Executive Summary

How do you address the challenges of a public school system with just under one million students across over fifteen hundred schools, where some schools face severe overcrowding and large class sizes, others are caught in a cycle of declining enrollment and resources, and the entire system is highly segregated and unequal?

This question has long required real-world answers, and it is especially relevant at the current moment due to changes to the New York State Education Law (“the class size law”) capping class sizes for public schools in New York City. Solutions to ensure compliance with the new class size limits are complex and consequential. The mandate will impact individual school budgets, school construction, staffing of teachers and other school-based professionals, individual school operations and programming decisions, and enrollment — with attendant implications for equity in the distribution of resources needed.

While many schools are burdened with overcrowding and large class sizes, there are also underutilized schools located in communities with a history of disinvestment, struggling with a myriad of issues exacerbated by a lack of resources and segregation. The juxtaposition of over vs. under-utilized schools demands further attention if New York City is to approach the implementation of the class size law effectively and equitably.

This report showcases an evidence-based approach for one viable, potentially cost-effective solution for compliance with the class size mandates that centers diversity, equity, and excellence for all students: intentional and inclusive school mergers. Given the high cost of new school construction, consolidation of schools to better utilize existing school buildings is likely to be among the proposals to reduce class sizes — but it must be rooted in equity and prioritize “Real Integration”[i] rather than inequity and gentrification.

This report highlights a successful local example: the intentional integration of two previously segregated District 13 schools into Arts and Letters 305 United (“United”). The exploration of United’s community processes, their challenges, and how they overcame them showcases school mergers as a viable solution to reducing class size and promoting equity and integration in New York City schools.

United also demonstrates that school consolidation can serve as a cost-efficient means of meeting the new class size caps, while driving greater financial stability and integration in schools. This report, authored in partnership by New York Appleseed and the New York City Comptroller’s Office, couples citywide data analysis with a case study of United interviewing more than 30 parents, staff and students about the merger process to inform the recommendations presented here.

Findings

Citywide trends in class size & enrollment

- Sixty-one percent of New York City classrooms currently do not meet the class size law mandates. With an estimated per seat construction cost of $180,000, meeting the class size mandate will likely require significant operating and capital expenditures.

- Despite the high percentage of classrooms over the new class size cap, public school enrollment in New York City is in decline due to the rising lack of affordability, immigration and outmigration, changes in birth rates, charter schools, and the pandemic.

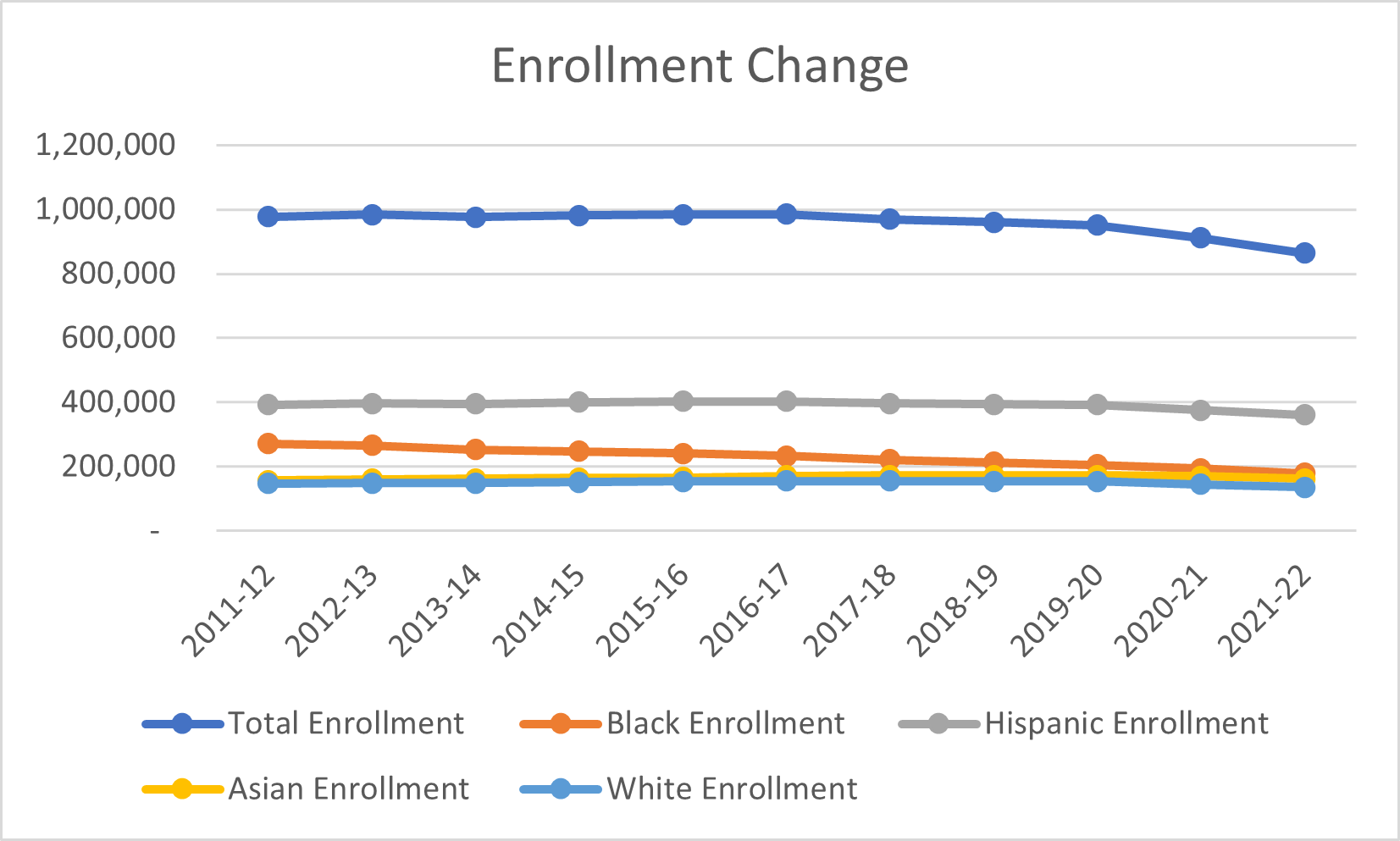

- Between 2012 and 2022, public school enrollment in New York City declined by 12 percent.

- Districts in Northern Manhattan and Central Brooklyn have seen the greatest drops in enrollment with ten-year declines of over 30 percent.

- The School Construction Authority (SCA) forecasts another 22 percent drop in enrollment over the next decade—even taking into account immigration.

- Enrollment declines are particularly acute among Black students.

- Between 2012 and 2022, Black students enrolled in New York City public schools declined by 32 percent.

- The population of Black students declined in every district of the City between 2012 and 2022 with declines of 45 percent or greater in districts in Central and Southeastern Brooklyn and Northern Manhattan.

- This enrollment decline has driven down school utilization rates in historically Black neighborhoods, contributing to smaller class sizes (and higher rates of compliance with the new class size caps) in those neighborhoods, but raising concerns about the financial sustainability of those schools.

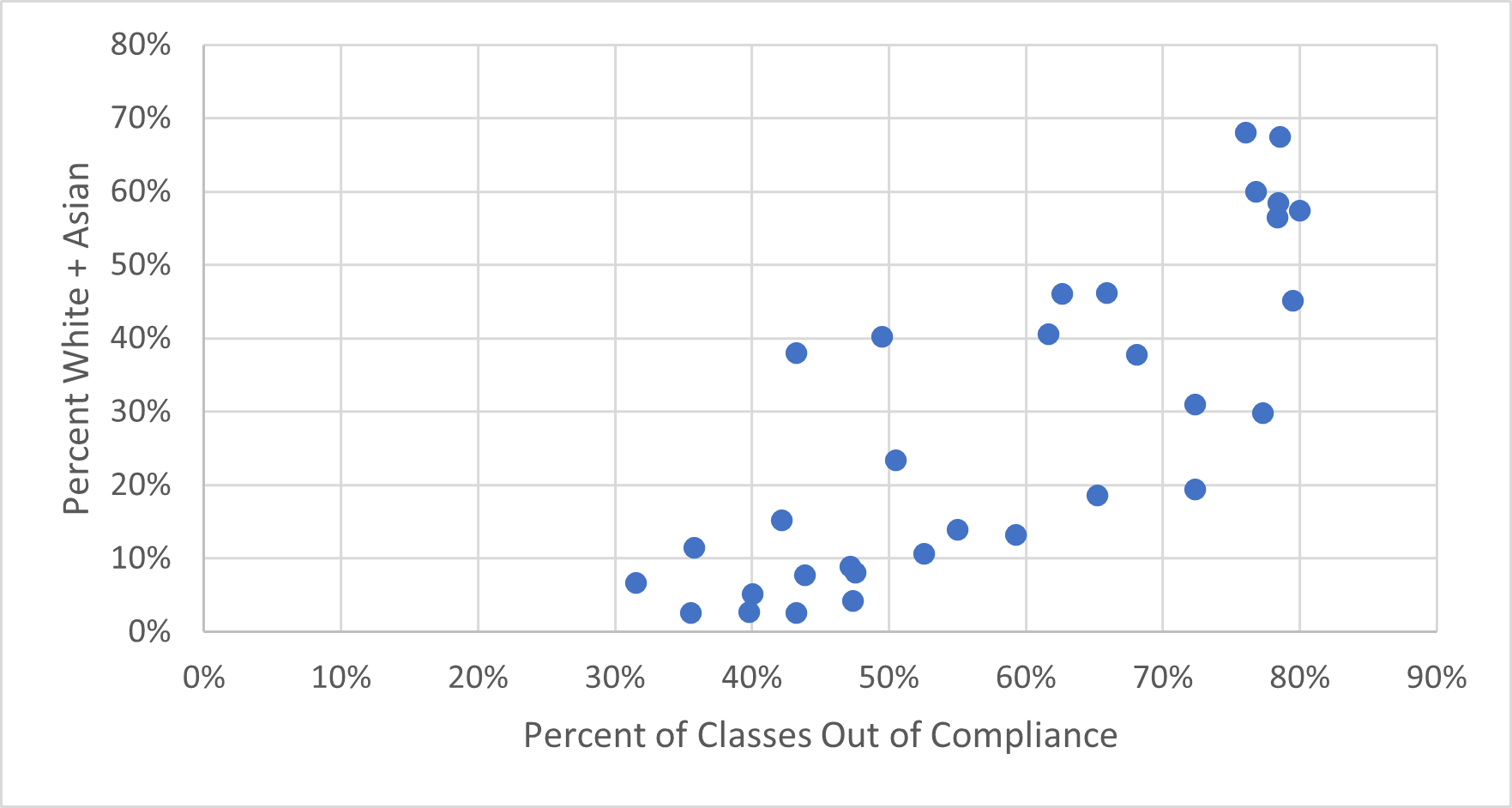

- Districts with the lowest percent of classrooms out of compliance with the new class size caps (i.e. smaller classrooms) have relatively large populations of Black and Hispanic students compared to citywide averages.

