Culture Shock: The Importance of National Arts Funding to New York City’s Cultural Landscape

Executive Summary

“I look forward to an America which will steadily raise the standards of artistic accomplishment and which will steadily enlarge cultural opportunities for all of our citizens. And I look forward to an America which commands respect throughout the world not only for its strength, but for its civilization as well.” – President John F. Kennedy in 1963, laying out his vision for what would become the National Endowment for the Arts.

Two years after President Kennedy spoke these words, the National Endowment for the Arts (N.E.A.) was founded. It was tasked with a broad and lofty mission – to encourage arts scholarship, expand arts education, and support arts programming across the United States. To this day, the N.E.A. plays a critical role in preserving the nation’s cultural heritage and expanding access to this rich artistic legacy.

Since the election of President Trump, threats to shutter the N.E.A. have been well publicized. The President’s transition team targeted the Endowment—as well as the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and National Endowment for the Humanities—as a potential target for elimination, and a recent memo from the White House budget office confirmed these intentions.[1]

This report by New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer argues that eliminating the N.E.A. would have a significant impact on the City, disrupting funding for hundreds of cultural organizations and jeopardizing programs for the millions of New Yorkers they serve. Organizations supported by the N.E.A. have an outsized impact on the city, delivering arts programming and education in scores of neighborhoods, spurring creativity and critical thinking, and providing thousands of jobs to local residents.

Specifically, this report found that:

- New York City cultural non-profits are major beneficiaries of N.E.A. grants, receiving $14.5 million in fiscal year 2016 and $233.2 million from 2000 to 2016.[2]

- E.A. funding for New York City cultural organizations spanned a variety of disciplines from 2000 to 2016, with Media Arts receiving the largest share ($42.5 million) followed by Theater & Musical Theater ($32.4 million), Dance ($31.2 million), and Music ($21.3 million).[3]

- Over $21 million was granted specifically for Arts Education, though a significant share of funding for other disciplines was also used toward educational programming.[4]

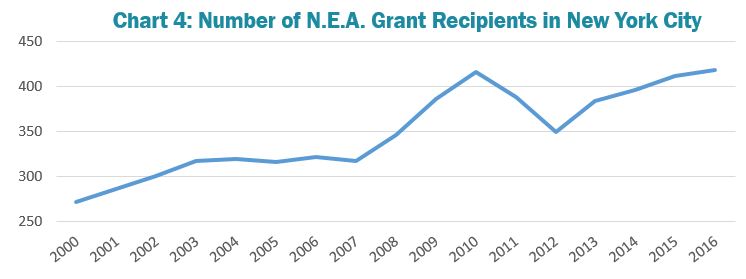

- Over the last sixteen years, N.E.A. funding levels have remained fairly steady, although the number of recipients based in New York City has grown significantly—from 272 in 2000 to 419 in 2016.[5]

- Over this period, the number of Brooklyn and Bronx organizations receiving grants more than doubled, while the number of Queens recipients increased by 43 percent. In 2016, 28 percent of all N.E.A. grantees were based outside of Manhattan, up from 19 percent in 2000.[6]

- Performing arts companies, museums, and historic sites—all beneficiaries of N.E.A. grants – are collectively among the largest employers in the city. In 2016, they maintained a staff of 30,154 and paid $453.4 million in total wages.[7]

- Nearly 30 million tourists visited a cultural organization in 2015 and collectively spent $5 billion on arts, recreation, and entertainment while visiting the five boroughs.[8] The tourism industry sustains more than 375,000 jobs citywide.[9]

Though the N.E.A. is hardly the largest donor to arts and culture in New York City, its grants represent an important imprimatur for nonprofits of all sizes. The competitiveness of the selection process and prestige of the N.E.A. invariably attracts additional foundation, corporate, and individual giving. For organizations like Arts East New York, DreamYard, Bronx Council on the Arts, and The Laundromat Project (all profiled in this report), grants from the N.E.A. elevated their profile, attracted new funding, and amplified their impact.

In short, the cultural ecosystem the N.E.A. supports is essential to the vitality of New York City and the nation at-large. From the school house to the retirement home, the arts provide a medium for self-understanding and self-expression. They are a means for engaging different cultures and heritages as well as cultivating and sustaining a collective identity.

