New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer’s Investigation into Child Lead Exposure

Executive Summary

Fifteen years after the passage of landmark legislation designed to eliminate the scourge of lead poisoning in New York City (Local Law 1 of 2004), thousands of children across the five boroughs remain at risk of exposure to lead paint and the severe, irreversible health consequences it can inflict. While Local Law 1 has helped to dramatically drive down rates of lead poisoning, the City has failed to achieve the goal it set out at the time of the law’s passage, namely “the elimination of childhood lead poisoning by the year 2010.” Between January 1, 2013 and October 10, 2018 alone, 26,027 children under the age of 18 tragically tested positive for elevated blood lead levels of 5 micrograms per deciliter (5 mcg/dL) or greater, the current benchmark for public health action recommended by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[1]

This investigative report by Comptroller Scott M. Stringer examines how City agencies charged with eradicating childhood lead poisoning for years missed crucial opportunities to protect children from the immense harms associated with lead exposure. At its core, the investigation exposes a clear failure by the City to leverage its own data related to lead exposure and utilize that data to precisely and methodically inspect buildings and areas most likely to pose a threat to children.

Specifically, the Comptroller’s Office found that for years, the City allowed crucial data—namely thousands of children’s blood lead test results collected by the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH)—to remain siloed within DOHMH, rather than using the data to proactively pinpoint lead exposure hotspots for inspection by the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD). Instead, the City allowed HPD to rely almost exclusively on a reactive, complaint-driven inspection protocol, all but ignoring the hard, actionable data in possession of a sister agency. In retrospect, the absence of a coordinated, interagency strategy between DOHMH and HPD to eliminate lead paint hazards constitutes a missed opportunity to protect children and create a safer, healthier city.

In January 2019, while this investigation was in progress, the City issued its LeadFreeNYC plan, alongside a number of related laws enacted by the City Council. These efforts are designed to advance the goal of eliminating lead poisoning in the City and are to be commended. However, unless the City acts with urgency to address how HPD prioritizes inspections and makes use of DOHMH data, children could still be put at risk. The City’s protocol relating to inspections of buildings with lead paint is still primarily reactive, with a goal of only 200 proactive HPD inspections and audits per year. Moreover, to date, the City has added only 36 percent of the funding it stated was necessary to implement LeadFreeNYC. With thousands of known buildings across all five boroughs associated with multiple cases of child lead exposure, the City must fully fund the resources necessary to enforce Local Law 1 and prevent new cases of children’s lead exposure.

The Comptroller’s investigation, examining the City’s response to lead in the period between January 1, 2013 and October 10, 2018, includes a number of findings that demonstrate the need for increased coordination in the City’s fight against lead exposure:

- DOHMH received blood-lead test results detailing the names and addresses of hundreds of thousands of children across the City, yet at no time during the period examined did DOHMH share that information with HPD. In the absence of a City policy to use that data to target HPD’s lead-enforcement efforts, 9,671 buildings under HPD jurisdiction, housing 11,972 children diagnosed with lead exposure (5 mcg/dL or greater), were not inspected by HPD lead inspectors. Indeed, HPD did not send lead inspectors to 503 buildings under its jurisdiction that DOHMH data showed had three or more children with blood levels at or above the 5 mcg/dL CDC action level.It is true that the City’s standard lagged behind the federal benchmark of 5 mcg/dL during the period examined and did not require a city lead inspection unless a child registered a much higher blood lead level of 15 mcg/dL. That said, the City’s stated goal was the elimination of child lead exposure, and it had powerful tools available—including relevant data in DOHMH’s possession—that it failed to use. By coupling DOHMH data with HPD enforcement power, the City could have targeted buildings where it had good reason to suspect that children may have been exposed to lead paint hazards. Having now adopted the more stringent federal benchmark for lead exposure, the City must commit to inspecting these 9,671 buildings identified in this report and make homes across the five boroughs safer for children.

- Of the 11,972 lead-exposed children (blood lead levels at or above 5 mcg/dL) in HPD-jurisdiction buildings that went uninspected for lead paint, 2,749 tested positive for lead exposure even after another child in the same building had done so, based on an analysis of information in DOHMH’s Childhood Blood Lead Registry. In retrospect, DOHMH’s accumulated blood test data should have served as a clear warning sign that children were being exposed to lead paint hazards, possibly in their own homes, sufficient to warrant action of the part of HPD, which potentially could have prevented future instances of lead exposure.Even as HPD undertook a total of 153,516 lead paint inspections during the time period examined, mostly in response to tenant complaints, those inspections never reached nearly two-thirds—63 percent—of the buildings that were both under its jurisdiction and associated with a case of child lead exposure.

- In cases where HPD’s lead unit did complete at least one inspection in a building with a documented case of child lead exposure, the inspections yielded 7.6 violations per building on average – showing the value of concentrating inspection activities in clear lead exposure hotspots.

- Of the 9,671 buildings that went uninspected for lead paint by HPD and were associated with at least one case of child lead exposure, 572 were in NYCHA complexes. According to HPD officials, in properties where another government agency, such as NYCHA, is involved in managing housing it is that agency’s responsibility to address lead issues. Accordingly, lead paint complaints that NYCHA residents made through the City’s 311 system were routed to NYCHA and were not addressed by HPD. Consequently, during the period examined by this report, NYCHA was allowed to police its own compliance with the New York City Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Act, also known as Local Law 1 of 2004 (LL1).

- The Comptroller’s investigation revealed that by responding only to resident complaints rather than proactively seeking out lead exposure hotspots, HPD’s enforcement resources did not align with areas with high levels of lead exposure. For instance, the borough of Manhattan registered a rate of 13 inspections per child with lead exposure, versus only four inspections per case in Brooklyn—even though DOHMH records showed that Brooklyn had six times more lead exposed children than Manhattan during the period examined.

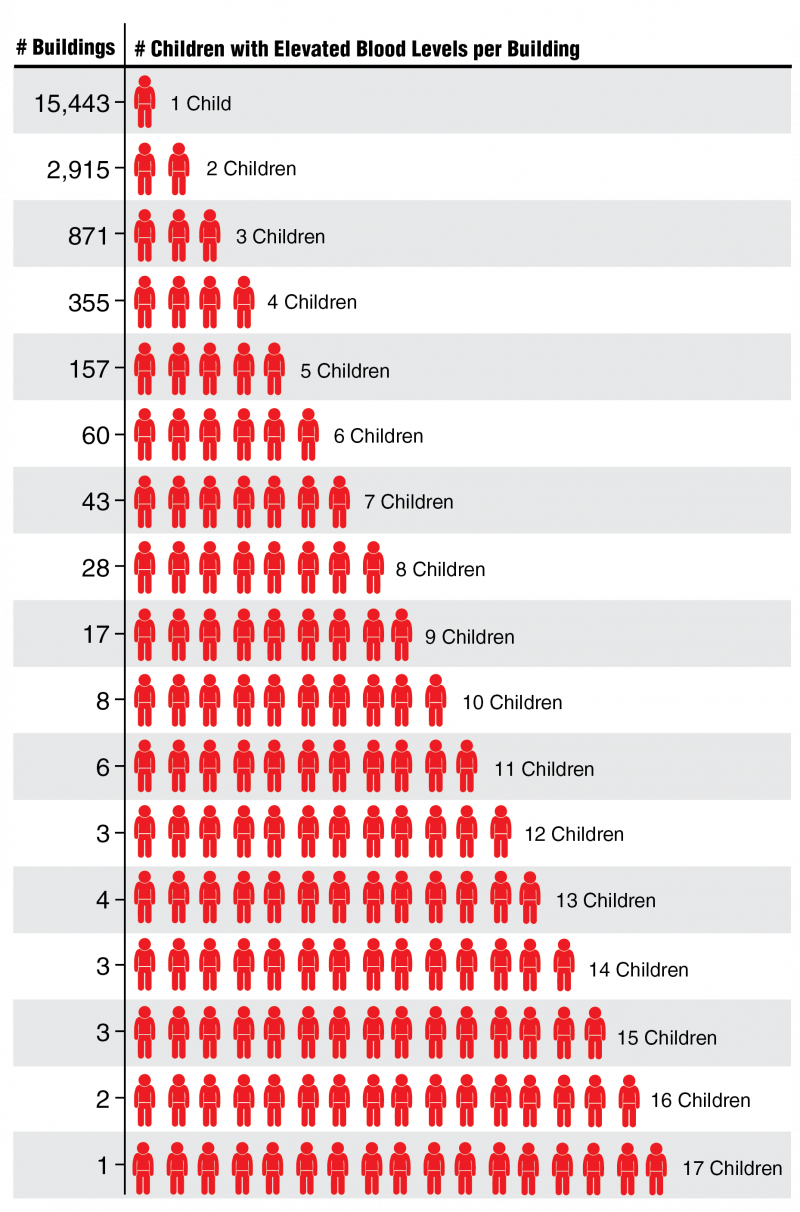

- During the period under examination, 1,561 buildings within New York City were home to three or more children diagnosed with elevated blood levels, 1,420 of which were under HPD’s jurisdiction. One Brooklyn apartment building had 17 individual children diagnosed with elevated blood lead levels. DOHMH records show that the 50 buildings with the highest number of children who tested positive for elevated lead levels were home to 547 children. Ultimately, 35 percent of buildings associated with three or more children with lead exposure were never visited by an HPD lead paint inspector.

