion in FY 2020, an increase of approximately $200 million over the February Plan. The outyears were also revised upwards, by slightly higher amounts: $253 million, $299 million and $225 million respectively in FY 2021 – FY 2023.

As Table 9 shows, the largest upward revisions in the April Plan were PIT and sales tax revenues. These changes reflect both higher than anticipated collections during the important April filing period as well as stronger assumptions for economic growth in the out years. Based on collection trends, real estate related taxes were revised downwards in FY 2019. The downward revision to real property taxes may be related to larger prepayments that occurred in FY 2018 to take advantage of the last year of full state and local tax (SALT) deductibility, which have may have subtracted from revenues this year. The outyear forecast for real estate transaction taxes, however, was revised upwards, while the pattern of revisions to business taxes is the opposite: higher near term strength followed by a lower forecast in the outer years.

Table 9. Revisions to the City’s Tax Revenue Assumptions April 2019 vs. February 2019

| ($ in millions) | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 |

| February 2019 Financial Plan | $60,681 | $62,916 | $64,768 | $66,930 | $68,895 |

| Revisions: | |||||

| Property | ($70) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Personal Income (PIT) | 284 | 152 | 120 | 122 | 87 |

| Business | 19 | (118) | (66) | (28) | (69) |

| Sales | 18 | 98 | 114 | 112 | 112 |

| Real Estate Transactions | (54) | 70 | 68 | 75 | 70 |

| All Other | 4 | 6 | 17 | 18 | 25 |

| Tax Audit | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | $202 | $209 | $253 | $299 | $225 |

| April 2019 Financial Plan | $60,883 | $63,125 | $65,021 | $67,229 | $69,120 |

Comptroller Projections, FYs 2019 – 2023

The Comptroller’s forecast anticipates revenue growth of 4.1 percent in the current fiscal year following last year’s tax law-influenced surge of 8.1 percent. While slowing, strong momentum in the local and national economies provides support for continued expansion and revenue growth across the Plan period. Overall tax revenue growth is expected to average 3.6 percent over the four year Plan period, a remarkable result given the length of the current expansion, and slightly higher than the City’s own projections for sustained growth of 3.2 percent. By the end of the Plan period, overall tax revenues could be almost $1.8 billion higher than City’s projection, as shown in Table 11. Property tax revenues account for most of the difference in the later years of the Plan. A more detailed discussion of our projections and differences from the City’s forecast follows.

Table 10. Tax Revenue Forecast, Growth Rates

| FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FYs 2019 – 23 Average Annual Growth | |

