Making the Grade 2018

Executive Summary

Minority- and women-owned business enterprises (M/WBEs) are critical to the country’s job market, employing millions of Americans and contributing more than $1 billion to the national economy each day.[i] Nevertheless, these businesses continue to confront disparities that deny them the opportunity to compete on a level playing field. In New York City, people of color and women account for 84 percent of the population and 64 percent of business owners.[ii] The City’s recently published disparity study showed that while more M/WBEs are available to contract with the City, there was persistent underutilization of these firms in the last six years of City contracting.[iii] New York City’s M/WBE program is governed by Local Law 1 of 2013, which sets participation goals for minority groups on certain City contracts across four industries: professional services, standard services, goods less than $100,000, and construction. The de Blasio Administration has taken a number of steps in recent years to help the City meet these participation goals, including setting an ambitious goal of increasing contracting with M/WBEs to 30 percent of the dollar value of contracts awarded by 2021.[iv] Since 2014, the Office of New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer has issued an annual evaluation of the performance of the City’s M/WBE program and made recommendations for its improvement. This report builds on that work by further exploring the question of whether the City is on track to meet its aspirations of diversity and inclusion in public contracting. Grades are based on actual spending within FY 2018, rather than the value of contracts awarded during the fiscal year, because contract awards may or may not result in M/WBEs actually receiving payments from the City. This report finds that while the City has increased its spending with M/WBEs, the City continues to fall short on M/WBE utilization in relation to Local Law 1 goals. Key findings include:

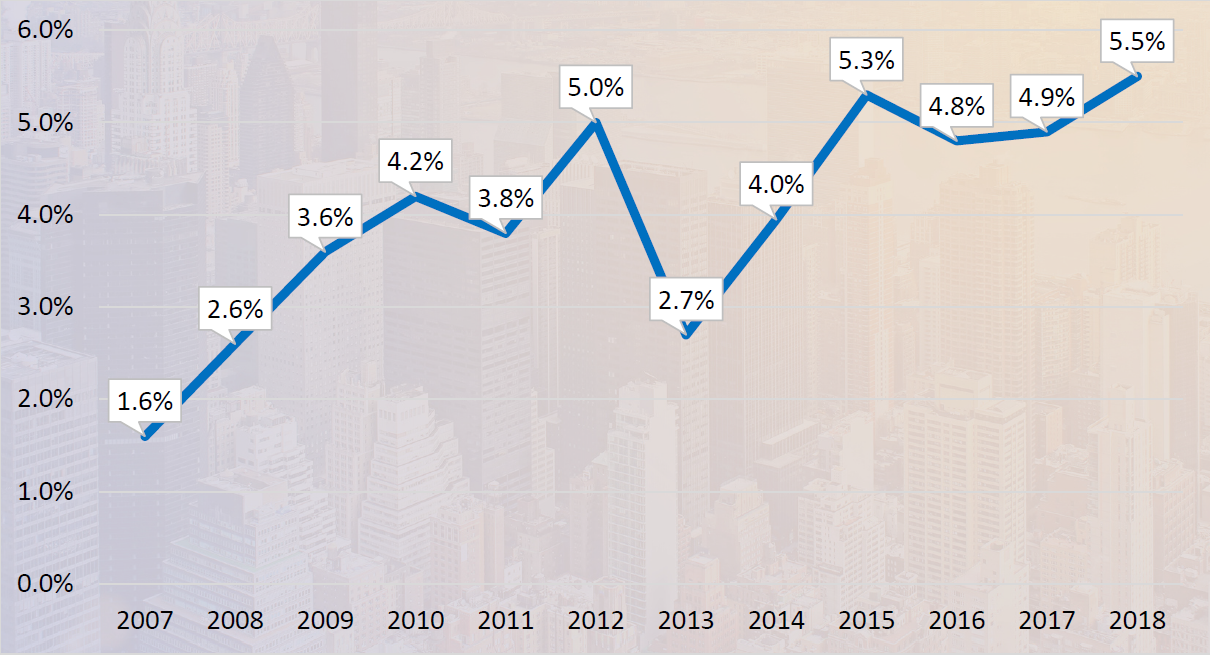

- The City awarded $19.3 billion in contracts in Fiscal Year (FY) 2018, of which $1 billion (equal to 5.5 percent) were awarded to M/WBEs.[v]

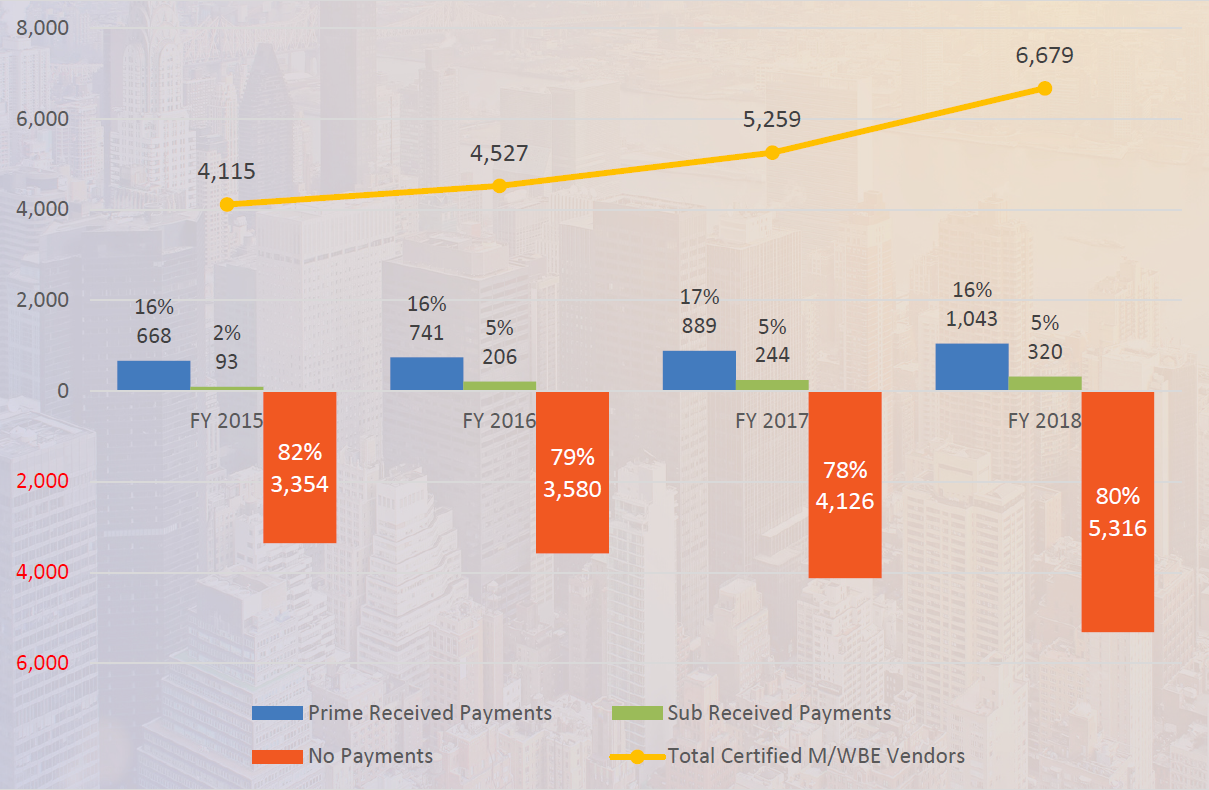

- 20 percent of certified M/WBEs received City payments in FY 2018, a slight decrease from 22 percent of M/WBEs in FY 2017.

- The City spent $731.1 million with M/WBEs in FY 2018, up from $554 million in FY 2017.