- While LL1 mandates that landlords take proactive measures to prevent lead poisoning, the City failed to use its statutory authority to enforce compliance. Over the period studied in this report, HPD issued zero violations for building owners’ failures to comply with LL1’s turnover requirements and zero violations for their failures to perform mandated annual inspections, two key provisions of the law that obligate landlords to regularly inspect the vast numbers of rental housing units with potential lead-based paint hazards—a task for which HPD does not have unlimited capacity. Those enforcement gaps have left the preventive goals of LL1 unfulfilled and diverted limited City resources, resulting in the City’s enforcement of LL1 remaining on an entirely complaint-driven basis.

- Official statistics are likely to significantly understate the extent of child lead poisoning and exposure in New York City. In 2017 approximately 22,000 children—20 percent of all children who should have been tested—under the age of three had not been tested for lead poisoning as required by New York State law, according to DOHMH’s data. The proportion of untested children has increased markedly, from a low of 7 percent in 2009 to a high of 20 percent in 2017.

While lead exposure can occur through contact with contaminated toys, water, soil, or other sources, evidence suggests that the primary source of childhood lead exposure in the United States is lead paint in older, deteriorating housing.[2] This suggests that the City should focus fact-finding efforts—such as lead-hazard investigations, inspections, and audits—on buildings where children with elevated blood lead levels are known to reside, and particularly in older buildings where lead-based paint hazards are more likely to persist. In such cases, City investigators should also determine whether building owners complied with their obligations under applicable laws and regulations, and enforcement actions should be pursued purposefully and aggressively in cases of non-compliance to spur safe and effective preventive actions by all responsible owners.

The Comptroller offers a series of additional policy recommendations in keeping with the City’s goal of helping to eliminate childhood lead exposure:

- Coordinate agency responses. The City must take a more proactive approach to eliminating the dangers posed by lead paint. HPD and DOHMH should fully coordinate their efforts and leverage every tool and data resource in their arsenal to identify and remedy potential lead paint hotspots before children are put at risk. The City should start by conducting full investigations in the 9,671 buildings identified in this report as having been associated with cases of elevated blood lead levels in children, any buildings with presumed lead paint content in high-lead exposure zones, and buildings with common ownership and/or management with buildings with histories of lead-based paint hazards. The City’s LeadFreeNYC plan includes the creation of a “Building Lead Index” that will target a limited number of buildings each year based on the building’s history of violations and whether the building is located in an area with high rates of child lead exposure. While compiling a Building Lead Index is a first step towards a more proactive approach to inspections, the City should as a matter of urgency do more to investigate the buildings most linked to actual cases of lead exposure.

- Fully fund LeadFreeNYC now tasks HPD with doing much more to police LL1 requirements, including more inspections and audits. The City estimates the cost of these enforcement actions at $25 million for FY2020 through FY2023.[3] However, the City’s FY2020 Budget includes a total of only $9 million allocated over that period. If the City is committed to its own plan, the City must fully fund the entire HPD component of LeadFreeNYC.

- Improve enforcement of Local Law 1. HPD must better enforce provisions of LL1, including (1) landlords’ obligations to annually inspect for, identify, and remediate lead-based paint hazards in the apartments and common areas of the multiple dwellings built before 1960 and certain other buildings where children under age 6 reside; and (2) landlords’ obligations to remove lead-based paint hazards when apartments turn over, before a new tenant moves in.

- Test every child. DOHMH must ensure all children have their blood tested at ages 1 and 2 as required by law. With testing rates well below full compliance, DOHMH should mobilize more resources to reach out to families with children in buildings with known histories of lead contamination to ensure they are tested.

Introduction

The Dangers of Lead-Based Paint and Dust

Lead is a naturally occurring element and a well-known human neurotoxin that can irreversibly damage the developing brains and nervous systems of infants and young children.[4] People can come into contact with lead through both their indoor and outdoor environments, including water, soil, air, household products, and, most commonly, lead-based paint and dust.[5] Young children’s hand-to-mouth behavior increases their exposure.[6] Research indicates that “70% of children’s lead exposure is from lead-based paint in the home.”[7] As noted on DOHMH’s website, “The most common source of lead poisoning for children in New York City is peeling lead paint and its dust.”[8]

What We Investigated

The Comptroller’s Office conducted an independent investigation, initiated in July 2018, to look into the City’s procedures under LL1 for addressing lead poisoning hazards affecting children, primarily those residing in privately owned, multi-family buildings. The findings are based on analyses of data provided by the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH), and publicly available sources including NYC Open Data, as well as interviews with City officials and testimony obtained from experts and other community members. The investigation focused primarily on a period of just under six years, from January 1, 2013 through October 10, 2018. For additional detail on how this investigation was conducted, please refer to the methodology section of the report.

While some information regarding the New York City Housing Authority is presented in this report, it is not the focus of this investigation given ongoing monitoring by the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York and NYCHA’s independent monitor into NYCHA’s record on lead and lead remediation. Additionally, while any case of child lead exposure within public or private housing is unacceptable, research suggests that the rate of children testing positive for elevated blood lead levels is twice as high in privately owned housing citywide than in NYCHA developments.[9]

Anonymized data that DOHMH provided to the Comptroller’s Office shows that 26,027 individual children tested with venous blood lead levels at or above 5 mcg/dL, the CDC reference level, from January 1, 2013 to October 10, 2018, including 9,234 children who tested above that level two or more times. As many as 1,844 children had blood lead levels exceeding 15 mcg/dL, three-times the CDC’s reference standard.

Local Law 1

In 2004, New York City enacted the New York City Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Act, also known as Local Law 1 of 2004 (LL1). The law was intended to eliminate lead hazards before children were exposed, naming “primary prevention” as the “essential tool” to combat childhood lead poisoning.[10] Even though rates of childhood lead poisoning have greatly decreased in the 15 years since LL1’s enactment, children are still being lead-poisoned; regrettably, the law’s goal of eradicating this disease by 2010 was not achieved.[i]

The majority of LL1’s provisions are applicable to multiple dwellings, with specific provisions imposing obligations on the owners of multiple dwellings that were built before 1960, or before 1978 if the owner knows that lead paint is present, where a child under age 6 resides.[11] The law establishes the presumption that paint within any multiple dwelling erected before January 1, 1960 is lead-based.[12] In some cases the law extends to owners who rent out their one- and two-family homes to tenants.

Generally, LL1 specifies actions that property owners must take to prevent children’s exposure to lead, and gives enforcement responsibilities to two City agencies—HPD and DOHMH. Property owners are responsible for ensuring that the residences of young children are safe from lead hazards by performing annual visual inspections, remediating all lead-based paint hazards, and removing or permanently covering lead paint on friction surfaces, such as doors and window frames when apartments turn over, and always adhering to safe work practices when performing any work that will disturb lead-based paint.[13]

According to City officials interviewed during the investigation, the City has pursued a multi-pronged approach to address the problem of childhood lead poisoning. As relevant to LL1, broadly speaking, DOHMH for years intervened in cases where a child’s blood lead level exceeded the threshold established by LL1—15 mcg/dL for the five-plus year period we reviewed. Effective August 2019, LL1 sets a lower threshold for DOHMH intervention—a blood lead level of 5 mcg/dL or higher, aligned to the CDC reference standard.[14] DOHMH is responsible for investigating the source of the child’s lead poisoning, ensuring that the conditions creating the elevated blood level are addressed, and providing the child’s family with medical referrals for treatment and testing. HPD, broadly speaking, receives complaints that potentially involve lead-based paint hazards in multiple dwellings, conducts inspections, and remediates lead hazards when landlords fail to do so. For additional details on the respective roles and responsibilities of DOHMH and HPD under LL1, see the appendix to this report.

