Comments on New York City’s Fiscal Year 2021 Executive Budget

Executive Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic which began in Wuhan, China in late December of 2019 quickly grew into a global pandemic with more than 4 million infections across more than 200 countries. As governments across the world imposed business and government closures and social distancing measures to combat the pandemic, the national economy which began the year fairly strong given the late stage of the business cycle quickly turned sharply negative. Lockdowns in the U.S., which began in mid-March, led GDP to fall at a 4.8 percent annual rate in the first quarter of 2020. The Comptroller is forecasting GDP to fall by 4.6 percent in 2020, with a 27 percent drop in output in the second quarter (seasonally adjusted annual rate) followed by positive growth in the second half of the year

The outlook for the City’s economy is somewhat more uncertain than the nation’s due to its greater dependence on both vacation visitors and business travelers, and its population density. While the Comptroller’s Office expects that both national and local economic activity will begin to recover in 2020 Q3, the City’s recovery will be slower given the devastating impact the pandemic has had on the City. The City’s unique characteristics, in terms of its density and reliance on mass transit, will also make for a more challenging recovery in the City and a more staggered re-opening. While most sectors of the City’s economy are expected to be almost fully recovered by the end of 2022, industries that interact more closely with the public, such as restaurants and bars will resume either more slowly, or in a different manner compared to the pre-COVID-19 world that could result in long-term reduced economic activity. The tourism and entertainment industries will likely see the slowest recovery due to their reliance on travelers.

State and local government budgets across the country have been ravaged by the crippling economic impact of the pandemic. The City is no exception and the FY 2021 Executive Budget and Financial Plan that was released on April 16 reflects the fiscal challenges confronting the City. Tax revenues over the current fiscal year and next are a combined $7.67 billion less than projected in the January 2020 Plan. Non-tax revenues are also lower, with revenues from licenses, permits and franchises; charges for services; and fines and forfeitures falling due to business slowdowns, lower demand for non-essential services and reduced enforcement. Interest income are projected to decline as well, as a result of emergency rate cuts by the Federal Reserve.

The FY 2020 Budget Modification in the Financial Plan totals $97.44 billion, an increase of $2.01 billion from the January Plan. The increase results primarily from about $2.55 billion of categorical grants to support COVID-19 related expenditures. However, tax revenues are $2.23 billion lower than projected in January, which in combination with lower non-tax revenues and revisions to spending estimates created a $2.56 billion shortfall in the budget. The Plan is relying on $1.55 billion in additional Federal support and the drawdown of $1.28 billion in reserves to bridge the shortfall. In addition, the Financial Plan includes a new round of Citywide Savings Program (CSP) with estimated FY 2020 savings of $1.16 billion. Overall, savings in the CSP together with additional Federal support and the use of reserves is expected to add $1.43 billion to the budget surplus estimated in the January Plan. This additional surplus will be used to increase prepayment of FY 2021 debt service.

The brunt of the fiscal impact from the economic downturn is expected to hit the FY 2021 budget. The $89.33 billion FY 2021 Executive Budget is $5.97 billion less than the January Plan. Tax revenues have been revised downward by $5.43 billion to $60.19 billion, a drop of $1.93 billion, or 3.1 percent, from FY 2020 and $1.31 billion, or 2.1 percent below FY 2019. Compounding the stress to the budget are actions in the State enacted budget which reduce State support or shift costs to the City, adding $451 million to City-funds expenditures.

Combined, the revenue shortfalls and increased spending has opened a $6.12 billion gap in the FY 2021 budget since January. The gap will be closed with drawdown of reserves, savings from the new round of CSP, additional Federal support and additional prepayment of FY 2021 debt service. The City will use Retiree Health Benefits Trust (RHBT) funds to pay $1.6 billion of the $2.25 billion retiree health insurance cost in FY 2021. Furthermore, the City is reducing the FY 2021 General Reserve by $900 million to $100 million and eliminating the $250 million FY 2021 Capital Stabilization Reserve. The new round of savings program is expected to provide another $1.50 billion of savings and the additional prepayment of FY 2021 debt service will reduce expenditure by another $1.43 billion.

While the FY 2021 and FY 2022 budgets are balanced, outyear gaps have almost doubled since the January Plan. Outyear gaps are now estimated to be $5.02 billion in FY 2022, $4.53 billion in FY 2023 and $4.90 billion in FY 2024. The Comptroller’s Office estimates that these gaps could be larger by about $1.5 billion in FY 2022 and more than $800 million in FY 2023 and FY 2024. Confronting these gaps are made the more challenging because reserves and Federal support — crucial elements in offsetting budget shortfalls in FY 2020 and FY 2021 — are significantly diminished in the outyears. Available balances for budget relief in the RHBT will be more than halved by the end of FY 2021 and there are no projections for Federal support for budget relief beyond FY 2021. In addition, much of the savings from the new round of the savings program do not extend beyond FY 2021 as a substantial portion of the spending reductions are the result of one-time efforts to combat the pandemic such as closing of schools, campuses and administrative buildings, savings on Fair Fares due to declining ridership, and delays of police officer class and cadet program.

In the face of diminishing reserves, the City will need to develop a more robust CSP, with recurring savings from efficiency initiatives accounting for a bigger part of the program. However, given the depth of the devastation to the budget, the City will need Federal support to weather the fiscal challenges in the coming fiscal years. Without Federal support, the fiscal challenge facing the City will be further compounded by the shifting of costs from the State to the City. In the absence of any Federal provision of budget relief to states and locality, the State has already announced its intention to make $8.2 billion in recurring cuts to local aid. In order to avoid drastic cuts in services in a time when these services are needed more than ever, the City will need to seek creative and innovative ways to reduce spending, and the Federal government will have to do its part to provide budget relief to state and localities.

Table 1. FY 2020 – FY 2024 Financial Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | Change FYs 2020 –2024 Dollar Percent | |

| Revenues | |||||||

| Taxes: | |||||||

| General Property Tax | $29,777 | $31,001 | $32,071 | $32,994 | $33,421 | $3,644 | 12.2% |

| Other Taxes | 31,337 | 28,264 | 31,842 | 33,560 | 34,418 | 3,081 | 9.8% |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 999 | 921 | 721 | 721 | 721 | (278) | (27.8%) |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $62,113 | $60,186 | $64,634 | $67,275 | $68,560 | $6,447 | 10.4% |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 7,552 | 6,877 | 6,830 | 6,815 | 6,817 | (735) | (9.7%) |

| Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid | 1,411 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (1,411) | (100.0%) |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (2,178) | (1,848) | (1,834) | (1,831) | (1,831) | 347 | (15.9%) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | (15) | (15) | (15) | (15) | (15) | 0 | 0.0% |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $68,883 | $65,200 | $69,615 | $72,244 | $73,531 | $4,648 | 6.7% |

| Other Categorical Grants | 1,072 | 872 | 861 | 860 | 857 | (215) | (20.1%) |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | 672 | 675 | 675 | 675 | 675 | 3 | 0.4% |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 10,832 | 7,137 | 6,964 | 6,922 | 6,917 | (3,915) | (36.1%) |

| State Categorical Grants | 15,979 | 15,448 | 16,283 | 16,738 | 16,788 | 809 | 5.1% |

| Total Revenues | $97,438 | $89,332 | $94,398 | $97,439 | $98,768 | $1,330 | 1.4% |

| Expenditures | |||||||

| Personal Service | |||||||

| Salaries and Wages | $29,750 | $30,355 | $30,370 | $31,255 | $31,800 | $2,050 | 6.9% |

| Pensions | 9,819 | 9,927 | 10,502 | 10,434 | 10,106 | 287 | 2.9% |

| Fringe Benefits | 11,255 | 11,615 | 12,504 | 13,311 | 14,119 | 2,864 | 25.4% |

| Retiree Health Benefits Trust | (1,000) | (1,600) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,000 | (100.0%) |

| Subtotal-PS | $49,824 | $50,297 | $53,376 | $55,000 | $56,025 | $6,201 | 12.4% |

| Other Than Personal Service | |||||||

| Medical Assistance | $5,987 | $5,399 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | ($72) | (1.2%) |

| Public Assistance | 1,601 | 1,651 | 1,651 | 1,650 | 1,650 | 49 | 3.1% |

| All Other | 35,312 | 30,498 | 31,037 | 31,253 | 31,494 | (3,818) | (10.8%) |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $42,900 | $37,548 | $38,603 | $38,818 | $39,059 | ($3,841) | (9.0%) |

| Debt Service | |||||||

| Principal | $3,612 | $3,718 | $3,943 | $4,053 | $4,041 | $429 | 11.9% |

| Interest & Offsets | 3,326 | 3,672 | 4,084 | 4,679 | 5,125 | $1,799 | 54.1% |

| Subtotal Debt Service | $6,938 | $7,390 | $8,027 | $8,732 | $9,166 | $2,228 | 32.1% |