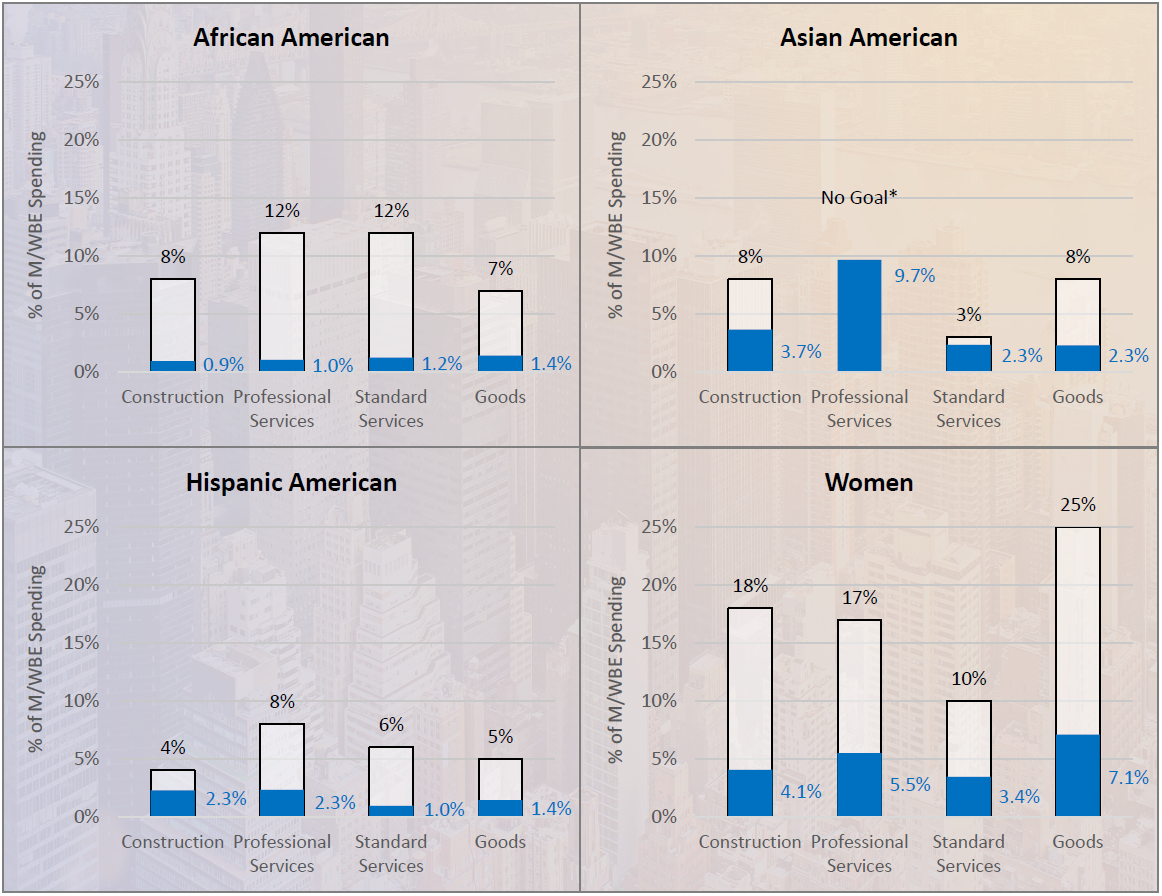

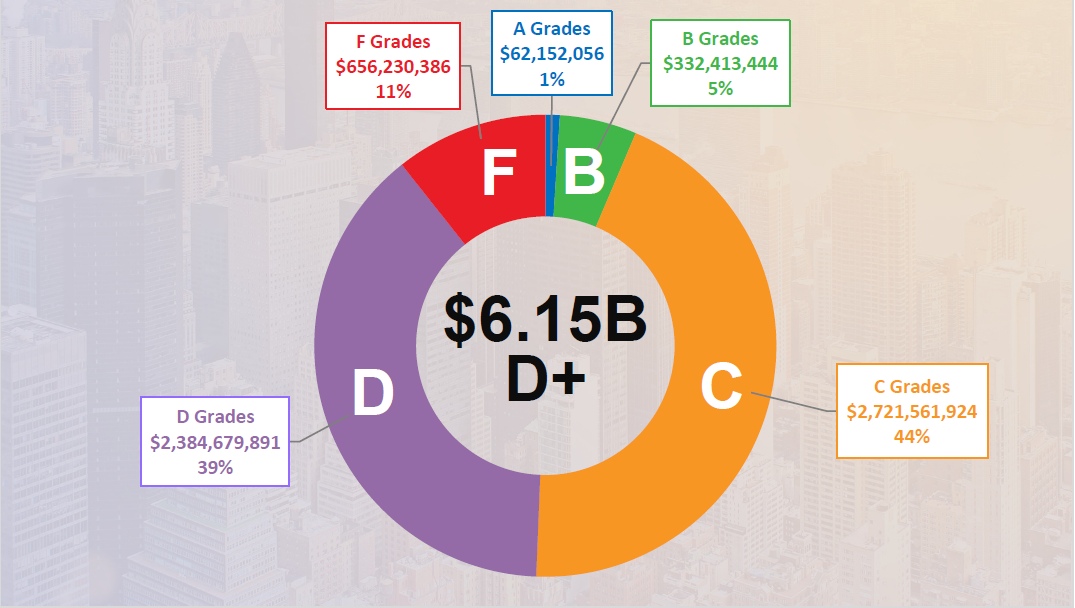

- The City of New York received its fourth consecutive D+ grade because it failed to meet Local Law 1 goals for any industry or minority group. More specifically, the City earned a C grade with Asian American-owned firms, a D grade with both Hispanic American-owned firms and women-owned firms, and an F grade with African American-owned firms – the same grades it earned in FY 2017.

- Although a number of agencies increased their spending with M/WBEs, the combined amount spent by the three agencies that received an “A” is only one percent of the City’s spending under the M/WBE program, while the ten agencies that received either a “D” or “F” grade account for 50 percent of the City’s total M/WBE program spending.

- The City’s grade remains constant because, even though spending with M/WBEs has increased in the last year, spending levels remain low relative to the goals set for each category in Local Law 1.

- At the agency level, grades increased at nine agencies, decreased at five agencies, and stayed the same at 17 agencies compared to last year. This means that almost 30 percent of agencies increased their grade in the last year.

- For the second year in a row, the Commission on Human Rights and the Department for the Aging earned “A” grades, and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene raised their grade to an “A” for the first time.

- One agency received an “F” grade, the Department of Citywide Administrative Services.

- Three agencies, the Departments of Buildings, Transportation, and Sanitation, raised their grades from “F” to “D” in FY 2018, with Sanitation earning a grade increase for the first time.

- For the first time, the Office of the Comptroller has graded the New York Police Department, which earned a “C” grade.

This report also puts forth recommendations meant to reduce barriers and increase access to opportunities

for M / WBEs . This year, the Comptroller’ s Office recommendations include the following:

- Establish a Chief Diversity Officer (CDO) through the City Charter Revision Commission. There is no City policy that mandates agencies have a diversity strategist at the executive level. In previous years, this report has recommended that the City hire a Chief Diversity Officer at both the citywide and agency levels. Consequently, in the Comptroller’s Office’s experience, relatively few agencies have a Chief Diversity Officer at the executive level. That finding is supported by data showing that seven out of the 32 agencies graded have staff with the title of Chief Diversity Officer. However, agency organization charts show that only four CDOs report directly to commissioners, giving them the necessary leverage for agency-wide accountability. The City Charter should establish a CDO for the City as a whole and within each agency and ensure that the position has a uniform role across all agencies. This would ensure that resources continue to be devoted to increasing the inclusion of women and people of color across all City operations. The CDO should have a comprehensive, agency-wide role in addressing structural barriers and policies that prevent inclusion.

- Create more competitive opportunities for M/WBEs on Citywide requirements contracts. Requirements contracts are agreements that agencies, predominantly DCAS and DoITT, enter with a limited number of vendors intended to meet the City’s demand for particular goods or services on an “as-needed” basis, often over multiple years. The City spent more than $1.5 billion through requirements contracts in FY 2018, but M/WBEs received only $102.5 million – less than seven percent – of this spending. Of this, Hispanic American-owned businesses received just $5.4 million and African Americans received just $1 million of all spending through requirements contracts, less than one percent combined. The City should increase opportunities for M/WBEs by reforming how agencies design requirements contracts to award more contracts to a pool of vendors rather than one vendor alone. In addition, the City should also strive to include M/WBE subcontracting goals in all requirements contracts and inform the public of requirements contract renewals.

- The City should require prime vendors to disclose details about their commitment to diversity through a questionnaire when they compete to do business with the City of New York. Many of the City’s largest vendors continue to use few to no M/WBE subcontractors when performing work for the City. In FY 2018, the 25 vendors that received the most City spending received $2.7 billion while their M/WBE subcontractors received only $101 million of this spending, or 3.8 percent. In order to hold the City’s largest vendors accountable for their own supplier diversity plans and increase opportunities for M/WBEs, the City should include a questionnaire which is factored into vendor responsiveness and scope of work. This can be done through the Procurement Policy Board and legislation which can direct the Department of Small Business Services and the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services to promulgate a new rule and guidance. The questionnaire should allow agencies to award points to prospective vendors with robust M/WBE programs and Chief Diversity Officers. To ensure accountability, the City should report publicly on the share of prime vendors with robust supplier diversity plans.

- The New York City Charter should be amended to include timeframes for each agency with a role in the contract review process, in order to alleviate the financial burden of contract delays on M/WBEs. The City’s procurement process involves important oversight from several agencies before contracts can be registered and vendors can be paid for contracted work. Due to the length of this process, firms may end up waiting to get paid for work on public contracts, which M/WBEs cannot afford. In FY 2018, one in four M/WBEs had to work for at least three months without a contract in place or wait at least three months after their contract start date to begin work. Overall, 69 percent of contracts awarded to certified M/WBE vendors were ultimately submitted to the Comptroller’s Office for registration after the contract start date. In order to make the process more efficient, transparent, and sustainable for all firms, the City Charter should be amended to require specific timeframes for each agency with an oversight role in the procurement process. Creating timeframes for all agencies in the procurement process will ensure that vendors have a predictable schedule of review and that agencies act in a timely manner, improving outcomes for vendors and the City alike. Another more sweeping step would be for the City to create a transparent contract tracking system, allowing vendors to view the status of their contracts as they move through the various stages of review.

| 2018 | Third NYC disparity study was commissioned, showing increased availability of M/WBEs and continued underutilization across all minority groups and industries. Mayor de Blasio increased the City’s goal to award a minimum of $20 billion in City contracts to M/WBEs by 2025 and announced a series of events to help M/WBEs win contracts.[xiv] |

| 2016 | Mayor de Blasio created the Mayor’s Office of M/WBEs and set goals of certifying 9,000 M/WBEs by 2019 and awarding 30 percent of City contracts to M/WBEs by 2021.[xiii] |

| 2015 | Mayor de Blasio set a goal of awarding a minimum of $16 billion in City contracts to M/WBEs by 2025.[xii] |

| 2013 | Local Law 1 was enacted, updating M/WBE program goals from 2005 and lifting the $1 million cap on contracts subject to aspirational goals.[xi] |

| 2005 | Local Law 129 was enacted, re-establishing the M/WBE program with aspirational goals for City agencies to award a percentage of contracts between $5,000 and $1 million to M/WBEs by ethnicity and industry.[x] |

| 2004 | Second NYC disparity study was commissioned, showing continued underrepresentation of M/WBEs in City contracts.[ix] |

| 1994 | NYC’s first M/WBE program ended. |

| 1994 | Mayor Giuliani significantly modified the M/WBE program, eliminating the 10 percent allowance and stating that the process must become “ethnic-, race-, religious-, gender- and sexual orientation-neutral.”[viii] |

| 1992 |

Mayor Dinkins created NYC’s first M/WBE program, directing 20 percent of City procurement to be awarded to M/WBEs and allowing the City to award contracts to M/WBEs with bids 10% higher than the lowest bid.[vii] |

| 1992 |

First NYC disparity study commissioned, finding that M/WBEs had a disproportionately small share of City contracts. |

| 1989 |

US Supreme Court ruling, City of Richmond vs. J.A. Croson Co., held that in order to establish an M/WBE program, a municipal government needs to show statistical evidence of a disparity existing between businesses owned by men, women and persons of color.[vi] |

New York City’s M/WBE program

New York City’s program to boost opportunities for M/WBEs began in the 1990s after the City commissioned its first disparity study and found that M/WBEs had a disproportionately small share of City contracts relative to their ability to perform work for the City. The program’s current iteration is governed by Local Law 1 of 2013, which sets participation goals for minority groups on City contracts across four industries: professional services, standard services, goods less than $100,000, and construction.

