Making the Grade 2021

Executive Summary

The New York City that emerges from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic will necessarily be a very different city: after the loss of over 30,000 of our fellow New Yorkers and months of economic disruption that forced the closure of so many storefronts in our neighborhoods, COVID-19 irreparably altered our way of life.[1] It also exposed longstanding structural inequalities, inspiring New Yorkers to call on the country to Stop Asian Hate and to recognize that Black Lives Matter.[2]

Businesses owned by people of color across the country continue to be disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. For example, Minority/Women-owned Business Enterprises (M/WBEs) have been less likely to gain crucial financing due to institutional racism, leaving many automatically excluded from federal COVID-19 relief. In fact, research by the Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative found that the odds of loan approval from national banks were 60 percent lower for Latino-owned businesses in comparison to white-owned businesses.[3] At the same time, they lost more revenue than majority businesses, with Asian American-owned businesses losing more revenue than any other ethnic group.[4]Although the U.S. continues to reopen, a study from the Small Business Majority found that 35 percent of Black entrepreneurs reported business conditions were worsening as time went on.[5]

In New York specifically, a July 2020 survey from New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer’s Office found that 85 percent of M/WBEs projected less than six months of survival. A follow-up survey released in March 2021 found that 50 percent of M/WBEs were forced to lay off or furlough employees. Although 87 percent of M/WBEs that applied for relief received funding through the federal Paycheck Protection Program, it has not been enough to support businesses in the long term. In fact, at the time of the survey, more than 30 percent of M/WBEs projected being unable to pay rent in the next three months.

As the City continues its recovery from the pandemic, we have a unique opportunity to alleviate the challenges of systemic racism and the COVID-19 pandemic by doing business with businesses owned by women and people of color.

This report, published annually since 2014 by the Office of the New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, evaluates the performance of the City’s M/WBE program and makes recommendations for its improvement. This year’s findings, as compared with the last eight years, are below.

The Future of Chief Diversity Officers in the Public and Private Sectors

For six years, Comptroller Stringer called for a Chief Diversity Officer (CDO) in City Hall and every City agency to serve as executive-level strategists, driving the representation of people of color and women across government. In July 2020, Mayor Bill de Blasio signed an executive order to appoint Chief Diversity Officers in every City agency. Although there is still no CDO with a citywide portfolio in City Hall, Comptroller Stringer finds growing implementation of the role across the public and private sector:

- Thirty-six of the 50 most populous cities across the U.S. have appointed CDOs, and more than half of them report to the Mayor or City Manager.

- Several federal agencies and the Executive Office of the U.S. President have implemented executive-level equity efforts.

- Hiring of CDOs tripled between December 2019 and March 2021 within the S&P 500.

- However, just 14 of the City’s top 50 vendors—which have collectively received over $5 billion from the City of New York—have publicly announced CDOs.

Citywide Utilization of M/WBEs

Comptroller Stringer’s Making the Grade report compares spending with M/WBEs to the City’s goals mandated through legislation. The M/WBE law sets citywide participation goals for certain contracts across construction, professional services, goods, and standard services. They are intended to alleviate inequities identified through constitutionally required disparity studies.

In October 2019, based on the City’s latest disparity study, the New York City Council updated M/WBE goals and introduced new goals for Native Americans across all industries and Asian Americans in professional services. These changes went into effect in April 2020. Because this is the first full fiscal year of the law’s implementation, this is the first year in which report grades are based on updated goals. In addition, grades are based on actual spending in FY 2021, rather than the value of contracts awarded during the fiscal year, because contracts awarded may or may not result in M/WBEs actually receiving payments from the City.

This year’s report includes several major findings:

- The City awarded $30.4 billion in contracts in FY 2021, of which only $1.166 billion (equal to 3.8 percent) were awarded to M/WBEs.

- The City fell to a “C-“ grade in FY 2021 for spending with M/WBEs after two consecutive “C” grades.

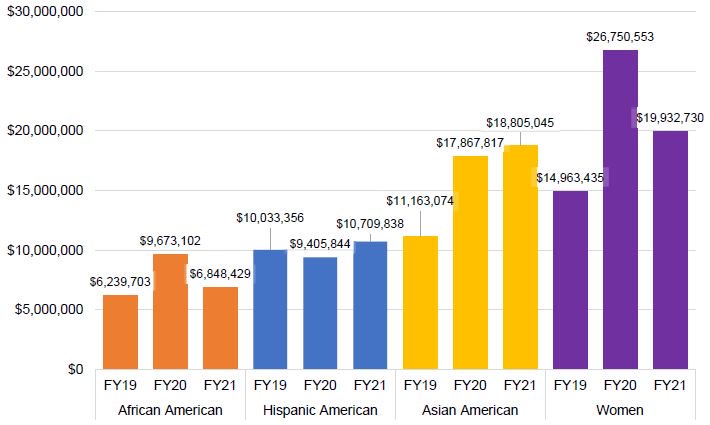

- The City spent $1.27 billion with M/WBEs, an additional $261 million from FY 2020 and an increase of more than $900 million since FY 2014.

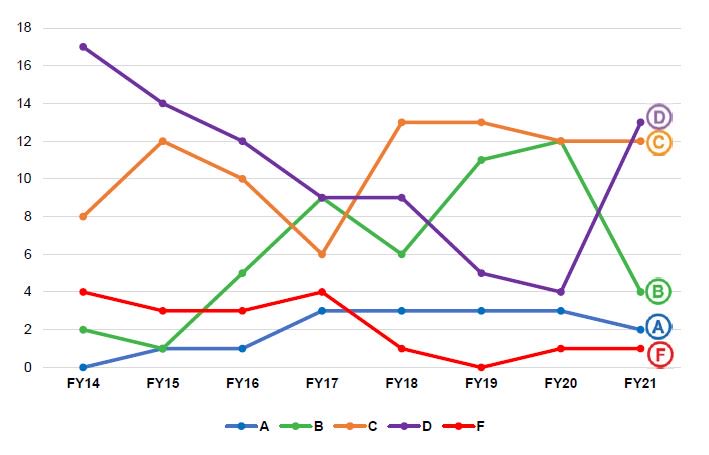

- Since 2014, the City has been able to improve its grades with Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, and women-owned businesses, but it has been unable to improve its “F” grade with African American-owned businesses over the last eight years. In FY 2021, the City earned a “B” grade with Asian American-owned businesses, a “D” with Hispanic American- and women-owned businesses, and an “F” with African American- owned businesses.

- The City has nearly tripled the number of certified M/WBE firms since FY 2015. However, of more than 10,500 certified M/WBEs, 8,886—84 percent—did not receive City spending in FY 2021. The share of certified M/WBEs receiving City dollars has never exceeded 22 percent since FY 2015.

- As of July 2021, New York City only certified four Native American-owned firms and spent $0 with these companies.

- In FY 2021, of the 32 mayoral agencies graded, two received an “A” grade, four received a “B” grade, 12 received a “C,” 13 received a “D,” and one received an “F.” Overall, in FY 2021, three grades improved, 11 grades remained the same, and 18—over half—declined from FY 2020.

- Spending with M/WBEs declined within 18 City agencies from FY 2020 to FY 2021. However, compared with FY 2014, 29 agencies—about 90 percent—increased their spending with M/WBEs in FY 2021.

- Two agencies – the Commission on Human Rights and the Department for the Aging – received their fifth consecutive “A” grades. Both spent more than 50 percent of their Local Law 1-eligible dollars with M/WBEs. By contrast, in FY 2014, no agencies received “A” grades.

- Meanwhile, one agency, the Department of Transportation received an “F” grade in FY 2021, spending just five percent of its Local Law 1-eligible dollars with M/WBEs. By contrast, in FY 2014, four agencies earned “F” grades.

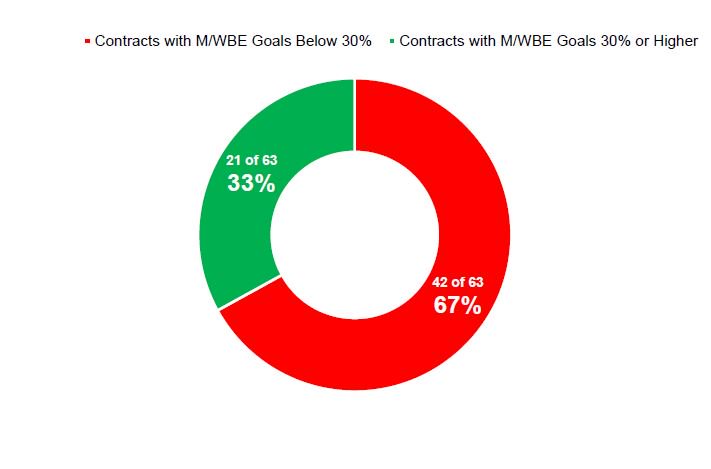

- In 2020, Comptroller Stringer announced that the Office’s registration process would now include a rigorous review of M/WBE goals on City contracts. Between November 2020 and May 2021, the Comptroller’s Office registered 63 contracts subject to Local Law 1. Of these, 42 contracts, or about 67 percent, had M/WBE goals below 30 percent.

