Comments on New York City’s Preliminary Budget for Fiscal Year 2022 and Financial Plan for Fiscal Years 2021 – 2025

I. Executive Summary

Since the November Plan, there have been several positive developments which have implications for both the economic recovery and the City’s fiscal outlook. In December, Congress approved a second round of stimulus payments, renewed the Paycheck Protection Program, and extended unemployment insurance programs enacted through the CARES Act for an additional 11 weeks. In addition, the House passed a $1.9 trillion stimulus bill which, among other provisions, includes additional stimulus payments, extends the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance and Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation programs, and provides $350 billion in relief for state and local governments. Finally, vaccination efforts against COVID-19 got underway in mid-December, which should provide a boost to the economy in 2021.

However, challenges to a full economic recovery remain. New York City was hit earlier and harder by the pandemic and has experienced a disproportionate share of the impact. Despite rebounding from April lows, seasonally adjusted December private employment in New York City is more than 600,000 jobs below the pre-pandemic peak and declined by over 31,000 in the last two months of 2020. Bars and restaurants, which had reopened with limited indoor capacity, closed to indoor service in December, and consumers’ willingness to dine outdoors has been dampened by colder temperatures, snow, and more virulent virus strains. Entertainment venues such as concerts, opera, ballet, dance, Broadway, fashion shows and sporting events remain closed, although the Governor authorized the re-opening of sports and entertainment events at reduced capacity in major stadiums and arenas with a capacity of 10,000 or more, beginning February 23rd, and the opening of movie theaters at 25 percent capacity beginning March 5th. At the same time, restaurants which had resumed indoor dining on February 12th were allowed to increase indoor dining capacity by 10 percent to 35 percent on February 26th.

It was against this backdrop of the promise of an improving economy from the second stimulus bill and the rollout of vaccination against the coronavirus that the City released its $92.29 billion Preliminary FY 2022 Budget. The Preliminary Budget is balanced and closes a $3.75 billion gap projected in November. Overall, tax revenues in the FY 2022 Preliminary Budget are $1.58 billion less than projected in the November Plan. Non-property taxes for FY 2022 are projected to be $923 million more in than the November Plan, reflecting stronger income and business tax receipts than previously anticipated. However, the impact of the pandemic on property values was greater than anticipated. The 2022 tentative roll released by the Department of Finance on January 15th showed a decline of 5.2 percent in market values, with Class 2 (multi-family residential) values declining by 8.0 percent on average, and Class 4 (commercial) property values dropping by a sharper 15.8 percent, on average; Class 1 (1- to 3-family homes) property values remained relatively flat with a slight increase of 0.8 percent. As a result, property tax revenues were reduced by about $2.5 billion annually, beginning FY 2022.

A sharper decline of $5.33 billion from the November Plan in City-funds expenditures in the Preliminary FY 2022 budget offsets the drop in tax revenue and balanced the budget. More than half of the reduction in City-funds spending is from an increase of $2.75 billion in the FY 2021 Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) for the prepayment of FY 2022 debt service. The BSA is funded with the anticipated FY 2021 budget surplus, and the increase in the BSA stems primarily from an increase of $1.67 billion in tax revenues and budget relief of $869 million from a new round of the Citywide Savings Program (CSP) in the January Plan.

Net of this reduction in debt service from the additional prepayment, FY 2022 City-funds expenditures are $2.61 billion less than estimated in November, with the new round of CSP accounting for $1.34 billion of the spending reduction. The remaining reduction in spending stem primarily from a reduction of $900 million in the General Reserve, the elimination of the $250 million Capital Stabilization Reserve, and pension contribution savings of $304 million from proposed changes to actuarial assumptions and methodology. These reductions are partially offset by a $181 million increase in City-funds agency spending, including the deferral of an additional $52 million of FY 2021 retroactive and welfare payments into FY 2022 (for a total of $691 million).

The Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the January Plan has identified additional resources of $396 million in FY 2021 and risks to the budget ranging from $1.43 billion in FY 2022 to $2.61 billion in FY 2025. The additional resources in FY 2021 results from the Comptroller’s Office’s higher tax revenue forecasts which offsets the expenditure risks identified by the Office. Risks to the budget in the outyears of the Plan are driven by the Comptroller’s Office’s higher expenditure estimates, with a modestly higher tax revenue estimate mitigating some of the risks in FY 2022, and lower tax revenues adding to the expenditure risks in FY 2023 through FY 2025. As a result, the Comptroller’s Office projects an additional budget surplus of $396 million in FY 2021, but larger gaps of $1.43 billion in FY 2022, $6.44 billion in FY 2023, $6.48 billion in FY 2024, and $6.89 billion in FY 2025.

The January Plan does not reflect potential Federal budget relief from actions taken by the Biden administration. The January Plan assumes FEMA reimbursement for 75 percent of eligible expenditures; since the release of the January Plan, however, the President has signed an executive order authorizing FEMA to reimburse the entire cost of eligible COVID related spending, retroactive to spending since the onset of the pandemic. The additional reimbursement, which is estimated to provide an additional $1 billion of FEMA funding to the City, will allow the City to rescind or reduce some of the service reductions in the Plan and use the balance towards budget relief. In addition, the House passed a $1.9 trillion stimulus bill which includes $350 billion in relief to states and local governments, including a reported $5.6 billion to New York City. However, the State Executive Budget includes provisions to shift costs to the City, including the use of STAR reimbursement to offset some of the Federal relief. Since many of these cost shifts extend beyond the expiration of Federal COVID relief, the State Executive Budget if adopted as proposed, would have a negative impact on the City in the long run.

Table 1. FY 2021 – FY 2025 Financial Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | Change FYs 2021 –2025 Dollar Percent |

|

| Revenues | |||||||

| Taxes: | |||||||

| General Property Tax | $30,844 | $29,522 | $30,192 | $30,619 | $31,027 | $183 | 0.6% |

| Other Taxes | 29,044 | 31,749 | 33,891 | 35,404 | 36,830 | 7,786 | 26.8% |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 1,171 | 921 | 721 | 721 | 721 | (450) | (38.4%) |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $61,059 | $62,192 | $64,804 | $66,744 | $68,578 | $7,519 | 12.3% |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 7,265 | 6,790 | 6,777 | 6,777 | 6,775 | (490) | (6.7%) |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (2,061) | (1,811) | (1,807) | (1,806) | (1,806) | 255 | (12.4%) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | (15) | (15) | (15) | (15) | (15) | 0 | 0.0% |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $66,248 | $67,156 | $69,759 | $71,700 | $73,532 | $7,284 | 11.0% |

| Other Categorical Grants | 1,133 | 1,020 | 988 | 986 | 985 | (148) | (13.1%) |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | 695 | 706 | 656 | 656 | 656 | (39) | (5.6%) |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 11,866 | 7,076 | 6,946 | 6,929 | 6,924 | (4,942) | (41.6%) |

| State Categorical Grants | 15,111 | 16,327 | 16,765 | 16,814 | 16,814 | 1,703 | 11.3% |

| Total Revenues | $95,053 | $92,285 | $95,114 | $97,085 | $98,911 | $3,858 | 4.1% |

| Expenditures | |||||||

| Personal Service | |||||||

| Salaries and Wages | $29,179 | $29,684 | $30,017 | $30,288 | $30,751 | $1,572 | 5.4% |

| Pensions | 9,503 | 10,263 | 10,468 | 10,660 | 10,597 | 1,094 | 11.5% |

| Fringe Benefits | 11,130 | 11,579 | 12,242 | 13,045 | 13,819 | 2,689 | 24.2% |

| Retiree Health Benefits Trust | (1,600) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,600 | (100.0%) |

| Subtotal-PS | $48,212 | $51,526 | $52,727 | $53,993 | $55,167 | $6,955 | 14.4% |

| Other Than Personal Service | |||||||

| Medical Assistance | $5,553 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $5,915 | $362 | 6.5% |

| Public Assistance | $1,611 | $1,651 | $1,650 | $1,650 | $1,650 | $39 | 2.4% |

| All Other | $35,692 | $30,904 | $31,207 | $31,454 | $31,634 | ($4,058) | (11.4%) |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $42,856 | $38,470 | $38,772 | $39,019 | $39,199 | ($3,657) | (8.5%) |

| Debt Service | |||||||

| Principal | $3,263 | $3,765 | $4,225 | $4,110 | $2,398 | ($865) | (26.5%) |

| Interest & Offsets | $3,194 | $3,593 | $4,258 | $4,711 | $6,981 | $3,787 | 118.6% |

| Subtotal Debt Service | $6,457 | $7,358 | $8,483 | $8,822 | $9,379 | $2,922 | 45.3% |

| FY 2020 BSA | ($3,819) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $3,819 | (100.0%) |

| FY 2021 BSA | $3,358 | ($3,358) | $0 | $0 | $0 | ($3,358) | (100.0%) |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | $0 | $250 | $250 | $250 | $250 | NA |

| General Reserve | $50 | $100 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $950 | 1,900.0% |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | ($2,061) | ($1,811) | ($1,807) | ($1,806) | ($1,806) | $255 | (12.4%) |

| Total Expenditures | $95,053 | $92,285 | $99,425 | $101,278 | $103,189 | $8,136 | 8.6% |

| Gap to be Closed | $0 | $0 | ($4,311) | ($4,193) | ($4,278) | ($4,278) | NA |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 2. Plan-to-Plan Changes