| Property | ||||||

| Mayor | 5.9% | 6.2% | 4.6% | 4.0% | 3.0% | 4.4% |

| Comptroller | 5.9% | 6.9% | 5.2% | 5.0% | 4.0% | 5.3% |

| PIT | ||||||

| Mayor | (4.9%) | 3.3% | 2.2% | 3.2% | 3.2% | 2.9% |

| Comptroller | (1.2%) | 2.3% | 2.1% | 2.7% | 2.4% | 2.4% |

| Business | ||||||

| Mayor | 6.3% | (1.8%) | 2.7% | 2.0% | 1.4% | 1.1% |

| Comptroller | 7.8% | (1.7%) | 3.2% | 1.8% | 1.3% | 1.2% |

| Sales | ||||||

| Mayor | 5.2% | 5.6% | 3.5% | 3.5% | 3.2% | 3.9% |

| Comptroller | 6.0% | 6.2% | 3.3% | 2.7% | 2.4% | 3.6% |

| Real Estate Transactions | ||||||

| Mayor | 5.5% | (4.9%) | 1.1% | 2.5% | 2.6% | 0.3% |

| Comptroller | 6.8% | 1.7% | 5.6% | 1.4% | 0.3% | 2.2% |

| All Other | ||||||

| Mayor | 12.5% | (1.9%) | 1.5% | 2.2% | 2.1% | 0.9% |

| Comptroller | 12.5% | (1.9%) | 1.5% | 2.2% | 2.1% | 0.9% |

| Audit | ||||||

| Mayor | (20.9%) | (5.6%) | (27.8%) | 0.0% | 0.0% | (9.1%) |

| Comptroller | (20.9%) | (5.6%) | (12.4%) | 0.0% | 0.0% | (4.6%) |

| Total Tax with Audit | ||||||

| Mayor | 3.0% | 3.7% | 3.0% | 3.4% | 2.8% | 3.2% |

| Comptroller | 4.1% | 4.2% | 3.7% | 3.6% | 2.9% | 3.6% |

Table 11. Risks and Offsets to the City’s Tax Revenue Projections

| ($ in millions) | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 |

| Property | $0 | $200 | $387 | $735 | $1,085 |

| PIT | 496 | 385 | 387 | 335 | 237 |

| Business | 87 | 95 | 128 | 119 | 114 |

| Sales | 65 | 114 | 103 | 34 | (35) |

| Real Estate Transaction | 31 | 202 | 321 | 299 | 241 |

| Audit | 0 | 0 | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| Total | $679 | $995 | $1,480 | $1,676 | $1,796 |

Property Taxes

The forecast for the City’s largest revenue source shows slowing but continued growth throughout the Plan period. Property tax revenue is estimated to grow on average by 5.3 percent annually from FY 2020 to FY 2023. This compares to recent growth of 7.0 percent in FY 2018, 5.9 percent in FY 2019, and 6.9 percent in FY 2020, based on the tentative roll released in January 2019.

The slowdown is attributable to a complex mix of changes in forecast increases in assessed values, the phase-in of assessed value increases that have already occurred, and conservative estimates for the construction of new commercial and residential property going forward.

Conditions in the commercial office market are also somewhat mixed. Class A rents have recently experienced an uptick following last year’s small decline. The increase is largely due to a favorable mix of higher quality new space being leased, however, rather than a reflection of significant strength in underlying demand. The Class A vacancy rate remains near 10 percent and new speculative inventory coming on line in Hudson Yards could put further upward pressure on office vacancies. In addition, conditions is the retail market continues to exhibit weakness.

The City projects even slower growth for the real property tax. Part of the difference is due to the Comptroller’s Office predicting a smaller decrease in billable values from the tentative to final roll, which starts our forecast from a higher baseline. The other difference is the forecast for reserves.[10] The City’s projections show reserves jumping to almost 7 percent of the levy in FY 2020 – FY 2023 from 6.1 percent last year. Assuming a more steady reserve-to-levy ratio results in a forecast for reserves that is likely to be $200 million to$300 million lower than the City’s estimate. The combined effect of lower reserves and slightly higher assumptions on property tax growth results in property tax revenue exceeding the City’s projections by $1.1 billion by the end of the Plan period.

Real Estate Transaction Taxes

Year to date collection data indicate that the City’s real estate transfer taxes have rebounded from last year’s 3.8 decline, and for the year as a whole are estimated to grow by 6.8 percent. While the outlook for the commercial and residential market remains somewhat soft due to increasing high inventory, the concern that higher interest rates would also impact transactions and refinancings has largely subsided, given the Federal Reserve’s recent more dovish stance. As a result of the more favorable interest outlook and projections of stronger economic growth, our forecast for real estate transaction revenues is for moderate growth of 2.2 percent on average over the Plan period. This is somewhat higher compared to the City’s forecast of essentially flat growth over the same period.

One potential risk to the forecast is the recently enacted increases in the State’s real property transfer tax for commercial and residential properties. While the City’s tax rate remains unchanged, if transactions were to be significantly impacted as a result of these increases, revenues could be lower than anticipated. There is still considerable ongoing debate on the extent to which sales of high end luxury properties will be impacted by these changes.

Personal Income Taxes

April’s PIT collections came in significantly higher than anticipated in February. This suggests that the decline in estimated payments in December and January was an anomaly rather than a reflection of underlying weakness in PIT. The strength was particularly evident in extension payments which surged by more than 70 percent over the previous year. Even with strong April results, year to date personal income tax revenues are still 1.3% lower than last year, mainly due to an 18% decline in estimated payments. This decline is an indication that last year’s surge in PIT was due at least partly to one-time factors related to Federal tax law changes. However these non-recurring factors were either less pronounced than expected or underlying economic growth has offset these to a greater extent than anticipated. In support of the latter explanation, recent U.S. and local economic data continues to show growth that has largely exceeded expectations.