Recent Progress

The City’s M/WBE program has received renewed attention in recent years, including in 2016, when Mayor de Blasio pledged that the City would certify 9,000 M/WBEs by the end of FY 2019 and award 30 percent of the total dollar value of City contracts to M/WBEs by 2021. More recently, the City increased its goal for the dollar value of contract awards to M/WBEs from $16 billion to $20 billion by the end of 2025.[xv] Some of the specific actions the City is taking to meet those goals are described in more detail below:

- July 2017 – Capacity Building: The City announced that it graduated its eighth cohort of M/WBEs from its Strategic Steps for Growth program, a partnership with New York University that supports business owners in developing business growth plans and competing for City contracts. To date, the program has helped over 100 diverse firms secure $93.5 million in contracts, including $28.6 million in FY 2018, and created nearly 800 jobs across New York.[xvi]

- March 2018 – Awarding Contracts: For the first time, the City hired a women-owned financial firm to manage $100 million of its Deferred Compensation Plan, which is the voluntary retirement plan for over 180,000 City employees and retirees. The New York City Office of Labor Relations, which administers the plan, recently announced that it is seeking to increase the participation of M/WBEs in the Deferred Compensation Plan, with $9 billion in funds across the entire plan becoming available for management by M/WBEs over time.[xvii]

- February to May 2018 – Access to Capital: The City has also announced several initiatives to combat historical institutional discrimination that has impeded M/WBEs from accessing capital. These initiatives include working with private lenders to enhance financing options for M/WBEs, creating more targeted programs for businesses looking to grow, and increasing the amount of money to $1 million that the City will loan to M/WBEs and small businesses bidding on City contracts.[xviii]

- September 2018 – M/WBE Borough Forums: The City announced a series of events to connect M/WBEs to City agencies and to learn about current and upcoming business opportunities. The events will take place in each borough and provide M/WBEs with resources for certification, loans, mentorships, and workshops on how to market their business to the City.[xix]

- October 2018 – OneNYC Contract Awards: The City announced that mayoral and non-mayoral agencies awarded more than $10 billion to M/WBEs since 2015, halfway towards the OneNYC goal of $20 billion by 2025. Mayoral and non-mayoral agencies awarded $3.7 billion to M/WBEs in FY 2018. Non-mayoral agencies include the Economic Development Corporation and the Department of Education, among others.[xx]

Legislative Developments Impacting M/WBEs

In addition to these initiatives, the City Council and State legislature have recently enacted legislation that has the potential to increase contracting opportunities for M/WBEs:

- December 2017 – The State increased the micro purchase threshold: The State legislature approved, and the Governor signed, a bill allowing agencies to award goods and services contracts valued up to $150,000 to City-certified M/WBEs without formal competition, allowing for shorter procurement cycles and increasing opportunities for M/WBEs.[xxi]

- December 2017 – The City increased opportunities for M/WBEs to participate in construction projects: The City enacted a law that will increase M/WBE participation in construction projects that receive City support under the Industrial and Commercial Abatement Program (ICAP). ICAP is a tax incentive program to build, modernize, expand, or improve industrial and commercial buildings.[xxii] As a result of this legislation, any prime vendor receiving ICAP-support on projects above $750,000 is required to directly solicit M/WBEs to participate as contractors and subcontractors, and applicants must inform the Department of Small Business Services (SBS) of contracting and subcontracting opportunities.[xxiii]

- January 2018 – The City Council subcontractor resource guide: The City Council adopted legislation directing the City’s Chief Procurement Officer to develop and make available a subcontractor resource guide that will provide subcontractors with information about their rights with respect to payment by the prime contractor and available City services.[xxiv] The resource guide, which is currently on the New York City Department of Small Business Services website, lists resources for best practices in government contracting and access to capital.[xxv]

City and State Policy Proposals under Consideration

Several proposed policy changes, discussed in more detail below, would, if enacted, improve the contracting environment for M/WBEs:

- Eliminating the State’s personal net worth requirement: In 2017, the New York State legislature passed a bill eliminating the requirement that State-certified M/WBEs have a personal net worth of less than $3.5 million in order to participate in the program. However, the legislation was vetoed by the Governor, and has subsequently been reintroduced.[xxvi] This proposed policy would have a tremendous impact on M/WBEs in high-revenue industries who by nature of their market are precluded from participating in the State M/WBE program. For example, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, there are more than 180 M/WBE asset managers that collectively manage more than $529 billion in public funds that are impacted by the personal net worth cap.[xxvii] Inclusion of M/WBEs in the financial services sector would be a valuable step forward given that diversity at the highest levels of wealth and leadership in the industry has remained relatively stagnant since 2007.[xxviii]

- Reauthorization of the State’s M/WBE program: The New York State M/WBE program began 30 years ago and has periodically been reauthorized by the State legislature. Recently, however, the program was authorized only through December 2019.[xxix] Legislation to provide a long-term reauthorization of the State’s program has been introduced in both the Assembly and Senate and must be signed into law before its expiration.[xxx]

- State recognition of veteran discharge forms in the M/WBE certification process: The New York State legislature passed a bill in June 2018 authorizing New York State to accept minority and women veterans’ discharge forms as proof of their ethnicity or race. The State previously denied minority and women veterans M/WBE certification because the DD Form 214, a federal document showing an individual’s retirement, separation, or discharge from active duty, was not listed as a valid source of verification. The bill, which awaits the Governor’s signature, would alleviate some of the verification burden that veterans may have when looking to qualify for M/WBE programs.[xxxi]

- Improving the City’s communication with vendors: In August 2018, the New York City Council introduced a bill that would require the Procurement Policy Board to create a process for City agencies to inform vendors of the reason for any late payments. Currently there is no requirement for communication to vendors when their payments are late. The bill would also require City agencies to report these late payments to the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services.[xxxii]

M/WBE Contract Awards

Each year, the City releases an M/WBE compliance report and the Agency Procurement Indicators Report outlining the City’s utilization of M/WBEs and activities to increase contracting with M/WBEs. This year, the City announced that M/WBEs were awarded $1.069 billion in contracts, up $32 million from FY 2017. These awards represents 19 percent of contracts within the M/WBE program (contracts subject to Local Law 1), which totaled $5.6 billion, about $3.8 billion less than the total value of contracts within the M/WBE program in FY 2017.[xxxiii] However, as shown in Chart 1, M/WBE awards represent less than six percent of the total value of procurement awards in FY 2018, which was $19.3 billion, a $1.6 billion decrease from total procurement awards in FY 2017. This report has previously recommended that the City expand the universe of contracts that are part of the M/WBE program. For this reason, this calculation represents M/WBE awards as a share of all contract awards.

Chart 1: M/WBE Share of City Procurement, FY 2007 – FY 2018

Source: Mayor’s Office of Contract Services Agency Procurement Indicators: Fiscal Years 2007 to 2018, and OneNYC: Minority and Women-Owned Business Enterprise Bulletin, Sept. 2015.

Spending and Certification

The City has taken several positive steps to expand its pool of diverse vendors, growing the number of City-certified M/WBEs from 5,259 in FY 2017 to 6,679 in FY 2018 – an increase of 1,420 firms.[xxxiv] However, simply becoming certified is not a guarantee of receiving contracts from the City. As shown in Chart 2, the share of certified M/WBEs receiving City payments has remained relatively flat over the past four years. Although the number of M/WBEs receiving spending is growing by approximately 200 firms every year, the number of certified M/WBEs receiving no City spending is increasing more quickly. Between FY 2015 and FY 2016, the number of M/WBEs that did not receive payments from the City grew by 226. That difference grew to 1,190 firms between FY 2017 and FY 2018. This is a troubling trend because it could lead to the long-term stagnation of the M/WBE program. Chart 2 also shows the share of certified M/WBEs receiving payments as prime contractors and subcontractors. The share of certified M/WBEs receiving prime payments in FY 2018 has remained at 16 percent over the past four years, with a slight increase in FY 2017 to 17 percent. The share of M/WBEs receiving subcontracting payments has also remained at 5 percent from FY 2016 to FY 2018.

Chart 2: Certified M/WBEs Receiving City Contract Payments: FY 2015 – FY 2018

*M/WBE vendors that received both prime contractor and subcontractor payments are seen here as prime vendors only.

Source: Checkbook NYC.

Citywide Grades

As with prior Making the Grade reports, the mayoral agencies graded are subject to Local Law 1 M/WBE participation goals. The grades are based on actual spending within FY 2018, rather than the value of contracts awarded during the fiscal year, because contract awards may or may not result in M/WBEs actually receiving payments from the City. Overall, the City’s grade for FY 2018 remains unchanged at “D+.” The City earned a “C” grade with Asian American-owned firms, a “D” grade with Hispanic American-owned firms and women-owned firms, and an “F” grade with African American-owned firms. This is the fourth consecutive “D+” grade for the City. The City’s grade remains constant because, even though spending with M/WBEs has increased in the last year, spending levels remain low relative to the goals set for each category in Local Law 1. City procurement spending as a whole also increased by $728.6 million, an additional contributor to relatively low M/WBE spend. In FY 2018, the Comptroller’s Office launched Citywide Progress Reports, a new tool for City agencies to overcome the challenge of tracking spending rather than contract awards to M/WBEs. These progress reports provide an analysis of each agency’s spending by ethnicity and industry compared with Local Law 1 goals. As shown in Chart 3, for FY 2018, the City failed to meet any goals in any industry or for any minority group.

Chart 3: Citywide M/WBE Spending Compared with Local Law 1 Goals, FY 2018

Source: Checkbook NYC.