A robust and healthy cultural sector supports a robust and healthy democracy and economy. New York City is a testament to this linkage. The elimination of the N.E.A. would be broadly felt, in every borough and in every museum, theater, school, and community.

The History and Reach of the N.E.A.

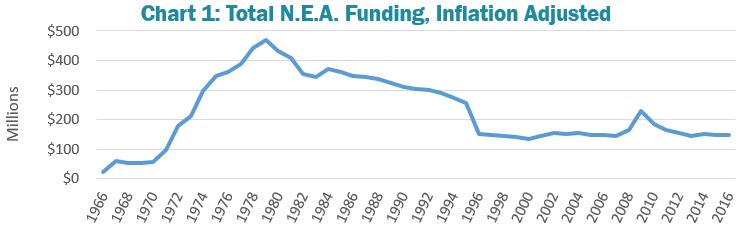

Funding for the N.E.A. has fluctuated over the course of its history. From 1966 to 1979, the agency’s budget rose as high as $470.9 million, adjusted for inflation (see Chart 1). This trajectory was dramatically altered in 1981 and again in 1996, when prominent lawmakers called for the complete elimination of the N.E.A.[10]

While the agency ultimately persisted, severe budget cuts were enacted. By 1996, the N.E.A.’s budget had fallen to $151.4 million (inflation adjusted). In addition to funding cuts, the 1996 reforms prohibited grant funding for individual artists or operating support for organizations.[11]

Source: National Endowment for the Arts and USDOL “Consumer Price Index – All Urban Consumers”

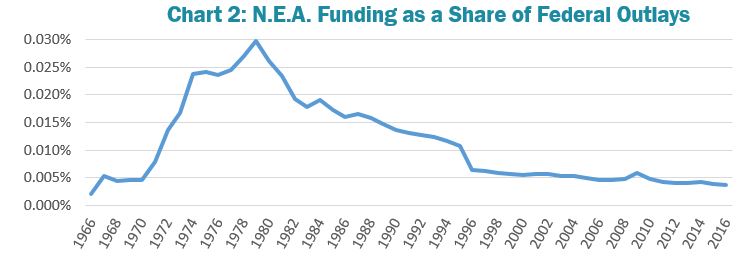

The N.E.A. budget has stabilized over the last two decades, and stood at $148 million in fiscal year 2016. The scale of its budget continues to shrink, however, when viewed as a share of total government spending. Today, the N.E.A. budget represents a mere .0037 percent of total federal outlays, down from a peak of .03 percent in 1979 (see Chart 2).[12]

Source: National Endowment for the Arts and U.S. Office of Management and Budget

Though just a small share of the federal budget, N.E.A. funding has an outsized impact, stretching from coast to coast and targeting programs and people with the greatest needs. Thirty-six percent of its grants go to organizations that reach underserved populations, such as those with disabilities, people in institutions, and veterans. Sixty-five percent go to small and medium sized organizations and forty percent fund programs that take place in high-poverty communities.[13]

On a per capita basis, cultural organizations in the Great Plains generally receive the most N.E.A. funding, with Wyoming ($1.34 in grant funding per capita), South Dakota ($1.12), Montana ($1.02), and North Dakota ($0.99) all ranking in the top seven among American states in 2016.[14]

New York received the eleventh most funding from the N.E.A. on a per capita basis, though its overall funding has consistently been the highest in the nation. This is largely driven by the high concentration of arts and culture nonprofits residing in the state. Of the 45,995 active cultural nonprofits in the United States, 11 percent are located in New York, with 6 percent in the five boroughs.[15]

