Report

Making Rent Count:

How NYC Tenants Can Lift Credit Scores and Save Money

Executive Summary

Every month, two million New York City households dutifully send their monthly rent check to their landlords. For many New Yorkers, rent constitutes by far their largest single expenditure per month, amounting to more than 35 percent of their paychecks on average.[i] In exchange, tenants gain a home for their families and a foothold within the five boroughs, but too often are denied a critical benefit: unlike those paying a mortgage, tenants almost never receive a benefit to their credit score from paying rent.

Credit scores can serve as a passport to the consumer economy, and individuals without credit scores or with low credit face severely restricted access to common financial services like loans, or markedly higher prices on phone, insurance, and credit card contracts. But for the vast majority of City tenants, rent payments are not factored into a renter’s credit report. As a result, many New Yorkers lack a credit score that accurately reflects their track record of responsibly meeting all of their financial obligations, including rent.

This report by New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer offers a first-of-its-kind estimate demonstrating how reporting rent payment information to credit bureaus could help lift credit scores across the city. Drawing on proprietary data provided by Experian, a credit bureau, this report offers a granular survey of credit conditions in each of New York City’s neighborhoods, and demonstrates how the addition of rent data can help consumers gain higher, more robust credit scores.

Focusing on a sample of New Yorkers paying rents less than $2,000 per month, the analysis demonstrates how the addition of positive rent data to a consumer credit profile could benefit types of credit scores which incorporate rent by:

- Raising credit scores for an estimated 76 percent of New York City tenants who elect to report their rent to credit bureaus, including significant increases of 11 points or more for an estimated 19 percent of participating renters. An additional 18 percent of tenants would likely see no material change to their credit score but would gain additional depth to their credit report. Six percent of renters would see a decline in their scores.

- Granting credit scores to individuals without a credit score or history. Within the sample population examined, as many as 28.7 percent of tenants with rents under $2,000 gained a credit score for the first time. The average new credit score amounted to 700 points, a prime score. Equipping more New York consumers with a credit score will give more families access to the many financial opportunities and savings associated with an increased credit score.

- Delivering a targeted benefit to low-income neighborhoods, communities with large shares of public housing residents, and minority communities. Within zip codes with an average credit score of 630 or lower, Black and Hispanic residents account for over 90 percent of the population. Similarly, the average credit score for communities where NYCHA residents comprise one in ten residents is also under 630. These communities would be poised to benefit from an appreciable increase in credit scores if rent was factored into the process.

With the aim of bolstering the credit profiles of New York City consumers and lifting the financial fortunes of renters, Comptroller Stringer offers a policy agenda that couples new financial opportunities and consumer protections, including:

- Empowering Tenants to Report Their Rent: Landlords, property management companies, banks, credit unions, nonprofits, community financial advocates, and third party reporting companies should do more to help willing tenants have their rent reflected in their credit scores. By innovating new products or expanding access to existing credit reporting methods that relay rent information, landlords and financial companies can help tenants and customers boost their credit scores.

- Rent Reporting for Public Housing: NYCHA should continue and expand a pilot program allowing its residents to report rent payments to credit bureaus, thereby benefiting a group especially likely to benefit from a boost to credit scores, to opt in to a rent reporting program.

- Give Rent More Weight in Credit: While an increasing market share of credit scores now factor in rent information, many credit scores do not draw on rent data. Changing restrictive federal laws would enable more banks and lenders to utilize credit scores that factor in rent information and allow more individuals to benefit from reporting their rent.

- Safeguarding Renters in Housing Court: Landlords should be prohibited from using rent reporting mechanisms to threaten or coerce any tenant withholding rent during an ongoing housing court case.

- Protections for Prospective Renters: The Comptroller urges ending a practice whereby credit checks undertaken by landlords on prospective tenants can negatively impact credit scores. Scoring models should be adjusted so that credit checks used in rental applications do not count against a consumer’s credit score.

- Giving Consumers Access to their Scores: The Comptroller calls for legislation to require landlords who run credit checks on prospective tenants to share credit reports with the applicant. Giving consumers access to their full report will allow consumers to scrutinize their credit history as it is being examined by landlords and will ensure tenants get value for their rental application fees.

- Helping Consumers Cultivate Credit: The City should devote further resources to an expanded program of consumer education initiatives that help New Yorkers understand the effect of credit within their financial lives.

In short, incorporating rent information into credit reports could provide a dramatic boost to a consumer’s credit score, enabling them to benefit from the many opportunities that result from having good credit. For many renters the addition of rent information will also grant scores for the first time to many previously unscorable customers.

Introduction

Modern consumer credit reporting was born 175 years ago in New York City. After having his stores repeatedly vandalized at the hands of pro-slavery mobs, abolitionist and silk merchant Lewis Tappan began to sell his goods on credit as a way to expand his customer base and save his business. To assess the likelihood that customers would repay any debts incurred at his store, Tappan started compiling information pertaining to a customer’s financial circumstances and their record of paying their bills in large, leather-bound ledgers. Tappan’s customer records were soon sought out by fellow merchants and store-keepers eager to better understand their customers. By 1841, Tappan established the Mercantile Agency, which expanded its record-keeping and information-gathering operations across the country with the purpose of reporting on the credit worthiness of all Americans. Among the local correspondents enlisted to compile and report consumer information were a young Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant.[ii]

Credit reporting has grown from Tappan’s ink-spotted ledgers into a global industry. In the United States, more than 1.3 billion pieces of data each month are factored into more than 200 million consumer credit files maintained by credit reporters.[iii] An individual’s credit score is their passport to the modern economy, granting them access to a number of financial tools and services. Credit scores help determine the prices consumers may pay on their phone or utility bill, as well as the terms and interest rates on credit cards, mortgages, insurance, and auto loans.

However, despite the enormous reach of the American credit system and the ubiquity of credit scores in the consumer economy, most credit reports ignore one of the best indicators of a consumer’s financial background – their rental history. This report examines the impact reporting rent history to credit agencies can have on the credit scores of New York consumers and proposes a number of methods of helping New York City tenants boost their credit score by sharing their rental history.

Calculating Credit: Understanding Credit Scores

An individual’s credit score assesses the likelihood a consumer will responsibly and reliably repay their debts. To create a credit score, credit bureaus and credit scorers examine information relating to a consumer’s financial history and their record of fulfilling their financial obligations. The information used to generate credit reports and scores is typically supplied by one of the nation’s three principal credit bureaus: Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion. These private companies collect the raw consumer information behind each credit score.

A three-digit credit score summarizes payments made to individual accounts and loans, including a consumer’s record of paying off credit card debt, student loans, auto-loans, retail accounts, mortgages, or personal loans. Credit scores also factor in how long a consumer has held credit, the amount of available credit that a consumer utilizes, and a consumer’s history of requesting further lines of credit.[iv] While a credit score distills these records into a single numerical score, more in-depth information about a consumer’s financial background is included in a longer credit report.

Credit reports organize accounts into tradelines. A tradeline groups all information relating to a single credit obligation into one stream of data. A typical credit report may include several different tradelines, each tied to different credit cards or loans. The number of accounts reporting to credit bureaus and the volume of information reported over time helps to ensure an accurate, representative score.

Credit scores are produced using models that vary in the way they evaluate different aspects of a consumer’s financial background. Though different credit scores share the broad goal of judging a consumer’s financial standing, there are myriad ways to compute a credit score based on applying different emphases to different pieces of information. For instance, a lender might request a credit score which more heavily weighs past car payments when a consumer is applying for a car loan.[v]

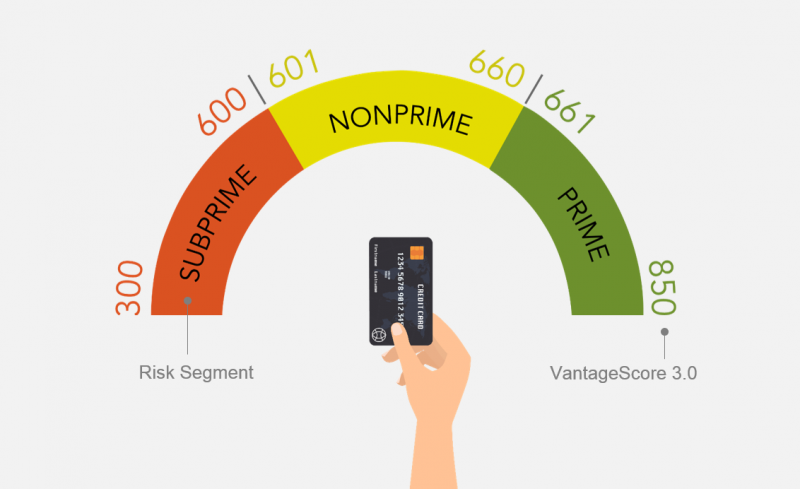

Credit scores, like the commonly used Fair Isaac Corporation’s FICO score, can draw on information from any of the three major credit bureaus. This report makes use of a model called the VantageScore 3.0, which utilizes a scale ranging from a low of 300 to a high of 850 and attempts to predict the likelihood a consumer will default on a loan over a two-year period.[vi] VantageScore is a credit score model developed by the three major credit bureaus which utilizes a consistent methodology to parse Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion’s databases and produce a score.[vii] As is the case for most credit score models, a higher VantageScore score is a better indication to a lender that a consumer can pay back a loan.

A VantageScore is composed of several elements, including a consumer’s history of repaying current and closed loans or financial obligations. Rental history, when available, forms a component of a VantageScore.

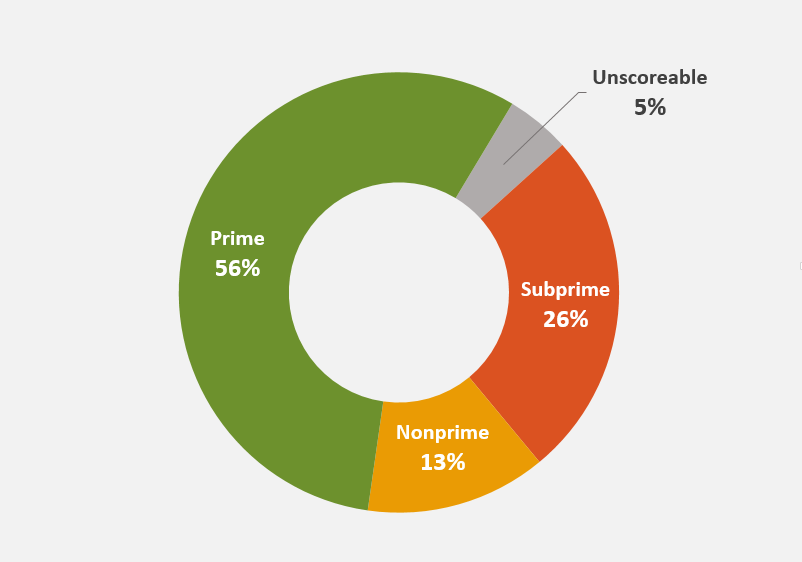

As Chart One shows, credit scores generally fall into three broad risk segments: prime, nonprime, and subprime. Generally, where a consumer falls within risk segments is more important to lenders than a consumer’s exact credit score. Prime scores represent the top tier of credit and typically allow consumers to borrow more money, at cheaper rates. Nonprime scores typically still allow access to credit, but with higher interest rates and under more restrictive terms. Subprime scores are the lowest tier in the scale. Falling into the subprime category may severely restrict a consumer’s ability to gain credit without paying exorbitant rates.