January 2021 Plan vs. November 2020 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 |

| Revenues | ||||

| Taxes: | ||||

| General Property Tax | ($8) | ($2,479) | ($2,671) | ($2,607) |

| Other Taxes | 1,427 | 723 | 812 | 1,409 |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 250 | 200 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $1,669 | ($1,556) | ($1,859) | ($1,198) |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 240 | (31) | (32) | (33) |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (23) | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $1,886 | ($1,582) | ($1,886) | ($1,226) |

| Other Categorical Grants | 68 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | (1) | 52 | 0 | 0 |

| Federal Categorical Grants | $909 | $82 | $15 | $4 |

| State Categorical Grants | 169 | 42 | 33 | 33 |

| Total Revenues | $3,031 | ($1,384) | ($1,838) | ($1,189) |

| Expenditures | ||||

| Personal Service | ||||

| Salaries and Wages | ($218) | ($643) | ($487) | ($495) |

| Pensions | (429) | (303) | (70) | 350 |

| Fringe Benefits | (12) | 7 | 5 | 4 |

| Retiree Health Benefits Trust | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal-PS | ($659) | ($939) | ($552) | ($141) |

| Other Than Personal Service | ||||

| Medical Assistance | $315 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Public Assistance | (15) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All Other | 952 | 0 | 40 | 42 |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $1,252 | $0 | $40 | $42 |

| Debt Service | ||||

| Principal | $0 | ($131) | $39 | $36 |

| Interest & Offsets | ($215) | ($195) | ($25) | ($40) |

| Subtotal Debt Service | ($215) | ($326) | $14 | ($4) |

| FY 2020 BSA | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| FY 2021 BSA | $2,726 | ($2,726) | $0 | $0 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | ($250) | $0 | $0 |

| General Reserve | ($50) | ($900) | $0 | $0 |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | ($23) | $5 | $5 | $5 |

| Total Expenditures | $3,031 | ($5,136) | ($493) | ($98) |

| Gap to be Closed | $0 | $3,752 | ($1,345) | ($1,091) |

Table 3. Plan-to-Plan Changes

January 2021 Plan vs. June 2020 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 |

| Revenues | ||||

| Taxes: | ||||

| General Property Tax | ($8) | ($2,479) | ($2,671) | ($2,607) |

| Other Taxes | 2,175 | 723 | 812 | 1,409 |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 250 | 200 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $2,417 | ($1,556) | ($1,859) | ($1,198) |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 305 | (54) | (52) | (52) |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (219) | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $2,503 | ($1,584) | ($1,884) | ($1,222) |

| Other Categorical Grants | 158 | 31 | 0 | 0 |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | 18 | 31 | (19) | (19) |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 4,496 | 110 | 24 | 12 |

| State Categorical Grants | (314) | 43 | 26 | 26 |

| Total Revenues | $6,861 | ($1,369) | ($1,853) | ($1,203) |

| Expenditures | ||||

| Personal Service | ||||

| Salaries and Wages | ($570) | ($288) | ($519) | ($527) |

| Pensions | (429) | (219) | 94 | 590 |

| Fringe Benefits | 565 | 123 | (13) | (15) |

| Retiree Health Benefits Trust | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal-PS | ($434) | ($384) | ($438) | $48 |

| Other Than Personal Service | ||||

| Medical Assistance | $315 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Public Assistance | (17) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All Other | 4,821 | (35) | 54 | 55 |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $5,119 | ($35) | $54 | $55 |

| Debt Service | ||||

| Principal | ($455) | ($203) | $147 | $43 |

| Interest & Offsets | (458) | (445) | (375) | (367) |

| Subtotal Debt Service | ($913) | ($648) | ($228) | ($323) |

| FY 2020 BSA | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| FY 2021 BSA | $3,358 | ($3,358) | $0 | $0 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | ($250) | $0 | $0 |

| General Reserve | ($50) | ($900) | $0 | $0 |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | ($219) | $26 | $27 | $28 |

| Total Expenditures | $6,861 | ($5,549) | ($585) | ($192) |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $4,180 | ($1,268) | ($1,011) |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 4. Risks and Offsets to the January 2021 Financial Plan

($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap)

| FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | |

| City Stated Gap | $0 | $0 | ($4,311) | ($4,193) | ($4,278) |

| Tax Revenues | |||||

| Personal Income Tax | $495 | $29 | ($237) | ($77) | ($51) |

| Business Taxes | 350 | (40) | (178) | (187) | (173) |

| Sales Tax | 24 | 66 | 89 | 142 | 131 |

| Real Estate Transaction Taxes | (1) | 15 | (274) | (465) | (634) |

| Audit | 0 | 0 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Subtotal Tax Revenues | $868 | $70 | ($400) | ($387) | ($527) |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Overtime | ($287) | ($107) | ($130) | ($130) | ($130) |

| Charter School Tuition | 0 | (154) | (282) | (433) | (600) |

| Carter Cases | 0 | (150) | (150) | (150) | (150) |

| Pupil Transportation | 0 | (75) | (75) | (75) | (75) |

| DOE Medicaid Reimbursement | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) |

| Pre-K Special Education | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Fair Fares | 0 | (47) | (100) | (100) | (100) |

| Homeless Shelters | 0 | (12) | (12) | (12) | (12) |

| Labor Savings | (290) | (1,000) | (1,000) | (1,000) | (1,000) |

| Paratransit Funding | 0 | (81) | (111) | (130) | (150) |

| VRDB Interest Savings | 25 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| General Reserve | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | ($472) | ($1,496) | ($1,730) | ($1,900) | ($2,087) |

| Total (Risks)/Offsets | $396 | ($1,426) | ($2,130) | ($2,287) | ($2,614) |

| Restated (Gap)/Surplus | $396 | ($1,426) | ($6,441) | ($6,480) | ($6,892) |

Note: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

II. The City’s Economic Outlook

The Economy in 2020

In response to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments around the world restricted economic activity and encouraged social distancing in order to slow the spread of the virus and prevent hospitals from being overwhelmed. Large gatherings were restricted, travel and tourism collapsed, sports and entertainment venues closed.

In the U.S., restrictions varied greatly by state and locality, but containment measures brought a decisive end to 10 years of economic expansion as the U.S. economy shrank at an annualized rate of 31.4 percent in the 2nd quarter, the sharpest decline on record. Office workers switched to remote work, and many lower-income service workers lost their jobs, particularly in the nation’s cities, as their workplaces closed and wary consumers stayed home. Seasonally adjusted U.S. employment fell from 152 million in February 2020 to 130 million in April, and the unemployment rate rose from 3.5 percent to 14.8 percent over the same period.

In response, the Federal government passed the $2.2 trillion CARES Act, the largest economic stimulus package in the nation’s history, on March 27th. It included direct stimulus payments to Americans, industry loans, small business loans, and expanded eligibility and benefits for U.S. unemployment insurance programs, and helped millions of Americans endure.

Increased COVID testing capacity, public behavior changes, and warmer weather held infections down over the summer and allowed significant economic reopening in the third quarter, with the U.S. economy rebounding at the annualized rate of 33.4 percent.

But, with the return of colder weather and the pandemic reaching rural areas of the country that earlier had been spared, COVID infections resurged and the economic recovery stalled toward the end of the year with new job losses and rising unemployment insurance claims. December U.S. employment ended the year at 142.6 million, down almost 10 million from February 2020 and down over 200,000 from November.

The year ended on a hopeful note, with the U.S. Food and Drug administration approving new COVID vaccines by Moderna and Pfizer in mid-December. And in the final week of the year, Congress approved a second round of stimulus payments, renewed the Paycheck Protection Program, and extended unemployment insurance programs enacted through the CARES Act for an additional 11 weeks.

U.S. Economic Outlook

Despite falling COVID infections, positive test and hospitalization rates, and deaths, which peaked over the year-end holidays, a full U.S. reopening and economic recovery depends very much upon an effective vaccination program. U.S. vaccination efforts got off to a slow start with widespread logistical and distribution issues, and restrictions on eligibility limiting the number of people getting vaccinated. As of February 10th, the U.S. had distributed 66 million vaccine doses, of which 45 million had been administered.[1]

While many local distribution issues have been addressed, fundamental constraints on the quantity of vaccines available for near-term distribution remain. In the first quarter of 2021 supplies will likely remain inadequate to expand vaccination beyond front-line healthcare workers, first responders and seniors. This shortage of available vaccines will highlight inequities in vaccine distribution that mirror other social and economic inequities in the U.S. economy.

Vaccination of these priority populations should enable infections, positive test rates, hospitalization and deaths to continue falling through the first quarter, although new, and more contagious strains bring the risk of yet another U.S. COVID resurgence, as has been experienced by countries including the U.K and South Africa. Absent widespread outbreaks of new strains, increasing vaccinations and warmer weather should allow a gradual resumption of economic and employment growth later in the first quarter.

In the second quarter of 2021, vaccine availability should increase dramatically, through both expanded manufacturing capacity of already approved vaccines by Moderna and Pfizer, and through the approval of new vaccines, such as those from Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca. Johnson and Johnson’s single dose vaccine was submitted for F.D.A. emergency use authorization on February 4th, with approval expected before the end of the month.

Increased vaccine supplies will bring expanded vaccine eligibility and should allow most Americans to be vaccinated by the end of the second quarter. This will bring a dramatically accelerated economic recovery, and a return to a more normal life, albeit in a changed world where remote work and online shopping retain increased importance, and where the economic damage from the pandemic has fallen hardest on those with the least means to bear it.

While the country awaits increased vaccine availability, the Biden administration is currently negotiating with Congress on the scope of a third round of economic stimulus that, together with the possibility of resurgence from new COVID strains, will shape the direction of the first quarter economy.

New York City’s Economic Condition and Outlook

New York City was hit earlier and harder by the pandemic and has experienced a disproportionate share of the impacts. Despite rebounding from April lows, seasonally adjusted December private employment in New York City remains 605,000 below the pre-pandemic peak and declined by over 19,000 from November.

Table 5. New York City Employment Changes as of Decemeber

| (Seasonally Adjusted, thousands) | December Employment | Change from Feb. 2020 Peak | Change from April 2020 Lows | Change from November |

| Total Private Employment | 3,481 | (605) | 269 | (19) |

| Finance and Insurance | 329 | (16) | (10) | 1 |

| Real Estate | 125 | (11) | 5 | 1 |

| Information | 210 | (2) | 11 | 4 |

| Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services | 403 | (35) | (7) | (1) |

| Management of Companies and Enterprises | 70 | (7) | 0 | (0) |

| Administrative Services | 234 | (58) | 19 | 1 |

| Employment Services | 109 | (21) | 9 | 1 |

| Educational Services | 211 | (36) | (5) | (4) |

| Health Care and Social Assistance | 783 | (44) | 58 | 1 |

| Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation | 30 | (60) | (4) | (2) |

| Accommodation and Food Services | 199 | (170) | 69 | (14) |

| Other Services | 161 | (39) | 21 | (2) |

| Retail Trade | 299 | (43) | 45 | (2) |

| Wholesale Trade | 119 | (20) | 2 | 0 |

| Transportation and Warehousing | 106 | (26) | 7 | (1) |

| Utilities | 15 | (1) | 0 | (0) |

| Construction | 135 | (24) | 51 | (2) |

| Manufacturing | 54 | (13) | 6 | 1 |

Source: N.Y. Dept. of Labor, seasonally adjusted by NYC OMB

Job losses were concentrated in industries providing in-person services: accommodation and food services, arts and entertainment, and retail. Industries such as securities, professional services and information avoided shutdowns by transitioning to remote work and were spared large-scale job losses.