- Conversely, districts with the highest percent of classrooms out of compliance with the class size law (i.e. larger classrooms) are in districts with populations of white and Asian students greater than the citywide average.

- School mergers, particularly in schools serving largely Black and brown students, have been increasingly deployed by the DOE to address declining enrollment and financial strain, resulting in economies of scale and an increase in total funding for the merged school given the increase in students enrolled.

- With 70 percent of New York City public schools intensely segregated, the demographics of over- and under-utilized schools have created actionable opportunities in New York City to utilize mergers to reduce cost, improve school financial viability, and foster greater school integration.

- Geographic, utilization, and demographic analysis of public schools citywide identified several opportunities to merge neighboring or nearby schools to meet the class size mandate and foster a more integrated school community.

Challenges & key questions to consider in school mergers

School mergers are complicated and can be highly contentious. Parents and students in schools with declining enrollment and resources, particularly in communities of color, often have good reason for significant distrust. Intentional and inclusive mergers that promote integration can provide opportunity — but also face challenges as disparate school communities combine. Interviews with United students, parents, and teachers as well as analysis of segregation, school utilization, class size and demographic data revealed the following challenges and key questions to consider in school merger processes:

- Three distinct challenges were evident in conversations with students, families, and staff:

- Developing trust and providing transparency;

- Addressing the racial and socioeconomic dynamics of power;

- Engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Key trends that arose from interviewees’ responses when asked about their thoughts, feelings, and observations of the post-merger process.

- How do you bridge two separate and distinct school cultures equitably?

- What spaces must be created for parents, students, and staff to build relationships across difference substantively and effectively?

- How can students be best supported in adapting to two major changes, one being a new school, and another being hybrid learning?

Recommendations

Citywide recommendations to DOE Central

- Identify opportunities for school mergers to attain compliance with class size mandates, increase opportunity for school integration, eliminate the presence of harmful barriers in schools, and improve outcomes for students. Those opportunities should:

- Reduce dissimilarity within the district;

- Reduce racial and socioeconomic isolation in the school district;

- Limit academic stratification and close the opportunity gap taking into consideration the range of opportunities and academic ability present at both schools;

- Ensure under-enrolled and under-resourced schools gain greater access to resources;

- Support overcrowded schools in meeting the new class size mandates; and

- Provide the means to thoughtfully identify, track, and improve student outcomes post-merger.

- Create new opportunities for school consolidation through the exploration of new models of innovation and school redesign, including but not limited to:

- Reorganize grade bands between schools to create an upper (grades 3-5) and lower campus (grades PreK-2), in order to broaden school catchment areas for enrollment purposes, and maximizing age-appropriate programs, services, and resources. This strategy can be especially relevant to mergers where the schools are proximally located but neither of the school buildings can accommodate the merged population of students.

- Eliminate exclusionary admissions methods such as middle school screens and segregated gifted and talented programs that may impede a successful merger of two schools.

- The State must repeal the requirement that New York City pay the leases for Charter Schools. In the meantime, the City must provide evidence that charter school co-location utilization proposals do not impede the ability of co-located district schools or any school in the district to expand its footprint to meet the class size mandates.

- Facilitate coordination across siloed departments at DOE to effectively plan and execute school mergers in direct dialogue with school communities.

- Support school community engagement throughout merger processes by replicating previously successful engagement models and implementing past local laws meant to improve equitable outreach and facilitate feedback on diversity initiatives by:

- Facilitating an internal School Merger Working Group at DOE responsible for developing a citywide school merger process that prioritizes both equity and excellence, breaking down communication and work stream siloes between departments at DOE.

- Ensure compliance with Local Law 225 of 2019, which requires every district to establish diversity working groups by the end of 2024. These groups should be deployed to initiate school merger conversations, providing a responsive and stable community voice with which DOE leadership could directly engage.

Recommendations for successful mergers at individual schools

- Schools must continue to follow through with investments into the “Rs” of the Real Integration framework. The 5 Rs establish that truly integrated schools are those that (1) achieve Racial, ethnic, and economic diversity in composition, (2) appoint leadership Representative of this diversity, (3) facilitate Relationships across people of different backgrounds, (4) practice Restorative justice, and (5) share equitable access to Resources and opportunities.

- DOE’s Family and Community Engagement (FACE) department must provide and incentivize staff and faculty with community-building opportunities well in advance of the completed merger.

- DOE should fund and all staff and faculty should participate in culturally responsive professional development opportunities well-before and after the merger process.

- Schools must involve students and families in the merger planning process, clearly communicating school merger objectives and prioritizing transparency.

- Students and families must receive ongoing support from school and district leadership through the provision of spaces to engage in courageous conversations across community lines.

Background

School Integration in New York City

The class size law will affect how and where schools enroll students across New York City. As such, policies that inevitably alter student assignment policy have great potential to influence the state of integration across schools and districts. New York City remains one of the most segregated school systems in the country, particularly for Black students.[1] Almost all of the City’s public schools are predominantly nonwhite, and most are intensely segregated (70 percent).[2]

However, New York City has made some progress toward integration since 2010, due in part to incremental progress in changes in admissions policy and pushes from local leaders to invest in diversity initiatives. Between 2010 to 2018, the percent of schools with less than 1 percent white enrollment declined by more than 10 points to 17 percent.[3] Exclusionary admission methods at public middle school and high schools that were proven to exacerbate segregation across the City have been drastically reduced or eliminated.[4] Previously selective and in-demand middle and high schools saw significant shifts in access for students from low-income families and English Language Learners as a result of changes such as the elimination of middle-school screens and removing the use of discriminatory criteria such as state test scores and attendance.[5]

Investments into diversity initiatives have also shown budding success with funding support for both enrollment changes and the necessary programming to approach integration holistically. Half of New York City’s school districts have received either state or local funds specific for diversity planning with six districts completing participation in a three-year State grant receiving well-over $2 million dollars. At the City-level, there are now over 200 programs that participate in the DOE Diversity in Admissions program, three districts with longstanding diversity plans and just recently two districts already participating in district-wide diversity plans were awarded new federal funds to continue fostering diversity across their schools.[6]

While measuring systemwide progress in a school system as vast as New York City’s can be challenging, these numerous incremental wins toward more inclusive and integrated schools should not be ignored. These significant advancements have often relied on cooperation and leadership from DOE. As such, DOE should take advantage of the class size mandate to address the lowering of class size in tandem with opportunities to further integration in a system plagued by segregation.

New York City’s New Class Size Mandate

The benefits of smaller class sizes and the calls for reform to imbue such benefits in New York City public schools are not new. For decades, New York elected leaders, teacher unions, and advocacy organizations have called for a reduction in class sizes.[7]

In the aftermath of the 13-year Campaign for Fiscal Equity v. State of New York case, a New York state law was enacted in 2007. This law, seeking accountability and additional funds directed to the neediest school districts, introduced the Contracts for Excellence—a financing structure designed to target state funding above the baseline state aid to the neediest school districts to increase student time on task, support teacher development, introduce innovations to improve student achievement, and to reduce class size.[ii] Now, in 2024, more than a decade after New York City schools were compelled to address class size, the New York City Department of Education (DOE) has a specific mandate.

On May 30, 2022, New York State Senator John Liu introduced bill S9460, which amended the existing education law establishing the Contracts for Excellence program to “limit the number of students per classroom in New York City and prioritize schools serving populations with higher poverty levels.”[iii] New York Governor Kathy Hochul signed the bill into law on September 8, 2022, but delayed the bill’s implementation by one year.[8] The change to limit class sizes to 20 to 25 students will be implemented gradually over a five-year period beginning in 2023 and ending in September 2028.

The class size law requires the Contracts for Excellence to include a plan to reduce actual class sizes as set forth on the Table 1. The law provides that the plans must be developed in collaboration with the collective bargaining units representing teachers—the United Federation of Teachers (UFT)—and the principals—the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators of the City of New York (CSA)—and the Chancellor and the presidents of each bargaining unit must approve the plan.[9]

Table 1: Class Size Law Mandated Caps

| Grade | New Maximum | Existing Maximum |

| Kindergarten | 20 | 25 |

| Grades 1–3 | 20 | 32 |

| Grades 4–8 | 23 | 33 |

| High School | 25 | 34 |

Source: N.Y. Educ. Law § 211-d(b)(ii)(A)

Physical education and performing arts classes are limited to no more than forty students per class at all levels.[iv] Beginning in 2023, the law requires that an additional twenty percent of the classrooms in the city school district be in compliance each year, with full compliance achieved by 2028, the fifth year of implementation. The law also requires the class size reduction plan to “prioritize schools serving populations with higher poverty levels.”

Subject to approval by the Chancellor and the presidents of the collective bargaining units representing the teachers and the principals, the law creates exemptions in the following circumstances: (1) space; (2) over-enrolled students; (3) teaching license shortages in certain subjects such as English as a Second Language); (4) severe economic distress and for (5) elective and specialty classes.[v] In the event that the Chancellor and presidents of the collective bargaining units representing the teachers and the principals cannot reach agreement on an exemption after thirty days, the issue is to be determined by an arbitrator.[vi]

The law also requires that each city school district’s class size reduction plan “include the methods to be used to achieve the class size targets, such as the creation or construction of more classrooms and school buildings, the placement of more than one teacher in a classroom or methods to otherwise reduce the student to teacher ratio, but only as a temporary measure until more classrooms are made available in conformance with the plan.”[10]

Sixty-one percent of NYC public classrooms currently do not meet the class size law caps. The School Construction Authority has included $4.13 billion in their FY 2025-2029 Proposed Five Year Capital Plan for new capacity to provide targeted support to schools to comply with the class size mandate. Given an estimated construction cost of $180,000 per seat[vii], this funding is likely a minimum first step.

New school construction in New York City is also limited by the availability of building sites and the construction time frame which generally runs from 2-4 years. Even if every new seat capacity construction project needed to meet the class size mandate went into design today, all projects would likely not be completed by the 2028 deadline.