The City’s Lead Standard Lagged behind the Federal Government’s

In May 2012, the CDC set as its standard for remedial action a blood lead level of 5 mcg/dL or greater in any child.[15] For children testing at or above that level, the CDC recommended—and continues to recommend—an environmental assessment to identify potential sources of lead exposure.[ii],[16] Unfortunately, DOHMH standards for a hands-on response by the City lagged behind that clear-cut benchmark for years and, up until recently, the City seemed to offer a hodgepodge of often conflicting numbers and enforcement criteria.

- From 2004 to 2018, LL1 required DOHMH to conduct environmental investigations only when children tested with blood lead levels of 15 mcg/dL and above, a level much higher than the CDC standard.

- As of 2012, CDC recommended an “environmental assessment of [the child’s] detailed history to identify potential sources of lead exposure” when a child’s blood lead level tested in the range of 5 mcg/dL to 9 mcg/dL (“level 5” for this analysis). In conjunction with the environmental assessment, the CDC also recommended an “environmental investigation including [a] home visit to identify potential sources of lead exposure” when a child’s blood lead level was in the range of 10 to 19 mcg/dL (“levels 10 to 19”).[17]

- Under LL1, through mid-2018, DOHMH’s environmental investigations, initiated at levels of 15 mcg/dL and above, included a home visit and inspection by a certified public health sanitarian using an x-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzer to determine whether lead paint hazards existed in the lead-exposed child’s home.[18]

- At levels of 15 mcg/dL and above, DOHMH policy was to conduct a comparatively rigorous investigation that appears to have more than satisfied CDC’s summary recommendation.

- However, although DOHMH’s specific form of investigation was rigorous, the threshold at which the agency initiated its investigation was significantly higher—a greater concentration of lead in a child’s blood—than that recommended by the CDC.

- Moreover, DOHMH’s, and LL1’s, high minimum threshold for direct City/ DOHMH investigation may have left a wide swath of childhood lead exposure cases uninvestigated by the City—tens of thousands of children who tested at level 5 and above—while DOHMH’s threshold for hands-on action remained at level 15.

- In its 2012 annual report to the City Council, DOHMH did acknowledge CDC’s adoption of a “reference blood lead level” of 5 mcg/dL but nevertheless defined “elevated blood lead level” as “a blood lead level of 10 mcg/dL or greater,” or double the CDC’s standard at that time.

- It took until DOHMH’s annual report in 2017 before the City began to define an elevated blood lead level as one of “5 mcg/dL or above.”

- Finally, in July 2018, the City announced that DOHMH would conduct home inspections for all children under 18 years of age with blood levels of 5 mcg/dL or greater—in effect matching the benchmark recommended by CDC, albeit after a six-year lag.[19]

Other actions by DOHMH suggest that even before the agency had instituted the recommended CDC standard for a lead-exposure investigation, it tacitly recognized that public health interventions were warranted at lower levels. For example, the agency conducted a pilot program in 2010 in which it inspected the homes of newborns and younger children with blood lead levels below 15 mcg/dL, and between 2015 and 2017 DOHMH also conducted limited home inspections for such newborns and younger children. However, despite the clear scientific consensus that lead levels at or above 5 mcg/dL constituted a risk to children, that program was not expanded at that time.

City’s Progress in Reducing Childhood Lead Poisoning

While the Comptroller’s analysis focuses on children’s blood lead tests conducted from January 1, 2013 to October 10, 2018, it is important to acknowledge that rates of elevated blood lead levels have declined significantly since the passage of LL1. By DOHMH’s estimate, the number of children under six years of age with elevated blood lead levels of 5mcg/dL or greater has declined by 89 percent since 2005.[20] The marked decrease in lead exposure rates is commendable and is due to the work of committed physicians, the City, and growing public awareness about the dangers of lead exposure. However, despite progress the City has failed to achieve the stated goal of LL1—the elimination of childhood lead poisoning in New York City by 2010.[21]

Investigative Findings

Two Agencies, Zero Communication

As a result of the siloing of data between the City’s DOHMH and HPD, thousands of buildings where lead-exposed children lived went uninspected for lead paint hazards by HPD from 2013 through 2018. Specifically, the Comptroller’s investigation showed that between January 1, 2013 and October 10, 2018, HPD’s lead inspection unit neither performed nor attempted to perform a lead inspection in 9,671 buildings where, according to DOHMH’s own Childhood Blood Lead Registry, 11,972 children with elevated blood lead levels at or above 5 mcg/dL lived.[iii]

Those uninspected buildings constitute 63 percent of the buildings under HPD’s jurisdiction in which one or more children were found to have elevated blood lead levels. They include 503 buildings where at least three children with elevated blood lead levels resided. If buildings where HPD attempted an inspection but could not gain access are included, a total of 12,642 such buildings went uninspected by HPD’s lead unit. [iv]

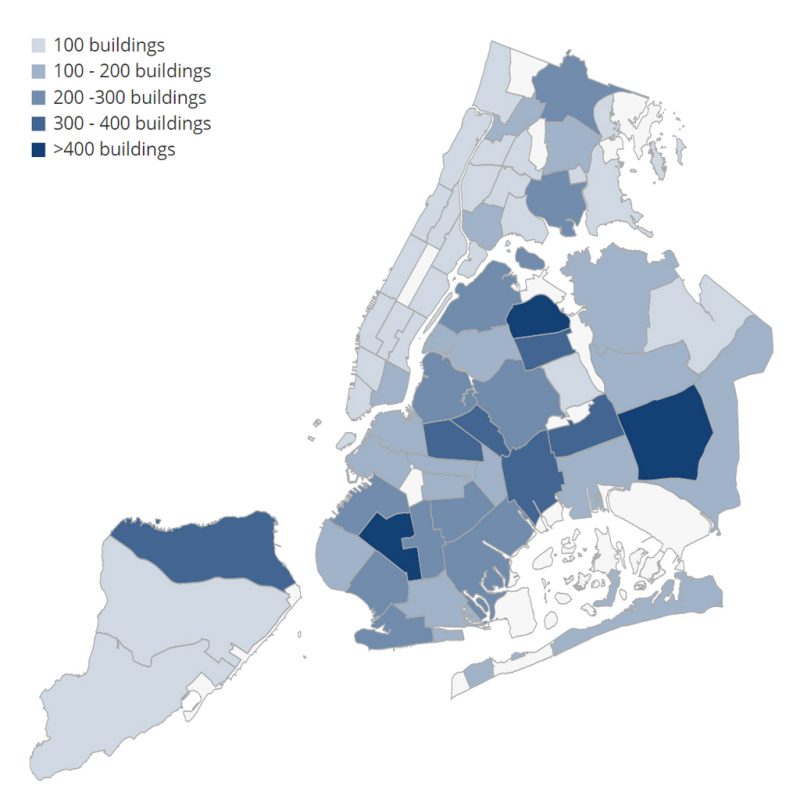

As can be seen in Map 1, these uninspected building are not evenly distributed across the city and are concentrated in specific neighborhoods.

Map 1: Uninspected Homes of Lead-Exposed Children

(In Buildings Subject to HPD Jurisdiction)

Moreover, 2,749 of the abovementioned 11,972 children lived in buildings that remained uninspected by HPD’s lead unit even after other children in the same buildings had elevated blood lead levels recorded in DOHMH’s Childhood Blood Lead Registry. It is possible that lead-based paint hazards existed in those children’s homes and went undiscovered by City agencies because the data was not used proactively to target inspections. In cases where HPD’s lead unit did complete an inspection in a building with a documented case of child lead exposure, the inspections yielded 7.6 violations per building on average – showing the value of focusing efforts on such buildings.

DOHMH historically has shared lead-exposure information with HPD in a relatively narrow category of cases—only after DOHMH found a lead-based paint hazard in a lead-poisoned child’s home and ordered the building owner to remove it by issuing what is known as a Commissioner’s Order to Abate (COTA). HPD was then required by LL1 to attempt lead paint inspections in those buildings if the owner did not produce, or produced inadequate, records of such inspections. But the vast majority of DOHMH data on children’s elevated blood lead levels—hundreds of thousands of test results—that the City could have used to identify and investigate possible lead hazards at thousands of residences was not so used. Instead, HPD’s lead inspections were largely driven by complaints – most often made via 311. As a result, HPD missed thousands of buildings where DOHMH data showed that lead-exposed children lived.

