Executive Summary

On any given night, some 60,000 New Yorkers—more than one-third of them children—go to sleep in a City homeless shelter. Thousands more are street homeless or live doubled up with family and friends. Others are fighting to pay the rent and hold on to their apartments, one paycheck away from disaster. And yet, while the reasons that New Yorkers lose their housing are varied and very much compounded by the high cost of living in the city, New Yorkers are increasingly being driven into homelessness not only by financial pressures but by another, more hidden problem – domestic violence.

Domestic violence accounted for more than 40 percent of the family population entering Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelters in Fiscal Year 2018 – by far the single largest cause of homelessness for people entering the system. The growing number of survivors in DHS shelters is even more stunning when one considers that the City’s Human Resources Administration (HRA) runs an entirely separate shelter system geared explicitly toward domestic violence survivors that, with more than 2,500 beds, is already the largest such system in the nation. Nevertheless, despite this vast physical safety net, there is considerably more the City could be doing to help survivors build strong, independent lives and obtain permanent housing, as other cities already are.

This report, by New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, analyzes New York City Department of Social Services’ (DSS) data from July 2013 through June 2018 (Fiscal Years 2014-2018) and assesses existing policies and services to better understand the dynamics within the shelter system, the scope of domestic violence as a driver of housing instability, and identify potential gaps in State- and City-funded services. The result is the most comprehensive look to date of survivors who utilize residential services in New York City. Specifically, this report finds:

- In Fiscal Year (FY) 2018, domestic violence accounted for 41 percent of the family population entering DHS shelters, with eviction, the second-leading cause, accounting for 27 percent. That is a dramatic shift since FY 2014, when domestic violence accounted for 30 percent of the population and eviction 33 percent.

- The number of families entering shelter annually due to domestic violence increased 44 percent over the five-year period. Families entering due to eviction decreased by 13 percent, which may be partly attributed to the City beginning to implement “Universal Access to Counsel” legislation and providing New Yorkers facing eviction with free legal representation.[1]

- In FY 2018 alone, 12,541 people entered a DHS shelter due to domestic violence. That includes more than 4,500 women and 7,000 children, more than half (56 percent) of whom were five-years-old or younger.

- In addition, just over 6,400 people, mostly women of color and children, entered HRA’s separate system of domestic violence shelters (DV shelters) in FY 2018.

- The use of costly hotels for families with children entering shelter due to domestic violence has increased dramatically, with 923 such families placed in hotels in FY 2018, compared to only two in FY 2014. Overall, one in five (21 percent) survivors and family members entering the DHS shelter system in FY 2018 were placed in hotels, up from 0.1 percent in FY 2014.

- Neighborhoods in the Bronx and Brooklyn accounted for the most DHS shelter entries due to domestic violence in FY 2018 by far, with 38 percent of survivors having previously resided in the Bronx and 30 percent entering shelter from Brooklyn.

- The number of families leaving DV shelter and subsequently entering the DHS homeless shelter system increased every year between FY 2015 and FY 2018. Of families who exited DV shelter in FY 2018, more transferred into a DHS shelter (27 percent) than found subsidized permanent housing (14 percent).

Lack of safe, alternative housing is a significant barrier to and consequence of leaving an abuser, a problem that is exacerbated in a city like New York where affordable housing is scarce and rents continue to rise faster than incomes. To maintain existing housing or find new, affordable housing while also negotiating trauma and caring for young children, perhaps alone and with limited if any sources of income, is exponentially more challenging, as the data above underscore. However, this report additionally reveals that a number of structural barriers exist that make it difficult for survivors in New York City to remain stably housed, especially when compared to other jurisdictions across the country.

Over the last several years, the de Blasio administration has responded to the increasing demand for both residential services and permanent housing by increasing the capacity of the domestic violence shelter system and prioritizing survivors for subsidized housing, including New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) units; however, vacancies remain scarce. And, while survivors of domestic violence are eligible for rental assistance, the value of the City’s current voucher remains too low and landlords remain too reluctant to accept the subsidy to ensure meaningful access. At the same time, the Comptroller’s Office found significant gaps in housing protections for survivors of domestic violence in New York. While some recent policy changes at the local level, such as the right to take paid time off from work to address safety needs, have rightly positioned the city as a leader on protections for survivors, action at the state level is particularly needed.[2] Among the most noteworthy gaps in state statute is that New York is one of only two states (the other being Utah) that require survivors of domestic violence to be current on their rent in order to terminate their lease early. Other states with tight rental markets, such as California and Massachusetts, have instituted more protections than New York.

This report provides an overview of existing publicly-funded services and housing protections for New Yorkers who have experienced domestic violence and offers a number of policy recommendations aimed at strengthening survivors’ connection to housing and preventing homelessness. Key recommendations include:

- Increasing financial assistance to support survivors’ access to housing: New York State and City should work toward increasing the value of rental assistance so that survivors are actually able to make use of the subsidy while also rooting out source of income discrimination by landlords. In addition, the City should create a Survivor Housing Stability Fund, which would provide fast and flexible low-barrier grants to survivors to cover urgent expenses such as medical bills, phone costs, and transportation; increase the availability of free legal services for survivors; expand the capacity of the City’s Family Justice Centers, particularly in high-need neighborhoods; and build more affordable housing for households with very low incomes, while increasing the number of units dedicated to New Yorkers experiencing homelessness.

- Expanding residential and non-residential services: In order to ensure those survivors who want and need confidential emergency shelter have access to service-rich facilities, New York City should increase the capacity of its HRA DV shelter system and end the practice of placing survivors in the DHS system in hotels. As part of this expansion, the City should work with the State to allow survivors who need additional support to stay beyond 180 days in a DV shelter, the current time limit, on a case-by-case basis. The City must also do more to provide access to services critical to achieving long-term stability after leaving shelter, including dedicated housing specialists and additional mental health support.

- Strengthening legal protections: Addressing gaps in housing protections may mitigate a need for shelter for survivors who would otherwise choose to remain in their homes, and could do so safely. In particular, the governor should expeditiously sign recently passed legislation to strengthen New York’s early lease termination law, and policies should be enacted to improve the current lock-change policy and provide protections against termination of utility service. In addition, New York City should explore ways to reinforce its housing anti-discrimination policies, including by explicitly prohibiting discrimination in housing based on a criminal history or low credit score stemming from abuse perpetrated against a survivor.

Taking action to implement these recommendations will help shift the burden away from domestic violence survivors, creating a policy framework in which survivors have clearer paths to attaining both housing and economic stability. Ultimately, as the increasing number of survivors entering shelter in New York City makes clear, the City will not be able to achieve any significant reductions in the population experiencing homelessness without addressing domestic violence and the collateral consequences for survivors.

Domestic Violence and Homelessness in New York City

The link between domestic violence and homelessness is complex but well established, with domestic violence a leading contributor of family homelessness nationally. About 80 percent of mothers with children experiencing homelessness have previously experienced domestic violence, and a significant share of survivors in general—according to one survey, as high as 38 percent—report experiencing homelessness at some point in their lives.[3] Survivors may seek shelter as an immediate escape from an abusive situation, or after struggling for some period of time to navigate the fallout from violence: no longer being able to afford their rent, having to move to temporary or substandard housing, dealing with sabotaged employment opportunities and credit, debt, lengthy court proceedings, or limited caregiving options, among other challenges. All exact a severe toll on survivors’ financial circumstances, in addition to their health and safety, creating significant barriers to securing permanent housing.

As the data outlined in this report will show, survivors who experience homelessness in New York City are particularly vulnerable—they are overwhelmingly young women of color, they are parents to young children, and they have limited income and education, making it that much more difficult to support a family financially. Based on these characteristics alone, it is a population that would find it challenging to afford housing, child care, and other basic needs in New York City. But the addition of abuse, and the consequences that stem from it—trauma, dislocation, compromised mental and physical health—compound economic pressures and make these New Yorkers far more vulnerable to housing instability. For all of these reasons, and the structural barriers to housing stability this report highlights, thousands of survivors continue to seek shelter in New York City each year.

Survivors of Domestic Violence in the New York City Shelter System

New York City’s shelter system is expansive. The New York City Department of Homeless Services (DHS) manages hundreds of temporary shelter facilities for families with children, adult families, and single adults, housing about 60,000 people on average per day.[4] Meanwhile, the New York City Human Resources Administration (HRA) oversees a separate system of State-mandated, time-limited confidential emergency shelters as well as transitional facilities exclusively for survivors of domestic violence – the largest domestic violence shelter system in the country. At any given time, survivors may be moving into, out of, and between these DHS and HRA facilities.

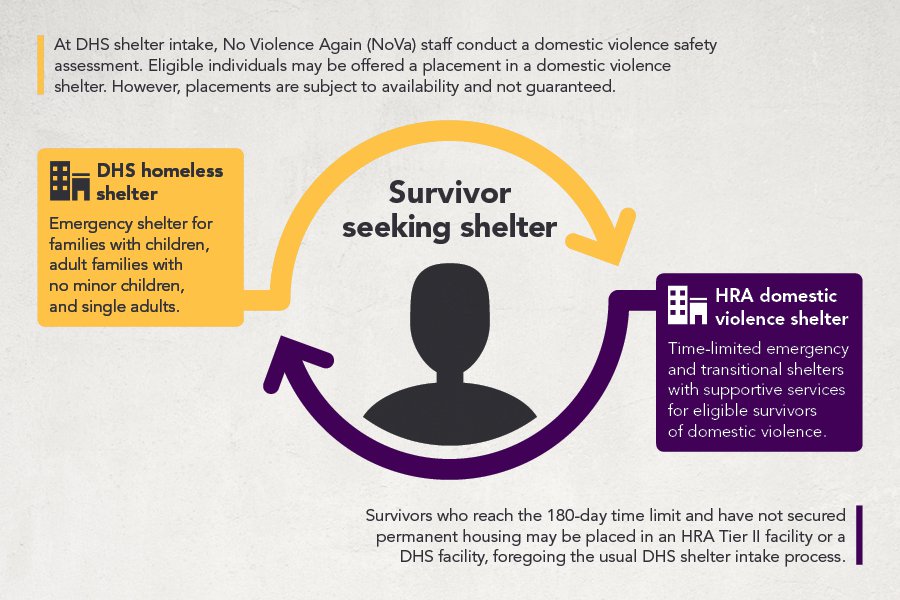

There are a number of paths survivors can take to access shelter in New York City. They may be connected to one of HRA’s domestic violence shelters (DV shelter) by calling the City’s domestic violence hotline, or through a referral from another City program or community-based organization. Survivors may also present at a DHS homeless shelter intake center, where staff with HRA’s No Violence Again (NoVA) program will conduct an assessment for DV shelter eligibility. To be eligible, an individual seeking temporary shelter must provide information that establishes they or their child(ren) are a victim of domestic violence, as defined by the State.[5]

If an offer of a placement in an HRA shelter is made and accepted, survivors may stay in emergency DV shelter for an initial period of 90 days, with two 45-day extensions allowed for up to a total of 180 days.[6] These time limits are imposed by the State and are intended to ensure that domestic violence shelter beds are available for those who are in imminent danger. Survivors who reach the time limit and have not yet obtained permanent housing may be discharged to an HRA Tier II transitional shelter, or transferred to a DHS homeless shelter, where there is no statutory limit on how long a resident can stay.[7] Survivors for whom a placement in DV shelter cannot be made, either due to inadequate capacity or ineligibility, can still be placed in temporary housing in the DHS shelter system, as many are each year.[8]

| HRA Domestic Violence Shelter System |

| The New York State Domestic Violence Prevention Act, enacted in 1987, requires counties to provide shelter and supportive services to survivors of domestic violence, and the State Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS) promulgates regulations establishing the responsibilities of localities in contracting with service providers to offer these residential programs. HRA oversees a system of 55 confidential residential domestic violence facilities, including nine domestic violence Tier II transitional facilities, which are intended to provide shelter for survivors who require additional support beyond their stay in emergency shelter.[9] Survivors are required to receive counseling, referrals, child care services, job assistance, and support in obtaining permanent housing. The private shelter providers with which HRA contracts are charged with helping individuals and families navigate violence and trauma, connecting survivors to the enhanced services and therapy critical to attaining housing stability. Mental health services are provided either on or off site.[10] |

In 2015, in recognition of the demand for DV shelter beds, Mayor de Blasio and HRA Commissioner Steven Banks announced a plan to gradually expand the capacity of the city’s domestic violence shelter system with the addition of 300 emergency shelter beds and 400 Tier II transitional units. No beds had been added during the previous five years. As of September 2019, HRA reported that all 300 emergency shelter beds had been awarded to providers, as well as 295 of the planned 400 Tier II units. As of that date, the total system-wide capacity was 2,514 emergency beds and 362 Tier II units.[11] The City now serves more families on average per day in DV shelters than several years ago, but even as the capacity of the DV shelter system has grown, entries to DHS homeless shelters due to domestic violence have continued to climb.[12]

Shelter Entry Over Time

To better understand the scope of domestic violence as a cause of homelessness in New York City, the Comptroller’s Office analyzed anonymized data from the New York City Department of Social Services (DSS) for Fiscal Years 2014 through 2018 (July 2013 through June 2018). Data included all households found eligible by DHS for shelter during the time period, all new entries to HRA domestic violence shelters, and any transition between the two shelter systems, making this analysis the most comprehensive look to date at survivors who utilize residential services in New York City.

Domestic violence is primary driver of DHS shelter population

Between July 2013 and June 2018 (FY 2014-2018), according to the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis, more than 18,000 families, including 52,500 adults and children, entered the DHS shelter system due to domestic violence, the numbers increasing each year between FY 2015 and FY 2018. In FY 2018, as shown in Chart 1, 4,467 families, including 12,541 people, entered a DHS shelter due to domestic violence. This represented a 44 and 37 percent increase, respectively, from FY 2014, when 3,096 families and 9,133 individuals were found eligible.

Chart 1: DHS Shelter Entries due to Domestic Violence, FY 2014-2018

The Comptroller’s Office also examined entries to DV shelter and found 6,409 individuals in 2,519 families were placed in a DV facility during FY 2018. Some of these individuals entered a DHS shelter as well that year, as will be discussed in more detail below, and are counted among the population shown in Chart 1. Excluding these families reveals that over 6,300 unique households and over 17,200 unique people entered the DHS or HRA DV shelter systems in FY 2018 as a direct result of domestic violence.

In FY 2018, as in the preceding two years, domestic violence was the single largest contributor to the family population entering DHS shelter, accounting for 41 percent of the population (Chart 2). Eviction, the second-leading cause, accounted for a distant 27 percent of the population. As Chart 3 shows, this is a reversal from FY 2014, when eviction was the top reason for eligibility, accounting for some 33 percent of all families entering shelter. That year, 30 percent of families entering shelter did so due to domestic violence. The actual number of families entering shelter as a result of eviction decreased 13 percent, which may be partly attributed to the City beginning to provide free legal representation to New Yorkers facing eviction.[13]

Chart 2: Families Entering DHS Shelter by Reason for Eligibility, FY 2018

Note: “Domestic Violence” includes families NoVA found eligible for DV shelter and those who did not meet the standard for DV shelter but are still reported eligible for shelter primarily due to domestic violence. “Other Reasons” includes entries due to a “crime situation,” “financial strain,” or other reason not enumerated. Families reported as “Immediate Returns” are excluded.

Chart 3: Families Entering DHS Shelter by Reason for Eligibility, FY 2014-2018

Note: “Domestic Violence” includes families NoVA found eligible for DV shelter and those who did not meet the standard for DV shelter but are still reported eligible for shelter primarily due to domestic violence. “Other Reasons” includes entries due to a “crime situation,” “financial strain,” or other reason not enumerated. Families reported as “Immediate Returns” are excluded.

The fact that the number of survivors entering DHS shelter has been rising both in absolute terms and as a proportion of all shelter residents may in part reflect increased referrals and disclosures, as well as improved reporting and identification during the shelter intake process. However, other metrics by which the City and State track the incidence of domestic violence suggest that such cases may be on the rise. Annual reports from the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services show the number of victims of assault, sex offenses, and, in particular, violations of orders of protection has increased nearly every year over the last decade.[14] And according to a report released by the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice and Mayor’s Office to End Domestic and Gender-Based Violence (formerly the Mayor’s Office to Combat Domestic Violence), domestic violence went from representing some 4.8 percent of all major crimes in the city in 2007 to 11.6 percent in 2016.[15] Domestic violence accounts for nearly one in five homicides in New York City.[16]

Survivors in Shelter by Facility Type

The DHS shelter system includes three types of residential facilities: shelters, which are generally entirely occupied by people experiencing homelessness and offer on-site supportive services; “cluster sites,” individual apartments in buildings with a mix of DHS clients and renters, with limited or no services on site; and commercial hotels, individual hotel rooms rented out by the City. While hotels have historically offered clients limited access to services and other essentials, such as kitchen facilities, in 2018, the City announced that it would contract with a provider to offer some services to clients in these settings.[17]

As Comptroller Stringer has testified and written elsewhere, cluster units and commercial hotel rooms can pose serious health and safety risks to families experiencing homelessness. Cluster units have historically been in buildings with numerous open Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) and Department of Building (DOB) violations. Additionally, commercial hotels, in addition to being the most costly DHS shelter intervention, are less secure and service-rich than family shelters. In Turning the Tide on Homelessness, the mayor’s plan to address the city’s homelessness crisis, the de Blasio administration outlined its proposal to end the use of cluster sites and commercial hotels by the end of 2021 and 2023, respectively, largely by expanding and opening new shelters.[18] As progress has been made in reducing the use of cluster sites, however, the City’s reliance on hotels has increased.

As shown in Chart 4, the majority of families entering shelter due to domestic violence between FY 2014 and FY 2018 resided in a traditional DHS shelter for families with children. However, a combined 1,200 families with children found eligible for shelter due to domestic violence were placed in cluster sites and hotels in FY 2018. While only two families with children entering shelter due to domestic violence in FY 2014 were placed in hotels, 923 families were in FY 2018, including some 271 families NoVA staff concluded were eligible for DV shelter. One in five (21 percent) survivors and family members entering shelter in FY 2018 were placed in hotels, up from 0.1 percent in FY 2014. Use of cluster sites, on the other hand, declined over the time period examined, though not as sharply as the increase in hotels. In FY 2018, 277 domestic violence-eligible families with children entering shelter were placed in cluster sites, down 28 percent compared to FY 2014.

Chart 4: DV-Eligible Families Entering DHS Shelter by Facility Type, FY 2014-2018

Residence Prior to Entering Shelter

As shown in Chart 5, neighborhoods in the Bronx and Brooklyn accounted for the most DHS shelter entries due to domestic violence in FY 2018, with 38 percent of survivors having previously resided in the Bronx and 30 percent entering shelter from Brooklyn. More survivors entered shelter from the Hunts Point, Longwood and Melrose neighborhood in the Bronx than any other community, followed by Belmont, Crotona Park East, and East Tremont and Bedford Park, Fordham North, and Norwood, also in the Bronx (Table 1). Median household income in these neighborhoods ranges from about $24,000 to $34,000 a year, underscoring the economic challenges survivors in shelter face.[19] In FY 2018, more than half of all families entering the DHS shelter system due to domestic violence had previously lived in one of the top ten neighborhoods listed in Table 1.

Chart 5: Borough of residence prior to entering DHS shelter, as share of total families found eligible due to domestic violence, FY 2018

Note: Excludes survivors whose residence prior to entering shelter was outside the five boroughs.

Table 1: Top 10 NYC neighborhoods where DV-eligible families lived prior to entering DHS shelter, as share of total families found eligible due to domestic violence, FY 2018

Note: Excludes survivors whose residence prior to entering shelter was outside the five boroughs.

Transitions and Exits from Shelter

Data on exits from shelter—and movement between the two systems—show survivors are discharged to a variety of housing placements, not all subsidized or permanent. In FY 2018, as shown in Chart 6, 1,839 families, or just under half (49 percent) of survivors exiting a DHS shelter, were reported to have exited to permanent housing with a subsidy. Of these families, about two-thirds received some form of rental assistance, while an additional 28 percent secured housing through NYCHA. Only 2 percent of families exited to supportive housing. The number of families exiting DHS shelter with a subsidy, regardless of domestic violence status, increased significantly over the time period examined. Yet, about 43 percent of survivors who exited DHS shelter in FY 2018 were still discharged to unsubsidized housing. This is concerning given that families who exit to permanent housing with a subsidy are much less likely than families in unsubsidized placements to return to shelter. According to the most recent Mayor’s Management Report, one in five (21.6 percent) families with children exiting to an unsubsidized placement returned to shelter within one year, while only 1.3 percent of families with children with a subsidy returned to shelter.[20] An additional 196 families exited the DHS system in FY 2018 to a DV shelter, likely due to DV beds becoming available.

Chart 6: Placement of survivors and family members exiting DHS shelter, FY 2018

Note: Includes all families entering DHS shelter due to domestic violence who exited DHS shelter in FY 2018 and did not return to DHS shelter within 30 days. A subsidized exit means that the client has permanent housing and a subsidy to support it, while an unsubsidized exit means that the client has a permanent placement but no subsidy. “Exit on Own” means that the family left shelter but that it was not a subsidized or unsubsidized exit. Families are considered to have exited to “DV Shelter” if they left the DHS shelter system and entered a DV shelter within 30 days.

The Comptroller’s Office’s analysis indicates that the vast majority of survivors do not have subsidized housing when they are discharged from DV shelter (Chart 7). Out of 2,212 families exiting in FY 2018, only 307 or 14 percent were discharged with a known housing subsidy, most often a City rental assistance voucher. Of those 307 cases, one-quarter exited to NYCHA, and only 2 percent were discharged to supportive housing. Another 1,301 or 59 percent of families exiting in FY 2018 were discharged to unsubsidized housing, and 604 or 27 percent of exiting families did not move to permanent housing at all but rather entered the DHS homeless shelter system. This latter outcome is particularly concerning, given the harm that additional instability can do to survivors’ healing processes, and the fact that residential instability and frequent moves may heighten children’s risk of poor health and academic outcomes.[21] The families who enter the DHS shelter system after spending time in one of HRA’s DV shelters have already had to upend their lives and routines at least once before, when they sought emergency shelter, and must still contend with a temporary housing situation. The Comptroller’s Office’s analysis found that the number of families exiting DV shelter and subsequently entering the DHS shelter system increased every year between FY 2015 and FY 2018, as did the number of families who timed out of DV shelter. This is at least partly due to the City beginning to enforce the 180-day time limit during this time, after previously allowing families to stay in shelter longer.[22] In FY 2018, half of all families exiting DV shelter who had timed out of emergency shelter subsequently entered the DHS shelter system.

Chart 7: Placement of families exiting DV shelter, FY 2018

Note: Includes all cases exiting DV shelter in FY 2018 that did not return to shelter within 30 days. A subsidized exit means that the client has permanent housing and a subsidy to support it, while an unsubsidized exit means that the client has a permanent placement but no subsidy. Families are considered to have exited to “DHS Shelter” if they left a DV shelter and entered a DHS shelter within 30 days.

The increasing number of New Yorkers who are experiencing homelessness as a result of domestic violence, including after staying in the DV shelter system for several months, points to the fact that this is a population that faces a number of acute challenges to regaining housing stability, many directly related to the abuse perpetrated against them and others heightened by it. For instance, while the data provided to the Comptroller’s Office do not enumerate the mental health needs of survivors or resources offered to them, existing research does indicate that survivors in City shelters are likely to be navigating significant trauma—and continue to exhibit signs of trauma when it is time to exit shelter. More than two-thirds (68 percent) of participants in Safe Horizon’s Lang Study, for example, met criteria for clinical depression when they entered a DV shelter, and more than half (56 percent) of participants met the criteria for clinical depression after exiting, while 37 percent met the criteria for PTSD when discharged.[23] While some survivors are able to make progress in addressing the adverse mental health consequences of domestic violence during their time in DV shelter, this study suggests that some survivors would benefit from, and should have access to, longer-term support. For some, 180 days in a DV shelter is simply not enough time to take care of urgent health issues and secure permanent housing. As a point of comparison, the average length of stay for families with children in shelter is now 446 days.[24]

Indeed, survivors in the DV shelter system must, given the 180-day time limit, quickly prioritize identifying financial resources and navigating any rental assistance applications that may be needed to move to permanent housing. But this can take a long time, given the limited availability of affordable housing and access to publicly-funded supports. And survivors’ limited access to higher education poses additional barriers to securing employment that, in the long term, will enable them to afford unsubsidized housing and support themselves and their families financially. In FY 2018, according to the Comptroller’s Office analysis, 31 percent of heads of households entering the DV shelter system and 37 percent of heads of households entering DHS shelter due to domestic violence had not completed high school.

Individuals impacted by domestic violence in both the DHS shelter system and in DV shelters also tend to be caring for very young children. As Chart 8 shows, more than half of the population entering DHS shelters due to domestic violence and DV shelter in FY 2018 were children; just under one-third of the population and more than half of all children were five-years-old or younger. As the Comptroller’s Office has written previously, the high costs associated with caring for young children in New York City—child care now costs more on average than rent in every borough—place significant pressure on families’ budgets, making it that much more difficult to achieve financial stability.[25]

Chart 8: Survivors and family members entering shelter by age, FY 2018

Lastly, it is important to emphasize that survivors in shelter in New York City are overwhelmingly women of color. Based on the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis, 89 percent of adults entering DV shelter and 90 percent of adult survivors in DHS shelter in FY 2018 were Black or Latinx, and 96 percent of adults entering DV shelter and 83 percent of adults in families entering DHS 0shelter due to domestic violence in FY 2018 were women.[26] In addition to having, on average, limited economic resources, these survivors must also contend with both overt and more subtle gender- and race-based discrimination in their daily lives, which contributes to housing instability and impedes the path to gaining safe, permanent housing in largely unquantifiable but material ways.

Services and Housing Protections for Survivors

In New York City, a variety of publicly-funded resources are available to survivors at risk of or experiencing housing instability to prevent homelessness and help secure permanent housing – from safety planning and counseling, to legal services and rental assistance. New York State and New York City’s housing laws afford survivors additional protections. Between fiscal years 2013 and 2018, the period of time this report focuses on, the City took significant steps both to expand and enhance what assistance is offered, with an eye toward addressing the short- and long-term needs of survivors. The Comptroller’s Office’s review of housing-related services and protections for survivors of domestic violence in New York City highlights some of the persistent barriers to housing stability and potential opportunities for additional improvements and reform.

New York City’s Family Justice Centers

The Mayor’s Office to End Domestic and Gender-Based Violence (ENDGBV) operates the City’s five Family Justice Centers (FJCs), which are co-located with the five district attorney’s offices. The FJCs, the first of which opened in Brooklyn in 2005 under a federal grant, function as comprehensive one-stop, multi-service centers where survivors of domestic violence can gain access to a variety of free services from both City agencies and community-based organizations. In addition to having non-profit community partners on site who can provide civil legal assistance and counseling, there are representatives from HRA, Health+Hospitals, and the New York City Police Department (NYPD) to help families navigate processes such as DV and DHS shelter intake, address health needs, and obtain orders of protection. One of the benefits of consolidating all of these resources in one facility is that it alleviates the need for survivors to have to travel to multiple appointments with different agencies across the city, which can be not only challenging to negotiate with work and children in tow but also emotionally draining, as it often requires survivors to continually retell their experiences of abuse. Survivors do not need to have an appointment to be seen at the FJCs, and child care is offered on-site.[27]

In 2019, through September 1, the FJCs collectively served nearly 18,000 unique clients over 43,000 visits, and according to testimony provided to the City Council in September 2019, 1,300 clients received housing and shelter advocacy, with 600 receiving assistance in being placed in domestic violence emergency shelter.[28] One relatively new service provided on site at the FJCs are mental health clinicians, an important addition given the mental health needs of survivors. As of September 2019, the FJC Mental Health Program was reported to have served 340 unique clients.[29]

Nationally, the Family Justice Center model is considered a best practice in addressing the multiple and interconnected needs of survivors of domestic violence, but there are ways in which New York City’s centers could be made even more accessible to families and individuals impacted by violence. For example, the FJCs are generally open Monday through Friday from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., with limited evening hours, and do not offer weekend service.[30] Additionally, the proximity of the FJCs to the courts and law enforcement may deter some survivors from seeking help.

HRA Non-Residential Services and Resources for Survivors

In addition to overseeing the largest domestic violence shelter system in the country, HRA contracts with nine community-based organizations to provide non-residential services to New Yorkers impacted by domestic violence.[31] Services that must be offered, per the State Office of Children and Family Services, include a domestic violence hotline providing immediate referrals and counseling for individuals in crisis; advocacy in accessing legal protections, medical care, employment, housing, and other public benefits; counseling; and community education.[32] While these supportive services may mitigate a need for shelter, they are also intended as aftercare so that families transitioning out of DV shelter have the supports needed to maintain permanent housing and build financial security.

HRA also runs Alternatives to Shelter (ATS), a program designed to give more survivors of domestic violence the option of staying safely in their homes, rather than having to seek temporary shelter. Participants in the program are provided with a personal alarm system that is connected to local police precincts and offered case management services such as counseling, safety planning, and referrals to other services. Eligibility for the program is limited to survivors with an order of protection, and ATS does not come with financial assistance to support the costs of maintaining housing. Still, ATS managed an active caseload of 195 clients on average per month in 2018.[33]

HRA’s Office of Civil Justice (OCJ) oversees implementation of the City’s Universal Access to Counsel Law, which passed in August 2017 and provides free legal representation to income-eligible tenants facing eviction in housing court. The program is being phased in over time by zip code, with free legal representation available to residents of twenty zip codes, four in each borough, as of 2018; and the City expects to reach every tenant with an eviction case citywide by 2022.[34] In FY 2018, OCJ reported providing legal services to 26,000 households facing eviction proceedings, and in the final quarter of FY 2018, 30 percent of tenants with eviction cases in housing court had legal representation.[35] This may partly account for the declining number of families entering shelter due to eviction.

Given the prevalence of economic abuse and risk of eviction faced by many survivors, Universal Access to Counsel should be an enormous benefit for survivors who may have an eviction case against them as a result of domestic violence. However, only two of the zip codes currently served are among the top ten zip codes from which survivors entered the DHS shelter system in FY 2018, according to the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis.[36] According to HRA’s testimony to the City Council, more than 3,000 survivors and family members have received housing legal assistance through referrals made at the city’s FJCs, though how many were represented in eviction proceedings is unclear.[37] HRA’s report on the first year of implementation of the Universal Access to Counsel Law does not indicate whether tenants served had experienced domestic violence, or if those data are being tracked.[38]

The City’s new investments in homelessness prevention, including free legal representation, are significant, but there remain few publicly-funded, low-barrier options to help survivors avert shelter entry. For instance, the City does not currently have a dedicated fund specifically for survivors at risk of losing their housing. Yet outcomes in other areas of the country where survivors have access to emergency grants make a compelling case for such programs. The District Alliance for Safe Housing in Washington, D.C., for example, has developed a financial assistance program called the Survivor Resilience Fund, which provides fast and flexible emergency funds to survivors to address threats to permanent housing, covering expenses such as utility bills, home or car repairs, moving costs, or rent. An evaluation of the fund found that 94 percent of clients served remained safely housed six months after receiving the grants, which ranged from a couple hundred dollars to over $8,000.[39] Even at the high end, this is a much less costly intervention than shelter for survivors who can remain in their homes or safely relocate.

City Rental Assistance

Survivors of domestic violence in shelter or at risk of losing their housing who meet certain income and other eligibility criteria may be able to access rent subsidies from the City to help afford permanent housing. Currently, the primary rental assistance program available to survivors is the City’s Fighting Homelessness & Eviction Prevention Supplement (CityFHEPS), which is administered by HRA and replaced the de Blasio administration’s earlier rental subsidy program, Living in Communities (LINC). The maximum monthly rent toward which a voucher can be applied is capped based on family size, ranging from $1,246 for one individual to $1,557 for a family of three or four, and rising from there, and indexed to any annual rent increases for one-year lease renewals set by the New York City Rent Guidelines Board.[40] These maximum rents align with the State-funded Family Homelessness and Eviction Prevention Supplement (FHEPS), which is targeted to families who receive or qualify for cash assistance, including those in DV shelter.[41]

However, New Yorkers who have received rental assistance, as well as many housing and economic justice organizations, have voiced concern that the value of the rent subsidies is too low to support meaningful access to permanent housing.[42] And, even if families can find an apartment, they are too often met with landlords reluctant to accept the subsidy, despite it being illegal for landlords to refuse to rent to tenants with vouchers.[43] Legislation has been introduced at both the state and city level to address some of these challenges. In New York City, for example, legislation introduced in the City Council would require, subject to appropriation, the maximum allowable rent to increase annually at the same rate as the fair market rent set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).[44] For FY 2020, the HUD fair market rent for New York City is $1,714 for a one-bedroom apartment and $1,951 for a two-bedroom apartment, well above CityFHEPS assistance for a family of four.[45]

At the state level, legislation is pending that would establish a new rent supplement program called Home Stability Support, which would fund up to 85 percent of the fair market rent determined by HUD, with the option for localities to fund up to 100 percent.[46] Home Stability Support would allocate up to 14,000 new shelter supplements each year to localities, including New York City, based on their share of the state population with incomes below the federal poverty level. Assistance would be available to individuals and families who are homeless or face an imminent loss of housing, which includes those “fleeing, or attempting to flee, domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, stalking, human trafficking or other dangerous or life-threatening conditions.”[47] The legislation would also provide for support services to assist families in achieving long-term housing stability, including help resolving conflicts with landlords and negotiating leases. As of October 2019, the Senate bill had over 30 co-sponsors and the Assembly bill over 100, but neither had been put to a vote outside committee.[48]

Access to Public Housing and Housing Choice Vouchers

Survivors of domestic violence are given N1 priority, the second-highest needs-based preference, for public housing units that become available in the city; however, a small number of New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) units are made available annually, and hundreds of thousands of families remain on waiting lists. In 2014, the de Blasio administration reestablished priority placement for homeless families, after the Bloomberg administration had ended the practice of setting aside NYCHA units for these families.[49] The number of survivors in the DHS and HRA shelter systems exiting to a NYCHA placement has since generally increased, according to the Comptroller’s Office analysis of DSS data from FY 2014 through FY 2018. Nevertheless, vacancies remain scarce, and eligibility is limited based on immigration status.

As with public housing, the demand for federally-funded housing choice vouchers, or Section 8 vouchers, far outstrips the supply, and survivors experiencing homelessness appear to comprise a small share of families who receive them. Based on DHS and HRA data provided to the Comptroller’s Office, 91 survivors exiting DHS shelter and 19 exiting HRA shelters in FY 2018 received Section 8 vouchers, the equivalent of 7 percent of the housing choice vouchers issued by the City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) during that time period.[50] HPD, NYCHA, and New York State Homes and Community Renewal (HCR) all operate housing choice voucher programs in the city and are permitted, per federal rules, to establish priority populations. HPD’s program gives priority to households experiencing homelessness and residing in HRA domestic violence shelters.[51] Under NYCHA’s plan, New Yorkers experiencing homelessness are given the highest priority for vouchers, and survivors of domestic violence are listed as the second-highest preference; however, NYCHA is not currently accepting applications.[52] The waitlist for HCR’s program in New York City is also closed.[53]

The dearth of funding for and survivors’ limited access to housing choice vouchers are particularly perverse given research on homelessness policy interventions. The most rigorous study to date of the impact of different housing and service interventions for families experiencing homelessness, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Family Options Study, underscored the effectiveness of housing subsidies. Access to a long-term housing subsidy was found to be a more successful intervention in reducing family homelessness than temporary transitional housing with supportive services and community-based rapid re-housing (short-term rental assistance with more limited services).[54] Nearly half of the participants in the study reported experiencing domestic violence as an adult.[55] Assignment to the group receiving a long-term housing subsidy was not only associated with sustaining housing but also found to reduce incidence of intimate partner violence more than three years after initial receipt.[56]

New York City’s Domestic Violence Task Force

In November 2016, in recognition of the demand for domestic violence services and in response to an increase in domestic violence-related offenses relative to other crimes in the city, the de Blasio administration created the New York City Domestic Violence Task Force, with the aim of strengthening the City’s response to domestic violence and identifying and addressing critical service needs. Co-chaired by First Lady Chirlane McCray and NYPD Commissioner James O’Neill and comprised of representatives from a number of City agencies, community-based organizations, and directly impacted communities, the Task Force released a report in May 2017 outlining its intended areas of focus and recommendations for further City investment.[57] The scope of the report, and the work of the Task Force, extend beyond the ways in which domestic violence impacts housing instability; however, two of the 27 recommendations put forward related to housing: (1) continuing to offer housing legal assistance at the New York City Family Justice Centers and (2) exploring legislative and procedural mechanisms to increase housing protections for domestic violence survivors.[58]

In October 2017, the City announced an additional investment of $3.9 million in initiatives informed by the task force’s recommendations. These included a program called Home+Safe, an initiative to equip survivors and family members with “high-tech alarm systems,” designed to keep families who could otherwise stay safely in their homes stably housed.[59]

Domestic Violence and New York Housing Laws

New York offers additional protections and rights for survivors at risk of experiencing homelessness through state and local law. The expansion of New York City’s Earned Sick Time Act in May 2018 to include safe leave, which allows covered employees to use accrued paid leave to take safety measures in instances of domestic violence, is one such recent example.[60] The below summary of existing housing protections for survivors highlights areas in which New York falls short of rights offered in other jurisdictions, drawing from existing research on best practices as well as state and local legislation compiled and published by the National Housing Law Project.[61]

Early Lease Termination

The majority of states have policies in place that enable tenants to terminate their lease early due to a documented experience of domestic violence. These laws are intended to help survivors leave unsafe housing situations by minimizing the financial risk and consequences associated with breaking a lease. While New York allows for early lease termination due to domestic violence, its statute is among the most restrictive such laws nationwide, and survivors who wish to leave an apartment have to meet a series of increasingly onerous criteria in order to legally break a residential lease.

First, New York’s early lease termination law, New York Real Property Law 227-c, only applies to survivors who have obtained an order of protection, which people who are experiencing domestic violence may not want to seek for a number of reasons. In addition to fear of escalating abuse, survivors may be reluctant to contact law enforcement or access the court system. Given the current federal immigration policy regime, survivors with an undocumented immigration status may be especially unlikely to seek a court order.[62] It is worth noting that under local law, survivors cannot be denied access to a domestic violence shelter based solely on lack of documentary evidence of abuse, such as an order of protection.[63]

Among the five major cities in the U.S. with the largest populations of people experiencing family homelessness—New York City, Los Angeles, Boston, District of Columbia, and Seattle—New York is the only one in which an order of protection is required for survivors to break a lease.[64] The other four jurisdictions all, under state or local law, accept third-party documentation from professionals such as medical providers and clinical social workers, individuals who survivors may be more likely to trust or with whom they may already have established relationships, to provide proof of a domestic violence situation. In Massachusetts, the law is even more generous, explicitly stating that landlords do not need to ask for proof of violence.[65]

New Yorkers who have an active order of protection must seek an order from the court that issued the order of protection to terminate their lease and first provide ten days’ notice of their intention to do so to their landlord and any co-tenants. The requirement to notify co-tenants, which may mean the abuser, puts survivors in the precarious position of having to risk additional harm. According to client advocates, this provision of the law prevents some survivors from seeking to formally terminate their lease at all. If there are tenants on the lease in question who are not the survivor applying for early lease termination or the person covered by an order of protection, State law does allow for the lease to be split, or bifurcated, with the consent of the other tenant(s) so they may remain on the lease. A separate piece of State legislation recently signed by the governor specifically allows for the continued tenancy of the survivor following the lease termination or eviction of the abuser.[66]

Per New York Real Property Law 227-c, a court may grant a lease termination if certain terms are met, including that all rent due through the termination date has been paid. According to testimony provided to the New York City Council by the Legal Aid Society, New York is one of only two states (the other being Utah) that requires survivors to be current on their rent in order to legally end their lease.[67] What this means in practice is that survivors who choose to leave an abusive environment and seek other housing can be sued for back rent they may not know was never paid, particularly if their abuser controlled their finances. Despite longstanding research establishing the link between domestic violence and economic abuse, this policy has meant that survivors can be saddled with litigation and expenses for debt they did not incur for years to come, compromising their ability to afford safe, stable housing.

Fortunately, legislation passed in both the New York State Senate and Assembly this year but not yet signed into law would address the serious flaws in New York’s early lease termination policy.[68] The bill would allow survivors to begin the process of terminating their lease without first seeking a court order and would remove the requirement that they must notify any co-tenants, in cases where the co-tenant is the abuser. Survivors would also be able to provide a variety of forms of documentation to corroborate their experience of domestic violence, including police reports, medical records, and written verification from third parties such as attorneys, social workers, therapists, staff of domestic violence service providers, clergy, and family members. Importantly, the legislation eliminates the requirement that tenants be current on their rent.

Housing Anti-Discrimination and Protections Against Eviction

New York is one of several states that prohibits discrimination in housing based on domestic violence, in recognition of the fact that discrimination by landlords, lenders, and brokers can be one barrier to securing housing stability. At the state level, it is against the law for a landlord to refuse to rent a unit to a prospective tenant based on their status as a survivor of domestic violence, to alter the terms or conditions of a lease agreement based on such status, or to include discriminatory language in any statement, advertisement, or publication.[69] State law permits localities to impose additional anti-discrimination protections, and New York City has done so. As of July 2016, it is a violation of the New York City Human Rights Law to discriminate against a survivor of domestic violence, sex offense, or stalking looking for an apartment, applying for housing, or residing as a tenant. Survivors cannot be refused an apartment showing, offered different lease terms, or required to leave an apartment because of their identity as a survivor.[70]

While New York City employs a more expansive definition of domestic violence for these purposes than many other localities, some jurisdictions do offer other protections. Oregon, for example, has for many years prohibited landlords from terminating a tenancy, increasing rent, decreasing services, or refusing to enter a rental agreement because of criminal activity relating to domestic violence where the tenant or applicant for tenancy was the victim.[71] Neither the State nor New York City explicitly prohibit discrimination in housing on the basis of criminal activity or criminal history resulting from an experience of domestic violence.

In addition to these anti-discrimination protections, the federal Violence Against Women Act prohibits landlords participating in federally-subsidized housing programs from terminating assistance due to domestic violence, and many states have enacted protections against eviction in the private market. In New York, it is illegal for a survivor to be evicted because of their status as a domestic violence victim.[72] New York City additionally prohibits landlords from evicting a tenant on the basis that a residential unit has not been occupied when the tenant is a victim of domestic violence, has left the unit because of domestic violence, and plans to return.[73]

Right to New Locks

New York’s Multiple Dwelling Law allows for tenants to install locks on the entrance to their own unit in addition to the lock supplied by the landlord, a critical safety measure for many people experiencing or at risk of violence, but does not provide the right to request a landlord to change the locks on a tenant’s unit or the exterior door of a multiple-dwelling building.[74] Moreover, a tenant cannot lock out a co-tenant without a court order. Tenants are responsible for the cost of installing new locks; however, some community-based organizations provide financial assistance to survivors expressly for this purpose.

As of December 2017, according to the National Housing Law Project, 18 states had established laws regarding lock changes for survivors, with survivors generally required to pay the associated costs.[75] Many of these statutes require landlords to install new locks within a certain period of time. In California, for example, landlords are required to change the locks to a residential unit within 24 hours of a request made by a tenant with either a court order or a police report indicating they are a victim of domestic violence.[76] However, when a survivor lives with the perpetrator, a court order is required.[77] In the District of Columbia, landlords have five business days to fulfill a request for new locks, but no documentation of violence is required if the survivor does not live with the perpetrator. Additionally, the landlord is responsible for initially paying for the cost of changing the locks, with the survivor required to reimburse the landlord for the cost and any additional fee within 45 days.[78] Indiana’s statute makes landlords who fail to comply with lock-change requests within the specified time period fully liable for the cost.[79] Several states and the District of Columbia have established statutes explicitly stating that landlords are immune from civil liability for changing the locks in good faith.

Access to Utility Service

Utility service is necessary to sustain safe, habitable permanent housing, but for some survivors, utility bills are a contributing factor to economic insecurity, putting them at increased risk of experiencing homelessness. Utility companies may hold survivors responsible for arrears incurred jointly with or solely by their abuser and seek to terminate or refuse service.[80] New York Public Service Law does require the continuation or restoration of gas, electric or steam service under certain circumstances to persons experiencing medical emergencies, as well as customers who are elderly, blind, or disabled, but does not explicitly include survivors of domestic violence.[81]

Pennsylvania has among the strongest utility protections for survivors. Under Pennsylvania’s Public Utility Law, standard requirements regarding collection of reconnection fees and outstanding balances and reporting of delinquent customers do not apply to survivors of domestic violence with restraining orders.[82] Additionally, in cases where an abuser was the account holder, service cannot be terminated for nonpayment and survivors cannot be held responsible for arrears unless a court has determined the survivor is obligated to pay.[83] According to a guide published by the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission, service cannot be turned off in winter without the approval of the commission, and special arrangements for payment may be made for survivors based on income.[84]

Illinois requires utility companies to defer credit and deposit requirements for 60 days for customers who are documented survivors of domestic violence.[85] To qualify for deferment, survivors must have an order of protection or certification from a medical professional, law enforcement personnel, a State’s Attorney, the Attorney General, or a domestic violence shelter. A handful of other states specify in statute that the perpetrator of violence may be required to ensure the continuation or restoration of utility service as a condition of an order of protection.[86]

Policy Recommendations

Survivors of domestic violence face many barriers to building safe, independent lives, among them unmet mental health needs, lack of permanent, affordable housing, and limited financial resources. Despite the investments that the City is already making, not only in the shelter systems but also in non-residential services for survivors, the data in this report make clear that existing resources are not sufficient to prevent homelessness for thousands of New Yorkers impacted by domestic violence. All survivors in New York City should be able to access the care and resources needed to address threats to their health and safety, and for some, that includes access to a confidential DV shelter. However, as this report shows, many survivors of domestic violence are needlessly moving into DHS homeless shelters, a costly intervention and very often a worst-case scenario for survivors. Indeed, how many New Yorkers choose to stay in or return to an unsafe housing situation each year to avoid homelessness remains unknown.

Based on the Comptroller’s analysis of the population in shelter due to domestic violence and the scope and availability of existing resources and protections, the Comptroller’s Office proposes three overarching recommendations to increase housing stability for survivors in New York City: (1) increase financial assistance to support survivors’ access to permanent housing; (2) expand residential and non-residential services; and (3) strengthen legal protections.

Increase Financial Assistance to Support Survivors’ Access to Permanent Housing

- Increase the value of rental assistance and amend restrictive eligibility requirements: Current rental assistance falls short of need and has not kept pace with the cost of housing in New York. Maximum monthly rent levels must be increased to provide survivors with meaningful access to subsidized housing across the city. State legislation proposed by Assemblymember Andrew Hevesi and Senator Liz Krueger would create a new statewide rent supplement, Home Stability Support, that would fund the difference between the shelter allowance and 85 percent of the Fair Market Rent, while allowing localities to fund up to 100 percent. Survivors of domestic violence who are homeless or at risk of losing their housing would be eligible for assistance.In addition to increasing the value of rental assistance, the City should consider ways in which to support more equitable access to vouchers so survivors do not have to go through a particular “City door” to qualify. For example, amending City regulations regarding initial eligibility for CityFHEPS to include those who previously resided in an HRA shelter and an additional category such as “households determined by the Commissioner to be at risk of homelessness and including a survivor of domestic violence” would ensure more survivors would be eligible for assistance prior to shelter entry (or reentry).[87] Additionally, the City should examine providing exceptions to the maximum rent toward which a voucher can be applied for survivors who can remain safely in their homes and whose rent is just outside the maximum allowed for their family size, thereby preventing the need for shelter.

- Create a Survivor Housing Stability Fund: The City should develop a dedicated fund similar to the District Alliance for Safe Housing’s Survivor Resilience Fund, which would be more flexible than the limited options for financial assistance currently available to survivors of domestic violence at risk of losing their housing. Survivors should be able to access the fund through referrals from trusted organizations in their communities and regardless of immigration status and income, in recognition of the fact that survivors are often subject to economic abuse and may not have immediate access to financial resources. Survivors could use the funds to cover expenses such as moving costs, medical bills, phone costs, children’s needs, or transportation, and to implement a safety plan, among other needs impacting their ability to stay stably housed.

- Increase availability of free and reduced-cost legal services for survivors: New York City passed historic “Universal Access to Counsel” legislation in 2017, paving the way for all income-eligible New Yorkers facing eviction in Housing Court to have access to free legal representation, and the number of families entering DHS shelter due to eviction has fallen. The City should take steps to make legal representation available to survivors facing eviction, regardless of zip code, before 2022. Additionally, the City should work with legal services organizations across the boroughs to evaluate the unmet need for free or reduced-cost legal assistance for survivors in matters beyond housing, as court proceedings are often necessary for survivors to disentangle from abusive relationships but can come with significant financial costs. The City Council has, for example, introduced a bill that would provide full legal representation to victims of domestic violence in divorce proceedings.[88]

- Expand the capacity of Family Justice Centers, particularly in high-need neighborhoods: The City’s five Family Justice Centers have become invaluable resources for survivors across the city, but given the enormous need and the fact that survivors often need access to help quickly, the City should consider investing funding needed to expand service hours, including to weekends, and to create additional centers in neighborhoods where incidences of domestic violence are high. While these centers would not provide the benefit of being co-located with the district attorneys’ offices, they would offer many survivors closer proximity to services in their communities and may encourage survivors to come forward who do not utilize the FJCs now. The neighborhoods where families resided prior to entering shelter, as outlined in this report, should be considered as possible sites.

- Build more affordable housing for households with very low incomes and increase set-aside for New Yorkers experiencing homelessness: The Comptroller’s Office has previously raised serious concerns about the City’s current housing plan—namely, that it does not direct resources to the households with the greatest need.[89] If New York City is to truly invest in solutions to reduce homelessness, including for those impacted by domestic violence, new construction units should be targeted to households with extremely and very low incomes, and the City must increase the number of units dedicated and set aside for people experiencing homelessness, both among new construction and preservation units.

Expand Residential and Non-Residential Services

- Increase the capacity of the HRA domestic violence shelter system and end the practice of placing survivors in hotels: Emergency shelter is a critical component of the City’s response to domestic violence, and the City must ensure there is adequate capacity for those who need the confidentiality and security that these facilities provide. The City should add additional DV shelter beds to the existing capacity to ensure more equitable access, and in doing so, work with the State to expand access to those who may currently be denied a placement. The DV system was developed largely with (cisgender) women-headed families with children in mind, and there is a shortage of beds for single adults, in part because the per-person reimbursement rate structure creates a financial penalty for downsizing family rooms.[90] This especially harms LGBQ and TGNC individuals, who already experience disproportionately high rates of violence.[91] In addition, given all of the challenges that survivors within the domestic violence shelter system face, and the dearth of affordable housing, 180 days is simply not a realistic timeline for all survivors to obtain permanent housing, whether subsidized or unsubsidized. The City should be making every effort to minimize moves and disruptions for families and should therefore also work with the State to allow extensions beyond the current 180-day limit on a case-by-case basis as more DV beds come online.Meanwhile, as the City works to phase out the use of hotels, DHS should stop placing families entering shelter due to domestic violence in hotels, which offer among the least protective and supportive environments for this vulnerable population. The City should aim for no one to be discharged from a DV shelter to a homeless shelter, but to the extent that survivors, including those who are not eligible for DV shelter, do seek temporary housing from DHS, they should not be placed in hotels unless no other safe location in the city can be identified.

- Ensure every domestic violence shelter has dedicated housing specialists: Providers of domestic violence shelter are required, per State regulations, to make assistance in obtaining housing available to residents.[92] However, domestic violence shelters are not mandated to have dedicated staff to support survivors with the challenging processes of navigating applications for housing assistance or identifying qualifying apartments. The City should evaluate how many shelters have housing specialists now and what additional funding would be needed to ensure all residents have access to expert guidance in identifying and securing safe, permanent housing. All housing specialists should be trained in how to appropriately address and direct cases of source of income discrimination.