Chart One: Credit Score Ranges

Invisible and Unscorable: Restricted Access to Credit

Despite the significant role credit plays in our financial system, many Americans, including many New Yorkers, are without a credit score. According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), over 26 million consumers, or 11 percent of the United States’ adult population, were classified as credit invisible in 2010. Consumers categorized as credit invisible lack any discernable credit history and do not have a valid credit score.[viii]

Additionally, according to the CFPB, a further 19 million consumers, or 8.3 percent of the United States’ adult population, lacked enough of a credit history to produce a valid credit score.[ix] These individuals are often categorized as unscorable because of the relative dearth of information within their credit file. Consumers with thin files, defined in this report as possessing only zero to four items on their credit report, are more likely to be classed as unscorable than consumers with thick files, who typically have five or more items.

The CFPB estimates that approximately 20.8% of New York City adults either lack a credit file, have a thin file, or have a credit file mostly comprised of dated credit information.[x]

Several populations, including the young, the elderly, and recent immigrants, are more likely to have a limited or nonexistent credit history.[xi] Additionally, research by the CFPB shows that Black and Hispanic consumers are far more likely to be credit invisible or have unscorable credit records. Approximately 27 percent of Black consumers are estimated to be either credit invisible or unscorable.[xii]

Possessing a credit score is also strongly correlated with income. The CFPB found that approximately 46 percent of consumers living within low-income census tracks are without credit scores. In contrast, in census districts with higher incomes, only 4 percent of the population is categorized as credit invisible and another 5 percent hold unscorable credit records.[xiii]

Consumers and Credit: The Costs and Consequences of a Low or Nonexistent Credit Score

“Anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor; and if one is a member of a captive population, economically speaking, one’s feet have simply been placed on the treadmill forever.”

Novelist and essayist James Baldwin wrote those words more than half a century ago, reflecting upon the trials of living in poverty in New York City.[xiv] But he could just as easily have been talking about the present day system of credit scoring, which for many puts their feet directly on that treadmill and keeps them forever racing to get ahead in the American economy.

Whether they know it or not, credit scores factor into almost every aspect of a consumer’s financial life—from the rate of interest on a credit card, the ability to take out a mortgage or auto-loan, or the price of phone service. For many consumers, a higher credit score translates into lower interest rates, lower monthly payments, and lower cost loans, while a lower credit score may result in higher interest rates, higher monthly payments, and more expensive loans. Indeed, consumers with low credit scores may be entirely precluded from accessing certain services all together.

From housing to finance, an individual’s credit score can be the deciding factor between being denied a loan or securing a good rate, or having a rental application rejected or put to the top of the pile. The impact of credit on housing is particularly pronounced. In New York City, credit scores are frequently used by landlords to assess the financial history of an applicant for an apartment. Almost all New York City landlords and leasing companies run credit checks on prospective applicants, and many set floors for minimum scores.[xv] Consequently, a low credit score can potentially exclude tenants from prospective housing opportunities.

Home & Auto Loans

The importance of a credit score to a consumer’s pocket book is demonstrated by the pricing differences various credit scores have on typical loans, including loans secured for the purchase of a home or car. Consider a hypothetical family choosing to exchange their rental apartment for a starter home in the Bronx, priced at $450,000, the average cost of a one to three family Bronx home in 2017.[xvi] Having saved enough to make a purchase feasible, the family applies to their bank for a 30-year fixed mortgage. The lending bank determines that the consumer’s FICO score is between 640 and 659, a low score. Based on a score within that range, a bank would typically offer a mortgage with an annual percentage rate of 5.18 percent, according to a recent analysis of lending patterns.[xvii] The relatively high interest rate would ultimately cost the family $384,652 in interest payments on top of the $450,000 principal, over the 30-year term of the loan.

If the same family had applied for the same loan, but with a higher credit score, they could qualify for a much more competitive interest rate and could have potentially saved as much as $97,944 in interest payments on their loan.[xviii] Chart Two shows the degree to which a consumer’s credit score would impact the cost of purchasing home.

Chart Two: Example of Credit Impact on Mortgage Interest

| FICO Score | Annual Percentage Rate | Total Interest Paid |

| 760-850 | 3.60% | $286,708 |

| 700-759 | 3.82% | $307,066 |

| 680-699 | 4.00% | $323,413 |

| 660-679 | 4.21% | $343,532 |

| 640-659 | 4.64% | $384,652 |

| 620-639 | 5.18% | $438,359 |

Fico, 2017

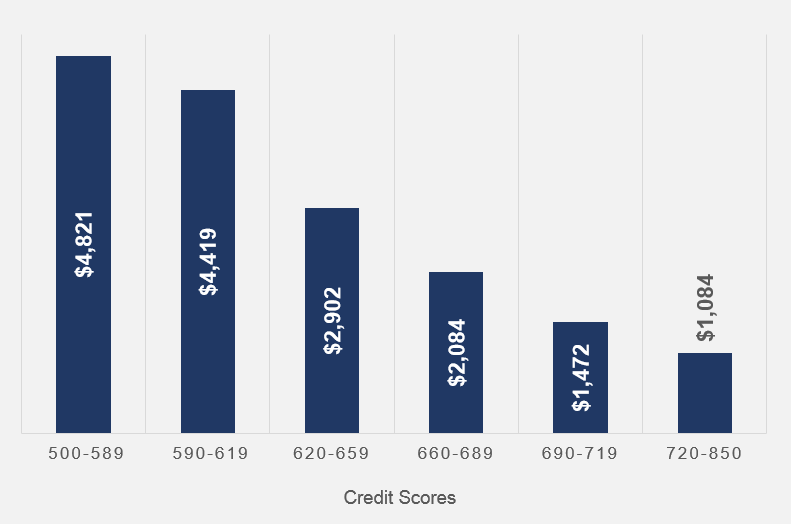

The impact of one’s credit score on the purchase of a car is similarly strong. For a New Yorker interested in qualifying for a 36-month auto loan priced at $20,000, a high credit score would result in a savings of approximately $100 per month over the lifetime of a loan, as compared to a similarly sized loan taken out by a customer with a subprime credit score. Ultimately, as shown in Chart Three, a consumer with a low credit score could be out of pocket by as much as $3,727 in additional interest, as compared to a consumer with higher credit.[xix]

Chart Three: Total Interest By Credit Score For A $20,000 Auto Loan

Fico, 2017

Insurance

The effects of a consumer’s credit score stretches beyond the initial purchase of a home or a car. Credit scores also play a significant role in the pricing of home or auto insurance. Upwards of 85 percent of auto or home insurers factor an individual’s credit score into their decision to offer and price insurance policies.[xx] A homeowner with subprime credit can potentially pay as much as 91 percent more for home insurance than a consumer with a high credit rating.[xxi]

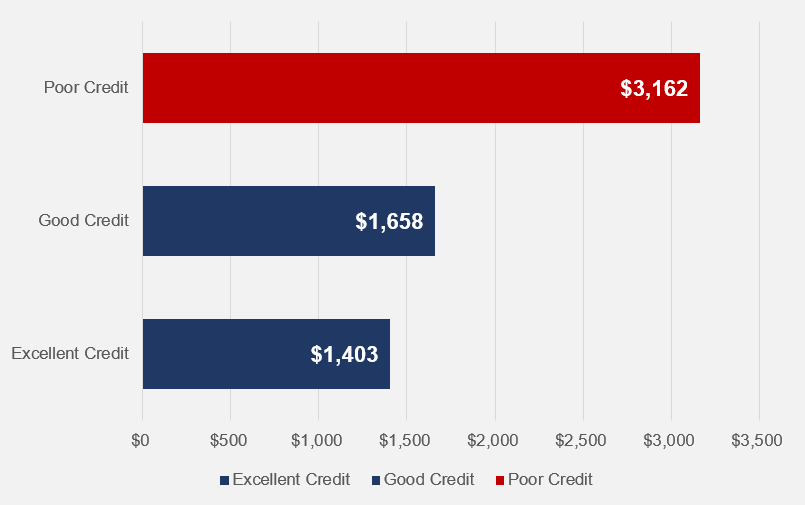

Similarly, as illustrated in Chart Four, an analysis of auto insurance costs for New York State drivers conducted by Consumer Reports found that insurance premiums for drivers with excellent and poor credit scores could vary by as much as $1,171 per year – a greater difference, in effect, than between the insurance rates for a driver with excellent credit and a driver with a conviction for driving while intoxicated.[xxii]

Chart Four: Average Auto Insurance Premiums in New York State

Consumer Reports, 2015

Credit Cards

The strength of an individual’s credit score also pays a large role in determining the rates and terms offered to them by credit card companies. According to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the likelihood that an individual will hold a credit card varies significantly by credit score.[xxiii] Subprime customers not making use of credit cards, either by choice or because credit card companies could not offer affordable rates, miss out on some of the benefits of credit cards, including rewards programs and the ability to stretch or defer payments across billing cycles. In addition, customers with poor credit scores may be targeted by financial companies seeking to sell expensive financial products. According to the National Consumer Law Center, a low credit score could potentially put a consumer “on the radar for […] predatory lenders who target high-cost credit to vulnerable consumers.”[xxiv]

Utility Bills

A consumer’s credit score also has the power to determine the price a consumer pays on their monthly phone, internet, or utility bills. In many industries, federal law permits risk based pricing, a practice which allows companies to charge variable rates depending on a consumer’s credit score.[xxv] Generally, companies use risked based pricing to “offer more favorable terms to consumers with good credit histories and less favorable terms to consumers with poor credit histories,” according to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and Federal Trade Commission.[xxvi]

The practice of risk based pricing is common in a number of industries, including cell phone providers. For example, a 2015 civil settlement between the Federal Trade Commission and Sprint revealed that Sprint charged consumers with lower credit scores an additional fee of $7.99 on their monthly bill.[xxvii] Other wireless companies have admitted that as many as half of their customers are without strong enough credit to qualify for their best value wireless plans, and as a result may pay more money for poorer service.[xxviii] Likewise, utility companies routinely research a prospective customer’s credit information and may offer or deny services based on an applicant’s credit score.[xxix]

Consumer Credit Rights

Several Federal, State and City laws and regulations protect consumers from unfair credit practices, credit discrimination, and predatory lending:

- Creditors may not discriminate on the basis of race, religion, national origin, sex, marital status, age, or welfare status. Creditors may not impose different terms or fees based on these factors.

- Consumers are entitled to receive a yearly copy of their credit report from each of the three principal credit reporting agencies at www.Annualcreditreport.com.

- Consumers can dispute any inaccurate or incomplete information on their report. If the consumer’s complaint is verified, credit reporting agencies must correct or remove any inaccurate data within 30 days.