- The Comptroller’s Office maintained its third consecutive “A” grade in FY 2021, up from a “C” in FY 2014. The Comptroller’s Office spent approximately 53 percent of its Local Law 1-eligible dollars with M/WBEs this fiscal year, as compared with 13 percent in FY 2014.

Utilization of M/WBEs through the M/WBE Small Purchase Method

In addition to evaluating overall spending with M/WBEs, Comptroller Stringer’s Office analyzes spending through the M/WBE Small Purchase Method annually. The New York State Legislature and New York City Procurement Policy Board approved of this method of doing business with M/WBEs to create more opportunities for women and people of color through discretionary purchases, first up to $150,000 in 2017 and up to $500,000 by January 2020. This report finds that:

- Citywide utilization of the M/WBE Small Purchase Method fell to $56.3 million in FY 2021, a decrease of about $7.4 million from the previous year. M/WBE Small Purchase Method spending represents less than one percent of the City’s M/WBE-eligible spending this fiscal year.

- Ninety-six percent of M/WBEs did not receive any spending through the M/WBE Small Purchase Method. Just 382 firms received M/WBE Small Purchase Method spending, 50 fewer companies than in the previous year.

- Asian American-owned and Hispanic American-owned businesses saw increases in spending through the M/WBE Small Purchase Method, but African American-owned firms saw a $2.8 million decrease and women-owned businesses received about $6.9 million less than in FY 2020.

- Sixteen—or half of—mayoral agencies utilized the M/WBE Small Purchase Method for purchases between $150,000 and $500,000, as compared with just one agency in FY 2020.

- The Comptroller’s Office spent about $1.7 million through the M/WBE Small Purchase Method, about nine percent of the Comptroller’s M/WBE-eligible dollars in FY 2021.

- Between January 2020 and June 2021, agencies submitted only 11 percent of copies of M/WBE Small Purchase contract actions to the Comptroller’s Office for filing purposes and oversight. This means that the Comptroller’s Office has been unable to fulfill its Charter-mandated contract oversight duty of the vast majority of M/WBE Small Purchases. In June 2021, the Comptroller sent a letter to Agency Chief Contracting Officers calling on them to comply with this requirement in order to continue the delegation of self-registration. As of September 2021, more than half of these filing purposes packages remain outstanding.

Utilization of M/WBEs During COVID-19

In addition to Local Law 1 spending, this report reviews spending specifically related to New York City’s COVID-19 response and recovery. In July 2020, Comptroller Stringer’s Office surveyed 500 M/WBEs on the impact of COVID-19, finding that 85 percent of M/WBE firms projected less than six months of survival. A follow-up survey from the Comptroller’s Office found that 50 percent of M/WBEs were forced to lay off or furlough employees. This report examines City spending with M/WBEs, finding that:

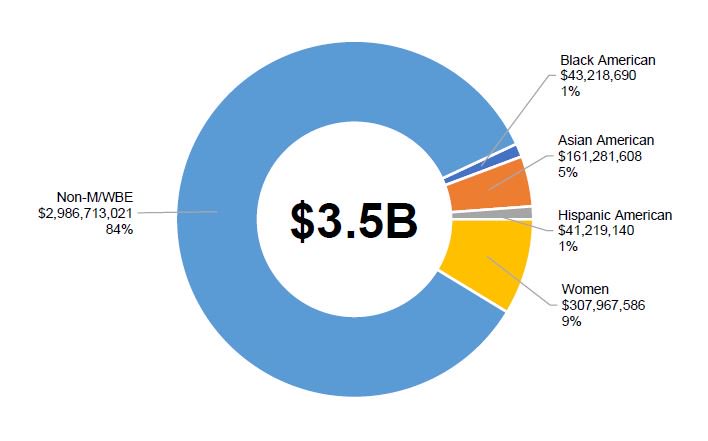

- Between March 2020 and July 2021, the City spent over $3.5 billion in COVID-19-related goods and services, and just 16 percent, or $554 million, went to M/WBEs.

- Specifically, the City spent about $308 million, or about nine percent with women-owned businesses; $161.2 million, or about five percent, with Asian American-owned businesses; $43.2 million, or about one percent, with African American-owned businesses, and $41.2 million, or about one percent, with Hispanic American-owned businesses.

- Two agencies alone made up more than 40 percent of the City’s total pandemic-related dollars. The Department of Citywide Administrative Services spent over $803 million and just ten percent went to M/WBEs. By contrast, the Department of Sanitation spent more than $732 million, and M/WBEs received 25 percent of those dollars.

- Five agencies, both mayoral and non-mayoral, dealt exclusively with non-M/WBEs for their COVID-19-related contracts, including: the Health and Hospitals Corporation, Department of Parks and Recreation, Financial Information Services Agency, Department of Consumer and Worker Protection, and the Department of Small Business Services.

Recommendations

Each year, Comptroller Stringer puts forth recommendations meant to reduce barriers and increase opportunities for M/WBEs. These recommendations are informed by needs identified by the Comptroller’s COVID-19 survey, the City’s M/WBE spending data, a series of focus groups with M/WBEs, and the Comptroller’s Advisory Council on Economic Growth through Diversity and Inclusion. As this administration prepares to leave office, we urge the next cohort of citywide leadership to prioritize diversity, equity, and inclusion within their first 100 days of office.

- Within the first 100 days of office, all incoming Citywide officials should appoint executive-level Chief Diversity Officers. Because each of these offices plays a different role within the City, the CDO would have a unique role to play within each branch of government. For example, the mayoral CDO should oversee the rollout of the City’s programs designed to increase diversity and inclusion within the City, and they should also play a role in the City’s Budget and should have oversight over agency Chief Diversity Officers to ensure a unified citywide inclusion effort. Within the Comptroller’s Office, the CDO should remain at the Deputy Comptroller level. This CDO should continue focusing on holding the City accountable to its diversity goals. In addition, the City Council should consider implementing CDOs, who should conduct racial impact analyses when legislation is considered, where appropriate. Other officials should also consider implementing CDOs, including the Borough Presidents, the Public Advocate, and District Attorneys.

- The next City leaders should adopt the Rooney Rule to ensure that their cabinets are diverse, and that they engage with communities of color, including M/WBEs, to develop their administrations’ goals. The Comptroller’s Office strives for diversity within the top levels of the Office, maintaining a cabinet that is 68 percent people of color and women. The Office has also championed these efforts in the private sector: through its Boardroom Accountability Project, it worked with more than 14 public companies to adopt the Rooney Rule, which requires them to include women and people of color in every future CEO search, as first adopted by the National Football League. In light of the success of this policy, the City should consider adopting the Rooney Rule for every cabinet-level position. This will be especially important in the first 100 days as our city’s new leaders build out their offices, because research finds that companies with racially and culturally diverse executive teams outperform non-diverse teams. In addition, as the Comptroller, Mayor, and City Council build out their leadership teams, they should engage with communities of color, including M/WBEs, to develop their administrations’ goals.

- Within the first 100 days of office, the next Comptroller should conduct a racial equity audit of the City’s agencies. With the signing of President Biden’s Executive Order On Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government, all federal agencies have been mandated to perform an equity assessment to address systemic barriers erected by government which have adversely impacted communities of color.[6] The next Comptroller should mirror this federal effort citywide through an audit of all City agencies. The audit should examine supplier diversity gaps, workforce diversity gaps, pay equity gaps, and agency policies and practices that are systemically biased against communities of color. It should especially focus on the current accountability measures written into law that are not being enforced by agencies or City Hall.

- Within the first 100 days of office, the next Mayor should create a plan to close the gap between certification and receiving City spending for M/WBEs. Over the course of the last eight years, the City has almost tripled its list of certified M/WBEs from just 4,000 to almost 11,000 businesses. However, although we don’t know how many certified M/WBEs competed and were unsuccessful at winning contracts, as this report has shown, no more than 2,000 M/WBEs have ever received City contract dollars in a given year. In fact, in FY 2021, a full 84 percent of M/WBEs did not access City dollars. The City has a responsibility to bridge the gap between M/WBEs and agencies and to translate certification into actual contracting opportunities. The next Mayor should focus on this within their first 100 days by creating a plan to close the gap between the number of people in the program and the number of M/WBEs that win contracts. This plan should hold M/WBE program staff accountable to monitor each M/WBE and work with them to attain at least one contract with the City.