The current momentum in PIT collections is expected to carry forward through the remainder of the current fiscal year. Overall PIT revenue is expected to be only slightly lower than last year’s exceptional result. Looking ahead, as the one time effects of tax law changes dissipate, PIT is forecast to resume a more stable trajectory in FY 2020 – FY 2023 that is consistent with the forecast for local wages and employment. The Comptroller’s forecast for PIT is significantly higher than the City’s across the Plan Period. This is mainly due to a higher starting point, almost $500 million higher than the City’s forecast for the current fiscal year. The higher starting point reflects current collections data including the final tally for the April tax filing period which was not yet available when the City released the Plan.

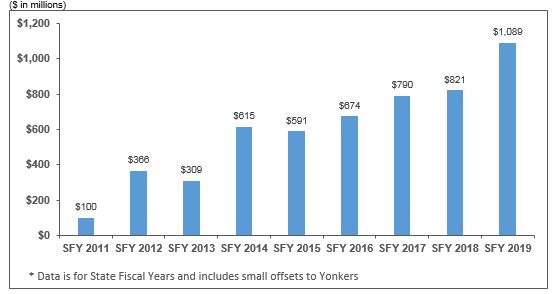

One noteworthy factor in collection trends are PIT offset payments from the State, which reconcile estimated payments with final payments. These continue to grow at a faster rate than overall PIT and are estimated to reach over $1 billion in the current State fiscal year, as shown in Chart 4. The ten-fold increase in offsets since FY 2011 has far outpaced any other component of income taxes. As we have suggested in prior reports, the formula used to distribute payments needs to be updated and be made more transparent so that the City receives PIT revenues in a timelier manner.

Chart 4. Offset Payments from the State

Business Income Taxes

March and April collections for the two main sources of business tax collections — the General Corporation Tax (GCT) and the Unincorporated Business Tax (UBT) — diverged. This was expected given that tax law changes provided GCT and UBT filers different timing incentives to shift income across tax years 2017-2019. The law also created incentives for UBT filers to incorporate, which may also explain why GCT collections through April were 17 percent higher compared to a year ago. In contrast, UBT revenue was 12 percent lower than the prior year.[11]

This year’s large uptick in GCT is expected to reverse in FY 2020, resulting in a five percent decline next year, and then resume moderate growth in the outyears. Compared to the City’s forecast, the Comptroller anticipates higher GCT revenue throughout the Plan period. Similar to PIT, the higher GCT forecast is due in large part to a higher starting point this year based on collections in the current year.

Sales Tax

A strong labor market, higher wages, and a robust tourism sector have continued to support growth in sales tax revenues. Collections from sales tax are up 5 percent in the first three quarters of FY 2019 compared to the same period last year. After registering 6.1 percent growth in FY 2018, the April Plan assumes sales tax revenue growth of 5.2 percent in FY 2019 to $7.83 billion. This projection is net of the final $150 million in payments to the State related to the City’s refinancing of STARC bonds. Sales tax revenue growth in FY 2020 is expected to accelerate slightly to 5.6 percent. Part of this growth reflects the end of the State mandated STARC intercepts, which have reduced City sales tax revenue by a combined $600 million in FY 2016 – FY 2019. The Plan assumes average growth in sales tax revenues will slow to 3.4 percent annually in FY 2021 – FY 2023.

The Comptroller’s Office expects higher wages and steady economic growth will support sales tax revenue growth of 6.0 percent in FY 2019 and 6.2 percent in FY 2020, compared to OMB’s growth estimates of 5.2 percent and 5.6 percent, respectively. These projections result in offsets of $65 million in FY 2019 and $114 million in FY 2020. In the outyears, both OMB and the Comptroller’s Office anticipate growth in sales tax collections to subside to a more modest pace, consistent with the underlying assumption of slower economic growth. The Comptroller’s Office projects sales tax revenue growth to average 2.8 percent annually in FY 2021 – FY 2023, compared to a 3.4 percent average reflected in the Plan over the same period. However, due to the Comptroller’s higher assumption for near-term growth, the Comptroller’s Office projects additional revenues of $103 million in FY 2021 and $34 million in FY 2022. However, in FY 2023 the Comptroller’s Office forecasts revenues from sales tax to be slightly below OMB’s projection, by about $35 million.