| FY 2019 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | ($4,221) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $4,221 | (100.0%) |

| FY 2020 BSA | $4,155 | ($4,155) | $0 | $0 | $0 | ($4,155) | (100.0%) |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | $0 | $250 | $250 | $250 | $250 | NA |

| General Reserve | 20 | $100 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $980 | 4,900.0% |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | ($2,178) | ($1,848) | ($1,834) | ($1,831) | ($1,831) | $347 | (15.9%) |

| Total Expenditures | $97,438 | $89,332 | $99,422 | $101,969 | $103,669 | $6,231 | 6.4% |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $0 | ($5,024) | ($4,530) | ($4,901) | ($4,901) | NA |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 2. Plan-to-Plan Changes April 2020 Plan vs. January 2020 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 |

| Revenues | |||||

| Taxes: | |||||

| General Property Tax | ($58) | ($181) | ($365) | ($420) | ($698) |

| Other Taxes | (2,181) | (5,247) | (2,616) | (1,915) | (2,057) |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: Taxes | ($2,239) | ($5,428) | ($2,981) | ($2,335) | ($2,755) |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 5 | (209) | (249) | (281) | (280) |

| Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid | 1,300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (52) | 4 | 10 | 11 | 11 |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | ($986) | ($5,633) | ($3,220) | ($2,605) | ($3,024) |

| Other Categorical Grants | 66 | (2) | (3) | (3) | (4) |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | (47) | (1) | (1) | (1) | (1) |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 2,674 | 24 | (46) | (54) | (54) |

| State Categorical Grants | 305 | (355) | 20 | 18 | 19 |

| Total Revenues | $2,012 | ($5,967) | ($3,250) | ($2,645) | ($3,064) |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Personal Service | |||||

| Salaries and Wages | ($362) | ($588) | ($451) | ($473) | ($491) |

| Pensions | (13) | (12) | 80 | (24) | (6) |

| Fringe Benefits | (107) | (187) | (103) | (105) | (108) |

| Retiree Health Benefits Trust | (1,000) | (1,600) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal-PS | ($1,482) | ($2,387) | ($474) | ($602) | ($605) |

| Other Than Personal Service | |||||

| Medical Assistance | $72 | ($516) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Public Assistance | (40) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All Other | 2,408 | (376) | (64) | (36) | (28) |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $2,440 | ($892) | ($64) | ($36) | ($28) |

| Debt Service | |||||

| Principal | ($1) | ($38) | ($27) | ($32) | ($36) |

| Interest & Offsets | (45) | (73) | (104) | (142) | (164) |

| Subtotal Debt Service | ($46) | ($110) | ($131) | ($174) | ($200) |

| FY 2019 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| FY 2020 BSA | $1,432 | ($1,432) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | ($250) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| General Reserve | ($280) | ($900) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | ($52) | $4 | $10 | $11 | $11 |

| Total Expenditures | $2,012 | ($5,967) | ($659) | ($801) | ($822) |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $0 | ($2,591) | ($1,844) | ($2,242) |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 3. Plan-to-Plan Changes April 2020 Plan vs. June 2019 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 |

| Revenues | ||||

| Taxes: | ||||

| General Property Tax | ($8) | ($88) | ($257) | ($292) |

| Other Taxes | (1,300) | (4,947) | (2,338) | (1,553) |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: Taxes | ($1,308) | ($4,835) | ($2,595) | ($1,845) |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 595 | (32) | (52) | (61) |

| Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid | 1,411 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (358) | (31) | (19) | (17) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $340 | ($4,898) | ($2,666) | ($1,923) |

| Other Categorical Grants | 144 | 2 | (2) | (3) |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | (63) | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 3,604 | 66 | (34) | (45) |

| State Categorical Grants | 641 | (262) | 105 | 55 |

| Total Revenues | $4,666 | ($5,089) | ($2,594) | ($1,913) |

| Expenditures | ||||

| Personal Service | ||||

| Salaries and Wages | ($291) | ($580) | ($417) | ($419) |

| Pensions | (144) | (203) | (74) | (198) |

| Fringe Benefits | (87) | (239) | (23) | 83 |

| Retiree Health Benefits Trust | (1,000) | (1,600) | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal-PS | ($1,522) | ($2,622) | ($514) | ($534) |

| Other Than Personal Service | ||||

| Medical Assistance | $72 | ($516) | $0 | $0 |

| Public Assistance | (50) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All Other | 4,040 | 22 | 250 | 233 |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $4,062 | ($494) | $250 | $233 |

| Debt Service | ||||

| Principal | ($1) | ($8) | $84 | $86 |

| Interest & Offsets | (290) | (150) | (250) | (292) |

| Subtotal Debt Service | ($291) | ($158) | ($166) | ($206) |

| FY 2019 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| FY 2020 BSA | $4,155 | ($4,155) | $0 | $0 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | ($250) | ($250) | $0 | $0 |

| General Reserve | ($1,130) | ($900) | $0 | $0 |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | ($358) | ($31) | ($19) | ($17) |

| Total Expenditures | $4,666 | ($8,610) | ($449) | ($524) |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $3,521 | ($2,145) | ($1,389) |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 4. Risks and Offsets to the April 2020 Financial Plan

($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap)

| FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | |

| City Stated Gap | $0 | $0 | ($5,024) | ($4,530) | ($4,901) |

| Tax Revenues | |||||

| Property Tax | $0 | $119 | $279 | $607 | $883 |

| Personal Income Tax | (42) | 299 | (131) | (271) | (410) |

| Business Taxes | (115) | (508) | (370) | 27 | 207 |

| Sales Tax | 323 | (5) | (386) | (303) | (315) |

| Real Estate Transaction Taxes | (9) | 14 | (329) | (303) | (276) |

| All Other | 16 | (162) | (21) | (41) | 0 |

| Audit | 0 | 0 | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| Subtotal Tax Revenues | $173 | ($243) | ($804) | ($130) | $243 |

| Non-Tax Revenues | 0 | (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total Revenues | $173 | ($343) | ($804) | ($130) | $243 |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Overtime | $0 | ($260) | ($130) | ($130) | ($130) |

| Charter School Tuition | 0 | (35) | (205) | (380) | (600) |

| Carter Cases | 0 | (125) | (125) | (125) | (125) |

| Pupil Transportation | 0 | (75) | (75) | (75) | (75) |

| Homeless Shelters | 0 | (59) | (59) | (59) | (59) |

| Fair Fares | 0 | 30 | (100) | (100) | (100) |

| DOE Medicaid Reimbursement | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) |

| Pre-K Special Education | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| VRDB Interest Savings | 110 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General Reserve | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | $160 | ($494) | ($664) | ($839) | ($1,059) |

| Total (Risks)/Offsets | $333 | ($837) | ($1,468) | ($969) | ($816) |

| Restated (Gap)/Surplus | $333 | ($837) | ($6,492) | ($5,499) | ($5,717) |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

The City’s Economy Outlook

Comptroller’s Economic Forecast, 2020-2024

This outlook finds us facing an unparalleled economic downturn. The closing of “nonessential” businesses across the City, the nation, and the world as a public health measure to contain the COVID-19 virus is likely to cause economic activity to fall by as much as one-third in the current quarter – a scale and speed of collapse in economic activity that has no precedent in the period of modern economic data gathering.

Just as the shutdown was guided by public health considerations, the timing and pace of the re-opening of the economy and resumption of activity will be dictated by the ability to do so safely, which will be decided not only by political leaders, but by consumer sentiment. The Comptroller’s Office’s outlook and forecast assume that the economy will begin to re-open in June. Some sectors of the economy will recover more quickly than others, depending on the availability of testing and other measures to ensure public health and safety.

The major risks to this scenario are above all driven by the course of the COVID-19 virus. Re-opening of major portions of the economy prematurely could slow – or stop – economic recovery, if a resurgence of infection leads to a slower pace of re-opening, or, in the worst case, another round of shutdowns. The eagerness of businesses to re-open and workers to return to work will be tempered by the ability to ensure that doing so will not put people’s health at risk.

The year started fairly strongly given the late stage of the business cycle. There were risks to the forecast but the probability of those risks jeopardizing the expansion appeared low. Late in the first quarter, however, the impact of COVID-19 made itself felt, as state and local governments across the country imposed business closures and restrictions. As a result, economic growth will turn sharply negative in both the U.S. and New York City in 2020. After an initial bounce as lockdowns end, growth is expected to slow as the economic cycle matures in the out years. Fiscal policy will provide wage and sector support that will mitigate losses and aid a quick recovery. Systemic risks, including trade disruptions and more restrictive monetary or fiscal policy, could impede a full and speedy recovery.

