Economic Benefits of Immigration Legal Services

Introduction

For over a decade, New York City has been a national leader in providing immigration legal services.[i] New York City has made more investments in immigration legal services than any other city in the U.S. The City’s pioneering work to provide universal representation to residents in immigration detention and its historic investments in immigration legal services more broadly have helped thousands of New Yorkers stabilize their lives, remain with their families, and continue contributing to our local economy.[ii]

Over the last two years, the City has welcomed tens of thousands of new asylum seekers who are in urgent need of immigration legal services.[iii] New arrivals are in need of immediate legal assistance to screen and apply for appropriate relief (e.g. asylum, Temporary Protected Status, or Special Immigrant Juvenile Status), and to apply for work authorization. Many will also need assistance as their cases wind their way through the backlog of the dysfunctional U.S. immigration system.

Guaranteeing access to counsel in removal proceedings for all New Yorkers as well as making additional investments in immigration legal services can benefit New York City’s economy by keeping workers in the workforce, getting new arrivals work authorization, keeping families together, and providing pathways to upward mobility.

This report highlights the potential economic benefits of the New York State Access to Representation Act (S.999/A.170) and of providing immigration legal services to asylum seekers in City shelters.[iv] We examine the potential impact of ensuring that everyone facing deportation proceedings has representation in New York State immigration courts and the potential earning power of new arrivals in shelter upon receiving work authorization.

Key Findings

- Providing access to attorneys for all immigrants in New York State facing deportation proceedings would likely result in an additional 53,000 New Yorkers being able to remain in communities across the state.

- Preventing deportation of these 53,000 New Yorkers, would result in an estimated net benefit of $8.4 billion for the federal, state, and local governments, calculated as the net present value over 30 years of new tax revenues less services received.

- The approximate earning potential of asylum seekers in City shelters is over $382 million and could rise to over $470 million if they were all to obtain work authorization.

Access to Representation Act

New York State has one of the highest rates of representation nationally in immigration court.[v] Still, many New Yorkers still face deportation proceedings without an attorney, leaving many navigating our complex immigration system on their own. Making accurate legal arguments and presenting a strong case in court without an attorney is difficult for anyone, and nearly impossible for people who are detained, have limited resources, or do not speak English.

This especially true for new arrivals. Most of the over 180,000 newly arrived asylum seekers are currently in a massive backlog of cases in immigration court.[vi] New arrivals have up to one year from arrival to submit applications for asylum, and they become eligible to apply for work authorization after their asylum applications have been pending six months.[vii] Due to the backlog of asylum cases, the average wait time to the first immigration court hearing for an asylum seeker is estimated to be four years.[viii] Even if they have applied for asylum, many of the city’s newest arrivals are in a backlog of deportation proceedings and at risk of removal.[ix] Without sufficient investments in legal representation, many of them will face removal proceedings without access to an attorney.

In addition to new arrivals, any non-citizen, including lawful permanent residents (green card holders), refugees, and people who entered legally on visas, can be placed in deportation proceedings.[x] There is no statute of limitations on removals, so noncitizens may be at risk of removal no matter how long they have lived in the U.S.[xi] There have even been cases where federal immigration authorities wrongly deported U.S. citizens.[xii]

Detention and deportation mean loss of freedom, permanent separation from families and communities, and possible return to dangerous conditions in another country. Even with the stakes this high, people facing deportation – including children and people with disabilities – are not guaranteed an attorney in immigration court.

The Access to Representation Act (S.999/A.170) is a New York State bill to guarantee that any New Yorker facing deportation has a right to an attorney.[xiii] If passed, the Access to Representation Act would establish a statewide right to representation in removal proceedings, meaning anyone at risk of deportation who cannot afford a lawyer will be provided one by the State. The law will also guarantee stable funding streams for immigration legal services and includes a “ramp-up” period to help build capacity and ensure sustainability, easing uncertainty for both attorneys and their clients.

Legal representation is a gamechanger for those who would otherwise have to face removal proceedings alone – people have a much higher chance of winning their immigration case when they are represented by an attorney.[xiv] Guaranteeing legal representation also helps make immigration proceedings more efficient, thereby helping to alleviate the massive backlog of cases.