- Within the first 100 days of office, the New York City Council should reassess M/WBE legislation with a targeted focus on goals. One of New York City’s most powerful tools in creating opportunities for M/WBEs is subcontracting. However, this report has shown that almost 70 percent of Local Law 1-eliglble contracts in FY 2021 were assigned goals below the City’s standard of 30 percent. This translated into just 437 M/WBEs receiving subcontracting dollars in FY 2021 – less than five percent of all certified firms. The next City Council should reassess M/WBE legislation with a targeted focus on goals. The Council should review ways that the City can use its full purchasing power to set aggressive M/WBE goals wherever there is M/WBE availability. For example, it should also explore more flexibility when it comes to criteria for granting waivers, including considerations of market availability of M/WBEs and industry standards around subcontracting. In addition, City Council should also utilize the next disparity study to expand the universe of businesses able to participate in the goals program, such as firms with LGBTQIA+ and disabled owners, immigrant-owned firms, and cooperatives.

New York City’s M/WBE Program

The History of the City’s M/WBE Program

New York City has undertaken efforts to boost opportunities for businesses owned by women and people of color since the early 1990s.

In 1992, the City conducted its first disparity study, a formal analysis of the availability and representation of M/WBEs in City contracting. The study found that M/WBEs received a disproportionately small share of City dollars, which led to an executive order creating New York’s first M/WBE program.[7]

In December 2005, City Council commissioned a second disparity study that once again found that qualified M/WBEs were receiving a disproportionately small share of City contracts, leading to the passage of Local Law 129 of 2005 and Local Law 12 of 2006 and the creation of non-binding M/WBE and Emerging Business Enterprise (EBE) goals for New York City mayoral agencies.[8]

City Council significantly amended the M/WBE program through Local Law 1 of 2013, which went into effect in FY 2014. This revision removed a cap that only allowed contracts of up to $1 million to be included in the M/WBE program and allowed agencies to meet participation goals through both prime and subcontracting across four industries: professional services, standard services, goods less than $100,000, and construction.[9]

New York City’s M/WBE program is currently governed by the City Council’s most recent update, Local Laws 174 and 176 of 2019, which added goals for Native Americans across all industries and Asian Americans within professional services contracts. The new law also increases the maximum goods contracts subject to the program from just $100,000 to $1 million, significantly increasing the number of contracts and businesses eligible for participation. In addition to goal changes, the law made administrative changes to the M/WBE program such as more frequent protocol updates and training for City staff. It also requires non-M/WBE prime vendors to identify their intended M/WBE subcontractors in order to hold prime vendors accountable to their subcontracting agreements.[10]

A timeline of New York City’s M/WBE program is reflected in Chart 1, and a review of the City’s updated goals is shown in Chart 2. In addition, throughout this report are direct quotes from M/WBEs from the Comptroller’s May 2020 survey of the impact of COVID-19 on their businesses. Each quote reflects one recommendation from an M/WBE business owner on how the City may improve the outlook for diverse businesses.

Chart 1: Timeline of NYC’s M/WBE Program

2021

The first full year of implementation of new M/WBE goals through Local Law 174. The COVID-19 pandemic continues.

2020

New York City announces certifying more than 10,000 M/WBEs. Mayor de Blasio signs executive order establishing Chief Diversity Officers within every City agency, partly in response to the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color.[21]

2019

NYC reaches goal of certifying 9,000 M/WBEs. Local Law 174 was enacted, adding goals for Native Americans across all industries and Asian Americans in professionals services and increasing eligible goods contracts to $1 million. In addition, voters approve a Charter Revision ballot proposal codifying the M/WBE program into the City Charter.[20]

2018

Third NYC disparity study was commissioned, showing increased availability yet continued underutilization of M/WBEs. Mayor de Blasio increased the City’s goal to award a minimum of $20 billion in City contracts to M/WBEs by 2025.[19]

2016

Mayor de Blasio created the Mayor’s Office of M/WBEs and set goals of certifying 9,000 M/WBEs by 2019 and awarding 30 percent of City contracts to M/WBEs by 2021.[18]

2015

Mayor de Blasio set a goal of awarding a minimum of $16 billion in City contracts to M/WBEs by 2025.[17]

2013

Local Law 1 was enacted, updating M/WBE program goals from 2005 and lifting the $1 million cap on contracts subject to aspirational goals.[16]

2005

Local Law 129 was enacted, re-establishing the M/WBE program with aspirational M/WBE goals on contracts between $5,000 and $1 million.[15]

2004

Second NYC disparity study was commissioned, showing continued underrepresentation of M/WBEs in City contracts.[14]

1994

- Mayor Giuliani eliminated the 10 percent allowance and stating that the process must become “ethnic-, race-, religious-, gender- and sexual orientation neutral.”[13]

- NYC’s first M/WBE program ended.

1992

- First NYC disparity study commissioned, finding that M/WBEs had a disproportionately small share of City contracts.

- Mayor Dinkins created NYC’s first M/WBE program, directing 20 percent of City procurement to be awarded to M/WBEs and allowing the City to award contracts to M/WBEs with bids 10% higher than the lowest bids.[12]

1989

US Supreme Court ruling, City of Richmond vs. J.A. Croson Co., held that in order to establish an M/WBE program, a municipal government needs to show a statistical evidence of a disparity existing between businesses owned by men, women and persons of color.[11]

Chart 2: Local Law 1 Goals vs. Local Law 174 Goals

Recent Progress

Over the course of the last eight years, with the onset of the Making the Grade report, New York City’s M/WBE program has received both legislative and administrative focus. In September 2014, the City announced a goal of awarding $16 billion in contracts to M/WBEs by 2025. Since then, the City increased its goal to $25 billion.[22] The most recent steps taken by the City and State to help achieve these goals are described below:

New York City Administrative Actions Impacting M/WBEs

November 2020-February 2021 – Introducing M/WBE Goals to Affordable Housing and Infrastructure Projects

The City announced a requirement that M/WBE or non-profit developers hold a minimum of 25 percent ownership stake of affordable housing projects. This means that at least 25 percent of the economic benefits of every project, including tax credits, will go to M/WBEs and non-profits. In addition, the City and U.S. Representatives announced that the upcoming construction of John F. Kennedy Airport will require all contractors to ensure 30 percent of their workforce are people of color, and will include a 30 percent M/WBE goal for the project.[23]

November 2020-April 2021 – Funding for Small Businesses and M/WBEs in Hard-Hit Low-to-Moderate-Income (LMI) Communities

The City announced the NYC LMI Storefront loan, Interest Rate Reduction Grant, and Strategic Impact COVID-19 Commercial District Support Grant. These funds aim to provide resources to small businesses that have been heavily impacted by the pandemic, including storefront businesses within low-to-moderate income neighborhoods and businesses with existing loans with Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs). It also announced a grant for non-profits, including local chambers of commerce to provide support services to businesses within low-to-moderate-income neighborhoods and communities of color.

In addition, the City announced that it will allocate over $155 million to small businesses in its FY 2022 budget, including low-interest loans of up to $100,000 to businesses in neighborhoods identified by the City’s Taskforce on Racial Inclusion and Equity as the hardest hit by COVID-19, grants for rent and unpaid expenses during the pandemic, and free legal services to address commercial lease issues. The City also announced that it will establish a small business recovery “one stop shop” service to help businesses meet opening and re-opening requirements. [24]

December 2020 – Resources to Support Employee Ownership

The City announced the launch of Employee Ownership NYC to assist business owners considering transitioning partial or full ownership of the business to an employee. The City aims to target M/WBEs and businesses within communities of color in order to keep jobs and ownership within these communities.[25]

January 2021-June 2021– Mentoring Programs for Underrepresented Entrepreneurs

The City announced three new mentorship programs targeting aspiring entrepreneurs from underrepresented communities, including small storefront business owners pivoting online, Black-owned businesses that are pre-startup and newly formed, and M/WBEs navigating government contracting.[26] In addition, the City announced the Young Men’s Initiative, which will help target Black and Latinx-owned M/WBEs, and will require the City to publish a disparity report every five years on the obstacles that Black and Latinx youth experience across education, employment, and other areas.[27] Along the same lines, the City and its Taskforce on Racial Inclusion and Equity put forth a youth-focused economic justice plan to help build generational wealth among people of color. The plan includes providing access to universal baby bonds, over 2,800 CUNY scholarships for Black and low-income students, and paid internships through the Brooklyn Recovery Corps.[28]

“There has been little to no help. We received 15k for our PPP loan and were super underfunded on it. Why isn’t the city going at banks for that? We know you didn’t set the program up, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t speak out again[st] what is wrong and what is right.”