- If your credit score or report is the basis for denying an application for credit, insurance or other services, the consumer must be notified by the creditor.

- Consumer reporting agencies can only release credit information to an approved list of groups with a valid need such as creditors, insurers, or landlords.

- Spouses can request to have their credit histories listed separately.

- New York City law bars employers from considering a prospective or current employee’s credit history when making decisions about employment.

- New York State law allows consumers to place a security freeze on their credit report if fraud is suspected.

In sum, a consumer’s credit score has an enormous bearing on their financial opportunities and economic wellbeing. A poor credit score can dramatically increase the amount a consumer pays towards their mortgage, auto loan, credit card, or phone bill, making it more challenging for a consumer to responsibly meet their financial obligations.

Charting Credit Patterns across New York City

With the goal of discerning how credit affects the lives of New Yorkers across the five boroughs, the New York City Comptroller’s Office utilized credit data provided by Experian to conduct a survey of credit patterns within New York City.[xxx] Drawing on an anonymized data sample, this analysis shows deep inequities in credit scores across New York City neighborhoods.[xxxi]

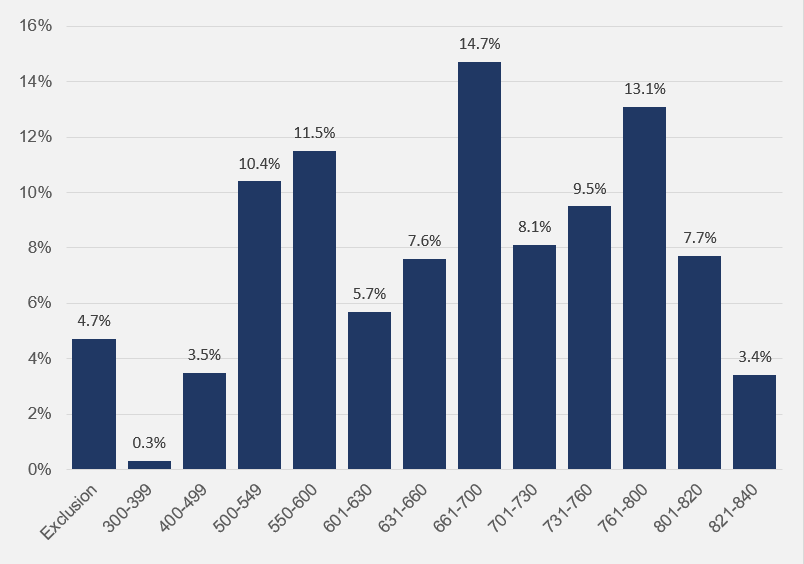

According to Experian’s consumer credit database, the average or mean credit VantageScore of all New York City residents amounts to 673, which classifies as a prime score. The distribution of different credit scores among New York City residents is depicted in Chart Five

Chart Five: Distribution of Credit Scores within New York City

Indeed, while the majority of credit scores across the city are rated as prime, a smaller portion of the city’s population fall in the nonprime range while a quarter of adult residents hold a subprime credit rating. The unscorable category depicted in Chart Six refers to individuals whose credit files are lacking enough information to produce a valid credit score.

Chart Six: NYC Credit Scores By Risk Classification

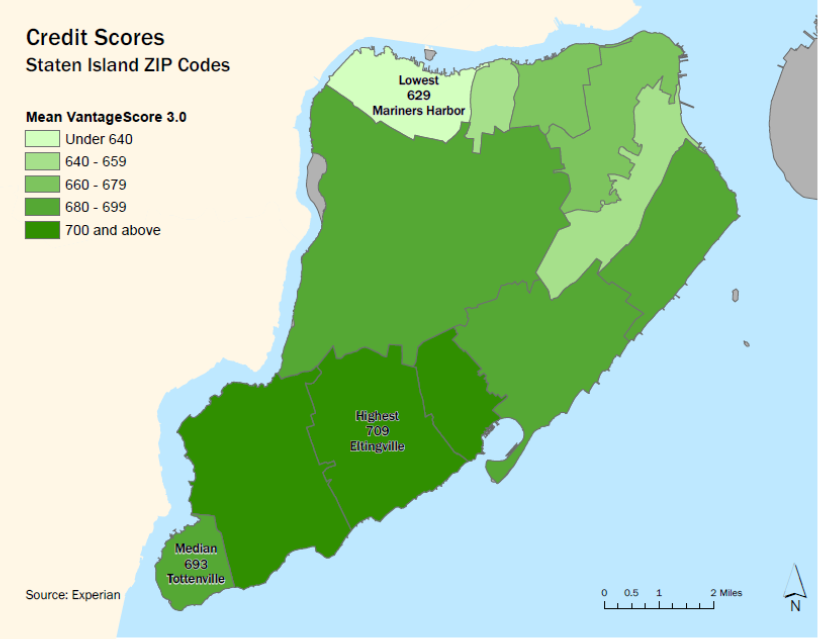

Examining credit patterns by zip code illustrates sharp disparities in credit scores across neighborhoods. The lowest mean credit scores within New York City are heavily concentrated in certain pockets of Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx, whereas the higher spectrum of credit scores are concentrated within Manhattan, Staten Island, and portions of northeast Queens.

Median Credit Score

| Lowest Median Credit Scores | Highest Median Credit Scores | |||||

| Zip Code | Neighborhood | Median Score | Zip Code | Neighborhood | Median Score | |

| 11692 | Rockaways | 578 | 11362 | Bayside / Little Neck | 753 | |

| 11212 | Brownsville / Ocean Hill | 592 | 10075 | Upper East Side | 751 | |

| 10030 | Central Harlem | 595 | 11364 | Bayside / Little Neck | 750 | |

| 10457 | University Heights / Fordham | 597 | 10024 | Upper West Side | 749 | |

| 10456 | Morrisania / East Tremont | 599 | 10023 | Upper West Side | 749 | |

| 10453 | University Heights / Fordham | 601 | 10021 | Upper East Side | 749 | |

| 10459 | Mott Haven / Hunts Point | 601 | 11360 | Flushing / Whitestone | 748 | |

| 10460 | Morrisania / East Tremont | 601 | 10028 | Upper East Side | 747 | |

| 10454 | Mott Haven / Hunts Point | 602 | 11375 | Forest Hills / Rego Park | 746 | |