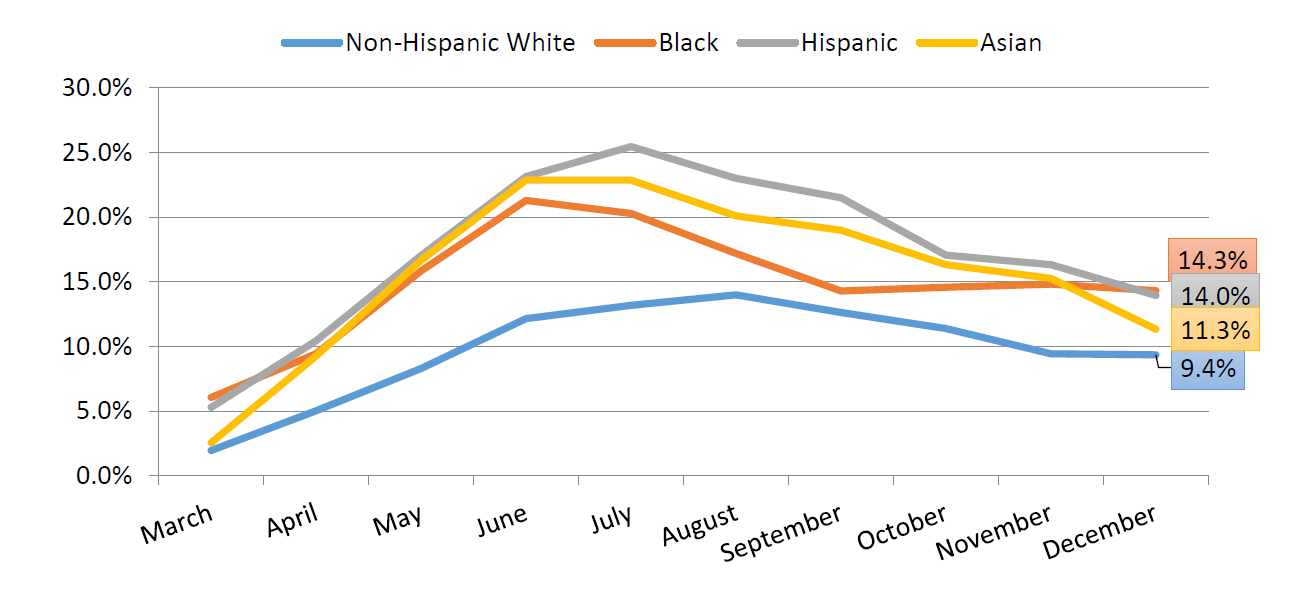

This combination has exacerbated existing economic disparities, as the New York City industries spared from closures and job losses pay higher salaries, and industries providing in-person services disproportionately employ people of color at lower wages. New York City’s unemployment rate spiked from 3.4 percent in February 2020 to 20.4 percent in June, falling gradually to 11.0 percent in December. Unemployment rates for black, Hispanic and Asian New Yorkers peaked higher, at over 25 percent for Hispanic residents, and remain elevated. 3-month average unemployment rates in December 2020 were 14.3 percent for black workers, 14.0 percent for Hispanic workers, 11.3 percent for Asian workers, and 9.4 percent for white workers in New York City (Chart 1).

Chart 1. NYC 2020 Employment Rates by Race/Ethnicity

(3-Month Average, Not Seasonally Adjusted)

Source: Current Population Survey

Manhattan office buildings remain largely empty, as office workers switched to telecommuting in March, and have yet to return in significant numbers.

Bars and restaurants which had reopening with limited indoor capacity, closed to indoor service in December, and consumer’s willingness to dine outdoors has been dampened by colder temperatures, snow, and more virulent virus strains. Entertainment venues such as concerts, opera, ballet, dance, Broadway, fashion shows and sporting events remain closed. Art galleries and museums are open, but at reduced capacity. In short, most of the amenities that make New York City a desirable place to live, particularly for the wealthy, and a world class destination for people from around the country and around the world, are closed.

With the City’s cultural amenities closed, and the country still closed to most foreign travel, tourists continue to stay home, business travelers meet virtually instead, and New York City hotels remain largely unvisited. New York City retail stores, deprived of the patronage of both commuting office workers and out-of-town visitors, continue to suffer from reduced sales, and many have closed.

But not all is as bleak as it seems. New COVID cases, perhaps the strongest leading indicator of economic activity over the past year, have been falling since early January. New York City’s positive test rate peaked at 9.7 percent on January 3rd, and has since fallen closer to 8 percent. Seven-day average new cases per day peaked at 6,373 on January 8th and have since fallen below 4,000. New hospitalizations, which lag cases, peaked on January 18th and have since fallen steadily; and COVID related deaths, which lag hospitalizations, have leveled off after rising for three months straight.[2]

Despite initial difficulties with the vaccine rollout, and ongoing issues with equitable distribution, New York City has administered more vaccine doses than any other U.S. city, and more per capita than most other U.S. urban areas that publish timely data.

Chart 2. Vaccinations Administered in Selected Jurisdictions

Source: Current data as of 2/11/2021 from state, county and city health departments.

As of early February, New York City had vaccinated almost 70 percent of long-term care residents and nearly 50 percent of staff.[3] On January 11th, New York State expanded vaccine eligibility from first responders, healthcare workers and seniors to include transit workers, correctional facilities, grocery store workers, teachers and homeless shelters. Eligibility was further expanded on February 2nd to include taxi drivers and restaurant workers.

Vaccines administered to these New York City groups will increasingly tamp down transmission rates as vaccination reaches a greater share of the targeted populations. Based on current infection trajectories, Governor Cuomo has scheduled the reopening of New York City bars and restaurants for reduced capacity indoor service on Valentine’s Day.

Vaccine availability should continue to improve with the likely approval of new vaccines from Johnson & Johnson, and AstraZeneca, as well as measures to speed delivery of already approved vaccines. Moderna has plans to increase the number of doses per vial by 50 percent, the current bottleneck on the company’s production capacity. Pfizer recently announced an expanded production target of 2 billion COVID vaccine doses in 2021, up from the prior 1.2 billion.[4]

Although there is a risk of a renewed New York City outbreak from new and more contagious COVID strains, increased vaccine availability should continue to reduce transmission rates. Greater availability will allow a spring expansion of vaccine eligibility to include the public at large. New cases will begin falling more quickly in the spring, aided by warmer weather, and will permit an accelerated return to in-person business.

The risk of having hospitals overwhelmed by COVID patients was the impetus for the initial economic shutdowns of March 2020, and a factor in other economic restrictions imposed since. With increasing rates of vaccination among seniors, hospitalizations and deaths will fall even more quickly than new infections, because seniors account for almost half of COVID hospitalizations[5] and 80 percent of COVID deaths.[6]

Our forecast has no economic and employment growth in New York City through the first quarter of 2021 with vaccine deliveries slowly accelerating, and COVID infection rates slowly declining, but economic and employment growth lagging. Increased vaccination will lead COVID infection rates to begin falling dramatically in the second quarter of 2021, followed quickly by economic reopening and accelerating economic and employment growth. Our forecast has New York City employment rebounding over the course of the next year before growth levels off and returns to pre-pandemic rates in the spring and summer of 2022.

As the pandemic recedes it will leave a changed city where many continue to work remotely on at least a part-time basis and consumers continue to do a larger share of their shopping online. Foreign visitors will take longer to return, as most European and Asian countries lag the U.S. in vaccination. Asian countries that were more successful in containing the virus, but have less access to vaccines may be especially hesitant to allow their citizens to travel to the U.S.

Table 6. Selected Economic Indicators, Annual Averages,

Comptroller and Mayor’s Forecast, 2020 to 2025

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |||

| SELECTED U.S. ECONOMIC INDICATORS (ANNUAL AVERAGES) | ||||||||

| Real GDP (2012 $, % Change) | Comptroller | -3.5 | 4.6 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 | |

| Mayor | -3.4 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | ||

| Payroll Jobs (Change In Millions) | Comptroller | -8.7 | 2.5 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 0.8 | |

| Mayor | -8.7 | 4.1 | 5.0 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.3 | ||

| Fed Funds Rate (Percent) | Comptroller | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.2 | |

| Mayor | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||

| 10-Year Treasury Notes, (percent) | Comptroller | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 2.4 | |

| Mayor | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.9 | ||

| SELECTED NYC ECONOMIC INDICATORS (ANNUAL AVERAGES) | ||||||||

| Real GCP (2012 $, % Change) | Comptroller | -6.3 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 1.8 | 0.9 | |

| Mayor | -0.6 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 2.5 | ||

| Payroll Jobs, (Change In Thousands) | Comptroller | -507 | 216 | 273 | 101 | 105 | 109 | |

| Mayor | -511 | 191 | 253 | 99 | 57 | 65 | ||

| Wage-Rate Growth, (Percent) | Comptroller | 5.8 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 2.2 | |

| Mayor | 4.4 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.9 | ||

Note: Comptroller=forecast by the NYC Comptroller’s Office. GCP=Gross City Product. Mayor=forecast by the NYC Office of Management and Budget in the January 2020 Financial Plan.

III. The FY 2022 Preliminary Budget

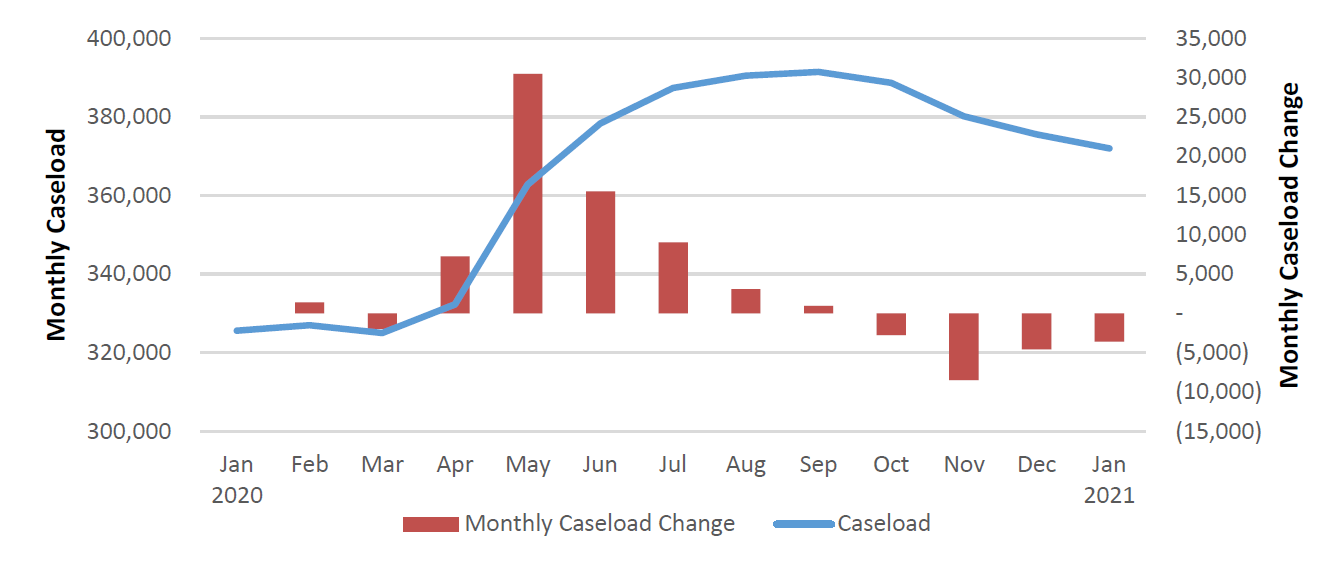

The FY 2022 Preliminary Budget released on January 14th shows a balanced budget of $92.29 billion. Revenues in the Preliminary Budget are $1.38 billion less than projected in the November Plan. However, a sharper reduction of $5.14 billion in expenditures, driven by an increase of $2.73 billion in planned prepayment of FY 2022 debt service and reductions of $1.15 billion in budgeted reserves, offsets the revenue shortfall and allows the City to close the $3.75 billion gap projected in November.

