Insecurity Deposits: A Plan to Reduce High Entry Costs for NYC Tenants

Introduction

Each year, thousands arrive in the five boroughs to find a job, to enroll in college, to reunite with family, or to simply “make it” in New York. For all of these new arrivals, plus thousands of additional New Yorkers already here, searching for a new apartment is a necessary, often painful process, whether it is matter of choice due to changes in family, school, or employment, or a matter of necessity driven by eviction, harassment or other, more dire circumstances.

Regardless of the context, these moves are becoming increasingly unaffordable and untenable as rents surge across the five boroughs. More and more people are being shut out of the city or left to remain in undesirable living arrangements, lacking not only the salary to pay the rent, but also the savings to cover the security deposit. And while much-needed attention and resources have been devoted to helping New Yorkers remain in their apartments and fend off displacement, the barriers to entering the city’s rental market or moving within the five boroughs, are equally troubling.

To better understand this challenge, this brief from New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer documents the role that security deposits play in the city’s housing market and outlines reforms that would help renters more easily afford to live in the five boroughs.

Security Deposits in the New York City Housing Market

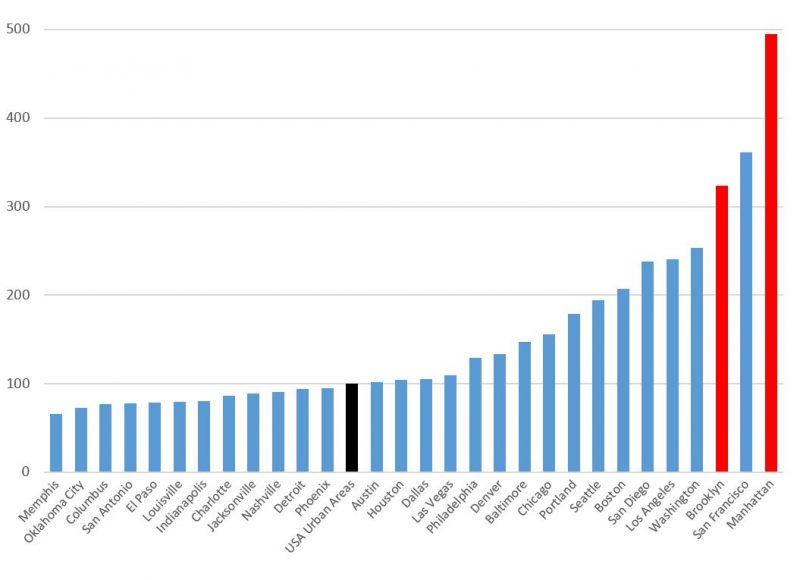

The five boroughs are among the most expensive and inaccessible housing markets in the country. In 2017, housing costs in Manhattan were five times higher than the typical American city and more than double peer metros like Boston, Los Angeles, Seattle, and Washington D.C. Brooklyn, meanwhile, is three times as costly as the national average, with housing expenses exceeding all but Manhattan and San Francisco (see Chart 1).[1]

Chart 1: Cost of Housing Index, 30 Largest American Cities, 2017

The Center for Community and Economic Research. “ACCRA Cost of Living Index.” January 2018.

Less well documented—but equally troubling—is the low savings rate among New York City residents. Only 46 percent of New Yorkers saved for an “unexpected expense or emergency” within the last year, the lowest rate among America’s largest cities. This compares to a far healthier 64 percent in Phoenix and 57 percent in Chicago and San Francisco (see Chart 2).[3] For those with little in the way of savings, covering the security deposit and first month’s rent of a costly New York City apartment is a daunting task.

Chart 2: Percentage of residents who saved for “unexpected expenses or emergencies” in the last year

FDIC. “2015 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.” October 2016.

These savings rates are even lower among select populations. Looking across the New York City metro area, only 41 percent of Hispanic families, 40 percent of black families, and 35 percent of households earning less than $50,000 per year saved within the past twelve months. Nearly 19 percent of Black and Hispanic families, meanwhile, do not even have a bank account.

With minimal savings and rising rents, the upfront costs of a security deposit—along with fees for credit reports and background checks—can make moving to or within New York City a challenge, particularly for low-income and residents of color. These barriers to entry help explain why fewer people are moving to New York City from other parts of the country, a growing number are exiting for the suburbs, and far too many New Yorkers are stuck in undesirable living situations.[4]

The median advertised monthly rent of a New York City apartment is $2,695.[5] Assuming a security deposit equal to first month’s rent, the typical family of four would have to pay six percent of their annual income to cover the upfront costs of moving in.

In a number of community districts, that ratio can be twice as high, particularly for those looking to remain in their neighborhood and stay close to friends and family.

In fifteen community districts, the typical household would pay more than 10 percent of their annual income to afford the first month’s rent and security deposit of a local apartment (see Chart 3). A household in Hunts Point, for instance, would have to fork over an extraordinary 16 percent of their income just to cover basic upfront costs for an area apartment. Needless to say, very few New Yorkers have the savings to cover such a large sum.