– An Asian American Women-Owned construction firm in the Bronx

January 2021-April 2021– Resources to Help Small Business Owners Apply for Federal Relief

The City announced its Fair Share NYC campaign which aims to assist small businesses and M/WBEs, especially those that did not receive funding through the first round of the federal Paycheck Protection Program, to access the second round of PPP relief funds. This is important because a study found that more than 90 percent of businesses owned by Black, Hispanic, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander people and 75 percent of businesses owned by Asian Americans could not access this first round of PPP funds.[29] Congress approved these funds through the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2021. In addition, the City announced assistance for restaurants applying for the federal Restaurant Revitalization Fund.[30]

February-August 2021 – Resources for Black-Owned and Women-Owned Businesses

The City announced two programs for Black-owned businesses. Shop Your City: BE NYC is a targeted campaign designed to encourage New Yorkers to buy from local Black-owned businesses. Be NYC Access: Consulting is designed to provide Black-owned businesses with pro bono consulting on financial management and accessing capital from Ernst and Young. The City also announced that its program for women entrepreneurs, WE NYC, has reached 17,000 businesses, 60 percent of which were owned by women of color.[31]

May 2021– Calling on the State to Expand M/WBE Opportunities

The City administration and State legislature announced two bills aimed at expanding opportunities for M/WBEs. Specifically, the M/WBE Expansion Act aims to: increase City agencies’ discretionary threshold with M/WBEs from $500,000 to $1 million; reduce the overhead cost for subcontractors and the City by authorizing the consolidation of insurance on construction contracts; and allow bidders for City contracts who have workforce diversity policies and practices to receive extra points on bids. In addition, the City administration and State Legislature announced the introduction of the Community Hiring Act which aims to create job opportunities for NYCHA residents, veterans, people with disabilities, justice-involved individuals, cash assistance recipients, immigrants, NYCDOE and CUNY Graduates, many of whom are people of color.[32]

New York State Administrative Actions Impacting M/WBEs

April 2021 – Resources for M/WBEs Seeking DASNY Contracts

New York State announced the Fast Track to Surety Program, a training program to help prepare M/WBEs and Serviced Disabled, Veterans Owned Businesses (SDVOBs), to bid as prime vendors for projects $500,000 or greater, and to obtain needed bonding. The program also aims to help M/WBE and SDVOB contractors access Dormitory Authority of the State of New York (DASNY) contracts.[33]

May 2021 – Small Business COVID-19 Relief Grants

New York State announced its plan to provide $800 million in grants of up to $50,000 to small businesses facing financial hardship as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. These grants would be used to cover: operation expenses, payroll, rent or mortgage payments, taxes, utilities, personal protective equipment (PPE), or other business expenses incurred during the pandemic. The State announced that over 330,000 small and micro businesses, including 57 percent of the State’s certified M/WBEs, were eligible for this program.[34]

“[We need] Micro grants to help offset expenses related to switching to virtual business – computers, Zoom software etc[.] – retroactive reimbursement like PPP for the past year.”

– A Hispanic American Woman-Owned Professional Services company in Staten Island

June 2021 – Expanding Jobs in Queens through the LaGuardia Airport

New York State announced the extension of a career center in Queens to help Queens residents, including women and people of color, find jobs at LaGuardia Airport. The State also announced that it met its 30 percent goal for rebuilding LaGuardia Airport, exceeding $1.8 billion in contracts with M/WBEs.[35]

August 2021 – Increasing M/WBE Discretionary Purchases at the Port Authority

The Port Authority Board of Commissioners voted to amend its policy increasing the threshold for direct solicitation of M/WBEs for discretionary contracts. This means that for construction contracts up to $2.5 million and for goods and services contracts up to $1.5 million, the Port Authority can directly solicit certified M/WBEs without a formal competition.[36]

City Council Legislative Actions Impacting M/WBEs

December 2020-January 2021 – Preventing Discrimination in the Workforce (Int. No. 1693 and Int. No. 1314)

The New York City Council passed legislation, enacted in December 2020 and January 2021 respectively, to expand protections from discrimination in hiring, for older adults and people with previous arrests and pending criminal proceedings.[37]

May 2021 – Expanding Opportunities for M/WBE Asset Managers and Financial Services Firms (Int. No. 0901)

New York City Council passed legislation mandating all private sector employers to create retirement savings accounts for their employees. The bill also established a retirement savings board to oversee the City’s program and requires the board to create a plan to include M/WBE asset managers, financial institutions, and professional service firms in the implementation of the program.[38]

June 2021 – Requiring Racial and Equity Reports on Housing (Int. No. 1572)

New York City Council passed legislation introduced by the Public Advocate to require the development of a citywide equitable development tool, which would be used to study and assess the potential racial and ethnic impact of most proposed rezonings. The new law also requires land use applications to include racial equity reports, including how proposed projects relate to the goal of furthering fair housing and equitable access to opportunity.[39]

State Legislative Actions Impacting M/WBEs

January 2021 – New York State Denounces Symbols of Hate (A962/S883)

The New York State legislature passed and the governor signed legislation that denounces and prohibits the attaching or affixing of hate symbols on any state owned property or the grounds of state fair. This bill also prohibits the selling or display of items with hate symbols.[40]

March 2021 – Creating M/WBE Goals Through Adult Cannabis Licenses (S854-A/A1248-A)

The New York State legislature passed a bill legalizing the adult use of cannabis. The bill requires the State to establish a social and economic equity plan which will target individuals who have been disproportionally impacted by cannabis enforcement including creating a goal which will allot 50 percent of licenses to equity applicants including M/WBEs, distressed farmers, and service-disabled veterans.[41]

“[We need] help with accessing the funding sources available to small businesses”

– An Asian American-Owned Professional Services business in Brooklyn

Federal Focus on Diversity and Inclusion

The nation saw renewed focus on diversity and inclusion with the election of President Joseph Biden. Below are the steps the new Administration has taken since President Biden was sworn in on January 20, 2021:

January 2021 – Identifying and Addressing Systemic Bias in Federal Agencies (EO 13985)

The Biden Administration announced an Executive Order which required a 200-day equity assessment across federal agencies in order to identify and address systemic biases and barriers erected by government which adversely impact underserviced communities when seeking access to federal procurement and contracting opportunities. President Biden appointed Susan Rice, Director of Domestic Policy, to spearhead the initiative and to work to ensure federal agencies are working towards diversity, equity and inclusion.[42]

January 2021 – Combating Discrimination Based on Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation within Government (EO 13988)

The Biden Administration announced an Executive Order to create programs, regulations, and fully enforce Title VII and laws that address discrimination in order to combat systemic biases and discrimination based on sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation within government.[43]

January-May 2021– Addressing Racism, Xenophobia, and Intolerance Against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) in the United States (EO 14031)

The Biden Administration announced a Memorandum calling on agencies to address the rising levels of violence and discrimination the AAPI community has received because of derogatory language and depiction of AAPI community during the Covid-19 pandemic.[44] In addition, the Administration announced an Executive Order to establish the President’s Advisory Commission on Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders under the Department of Health and Human Services. The Commission will work to provide recommendations to the President to address xenophobia and barriers the AANHPI community may face and to expand opportunities for the AANHPI community.[45]

January 2021– Strengthening Relationships with Indigenous Tribal Nations

The Biden Administration has announced the prioritization of its relationship with Native American and Alaska Native Tribal nations as it seeks to assess federal agencies, policies, and regulation that effect tribal nations, while ensuring that tribal voices are being heard when federal government deliberate on policies that impact tribal nations.[46]

March 2021– Reinstating Diversity and Bias Trainings across Federal Government

The Biden Administration has announced the revocation of the previous administration’s Executive Order 13950, which prohibited federal agencies and contractors from engaging in diversity and bias trainings. This memo aims to ensure that federal agencies are working towards diversity, equity, and inclusion.[47]

March 2021 – Creating an Executive Gender Policy Council (EO 14020)

The Biden Administration announced an Executive Order to establish the White House Gender Policy Council within the Executive Office of the President. The Council will work to address systemic barriers, biases, and discrimination across the federal government in order to empower women, increase economic security of women, and close the equity gap that divides men and women.[48]

June 2021 – Building Black Wealth and Narrowing the Racial Wealth Gap

The Biden administration announced a plan to address economic disparities within the Black community by creating access to homeownership and small business ownership. The administration will use its federal procurement powers to increase contracts awarded to MWBEs by 50 percent, driving $100 billion for small, disadvantaged businesses within the next five years. The plan will also allocate over $61 billion in the form of grants and programs to help create jobs and build wealth within communities of color.[49]

June 2021 – Mandating a Government-Wide Strategic Plan for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility within the Federal Workforce

The Biden Administration has mandated through Executive Order that the Federal government establish a coordinated government-wide, data-driven strategic plan to promote diversity, inclusion, equity, and accessibility within the federal workforce. In particular, the Executive Order requires the federal government to issue guidance related to promoting paid internships, recruitment, professional development and advancement, training, advancing equity for employees with disabilities and LGBTQ+ employees, pay equity, and expanding opportunities for formerly incarcerated individuals. The Executive Order also requires agencies to seek opportunities to hire Chief Diversity Officers.[50]

September 2021 – Increasing Equity within Historically Black Colleges and Universities

The Biden Administration announced an Executive Order which establishes the Propelling Agency Relationships Towards a New Era of Results for Students Act (PARTNER ACT). The order mandates the Executive Office of the President to implement a government-wide strategic plan to identify and address systemic barriers erected by government agencies that adversely impact Historically Black Colleges and Universities.[51]

September 2021 – Increasing Educational Equity and Opportunity for Hispanic Americans