*Local Law 1 does not include a goal for Asian American-owned businesses in the professional services industries. However, the City’s latest disparity study found underutilization of these firms, and recommended that the goal be added in the next iteration of the law.

** Quarterly progress reports can be found at https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/making-the-grade/progress-report/.

Agency Grades

In FY 2018, of the 32 mayoral agencies graded, three received an “A,” six received a “B”, 13 received a “C,” nine received a “D,” and one received an “F” grade. The Police Department, which this report includes for the first time due to the availability of new data, received a “C” grade. While not a mayoral agency, the Comptroller’s Office is also graded annually in this report and received its third consecutive “B” grade in FY 2018. Two agencies – the Commission on Human Rights and the Department for the Aging – sustained their “A” grade from FY 2017 to FY 2018, and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene received an “A” grade for the first time. The Department of Housing Preservation and Development, which earned the sole “A” grade in FY 2016 and received a “B” grade in FY 2017, fell to a “C” grade, and the Department of Small Business Services, which received its first “A” grade in FY 2017, fell to a “C” grade in FY 2018. Seven agencies, the Department of Buildings, Department of Citywide Administrative Services, Department of Environmental Protection, Department of Homeless Services, Department of Transportation, Human Resources Administration, and the Office of Emergency Management, have received “D” or “F” grades in each of the last five years. One agency, the Business Integrity Commission, dropped from a “C” to a “D,” and the Department of Finance, Department of Homeless Services, Human Resources Administration, and the Office of Emergency Management remained at “D” grades. However, the City saw marked improvement at agencies that previously performed relatively poorly. Four agencies improved from “D” to C” grades: the Department of Correction, Department of Design and Construction, Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications, and the Law Department. And the Departments of Buildings, Transportation, and Sanitation raised their grades from “F” grades to “D” grades in FY 2018, with Sanitation raising its grade for the first time. Overall, in FY 2018, nine grades increased, 17 grades remained the same, and five declined. This means that almost 30 percent of agencies increased their grade in the last year. As shown in Chart 4, although a number of agencies increased their spending with M/WBEs, the combined amount spent by the three agencies that received an “A” is only one percent of the City’s spending under the M/WBE program, while the ten agencies that received either a “D” or “F” grade account for 50 percent of the City’s total M/WBE program spending. Reaching an “A” grade, therefore, will require increased M/WBE spending at the City agencies with the highest amount of Local Law 1 eligible procurement spending.

Chart 4: Composition of Citywide M/WBE Grade by Total Agency Spending, FY 2018

Source: Checkbook NYC

Table 1 provides each agency’s assigned grade and compares grades from FY 2018 to the last four fiscal years. This year, for the first time, this report also presents agency grades for each M/WBE group. For their spending with African Americans, three agencies received “A” grades, two agencies received “B” grades, six received “D” grades, and 21 received “F” grades. With Asian Americans, 16 agencies received “A” grades, one received a “B” grade, four received “C” grades, six received “D” grades, and five received “F” grades. With Hispanic Americans, eight agencies earned “A” grades, three received “C” grades, ten received “D” grades, and 11 received “F” grades. And with women, four agencies received “A” grades, four received “B” grades, four received “C” grades, 12 received “D” grades, and eight received “F” grades. Tables 2 through 5 provide assigned grades for agencies by minority group and industry. Additional information about individual agency grades is available in Appendix A.

Table 1: Comparison of FY 2014 – FY 2018 Grades

| Abbr. | Agency Name | FY14 | FY15 | FY16 | FY17 | FY18 | FY17 – FY18 |

| City | Citywide | D | D+ | D+ | D+ | D+ | — |

| CCHR | Commission on Human Rights | C | C | B | A | A | — |

| DFTA | Department for the Aging | D | C | B | A | A | — |

| DOHMH | Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | C | C | C | B | A | 1 |

| CCRB | Civilian Complaint Review Board | C | C | D | B | B | — |

| DCA | Department of Consumer Affairs | D | C | B | B | B | — |

| DCLA | Department of Cultural Affairs | B | C | C | B | B | — |

| DPR | Department of Parks and Recreation | D | C | C | B | B | — |

| DOP | Department of Probation | C | D | D | C | B | 1 |

| TLC | NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | D | D | D | B | B | — |

| ACS | Administration for Children’s Services | C | C | C | C | C | — |

| DCP | Department of City Planning | C | C | B | C | C | — |

| DOC | Department of Correction | D | D | C | D | C | 1 |

| DDC | Department of Design and Construction | D | C | D | D | C | 1 |

| HPD | Department of Housing Preservation and Development | D | A | A | B | C | 1 |

| DoITT | Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | F | D | D | D | C | 1 |

| SBS | Department of Small Business Services | D | F | B | A | C | 2 |

| DYCD | Department of Youth and Community Development | C | C | C | B | C | 1 |

| FDNY | Fire Department | D | D | C | C | C | — |

| LPC | Landmarks Preservation Commission | B | B | B | B | C | 1 |

| Law | Law Department | C | D | C | D | C | 1 |

| OATH | Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | D | C | D | C | C | — |

| NYPD | Police Department | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | C | New Agency |

| BIC | Business Integrity Commission | D | D | F | C | D | 1 |

| DOB | Department of Buildings | D | D | F | F | D | 1 |

| DEP | Department of Environmental Protection | F | F | D | D | D | — |

| DOF | Department of Finance | F | D | C | D | D | — |

| DHS | Department of Homeless Services | D | D | D | D | D | — |

| DSNY | Department of Sanitation | F | F | F | F | D | 1 |

| DOT | Department of Transportation | D | D | D | F | D | 1 |

| HRA | Human Resources Administration | D | D | D | D | D | — |

| OEM | Office of Emergency Management | D | D | D | D | D | — |

| DCAS | Department of Citywide Administrative Services | D | D | D | F | F | — |

| OCC | Office of the Comptroller | C | C | B | B | B | — |

Table 2: Agency Grades with African Americans by Industry

| Agency Name | African American | Construction | Professional Services | Standard Services | Goods < 100K |

| New York Citywide | F | F | F | F | D |

| Commission on Human Rights | A | N/A* | A | A | C |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | A | F | F | F | A |

| Department of Small Business Services | A | F | A | A | C |

| Department for the Aging | B | F | F | D | A |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | B | N/A* | A | F | A |

| Administration for Children’s Services | D | F | F | C | A |

| Business Integrity Commission | D | N/A* | F | A | F |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | D | A | F | D | B |

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | D | F | F | C | A |

| Department of Transportation | D | D | F | F | C |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | D | N/A* | F | D | D |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | F | N/A* | F | F | F |

| Department of Buildings | F | N/A* | F | F | D |

| Department of City Planning | F | F | F | F | D |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | F | F | F | D | F |

| Department of Consumer Affairs | F | N/A* | F | F | F |

| Department of Correction | F | F | F | F | A |

| Department of Design and Construction | F | F | D | B | A |

| Department of Environmental Protection | F | F | F | F | A |

| Department of Finance | F | F | F | F | D |

| Department of Homeless Services | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | F | F | F | F | A |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | F | F | F | F | B |

| Department of Probation | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Sanitation | F | F | F | F | A |

| Fire Department | F | F | F | F | B |

| Human Resources Administration | F | F | F | F | D |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | F | F | D | F | F |

| Law Department | F | N/A* | F | F | B |

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | F | N/A* | F | F | C |

| Office of Emergency Management | F | F | F | F | F |

| Police Department | F | F | F | F | D |

| Office of the Comptroller | D | N/A* | D | C | B |

*Agency spent $0 within this industry in FY 2018.

Table 3: Agency Grades with Asian Americans by Industry

| Agency Name | Asian American | Construction | Professional Services | Standard Services | Goods < 100K |

| New York Citywide | C | C | No Goal | B | D |

| Administration for Children’s Services | A | B | No Goal | A | A |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | A | N/A* | No Goal | F | A |

| Commission on Human Rights | A | N/A* | No Goal | A | A |

| Department for the Aging | A | F | No Goal | A | F |

| Department of City Planning | A | F | No Goal | F | A |

| Department of Consumer Affairs | A | N/A* | No Goal | A | A |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | A | A | No Goal | F | F |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | A | A | No Goal | A | A |

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | A | A | No Goal | A | A |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | A | F | No Goal | A | A |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | A | A | No Goal | A | B |

| Department of Probation | A | F | No Goal | F | A |

| Fire Department | A | F | No Goal | A | B |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | A | A | No Goal | F | F |

| Law Department | A | N/A* | No Goal | A | A |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | A | N/A* | No Goal | A | A |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | B | N/A* | No Goal | F | A |

| Department of Design and Construction | C | D | No Goal | A | A |

| Department of Environmental Protection | C | C | No Goal | D | A |

| Department of Sanitation | C | D | No Goal | C | C |

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | C | N/A* | No Goal | D | C |

| Department of Buildings | D | N/A* | No Goal | F | A |

| Department of Correction | D | D | No Goal | F | B |

| Department of Finance | D | F | No Goal | F | C |

| Department of Homeless Services | D | A | No Goal | D | F |

| Human Resources Administration | D | A | No Goal | F | A |

| Police Department | D | D | No Goal | F | C |

| Business Integrity Commission | F | N/A* | No Goal | F | F |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | F | A | No Goal | D | F |

| Department of Small Business Services | F | F | No Goal | F | F |

| Department of Transportation | F | F | No Goal | F | A |

| Office of Emergency Management | F | F | No Goal | F | A |

| Office of the Comptroller | A | N/A* | No Goal | A | A |

*

Agency spent $0 within this industry in FY 2018.