Overall, the class size law is a long overdue mandate to fulfill a forgotten promise that can benefit New York City public schools and its students long term, but school and classroom construction alone is not a viable path forward for compliance with the law. The high cost of school construction makes it critical for the City to explore solutions that better utilize existing school buildings, like school mergers and consolidation. Like many other education reforms, class size is not a silver bullet, and policies deployed must be multifaceted in their solutions to equitably reimagine the composition of New York City schools for the benefit of all its students.

The Mutual & Similar Benefits of Small Class Size and School Integration

A number of scholars and educational reform proponents have considered the relationship between school class size and integration. Many of the findings from scholars and studies alike find similar benefits as a result of both reforms. Integrated schools, through two decades of research, have been shown to not only result in academic gains but socio-emotional gains as well. Studies have shown integrated schools result in higher graduation rates, higher achievement in core subjects such as math, science and reading, and students are increasingly prepared for work in a multicultural diverse society.[11]

Reducing class sizes has yielded similar results, supporting claims that lower class sizes increase student achievement, especially for students of color. Studies examining arguably the largest experiment on classroom size reduction, the Tennessee Star Class Size Experiment in 1985 (“Project Star”)[12], generally found that reduced class sizes benefited students’ academic and socio-emotional achievement greatly, with a disproportionate benefit for Black students.[13] Another 2014 meta-analysis of class size reduction literature that examined over a hundred peer-reviewed studies revealed that the overwhelming majority found that smaller classes helped to narrow the achievement gap.[14]

Examining the mutual and similar benefits of both lowering class size and integration, it is easy to theorize how both work in tandem to strengthen their respective results. For example, smaller class sizes allow teachers to better foster relationships with and provide feedback to all students.[15] The ability to cultivate relationships across difference is a key tenet for integration. With smaller classes, teachers are arguably able to build these relationships by “deepen[ing] their interactions with students and meaningfully individualiz[ing] instruction.”[16]

Reduced class sizes also create conditions in which resources–another required tenet of integrated schools–are no longer stretched unbearably thin. With smaller class sizes, teachers can interact with individual students more frequently and have access to greater resources and instructional strategies. Student behavior may also improve as a result of the increase in physical classroom space per student, which provides more opportunities for student movement, different grouping strategies, and interaction among students and between students and teachers.[17]

While extensive research underscores the advantages of reducing class sizes, one aspect— the necessary hiring of new teachers—has been found to potentially diminish these benefits. This raises concerns particularly regarding school integration efforts. A study in California on the implementation of a twenty percent reduction in early education class sizes in 1996, from an average of 28.5 to 20 students, found that some of the positive effects of the class size reductions were counteracted by the lower qualifications of the new hires.[18] Another study of the California reduction found that the teacher quality of the new hires was lower at lower income schools and, in many cases, experienced teachers transferred to wealthier schools to fill the new openings as a result of the reduction. Lower income schools were thus forced to hire “inexperienced and uncertified teachers, with the result that one-quarter of the [B]lack students in high poverty schools had a first- or second-year teacher, and nearly 30 percent had a teacher who was not fully certified.”[19] A similar study in New York City arrived at similar results, noting the positive effects were predominantly isolated to the classes with existing teachers; students in classrooms with new teachers performed roughly the same as before the reductions.[20]

We note these studies not as a critique of fulfilling the mandates of the class size law, but rather to illustrate the consequences of haphazardly implemented policies. The class size law will affect the composition of many schools, and it is estimated that DOE will need to hire an additional 10,000-17,000 new teachers.[21] Finding an equitable manner in which to distribute new teachers, as well as implementing incentivization for placement of experienced teachers in difficult to staff, high-need schools are integral to reaping the benefits of smaller class sizes. It is also central to ensuring that staff and teacher diversity is cultivated and sustained through the reorganization of students and staff– a primary ingredient for real school integration.

In summary, much of the research on class size and school integration illuminates their respective benefits, yet cautions that poor policy, particularly in reduction of class size, can impede on progress for the other. The class size law opens a window for implementation of new and innovative policies that would not only reduce class size, but also dismantle segregation across New York City schools.

School Mergers

Reductions in class size and school integration can be achieved via many of the same mechanisms, including new construction and/or rezoning, admissions/enrollment modifications, and creative programming. In this report, school mergers are explored as a cost-effective mechanism to meet the class size mandate while simultaneously fostering strong, integrated school communities.

School mergers are a regular part of space and enrollment planning at DOE, considered on a case-by-case basis, and governed by Chancellor’s Regulation A-190.[22] The DOE Office of District Planning and Superintendent, with input from Community Education Council (CEC) members, administrators, staff, and parents at each of the schools develop a merger proposal which is the basis for an Educational Impact Statement (EIS). The EIS describes changes in enrollment, programming, transportation, and space utilization that will result from the merger. The EIS is then posted publicly and presented via a formal public engagement process that includes the opportunity for CECs to pass a resolution supporting or rejecting the proposed merger, a Joint Public Hearing, and a Panel for Educational Policy (PEP) meeting where the proposal is voted on by the PEP.

School mergers are complex and frequently controversial for the school communities involved. One major factor in their complexity is navigating the consequences of systemic racism that often lead school communities of color to consideration of a merger. Schools that are majority Black and brown with declining enrollment and resources are plagued by the results of unaddressed systemwide segregation. This type of academic redlining places the burden on communities of color, leaving them with few options in a merger when there are no viable alternatives to secure the support and investments their children rightfully deserve. In numerous PEP meetings, public comments from school communities facing a school merger often include administrators, teachers, students and families expressing a range of opinions, from approval to approval with conditions, to outright rejection. Those from schools facing major changes such as moving buildings often feel displaced from their traditional home. Sometimes only one school name is retained after the merger which can evoke feelings of loss. There can be differences in curriculum, teaching practice and school culture that are difficult to reconcile. And there are hard choices that must be made ultimately around post-merger school leadership– both administrative and parental. It is due to these many factors that careful, intentional engagement with all stakeholders is recommended to mitigate concerns and create a community-informed plan.

School mergers have become a frequent agenda item at PEP meetings over the past year as declining enrollment drives school consolidation, particularly in Black and brown communities throughout New York City. Recent school mergers in East New York and Brownsville in Brooklyn and in Upper Manhattan illustrate this trend.[23]

Analysis

Classrooms Out of Compliance with the New Class Size Law

As of the 2022-23 school year, only 39 percent of classrooms citywide were at or below the mandated class size caps, leaving 55,509 classrooms out of compliance with the new class size law. As seen in Table 2, an analysis of citywide class sizes across grade bands shows that grades 6-8 and 9-12 have the highest total number of classrooms over the new class size threshold. Grades K-3 and 6-8, however, have the highest portions of classrooms over the cap, at 67 percent and 69 percent, respectively.

Table 2: City Wide Class Size Compliance by Grade, 2022-23 School Year

| Citywide | Total number of classes | Total number of classes at or under thresholds | Total number of classes above thresholds | Total percent of classes above thresholds |

| K-3 | 9,279 | 3,092 | 6,187 | 67% |

| G4-5 | 4,457 | 1,993 | 2,464 | 55% |

| G6-8 | 29,049 | 9,021 | 20,028 | 69% |

| G9-12 | 47,572 | 20,742 | 26,830 | 56% |

| Total | 90,357 | 34,848 | 55,509 | 61% |

Source: New York City Department of Education

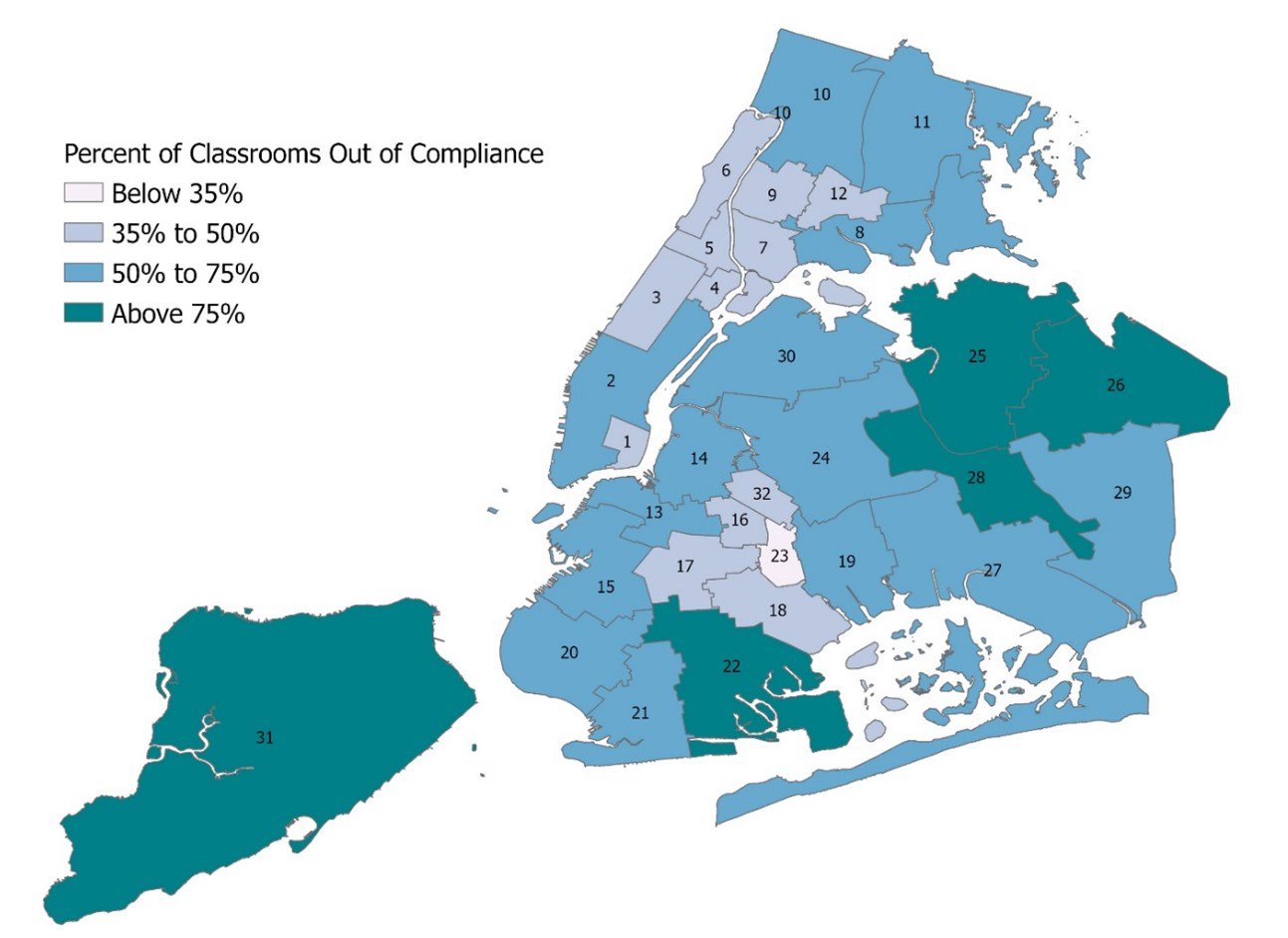

A borough specific analysis shows that Staten Island has the highest percentage of classrooms over compliance at 78 percent while Queens has the highest number of classrooms that are out of compliance at 18,289 classrooms. Brooklyn follows closely behind in the total number of classrooms over the cap, at 16,123.