Nearly all the revenue decreases are due to re-estimates of City-funds revenues which are revised downward by $1.58 billion from the November Plan projection, as shown in Table 7.[7] Revisions to tax revenue estimates account for more than 98 percent of the decline in City-funds revenues, driven by a downward revision of $2.51 billion in property tax revenues.[8] The drop in property tax revenues reflects the drop in property values since the onset of the pandemic. A net increase in non-property tax revenues of $923 million, driven by increases of $637 million in business tax, $531 million in personal income tax (PIT), and $200 million in tax audit revenues, provides some offset against the drop in property tax revenues.

Table 7. Changes to FY 2022 City-Funds Estimates

from the November 2020 Plan

| ($ in millions) | |

| Gap to be Closed – November 2020 Plan | ($3,752) |

| Revenues | |

| Property Tax Revenues | ($2,507) |

| Non-Property Tax Revenues | 723 |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 200 |

| Non-Tax Revenues | (28) |

| Revenues From Citywide Savings Program | 30 |

| Total Revenue Changes | ($1,582) |

| Expenditures | |

| Agency Expenditures | $129 |

| FY 2020 Lump Sum/Retro/Welfare Funds Deferrals | 52 |

| Pension Contributions | (304) |

| Savings From Citywide Savings Program | (1,336) |

| General Reserve | (900) |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | (250) |

| Total Expenditure Changes | ($2,609) |

| Gap To Be Closed Before Prepayments | ($2,725) |

| FY 2021 Prepayment of FY 2022 Debt Service | $2,725 |

| Gap to be Closed – January 2021 Financial Plan | $0 |

FY 2022 City-funds expenditures, before accounting for the reduction in debt service from FY 2021 prepayments, show a net decrease of $2.61 billion from the November Plan. This reduction stems largely from spending reductions of $1.34 billion in the January Plan Citywide Savings Program (CSP), a $1.15 billion take down of budgeted reserves, and a reduction of $304 million in pension contribution from proposed changes in actuarial assumptions and methods.

Setting aside spending reductions in the CSP, agency expenditures are $129 million above the November Plan. The increase in agency spending reflects funding of $35 million in the Department of Education (DOE) for the new Academic Resiliency program and $53 million in the Department of Social Services (DSS) for the Fair Fares program. The November Plan included funding for the Fair Fares program in FY 2021 only. While the January Plan adds $53 million for the Fair Fares program in FY 2022, the program remains unfunded in the outyears.

In addition, since the release of the November Plan, the City negotiated another $52 million in deferrals of FY 2021 retroactive, lump sum and welfare fund payments. While the deferrals provide budget relief in FY 2021 it pushes these payments into FY 2022.

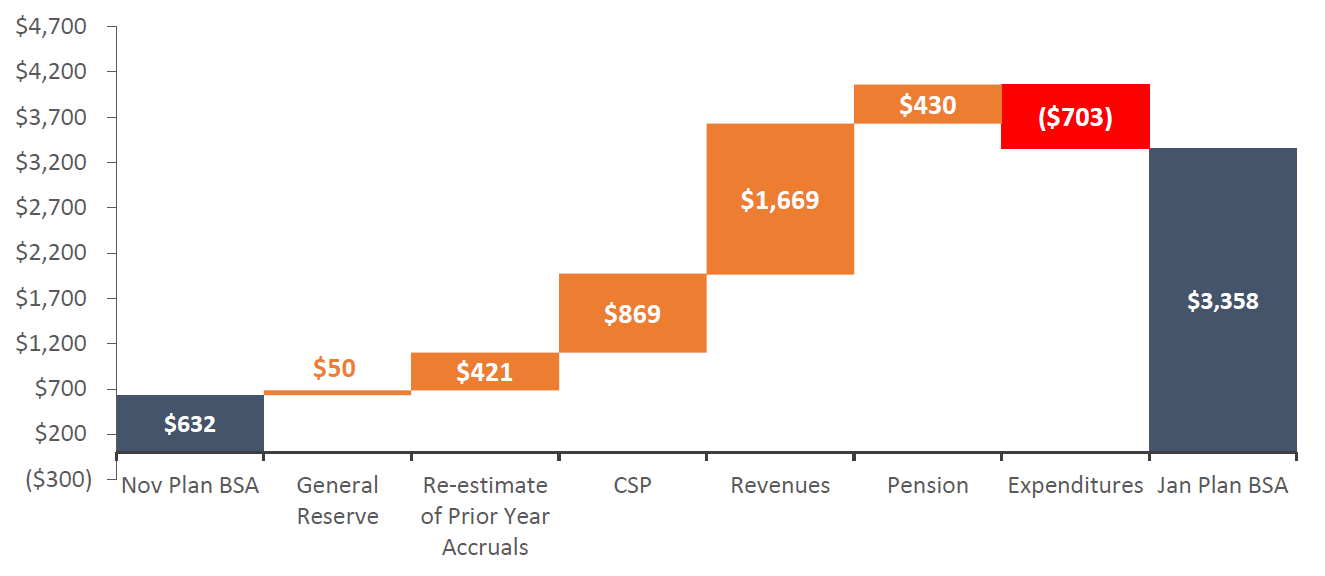

FY 2021 Budget Stabilization Account (BSA)

Since the November Plan, the City has recognized a net $2.73 billion of additional resources in the FY 2021 budget. Because these resources are not required to balance the current fiscal year’s budget, they are used to increase the FY 2021 Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), bringing the total FY 2021 BSA to $3.36 billion. The BSA will be used to prepay $2.68 billion of Transitional Finance Authority (TFA) Future Tax Secured (FTS) debt service and $676 million of General Obligation (G.O.) debt service. As shown in Chart 3, these additional resources are the result of:

- A reduction of $50 million in the FY 2021 General Reserve;

- A net savings of $421 million from adjustments to prior-year receivables and payables estimates;

- A new round of CSP with projected FY 2021 savings of $869 million;

- An increase of $1.67 billion in City-funds revenues;

- A reduction of $430 million in pension contributions; less

- Additional City-funds spending of $703 million

Chart 3. The January Plan Increases the BSA by $2.17 Billion

($ in millions)

Citywide Savings Program (CSP)

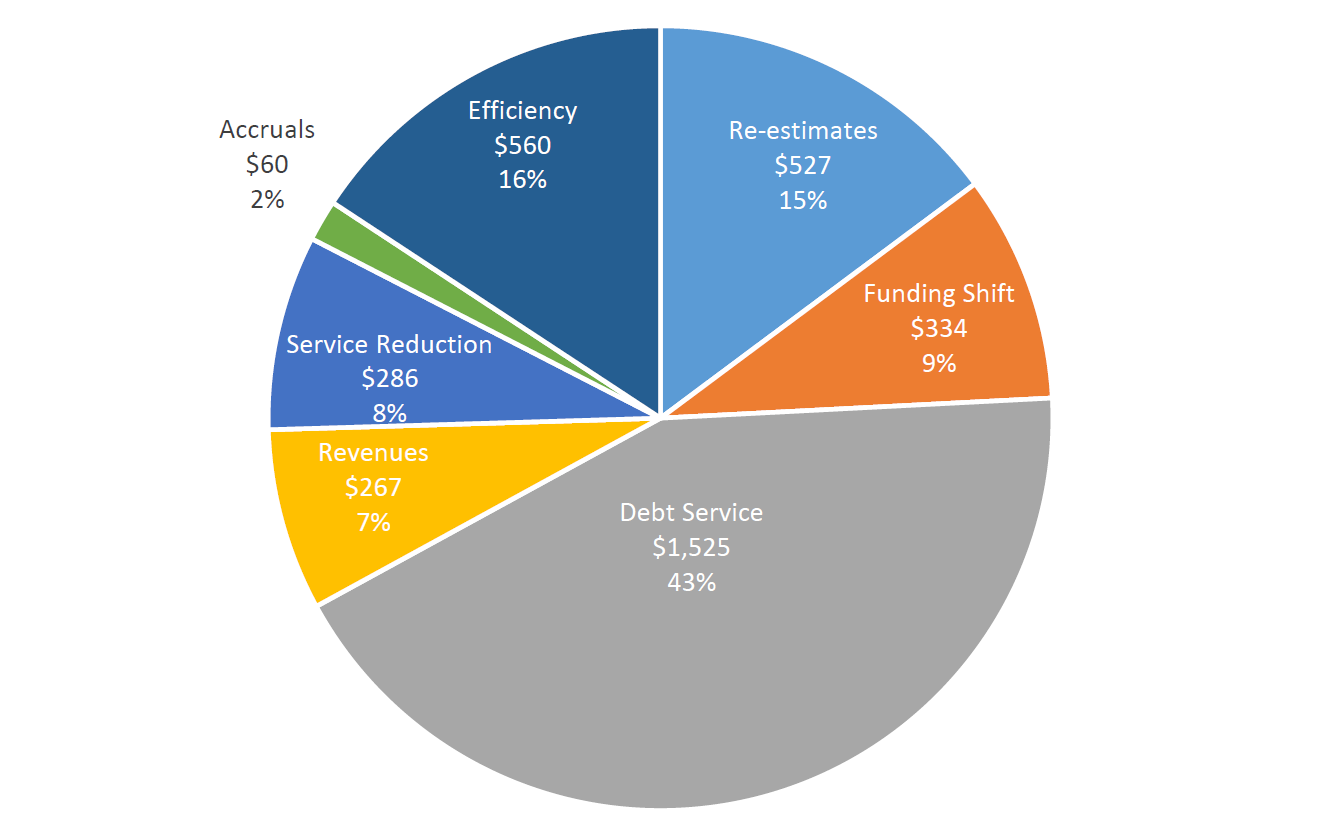

The January 2022 Plan includes another round of the CSP that is estimated to provide budget relief of $869 million in FY 2021, $1.37 billion in FY 2022, $580 million in FY 2023, $605 million in FY 2024, and $624 million in FY 2025.