The New York State adopted budget for 2019 – 2020 included legislation requiring online marketplace providers to collect sales tax on sales of tangible goods to New York State residents regardless of vendor location. These new revenues will be intercepted by the State to fund MTA repair and upgrades. The City’s sales tax revenue intercepts will be $127.5 million in SFY 2019 – 2020, $170 million in SFY 2020 – 2021, and will increase one percent annually in SFY 2021 – 2022 and beyond. Sales tax revenue projections included in the April Plan are net of these amounts.

Audit Revenues

The City’s forecast shows audit revenue dropping significantly from over $1 billion in FY 2019 to below $800 million for the remainder of the Plan. While recognizing the volatility of single revenue sources within audit revenue, overall audit revenue has consistently hovered in the $1 billion range in recent years. We anticipate that audit revenue could exceed the City projections by about $150 million in each year from FY 2021 – FY 2023.

PILOT Revenue

The City collects payments in lieu of real estate taxes (PILOTs) mainly from local development entities that would otherwise be exempt from paying local property taxes, such as the NYC Industrial Development Agency and the Battery Park City Authority. The City estimates that in FY 2020, it will collect just over $500 million from PILOTs. Thereafter the City projects that PILOTs will decline to $444 million. The underlying projections of some of the PILOT revenue sources such as those from the Hudson Yards development area show real property taxes flat in the out-years. This seems unlikely given existing growth in this market and that new development will likely come on line. As such, combined PILOT revenue from all sources could be higher than the City’s estimates by $50 million to $100 million in FY 2020 to FY 2023.

Miscellaneous Revenues

In the April 2019 Financial Plan the City raised its FY 2019 miscellaneous revenue projection by a net $366 million, to $5.85 billion. Nearly $105 million of this increase are revenue initiatives included in the CSP. The revised FY 2019 miscellaneous revenue forecast is $877 million above the $4.97 billion realized last fiscal year. This is mostly due to higher revenue projections for “other miscellaneous,” including asset sales, restitution, and other non-recurring revenues in FY 2019. The current Plan also increases the FY 2020 miscellaneous revenue forecast by $131 million to $5.14 billion. This reflects a 12 percent decline in the miscellaneous revenue projection for the upcoming fiscal year.

Table 12 Changes in FY 2019 Estimates April 2019 vs. February 2019

| ($ in millions) | February | April | Change |

| Licenses, Franchises, Etc. | $728 | $795 | $67 |

| Interest Income | 193 | 213 | 20 |

| Charges for Services | 1,025 | 1,016 | (9) |

| Water and Sewer Charges | 1,464 | 1,453 | (11) |

| Rental Income | 259 | 272 | 13 |

| Fines and Forfeitures | 980 | 1,047 | 67 |

| Other Miscellaneous | 830 | 1,049 | 219 |

| Total | $5,479 | $5,845 | $366 |

*Water and sewer revenues collected by the Water Board from dedicated water and sewer charges represent reimbursements for operation and maintenance of the water delivery and sewer systems and therefore are not available for general operating purposes.

Table 12 shows the changes in the FY 2019 miscellaneous revenue projections since the February 2019 Plan. Except for small downward revisions to charges for services and water and sewer charges, the April Plan increased FY 2019 projections for all other categories of miscellaneous revenue. The largest revision, a $219 million increase in the category “other miscellaneous” reflects additional non-recurring revenues in FY 2019 including $141.7 million in restitution resulting from a settlement with Standard Chartered Bank for illegal transactions on behalf of sanctioned Iranian entities and individuals, $35 million in surplus transfer from the Educational Construction Fund, and $30 million in revenues associated with New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) management of City owned-properties and asset sales. Projected revenues from licenses, franchises and permits increased by $67 million mainly due to higher projected revenues from construction permits, taxi licenses and mobile telecom franchises. Re-estimates of overnight investments increased the forecast for interest income by $20 million. Projected rental income increased by $13 million as anticipated revenues from commercial rents increased. Estimated revenues from fines and forfeitures increased by $67 million, including additional revenues from parking fines ($40.8 million), Environmental Control Board (ECB) fines ($19 million), Department of Buildings (DOB) late filling/no permit penalties ($8 million), motor vehicle fines ($2 million), and Real Property Income and Expense (RPIE) late penalties ($2 million). These increases were partially offset by a $6.4 million reduction in projected revenues from speed camera fines.