Our outlook for this Executive Budget is made using what we currently know about the economy, some reasonable assumptions about how various economic actors will behave as economic activity is able to resume, and an assumption that economic activity will resume somewhat normally when the virus abates. What it can’t include are any assumptions about, or probabilities of, subsequent additional phases of infection which would lead to a return to strict social distancing and new restrictions on economic activity, or a significant change in the way businesses and individuals operate (encouraging more work from home, for example, or not shopping in local stores but ordering more goods and services online).

In our forecast, New York City’s economy is expected to fall at a slightly faster pace than the nation as a whole and recover more slowly. This is primarily a function of the City’s position as a global center and major visitor center for both tourists and business travelers. We are assuming that while the local economy recovers there will be reluctance for visitors to return to the global epicenter of the pandemic for a longer period of time than local businesses will remain closed.

Table 5. Selected Economic Indicators Comptroller’s and Mayor’s Forecasts

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||

| Selected US Economic Indicators (Annual Averages) | ||||||

| Real GDP (2012 $, % Change) | Comptroller

Mayor |

(4.6)

(5.4) |

3.2

6.3 |

3.0

4.0 |

2.6

1.6 |

2.2

1.3 |

| Payroll Jobs (Change In Millions) | Comptroller

Mayor |

(7.4)

(6.9) |

1.5

(1.3) |

0.9

8.2 |

3.6

3.2 |

4.1

0.4 |

| Fed Funds Rate (Percent) | Comptroller

Mayor |

0.3

0.4 |

0.2

0.1 |

0.5

0.1 |

1.1

0.1 |

1.9

0.1 |

| 10-Year Treasury Notes (Percent) | Comptroller

Mayor |

0.8

0.8 |

1.4

1.0 |

2.3

1.3 |

2.8

1.6 |

3.3

1.8 |

| Selected NYC Economic Indicators (Annual Averages) | ||||||

| Real GCP (2012 $, % Change) | Comptroller

Mayor |

(6.0)

(12.9) |

2.3

12.0 |

1.0

0.8 |

0.9

0.2 |

0.9

1.1 |

| Payroll Jobs (Change In Thousands) | Comptroller

Mayor |

(507.0)

(350.4) |

343.0

213.3 |

90.0

130.3 |

64.0

72.9 |

46.0

55.4 |

| Wage-Rate Growth (Percent) | Comptroller

Mayor |

(5.1)

(3.4) |

0.8

2.5 |

2.3

3.3 |

2.1

2.4 |

1.9

2.2 |

Note: Comptroller=forecast by the NYC Comptroller’s Office. GCP=Gross City Product. Mayor= forecast by the NYC Office of Management and Budget in the Executive Budget Fiscal Year 2021 Message of the Mayor.

The National Economy

The U.S. economy, as measured by real GDP, grew at annualized 2.1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019. A strong labor market with modestly increasing wages and continued accommodative monetary policy set favorable conditions for continued economic growth. But lockdowns beginning in mid-March led GDP to fall at a 4.8 percent annual rate in the first quarter of 2020. The Comptroller is forecasting GDP to fall by 4.6 percent for 2020, with a 27 percent drop in output in the second quarter (SAAR) followed by positive growth in the second half of the year. The expansion is projected to continue slightly above trend (3.2 percent and 3.0 percent) in 2021 and 2022, falling to around 2 percent in the outyears.

Net exports contributed the most to GDP growth in the recent quarter mainly because of a decline in imports. This component of growth will not contribute as strongly to growth over the Plan period — in the short run because the plants and factories providing the exportable goods are part of the lockdown, while exportable services will be lower due to travel restrictions; and in the longer run because the value of U.S. dollar will remain strong. Business investment, which had slowed prior to the lockdown and further collapsed subsequently, will resume but cautiously.

Consumer spending had made up for the recent slowdown in business investment, growing 1.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019. With American household balance sheets strong and debt burdens generally manageable, consumer spending should return once the economy is re-opened and workers are recalled to their jobs. While aggregate wages have fallen, they have not fallen as much as personal consumption. This gap results in a higher savings rate than has been experienced in recent times, giving consumers leeway to begin spending again when lockdown orders are lifted.

While Federal government expenditures, including direct wage and business supports and relief to state and local governments, have expanded by nearly $3 trillion, much of this will only serve to partially offset lost demand. State and local governments, hard-hit by declining revenues, are already retrenching. The extent to which spending will be supported by Federal aid remains to be seen, but in past recessions the impact on state and local spending usually endures beyond the end of any Federal budgetary relief.

U.S. employment in the first quarter was already feeling the impact of COVID-19 with a growth rate falling to 1.0 percent. The Comptroller is forecasting employment to fall 32 percent or 14 million jobs at annual rates and to recover about of third of those jobs (4 million) in Q3 with the opening of the economy. Layoffs are now working their way through suppliers and services firms, beyond the consumer-facing businesses which suffered the most immediate job losses when the lockdowns began.

The U.S. unemployment rate declined to 3.5 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019, marking a new low since the second quarter of 1969. Reflecting the early impact of COVID-19 in the first quarter of 2020, the unemployment rate rose to 3.8 percent and could easily go to 15 percent in the second quarter of 2020.

Prior to the COVID-19 lockdowns, despite robust job growth and rising wages, inflation remained below the Federal Reserve’s policy target of 2 percent. The Fed’s preferred measure, the personal consumption expenditure deflator, was 1.4 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019, but fell 0.3 percent in March. While recent reports of rising labor productivity are positive news for the inflation outlook, in the short term the outlook is indeterminate, as lower demand from lockdowns and high unemployment may lower prices, but supply constraints from closed plants may tend to push them higher. The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee has decided to lower the Fed Funds rate to .25 percent to promote liquidity in the banking system in light of the increased lending risks as a result of the COVID-19 virus.

On the global front, according to the IMF, worldwide economic growth finished 2019 at a healthy 2.9 percent. Growth will reverse course due to COVID-19-related lockdowns to fall 3.0 percent in 2020, and is expected to resume in 2021 at 5.8 percent.[1]

The New York City Economy

Prior to the lockdown, the City’s economy was strong and, by many measures, outperforming the U.S. Now, the Office of the Comptroller is estimating that the City’s economy has already fallen 4.2 percent in the first quarter of 2020 and will fall 31 percent in the second quarter before recovering 15.7 and 6.0 percent, respectively, in the third and fourth quarters.

The outlook for the City’s economy is somewhat more uncertain than the nation’s. The same considerations that will determine the trajectory for the U.S. economy, whether a viable vaccine can be developed in the near term, whether residents will be comfortable in resuming their activities in the absence of one, whether businesses will require employees to resume their activities on-site or whether they will continue to work remotely, whether tourists will feel comfortable traveling once again, are equally important for the City’s outlook and equally unanswerable at this time. What makes New York City more at risk is its vulnerability to future waves of infection and our dependence on both vacation visitors and business travelers.

While our baseline assumption is that U.S. economic activity will begin to slowly recover in 2020 Q3, the City’s recovery will be slower given the devastating impact the pandemic has had on the City. The City’s unique characteristics, in terms of its density and reliance on mass transit, will also make for a more challenging recovery in the City and a more staggered re-opening. While most sectors of the City’s economy are expected to be almost fully recovered by the end of 2022, industries that interact more closely with the public, such as restaurants and bars will resume either more slowly, or in a different manner compared to pre-COVID-19 world that could result in long-term reduced economic activity. The tourism and entertainment industries will likely see the slowest recovery due to their reliance on travelers.

If the broader economy outside of the tourism and entertainment sectors were to open more slowly than reflected in our baseline assumption, the impact on the City’s economy and revenue outlook would darken considerably as domino effects begin to spread throughout the economy.

The forecasts for employment and wages are driven by the extent to which different industries will be directly impacted by the shutdown, and the extent to which firms will respond to the shutdown by cutting payroll either through employment, wages, or both. This is expected to vary considerably among industries. Some office professionals have been able to work at least in some capacity remotely during the shutdown while other sectors that rely on interaction with the public have closed. High paying sectors such as finance have greater flexibility in maintaining employment at current levels through cuts in flexible pay than sectors that rely on wage workers, such as retail. Already some leaders on Wall Street have announced that they will attempt to mitigate job losses, although cutbacks in bonus pay may result as a tradeoff.[2].

The degree to which business have been impacted by the pandemic largely depends on the extent to which they rely on interacting with the public directly. Industries that can work remotely, mainly office-using professions, have been less impacted, at least for now, and spillover effects have been contained, based on data available from State unemployment claims.[3] This distinction informs the forecast for sectoral employment.