The quicker cases get resolved, the quicker immigrant New Yorkers can get back into the workforce, get access to the legal protections for which they qualify, and contribute to our economy.[xv]

The Access to Representation Act will also help address stark racial disparities in our immigration legal system. Black immigrants are more likely than non-Black immigrants to be detained and deported on the basis of previous criminal convictions.[xvi] For example, although Black immigrants comprise just 5.4% of undocumented population in the U.S., and 7.2% of the total noncitizen population, they represented 10.6% of all immigrants in removal proceedings between 2003 and 2015.[xvii] Immigrants from majority-Black countries also experience disparate treatment when seeking asylum.[xviii]

According to a survey conducted by the Vera Institute of Justice, 93% of New Yorkers believe that access to attorneys for all people, including those in immigration court, is important, and support government-funded attorneys for them.[xix]

The Costs of Deportation

Deportations create enormous social and economic costs. Deportations lead to more foreclosures, evictions, and children entering the foster care system.[xx] The negative mental health impacts of deportation on deportees[xxi], their children[xxii] and loved ones, and their broader communities[xxiii] are well documented. Immigration enforcement has downstream impacts on families’ health, mental health, finances, work, and school performance that decrease productivity in our economy.[xxiv]

In addition to preventing tremendous human costs, research has shown that keeping immigrant families together saves money for local governments with increased tax revenue and less need for families to rely on the social safety net.[xxv] Employers also benefit from avoiding lost productivity and having to replace workers.

Immigration is a boon for New York City’s economy.[xxvi] Immigrants are more likely to work, start a business, and contribute billions of dollars into our New York economy in spending power and tax revenue.[xxvii] Deportations could make existing worker shortages in New York worse, as immigrants are overrepresented in the labor force and dominate in essential work and the care economy.[xxviii]

The impacts of deportations on tax revenue, government spending, consumer spending, and workforce growth would all be negative consequences for New York’s economy.[xxix] A policy of large-scale deportation could result in a loss to New York State of $40 billion in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over ten years.[xxx] On a national level, GDP would be reduced by an estimated 1.4 percent in the first year, and cumulative GDP would be reduced by an estimated $4.7 trillion over 10 years.[xxxi]

Economic Impacts of the Access to Representation Act

With a finite number of dedicated immigration attorneys and a significant backlog in immigration court, the rate at which persons facing removal proceedings have legal representation is falling.

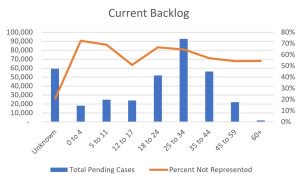

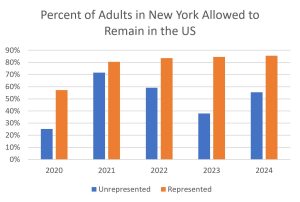

The current backlog in New York State-based immigration courts is about 350,000 people, of whom only 45% (156,000) have indicated that they are represented by an attorney.[xxxii][xxxiii] There is consistent, compelling evidence that people facing deportation are more likely to receive a judgment that allows them and their families to stay in the country if they have representation.[xxxiv] From 2019 to present, persons facing charges in immigration court in the state of New York with legal representation have been 61% more likely to receive a judgment that results in their being allowed to stay in the country than those without representation; 45% of unrepresented New York cases resolved favorably, compared to 73% of represented cases. This observation broadly holds regardless of the underlying charge.[xxxv]

Based on the experience of the prior five years, approximately 88,000 of the 194,000 unrepresented immigrants may be allowed to stay in the country without further intervention. If the Access for Representation Act were to pass and ensure that all New Yorkers in immigration court had legal representation, based upon outcomes of the past five years an additional 53,000 New Yorkers currently awaiting their court date would be allowed to remain in the country.

The impact of immigrants on the communities they live in is impossible to fully quantify. One generally accepted measure is the net impact of how much immigrants contribute in taxes and other payments less the cost of the services they receive from federal, state and local governments? The Cato Institute produced a model which estimates the impact of immigrants generally as a “net present value” for a period of thirty years differentiated by the person’s present age and educational attainment.[xxxvi] Cato’s model relies on the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey to estimate the education of all immigrants in the U.S. If the demographics of immigrants facing deportation proceedings in New York matched those in Cato’s model, an additional 53,000 people remaining in the U.S. would result in $21.6 billion in net present value revenue to state, local and federal government over 30 years net of benefits paid. Adjusting for the more conservative assumption that New York State residents in deportation proceedings have lower lifetime educational attainment (i.e., increasing the percentage of persons with a high school equivalency or below from 50 percent to 100 percent of estimated impact) federal, state and local government would see a net present value benefit of $8.4 billion over 30 years.

Table 1 Estimated Impact of Universal Representation for Immigrants Currently Awaiting Case Disposition

| Net Impact by Age ($000s) | Census Weighted Average | High School & Below |

| 0 to 4 | -$423.80 | -$464.60 |

| 5 to 11 | $480.22 | $181.19 |

| 12 to 17 | $342.49 | $129.22 |

| 18 to 24 | $4,228.19 | $2,747.23 |

| 25 to 34 | $10,833.10 | $4,339.77 |

| 35 to 44 | $3,664.17 | $878.72 |

| 45 to 59 | $442.16 | -$137.83 |

| 60+ | -$15.87 | -$34.25 |

| Other | $2,011.71 | $805.90 |

| Total | $21,562.36 | $8,445.34 |

Immigration Legal Services for Asylum Seekers

Beyond legal representation for those facing deportation proceedings, additional investments are necessary to recruit and train legal teams, build needed infrastructure, and responsibly expand rapid-response services.[xxxvii] Increased funding for urgent legal needs, including legal screenings, naturalization, know your rights clinics, and referrals would help build an ecosystem to more effectively support immigrant New Yorkers. A key component of building out this infrastructure is immigration legal services. Legal screenings and application assistance can help thousands of New Yorkers stabilize their immigration status, gain work authorization, and reduce the risk they will be put in removal proceedings in the first place.

New York City has welcomed over 180,000 new arrivals who urgently need legal services to navigate our immigration system, get work authorization, and build productive lives. These new New Yorkers have relied on the City’s shelter system as they establish themselves in a new country. While some have received work authorization through Humanitarian Parole, Temporary Protected Status (TPS), or an asylum application that has been pending for six months, a majority still do not have work authorization and cannot work in the formal economy.[xxxviii]

The City and State have made some critical investments in expanding access to immigration legal help for newly arrived asylum seekers, opening Asylum Application Help Center to assist with asylum applications and partnering with the State and Federal governments to speed up filing and processing of work authorization and TPS applications.[xxxix] However, resources remain far below the level of need.

Currently, appointments are only available for those who are nearing the one-year deadline from date of arrival to submit their applications. This means many new arrivals are waiting for many months in City shelters, when earlier legal assistance could make it possible for them to submit their applications, obtain work authorization, and move out of shelter.

Enhanced legal resources – through the City’s Asylum Application Help Center network and through other high-quality immigration legal service providers – would also strengthen the ability of programs to help new arrivals to understand and access all of their immigration options. Many new arrivals have fled religious and race-based persecution, gender-based violence, and political repression and therefore likely have meritorious asylum claims.[xl] While the vast majority of new arrivals to NYC plan on seeking asylum, not all intend on doing so and not all are eligible to apply for asylum.[xli] They may also have other options for immigration relief. For example, many young people in shelter between the ages of 18 to 21 could be eligible for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status.[xlii] Enhanced legal assistance will help the city’s newest arrivals assess their best options and eligibility, and apply for asylum, Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, or TPS in a timely manner. In addition, while applications are pending, access to legal assistance may be necessary to help people monitor their cases and understand their options.

Continued investments in immigration legal services for new arrivals will help grow our local economy as new arrivals get the work authorization they need to begin to enter the labor force and earn more money.

Economic Benefits of Providing Legal Services to Asylum Seekers

Providing immigration legal help to those without status can put immigrants on a pathway to stability and even greater economic potential.

Helping new arrivals win asylum will benefit our economy. A recently released study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that over a 15 year period refugees and asylees[xliii] were a positive net fiscal impact[xliv] on our national economy, contributing $123.8 billion to federal, state, and local governments.[xlv] Research has also shown that when someone has quicker access to a pathway to citizenship (such as through winning asylum), they integrate into the economy quicker and are better off economically in the long term.[xlvi]

Even just gaining work authorization through temporary status, such as Humanitarian Parole or TPS, will also help stabilize new arrivals and boost the local economy. Access to work authorization leads to higher wages. The higher earning power generates more tax revenue.[xlvii] Higher personal income also benefits the economy through increased consumer spending.[xlviii] Additionally, gaining lawful status also opens the door to more immigrants opening bank accounts, buying homes, and starting businesses, which all help grow the economy. Finally, access to work authorization creates more efficiency for the economy as workers are no longer relegated to low wage “under the table” jobs and can find work that better fits their skills, education, and experience.

A new report predicts that for each 1,000 newly arrived immigrant workers the total annual wages paid is $23 million and state and local tax revenues would increase by $2.6 million.[xlix] This number is based on how immigrants with similar characteristics currently make ends meet in New York City, finding that recently arrived immigrants can expect to earn a median wage of about $23,000 per year. Research continues to find a significant “wage penalty” for unauthorized workers ranging from 4 percent to 24 percent of their hourly wage compared with immigrants with work authorization.[l] That means, once an individual gains work authorization, they have much greater earning potential. Gaining work authorization could eliminate this wage penalty for new arrivals, boosting their potential income to up to $28,290. Gaining full time work at minimum wage would bump their annual wages to $33,280.

As of February 18, 2024, the total number of asylum seekers in City shelters is 65,040. Of that total, 51,210 are families with children. If we assume that half of families with children population are adults (25,605 people), there are a total of 39,435 asylum seeking adults currently staying in NYC shelters. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the labor force participation rate of all foreign-born persons in the Mid Atlantic was 64.9 percent in 2022.[li] Applying this labor force participation rate to the adult asylum seekers in shelter population means approximately 16,617 would be expected to work. If all these asylum seekers find work, they will earn collectively over $382 million. With work authorization, this total could rise to over $470 million. With work authorization and full-time minimum wage jobs, that number increases to over $553 million.

The sooner this population is connected with immigration legal help to get work authorization and immigration status, the more their wages and thus state and local tax revenues will increase. Immigrants without work authorization pay a lower effective tax rate than those with work authorization.[lii] With work authorization, new arrivals will continue on a path of upward mobility as their wages will increase over time, as opposed to being relegated to low-wage jobs due to lack of authorization. Access to lawful status also means new arrivals become eligible for federal public benefits. Use of federal public benefits would further help stabilize individuals and their families while also reducing their need to use City-funded benefits that are available regardless of immigration status.

Methodology

Data on New York and the nation’s immigration court backlog, as well as the outcomes of individuals in deportation proceedings, were derived from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), a project of Syracuse University. The backlog reported herein is the current number of pending cases of all charge types in New York State-based immigration courts as of January 2024. Within these filter parameters, the data were cross tabulated for all age groups by whether their associated case was represented by an attorney or unrepresented.

The Comptroller’s Office also derived data on outcomes from TRAC’s databases, filtering again for New York State immigration court cases from Fiscal Year 2019 to present, differentiated by age and legal representation status. A “favorable” outcome is defined as any outcome that allows an immigrant to remain in the United States; removals and voluntary departures are considered unfavorable, while case terminations, granting relief, or other administrative closures by an immigration judge are all favorable outcomes. The observed impacts of the influence of legal representation on immigration cases are strongly positively correlated, but few blinded scientific studies exist, and many factors may contribute to the observed increase in favorable outcomes for represented clients.

The Comptroller’s Office relied on the Cato Institute’s modeling of local, state, and federal government net present value fiscal impacts in their March 2023 paper, “The Fiscal Impact of Immigration in the United States.” The fiscal impact as reported in Appendix Table B6, “30-year net present value flows for all levels of government by age, immigrant status, and budget scenario, including public goods without interest: Cato model” was filtered for each level of educational attainment for the total impact (taxes collected minus benefits paid) of each individual at birth, age 10, 18, 25, 40, 50, and 60, approximately corresponding to the age bands of TRAC’s data. For persons of age Unknown, the NPV associated with age 25 was used. Estimates of educational attainment for 1st generation immigrants were derived from Table 5 within the report.

| Educational Distribution by generation for ages 25 and older for all immigrants (CPS 2016 – 18) | All Immigrants |

| Less than high school | 22% |

| High school | 24% |

| Some college | 13% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 24% |

| More than a bachelor’s degree | 17% |

The Comptroller’s Office combined estimates of net impact and educational attainment to create a reference table, which was mapped to the age ranges for unrepresented immigrants currently awaiting trial in New York to model the potential number of pending cases that would benefit from effective counsel, if the current observation holds under a universal representation scheme.

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Sam Stanton, Senior Policy Researcher, and Robert Callahan, Director of Policy Analytics. Thanks to Vera Institute of Justice, Acacia Center for Justice, and the New York Immigration Coalition for advice and assistance in putting together this report.

Endnotes

[i] A Historic Step in Access to Justice for Immigrants Facing Deportation, Vera Institute of Justice (Aug 15, 2013), https://www.vera.org/news/a-historic-step-in-access-to-justice-for-immigrants-facing-deportation.

[ii] 2022 Annual Report, New York City Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (Sept. 2023), https://www.nyc.gov/assets/immigrants/downloads/pdf/MOIA_WeLoveImmigrantNYC_AR_2023_final.pdf.

[iii] Accounting for Asylum Seeker Services – Asylum Seeker Census, New York City Comptroller, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/services/for-the-public/accounting-for-asylum-seeker-services/asylum-seeker-census/.

[iv] Access to Representation Act, S999, 2023-2024 N.Y. Leg. Sess., available at: https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2023/S999/amendment/A.

[v] Too Few Immigration Attorneys: Average Representation Rates Fall from 65% To 30%, TRAC (Jan. 24, 2024), https://trac.syr.edu/reports/736/.

[vi] Accounting for Asylum Seeker Services – Asylum Seeker Census, New York City Comptroller, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/services/for-the-public/accounting-for-asylum-seeker-services/asylum-seeker-census/.

[vii] 8 §1158(d)(2).

[viii]Explainer: Asylum Backlogs, National Immigration Forum (Jan. 23, 2024), https://immigrationforum.org/article/explainer-asylum-backlogs/#:~:text=With%20so%20many%20asylum%20seekers,time%20of%20approximately%204.3%20years.

[ix] Removal refers to the expulsion of a person from the U.S. who is not a U.S. citizen. The more commonly used term is “deportation.” However, “removal” is the term used under federal immigration law. 8 USC §1229a(e)(2). This report uses the terms interchangeably.

[x] 8 U.S.C. §1227.

[xi] 8 U.S.C. §1229a.

[xii] Melissa Crus, ICE May Have Deported as Many as 70 US Citizens In the Last Five Years, Immigration Impact (Jul. 30, 2021), https://immigrationimpact.com/2021/07/30/ice-deport-us-citizens/.

[xiii] Access to Representation Act, S999, 2023-2024 N.Y. Leg. Sess., available at: https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2023/S999/amendment/A.

[xiv] Ingrid V. Eagly & Steven Shafer, A National Study of Access to Counsel in Immigration Court, 164 U. of Penn. L. Rev. (2015), https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=9502&context=penn_law_review; see also Jennifer Stave, Peter Markowitz, Karen Berberich, Tammy Cho, Danny Dubbaneh, Laura Simich, Nina Siulc, & Noelle Smart, Evaluation of the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project, Vera Institute of Justice (Nov. 2017), https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/new-york-immigrant-family-unity-project-evaluation.pdf.

[xv] Christina Gathmann & Nicolas Keller, Access to Citizenship and the Economic Assimilation of Immigrants, 128 Econ. J. 3141 (2017), available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ecoj.12546.

[xvi] The State of Black Immigrants, Black Alliance for Just Immigration (Mar. 2020), https://baji.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/sobi-fullreport-jan22.pdf.

[xvii] Id.

[xviii] CERD: Anti-Black Discrimination within U.S. Immigration, Detention, and Enforcement Systems, Human Rights First (Aug. 8, 2022), https://humanrightsfirst.org/library/cerd-anti-black-discrimination-within-us-immigration-detention-and-enforcement-systems/.

[xix] Public Support in New York State for Government-Funded Attorneys in Immigration Court, Vera Institute of Justice (Mar. 2020), https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/taking-the-pulse-new-york-key-findings.pdf.

[xx] Statement on the Effects of Deportation and Forced Separation on Immigrants, their Families, and Communities, 62 Am. J. Community Psychol. 3 (2018), available at https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12256.

[xxi] Maricruz Castro Ricalde & María José Gutiérrez, Deported Mothers: Mental Health and Family Separation, UC David Global Migration Center (2020), https://globalmigration.ucdavis.edu/sites/g/files/dgvnsk8181/files/inline-files/Migrant_Narrative-DeportedMothers.pdf.

[xxii] U.S. Citizen Children Impacted by Immigration Enforcement, American Immigration Council (June 2021), https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/us-citizen-children-impacted-immigration-enforcement.

[xxiii] Miguel Pinedo & Carmen R. Valdez, Immigration Enforcement Policies and the Mental Health of US-Citizens: Findings from a Comparative Analysis, 66 Am J Community Psychol. 119 (2020), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7944641/.

[xxiv] Samantha Artiga & Barbara Lyons, Family Consequences of Detention/Deportation: Effects on Finances, Health, and Well-Being, KFF (Sep. 2018), https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/family-consequences-of-detention-deportation-effects-on-finances-health-and-well-being/.

[xxv] The New York Family Unity Project: Good for Families, Good for Employers, and Good for all New Yorkers, Center for Popular Democracy (2014), https://www.populardemocracy.org/sites/default/files/immgrant_family_unity_project_print_layout.pdf.

[xxvi] Facts, Not Fear: How Welcoming Immigrants Benefits New York City, New York City Comptroller (Jan. 2024), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/facts-not-fear-how-welcoming-immigrants-benefits-new-york-city/.

[xxvii] Id.

[xxviii] Id.; see also Ben Gitis & Laura Collins, The Budgetary and Economic Costs of Addressing Unauthorized Immigration: Alternative Strategies, American Action Forum (Mar. 2015), https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/the-budgetary-and-economic-costs-of-addressing-unauthorized-immigration-alt/#ixzz8SQ1FzHoK (finding mass deportations would dramatically shrink the nation’s labor force).

[xxix] Ben Gitis & Laura Collins, The Budgetary and Economic Costs of Addressing Unauthorized Immigration: Alternative Strategies, American Action Forum (Mar. 2015), https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/the-budgetary-and-economic-costs-of-addressing-unauthorized-immigration-alt/#ixzz8SQ1FzHoK.

[xxx] Ryan Edwards & Francesc Ortega, The Economic Impacts of Removing Unauthorized Immigrant Workers, Center for American Progress (Sep. 2016), https://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/10/massdeport1003.pdf.

[xxxi] Id.

[xxxii] U.S. Department of Homeland Security records provided to TRAC indicate whether the person in removal proceedings has had an attorney or accredited representative file a G-28 form. See https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/backlog/about_data.html.

[xxxiii] Immigration Court Backlog, TRAC, https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/backlog/ (last accessed Mar. 8, 2024).

[xxxiv] While our report reviews success patterns for represented versus unrepresented New Yorkers in removal proceedings based upon TRAC data, other studies and evaluations have also confirmed that access to representation is highly correlated with successful outcomes. See, e.g., Ingrid V. Eagly & Steven Shafer, A National Study of Access to Counsel in Immigration Court, 164 U. of Penn. L. Rev. (2015), https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=9502&context=penn_law_review; Jennifer Stave, Peter Markowitz, Karen Berberich, Tammy Cho, Danny Dubbaneh, Laura Simich, Nina Siulc, & Noelle Smart, Evaluation of the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project, Vera Institute of Justice (Nov. 2017), https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/new-york-immigrant-family-unity-project-evaluation.pdf.

[xxxv] Outcomes of Immigration Court Proceedings, TRAC, https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/closure/ (last accessed Mar. 8, 2024).

[xxxvi] Alex Nowrasteh, Sarah Eckhardt, & Michael Howard, The Fiscal Impact of Immigration in the United States, Cato Institute (Mar. 2023), https://www.cato.org/white-paper/fiscal-impact-immigration-united-states.

[xxxvii] See Invest $150M in immigration legal services in FY25 and pass the Access to Representation Act (S999/A170) to guarantee a right to counsel for immigrants facing deportation, CARE for Immigrant Families (2024), https://vera-advocacy-and-partnerships.s3.amazonaws.com/CARE_Pass%20the%20ARA%20One%20Pager%20FY25.pdf.

[xxxviii] Humanitarian Parole, USCIS, https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/humanitarian_parole (last accessed March 17, 2024); Temporary Protected Status, USCIS, https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/temporary-protected-status (last accessed March 17, 2024); Asylum, USCIS, https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/refugees-and-asylum/asylum (last accessed March 17, 2024).

[xxxix] Elizabeth Kim, Federal Officials Expand Efforts to Expedite Migrant Work Permits in NYC with New Intake Center, Gothamist (Dec. 1, 2023), https://gothamist.com/news/federal-officials-expand-efforts-to-expedite-migrant-work-permits-in-nyc-with-new-intake-center.

[xl] See, e.g., Jay Bulger & Paula Aceves, In Line at St. Brigid The City’s Campaign to Push Migrants out has Turned Their Lives into an Interminable Loop, Curbed (Feb. 26, 2024), https://www.curbed.com/article/nyc-migrants-shelter-stories-st-brigid-church-reticketing.html.

[xli] Displaced and Disconnected: The Experience of Asylum Seekers and Migrants in New York City in 2023, Make the Road New York (2023), https://maketheroadny.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Displaced-and-Disconnected_MRNY-Report.pdf.

[xlii] Special Immigrant Juveniles, USCIS, https://www.uscis.gov/working-in-US/eb4/SIJ (last accessed Mar. 8, 2024).

[xliii] Refugees and asylees are persons who have been granted residence in the United States in order to avoid persecution in their country of origin.

[xliv] Positive net fiscal impact means that they contributed more to government, such as through taxes, than the government spent on them, such as through public benefits.

[xlv] Robin Ghertner, Suzanne Macartney & Meredith Dost, The Fiscal Impact of Refugees and Asylees Over 15 Years: Over $123 Billion in Net Benefit from 2005 to 2019, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (Feb. 15, 2024), https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/3dd52e6be9abfa2b7462be0fb3a9c81f/aspe-brief-refugee-fiscal-impact-study.pdf.

[xlvi] Christina Gathmann & Nicolas Keller, Access to Citizenship and the Economic Assimilation of Immigrants, 128 Econ. J. 3141 (2017), available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ecoj.12546.

[xlvii] An Immigration Stimulus: The Economic Benefits of a Legalization Program, American Immigration Council (April 3, 2013), https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/immigration-stimulus-economic-benefits-legalization-program.

[xlviii] Id.

[xlix] New Immigrants Arriving in the New York City: Economic Projections, Immigration Research Initiative (Jan. 8, 2024), https://immresearch.org/publications/new-immigrants-arriving-in-the-new-york-city-economic-projections/.

[l] Chair Cecilia Rouse, Lisa Barrow, Kevin Rinz, & Evan Soltas, The Economic Benefits of Extending Permanent Legal Status to Unauthorized Immigrants, The White House Council of Economic Advisors (Sep. 17, 2021), https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2021/09/17/the-economic-benefits-of-extending-permanent-legal-status-to-unauthorized-immigrants/; George J. Borjas, The Earnings of Undocumented Immigrants, National Bureau of Economic Research (Mar. 2017), available at: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23236/w23236.pdf; George J. Borjas & Hugh Cassidy, The Wage Penalty to Undocumented Immigration, 61 Labour Economics (Dec. 2019), available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0927537119300831.

[li] Foreign-born Workers: Labor Force Characteristics — 2022, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (May 18, 2023) https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/forbrn.pdf .

[lii] Undocumented Immigrants’ State & Local Tax Contributions, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (Mar. 1, 2017), https://itep.org/undocumented-immigrants-state-local-tax-contributions-2017/#:~:text=Undocumented%20immigrants%20nationwide%20pay%20on,rate%20of%20just%205.4%20percent.