Table 3: Class Size Compliance by Borough, 2022-23 School Year

| Borough | Staten Island | Queens | Brooklyn | Manhattan | Bronx |

| Total classes | 5,736 | 24,980 | 26,565 | 15,439 | 17,637 |

| Below caps | 1,285 | 6,691 | 10,442 | 7,530 | 8,900 |

| Percent under | 22% | 27% | 39% | 49% | 50% |

| Over caps | 4,451 | 18,289 | 16,123 | 7,909 | 8,737 |

| Percent over | 78% | 73% | 61% | 51% | 50% |

Source: New York City Department of Education

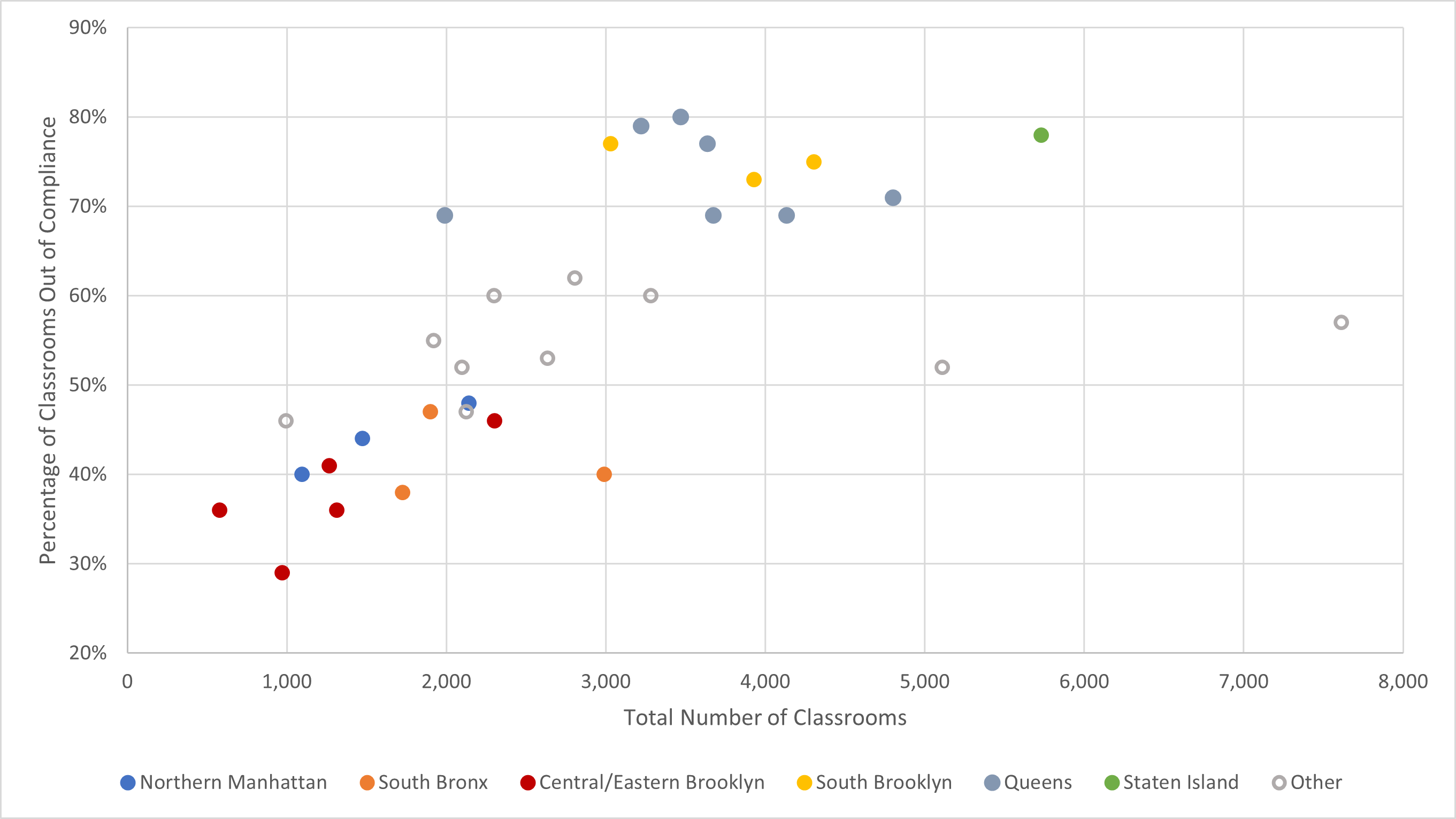

At the district level, there is a correlation between compliance with the class size caps and student demographics. As seen in Chart 1, districts with the highest percent of classrooms out of compliance with the class size law are in districts with populations of white and Asian students greater than the citywide average. As Map 1 and the data in Chart 2 show, six of the top ten districts over the class size caps are located in Queens; the others are Staten Island and South Brooklyn. Districts with the fewest classes out of compliance have relatively large populations of Black and Hispanic students including districts in Central and Eastern Brooklyn and the South Bronx.

Chart 1: Demographic Analysis of Class Size Compliance: Districts with Larger than Average White and Asian Students, 2022-23 School Year

Source: New York City Department of Education

Map 1: Class Size Compliance by District, 2022-23 School Year

Source: New York City Department of Education

The data in Chart 2 also illustrate the strong correlation between enrollment and compliance with the class size caps at the district level. Districts with more students, and therefore more classrooms, are less compliant. Districts with fewer students and fewer classrooms have more classrooms that meet the caps. The 11 districts with classrooms least likely to be in compliance with class size caps (larger classrooms) average 3,813 classrooms per district. The 11 districts with the highest rates of compliance (smaller classes) have an average of 1,512 classrooms per district—60 percent fewer classrooms. This disparity highlights differences in enrollment as well as the disproportionate impact that overcrowded districts have on citywide compliance – where class sizes are smaller, there are fewer classrooms and fewer students overall.

Chart 2: Districts with More Classrooms are Less Compliant with Caps, 2022-23 School Year

Source: New York City Department of Education

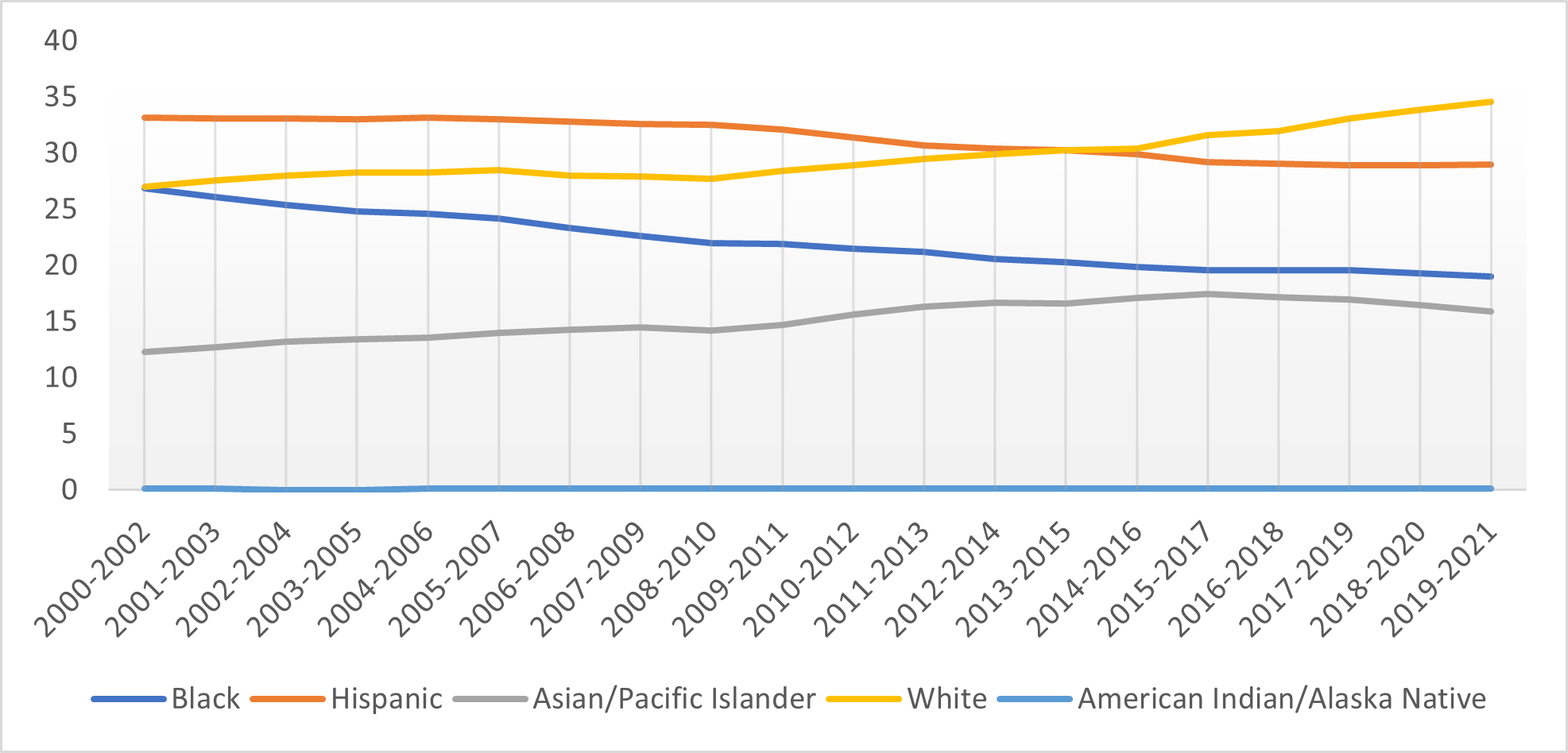

Citywide Student Enrollment Declines

Significant enrollment shifts in New York City have shaped public schools over the last decade. While 61 percent of classrooms remain out of compliance with the new class size mandate, the rising lack of affordability, immigration and outmigration, changes in birth rates, charter schools, and the pandemic have driven overall enrollment at DOE down–a trend that is also seen in municipalities across the country.[24] According to the 2020 Census Results for New York City[25] the total population of the City grew 7.7 percent between 2010 and 2020; Brooklyn grew fastest at 9.2 percent. At the same time the Black population citywide declined by 4.5 percent. In Brooklyn, with the largest number of Black residents in the city, the Black population declined by nearly 9 percent. Since 2000 the number of children born in New York City has steadily declined—a drop of 23 percent between 2000 and 2021 even as the City’s total population has increased. Concomitantly Black representation among total NYC births declined from 27 percent to 19 percent in 2021—a decline of 30 percent.[26]