The retail, accommodation and food services, and arts and entertainment sectors of the economy are expected to be most severely impacted (losses exceeding 70 percent) by the shutdown given their greater reliance on dealing with the public. Other industries such as manufacturing, construction and real estate are also expected to experience significant if somewhat less severe job losses. Industries that can rely on telecommuting such as finance, professional and business services, management companies, and information are expected to suffer proportionately fewer losses and rebound fairly quickly.

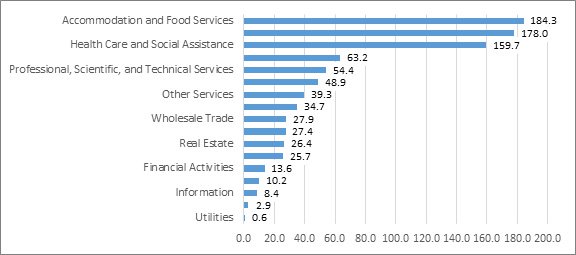

As shown in Chart 1, peak employment losses are expected to total more than 900,000 in 2020 Q2, with losses heavily concentrated in accommodation and retail. Year over-year job losses are expected to decline by over 10 percent in 2020. Even though job growth is expected to return at a fairly rapid clip we do not anticipate returning to 2019 peak employment levels until 2023 as some of the tourism and entertainment sectors continue to lag behind.

Chart 1. Projected Employment Losses by Sector, 2Q 2020

(Numbers in thousands)

*Job loss estimates include self- employed and gig workers

The near-term impact of the shutdown on wages for City workers is also expected to be extremely severe. Already Wall Street firms have signaled that in order to curtail job losses, bonuses or flexible pay will be cut. Bonuses across all industries are expected to be reduced considerably, by as much as 30 to 40 percent. The majority of City workers who do not earn bonuses will also see reduced wages as a result of layoffs, reduced work hours, pay freezes, or even pay cuts to lower-paid salaried employees. Overall, City wages are expected to decline by 5.1 percent year over year. To put this into perspective the overall wage loss in the 2001 recession was 2.6 percent, and 8.0 percent during the Great Recession when the finance industry was most severely impacted. As with the rest of the economy, the forecast assumes that growth in wages will gradually resume in 2021 and by 2024 be back to pre-COVID-19 levels.

The FY 2021 Executive Budget and April 2020 Financial Plan

On April 16 the City released the FY 2021 Executive Budget and April 2020 Financial Plan in the midst of confronting the economic, social and health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Financial Plan reflects the fiscal stress on the budget from business disruptions and the accompanying economic slowdown and the cost of combating the pandemic. Tax revenues over the current fiscal year and next are a combined $7.67 billion less than projected in the January 2020 Plan. The brunt of the fiscal impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to hit the City’s budget in FY 2021, with tax revenues projected to fall below FY 2019 level. While the FY 2021 and FY 2022 budgets are balanced, budget balance was achieved with the use of reserves and a savings program that relied significantly on spending reductions from suspensions and delays of programs and services that the Administration deemed could not go forward due to the coronavirus outbreak. However, budget gaps in the outyears have increased significantly from the January projections, with projected gaps of $5.02 billion in FY 2022, $4.53 billion in FY 2023, and $4.90 billion in FY 2024.

FY 2020 Budget

The FY 2020 Budget in the April Plan totals $97.44 billion, an increase of $2.01 billion from the January Plan. The increase is due primarily to a $2.67 billion increase in Federal categorical grants, driven by about $2.55 billion of categorical grants to support COVID-19 related expenditures. The City-funds portion of the budget is $986 million less than the January Plan.

However, the fiscal impact on the budget from the COVID-19 pandemic is far greater than $986 million reduction in the City-funds portion of the budget indicates. As shown in Table 6, the FY 2020 City-funds revenue forecast has been lowered by $2.47 billion, led by a drop of $2.24 billion in tax revenues. The reduction in non-tax revenues stems primarily from a reduction of $171 million in revenues from licenses, permits and franchises; charges for services; and fines and forfeitures due to business slowdowns, lower demand for non-essential services and reduced enforcement. Adding to the fiscal stress on the budget are actions in the State enacted budget which reduce State support or shift costs to the City. In FY 2020, a 5 percent reduction in reimbursements for Temporary Assistance to Need Families (TANF) accounts for $34 million of the $89 million increase in City-funds expenditures in Table 6.

The City is relying on $2.83 billion in Federal grants and reserves to fund the FY 2020 City-funds budget shortfall. The Plan assumes $1.4 billion in relief from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, of which $800 million will be used to fund City-funds expenditures. In addition, the FY 2020 budget includes $498 million in unrestricted Federal grants from the temporary increase in Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA). The Plan further anticipates using $250 million of FEMA assistance to fund a portion of uniformed agency overtime.

In addition to the $1.55 billion in budget relief from Federal grants, the City is reducing its payment to the Retiree Health Benefits Trust (RHBT) for FY 2020 pay-as-you-go retiree health insurance by $1 billion. This shortfall will be funded with RHBT funds which will leave the balance in the Trust at $3.7 billion at the end of the current fiscal year.

The April 2020 Financial Plan includes a new round of Citywide Savings Program which is estimated to provide budget relief of $1.16 billion. Together, the availability of Federal funds to defray City-funds expenditures, the use of reserves and the new round of Citywide Savings Program provide additional resources that exceeds the budget shortfall since January. As a result, the FY 2020 Budget is expected to add $1.43 billion to the budget surplus estimated in the January Plan.[4] This surplus will be used to increase prepayments of FY 2021 debt service.

Table 6. Changes to FY 2020 City-Funds Estimates from the January Plan

| ($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap) | |

| January 2020 Financial Plan Gap | ($0) |

| Revenue Shortfall/Spending Increase | |

| Tax Revenues | ($2,239) |

| Non-Tax Revenues | (232) |

| Expenditure Increase | (89) |

| Total Revenue Shortfall/Spending Increase | ($2,560) |

| Additional Resources | |

| Federal Support | |

| CARES Act | $800 |

| eFMAP | 498 |

| FEMA Overtime | 250 |

| Total Federal Support | $1,548 |

| Reserves | |

| Retiree Health Benefits Trust | $1,000 |

| General Reserve | 280 |

| Total Reserves | $1,280 |

| Citywide Savings Program | $1,163 |

| Total Additional Resources | $3,991 |

| Surplus Before Prepayments | $1,431 |

| Prepayments of FY 2021 Expenses | ($1,431) |

| April 2020 Financial Plan Gap | ($0) |

FY 2021 Budget

The FY 2021 Budget in the April Financial Plan totals $89.33 billion, a decrease of $5.97 billion from the January Plan. The reduction is driven by a decrease of $5.63 million in the City-funds portion of the budget. Tax revenues have been revised downward by $5.43 billion to $60.19 billion, a drop of $1.93 billion, or 3.1 percent, from FY 2020 and $1.31 billion, or 2.1 percent below FY 2019. Downward revisions to interest income to reflect the Federal Reserve’s emergency rate cuts in the face of economic turmoil account for most of the reduction in non-tax revenues. Interest income is revised downward by $152 million to $11.8 million, a precipitous drop of 95 percent from $226 million in FY 2019 and about half of the low of $22.2 million in FY 2010 following the 2008 financial crisis.

Compounding the budget shortfalls from revenue losses is the drain on City-funds revenues from the backfilling of cuts in State funding for education and social services. These cuts created shortfalls of $382 million in education funding and $69 million in TANF funding. In total, cuts in State funding account for $451 million of the $471 million increase in City-funds expenditures in Table 7.

As shown in Table 7, the FY 2021 Executive Budget is relying on the drawdown of reserves to fund a part of retiree health benefits in FY 2021. The City will use RHBT funds to pay $1.6 billion of the $2.25 billion retiree health insurance cost in FY 2021. Furthermore, the City is reducing the FY 2021 General Reserve by $900 million to $100 million and eliminating the $250 million FY 2021 Capital Stabilization Reserve.

In addition to the drawdown of reserves, the City is using $444 million of enhanced FMAP Federal funding under the FFCRA to pay the City’s share of Medicaid Assistance payments in FY 2021. Estimated budget relief of $1.50 billion from the new round of Citywide Savings Program brings total additional resources since the January Plan to $4.69 billion. These additional resources, together with debt service reduction of $1.43 billion from prepayments, allow the City to bridge the budget shortfall that has opened up since January 2020.

