Comments on New York City’s Preliminary Budget for Fiscal Year 2021 and Financial Plan for Fiscal Years 2020 – 2024

I. Executive Summary

The ongoing U.S. economic expansion surpassed the ten-year mark in 2019, with GDP growing by 2.3 percent. The Comptroller’s Office expects the economy to continue growing over the Plan period but at a slower rate, consistent with the mature stage of the current expansion. The risk of a recession is minimal, mitigated by a healthy consumer sector, low oil prices and accommodative monetary policy by the Federal Reserve. With trade tension between the U.S. and China abating, the largest immediate risk to the outlook is the potential of the COVID-19 outbreak turning into a pandemic and its subsequent impact on the global economy.

However, the largest immediate threat to the City’s budget is the potential of significant cuts in State funding and cost shifts from the State to the City, as proposed in the State Executive Budget. The City estimates that in total, the proposals in the State Executive Budget would have a negative impact of more than $1.3 billion on the City over FY 2020 and FY 2021.

The FY 2021 Preliminary Budget released on January 16, before the release of the State Executive Budget, does not reflect the impact of the State Executive Budget. The Preliminary Budget is balanced at $95.3 billion, and closes a $3.02 billion gap projected in November. Revenues in the Preliminary Budget are $705 million higher than projected in the November Plan, driven by a net upward revision of $658 million in tax revenues.

Expenditures are $2.3 billion lower, driven by an increase of $2.17 billion in planned prepayment of FY 2021 debt service. Net of this reduction in debt service from the additional prepayment, City-funds expenditures are $183 million less than estimated in November. This expenditure decrease stems primarily from spending reductions of $253 million from a new round of Citywide Savings Program (CSP), and $173 million from a modification in the methodology for funding guaranteed interest earnings in the tax deferred annuity (TDA) funds of the Teachers Retirement System and the Board of Education Retirement System. These reductions are partially offset by a $162 million increase in City-funds agency spending and smaller adjustments to collective bargaining costs and miscellaneous spending.

The Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the January Plan has identified net additional resources in each year of the Financial Plan ranging from a low of $29 million in FY 2021 to a high of $707 million in FY 2024. The additional resources in FY 2020 are driven by both the Comptroller’s Office’s tax revenue forecast, which is higher than the City’s projection by $281 million, and the Comptroller’s Office’s assumption that the $300 million in the General Reserve will be available for budget relief in the current fiscal year. In the outyears, the additional resources identified by the Comptroller’s Office stem primarily from higher tax revenue forecasts in each year of the Plan, beginning at $520 million in FY 2021 and growing to $1.83 billion by FY 2024.

Net risks to the City’s expenditure estimates, beginning at $526 million in FY 2021 and growing to $1.17 billion in FY 2024 offset some of the gains from the higher revenue forecast in the outyears. These risks stem primarily from assumptions of overtime spending and shortfalls in funding for charter school tuition, Carter cases, pupil transportation, homeless shelters, and the Fair Fares initiative. Projected underspending for public assistance (PA) due to declining caseloads, pre-K special education savings and lower than projected variable rate demand bond (VRDB) interest provide some offsets against these risks.

Overall, the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the Plan indicates that the City could end FY 2020 and FY 2021 with budget surpluses of $459 million and $29 million, respectively. In the outyears, the Comptroller’s Office analysis shows smaller gaps of $2.00 billion, $2.22 billion and $1.95 billion in FY 2022 through FY 2024, respectively.

Table 1. FY 2020 – FY 2024 Financial Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | Change FYs 2020 –2024 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dollar | Percent | ||||||

| Revenues | |||||||

| Taxes: | |||||||

| General Property Tax | $29,835 | $31,182 | $32,436 | $33,414 | $34,119 | $4,284 | 14.4% |

| Other Taxes | 33,518 | 33,511 | 34,458 | 35,475 | 36,475 | 2,957 | 8.8% |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 999 | 921 | 721 | 721 | 721 | (278) | (27.8%) |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $64,352 | $65,614 | $67,615 | $69,610 | $71,315 | $6,963 | 10.8% |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 7,547 | 7,086 | 7,079 | 7,096 | 7,097 | (450) | (6.0%) |

| Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid | 111 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (111) | (100.0%) |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (2,126) | (1,852) | (1,844) | (1,842) | (1,842) | 284 | (13.4%) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | (15) | (15) | (15) | (15) | (15) | 0 | 0.0% |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $69,869 | $70,833 | $72,835 | $74,849 | $76,555 | $6,686 | 9.6% |

| Other Categorical Grants | 1,006 | 874 | 864 | 863 | 861 | (145) | (14.4%) |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | 719 | 676 | 676 | 676 | 676 | (43) | (6.0%) |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 8,158 | 7,113 | 7,010 | 6,976 | 6,971 | (1,187) | (14.6%) |

| State Categorical Grants | 15,674 | 15,803 | 16,263 | 16,720 | 16,769 | 1,095 | 7.0% |

| Total Revenues | $95,426 | $95,299 | $97,648 | $100,084 | $101,832 | $6,406 | 6.7% |

| Expenditures | |||||||

| Personal Service | |||||||

| Salaries and Wages | $30,112 | $30,943 | $30,821 | $31,728 | $32,291 | $2,179 | 7.2% |

| Pensions | 9,832 | 9,939 | 10,422 | 10,458 | 10,112 | 280 | 2.8% |

| Fringe Benefits | 11,362 | 11,802 | 12,607 | 13,416 | 14,227 | 2,865 | 25.2% |

| Subtotal-PS | $51,306 | $52,684 | $53,850 | $55,602 | $56,630 | $5,324 | 10.4% |

| Other Than Personal Service | |||||||

| Medical Assistance | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $0 | 0.0% |

| Public Assistance | 1,641 | 1,651 | 1,651 | 1,650 | 1,650 | 9 | 0.5% |

| All Other | 32,904 | 30,874 | 31,101 | 31,289 | 31,522 | (1,382) | (4.2%) |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $40,460 | $38,440 | $38,667 | $38,854 | $39,087 | ($1,373) | (3.4%) |

| Debt Service | |||||||

| Principal | $3,613 | $3,756 | $3,970 | $4,085 | $4,077 | $464 | 12.8% |

| Interest & Offsets | 3,371 | 3,745 | 4,188 | 4,821 | 5,289 | 1,919 | 56.9% |

| Subtotal Debt Service | $6,984 | $7,500 | $8,158 | $8,906 | $9,366 | $2,382 | 34.1% |

| FY 2019 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | ($4,221) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $4,221 | (100.0%) |

| FY 2020 BSA | $2,723 | ($2,723) | $0 | $0 | $0 | ($2,723) | (100.0%) |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | $250 | $250 | $250 | $250 | $250 | NA |

| General Reserve | $300 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $700 | 233.3% |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | ($2,126) | ($1,852) | ($1,844) | ($1,842) | ($1,842) | $284 | (13.4%) |

| Total Expenditures | $95,426 | $95,299 | $100,081 | $102,770 | $104,491 | $9,065 | 9.5% |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $0 | ($2,433) | ($2,686) | ($2,659) | ($2,659) | NA |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 2. Plan-to-Plan Changes

January 2020 Plan vs. November 2019 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenues | ||||

| Taxes: | ||||

| General Property Tax | $50 | $93 | $108 | $128 |

| Other Taxes | 399 | 300 | 278 | 362 |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $449 | $593 | $386 | $490 |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 149 | 66 | 55 | 54 |

| Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid | 111 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (31) | (1) | (1) | (1) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $678 | $658 | $440 | $543 |

| Other Categorical Grants | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 145 | 32 | 16 | 14 |

| State Categorical Grants | 186 | 13 | 12 | 13 |

| Total Revenues | $1,032 | $705 | $471 | $573 |

| Expenditures | ||||

| Personal Service | ||||

| Salaries and Wages | $41 | $72 | $91 | $117 |

| Pensions | (134) | (174) | (116) | (117) |

| Fringe Benefits | (54) | (72) | 60 | 167 |

| Subtotal-PS | ($146) | ($174) | $35 | $167 |

| Other Than Personal Service | ||||

| Medical Assistance | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Public Assistance | (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All Other | 279 | 50 | (66) | (68) |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $269 | $50 | ($66) | ($68) |

| Debt Service | ||||

| Principal | $0 | ($3) | $21 | $22 |

| Interest & Offsets | (133) | (8) | (36) | (58) |

| Subtotal Debt Service | ($133) | ($12) | ($15) | ($36) |

| FY 2019 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| FY 2020 BSA | $2,173 | ($2,173) | $0 | $0 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | ($250) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| General Reserve | ($850) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | ($31) | ($1) | ($1) | ($1) |

| Total Expenditures | $1,032 | ($2,310) | ($47) | $62 |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $3,015 | $518 | $511 |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 3. Plan-to-Plan Changes

January 2020 Plan vs. June 2019 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenues | ||||

| Taxes: | ||||

| General Property Tax | $50 | $93 | $108 | $128 |

| Other Taxes | 881 | 300 | 278 | 362 |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $931 | $593 | $386 | $490 |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 590 | 177 | 197 | 220 |

| Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid | 111 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (306) | (35) | (29) | (28) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $1,326 | $735 | $554 | $682 |

| Other Categorical Grants | 78 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | (16) | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 930 | 42 | 12 | 9 |

| State Categorical Grants | 336 | 93 | 85 | 37 |

| Total Revenues | $2,654 | $878 | $656 | $732 |

| Expenditures | ||||

| Personal Service | ||||

| Salaries and Wages | $71 | $8 | $34 | $54 |

| Pensions | (132) | (191) | (154) | (174) |

| Fringe Benefits | 20 | (52) | 80 | 188 |

| Subtotal-PS | ($40) | ($235) | ($40) | $68 |

| Other Than Personal Service | ||||

| Medical Assistance | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Public Assistance | (10) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All Other | 1,632 | 398 | 314 | 269 |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $1,622 | $398 | $314 | $269 |

| Debt Service | ||||

| Principal | $0 | $30 | $111 | $118 |

| Interest & Offsets | (245) | (77) | (146) | (150) |

| Subtotal Debt Service | ($245) | ($48) | ($35) | ($32) |

| FY 2019 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| FY 2020 BSA | $2,723 | ($2,723) | $0 | $0 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | ($250) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| General Reserve | ($850) | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | ($306) | ($35) | ($29) | ($28) |

| Total Expenditures | $2,654 | ($2,643) | $210 | $277 |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $3,521 | $446 | $455 |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 4. Risks and Offsets to the January 2020 Financial Plan