N.E.A. Funding per Capita in 2016

| State | Grant Funding per Capita | Total Grant Funding |

| Vermont | $1.61 | $1,003,800 |

| Alaska | $1.46 | $1,086,000 |

| Wyoming | $1.34 | $783,700 |

| Rhode Island | $1.14 | $1,209,500 |

| South Dakota | $1.12 | $966,600 |

| Montana | $1.02 | $1,061,600 |

| North Dakota | $0.99 | $752,100 |

| Minnesota | $0.96 | $5,320,600 |

| Maine | $0.90 | $1,194,400 |

| Delaware | $0.87 | $833,000 |

| New York | $0.87 | $17,090,175 |

Source: National Endowment for the Arts

The Impact of the N.E.A. in New York

Since its founding, the N.E.A. has been closely linked to the Empire State. New York Senator Jacob Javits was among its original champions and helped draft its authorizing legislation. The New York State Council on the Arts, established in 1960, served as an early inspiration. The American Ballet Theater, based in Manhattan, was its first grant recipient in 1965.[16]

New York City, in particular, is a major beneficiary of N.E.A. funding. Its cultural nonprofits received $233.2 million from 2000 to 2016. Manhattan organizations led the way with $189.5 million in funding, followed by Brooklyn ($34 million), the Bronx ($5.6 million), Queens ($3.3 million), and Staten Island ($774,500).[17]

N.E.A. funding for New York City cultural organizations spanned a variety of disciplines. Media Arts received the largest share of grants, totaling $42.5 million from 2000 to 2016. It was followed by Theater & Musical Theater ($32.4 million), Dance ($31.2 million), and Music ($21.3 million). Over $21 million was granted specifically for Arts Education, though a significant share of funding for other disciplines was also used toward educational programming.

CASE STUDY #1: Arts East New York

Cafes, artist studios, food vendors, film screenings, yoga classes. The ReNew Lots Market transformed a once abandoned lot in East New York into a vibrant community space, business incubator, and arts hub. Spearheaded by Arts East New York (AENY), it is a bold example of community-led economic development, launching the career of four local entrepreneurs who have since moved into brick and mortar stores.In 2016, AENY was awarded a sizable grant from the N.E.A., allowing them to substantially expand the size and ambition of ReNew Lots. The grant raised the national profile of the organization and inspired similar projects in Oakland and Miami.

In addition to extending the reach of ReNew Lots, the N.E.A. grant has fortified AENY and attracted new supporters. Several foundations reached out to AENY following the N.E.A. announcement, with one providing additional funding for ReNew Lots. The grant also helped lure two new members to AENY’s board.

“As a small arts organization in a community that has suffered years of divestment, the N.E.A. grant validated the work we’re doing,” explains Catherine Green, Founder and Executive Director of AENY. “It opened up funding streams that weren’t previously available and helped us become a model for other communities.”

N.E.A. Grant Funding to NYC Cultural Organizations, by Discipline

| Discipline | FY2000-FY2016 |

| Media Arts | $42,534,080 |

| Theater & Musical Theater | $32,449,230 |

| Dance | $31,221,273 |

| Music | $21,278,533 |

| Arts Education | $21,057,289 |

| Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works | $17,595,813 |

| Literature | $14,216,210 |

| Museum | $12,381,624 |

| Visual Arts | $11,524,235 |

| Folk & Traditional Arts | $7,705,775 |

| Design | $5,841,586 |

| Opera | $5,741,936 |

| Other | $9,637,884 |

| Total | $233,185,468 |

Source: National Endowment for the Arts

Over the last sixteen years, N.E.A. funding has been fairly steady. Grants to New York City hovered between $13 million and $17 million throughout the period, with the exception of a bump from the post-recession fiscal stimulus (see Chart 3).

Source: National Endowment for the Arts

The number of N.E.A. grant recipients, on the other hand, grew at a steady rate over this period, reaching more small and mid-sized arts organizations. In 2000, 272 of New York City’s cultural nonprofits received funding from the N.E.A. In 2016, 419 were awarded a grant (see Chart 4).

Source: National Endowment for the Arts

Over this period, the number of Brooklyn and Bronx organizations receiving grants more than doubled while the number of Queens recipients increased by 43 percent. In 2016, 28 percent of all N.E.A. grantees were based outside of Manhattan, up from 19 percent in 2000.

From Lincoln Center to Arts East New York, The Met to The Laundromat Project, the N.E.A. supports New York City cultural organizations large and small. Its grants are a catalyst for additional public and private funding, allowing local organizations to expand their programming, experiment with new projects, and reach New Yorkers in every community.