Table 7. Changes to FY 2021 City-Funds Estimates from the Preliminary Budget

| ($ in millions, positive number decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap) | |

| January 2020 Financial Plan Gap | ($0) |

| Revenue Shortfall/Spending Increase | |

| Tax Revenues | ($5,428) |

| Non-Tax Revenues | (225) |

| Expenditure Increase | (471) |

| Total Revenue Shortfall/Spending Increase | ($6,124) |

| Additional Resources | |

| eFMAP | $444 |

| Reserves | |

| Retiree Health Benefits Trust | $1,600 |

| General Reserve | 900 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | 250 |

| Total Reserves | $2,750 |

| Citywide Savings Program | $1,499 |

| Total Additional Resources | $4,693 |

| Gap to be Closed Before Prepayments | ($1,431) |

| FY 2020 Prepayments | $1,431 |

| April 2020 Financial Plan Gap | ($0) |

Citywide Savings Program (CSP)

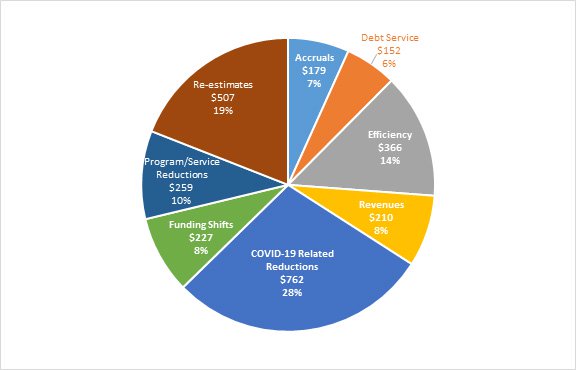

The April 2020 Financial Plan includes another round of savings that is expected to provide budget relief totaling $5.19 billion over the Plan period. Budget relief in FY 2020 and FY 2021 totals $2.66 billion and accounts for more than half of the savings over the Plan period. As Chart 2 shows, spending reductions as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic such as closing of schools, campuses and administrative buildings, savings on Fair Fares due to declining ridership, and delays of police officer class and cadet program account for $762 million, or 28 percent of the combined FY 2020 and FY 2021 savings. For the most part, these savings do not extend beyond FY 2021 as the economy is expected to open up and businesses and government are expected to return to normal level of operation. The savings program also includes program and service reductions. Temporary reductions in funding as provided for in the Fair Student Funding allocation and School Allocation Memorandum are expected to generate $140 million of the $259 million savings from program and service reductions.

Annual savings in the outyears are significantly lower than savings in the first two years of the Plan due to the reliance on non-recurring initiatives in Fiscal Years 2020 and 2021. Savings in each of the outyears of the Plan are less than $900 million, compared to savings of $1.16 billion in FY 2020 and $1.50 billion in FY 2021.

Chart 2. Combined FY 2020 and FY 2021 Citywide Savings Program

($ in millions)

Risks and Offsets

As Table 8 shows, the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the April Plan shows net additional resources of $333 million in FY 2020 and risks beginning at $837 million in FY 2021, and spiking to $1.47 billion in FY 2022 before tapering to $816 million by FY 2024.The additional resources in FY 2020 are driven by the Comptroller’s Office’s tax revenue forecast, which is higher than the City’s projections by $173 million and variable rate demand bond (VRDB) interest savings of $110 million. The Comptroller’s Office projects net expenditure risks in each of the outyears. In FY 2021 through FY 2023, the Comptroller’s Office’s lower revenue forecasts add to the expenditure risks, while a higher revenue forecast in FY 2024 helps to offset some of the expenditures. The Comptroller’s Officer’s tax revenue forecast is discussed in greater detail in “Tax Revenues” beginning on page 15.

Risks to the City’s expenditure estimates stem primarily from assumptions of overtime spending and shortfalls in funding for charter school tuition, special education Carter Cases and the Fair Fares initiative. Overall, the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the Plan indicates that the City could end FY 2020 with a budget surplus of $333 million. In the outyears, the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis shows a gap of $837 million in FY 2021, and larger gaps of $6.49 billion, $5.50 billion and $5.72 billion in FY 2022 through FY 2024, respectively.

Table 8. Risks and Offsets to the April 2020 Financial Plan

($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap)

| FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | |

| City Stated Gap | $0 | $0 | ($5,024) | ($4,530) | ($4,901) |

| Tax Revenues | |||||

| Property Tax | $0 | $119 | $279 | $607 | $883 |

| Personal Income Tax | (42) | 299 | (131) | (271) | (410) |

| Business Taxes | (115) | (508) | (370) | 27 | 207 |

| Sales Tax | 323 | (5) | (386) | (303) | (315) |

| Real Estate Transaction Taxes | (9) | 14 | (329) | (303) | (276) |

| All Other | 16 | (162) | (21) | (41) | 0 |

| Audit | 0 | 0 | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| Subtotal Tax Revenues | $173 | ($243) | ($804) | ($130) | $243 |

| Non-Tax Revenues | 0 | (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total Revenues | $173 | ($343) | ($804) | ($130) | $243 |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Overtime | $0 | ($260) | ($130) | ($130) | ($130) |

| Charter School Tuition | 0 | (35) | (205) | (380) | (600) |

| Carter Cases | 0 | (125) | (125) | (125) | (125) |

| Pupil Transportation | 0 | (75) | (75) | (75) | (75) |

| Homeless Shelters | 0 | (59) | (59) | (59) | (59) |

| Fair Fares | 0 | 30 | (100) | (100) | (100) |

| DOE Medicaid Reimbursement | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) |

| Pre-K Special Education | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| VRDB Interest Savings | 110 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General Reserve | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | $160 | ($494) | ($664) | ($839) | ($1,059) |

| Total (Risks)/Offsets | $333 | ($837) | ($1,468) | ($969) | ($816) |

| Restated (Gap)/Surplus | $333 | ($837) | ($6,492) | ($5,499) | ($5,717) |

Revenue Analysis

Tax Revenues

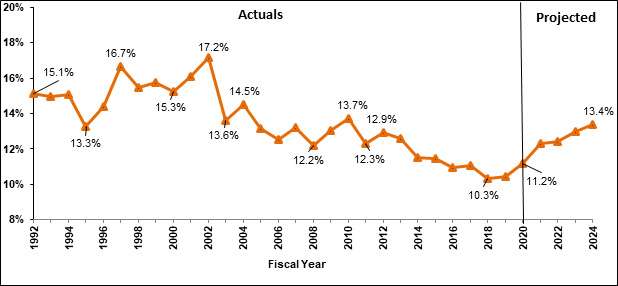

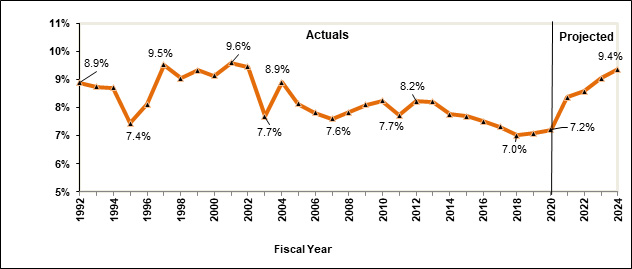

City tax revenues are expected to be severely impacted as efforts to contain the virus have shut down the local and national economies in an unprecedented manner. The effects are already being felt on most revenue streams. Sales tax revenue has plummeted as stores have closed and hotels are vacant, revenue from real estate transactions is vanishing as sales activity is put on hold, and income taxes will soon feel the effects of massive layoffs once severance and back pays are exhausted. The impact on the City’s largest tax, the property tax will, however, occur more slowly due to its lagged structure, as discussed in more detail below.

The Comptroller’s baseline forecast, which assumes a recovery for most sectors of the economy beginning in Q1 FY 2021, shows staggering losses due to the pandemic that peak at $6.2 billion dollars, or nearly a 17 percent decline in non-property tax revenue in FY 2021, as compared to the forecast in January. For most revenue streams, losses gradually diminish as the economy recovers, but significant long-term and delayed revenue impacts remain, as shown in Table 9.

Table 9. Revisions to the Comptroller’s Tax Revenue Assumptions April 2020 vs. January 2020

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 |

| Property | ($208) | ($294) | ($870) | ($1,159) | ($1,843) |

| Personal Income (PIT) | (670) | (1,988) | (1,516) | (1,277) | (1,252) |

| Business | (379) | (1,518) | (752) | (161) | (70) |

| Sales | (794) | (1,378) | (1,072) | (737) | (738) |

| Real Estate Transactions | (374) | (648) | (687) | (504) | (409) |

| All Other | 79 | (364) | (75) | (75) | (32) |

| April 2020 Financial Plan | ($2,346) | ($6,190) | ($4,972) | ($3,913) | ($4,344) |

The forecast for total tax revenues, reflecting the estimated losses due to the COVID-19 impact, is close to the City’s forecast in FY 2020 and FY 2021 (Table 10). The largest difference is in FY 2022, where revenues projected by the Comptroller are more than $800 million lower compared to the City’s estimate. While both forecasts assume a recovery will begin in FY 2021, the Comptroller’s forecast assumes that this will occur at a slower rate. Excluding property taxes, tax revenues are not expected to exceed the FY 2019 level until FY 2024 –a five-year recovery period.