The Biden Administration put forth an Executive Order establishing a White House Initiative and a Presidential Advisory Commission on Advancing Equity, Excellence, and Economic Opportunity for Hispanic Americans. The White House Initiative and the Presidential Advisory Commission will be charged with addressing systemic barriers to educational equity for Hispanic Americans from early childhood education through higher education and employment.[52]

“We are struggling because the banks are not willing to give us any loans and the loans [through] the [SBA] and others are not enough…”

– A Black-Owned Construction Company in The Bronx

The Future of Chief Diversity Officers in the Public and Private Sectors

In 2014, Comptroller Stringer became the first citywide elected official in New York City to appoint a Chief Diversity Officer. The Comptroller’s Chief Diversity Officer is an executive-level diversity and inclusion strategist who focuses on driving the representation of women and people of color across government through the agency’s Charter-mandated duties, such as registering City contracts, conducting performance and financial audits of all City agencies, and acting as the custodian of the New York City Public Pension Funds. Over the past eight years, the Comptroller’s Office has instituted initiatives to expand opportunities for all, which has resulted in:

- Increased spending within the Comptroller’s Office from 13 percent or $2.4 million to 53 percent, or $8.3 million;

- 77 more women and people of color on corporate boards and 14 companies adopting Rooney Rule policies, which require them to consider women and people of color for board and chief executive officer searches, through the Boardroom Accountability Project;

- $1 billion in pension dollars invested annually in minority investment firms;

- Mandated unconscious bias trainings for all Comptroller employees;

- Requesting diversity growth plans from companies that work with the Comptroller’s Office; and

- The inclusion of LGBTQ-owned businesses in the City’s M/WBE and EBE certification fast-track program.

Comptroller Stringer also championed the call for a Chief Diversity Officer in City Hall and within every City agency since 2014. In 2019, Comptroller Stringer’s Office called for a proposal through the City’s Charter Revision Commission to appoint a Chief Diversity Officer who would report directly to the Mayor. Ultimately, the Charter Revision Commission amended the proposal to codify the current Citywide M/WBE Director in the Charter. New Yorkers approved the amended proposal on the ballot in November 2019. This means that all future mayoral administrations will be required to appoint an M/WBE Director to ensure procurement opportunities for women and people of color.

In July 2020, after years of coordinated pressure as well as the urgent need for executive-level focus on diversity and inclusion shown by the Black Lives Matter movement and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on marginalized communities, Mayor Bill de Blasio signed an executive order to appoint Chief Diversity Officers in every City agency. This was implemented in August 2020 with a list of agency Chief Diversity Officers on the City’s website.[53] However, there is still no Chief Diversity Officer with a citywide portfolio within City Hall.

Mayors across the nation have been implementing Chief Diversity Officers as early as the 1960s. As shown in Table 1, 36 of the 50 most populous cities currently have citywide Chief Diversity Officers, and two additional cities were in the process of hiring CDOs as of July 2021. Twenty-one – more than half – of these CDOs report directly to the Mayor or City Manager, enabling them to more directly influence their cities’ policies, programs, and budgets. And although the majority were in place before the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, six of these positions were created in response to recent calls to address systemic racism in government.

Table 1: Chief Diversity Officers within the 50 Most Populous U.S. Cities*

| City | Population | CDO | Reporting to Mayor | Hired in 2020 |

| New York, New York | 8,336,817 | No | ||

| Los Angeles, California | 3,979,576 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chicago, Illinois | 2,693,976 | Yes | Yes | No |

| Houston, Texas | 2,320,268 | Yes | Yes | No |

| Phoenix, Arizona | 1,680,992 | No | ||

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | 1,584,064 | Yes | Yes | No |

| San Antonio, Texas | 1,547,253 | Yes | No | No |

| San Diego, California | 1423851 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dallas, Texas | 1,343,573 | Yes | No | No |

| San Jose, California | 1,021,795 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Austin, Texas | 978,908 | Yes | No | No |

| Jacksonville, Florida | 911,507 | No | ||

| Fort Worth, Texas | 909,585 | Yes | No | No |

| Columbus, Ohio | 898,553 | Yes | Yes | No |

| Charlotte, North Carolina | 885,708 | Yes | No | No |

| San Francisco, California | 881,549 | Yes | No | No |

| Indianapolis, Indiana | 876,384 | No | ||

| Seattle, Washington | 753,675 | No | ||

| Denver, Colorado | 727,211 | Yes | Yes | No |

| Washington, District of Columbia | 705,749 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Boston, Massachusetts | 692,600 | Yes | Yes | No |

| El Paso, Texas | 681,728 | No | ||

| Nashville, Tennessee | 670,820 | Yes | Yes | No |

| Detroit, Michigan | 670,031 | Yes | No | No |

| Oklahoma City, Oklahoma | 655,057 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Portland, Oregon | 654,741 | Yes | Yes | No |

| Las Vegas, Nevada | 651,319 | No | ||

| Memphis, Tennessee | 651,073 | No | ||

| Louisville, Kentucky | 617,638 | Yes | No | No |

| Baltimore, Maryland | 593,490 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Milwaukee, Wisconsin | 590,157 | Yes | No | No |

| Albuquerque, New Mexico | 560,513 | Yes | No | No |

| Tucson, Arizona | 548,073 | Yes, pending** | Yes | Yes |

| Fresno, California | 531,576 | No | ||

| Mesa, Arizona | 518,012 | Yes | Yes (City Manager) | No |

| Sacramento, California | 513,624 | Yes | Yes (City Manager) | No |

| Atlanta, Georgia | 506,811 | Yes | Yes | No |

| Kansas City, Missouri | 495,327 | Yes, pending** | Yes (City Manager) | Yes |

| Colorado Springs, Colorado | 478,221 | Yes | No | Yes |

| Omaha, Nebraska | 478,192 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Raleigh, North Carolina | 474,069 | Yes | Yes (City Manager) | No |

| Miami, Florida | 467,963 | No | ||

| Long Beach, California | 462,628 | No | ||

| Virginia Beach, Virginia | 449,974 | No | ||

| Oakland, California | 433,031 | Yes | No | No |

| Minneapolis, Minnesota | 429,606 | Yes | Yes (City Coordinator) | No |

| Tulsa, Oklahoma | 401,190 | Yes | Yes | No |

| Tampa, Florida | 399,700 | No | ||

| Arlington, Texas | 398,854 | Yes | Yes | N/A |

| New Orleans, Louisiana | 390,144 | Yes | Yes | No |

*As of September 2021.

** The job announcement for Chief Diversity Officer/Chief Equity Officer was posted but the position has not been filled as of July 2021.

President Biden and U.S. agencies are also working towards implementing Chief Diversity Officers at the federal level. Regarded as the most diverse presidential leadership team in history, President Biden’s Administration is comprised of 12 executive offices and 26 federal agency heads.[54] On President Biden’s first day in office, he charged one of these leaders, the Director of Domestic Policy, with coordinating efforts to embed equity across the full federal government. [55] These efforts then began at the agency level, with one agency, the Department of State, implementing a CDO in April 2021, as shown in Table 2. [56] In June 2021, President Biden signed an executive order requiring agencies to seek opportunities to establish senior-level agency CDOs, separate from their equal opportunity employment officers.[57] Since then, the Department of Justice announced a search for a CDO in August 2021.[58]

In addition to these cabinet-level agencies, CDOs have also emerged within agencies such as the United States Special Operations Command (USSOC) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).[59] The White House also implemented a Special Assistant to the President on Diversity.[60]

Table 2: Federal Agency Chief Diversity Officers*

| Cabinet Level Federal Agency / Executive Office of the President | CDO | Reporting to Agency/ Executive Office Head | CDO Hire Date |

| Department of State | Yes | Yes | Apr-21 |

| Department of Treasury | No | No | No |

| Department of Defense | No | No | No |

| Department of Justice | Yes, pending** | Not reported | Aug-21 |

| Department of Interior | No | No | No |

| Department of Agriculture | No | No | No |

| Department of Commerce | No | No | No |

| Department of Labor | No | No | No |

| Department of Health and Human Services | No | No | No |

| Department of Housing and Urban Development | No | No | No |

| Department of Transportation | No | No | No |

| Department of Energy | No | No | No |

| Department of Education | No | No | No |

| Department of Veteran Affairs | No | No | No |

| Department of Homeland Security | No | No | No |

| United States Environmental Protection Agency | No | No | No |

| United States National Intelligence Agency | No | No | No |

| Office of the United States Trade Representative | No | No | No |

| United States Ambassador to the United Nations | No | No | No |

| Council of Economic Advisers | No | No | No |

| Domestic Policy Council | Yes, equivalent*** | Yes (President) | Jan-21 |

| United States Small Business Administration | No | No | No |

| Office of Science and Technology Policy | No | No | No |

| Chief of Staff | No | No | No |

| Office of Budget and Management | No | No | No |

| Gender Policy Council | No | No | No |

| Office of Public engagement | No | No | No |

| Office of National Drug Control Policy | No | No | No |

| Office of Intergovernmental Affairs | No | No | No |

| Council on Environmental Quality | No | No | No |

| National Economic Council | No | No | No |

* As of September 2021.