($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap)

| FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City Stated Gap | $0 | $0 | ($2,433) | ($2,686) | ($2,659) |

| Tax Revenues | |||||

| Property Tax | $150 | $232 | $784 | $1,346 | $2,028 |

| Personal Income Tax | 148 | 146 | 60 | (78) | (215) |

| Business Taxes | (54) | (118) | (73) | (25) | (1) |

| Sales Tax | (24) | 17 | (22) | (69) | (144) |

| Real Estate Transaction Taxes | 61 | 243 | 284 | 121 | 10 |

| Audit | 0 | 0 | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| Subtotal Tax Revenues | $281 | $520 | $1,187 | $1,449 | $1,832 |

| Fines | 16 | 35 | 48 | 48 | 48 |

| Total Revenues | $297 | $555 | $1,235 | $1,497 | $1,880 |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Overtime | ($258) | ($262) | ($150) | ($150) | ($150) |

| Charter School Tuition | 0 | (150) | (334) | (562) | (709) |

| Carter Cases | 0 | (125) | (125) | (125) | (125) |

| Pupil Transportation | (50) | (75) | (75) | (75) | (75) |

| Homeless Shelters | 0 | (49) | (49) | (49) | (49) |

| Fair Fares | 50 | 0 | (200) | (200) | (200) |

| DOE Medicaid Reimbursement | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) |

| Pre-K Special Education | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Public Assistance | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| VRDB Interest Savings | 60 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 |

| General Reserve | 300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | $162 | ($526) | ($798) | ($1,026) | ($1,173) |

| Total (Risks)/Offsets | $459 | $29 | $437 | $471 | $707 |

| Restated (Gap)/Surplus | $459 | $29 | ($1,996) | ($2,215) | ($1,952) |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

II. The City’s Economic Outlook

The Economy in 2019

The U.S. economy continues to chug along in defiance of popular wisdom that a recession is inevitable after more than a decade of uninterrupted growth. Despite record low unemployment, the labor force continues to attract workers who had been out of the workforce, enabling continued growth in employment. Wages are rising, yet inflation is well below the Federal Reserve’s two percent target. Consumer and government spending are keeping the economy growing. As a result, there is little expectation that the Fed will increase interest rates in 2020.

Inextricably linked to U.S. economic growth, the City’s economy also continued to grow in 2019. With a business climate more focused on the service sector and less on manufacturing, the City outperformed the U.S. on a number of measures, including employment growth and growth in average hourly earnings. While growth rates will temper, the Comptroller’s Office is not expecting a downturn in the city during the Financial Plan period.

With the risk of a return of trade tensions abating, the impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on China, and the knock-on effects on other major U.S. trading partners poses the largest immediate risk to the outlook.

U.S. Economic Outlook

The U.S. economic expansion surpassed the ten-year mark in 2019, making it the longest U.S. expansion on record. Real gross domestic product (GDP) grew 2.3 percent in 2019, according to preliminary estimates released by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, equal to average GDP growth thus far since the end of the Great Recession. Consumer spending grew 2.6 percent in 2019, a bit slower than the 3.0 percent in 2018. Growth in private investment (structures, plant equipment, intellectual property, and inventories) slowed to 1.8 percent. The largest contributor to investment growth was a 2.1 percent rise in nonresidential fixed investment, which includes business structures, equipment, and intellectual property. Although business structures declined 4.4 percent, a healthy 7.7 percent increase in intellectual property more than offset the decline.

The nation’s labor market performed well in 2019, with U.S. businesses adding over 2.0 million jobs (a gain of 1.4 percent), marking the ninth consecutive year of job growth. The unemployment rate fell to 3.7 percent on a seasonally adjusted basis during 2019, the lowest rate since 1969. The tight labor market led to a record rise in earnings. Average hourly earnings of U.S. private employees rose 3.3 percent — slightly higher than the previous high of 3.1 percent dating back to 2008. Despite healthy wage increases, the core inflation rate (personal consumption expenditures excluding the food and energy sectors) rose only 1.6 percent, well below the Federal Reserve’s target rate of 2 percent.

The Comptroller believes economic growth will slow in 2020 and will continue growing in the outyears at slower rates consistent with the current mature stage of the expansion. The reasons for expecting continued growth are a healthy consumer sector, low oil prices, and accommodative monetary policy by the Federal Reserve. Consumer spending — fueled by a strong labor market and wage gains, healthy household balance sheets, and low oil prices — should help the economy remain strong in 2020. Monthly payroll jobs grew by 175,000 on average in 2019. While somewhat lower than the 193,000 average monthly job gain in 2018, payroll jobs nonetheless grew by 225,000 in January 2020.

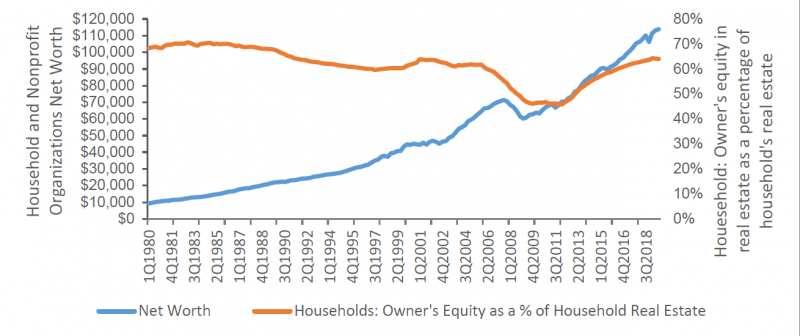

Consumer financials are strong. The household financial obligations ratio (which measures a household’s total financial obligations as a percentage of disposable personal income), debt service ratio (DSR, which measures the amount of payments on outstanding debt by households as a percentage of disposable personal income), and the mortgage component of the DSR are all at historical record lows.[1] This indicates that households can increase their borrowing to finance current consumption from future earnings more easily than in 2008, for example, when these ratios were at or near record highs. Chart 1 shows household financial obligation and debt service ratios, and the mortgage component of the DSR. Consumer net worth is at its historical high of $113.8 trillion and household’s owner’s equity in real estate is at a healthy 64 percent, as shown in Chart 2.

Chart 1. Household Debt Service Obligations, 1980Q1 to 2019Q3

Source: Federal Reserve Board of Governors

Chart 2. Household and Nonprofit Organizations Net Worth, & Owner’s Equity as a Percentage of Household Real Estate 1980Q1 to 2019Q3

($ in trillions)

Source: Federal Reserve Board of Governors

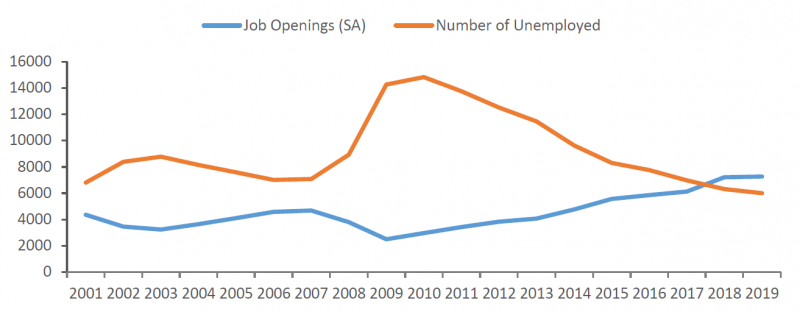

Risk of a recession over the planning horizon appears to be negligible as the major risks – including trade tensions with China; stable and accommodative monetary policy; and other global uncertainties including Brexit — have abated. The major immediate risk is the impact of the 2019nCoV virus on consumption and production in China and globally. A secondary risk is that business growth is constrained by an inability to staff open positions with qualified workers. For the past two years there have been more open, unfilled positions in the nation than unemployed workers, as illustrated by Chart 3.

Chart 3. Annual U.S. Job Openings vs Unemployed Workers 2001 – 2019

Note: Annual job openings do not include December 2019, hence seasonally adjusted data.

Source: The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

New York City’s Economic Condition and Outlook

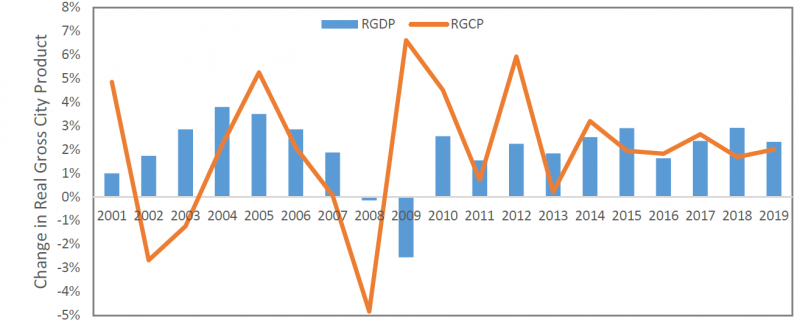

The New York City economy grew 2.0 percent in 2019, according to our preliminary estimates, slightly lower than the nation’s 2.3 percent growth. The Comptroller expects the City’s economic growth to continue throughout the forecast period without a recession. However, the pace of that growth is expected to slow, consistent with the late stage of the business cycle. It is our expectation that the City will experience slightly faster growth than the nation in 2020 through 2022 and lower growth rate in the outyears.