Lead Exposure Hotspots Found Across the City

Examination of DOHMH’s Childhood Blood Lead Registry yields a wealth of information about the locations of lead poisoning. The Comptroller’s Office found that 26,027 individual children with elevated blood lead levels (above 5 mcg/dL) listed in DOHMH’s records lived within 19,919 buildings throughout the City.

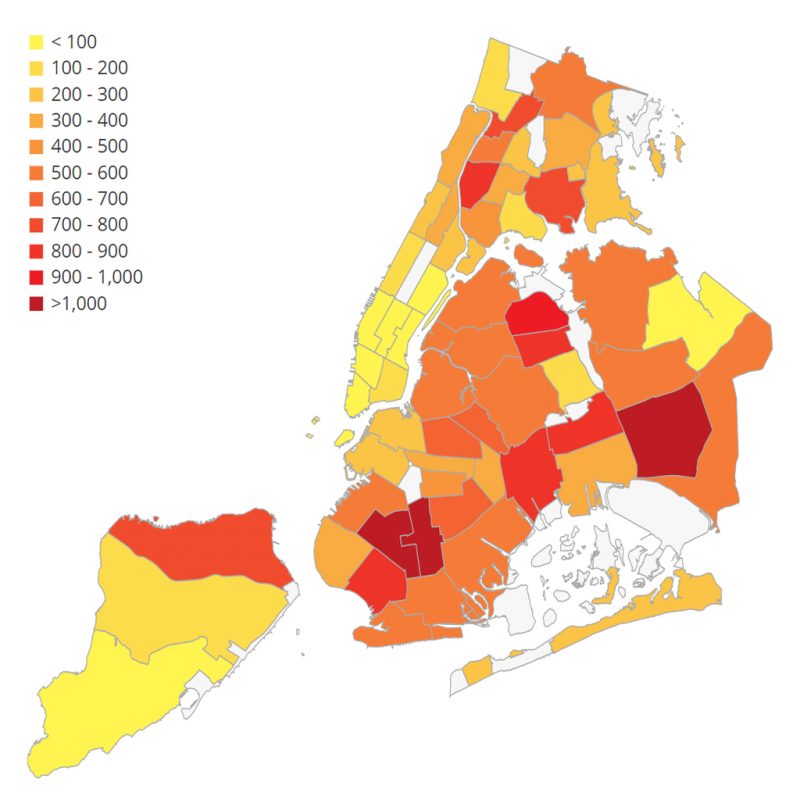

When looking at childhood exposure to lead throughout New York City, the highest proportion of cases cluster in the outer boroughs, particularly in neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Queens. The following map and table show, by Community District, where children who suffered from elevated blood lead levels resided.

Table 1: Top 15 Community Districts with the Highest Numbers of Children with Elevated Blood Levels

| Community District | Total Number of Children |

| Flatbush and Midwood | 1,360 |

| Borough Park | 1,339 |

| Jamaica and Hollis | 1,092 |

| Jackson Heights | 954 |

| Bensonhurst | 829 |

| Elmhurst and Corona | 827 |

| Kew Gardens and Woodhaven | 820 |

| East New York and Starrett City | 815 |

| Highbridge and Concourse | 812 |

| Parkchester and Soundview | 792 |

| St. George and Stapleton | 769 |

| Kingsbridge Heights and Bedford | 727 |

| Bushwick | 692 |

| East Flatbush | 678 |

| Bedford Stuyvesant | 671 |

Map 2: Children with Elevated Blood Levels by Community District

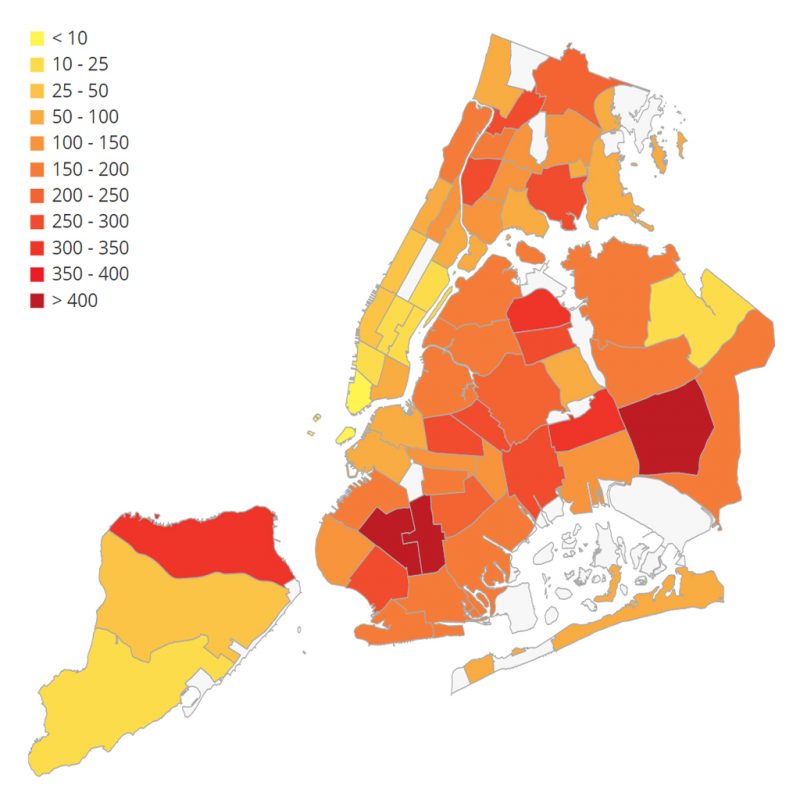

Just as lead exposure is concentrated in certain communities, instances of elevated blood levels in children cluster in certain buildings. In all, 1,561 buildings within New York City were listed as the home addresses for three or more children whose blood test results showed elevated lead levels between January 1, 2013 and October 10, 2018. The following map shows the relative concentrations of buildings that were home to two or more lead-exposed children throughout the City.

Map 3: Buildings that Were Home to Two or More Children with Elevated Blood Lead Levels

In some cases, buildings appear with concerning frequency in testing records. One Brooklyn apartment building was home to as many as 17 individual children who were diagnosed as having elevated blood lead levels. Looking only at the 50 buildings with the highest numbers of children with elevated blood lead levels, DOHMH records show 547 children whose records listed those buildings as home over the five-plus-year period examined.

Table 2: Distribution of Individual Children with Lead Exposure across New York City Buildings[v]

In hundreds of buildings, children’s blood lead levels escalated over time. Indeed, the Comptroller’s Office identified 561 buildings associated with one or more test results of at least 5 mcg/dL but under 15 mcg/dL where later tests exceeded 15mcg/dL. One building saw as many as 22 test records at levels below 15 mcg/dL before returning a result above that threshold. The progression of test results in these buildings could have served as a warning to address lead conditions to prevent future cases of exposure.

Individual apartment units and single family homes were also associated with multiple cases of elevated blood lead levels. As many as 727 units were associated with three or more children with elevated blood lead levels, potentially indicating that the same apartment may have been the root cause of multiple cases of lead exposure. For instance, a single apartment in Queens is associated with lead exposure cases involving seven separate children, with at least one positive test for one or more of these children recorded every year between 2013 and 2016. (The anonymized data obtained from DOHMH does not indicate whether these multiple incidents were associated with different members of a single family or involved multiple families.)

The Comptroller’s investigation revealed that HPD’s enforcement activities have not necessarily aligned with areas of the City experiencing high levels of lead exposure. For instance, as outlined in Table 3, the borough of Manhattan registered 13.4 inspections per documented child-lead-exposure case, versus 4.3 inspections per case in Brooklyn—even though Brooklyn recorded nearly six times the number of total child-lead-exposure cases.

Table 3: Inspections per Documented Child-lead-exposure Case

| Borough | Children with Lead Exposure |

HPD Lead Inspections | Inspections per Child with Lead Exposure |

| Manhattan | 1,810 | 24,313 | 13.4 |

| Bronx | 5,114 | 68,923 | 13.4 |

| Brooklyn | 10,690 | 46,533 | 4.3 |

| Queens | 7,682 | 12,210 | 1.5 |

| Staten Island | 977 | 1,537 | 1.5 |

As the City moves forward with its LeadFreeNYC initiative, it should ensure that its data showing the addresses of lead-exposed children is fully leveraged to target strategic enforcement activity by all relevant City agencies.