** The job announcement for Chief Diversity Officer was posted but the position has not been filled as of August 2021.

*** The Director of Domestic Policy, who heads the President’s Domestic Policy Council, is charged with coordinating equity efforts across the full federal government, operating in a similar capacity to a federal CDO.

We are also seeing this trend in the private sector. Within the S&P 500, hiring of new diversity chiefs tripled between December 2019 and March 2021, with more than 60 percent of firms appointing their first-ever Chief Diversity Officer since the summer 2020 in response to the Black Lives Matter movement.[61]

As institutions sprint to hire Chief Diversity Officers, it is important that they do not stop at filling the seat. The CDO role is not to simply convince other governmental or corporate leaders of the importance of diversity, or to be reactive, symbolic, or crisis managers. CEOs and mayors must ensure that their CDOs have access to quantitative data and direct access to executive leadership. In doing so, leaders will ensure that their CDOs have a say in how their institutions do business, from how they write job descriptions and procurement documents to how they create budgets and citywide or company-wide policy. As we look to the future, we hope that cities like New York and businesses from the largest to the smallest can learn to embed diversity and inclusion into the very design of their institutions.

However, most of the City’s top vendors have not implemented this change. New York City’s top 50 vendors collectively received over $5 billion from the City of New York in FY 2021. As seen in Table 3, just 14 (28 percent) of the City’s 50 top vendors have publicly announced Chief Diversity Officers. Just six of these CDOs are reporting directly to the top. An additional 11 firms (22 percent) also have some diversity program, from supplier diversity programs to employee resource groups to diversity councils led by other members of their leadership. This means that half of the City’s top 50 vendors have not prioritized or institutionalized diversity within their own businesses.

As a result, of the $5 billion that these firms received, just $20.6 million—less than one percent—went to M/WBE subcontractors. And just three of these vendors were themselves M/WBEs. As the City transitions into new leadership, the City must not only hold itself accountable to diversity and inclusion, but the firms with which it does business must also reflect this value.

Table 3: Top 50 Business Receiving the Most City Dollars and Status of Chief Diversity Officers*

| Vendor Name | Minority Group | All Spending | M/WBE Prime Spending |

M/WBE Sub Spending |

M/WBE Spending % |

Chief Diversity Officer | Reporting to CEO | Hired after May 2020? |

| HOTEL ASSOCIATION OF NEW YORK CITY INC | Non-Minority | $414,508,154 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| CDW GOVERNMENT LLC | Non-Minority | $353,525,062 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| WASTE MANAGEMENT OF NEW YORK LLC | Non-Minority | $287,594,070 | $0 | $5,263,610 | 1.83% | Not reported | ||

| ACE AMERICAN INSURANCE CO. | Non-Minority | $258,921,928 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| DELL MARKETING LP | Non-Minority | $256,580,449 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Yes | No | No |

| SIEMENS ELECTRICAL LLC | Non-Minority | $210,095,522 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Yes | Yes | No |

| APPLE INC | Non-Minority | $201,112,499 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| U S BANK NATIONAL ASSOCIATION | Non-Minority | $185,560,186 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| WILLIS TOWERS WATSON NORTHEAST INC | Non-Minority | $163,287,915 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Yes | No | No |

| FJC SECURITY SERVICES INC | Non-Minority | $159,634,586 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| RELIANT TRANSPORTATION INC | Non-Minority | $148,450,437 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| SHI INTERNATIONAL CORP | Asian American | $132,805,112 | $132,805,112 | $0 | 100.00% | Not reported | ||

| INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES CORP | Non-Minority | $125,031,286 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Yes | No | No |

| SDI INC | Non-Minority | $122,694,171 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| GILBANE BUILDING COMPANY | Non-Minority | $121,424,117 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Yes | Yes | No |

| LAW OFFICES OF REGINA SKYER & ASSOCIATES LLP | Non-Minority | $121,337,748 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| LEON D. DEMATTEIS CONSTRUCTION CORP | Non-Minority | $115,309,870 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| CITNALTA CONSTRUCTION CORP | Non-Minority | $109,825,862 | $0 | $16,673,832 | 15.18% | Not reported | ||

| COVANTA SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS LLC | Non-Minority | $105,411,141 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| BORO TRANSIT INC | Non-Minority | $105,389,714 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| PIONEER TRANSPORTATION CORP | Non-Minority | $96,716,490 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| EXECUTIVE MEDICAL SERVICES PC | Non-Minority | $94,199,782 | $0 | $173,326 | 0.18% | Not reported | ||

| AECOM USA INC | Non-Minority | $92,186,068 | $0 | $6,625,809 | 7.19% | Yes | No | Yes |

| OPAD MEDIA SOLUTIONS LLC | Women | $92,007,564 | $92,007,564 | $0 | 100.00% | Not reported | ||

| CAC INDUSTRIES INC | Non-Minority | $91,114,176 | $0 | $4,516,001 | 4.96% | Not reported | ||

| LIRO PROGRAM AND CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT PE PC | Non-Minority | $88,426,748 | $0 | $463,713 | 0.52% | Not reported | ||

| TULLY CONSTRUCTION CO. INC. | Non-Minority | $88,419,637 | $0 | $3,139,427 | 3.55% | Not reported | ||

| BANK OF NEW YORK | Non-Minority | $82,167,935 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Yes | No | No |

| MOTOROLA SOLUTIONS, INC | Non-Minority | $79,813,246 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Yes | No | Yes |

| NANZO HOLDINGS INC | Non-Minority | $79,708,804 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| PRESIDIO NETWORKED SOLUTIONS GROUP LLC | Non-Minority | $76,028,048 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Yes | No | Yes |

| NTT DATA INC. | Non-Minority | $75,892,805 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PRIDE TRANSPORTATION SERVICES INC | Non-Minority | $74,547,055 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| GANNETT FLEMING ENGINEERS & ARCHITECTS PC | Non-Minority | $73,972,736 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| JR CRUZ CORP. | Non-Minority | $73,876,114 | $0 | $5,651,016 | 7.65% | Not reported | ||

| JETT INDUSTRIES INC | Non-Minority | $71,528,323 | $0 | $7,141,466 | 9.98% | Not reported | ||

| SLSCO LP | Non-Minority | $71,364,737 | $0 | $100,590 | 0.14% | Not reported | ||

| METROPOLITAN FOODS INC | Non-Minority | $70,567,629 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| MACK TRUCKS INC | Non-Minority | $69,788,539 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| KIEWIT-SHEA CONSTRUCTORS, AJV | Non-Minority | $67,591,549 | $0 | $5,677,551 | 8.40% | Not reported | ||

| GABRIELLI TRUCK SALES LTD | Non-Minority | $66,661,254 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| LEESEL TRANSPORTATION CORP | Non-Minority | $66,457,095 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| SPRAGUE OPERATING RESOURCES LLC | Non-Minority | $65,071,713 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| RISING GROUND INC | Non-Minority | $63,057,184 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| PRIME RIV LLC | Non-Minority | $61,910,856 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| TDX CONSTRUCTION CORP | Non-Minority | $60,804,588 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| WESTHAB, INC. | Non-Minority | $60,226,720 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| SNT BUS INC. | Non-Minority | $60,165,499 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| L&M BUS CORP | Non-Minority | $59,905,594 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| WHITESTONE CONSTRUCTION CORP | Non-Minority | $59,557,308 | $0 | $0 | 0.00% | Not reported | ||

| TOTALS | $5,932,235,623 | $224,812,675 | $55,426,341 | 259.59% | ||||

*As of August 2021.

Spending and Certification

Over the course of the last eight years, the City has dramatically expanded its database of vendors, certifying more than 10,500 vendors by FY 2021 – nearly triple the number of certified firms in 2015. However, certification has not translated into real opportunities for the vast majority of M/WBEs. As shown in Chart 3, of more than 10,500 certified M/WBEs, only 1,683—or 16 percent—received spending in FY 2021. This means that the number of certified M/WBEs that have not received City dollars increased from 3,354 in FY 2015 to 8,886—or 84 percent—in 2021. Chart 3 shows that since 2015, the share of M/WBEs receiving City dollars has never exceeded 22 percent.

Additionally, Chart 3 shows the share of M/WBEs receiving payments as prime contracts and subcontractors. The share of M/WBEs receiving prime contract payments decreased from 14 percent in FY 2020 to 12 percent in FY 2021, its lowest level since FY 2015. The share of M/WBEs receiving subcontractor payments remained the same at four percent.

Chart 3: Share of Certified M/WBEs Receiving Spending, FY 2015-FY 2021

M/WBE Contract Awards

The City of New York releases an annual M/WBE compliance report and the Agency Procurement Indicators Report which outline the City’s utilization with M/WBEs and efforts to improve contracting. This year, the City reported $1.166 billion in M/WBE contract awards, a $63 million increase from FY 2020. These awards represent 25 percent of contracts within the M/WBE program (subject to the M/WBE law), which totaled $4.6 billion.