| 11207 | East New York / Starrett City | 602 | 10028 | Fort Greene | 745 | |

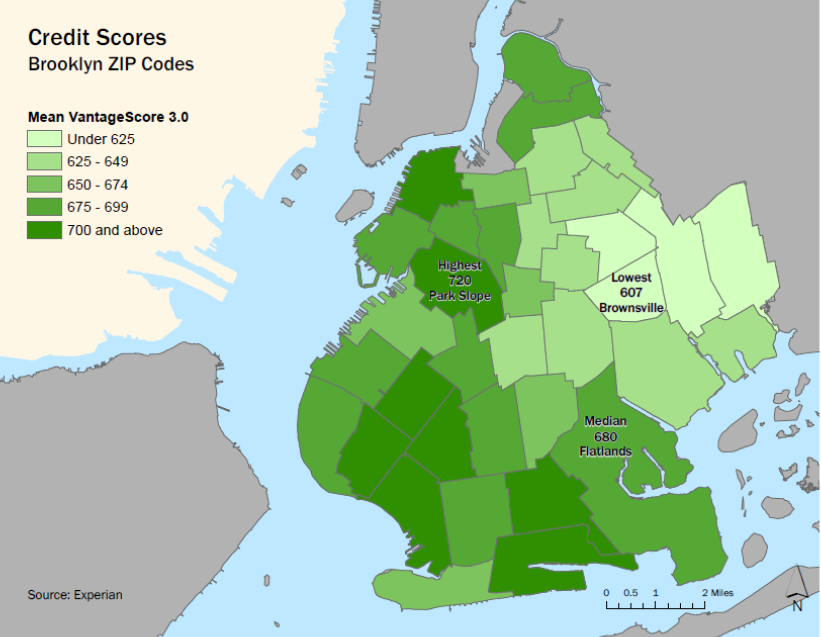

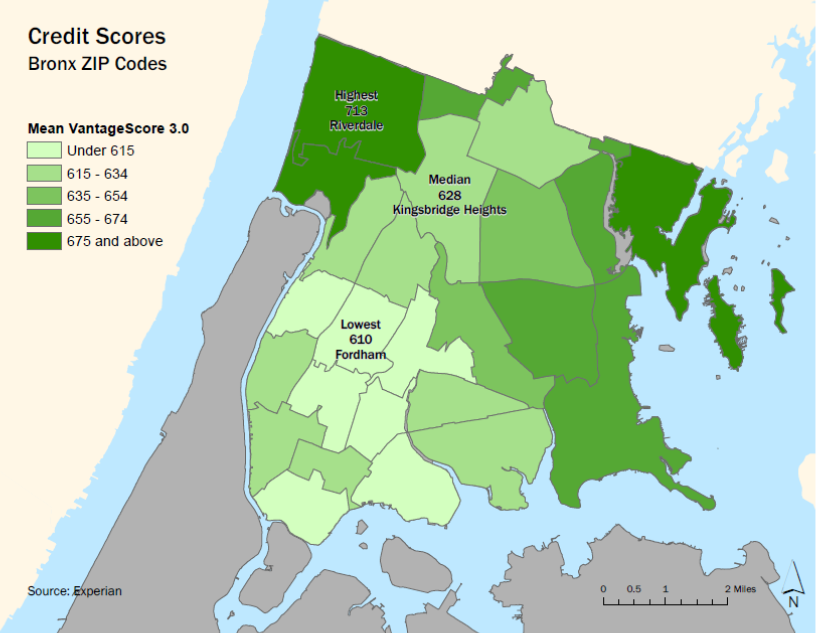

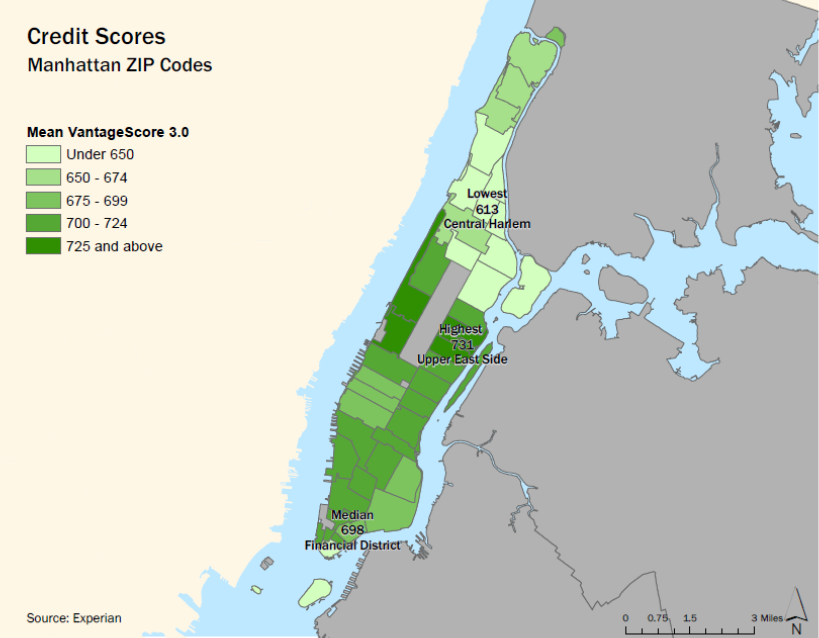

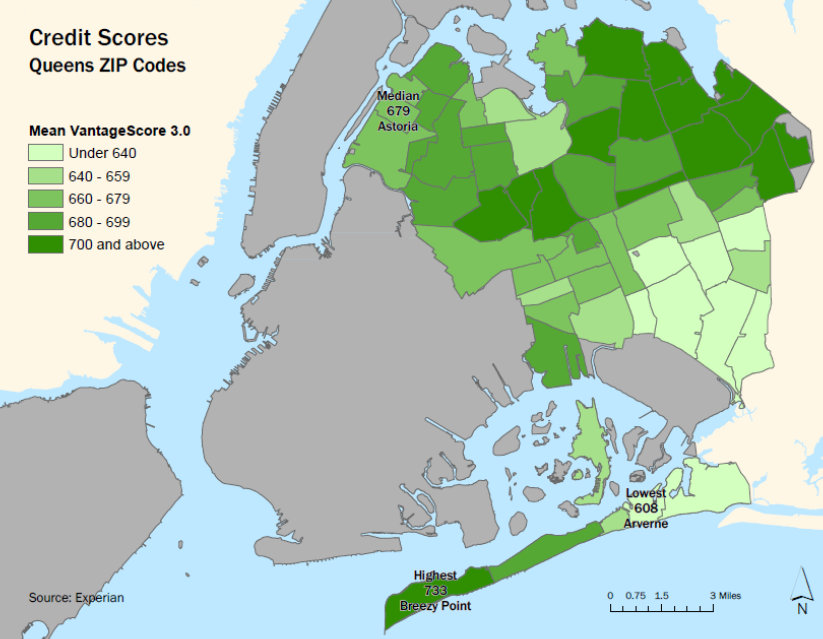

More detailed maps showing average credit scores by zip code in each borough are included in Appendix Two. In addition, the Comptroller’s website features an interactive map which offers further information for every zip code within the five boroughs.[xxxii]

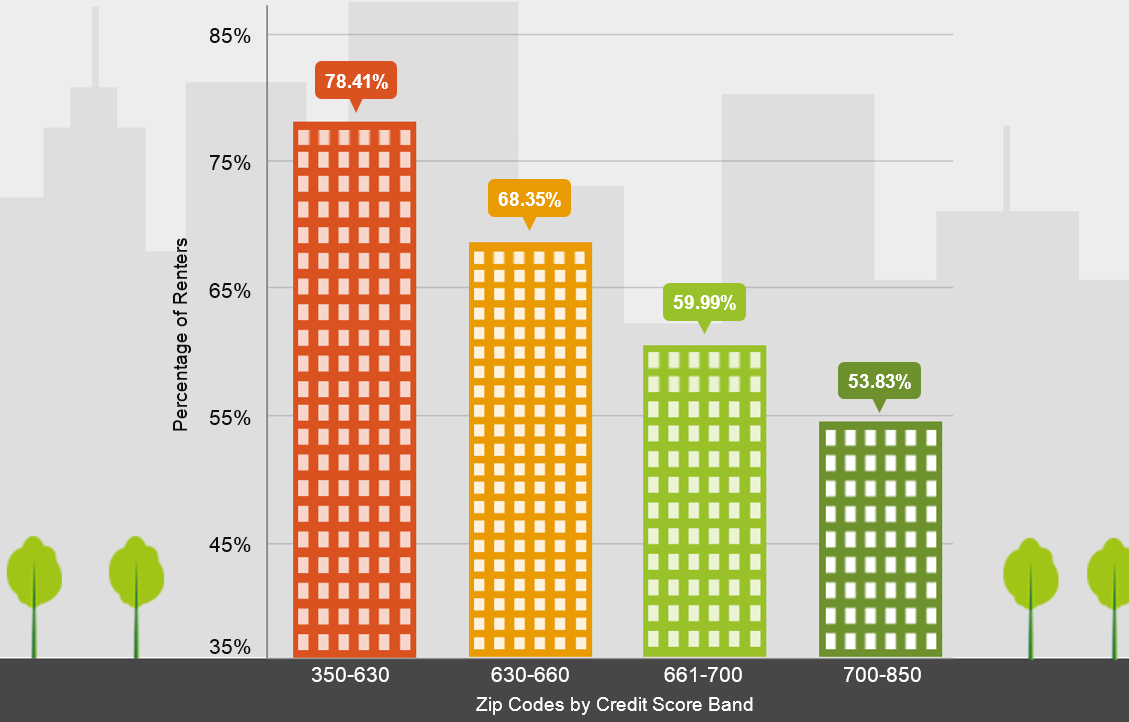

Alongside differences in credit score by neighborhood, credit scores vary widely by housing status. As shown in Chart Seven, within zip codes where the mean credit score is below 630, approximately 78 percent of the population rent their homes. This is unsurprising given that traits typically associated with home ownership, including higher incomes and regular mortgage payments, are mainstays of credit reports and can help lift credit scores.[xxxiii]

Chart Seven: Percentage of Renters within NYC Zip Codes Sorted by Credit Score Band

The high proportion of renters living in zip codes with credit scores below the city’s average suggests the transformative possibility of allowing rent payments to demonstrate creditworthiness.

Adding Rent to Credit Scores

For many tenants, a rent check represents the most substantial payment they make each month. Housing costs are the single largest monthly expenditure made by New Yorkers, on average accounting for almost 30 percent of income.[xxxiv] According to a survey of housing costs, three in ten renter households within New York City paid 50 percent or more of their household income in rent in 2014.[xxxv] For many New Yorkers a lease is their largest and most longstanding financial obligation, as well as a strong indicator of an individual’s ability to pay bills and abide by the terms of a contract.

However, unlike the many routine payments that contribute to a credit score – credit card payments, auto loan payments, mortgage payments, personal loan payments, and other transactions – rent does not factor into most credit calculations. Instead, rental payment histories tend to only impact credit scores when landlords pass on negative information about delinquent renters to collection agencies; positive information reflecting the vast majority of renters who conscientiously pay their rent every month is almost never shared. Under current law, private landlords are able to report data without the prior permission of tenants.

Recognizing the value of rental history as an indicator of a consumer’s financial strength, credit bureaus and nonprofits have experimented with incorporating select rental payment data into credit reports. However, given that rent data is not yet consistently relayed to credit bureaus, the vast majority of consumer credit scores do not factor in rent information, thus depriving many consumers of a major source of positive financial data.

Using proprietary data supplied by Experian, this report offers a first-of-its-kind analysis to estimate the potential effect of adding a typical rent history to a consumer’s credit history. The New York City Comptroller’s office conferred with all three major credit bureaus in the preparation for this report, and drew on Experian data for the breadth and specificity of information it offered on New York City consumers.

The analysis below examines how rent reporting has impacted New York City consumers and projects how enabling tenants to report rent to a credit bureau could lift credit scores across the city. For the purposes of this analysis, the New York City Comptroller’s Office and Experian isolated an anonymized sample population of consumers with rents under $2,000 whose rental information is already reported to Experian. The use of a sample population – a representative subset of actual New York City credit reports – allows this report to utilize actual consumer data to estimate how reporting rent payments could give consumers a powerful financial tool to build their credit. Assuming regular, non-delinquent payments of under $2,000 per month made on an ongoing basis by the tenant, the analysis attempts to estimate how rent reporting can help a typical cross section of New York City consumers.[xxxvi]

The analysis within this report is confined to the effect rent has on VantageScores. Other scores, including many FICO credit scores, do not capture rent data and would be unaffected by the proposal outlined within this report. Further discussion on data techniques and research methodology is included within an appendix.

The Comptroller’s analysis found that allowing tenants the ability to have their rent records relayed to credit agencies should they choose would have a tremendous positive impact for the majority of participating New York City renters. Balanced with necessary consumer protections, incorporating rent into credit scores would help lift the economic fortunes of renters across New York City by raising credit scores for consumers across New York. In short, the Comptroller’s analysis found that for a typical New York City consumer paying under $2,000 a month in rent, choosing to report rental history would:

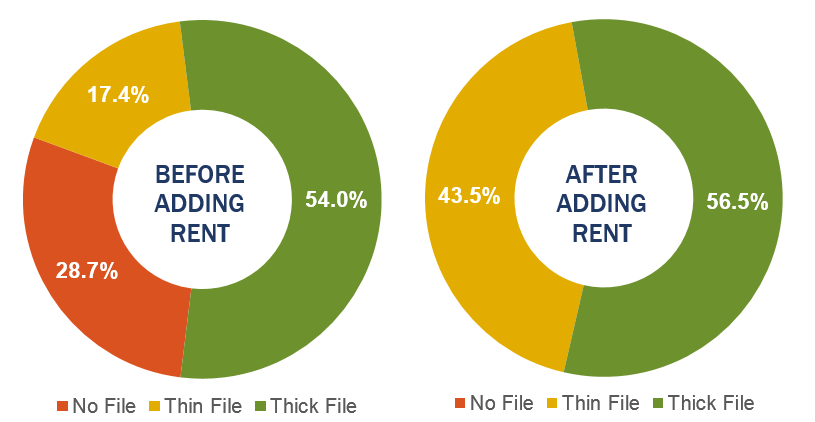

- Grant credit scores to individuals without a credit score or credit history. Within the sample population examined, as many as 28.7 percent of renters gained a credit score for the first time. The average new credit score amounted to 700 points, a prime score. Equipping more New York consumers with a credit score will give more families access to the many financial opportunities and savings associated with an increased credit score.

- Raise credit scores for an estimated 76 percent of New York City tenants who elect to report their rent to credit bureaus, including significant increases of 11 points or more for an estimated 19 percent of participating renters. An additional18 percent of tenants would likely see no material change to their credit score but would gain additional depth to their credit report. A small population of renters, comprising 6 percent of the sample, would see a decline in their scores including 3 percent with declines of 11 points or more.

- Lift credit scores for many of New York’s low-income and minority communities. Within zip codes with a low average credit score of 630 or lower, Black and Hispanic residents account for over 90 percent of the population. Similarly, the average credit score for communities where NYCHA residents comprise one in ten residents is also under 630. These communities would be poised to benefit from an appreciable increase in credit scores.

Getting on the Map: Reaching the Credit Invisible

Despite the necessity of a credit score to fully participate in the consumer economy, an estimated 19.3 percent of Americans lack a credit score, leaving them unable to access common financial tools such as credit cards, a home mortgage, or business loans.[xxxvii]

For many consumers, the addition of a steady stream of rental payments is enough to generate a brand new credit file. Previously ‘invisible’ and ‘unscorable’ consumers would gain a score based off of their rent payments alone, enabling these consumers to benefit from the many opportunities provided by access to the financial system.