Gaps in Testing Resulted in Undercounting NYC’s Lead-Exposed Children

Despite commendable headway in reducing the incidence of elevated blood lead levels, limitations in testing mean that the City is likely to significantly undercount the number of impacted children. As many as half of all children are not adequately tested for lead exposure by health care providers before turning age three, as required by State law.[22] An estimated 30 percent of children receive only one out of the two required lead tests, and 20 percent of New York City children have not been tested at all by age 3 as shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4: Children Tested for Lead Poisoning Turning Age 3 in 2017

| Percentage1 | Number of Children (approximate) | |

| Never tested | 20% | 22,200 |

| Tested only at age 1 | 24% | 26,6002 |

| Tested only at age 2 | 6% | 6,650 |

| Tested at ages 1 and 2 | 50% | 55,400 |

Notes:

1. Percentages obtained from DOHMH 2017 Annual Report.

2. DOHMH provided data showing that 26,606 children turning 3 years of age in 2017 were tested at age 1 but not again at age 2.

In addition, the percentage of children who did not receive a lead test increased substantially in 2011. From 2006 to 2010, the percentage of children under age three who never had a blood lead level test ranged from 7 to 11 percent. However, in 2011, the proportion increased to 17 percent and has ranged from 16 to 20 percent through 2017, as Table 5 shows.

Table 5: Percentages of Children Never Tested By Age 3, 2006-2017

| Lead Blood Level Testing for Children Under 3 | |||

| Year | Tested at Ages 1 and 2 | Tested Only Once | Never Tested |

| 2006 | 41% | 48% | 11% |

| 2007 | 44% | 46% | 10% |

| 2008 | 47% | 45% | 8% |

| 2009 | 50% | 43% | 7% |

| 2010 | 53% | 39% | 8% |

| 2011 | 53% | 30% | 17% |

| 2012 | 53% | 31% | 16% |

| 2013 | 53% | 30% | 17% |

| 2014 | 52% | 30% | 18% |

| 2015 | 51% | 30% | 19% |

| 2016 | 51% | 30% | 19% |

| 2017 | 50% | 30% | 20% |

Given that DOHMH’s investigative response and enforcement cases are based on blood test results, children who are not tested are highly unlikely to receive any City-backed health interventions, including the identification and remediation of the source of the lead. Children may go untested because their healthcare provider fails to order appropriate tests or because children miss medical appointments or do not have access to adequate medical care.[23] Whatever the reason, the data indicates that approximately 55,450 children in New York City were not adequately tested for lead in 2017 in relation to the standard set by State law.[vi]

HPD Failed to Use Key Enforcement Powers under LL1

Although HPD has substantial statutory authority to proactively investigate, audit, and enforce landlords’ compliance with LL1, the agency has largely failed to use it, missing key opportunities to accelerate the elimination of lead hazards in the City’s residential buildings and prevent children’s exposure.[24] LL1 relies primarily on the City’s landlords, overseen by HPD, to continually investigate for and safely address any lead-based paint hazards in their rental apartments “to prevent a child from becoming lead poisoned.” But HPD’s failure to proactively enforce landlords’ compliance left children exposed to the risk of lead poisoning in their own homes. The specific proactive measures that HPD effectively declined to take are discussed below.

HPD Performed No Discretionary Sample Audits Permitted by LL1

LL1 specifically grants HPD proactive authority to perform discretionary sample audits to check landlords’ compliance with their obligation to annually inspect for, identify, notify tenants of, and remediate any lead-based paint hazards in covered buildings. However, the data HPD provided for this investigation shows that in the five-plus-year period between January 1, 2013 and September 12, 2018, HPD issued no violations for a landlord’s failure to make the required annual notifications and inspections. Additionally, HPD officials informed the Comptroller’s Office that the agency had not conducted the discretionary sample audits that conceivably could have uncovered such violations.[25]

LL1 requires owners of multiple dwellings to conduct annual inspections, and to inspect more often if reasonable care so dictates, for peeling paint, chewable surfaces, deteriorated sub surfaces, friction surfaces, and impact surfaces in:

- units in multiple dwellings erected prior to January 1, 1960 where a child under six resides;

- units in multiple dwellings erected on or after January 1, 1960 and before January 1, 1978 where the owner has actual knowledge of the presence of lead-based paint and where a child under six resides; and

- common areas of such multiple dwellings.

In addition, LL1 requires the owner to ascertain whether a child under 6 resides in a dwelling unit by providing notice to the occupant at the signing or renewal of a lease and on an annual basis.

The annual notice and inspection requirement, coupled with the owner’s responsibility to “expeditiously remediate” all known lead-based paint hazards and the underlying defects that contribute to them, were intended to spur continual checks and safe repairs by landlords to keep pace with wear and tear in aging buildings that contain lead-based paint and where children under age 6 reside.[26] LL1 also requires owners to keep a copy of each investigation report, as well as all records relating to any work performed pursuant to the law, for a period of no less than ten years.[27] HPD’s decision to forgo the sample audits that would have monitored and encouraged landlords’ compliance left a potentially powerful tool that the City could have employed to prevent childhood lead poisoning in a state of disuse.

Going forward, HPD will be mandated to perform additional types of audits. Specifically, effective October 11, 2019, in addition to the audits it conducts after DOHMH issues an abatement order, or COTA, HPD will be required to audit the records landlords must keep under LL1 relating to a minimum of 200 buildings each year. These buildings should be “selected from a random sample of buildings based on data on the prevalence of elevated blood lead levels in certain geographic areas identified by [DOHMH].”[28] An owner who fails to produce a required record in response to a demand by HPD will be liable for a class C immediately hazardous violation and a civil penalty of between $1,000 and $5,000.[29]

HPD Did Not Enforce Landlords’ Compliance with Turnover Requirements

Those moments when apartments turn over from one tenant to another are critical opportunities for reducing children’s exposure to lead-based paint hazards in their homes, but HPD did little if anything proactively to spur landlords’ compliance. The turnover requirements that LL1 imposes on landlords include, among other things, the remediation of “all lead-based paint hazards and any underlying defects” and “the removal or permanent covering of all lead-based paint on all friction surfaces on all” doors, door frames, and windows for pre-1960’s multiple dwellings and private homes that are not owner occupied.[30]

Moreover, turnover work must be performed regardless of the ages of former or future occupants.[31] In addition, HPD regulations require owners to certify their compliance with the turnover requirements. For example, “An owner shall certify that he or she has complied…in the notice provided to an occupant upon signing of lease, if any, or upon any agreement to lease, or at the commencement of occupancy if there is no lease.”[32]

Further, building owners who perform any work pursuant to LL1 are required to retain all related records for 10 years after the work’s completion and to make them available to HPD upon the agency’s request.[33] That provision would enable HPD to check whether landlords performed the work LL1 requires at turnover.[34]

The turnover provisions were included in LL1 with the intent that all lead-based paint hazards and conditions contributing to them would be eliminated over time as dwelling unit occupancies change.

However, it appears that HPD has not been enforcing LL1’s turnover requirements or its own related regulations. Our analysis of violation data provided by HPD found that no violations requiring owners to “certify compliance with lead-based paint hazard control requirements during period of unit vacancy” (turnover) were issued between January 1, 2013 and September 12, 2018.[35] Not only were no violations issued for failure to certify, HPD did not issue any violations to property owners for failure to perform required turnover work, nor did HPD compel a property owner to do such work. As a result, the decision was largely left to landlords to follow the City’s turnover rules or not, as they faced no direct consequence in the form of HPD enforcement for failing to do so.

HPD’s refraining from proactive enforcement of LL1’s turnover requirements also neutralized one of the City’s few tools to combat the potential sources of lead poisoning in the homes of children whose families reside as tenants in one- and two-family homes. Those residences are otherwise largely exempt from HPD’s enforcement of LL1, which generally is limited to multiple dwellings containing three or more housing units.

The absence of any turnover violations in a period of nearly six years suggests that HPD was not proactively checking to find out whether landlords performed the required actions, including providing a certification to the incoming new tenant, when an apartment turns over. Moreover, once the new tenant or occupant moves in, HPD apparently has chosen not to look back to determine whether the landlord complied with the turnover requirement between occupancies.