After averaging $59 million over the past three fiscal years, revenues from speed camera fines are expected to drop to $45 million in FY 2019. In March, the State passed legislation to expand the City’s school zone speed camera program, which was signed by the Governor on May 12th. The new legislation expands the City’s speed enforcement program from 140 to 750 school zones. Hours of operation were also expanded to 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. instead of school hours. Currently, the City’s Department of Transportation (DOT) operates 195 fixed and 40 mobile cameras within 140 school zones. The program expansion to 750 school zones is expected to be phased in over three years. However, the April Plan reflects expense funding to cover just 300 additional cameras throughout the Plan period and assumes fine related revenues equal to the maintenance cost of 300 cameras. Revenues from speed camera fines are forecast to rise to $58 million in FY 2020 and then decrease by an average of 6.5 percent annually over the Plan period. Total projected fine revenues increased by $59 million in FY 2020 and by $44 million annually in FY 2021 – FY 2023. This revision reflects additional speed camera fine revenues as well as additional parking fines resulting from an expected increase in the alternate side parking fine amounts and a projected increase in NYPD traffic enforcement headcount and productivity.

Total miscellaneous revenues, excluding intra-City revenues, are projected to decline 12 percent in FY 2020 because of non-recurring revenues reflected in the current year, falling to around $5.1 billion and remaining at similar levels in FY’s 2021-2023.

Based on recent collection trends, the Comptroller’s Office expects revenues from fines to be above the City’s forecast by $13 million in FY 2020, $18 million in FY 2021, and $23 million in FY 2022 – FY 2023. These additional revenues result from the Comptroller’s Office slightly higher projections for Environmental Control Board (ECB) fines, and penalties from the Department of Buildings’ (DOB) and the Department of Finance (DOF).

Federal and State Aid

The FY 2020 Executive Budget assumes $22.56 billion in Federal and State assistance, reflecting a decline of $158 million since the February Plan. About 83 percent of this total is expected to support education and social services spending. On a year-over-year basis, the FY 2020 assumptions represent a decline of nearly $1.41 billion from projected Federal and State support in the current year, attributable mainly to the rapid decline in Sandy-related reimbursement and more conservative estimates of certain Federal grants in FY 2020.

Since the Preliminary Budget, the City’s Federal aid assumptions have fallen by $101 million. Net of Sandy-related funding, the City anticipates about $7.16 billion in Federal assistance for FY 2020. The majority of the Federal aid decline is reflected in social services, including TANF funding reduction enacted by the State ($125 million) and cash assistance and rental assistance re-estimates ($40 million). These changes are partly offset by additional school Medicaid revenue of $27 million and a net increase of $16 million in Community Development Block Grants and other areas. The City expects State aid to total $15.3 billion in FY 2020, a decrease of $57 million from projections in the Preliminary Plan. The decline mainly captures the impact on school aids and public health funding stemming from the enacted State budget.

State Budget Impact in the Executive Budget

Following adoption of the 2019 – 2020 State budget that began on April 1, the City estimates that actions in the State budget will increase City expenses in fiscal year 2020 by roughly $300 million, as shown in Table 13. Most significantly, under a provision in the adopted State budget, the City will now be required to fund 10 percent of the Family Assistance program, which provides cash assistance to needy families and is jointly funded by the Federal and State governments. The City estimates a loss of $125 million annually due to this new requirement.

Table 13 Impact of Adopted 2019 – 20 State Budget

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 |

| School Aid | ($25) |

| Cost Shifts | |

| Family Assistance | ($125) |

| Public Health | (59) |

| Subtotal, Cost Shifts | ($185) |

| Election Reforms | |

| Early Voting | ($75) |

| Electronic Poll Books | (21) |

| Subtotal, Election Reform | ($96) |

| Total Impact | ($306) |

The adopted State budget also included a reduction in State reimbursements for non-emergency public health spending, such as communicable disease control and chronic disease prevention, which will result in an estimated loss of $59 million in annual State aid.