Chart 3: Percentage of Births in New York City by Race/Ethnicity, 2-Year Averages

Source: March of Dimes

Over the same period of time, enrollment in New York city public schools declined significantly, as can be seen in Chart 4. Although the long-term decline in enrollment has reversed slightly in the current school year due to the enrollment of thousands of children from families seeking asylum, between 2012 through 2022 enrollment in New York City district public schools declined by 12 percent. According to DOE between 2012 and 2022, schools with enrollment of fewer than 200 students grew by 60 percent, while schools with enrollment over 600 students declined by 33 percent. The School Construction Authority (SCA) forecasts continued enrollment declines going forward—a drop of 22 percent between the current school year and 2032-33.[27]

Chart 4: NYC District School Enrollment Trends 2011-12 Through 2021-22

| Total | Black | Hispanic | Asian | White | |

| Since 2020 – 21 (1 Year) | -5% | -7% | -4% | -5% | -7% |

| Since 2017 -18 (5 Years) | -11% | -19% | -9% | -6% | -13% |

| Since 2012 – 13 (10 Years) | -12% | -32% | -9% | 1% | -9% |

Source: New York City Department of Education

Map 2: NYC Public School Enrollment Declines by District

Source: New York City Department of Education

Underutilized Schools in Historically Black Neighborhoods

Enrollment declines have been particularly acute in Black communities. Between 2012 and 2022, Black students enrolled in New York City Public Schools declined by 32 percent. As seen in Map 2, these trends are evident in the geographic distribution of declines. Districts in Northern Manhattan and Central Brooklyn–home to historically Black communities– have seen the greatest declines in total enrollment. Additionally, an analysis of enrollment declines amongst Black students shown in Map 3 reveals that the population of Black students declined in every district of the City between 2012 and 2022 with declines of 45 percent or greater in districts in Central and Southeastern Brooklyn and Northern Manhattan.

Map 3: NYC Public School Black Student Enrollment Declines by District

Source: New York City Department of Education

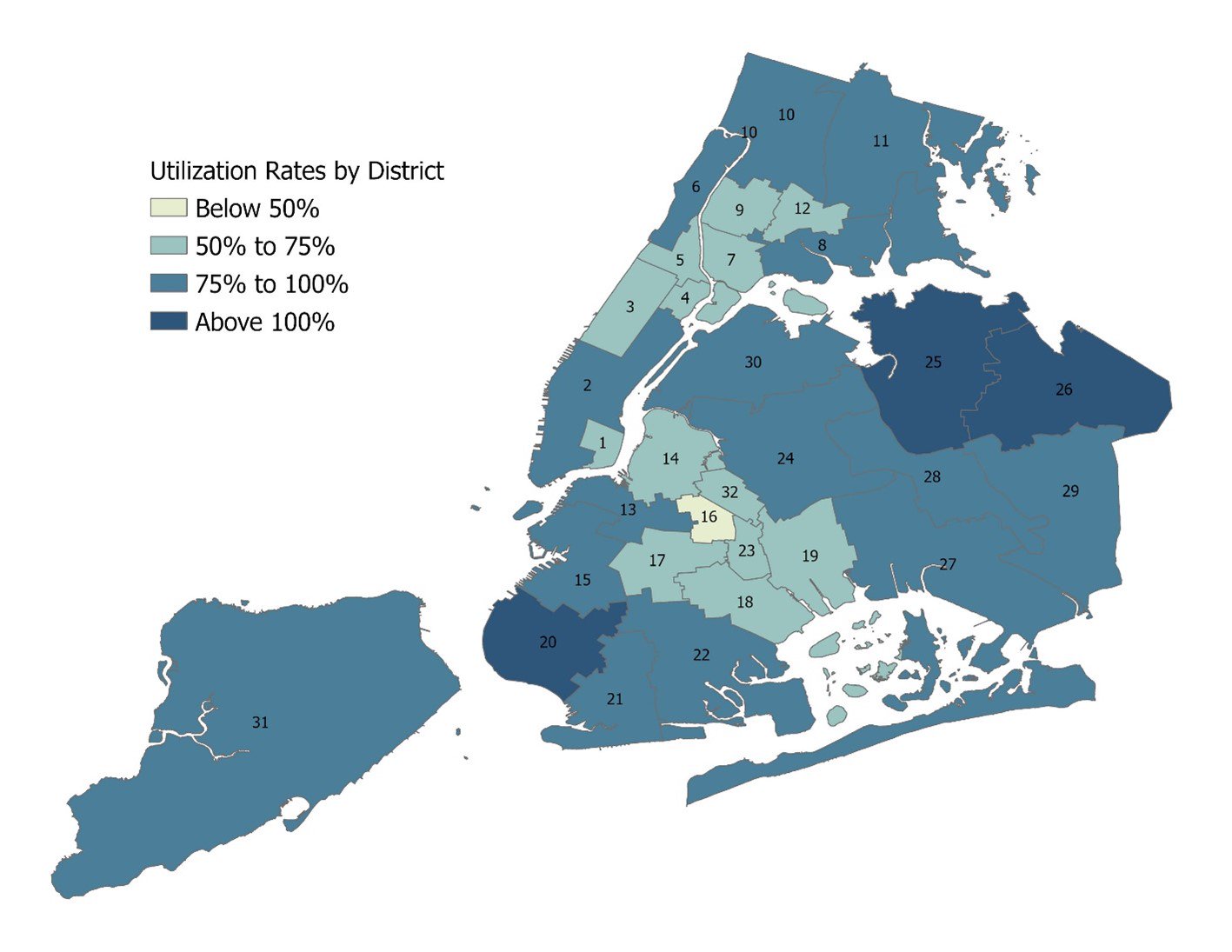

As enrollment has declined overall, so has school utilization in those neighborhoods with marked declines. As seen in Map 4, an analysis of district wide utilization across the City shows that districts that have the lowest levels of space utilization largely represent low income and working class Black and Hispanic communities (with one notable outlier in Queens[viii]). Schools in District 16 in Central Brooklyn utilize just 45 percent of available space.

Map 4: Utilization Rates by District, 2021-22 School Year

Source: New York City School Construction Authority

As evident in Map 5 districts where a substantial proportion of schools now have fewer than 200 students largely mirror those districts with substantial enrollment declines and low utilization rates in Upper Manhattan and Central Brooklyn where classrooms also are amongst those with the highest levels of compliance with the class size caps.

Map 5: Percent of K-12 Schools with Fewer than 200 Students by District, 2021-22 School Year

Source: New York City Department of Education

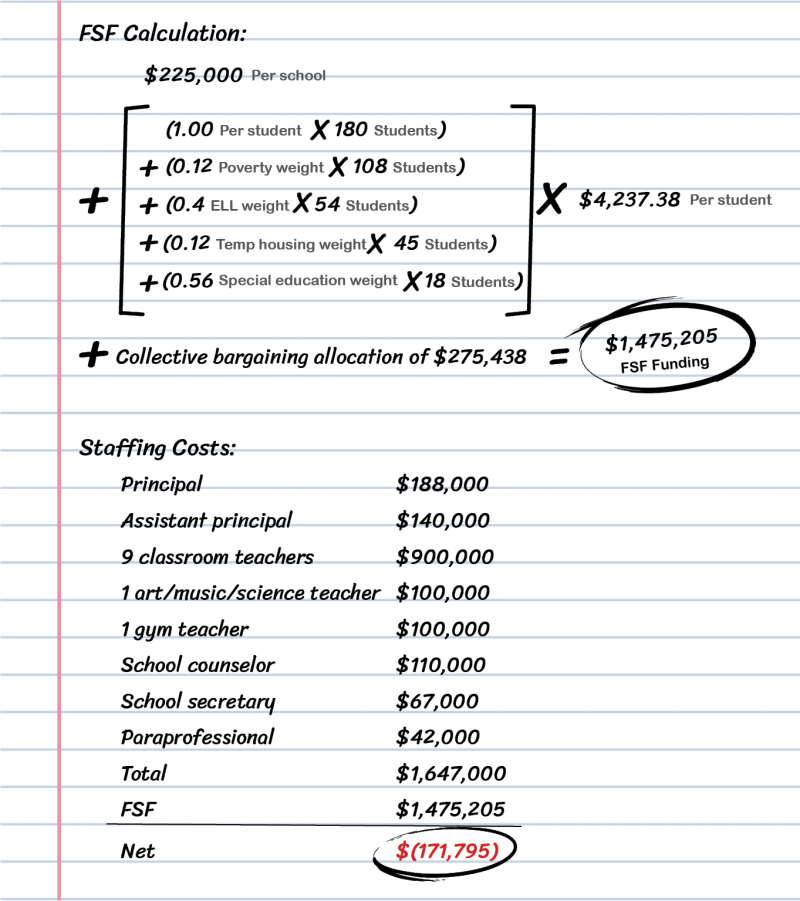

The increase in schools with fewer than 200 students raises concerns about financial sustainability for those school communities. Enrollment has a large impact on school budgets, as per capita Fair Student Funding (FSF) represents a substantial proportion of school budgets dedicated to staffing.[ix] Every school regardless of enrollment receives the same amount of foundation FSF—$225,000—which is provided to cover the costs of “core staff” such as the principal, assistant principal, or counselor. However, most other aspects of the formula that determines a school’s available funding are wholly dependent on enrollment.