The Comptroller’s Office estimates that by choosing to add an ongoing monthly stream of rental payment information to their credit reports, as many as 28.7 percent of the New York City renter population with rents under $2,000 could gain a score for the first time, as is depicted in Chart Eight.

The Effect of Adding Rent Information to Credit Files for New York City Consumers

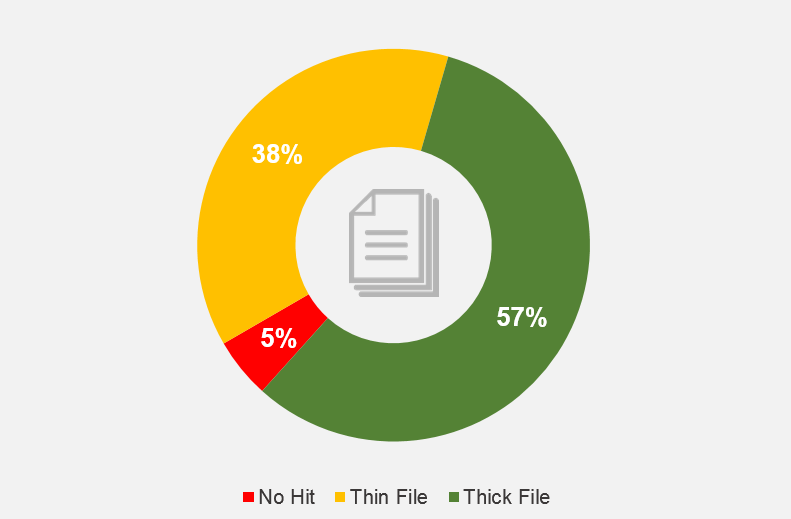

Chart Eight: Percentage of New York City Renters

The inclusion of rent on a credit report would also significantly impact the quantity and quality of information on the credit profiles of consumers with thin files. As noted above, a thin file is a consumer credit record that only includes 0-4 possible components for a credit score and is more at risk of providing a distorted or unrepresentative picture of a consumer’s finances. Some consumer’s files are so thin that a credit score cannot be generated based on the available data. In all, 38 percent of New York City credit scores across the city are derived from thin files as shown below in Chart Nine. Adding rental data would increase the proportion of thick files.

Chart Nine: Porportion of NYC Consumers with No Hit, Thin, and Thick Files

For these New Yorkers, the addition of rental payments to their credit score would either supply the necessary additional data to produce a new VantageScore score or would help improve the accuracy of an existing score.

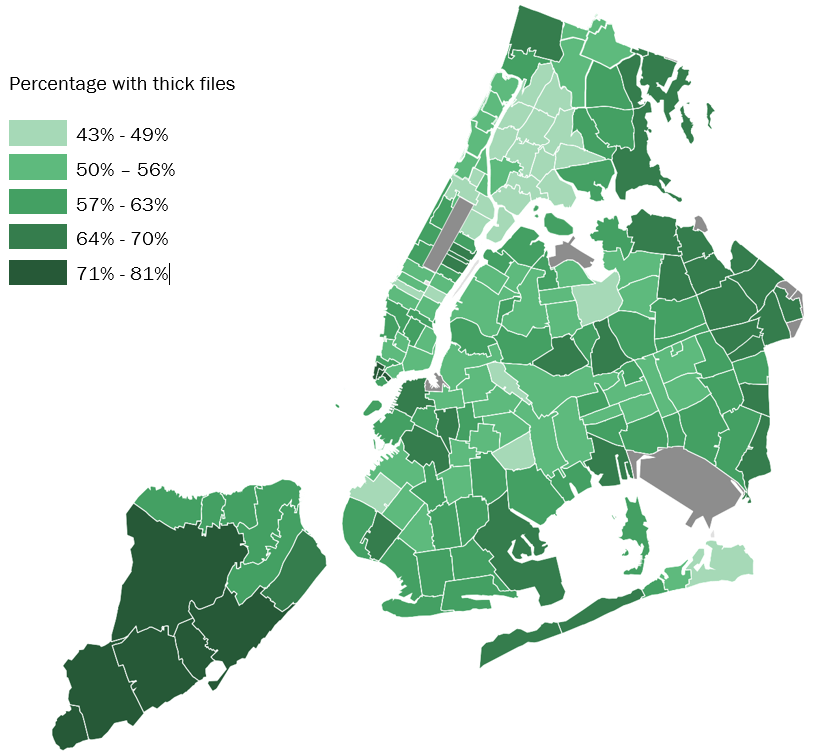

File Thickness

By New York City Zip Codes

Percentage with thick files

The high rate of New Yorkers with thin files, and their concentration within Central Brooklyn and the Bronx, may owe to the relatively low percentage of consumers within the city holding car or home loans, shown in Charts Ten and Eleven below. Both mortgages and auto loans provide regular streams of information to help create thicker credit files which can serve as the basis for stronger, more representative scores.

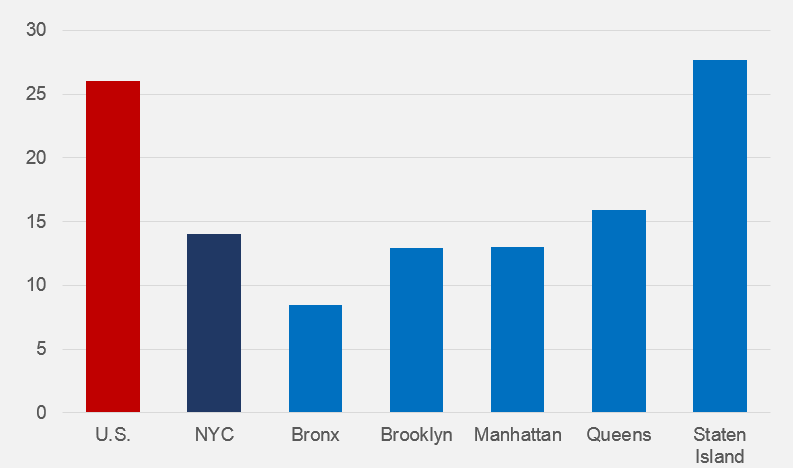

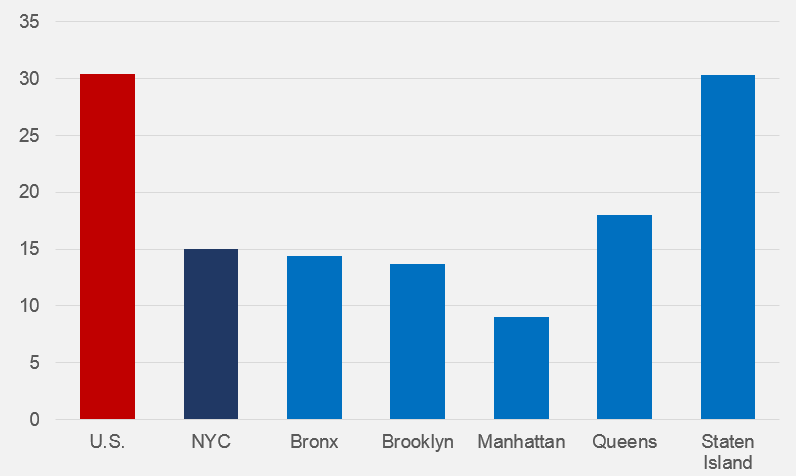

Chart Ten: Percent of All Consumers That Have At Least One Current Mortgage

Chart Eleven: Percent of All Consumers That Have At Least One Current Auto Loan

With only 14 percent of New York City consumers holding an active auto loan and 13 percent of New Yorkers holding an active home mortgage, many consumers are unable to rely on two of the traditional drivers of credit scores.[xxxviii] Homeownership rates within New York City are far enough behind national averages that the Bronx ranks second to last in ownership rates across the entire country.[xxxix] The high number of New Yorkers with a credit score based on thin files underscores the potential benefit of adding more information to credit calculations.

Importantly, many of the currently credit invisible consumers would receive scores on the upper end of the credit spectrum if their rent payments were counted. Of the many tenants who would gain a new score by virtue of their rent records, 98 percent would receive prime scores and two percent would receive nonprime scores, putting them in the top echelon of credit scores. The average score for newly scored consumers amounts to a respectable 700, high enough to secure competitive rates for many consumer loans and credit cards.

Raising Renters: Lifting Credit Scores Through Rent Reporting

Alongside generating new credit scores for an estimated 31 percent of the population, enabling tenants to include their rental payments in their credit report raised VantageScores for 76 percent the sample population, appreciably improving their ability to get ahead in the consumer economy.

Chart Twelve: Percentage of Inidviduals with a Change in Score After Addition of Rental Payments

Chart Twelve depicts how the addition rent payments of $2,000 or less, paid timely and in accordance with a lease, was enough to raise credit scores by 11 or more points for almost one in five consumers. A further 57 percent of tenants who choose to report their rent could anticipate a credit score increase ranging from one to ten points. For 18 percent of the sample population, the addition of rent caused no change to their VantageScore.

While the analysis above is confined to examining the effects of rent reporting on VantageScore and on Experian credit reports, an increasing number of credit scoring models are beginning to include rent within their scoring models. For instance, alongside VantageScore, the FICO 9 credit score also incorporates rent information.[xl] Even if rent information cannot be expected to lift all credit score models, the inclusion of data is still enough to put consumers on the map.

Indeed, studies have confirmed that rent information has been of particular benefit to renters with sub-prime or non-prime scores. According to a 2014 TransUnion analysis, the approximately eight in ten American consumers with VantageScore 2.0 scores of lower than 641 saw an increase in their score just one month after reporting. Those results confirm many of the findings within this report, suggesting that rent reporting can potentially catapult many of these New Yorkers into lower interest rates and greater economic opportunity.[xli]

This analysis of rent and credit data does show that the addition of rent information to credit reports, even exclusively positive rent information, would result in a score decrease for a relatively small proportion of consumers. Three percent of the population would see their score drop by one to ten points. A further three percent could see their score drop by eleven points or more. The drop in scores among this population may be attributable to the effect the inclusion of rent would have to the calculation of their total debt-to-credit ratio. For the purposes of credit scoring, rent is typically classified as a monthly debt similar to other fixed debts like a monthly credit card bill. In some cases, the addition of further monthly debt in the form of a rent payment could push an individual’s debt to credit ratio past ideal portions, resulting in a score decrease.[xlii]

However, despite the exact score, a thicker file with a more diversified array of tradelines may help provide a more nuanced picture of an individual’s credit worthiness than is conveyed in their numerical credit score. The inclusion of rent on a credit report may also be helpful for prospective tenants on the hunt for a new lease.

These results align with the findings of a study conducted by the Credit Builder’s Alliance which examined how a pilot of rent reporting at eight affordable housing providers lifted the scores of low income residents.[xliii] According to their study, 79 percent of residents within the pilot saw an increase to their credit score. Their study is a clear demonstration of how rent reporting can work to help residents of affordable housing.