Chart 4. Change in Real GDP and GCP, 2001 to 2019

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and NYC Comptroller’s Office

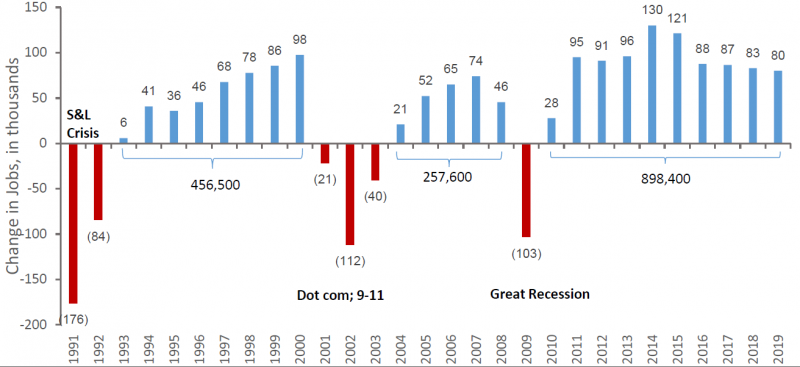

Private-sector jobs grew 2.0 percent, or 80,100 jobs, in the City in 2019, above the 1.5 percent growth in the U.S. as a whole. This is the City’s tenth consecutive year of job creation, making it the longest sequence of job gains on record. Since the City’s recovery from the recession began in 2010, private-sector jobs have increased by nearly 900,000, or 28.6 percent, to a record high of 4.04 million workers. Private sector job growth reached a peak of 130,100 jobs in 2014 and has tapered off since then (Chart 5). But growth of more than 80,000 jobs per year is still robust and is above the historical average of about 37,100 per year.

The City’s unemployment rate remains at a record low of 4.1 percent in 2019. The labor force declined by 30,454 and stood at 4.1 million. The labor force participation rate experienced a marginal drop to 60.6 percent in 2019 after reaching 60.8 percent in 2018. Similarly, the number of city residents employed decreased by 28,515 to settle at about 3.9 million, and the employment-to-population ratio marginally dropped to 58.1 percent in 2019, after reaching a record high of 58.3 percent in 2018.

Chart 5. Change in NYC Private Sector Jobs: Three Cycles

Source: NYS Department of Labor and the Bureau of Labor Statistics

The tightening labor market and an increase in the City’s minimum wage to $15.00 per hour is likely behind an increase in the City’s average hourly earnings. Average hourly earnings of all employees in the private sector rose 4.1 percent in 2019, higher than the 3.1 percent increase in 2018, and well above the 2.5 percent average growth since 2007. The NY Metro area inflation rate, as measured by the change in consumer price index, was 1.7 percent in 2019 and 1.9 percent in 2018, indicating that New Yorkers are seeing real gains in the purchasing power of their earnings.

The income distribution of jobs by sector remained fairly constant from 2018 to 2019 based on the latest data from the NYS Department of Labor. Thirty-seven percent of the City workforce are in sectors in the lowest tier by average income; 25 percent are in the middle tier; and 38 percent are in the highest income tier.[2]

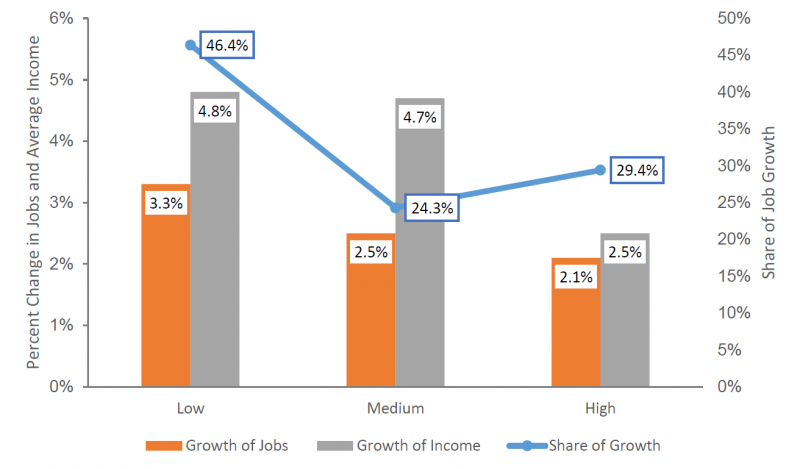

New jobs created were heavily skewed towards the lower income tier with 46.4 percent of new jobs, followed by the highest tier with 29.4 percent of new positions, and the middle tier with 24.3 percent (Chart 6). Job growth in 2019 was strongest among lower-wage sectors, at 3.3 percent. Wages in both low- and medium-tier sectors grew robustly at 4.8 percent 4.7 percent, respectively.

Chart 6. Change and Composition of NYC Employment By Income Category

Source: NYS Department of Labor and NYC Comptroller’s Office. See footnote 2 for definitions of income categories.

Wall Street profits, as measured by the pre-tax net income of the NYSE member firms, rose 9.7 percent to $22.6 billion in the first three quarters of 2019, the highest since $49.7 billion generated in the first three quarters of 2009. Wall Street bonuses, a major contributor to City revenues through the income tax and a proxy for firms’ profitability, are expected to be strong next year.

According to PwC/CB Money Tree, venture capital investment in the New York metro area rose to a record high of $17.21 billion in 2019, growing 19.2 percent over 2018, while the nation as a whole experienced an 8.9 percent decline.

Total new commercial leasing activity in Manhattan dropped 3.5 percent to 34.7 million square feet (msf) in 2019, according to Cushman and Wakefield (C&W), after reaching a record 35.9 million square feet (msf) in 2018. Based on C&W’s data, Manhattan’s newly constructed office space entering the market is expected to be robust in 2020 but it will certainly not reach 2018 levels.

Douglas Elliman reports the number of residential units sold fell in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens in 2019 for the second straight year. The average sales price fell in Manhattan and Brooklyn, but increased in Queens. Reasons for the slowdown may include limits on the deductibility of state and local taxes on the Federal income tax as well as possible overbuilding in certain segments of the market and slowing population growth.

The latest leading economic indicators for the City point to a mixed picture. An assessment of business conditions among firms in the New York City area is provided by ISM-New York, Inc. The most recent report shows that current business conditions index (which measure the current state of the economy from the perspective of business procurement professionals) was 45.7 in Q4 2019, lower than the 50 percent threshold that indicates the expectation of continued expansion. However, the ISM six-month outlook (which measures where procurement professionals expect the economy to be in six months) was 60.2 in Q4 2019, about the same as the 59.9 in Q3 2019 and above the 50 threshold.

Initial unemployment claims, which show the number of applicants for unemployment insurance, declined in the City for the ninth consecutive year. According to the NYS Department of Labor, average initial unemployment claims fell 2.0 percent to 27,558 (the lowest on record) in 2019 from 28,112 in 2018. However this statistic bears watching as Q4 2019 initial claims increased 5.2 percent over Q4 2018.

Finally, according to NYC & Company, the number of visitors to the city is expected to have increased to a record 67.1 million in 2019, the tenth straight annual increase. The COVID-19 virus outbreak is expected to significantly reduce Chinese tourism during 2020, which, although representing just 2 percent of total visitors, could modestly slow the expected growth in the number of visitors in 2020.

Table 5 provides summary projections for seven NYC and U.S. economic indicators from 2020 to 2024, comparing NYC OMB January forecast with the Comptroller’s Office forecast.

Table 5. Selected Economic Indicators, Annual Averages, Comptroller and Mayor’s forecast, 2020 to 2024

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selected US Economic Indicators (Annual Averages) | ||||||

| Real GDP (2012 $, % Change) | Comptroller

Mayor |

1.9

2.1 |

1.6

2.0 |

1.5

1.7 |

1.7

1.5 |

1.7

1.9 |

| Payroll Jobs (Change In Millions) | Comptroller

Mayor |

1.6

1.8 |

1.3

1.1 |

1.0

0.7 |

0.8

0.1 |

0.8

0.3 |

| Fed Funds Rate (Percent) | Comptroller

Mayor |

1.7

1.7 |

2.0

2.1 |

2.4

2.4 |

2.8

2.6 |

2.8

2.6 |

| 10-Year Treasury Notes, (percent) | Comptroller

Mayor |

2.2

2.1 |

2.5

2.7 |

3.0

2.9 |

3.2

3.0 |

3.3

3.0 |

| Selected NYC Economic Indicators (Annual Averages) | ||||||

| Real GCP (2012 $, % Change) | Comptroller

Mayor |

2.0

1.9 |

1.8

0.9 |

1.5

0.6 |

1.2

0.5 |

1.2

0.3 |

| Payroll Jobs (Change In Thousands) | Comptroller

Mayor |

87.5

56.5 |

73.0

41.6 |

57.0

40.4 |

45.0

35.7 |

45.0

30.2 |

| Wage-Rate Growth (Percent) | Comptroller

Mayor |

2.7

2.3 |

2.3

2.9 |

1.7

2.5 |

1.5

2.6 |

1.5

2.2 |

Note: Comptroller=forecast by the NYC Comptroller’s Office. GCP=Gross City Product. Mayor=forecast by the NYC Office of Management and Budget in the January 2020 Financial Plan.

III. The FY 2021 Preliminary Budget

The FY 2021 Preliminary Budget released on January 16 shows a balanced budget of $95.30 billion. Revenues in the Preliminary Budget are $705 million higher than projected in the November Plan. Expenditures are $2.31 billion lower, driven by an increase of $2.17 billion in planned prepayment of FY 2021 debt service. The combination of higher revenues and lower expenditures closes a $3.02 billion gap projected in November.