Table 4: Agency Grades with Hispanic Americans by Industry

| Agency Name | Hispanic American | Construction | Professional Services | Standard Services | Goods < 100K |

| New York Citywide | D | C | D | F | D |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | A | N/A* | F | F | A |

| Commission on Human Rights | A | N/A* | F | B | A |

| Department for the Aging | A | F | A | A | A |

| Department of Consumer Affairs | A | N/A* | F | D | A |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | A | A | A | F | A |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | A | A | F | A | C |

| Department of Probation | A | F | F | F | A |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | A | N/A* | A | D | A |

| Department of Design and Construction | C | D | A | B | A |

| Fire Department | C | A | F | F | F |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | C | F | F | A | F |

| Administration for Children’s Services | D | F | F | B | C |

| Department of Buildings | D | N/A* | F | B | A |

| Department of City Planning | D | F | F | F | A |

| Department of Correction | D | D | F | F | C |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | D | F | F | A | A |

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | D | A | F | F | A |

| Department of Transportation | D | C | D | F | A |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | D | N/A* | F | F | A |

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | D | N/A* | F | F | A |

| Police Department | D | A | F | F | C |

| Business Integrity Commission | F | N/A* | F | F | F |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | F | A | F | F | F |

| Department of Environmental Protection | F | F | F | F | A |

| Department of Finance | F | A | F | F | A |

| Department of Homeless Services | F | F | F | F | B |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | F | F | F | D | A |

| Department of Sanitation | F | F | F | F | C |

| Department of Small Business Services | F | F | F | F | A |

| Human Resources Administration | F | A | F | F | A |

| Law Department | F | N/A* | F | F | F |

| Office of Emergency Management | F | F | D | F | F |

| Office of the Comptroller | A | N/A* | A | D | A |

*Agency spent $0 within this industry in FY 2018.

Table 5: Agency Grades with Women by Industry

| Agency Name | Women | Construction | Professional Services | Standard Services | Goods < 100K |

| New York Citywide | D | D | D | D | D |

| Commission on Human Rights | A | N/A* | A | A | C |

| Department for the Aging | A | F | F | A | A |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | A | F | A | A | B |

| Department of Small Business Services | A | F | A | A | D |

| Department of Correction | B | B | F | A | C |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | B | F | F | A | D |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | B | N/A* | A | A | C |

| Police Department | B | A | F | A | D |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | C | C | A | F | B |

| Human Resources Administration | C | F | A | F | B |

| Law Department | C | N/A* | F | A | D |

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | C | N/A* | F | C | A |

| Administration for Children’s Services | D | F | C | F | C |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | D | N/A* | C | F | D |

| Department of City Planning | D | A | F | A | F |

| Department of Consumer Affairs | D | N/A* | F | D | F |

| Department of Design and Construction | D | D | C | C | D |

| Department of Finance | D | F | F | A | D |

| Department of Homeless Services | D | F | A | F | D |

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | D | A | F | F | C |

| Department of Probation | D | F | F | F | C |

| Fire Department | D | D | F | D | C |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | D | F | F | A | F |

| Office of Emergency Management | D | F | C | F | D |

| Business Integrity Commission | F | N/A* | F | D | D |

| Department of Buildings | F | N/A* | F | D | C |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | F | D | C | F | F |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | F | F | F | A | F |

| Department of Environmental Protection | F | F | D | F | A |

| Department of Sanitation | F | F | F | F | B |

| Department of Transportation | F | F | F | F | A |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | F | N/A* | F | F | A |

| Office of the Comptroller | B | N/A* | B | A | F |

*Agency spent $0 within this industry in FY 2018.

Methodology

To calculate each grade, the Comptroller’s Office relied on Checkbook NYC, the Comptroller’s online transparency website, which uses information entered into the City’s centralized Financial Management System (FMS) by agency staff. The FY 2018 spending data for each agency was extracted, analyzed by the population and industry categories established in Local Law 1, and then compared against the Local Law 1 Citywide M/WBE participation goals. As with each year’s report, grades for FY 2018 are based on total spending by each agency across the four Local Law 1 industry categories and the Local Law 1 defined groups within each industry classification. It is important to note, however, that while the industry classifications and groups set forth in Local Law 1 were applied, this is not intended to be a Local Law 1 compliance report. Rather, it is a report detailing overall agency spending with M/WBEs in FY 2018, expressed both in dollars and as a percentage of total agency spending. Certain spending not subject to Local Law 1—such as payroll, human services, and land acquisition—was removed from the grade calculations, along with categories where specific agencies had no relevant business (i.e., construction participation goals were removed from the calculation of agencies that perform no construction). The results were then weighted to account for the agency’s spending in different industry categories (professional services, standard services, construction, and goods). For example, if an agency spent 50 percent of its procurement budget on construction, then 50 percent of its grade is based on meeting the construction participation goals under Local Law 1. After weighting, scores were assigned a value and converted into a letter grade. While certain additional exclusions do exist, they are limited in number and do not mirror the exempted procurement award methods listed in Local Law 1. Rather, the exclusions are based on the availability (or lack thereof) of M/WBEs to meet agency procurement requirements within a particular award method or contract type. The Police Department’s vendor data was previously excluded from Checkbook NYC and was made available for the first time this year. With the addition of spending data from the Police Department, the City’s overall grade for FY 2018 includes spending by 32 agencies rather than 31. The worksheets used to calculate each agency grade appear in Appendix B and a complete explanation of the report’s methodology can be found in Appendix D. Subcontract data for each agency can be found in Appendix C.

M/WBE Challenges

The primary goal of this report is to help the City increase utilization of M/WBEs in procurement. With that goal in mind, this year, the Comptroller’s Office held a series of focus groups to gather firsthand contracting experiences of M/WBEs and the expertise of the members of the Comptroller’s Advisory Council on Economic Growth through Diversity and Inclusion. Participants in these conversations described the following challenges:

- “I can’t access contracting opportunities at all as a prime or subcontractor because the City has requirements contracts for my industry.” Some M/WBEs discussed being unable to compete in the public contracting process because of requirements contracts, which are multi-year agreements between the City and vendors to provide a good or service to all City agencies.

- “There are too many RFPs [requests for proposals] without M/WBE goals that set unnecessary minimum requirements. They are written so that only giant corporations can win them even though there are so many M/WBEs who would otherwise be eligible.” Others called attention to City agency officials having limited knowledge of their industry markets and M/WBE availability.

- “Corporations have told me to my face, ‘Why should I do business with you?’” Participants also emphasized that large vendors that hold contracts with the City are unwilling to engage them because they were neither incentivized nor required to do so by the City.

- “There is so much that goes wrong between being awarded and getting paid. If that stays the same, competing may not be worth my time.” M/WBEs who were awarded contracts found that the contract review process was so long and challenging that they often had to wait to start work or begin work without a contract in place. Many expressed feeling discouraged to compete for their next contract.

Based on this feedback, this report makes the following recommendations:

Recommendation: Institutionalization of the Chief Diversity Officer (CDO) through the City Charter Revision Commission.

In previous years, this report has recommended that the City hire a Chief Diversity Officer at the citywide and agency levels. Currently every agency has an M/WBE Officer and Equal Employment Opportunity Officer.[xxxv] However, there is no City policy that mandates agencies have a diversity strategist at the executive level. Consequently, in the Comptroller’s Office’s experience, relatively few agencies have a Chief Diversity Officer at the executive level. That finding is supported by data from New York City’s Employee Portal, which shows that six out of the 32 agencies graded have staff with the title of Chief Diversity Officer. These agencies are: Department of Design and Construction, Department of Finance, Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications, Department of Transportation, Fire Department, and the Law Department. In addition, the Department of Sanitation recently announced the appointment of a Chief Diversity Officer.[xxxvi] As seen in Table 6, however, agency organization charts show that only four CDOs report directly to commissioners with various inconsistencies in their portfolios. Of course it is possible that there may be staff functioning as executive-level diversity strategists without the title of Chief Diversity Officer, but without a policy in place, inconsistencies will remain and sustainability of the role cannot be guaranteed. The City should ensure that the CDO role is uniform across all agencies and that it is sustained and institutionalized in the City Charter. This would ensure that resources continue to be devoted to increasing the inclusion of women and people of color across all City operations. As shown in the model job description in Table 7, the CDO should report directly to the agency head and have a comprehensive, agency-wide role in addressing structural barriers and policies that prevent inclusion. Reporting directly to the agency head would give the CDO leverage to facilitate change in any part of the agency.

Table 6: Citywide and Agency Diversity Leadership Roles

| Agency Name | EEO Officers Required | M/WBE Officer Required | Chief Diversity Officer** | CDO Reports to Commissioner or Mayor |

| New York Citywide | Senior Advisor | — | — | |

| Administration for Children’s Services | — | — | ||

| Business Integrity Commission | — | — | ||

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | — | — | ||

| Commission on Human Rights | — | — | ||

| Department for the Aging | — | — | ||

| Department of Buildings | — | — | ||

| Department of City Planning | — | — | ||

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | — | — | ||

| Department of Consumer Affairs | — | — | ||

| Department of Correction | — | — | ||

| Department of Cultural Affairs | — | — | ||

| Department of Design and Construction | ||||

| Department of Environmental Protection | — | — | ||

| Department of Finance | — | |||

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | — | — | ||

| Department of Homeless Services | — | — | ||

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | — | — | ||

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | ||||

| Department of Parks and Recreation | — | — | ||

| Department of Probation | — | — | ||

| Department of Sanitation | * | * | ||

| Department of Small Business Services | — | — | ||

| Department of Transportation | — | |||

| Department of Youth and Community Development | — | — | ||

| Fire Department | ||||

| Human Resources Administration | — | — | ||

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | — | — | ||

| Law Department | ||||

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | — | — | ||

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | — | — | ||

| Office of Emergency Management | — | — | ||

| Police Department | — | — | ||

| Office of the Comptroller |

* DSNY’s announcement does not include information about whether the CDO will report directly to the Commissioner.

** Source: CityShare, New York City’s Employee Portal

Table 7: Chief Diversity Officer Model Job Description

| JOB VACANCY NOTICE

Title: Chief Diversity Officer |

DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

|

Recommendation: Create more competitive opportunities for M/WBEs on citywide requirements contracts.

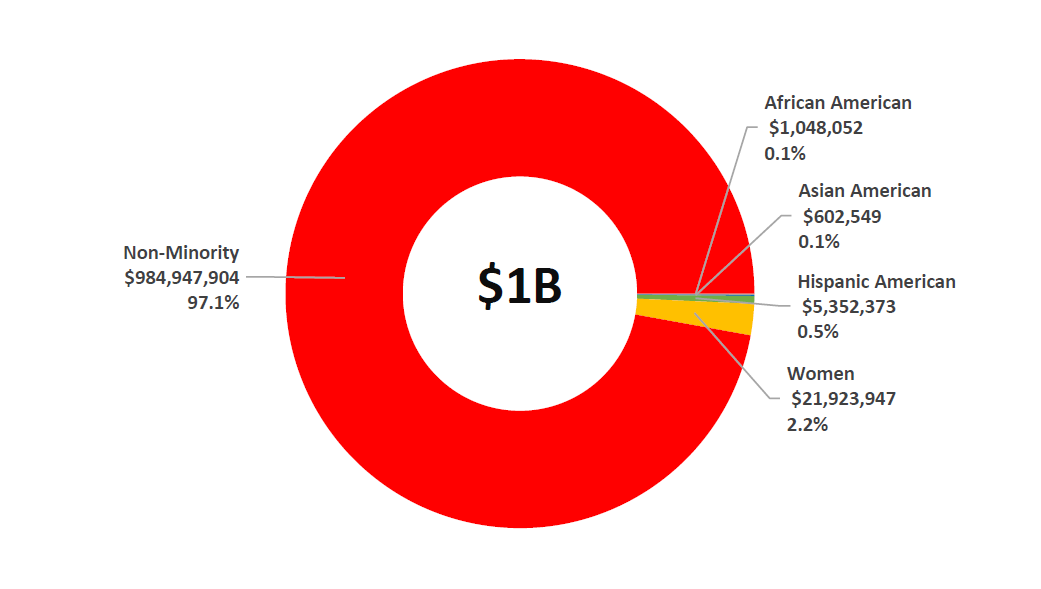

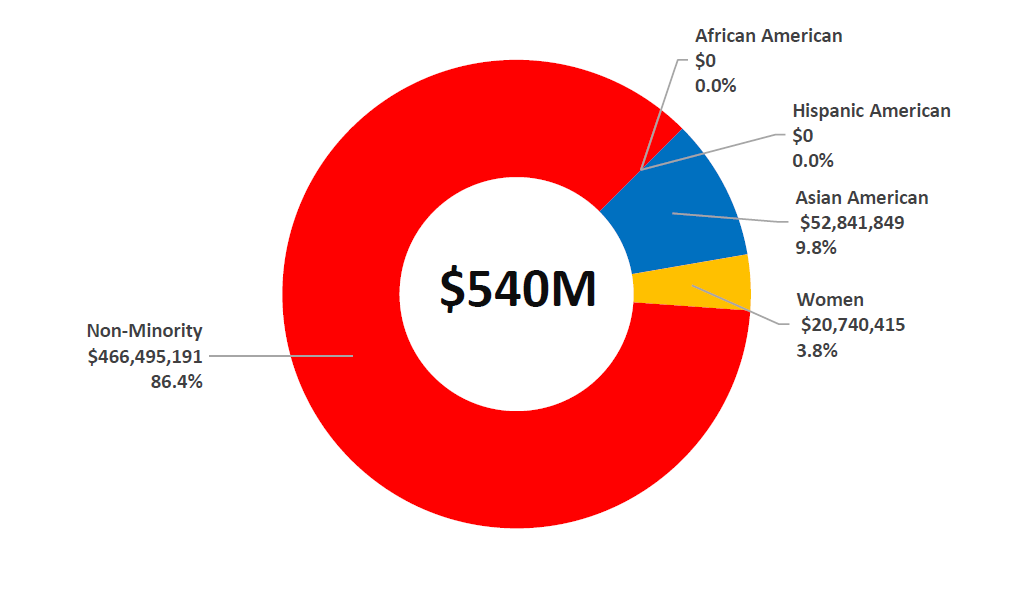

In order to increase efficiency and maximize the purchasing power of the City, the Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) and the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications (DoITT) must re-evaluate requirements contracts. Requirements contracts are agreements that agencies, predominantly DCAS and DoITT, enter with a limited number of vendors intended to meet the City’s demand for particular goods or services on an “as-needed” basis, often over multiple years.[xxxvii] Other agencies then submit orders to DCAS or DoITT. When City agencies issue these orders, they bypass the RFP process, quickly fulfilling their orders, saving agency time and paperwork. Vendors chosen often benefit from the exclusivity of their contracts, as they do not have to formally compete to meet individual agencies’ needs each time those needs arise. DCAS is the largest source of City requirements contracts and currently manages more than 1,000 active requirements contracts valuing a total of $4.9 billion.[xxxviii] These range from contract values in the hundreds of dollars to $205 million, with the average DCAS requirement contract valued at $4.5 million. In addition, 68 percent of the contracts have terms lasting at least four years and two contracts have ten-year contract terms, making them relatively long-term contracts that offer vendors a secure flow of revenue. In FY 2018, all City agencies spent over $1.5 billion on requirements contracts, including $1 billion through DCAS and $540 million through DoITT, as shown in Charts 5 and 6. The single largest type of requirement contract spending through DCAS is goods, which is the result of the City Charter’s mandate that DCAS procure all goods contracts above $100,000 on behalf of City agencies.[xxxix] In FY 2018, DCAS spent a total of $611.6 million on goods such as automobiles, furniture, and fuel. In addition, the agency spent $4.8 million in construction, $2.6 million in professional services, and $314.8 million in standard services through requirements contracts. These procurements include services such as building security for public buildings, equipment maintenance, cleaning services, specialized printing of election and public meeting documents, and advertising for recruitment. DoITT also has Charter authority to procure hardware, software, and technology-related services on behalf of City agencies.[xl] In FY 2018, DoITT requirements contract spending included $214.8 million on goods such as software licenses, printing supplies, books, and technology-related security equipment. It also consisted of $144.3 million in standard services such as equipment maintenance and cabling services and $177 million in professional services like technology-related consulting, quality control, and employee training. M/WBE spending is low among requirements contracts. In fact, as shown in Charts 5 and 6, M/WBEs received only $102.5 million – less than seven percent – of the City’s $1.5 billion in spending on requirements contracts in FY 2018. Of that $102.5 million, M/WBEs received $28.9 million, or 2.9 percent, of DCAS spending under requirements contracts and $73.6 million, or 14 percent, of DoITT spending. Of this, Hispanic American-owned businesses received just $5.4 million and African Americans received just $1 million of all spending under requirements contracts – less than one percent combined. When issuing requirements contracts, the City must strike a better balance between efficiency and competition. It must also tackle the challenge of including M/WBEs on contracts because traditionally these procurements tend to be awarded to larger firms with access to capital, larger insurance plans, and the ability to weather low cash flow during gaps in agency orders, which can exclude M/WBEs and new vendors.

Chart 5: DCAS Requirement Contract Spending by Minority Group

*DCAS is Charter-mandated to procure all goods above $100,000. DCAS spending under requirements contracts includes both citywide contracts and standalone, agency-specific goods contracts above $100,000.

Chart 6: DoITT Requirement Contract Spending by Minority Group

Source: Checkbook NYC.

The City should increase opportunities for M/WBEs by moving requirements contracts toward a model where a pool of multiple vendors that vary in size and capacity are awarded smaller contracts, rather than one large vendor. Maintaining pools of vendors from which agencies could choose when purchasing goods and services rather than just one vendor would meet the need for efficiency while also allowing the City to purchase goods and services from businesses of varying sizes. A number of requirements contracts will reach their conclusion in the coming years, presenting an opportunity to evaluate whether they should be renewed or re-bid. While that decision is made on a case-by-case basis, through re-bidding and debundling them into multiple smaller contracts, more procurement opportunities could exist for M/WBEs. The City may find opportunities for vendors to compete for work through mini bids and other opportunities where multiple contracts may be awarded for categories for goods or services.

Requirements contracts should include M/WBE subcontracting goals. Adding M/WBE subcontracting goals would provide M/WBEs with more opportunities to receive spending on requirements contracts. This reform would be particularly impactful in the standard services industry. For example, DCAS holds six contracts with three building security firms with a combined total contract value of $684 million and FY 2018 spending under those contracts of $250.5 million.[xli] One firm, FJC Security Services (a non-M/WBE vendor), received the vast majority of this spending: $214.4 million – a full 21 percent of all DCAS requirements contracts payments. These contracts are eligible for a three-year renewal in December 2018.[xlii] The City should use data on agency needs to be more strategic when sourcing security services and develop contracts of various sizes to create competition. Currently, the 115 City-certified M/WBE firms who have signed up to provide guard and security services are effectively prohibited from conducting business with the City until at least 2021 should the existing requirements contracts for security services be renewed for the full three-year term.[xliii] M/WBE subcontracting goals would also help in the goods category. For example, DCAS holds ten contracts with six office furniture vendors, with a combined total contract value of $157.7 million and $15.8 million in spending in FY 2018. However, there are currently 100 certified M/WBE firms who are signed up for office furniture commodity codes and none are vendors under the office furniture requirement contracts.[xliv] Expanding M/WBE access to goods requirements contracts will require changes to Local Law 1. That is because under current law, goods contracts over $100,000 are not subject to the law’s M/WBE utilization goals. The City’s recent disparity study provided the evidence needed to amend Local Law 1 to expand M/WBE access to goods requirements contracts.[xlv]

Inform the public of requirement contract renewals. This report has previously recommended that the City take steps to better monitor markets for pricing and consider M/WBE availability in decisions to renew contracts with its largest vendors. To build on that recommendation, the PPB should also require DCAS and DoITT to notify the public of requirements contracts renewals at least one year in advance, as is already required before human services contracts can be renewed.[xlvi] These should include documented market analyses demonstrating that current contracted rates are fair, reasonable, and at or below the most current market rate. In addition, the PPB should require DCAS and DoITT to demonstrate that renewing a given requirement contract does not impede M/WBE competition. Public notification in this case should include City Record postings, agency website notices, publications in local newspapers, reports to Borough Presidents and Community Board chairs, and public hearings. Although expanding this practice to requirements contracts would necessitate additional City resources, this strategy would increase the number of firms competing for City contracting, improving prices for the City in the long-term.

Recommendation: The City should require prime vendors to disclose details about their commitment to diversity through a questionnaire when they compete to do business with the City of New York.

The City has successfully increased diverse businesses’ access to small, discretionary contracts. In fact, the latest disparity study found 30 percent M/WBE utilization for contracts up to $1 million. However, the City has largely failed at providing access to larger contracts as M/WBE utilization decreases with contract size above $1 million and virtually disappears for procurements above $15 million.[xlvii] In an effort to identify these large-scale opportunities, this report previously looked at the vendors that receive the most City dollars and their spending with M/WBE subcontractors. Unfortunately, the City’s largest vendors continue to be marked by low M/WBE utilization. In FY 2018, the top 25 vendors received $2.7 billion in City spending of which M/WBEs received only $101 million, or 3.8 percent of those dollars, compared with 4.2 percent in FY 2017. The vendor that received the most City payments, FJC, is previously mentioned in this report as the recipient of 21 percent of spending under DCAS requirements contracts. The achievement of the City’s ambitious 30 percent goal depends on the partnership and commitment from its largest private sector partners. As stated in past reports, the City should have an ongoing dialogue with its largest vendors, and it should explore changes to Local Law 1 to expand Tier II spending. Tier II spending includes subcontractors, suppliers, and subcontractors of subcontractors. In the private sector, companies recognize that robust Tier II strategies help them institutionalize diversity as an overall business strategy. In fact, corporations are required to have a Tier II program in order to qualify as members of the Billion Dollar Roundtable, an organization that promotes and shares supplier diversity best practices and that celebrates corporations that achieve at least $1 billion in spending with M/WBEs.[xlviii] In order to hold the City’s largest vendors accountable for their own supplier diversity plans and increase opportunities for M/WBEs, the City should include a questionnaire which is factored into vendor responsiveness and scope of work. This can be done through the Procurement Policy Board and legislation which can direct the Department of Small Business Services and the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services to promulgate a new rule and guidance. The completion of these questionnaires should factor into vendor responsiveness determinations, and the City should report publicly on the share of prime vendors with robust supplier diversity plans. The City should also consider awarding points to vendors with robust M/WBE programs, a practice that is currently implemented at the State level for best value contracts and is a contributing factor to the State’s 29 percent M/WBE spending.[xlix] Supplier diversity questionnaires should include questions regarding vendors’ Chief Diversity Officers; their companies’ spending with M/WBEs, including their overhead for indirect and non-contract related expenses; M/WBE utilization goals on non-governmental procurements; participation in industry-specific technical training of M/WBEs or mentor-protégé programs; whether they have formal M/WBE supplier programs; and whether they plan to use M/WBEs on the procurement for which they are being scored.[l] A sample supplier diversity questionnaire can be found in Appendix E.

Table 8: Largest Businesses Receiving City Dollars in FY 2018

| # | Prime Vendor Name | Prime Minority Status | All Spending | M/WBE Prime Spending | M/WBE Sub Spending | Percent M/WBE Spending |

| 1 | FJC Security Services, Inc. | Non-Minority | $214,367,122 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 2 | ACE American Insurance Co. | Non-Minority | $209,256,403 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 3 | Liro Program and Construction Management PE PC | Non-Minority | $193,129,321 | $0 | $1,149,716 | 0.6% |

| 4 | Waste Management of NY LLC | Non-Minority | $184,938,835 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 5 | CDW Government LLC | Non-Minority | $177,149,373 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 6 | Leon D. Dematteis Construction Corp | Non-Minority | $166,982,736 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 7 | Tishman Construction Corporation of NY | Non-Minority | $141,795,044 | $0 | $6,077,408 | 4.3% |

| 8 | Tully Construction Co. Inc. | Non-Minority | $137,430,903 | $0 | $5,270,628 | 3.8% |

| 9 | SLSCO LP | Non-Minority | $133,109,681 | $0 | $8,655,183 | 6.5% |

| 10 | Citnalta Construction Corp. | Non-Minority | $113,126,791 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 11 | Motorola Solutions, Inc. | Non-Minority | $89,186,991 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 12 | Kiewit-Shea Constructors, AJV | Non-Minority | $76,525,341 | $0 | $707,866 | 0.9% |

| 13 | CAC Industries Inc. | Non-Minority | $74,735,684 | $0 | $5,272,572 | 7.1% |

| 14 | International Business Machines Corp | Non-Minority | $74,434,560 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 15 | Covanta Sustainable Solutions LLC | Non-Minority | $73,522,293 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 16 | Telesector Resources Group Inc. A Verizon Services Group | Non-Minority | $71,209,450 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 17 | FJ Sciame Construction Co Inc. | Non-Minority | $69,173,977 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 18 | Turner Construction Co. | Non-Minority | $68,172,350 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 19 | Adam’s European Contracting Inc. | Women | $63,915,823 | $63,876,398 | $39,425 | 100.0% |

| 20 | Whitestone Construction Corp | Non-Minority | $57,468,012 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 21 | Triumph Construction Corp | Non-Minority | $55,434,215 | $0 | $311,978 | 0.6% |

| 22 | Sprague Operating Resources LLC | Non-Minority | $54,672,774 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 23 | Volmar Construction Inc. | Non-Minority | $52,928,005 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| 24 | Mill Basin Bridge Constructors Llc | Non-Minority | $51,792,491 | $0 | $9,691,964 | 18.7% |

| 25 | TDX Construction Corp. | Non-Minority | $51,678,028 | $0 | $0 | 0.0% |

| Total | $2,656,136,200 | $63,876,398 | $37,176,741 | 3.8% |

Source: Checkbook NYC. Includes mayoral and non-mayoral spending.

Implementing this approach would be beneficial for contracts with M/WBE subcontracting goals because it builds confidence that the prime vendor has committed resources and processes to ensuring M/WBE utilization on those contracts – rather than starting from scratch when presented with a goal. For procurements with M/WBE utilization goals, the City currently requires potential vendors to submit M/WBE utilization plans as part of their proposal or bid. This plan only calls for prospective vendors to make general commitments to meet M/WBE subcontracting goals and list the scope of work available for subcontractors. These plans are insufficient because they do not ask prospective vendors for proof of outreach to M/WBEs or a plan or strategy for meeting the goal.

Recommendation: The New York City Charter should be amended to include timeframes for each agency with a role in the contract review process, in order to alleviate the financial burden of contract delays on M/WBEs.

In order to ensure that agencies meet obligations to spend public funds fairly and with integrity, the procurement process involves important oversight from several agencies before contracts can be registered and vendors can be paid for contracted work. Up to five other agencies may play a role in reviewing contracts along several points in the procurement process to carry out tasks such as conducting public hearings and determining the financial strength and integrity of potential vendors. The agencies included in this due diligence process include the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services, Corporation Counsel, the Department of Investigation, the Office of Management and Budget, and the Division of Labor Services at the Department of Small Business Services. Following these reviews and upon execution of the contract by the City agency, the contract is then submitted for registration to the Office of the Comptroller, and upon registration the contract becomes legally implemented and the vendor may begin work and receive payment. However, it often takes longer than is feasible for vendors to wait to begin to work and get paid. In fact, the Comptroller’s Office recently released a report examining contracts submitted to the Comptroller’s Office for registration. In FY 2017, 81 percent of new and renewal contracts with prime vendors, were submitted to the Comptroller’s Office for registration after the contract start date had already passed.[li] The long contract review process especially disadvantages newer M/WBE firms that may have smaller operational budgets. Furthermore, those who serve as subcontractors must wait for additional layers of approval, because their primes’ contracts must be registered before they can get paid. Vendors are then left with a difficult choice between waiting to begin work, which stalls projects and drives up costs, or begin work without a contract, which causes significant risk and financial burden for vendors. Over the long term, contract delays discourage businesses, both minority and non-minority, from doing business with the City. As shown in Chart 7, 334 of the 484 M/WBE contracts, or 69 percent of new and renewal M/WBE prime contracts, arrived at the Comptroller’s Office after the contract start date, and 25 percent were delayed by at least 90 days. This means that one in four M/WBEs had to work for at least three months without a contract in place or wait three months after their contract start date to begin work. Overall, these delayed contracts were valued at a total of $203.3 million. They included goods such as chairs for office spaces, professional services such as asbestos investigations, standard services like welding, and construction such as scaffolding.

Chart 7: Length of Time between Start Date and Arrival for Registration

M/WBE New and Renewal Contracts Registered FY 2018

The Comptroller’s Office has advocated for timeframes that each agency in the contract review process must complete their work within. Currently, the Comptroller’s Office is the only agency with a role in the contract review and registration process that operates under a City Charter-mandated timeframe, which provides a 30-day deadline to complete registration. In order to make the process more efficient, transparent, and sustainable for all firms, the City Charter should be amended to require specific timeframes for each agency with an oversight role in the procurement process. Creating timeframes for all agencies in the procurement process will ensure that vendors have a predictable schedule of review and that agencies act in a timely manner, improving outcomes for vendors and the City alike. Another more sweeping step would be for the City to create a transparent contract tracking system, allowing vendors to view the status of their contracts as they move through the various stages of review. It would be enormously helpful to vendors if they could go online and find out if their contract is under review at the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services, the Law Department, or the Office of Management and Budget. If timeframes were implemented in conjunction with a tracking system – allowing vendors to learn which agency was reviewing their contract and how long the review would take – vendors would be better able to plan for future projects, manage their cash flow, and would likely achieve greater organizational stability.

The Comptroller’s Office has advocated for timeframes that each agency in the contract review process must complete their work within. Currently, the Comptroller’s Office is the only agency with a role in the contract review and registration process that operates under a City Charter-mandated timeframe, which provides a 30-day deadline to complete registration. In order to make the process more efficient, transparent, and sustainable for all firms, the City Charter should be amended to require specific timeframes for each agency with an oversight role in the procurement process. Creating timeframes for all agencies in the procurement process will ensure that vendors have a predictable schedule of review and that agencies act in a timely manner, improving outcomes for vendors and the City alike. Another more sweeping step would be for the City to create a transparent contract tracking system, allowing vendors to view the status of their contracts as they move through the various stages of review. It would be enormously helpful to vendors if they could go online and find out if their contract is under review at the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services, the Law Department, or the Office of Management and Budget. If timeframes were implemented in conjunction with a tracking system – allowing vendors to learn which agency was reviewing their contract and how long the review would take – vendors would be better able to plan for future projects, manage their cash flow, and would likely achieve greater organizational stability.

Acknowledgements

Comptroller Scott M. Stringer thanks Wendy Garcia, Chief Diversity Officer and Patricia Dayleg, Senior Advisor of Diversity Policy for leading the creation of this report. He also recognizes the important contributions made by: Alaina Gilligo, First Deputy Comptroller; Jessica Silver, Assistant Comptroller for Public Affairs & Chief of Strategic Operations for the First Deputy Comptroller; Zachary Steinberg, Deputy Policy Director; David Saltonstall, Assistant Comptroller for Policy; Michael D’Ambrosio, Agency Chief Contracting Officer; Mike Bott, Assistant Comptroller for Technology/Chief Information Officer; Edward Sokolowski, Executive Director of Systems Development and Program Management; Troy Chen, Executive Director of App Development and Web Administration; Ron Katz, Executive Director, Technology Support & Business Continuity; Archer Hutchinson, Graphic Designer; Lisa Flores, Deputy Comptroller, Contract Administration; Christian Stover, Bureau Chief, Contract Administration; Kathryn Diaz, General Counsel; Marvin Peguese, Deputy General Counsel; Amedeo D’Angelo, Deputy Comptroller for Administration; Bernarda Ramirez, Division Chief, Procurement Services; Adam Forman, Chief Data & Policy Officer; Elizabeth Bird, Policy Analyst; Brian Ceballo, Diversity Coordinator; and Nicole Sanchez, Summer Intern. Comptroller Stringer also recognizes the important contributions to this report made by the Advisory Council on Economic Growth through Diversity and Inclusion: Robert Abreu, Dominicans on Wall Street; Vincent Alvarez, New York City Central Labor Council; Pilar Avila, New America Alliance; Deborah Axt, Make the Road New York; Danielle Beyer, New America Alliance; Neeta Bhasin, ASB Communications; Derrick Brown, National Gay and Lesbian Chamber of Commerce New York; Jose Calderon, Hispanic Federation; Alejandra Y. Castillo, Minority Business Development Agency; Louis J. Coletti, Building Trades Employers’ Association; Kelvin Collins, MWBE Accelerator, Harlem Commonwealth Council; Reverend Jacques DeGraff, Canaan Baptist Church; Lloyd Douglas, Lloyd Douglas Consulting Company; Haze N. Dukes, NAACP New York State Conference; Jose Garcia, Surdna Foundation; Michael Garner, Metropolitan Transportation Authority; Dmitri Glinski, The Black Institute; Robert Greene, National Association of Investment Companies; Javier H. Valdes, Make the Road New York; Jay Hershenson, City University of New York; Jill Houghton, U.S. Business Leadership Network; Gary LaBarbera, Building and Construction Trades council of Greater New York; Bertha Lewis, The Black Institute; Rafael Martinez, New York State Coalition of Hispanic Chambers of Commerce; Annie Minguez, Good Shepherd Services; Marc Morial, National Urban League; Ana Oliveira, New York Women’s Foundation; Quentin Roach, Merck & Co.; Lillian Rodriguez Lopez, The Coca-Cola Company; Bazah Roohi, American Council of Minority Women; Reverend Al Sharpton, National Action Network; Hong Shing Lee, Chinatown Manpower Project; Ruben Taborda, Johnson & Johnson; Abigail Vazquez, Aspen Institute; Elizabeth Velez, Velez Organization; Bonnie Wong, Asian Women in Business; Joset B. Wright-lacy, National Minority Supplier Development Council; and Charles Yoon, Yoon & Kim LLP/Council of Korean Americans. Comptroller Stringer thanks the M/WBE community for important contributions to this report, including: Robert Alleyne, Allene Consulting Group; Dio Arias, Millennium Remanufactured Toners. INC.; Reginald Calan, Fortis Lux; Jill Crawford, Type A; Yocelyn Cubilette, MWBE Accelerator, Harlem Commonwealth Council; Frank Garcia, Millennium Remanufactured Toners. INC.; Anupam Gupta, Avenues International Inc.; Tisha Jackson, Tisha Jackson, Esq.; Yin Kon, InterGeneration Capital Management; Carter Lard, Penda Aiken, Inc.; Andrew Leung, Yu & Associates; Rafael Martinez, Republic Companies; Nancy Mattell, Mrktshare; Safia Mehta, Progress Investment Management Company; Peggy Miller, MHW Law Group; Collette Molton, QED, Inc.; Roxanne Neilson, Contractor Compliance LLC; Josefina Nidea, A & H Co.; Emmanuel Ola-Dake, Mola Group Corporation; Kecia Palmer-Cousins, Aeroba Soul; Mahendra Patel, MP Engineers; James Peterson, Eat Online; Donia Piersaint, Donia + Associates LLC; Jen Portland, Excel Rain Man; Fabiola Santos-Gaerlan, Honedew Drop Family of Childcare Services; Swaminathan Sethuraman, Resonance Consulting Solutions; Sanjay Shah, Paragon Management Group; Amira Strasser, Applied Research Investments; Norma Tan, CoraGroup; Cassandra Tennyson, Sublime Moment Events; Jeff Vigil, My Business Matches; Sydney Wayman, Optimal Management Solutions; Andis Woodlief, Contractor Compliance LLC; and Gil Young Jo, Kotrade Trade Investment Promotion Agency.

Endnotes

[i] “4 ways MBEs Impact the Nation’s Supply Chain,” Minority Business Development Agency, August 9, 2018: https://www.mbda.gov/news/blog/2018/08/4-ways-mbes-impact-nations-supply-chain.

[ii] United States Census Bureau. “2012-2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.”

[iii] City of New York, City of New York Disparity Study, May 30, 2018: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/mwbe/business/pdf/NYC-Disparity-Study-Report-final-published-May-2018.pdf.

[iv] “Mayor de Blasio Announces Bold New Vision for the City’s M/WBE Program,” September 28, 2016: https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/775-16/mayor-de-blasio-bold-new-vision-the-city-s-m-wbe-program/#/0.

[v] Mayor’s Office of Contract Services, 2018 Citywide Indicators Reports, How the City spends its money: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/mocs/reporting/citywide-indicators/how-the-city-spends-its-money.page. Mayor’s Office of Contract Services, 2018 Citywide Indicators Reports, Economic Opportunities for M/WBEs under Local law 1 of 2013: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/mocs/reporting/citywide-indicators/economic-opportunities-for-mwbe-under-local-law-1-of-2013.page.

[vi] City of Richmond v. J. A. Croson Co. 488 U.S. 469 (1989)

[vii] “Dinkins plan gives minority concerns more in contracts,” The New York Times, February 11, 1992: http://www.nytimes.com/1992/02/11/nyregion/dinkins-plan-gives-minority-concerns-more-in-contracts.html.

[viii] “Giuliani Revamps Minority Program on City Contracts,” The New York Times, January 25, 1994: http://www.nytimes.com/1994/01/25/nyregion/giuliani-revamps-minority-program-on-city-contracts.html.

[ix] New York City Council, Int. 0727-2005: https://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=444904&GUID=F981C035-E957-4306-887E-81E640208014&Options=ID|Text|&Search=727-a.

[x] Local Law 129 of 2005: http://www.nyc.gov/html/ddc/downloads/pdf/obo/law05129.pdf.

[xi] New York City Council, Int. 0911-2012: https://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=1189797&GUID=2729B38A-BC05-4393-9857-3295E345C694&Options=ID|Text|&Search=0911-a.

[xii] “Mayor de Blasio and Counsel to the Mayor and M/WBE Director Maya Wiley Launch Advisory Council on Minority and Women-Owned Business Enterprises,” December 14, 2015: https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/934-15/mayor-de-blasio-counsel-the-mayor-m-wbe-director-maya-wiley-launch-advisory-council-on.

[xiii] “Mayor de Blasio Announces Bold New Vision for the City’s M/WBE Program,” September 28, 2016: https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/775-16/mayor-de-blasio-bold-new-vision-the-city-s-m-wbe-program/#/0.

[xiv] “$1.8 Billion Ahead of Projections, Mayor de Blasio Announces New Goal to Award $20 Billion to M/WBEs by FY 2025,” May 30, 2018: https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/277-18/-1-8-billion-ahead-projections-mayor-de-blasio-new-goal-award-20-billion-to. “Mayor de Blasio, Deputy Mayor Thompson Launch Citywide Push to Help Minority And Women-Owned Business Enterprises Win Contracts,” September 28, 2018: https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/475-18/mayor-de-blasio-deputy-mayor-thompson-launch-citywide-push-help-minority-women-owned.

[xv] “$1.8 Billion Ahead of Projections, Mayor de Blasio Announces New Goal to Award $20 Billion to M/WBEs by FY 2025,” May 30, 2018: https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/277-18/-1-8-billion-ahead-projections-mayor-de-blasio-new-goal-award-20-billion-to.

[xvi] “De Blasio Administration Announces City Program Has Helped Minority and Women-Owned Businesses Secure $93.5 Million in City Contracts and Create Nearly 800 Jobs,” July 7, 2017: https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/461-17/de-blasio-administration-city-program-has-helped-minority-women-owned-businesses.

[xvii] “Mayor de Blasio Announces the First Ever Hiring of a Woman-Owned Financial Firm to Manage $100 Million of the City’s Deferred Compensation Plan,” March 30, 2018: https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/162-18/mayor-de-blasio-the-first-ever-hiring-woman-owned-financial-firm-manage-100.