CASE STUDY #2: Bronx Council on the Arts

Since 1962, the Bronx Council on the Arts (BCA) has nurtured the development of local artists and arts organizations, improved access to the arts, and elevated the voices of Bronx residents. Over the years, many of its signature programs have been funded and sustained by the N.E.A. These include the Longwood Arts Project, a gallery and residency program that helped launch the careers of two MacArthur Fellows, and the Bronx Trolley, a monthly tour of South Bronx’s “Cultural Corridor.”More recently, the N.E.A. provided seed funding for their Bronx Memoir Project, a series of workshops to nurture aspiring writers and help local residents share their stories. The project “gave voice to the marginalized. To those who may not consider themselves writers, but have an urgent tale,” says Charlie Vázquez, Director of BCA’s Bronx Writers Center.

Following the workshops, fragments from over 50 memoirs were collected into an anthology. The collection has sold well, providing an unexpected stream of income to BCA and extending the impact of the N.E.A. grant.

CASE STUDY #3: The Laundromat Project

Art is more than an object or a performance. It is also a platform, bringing people together and helping them engage. Art is not just housed in distant museums or theaters; it can be found on every street in every community. These values underpin The Laundromat Project, which works with local artists to mount projects and educational programs in laundromats, beauty shops, and community gardens throughout the city.When The Laundromat Project received its first N.E.A. grant in 2012, it was a small operation with only one employee. Support from the Endowment changed that, providing a catalyst for additional funding and helping it expand seven-fold. With a larger staff, the organization has dramatically increased its impact, launching ambitious projects from Harlem to Bedford Stuyvesant.

Bronx-based teaching artist Sharon de la Cruz and local residents participating in an art workshop at The Laundromat Project’s 920 Kelly Street space for 2016 Hunts Point Field Day. Photo by Osjua Newton.

“We knew we had something to offer, but needed support to grow,” explains Kemi Ilesanmi, The Laundromat Project’s Executive Director. “The beautiful thing about the N.E.A. is that it ‘credentializes’ and stabilizes. We were recognized as an asset and had the confidence and support to move forward.”

Eliminating the N.E.A. Would Harm New York City

Since the November 2016 elections, calls to shutter the N.E.A. have been well publicized. A recent memo by the White House budget office listed the Endowment—as well as the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and National Endowment for the Humanities—as a potential target for elimination.[18]

If enacted, these cuts would have a significant impact on New York City, disrupting funding for hundreds of cultural nonprofits that enliven city neighborhoods and provide thousands of jobs to local residents

Performing arts companies, museums, and historic sites—all beneficiaries of N.E.A. grants—are among the largest employers in the city. In 2016, they maintained a staff of 30,154 and paid $453.4 million in total wages.[19] Their exhibits, performances, and educational activities enrich the lives of local residents as well as those from outside the region, attracting millions of tourists each year.

According to NYC & Company, the City’s official marketing and tourism organization, “nonprofit cultural institutions have long been an integral part of the fabric and identity of the City—and an enormous draw to visitors, attracting almost half of all visitors to the five boroughs.”[20] Nearly 30 million tourists visited a cultural organization in 2015 and collectively spent $5 billion on arts, recreation, and entertainment while visiting the five boroughs.[21] Overall, the tourism industry sustains more than 375,000 jobs citywide.[22]

Beyond jobs and tourism, the cultural ecosystem that that N.E.A. supports is essential to the health and vitality of New York City and the nation at-large. From the school house to the retirement home, the arts provide a medium for self-understanding and self-expression. They are a means for engaging different cultures and heritages as well as cultivating and sustaining a collective identity.

A robust and healthy cultural sector supports a robust and healthy democracy and economy. New York City is a testament to this linkage. The elimination of the N.E.A. would be broadly felt, in every borough and in every museum, theater, school, and community.

CASE STUDY #4: DreamYard

DreamYard’s impact on arts education in the Bronx cannot be overstated. It partners with over 40 public schools, helping integrate the arts and social justice into their core curriculum. Its Art Center in Morisania provides theater, poetry, fashion, music production, arts activism, and dance programs to over 300 local youth. Its art festivals allow hundreds of students to showcase their work each year for thousands of family and community members.At a number of critical junctures, DreamYard has leaned on the N.E.A. to help expand its core programming and experiment with new projects. One grant allowed it to quadruple the capacity of its Art Center, extending programming to six days a week. With another grant, it introduced a new training program for elementary school teachers in 16 schools. With another, it forged a partnership with the Parsons School of Design to buildout its digital learning program.