Almost a quarter of the budget relief in FY 2021 is from a one-time debt service reimbursement of $212 million from NYC Health + Hospitals (H+H, formerly the Health and Hospitals Corporation, or HHC). An initiative to limit non-essential civilian hiring to one new hire for every three separations is expected to produce $1.44 billion of savings over the Plan period, beginning at $57 million in FY 2021 and growing to $364 million by FY 2025.

With the current round of the CSP, estimated budget relief over the Plan period now totals $6.34 billion. The combined savings in FY 2021 and FY 2022 total $3.56 billon. As shown in Chart 4, debt service and efficiency initiatives make up almost 60 percent of the savings. Service reductions which, with the exception of the cutback on broom service to residential streets to once a week, do not extend beyond FY 2022, account for 8 percent or $286 million of the savings. However, the Mayor has indicated that he will rescind the temporary reduction of Fair Student Funding at DOE, which accounts for $150 million of the service reductions, using additional Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reimbursements. The Mayor has also indicated that he will rescind the delay of 3K expansion which accounts for $44 million of the savings from re-estimates.

Chart 4. Combined FY 2021 and FY 2022 Citywide Savings Program

($ in millions)

Risks and Offsets

As Table 8 shows, the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the January Plan shows additional resources of $396 million in FY 2021 and risks to the budget ranging from $1.43 billion in FY 2022 to $2.61 billion in FY 2025. The additional resources in FY 2021 result from the Comptroller’s Office’s higher tax revenue forecasts which offset the expenditure risks identified by the Office. Risks to the budget in the outyears of the Plan are driven by the Comptroller’s Office’s higher expenditure estimates, with a modestly higher tax revenue estimate mitigating some of the risks in FY 2022, and lower tax revenues adding to the expenditure risks in FY 2023 through FY 2025. The Comptroller’s Office’s tax revenue forecast is discussed in more detail in “Comptroller’s Office’s Revisions and Projections, FY 2021 – FY 2025” beginning on page 16.

The Comptroller’s Office estimates that expenditures could exceed the Plan projections by $472 million in FY 2021, $1.50 billion in FY 2022, $1.73 billion in FY 2023, $1.90 billion in FY 2024, and $2.09 billion in FY 2025. The biggest risk to expenditures is the assumption of as yet unspecified labor savings in the Plan. The City had assumed annual labor savings $1 billion beginning in FY 2021 in the June Plan. Since then, the City had credited $710 million of deferral and furlough savings to FY 2021, leaving a residual risk of $290 million. However, the Plan continues to assume $1 billion of savings in each of the outyears.

Other expenditure risks include funding for the Fair Fares program, paratransit funding, overtime and expenditure estimates in the DOE and the Department of Homeless Services (DHS). The Preliminary budget added $53 million to the Fair Fares program in FY 2022 but the outyears remain unfunded. The Comptroller’s Office estimates that the program could cost at least $100 million annually beginning in FY 2022 as participation rate picks up, posing risks of $47 million in FY 2022, and $100 million in each of FY 2023 through FY 2025. In addition, the Comptroller’s Office estimates shortfalls in paratransit funding beginning at $81 million in FY 2022 and growing to $150 million by FY 2025. While the State requires the City to increase its funding of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) net paratransit deficit from 33 percent to 50 percent, funding for paratransit in the Financial Plan does not reflect the increase in funding requirement. Risks to overtime, DOE and DHS are discussed below in the “Expenditure Analysis” section beginning on page 26.

The City’s conservative estimates of interest rates on variable rate debt bonds (VRDB) provide some offset to the Comptroller’s Office’s expenditure risks. In an environment of low variable interest rates and no indication that rates will rise to the level assumed over the Plan period, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that debt service on VRDB could be less than the Plan projections by $25 million in FY 2021 and $100 million annually in FY 2022 through FY 2025.

Overall, the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the Plan indicates that the City could end FY 2021 with an additional budget surplus of $396 million, but larger gaps of $1.43 billion in FY 2022, $6.44 billion in FY 2023, $6.48 billion in FY 2024, and $6.89 billion in FY 2025.

The January Plan does not reflect potential Federal budget relief from actions taken by the Biden administration. Since the release of the January Plan, the President has signed an executive order authorizing FEMA to reimburse the entire cost of eligible COVID related spending, retroactive to spending since the onset of the pandemic. The January assumes FEMA reimbursement for 75 percent of eligible expenditures. The additional reimbursement, which is estimated to provide an additional $1 billion of FEMA funding to the City, will allow the City to rescind or reduce some of the service reductions in the Plan and use the balance towards budget relief.

Table 8. Risks and Offsets to the January 2021 Financial Plan

($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap)

| FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | |

| City Stated Gap | $0 | $0 | ($4,311) | ($4,193) | ($4,278) |

| Tax Revenues | |||||

| Personal Income Tax | $495 | $29 | ($237) | ($77) | ($51) |

| Business Taxes | 350 | (40) | (178) | (187) | (173) |

| Sales Tax | 24 | 66 | 89 | 142 | 131 |

| Real Estate Transaction Taxes | (1) | 15 | (274) | (465) | (634) |

| Audit | 0 | 0 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

| Subtotal Tax Revenues | $868 | $70 | ($400) | ($387) | ($527) |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Overtime | ($287) | ($107) | ($130) | ($130) | ($130) |

| Charter School Tuition | 0 | (154) | (282) | (433) | (600) |

| Carter Cases | 0 | (150) | (150) | (150) | (150) |

| Pupil Transportation | 0 | (75) | (75) | (75) | (75) |

| DOE Medicaid Reimbursement | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) |

| Pre-K Special Education | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Fair Fares | 0 | (47) | (100) | (100) | (100) |

| Homeless Shelters | 0 | (12) | (12) | (12) | (12) |

| Labor Savings | (290) | (1,000) | (1,000) | (1,000) | (1,000) |

| Paratransit Funding | 0 | (81) | (111) | (130) | (150) |

| VRDB Interest Savings | 25 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| General Reserve | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | ($472) | ($1,496) | ($1,730) | ($1,900) | ($2,087) |