Nearly all the revenue increases are due to re-estimates of City-funds revenues which are revised upward by $658 million from the November Plan projection, as shown in Table 6.[3] Revisions to tax revenue estimates account for about 90 percent of the increase in City-funds revenues, driven by upward revisions of $383 million in personal income tax (PIT), $200 million in tax audit, and $106 million in property tax revenues. A reduction of $244 million in real estate transaction tax revenues offsets some of these increases. On net, tax revenues are $593 million above the November Plan estimate. Tax revenues are discussed in greater detail in “Tax Revenues” beginning on page 16.

Table 6. Changes to FY 2021 City-Funds Estimates from the November 2019 Plan

| ($ in millions) | |

| Gap to be Closed – November 2019 Plan | ($3,015) |

| Revenues | |

| Tax Revenues | $593 |

| Non-Tax Revenues | 59 |

| Revenues From Citywide Savings Program | 6 |

| Total Revenue Changes | $658 |

| Expenditures | |

| Agency Expenditures | $161 |

| Collective Bargaining Adjustments | 85 |

| Pension Contributions | (174) |

| Miscellaneous Budget | (3) |

| Savings From Citywide Savings Program | (252) |

| Total Expenditure Changes | ($183) |

| Gap To Be Closed Before Prepayments | ($2,174) |

| FY 2020 Prepayment of FY 2021 Debt Service | $2,174 |

| Gap to be Closed – January 2020 Financial Plan | $0 |

FY 2021 City-funds expenditures before accounting for the reduction in debt service from FY 2020 prepayments show a net decrease of $183 million from the November Plan. This reduction stems largely from a $174 million decrease in pension contributions and spending reductions of $252 million in the citywide savings plan (CSP). The reduction in pension contributions reflects a change in the methodology for funding the guaranteed annual returns on the Tax Deferred Annuity (TDA) 403(b) funds of the Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) and the Board of Education Retirement System (BERS). As discussed in greater detail in “Pensions” beginning on page 32, the guaranteed TDA returns which were previously funded as annual expenses will now be deducted from pension investment earnings of TRS and BERS, resulting in lower pension contributions.

Net of spending reductions in the CSP, agency expenditures are $161 million above the November Plan. The addition of funding for the Fair Fares program in FY 2021 accounts for $106 million of the increase. The November Plan included funding for the Fair Fare program in FY 2020 only. While the January Plan adds $106 million for the Fair Fare program in FY 2021, the program remains unfunded in the outyears. The remaining $56 million increase reflects mainly spending re-estimates spread across different agencies.

In addition, the City has increased its estimates of collective bargaining cost by $85 million to reflect the recent tentative agreements between the City and the Uniformed Officers’ Coalition (UOC) and the Professional Staff Congress (PSC). The City had previously funded wage increases for all City employees based on the District Council 37 (DC 37) agreement. The terms of the tentative agreement reached with the UOC establishes the Uniformed pattern and cost an additional $75 million above the DC 37 pattern. The terms of the PSC contract reflect modifications, which while conforming to the general pattern of the DC 37 contract, result in an additional cost of $10 million in FY 2021.

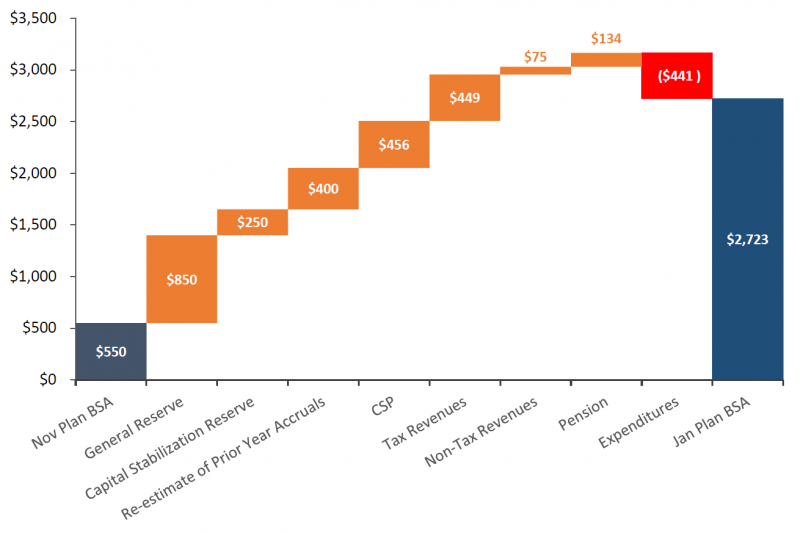

FY 2020 Budget Stabilization Account (BSA)

Since the November Plan, the City has recognized a net $2.17 billion of additional resources in the FY 2020 budget. Because these resources are not required to balance the current fiscal year’s budget, they are used to increase the FY 2020 Budget Stabilization Account, bringing the total FY 2020 BSA to $2.72 billion. The BSA will be used to prepay $2.55 billion of Transitional Finance Authority (TFA) and $173 million of general obligation (G.O.) debt service. As shown in Chart 7 on page 13, these additional resources are the result of:

- A reduction of $850 million in the FY 2020 General Reserve

- The elimination of the $250 million FY 2020 Capital Stabilization Reserve

- A net savings of $400 million from adjustments to prior-year receivables and payables estimates

- A new round of CSP with projected FY 2020 savings of $456 million

- An increase of $449 million in tax revenues

- An increase of $75 million in non-tax revenues

- An reduction of $134 million in pension contributions, less

- Additional City-funds spending of $441 million

Chart 7. The January Plan Increases the BSA by $2.17 Billion

($ in millions)

Citywide Savings Program (CSP)

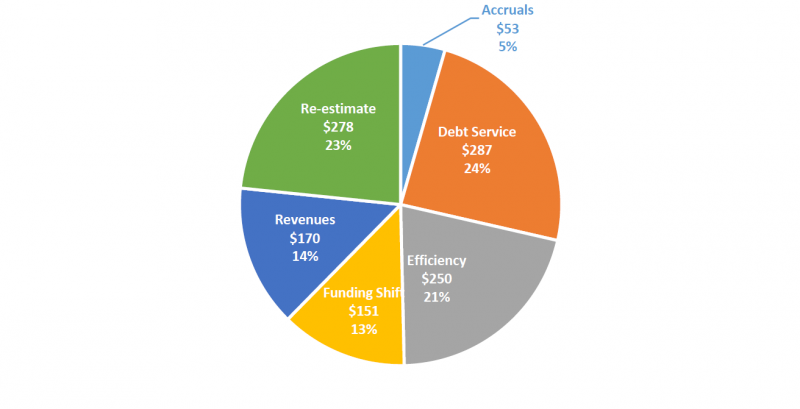

The January 2020 Plan includes another round of CSP that is estimated to provide budget relief of $456 million in FY 2020, $259 million in FY 2021, $183 million in FY 2022, $203 million in FY 2023, and $235 million in FY 2024. Expenditure re-estimates, debt service savings, funding shifts, and additional revenues make up 87 percent of the combined FY 2020 – FY 2021 budget relief. Most of the additional revenues are from Federal reimbursement for prior-year expenditures including $100 million in prior-year Medicaid reimbursement and $11 million in unanticipated reimbursement for police protective services for the United Nations General Assembly. Efficiency initiatives account for about 8 percent of the combined savings, with anticipated personal services (PS) savings from reducing the absent teacher reserve (ATR) pool by permanently placing teachers in schools and other personal services savings accounting for $39 million of the $54 million in efficiency initiatives savings.

With the current round of CSP, estimated budget relief over the Plan period now totals $2.36 billion. The combined savings in FY 2020 and FY 2021 total $1.19 billon. As shown in Chart 8, debt service savings, re-estimates and efficiency initiatives account for about 68 percent of the combined FY 2020 and FY 2021 savings.

Chart 8. Combined FY 2020 and FY 2021 Citywide Savings Program

($ in millions)

Risks and Offsets

As Table 7 shows, the Comptroller’s Office analysis of the January Plan shows net additional resources in each year of the Plan, ranging from a low of $29 million in FY 2021 to a high of $707 million in FY 2024. The additional resources in FY 2020 are driven by both the Comptroller’s Office’s tax revenue forecast, which is higher than the City’s projection by $281 million, and the Comptroller’s Office’s assumption that the $300 million in the General Reserve will be available for budget relief in the current fiscal year. In the outyears, the additional resources identified by the Comptroller’s Office stem primarily from higher tax revenue forecasts in each year of the Plan, beginning at $520 million in FY 2021 and growing to $1.83 billion by FY 2024. (See “Comptroller Projections, FY 2020 – FY 2024” beginning on page 17).

Net risks to the City’s expenditure estimates offset some of the gains from the higher revenue forecast in the outyears. These risks stem primarily from assumptions of overtime spending and shortfalls in funding for charter school tuition, Carter cases, pupil transportation, homeless shelters and the Fair Fares initiative. Despite increases to the overtime budget in the current Plan, the Plan’s assumptions are still significantly below recent spending patterns. The Comptroller’s Office’s analysis indicates that overtime could be above Plan by $258 million in FY 2020, $262 million in FY 2021, and $150 million in each of the outyears of the Plan.

As discussed in “Department of Education” beginning on page 35, the department faces significant risks from underfunding of State-mandated charter school tuition payments, special education Carter cases, pupil transportation, and optimistic estimates of Medicaid reimbursement for special education services. Together these risks sum to $70 million in FY 2020, $370 million in FY 2021, $554 million in FY 2022, $782 million in FY 2023, and $929 million in FY 2024.

The January Financial Plan adds $106 million to fund the Fair Fares initiative in FY 2021 but leaves the program unfunded in the outyears. Based on participation rate to date, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that spending on the program could be $50 million less than the $106 million funding for the program in FY 2020. However, the Comptroller’s Office expects participation rate to ramp up in response to outreach by the City. As a result, the Office expects the full $106 million for the program to be expended in FY 2021 and projects annual risks of $200 million in FY 2022 through FY 2024 due to the absence of funding for this program.