Lack of Oversight for 1- and 2- Family Homes

Analysis of blood lead testing data shows an additional gap in City oversight—namely, the owner-occupied 1- and 2-family homes to which LL1 does not apply. The DOHMH blood test data revealed that a significant percentage of childhood lead exposure cases—as many as 29 percent—involve children residing in these homes. For instance, one Midwood block housed 28 children across 11 buildings with blood lead levels that ranged from 5 to 24 mcg/dL. As a result of the exclusion of 1- and 2-family homes from many of LL1’s provisions, HPD would not have been required over the period covered in this report to respond to lead paint complaints from tenants in 1- and 2-family homes. These homes were also exempt from turnover provisions within LL1 unless the building was exclusively renter occupied.

The City, as part of its LeadFreeNYC initiative, has proposed extending the requirements within LL1 to rental units within 1- and 2-family homes. The City estimates that expanding oversight to this segment of the New York City housing market would “result in an estimated additional 2,500 annual inspections of homes with kids under 6 with potential lead paint.”[36]

NYCHA Responsible for Conducting Its Own Lead-Based Paint Inspections

Some 572 NYCHA buildings—listed by DOHMH as home to 804 lead-exposed children—went uninspected by HPD for lead paint hazards between January 1, 2013 and October 10, 2018. (They are among the 9,671 uninspected buildings discussed above).

HPD does not receive or respond to complaints made by NYCHA residents through 311. Instead, 311 routinely routes those complaints to NYCHA. In a limited number of cases, HPD has been directed by a Housing Court order to take action in responding to a NYCHA complaint. Between January 1, 2017 and June 30, 2018, approximately 295 Housing Court orders required HPD to respond to lead paint complaints within NYCHA buildings according to data HPD provided to the Comptroller’s Office.

Apart from those relatively rare Housing Court cases, LL1 responsibility for lead paint inspection and enforcement in NYCHA developments is left to NYCHA. Consequently, during the period examined by this report, NYCHA was allowed to police its own compliance with LL1.

Recommendations

In January 2019, while this investigation was in progress, the City issued its current plan to create an interagency data-sharing mechanism and to use its data to prioritize proactive lead inspections. The Comptroller supports the City’s LeadFreeNYC plan, including its recognition of the need for inspections in one- and two-family homes, increasing compliance with state law mandating blood lead testing for children, and facilitating better data sharing between DOHMH and HPD. The Comptroller offers a series of additional policy recommendations with the goal of helping to eliminate the scourge of lead exposure in New York City:

1. Proactively Inspect Lead Hotspots

HPD should leverage DOHMH data to proactively inspect buildings associated with children with elevated blood lead levels, buildings with presumed lead paint content in high lead exposure zones, and buildings with known histories of lead-based paint hazards. Critically, HPD inspection activity should be aligned with anonymized information from DOHMH’s Childhood Blood Lead Registry to allow for targeted inspections of the actual buildings associated with past cases of lead exposure.

LeadFreeNYC does charge HPD with creating a “Building Lead Index” that can serve as a roadmap for a more proactive inspection regime. This is a positive step but the Index, as outlined in the LeadFreeNYC report, fails to measure up to the scope of the lead exposure issue. The Index is specified to include only 200 buildings per year, rather than the thousands of buildings associated with a documented case of a child’s lead exposure. Further, while the Index promises to incorporate data “such as prior violations, the age of the building, and whether the building is in an area with higher rates of children with elevated blood lead levels”, the City does not specify whether it will deploy DOHMH data to specifically target inspections. While the City may want to consider a variety of factors in triaging buildings for proactive inspections, focusing on buildings associated with known lead exposure cases offers a more precise method of identifying those with lead paint.

HPD should commit to dispatching qualified inspectors to every building that is flagged on an expanded Index. Inspectors should canvas the building and inform tenants – either directly or by leaving pamphlets – of their right to have their apartments inspected at no cost. In areas where culture or language could perhaps impede an inspector from engaging with tenants, HPD should partner with trusted community based organizations to cultivate trust and gain access to buildings with possible lead hazards.

2. Fully Fund LeadFreeNYC

The City’s LeadFreeNYC program is an ambitious reform of the existing public health status quo. By following through on its many provisions, the City can likely drive the number of elevated blood lead level cases closer to zero. However, for the program to function, the City must provide the participating agencies with the funding they need to carry out their new mandate. For instance, HPD is now tasked with doing much more to police LL1 requirements, enforce the law in one and two family home rentals, and proactively audit. The City estimates the cost of these enforcement actions at $25 million over FY2020 to FY2023.[37] However, the City’s FY2020 Budget only includes an increase of $9 million allocated over that period. If the City is committed to its own plan, the City must fully fund the entire HPD component of LeadFreeNYC.

3. Fully Enforce Key Aspects of Local Law One

HPD must do more to enforce all aspects of LL1. The findings presented in this report show that among other provisions in LL1, HPD has failed to enforce requirements relating to a landlord’s duty to investigate and remediate or abate lead paint when an apartment is about to turn over to a new tenant. Turnover marks a critical moment for advancing the objectives of LL1 and removing the danger of lead paint from all rental apartments.

During any routine inspection, HPD inspectors are required to ascertain whether a child under six years old lives within the apartment.[38] HPD could also determine whether the owner was responsible under LL1 for removing lead paint before the current occupants moved in – that is, whether the family moved in subsequent to LL1 coming into effect in August of 2004. If so, HPD should test for the presence of lead paint in the relevant areas of the apartment, such as door frames, windowsills, and chewable surfaces where a child might become exposed.

If it found that the owner failed to meet LL1’s turnover requirements, HPD should issue the appropriate turnover violations—an action it failed to take even once during the five-year-plus period this investigation covered. HPD should also determine whether any false documents, such as a certification of compliance, were created to make it appear that the turnover requirements were met and refer its findings to the appropriate authority.[39]

HPD should further investigate turnover violations using its authority to audit building records—which owners must keep for 10 years—and to inspect other units in the building. If those efforts reveal that owners falsely certified compliance or failed to certify compliance, additional violations should be written.

To facilitate HPD’s proactive monitoring of landlords’ compliance with turnover requirements, the City should develop a mechanism to either enable HPD to identify, or require owners to report, vacancies in rental units. Since property owners of multiple dwellings and private dwellings that are not owner occupied are required to annually register their buildings with HPD, the annual registration form could be adapted to include a vacancy disclosure item, for example.

HPD must also do more to enforce the mandate in LL1 that owners investigate for the presence of children under 6 and perform and document inspections for lead hazards at least annually (with the written results of that inspection provided to the occupants and kept for ten years for City audit). The City cannot possibly regularly inspect the hundreds of thousands of units in multiple dwellings built before 1960 where children under 6 reside; therefore it is key that the City leverage its enforcement abilities to ensure that owners themselves fulfill this statutory obligation.

4. Ensure All Children Are Tested

The City must do more to boost testing rates among children covered by State law, especially those children at highest risk of exposure. One place to start is a proactive campaign by DOHMH to reach out to parents and children in buildings with known histories of lead contamination to ensure all children under the age of three are tested.

Methodology

The Comptroller’s Office initiated an independent investigation in July 2018 to examine the City’s procedures as prescribed by LL1 for monitoring and mitigating lead-based paint hazards to protect the health of all children. The investigation, which covered the period from January 1, 2013 through October 10, 2018 (unless otherwise specifically stated in the report), focused on the roles and responsibilities of both HPD and DOHMH.

We obtained background information from HPD’s and DOHMH’s websites concerning their respective missions, functions, and responsibilities overall and specifically regarding lead paint hazards. Annual reports that DOHMH and HPD prepared pursuant to LL1 were reviewed, along with information the agencies published about lead and lead safety, lead-safe work (construction) practices, instructions for landlords, and guidelines for medical professionals.

Additional background information was obtained from HPD’s and DOHMH’s sections of the Preliminary Fiscal 2018 Mayor’s Management Report, related prior audits performed by the Comptroller’s Office, and news sources.

We reviewed LL1 and pertinent sections of the NYC Administrative Code and the Rules of the City of New York. Amendments enacted after the period covered by this investigation and any consequent impacts on the findings and recommendations are noted in the report. We reviewed New York State regulations concerning blood testing for children that bear upon DOHMH’s procedures. Additionally, we reviewed information available on the websites of the CDC and the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and from other public websites concerning standards, regulations, and recommendations regarding lead and lead exposure.