| Total (Risks)/Offsets | $396 | ($1,426) | ($2,130) | ($2,287) | ($2,614) |

| Restated (Gap)/Surplus | $396 | ($1,426) | ($6,441) | ($6,480) | ($6,892) |

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

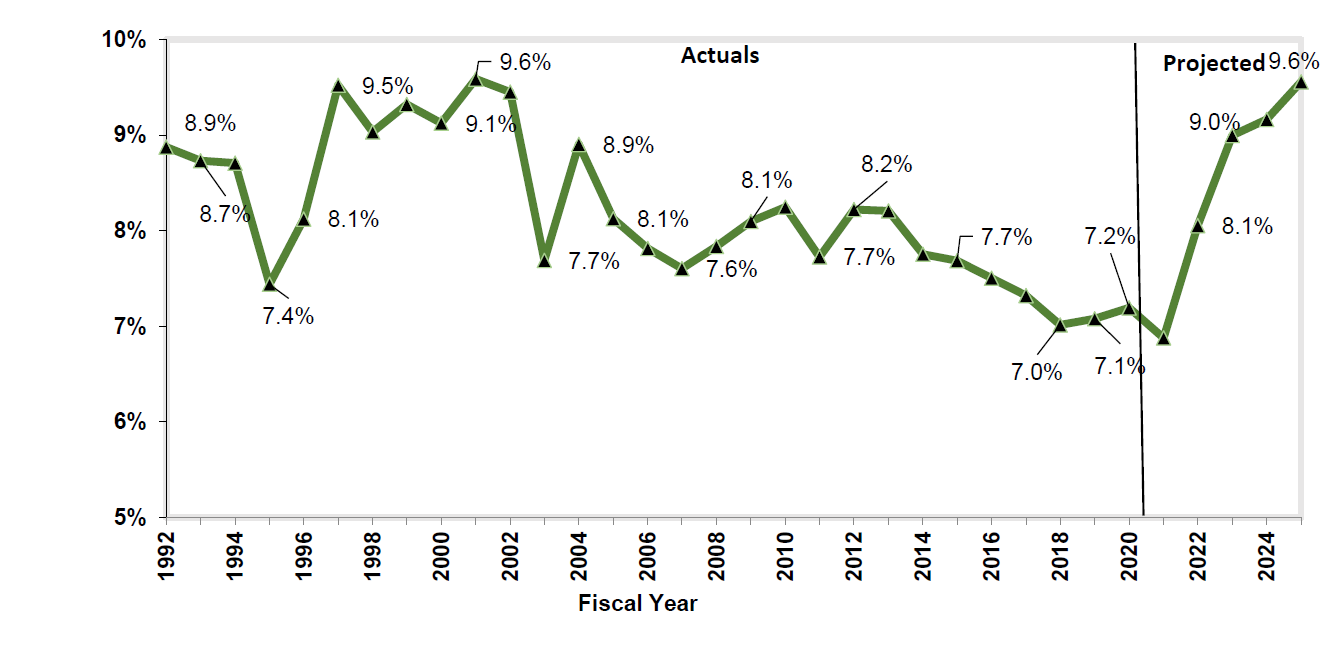

Revenue Analysis

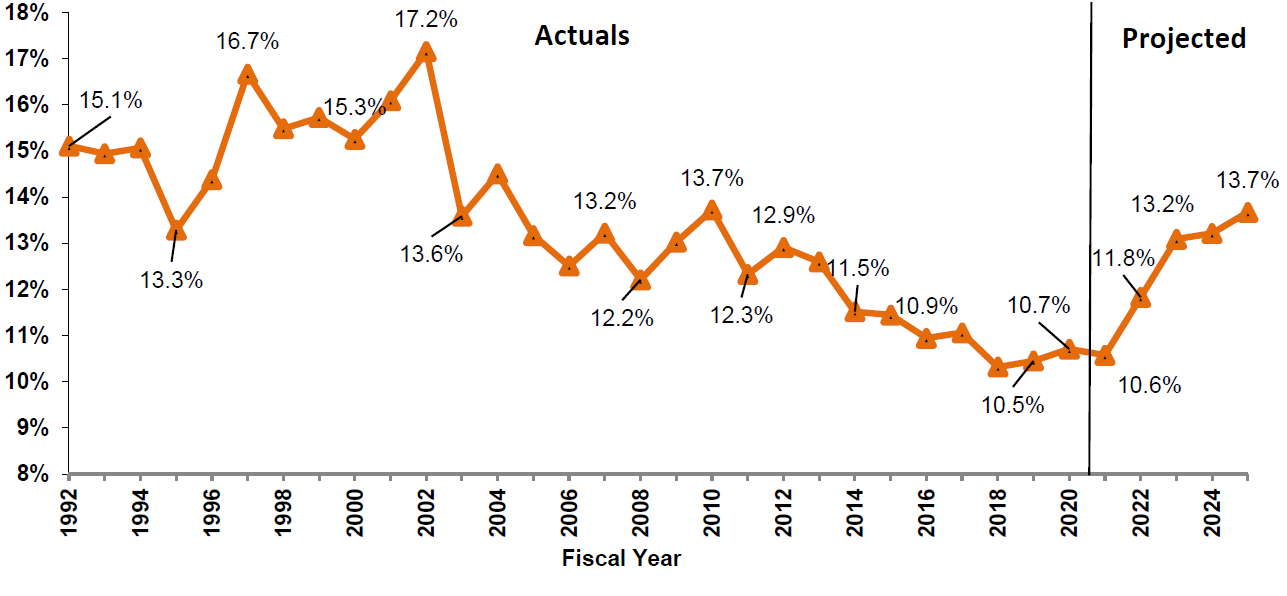

Total revenues in the January Plan are estimated to grow by $3.86 billion over the forecast period, from $95.05 billion in FY 2021 to $98.91 billion in FY 2025. Overall tax revenue is projected to grow by $7.52 billion over the same period, averaging 2.3 percent annual growth. The increase in overall tax revenues is driven almost entirely by an expected rebound in non-property tax revenues as the City’s economy begins to recover from the devastating effects of the pandemic. Property tax revenues, on the other hand, are projected to fall significantly in FY 2022, by 4.3 percent — the largest decline since 1996 — and then to stabilize and grow gradually through the remainder of the Plan. In FY 2025 property tax revenues are expected to be essentially unchanged from FY 2021, a significant reversal from previous forecasts.

Miscellaneous revenues are projected to drop by $225 million to $4.98 billion in FY 2022, and to stay relatively flat at about $4.7 billion throughout the rest of the Plan period. The reduction in FY 2022 reflects a one-time reimbursement of $213 million by H+H for debt service in FY 2021.

FY 2021 Federal and State aids total $25.90 billion and account for 28 percent of the City’s overall revenue estimate. Over the outyears of the Plan, Federal and State grants are projected to decline to $23.40 billion in FY 2022 before increasing modestly to $23.71 billion in FY 2023. Over the remainder of the Plan, Federal and State aids are projected to remain essentially flat at $23.7 billion.

Tax Revenues

Revisions since the November Financial Plan, FY 2021 – FY 2025

The January Plan incorporates large changes to almost all revenue sources as shown in Table 9. Property tax revenue was revised significantly downwards to reflect the release of the tentative roll that indicated a sharp drop in market values for most property types.[9] As a result, property tax revenues were lowered by $2.5 billion beginning in FY 2022 and by roughly similar amounts throughout the Plan. Sales tax and all other taxes (which include the hotel occupancy tax) were also revised lower, though by smaller amounts due to a slower forecast recovery in the tourism sector. All other revenue sources were revised upwards. In particular, income and business taxes were revised significantly higher in the current fiscal year. To a large extent the revision to the income sensitive taxes in FY 2021 reflects the fact that forecast revenues losses due to the pandemic so far have been less than originally anticipated.

Table 9. Revisions to the City’s Tax Revenue Assumptions

January 2021 Plan vs. November 2020 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 |

| November 2020 Financial Plan | $59,390 | $63,748 | $66,663 | $67,942 | $67,942 |

| Revisions: | |||||

| Property Tax | (8) | (2,479) | (2,671) | (2,607) | (2,199) |

| Personal Income (PIT) | 822 | 531 | 528 | 506 | 1,063 |

| Business | 653 | 637 | 529 | 613 | 723 |

| Sales | (215) | (441) | (253) | 76 | 535 |

| Real-Estate Transactions | 273 | 336 | 308 | 372 | 533 |

| All Other | (106) | (340) | (300) | (158) | (19) |

| Tax Audit | 250 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | $1,669 | ($1,556) | ($1,859) | ($1,198) | $636 |

| January 2021 Financial Plan – Total | $61,059 | $62,192 | $64,804 | $66,744 | $68,578 |

Comptroller’s Office Revisions and Projections, FY 2021 – FY 2025

Similar to the City, the Comptroller’s Office’s projections also reflect significant revisions to property tax revenues that were based on new data provided in the tentative roll. Following the decline in property tax revenue of 4.3 percent in FY 2022, the Comptroller’s Office projects that moderate growth will resume in the outyears. This is predicated on the forecast rebound in the local economy and the assumption that the downward effects on property values have largely already occurred. The Comptroller’s Office’s baseline projections are not significantly different from the City’s forecast. There is, however, a high degree of uncertainty surrounding this forecast as discussed in more detail in the following section.

With regard to non–property tax revenues, the Comptroller’s Office projects higher near term growth in FY 2021 and FY 2022 than the Mayor, and lower growth in the outyears. The projected higher growth in the near term reflects both stronger than anticipated collections data, and a sharper rebound in employment in the near term compared to the City’s projections. The overall differences are shown in Tables 10 and 11.

Table 10. Risks and Offsets to the City’s Tax Revenue Projections

| ($ in millions) | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 |

| Property | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| PIT | $495 | $29 | ($237) | ($77) | ($51) |

| Business | $350 | ($40) | ($178) | ($187) | ($173) |

| Sales | $24 | $66 | $89 | $142 | $131 |

| Real Estate Transaction | ($1) | $15 | ($274) | ($465) | ($634) |

| Audit | $0 | $0 | $200 | $200 | $200 |

| Total | $868 | $70 | ($400) | ($387) | ($527) |

Table 11. Tax Revenue Forecast, Growth Rates

| FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FYs 2021 – 25 Average Annual Growth | |

| Property | ||||||

| Mayor | 3.4% | (4.3%) | 2.3% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 0.1% |

| Comptroller | 3.4% | (4.3%) | 2.3% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 0.1% |

| PIT | ||||||

| Mayor | (6.0%) | 6.0% | 5.6% | 3.6% | 3.8% | 4.7% |

| Comptroller | (2.3%) | 2.2% | 3.6% | 4.8% | 4.0% | 3.7% |

| Business | ||||||

| Mayor | (9.1%) | 6.4% | 4.0% | 1.0% | 1.7% | 3.3% |

| Comptroller | (3.7%) | (0.2%) | 1.8% | 0.9% | 1.9% | 1.1% |

| Sales | ||||||

| Mayor | (11.1%) | 16.7% | 10.0% | 6.9% | 5.1% | 9.6% |

| Comptroller | (10.8%) | 17.3% | 10.2% | 7.4% | 4.9% | 9.9% |

| Real Estate Transactions | ||||||

| Mayor | (19.1%) | 18.8% | 11.0% | 6.7% | 6.7% | 10.7% |

| Comptroller | (19.2%) | 19.7% | (3.2%) | (2.0%) | (0.4%) | 3.1% |

| All Other | ||||||

| Mayor | (21.2%) | 6.8% | 6.7% | 8.0% | 5.2% | 6.7% |

| Comptroller | (21.2%) | 6.8% | 6.7% | 8.0% | 5.2% | 6.7% |

| Audit | ||||||

| Mayor | 14.2% | -21.3% | -21.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | -11.4% |

| Comptroller | 14.1% | -21.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | -5.8% |

| Total Tax with Audit | ||||||

| Mayor | -3.2% | 1.9% | 4.2% | 3.0% | 2.7% | 2.9% |

| Comptroller | -1.8% | 0.5% | 3.4% | 3.0% | 2.6% | 2.4% |

Property Taxes

The 2022 tentative roll released by the Department of Finance on January 15th showed how swift and devastating the impact of the pandemic has been on property values. Overall Class 2 properties, which includes rentals, and coops and condos, declined by 8.0 percent on average. Commercial property values (Class 4) were impacted even harder declining by 15.8 percent on average. Office buildings, the largest source of revenue within Class 4, experienced market value declines of 15.1 percent while values for hotel and retail properties, the most severely impacted by the pandemic, declined by 23.8 percent and 21.0 percent respectively. Class 1 properties which include 1-3 family homes fared better, increasing by a slight 0.8 percent, with growth in the market value of single-family homes of 2.9 percent offsetting declines in other categories.[10]

While the Comptroller’s Office’s forecast in November had anticipated significant declines in property taxes to occur, the magnitude and swiftness of these declines, particularly for office buildings, was unanticipated. The collapse in values meant that the pipeline of accumulated phase-ins in assessments from previous years of growth was quickly depleted. Instead of the more phased and gradual impact that was anticipated, a much more immediate adjustment to taxable assessed values occurred.

The Comptroller’s Office baseline assumption is that the swift and substantial declines in property values that Class 2 and Class 4 in FY 2022 largely incorporate the downside effects of the pandemic. The real estate markets will begin to stabilize and grow moderately in FY 2022 – FY 2025, as the City also projects to occur.

This forecast is highly uncertain and many questions regarding long term structural changes and their impacts on property markets remain unanswered. The extent to which firms and individuals will continue to rely on remote work and the resulting impact on the long term demand for office and residential properties is unknown. Will businesses rely on travel in the same way they did in the pre-pandemic world given that teleconferencing may be a viable and cheaper alternative in the future? To what extent will online sales continue to displace brick and mortar stores?

The answers to these and other questions will ultimately determine whether the downward market adjustments that occurred in 2020 will reverse, as reflected in our baseline forecast, or continue. One important risk to the forecast that should be noted is that almost 60 percent of Class 4 properties have actual assessed values below transitional values. Since property tax rates are applied against the lower of the actual assessed value or the phased-in transitional value, any further deterioration in market values would be reflected immediately, while any positive news would be phased in only gradually.