Other proposals in the Governor’s Executive Budget that would have negatively impacted the City’s financial plan were avoided, including a mandate to steer additional funding to designated “under-funded” and “high-need” public schools. Instead, under the final State budget agreement, the City will be required to “prioritize” funding for such schools and submit a report to the State Education Department describing how funds are to be appropriated. Compared to OMB’s forecast, total State school aid for FY 2020 fell short by $25 million, far less than initially proposed.

Congestion Pricing and MTA Funding

The State budget also included a far-reaching plan to generate new revenue for the MTA, including authorization for a new fee to enter the central business district in Manhattan, a new “mansion” tax on property transactions in the City, and the dedication of a portion of new City and State sales tax revenue generated from internet purchases.

In late 2020, a newly created Traffic Mobility Review Board will recommend the congestion toll amount and structure, including any exemptions, discounts or credits, with a target to fund $15 billion in the MTA’s 2020-2024 capital plan. According to the enacted legislation, the bulk of the new revenue — 80 percent — will be allocated to “capital project costs of the New York City transit authority and its subsidiary, Staten Island Rapid Transit Operating Authority, and MTA Bus with priority given to the subway system, new signaling, new subway cars, track and car repair, accessibility, buses and bus system improvements and further investments in expanding transit availability to areas in the outer boroughs that have limited mass transit options.”[12] The remainder will be split between the Long Island Railroad and MetroNorth.

The MTA funding plan also imposes two supplemental taxes on residential and commercial property sales in New York City priced at $2 million and above. The first component is a 0.25 percent increase in the New York State real property transfer tax on residential sales priced at $3 million and above and commercial sales priced at $2 million and above. The second component is a supplemental “mansion” tax that begins at 0.25 percent for residential sales priced from at least $2 million to less than $3 million and tops out at 2.9 percent for residential sales priced at $25 million and above. The new rates take effect on July 1, 2019, and all additional revenue will be dedicated to the MTA. The State forecasts an additional $365 million per year for the MTA, although actual revenue collections in any given year are likely to fluctuate with swings in the luxury housing market. With the new tax, the combined City and State top transfer tax rate will increase from 2.825 percent for sales priced at $1 million and above to 5.975 percent for sales priced at $25 million and above. It is possible that the higher rates will result in a diminishment of sales relative to current expectations, and thus reduce the City’s own real property transfer tax revenues, and ultimately its real property tax.

Beginning in State fiscal year 2019 – 2020, the City is required to dedicate $127.5 million in sales taxes to the MTA, followed by $170 million in 2020 – 2021. These amounts are based on the State’s projection for new sales tax collections on online marketplace providers and out-of-state online retailers. Given the State’s lower sales tax rate — 4 percent vs 4.5 percent in the City — the State will contribute $112.5 million in 2019 – 2020 and $150 million in 2020 – 2021. In subsequent years, the required allocation will equal 101 percent of the preceding year amount. While the contribution amounts are based on new sales tax projections and a modest future growth rate, if the State’s revenue estimate proves too optimistic, the City could experience a revenue shortfall.

Early Voting

The City has also allocated $96 million in FY 2020 to comply with new early voting requirements adopted by the State earlier in the year — $75 million for early voting and $21 million for electronic poll books. Beginning with the November 2019 general election, the City Board of Elections (BOE) must provide nine extra days of voting for any general, primary, run-off primary election, or special election. Under the early voting law, local boards of election are generally expected to provide at least one early voting site for every fifty thousand registered voters. However, under the law, New York City does not have to provide more than 34 sites. While Mayor de Blasio recommended at least 100 sites to the BOE, and provided funding to do so, the BOE announced that it plans to operate only 38 sites.

According to the City’s estimates, operating roughly 100 early voting poll sites would cost $25 million per election. More than half of the cost would go to staffing and the remainder would fund expenses such as rental payments, ballot printing, equipment transportation, and security. In FY 2020 the City BOE will hold three elections – the general election (November 2019), the 2020 presidential primary, and a State/Federal primary in June 2020. While the City holds at least two elections every year, the City has not yet allocated any funding for early voting beyond FY 2020.

If the BOE operates only 38 early voting sites for all of FY 2020, the estimated cost would fall from $75 million to about $28.5 million. However, the BOE has indicated that it may increase the number of sites over time, and the City has pressed them to do so.