As illustrated below, using the 2023-24 FSF formula, a hypothetical elementary school with 180 students and estimated average staffing costs for a modest number of staff (a principal and assistant principal, 9 classroom teachers (enough to meet the new class size caps), just one specialty subject teacher, one gym teacher, one paraprofessional, a counselor, and one secretary) would not have enough FSF to cover staffing costs (let alone programming and school supplies) and would need to supplement with other funding sources or make cuts. This illustrates the limited resources of underenrolled schools — the current funding formula does not allow schools with fewer than 200 students to cover all necessary staffing costs while meeting the class size caps. While all schools have other sources of funding (such as federal Title I or funding for arts initiatives or Summer Rising), those streams are often restricted for specified purposes and are not available for general staffing or programming. For a larger school, the ability to amortize fixed costs such as the principal and counselor over a larger number of students leaves more funding for other staff and programs. Given the serious financial constraints facing small schools, school mergers are being utilized by DOE right now to achieve cost synergies and create larger combined schools with a consolidated administrative structure, increased enrollment and an associated increase in funding.

Figure 1: Elementary School FSF and Staff Budgeting Example

Source: NYC Department of Education, Office of Management and Budget

School Mergers as a Strategy for Integration, Reduced Class Size & Improved Student Outcomes

Given the demographic shifts and enrollment declines in New York City public schools, and the very high cost of new classroom construction, DOE will likely look toward school mergers as a potential solution to address the overcrowding in the estimated 56,000 classrooms that will need to come into compliance with the new class size law by 2028. Beyond mergers between two small schools, mergers can also be used to reduce class size when one of the schools is overcrowded. This dichotomy makes finding school merger possibilities that reduce class size and foster integration challenging–but not impossible. Such was the case with two schools in District 13.

District 13 in Brooklyn is in the middle of the pack with regard to class size law compliance—61 percent of classes in the district were above the caps in the 2021-22 school year. Yet the district underwent a rapid gentrification over that last decade, as the number of Black students declined by 40 percent while the number of white students increased 63 percent. Changes to the demographics and enrollment at each school, in addition to willing school leaders and interested community members, presented DOE with an opportunity in 2019 to craft a merger to address respective enrollment and utilization concerns, and a more equitable, integrated school community—Arts & Letters 305 United.

A Case Study of Prioritizing Real Integration in School Mergers: Arts and Letters 305 United

Introduction and History

As noted above, school mergers in the New York City public school system often solve for the operational, enrollment, and financial needs of each school. This was true in 2019 for two Brooklyn schools, Arts and Letters (A&L) and P.S. 305, now known as the unified Arts and Letters 305 United (United).

In 2019, A&L was bursting at its seams, operating at over 130 percent capacity while being co-located with P.S. 20, another school that was also at over 130 percent capacity.[28] In comparison, P.S. 305 was under-enrolled, operating at only 36 percent capacity. By January 2020, the stark gap in utilization only widened, with A&L reporting 145 percent capacity and P.S. 305 reporting just 16 percent.[29]

A&L was founded as a middle school in 2006 in the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood of Fort Greene. The school was a highly sought-after, unzoned lottery-based kindergarten through eighth grade school in District 13. A&L often attracted affluent, liberal families across the neighborhood with its progressive project-based learning curriculum. In 2016 A&L became a part of the inaugural group of schools participating in an initiative to increase diversity within their schools called Diversity in Admissions (DIA). These schools prioritize targeted groups of students including, but not limited to, students whose families meet federal income eligibility requirements, English language learners, students in temporary housing, and students whose families are impacted by incarceration.

While seemingly diverse at first glance, a closer look at A&L demographics in the 2019-2020 school year in comparison to the district as a whole paints a more segregated picture. In 2019-2020, A&L students were 42 percent white, 29 percent Black, 15 percent Hispanic, and 5 percent Asian. This stands in stark contrast to the overall demographics of the district with students that were 18 percent white, 40 percent Black, 17 percent Hispanic, and 21 percent Asian. Similarly, while the percentage of students in District 13 who qualified for free-reduced priced lunch (FRPL) hovered at 63 percent; only 23 percent of A&L students were FRPL eligible.[30]

Table 5: Demographics of Arts & Letters and PS 305 Before the Merger, 2019-20 School Year

| % Black | % White | % Asian | % Hispanic | % FRPL | |

| A&L | 29% | 42% | 5% | 15% | 23% |

| P.S. 305 | 64% | 9% | 5% | 19% | 95% |

| District 13 | 40% | 18% | 21% | 17% | 63% |

Source: New York City Department of Education

P.S. 305 was a severely under-enrolled zoned elementary school in District 13, located in the heart of Bedford-Stuyvesant, a historically Black community. P.S. 305, while not in high demand, was a community school that anchored generations of learners with a rich culture and history– families in the neighborhood had children attending that school, as parents and maybe even grandparents had in the past. By the 2019-2020 school year, P.S. 305 had only 98 students, representing less than 13 percent of target capacity for the building. Of those 98 students, roughly 64 percent were Black, 19 percent Hispanic, 5 percent Asian and 9 percent white; 94 of the 98 qualified for free and reduced-priced lunch[31].

The characteristics and demographic profiles of both A&L and P.S. 305 mirror the similar stories, experiences, and data often reflected in overcrowded, under-enrolled, and segregated schools. This, in addition to their merger process which intentionally centered the values of integration, made United the perfect candidate for a case study. A closer look into their process and the communities, leaders, and students that made it happen provides crucial lessons and insight for future school mergers..

Case Study Methodology

From April to June of 2023, New York Appleseed staff and two staff members from the New York City Comptroller’s Office oversaw engagement and conducted interviews with 34 members of the United community. Interviews were on a voluntary basis and were conducted via Zoom or in person depending on the interviewees’ preference. Outreach efforts were multi-pronged to include as many voices from the community as possible. The following strategies were utilized:

- Initially the United Parent-Teacher Association was briefed on the project and provided with a one-pager on the report, its goals, and how community members could schedule an interview.

- New York Appleseed and Comptroller’s Office staff flyered outside of the school during both pickup and drop off on three different days.

- The principal was engaged consistently to ensure notice was sent out in the school newsletter. The principal was also critical to outreach efforts to families, students, and teachers who may have missed other communications.

- Suggested contacts from interviewees were contacted to increase the number of community members represented in the interviews.

Each interview was conducted by two people. Of the five staff members involved in this report, all identify as cis-gendered women. Two identify as white, one identifies as indigenous Latinx, one identifies as biracial Black and one identifies as Taiwanese American/East Asian.

Of the 34 interviewees– seventeen were parents, eight were students ranging from 5th through 8th grade, and nine were educators including school leadership. Eleven participants came from P.S. 305 prior to the merger, 17 came from A&L and one came from P.S. 20. The remaining four participants represented students, families, or faculty that came to United after the merger.

The racial profile of the participants was 50 percent White, 32 percent Black and 18 percent Hispanic/Latinx or Asian.

All recorded interviews were transcribed using Otter.AI software and checked for accuracy of transcription. Student interviews conducted on school premises with permission from the principal were not recorded, instead written notes were taken down in real-time. Appleseed and Comptroller staff then identified key patterns and trends from the data to provide the below analysis and recommendations.

The Groundwork: Laying a Foundation for a Merger

Often overlooked in the school merger process is the amount of groundwork that happens both internally and externally before formal approval from the Panel for Education Policy. The United merger process came as a surprise to few as the wheels of the process began turning during the Spring of the 2018-2019 school year–months before the merger was finalized.[32]

Several engaged community members noted they knew a conversation was forthcoming. For A&L parents, they knew their school was in dire need of new space given the overcrowding at the school. As one A&L parent stated, “For me, it was a clear need. From just a space perspective, Arts and Letters was crammed…”

Another expressed similar sentiments,

For P.S. 305, parents recognized enrollment was on a decline and the school was lacking resources. Based on the interviews, both communities had clarity on why something needed to be done to resolve their individual issues of overcrowding and under-enrollment, but it was the how, the where, and the what that was resolved through outreach and targeted engagement.

The United merger was deliberate about framing the process through a lens of equity. School and district leaders were making intentional choices to involve the community in the decision-making process for how the merger would take place. For example, all parents interviewed can recall some type of strategy in which they had access to town-hall-style meetings to ask questions and provide feedback. Of the 15 parents who were previously at 305 or A&L, all confirmed multiple town halls and/or facilitated meetings with the Parent-Teacher Association. School staff also confirmed efforts for outreach, with one teacher noting, “Yeah, we had several meetings, have had it through 305 building with the staff of both schools and the parents also. And everyone had an opportunity to ask questions and to view to share their views, their opinions, and so on.”

Engagement conducted by school leadership also did not shy away from addressing the apparent racial and socioeconomic differences between the two schools. One school leader discussed how anti-racism and equity were prioritized in discussions a year before the merger took place. Another parent noted that the year before the merger, in group meetings folks were acutely aware and overwhelmingly willing to discuss the racial implications of the process, “…they would have like big group meetings…we’re gonna talk about racism, we’re always talking about the integration process, we’re gonna talk about it, talk about it, talk about it, talk about it, talk about it.” Overall, several conversations noted that meetings with parents about inclusion, diversity, and equity helped ease anxiety about school integration over time.

Despite the good intentions of deeply involved school, district, and community leaders–challenges, foreseen and unforeseen, still arose. Three distinct challenges were evident in conversations with students, families, and staff:

- Developing trust and providing transparency;

- Addressing the racial and socioeconomic dynamics of power;

- Engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Developing trust and providing transparency. Although all adults interviewed for this study acknowledged that they had many opportunities to provide feedback on the merger, there was still a handful of parents and educators who felt the process could have been more transparent. One staff person noted the importance of authenticity when engaging parents, and for some, a lack of context led to feelings of distrust or apprehension about the merger process. Several parents echoed the sentiment of wanting more context and the feeling that unspoken politics were at play. Another educator talked about decisions regarding pedagogy and curriculum, noting, “That process wasn’t transparent to me…I had thought that prior to me starting the school year that it was, you know, there was a process that went into making those types of decisions. I don’t know who made those decisions.”

Addressing the racial and socioeconomic dynamics of power. A common theme throughout the interviews, especially from parents and educators, was whose voices, needs, and concerns were centered both within and outside of formal engagement sessions. Several parents across multiple racial backgrounds recount instances in which coded language was used to express discontent or apprehension about the merger. Commentary and questions ranged from concerns over the distance A&L families would have to travel to reach the new location, to more racially charged questions regarding whether or not the historically Black neighborhood of Bed Stuy was a safe area. As one parent recalled a more disappointing part of their experience they said, “It was a lot of…both like disappointment and quite frankly disgust with like, what emerged…there was a lot of language about…the number of like homeless families in this school and like, just, you know, like, isn’t that part of Bed Stuy really dangerous.”