Funding for shelter operations is projected to drop by almost $50 million in FY 2021. However, as discussed in “Homeless Services” beginning on page 36, there is no evidence to support a reversal in the trend of shelter operations spending. As such, the Comptroller’s Office is projecting risks of $49 million annually beginning in FY 2021 to the shelter operations budget.

Projected underspending for public assistance (PA) due to declining caseloads, pre-K special education savings and lower than projected variable rate demand bond (VRDB) interest provide some offsets against the expenditure risks discussed above. The Comptroller’s Office projects PA savings of $30 million annually over the Plan period, pre-K special education underspending of $50 million in each year of the Plan, and VRDB interest savings of $60 million in FY 2020 and $75 million in each of the outyears of the Plan.

Overall, the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the Plan indicates that the City could end FY 2020 and FY 2021 with budget surpluses of $459 million and $29 million, respectively. In the outyears, the Comptroller’s Office analysis shows smaller gaps of $2.00 billion, $2.22 billion and $1.95 billion in FY 2022 through FY 2024, respectively.

Table 7. Risks and Offsets to the January 2020 Financial Plan

($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap)

| FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City Stated Gap | $0 | $0 | ($2,433) | ($2,686) | ($2,659) |

| Tax Revenues | |||||

| Property Tax | $150 | $232 | $784 | $1,346 | $2,028 |

| Personal Income Tax | 148 | 146 | 60 | (78) | (215) |

| Business Taxes | (54) | (118) | (73) | (25) | (1) |

| Sales Tax | (24) | 17 | (22) | (69) | (144) |

| Real Estate Transaction Taxes | 61 | 243 | 284 | 121 | 10 |

| Audit | 0 | 0 | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| Subtotal Tax Revenues | $281 | $520 | $1,187 | $1,449 | $1,832 |

| Fines | 16 | 35 | 48 | 48 | 48 |

| Total Revenues | $297 | $555 | $1,235 | $1,497 | $1,880 |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Overtime | ($258) | ($262) | ($150) | ($150) | ($150) |

| Charter School Tuition | 0 | (150) | (334) | (562) | (709) |

| Carter Cases | 0 | (125) | (125) | (125) | (125) |

| Pupil Transportation | (50) | (75) | (75) | (75) | (75) |

| Homeless Shelters | 0 | (49) | (49) | (49) | (49) |

| Fair Fares | 50 | 0 | (200) | (200) | (200) |

| DOE Medicaid Reimbursement | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) |

| Pre-K Special Education | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Public Assistance | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| VRDB Interest Savings | 60 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 |

| General Reserve | 300 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | $162 | ($526) | ($798) | ($1,026) | ($1,173) |

| Total (Risks)/Offsets | $459 | $29 | $437 | $471 | $707 |

| Restated (Gap)/Surplus | $459 | $29 | ($1,996) | ($2,215) | ($1,952) |

Revenue Analysis

Total revenues in the January Plan are estimated to grow by $6.40 billion over the forecast period, from $95.43 billion in FY 2020 to $101.83 billion in FY 2024. City-funds revenues are projected to increase from $69.87 billion in FY 2020 to $76.56 billion in FY 2024. These projections reflect the City’s assumption of moderate and slowing growth in the local and national economies over the Plan period. Overall tax revenue is projected to grow by 4.6 percent in FY 2020, slightly higher than the previous year’s rate of 4.0 percent. Growth is expected to be driven primarily by property tax revenue, which is expected to rise by 7.0 percent, while non property tax revenue is expected to increase only moderately by 2.7 percent. However, the near term boost provided by strong growth in property taxes is expected to dissipate in the outer years of the Plan period as the effects of the strong phase-ins in assessments of market values that occurred in FY 2015 – FY 2019 begin to subside. As a result, overall tax revenues are expected to increase only moderately in FY 2021 – FY 2024, by 2.6 percent on average.

Miscellaneous revenues, excluding intra-City revenues, are projected to drop 9.2 percent in FY 2020 to $5.42 billion. This projection reflects the City’s anticipation of a decline in non-recurring revenues such as proceeds from the City’s asset sales and refunds and restitutions, which boosted FY 2019 revenues. The City projects miscellaneous revenue will decline further to $5.23 billion in FY 2021 and remain at this level through FY 2024. A fuller discussion of miscellaneous revenues begins on page 21.

The January Plan reflects $23.83 billion of Federal and State aid for FY 2020, representing about 25 percent of the City’s overall revenue projections. Over the outyears of the Plan, Federal and State grants are projected to decline to $22.92 billion in FY 2021 and then recover over the latter years of the Plan to reach $23.74 billion by FY 2024. Federal support would fall from $8.16 billion in FY 2020 to $7.11 billion in FY 2021 before stabilizing at about $7 billion annually thereafter, mainly due to the winding down of Sandy-related reimbursements and more conservative assumptions of certain Federal grants in the outyears. Meanwhile, State aid is projected to rise from $15.67 billion in FY 2020 to $16.77 billion by FY 2024, at an average annual growth of 1.7 percent, driven primarily by the City’s expectation of school aid increases. See the section “Federal and State Aid” beginning on page 22.

Tax Revenues

Revisions since the November Financial Plan, FY 2020 – FY 2024

The City increased projections for almost all tax revenue sources throughout the January Plan period as shown on Table 8 on page 17. The most significant upward revision was for the PIT, which was increased in each year of the Plan, with revisions increasing to over half a billion dollars by FY 2024. This revision largely reflects stronger assumptions for the non-withheld components of PIT, while the forecast for wage rate growth and withholding is largely unchanged. In addition to PIT, property and sales taxes estimates were also revised upwards in each year of the Plan based on higher collection data and the release of the FY 2020 – FY 2021 tentative roll. Collectively, the forecast for overall business taxes (GCT, UBT and Banking) was increased, although the underlying trends for the three business taxes differed sharply; large upward revisions in GCT offset lower estimates for the other two business taxes. Significant downward revisions to the real estate transaction tax revenues in each year of the Plan offset some of these increases. Smaller revisions occurred in the remaining taxes.

Table 8. Revisions to the City’s Tax Revenue Assumptions

January 2020 Plan vs. November 2019 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| November 2019 Financial Plan | $63,903 | $65,021 | $67,229 | $69,120 | $70,632 |

| Revisions: | |||||

| Property Tax | $50 | $93 | $108 | $128 | $76 |

| Personal Income (PIT) | 118 | 383 | 444 | 517 | 642 |

| Business | 236 | 50 | 41 | 67 | 54 |

| Sales | 63 | 67 | 72 | 74 | 44 |

| Real-Estate Transactions | (76) | (244) | (314) | (316) | (141) |

| All Other | 58 | 44 | 35 | 20 | 8 |

| Tax Audit | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | $449 | $593 | $386 | $490 | $683 |

| January 2020 Financial Plan – Total | $64,352 | $65,614 | $67,615 | $69,610 | $71,315 |

Comptroller Projections, FY 2020 – FY 2024

The main differences between the Comptroller’s and the City’s projections for tax revenues are shown in Tables 9 and 10. Overall the Comptroller’s forecast of 3.1 percent average annual growth over the Plan period is slightly higher than the City’s 2.6 percent rate.[4] This difference is driven almost entirely by the Comptroller’s higher forecast for property taxes. Both the Comptroller and the City anticipate a slowdown in the growth rate for this revenue, but the City’s projection for each of the outyears FY 2022-FY 2024 is more than 1.5 percentage points lower compared to the Comptroller’s. As a result, by 2024 property tax revenues could be $2 billion higher than the City projects. The forecasts for the other taxes are relatively similar, with the exception of audit revenue where the City assumes a much steeper decline in FY 2022 compared to the Comptroller’s Office. A more detailed discussion of the individual taxes follows.

Table 9. Risks and Offsets to the City’s Tax Revenue Projections

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 |

| Property | $150 | $232 | $784 | $1,346 | $2,028 |

| PIT | 148 | 146 | 60 | (78) | (215) |

| Business | (54) | (118) | (73) | (25) | (1) |

| Sales | (24) | 17 | (22) | (69) | (144) |

| Real Estate Transaction | 61 | 243 | 284 | 121 | 10 |

| Audit | 0 | 0 | 154 | 154 | 154 |

| Total | $281 | $520 | $1,187 | $1,449 | $1,832 |

Table 10. Tax Revenue Forecast, Growth Rates

| FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FYs 2020 – 24 Average Annual Growth |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Property | ||||||

| Mayor | 7.0% | 4.5% | 4.0% | 3.0% | 2.1% | 3.4% |

| Comptroller | 7.5% | 4.8% | 5.7% | 4.6% | 4.0% | 4.8% |

| PIT | ||||||

| Mayor | 2.9% | 0.6% | 3.5% | 3.6% | 3.5% | 2.8% |

| Comptroller | 4.0% | 0.5% | 2.9% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.1% |

| Business | ||||||

| Mayor | 1.4% | (3.9%) | 1.8% | 1.8% | 0.7% | 0.1% |

| Comptroller | 0.5% | (4.9%) | 2.6% | 2.6% | 1.1% | 0.3% |

| Sales | ||||||

| Mayor | 7.0% | 3.2% | 3.5% | 3.2% | 3.4% | 3.3% |

| Comptroller | 6.7% | 3.7% | 3.1% | 2.7% | 2.6% | 3.0% |

| Real Estate Transactions | ||||||

| Mayor | (10.1%) | (6.3%) | (0.3%) | 2.8% | 3.1% | (0.2%) |

| Comptroller | (7.8%) | 1.4% | 1.4% | (4.0%) | (1.7%) | (0.8%) |

| All Other | ||||||

| Mayor | (1.0%) | 1.5% | 1.8% | 1.5% | 1.9% | 1.7% |

| Comptroller | (1.0%) | 1.5% | 1.8% | 1.5% | 1.9% | 1.7% |

| Audit | ||||||

| Mayor | 22.2% | (7.8%) | (21.7%) | 0.0% | 0.0% | (7.8%) |

| Comptroller | 22.2% | (7.8%) | (5.0%) | 0.0% | 0.0% | (3.3%) |

| Total Tax with Audit | ||||||

| Mayor | 4.6% | 2.0% | 3.0% | 3.0% | 2.4% | 2.6% |

| Comptroller | 5.1% | 2.3% | 4.0% | 3.3% | 2.9% | 3.1% |

Property Taxes

The Comptroller’s Office forecasts slowing but continued growth throughout the Plan period. Property tax revenue is estimated to grow on average by 4.8 percent annually from FY 2020 to FY 2024. The slowdown is attributable to a complex mix of changes in forecast increases in assessed values, the phase-in of assessed value increases that have already occurred, and conservative estimates for the construction of new commercial and residential property.