We met with officials representing HPD and DOHMH regarding their respective roles, responsibilities, and procedures. The Comptroller’s Office sent separate Requests for Information to each agency and received in response documents and data concerning blood test results, interventions, inspections, violations, complaints, policies, procedures, staffing, and qualifications of agency personnel. All documents and data received were reviewed and analyzed. Necessary clarifications were obtained via follow-up emails and conference calls with agency officials.

Entries in the DOHMH and HPD datasets for the period January 1, 2013 through October 10, 2018 were compared to determine the extent to which HPD performed and attempted to perform inspections for lead-based paint hazards in the buildings where, according to DOHMH’s dataset, children with elevated blood lead levels of 5 mcg/dL or greater resided. We identified buildings under HPD’s jurisdiction using the dataset Buildings Subject to HPD Jurisdiction on the NYC Open Data website. Results were mapped using GIS software.

Some records in the abovementioned datasets were excluded from the comparison because of unverifiable addresses. Specifically, of the 62,453 records in the DOHMH dataset listing reports of children having elevated blood lead levels of 5 mcg/Dl or greater, 3,407 records (5.46%) were excluded. Of the 211,921 records in HPD’s dataset concerning lead inspections, 790 records (0.37%) were excluded, and the remaining records corresponded to 153,516 unique complaint numbers. Of the 66,670 records in HPD’s dataset concerning lead-based paint related violations, 194 records (0.29%) were excluded.

Additional data for analysis was obtained from publicly available sources including NYC Open Data and the NYCHA website.

The Comptroller’s Office obtained testimony from concerned members of the public in all boroughs at a Comptroller’s hearing and a number of roundtables. Additionally, we met with independent advocates and experts. The advocates provided the Comptroller’s Office with various documentation including transcripts of legal cases, interrogatories, and summaries of rules and regulations. We also interviewed Kathryn Garcia, who was appointed Senior Advisor for Citywide Lead Prevention in October 2018, while this investigation was underway, and oversaw the development of the LeadFreeNYC plan.

Appendix: Roles of DOHMH and HPD Under LL1

HPD Must Respond to Lead Complaints and May Audit for Lead Hazards

Upon receipt of a complaint regarding a potential lead paint hazard such as peeling paint, HPD must inspect and, if warranted, test with an x-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzer. If a lead-based paint violation is found during inspection, HPD must serve a notice of violation on the owner.[40] The owner has 21 days after service of the notice to correct the condition. HPD conducts an inspection to verify that the violation has been corrected within 14 days of the correction date. Upon determination that the violation has not been corrected, HPD is required to correct a hazardous lead condition within 45 additional days.[41] Lastly, HPD may perform audits—regardless of whether it has received a complaint—to determine property owners’ compliance with the law, and the agency is required to provide annual reports to the City Council on its enforcement of LL1.[42] (An amendment enacted in 2019 and effective in April 2020 will significantly expand the scope of HPD’s annual reporting requirements to include, among other things, the number of investigations and audits HPD conducts to enforce various obligations that LL1 imposes on landlords.)[43]

DOHMH Must Intervene in Cases of Elevated Blood Lead Levels in Children

During the period covered by this investigation (2013 – 2018), in all cases when a person under age 18 was identified to DOHMH as having a blood lead level (BLL) of 15 mcg/dL or higher, DOHMH was responsible for investigating the source of lead poisoning, ensuring that the conditions creating the elevated blood level were addressed, and providing the child’s family with medical referrals for treatment and testing. (Effective August 2019, LL1 sets a lower threshold for an elevated BLL in a person under age 18 that triggers DOHMH’s investigation—a BLL of 5 mcg/dL or higher).[44] DOHMH also has the authority, under §173.13(d)(2) of the New York City Health Code, to issue a Commissioner’s Order to Abate (COTA), which is an order to a property owner to correct a violation, if lead hazards are found in a child’s residence during DOHMH’s investigation.

HPD’s Actions Following DOHMH’s Lead-Abatement Orders

DOHMH will notify HPD when a COTA is issued for a dwelling unit.[45] If the property owner fails to remedy the hazards as directed by the COTA, HPD is required to correct the hazard.[46] HPD officials informed us that in such cases, HPD will correct the hazard through its Emergency Repair Program by hiring a certified contractor to perform the work. In addition, when it receives a COTA for a dwelling unit from DOHMH, HPD directs the property owner to provide all records regarding tenant notification, annual inspections, and work performed, among other records, for the multiple dwelling.[47] If the owner fails to provide such records, HPD must attempt to inspect all dwelling units where a child under six resides to identify any lead violations.[48] If records are provided, HPD must attempt to inspect any dwelling units where a child under six resides where it determines there may be uncorrected lead-based paint hazards.[49]

HPD officials informed us that if the building owner fails to produce the records that HPD demands as part of its COTA response, the agency issues a notice of violation and has done so in numerous cases. Data provided by HPD confirms that from January 1, 2013 through October 10, 2018, HPD issued 505 such violations.[50] Analysis of related HPD data determined that the agency attempted or completed inspections after issuing those violations at all but 12 of the 505 associated buildings.

References

[i] Some of LL1’s provisions were amended in 2019. Although the amendments were not in effect during the period covered by this investigation, where specific amendments relate to significant issues identified in this investigation, they are noted in this report.

[ii] As used in this report, “lead exposure” is synonymous with an elevated blood lead level of 5 mcg/dL or greater.

[iii] Here, the term “inspection” means either a successful inspection (HPD completed the inspection and closed the complaint) or an unsuccessful inspection (HPD attempted an inspection but could not gain access to the location, or could not complete the inspection, or issued a vacate order) performed by HPD’s Lead Based Paint Inspection Program or Alternative Enforcement Program staff in response to either a complaint or a landlord’s failure to provide requested records— for lead-based paint hazards. For inspections performed in response to complaints, all attempts associated with a unique complaint number at a single location were counted as a single inspection. Also, re-inspections at the same location to determine whether violations were corrected were not included.

[iv] Independent analysis of data provided by DOHMH to the Comptroller’s Office identified 26,027 individual children with home addresses in the city and venous blood lead level test results at or above 5 mcg/dL from January 1, 2013 to October 10, 2018.

[v] The total number of children represented in this chart (27,499) exceeds the number of individual children with elevated blood lead levels at or above 5 mcg/dL (26,027) because some of those children lived in more than one residence in New York City during the nearly six-year period the investigation covered (January 1, 2013 – October 10, 2018).

[vi] A gap in the City’s policy for following up on testing results may have left additional children at risk. The preferred method for obtaining an accurate blood lead level reading according to DOHMH’s Healthy Homes Program Protocol is a venous blood sample, and children’s primary medical care providers are instructed by State law to use it to confirm elevated blood lead levels found through a capillary test, also known as a finger-stick test [10 NYCRR §67-1.2(a)(9)]. During the time period examined, DOHMH did not regard a child’s capillary test as adequate proof of an elevated blood lead level and did not initiate cases based on results from unconfirmed finger-stick tests. Moreover, according to DOHMH officials and the agency’s internal policy and procedure, Lead Poisoning Prevention Program, Integrated Case Coordination and Environmental Investigation for Children (February 2017), DOHMH attempted to facilitate a follow-up venous draw only in cases where the finger-stick result was 15mcg/dL or higher. According to summary data provided by DOHMH, in Fiscal Years 2017 and 2018, 126 children tested with an initial capillary blood lead level test result of 15 mcg/dL or higher. Of those children, 9 had follow-up venous tests performed outside of the recommended timeframe, and 12 did not have a follow-up venous test. For any of those 21 children who would have required interventions, services may have been delayed or never received.

Endnotes

[1] CDC, Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program, https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/information/healthy_homes_lead.htm, accessed July 10, 2019.

[2] American Academy of Pediatrics, Prevention of Childhood Lead Toxicity, 138 Pediatrics (1), (2016), at 5 (“Lead-based paint is the most common, highly concentrated source of lead exposure for children who live in older housing.”); CDC, Preventing Lead Exposure in Young Children: A Housing-Based Approach to Primary Prevention of Lead Poisoning (2004), at 18 (“Although many sources of lead can affect certain individuals and communities, the primary source of childhood lead exposure in the United States is lead paint in older, deteriorating housing.”).

[3] New York City Independent Budget Office, Funding Added for LeadFreeNYC, More to Come?, March 2019, https://a860-gpp.nyc.gov/bitstream/gpp/1415/1/funding-added-for-LeadFreeNYC -more-to-come-fopb-march-2019.pdf

[4] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/National Institutes of Health, NTP Monograph on Health Effects of Low-Level Lead (2012), https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/ohat/lead/final/monographhealtheffectslowlevellead_newissn_508.pdf, accessed March 6, 2019.