The adopted State budget further permits, but does not mandate, the use of electronic poll books. The use of electronic books will allow the BOE to more easily ensure that people vote only once following the implementation of early voting. In addition, each early voting site will require a full list of all voters in the county or early election zone. Without access to electronic poll books, each site would require a substantial amount of paper poll books.

The City may be able to access some State funding to offset these new election costs. The enacted State budget includes $10 million in local assistance funds to implement early voting Statewide and $14.7 million in capital appropriations for costs associated with electronic poll books hardware and software, as well as on-demand ballot printers and cyber security. The State Board of Elections will determine how to allocate these funds. The State’s package of election reforms also include a consolidation of Federal, State and local primaries, which will further reduce costs for the BOE.

Criminal Justice Reform

Sweeping reforms to the State criminal justice system will also have long-term impacts on the City’s financial plan. Beginning on January 1, 2020, cash bail will be eliminated for most people charged with a misdemeanor or non-violent felony. The State estimates that under the new law 90 percent of defendants will be released without bail. The new policy includes an expansion of release under non-monetary conditions, such as electronic monitoring, and directs judges to use the least restrictive conditions necessary to ensure a person’s return to court. If bail is set, the judge must consider the person’s financial circumstances and their ability to post bail without undue hardship. The adopted reforms also require prosecutors and defenders to abide by strict deadlines for sharing material intended to be used at trial and additional judicial oversight to enforce existing speedy trial requirements. Police officers will also be required to issue desk appearance tickets for most low-level crimes, rather than make an arrest.

Over time, the criminal justice reforms should result in a smaller jail population and enable the Department of Correction to reduce staffing costs. However, the City may incur additional costs in the short term for expanded pretrial services, such as electronic monitoring or supervised release. The State budget did not include any additional funding for such services.

School Speed Zone Cameras

Outside of the State budget, under State legislation that passed in March, the City may undergo a significant expansion of its school speed zone camera program. The program, which had lapsed in July 2018 until the Governor issued an Executive Order and the City Council passed legislation, was permitted to operate cameras in 140 school zones. The revised law increased the number of authorized zones to 750 and extended authorization through July 1, 2022, and is discussed in greater detail in “Miscellaneous Revenues” beginning on page 23.

Local Aid Cuts Possible if Revenues Fall

Another provision in the State budget could pose a risk to the City if State tax revenues fall short or if State expenses exceed expectations. The new provision will allow certain local aid payments to be uniformly reduced by up to 1 percent in the event of a “reasonably anticipated” $500 million imbalance in the general fund at the end of the year. Exempted aid categories include public assistance, debt service, and legal or federal obligations. The legislature would have 30 days to propose its own alternative plan. The adopted State budget also extends Executive authority to reduce spending if federal Medicaid revenues are cut by $850 million, or if non-Medicaid federal revenues are cut by $850 million in State fiscal years 2020 and 2021. The Legislature would have 90 days to propose and adopt an alternative plan.

Over the remainder of the Plan, Federal and State grants are projected to range between $22.79 billion in FY 2021 and $23.66 billion in FY 2023. These projections represent average annual growth of about 1.6 percent from the FY 2020 projections, driven primarily by the City’s expectation of State education aid increases averaging more than 3.7 percent annually. Assuming these assumptions hold, the level of Federal and State support for the City’s expense budget would decline from 24.4 percent in FY 2020 to about 23 percent by FY 2023.

Expenditures Analysis

Total-funds FY 2020 expenditures in the April Financial Plan are projected to remain relatively unchanged from FY 2019, declining by a modest $383 million, or less than half a percent. However, both the FY 2019 and FY 2020 expenditures include prepayments which lower debt service expenditures in these fiscal years. In addition, expenditures in FY 2019 are further reduced by the take-down of the general reserve and the re-estimates of prior-year accruals. After adjusting for prepayments, and excluding re-estimates of prior-year accruals and reserves, expenditures are projected to grow from $94.26 billion in FY 2019 to $94.73 billion in 2020, a modest growth of 0.5 percent, as shown in Table 14.

Over the Plan period, expenditures net of reserves and prior-year re-estimates are projected to grow by 7.4 percent, driven by spending on salaries and wages, debt service, health insurance, and other fringe benefits excluding pensions. The combined spending in these areas is projected to grow by 16.7 percent over the Plan period, averaging 3.9 percent annually. All other expenditures, net of the reserves and prior-year re-estimates, are projected to decline by 1.3 percent over the same period, with a projected annual average decline of 0.3 percent.