Visitors at the Bronx Arts Festival, an annual DreamYard event hosted at Lehman College. Photo by David Flores.

The N.E.A. plays an essential role in catalyzing these partnerships and programs, helping youth in every community engage with the arts. “The N.E.A.’s impact on arts education is so vital,” explains Tim Lord, Co-Executive Director of DreamYard. “The N.E.A. helps young people find their voice and build pathways to life-long opportunity. It helps them create and share and reflect on their work. It helps them engage and learn from one another. That’s really powerful.”

Acknowledgements

Comptroller Scott M. Stringer thanks Adam Forman, Associate Policy Director and the lead writer of this report, and David Saltonstall, Assistant Comptroller for Policy. Comptroller Stringer also recognizes the important contributions to this report made by: Jennifer Conovitz, Special Counsel to First Deputy Comptroller; Vesna Petrin, Special Assistant to the Chief of Staff; Zachary Schechter-Steinberg, Deputy Policy Director; Devon Puglia, Director of Communications; Tyrone Stevens, Press Secretary; Nicole Jacoby, First Deputy General Counsel; and Antonnette Brumlik, Senior Web Administrator.

Cover Illustration: Students at the DreamYard Art Center in Morrisania, Bronx. Photo by David Flores.

Endnotes

[1] Bolton, Alexander. “Trump team prepares dramatic cuts,” The Hill. January 19, 2017.

Cooper, Michael. “Arts Groups Draft Battle Plans as Trump Funding Cuts Loom,” The New York Times. February 19, 2017.

[2] National Endowment for the Arts, “NEA Online Grant Search.” https://apps.NEA.gov/grantsearch/

[3] ibid

[4] ibid

[5] ibid

[6] ibid

[7] United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages,” Q2, 2016.

[8] Interview with Donna Keren, Senior Vice President for Research & Analysis, NYC & Company.

[9] “Mayor de Blasio Announces Total NYC Visitors Surpasses 60 Million for First Time.” December 19, 2016. http://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/963-16/mayor-de-blasio-total-nyc-visitors-surpasses-60-million-first-time

[10] National Endowment for the Arts. “National Endowment for the Arts Appropriations History.” https://www.arts.gov/open-government/national-endowment-arts-appropriations-history

[11] Ibid

And for inflation adjustment, USDOL “Consumer Price Index – All Urban Consumers”

[12] Ibid.

And for the total federal budget: Office of Management and Budget. “Fiscal Year 2017. Historical Tables. Budget of the U.S. Government.”

[13] https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/N.E.A.-quick-facts.pdf

[14] National Endowment for the Arts, “NEA Online Grant Search.” https://apps.N.E.A..gov/grantsearch/

[15] National Center for Charitable Statistics. “Registered Nonprofit Organizations by State.”

An “active” nonprofit is one that filed Form 990 in the last two years and reported more than zero revenue and assets.

[16] Bauerlein, Mark and Ellen Grantham. “National Endowment for the Arts: A History 1965-2008.” National Endowment for the Arts. 2008. https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/N.E.A.-history-1965-2008.pdf

[17] NEA Online Grant Search

[18] Cooper, Michael. “Arts Groups Draft Battle Plans as Trump Funding Cuts Loom,” The New York Times. February 19, 2017.

[19] United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages,” Q2, 2016.

[20] NYC & Company. “A Model for Success,” June 2013. http://www.nycgo.com/assets/files/pdf/New_York_City_Tourism_A_Model_for_Success_NYC_and_Company_2013.pdf

[21] Interview with Donna Keren, Senior Vice President for Research & Analysis, NYC & Company.

[22] “Mayor de Blasio Announces Total NYC Visitors Surpasses 60 Million for First Time.” December 19, 2016. http://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/963-16/mayor-de-blasio-total-nyc-visitors-surpasses-60-million-first-time