Real Estate Transaction Taxes

Sales of real estate properties in the City have begun a slow but steady recovery from the lockdown that brought the whole market to a halt in March and caused sales to collapse in the last quarter of FY 2020 (April-June 2020). Class 1 property sales (1-3 family homes) are up by 75 percent ($4.8 billion) during the second quarter of FY 2021 (October to December) compared to the last quarter of FY 2020 ($2.8 billion). Class 2 property sales (residential condos and coops) are up by 23 percent ($6.7 billion compared to $5.5 billion) and Class 4 property sales (commercial buildings) are up by 61 percent ($3.2 billion compared to $2 billion). Nonetheless, compared to the same quarter last year, sales are still lagging. Class 1 sales are flat whereas Class 2 sales are down by 28 percent and Class 4 sales are down by 61 percent.

The Comptroller’s Office’s near term projections for fiscal years 2021 and 2022 from the combined real property transfer and mortgage recording tax are very similar to the City’s forecast. After declining sharply by more than 19 percent in FY 2021, revenue is projected to rebound sharply in FY 2022, by almost 20 percent.

Thereafter, the Comptroller’s and City’s forecasts of the trajectory for the two taxes differ. The Comptroller’s Office projects that transaction taxes will remain below pre-COVID crisis levels throughout the Plan period. Class 1 sales have a better trajectory for recovery compared to Class 2 and Class 4 properties. The latter are likely to continue to face strong headwinds from increased reliance on work from home, while Class 1 could benefit from the remote work trend as homeowners seek more space at home. Mortgage recording taxes are projected to fare better in the short term as people continue to take advantage of low interest rates for refinancing, but as interest rates rise in the outyears this growth reverses. The City, on the other hand shows continued robust growth for these two taxes. Given this different trajectory, the outyear forecasts diverge, with the Comptroller estimating lower revenue compared to the City in each of FY 2023 – FY 2025, as shown in Tables 10 and 11.

Personal Income Tax

Both the Comptroller and the City have significantly revised their forecast for PIT in January, continuing the pattern of upward revisions that has occurred since last year’s Executive Budget forecast. The revisions largely reflect the fact that collections have come in stronger than originally anticipated (or alternatively, the significant losses that were originally projected due to the pandemic have not occurred).

There are several reasons that account for this unexpected strength. After initially dropping sharply at the onset of the pandemic, financial markets recovered quickly and by the end of the year stock market indices had soared to new record highs. The federal government provided an unprecedented fiscal boost to both persons and businesses: significantly increasing unemployment insurance compensation, providing Economic Impact Payments to low- and moderate-income individuals, and by helping businesses retain employees through the Paycheck Protection Program and through other tax credit programs. All these factors contributed to mitigating income tax losses that might otherwise have been much more significant. Rather than the projected double digit declines that were originally forecast for FY 2021, the Comptroller’s Office now anticipates PIT will decline by only 2.3 percent. The City projects a larger decline for FY 2021, in part because the City’s forecast does not incorporate the latest data for January PIT collections which continued to come in stronger than anticipated.

Looking forward, the projected recovery in the economy is expected to boost wage income and related withholding taxes. From FY 2022 to FY 2025 withholding is expected to increase by an average of five percent per year, boosted by a sharp rebound in 2022. The City’s overall forecast for withholding growth over the Plan is similar but the City’s projections are slightly lower in the near term and conversely higher in the outyears due to a more prolonged projected rebound in employment to pre-pandemic levels.

The non-withholding component of personal income, which is related mainly to capital gains and business income, is expected to experience only moderate growth over the Plan. After four years of strong and continued upward movements in the stock market, additional large gains may be harder to achieve with some analysts warning of bubbles[11]. As a result, the non-withholding component of PIT is expected to grow by only 1.3 percent on average. The City also projects moderate growth in non-withholding, but somewhat higher at 2.7 percent on average over the Plan. This forecast difference in non-withholding explains the Comptroller’s Office’s lower projections in the outyears, as shown in Tables 10 and 11.

Business Income Taxes

The forecast for the business taxes (General Corporation Tax and Unincorporated Business Tax) is also revised to reflect greater near-term strength and lower losses for reasons similar to those discussed regarding personal income taxes.[12] In particular, rather than declining as originally anticipated at the onset of the pandemic, Wall Street firm profits likely soared to the second highest level on record in FY 2021, second only to the profits realized in 2009 which were boosted by the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP).

In fiscal 2021 business taxes are projected to decline by 3.7 percent, a much lower decline than the losses originally anticipated. The outyear forecast assumes that a broader rebound in the local economy will help to offset lower profitability on Wall Street, and overall growth is expected to be a modest 1.1 percent on average. The Comptroller’s Office’s projections for the outyears is somewhat lower than the City’s, as shown in Table 11. As in the past, the Comptroller assumes higher growth in business taxes will occur in the form of audits rather than current collections, so overall, including audits, the projections for business tax revenue is similar to the City’s.

State, Federal Legislation, and Other Issues Impacting PIT and Business Taxes

The Governor’s proposed budget included a proposal that would potentially raise State PIT if Federal aid is not sufficient to help cover the projected deficits. Income over $5 million would be subject to a series of new brackets, up to 10.82 percent on income over $100 million. These brackets would apply for tax years 2021 through 2023, and taxpayers who prepaid their (estimated) liabilities this year would be eligible for credits against future tax liabilities beginning in 2024.

The State could also face significant impacts to its taxation of non-resident remote workers, from a Supreme Court decision in the case New Hampshire vs Massachusetts. Although the City cannot tax non-residents, the City could be indirectly impacted by this decision if existing City residents were to relocate in response to the decision.

The Governor also proposed a new SALT workaround proposal that would allow individuals to take advantage of the continued deductibility of S-Corp and partnership business taxes from their Federal taxes. In exchange for these newly imposed and deductible State taxes, individuals would receive a credit on their State PIT.[13]

A larger legislative issue that both the State and the City could face is the potential for significant tax reform to occur at the Federal level given that Democrats control both chambers of Congress. President Biden has indicated that he would increase taxes for high income individuals and corporations, while also considering some form of repeal to SALT limitations. The prospect of higher taxes could cause individuals to shift income across tax years, much like that which occurred in response to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. It is still too early to determine these impacts, but some taxpayers may have already hedged against future increases this year following the November election, betting on a Democratic win in Georgia. In other words, some of this year’s increase in PIT may be already due to income shifting.

In addition to these legislative proposals, the impact of remote work on population and residency patterns could also have significant effects on income and business taxes.

Sales Tax

While the forecasts for PIT and business taxes has been revised upwards in the current Plan, sales taxes were revised downwards as the effects of the pandemic on the hospitality sectors continue to drag down sales revenue. Sales tax revenue from hotels was 90 percent lower in the latest quarter compared to 2019 and restaurants reported that sales were 59 percent lower.[14] The recovery of the hospitality and entrainment sector is critical to the rebound in sales taxes and also explains the main difference between the Comptroller’s Office’s and the City’s forecast.

The Comptroller’s Office projects that hospitality employment will recover to 2019 pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2023, with projected annual growth of 22.9 percent and 34.3 percent in FY 2021 and FY 2022, while the City does not anticipate a recovery in the hospitality sectors to occur until after FY 2025. The City projects growth of only 16 percent and 20 percent in FY 2021 and FY2022.[15] As a result, the Comptroller’s Office anticipates higher sales tax growth throughout the Plan period, as shown in Tables 10 and 11.

The Governor’s proposed budget includes legislation to legalize and tax recreational cannabis. The legislation would enable the City to collect sales tax on retail sales of cannabis.[16] (For more detail see “State Executive Budget” beginning on page 22.)

Audit Revenues

The City’s forecast assumes that audit collections will decline from $921 million in FY 2022 to $721 million annually in the remainder of the Plan. The Comptroller’s Office’s forecast, while recognizing the volatility in individual audit collections, assumes that overall tax revenues should remain more closely in line with the $1 billion long term average of the past 10 years. As a result, the City could collect at least $200 million more in each year from FY 2023 – FY 2025.

Miscellaneous Revenues

Miscellaneous revenues in the FY 2022 Preliminary Budget remain relatively unchanged from the November Plan with a net decrease of $27 million to $4.98 billion. The reduction stems from downward revisions of $12 million and $16 million to estimates of sidewalk café fees and parking revenues, respectively.

In contrast, the FY 2021 miscellaneous revenue forecast is increased by a net $217 million, to $5.20 billion. This increase stems from a one-time reimbursement of $212 million by H+H for debt service. The reimbursement is credited as a revenue initiative in the Citywide Savings Program.

Table 12 shows the changes in the FY 2021 miscellaneous revenue projections since the November Plan. Revenue projections for licenses, permits and franchises decreased by a net $31 million. This revision reflects mostly lower projections for building and construction permits, cable television franchises and fees on sidewalk cafes. Projected revenues from charges for services decreased by $7 million. This includes lower projections for City register fees, event fees, and garage and long-term parking fees.

Table 12. Changes in FY 2021 Estimates

January 2021 Plan vs. November 2020 Plan

| ($ in millions) | November | January | Change |

| Licenses, Permits & Franchises | $680 | $649 | ($31) |

| Interest Income | 12 | 14 | 2 |

| Charges for Services | 975 | 968 | ($7) |

| Water and Sewer Charges | 1,720 | 1,720 | 0 |

| Rental Income | 245 | 245 | 0 |

| Fines and Forfeitures | 952 | 953 | 1 |

| Other Miscellaneous | 403 | 655 | $252 |

| Total | $4,987 | $5,204 | $217 |

After reaching $6.0 billion in FY 2019, miscellaneous revenue declined 12.3 percent in FY 2020 following a slowdown in business and social activities caused by the COVID-19 pandemic beginning in March 2020. The current year forecast of $5.2 billion represents a slight decline of 0.7 percent from the FY 2020 level. The City estimates miscellaneous revenue will decline another 4.0 percent in FY 2022 as result of the one-time H+H reimbursement in FY 2021. Net of the H+H reimbursements, miscellaneous revenues are projected to remain relatively flat at around $5 billion through FY 2025.

Federal and State Aid

The January Financial Plan projects total Federal and State aid of $26.98 billion in FY 2021, supporting nearly 28.4 percent of the City’s expenditure budget. Compared with the November Plan, the City has reflected an increase of $1.08 billion in the current year, comprised of $909 million in Federal aid and $169 million in State grants. A significant portion of the increased Federal funding stems from the continued recognition of COVID-related reimbursement totaling $541 million, including $213 million in FEMA reimbursement and $312 million in Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity grants under the CARES Act. The residual Federal aid increase mainly includes $138 million in Community Development Block Grant funding and $170 million in social services grants. Under State grants, the January Modification reflects increases of $42 million for social services, $32 million for health and mental hygiene and $95 million for other areas mostly in reimbursement for indigent legal services and assigned counsel payments.