Table 14. FY 2019 – FY 2023 Expenditure Growth Adjusted for Prepayments and Prior-Year Actions

| ($ in millions) | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | Growth FYs 19-23 | Annual Growth |

| Salaries and Wages | $28,623 | $29,570 | $30,501 | $30,355 | $31,244 | 9.2% | 2.2% |

| Debt Service | $6,631 | 7,238 | 7,625 | 8,315 | 9,070 | 36.8% | 8.1% |

| Health Insurance | $6,487 | 7,086 | 7,455 | 8,013 | 8,593 | 32.5% | 7.3% |

| Other Fringe Benefits | $4,053 | 4,200 | 4,286 | 4,401 | 4,523 | 11.6% | 2.8% |

| Subtotal | $45,794 | $48,094 | $49,867 | $51,085 | $53,430 | 16.7% | 3.9% |

| Pensions | $9,824 | $9,839 | $10,006 | $10,452 | $10,507 | 7.0% | 1.7% |

| Medicaid | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Public Assistance | $1,595 | $1,651 | $1,651 | $1,651 | $1,650 | 3.5% | 0.9% |

| J & C | $697 | $712 | $727 | $742 | $758 | 8.8% | 2.1% |

| Contractual Services | $17,962 | $16,669 | $16,590 | $16,660 | $16,703 | (7.0%) | (1.8%) |

| Other OTPS | $12,474 | $11,855 | $11,906 | $12,128 | $12,309 | (1.3%) | (0.3%) |

| Subtotal | $48,467 | $46,641 | $46,794 | $47,547 | $47,842 | (1.3%) | (0.3%) |

| Expenditures Before Reserves and Prior-Year Re-estimates | $94,261 | $94,734 | $96,661 | $98,632 | $101,272 | 7.4% | 1.8% |

| Prior-Year Accruals Re-estimate | ($400) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | ||

| General Reserve | $50 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | ||

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | $250 | $250 | $250 | $250 | ||

| Total | $93,911 | $95,984 | $97,911 | $99,882 | $102,522 | 9.2% | 2.2% |

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

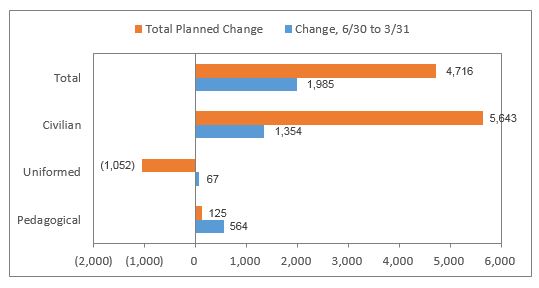

Headcount: Hiring Freeze Offset by New Needs

Full-time headcount, as shown in Table 15, is projected to increase from 305,071 in FY 2019 to 310,302 in FY 2022 before declining to 310,248 in FY 2023. The increase is primarily in pedagogical headcount which is projected to grow from 125,138 in FY 2019 to 130,919 in FY 2023. Uniformed headcount shows a net decline of 555 over this period while civilian headcount is projected to remain relatively flat with a modest reduction of 49.

Table 15. Total Funded Full-Time Year-End Headcount Projections April 2019 Financial Plan

| FY 2019 | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | |

| Pedagogical | |||||

| Dept. of Education | 120,697 | 121,771 | 123,735 | 126,478 | 126,478 |

| City University | 4,441 | 4,441 | 4,441 | 4,441 | 4,441 |

| Subtotal | 125,138 | 126,212 | 128,176 | 130,919 | 130,919 |

| Uniformed | |||||

| Police | 36,113 | 36,113 | 36,113 | 36,113 | 36,113 |

| Fire | 10,951 | 10,952 | 10,951 | 10,951 | 10,951 |

| Correction | 10,226 | 9,854 | 9,854 | 9,695 | 9,695 |

| Sanitation | 7,823 | 7,799 | 7,799 | 7,799 | 7,799 |

| Subtotal | 65,113 | 64,718 | 64,717 | 64,558 | 64,558 |

| Civilian | |||||