[5] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Learn about Lead, https://www.epa.gov/lead/learn-about-lead, accessed March 14, 2019.

[6] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services/National Institutes of Health, NTP Monograph on Health Effects of Low-Level Lead (2012), https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/ohat/lead/final/monographhealtheffectslowlevellead_newissn_508.pdf, accessed March 6, 2019.

[7] Abelsohn, A., Sanborn, M. Lead and Children, Canadian Family Physician, June 2010

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2902938/#b19-0560531; Levin, R, Brown, M., et al., Lead Exposures in U.S. Children, 2008: Implications for Prevention, Environmental Health Perspectives, October 2008, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2569084/

[8] NYC Health, Lead Poisoning, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/health/health-topics/lead-poisoning-prevention.page, accessed August 14, 2019.

[9] NYC Health, Report to the New York City Council on Progress in Preventing Lead Poisoning in New York City, August 30, 2018, https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/lead/lead-rep-cc-annual-18.pdf

[10] LL1 added a new Article 14 to Subchapter 2 of Chapter 2, the Housing Maintenance Code, of Title 27 of the NYC Administrative Code. Most of the provisions covered by this investigation are codified in Article 14; they impose obligations on building owners, occupants, and two City agencies, DOHMH and HPD. LL1 also covers the remediation of lead-based paint hazards in day care facilities that regularly care for seven or more children and that operate more than five hours per week for more than one month of the year. Those provisions, which DOHMH is responsible for administering, are codified at Title 17 (Health) of the NYC Administrative Code, Chapter 9 (§§17-900-913). Pursuant to multiple Local Laws passed this year, on August 12, 2019, §§17-900-913 is repealed and new §§910-924 goes into effect. Among other reforms, the 2019 changes expand the range of facilities falling under the scope of the law to include any facility where day care services are provided (without a minimum hours requirement), as well as the exterior of such facilities. (See Local Law 64 of 2019 section 3).

[11] New York City Administrative Code §§27-2056.3, 27-2056.4.

[12] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.5(a).

[13] New York City Administrative Code § 27-2056.4 (“Owners’ responsibility to notify occupants and to investigate”); New York City Administrative Code §§27-2056.3 (“Owners’ responsibility to remediate”), further codified in the Rules of the City of New York at 28 RCNY 11-02 (“Owner’s Responsibility to Remediate”); New York City Administrative Code § 27-2056.8 (Violation in a Dwelling Unit Upon Turnover); New York City Administrative Code § 27-2056.11 (“Work Practices”), further codified at 11-06 (“Safe Work Practices”) and 28 RCNY 11-01 subsections “ii” (defining “Work”) and “jj” (defining “Work area”).

[14] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.14, amended by Local Law 66 of 2019 §§6, 1, amendment effective August 12, 2019.

[15] CDC, Blood Levels in Children Aged 1-5 Years, April 5, 2013, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6213a3.htm, accessed September 18, 2019.

[16] CDC, Recommended Actions Based on Blood Lead Level, https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/advisory/acclpp/actions-blls.htm, accessed September 18, 2019.

[17] CDC, Recommended Actions Based on Blood Lead Level, https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/advisory/acclpp/actions-blls.htm, accessed September 18, 2019.

[18] NYC Health, Lead Poisoning Prevention Program Integrated Case Coordination and Environmental Investigation for Children, February 6, 2017, pp 4-6.

[19] Press release: Mayor de Blasio, Speaker Johnson and NYC Health Department Announce New Measures to Further Reduce Lead Exposure, July 1, 2018, https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/340-18/mayor-de-blasio-speaker-johnson-nyc-health-department-new-measures-further-reduce

[20] NYC Health, Report to the New York City Council on Progress in Preventing Lead Poisoning in New York City, August 30, 2018, https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/lead/lead-rep-cc-annual-18.pdf

[21] Mayor de Blasio Announces LeadFreeNYC, a Comprehensive Plan to End Childhood Lead Exposure, January 28, 2019, https://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/061-19/mayor-de-blasio-LeadFreeNYC–comprehensive-plan-end-childhood-lead-exposure#/0, accessed August 14, 2019.

[22] NYS Regulations for Lead Poisoning Prevention and Control – NYCRR Title X, Part 67, 67-1.2 (a) (3).

[23] Schneyer, J, Pell, M., Millions of American children missing early lead tests, Reuters finds, June 9, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/lead-poisoning-testing-gaps/

[24] NYC Administrative Code Section 27-2092 gives HPD broad and substantial investigative power to enforce the Housing Maintenance Code, including LL1. It states, “For the purpose of enforcing the provisions of this code . . . the department shall have power to conduct inspections, to hold public or private hearings, to subpoena witnesses, administer oaths and take testimony, and compel the production of books, papers, records and documents.” Further, HPD has promulgated regulations to carry out its responsibilities under LL1, which, among other things, give the agency authority to “undertake any inspection or enforcement action authorized by law where an owner refuses or fails to produce any of the records required to be kept pursuant to article 14 of the housing maintenance code [where much of LL1 is codified], these rules, and other applicable law.” [28 RCNY 11-11(b)].

[25] These findings are confirmed by independent analysis of HPD violation data. Violation code number 619 directs a landlord to “correct failure to notify occupants and to investigate lead-based paint hazards.” HPD issued no code number 619 violations between January 1, 2013 and September 12, 2018 – an extremely unlikely scenario had the agency been proactively auditing landlords’ compliance with those specific annual requirements of LL1.

[26] New York City Administrative Code §§27-2056.3, 27-2056.4, 27-2056.2(1), (3)-(6).

[27] New York City Administrative Code §§27-2056.4(f), 27-2056.17(a).

[28] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.17(b), as amended by Local Law 70 of 2019, effective October 11, 2019.

[29] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.17(c), as amended by Local Law 70 of 2019, effective October 11, 2019.

[30] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.8. Under LL1, “lead-based paint hazard” means any condition in a dwelling or dwelling unit that causes exposure to lead from lead-contaminated dust, from lead-based paint that is peeling, or from lead-based paint that is present on chewable surfaces, deteriorated subsurfaces, friction surfaces, or impact surfaces that would result in adverse human health effects. “Chewable surface” under LL1 means a protruding interior window sill in a dwelling unit in a multiple dwelling where a child under age six age resides and which is readily accessible to such child. It also means any other type of interior edge or protrusion in a dwelling unit in a multiple dwelling, such as a rail or stair, where there is evidence that such other edge or protrusion has been chewed or where an occupant has notified the owner that a child under age six who resides in that multiple dwelling has mouthed or chewed such edge or protrusion. New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.2.

[31] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.8.

[32] RCNY §§11-05(d).

[33] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.17(a).

[34] New York City Administrative Code §§27-2056.8, 27-2056.11(a)(3); RCNY §11-05.

[35] HPD assigns violation code number 614 to turnover violations.

[36] Lead Free NYC, A Roadmap to Eliminating Childhood Lead Exposure, January 28, 2019.

[37] New York City Independent Budget Office, Funding Added for LeadFreeNYC, More to Come?, https://a860-gpp.nyc.gov/bitstream/gpp/1415/1/funding-added-for-LeadFreeNYC -more-to-come-fopb-march-2019.pdf

[38] NYC Administrative Code §27-2056.9(a).

[39] RCNY §§11-03(a)(1), 11-05(c),(d), 11-11 (Audit and Inspection by the Department).

[40] NYC Administrative Code §27-2056.9(c).

[41] NYC Administrative Code §27-2115(l)(1) and (l)(3).

[42] NYC Administrative Code §§27-2056.4(h); NYC Administrative Code §27-2056.12 (concerning annual reports).

[43] Local Law 70 of 2019, amending NYC Administrative Code §27-2056.12.

[44] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.14, amended by Local Law 66 of 2019 §§6, 1, amendment effective August 12, 2019.

[45] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.14.

[46] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.14.

[47] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.7(a) and 28 RCNY 11-11(a).

[48] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.7(b).

[49] New York City Administrative Code §27-2056.7(a).

[50] HPD assigns three-digit code numbers to individual types of lead-based paint violations; for example, violation code number 618 denotes a landlord’s failure to produce records HPD demands as a follow-up to a DOHMH COTA. The 618 violation requires the owner to “correct failure to provide to the department within 45 days of demand all records required to be maintained by owner.”