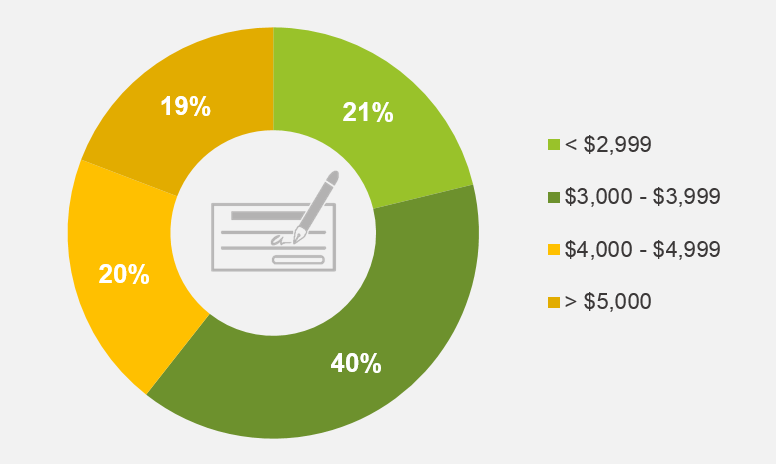

The same score dynamics present in an analysis of New York City renters paying under $2,000 per month also holds true for a wider cross-section of tenants. An examination of a wider sample of consumers, with a distribution of rent payments shown in Chart Thirteen, showed similar results.

Chart Thirteen: Rent Payments for Expanded Higher Rent Consumer Sample

Among this sample population, 31 percent of consumers gained a new score, averaging 674. Of individuals with credit scores, 61 percent saw improvements to their scores, 26 percent of individuals in this population saw no change in their score, and a slightly higher proportion of the population would potentially see a decrease in their score, likely due to the addition of high rent payments to a consumer’s estimated debt load. These results suggest that the benefits of rent reporting stretch across New York’s tenant population.

Notably, these results do not estimate any potential effects resulting from the delinquent or nonpayment of rent by a tenant. Falling behind on rent would almost certainly harm a tenant’s credit score, just as would defaulting on a loan or missing a mortgage payment. The negative impact of a missed payment on a score varies by credit bureau and by score. While this is an appreciable risk which every tenant should consider before opting in to a rent reporting agreement, currently delinquent renters already can be brought to the notice of credit bureaus by landlords or debt collectors and have their scores decline. Due to limitations in available data, this report is unable to estimate the potential negative effects of a late payment.[xliv]

However, tenants opting to report their rent should be aware of the possible negative effects resulting from a missed payment. Giving more renters the option of having their rent history put towards raising their credit score is not expected to have a significant effect on the frequency of renters already experiencing negative outcomes.

Reaching New Yorkers Across Race, Income and Geography

To estimate the impact of rent reporting across New York City communities, the Comptroller’s office conducted a study of existing credit score patterns and dynamics within the five boroughs. Drawing on Experian’s sample of consumer profiles, this analysis shows deep inequities in credit scores across New York City neighborhoods.

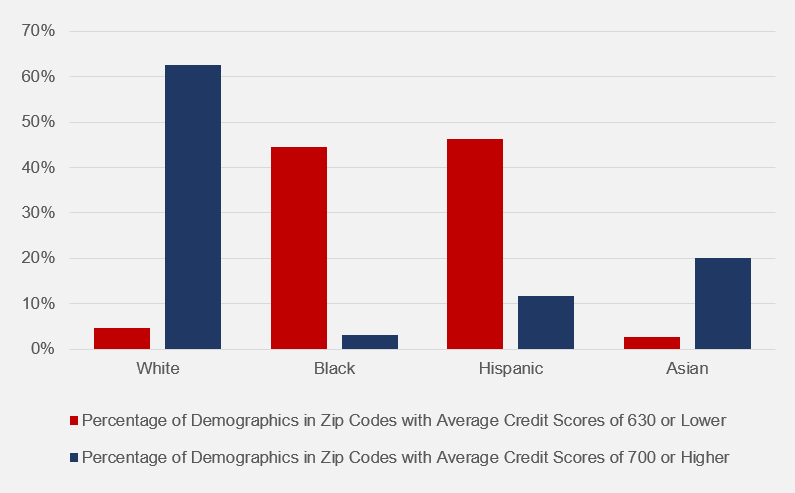

Race

The addition of rent to credit reports has the potential to be of particular benefit to communities of color. In zip codes where the average credit score is below 630 and where the effects of rent reporting would be most felt, Black and Hispanic residents account for over 90 percent of the population. In contrast, in zip codes where the mean credit score is above 700, Black and Hispanic residents only account for 15 percent of the population.

Chart Fourteen: Racial Composition of New York City Zip Codes by Average Credit Scores

A deep racial divide in credit scores nationally, similar to the evidence within New York City, has been documented by others. In 2007, The Federal Reserve Board delivered a report to Congress alleging that according to their model, the mean credit score of Black consumers was approximately half of White, non-Hispanic consumers.[xlv] A later study by the Woodstock Institute analyzing credit scores within Illinois found “sharp disparities in credit characteristics between communities of color and white communities.”[xlvi] In combination, these studies strongly suggest communities of color face significant obstacles in maintaining a strong credit score and accessing affordable credit.

Income

Low-income communities could also expect to benefit from the addition of new, positive information to their credit report. According to the sample of New York City credit characteristics provided by Experian, mean wage income is directly correlated with the strength of a consumer’s credit score. Within zip codes with a mean credit score below 630, the level of annual income estimated by Experian is $34,475. In zip codes with a mean credit score above 700, mean wage income as estimated by Experian sits at a much higher $52,528.

Geography

Adding rent data to credit reports would significantly benefit areas in the interior of Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx, where zip codes with low mean credit scores overlap with communities with a high population of renters.

Rent reporting could have a pronouced effect in neighborhoods where over 45 percent of residents hold subprime credit scores, such as Morrisania, East New York, the Rockaways, and Central Harlem. Similarly, reisdents of areas where over 40 percent of the poulation hold ‘thin’ credit files would be especially likely to see an increase in the number of residents with scores and in the accuracy of scores. Neighborhoods in this category include Morningside Heights, Brownsville, Flushing, or Borough Park.

Tenant Profiles: Impact of Adding Rent to Credit History

To demonstrate the potentially transformative impact of rent reporting, this report presents three case studies showing how actual New Yorkers would benefit from adding rent to their credit history. Each case study profiles an anonymized tenant living within the five boroughs.

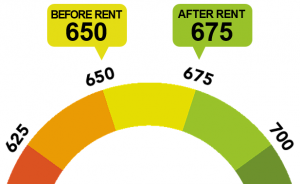

Tenant A

Consumer with a Limited Credit History

Tenant A regularly pays a monthly rent of $1,300, slightly lower than the median average rent within New York City. Before the addition of rental information, Tenant A holds a credit score of 650, a healthy score though below the average credit score for New York City residents. Currently, Consumer A’s credit file consists of only one tradeline, a credit card with a fairly low credit limit.

With the addition of Consumer A’s rent history, her score would rise by 25 points to 675, catapulting her from a non-prime credit risk segment into the prime segment. This change in credit score could materially change Consumer A’s financial wellbeing by giving her new economic opportunities and reaping large cumulative savings over a lifetime.

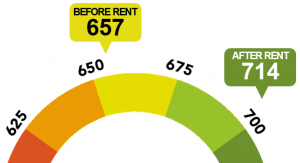

Tenant B

Consumer with a Low Credit Score

Tenant B has a limited credit history to her name, perhaps having just graduated from college and begun work. She is an authorized user on a family member’s bank credit card and utilizes a credit card with a low credit limit of $800. Both accounts have been opened for less than 18 months and her score of 657 reflects this limited history.

Tenant B, like many young New Yorkers, may have arrived to New York City without a substantial history of using credit. By adding rental information to her currently thin credit file, Tenant B would see her score rise by 57 points, moving her score into the prime category. With a higher credit score, Tenant B could potentially refinance a student loan or qualify for a cheaper cellphone plan, helping her gain a financial foothold in the city.

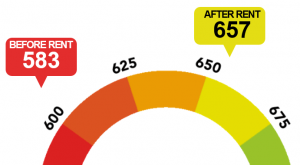

Tenant C

Young Arrival to the City

Tenant C’s credit history is marred by two late payments made during a four year history with a credit card issued by his bank. As a result, his credit score of 583 places him in the subprime credit tier. With a subprime score, Tenant C may pay more for common financial services or struggle to qualify for loans or financial products.

Adding an ongoing rental payment to Tenant C’s credit profile lift his score by a substantial amount to 657. Equipped with an improved VantageScore, Tenant C could gain new access to cheaper financial products.

Giving Renters Credit: Proposals to Enhance Credit Scores

Allowing tenants to further benefit from their monthly rent check would lift the financial fortunes of New York City’s millions of renters. The following recommendations aim to provide more tenants with the opportunity to improve and protect their credit score.

Tenants should be empowered to report their rental history towards credit bureaus. Landlords, banks, credit unions, credit bureaus, financial counselors, and third party reporting companies can assist consumers through existing programs and models and by innovating new ways to report rent and boost credit.

While an analysis of existing rental reporting data clearly demonstrates that the majority of New York City renters would reap a real benefit from having their rent checks count towards their credit scores, very few credit scores actually include rent information. The vast majority of credit scores held by New York City residents do not currently factor in rent information. Making rent reporting more available to tenants can potentially transform the landscape of credit within New York City.

To facilitate the incorporation of rent data into credit scores for willing renters, various parties should converge to develop creative strategies to give tenants more credit for their rent.

Landlords and property managers, who are well equipped to help tenants report rent information, should seek to offer their tenants the chance to opt-in to a program that would allow landlords to relay the receipt of payments to any company that collects rental data. Landlords interested in facilitating the transfer of rent data on the behalf of tenants can draw on a number of available tools and resources to do so. Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion accept rental information directly from landlords. While landlords are obligated to fairly and accurately pass on consumer data, abiding by all existing credit reporting laws, regulations, and best practices, reporting data is not overly onerous or costly.

In exchange for giving tenants the ability to choose to have rent incorporated into their credit history, landlords would share in a number of benefits offered by rent reporting. Offering credit reporting services could be advertised as an amenity by landlords seeking to gain an edge in New York City’s competitive real estate market. Mission-oriented landlords, such as managers of affordable housing units, can give their tenants the opportunity to substantially lift their credit scores. The City can also potentially experiment with giving landlords additional incentive to report rent, such as providing a small credit on property taxes.

The City should also explore incorporating rent reporting into its affordable housing programs. The New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) administers a number of financing programs aimed at building and preserving affordable housing. The City should inform developers utilizing its many programs, including the Extremely Low and Low-Income Affordability Program, the Mixed Income program, the Mixed Middle Income program, and other housing initiatives about the potential benefits of implementing a rent reporting program. Other types of organizations, including banks and credit unions, should also explore offering renters the ability to forward their rental histories to credit bureaus. By innovating new services that forward rent information to credit bureaus on behalf of renters, banks and credit unions could potentially gain new consumers interested in improving their credit. Banks, credit unions, and other financial institutions are already proficient in navigating the complex regulatory environment that surrounds credit reporting, making them well positioned to develop a product that could reach new consumers and markets.