Additionally, nine of the interviewees used the word “takeover” in describing the merger, often reflecting the wariness of P.S. 305 community members. The frequency of calling the merger a “takeover” reflects the imbalances of power at play throughout the process. Some of those imbalances were inevitable given the size differential of the two schools with A&L at over 300 students and P.S. 305 at just under 100 students. Several interviewees identified the power dynamics that facilitators could have helped rebalance, but were not meaningfully addressed, included whose pedagogies were going to be adopted, whose communities had the most access to engage in feedback, or whose community histories were informing dialogue. For example, we learned of one instance in which murals at the P.S. 305 building–meaningful to several educators in the building–were painted over during the transition without any notice. The “takeover” of the space by way of painting over the murals, and the harm inflicted by doing so, is one example of an imbalance that could have been easily rectified through better communication and centering the needs and thoughts of the P.S. 305 community.

Engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 was the most frequent challenge noted across all interviews. On March 16, 2020, New York City public schools closed due to COVID-19, interrupting the merger which was set for the following 2020-2021 school year. The pandemic was an unforeseeable and unavoidable disruption to any process that relied on in-person communication. Not only did school and district leaders have to work through the merger, they also had to navigate the onslaught of problems (i.e. daily reporting of school COVID cases, community notification and mitigating staffing losses, implementation of remote learning, assisting with student technology needs, developing building ventilation protocols, switching to outdoor learning) that accompanied a global health crisis. Additionally, students and families living in New York City through the spring and summer of 2020 were grappling with their own survival and the trauma of a citywide death toll of over 20,000 people between March and August.[33]

COVID left much to be desired for many in terms of engagement opportunities across the two communities, yet some interviewees grasped at silver linings. One parent summarized the insurmountable challenges they had to overcome by stating:

“COVID happened…I honestly, you know, don’t understand how they– how we managed. You know, how it all worked out? I think that to me…through the hardest years, we also expanded and grew and, you know, merged two communities. So I think, considering the setting, people did really well.”

A student explained how remote learning, as a result of COVID, minimized changes felt solely due to the merger:

“Well, we were remote. Right? By the time they had merged, in the new building in fifth grade I was only going for like, half the time in fifth grade. So, it didn’t really feel like…also because I was kind of in this same classroom the whole time, because they’re trying to limit like, contact, so I was in the same classroom all the time. So, fifth grade didn’t really feel like I was in the new building.”

To summarize, the merger process for United, like all other aspects of life, was not immune to the pandemic and its many consequences. Although noted as a challenge by nearly 20 of the interviewees, several countered that both communities–like many New Yorkers during this time–found or developed new pathways to move forward.

Becoming Arts and Letters 305 United

The Academy of Arts and Letters and P.S. 305 became Arts and Letters 305 United in the fall of 2020, while schools were still grappling with COVID-19. The challenge of engaging the separate communities and teachers before the merger continued into the first year of the merger.

The following questions reflect key trends that arose from interviewee responses when asked about their thoughts, feelings, and observations of the post-merger process.

- How do you bridge two separate and distinct school cultures equitably?

- What spaces must be created for parents, students, and staff to build relationships across difference substantively and effectively?

- How can students be best supported in adapting to two major changes, one being a new school, and another being hybrid learning?

How do you bridge two separate and distinct school cultures equitably?

Through conversations with parent leaders and staff across both communities, it became clear that the two schools had very different cultures, especially with respect to curriculum and parent engagement. For example, staff at Arts and Letters had teacher-created curricula and units of study; P.S. 305 used curricula that were provided by New York State or DOE. The units of study from Arts and Letters spoke to the progressive learning style that was core to the vision of the school and continuance of this teaching style and philosophy was important to the A&L staff interviewed. In juxtaposition, P.S. 305 staff used a more structured, less interdisciplinary curriculum that lent itself to established city and state resources and assessments.

Bridging these different teaching practices proved a tenuous and imperfect process according to feedback voiced during interviews. Several staff vocalized a desire to have engaged more directly and intentionally in conversations about how to merge two school cultures. Despite these tensions, teachers were receptive to what they saw as the benefits of each other’s teaching styles. Several teachers acknowledged that despite their differences, their intrinsic motivation to implement a curriculum that was in the best interest of the students was a unifying goal. As one teacher noted:

“Well, I believe it’s all up to the teachers. Up to you as a teacher. You want to make your curriculum richer. You want to make the experiences for the children richer and more meaningful. There’s always a way to get that done.”

Much like teaching pedagogy and practices, parent engagement at the two schools was markedly different. At Arts and Letters, the PTA was incredibly robust and the presence of parents in many aspects of the school was highlighted in several interviews among both staff and parents. As one parent clarified,

“…at the old Arts and Letters, parents were so involved that in terms of like supports for teachers, or filling in holes where things weren’t happening, it was like, okay, well, maybe we should do a field trip on this, or whatever it was. But I’ve never seen–well, I hadn’t been anywhere else–but like a parent community where there’s so much volunteer labor.”

For the P.S. 305 community, there was not strong parent support and engagement systems within school walls. As one previous P.S. 305 parent described:

“We never really spoke to each other like even before the merge, like parents. They just drop the kids off and go. And the only time parents came out is like, when we had, okay, what we used to have an award ceremony, or we used to have Black history month and the kids would, you know, recite a poem or learn the songs…”

Another previous P.S. 305 parent echoed these sentiments and spoke to the challenges of engaging parents and struggling with attendance at PTA meetings. The distinct and different ways each community defined parent engagement and support was a tension the school had to process in its first year and beyond. Parents from Arts & Letters had more power in governing spaces because many of them played an active role in those communicative spaces before the merger. This imbalance did not go unnoticed, and interviewees expressed a wide range of experiences and feelings concerning how parent and family outreach and involvement were conducted post-merger.

What spaces must be created for parents, students, and staff to build relationships across difference substantively and effectively?

Through many of the interviews, there was a desire for intentional community-building. When school community members praised the schools’ engagement efforts it was often because the interviewee was part of an in-depth workshop or series of workshops that were taking deep dives into equity-related topics such as anti-racism or diversity. For example, Kindred Communities, a Washington D.C.-based organization that provides programming and facilitation for schools to create anti-racist and liberated spaces, is a program available at United that was referenced positively and often. Participants of the program often reflected on the authenticity of the sessions and were appreciative of a 10+ week program that delved into how various identities showed up in places and spaces at the school in either beneficial or harmful ways. As one participant of Kindred reflected, “Now we’re like, after 10 weeks, we are, we’ve grown, all of us grew about differences. We don’t see our reality as the truth like multiple truths can exist. And now we’re like, taking actions.”

When interviewees expressed negative feelings toward building relationships across difference, it was often because school community members felt underlying tensions were going unaddressed. For example, two separate parents brought up an observation of white parents only saying hello to other white parents or simply not greeting members of the historically Black community of Bed Stuy. Another parent discussed their child’s report back of the use of the n-word by a white child at the school. In these instances, interviewees acknowledged the harm caused, but were further concerned or expressed disappointment in how the school failed to intervene or attempt to repair the harm.

However, we cannot say these instances are the result of a complete lack or disregard for restorative measures. In some cases, United made an effort to implement reparations for harm and engage in proactive discussions to prevent harm. For instance, United established anti-racist committees and programs like Kindred. Though the school’s support for these programs is a significant step, not everyone at the school has access to such valuable resources, which indicates that the school must continue to expand access to these initiatives to the entire school community.

How can students be best supported in adapting to two major changes, one being a new school, and another being hybrid learning?

At the heart of any major change to a school is a question of how it will affect and better yet, benefit the student’ it’s meant to serve. In the first year of the merger, students were not only adapting to a new school but also to a “new normal.” No one in the interviews minimized the impact of COVID-19 on students and families. However, several did note the inevitable pause and transition to remote learning created a few benefits for the merger process. Mainly, the first full year of the new school operating with hybrid and/or remote learning created a period that acted almost like a transitional cushion for students and staff by mitigating potential harm that can follow a more condensed or rushed timeline.

For example, one educator noted the period of hybrid and remote learning almost acted as a buffer for the many changes that accompanied the merging of two communities, noting:

“So like, the students coming in, some didn’t even know each other because they never were in class together. Because some were online. So that was kind of nice for the students because it felt like it was kind of almost like a fresh start for everyone. So it was a good time in that sense to merge in. Mostly the kids within my first year hadn’t been together with each other since first grade.”

A parent shared a similar viewpoint stating, “…but in some ways, like, because it was sort of a reset and the whole pandemic thing. It wasn’t any kind of intentional community building that had really been able to take place, but it was still like, people are just glad their kids are in school.”

Similar sentiments of appreciation for a gradual transition to a joined school community were reflected by students we interviewed. When asked what advice students would give other schools considering a merger, several students noted that the gradual transition was especially helpful. Three students, in particular, noted that the process can be overwhelming; however, adults should take their time, give the communities time to acclimate, and slowdown overall– adding that a rushed process can also neglect student input.

The Aftermath: The Merger is the Beginning not the End

The interviews for this report were conducted during the spring of 2023 and therefore reflect a sample of the communities’ sentiments three years after the initial merger. The interviews made very clear that the process of supporting a truly integrated school is ongoing–that the first year of becoming United marked the beginning, not the end of this journey.

The well-researched tensions that often accompany integration such as addressing historical dynamics of power across racial, cultural, and socioeconomic lines are still present and require intentional work. However, and more importantly, the well-researched and conclusive benefits of integrated learning environments are also becoming a highlight of the school community. For example, many of the interviews touched upon two important factors for creating an integrated school: resource equity and relationships across difference.

Both communities reflected on the merger process bringing much needed and awaited resources. For students and families from Arts and Letters, those resources were often space-related–finally having slightly smaller class sizes and room for push-in and/or pull-out services. For the 305 community, every parent and staff member interviewed noted that the merger drastically expanded the offerings and extracurriculars available to students and families. One student specifically highlighted their enjoyment of the new dance program offerings. Another student took notice of the accessibility of advisors and school counselors and noticed that most of their classroom experiences were with two teachers, instead of only one. A previous P.S. 305 staff member also noted staff had more resources, referencing the abundance of professional development now available.

Parents noted that United is explicit in its creation of diverse and inclusive classrooms. When walking through United, quotes from multicultural leaders line hallways, and racial diversity is reflected through artwork, posters, and books. Several of the interviewees noted that teachers were intentional in making room for students to not only see themselves in the school but also to have space to communicate what is happening in their specific community. One parent stated:

“There’s a really strong community. I’ve made friends through my son’s friendships. The integration is explicit… if you walk the halls, like all of the artwork is Black Lives Matter. It’s not like February is the month we talk about. It’s talked about all the time. We have antiracism workshops for parents, so racial integration and racial justice is explicit and at the forefront.”