Chart 3: The high barriers to moving within the community district

| Community District | Borough | District Number | Median Household Income | Median Neighborhood Advertised Rent | First Month’s Rent + Security Deposit, Share of Median Income |

| Hunts Point, Longwood & Melrose | Bronx | 1 & 2 | $23,131 | $1,825 | 15.8% |

| Brownsville & Ocean Hill | Brooklyn | 16 | $28,315 | $2,150 | 15.2% |

| East Harlem | Manhattan | 11 | $31,628 | $2,400 | 15.2% |

| Belmont, Crotona Park East & East Tremont | Bronx | 3 & 6 | $23,710 | $1,725 | 14.6% |

| Chinatown & Lower East Side | Manhattan | 3 | $42,223 | $3,000 | 14.2% |

| Morris Heights, Fordham South & Mount Hope | Bronx | 5 | $24,436 | $1,600 | 13.1% |

| Concourse, Highbridge & Mount Eden | Bronx | 4 | $27,102 | $1,650 | 12.2% |

| Bushwick | Brooklyn | 4 | $42,197 | $2,525 | 12.0% |

| Bedford-Stuyvesant | Brooklyn | 3 | $40,537 | $2,400 | 11.8% |

| Central Harlem | Manhattan | 10 | $40,816 | $2,350 | 11.5% |

| Brighton Beach & Coney Island | Brooklyn | 13 | $34,979 | $1,995 | 11.4% |

| Hamilton Heights, Manhattanville & West Harlem | Manhattan | 9 | $45,765 | $2,600 | 11.4% |

| East New York & Starrett City | Brooklyn | 5 | $36,385 | $2,000 | 11.0% |

| Crown Heights North & Prospect Heights | Brooklyn | 8 | $45,503 | $2,499 | 11.0% |

| Greenpoint & Williamsburg | Brooklyn | 1 | $59,577 | $2,975 | 10.0% |

Median Household Income: NYC Department of Planning. “New York City Population FactFinder,” 2018.

Median Rent, Asking: NYU Furman Center. “State of New York City’s Housing and Neighborhoods.” May 2018.

Of course, not everyone wishes to stay in their current neighborhood. As economists like Raj Chetty have demonstrated, one’s life prospects are very much tied to geography, with many low-income neighborhoods failing to offer the employment, educational, and healthy-living opportunities critical for economic prosperity.[6] In cities like New York, the difference between growing up in two adjacent neighborhoods—or even two adjacent blocks—can be monumental.

Unfortunately, for many low-income New Yorkers, moving to a neighborhood with better employment and educational opportunities can be next to impossible. Indeed, the median advertised rent of a New York apartment ($2,695) plus an equivalent security deposit would eat up over 22 percent of annual household income for the typical family in the city’s ten poorest neighborhoods (see Chart 4). These insurmountable barriers to entry are part of why poverty is so concentrated in the five boroughs.[7] For New York’s low-income families, there are just a handful of neighborhoods where they can possibly afford to live.

Chart 4: The high barriers to moving outside of the neighborhood

| Neighborhood | Median Household Income | Median Advertised Rent + Equivalent Security Deposit, NYC Apartment | Share of Household Income |

| Claremont-Bathgate | $21,369 | $5,390 | 25% |

| Mott Haven-Port Morris | $21,469 | $5,390 | 25% |

| East Tremont | $22,130 | $5,390 | 24% |

| Crotona Park East | $22,538 | $5,390 | 24% |

| Hunts Point | $22,679 | $5,390 | 24% |

| University Heights-Morris Heights | $22,776 | $5,390 | 24% |

| Williamsburg | $23,188 | $5,390 | 23% |

| Fordham South | $23,992 | $5,390 | 22% |

| Brownsville | $24,504 | $5,390 | 22% |

| Starrett City | $24,601 | $5,390 | 22% |

Median Household Income: NYC Department of Planning. “New York City Population FactFinder,” 2018.

Median Rent, Asking: NYU Furman Center. “State of New York City’s Housing and Neighborhoods.” May 2018.

But the security deposit is not just a significant upfront cost, it is also a hold on one’s savings. These deposits are locked into low-interest or no-interest accounts, off-limits for unexpected expenses and emergencies. This arrangement leaves billions of dollars tied up and detained throughout New York City—money that could be spent or invested more wisely elsewhere.

In 2016, approximately 300,000 households moved into a new apartment, including 99,000 in Manhattan and 92,000 in Brooklyn (see Chart 5). The average new renter paid $1,690 in rent, meaning that New Yorkers forked over approximately $507 million in security deposits over the course of the year—based on the assumption that security deposits are equal to one month’s rent. Nearly $216 million was retained in deposits in Manhattan, $146 million in Brooklyn, $87 million in Queens, and $49 million in the Bronx in 2016.

Chart 5: The amount paid for security deposits by new renters in 2016

| Borough | Households in

New Apartments |

Average Monthly Rent for New Apartment Holders | Approximate Amount Held in Security Deposits |

| Bronx | 43,324 | $1,131 | $49,002,900 |

| Brooklyn | 92,020 | $1,586 | $145,925,434 |

| Manhattan | 99,462 | $2,176 | $216,444,256 |

| Queens | 57,672 | $1,503 | $86,707,446 |

| Staten Island | 7,544 | $1,182 | $8,915,461 |

| New York City | 300,022 | $1,690 | $506,995,497 |

United States Census. “American Community Survey: 2012-2016 Five Year Sample.”