Table 10. Risks and Offsets to the City’s Tax Revenue Projections

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 |

| Property | $0 | $119 | $279 | $607 | $883 |

| PIT | (42) | 299 | (131) | (271) | (410) |

| Business | (115) | (508) | (370) | 27 | 207 |

| Sales | 323 | (5) | (386) | (303) | (315) |

| Real Estate Transaction | (9) | 15 | (329) | (303) | (276) |

| Audit | 0 | 0 | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| All Other | 16 | (162) | (21) | (41) | 0 |

| Total | $173 | ($242) | ($804) | ($130) | $243 |

The high degree of uncertainty surrounding the virus’s impact and the pace of recovery of economic activity both locally and nationally, make the revenue forecast equally uncertain. There are significant downside risks that if the re-opening of the City’s economy occurs at a slower pace than assumed here, larger spillover effects could occur, compounding losses.[5] A resurgence of the virus after re-opening of the economy has begun, leading to another round of closures of businesses deemed non-essential, would also have a devastating impact on revenues. Longer-term downside risks that are not incorporated in this baseline forecast — because they are at this point unknowable — include lower population growth and/or lower business activity as individuals and firms change their behavior in response to perceived health and safety risks.

Real Estate

The current pandemic will impact property tax revenues more slowly than most other New York City taxes. In the near term, property tax revenues will be reduced by the current suspension of lien sales, deferring income from those sales from FY 2020 into FY 2021. In contrast, the suspension of Tax Commission hearings will result in a smaller reduction in assessed values from the tentative to final roll, increasing FY 2021 assessments and revenues. These short-term increases will be offset by rising delinquencies as more property owners struggle with payments.

The impacts of the current pandemic will begin to have more profound impacts in FY 2022. FY 2022 property tax revenue is based on assessments of property value done during calendar year 2020. The nature and timing of the current crisis makes this impact difficult to quantify based on limited data and rapidly changing circumstances. New York City’s complex property tax system will also cause the crisis to impact different segments of the real estate market in different ways.

The current crisis should have little impact on property tax revenues from Class 1 residential property over the Financial Plan period. Because increases in assessed values on Class 1 properties are capped at 6 percent annually and 20 percent over five years, homes whose values have appreciated more quickly are taxed at the capped value and are therefore under assessed, often dramatically. To the extent that the current crisis ultimately impacts home prices, and thereby comparable properties used in the assessment process, it will largely result in capped assessed values catching up to reflect a larger share of a property’s actual value, with a muted impact on individual property tax bills and aggregate property tax revenues.

The situation with Class 2 residential property (rental buildings, co-ops and condos) is more complicated. The shutdown of stores, restaurants and entertainment has impacted the ability of many New York City residents to pay rent, especially hourly workers. Tenants that are unable to pay, and landlords that forgive rent, imply reductions in rental income, and residential assessed values will fall as rental income falls. The extent to which this remains true through calendar year 2020 will impact rental demand, rents, and ultimately assessed values in FY 2022.

These factors are to some extent offset by Class 2 transitional values. Because changes in assessed values on larger Class 2 properties are phased-in at 20 percent per year over five years, and assessed values have been growing steadily, decreases in assessed value resulting from the impact of the epidemic on rental income will largely be offset by rising transitional values that incorporate increases in assessed values from past years that have yet to be phased in. The result is slower Class 2 property tax revenue growth, not decreased property tax revenue.

Decreases in rental income will also impact assessed values of Class 4 commercial property. Office rents will decline to the extent that increased telecommuting lowers demand for office space, uncertainty allows commercial tenants to renegotiate leases, and commercial businesses are undermined by a recession. Currently shuttered retail, in particular, will drive down rental income in commercial buildings with retail tenants. As with large Class 2 properties, these impacts will be muted by rising transitional values due to past increases in assessed value that have yet to be phased in. This is true even for properties such as hotels that may have little to no income in the near term.

The aggregate impact of these factors is projected to be a cessation of growth in assessed values of Class 2 and Class 4 properties in FY 2022, with growth in tax revenues driven exclusively by phased-in changes in assessed value from prior years. Projected growth resumes off a stunted base in FY 2023 and FY 2024, consistent with the pandemic waning later in calendar year 2020, and a re-opening of business that is largely complete by the end of the year.

Real Estate Transaction Taxes: RPTT and MRTT

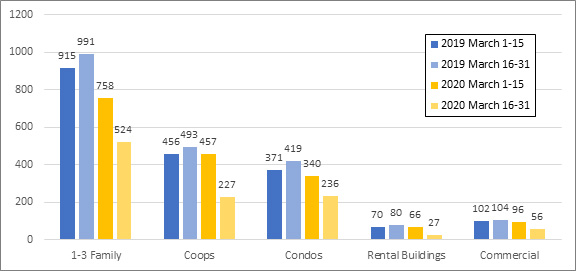

Residential and commercial real estate sales were declining in New York City even prior to the outbreak of COVID-19. During the eight-month period from July 2019 through February 2020, sales of 1- to 3-family homes declined by 7.2 percent, coops by 8 percent, condos by 12.7 percent, rental buildings by 30 percent, and commercial buildings by 3.4 percent in terms of total transaction value in dollars, compared to the comparable period a year ago. Several factors likely combined have contributed to the decline in residential sales, including the loss of state and local tax (SALT) deductions, lowered limits for interest deductions on residential mortgages in the Federal tax code, and the supplemental tax on the sales of residential real properties priced above $2 million (the “mansion tax”). In addition, changes in rent control laws that limit owners’ ability to raise rents had slowed the market for multifamily rental properties.

The pace of these declines has accelerated since stay-at-home orders were imposed starting in mid-March. The number of transactions in the second half of March for both residential and commercial properties significantly declined compared to the same period last year (Chart 3). The number of transactions of 1- to 3-family homes has declined by 47 percent, coops by 54 percent, condos by 44 percent, rental buildings by 66 percent, and commercial buildings by 46 percent, compared to the second half of March in 2019. The Comptroller’s Office projects that real estate transactions will slow to a virtual halt in the final quarter of FY 2020 with continuing stay-at-home orders making transactions challenging.

Chart 3. Number of Real Estate Transactionsin First and Second Half of March 2019 and March 2020

Source: Comptroller’s Office analysis of Department of Finance Rolling Sales Data

https://www1.nyc.gov/site/finance/taxes/property-rolling-sales-data.page

Combined revenues from real estate-related taxes (the real property transfer tax and mortgage recording tax) are expected to total only $205 million in the fourth quarter of the current fiscal year, mostly the result of sales transactions that were already agreed on. This would bring the total for the year to $2.06 billion, 15.3 percent below the Comptroller’s Office’s January Plan forecast. This revision is in line with the City’s Executive Budget forecast of $2.07 billion.

In the outyears, the Comptroller’s Office projects an offset of $15 million in FY 2021 followed by risks of $329 million in FY 2022, $303 million in FY 2023, and $276 million in FY 2024 compared to the City’s Executive budget. As the impact of COVID-19 is expected to continue throughout the summer and possibly into the fall, the Comptroller’s Office expects real estate-related taxes to decline by 11.7 percent in FY 2021. Experience from the Great Recession suggests that it takes a considerable amount of time for transaction volume to recover after a systemic shock as consumers lose purchasing power, investors become wary of risks and banks tighten lending. The Comptroller’s Office projects a much slower recovery in real estate-related taxes in outer years compared to the City’s Executive Budget, with growth relatively flat over the remainder of the forecast period. The City forecasts a decline in FY 2021 by 12.78 percent followed by a rebound of 18.75 percent in FY 2022, and growth of 2.65 percent and 1.27 percent in FY 2023 and FY 2024 respectively.

Personal Income Tax (PIT)

The forecast for PIT is highly uncertain and shares the same downside risks of a more delayed recovery and broader spillover effects associated with the economic forecast.

The near-term forecast for the largest component of PIT, withholding, follows the sharp downward trajectory of New York City employment and wages (payroll) outlined in the economic section of this report. This trajectory has a more volatile component related to bonus compensation, and a relatively more stable component related to base wages. Bonuses, the largest component of earnings for Wall Street employees, are forecast to decline by 30 to 40 percent in FY 2021 based on estimates provided by compensation specialists.[6] Large declines in bonus compensation will not be limited to Wall Street employees. Companies across all industries have announced sharp reductions in bonus pay for executives and other high salaried employees.[7]

The other driver of withholding, base compensation, is expected to decline substantially, if less dramatically than bonuses, with peak declines of 8 percent occurring in FY 2020 Q4. Cutbacks to base wages reflect expected reductions in hours worked or overtime for hourly employees, freezes on typical increases that would have normally occurred as a result of promotions, as well as pay cuts to even lower paid salaried employees who do not receive bonuses, and losses due to layoffs.[8] While some firms have boosted pay or provided hazard pay to essential employees during the pandemic, these firms represent an exception.[9]

Compared to the Comptroller’s January Plan, overall withholding is expected to slump by $380 million in FY 2020 Q4, or a 14 percent decline. Losses continue to accelerate in FY 2021 as the effects of bonus cuts become pronounced in the December through March period, resulting in an overall loss of nearly $800 million in FY 2021. Thereafter in FY 2022 through FY 2024 withholding rebounds in line with the overall recovery in the economy.