Integrated schools are also spaces that practice restorative justice, not only to replace harmful punitive discipline measures but to also have an infrastructure that repairs harm rather than adding to or ignoring it. From conversations with parents and staff, it seems United is familiar with both concepts and programming for restorative justice.. They have a restorative justice coordinator and action team working on disseminating resources and providing shared language to both students and their families. One staff member recalled that United is frequently cited as a model by DOE Central for restorative justice implementation.

While it is evident that United is not unfamiliar with the implementation of restorative justice practices, interviews with other staff and parents offer a more varied understanding of its presence in the school. Several of the interviews reflected feelings that much of United efforts to implement restorative justice have started in their higher grades and are just matriculating to the lower grades. One parent of a younger child noted they had not seen it in action per se, “But I do know that speaking to a couple of teachers or hearing them speak about it [restorative justice], like they try to use restorative justice practices, and especially teachers of color like they’ve articulated it verbally, like, this is what we do when a child gets in trouble. And so, it seems like they are, that is on the radar.”

A staff member noted:

“One thing that I really wanted to advocate for was how do we translate restorative justice practices for lower grades because I know ’hat it’s a very like, upper grade thing to do to have to be able to have conversations with older kids. But this year, we actually had like a whole PD [professional development] on to how to do it for the younger grades, and we have like this piece path thing that all lower grade classrooms have where it’s a very, it’s like a structured conversation if a child felt like offended in any way. And so I think restorative justice is now I guess, blossoming in the school practices.”

Identifying Opportunities for Integration Inclusive School Mergers as a Cost Effective Remedy for Class Size [34]

The high cost of school construction has created a dire necessity to utilize other methods of class size compliance including school mergers which are not only less costly, but also result in economies of scale and an increase in total per student funding for the merged school. Achieving these goals via a school merger that also prioritizes integration is challenging given the demographic and geographic differences across NYC school districts – but as United makes clear, there are real world opportunities to merge schools in a way that will ensure compliance, save costs, and put the City on a path toward meaningful integration.

Using an analysis centered on integration as well as class size reduction this report identifies three additional school merger scenarios that would result in class sizes below the caps and greater integration and inclusion in the merged school. They are presented here to show that an analysis centering integration can be used to identify potential mergers, not to suggest such mergers absent the community input essential to these decisions. The schools in this analysis have been anonymized to ensure that any and all potential school merger conversations are approached by DOE leadership with the careful intentionality needed to ensure success. One example is highlighted below; the two others are described in the Appendix.

Hypothetical Merger: School Y and School Z

School Y serves students in PreK through 5th grade in a standalone building. In the 2021-22 school year School Y was at 137 percent utilization of available space. School Y has a low ENI of 45 percent compared to the district average of 66 percent. In the 2021-2022 school year, School Y was 47 percent white, 19 percent Asian, 2 percent Black, and 29 percent Hispanic. 14 percent of students at School Y were learning English as a new language. Eleven percent of students had disabilities. At the district level, 18 percent of students were white, 20 percent of students were Asian, 6 percent Black and 53 percent Hispanic. Twelve of the 23 classes at School Y are over the class size caps. School Y has an embedded gifted and talented (G&T) program with a single class in each of grades K-5. All of the G&T classes in the school exceeded the cap and represented 50 percent of the overcrowded classrooms in the school.

Table 6: Demographics of Schools Y and Z Before and After Hypothetical Merger

| School | % Black | % White | % Asian | % Hispanic | % Poverty |

| Y | 2% | 47% | 19% | 29% | 41% |

| Z | 23% | 10% | 16% | 49% | 89% |

| Merged | 11% | 31% | 18% | 37% | 61% |

| District Average | 6% | 17% | 20% | 54% | 66% |

Source: New York City Department of Education

School Z is a 3K-5 elementary school is the same district at School Y. School Z has a standalone building that is little under 1 mile away from School Y. The 2021-22 ENI of School Z was 89 percent– well above the district average; 21 percent of the students at School Z were learning English as a new language and 23 percent of the students were students with disabilities. In the 2021-22 school year, School Z was 10 percent white, 16 percent Asian, 23 percent Black and 49 percent Hispanic. Just two of the school’s 17 classes were over the class size cap. School Z does not have a G&T program.

Neither of these schools are in buildings with the capacity to hold the larger merged school, however creating an upper and lower school spread across both campuses, as was done in District 15 in 2014 (see below), would integrate classrooms while ensuring compliance. Given the capacities of both schools, School Y and School Z could combine to create an integrated school on the two campuses. Grades 3K-1 could be accommodated in the School Y building, while grades 2-5 could be accommodated in School Z. An analysis of DOE data for class sizes in each school suggests that even while expanding the number of classes to meet the caps, creating these two grade cohorts could be an effective solution. This merger scenario could serve as a model for two different means of integration– racial and socioeconomic. the poverty level of the merged school would be 61 percent vs. 66 percent for the district.

An impediment to this merger is the G&T program at school Y which limits redistribution of students in the most overcrowded G&T classrooms and demonstrates the barriers to achieving smaller class sizes presented by the screened admission programs in many schools. Across the City, as shown in Chart 8, G&T classes are on average more overcrowded than general education classes in every grade. Because of G&T admissions, the crowded G&T classrooms would remain crowded unless future enrollment was limited, or additional space was available to split G&T classrooms. In the hypothetical School Y and Z merger, the G&T program necessitates adding 5 more classrooms than would be needed if the school had a fully integrated schoolwide enrichment program in place of the G&T program.[35]

Table 7: 2022-23 Citywide Class Size by Grade: A Comparison of General Education and Gifted & Talented Classes

| Grade level | Program type | Number of students | Number of classes | Average class size |

| K | Gen Ed | 33,502 | 1,630 | 20.6 |

| K | G&T | 1,871 | 86 | 21.8 |

| 1 | Gen Ed | 32,093 | 1,410 | 22.8 |

| 1 | G&T | 2,142 | 81 | 26.4 |

| 2 | Gen Ed | 29,838 | 1,324 | 22.5 |

| 2 | G&T | 1,973 | 76 | 26 |

| 3 | Gen Ed | 28,343 | 1,251 | 22.7 |

| 3 | G&T | 2,966 | 117 | 25.4 |

| 4 | Gen Ed | 28,734 | 1,223 | 23.5 |

| 4 | G&T | 2,149 | 86 | 25 |

| 5 | Gen Ed | 29,799 | 1,263 | 23.6 |

| 5 | G&T | 2,259 | 88 | 25.7 |

Source: New York City Department of Education

Recommendations

Citywide Recommendations to DOE Central

Identify opportunities for school mergers to attain compliance with class size mandates, increase opportunity for school integration, eliminate the presence of harmful barriers in schools, and track student outcomes.

United provides a real-life example of where the DOE was able to successfully merge schools to alleviate overcrowding in one of the schools, increasing integration in school classrooms and the efficiencies and funding associated with the overall increase enrollment. The Comptroller’s analysis used the best available data to reveal at least four additional school communities where the school merger approach could be successfully replicated. The DOE should conduct its own analysis using real-time enrollment and demographic information to identify opportunities for school mergers, assessing the following indicators:

- Reduce dissimilarity within the district;

- Reduce racial and socioeconomic isolation present in the district;

- Limit academic stratification and close the opportunity gap, taking into consideration the range of opportunities and academic ability present at both schools;

- Ensure under-enrolled and under-resourced schools gain greater access to resources;

- Support overcrowded schools in meeting the new class size mandates; and

- Provide the means to thoughtfully identify, track, and improve student outcomes post-merger. Currently there is no available portfolio of DOE data on important metrics that could support school communities after the merger. These could include tracking longer-term demographic changes, availability of resources to maintain school diversity, K-2 reading level data, student attendance, teacher retention, service provision to students with disabilities, where graduating students go to middle school, high school and whether they go on to college.

Create new opportunities for school consolidation through the exploration of new models of innovation and school redesign

While opportunities for school mergers that support both class size compliance and integration are limited, there are several strategies that could help create opportunities for school consolidation where they do not currently exist. It is strongly encouraged the DOE implement the following strategies:

- Reorganization of grade bands between schools. In 2014, DOE implemented a substantial rezoning plan across the Kensington, Borough Park, and Windsor Terrace neighborhoods triggered in part by the opening of a new middle school, MS 839 nearby. In response to community concerns that the rezoning plan would create more segregated schools, the District 15 CEC and the PEP approved a plan that maintained the diversity of the school and created an upper (grades 3-5) and lower campus (grades PreK-2) for PS 130 in two separate buildings. As District 15 illustrates, traditional grade band set-ups for elementary (K-5) and secondary schools (6-8 or 9-12) should not hinder an equitable merger opportunity. As seen in the hypothetical merger of School Y and Z, merged schools can utilize otherwise impractical spaces with restructured grade bands – e.g., prek-2, K-8, 6-12. Utilizing an upper school/lower school merger model to advance integration in school utilization changes has also been proven effective.

- Elimination of exclusionary admissions methods such as middle school screens or segregated gifted and talented programs that may be impeding a successful merger of two schools. Exclusionary screens alone have been proven to exacerbate segregation across schools and classrooms–eliminating them in favor of a merger that encourages integrated learning environments and lower class sizes can provide all students access to the well-documented benefits of both reforms.

- The State must repeal the requirement that New York City pay the leases for Charter Schools. In the meantime, the City must provide evidence that charter school co-location utilization proposals do not impede the ability of co-located district schools or any school in the district to expand its footprint to meet the class size caps.

- Facilitation by DOE of citywide coordination across traditionally siloed departments to effectively plan and execute school mergers in dialogue with school communities.

Support school community engagement throughout merger processes by replicating previously successful engagement models and implementing past local laws meant to improve equitable outreach and facilitate feedback on diversity initiatives.

The DOE, when both encouraged and determined, has implemented effective plans and programming that improve diversity in many schools and districts citywide. The success of these plans and programs, such as the District 15 plan or the Diversity In Admissions Program, is rooted in DOE and City Hall Leadership’s willingness to support and listen to advocates, community leaders and nonprofits emphasizing innovative action. To ensure an effective merger process that addresses segregation, sustains racial and socioeconomic diversity, maintains low class size, supports affected teachers, and communicates authentically with impacted students and families, the DOE should: