Making the Grade 2020

Executive Summary

COVID-19 has raged through New York City, killing more than 23,800 people and sickening more than a quarter of a million city residents. At the outset of the pandemic, the city’s economy was all but locked down and has since re-opened only partially in an effort to stop the spread and protect lives, resulting in mass layoffs, lost income for hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers, and a dramatic drop in tax revenues. The pandemic disproportionately impacted minority- and women-owned businesses (M/WBEs) that already face structural inequalities resulting from a long history of discrimination. For instance, M/WBEs are less likely to gain financing and develop relationships with banks due to institutional racism. Because of this, when banks were charged with processing applications for federal COVID-19 relief, many MWBEs were automatically excluded.[1]

As a result, a July 2020 survey from New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer’s Office found that 85 percent of M/WBEs projected less than six months of survival.[2] This means that although 30 percent of all small business in New York City may permanently close as a result of the pandemic, firms owned by women and people of color were more vulnerable to closure.[3] The same dynamic has also played out on the national stage. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that between February and April 2020, African American business ownership fell by 41 percent, Latino business ownership dropped by 32 percent, Asian-owned business ownership declined by 26 percent, and women business ownership fell by 25 percent in comparison to white business ownership which decreased by 17 percent.[4]

The City has the ability to alleviate these challenges by doing business with firms owned by women and people of color. A strong M/WBE program will be essential to the City’s fiscal, economic, and social health as it recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic.

This report, published annually since 2014 by the Office of New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, evaluates the performance of the City’s M/WBE program and makes recommendations for its improvement. For the past six years, Comptroller Stringer has called for a Chief Diversity Officer in City Hall and within every City agency. These officers would serve as executive-level diversity and inclusion strategists, driving the representation of people of color and women across government.

In July 2020, Mayor Bill de Blasio signed an executive order to appoint Chief Diversity Officers in every City agency.[5] The executive order also implements several of Comptroller Stringer’s previous recommendations, such as:

- Expanding the universe of M/WBE-eligible contracts (recommended in 2014);

- Re-evaluating subcontracting goals (recommended in 2017);

- Breaking up large contracts (recommended in 2017); and

- Increasing usage of the M/WBE Small Purchase Method (discussed in 2019).[6]

Comptroller Stringer’s Office also introduced new transparency and accountability measures in the contracting process. In July 2020, the Comptroller’s Office announced that its contract registration process will include a rigorous review of M/WBE goals on all City contracts.[7]

The Comptroller’s Office continues monitoring M/WBE utilization through this report, and the findings are below.

Citywide Utilization of M/WBEs

Comptroller Stringer’s Making the Grade report compares spending to the City’s goals under Local Law 1 of 2013. The M/WBE law is based on constitutionally required disparity studies finding that M/WBEs receive a disproportionately small share of City contracts. In order to address these disparities, the City sets citywide participation goals for certain contracts across four industries: construction, professional services, goods, and standard services.

In October 2019, based on the City’s latest disparity study, the New York City Council updated M/WBE goals and introduced goals for Native Americans across all industries and Asian Americans in professional services.[8] These changes took effect in April 2020. However, this report’s grades are based on the original Local Law 1 goals because spending during the fiscal year may have come from contracts registered before the law was updated and new goals were implemented. In addition, the grades are based on actual spending in FY 2020, rather than the value of contracts awarded during the fiscal year, because contracts awarded may or may not result in M/WBEs actually receiving payments from the City.

This year’s report includes several major findings:

- The City awarded $22.5 billion in contracts in FY 2020, of which only $1.1 billion (equal to 4.9 percent) were awarded to M/WBEs.

- Over the last seven years, the share of certified M/WBEs receiving City dollars has not exceeded 22 percent. In FY 2020, 82 percent of certified M/WBEs did not receive any spending from the City.

- For the first time, the City exceeded $1 billion with M/WBEs in FY 2020, an additional $93 million from FY 2019.

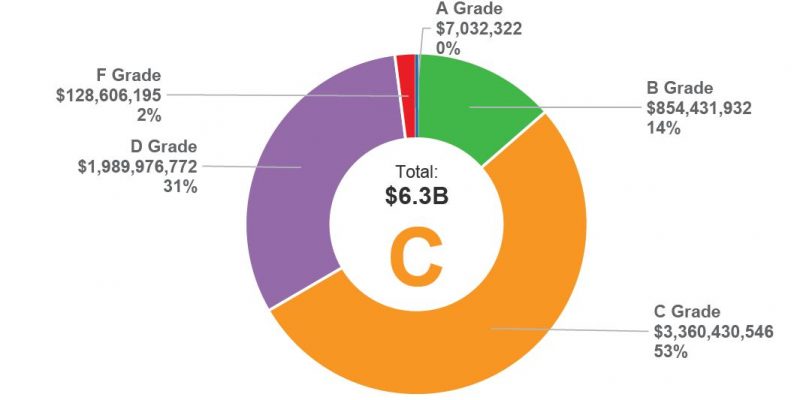

- The City earned its second consecutive “C” grade for M/WBE spending in FY 2020Broken down by category, it earned an “F” with African Americans, a “D” with women, a “B” with Hispanic Americans, and an “A” with Asian Americans.

- Overall, in FY 2020, 21 grades remained the same, six agencies improved their grades, and five agency grades declined. This means that 80 percent of agency grades either stagnated or declined.

- Three mayoral agencies earned “A” grades: the Commission on Human Rights, Department for the Aging, and the Department of Youth and Community Development, all of which spent more than 50 percent of their Local Law 1-eligible dollars with M/WBEs.

- Meanwhile, one agency, NYC Emergency Management, received an “F” grade, spending less than 4 percent of its Local Law 1-eligible dollars with M/WBEs.

- The Comptroller’s Office earned an “A” grade. Over the last seven years, Comptroller Stringer’s Office increased its M/WBE spending from 13 percent to approximately 50 percent, with a 13 percent point increase just in the last year. By contrast, the City increased its spending from six percent to 16 percent since FY 2014—just a ten percent increase in seven years.

Utilization of M/WBEs During

In addition to Local Law 1 spending, this report reviews spending specifically related to New York City’s COVID-19 response and recovery. In July 2020, the New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer’s Office surveyed 500 M/WBEs on the impact of COVID-19, finding that 65 percent of M/WBEs expressed being ready, willing, and able to assist in the City’s response efforts. Despite this, only 62 M/WBEs surveyed actually competed for a contract and only 10 received a contract. This report follows up on that survey, finding that:

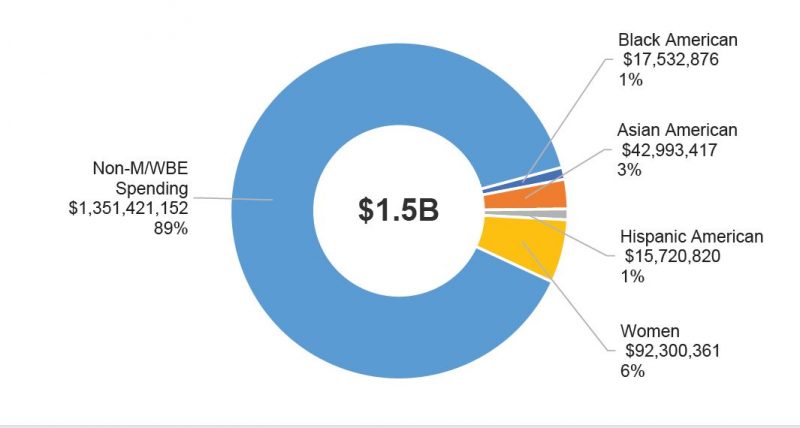

- Between March and August 2020, the City spent more than $1.5 billion for COVID-19-related goods and services contracts, yet only 11 percent, or $168.5 million, went to M/WBEs.

- Specifically, the City has spent about $92.3 million, or about six percent, with women-owned businesses; $43 million, or three percent with Asian American-owned businesses; about $17.5 million, or one percent with Black American-owned firms; and about $15.7 million, or one percent, with Hispanic American-owned firms.

- Three agencies have made up more than 80 percent of the City’s COVID-19 related spending and each had limited M/WBE utilization. The Department of Citywide Administrative Services spent more than $613 million on COVID-19 related goods and services and just nine percent went to M/WBEs. The Department of Sanitation spent more than $473 million and just 14 percent went to M/WBEs. And NYC Emergency Management spent more than $181 million on COVID response yet a mere one percent was spent with M/WBEs.

- Three entities have spent $0 in COVID-19 related procurement with M/WBEs: Health + Hospitals Corporation, the Office of the Mayor, and the Department of Parks and Recreation.

Department of Education Utilization of M/WBEs

This year, for the first time, the Making the Grade report analyzes the New York City Department of Education’s (DOE) spending and its impact on M/WBEs. DOE is not graded because it is not subject to Local Law 1 or City procurement rules. However, it is important to understand DOE’s M/WBE utilization because it spends more than $4 billion annually, more than any agency graded in this report. In fact, DOE spending is comparable in size to Delaware’s state budget. Comptroller Stringer’s analysis finds that:

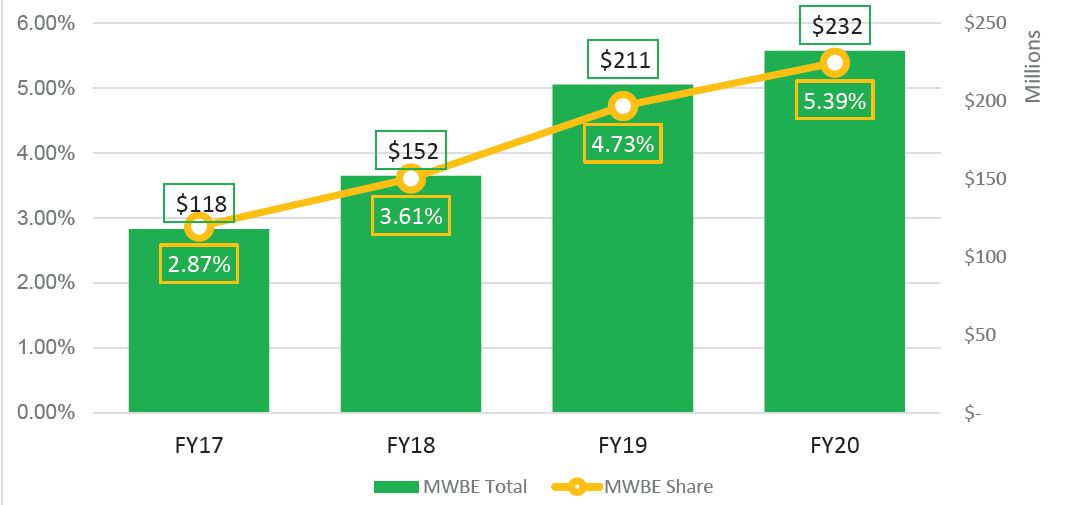

- In FY 2020, of their $4.3 billion in spending, less than six percent, or $232.3 million, went to M/WBEs.

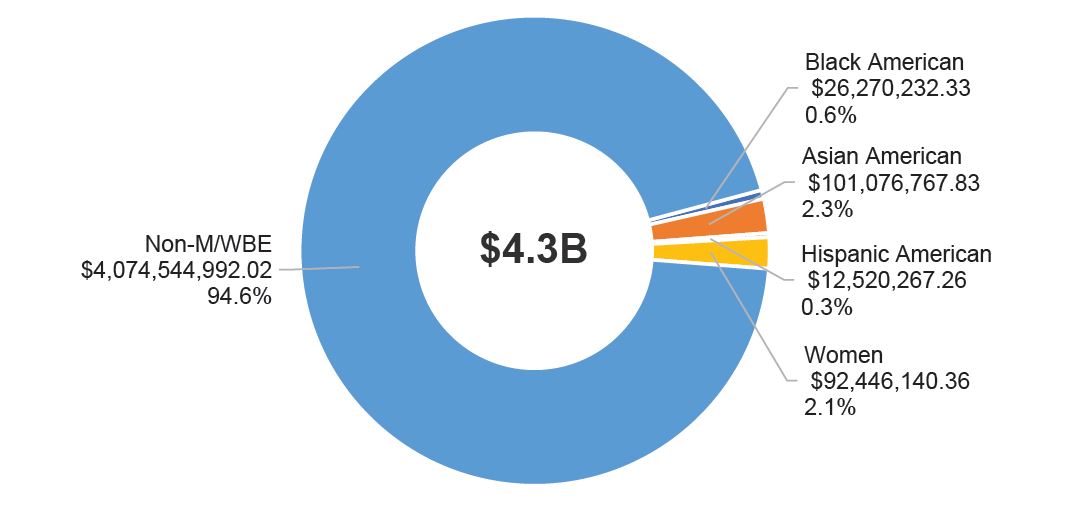

- Asian American-owned businesses received $101 million or 2.4 percent of spending, women-owned firms received about $92.4 million, or about 2.1 percent of spending; Black American-owned businesses

- DOE’s spending was divided among more than 8,000 vendors. However, the top 50 recipients of DOE procurement dollars—all non-M/WBEs —received $1.8 billion, or about 42 percent of all DOE spending.

- Within the top 50 vendors, 22 were school bus companies, receiving a total of $960 million; four food companies received a total of $162 million; four information technology firms received $149 million; one firm provided legal services for $94 million, and two provided surety bonds at $83 million.

- A search of the City’s M/WBE directory yields M/WBEs in every one of DOE’s top procurement industries, representing a missed opportunity to do business with M/WBEs.

Utilization of M/WBEs through the M/WBE Small Purchase Method

For the second consecutive year, Comptroller Stringer’s Office has analyzed spending using the M/WBE Small Purchase Method. The New York State Legislature and the New York City Procurement Policy Board increased the amount the City can spend through this purchase method from $150,000 to $500,000 starting in January 2020, expanding upon a 2017 effort to create more M/WBE opportunities through discretionary purchases.[9] This report finds that:

- Spending through the M/WBE Purchase Method comprised just one percent of the City’s Local Law 1-eligible spending.

- Ninety-six percent of M/WBEs did not receive any spending through the M/WBE Purchase Method. Just 432 firms received spending through this opportunity.

- Spending with Hispanic Americans using the M/WBE Small Purchase has fallen by $600,000 since FY 2019, but businesses owned by African Americans, Asian Americans, and women saw increases in spending through the M/WBE Small Purchase.

- Despite the expanded M/WBE Small Purchase rule being in place for a full six months, only two agencies, the Comptroller’s Office and the Department of Citywide Administrative Services, exceeded $150,000 using the M/WBE Small Purchase Method.

- After two years with the M/WBE Small Purchase rule in place and an expansion of the rule, ten agencies still spent less than one percent of their dollars using the M/WBE Small Purchase Method.

- At the agency level, eight agencies spent more than 10 percent of their budget using the M/WBE Purchase Method.

- Overall, the City saw increased utilization of the M/WBE Small Purchase Method in FY 2020, spending about $63.7 million across 1,171 contracts, an increase of about $21.3 million over 2019.

- Ten M/WBE vendors generated more than $1 million in revenue through this opportunity, more than half of which were in the field of technology.

Recommendations

Each year, Comptroller Stringer puts forth recommendations meant to reduce barriers and increase opportunities for M/WBEs. These recommendations are informed by needs identified by the Comptroller’s COVID-19 M/WBE survey, as well as a series of focus groups. Comptroller Stringer recommends that:

- The City needs to take a more finely tuned approach to M/WBE spending. The Mayor’s Task Force on Racial Equity and City Hall should develop a targeted plan to address areas where there is low M/WBE utilization even with M/WBE availability: spending within the Department of Education, COVID-19-related procurements, and the M/WBE Small Purchase Method. This report identifies key imbalances in spending within the DOE and COVID-19 related purchases. It is clear that the supply chain in the City of New York needs to be closely examined with an eye toward reform at every step in the process. For example, in order to take full advantage of the M/WBE Small Purchase Method, the City should review the procurements needs of each agency. For every upcoming procurement below $500,000, including new and renewal contracts, the City should identify M/WBE Small Purchase opportunities.

- The City should establish an initiative to pay M/WBEs and small businesses for their upfront overhead costs. As women and people of color face uncertain futures and small businesses across the country are closing their doors, the City should implement payment policies that support its vendors’ sustainability. Upfronting overhead costs is established precedent in many types of contracts. For example, within the construction industry, the City offers mobilization payments to cover the costs of significant initial expenses required by their contract as well as other mandates imposed by City, State, or federal law, such as performance and payment bonds, insurance, or office spaces. The City should make payments for upfront overhead costs available to more vendors including M/WBEs and small businesses with contracts in the professional services, standard services, and goods industries. As a matter of course, any new or expanded payment policies should mirror due diligence practices to protect taxpayer dollars. In considering upfront overhead payments for M/WBEs, New York City can follow the lead of some federal and state agencies that have these policies in place, among them the U.S. Department of Energy, Colorado, Texas, and Louisiana.

- The City should require transparent timelines for RFP awards and notify vendors that did not receive awards of their option to debrief. Vendors currently wait for several months or even more than a year for RFP results. This costs M/WBEs valuable capital and time to maintain the staff and equipment required for such contracts without knowing if and when their goods and services will be needed. T For each RFP, the City should business practices.

- City Hall should immediately sign an executive order requiring unconscious bias training for all employees, or else the City Council should mandate it.

The City currently offers these trainings on an optional basis, but there is no standard requirement for all employees. The City has historically added to its repertoire of required trainings in response to important issues. For example, the City passed legislation requiring anti-sexual harassment trainings for all employees in response to the #MeToo and Time’s Up movements. Likewise, an executive order requiring training for all supervisory and frontline staff on transgender diversity and inclusion was implemented in the midst of policies discriminating against transgender and gender non-conforming people in states such as North Carolina. Using existing resources at the Department of Citywide Administrative Services Training Center and Office of Citywide Equity and Inclusion, the City should train all public servants to address their unconscious biases to ensure that the City’s everyday interactions improve the lives of all New Yorkers, including reducing contracting barriers facing the M/WBE community. This is especially critical because of the White House’s recent defunding of anti-racism trainings for federal employees. - Federal, state, and local governments should revive M/WBE programs by creating set asides and tying M/WBE goal outcomes to cabinet-level performance. All M/WBE programs are based primarily on two Supreme Court decisions, City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co. (Croson) and Adarand Constructors Inc. v. Peña (Adarand), which require cities to calculate availability and utilization of M/WBEs in their local market. These cases have led to the goal-based, aspirational programs that we see nationwide. However, while these policies have created some access, they have been unable to address systemic racism in government more broadly. As a result, as Comptroller Stringer’s Office has shown over the last six years, the needle has not moved: M/WBEs still only receive five percent of New York City contract dollars. In order to truly address inequities in government contracting, cities need to address societal racism more broadly and that requires action from federal, state, and local governments and the Supreme Court. Comptroller Stringer found that the Supreme Court was wrong when it said, “the dream of a Nation of equal citizens in a society where race is irrelevant to personal opportunity and achievement would be lost in a mosaic of shifting preferences based on inherently unmeasurable claims of past wrongs.”10 In fact, it is not only that government has the responsibility to remedy the impact of racism, it has the power to do so. State and local governments should create programs that consider the M/WBE market first. For example, Ohio has a program to set aside 15 percent of purchases each year where only M/WBEs can compete, with no limit on any given contract amount. In addition, governments should take steps to hold their decision makers accountable by tying M/WBE goals to their employee performance evaluations and establish improvement processes when decision makers underperform.

The Road to a Chief Diversity Officer

For the past six years, Comptroller Stringer has called for a Chief Diversity Officer in City Hall and within every City agency. These officers would serve as executive-level diversity and inclusion strategists, driving the representation of people of color and women across government. In 2019, Comptroller Stringer’s Office championed a Charter Revision proposal to appoint a Chief Diversity Officer who would report directly to the Mayor. Ultimately, the Charter Revision Commission amended the proposal to codify the current M/WBE Director in the Charter. New Yorkers voted to approve the amended proposal in November 2019.

In July 2020, after years of coordinated pressure, Mayor Bill de Blasio signed an executive order to appoint Chief Diversity Officers in every City agency in order to expand contracting opportunities for small businesses in the M/WBE program, particularly in the 27 neighborhoods hardest hit by COVID-19.[12] The executive order implemented several of Comptroller Stringer’s previous recommendations, such as:

- Establishing a Chief Diversity M/WBE Officer in all City agencies reporting directly to commissioners (recommended in 2018 and 2019).[13] This was implemented in August 2020 with a list of agency Chief Diversity Officers on the City’s website;[14]

- Expanding the universe of M/WBE-eligible contracts, including emergency procurements (recommended in 2014);

- Re-evaluating subcontracting goals for upcoming ending contracts (recommended in 2017);

- Identifying existing contracts over $25 million that can be broken up into smaller contracts (recommended in 2017); and

- Increasing usage of the M/WBE Small Purchase Method (discussed in 2019).[15]

Along with the Executive Order, the City and its COVID-19 Taskforce on Racial Equity and Inclusion announced three initiatives to support small businesses in the hardest-hit neighborhoods: a talent matching program to expand access to contracts for businesses in black and brown communities; a pro-bono business consultant corps to provide strategy and operations planning and support; and a mentorship network to help launch and grow business.[16] Despite the City‘s decision not to appoint a Chief Diversity Officer within City Hall reporting directly to the Mayor, we are hopeful that the City’s new policies and structures will improve M/WBE participation at each agency.

New York City’s M/WBE Program

New York City’s M/WBE Program began in the 1990s after the City’s first disparity study found that businesses owned by women and people of color received far fewer City contracts than those owned by white men. It received renewed focus in 2015 when Mayor de Blasio announced a goal of awarding $16 billion in contracts by 2025. Since then, the City has increased its goal to $25 billion.[17] A timeline of New York City’s M/WBE program is reflected in Chart 1.

The M/WBE program is governed by Local Law 1, which the City Council updated in October 2019 based on the City’s latest disparity study. The law sets citywide participation goals for minority groups on City contracts across four industries: professional services, standard services, goods, and construction. The 2019 changes to the law include updated goals across most categories, and new goals for Native Americans across all industries and Asian Americans in professional services.[18]

The City and State announced several new initiatives and administrative actions impacting M/WBEs’ ability to compete for contracts in FY 2020. A history of the program and the City’s more recent steps are described below:

Timeline

2020

New York City announced certifying over 10,000 M/WBEs. Mayor de Blasio signed Executive Order establishing Chief Diversity Officers within every city.[29]

2019

New York City reaches goal of certifying 9,000 M/WBEs . Local Law 174 was enacted, adding goals for Native Americans across all industries and Asian Americans in professional services. The new law also increases the maximum goods contracts subject to the program from $100K to $1 million.[28]

2018

Third NYC disparity study was commissioned, showing increased availability yet continued underutilization of M/WBEs. Mayor de Blasio increased the City’s goal to award a minimum of $20 billion in City contracts to M/WBEs by 2025.[27]

2016

Mayor de Blasio created the Mayor’s Office of M/WBEs and set goals of certifying 9,000 M/WBEs by 2019 and awarding 30 percent of City contracts to M/WBEs by 2021.[26]

2015

Mayor de Blasio set a goal of awarding a minimum of $16 billion in City contracts to M/WBEs by 2025.[25]

2013

Local Law 1 was enacted, updating M/WBE program goals from 2005 and lifting the $1 million cap on contracts subject to aspirational goals.[24]

2005

Local Law 129 was enacted, re-establishing the M/WBE program with aspirational M/WBE goals on contracts between $5,000 and $1 million.[23]

2004

Second NYC disparity study was commissioned, showing continued underrepresentation of M/WBEs in City contracts.[22]

1994

- Mayor Giuliani eliminated the 10 percent allowance and stating that the process must become “ethnic-, race-, religious-, gender- and sexual orientation neutral.”[21]

- NYC’s first M/WBE program ended.

1992

- First NYC disparity study commissioned, finding that M/WBEs had a disproportionately small share of City contracts.

- Mayor Dinkins created NYC’s first M/WBE program, directing 20 percent of City procurement to be awarded to M/WBEs and allowing the City to award contracts to M/WBEs with bids 10% higher than the lowest bids.[20]

1989

US Supreme Court ruling, City of Richmond vs. J.A. Croson Co., held that in order to establish an M/WBE program, a municipal government needs to show a statistical evidence of a disparity existing between businesses owned by men, women and persons of color.[19]

New York City Administrative Actions Impacting M/WBEs

February 2020 – Resources for Women Entrepreneurs

NYC Department of Small Businesses Services (SBS) announced additional resources specifically geared towards women-owned businesses, including the launch of NewVenture 50+, a program for women over 50 years old to launch their own businesses.[30]

August 2020 – Growing the Pool of Certified M/WBEs

New York City announced that it certified 10,000 M/WBEs. The announcement builds on the City’s 2016 goal to certify 9,000 M/WBEs, which it achieved in 2019.[31]

August 2020 – Resources for Black Entrepreneurs

The City announced resources specifically targeted towards Black entrepreneurs, including one-on-one consulting; education in financing and business; help with establishing virtual storefronts; and an accelerator to provide meeting space and technical assistance for local Black-owned businesses.[32]

New York State Administrative Actions Impacting M/WBEs

January 2020 –Improvements to State M/WBE Certification Process

The State announced streamlining the M/WBE certification process and the creation of a Statewide Integrated M/WBE Application Portal. The State also announced additional improvements to the M/WBE certification process, including: extending M/WBE certifications from three years to five years, reducing the application review process timeline, and providing increased technical assistance to businesses as they navigate the certification process.[33] Comptroller Stringer previously recommended that the City and State streamline the M/WBE certification process and move towards a single platform for certification.[34]

M/WBE Contract Awards: M/WBEs Received Only 4.9 Percent of Procurement Awards

Each year, the City of New York releases an M/WBE compliance report and the Agency Procurement Indicators Report outlining the City’s utilization with M/WBEs and activities to increase contracting with M/WBEs. This year, the City reported $1.1 billion in M/WBE contract awards, a $96 million increase from FY 2019. These awards represent 27.9 percent of contracts within the M/WBE program (subject to Local Law 1), which totaled $3.95 billion.[35]

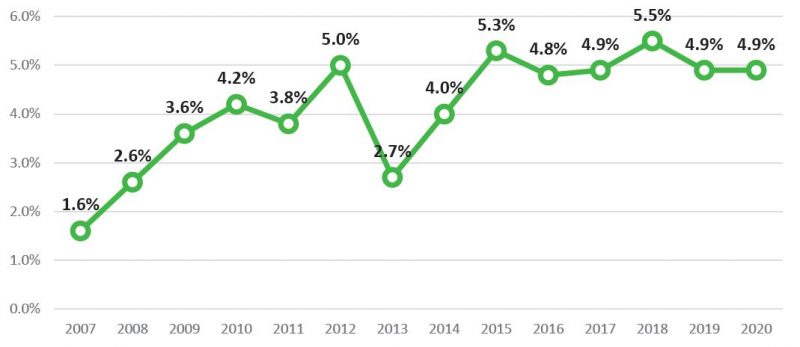

However, as shown in Chart 2, M/WBE awards represent only 4.9 percent of all procurement awards in FY 2020, which was $22.5 billion. Comptroller Stringer has previously recommended that the City expand the universe of contracts and vendors that can participate in the M/WBE program and Emerging Business Enterprise (EBE) program including . New York City has since set goals of awarding $25 billion to M/WBEs across all mayoral and non-mayoral agencies.[36]

In July 2020, Office announced that the Comptroller’s registration process will now include a rigorous review of M/WBE goals on all City contracts. The Comptroller’s Office will require agencies to provide documentation of their M/WBE goals, such as goal-setting worksheets and market analyses. This new transparency and accountability measure will allow for clarity and insight into the City’s M/WBE contracting targets and help identify areas for improvement.[37]

Chart 2: M/WBE Share of City Procurement, FY 2007 – FY 2019

Source: Mayor’s Office of Contract Services Agency Procurement Indicators: Fiscal Years 2007 to 2020.

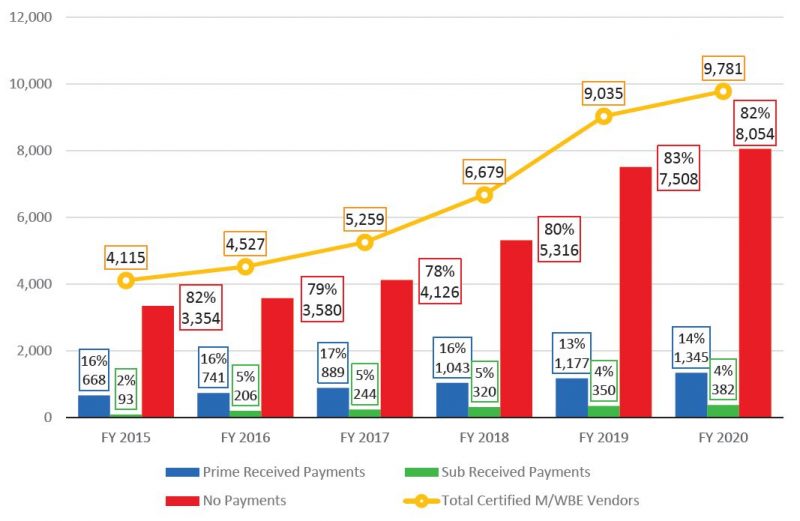

Spending and Certification: 83 Percent of M/WBEs Did Not Receive City Dollars in FY 2020

Despite the pandemic, the City has taken significant steps to expand its database of diverse vendors, certifying almost 10,000 M/WBEs by FY 2020. However, the portion of certified M/WBEs that receive a contract and get paid still remains low. As shown in Chart 3, the number of certified M/WBEs receiving payments from City contracts increased by just 196 firms while the number of certified M/WBEs jumped by 836 firms. This means that 82 percent of M/WBEs did not receive any City spending in FY 2020. Chart 3 also shows that over the last seven years, the share of M/WBEs receiving City dollars has not exceeded 22 percent.

Additionally, Chart 3 shows the share of M/WBEs receiving payments as prime contractors and subcontractors. The share of M/WBEs receiving prime contract payments increased from 13 percent to 14 percent in FY 2020. The share of M/WBEs receiving subcontractor payments remained at four percent in FY 2020.

Chart 3: Share of Certified M/WBE Receiving Spending, FY 2015 – FY 2020

Citywide Grades: Maintaining a “C” Grade

The Making the Grade report evaluates mayoral agencies that are subject to City M/WBE participation goals. It’s worth noting that the City Council updated the goals in the M/WBE law, Local Law 1, in October 2019 and these updates took effect in April 2020.[38]

However, the grades in this report are based on the original Local Law 1 goals, not the amended ones, because spending during the fiscal year may have come from contracts registered before the law was updated and new goals were implemented. In addition, the grades are based on actual spending in FY 2020, rather than the value of contracts awarded during the fiscal year, because contracts awarded may or may not result in M/WBEs actually receiving payments from the City. Emergency procurement spending that otherwise falls within Local Law 1, such as spending within the professional services industry, is included in this analysis given the City’s Executive Order stating that “all City agencies conducting procurements necessary to respond to the ongoing State of Emergency shall not categorically exempt emergency contracts from MWBE participation goals.”[39]

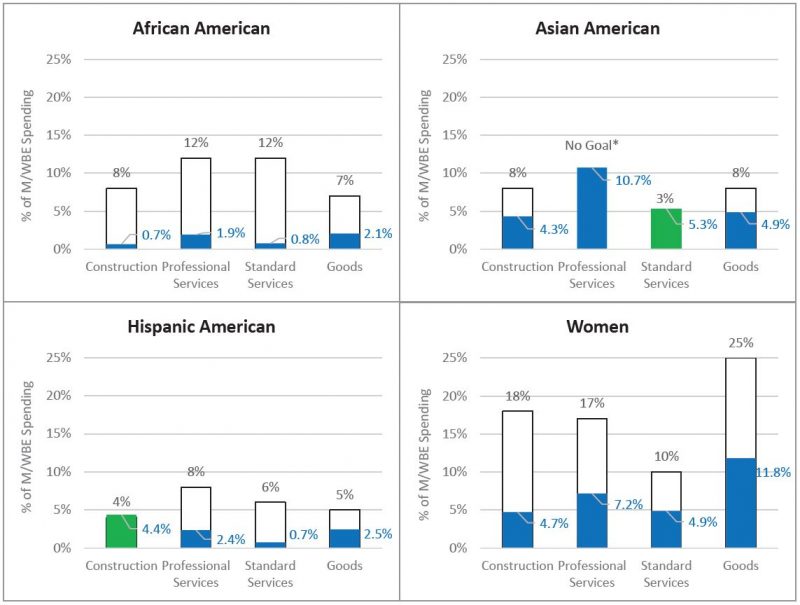

For the first time, the City exceeded $1 billion in spending with M/WBEs in FY 2020, an additional $93 million from FY 2019. This earned the City its second consecutive “C” grade in FY 2020 for M/WBE spending, after maintaining a “D+” grade for four years. Broken down by category, the City received an “F” with African Americans, a “D” with women, a “B” grade with Hispanic Americans, and an “A” grade with Asian Americans.

For the third year in a row, the Comptroller Stringer’s Office provided Citywide Progress Reports, a tool City agencies can use to help track their spending with M/WBEs throughout the fiscal year. These progress reports provide an analysis of each agency’s spending by minority group and industry compared with Local Law 1 goals. As shown in Chart 4, citywide M/WBE spending across industries remained largely stagnant in FY 2020, with some improvements. The City met its three percent Local Law 1 goal in standard services with Asian Americans, as it did in FY 2019. It also met its four percent Local Law 1 goal in construction with Hispanic Americans for the first time. All other Local Law 1 goals remain unmet.

Chart 4: Citywide M/WBE Spending Compared with Local Law 1 Goals, FY 2020

Source: Checkbook NYC.

Agency Grades: 80 Percent of Agency Grades Either Stagnated or Declined

In FY 2020, of the 32 mayoral agencies graded, three received an “A,” 12 received a “B,” 12 received a “C,” four received a “D,” and one received an “F” grade. While not a mayoral agency, the Comptroller’s Office is graded annually in this report and earned its second consecutive “A” grade in FY 2020, spending approximately 50 percent of its Local Law 1-eligible dollars with M/WBEs.

Two agencies – the Commission on Human Rights and the Department for the Aging – received their fourth consecutive “A” grades, and the Department of Youth and Community Development earned their first “A” grade. All three “A” grade agencies spent more than 50 percent of their Local Law 1-eligible dollars with M/WBEs. Eight agencies – the Administration for Children’s Services, Departments of Cultural Affairs, Probation, Parks and Recreation, and Small Business Services, the Landmarks Preservation Commission, Police Department, and Taxi and Limousine Commission – maintained their “B” grades from FY 2019.

Three agencies increased their grades from “C” to “B”: the Civilian Complaint Review Board, the Department of Housing Preservation, and Development and the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings. The Departments of Environmental Protection and Finance increased their grades from “D” to “C.” Eight agencies maintained their “C” grades: the Business Integrity Commission, Human Resources Administration, Law Department, and the Departments of Consumer and Worker Protection, Design and Construction; Buildings, and Correction. The Departments of Citywide Administrative Services, Transportation, and Sanitation all maintained “D” grades in FY 2020.

Five agencies saw their grades decrease. The Department of Health and Mental Hygiene dropped from an “A” grade to a “B” and the Departments of City Planning and Information Technology and Telecommunications decreased from “B” to “C” grades. The Department of Homeless Services declined from a “C” grade to a “D” Grade, and the NYC Emergency Management, which earned a “C” grade in FY 2019, dropped to an “F” in FY 2020, spending less than 4 percent of their Local Law 1-eligible dollars with M/WBEs. This is the only “F” grade for this year.

Overall, in FY 2020, six grades improved, 21 grades remained the same, and five declined. This means that 80 percent of agency grades either stagnated or declined.

Chart 5 shows that the City maintained a “C” because of the collective stagnation of spending with M/WBEs. The 17 agencies that received “C,” “D,” and “F” grades account for 86 percent of the City’s total M/WBE program spending, while the 15 agencies that received “A” and “B” grades account for less than 15 percent. Growth to an “A” grade would require additional improvement in M/WBE spending among the agencies with the highest proportion of the City’s Local Law 1-eligible procurement spending.

Table 1 provides each agency’s assigned grade and compares grades from FY 2020 to the last six fiscal years.

Chart 5: Composition of Citywide M/WBE Grade by Total Agency Spending, FY 2020

Source: Checkbook NYC.

Table 1: Comparison of FY 2014 – FY 2020 Grades

| Agency Name | FY14 | FY15 | FY16 | FY17 | FY18 | FY19 | FY20 | FY19-FY20 |

| New York City | D | D | D | D | D | C | C | – |

| Office of the Comptroller | C | C | B | B | B | A | A | – |

| Commission on Human Rights | C | C | B | A | A | A | A | – |

| Department for the Aging | D | C | B | A | A | A | A | – |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | C | C | C | B | C | B | A | ▲1 |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | C | C | C | B | A | A | B | ▼1 |

| Administration for Children’s Services | C | C | C | C | C | B | B | – |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | B | C | C | B | B | B | B | – |

| Department of Probation | C | D | D | C | B | B | B | – |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | D | C | C | B | B | B | B | – |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | B | B | C | B | C | B | B | – |

| Police Department | C | B | B | – | ||||

| Department of Small Business Services | D | F | B | A | C | B | B | – |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | D | D | D | B | B | B | B | – |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | C | C | D | B | B | C | B | ▲1 |

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | D | A | A | B | C | C | B | ▲1 |

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | D | C | D | C | C | C | B | ▲1 |

| Department of City Planning | C | C | B | C | C | B | C | ▼1 |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | F | D | D | D | C | B | C | ▼1 |

| Business Integrity Commission | D | D | F | C | D | C | C | – |

| Department of Consumer and Worker Protection | D | C | B | B | B | C | C | – |

| Department of Design and Construction | D | C | D | D | C | C | C | – |

| Department of Buildings | D | D | F | F | D | C | C | – |

| Department of Correction | D | D | C | D | C | C | C | – |

| Fire Department | D | D | C | C | C | C | C | – |

| Human Resources Administration | D | D | D | D | D | C | C | – |

| Law Department | C | D | C | D | C | C | C | – |

| Department of Environmental Protection | F | F | D | D | D | D | C | ▲1 |

| Department of Finance | F | D | C | D | D | D | C | ▲1 |

| Department of Homeless Services | D | D | D | D | D | C | D | ▼1 |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | D | D | D | F | F | D | D | – |

| Department of Transportation | D | D | D | F | D | D | D | – |

| Department of Sanitation | F | F | F | F | D | D | D | – |

| NYC Emergency Management | D | D | D | D | D | C | F | ▼2 |

Table 2: Agency Grades with African Americans by Industry

| Agency Name | African American | Construction | Professional | Standard | Goods |

| Citywide | F | F | F | F | D |

| Office of the Comptroller | A | N/A | C | B | A |

| Commission on Human Rights | A | N/A | A | A | A |

| Department for the Aging | A | F | B | F | A |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | A | F | A | F | A |

| Department of Small Business Services | A | A | A | A | D |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | A | N/A | A | F | A |

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | B | N/A | F | F | A |

| Department of Probation | C | N/A | F | F | A |

| Administration for Children’s Services | D | F | C | D | B |

| Department of Consumer and Worker Protection | D | N/A | F | B | A |

| Department of Correction | D | F | F | D | A |

| Department of Finance | D | F | F | F | A |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | D | F | F | F | A |

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | D | F | D | B | D |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | D | D | F | F | D |

| Police Department | D | D | D | F | C |

| Business Integrity Commission | F | N/A | F | F | F |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | F | N/A | F | F | F |

| Department of Buildings | F | F | F | F | C |

| Department of City Planning | F | F | F | F | D |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Design and Construction | F | F | D | A | D |

| Department of Environmental Protection | F | F | F | F | B |

| Department of Homeless Services | F | F | F | F | B |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | F | N/A | F | F | A |

| Department of Sanitation | F | F | F | F | D |

| Department of Transportation | F | F | F | F | A |

| Fire Department | F | F | D | F | A |

| Human Resources Administration | F | F | F | F | F |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | F | F | F | F | C |

| Law Department | F | N/A | F | D | C |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | F | F | F | F | D |

| NYC Emergency Management | F | F | F | F | D |

Table 3: Agency Grades with Asian Americans by Industry

| Agency Name | Asian American | Construction | Professional | Standard | Goods |

| Citywide | A | C | No Goal | A | B |

| Office of the Comptroller | A | N/A | No Goal | D | A |

| Administration for Children’s Services | A | F | No Goal | A | A |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | A | N/A | No Goal | F | A |

| Commission on Human Rights | A | N/A | No Goal | A | C |

| Department for the Aging | A | F | No Goal | A | A |

| Department of City Planning | A | F | No Goal | A | B |

| Department of Consumer and Worker Protection | A | N/A | No Goal | A | F |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | A | A | No Goal | F | A |

| Department of Finance | A | A | No Goal | A | A |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | A | F | No Goal | D | A |

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | A | A | No Goal | A | A |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | A | N/A | No Goal | A | A |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | A | A | No Goal | A | B |

| Department of Probation | A | N/A | No Goal | B | A |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | A | N/A | No Goal | A | A |

| Fire Department | A | F | No Goal | A | A |

| Human Resources Administration | A | A | No Goal | A | A |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | A | A | No Goal | F | B |

| Law Department | A | N/A | No Goal | A | A |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | A | F | No Goal | C | A |

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | A | N/A | No Goal | C | A |

| Police Department | A | A | No Goal | A | A |

| Department of Buildings | B | F | No Goal | C | A |

| Department of Homeless Services | B | A | No Goal | D | A |

| Department of Design and Construction | C | D | No Goal | A | A |

| Department of Environmental Protection | C | D | No Goal | C | A |

| Business Integrity Commission | D | N/A | No Goal | F | C |

| Department of Correction | D | F | No Goal | F | A |

| Department of Sanitation | D | A | No Goal | F | B |

| Department of Small Business Services | D | F | No Goal | D | D |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | F | B | No Goal | D | F |

| Department of Transportation | F | F | No Goal | D | A |

| NYC Emergency Management | F | A | No Goal | F | A |

Table 4: Agency Grades with Hispanic Americans by Industry

| Agency Name | Hispanic American | Construction | Professional | Standard | Goods |

| Citywide | B | A | D | F | C |

| Office of the Comptroller | A | N/A | A | D | A |

| Administration for Children’s Services | A | A | C | A | A |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | A | N/A | F | C | A |

| Department for the Aging | A | A | A | A | A |

| Department of Buildings | A | F | A | F | A |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | A | A | F | F | F |

| Department of Design and Construction | A | A | B | A | A |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | A | A | F | F | A |

| Department of Probation | A | N/A | F | F | A |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | A | F | F | A | F |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | A | F | F | A | A |

| Police Department | B | A | F | F | A |

| Commission on Human Rights | C | N/A | F | B | A |

| Department of Consumer and Worker Protection | C | N/A | F | A | A |

| Department of Environmental Protection | C | C | C | F | A |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | C | A | D | F | A |

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | C | A | C | F | A |

| Department of Small Business Services | C | F | F | A | F |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | C | N/A | F | F | A |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | D | A | F | F | F |

| Department of Correction | D | D | F | F | A |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | D | N/A | D | F | A |

| Department of Transportation | D | B | F | F | A |

| Fire Department | D | B | F | D | A |

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | D | N/A | F | F | A |

| Business Integrity Commission | F | N/A | F | F | F |

| Department of City Planning | F | F | F | A | A |

| Department of Finance | F | F | F | F | B |

| Department of Homeless Services | F | C | D | F | A |

| Department of Sanitation | F | D | F | F | C |

| Human Resources Administration | F | F | F | F | B |

| Law Department | F | N/A | F | F | D |

| NYC Emergency Management | F | F | F | F | A |

Table 5: Agency Grades with Women by Industry

| Agency Name | Women | Construction | Professional | Standard | Goods |

| Citywide | D | D | C | C | C |

| Office of the Comptroller | A | N/A | A | A | D |

| Business Integrity Commission | A | N/A | F | A | A |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | A | N/A | A | B | A |

| Commission on Human Rights | A | N/A | B | A | F |

| Department for the Aging | A | A | A | A | B |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | A | F | A | A | A |

| Department of Small Business Services | A | F | A | A | F |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | A | N/A | F | A | A |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | A | A | A | A | A |

| Police Department | A | A | F | A | B |

| Department of City Planning | B | F | C | A | A |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | B | A | D | A | D |

| Department of Correction | B | F | F | A | B |

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | B | A | C | F | D |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | B | N/A | F | A | B |

| Human Resources Administration | B | F | A | D | D |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | B | F | A | C | B |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | C | C | B | C | A |

| Law Department | C | N/A | D | A | D |

| Administration for Children’s Services | D | F | B | F | A |

| Department of Design and Construction | D | F | C | C | A |

| Department of Environmental Protection | D | D | B | D | A |

| Department of Probation | D | N/A | F | F | C |

| Fire Department | D | D | D | F | A |

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | D | N/A | C | D | C |

| Department of Buildings | F | F | F | D | A |

| Department of Consumer and Worker Protection | F | N/A | F | D | B |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | F | F | F | A | A |

| Department of Finance | F | F | F | F | A |

| Department of Homeless Services | F | F | A | F | A |

| Department of Sanitation | F | F | F | F | C |

| Department of Transportation | F | D | F | F | A |

| NYC Emergency Management | F | F | F | B | D |

Grading by Minority Group: More than Half of Agencies are Failing with African American-Owned M/WBEs

For their spending with African American-owned firms, five agencies received “A” grades, one agency received a “B” grade, one received a “C” grade, eight received “D” grades, and 17 received “F” grades.

With Hispanic American-owned firms, ten agencies received “A” grades, one agency received a “B” grade, seven received “C” grades, six received “D” grades, and eight received “F” grades.

With women-owned firms, nine agencies received “A” grades, seven agencies received “B” grades, two received “C” grades, six received “D” grades, and eight received “F” grades.

With Asian American-owned firms, 21 agencies received “A” grades, two agencies received “B” grades, two received “C” grades, four received “D” grades, and three received “F” grades. Tables 2 through 5 provide assigned grades for agencies by minority group and industry.

Additional information about individual agency grades is available in Appendix A. The worksheets used to calculate each agency grade appear in Appendix B and a complete explanation of the report’s methodology can be found in Appendix D. Subcontract data for each agency can be found in Appendix C. A review of the City’s top vendors and their M/WBE utilization appears in Appendix E, showing that M/WBEs received about 11 percent of the $4.1 billion that went to the City’s top 50 vendors.

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impact on M/WBEs

COVID-19 has raged through New York City, killing more than 23,800 people and sickening more than a quarter of a million city residents. At the outset of the pandemic, the city’s economy was all but locked down and has since re-opened only partially in an effort to stop the spread and protect lives, resulting in mass layoffs and lost income for hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers, and a dramatic drop in tax revenues. The pandemic disproportionately impacted M/WBEs, who already face structural inequalities resulting from a long history of discrimination. For instance, M/WBEs are less likely to gain financing and develop relationships with banks due to institutional racism. Because of this, when banks were charged with processing applications for federal COVID-19 relief, many MWBEs were automatically excluded.40

As a result, a July 2020 survey from New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer’s Office found that 85 percent of M/WBEs projected less than six months of survival.41 This means that although 30 percent of all small business in New York City may permanently close as a result of the pandemic, firms owned by women and people of color were more vulnerable to closure.42 The same dynamic has also played out on the national stage. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that between February and April 2020, African American business ownership fell by 41 percent, Latino business ownership dropped by 32 percent, Asian American business ownership declined by 26 percent, and women business ownership fell by 25 percent in comparison to white-owned business which decreased by 17 percent.43

Women and people of color face long term ramifications beyond losing their businesses, leading to job losses and destabilization of their communities. For example, in New York City, COVID- 19 has so far disrupted 50 percent of jobs held by Hispanic Americans and 40 percent of jobs held by African Americans and Asian Americans respectively due to layoffs, unpaid leave, lower wages, and fewer hours of work.44

The City and State announced several initiatives impacting M/WBEs’ ability to stay open and compete for City contracts during such an unprecedented time. These steps are described below:

New York City and State Actions Impacting M/WBEs During COVID-19

March 2020 — Suspending Procurement Policy Board Rules

The Mayor issued an emergency executive order suspending several sections of City law, including the Procurement Policy Board Rules and Local Law 1, the City’s M/WBE Law, for contracts associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. The City also began self-registering contracts rather than going through the normal registration process through the Comptroller’s Office.[45] In August 2020, Comptroller Stringer sent a letter to the Mayor calling on the City to reinstate the Comptroller’s Office’s Charter-mandated role to approve and register contracts, which would restore checks and balances in the procurement process.[46]

April – May 2020 – Fair Recovery Taskforce and Sector Advisory Councils

The City announced the creation of a Fair Recovery Taskforce to guide the City’s recovery and reopening post-COVID, including a Racial Equity Taskforce to focus on the recovery of M/WBEs. Members of the Sector Advisory Councils include representatives from large businesses; small businesses; public health and healthcare; foundations; and the non-profit sector. Since its creation, the taskforce has launched a restaurant payroll assistance program and a partnership with M/WBEs to expand internet access in low-income communities of color. The City also on calling for a Charter Revision Commission to discuss Fair Recovery, which, as of October 2020, has not yet convened.[47]

April – June 2020 – City Relief for Businesses Impacted by COVID-19 and Storefront Damage from Protests

The City announced four assistance programs for businesses facing economic hardship in the face of COVID-19 and looting. The assistance programs included a grant and loan program for businesses to retain employees and ensure business continuity during stay-at-home orders; a program to provide restaurants with funding for displaced restaurant workers to prepare meals for their communities; and emergency grants for storefronts in the Bronx impacted by looting, which included a set aside for M/WBEs and small businesses. The City also announced a Small Business Hotline and online resources to help businesses navigate the recovery and re-opening process.[48]

May 2020 – State Relief for Businesses Impacted by COVID-19

The State announced $100 million New York Forward Loan Fund to provide loans to help small businesses, focusing on minority- and women-owned small businesses that did not receive federal COVID-19 assistance through the Paycheck Protection Program or the Economic Injury Disaster Loan Program, as they reopened after the COVID-19 outbreak and NYS on PAUSE. The State set geographical goals, targeting a 30 percent goal for New York City-based businesses.[49]

Legislative Updates Impacting M/WBEs During COVID-19

The New York City Council recently passed the following legislation impacting small businesses and M/WBEs affected by COVID-19:

May 2020 – COVID-19 Relief Package

Int. Nos. 1932-2020, 1914-2020, 1908-2020, 1898-2020, 1940-A-2020, 1916-A-2020, 1936-A-2020

The City passed legislation that provided relief for tenants, commercial establishments, restaurants, and struggling small businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Business owners were temporarily relieved from being personally liable for their commercial rent and the City established fines for landlords that harass their COVID-19- impacted tenants. Also, the legislation provided relief to restaurants by imposing limits on third-party food delivery fees and extending the suspension of fees for sidewalk cafes. It also gave small businesses additional time to complete and process renewals for licenses and permits from City agencies.[50]

June 2020 – Tracking COVID-19-related spending

Int. No. 1952-A-2020

The New York City Council passed a bill requiring the City to create a database to track COVID- 19 City spending of federal, state, or local funds through expense and capital expenditures, procurement contracts, grants, and loans. The bill requires the database to include the M/WBE status of all contract recipients. The law took effect in late October 2020.51

Utilization of M/WBEs in COVID-19-Related Contracts: M/WBEs Have Received Just 11 Percent of COVID-19 Spending

M/WBEs stood ready to help the City of New York respond to COVID-19. Comptroller Stringer’s July 2020 survey found that 65 percent of M/WBEs expressed being ready, willing, and able to provide COVID-19 related goods and services. In addition, a search of the City’s M/WBE directory yields more than 60 M/WBEs able to provide PPE or medical equipment, more than 140 caterers and food vendors, over 20 medical staffing companies, and more than 140 building security companies.[52]

However, despite their availability, M/WBEs have experienced barriers accessing opportunities. Of the 500 M/WBEs surveyed, only 62 M/WBEs actually competed for a contract, and only 10 M/WBEs received a contract. At the same time, the City canceled or failed to fulfill tens of millions worth of contracts with vendors that lacked capacity or relevant experience.[53] Comptroller Stringer’s Office follows up on the survey through this report, finding that the City’s cancellation of Procurement Policy Rules ultimately led to low M/WBE utilization during the pandemic.

Between March and August 2020, the City spent over $1.5 billion in COVID-19-related goods and services contracts, and just 11 percent, or $168.5 million, went to M/WBEs, as seen in Chart 6.[54] In May 2020, the Department of Small Business Services (SBS) testified that the City awarded COVID-19 related contracts to more than 200 M/WBE vendors totaling over $200 million.[55] However, just 86 M/WBEs actually received COVID-19-related payments by August 2020. The City spent about $92.3 million, or about six percent, with women-owned businesses; $43 million, or three percent with Asian American-owned businesses; about $17.5 million, or one percent with Black American-owned firms; and about $15.7 million, or one percent, with Hispanic American-owned firms.

As seen in Table 6, three agencies made up more than 80 percent of the City’s COVID-19 related spending and had limited spending with M/WBEs. The Department of Citywide Administrative Services spent over $613 million primarily for personal protective equipment (PPE) such as face masks and disposable gowns, medical equipment such as thermometers, and hand sanitizer. Just $54.8 million, or nine percent, went to M/WBEs. The Department of Sanitation spent more than $473 million, mostly for emergency food for New Yorkers. M/WBEs only received about $64 million, or about 14 percent, of these contract dollars. NYC Emergency Management spent more than $181 million for medical staffing, the City’s isolation hotel program, and security. M/WBEs received a mere $2.4 million, or one percent, of these dollars. In addition, three entities spent $0 with M/WBEs for COVID-19 related expenses: Health and Hospitals Corporation, the Mayoralty, and the Department of Parks and Recreation. COVID-19 spending spanned both mayoral and non-mayoral agencies including Health and Hospitals and Department of Education; their spending is included in this analysis.

However, nine agencies spent more than 30 percent of their COVID-19 related expenses with M/WBEs: the Department of Correction, Department of Environmental Protection, Department of Transportation, and Law Department each 100 percent of their COVID spending with M/WBEs; Administration for Children’s Services spent 83 percent; Department of Youth and Community Development spent 76 percent; Department of Education spent 67 percent; Department of Health and Mental Hygiene spent 62 percent; and the Police Department spent 59 percent. Unfortunately, these nine agencies’ combined spending only comprises four percent of the City’s total COVID-19-related procurement dollars. As the City continues to recover from the pandemic it must expand its efforts to engage M/WBEs. They must be a part of the solution in order to survive.

Chart 6: M/WBE Share of COVID-19 Related Spending, March-August 2020

Source: Checkbook NYC.

Table 6: Agency COVID-19-related Spending and M/WBE Share, March-August 2020

| Agency | M/WBE Spending | Total Spending | MWBE % |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | $54,782,287 | $613,887,589 | 8.92% |

| Department of Sanitation | $63,998,925 | $ 473,035,874 | 13.53% |

| NYC Emergency Management | $2,430,601 | $ 181,427,497 | 1.34% |

| Department of Homeless Services | $369,260 | $ 79,137,548 | 0.47% |

| Department of Social Services | $1,124,871 | $50,314,404 | 2.24% |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | $29,851,176 | $47,879,003 | 62.35% |

| Department of Design and Construction | $859,189 | $24,015,293 | 3.58% |

| Police Department | $8,214,315 | $ 13,994,620 | 58.70% |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | $3,004,351 | $ 10,953,477 | 27.43% |

| Fire Department | $840,272 | $ 9,269,621 | 9.06% |

| Department for the Aging | $2,057,293 | $ 8,219,362 | 25.03% |

| Health and Hospitals Corporation | $0 | $4,831,066 | 0.00% |

| Mayoralty | $0 | $1,150,540 | 0.00% |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | $0 | $632,519 | 0.00% |

| Department of Correction | $405,026 | $405,026 | 100.00% |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | $160,399 | $211,209 | 75.94% |

| Department of Environmental Protection | $178,262 | $178,262 | 100.00% |

| Administration for Children’s Services | $126,193 | $151,693 | 83.19% |

| Financial Information Services Agency | $0 | $81,924 | 0.00% |

| Department of Transportation | $74,340 | $74,340 | 100.00% |

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | $10,864 | $51,709 | 21.01% |

| Law Department | $47,250 | $47,250 | 100.00% |

| Department of Education | $12,600 | $18,800 | 67.02% |

| New York Citywide | $168,547,474 | $1,519,968,626 | 11.09% |

The Department of Education’s Missed Opportunity to Do with M/WBEs

This year, for the first time, the Comptroller Stringer’s Office analyzes New York City Department of Education (DOE) spending and its impact on M/WBEs. DOE is not subject to Local Law 1 or the City’s procurement rules and does not receive a grade in this report. However, given the sheer volume of the DOE’s spending and its inclusion in the City’s goal to award $25 billion to M/WBEs by 2025, transparency is key to the process of enhancing M/WBE opportunities within New York City’s education system. The Department of Education spends more than $4 billion annually, more than any agency graded in this report. In fact, DOE spending is comparable in size to Delaware’s state budget.[56]

Over the last four years, DOE spending with M/WBEs has almost doubled, from $117.9 million to $232.3 million, as seen in Chart 7. However, its M/WBE utilization is insignificant when compared with its total procurement budget. In FY 2020, of the DOE’s $4.3 billion in spending, less than six percent, or $232.3 million, went to M/WBEs.

More specifically, as seen in Chart 8, Asian American-owned businesses received $101 million or 2.4 percent of spending; women-owned firms received about $92.4 million, or 2.2 two percent of spending; Black American-owned businesses $26.3 million or just 0.6 percent of spending; and Hispanic American-owned firms received $12.5 million, or less than 0.3 percent of spending.

In FY 2020, the DOE’s $4.3 billion in spending went to more than 8,000 firms. However, the top 50 recipients of DOE procurement dollars—all non-M/WBEs —received $1.8 billion, or about 42 percent of all DOE spending. Table 7 shows that 22 of the DOE’s top vendors were school bus companies, receiving a total of $960 million; four food . But this is not because of a lack of M/WBE availability. A search of the City’s M/WBE directory yields M/WBEs in every DOE top procurement category. In particular, there were more than 20 bus companies, more than This represents a missed opportunity to do business with M/WBEs. Availability counts were based on M/WBEs’ own business descriptions in the NYC Department of Small Business Services M/WBE Directory. The list of search terms can be found in Appendix F.

Chart 7: M/WBE Share of Department of Education Spending, FY 2017 – FY 2020

Source: Checkbook NYC.

Chart 8: New York City Department of Education Spending with M/WBEs, FY 2020

Source: Checkbook NYC.

Table 7: Missed Opportunities with M/WBEs: Top 50 Department of Education Vendors and M/WBE Availability

| Vendor | M/WBE Status | FY 2020 Spending Received | Industry/Purpose of Contract | Number M/WBEs within Industry/Purpose of Contract |

| RELIANT TRANSPORTATION INC | Non-M/WBE | $96,872,489 | School Bus | 22 |

| LAW OFFICES OF REGINA SKYER & ASSOCIATES LLP | Non-M/WBE | $94,204,184 | Legal Services | 106 |

| BORO TRANSIT INC | Non-M/WBE | $89,806,234 | School Bus | 22 |

| PIONEER TRANSPORTATION CORP | Non-M/WBE | $88,740,330 | School Bus | 22 |

| SDI INC | Non-M/WBE | $75,774,536 | Supply Chain Solutions | 10 |

| METROPOLITAN FOODS INC | Non-M/WBE | $69,601,185 | Food | 144 |

| CDW GOVERNMENT LLC | Non-M/WBE | $67,385,796 | IT/Equipment | 310 |

| WILLIS OF NEW YORK INC | Non-M/WBE | $61,748,080 | Surety Bond | 6 |

| LITTLE RICHIE BUS SERVICE INC | Non-M/WBE | $57,504,272 | School Bus | 22 |

| PRIDE TRANSPORTATION SERVICES INC | Non-M/WBE | $55,098,597 | School Bus | 22 |

| LOGAN BUS CO INC | Non-M/WBE | $52,017,032 | School Bus | 22 |

| HOYT TRANSPORTATION CORP | Non-M/WBE | $51,857,377 | School Bus | 22 |

| TERI NICHOLS INSTITUTIONAL FOOD MERCHANT LLC. | Non-M/WBE | $50,744,263 | Food | 144 |

| LEESEL TRANSPORTATION CORP | Non-M/WBE | $49,265,551 | School Bus | 22 |

| SNT BUS INC. | Non-M/WBE | $48,848,966 | School Bus | 22 |

| L&M BUS CORP | Non-M/WBE | $46,724,970 | School Bus | 22 |

| JOFAZ TRANSPORTATION INC. | Non-M/WBE | $41,598,229 | School Bus | 22 |

| LORINDA ENTERPRISES LTD | Non-M/WBE | $35,690,133 | School Bus | 22 |

| ALL AMERICAN SCHOOL BUS CORP. | Non-M/WBE | $34,579,687 | School Bus | 22 |

| RCM TECHNOLOGIES USA INC | Non-M/WBE | $34,195,660 | IT/Equipment | 310 |

| QUALITY TRANSPORATION CORP. | Non-M/WBE | $31,670,543 | School Bus | 22 |

| CATAPULT LEARNING LLC | Non-M/WBE | $28,463,873 | Educational Services/Materials | 151 |

| GVC LTD | Non-M/WBE | $27,962,630 | School Bus | 22 |

| MAR-CAN TRANSPORTATION COMPANY INC | Non-M/WBE | $27,777,083 | School Bus | 22 |

| VOLMAR CONSTRUCTION INC | Non-M/WBE | $25,534,049 | Construction | 884 |

| GRANDPA’S BUS COMPANY, INC. | Non-M/WBE | $25,355,571 | School Bus | 22 |

| Y & M TRANSIT CORP. | Non-M/WBE | $25,152,358 | School Bus | 22 |

| APPLE INC | Non-M/WBE | $24,803,664 | IT/Equipment | 310 |

| SCHOOL SPECIALTY INC | Non-M/WBE | $23,361,791 | School Furniture | 25 |

| CROWN CASTLE FIBER LLC | Non-M/WBE | $23,307,230 | Telecommunications & Voice/Data Services | 49 |

| LENOVO, INC | Non-M/WBE | $22,188,974 | IT/Equipment | 310 |

| UNITED METRO ENERGY CORP | Non-M/WBE | $22,175,167 | Fuel/Gas | 30 |

| CONSOLIDATED BUS TRANSIT INC | Non-M/WBE | $21,993,009 | School Bus | 22 |

| WILLIS TOWERS WATSON NORTHEAST INC | Non-M/WBE | $21,409,373 | Surety Bond | 6 |

| IC BUS, INC. | Non-M/WBE | $20,831,277 | School Bus | 22 |

| THE MARAMONT CORPORATION | Non-M/WBE | $20,809,509 | Food | 144 |

| T & G INDUSTRIES INC | Non-M/WBE | $20,564,988 | Office Printers | 17 |

| OPERATIVE CAKE CORP. | Non-M/WBE | $20,541,670 | Food | 144 |

| STAPLES CONTRACT & COMMERCIAL LLC | Non-M/WBE | $19,746,923 | Office Supplies | 40 |

| GEOMATRIX SERVICES INC | Non-M/WBE | $19,354,163 | Construction | 884 |

| PEARSON EDUCATION | Non-M/WBE | $18,949,560 | Educational Services/Materials | 151 |

| VANGUARD DIRECT INC | Non-M/WBE | $16,695,723 | Marketing | 486 |

| VAN TRANS, LLC | Non-M/WBE | $16,290,487 | School Bus | 22 |

| PRO CON GROUP INC. | Non-M/WBE | $16,027,588 | Construction | 884 |

| HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT PUBLISHING COMPANY | Non-M/WBE | $15,632,089 | Educational Services/Materials | 151 |

| VERIZON BUSINESS NETWORK SERVICES INC | Non-M/WBE | $15,585,744 | Telecommunications & Voice/Data Services | 49 |

| AMPLIFY EDUCATION INC. | Non-M/WBE | $14,426,631 | Educational Services/Materials | 151 |

| BOBBY’S BUS CO INC | Non-M/WBE | $14,345,384 | School Bus | 22 |

| S & W WILSON ENTERPRISES INC. | Non-M/WBE | $13,841,193 | Architects/Civil Engineers | 491 |

| HORIZON HEALTH CARE STAFFING CORP | Non-M/WBE | $13,698,325 | Medical Staffing | 27 |

M/WBE Small Purchase Method: 96 Percent of M/WBEs Received No Spending; Hispanic American Firms Saw a Decrease of $600,000 in M/WBE Purchases

In July 2019, the New York State Legislature approved a bill allowing New York City agencies to increase their discretionary spending to $500,000 for goods, standard services, and professional services.[57] This new law expanded upon a 2017 effort to increase the micro purchase limit to $150,000 for goods and services contracts.[58] For the first time it also includes construction contracts, which were previously limited to $35,000 for micro purchases. In response to the law, the New York City Procurement Policy Board created new rules outlining the process for City agencies to purchase directly from M/WBEs using this method. The new rule took effect in January 2020.

Overall, the City saw increased usage of M/WBE Small Purchases in FY 2020. Collectively, agencies spent about $63.7 million across 1,171 contracts, compared to $42.4 million across 747 contracts in FY 2019, an increase of about $21.3 million and 424 contracts. Although this is an increase, spending through the M/WBE Purchase Method comprised just one percent of the City’s Local Law 1-eligible spending. At the industry level, about 65 percent of M/WBE Small Purchases were for goods contracts, 23 percent for professional services, ten percent for standard services, and less than one percent for construction.

Unfortunately, the majority of M/WBEs did not benefit substantially from the M/WBE Small Purchase Method. Ninety-six percent of M/WBEs did not receive any spending through this method and only 432 firms received spending through the opportunity. Ten vendors generated more than $1 million in revenue through the M/WBE Small Purchase Method, more than half of which were in the field of technology.

The expansion of the M/WBE Small Purchase Method did not benefit all minority groups. Hispanic Americans saw a decrease in M/WBE Small Purchases, receiving $9.4 million or about $600,000 less than in FY 2019. At the same time, women-owned businesses received $26.8 million, an increase of about $11.8 million since last year. Asian Americans received $17.9 million, about $6.8 million more than in FY 2019. African Americans received $9.6 million, a $3.4 million bump compared with FY 2019.

The Office of the New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer finds that at the agency level, after two years with the M/WBE Small Purchase Method in place and an expansion of the rule, ten agencies spent less than one percent of their budgets using the M/WBE Small Purchase Method in FY 2020: the Department of Environmental Protection, Human Resources Administration, Department of Transportation, Department of Sanitation, Department of Citywide Administrative Services, Department of Parks and Recreation, Department of Homeless Services; NYC Emergency Management, Department of Design and Construction; and the Landmarks Preservation Commission. In addition, despite the expanded M/WBE Small Purchase rule being in place for a full six months, only two agencies, the Comptroller’s Office and the Department of Citywide Administrative Services, had M/WBE Small Purchase contracts exceeding $150,000.

However, there were eight agencies that spent more than ten percent of their FY 2020 budget using the M/WBE Purchase Method, up from six agencies in FY 2019: the Commission on Human Rights, which spent about 40 percent of their budget using the M/WBE Small Purchase Method; the Civilian Complaint Review Board and Department for the Aging each at about 32 percent; Department of Probation at about 21 percent; Department of Cultural Affairs and Department of Small Business Services at about 18 percent; Department of Youth and Community Development each at about 16 percent; and the Taxi and Limousine Commission at about 13 percent. While not a mayoral agency, the Comptroller’s Office is also evaluated. The Comptroller’s Office spent about ten percent of its FY 2020 budget using the M/WBE Small Purchase Method.

Table 8: Agency M/WBE Small Purchase Method Utilization, FY 2019 – 2020

| FY20 | FY19 | |||||

| Agency Name | LL1 Eligible Spending | M/WBE Method Spending | M/WBE Method % | FY19 M/WBE Method % | Change in M/WBE Method % | At least 1 contract exceeding $150,000 in spending |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Citywide | $6,340,477,772 | $63,697,316 | 1.00% | 0.68% | 0.32% | |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | $182,238 | $0 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | x |

| Department of Design and Construction | $1,692,200,380 | $1,550,958 | 0.09% | 0.04% | 0.05% | x |

| Human Resources Administration | $202,283,954 | $1,466,312 | 0.72% | 0.20% | 0.52% | x |

| Department of Sanitation | $538,062,008 | $3,623,375 | 0.67% | 0.31% | 0.36% | x |

| Department of Homeless Services | $112,173,715 | $583,211 | 0.52% | 0.37% | 0.15% | x |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | $617,107,589 | $3,831,589 | 0.62% | 0.42% | 0.20% | ✓ |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | $435,862,031 | $2,458,318 | 0.56% | 0.43% | 0.13% | x |

| Department of Transportation | $722,633,461 | $5,216,210 | 0.72% | 0.47% | 0.25% | x |

| Department of Environmental Protection | $871,361,289 | $7,588,035 | 0.87% | 0.64% | 0.23% | x |

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | $45,028,533 | $1,431,974 | 3.18% | 0.83% | 2.35% | x |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | $266,792,635 | $5,250,440 | 1.97% | 1.32% | 0.65% | x |

| Police Department | $232,778,220 | $4,752,071 | 2.04% | 1.51% | 0.53% | x |

| Law Department | $44,140,550 | $739,475 | 1.68% | 1.58% | 0.10% | x |

| Department of Finance | $53,569,778 | $1,428,598 | 2.67% | 1.67% | 1.00% | x |

| Fire Department | $129,836,394 | $5,987,569 | 4.61% | 1.79% | 2.82% | x |

| Department of City Planning | $9,043,147 | $793,396 | 8.77% | 3.72% | 5.05% | x |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | $4,826,835 | $763,135 | 15.81% | 3.98% | 11.83% | x |

| Administration for Children’s Services | $51,513,196 | $3,843,432 | 7.46% | 4.20% | 3.26% | x |

| Department of Buildings | $28,117,284 | $1,089,112 | 3.87% | 4.52% | -0.65% | x |

| $128,606,195 | $360,248 | 0.28% | 5.30% | -5.02% | x | |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | $68,615,002 | $3,621,435 | 5.28% | 5.79% | -0.51% | x |

| Department of Correction | $58,999,707 | $2,829,962 | 4.80% | 5.82% | -1.02% | x |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | $378,513 | $122,184 | 32.28% | 5.91% | 26.37% | x |

| Department of Small Business Services | $6,754,307 | $1,230,510 | 18.22% | 8.00% | 10.22% | x |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | $3,836,237 | $513,640 | 13.39% | 8.06% | 5.33% | x |

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | $2,837,542 | $277,837 | 9.79% | 8.31% | 1.48% | x |

| Department of Consumer and Worker Protection | $3,772,979 | $263,176 | 6.98% | 12.88% | -5.90% | x |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | $3,973,015 | $726,599 | 18.29% | 13.20% | 5.09% | x |

| Department for the Aging | $1,287,910 | $406,792 | 31.59% | 16.07% | 15.52% | x |

| Department of Probation | $2,673,099 | $548,706 | 20.53% | 16.40% | 4.13% | x |

| Business Integrity Commission | $312,450 | $31,181 | 9.98% | 17.78% | -7.80% | x |

| Commission on Human Rights | $917,579 | $367,835 | 40.09% | 57.74% | -17.65% | x |

| Office of the Comptroller | $14,755,762 | $1,539,675 | 10.43% | 5.10% | 5.33% | ✓ |

Recommendations

Comptroller Stringer’s primary goal of this report is to increase opportunities for women and people of color through City procurement. With that goal in mind, for the third consecutive year, Comptroller Stringer’s Office held a series of focus groups to gather input from more than 40 M/WBEs as well as members of the Comptroller’s Advisory Council on Economic Growth through Diversity and Inclusion.

Based on the data on spending with M/WBEs, feedback from the focus groups, and the Comptroller’s 2020 M/WBE COVID-19 survey data, Comptroller Scott M. Stringer makes the following recommendations:

The City needs to take a more finely tuned approach to M/WBE spending.

The Mayor’s Task Force on Racial Equity and City Hall should develop a targeted plan to address areas where there is low M/WBE utilization even with M/WBE availability: with the Department of Education, COVID-19-related procurement, and the M/WBE Small Purchase Method. In this report, Comptroller Stringer identifies low M/WBE spending by DOE and through the City’s COVID-19 related purchases, as well as a clear underutilization of the M/WBE Small Purchase Method. It is clear that the supply chain in the City of New York needs to be closely examined with an eye toward reform at every step in the process. For example, in order to take full advantage of the M/WBE Small Purchase Method, the City should review the procurements needs of each agency. For every upcoming procurement below $500,000, including new and renewal contracts, the City should identify M/WBE Small Purchase opportunities. If there is M/WBE availability, agencies should prioritize the M/WBE Small Purchase Method over other procurement methods.

The City should establish an initiative to pay M/WBEs and small businesses for their upfront overhead costs.

As women and people of color face uncertain futures and small businesses across the country are closing their doors, the City should implement payment policies that support its vendors’ sustainability. The City’s current practices often exacerbate M/WBEs’ challenges. As Comptroller Stringer has previously stated, M/WBEs report waiting months or even years for payments from City agencies. In fact, a 2019 survey from Comptroller Stringer’s Office revealed that 80 percent of M/WBEs waited more than 30 days to be paid for their first invoice.[59] Given today’s economic climate, the City should no longer burden M/WBEs and small businesses with late payments.

The City has already established policies to pay some vendors for their upfront overhead costs. For example, under certain construction contracts, the City offers mobilization payments of up to four percent of a total contract once the vendor completes ten percent of the work. Mobilization payments cover the costs of significant initial expenses required by contract as well as other mandates imposed by City, State, or federal law such as payment and performance bonds, insurance, office spaces, storage, and sanitary and other facilities.[60] Such mobilization payments benefit both the City and the vendor: the City is able to ensure a safe and compliant facility, leading to fewer issues later in the contract, and the vendor can recover the costs incurred to start the project, allowing it to reinvest in the business or cover future costs of the contract.

The City should make these payments for upfront overhead costs available to more vendors. For instance, within the professional services and standard services industries, M/WBEs and small businesses may benefit from receiving upfront payments for insurance or office space. For goods contracts, vendors may benefit from upfront payments for transporting goods or warehousing costs. The structure of mobilization payments will differ based on the contract payment structure. For instance, for contracts with annual budgets and regular monthly payments, upfront costs may be calculated based on a portion of the monthly payment.

As a matter of course, any new payment policies should mirror current due diligence practices to protect taxpayer dollars. The City should always verify a vendor’s integrity before they award and pay them. It should also set up procedures for smooth upfront payment. For example, the City pays 25 percent advances to nonprofit human service providers based on their annual contract budgets. These upfront payments are made once the vendor has a registered contract, approved budget, and an annual advance request through an online platform called the Health and Human Services (HHS) Accelerator. In addition, agencies should have recoupment or payment withholding policies in place in case of unexpected changes to the contract. For instance, for human services contracts, the Department of Homeless Services/Department of Social Services pays advances in full at the beginning of each fiscal year and recoupment occurs over the course of the final five months of the fiscal year if needed.[61] In another example, for construction contracts with payments based on actual costs for unit prices, if a contract is terminated before 50 percent of the work is complete or if the final contract price is less than 50 percent of the original contract price bid, then future payments can be reduced.[62]