There are several potential models that banks and credit unions can draw on to develop a viable rent reporting product. A bank or credit union could identify electronic rent payments from tenant to landlord as rent payments and report them to a credit bureau at the request of the tenant. A bank could also serve as an intermediary or go-between by accepting a check from a tenant, verifying it against a lease, remitting payment to the landlord, and reporting the transaction to a credit bureau.

Credit unions and banks could also experiment with offering a microloan program. Banks would pay a tenant’s rent in advance to a landlord, either in yearly, quarterly, or monthly increments. Tenants would be responsible for paying off their loan to the bank, plus a nominal fee. The bank could then report the transaction as a standard loan, which if paid in full would provide a boost to a tenant’s credit history.

New York City tenants should also examine an emerging market of third party rent reporting companies, many of them online. These companies act as intermediaries between renters and landlords. Renters can send their monthly rent check to the third party, which then verifies the rent against the tenant’s lease, and forwards payments to the landlord and information to credit bureaus. By shouldering the legal responsibility for rent reporting, these organizations relieve landlords of any hardship of having to comply with the Fair Credit Reporting Act and give tenants with disinterested landlords the chance to have rent included on their credit report. Landlords can also work with third part data furnishers to develop convenient ways of submitting payments.

Lastly, credit bureaus should explore ways to better facilitate rent reporting from a wider segment of the renter population. By simplifying reporting mechanics, working with large property managers to integrate into existing housing management systems, or reaching out to smaller landlords on the behalf of interested tenants, credit bureaus can make the process of rent reporting as simple as possible.

Landlords, third party reporters, and financial institutions should each seek to develop and scale new programs to report rent data on the behalf of interested renters. Tenants, in consultation with financial advisors and housing advocates, should carefully research and consider these services as a way to increase their credit scores and gain access to lower cost financial services and opportunities.

Credit scores incorporating rent should be more widely considered by mortgage lenders and other parties.

Though an increasing number of credit scoring models now factor in rent information, including the VantageScore and the FICO 9 score, many credit scores will not change as a result of reported rent data (though rent information could still contribute to a longer credit report). The Comptroller urges more organizations to consider credit scoring models which utilize rent data to give a fuller, more accurate account of the creditworthiness of renters.

The Comptroller also supports federal legislation allowing more mortgage lenders to utilize a more diverse range of credit scores, including those that incorporate rent. Currently, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the nation’s largest mortgage investors, will typically only purchase mortgages from lenders who underwrite mortgages using older versions of FICO’s scoring model.[xlvii] These restrictive guidelines effectively bar local banks from considering other credit scores. A bipartisan bill introduced in the United States House of Representatives would permit both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to consider adding new scoring models to their underwriting criteria.[xlviii] Should this bill be signed into law, more renters would be empowered to make home purchases on the strength of their records of diligently paying rent.

NYCHA should scale up a program to furnish rental information on behalf of interested tenants, with the goal of boosting credit scores for public housing residents.

Given that residents of affordable housing are often best positioned to benefit from the process of rent reporting, NYCHA should continue and expand programs allowing residents to share their rent information with a credit bureau. According to an Experian study, 65 percent of renters receiving housing subsidies hold subprime credit scores, which could improve drastically from the addition of rental trade lines.[xlix] NYCHA, home to nearly 400,000 New Yorkers, could help fulfill its mission to “increase opportunities for low- and moderate-income New Yorkers” by promoting the potential benefits of rent reporting.[l]

NYCHA is currently conducting an innovative pilot partnership with two credit unions, Brooklyn Cooperative Federal Credit Union and Urban Upbound Federal Credit Union, to give NYCHA residents access to credit building devices. The program offers enormous promise for NYCHA residents. NYCHA should closely monitor the success of the program, report on outcomes, and seek to bring its benefits to NYCHA buildings across the five boroughs.

Rent data gathered during a pending housing court case should not be incorporated into a credit score.

The City should pass legislation that forbids landlords from reporting the withholding of rent while a dispute is being contested in housing court. In some cases, landlords may seek to use credit reporting mechanisms to retaliate against tenants who are legally withholding rent payments during a court dispute. By not allowing credit scores to be collected while a housing dispute is ongoing, the City could help safeguard tenants from unscrupulous landlords misusing their powers to report rent.

In addition to consumer protections advanced through legislation, the Fair Credit Reporting Act grants consumers the right to dispute any inaccurate information directly with the credit bureau.[li] When assessing consumer disputes, credit bureaus must be cognizant of the laws governing New York City housing, including a tenant’s right to withhold all or a portion of rent if a landlord is in breach of any laws or regulations as determined by housing court or the New York State Division of Housing and Community Renewal.[lii]

Credit checks for the purpose of securing an apartment should not impact a consumer’s credit score.

The City should also encourage the private sector to help renters in other ways. Many consumers are unaware that even credit score inquiries can impact their credit. Typically, when a consumer applies for any service that involves a credit check, including credit checks conducted by landlords, the inquiry has a slight negative effect on a consumer’s credit score. Inquiries that produce this negative effect are termed ‘hard inquiries.’ In New York’s competitive housing marketplace, a prospective applicant could apply for multiple apartments and see their credit rating decline just at the moment it is being scrutinized by landlords. Unlike credit card or auto loan applications, the volume of inquiries used to assess an applicant for housing cannot be said to hold any informational value for creditors. Therefore, credit score models should be adjusted to mitigate any potential harm to consumers by classifying all housing related credit inquiries as ‘soft inquiries,’ which do not count against your credit score. Many of the major credit bureaus maintain that they have already developed safeguards against a renter being penalized for a credit check, but by entirely eliminating any negative effect stemming from a credit check consumers could be sure that their credit score is not impacted at the moment they need it most.

Congress should extend existing consumer protections concerning the reporting of late payments to rent reporting.

Under the terms of the Fair Credit Reporting Act and the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act (CARD Act), an account is only deemed delinquent when it is unpaid thirty days after the credit is due. These regulations prevent customers from being unduly penalized for payments that are not overly late.

Currently, these protections only extend to customers using credit cards. While credit bureaus purport to extend the same timeframe to rental agreements, these rules should be formalized. Congress should amend existing acts or create new legislation to apply the same definition of late to rent and utility reporting.

Any landlord or leasing agent requesting an application fee to cover the cost of a credit check should be required to share the credit report with the applicant, regardless of whether a lease is signed.

Given the importance of credit, the City should also explore ways to give New York consumers more insight into their credit records. While consumers can currently request a yearly free credit report from each of the major three bureaus, they are not guaranteed free access to credit scoring models more typically used by landlords. Often, leasing companies and building management will purchase more comprehensive credit reports and pass the cost on to the applicant. The City should pass a law requiring leasing companies and landlords to share any credit reports or a digestible summary of credit reports they access with the potential renter. Consumers would gain additional insight into their credit history and would get more value back for their application fee, without costing the landlord or leasing company any additional dollars.

New York City should seek to bolster financial education and financial literacy initiatives educating consumers about credit issues, particularly about the potential effect of rent reporting on credit scores.

The City should also expand financial counselling services alongside any effort to encourage rent reporting. Currently, the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs partners with community organizations to operate Financial Empowerment Centers across the five boroughs. These Centers already provide trusted advice on housing matters to New York City residents and their programs have been widely lauded for their quality and scope. By providing individualized advice to tenants on the prospect of using rent to improve credit scores, the Financial Empowerment Centers and other housing advocate organizations can help consumers make informed choices.

Various service providers, nonprofit community groups, and credit unions offer counseling to help consumers build or recover credit. The New York Public Library offers a successful credit crisis counseling program with the Financial Coaching Corp of the Community Service Society of NY or the Financial Planning Association of NY. Programs like these should be expanded and should incorporate discussion of the possible impact of rent reporting.

Conclusion: Making Rent Count

For many within New York, their monthly rent check grants them access to a home in the world’s greatest city. However, New Yorkers can derive much more value from their rental payments if given the opportunity to have those payments counted towards their credit score. Expanding access to innovative programs that report rent, accompanied by strong consumer protections, will raise the credit scores of thousands of New York City renters, granting them new opportunities and greater financial security. A credit score can be the deciding factor between being denied a loan or securing a good rate, having a rental application rejected or put to the top of the pile, securing a mortgage for a first home or paying more for common services. Lifting people’s credit scores raises their financial futures and giving renters the ability to have their hard earned rent check lift their credit scores can change the future for renters across the five boroughs.

Appendix I: Methodology

To prepare this report, the New York City Comptroller’s Office contacted Experian, a large credit bureau with an expertise in rent reporting. Though Experian shared data and preliminary analysis with the Comptroller’s Office, the analysis and conclusions presented within this report are uninfluenced by Experian and are solely those of the New York City Comptroller’s Office. Experian reserved the right to review the report before publication to ensure the accuracy of the data presented.

To estimate the potential benefits of adding rent information, this report draws from two samples of New York City consumers. These samples include a subset of New York City based consumer files within Experian’s database which included rent information. From an initial sample of 17,000 files, the data was separated into a group including consumers with a cross section of rents, with a sample size of 17,721, and a group including only consumers paying less than $2,000 in rent per month, with a sample size of 506 tenants. That sub $2,000 sample attempts to approximate the financial circumstances of a ‘typical’ New York City renter. In this subset, the average rent amounted to $820, less than the $1,317 average rent within New York City but within the same range. As noted in the report, similar effects were observed in a sample population inclusive of higher rents. The study’s sample size, though small, is judged to have sufficient statistical weight to support the conclusions of the study, especially given the known contribution of rent information in the VantageScore model. Using actual consumer data, rather than a simulated rent tradeline, allows the study to better estimate the actual effects of rent reporting.

After determining certain characteristics of the sample populations, each consumer record was scored with and without rental information. By comparing changes in scores, the Comptroller’s Office was able to project how the inclusion of rent would impact credit scores.

In addition to the macro level data and analysis presented within this report, individual anonymized profiles were also selected to provide a detailed, granular explanation of how rent reporting impacts consumers. Each profile featured in the report is sourced from the actual credit file of a New York City tenant living within the five boroughs.

Appendix II: Borough Maps of Credit Scores (2016)

Brooklyn

The Bronx

Manhattan

Queens

Staten Island

Acknowledgements

Comptroller Scott M. Stringer thanks Nichols Silbersack, Senior Research Analyst, the lead writer of this report. The Comptroller also extends his thanks to David Saltonstall, Assistant Comptroller for Policy.

The Comptroller also thanks Experian for their provision of proprietary data.

Comptroller Stringer recognizes the important contributions to this report made by:

Zachary Schechter-Steinberg, Deputy Policy Director; Brian Cook, Assistant Comptroller for Economic Development; Tyrone Stevens, Press Secretary; Jack Sterne, Senior Press Officer; Devon Puglia, Director of Communications; Nicole Jacoby, First Deputy General Counsel; Lena Bell, Associate Director of Special Projects; Jennifer Conovitz, Special Counsel to First Deputy Comptroller; Archer Hutchinson, Web Developer and Graphic Designer; Nicholas Shatan, Intern; Sascha Owen, Chief of Staff; and Alaina Gilligo, First Deputy Comptroller.