The City projects comparatively slower growth for the real property tax over the Plan period, stemming from a difference in the forecast for reserves, larger predicted decreases in billable values from the tentative to the final roll, and slower growth of billable value. The City’s projections show reserves jumping to almost 7 percent of the levy in FY 2021 – FY 2024 from 6.4 percent last year. The Comptroller’s Office’s assumption of a more steady reserve-to-levy ratio results in a forecast for reserves that is $200 million to $300 million lower than the City’s estimate. The combined effect of lower reserves and slightly higher assumptions for property tax growth results in property tax revenue exceeding the City’s projections by $2.0 billion by the end of the Plan period.

Real Estate Transaction Taxes

The Comptroller’s Office projects a 7.8 percent decline in the combined revenues from real estate-related taxes (the real property transfer tax and mortgage recording tax) in FY 2020, to $2.44 billion, which is still approximately $61 million above the City’s latest forecast of $2.38 billion. In the outyears, the Comptroller’s Office projections are above the City’s by $243 million in FY 2021, $284 million in FY 2022, $121 million in FY 2023, and $10 million in FY 2024. The Comptroller’s Office forecasts real estate-related taxes to stay relatively flat over the plan period with slow growth during the first two fiscal years (1.4 percent annually) and decline afterwards (by 4 percent in FY 2023 followed by 1.7 percent in FY 2024). The City forecasts a decline in FY 2021 and FY 2022 by 6.3 percent and 0.3 percent respectively followed by growth in outyears.

Residential sales including 1- to 3-family homes, co-ops, and condos priced under $2 million, have shown declines in 2019 as a result of the loss of SALT deductions and lowered limits for interest deductions on residential mortgages enacted in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. This downward trend is expected to lower forecasts in FY 2020 compared to FY 2019. For the outyears, continued growth in NYC wages and employment are expected to support growths in both the commercial and residential real estate markets, with expected increases in interest rates in the later years of the Plan period offsetting the growth.

There are potential risks to the forecast of real estate-related taxes. We do not have enough evidence yet on the potential impact on prices and demand for high-end residential properties due to the supplemental tax on the sales of residential real properties priced above $2 million (the “mansion tax”). Finally, sales of residential rental buildings may be impacted by changes in rent control laws that limit owners’ ability to raise rents.

Personal Income Taxes

The City significantly revised its forecast for PIT in the January Plan, primarily a reflection of higher estimates for the non-withheld components of PIT related to capital gains realizations. The Comptroller’s November forecast had anticipated higher non-withheld revenues across the Plan years. As a result, the two forecasts are now very similar. Both forecasts anticipate that slowing job gains will result in moderate PIT growth in the out years of the plan. However, the growth pattern is slightly different with the Comptroller’s Office assuming higher near-term strength and conversely lower growth in the later years, as shown in Table 10.

With the local and national economy showing continued growth momentum, the greatest near term uncertainty for the PIT forecast is likely related to the containment of the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus and the outcome of the presidential election in November and its potential impact on the stock market and capital gains realizations. Long term the upcoming decennial census will provide more robust data on the City’s population and will need to be monitored closely to see if it confirms recent estimates of a decline in the City’s population.

Business Income Taxes

The forecast for the business taxes (General Corporation Tax and Unincorporated Business Tax), is perhaps the most uncertain of all revenues given significant changes that occurred recently in both Federal and local tax law.[5]

GCT tax revenue jumped by more than 23 percent in FY 2019. This increase was likely a response to the lowering of the Federal corporate tax rate which caused firms to shift income into tax year 2018 to take advantage of this lower rate. In addition, GCT revenue may have also been boosted by conversions of unincorporated business to incorporated business that were also triggered by the new tax law.

With all the changes in law that occurred, Federal and local tax departments are still issuing guidance on the newly enacted and complex provisions of these laws. As a result of this uncertainty, firms’ ultimate tax liability for these years could change. While the City raised its estimates for GCT throughout the Plan based on current collections, due to the uncertainty of the tax liability, our assessment is that more caution is warranted in the outyears due to the possibility of recent overpayments.

Sales Tax

The City projects sales tax collections to reach $8.35 billion in FY 2020, a 7.0 percent increase from last fiscal year, and the strongest growth rate in nearly a decade. The Comptroller’s Office forecast of 6.7 percent is very similar, resulting in a minor $24 million difference in FY 2020. Policy factors also are a determinant factor driving this strong growth, in addition to the continued expansion in the local economy and a robust tourism sector.[6] The end of the State mandated STARC intercepts, which reduced City sales tax revenue by $150 million in FY 2019, and $450 million in FY 2016 – FY 2018, provides a one-time boost of nearly 2 percentage points to FY 2020’s growth.[7]

Both the City and the Comptroller’s Office expect growth in sales tax revenue to abate in the outyears of the Plan, in line with a projected slowdown in economic growth and gradual deceleration in employment and wage growth. For FY 2021, the Comptroller forecasts growth in sales tax collection of 3.7 percent, a slightly higher rate than the City’s 3.2 percent projection, resulting in a small offset of $17 million.

The Comptroller’s Office projects sales tax revenue growth to slow further in the outyears, averaging 2.6 percent annually in FY 2022 – FY 2024, compared to a 3.3 percent average growth reflected in the Plan over the same period. In FY 2022 – FY 2024 the Comptroller’s Office forecasts revenues from sales tax to be below OMB’s projection by about $22 million, $69 million and $144 million respectively.

Audit Revenues

The City’s forecast assumes that audit collections will decline by more than 21 percent from $921 million in FY 2021 to only $721 million in FY 2022 and the remainder of the Plan. The Comptroller’s forecast, while recognizing the volatility in individual audit collections, assumes that overall tax revenues should remain more closely in line with the $1 billion long term average of the past 10 years. As a result, the City could collect at least $150 million more in each year from FY 2022 – FY 2024.

Hudson Yards Tax Equivalency Payments (TEPS) and Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT)

Under the Hudson Yards financing structure, the City makes annual tax equivalency payments (TEPS) for property taxes of newly developed residential and hotel properties in Hudson Yards. These TEPS and other revenue sources cover debt and other project costs of the HYIC. In turn, surplus revenues from TEPS and these other sources that exceed project costs can be returned to the general fund via PILOT payments from HYIC to the City.

In the current Financial Plan, the City shows TEP payments flat throughout the Plan years at approximately $150 million. This flat projection for TEP revenues is unlikely for several reasons: 1) The City’s own assumptions on market value growth suggests that TEP related property tax payments will increase over time; 2) expiring abatements for existing residential properties also suggest that TEP payments will increase; and 3) the addition of newly constructed properties coming on line will also result in additional TEP payments. In fact, the City’s own previous projections for TEP revenues indicate TEP revenues growing from $143 million in 2020 to over $220 million by 2024.

If these growing TEP payments do not coincide with increasing HYIC PILOT payments to the City, this would pose a risk to the City’s budget given that TEPs are expenditures in the general fund.

Miscellaneous Revenues

In the January 2020 Financial Plan, the City raised its FY 2020 miscellaneous revenue projection by a net $118 million, to $5.42 billion. About $42 million of this increase reflects revenue initiatives included in the Citywide Savings Plan. The revised miscellaneous revenue forecast nonetheless represents a 9.2 percent decline from FY 2019. This is mostly due to lower projected non-recurring revenues such as asset sales and restitutions in FY 2020.

Table 11 shows changes in the FY 2020 miscellaneous revenue projection totaling $118 million since the November 2019 Plan. Excluding water and sewer revenues which are reimbursements from the Water Board for the operation and maintenance of the water delivery and sewer systems, the January Plan increases the other miscellaneous revenue categories by a combined $66 million in FY 2020.

Table 11 Changes in FY 2020 Estimates

January 2020 Plan vs. November 2019 Plan

| ($ in millions) | November | January | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Licenses, Permits & Franchises | $760 | $767 | $7 |

| Interest Income | 155 | 155 | 0 |

| Charges for Services | 1,056 | 1,059 | 3 |

| Water and Sewer Charges | 1,537 | 1,589 | 52 |

| Rental Income | 256 | 258 | 2 |

| Fines and Forfeitures | 1,135 | 1,182 | 47 |

| Other Miscellaneous | 404 | 411 | $7 |

| Total | $5,303 | $5,421 | $118 |

Note: Water and sewer revenues collected by the Water Board from dedicated water and sewer charges represent reimbursements for operation and maintenance of the water delivery and sewer systems and therefore are not available for general operating purposes.

Projected revenues from licenses, permits & franchises increased by $7 million. The Department of Buildings (DOB) is expected to realize an additional $6 million in revenues from building permits due to an increase in the volume of after-hours variance permits. Charges for services increased by $3 million due to a re-estimate of fee revenues including $1.9 million in tax credit fees from the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), $1.9 million in DOB facades and electric inspection fees, and $2 million in credit card convenience fees. These increases were partially offset by a $4 million decrease in City register fees. The forecast for rental income increased by $2 million mostly due to an increase in projected rental income from the HPD portfolio.

Projections for fines and forfeitures increased by $47 million. This includes a $22.2 million net increase in parking fine revenues resulting from greater than expected year-to-date summonses, slightly offset by a downward revenue adjustment to reflect a delay in the implementation of increased alternate side parking fines. Estimated fine revenues from the DOB increased by $11 million reflecting increases from elevator, work without a permit, and hazardous violations. Revenues from court fines increased by $8.8 million of which $7 million are one-time revenues previously held in escrow accounts for partial payments of court fines from FY 2018 and FY 2019. Revenues from health tribunal summonses and from real property transfer tax (RPTT) late-payment penalties increased by $3.7 million and $1.1 million respectively.

The category “Other Miscellaneous” which includes City asset sales, restitution and other non-recurring revenues, increased by $7 million, including $1.6 million in restitution, $1.8 million in additional employee health contributions, $1.9 million in asset sales and $1 million in additional HPD mortgage revenue.

Changes to the miscellaneous revenue outyear forecasts were minor. Total Miscellaneous revenue is expected to decline by $187 million in FY 2021 to $5.2 billion and remain at this level throughout the remainder of the Plan period.

Although the January Plan increases fine revenue estimates throughout the Plan period, based on recent collection trend, the Comptroller’s Office expects revenues from fines to be above the City’s forecast in each of FYs 2020 – 2024 by $16 million in FY 2020, $35 million in FY 2021 and $48 million in each of FYs 2022 – 2024.

Federal and State Aid

The January Financial Plan projects total Federal and State aid of $23.83 billion in FY 2020, supporting nearly 25 percent of the City’s expenditure budget. Compared with the November Plan, the City has recognized an increase of $331 million in the current year comprised of $145 million in Federal aid and $186 million in State grants. A significant portion of the increase is reflected in education aid totaling about $91 million, mostly from State reimbursement for transportation ($36 million) and special education ($34 million) and certain Federal aid adjustments ($17 million). The January Modification also recognizes $106 million in additional Community Development Block Grant for Disaster Recovery and other Sandy-related reimbursement, bringing the new total to $334 million in the current year. The remainder of the FY 2020 increase is mainly comprised of health and welfare grants totaling $99 million, including $60 million for early intervention and $10 million each for secure detention and the Close to Home initiative.

In the FY 2021 Preliminary Budget, the City assumes $22.92 billion in Federal and State assistance, reflecting a modest increase of $45 million since the November Plan. The increase mainly consists of extension of certain education aid and Sandy-related reimbursements from the current year. Federal and State grants would support about 24 percent of the expense budget in FY 2021, representing a slight decrease from the current year due to a decline in Sandy-related reimbursements and more conservative estimates of certain Federal grants.

Over the remainder of the Plan, Federal and State grants are projected to rise to $23.27 billion in FY 2022, $23.7 billion in FY 2023 and $23.74 billion in FY 2024, averaging annual growth of slightly over 1 percent, driven primarily by expectation of State education aid increases of about 2.5 percent annually. Assuming these assumptions hold true, Federal and State support for the City’s expense budget would decline from about 25 percent in FY 2020 to 23 percent by FY 2024.

State Executive Budget

Governor Andrew Cuomo unveiled his Executive Budget for State fiscal year (SFY) 2020 – 2021 on January 21, 2020. The plan aims to close a projected general fund budget gap of $7.0 billion, including $890 million in savings announced in the November Mid-year Update. About one-third of the gap relates to higher than forecast Medicaid spending in the current year.

The City estimates that in total, the State budget as proposed could have a negative impact on the City’s Financial Plan of more than $1.3 billion over FY 2020 and FY 2021, as shown in Table 12.

Table 12 Potential Impact of Proposed 2020 – 21 State Budget

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | Total Two-Year Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| School Aid | |||

| Formula Aid Shortfall | $3 | ($136) | ($133) |

| Subtotal School Aid | $3 | ($136) | ($133) |

| Cost Shifts | |||

| Medicaid | ($100) | ($1,005) | ($1,105) |

| Family Assistance | (34) | (68) | (102) |

| Child Welfare | (7) | (14) | (21) |

| Subtotal Cost Shifts | ($141) | ($1,087) | ($1,228) |

| Hudson River Park Tow Pound | – | ($27) | ($27) |

| Total Impact | ($138) | ($1,250) | ($1,388) |

Source: NYC Office of Management and Budget

Medicaid

Under the State’s Global Cap, the State’s share of Medicaid spending is held to the 10-year average of the medical care consumer price index, which currently provides for about 3.0 percent annual growth. However, in SFY 2018–2019, higher than anticipated Medicaid expenses created a structural imbalance in the Global Cap, leading to a $1.7 billion deferral in Medicaid payments from the final days of SFY 2018-19 to the beginning of SFY 2019-20.[8] In November 2019, the State reported that the deferral contributed to a projected $4 billion Medicaid imbalance in the current year and a $3.1 billion imbalance in SFY 2020–2021.

To address the Medicaid imbalance over the State’s financial plan, the Governor reconvened the Medicaid Redesign Team (MRT II), a task force of health care industry experts. The task force has been charged with identifying $2.5 billion in Medicaid savings for SFY 2020–2021 and reducing the long-term Medicaid growth trend to the Global Cap indexed rate.

Governor Cuomo also proposed significant changes to local governments’ contribution to Medicaid funding. Under the proposal, local governments would be required to fund local Medicaid spending growth above 3 percent, however, if local governments do not comply with the State’s 2 percent property tax levy cap, they would be required to fund all local growth in Medicaid. The proposal would apply to New York City, although the City is not subject to the property tax cap. The Governor’s proposal would take effect in SFY 2020–2021 and provide projected annual savings of $150 million.

Under the State’s current local Medicaid growth cap, local governments’ Medicaid contributions have been frozen since calendar year 2015. As of FY 2021, the City’s capped annual contribution is $4.953 billion, net of enhanced Federal Medicaid Assistance Percentage (FMAP). The State projects that the annual savings from the local share growth cap for New York City would grow by $221 million from $1.98 billion in SFY 2019-20 to $2.20 billion in SFY 2020–2021.[9]

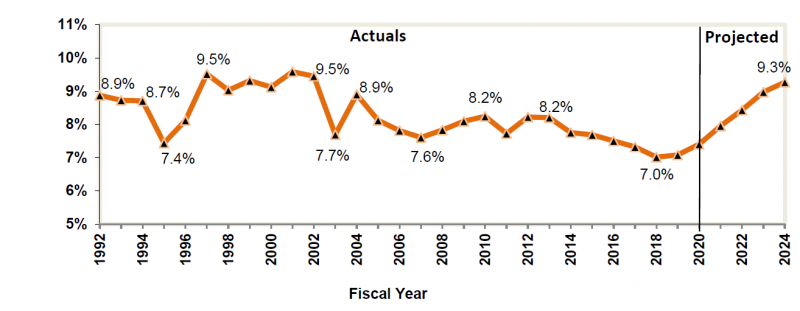

Based on recent trends, New York City would be unlikely to meet either the property tax levy cap or the 3 percent growth provision. Over the last five fiscal years, the City’s property tax levy has grown at an average annual rate of 7.0 percent, well above allowable growth under the cap that currently applies outside the City. The State’s property tax levy cap limits annual growth to the lesser of 2 percent or the rate of inflation, plus certain exclusions, including growth attributed to new development. Similarly, in the last two years, the non-Federal share of Medicaid spending in New York City has exceeded 3 percent annual growth. According to State Department of Health data, State and local Medicaid spending in the City grew 7.0 percent in SFY 2018–2019 from $16.2 billion to $17.3 billion.[10]

The City assumes that if Medicaid costs grow at similar rate as in the prior two years, at about 7 percent annually, the State’s proposal would lead to a risk of $518 million for the local share of the spending increase. Further, based on the City’s interpretation of a separate proposal, the State has the option to terminate the provision of enhanced FMAP savings to the City, which would raise the total Medicaid cost impact to $1.1 billion over FY 2020 and FY 2021.

In recent years, the State has assumed greater administrative responsibilities from New York City and the counties, leaving the City with limited control over the program’s costs. While the City maintains a role in determining eligibility for certain categories of enrollees, including managed long-term care recipients, the City cannot control major cost drivers of the program, such as eligibility rules, service levels, and reimbursement rates.

School Aid

As proposed, the State Budget would provide $11.6 billion in formula-based school aid to New York City in FY 2021, a 2.0 percent increase from the current year. Proposed school aid is $136 million less than assumed in the City’s Financial Plan for FY 2021, before accounting for $250 million in statewide funding set aside for additional Foundation Aid for high-need districts and competitive grants. The State indicates that, if distributed, the City would receive an additional $97 million in aid, which could potentially reduce the projected school aid shortfall of $136 million.

The proposed State Budget would also consolidate 10 other formula-based categories of school aid into Foundation Aid. These aid categories, which include special services and library, software and textbook aid, provide $309 million in funding to New York City in the current school year. By combining these categories into Foundation Aid, the City’s share of Foundation Aid would appear to grow from $8.1 billion in the current year to $8.6 billion next year, thereby artificially shrinking the gap between proposed funding and the amount owed to the City if Foundation Aid were fully funded.

In addition, the Executive Budget would cap reimbursements for transportation aid based on enrollment growth and inflation beginning in FY 2022, add a new tier of building aid for projects approved beginning in the 2020-21 school year, and exclude the reissuance of surrendered, revoked, or terminated charters from the New York City charter school cap. In 2015, a similar provision allowed an additional 22 charters to be reissued to charter schools that had lost their charter before July 1, 2015. The Governor’s proposal would enable about 17 charter schools that have closed since July 1, 2015 to reopen without having to raise the cap. As of early 2019, New York City reached the State-imposed limit on charters and therefore no additional charter schools are able to be authorized in the City.

The State-mandated tuition payment from New York City to charter schools is also set to rise steeply in the coming years, posing risks of $150 million in FY 2021, $334 million in FY 2022, and $562 million in FY 2023 (See discussion in “Department of Education” beginning on page 35).