However, as shown in Chart 4, M/WBE awards represent only 3.8 percent of all procurement awards in FY 2021, which was $30.4 billion. This means that just 15 percent of City contract dollars were subject to the M/WBE program in FY 2021. Comptroller Stringer has recommended since 2014 that the City expand the universe of contracts that are part of the M/WBE program as well as the vendors who can participate. This report has also recommended that the City develop a targeted plan to address areas where there is low M/WBE utilization even with M/WBE availability, including the Department of Education and COVID-19-related procurement.

In July 2020, Comptroller Stringer announced that the Office’s registration process would now include a rigorous review of M/WBE goals on all City contracts. The Comptroller’s Office now requires agencies to provide documentation of their M/WBE goals, such as goal-setting worksheets and market analyses. Between November 2020 and May 2021, the Comptroller’s Office registered 63 contracts subject to Local Law 1. Of these, 42 contracts, or about 67 percent, had M/WBE goals below 30 percent, as shown in Chart 5.

Chart 4: M/WBE Share of City Procurement, FY 2007 – FY 2021

Chart 5: M/WBE Utilization Goals Among Local Law 1-Eligible Contracts, November 2020 – May 2021

Citywide Grades

The Making the Grade report evaluates mayoral agencies that are subject to City M/WBE participation goals. In October 2019, the City Council updated the goals in the M/WBE law. These updates went into effect in April 2020. This is the first year in which report grades are based on Local Law 174 goals.

“Pay their invoices on time. You are waaaaaay behind paying my invoices in PASSPort. The City of NY owes me well over $300,000 soon to be $650,000 in past due invoices”

– A Woman-Owned Goods Company

Grades are based on actual spending in FY 2021, rather than the value of contracts awarded during the fiscal year, because contracts awarded may or may not result in M/WBEs actually receiving payments from the City.[62] Emergency procurement spending that otherwise falls within the M/WBE program, such as spending within the professional services industry, is included in this analysis given the City’s 2020 Executive Order stating that “all City agencies conducting procurements necessary to respond to the ongoing State of Emergency shall not categorically exempt emergency contracts from MWBE participation goals.”[63] In addition, this year’s report includes a grade for spending with Asian American-owned businesses within the professional services industry, in line with the City’s new goal.

Local Law 174 also established goals for Native American-owned businesses for the first time across every industry. However, this year’s report does not include grades for spending with Native Americans due to low certification and spending with businesses owned by Native Americans. In fact, as of July 2021, New York City only certified four Native American-owned firms and spent $0 with these companies.

In FY 2021, New York City mayoral agencies spent $1.27 billion with M/WBEs. This is an additional $261 million from FY 2020 and an increase of more than $900 million since FY 2014, the first year of this report. The City fell to a “C-” grade in FY 2021 when graded against the updated goals in Local Law 174 after two consecutive “C” grades and five years at the “D” and “D+” range from FY 2014.

Broken down by group, the City earned a “B” grade with Asian Americans, a “D” with Hispanic Americans and women-owned businesses, and an “F” with African Americans. Overall, the City has improved its grades with Asian Americans, with whom it received a “D” grade in FY 2014. It also increased its grades with Hispanic Americans and women, with whom the City received failing “F” grades in FY 2014. However, the City has been unable to improve its “F” with African American-owned businesses over the last eight years.

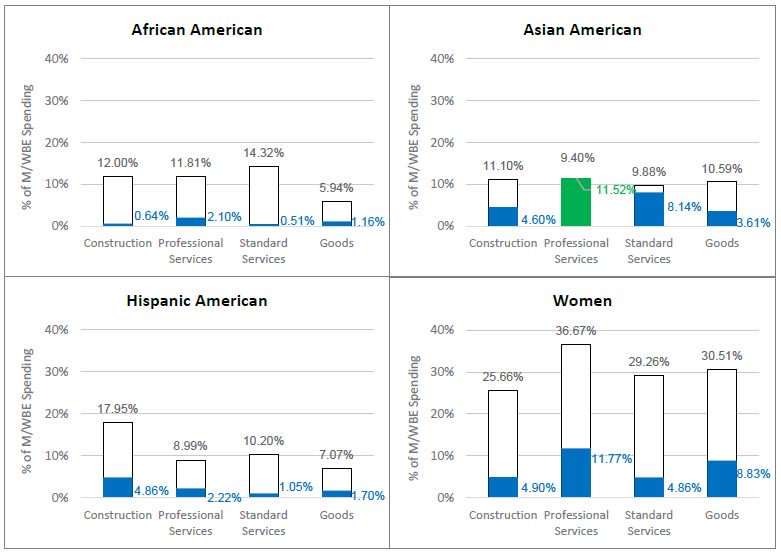

The Comptroller’s Office has provided Citywide Progress Reports for the last four years to help agencies track their spending with M/WBEs throughout the fiscal year. These progress reports provide a quarterly analysis of each agency’s spending by minority group and industry compared with the goals written in the M/WBE law. As shown in Chart 6, citywide spending remains low as compared with the City’s legal goals. The City exceeded its 9.4 percent goal in professional services with Asian Americans in the first year of the goal. However, all other goals were unmet, including the City’s goal in standard services with Asian Americans and its construction goal with Hispanic Americans, which were both met in FY 2020 under the previous Local Law 1 standards. In addition, the City spent two percent or less across every industry with African American-owned firms and less than 12 percent across every industry with women-owned businesses.

Chart 6: Citywide Spending Compared with Local Law 174 Goals, FY 2021

Note: Making the Grade does not include grades for spending with Native Americans due to low certification and spending with businesses owned by Native Americans. As of July 2021, New York City only certified four Native-American owned firms and spent $0 with these companies.

Agency Grades

In FY 2021, of the 32 mayoral agencies graded, two received an “A” grade, four received a “B” grade, 12 received a “C,” 13 received a “D,” and one received an “F.” Overall, as compared with FY 2020, three grades improved, 11 grades remained the same, and 18—more than half—declined. Spending with M/WBEs declined within 18 agencies in the last year. However, six agencies whose grades fell actually increased their spending with M/WBEs. This means that the grade decline for these agencies was partially due to updates in the City’s Local Law goals.

Overall, agencies have improved their spending with M/WBEs since FY 2014, the year this report was introduced. Compared with FY 2014, 29 agencies—about 90 percent—increased their spending with M/WBEs.[64] This is also reflected in improvement in agencies’ grades: in FY 2014, there were no “A” grades, just two agencies earned “B” grades, nine agencies received “C” grades, 17 received “D” grades, and four received “F” grades.

Two agencies—the Commission on Human Rights and the Department for the Aging—received their fifth consecutive “A” grades. Both spent more than 50 percent of their Local Law 1-eligible dollars with M/WBEs. Two agencies—the Administration for Children’s Services and the Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings—maintained their “B” grades from FY 2020, and two agencies—the Business Integrity Commission and the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection—increased their grades from “C” to “B” this year. All of these agencies have improved their grades from the “C” and “D” range in FY 2014.

Of the 12 agencies with “C” grades, four had maintained their marks since FY 2020: the Department of Buildings, Department of Finance, Fire Department, and Human Resources Administration. The remaining eight agencies, however, decreased their marks from FY 2020. The Department of Youth and Community Development fell from an “A” grade, while the Civilian Complaint Review Board, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Department of Probation, Department of Parks and Recreation, Landmarks Preservation Commission, Police Department, and Department of Small Business Services, fell from “B” grades last year.

Within the “D” grade, the City saw three agencies maintain their grade from FY 2020: the Departments of Citywide Administrative Services, Homeless Services, and Sanitation. The Department of Emergency Management, which received an “F” in FY 2020, earned an increase to a “D” grade this year. However, nine agencies fell to the “D” grade range in FY 2021: the Departments of City Planning, Design and Construction, Environmental Protection, Correction, Information Technology and Telecommunications, and the Law Department from “C” grades, and the Department of Cultural Affairs, Department of Housing Preservation and Development, and the Taxi and Limousine Commission from “B” grades.

The Department of Transportation, the only “F” grade in FY 2021, fell from a “D” grade, spending just five percent of its Local Law 1-eligible dollars with M/WBEs.

While not a mayoral agency, the Comptroller’s Office is included annually in this report and earned its third consecutive “A” grade in FY 2021 when graded against the City’s new standards, up from a “C” in FY 2014. The Comptroller’s Office spent 53 percent of its Local Law 1-eligible dollars with M/WBEs this fiscal year, as compared with 13 percent in FY 2014.

As Chart 7 shows, most City agencies improved their grades between FY 2014 and FY 2020, with most agencies earning “B” and “C” grades in FY 2020 and mostly “D” grades in FY 2014. However, FY 2021 saw a rise in “D” grades and a decline in “B” grades.

Chart 8 shows that the City received a “C-“ grade because agencies as a whole did not spend significantly with M/WBEs compared with Local Law 1 goals. The 26 agencies that received “C,” “D,” and “F” grades account for 99 percent of the City’s total M/WBE program spending, while the six agencies that received “A” and “B” grades account for just one percent. As the City moves forward, growth to an “A” grade, especially with the updated Local Law 174 goals, will require additional improvement in M/WBE spending among the agencies that have continually maintained the lowest grades and highest proportion of the City’s Local Law 1-eligible procurement spending.

Table 4 provides each agency’s assigned grade and compares grades from FY 2021 to the last seven fiscal years.

Chart 7: Agency Letter Grades, FY 2014 – FY 2021

Chart 8: Composition of Citywide M/WBE Grade by Total Agency Spending, FY 2021

“Provide low range projects that don’t require bonding or security deposits and get MBEs back to work”

– A Hispanic American-Owned Construction Business in Queens

Table 4: Comparison of FY 2014 – FY 2021 Grades: Citywide

| Agency Name | FY14 | FY15 | FY16 | FY17 | FY18 | FY19 | FY20 | FY21 | FY20 – FY21 |

| New York City | D | D+ | D+ | D+ | D+ | C | C | C- | – |

| Office of the Comptroller | C | C | B | B | B | A | A | A | – |

| Commission on Human Rights | C | C | B | A | A | A | A | A | – |

| Department for the Aging | D | C | B | A | A | A | A | A | – |

| Administration for Children’s Services | C | C | C | C | C | B | B | B | – |

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | D | C | D | C | C | C | B | B | – |

| Business Integrity Commission | D | D | F | C | D | C | C | B | ▲1 |

| Department of Consumer and Worker Protection | D | C | B | B | B | C | C | B | ▲1 |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | C | C | C | B | C | B | A | C | ▼2 |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | C | C | D | B | B | C | B | C | ▼1 |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | C | C | C | B | A | A | B | C | ▼1 |

| Department of Probation | C | D | D | C | B | B | B | C | ▼1 |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | D | C | C | B | B | B | B | C | ▼1 |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | B | B | C | B | C | B | B | C | ▼1 |

| Police Department | C | B | B | C | ▼1 | ||||

| Department of Small Business Services | D | F | B | A | C | B | B | C | ▼1 |

| Department of Buildings | D | D | F | F | D | C | C | C | – |

| Department of Finance | F | D | C | D | D | D | C | C | – |

| Fire Department | D | D | C | C | C | C | C | C | – |

| Human Resources Administration | D | D | D | D | D | C | C | C | – |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | B | C | C | B | B | B | B | D | ▼2 |

| Department of Housing Preservation and Development | D | A | A | B | C | C | B | D | ▼2 |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | D | D | D | B | B | B | B | D | ▼2 |

| Department of City Planning | C | C | B | C | C | B | C | D | ▼1 |

| Department of Design and Construction | D | C | D | D | C | C | C | D | ▼1 |

| Department of Environmental Protection | F | F | D | D | D | D | C | D | ▼1 |

| Department of Correction | D | D | C | D | C | C | C | D | ▼1 |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | F | D | D | D | C | B | C | D | ▼1 |

| Law Department | C | D | C | D | C | C | C | D | ▼1 |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | D | D | D | F | F | D | D | D | – |

| Department of Homeless Services | D | D | D | D | D | C | D | D | – |

| Department of Sanitation | F | F | F | F | D | D | D | D | – |

| Office of Emergency Management | D | D | D | D | D | C | F | D | ▲1 |

| Department of Transportation | D | D | D | F | D | D | D | F | ▼1 |

Grading by Minority Group

For their spending with African American-owned firms, four agencies received “A” grades, no agencies received “B” grades, one received a “C” grade, two received “D” grades, and 25 received “F” grades in FY 2021.

For their spending with Hispanic American-owned firms, six agencies received “A” grades, two agencies received “B” grades, three received “C” grades, seven received “D” grades, and 14 received “F” grades in FY 2021.

For their spending with women-owned firms, one agency received an “A” grade, one agency received a “B” grade, four received “C” grades, six received “D” grades, and 20 received “F” grades in FY 2021.

For their spending with Asian American-owned firms, 19 agencies received “A” grades, two agencies received “B” grades, four received “C” grades, six received “D” grades, and one received an “F” grade in FY 2021.

Tables 5 through 8 provide assigned grades for agencies by minority group over the last eight years.

Additional information about individual agency grades is available in Appendix A. The worksheets used to calculate each agency grade appear in Appendix B and a complete explanation of the report’s methodology can be found in Appendix D. Subcontract data for each agency can be found in Appendix C.

“It doesn’t appear that city agencies are taking MBE companies seriously. My company offers products that would save city owned properties thousands of dollars and increase efficiency but they ignore us. Meanwhile, we do more business outside of the 5 boroughs and we’re in [the Bronx].”

– A Hispanic American-Owned Goods business

Table 5: Agency Grades with African American-Owned Firms, FY 2014 – FY 2021

| Agency Name | FY14 | FY15 | FY16 | FY17 | FY18 | FY19 | FY20 | FY21 |

| Citywide | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Office of the Comptroller | F | F | F | F | D | A | A | A |

| Administration for Children’s Services | C | D | D | D | D | D | D | C |

| Business Integrity Commission | F | F | F | C | D | C | F | F |

| Commission on Human Rights | A | C | F | A | A | A | A | A |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | D | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | C | F | C | F | A | A | A | F |

| Department of City Planning | F | F | D | D | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Consumer and Worker Protection | F | D | C | B | F | F | D | A |

| Department of Design and Construction | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Environmental Protection | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department for the Aging | D | B | A | A | B | A | A | A |

| Department of Homeless Services | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Buildings | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Correction | F | F | F | F | F | D | D | F |

| Department of Finance | F | F | F | F | F | F | D | F |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | F | F | F | F | D | D | D | F |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Probation | C | F | F | F | F | C | C | F |

| Department of Transportation | F | F | F | F | D | F | F | F |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | F | F | F | F | F | F | D | F |

| Department of Sanitation | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | A | A | A | A | B | A | A | D |

| Fire Department | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Housing Preservation and Development | F | B | B | C | D | D | D | F |

| Human Resources Administration | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Law Department | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | D | C | D | F | F | D | F | F |

| Police Department | F | F | D | F | ||||

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | D | F | F | F | F | F | B | D |

| Office of Emergency Management | F | F | F | F | F | C | F | F |

| Department of Small Business Services | F | F | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | F | F | F | F | D | F | F | F |

Table 6: Agency Grades with Hispanic American-Owned Firms, FY 2014 – FY 2021

| Agency Name | FY14 | FY15 | FY16 | FY17 | FY18 | FY19 | FY20 | FY21 |

| Citywide | F | D | D | D | D | C | B | D |

| Office of the Comptroller | C | B | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| Administration for Children’s Services | F | F | F | C | D | B | A | A |

| Business Integrity Commission | F | D | F | D | F | F | F | B |

| Commission on Human Rights | C | C | A | A | A | A | C | B |

| Civilian Complaint Review Board | F | A | F | A | A | A | A | A |

| Department of Citywide Administrative Services | F | F | F | F | F | D | D | F |

| Department of Cultural Affairs | A | B | F | A | D | A | A | F |

| Department of City Planning | F | D | A | D | D | C | F | C |

| Department of Consumer and Worker Protection | F | D | B | A | A | A | C | D |

| Department of Design and Construction | D | C | D | D | C | A | A | C |

| Department of Environmental Protection | F | F | F | F | F | D | C | F |

| Department for the Aging | F | C | C | A | A | A | A | A |

| Department of Homeless Services | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Buildings | F | F | F | F | D | A | A | D |

| Department of Correction | A | C | C | F | D | D | D | F |

| Department of Finance | F | F | D | D | F | F | F | D |

| Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | D | F | D | A | A | A | C | D |

| Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications | F | F | F | F | F | D | D | F |

| Department of Probation | C | A | D | F | A | A | A | A |

| Department of Transportation | F | D | D | F | D | C | D | F |

| Department of Parks and Recreation | D | B | B | A | A | A | A | D |

| Department of Sanitation | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Department of Youth and Community Development | C | C | F | D | D | C | C | F |

| Fire Department | F | F | D | B | C | B | D | D |

| Housing Preservation and Development | D | A | A | B | D | C | C | F |

| Human Resources Administration | F | F | F | F | F | D | F | F |

| Law Department | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F |

| Landmarks Preservation Commission | A | A | C | B | C | A | A | A |

| Police Department | D | B | B | D | ||||

| Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings | F | A | C | F | D | F | D | A |

| Office of Emergency Management | D | D | D | D | F | D | F | F |

| Department of Small Business Services | F | F | C | A | F | D | C | F |

| NYC Taxi and Limousine Commission | D | D | A | A | A | A | A | C |

Table 7: Agency Grades with Women-Owned Firms, FY 2014 – FY 2021