The Comptroller’s forecast for the other sources of non-withheld income tax revenue — including volatile capital gains, rents and dividends, assumes comparable losses to bonuses of 35 percent.[10]

Timing issues related to when taxpayers will recognize capital gains losses are uncertain. Taxpayers who make estimated payments could take these losses as early as July 2020, or decide to hold off until April 15, 2021 when final payments are due.[11] Our assumption is that filers will deviate from typical safe harbor provisions and begin to recognize losses as early as July 2020 and continue to recognize losses over the course of the quarterly estimated payments made in FY 2021 rather than wait until April 15, 2021.

The Comptroller expects losses in non-withholding income totaling $291 million and $1.2 billion in FY 2020 and FY 2021, respectively. This pattern of losses could be more heavily skewed to FY 2020, resulting in higher losses in FY 2020 and conversely lower losses in FY 2021, if taxpayers were to recognize significant portions of these losses earlier than assumed here.

Overall PIT revenue is expected to be $670 million lower in FY 2020 and $2.0 billion lower in FY 2021 compared to our January pre-COVID-19 estimate. These losses gradually diminish over the long run in FY 2022 through FY 2024 as growth in employment and wages resumes. The Comptroller expects PIT revenue to return to its FY 2019 level in FY 2023, at a lower level than assumed in the City’s forecast (see “Risks and Offsets to the City’s Tax Revenue Projections” in Table 10).[12]

Sales Tax

The forecast for losses in sales tax revenue reflects the impacts that the pandemic is expected to have on different sectors of the economy and the contribution of these sectors to taxable sales.

Sales related to the tourism and entertainment industries have almost completely vanished beginning in late March as hotels are mostly vacant, and restaurants and entertainment venues have closed. The tourism and restaurant sectors alone account for approximately one quarter of overall sales tax revenue, so the almost complete closure of these industries will cause sales tax revenue to decline by almost 25 percent in the current quarter. Purchases of discretionary items such as automobiles and furniture will also be severely impacted or at least delayed. Almost all sectors are forecast to experience losses with a few exceptions, notably online purchases, which have soared, as have sales for groceries and stay-at-home purchases such as video games and streaming services.[13]

Even with these offsetting sales, the forecast of lost sales tax revenue is dramatic. Sales tax revenue in FY 2020 and FY 2021 is expected to be almost $2.2 billion lower compared to the Comptroller’s January pre-COVID-19 estimate, an unprecedented decline of nearly 16 percent in FY 2021. Sales tax revenue will also be negatively impacted by the State’s decision to intercept $250 million dollars in FY 2021 and $150 million in FY 2022 to provide funding for financially distressed hospitals.

Outyear losses are forecast to diminish as the economy reopens and employment growth resumes. The recovery of the tourism and entertainment sectors, however, is expected to be slower compared to the rest of the economy and will continue to act as a drag on sales tax revenue well into FY 2022. Already firms have pulled back on business travel and conference attendance through FY 2021, so even in a best-case scenario where an effective vaccine were to be developed in the near term, travel would still resume with considerable delay given that travel decisions need to be planned well in advance.[14]

Overall, the Comptroller’s forecast for sales tax revenue over the five-year period is similar to the City’s estimate. The most significant difference is for the current quarter when the City anticipates even higher losses and revenue to be lower by $300 million compared to our baseline estimate. As with other tax revenue forecasts, the projection for sales tax revenue is both highly uncertain and very sensitive to assumptions on the pace of recovery and re-opening. Sales tax revenue could also be impacted by increased reliance on remote work by commuters.

Business Taxes

The extent of the shutdown of economic activity that has occurred is unprecedented and its impact on business taxes (General Corporation Tax and Unincorporated Business Tax combined) will be severe across almost all industries.[15] As economic activity has come to an abrupt halt, revenues have plummeted. Even service sector companies that can more easily rely on remote work are experiencing significant losses. Wall Street firms, one of the main drivers of the City’s business tax, have seen profitable business lines such as underwriting and mergers collapse during the shutdown.[16] Although these activities could resume once the economy reopens, this will take some time and the pipeline of deals that were expected to occur in FY 2020 and FY 2021 has likely been pushed back at a minimum to FY 2022. The sharp rise in reserves for losses that banks have announced in recent earning reports is also an ominous indicator.

Significant losses are expected to hit Main Street as well. Retail and personal services stores have closed and although the Federal stimulus program may have offered a lifeline that will enable some small businesses to reopen, others may never reopen. Owners of real estate are also expected to be severely impacted as a result of closures and vacancies, and rent concessions and non-payments across almost all property types are rapidly emerging. As a result of these strong headwinds, business tax losses of 25 percent compared to the pre-COVID-19 estimate are likely to occur starting in Q4 FY 2020 and continuing into FY 2021. The Comptroller’s near-term forecast for business tax revenue is lower compared to the City’s in FY 2021 by about $300 million, taking into account audits. Thereafter differences with the City diminish.

Miscellaneous Revenues

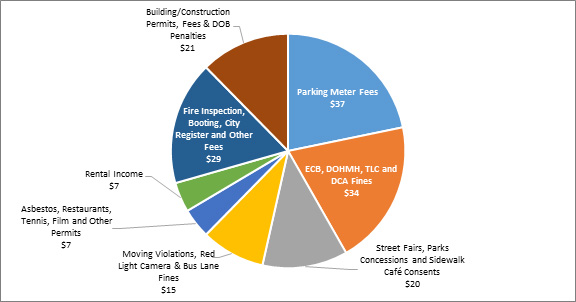

In the April 2020 Financial Plan, the City projects non-tax miscellaneous revenue of $5.37 billion in FY 2020.[17] This projection reflects the impact of the slowdown in business and social activities precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Revenues from licenses, permits and franchises; charges for services; fines and forfeitures; and interest income are reduced by a combined $171 million as a result of lower demand for non-essential City services, cancellation of public events and reduced enforcement. As shown in Chart 4, more than half of the estimated losses stem from lower revenues from parking meter fees, fines from the Environmental Control Board (ECB), Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH), Department of Correction (DOC), and Department of Buildings (DOB) fines and permits. Other projected losses include revenues from motor vehicle and camera fines and parks licenses, concessions and recreation fees.

Chart 4. COVID-19 Related Revenue Loss

($ in millions)

Source: NYC Office of Management and Budget.

As per an agreement with the Water Board, the City may request an annual rental payment for the use of City’s water and sewer infrastructure. To blunt the impact of revenue loss, the City requested half of the FY 2020 rental payment from the Water Board.[18] The rental payment of $128 million, which is credited to the Citywide Savings Program, together with $60 million from other revenue initiatives in the new round of Citywide Savings Program, provide the City with $188 million of budget relief in FY 2020. Altogether, the estimated revenue loss stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic, additional revenues in the Citywide Savings Program, and technical adjustments to projections, result in a net decrease in the FY 2020 miscellaneous revenue projection of $47 million from the January Plan estimate. Table 11 shows, the net change to miscellaneous revenues from the January Plan.

Table 11. Changes in FY 2020 Estimates January 2020 Plan vs. April 2020 Plan

| ($ in millions) | January | April | Change |

| Licenses, Permits & Franchises | $767 | $709 | ($58) |

| Interest Income | 155 | 123 | (32) |

| Charges for Services | 1,059 | 971 | (88) |

| Water and Sewer Charges | 1,589 | 1,708 | 119 |

| Rental Income | 258 | 261 | 3 |

| Fines and Forfeitures | 1,182 | 1,108 | (74) |

| Other Miscellaneous | 411 | 494 | 83 |

| Total | $5,421 | $5,374 | ($47) |

Total miscellaneous revenues are projected to decline 6.4 percent in FY 2021 to $5.03 billion and average $5.0 billion in the outyears. FY 2021 revenues in the April Plan are $205 million below the January Plan projection, with a reduction of $152 million in interest income accounting for the bulk of the decrease. The revision to interest income reflects the Fed’s emergency rate cut in response to the economic disruption from the COVID-19 pandemic. While there is a great degree of uncertainty about the duration and ripple effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the local economy and social restrictions, the Financial Plan assumes that most of the revenue loss from the slowdown in business and social activities will not extend into FY 2021. It is likely that the effects of the COVID-19 crisis will extend through the first quarter of the coming fiscal year. As such, the Comptroller projects additional COVID-19 related revenue losses of $100 million from fees, permits and fines from parks, street fairs, recreation centers, ECB quality of life and building and construction activities in FY 2021.