- Expand access to mental health support and increase the supply of supportive housing for survivors of domestic violence: A significant number of survivors enter the domestic violence shelter system with conditions that require clinical attention. Many also leave with those conditions. The de Blasio administration has committed to building 15,000 new supportive housing units over 15 years; however, as this report shows, very few survivors in shelter receive placements in permanent supportive housing. Survivors of domestic violence who have a need for more intensive mental health support should have greater access to these units. The City should also ensure that survivors who leave the DHS and DV shelter systems and move to permanent housing, whether subsidized or unsubsidized, continue to have access to free or reduced-cost trauma-informed care.

Strengthen Legal Protections for Survivors

- Fix early lease termination law: Strong housing protections should be foundational to homeless prevention. Yet, New York has among the most restrictive early lease termination laws in the country, leaving few survivors with practical access to this vital protection. State legislation introduced by Senator Alessandra Biaggi and Assemblymember Andrew Hevesi and passed by both the Senate and Assembly in 2019 would address current gaps, including eliminating the requirement that survivors obtain a court order, dropping the requirement that survivors give advance notice to a co-tenant who is the abuser, and ensuring survivors do not need to be current on rent at the time that the request to terminate a lease is made.[93] The governor should move expeditiously to sign the bill, and the State should ensure appropriate steps are taken to educate tenants and landlords about the pending changes to the law. Additionally, the Comptroller’s Office recommends that New York City work with the State and the courts to understand how much is outstanding in rental arrears for survivors penalized under the existing early lease termination law and consider possible pathways for paying or forgiving the remaining debt.

- Expand and aggressively enforce anti-discrimination protections: Following the lead of Oregon, New York City should build on the strong framework of the City’s Human Rights Law and prohibit any landlord or broker from terminating a lease or refusing to rent to a tenant or applicant solely on the basis of criminal history stemming from their experience as a survivor of domestic violence. Similarly, given that many survivors would have a healthy credit score but for economic abuse they were forced to endure, New York City should examine viable paths for prohibiting discrimination in housing based on a low credit score that is a direct consequence of domestic violence. At a minimum, the City should invest more resources to educate landlords about best practices in screening prospective tenants who have experienced domestic violence and ensure existing anti-discrimination protections, including those against source of income discrimination, are vigorously enforced.

- Strengthen lock-change policy and include protections in lease agreements: While tenants in New York have a right to install a separate lock on the entrance to their unit, existing statutes could be strengthened by adding protections specifically for survivors of domestic violence. Following the lead of California, and to ensure locks are changed as quickly as possible, landlords should be required to change locks within 24 hours of a request. In addition, tenants should be allowed time to reimburse landlords for expenses associated with the lock change, as is the case in the District of Columbia. In order to ensure that tenants are aware of their right to change the locks to their residence, information regarding survivors’ right to new locks should be clearly outlined and included in all leases executed in the city.

- Provide protections against termination of utility service: New York should allow for the continuation or restoration of utility service for survivors who are fleeing an abusive living situation or who remain on a lease following the termination of a co-tenant who was their abuser, and survivors should not be required to provide full or partial payment of arrears before service is restored. Additionally, security deposits, late payment charges, and any fees associated with reconnecting service should be waived for survivors.[94] Utility companies should be required to provide training on domestic violence to employees who respond to inquiries from customers, such as those working in call centers, and have a designated point of contact to resolve issues stemming from domestic violence.

Conclusion

New York City has taken significant steps over the last several years to address the needs of the growing population of survivors and family members who are experiencing homelessness but has not yet been able to turn the rising number of shelter entries in the other direction. Indeed, domestic violence is now by far the largest driver of homelessness among families in the city. Meanwhile, an untold number of survivors continue to navigate violence outside of the system, trying to determine how to hold on to their housing and avoiding shelter as a last resort.

While there will always be a need for secure, confidential domestic violence shelters for New Yorkers in imminent danger, survivors of domestic violence who need to access emergency shelter, for any period of time, should not be forced to exit that facility to homelessness. The City can and must do more to ensure survivors have access to safe, affordable permanent housing.

Because there are many reasons why survivors experience homelessness, and an intervention that works for one family may not for another, the City must adopt a multi-pronged, survivor-centered approach. Survivors who can remain safely in their homes or relocate should be provided the tools to do so, including fast and flexible grants; survivors in shelter should have access to housing subsidies and any wraparound supports they identify as they prepare to exit, including trauma-informed care; and those with a need for longer-term care, either in a transitional DV shelter or in permanent supportive housing, should have those options. Implementing the recommendations outlined in this report—from expanding the capacity of the DV shelter system to identifying opportunities to codify stronger housing protections to increasing access to low-barrier financial assistance, legal services, and permanent affordable housing units—will require new public investments in the short-term. But together, they can be expected to cost less than a shelter stay, reduce trauma, and ensure more families and individuals impacted by domestic violence are able to gain the safety and housing stability they deserve.

Methodology

The Comptroller’s Office used case-level data from the New York City Department of Social Services for families with children (families with at least one child under age 18) and adult families (families with all members age 18 or above) who entered Department of Homeless Services (DHS) shelters or Human Resources Administration domestic violence shelters for the period between July 1, 2013 and June 30, 2018 (fiscal year 2014 through fiscal year 2018). Data include a unique anonymized case identifier, dates of entry and exit to and from shelter, shelter type, eligibility reason (DHS shelter only), and exit reason from shelter, as well as demographic information of family members entering the shelter.

There are more than one spell of stays for some families and families can move between the two shelter systems. Unique case identifiers allow the Comptroller’s Office to track families who enter and exit different shelter systems over the time period. In order to prevent double counting of families (and their characteristics), the analysis includes the first shelter entry (by shelter type) over each fiscal year. Families who move back to the same shelter system within 30 days are not included in the exit counts. Finally, cases found eligible as “immediate returns” are not included in the analysis as these are families who were already previously found eligible for shelter and reapplied within ten days of prior shelter exit.

Families may become homeless for more than one reason. This analysis employs the primary reason for eligibility as determined by DHS. Eligibility reasons in the “other reasons” category include crime situation; lockout (when landlord or primary tenant changed locks without going through a formal eviction process and attempts by DHS staff to facilitate restoration were unsuccessful); and financial strain.

Acknowledgements

Comptroller Scott M. Stringer thanks Alyson Silkowski, Associate Policy Director and the lead author of this report, and Selcuk Eren, Senior Economist. The Comptroller also extends his thanks to David Saltonstall, Assistant Comptroller for Policy; Preston Niblack, Deputy Comptroller for Budget; Angela Chen, Senior Website Developer and Graphic Designer; Nichols Silbersack, Deputy Policy Director; and Dabney Brice, Policy and Research Intern.

Endnotes

[1] New York City Human Resources Administration, “Legal Services for Tenants, Universal Access to Legal Services,” https://www1.nyc.gov/site/hra/help/legal-services-for-tenants.page.

[2] City of New York, “De Blasio Administration Announces Paid Safe Leave Law Now in Effect” (May 7, 2018), https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/239-18/de-blasio-administration-annouces-paid-safe-leave-law-now-effect.

[3] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Family and Youth Services Bureau, “Domestic Violence and Homelessness: Statistics (2016),” https://www.acf.hhs.gov/fysb/resource/dv-homelessness-stats-2016.

[4] New York City Department of Homeless Services, “DHS Data Dashboard – Fiscal Year 2018,” https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/dhs/downloads/pdf/dashboard/FY2018-DHS-Data-Dashboard-revised-1’30’2019.pdf.