Other Costs to the City

The Governor’s proposed budget would further lower State reimbursement for Family and Emergency Assistance benefits utilizing the Federal Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) block grant. State reimbursement would fall to 85 percent, following a reduction from 100 percent to 90 percent last year. This proposal would reduce funding to the City by an additional $68 million annually, increasing City costs primarily in the areas of homeless family shelter operations and cash assistance.

The Governor has also proposed raising the statewide child welfare threshold, which requires localities to meet a dollar threshold for child welfare spending before receiving 62 percent State reimbursement for certain services. The current statewide threshold of $342 million, which has not been increased since 2009, would increase to $382 million. Based on the City’s current allocation of the statewide threshold, the proposal could require New York City to spend an additional $23 million before being eligible to receive 62 percent State reimbursement.[11] Therefore, the proposal could cost New York City $14 million annually, beginning in FY 2021.

Another proposal in the State budget would subject the City to a $12 million penalty if the City does not vacate Pier 76 on the Hudson River by the end of calendar year 2020. The pier is currently used as a police tow pound. Beginning February 1, 2021, the City would be obligated to pay $3 million in monthly “rent” to the Hudson River Park Trust until the tow pound is moved, which could result in a total cost of $27 million in FY 2021. As of the beginning of 2020, a location had not yet been identified for the tow pound.

The proposed State budget also includes an extension of two provisions that pose further risks to the City. One proposal would extend Executive authority granted in the past three years to propose a plan to reduce spending if Federal Medicaid revenues are cut by $850 million, or if non-Medicaid Federal revenues are cut by $850 million in SFYs 2020-21 and 2021-22. The Legislature would have 90 days to propose and adopt an alternative plan.

The second provision would extend authority to allow certain local aid payments to be uniformly reduced by up to 1 percent if the State anticipates a year-end general fund shortfall greater than $500 million in SFY 2020-21. Exempted aid categories include public assistance, reductions that would violate federal law, and payments of debt service and related expenses which the State is constitutionally or contractually obligated to pay. The legislature would have 30 days to propose an alternative plan.

Revenues

On the revenue side, for the second consecutive year, the Governor included legislation in the Executive Budget to legalize and tax the sale of cannabis. The Governor proposed a 20 percent State excise tax and a 2 percent local excise tax on sales from wholesalers to retailers. The local tax would be based on the wholesale price and the location of the retailer. However, cannabis sales would be exempt from the City and State sales tax. The State expects to begin collecting $20 million in new revenue in SFY 2020 – 2021. The Comptroller’s Office has estimated that the market for adult-use marijuana in New York City would be about $1.1 billion. Consequently, once the existing underground market transitions to the legal market, the legalization of cannabis could generate approximately $20 million per year in local excise tax for the City.

The State has also proposed reducing taxes on small businesses and farms, including a proposal to increase an existing personal income tax deduction for net business income from 5 percent to 15 percent. Small business is defined as a sole proprietor or farm business that employs one or more persons and has net business income or net farm income of less than $250,000. The City estimates that the increased deduction could reduce City personal income tax revenue by as much as $33 million annually beginning in FY 2021. However, the most recent available data shows that the existing deduction cost the State only $1.5 million in 2016.

Expenditures Analysis

Total-funds FY 2021 expenditures in the January Financial Plan are projected to remain relatively unchanged from FY 2020, declining marginally by $127 million, or about one-tenth of a percent. After adjusting for prepayments, and excluding re-estimates of prior-year accruals and reserves, FY 2021 expenditures are still relatively flat compared to FY 2020, decreasing from $97.02 billion in FY 2020 to $96.77 billion in FY 2021, a modest reduction of 0.3 percent. The drop in expenditures is driven by reductions in contractual and other than personal services expenditures, as shown in Table 13.

Table 13. FY 2020 – FY 2024 Expenditure Growth

Adjusted for Prepayments and Prior-Year Actions

| ($ in millions) | FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | Growth FYs 20-24 | Annual Growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salaries and Wages | $29,677 | $30,519 | $30,398 | $31,307 | $31,869 | 7.4% | 1.8% |

| Debt Service | 6,984 | 7,499 | 8,158 | 8,906 | 9,366 | 34.1% | 7.6% |

| Health Insurance | 6,967 | 7,379 | 8,069 | 8,756 | 9,437 | 35.5% | 7.9% |

| Other Fringe Benefits | 4,286 | 4,308 | 4,423 | 4,545 | 4,676 | 9.1% | 2.2% |

| Subtotal | $47,914 | $49,705 | $51,049 | $53,514 | $55,348 | 15.5% | 3.7% |

| Pensions | $9,719 | $9,827 | $10,310 | $10,346 | $10,000 | 2.9% | 0.7% |

| Medicaid | 5,915 | 5,915 | 5,915 | 5,915 | 5,915 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Public Assistance | 1,641 | 1,651 | 1,651 | 1,650 | 1,650 | 0.6% | 0.1% |

| J & C | 733 | 727 | 742 | 758 | 775 | 5.7% | 1.4% |

| Contractual Services | 18,339 | 16,769 | 16,861 | 16,903 | 16,856 | (8.1%) | (2.1%) |

| Other OTPS | 12,763 | 12,179 | 12,304 | 12,433 | 12,697 | (0.5%) | (0.1% ) |

| Subtotal | $49,110 | $47,067 | $47,782 | $48,006 | $47,893 | (2.5%) | (0.6%) |

| Expenditures Before Reserves and Prior-Year Re-estimates | $97,024 | $96,772 | $98,831 | $101,520 | $103,241 | 6.4% | 1.6% |

| Prior-Year Accruals Re-estimate | ($400) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | ||

| General Reserve | $300 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | ||

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | $250 | $250 | $250 | $250 | ||

| Total | $96,924 | $98,022 | $100,081 | $102,770 | $104,491 | 7.8% | 1.9% |

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

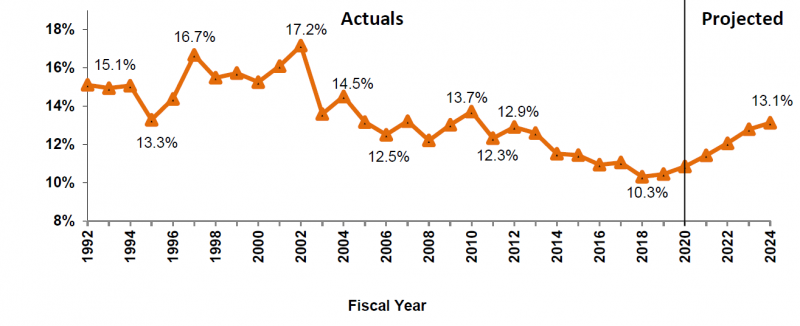

Over the Plan period, expenditures net of reserves and prior-year re-estimates are projected to grow by 6.4 percent, driven by spending on salaries and wages, debt service, health insurance, and other fringe benefits excluding pensions. The combined spending in these areas is projected to grow by 15.5 percent over the Plan period, averaging 3.7 percent annually. All other expenditures, net of the reserves and prior-year re-estimates, are projected to decline by 2.5 percent over the same period, with a projected annual average decline of 0.6 percent.

Headcount

The January 2020 Headcount Plan projects significant increases in FY 2021 and FY 2022 full-time headcount, with a very slight decline in FY 2023 and FY 2024. Full-time headcount, as shown in Table 14, is projected at 307,175 for FY 2020, rising to 308,851 in FY 2021, to 311,541 in FY 2022, then falling modestly to 311,471 in FY 2023 and remaining essentially flat in FY 2024.

Table 14. Total Funded Full-Time Year-End Headcount

January 2020 Financial Plan

| FY 2020 | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedagogical | |||||

| Dept. of Education | 122,004 | 123,968 | 126,711 | 126,711 | 126,711 |

| City University | 4,441 | 4,441 | 4,441 | 4,441 | 4,441 |

| Subtotal | 126,445 | 128,409 | 131,152 | 131,152 | 131,152 |

| Uniformed | |||||

| Police | 36,201 | 36,201 | 36,201 | 36,201 | 36,201 |

| Fire | 10,952 | 10,951 | 10,951 | 10,951 | 10,951 |

| Correction | 8,949 | 8,949 | 8,790 | 8,790 | 8,790 |

| Sanitation | 7,842 | 7,808 | 7,805 | 7,805 | 7,805 |

| Subtotal | 63,944 | 63,909 | 63,747 | 63,747 | 63,747 |

| Civilian | |||||

| Dept. of Education | 12,724 | 12,854 | 13,130 | 13,130 | 13,130 |

| City University | 1,946 | 1,946 | 1,946 | 1,946 | 1,946 |

| Police | 16,040 | 15,798 | 15,798 | 15,798 | 15,798 |

| Fire | 6,394 | 6,631 | 6,630 | 6,621 | 6,620 |

| Correction | 2,028 | 2,027 | 2,027 | 2,027 | 2,027 |

| Sanitation | 2,241 | 2,237 | 2,237 | 2,237 | 2,237 |

| Admin. for Children’s Services | 7,167 | 7,424 | 7,424 | 7,424 | 7,424 |

| Social Services | 14,577 | 14,591 | 14,591 | 14,591 | 14,591 |

| Homeless Services | 2,383 | 2,219 | 2,120 | 2,120 | 2,120 |

| Health and Mental Hygiene | 5,830 | 5,827 | 5,827 | 5,820 | 5,820 |

| Finance | 2,147 | 2,147 | 2,147 | 2,147 | 2,147 |

| Transportation | 5,560 | 5,529 | 5,534 | 5,535 | 5,537 |

| Parks and Recreation | 4,507 | 4,421 | 4,423 | 4,423 | 4,423 |

| All Other Civilians | 33,242 | 32,882 | 32,808 | 32,753 | 32,753 |

| Subtotal | 116,786 | 116,533 | 116,642 | 116,572 | 116,573 |

| Total | 307,175 | 308,851 | 311,541 | 311,471 | 311,472 |