Endnotes

[i] Some estimates peg the rent-to-income ratio for average New Yorkers as over 65%. New York City Comptroller, ‘The Growing Gap: New York City’s Housing Affordability Challenge’: http://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/Growing_Gap.pdf and NBC New York, ‘Typical NYC Household Spends 2/3 Of Income on Rent’: http://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/local/NYC-New-Yorkers-Spend-Nearly-23-of-Income-on-Rent-in-2016-StreetEasy-376497101.html

[ii] They Made America, ‘Lewis Tappan’, Corporation for Public Broadcasting: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/theymadeamerica/whomade/tappan_hi.html

[iii] Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, ‘Key Dimensions and Processes in the U.S. Credit Reporting System: A Review of How the Nation’s Largest Credit Bureaus Manage Consumer Data’: http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201212_cfpb_credit-reporting-white-paper.pdf

[iv] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, ‘Credit Reports and Credit Scores’: https://www.federalreserve.gov/creditreports/pdf/credit_reports_scores_2.pdf

[v] Susan Johnston Taylor, ‘A Guide to Credit Scoring Models’, U.S. News and World Report: http://money.usnews.com/money/personal-finance/articles/2015/01/06/a-guide-to-credit-scoring-models and The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, ‘The Impact of Differences Between Consumer and Creditor Purchased Credit Scores’, http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/2011/07/Report_20110719_CreditScores.pdf

[vi] VantageScore 3.0 is a collaboration between Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion, who developed the model to allow for more uniformity in scores across different credit bureaus.

[vii] VantageScore: https://www.vantagescore.com/

[viii] The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, ‘Data Point: Credit Invisibles’: http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb_data-point-credit-invisibles.pdf

[ix] The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, ‘Data Point: Credit Invisibles’: http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb_data-point-credit-invisibles.pdf

[x] The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, ‘New York City Community Credit Profile’: https://s3.amazonaws.com/files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_credit-profiles_handout_New-York-City.pdf

[xi] Kenneth P. Brevoort, Philipp Grimm, and Michelle Kambara, ‘Credit Invisibles and the Unscored’, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/cityscpe/vol18num2/ch1.pdf

[xii] The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, ‘Data Point: Credit Invisibles’: http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb_data-point-credit-invisibles.pdf

[xiii] The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, ‘Data Point: Credit Invisibles’: http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb_data-point-credit-invisibles.pdf

[xiv][xiv] James Baldwin, ‘The Price of the Ticket’: http://books.google.com/books/about/The_Price_of_the_Ticket.html?id=dsauteQRd7UC

[xv] http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/17/realestate/prospective-renters-have-much-to-prove-to-landlords.html

[xvi] The Real Estate Board of New York, ‘New York City Residential Sales Report First Quarter 2017’: https://www.rebny.com/content/dam/rebny/Documents/PDF/News/Research/NYC%20Residential%20Sales/REBNY_1Q_2017_Residential_Sales_Report.pdf?

[xvii] These figures are calculated using a FICO data application drawing on average mortgages indicators from thousands of lenders. Calculations assume no down payment. The interest rates are current as of 10/01/2016. FICO, ‘Loan Savings Calculator’: http://www.myfico.com/crediteducation/calculators/loanrates.aspx

[xviii] FICO, ‘Loan Savings Calculator’: http://www.myfico.com/crediteducation/calculators/loanrates.aspx

[xix] These figures are calculated using a FICO data application drawing on average car loan indicators from thousands of lenders. The interest rates are current as of 10/01/2016. FICO, ‘Loan Savings Calculator’: http://www.myfico.com/crediteducation/calculators/loanrates.aspx

[xx] National Association of Insurance Commissioners, ‘Credit-Based Insurance Scores: How an Insurance Company Can Use Your Credit to Determine Your Premium’: http://www.naic.org/documents/consumer_alert_credit_based_insurance_scores.htm

[xxi] Nick DiUllo, ‘If You Have Poor Credit, You May Pay nearly Double For Home Insurance’, Insurance Quotes: http://www.insurancequotes.com/home/home-insurance-and-credit

[xxii] Consumer Reports, ‘The Secret Score Behind Your Rates’, http://www.consumerreports.org/cro/car-insurance/credit-scores-affect-auto-insurance-rates/index.htm

[xxiii] Federal Reserve Bank of New York, ‘Recent Developments in Consumer Credit Card Borrowing’, Liberty Street Economics: http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/08/just-released-recent-developments-in-consumer-credit-card-borrowing.html

[xxiv] Chi Chi Wu, Credit Invisibility and Alternative Data: The Devil is in the Details’, National Consumer Law Center: https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/credit_reports/ib-credit-invisible-june2015.pdf

[xxv] The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, ‘Data Point: Credit Invisibles’: http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb_data-point-credit-invisibles.pdf

[xxvi] https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2011/07/15/2011-17649/fair-credit-reporting-risk-based-pricing-regulations

[xxvii] Federal Reserve System and the Federal Trade Commission, ‘Fair Credit Reporting Risk-Based Pricing Regulations’, Federal Register: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/blogs/business-blog/2015/10/ftc-calls-sprint-29-million-risk-based-pricing-violation

[xxviii] Jose Pagliery, ‘T-Mobile Days Bad Credit Means Half of Consumers Don’t Quality for Deals’, CNN: http://money.cnn.com/2015/01/22/technology/mobile/tmobile-credit/

[xxix] Federal Trade Commission, ‘Consumer Information’: https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/articles/0220-utility-services

[xxx] This analysis draws on a statistically valid sample maintained by Experian of credit scores sorted by zip codes.

[xxxi] All data cited within this section is current as of 2016.

[xxxii] www.comptroller.nyc.gov

[xxxiii] Teddy Nykeil, ‘Does Having a Mortgage Improve My Credit Score’, NerdWallet: https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/finance/mortgage-credit-report-improve-credit-score/ and Equifax, Does Paying Off My Mortgage Affect My Credit Score’: http://blog.equifax.com/credit/does-paying-off-my-mortgage-affect-my-credit-score/

[xxxiv] Elyzabeth Gaumer and Sheree West of the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, ‘Selected Initial Findings of the 2014 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey’: http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/hpd/downloads/pdf/2014-HVS-initial-Findings.pdf and Bureau of Labor Statistics, ‘Consumer Expenditures for the New York Area: 2013-14’: http://www.bls.gov/regions/new-york-new-jersey/news-release/consumerexpenditures_newyorkarea.htm

[xxxv] Elyzabeth Gaumer and Sheree West of the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, ‘Selected Initial Findings of the 2014 New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey’: http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/hpd/downloads/pdf/2014-HVS-initial-Findings.pdf and Bureau of Labor Statistics, ‘Consumer Expenditures for the New York Area: 2013-14’: http://www.bls.gov/regions/new-york-new-jersey/news-release/consumerexpenditures_newyorkarea.htm

[xxxvi] Experian includes only positive, paid-as-agreed rent information reported to Experian RentBureau in Experian credit reports.

[xxxvii] The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, ‘Data Point: Credit Invisibles’: http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb_data-point-credit-invisibles.pdf

[xxxviii] Federal Reserve Bank of New York, ‘Recent Developments in Consumer Credit Card Borrowing’, Liberty Street Economics: http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/08/just-released-recent-developments-in-consumer-credit-card-borrowing.html

[xxxix] Mark Willis, Maxwell Austensen, Shannon Moriarty, Stephanie Rosoff, Traci Sanders, ‘NYU Furman Center / Citi Report on Homeownership and Opportunity in New York City’, NYU Furman Center: http://furmancenter.org/homeownershipopportunityNYC/keyfindings and http://furmancenter.org/files/NYUFurmanCenterCiti_HomeownershipOpportunityNYC_AUG_2016.pdf

[xl] Lauren Gensler, ‘Who’s Your Landlord? Rent Increasingly Being Factored Into Credit Scores, But Not For Everybody’, Forbes: http://www.forbes.com/sites/laurengensler/2015/11/20/rent-reporting-credit-score/#407f8a9b4312

[xli] TransUnion, ‘TransUnion Analysis Finds Reporting of Rental Payments Could Benefit Renters in Just One Month’: http://newsroom.transunion.com/transunion-analysis-finds-reporting-of-rental-payments-could-benefit-renters-in-just-one-month

[xlii] Adding a new source of information to a credit file may also have an impact on a credit bureau’s estimation of the length of a specific customer’s credit history. If a new tradeline lowers the average age of the contents of an individual’s credit file, it could negatively impact a score. Fortunately, continuing to add rental payments over an extended period could mitigate against any potential negative effect.

[xliii] Credit Builders Alliance, ‘The Power of Rent Reporting Pilot’: https://www.creditbuildersalliance.org/download/3482/

[xliv] Data limitations restrict the ability to track the effect of missed rent payments upon credit scores. Typically, when a tenant becomes delinquent in paying their rent, a landlord will seek to privately resolve the situation or bring the tenant to court. However, if rent goes unpaid, landlords will pass debts off to a collections agency, who will report the outstanding debt to a credit bureau. While the report of any debt under collection will negatively impact a credit report, the collection’s agency will not necessarily label the collections case as a rent case, making it difficult to track. Consumers should be aware that failure to pay their rent according to the terms of their contract can negatively impact credit scores.

[xlv] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, ‘Report to the Congress on Credit Scoring and Its Effects on the Availability and Affordability of Credit’: http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/rptcongress/creditscore/creditscore.pdf

[xlvi] Woodstock Institute, ‘Bridging the Gap: Credit Scores and Economic Opportunity in Illinois Communities of Color’: http://www.woodstockinst.org/sites/default/files/attachments/bridgingthegapcreditscores_sept2010_smithduda.pdf

[xlvii] Fannie Mae, ‘B3-5.1-01: General Requirements for Credit Scores (08/30/2016)’: https://www.fanniemae.com/content/guide/selling/b3/5.1/01.html

[xlviii] United States House of Representatives, ‘H.R.4211 – Credit Score Competition Act of 2017’: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/898/cosponsors?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22Credit+Score+Competition+Act%22%5D%7D&r=3

[xlix] Experian RentBureau, ‘Credit for Renting: The Impact of Positive Rent Reporting on Subsidized Housing Residents’: http://www.experian.com/assets/rentbureau/white-papers/experian-rentbureau-credit-for-rent-analysis.pdf

[l] The New York City Housing Authority, ‘About NYCHA’: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/nycha/about/about-nycha.page

[li] Fair Credit Reporting Act (September 2012): https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/articles/pdf/pdf-0111-fair-credit-reporting-act.pdf

[lii] New York City Rent Guidelines Board, ‘DHCR Fact Sheets’: http://www.nycrgb.org/html/resources/dhcrfact.html and Eric T. Schneiderman, ‘Tenants’ Rights Guide’: http://www.ag.ny.gov/sites/default/files/pdfs/publications/Tenants_Rights.pdf