Fiscal Resiliency: Reforming New York City’s Emergency Procurement System before the Next Storm

Executive Summary

Five years ago, amid blackouts and floods, New York City mobilized to secure necessary goods and services in the wake of Superstorm Sandy, the worst storm to hit the Atlantic region in 75 years. The devastation wrought by Sandy in October 2012 was enormous, and its costs extended far beyond the $19 billion in damages estimated by the City. Forty-three New Yorkers lost their lives to the storm and thousands more were injured, displaced and financially devastated by the storm’s destruction. The total economic hit to the region was estimated at $71.5 billion by the National Hurricane Center.

In the face of this disaster, New York City government responded quickly and purposefully. In the initial days after the storm, the City dispensed approximately two million meals, 700,000 bottles of water, 3,000 flashlights, and more than 170,000 blankets. City agencies also provided services ranging from debris removal and home repair, to emergency shelter and transportation, some of which continued for months and years after the storm.[1]

Many of the goods and services bought after the storm were authorized through “emergency procurement” – a purchasing method that dispenses with the City’s normal safeguards and allows goods and services to be purchased more swiftly. Ultimately, mayoral agencies sought authorization from the Comptroller’s Office to make up to $1.3 billion in emergency purchases.

While acting quickly is essential following a crisis, purchasing under emergency conditions can result in myriad problems, including paying higher prices, creating purchasing redundancies, and entering into contracts with insufficient protections against waste and abuse. These conditions could ultimately leave the City vulnerable to issues of poor vendor performance, confusion over contract terms, or even potential fraud. In certain situations documented in this report, the City was forced to pay above-market rates for potentially sub-quality goods and services from a limited pool of vendors.

This report by Comptroller Scott M. Stringer offers a seven-point plan designed to help New York anticipate many of the challenges posed by emergency procurements and develop innovative ways to meet the needs of New Yorkers more quickly and efficiently.

The Comptroller’s plan proposes that the City:

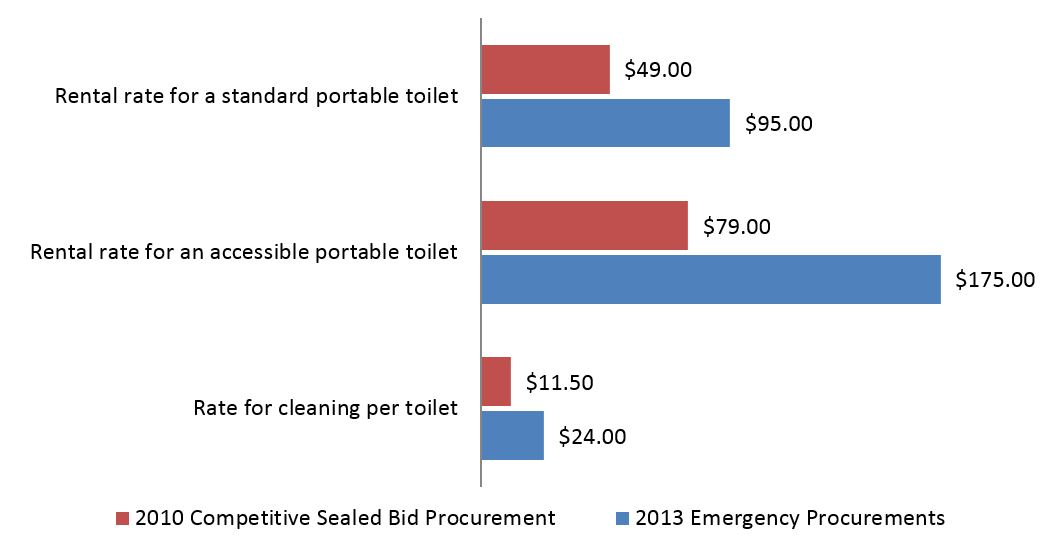

- Develop and publish a citywide emergency procurement plan that better addresses contract needs in advance of the next disaster in order to coordinate a more unified emergency response. Emergency procurements like those outlined above can drastically raise the prices of common goods and services compared to normal procurements. For example in the months after Sandy, the rental price for a standard toilet nearly doubled from $49 to $95, and the rate for an accessible toilet increased over 120 percent. Likewise, cleaning services for each toilet more than doubled after Sandy, adding $24 to the cost compared to the $11.50 standard rate paid for similar services pre-Sandy. Similarly, while not Sandy related, the City ended up paying an average of 285 percent more for additional road salt that it purchased through an emergency contract in the winter of 2013-2014, after heavy winter storms depleted the City’s reserves. By creating and maintaining a coordinated list of contracts for use across all agencies in the event of an emergency, the City can better assess the capacity of existing contracts to meet emergency needs, potentially reducing reliance on emergency purchasing. This roster of contracts should extend beyond basic items such as water and blankets to more difficult procurements like social services, telecommunication, construction, transportation, temporary office space, and housing. The City should also use its plan to assess its current inventory of emergency supplies and should create a tracking system which allows all agencies to assess real-time information pertaining to the City’s emergency supplies.

- Create a more robust catalogue of requirement or ‘on call’ contracts specifically for the procurement of emergency goods and services. ‘On call’ contracts allow the City to pre-negotiate rates for specific goods and services that could be needed in an emergency, fostering a more cost-effective and reliable pipeline of help in advance of any disaster. These contracts help ensure consistent prices for goods and services, and can help guard against the unnecessary use of emergency contracts, which lack many of the oversight measures standard in typical procurements. In sum, City requested authorization from the Comptroller’s office for $1.3 billion in emergency procurement authority to address Sandy needs, essentially asking for the permission to purchase goods and services up to that level.

- Include “Emergency Contract Riders” in new contracts allowing the City to access goods or services that may be useful in emergency situations from existing vendors. Such language could include specific instructions concerning how normal service provisions – from tree removal and storm drain maintenance, to food services and shelter – can adapt to an emergency or potentially lay ground rules for the negotiation of emergency pricing. These riders could allow the City to access contracts through existing vendors, who have been appropriately vetted by City agencies.

- Learn from complications arising from the City’s Rapid Repairs program and develop an improved model for a home repair program that can be launched when disaster strikes. In the event of a future emergency, the City should be prepared to develop a program able to restore single family and multifamily homes to minimally habitable conditions. The City should be drawing on agency expertise in building codes, job order contracts, small scale repair and rehabilitation to formulate a program that can be immediately implemented after a disaster. Planning should also incorporate the contractor community to help increase awareness of the City’s expectations and terms for this type of work. The City should create model contracts which can be bid out in the immediate aftermath of a storm or disaster to avoid some of the confusion around billing that came to define the City’s Rapid Repairs program in the months and years after the storm. By memorializing contract terms, scope of work, program requirements, and oversight authority ahead of an emergency, the City can guard against poor-quality work, delayed payments to vendors, and disagreements over billing.

- Cooperate more efficiently on the state, regional and national levels to pool contracts and create resources. Having master contracts in place with other jurisdictions in the event of an emergency would exponentially expand the universe of goods and services New York City would have access to in an emergency and harness the collective buying power of government.

- Increase oversight and transparency by requiring periodic emergency contract updates, establishing emergency oversight procedures, instituting new training curriculums and striving for early registration of contract. While emergency contracts should be the last resort of agencies, several steps can be taken to guard against waste or mismanagement. When agencies quickly enter into emergency contracts, they can unintentionally fail to implement crucial accountability measures, such as was the case with a series of Department of Homeless Service contracts which lacked oversight and necessitated claw-backs of city spending.

- Establish protocols to expand the use of P-Cards – or City-issued credit cards – in the event of an emergency to facilitate the immediate payment of vendors for services rendered. P-Cards allow for on-the-spot procurement decisions to be made by first responders and recovery officials, while also providing an electronic, real-time record of purchases for later tracking. By strengthening its system of financial controls, the use of P-Cards can be expanded without the prospect of fraud or waste.

The recent hurricanes that devastated Puerto Rico, Houston, Florida, Barbuda, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Anguilla and Dominica, as well as the mass shooting in Las Vegas, the magnitude 8.1 earthquake in Mexico and the on-going wildfires in northern California underscore the need to immediately prepare and plan for the next disaster. For New York City, five years on, the experience of Superstorm Sandy provides an opportunity to look back and learn. This report draws on the lessons of Sandy to help create a more efficient and cost effective emergency procurement system.

Emergency Procurement: Background and Context

Superstorm Sandy brought unparalleled devastation to the five boroughs. A storm surge of over 14 feet swept into lower Manhattan, 10-foot high waves pummeled the Rockaways, and winds of 80 miles per hour buffeted Staten Island. The flood waters covered 51 square miles of the City, an area home to more than 443,000 New Yorkers and 23,400 businesses.[2]

Before the storm even arrived, the City’s procurement apparatus was already in motion. On October 27, 2012, two days before Sandy hit, the City recognized the severity of the oncoming storm and began to make limited arrangements for buying goods and services through emergency procedures.

Normally, in the absence of some imminent threat, City agencies purchase goods and services through competitive processes that, while not always swift, are intended to assure the best price for taxpayers and guard against fraud and abuse. The City has a variety of procurement methods at its disposal, with the most common being competitive sealed bids (“CSBs”).[3] During a typical procurement, oversight approvals may be required from the Law Department, the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services (MOCS), the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Department of Investigation (DOI) depending on the award method and dollar amount. Once the procurement has received all necessary approvals, a solicitation will be released for vendors to respond to, and a vendor will be selected.[4] After additional approvals have been obtained and the agreement has been executed, the agency then submits the contract package to the Comptroller’s Office for registration. This process can take many months, but is designed to ensure fairness and competition in City procurement while reducing the likelihood of corruption or fraud. During Fiscal Year 2017, New York City procured $21 billion in goods and services through more than 39,500 separate transactions.[5]

When faced with severe emergencies, such as Superstorm Sandy, Hurricane Irene, or the events of September 11th, the City does not have time to go through a multi-month procurement process. Goods and services are required immediately to meet unanticipated needs. In these cases, City procurements can be made through an emergency system designed to expedite the delivery of necessary goods and services in the face of threats to public health or safety, or the interruption of essential city services.

The process and basis for use of the emergency procurement award method is codified in Section 3-06 of the Procurement Policy Board Rules (“Emergency Purchases”).[6] Once an agency determines that an emergency condition exists, it must request prior approval from both the Comptroller and the Corporation Counsel to utilize the “Emergency Purchases” award method.[7] Since the response to an emergency must occur quickly to prevent some form of harm, agencies are instructed to apply the “level of competition that is possible and practicable under the circumstances” in the contractor selection process.[8] The Comptroller’s review of this determination also considers the following factors: whether the scope of the emergency procurement is limited to items necessary to avoid or mitigate serious danger to life, safety, property, or a necessary service; and whether the procedure identified by the agency to select the contractor assures that the required items will be procured in time to meet the emergency.[9]

The Emergency Purchases method permits agencies to contract with providers on an expedited basis using a level of competition commensurate with the emergency condition. It also permits contractors to begin work prior to registration of the applicable contracts. This model differs from the standard City procurement model, which requires contract registration prior to implementation.

However, enabling a contractor to begin work quickly does not mean that the registration process is waived altogether. Once all procedural requisites are satisfied, the agency must still prepare and submit a contract package to the Comptroller’s Office for registration. Superstorm Sandy resulted in 167 approved emergency purchase requests.

Building “Fiscal Resiliency” Through Procurement Reform

This report offers a seven-point reform plan designed to improve emergency procurement and ensure the City is better prepared for the next disaster it faces.

I. Emergency Procurement Planning

While no one can foresee or plan for every eventuality, it should be the City’s stated goal to avoid the use of emergency procurements unless absolutely necessary. As explained above, emergency procurements often forego or postpone many of the vendor integrity or competitive pricing requirements that characterize the City’s normal contracting process.

As a result, emergency procurements can often cost more but buy the taxpayer less. While procurement officers make tremendous efforts to secure vital supplies at the best possible price, the nature of developing contracts in the middle of an emergency situation and without the ability to solicit a wide array of competitive bids can leave the City paying an “emergency premium” for goods and services without any added value.

These costs can be avoided, or at least mitigated, by foresight and diligent planning for emergency contingencies. Often, adding additional capacity to normal, competitive procurements can help avoid emergency contracts, save money, increase the probability of the delivery of services, and enhance planning. In the aftermath of Sandy, the City ended up paying considerably more under an emergency procurement for portable toilets than it did in a comparable non-emergency, competitive sealed bid procurement. The City, having exhausted its supply of portable toilets from an existing Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) contract that was procured through a competitive sealed bid in 2010, was forced to enter into a new $196,000 emergency procurement for portable toilets.

According to the terms of the contract, the City paid rental rates for standard and accessible toilets that far exceeded the established rates under the existing DCAS contract. The rental price for a standard toilet nearly doubled from $49 to $95, and the rate for an accessible toilet increased over 120 percent. Cleaning services for each toilet added $24 to the cost compared to the $11.50 standard rate paid for similar services pre-Sandy.

Chart 1: The Emergency Premium on Portable Toilets

While not related to Sandy, the City’s procurement for road salt provides another example about how advanced planning can help reduce the need for extemporized emergency purchases.

Before the 2013-2014 winter, DCAS entered into an on-call contract for the supply and delivery of salt with two vendors for a maximum of 300,000 tons. However, heavy winter storms meant the City was forced to procure more salt supplies quickly. Once it hit the limit of salt it could buy through of its existing contract, the City had to use an emergency procurement to purchase additional salt and salt delivery. As a result, the City ended up paying an average of 285 percent more for additional salt.

By the next winter, DCAS had proactively changed their procurement plans to avoid the need for future emergency contracts and the higher costs associated with ad hoc emergency contracting. The City negotiated into its contract a higher purchase ceiling of 400,000 tons of salt to better prepare for the possibility of an unanticipated need for more road salt.[10] With the aim of anticipating emergency needs, the City should devise a comprehensive and coordinated emergency procurement plan drawing on the combined expertise of agency procurement officers, the Office of Emergency Management (OEM), the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services (MOCS) and the Comptroller’s Office. These three agencies should facilitate changes to the City’s emergency procurement rules and procedures that balance the needs of specific agencies with a general framework of best practices. In order to facilitate the City’s ability to efficiently and effectively act in preparation for, or response to, an emergency, standard operating procedures (SOPs) should be developed that clearly details the operational structure to be employed in the event of an emergency. Steps the City should consider include:

- Conduct and maintain a comprehensive citywide inventory of goods and services available during an emergency, while leveraging pre-established protocols for monitoring and management of food, water and other consumables;

- Identify “Lead Emergency Procurement Coordinators” with subject matter expertise for each agency. Allow coordinators to work across agencies to purchase together around categories of potential need in an emergency. Target areas for coordination include construction and repair, general goods and services, fuel, travel and lodging, transportation, search and rescue, health and safety, oversight and monitoring, and food supply;

- Leverage the City’s automated procurement tracking system or similar tool to create an online purchasing resource similar to the federal General Services Administration (GSA) model, which allows buyers to access contract award information, send solicitations to available contractors, and order and pay online; and

- Establish standardized accounting and auditing procedures to track spending and other important information for reimbursement purposes which can be deployed “online” and “offline” in the event that electricity and/or technology is unavailable.

II. On-call Contracts

Before New York faces another storm or disaster, the City should expand its use of “on-call” contracts to cover a broader range of goods and services that will likely be necessary before, during, and after an emergency situation. On-call contracts are agreements with vendors that can be arranged ahead of an emergency event, based on the anticipated needs the City will have when facing catastrophes.

While New York City currently utilizes on-call contracts for many goods and services, expanding their use for the types of goods and services that were in demand after Sandy and the types of goods and services that could be needed after other types of man-made or natural disasters, would better prepare the City for the next emergency. By establishing contract terms with a vendor in advance of a potential disaster, the City can take the time to craft carefully vetted contracts that encourage the best available pricing for the goods and services it will need during a crisis and ensure the proper vetting for vendor integrity is conducted. Establishing contracts in advance allows for the use of competitive bids and other procurement methods designed to achieve the best possible deal for New York’s citizens. With targeted contracts procured and established in advance, City agencies can better focus on providing relief rather than deliberating on contract terms or searching for available vendors.

On-call contracts can help ensure a baseline level of pricing predictability and help control costs. By agreeing on contract terms and potentially pricing, the City can avoid entering into emergency contracts which can often fluctuate. For instance, in the months after Sandy, the City requested authorization from the Comptroller’s office for $880 million in emergency procurement authority, essentially asking for the permission to purchase goods and services up to that level. In reviewing those same Sandy emergency procurement approvals five years later, an analysis by the Comptroller’s Office shows the City ultimately sought $1.3 billion in spending authority – amounting to a 47 percent increase across all agencies. These spending increases are attributable to changes in pricing and changes in contract terms, which could be mitigated by the use of on-call contracts that spell out pricing or terms well in advance of a disaster.

A potential model for New York is the State of Louisiana’s emergency procurement system, which has relied on contingency contracts to supply everything from ambulances and storage containers to emergency food deliveries. Louisiana, a state with a long history of responding to hurricanes and other natural disasters, designed its emergency contracts to allow for maximum speed and efficiency. Louisiana maintains an electronic catalog of their emergency contracts, with information on a contractor’s ability to adapt to certain emergency conditions or disruptions to their supply chain. Delivery time for goods and services ranges from 8 to 24 hours, and contracts are flexible enough to meet the often varied needs of emergency coordinators and first responders. Generally, these contracts are negotiated without costly retainers and have the potential to realize savings by preventing overlapping purchases between agencies.

A series of on-call contracts, negotiated in advance, would also provide agencies and vendors with the clear legal frameworks that translate into efficient and purposeful programs. Agencies could anticipate future needs and sign on-call contracts with a variety of vendors whose participation would be essential to recovery efforts.

The City has already made strides in this area. For example, the Human Resources Administration (HRA) entered into contracts for emergency, on-call case management services. In addition, the Comptroller’s Office has recently registered a number of DDC on-call emergency contracts for disaster preparedness planning. Making additional on-call contracts in advance of an emergency would ensure goods and services are available when New Yorkers need them, at the best prices the City can negotiate.

III. Strategic Contract Language

Every year, New York City enters into thousands of contracts ranging from office supplies to ambulance services. With the inclusion of specific language in the standard text of a contract via a provision or as an “emergency rider,” the City can take better advantage of the massive breadth of its contract roster should an emergency arise.

Many other municipalities and states make the insertion of emergency-specific language into contracts a standard practice. One such example is the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, which incorporates the following rider into most of their standard contracts: “In the event of a serious emergency, pandemic or disaster outside the control of the Department, the Department may negotiate emergency performance from the Contractor to address the immediate needs of the Commonwealth even if not contemplated under the original Contract or procurement. Payments are subject to appropriation and other payment terms.”[11]

New York City should include similar language in its standard contracts to allow the City to draw on any particular contract’s terms and conditions during an emergency. In addition to the rider, the City could explore a standard terms and conditions contract template as an appendix which could be instituted in the event the emergency provisions need to be tapped into. Businesses would be able to operate under the familiar legal arrangements that characterize their current legal relationship with the City, and the City would be spared the time and expense of drawing up new contracts. Being able to utilize an existing contract during an emergency also means that the City and the vendor can rely on already stipulated payment schedules and procedures, allowing for vendors to be more quickly compensated for their work – a reform which could speed the pace of any future recovery.

IV. Building an Improved Rapid Repairs Program

While successful on many levels, there are lessons to be learned from the Rapid Repairs program implemented by New York City in the weeks after Superstorm Sandy. It behooves the City to draw on its experiences during Superstorm Sandy to reevaluate, refine and codify many of its emergency procurement procedures.

Superstorm Sandy inflicted enormous damage to New York’s building stock, knocking houses off their foundations, inundating boiler rooms with corrosive seawater, and stripping homes of their roofs, walls and siding. Many New Yorkers returned home to find their houses in a state of disrepair, if not outright devastation. Responding to an immediate need for rebuilding, the City launched Rapid Repairs, an innovative program with the goal of making expedited repairs to restore structural integrity, heat, plumbing and electricity to homes in order to make them minimally habitable. Within 100 days, the program had repaired approximately 11,740 buildings, which together were home to over 54,000 New Yorkers. Rapid Repairs allowed City residents to begin rebuilding while living in their own homes and buildings, rather than in a FEMA trailer or emergency shelter.

Rapid Repairs was remarkable for its speed, scope and scale. The program was announced just two weeks after Sandy made landfall, work began one week after that, and the program concluded only four months after the storm. At the height of the program, a 2,300 person workforce completed repairs on more than 200 homes per day at an average price tag of $25,000 per home, totaling $629 million in federal dollars.[12] The design of the program meant that money allocated for temporary shelters could be used for permanent repairs, an approach that ultimately protected many New Yorkers from an unusually bitter winter.

However, the very speed and innovation which made Rapid Repairs a success may have contributed to subsequent quarrels between the City and its contractors. In its initial weeks, the program operated without formal, signed contracts, instead relying on quickly drafted term sheets that based payment off extemporized terms and pricing plans. Contractors, operating without the protections afforded by a contract, were left without a clear legal framework that plainly spelled out what constituted eligible work and appropriate pricing.

Beyond issues of payment and program organization, the City also struggled to maintain standards of scrupulous payroll accounting, potentially jeopardizing FEMA reimbursements. These arrangements left both the City and the contracting community at risk. Rapid Repairs contracts included quality assurance oversight by the City and integrity monitoring by the Department of Investigation (DOI), aimed at ensuring the City was paying a fair price for work done. However, an audit of billing and expenditures conducted by DOI unearthed a series of billing discrepancies related to electrical work and debris removal. In one case, DOI identified $19,800 in fraudulent spending in a single home where contractors billed for 1,500 linear feet of electrical wire, despite installing only 400 linear feet.[13] In response to the investigation, the City extracted penalties from a number of contractors. Several of these contractors filed claims against the City, either seeking relief from DOI penalties or requesting payment for work rendered.

The City should draw on its experience with Rapid Repairs to create a nucleus of an improved program in advance of the next storm. The City could begin by assigning responsibility for a similar program to an agency with significant residential construction experience. The Office of Housing and Recovery, the Department of Design and Construction, Housing Preservation and Development, or the Economic Development Corporation could all play a role in designing, implementing, and overseeing the next iteration of a Rapid Repairs type program.

The City should also work to outline program parameters before a storm or disaster strikes. While every disaster is distinct in its ramifications, the City should take steps now to assemble lists of pre-qualified contractors, create model contracts, develop standard designs for emergency repairs, develop toolkits and training regimes for contractors, and plan constituent outreach efforts to inform residents of the program’s purpose and scope.

Crucially, the City must also develop a better process to help individual contractors and quality insurance monitors assess homes, agree on a scope of work, verify completion of construction, standardize payment documentation, and submit invoices commensurate with work completed. The City should formalize DOI recommendations on quality control, specifically on electrical work, which DOI cited as an area of particular concern.

V. Leveraging the Buying Power of the City through Arrangements with State, Regional and National Agencies or Groups

A crisis can create a sense of community, or strengthen existing community ties. In times of need, New Yorkers have been able to rely on their neighbors, both locally and regionally. From the electrician rushing in from Ohio to help with needed repairs, to the assistance of national charities like Habitat for Humanity, New York City is able to depend on the help of the nation when disaster strikes.

That same dynamic of cooperation can apply to procurement. The City should formalize arrangements with state, regional and federal agencies, in addition to national cooperative purchasing organizations to develop leveraged procurement agreements and expand purchasing options after a disaster strikes. The State’s new Shared Services Initiative, which allows municipalities across New York State to share resources and tools, could be a potential model for cross-jurisdiction procurement coordination.[14]

An initial step would be to form an “Upstate/Downstate Emergency Planning Committee” with the goal of coordinating procurement strategies between the City and other New York municipalities. With the State’s Office of General Services serving as a leader, cities and towns across the state could pool their resources in the event of a disaster and utilize a wide array of separately negotiated contracts to secure a broader range of goods at more competitive prices.

Cooperation should also extend beyond New York State’s borders. New York, Connecticut and New Jersey are bound not just by their physical proximity but by a shared economy. In recognition of these links, municipalities in the tri-state area should seek to form a ‘Trans-Hudson’ cooperative agreement for regional procurement. This affiliation would allow cities and towns in the region to draw on each other’s resources when disaster strikes.

Beyond the immediate tri-state area, there are many other established, national cooperative purchasing groups that New York City could join, such as the National Joint Powers Alliance, and the U.S. Communities Government Purchase Alliance. Access to these groups and their immense purchasing power would better equip New York City to confront any eventuality it might face in the coming years. The City must also take care to continue and expand its longstanding relationships with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the U.S. Department of Labor. The City should be proactive in collaborating and planning with these federal agencies before emergency strikes, so that the public can be guaranteed a rehearsed and organized response when the time comes.

VI. Oversight and Transparency

While the City should seek to reduce its reliance on emergency contracts by planning for contingencies and implementing the reforms outlined above, emergency contracts are still necessary and unavoidable in times of unexpected need. However, the City can explore reforms and transparency measures to better monitor emergency spending and ensure that New Yorkers get the best value for their tax dollars.

Contracts entered into by the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) provide an illustration of some of the dangers of relying on emergency contracts months after an emergency. According to a 2014 audit released by the Comptroller’s office, DHS initiated 20 emergency contracts totaling $19.9 million to provide housing services, medical services, and administrative support to victims of Sandy.[15]

The 2014 audit found that vendors associated with the contracts were being improperly paid for services outside of the scope of the contract.[16] For instance, one vendor received $28,000 for services completed a month after the contract’s end date. Another vendor submitted an invoice for $176,680 for ineligible employee expenses like vacation pay, a fact only discovered after a DHS review of spending. The audit concluded that five of the six DHS officials charged with tracking contracts failed to provide any documentation proving their oversight.

One of the best tools to counter the unexpected and to create established procedures for oversight is the establishment of clear procedures and protocols for contract management, and training on them. Investing in the development of emergency procedures and protocols and training can help equip agencies with the necessary experience to manage complex procurements when disaster strikes. Having all of the agency stakeholders such as the general counsel, the budget director, senior staff and procurement staff at individual agencies thoroughly briefed on legal requirements and the mechanics of creating emergency procurements can go a long way to standardizing practices and executing a rapid and effective response. It can also help acquaint agency personnel with requirements for standardized accounting and auditing procedures to track spending and other important information for reimbursement purposes.

Emergency procurement methods also create oversight and transparency challenges involving reviews for fraud and corruption. As established in the City Charter, the Comptroller is responsible for the registration of all contracts for goods, services or construction that are paid out of the City treasury or paid out of money under the control of the City. It can often take months for emergency contracts to reach the Comptroller’s office for registration. In the meantime, the contracted work has often been completed.

Far from a formality, the process of promptly registering a contract guards against fraud and abuse while demanding uniform best practices across City procurement. During registration, the Comptroller’s office reviews every contract to determine if there is adequate money in the City’s budget to pay for the goods or services and that both the contracted vendors and process are free of corruption.

Typically, registrations for emergency contracts lag long behind their inception. In one instance, an almost $5 million contract was registered a full seven months after the contract start-date. Circumstances like this could increase the likelihood and potential for fraud, abuse or mismanagement by City agency personnel.

City agencies should aim to submit emergency contracts for registration and review as soon as is possible during an emergency. When it is not possible to submit full documentation before a contract is executed on an emergency basis, agencies should relay short summaries of contracts, including term-sheets, to the Comptroller to help ensure more accountability and a measure of transparency to an often opaque procurement process.

VII. Expansion of P-Cards

Procurement Cards, or P-Cards, are credit cards intended for small dollar procurements. Designed to be an efficient and expeditious alternative to the normal procurement processes, P-Cards are plastic swipe cards that allow City employees to make on the spot purchases of specific items. P-Cards were of enormous utility after Sandy, with $56 million in Sandy related purchases recorded in Fiscal Year 2013.[17] The anticipated need for speedy and flexible spending options was so acute that the standard P-Card limit was raised from $5,000 to $20,000 before the storm made landfall in New York.[18] P-Cards are favored by merchants and City officials alike, as they enable immediate payments to vendors at a very low overhead.

Protocols surrounding P-Cards could be reformulated to allow for potential savings and purchasing efficiencies. In the current emergency procurement environment, payments to vendors can only be made after a contract is formally registered and encumbered, a process which can last months. Larger, more established vendors may be in a better financial situation to contend with uncertainties regarding schedules of payments. Smaller, more local businesses cannot afford that luxury and are put at great risk when they are not paid promptly for goods and services provided to the City. As a result, many vendors, even during an emergency, are hesitant or even elect not to do business with the City out of concern they will not be able to recoup their costs in a reasonable timeframe. Moreover, vendors that choose to do business with the City during an emergency often build the anticipated delay in payment by the City into their contract pricing. By using P-cards to expedite payments, the City can potentially attract a much larger pool of vendors and can grow its existing business relationships, especially amongst smaller local businesses that are already on the ground and ready to contribute.

While P-Cards enable first responders and recovery officials to make on the spot decisions about necessary emergency spending, the ease of spending raises the potential for fraud and abuse. In order to ensure that every taxpayer dollar intended for disaster recovery is spent appropriately, the City needs to strengthen its system of fiscal controls by requiring centralized oversight, review, and audit. As the City’s chief accountant and auditor, the Comptroller’s Office would be best positioned to provide guidance on the appropriate protocols and procedures needed and monitor P-card usage to ensure cards are being used with integrity.

Conclusion

Emergencies are by definition unpredictable, but what is predictable is that New York will someday have to face another disaster. As the City continues to fortify its physical infrastructure to protect residents from future storms, we must also add a measure of fiscal resiliency to City government by building a procurement infrastructure that can respond to the next disaster with the kind of agility and efficiency that will safeguard the lives and pocketbooks of New Yorkers.

Acknowledgements

New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer extends his thanks to Lisa Flores, Deputy Comptroller for Contracts and Procurement; Jessica Silver, Assistant Comptroller for Public Affairs and Chief of Strategic Operations for the First Deputy Comptroller; David Saltonstall, Assistant Comptroller for Policy; and Nichols Silbersack, Senior Research Analyst for their work developing and writing this report.

The Comptroller also thanks Christian Stover, Bureau Chief/Legal Counsel, Bureau of Contract Administration; Enrique Diaz, Director of Management Services; Katherine Diaz, General Counsel; Jennifer Conovitz, Special Counsel to First Deputy Comptroller; Nicole Jacoby, First Deputy General Counsel; Zachary Steinberg, Deputy Policy Director; Elizabeth Bird, Policy Analyst; Angela Chen, Senior Website Developer; and Marjorie Landa, Deputy Comptroller for Audit.

Photo Credit: FashionStock.com / Shutterstock.com

Endnotes

[1] Mayor Bloomberg, “Hurricane Sandy Update as of 4:30 p.m. on Monday, November 26, 2012,” http://www.mikebloomberg.com/index.cfm?objectid=4268F80D-C29C-7CA2-FFBDCF1C1AC23DD3

[2] Office of Emergency Management, “New York City Hazard Mitigation Plan 2014,” http://www.nyc.gov/html/oem/downloads/pdf/hazard_mitigation/plan_update_2014/3.12_sandy_public_review_draft.pdf

[3] The PPB Rules identify all of the City’s procurement award methods as well as the corresponding substantive and procedural requirements for each. According to Section 3-01(b) of the PPB Rules, competitive sealed bids or “CSBs” are the preferred award method for City procurements. However, if an agency determines that it is neither practicable nor advantageous for the City to use competitive sealed bidding, it may elect to use another authorized procurement method most appropriate to the circumstances.

[4] For most non-CSB awards over $100,000, agencies are required to hold a public hearing on the proposed contract action., PPB Rule 2-11

[5]Applies only to Mayoral Agencies; Mayor’s Office of Contract Services, “Agency Procurement Indicators, Fiscal Year 2017,” https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/mocs/downloads/pdf/MWBEReports/2017_AgencyProcurementIndicators.pdf.

[6] 9 RCNY 3-06

[7] At the earliest practicable time following receipt of this prior approval, the requesting agency is required to submit a determination setting forth the basis of the emergency and the selection of the contractor to the Comptroller and the Corporation Counsel for approval. According to the Rules, this determination must include the date the emergency first became known; a list of goods, services, and construction procured; the names of all vendors solicited; the basis of vendor selection; contract prices; the past performance history of the selected vendor; a listing of prior/related emergency contract; and the Procurement Identification Number (PIN).

[8] 9 RCNY 3-06(d)

[9] 9 RCNY 3-06(b). It is worth mentioning that a catastrophic emergency event is not required to invoke use of Section 3-06 of the PPB Rules as agency purchasing agents occasionally make requests to utilize the emergency procurement method. Rather, the emergency condition is relative and must meet the standard embodied in the definition of “emergency condition” as set forth in Section 3-06(a) of the PPB Rules(contingent upon the receipt of Comptroller and Corporation Counsel approval).

[10] According to the contract terms, the City was required to purchase a minimum of 50,000 tons of salt at an average price of $55.52 and could purchase up to a maximum of 300,000 tons from each contract. The bid split the city into three zones and required the vendors to provide a separate price for each zone. Contract 1 had the following terms: Zone 1 (Manhattan/Bronx) was $59.97 per ton, Zone 2 (Brooklyn/Staten Island) was $50.25 per ton, and Zone 3 (Queens) was $57 per ton. Contract 2: Zone 1 (Manhattan/Bronx) was $53.45 per ton, Zone 2 (Brooklyn/Staten Island) was $54.62 per ton, and Zone 3 (Queens) was $57.87 per ton.

Due to the unforeseen severity and frequency of storms last winter, the City quickly ran through the 600,000 tons of salt it could purchase off its requirements contracts. DCAS on behalf of DSNY made an emergency procurement for additional salt off both vendors. As a consequence of the sheer demand for salt by other municipalities and governments impacted by the weather, the best available price the City could get per ton was $75, approximately a $20 increase. In its pursuit of any available salt, the City turned to vendors in upstate New York with available stock. One vendor was able to provide 15,000 tons of salt at the price of $74 per ton. Though this was a deal compared to the established New York State Office of General Services (OGS) contract for emergency rock salt, which pegged salt at an average of $108 per ton including delivery, it turned out to be far more costly. The vendor was unable to deliver the salt and therefore the City was required to contract with another vendor for the delivery. The total for delivery of the salt was set at a price of $140 per ton. Thus combined total per ton for the 15,000 tons of salt was $214, an astronomical increase compared to the previously established City and existing OGS contract. As part of its 2014-2015 salt contracts, the City procured the salt at an average of $63.02 a ton for a maximum purchase ceiling of 400,000 tons.

[11] Commonwealth of Massachusetts, ‘Standard Contract Form’, http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dmr/forms-pos/standard-contract-form.rtf

[12] Insurance Journal “NYC Sandy Home Repair Program Wraps Up After Fixing 20K Homes. http://www.insurancejournal.com/news/east/2013/03/26/286046.htm

[13] http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doi/press-releases/2017/feb/BIB_PR_Report_2-15-17.pdf

[14] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/08/nyregion/new-york-consolidation-shared-services.html?_r=0

[15] https://comptroller.nyc.gov/newsroom/stringer-audit-reveals-poor-management-and-shoddy-oversight-of-emergency-contracts-by-department-of-homeless-services-in-wake-of-superstorm-sandy-2/

[16] https://comptroller.nyc.gov/newsroom/stringer-audit-reveals-poor-management-and-shoddy-oversight-of-emergency-contracts-by-department-of-homeless-services-in-wake-of-superstorm-sandy-2/

[17] https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/mocs/downloads/pdf/Fiscal%202013%20Procurement%20

Indicators%20complete%20text%2010%2021_for%20web.pdf

[18] On April 3, 2013, New York City’s Procurement Policy Board adopted an amendment to its Rules raising the dollar limit for micropurchases from $5,000 to $20,000.