Federal and State Aid

Federal Stimulus Aid

As expected, the primary focus of Federal aid changes in the April Plan is on Federal stimulus funds and FEMA reimbursement to address the COVID-19 crisis. In response to the crisis, Congress passed a series of stimulus bills containing various measures to provide relief to the City and help mitigate costs stemming from the crisis. As shown in Table 12, the April Plan has incorporated a total of $4.3 billion in COVID-19 related Federal assistance in FY 2020 and FY 2021, including $2.5 billion for expenditures that are eligible for FEMA reimbursements.

Under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, the Federal government enacted a temporary 6.2 percentage point increase in its share of Medicaid reimbursement, known as Enhanced Federal Medicaid Assistance Percentage (eFMAP). The eFMAP assistance is expected to remain in effect through calendar year 2020, providing the City with $942 million in total relief. These savings are reflected in the Plan as $498 million in unrestricted aid for FY 2020 and $444 million in Medicaid expense offset for FY 2021.

The April Plan also anticipates receiving $1.4 billion in direct relief under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. The City has incorporated $800 million of CARES funding under its unrestricted aid assumption and applied the remaining $600 million to fund its share of certain FEMA-eligible costs, at an expected FEMA reimbursement rate of 75 percent. Since the release of the Executive Budget, however, the Governor has indicated that the President has agreed to waive the 25 percent local match for FEMA assistance. The local match waiver could free up the $600 million in CARES Act funding to cover needs in other areas, once the City reflects the higher reimbursement rate for projected FEMA-eligible costs.

Table 12. Federal Assistance for COVID-19 Relief

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FYs 20-21 Total |

| FEMA-Emergency Measures | $1,624 | $37 | $1,661 |

| FEMA-Emergency Measures (CARES Act) | 600 | 0 | 600 |

| FEMA-Overtime | 250 | 0 | 250 |

| Enhanced FMAP | 498 | 444 | 942 |

| CARES Act | 800 | 0 | 800 |

| Other | 45 | 0 | 45 |

| Total Assistance | $3,817 | $481 | $4,298 |

State Budget

Like the City, New York State is facing its own fiscal strain from the coronavirus. The State projects that revenues in state fiscal year (SFY) 2020 – 2021 will fall $13.3 billion below pre-coronavirus projections, and compared to the prior year, all funds tax receipts are expected to fall by 8.9 percent. As of April 22, 2020, the State has reported $2.8 billion in expenses related to COVID-19. While the State has received some assistance through the Federal stimulus bills passed to date, including a temporary increase in the Federal Medicaid reimbursement rate and $5.1 billion from the Coronavirus Relief Fund, the full extent of the pandemic’s impact on the State’s fiscal situation remains unclear.

Amid these challenges, the State adopted a budget for SFY 2020-21 that has a combined negative impact on the City budget of at least $776 million over city fiscal years 2020 and 2021. Moreover, the adopted state budget was premised on the ability to use broad new executive powers to implement steep, mid-year reductions in local aid. The State has already announced its intention to detail $8.2 billion in recurring cuts to local aid sometime in mid-May.

Table 13. Impact of Adopted 2020-21 State Budget

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | Total |

| School Aid | |||

| Formula-based Aid Shortfall | $20 | ($360) | ($340) |

| Subtotal, School Aid | $20 | ($360) | ($340) |

| Cost Shifts | |||

| Sales Tax Intercept | $0 | ($250) | ($250) |

| Family Assistance | (34) | (68) | (102) |

| Paratransit | 0 | (63) | (63) |

| Child Welfare | (7) | (14) | (21) |

| Subtotal, Cost Shifts | ($41) | ($395) | ($436) |

| Total | ($21) | ($755) | ($776) |

Note: In addition to the above, the State may impose penalties on the City if the NYPD does not move its tow pound on Pier 76 on the Hudson River by the end of calendar year 2020.

School Aid

While the Federal CARES Act should provide $717 million in Education Stabilization Funds for New York City, the State chose to reduce state aid by a commensurate amount through a “Pandemic Adjustment.” However, in order to receive the Federal funds, states cannot reduce state school support for elementary and secondary education in fiscal years 2020 and 2021 below the average of the three fiscal years preceding the CARES Act enactment. Thus, potential mid-year reductions to state school aid could put these Federal funds at risk.

Additionally, the State froze Foundation Aid, the largest source of school aid funding, in the coming school year. Including other forms of aid, total formula-based state school aid for FY 2021 was $360 million below the City’s January projection. The City chose to replace the lost State aid with City funds, while at the same time reducing City-funds by $470 million through the Citywide Savings Plan, for a net reduction of $87.5 million in City funding to the DOE.

Other Cost Shifts to NYC

The State Budget imposes a new two-year obligation on the City and other counties to contribute to assistance for financially distressed hospitals and nursing homes. To fund this new obligation, the State will intercept $250 million from City sales taxes in FY 2021 and $150 million in FY 2022.

For the second year in a row, the State has also lowered the reimbursement rate for Family Assistance programs for New York City, dropping the rate from 90 percent to 85 percent. This action follows a reduction from 100 percent to 90 percent last year. The shift will cost $68 million annually beginning in FY 2021 and primarily impact funding at the Department of Social Services and the Department of Homeless Services.

Additionally, the State raised the threshold for child welfare spending reimbursement, resulting in a cost of $7 million in FY 2020 and $14 million annually beginning in FY 2021. The City is exploring using Federal funding to backfill these costs in FY 2020 and FY 2021, and therefore has not reflected additional costs in the Financial Plan until FY 2022.

The City may face additional state-imposed costs if the Police Department tow pound on Pier 76 on the Hudson River is not relocated by the end of 2020. The City faces an initial $12 million fine and an additional $3 million per month until the pound is moved. Total penalties could amount to up to $27 million in FY 2021.

The State budget also intercepts $40 million from the Manhattan District Attorney Office’s pool of bank settlements to assist with discovery law compliance across the state. Legislative changes included in the State budget also expand the amount of time district attorneys have to turn over evidence to defendants, while expanding the list of bail-eligible offenses under bail reforms adopted last year.

Potential Mid-year State Aid Reductions

The State budget included expansive executive powers to impose mid-year across-the-board reductions in local aid following three defined “measurement periods.” These periods conclude at the end of April, June and December. State receipts and disbursements in the month of April will be measured against projections in the Financial Plan issued in February 2020, prior to the shutdown of non-essential services and prior to the delay in the final deadline for income tax returns. The latter periods will be measured against the Enacted Budget.

The State has already announced its intention to use these powers to implement $8.2 billion in cuts to local aid during SFY 2020-21 following the April measurement period. The details will not be announced until the State Comptroller releases the cash report for April.[19] The legislature would have ten days to prepare its own plan, or the cuts will go into effect automatically.

However, if tax receipts through February 28, 2021, are not less than 98 percent of estimates, or the Federal government provides aid that is deemed sufficient, reductions may be repaid in full or in part. Before any payments are made, the director of the budget must certify that: (1) the general fund has resources sufficient to make all planned payments anticipated in the 2020 – 21 Financial Plan including tax refunds, without the issuance of deficit bonds or notes or extraordinary cash management actions; (2) the balances in the tax stabilization reserve and rainy day reserve have been restored to a level equal to the level as of the start of the fiscal year; and (3) other designated balances have been maintained.

MTA Financing

The State Budget also includes new city funding requirements for the MTA. The City will be required to match a $3 billion state appropriation for the MTA’s 2020-2024 Capital Plan, and the City will also be required to fund 50 percent of MTA paratransit costs, net of fare revenues and tax subsidies, starting July 1, 2020. As of the April financial plan, the City Capital Plan includes just $200 million for the MTA’s 2020 – 2024 Capital Plan, a shortfall of $2.8 billion from the new state requirement.

Currently, the City contributes $175 million annually to paratransit, which totals 33 percent of net expenses. Under the new State legislation, the City’s contribution to paratransit will be capped at $215 million in calendar year 2020, $277 million in 2021, $290 million in 2022, and $310 million in 2023. If payments are not made, the State Comptroller can withhold funds to the City to satisfy these new requirements.

The City estimates that the paratransit requirement will cost $63 million in FY 2021, in addition to the previously anticipated $175 million city contribution. The actual cost will depend on paratransit ridership and costs, which are likely to be depressed in the coming year as riders limit public exposure. The City forecasts that paratransit ridership will be one-third of normal ridership levels in the first quarter of FY 2021 and two-thirds of normal ridership in the second quarter. Once paratransit trends return to their pre-pandemic baseline, the additional cost to the City could exceed $100 million annually.

Expenditures Analysis