In the FY 2022 Preliminary Budget, the City assumes $23.4 billion in Federal and State assistance, reflecting a modest increase of $124 million since the November Plan. The increase primarily consists of $38 million in Federal school food revenue, $27 million in Homeland Security grants and $31 million in State early intervention services reimbursement. Federal and State grants would support about 25 percent of the expense budget in FY 2022, which will ultimately increase once additional COVID-related assistance is reflected. Overall, the January Plan assumes about $3.63 billion in Federal COVID-related reimbursement, including $1.9 billion in CARES Act funds and $1.7 billion in FEMA grants for the reimbursement of 75 percent of eligible COVID-related spending. However, the Plan does not reflect potential grants from actions taken by the Biden administration to provide budget relief to states and localities. Since the release of the January Plan, the President has signed an executive order to ensure full FEMA coverage for eligible COVID-related costs, which is expected to provide about $1 billion in additional reimbursement to the City. In addition, the current Federal aid assumptions have not yet accounted for potential resources stemming from the Biden Administration’s stimulus package proposal, which earmarks $350 billion in support to state and local governments.

Over the remainder of the Plan, Federal and State grants are projected to rise to $23.71 billion in FY 2023 and remain basically flat thereafter, primarily because the City has assumed no State education aid growth beyond FY 2023. Based on these projections, Federal and State support for the City’s expense budget would decline to an average of 23 percent in FY 2023 – FY 2025.

State Executive Budget

Governor Andrew Cuomo unveiled his Executive Budget for State fiscal year (SFY) 2022 on January 19, 2021. The proposal would close a projected $15 billion gap over the current year and next year by adopting temporary tax increases, cutting State spending, using prior allocations of Federal COVID-19 relief, and assuming that more Federal support is on the way.

President Biden has proposed a new $1.9 trillion federal stimulus package, which would include $350 billion in unrestricted aid for states and local governments. However, the timing and actual size of any additional Federal relief is uncertain. Amid this uncertainty, the proposed State budget is premised on receiving at least $6 billion in flexible, emergency Federal aid. The State Division of Budget (DOB) assumes that these funds would be evenly divided between SFYs 2022 and 2023.

If New York State receives less than the budgeted $3 billion in unrestricted Federal COVID-19 relief as of August 31, 2021, the budget proposal would once again authorize the State to implement across-the-board local aid reductions. Certain categories of spending, including school aid and public assistance, would be exempt. Alternatively, if the State receives at least $15 billion in unrestricted Federal aid, then proposed state cuts and tax increases could be rescinded.

Under the assumption that the State receives at least $3 billion in additional relief by next year, the State budget as proposed could have a positive impact on the City’s Financial Plan of $46 million over FY 2021 and FY 2022, as shown in Table 13.

Table 13. Potential Impact of Proposed FY 2022 State Budget

| ($ in millions) | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | Total Two-Year Impact |

| Education Aid | |||

| Formula-based School Aids* | ($93) | $547 | $455 |

| Other Education Aids | ($156) | ($87) | ($243) |

| Subtotal Education Aid | ($249) | $461 | $212 |

| Cost Shifts | |||

| State Share of Federal Public Indigent Care Pool | ($15) | ($61) | ($76) |

| Child and Family Assistance Programs | ($9) | ($35) | ($44) |

| Public Health Reimbursement | ($5) | ($25) | ($30) |

| Transit Operating Aid | ($2) | ($6) | ($8) |

| Mental Hygiene | ($1) | ($4) | ($5) |

| Other Human Services | ($1) | ($3) | ($4) |

| Subtotal Cost Shifts | ($32) | ($133) | ($166) |

| Total Impact | ($281) | $327 | $46 |

*Includes funding from Federal COVID-19 Supplemental Act.

Source: NYS Division of Budget and NYC Office of Management and Budget

School Aid

As proposed in the Executive Budget, total school aid to New York City would be $12.7 billion in FY 2022, an increase of 13 percent, or $1.5 billion, from the current year and $547 million higher than the current assumption in the City’s Financial Plan. The higher-than-expected increase results from the allocation of Federal COVID-19 relief funds, offset by cuts to State education support (Table 14).

Table 14. Variance Between Proposed School Formula Aids

and City January Plan Projections, FY 2022

| ($ in millions) | |

| Proposed State Aid Changes | |

| Foundation Aid | ($857) |

| Expense-based Aid | (569) |

| All Other Formula Aids | (33) |

| Local District Funding Adjustment | (144) |

| Total State Aid Changes | ($1,603) |

| Federal COVID-19 Supplemental Act Funds | $2,150 |

| Net Impact | $547 |

Source: NYS Division of Budget and NYC Office of Management and Budget.

Note: The numbers in the table above represent the difference between proposed state school aid in the State’s Executive Budget and the City’s forecast as of the January 2021 Financial Plan.

As part of the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations (CRRSA) Act that was approved in December 2020, New York State received $4.3 billion for elementary and secondary education, including $4.0 billion through the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) Fund and $323 million through the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief (GEER) Fund. At least 90 percent of these ESSER funds must be allocated to school districts based on the distribution of Title I awards. States also cannot reduce the share of state spending dedicated to education below the average of FYs 2017 through 2019.

Under the Governor’s proposal, the State would allocate $3.85 billion of the CRRSA education relief funds to school districts, of which New York City would receive $2.15 billion. However, the additional Federal support would be offset by a “local district funding adjustment” that equals the lesser of the district’s reimbursement for the School Tax Relief (STAR) program or the Federal stimulus payment. The State estimates that New York City’s STAR payment will be $144 million in FY 2022, while the City’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has a slightly higher forecast of $152 million. The local district funding adjustment would continue past FY 2022, effectively eliminating the annual state reimbursement for STAR (Chart 5).

Chart 5. Actual and Proposed New York State School Aid

($ in billions)

* Actual

Note Includes actual and projected funding for all school districts in New York State. New York State Division of Budget does not publish outyear school aid projections for individual school districts.

Source: New York State Division of Budget, FY 2022 Executive Budget Financial Plan and prior financial plan updates.

The Executive Budget also proposes to consolidate and reduce 11 expense-based school aid categories, including transportation aid. Compared to the current assumption in the City’s financial plan, expense-based school aid would be $569 million less than projected in FY 2022. Foundation Aid would also be frozen for the second consecutive year in FY 2022 at $8.1 billion, $857 million below the City’s forecast.

Outside of formula-based school aids, the Executive Budget proposes to eliminate charter school facility aid, which OMB forecasts at $64.2 million in FY 2021 and $37.9 million in FY 2022 and beyond. The Executive Budget argues that State rental aid provides a disincentive to co-locating charter schools in under-utilized public school buildings. In addition, the City indicates the State Executive Budget would reduce support for pupil transportation costs during school shutdowns that could result in a loss of $92 million in FY 2021. Other education proposals include the elimination of the City’s fiscal stabilization grant and eliminating prior-year school aid claims.

The State has also proposed a one-time reduction in state-mandated tuition payments from school districts to charter schools in FY 2022. The payment would be reduced by the percent that the proposed “local district funding adjustment” and the expense-based aid reduction collectively reduce total school district expenditures. The savings would be split evenly between the State and school districts. The State estimates that New York City would save $32.7 million in FY 2022. However, because the City has not fully funded charter school tuition increases in the outyears of the January Plan, it is unclear how much savings will materialize.

The State has also proposed for the second consecutive year to exclude the reissuance of surrendered, revoked, or terminated charters from the New York City charter school cap. In 2015, a similar provision allowed an additional 22 charters to be reissued to charter schools that had lost their charter before July 1, 2015.[17] The Governor’s proposal would enable about 20 charter schools that have closed since July 1, 2015 to reopen without having to raise the cap. As of early 2019, New York City reached the State-imposed limit on charters and therefore no additional charter schools can be authorized in the City.

Other Costs to the City

Other cost shifts to New York City would subtract $133 million in State funds from New York City in FY 2022, including the elimination of the state share of the federal Public Indigent Care Pool, a 5 percent reduction in various local aid programs, and a reduction in State reimbursement for public health programs. The Executive Budget would reduce New York City’s General Public Health Work (GPHW) reimbursement rate for core public health services, such as disease prevention, community health assessments, and communicable disease control, from 20 percent to 10 percent above the base grant, resulting in an annual loss of about $25 million. Previously, in the adopted budget for FY 2020, the State lowered the City’s GPHW reimbursement rate from 36 percent to 20 percent at an ongoing cost of $59 million per year.

Revenues

On the revenue side, for the third consecutive year, the Governor included legislation in the Executive Budget to legalize and tax the sale of cannabis for adults over 21 years old. The Governor proposed imposing two taxes: a wholesale tax based on THC content and a State surcharge on retail sales. The first tax would vary by category. The rate would be $0.04 per milligram of THC for edibles; $0.01 per milligram for concentrates; and $0.007 per milligram for cannabis flowers. Sales of cannabis products would also be subject to a 10.25 percent State surcharge on the retail price. Unlike proposals in prior years, cannabis sales would be subject to the City and State sales tax.

The State expects to begin collecting $20 million in new revenue in SFY 2022, rising to $118 million in SFY 2023, $162 million in SFY 2024, $252 million in SFY 2025, $350 million in SFY 2026, and $374 million in SFY 2027. A specified dollar amount would first be distributed to a Cannabis Social Equity Fund — $10 million in SFY 2023, $20 million in SFY 2024, $30 million in SFY 2025, $40 million in SFY 2026, and $50 million in each subsequent year. Additional revenues would be deposited into a Cannabis Revenue Fund and could be used for the following purposes: administration of the regulated cannabis program, data gathering, monitoring and reporting, the Governor’s Traffic Safety Committee, implementation and administration of the initiatives and programs of the social and economic equity plan in the Office of Cannabis Management, substance abuse, harm reduction and mental health treatment and prevention, public health education and intervention, research on cannabis uses and applications, program evaluation and improvements, and any other identified purpose recommended by the executive director of the Office of Cannabis Management and approved by DOB.

The Comptroller’s Office has estimated that the market for adult-use marijuana in New York City would be about $1.1 billion. Consequently, once the existing underground market transitions to the legal market, the legalization of cannabis could generate approximately $50 million per year in local sales tax for the City.

Other revenue proposals in the Governor’s budget are discussed above in “State, Federal Legislation, and Other Issues Impacting PIT and Business Taxes“ on page 20.

Expenditures Analysis