And while one month’s rent is certainly standard practice for security deposits in New York City, policies will vary from renter to renter. Low-income New Yorkers who are not in rent-regulated apartments, for instance, can be subject to a much higher rate, particularly those deemed “high-risk” due to a low credit score. For these low-wage renters, a security deposit of two or three times the monthly rent is not uncommon—further evidence that it can be “expensive” to be poor.[8]

Recommendations for Reform

Recommendation #1: Capping Security Deposits at One Month’s Rent. To ensure that recent college graduates, immigrants, seniors, and lower-wage New Yorkers are not unduly punished and locked-out of the rental market, New York State should cap security deposits at one month’s rent for all one-year leases, as Alabama, North Dakota, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Kansas, Nebraska, Rhode Island, Delaware, and Hawaii have already done.[9] Security deposits are already capped for rent-regulated units in New York; this proposal would simply expand that ceiling to all units within the city.

Recommendation #2: Reducing Upfront Costs and Expanding Tenant Choices. While it is essential that landlords have protection against damages and unpaid rent, an upfront deposit is not the only way this can be achieved. City and State legislators should empower tenants to manage their security deposit obligations with a range of opt-in strategies, including:

- Payment plans: Tenants should have the option to pay security deposits in installments rather than covering the full burden all at once. In Seattle, for instance, renters are allowed to pay in six installments, so that a tenant could add $300 to their first six rental payments, rather than paying $1,800 up-front.

- Security insurance rather than security deposits: A number of New York companies allow renters to pay a small monthly or one-time fee in exchange for guaranteeing their security deposit with landlords. While tenants will not receive this money back—as they would with a traditional deposit—paying $10 per month to insure your apartment against damages rather than an $1,800 security deposit is a significant reduction in the upfront costs of moving and can be a desirable trade-off.

- One month’s rent: If a tenant prefers to pay a full month’s security deposit with a single check, that option will be preserved and protected.

Recommendation #3: Getting back the security deposit. Too often, security deposits are withheld from tenants at the end of a lease for arbitrary, unexplained, or fraudulent reasons. To combat bad actors and ensure fairer outcomes, New York City can follow the lead of the United Kingdom and create a tenant protection system where security deposits are held by a third-party custodian and arbiter rather than the landlord.[10]

Under this model, if a landlord wishes to withhold money for damages, cleaning fees, or unpaid rent at the end of a lease, that landlord must come to an agreement with the tenant. In instances where there is a dispute over damages or the cost of repairs, the landlord and tenant can utilize the dispute resolution service offered by the third-party organizations that hold deposits. These services are free but require both parties to agree to be bound by the decision.

Conclusion

Whether through the private sector, nonprofits, or legislation, it is clear that new approaches and innovations are essential for assisting New York renters. As housing prices skyrocket and security deposits mount, the city’s affordability crisis has become increasingly untenable. While there are many avenues to address this crisis, up front move-in costs are a smart—and appropriate—place to start.

Acknowledgements

Comptroller Scott M. Stringer thanks Adam Forman, Chief Policy & Data Officer and the lead author of this report. He also recognizes the important contributions made by David Saltonstall, Assistant Comptroller for Policy; Zachary Schechter-Steinberg, Deputy Policy Director; Preston Niblack, Deputy Comptroller for Budget; Brian Cook, Assistant Comptroller for Economic Development; Angela Chen, Senior Web Developer and Graphic Designer; Edith Mauro, Web Developer and Graphic Design Intern; Frank Giancamilli, Director of Communications; Ilana Maier, Press Secretary; and Tian Weinberg, Press Officer.

Endnotes

[1] The Center for Community and Economic Research. “ACCRA Cost of Living Index.” January 2018.

Note: The number for Los Angeles includes the combined Los Angeles and Long Beach housing market.

[2] The profiles presented here are composites intended to highlight how security deposits can impact different groups. They are not real people.

[3] FDIC. “2015 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.” October 2016.

[4] United States Census Bureau. “County Population Totals and Components of Change: 2010-2017.” April 2018.

[5] NYU Furman Center. “State of New York City’s Housing & Neighborhoods,” 2017.

“Median Rent, Asking” is an aggregate of all rents advertised on StreetEasy, as calculated by the Furman Center.

[6] Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence F. Katz. “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment,” American Economic Review 106, no. 4: 855-902. 2016.

[7] Wolf, Courtney. “Concentrated Poverty In New York City: An Analysis Of The Changing Geographic Patterns Of Poverty,” Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York. April 2012.

[8] Office of the Comptroller. “Make Rent Count,” October 2017.

[9] Balint, Nadia. “Which States Have the Best and Worst Laws for Renters?” RentCafe. March 14, 2018.

[10] United Kingdom Government. “Tenancy Deposit Protection.” https://www.gov.uk/tenancy-deposit-protection