NYC For All: The Housing We Need

Executive Summary

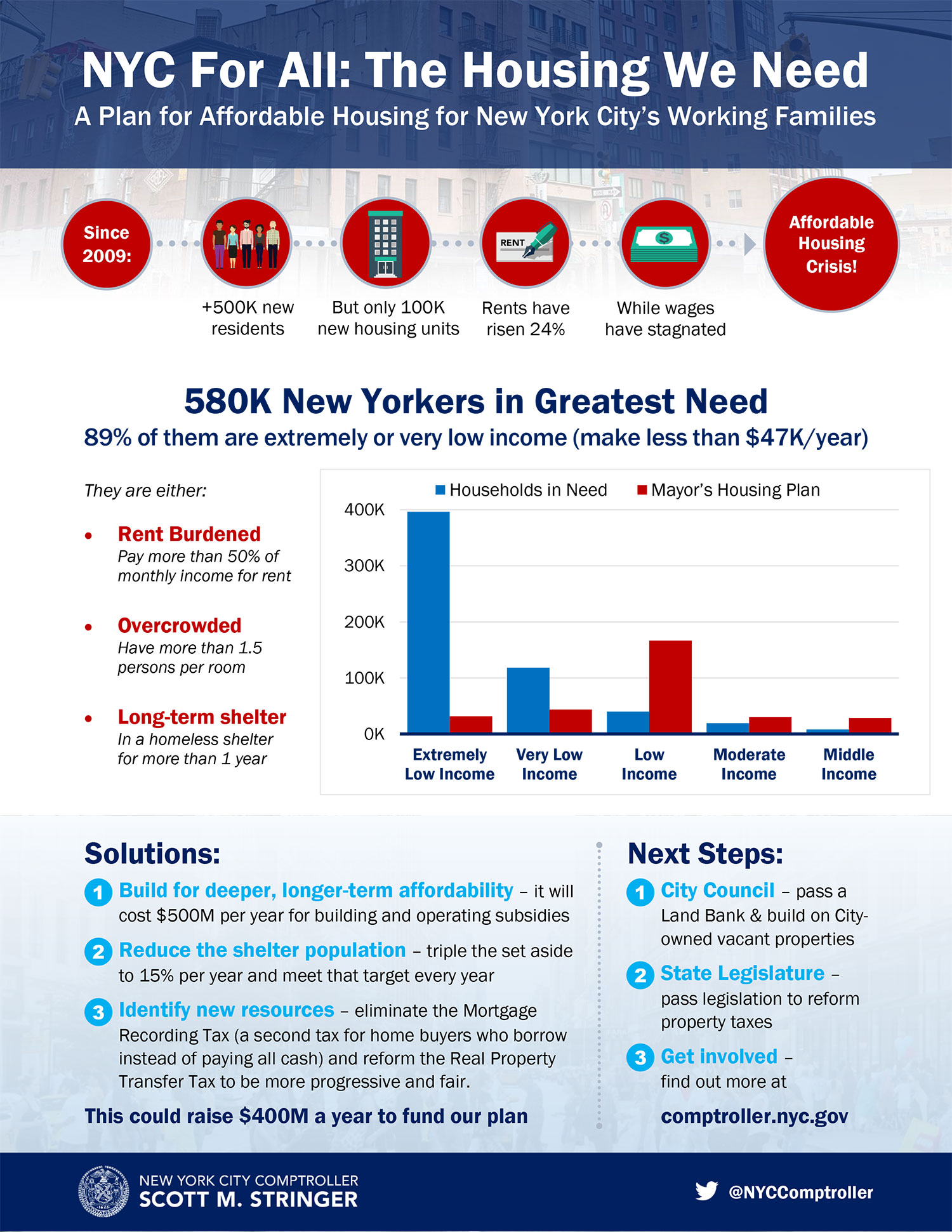

New York City is suffering through an affordable housing crisis, a fact which has been well-documented for years, but has become increasingly acute.

The Last Decade Has Brought Record Growth in Jobs and Residents … On the one hand, the economic recovery of the last near-decade from the recession of 2008-09 has brought new jobs and residents to New York City. Since the end of the Great Recession, city employment has increased by over 800,000 new jobs, to a record 4.5 million jobs, and the City’s unemployment rate is the lowest on record. The City’s population grew by half-a-million residents to 8.6 million – also the highest level on record.

… But Also a Crushing Increase in the Burden of Housing Costs. Yet during that same period, the number of new housing units grew by only about 100,000 – a fraction of what was needed to accommodate this growth. Inevitably, the mismatch in supply and demand has contributed to rents that have risen by over 24 percent on average over the same period, resulting in a massive upward shift in rents and the loss of hundreds of thousands of affordable apartments.

Housing affordability pressure has been most acute for families at the lowest end of the economic spectrum. The earnings for New York City workers in the bottom quartile declined in real terms between 2007 and 2016. In 2005 the average city household with income between $10,000 and $20,000 paid 56.4 percent of its income toward rent. By 2016, those families were forced to sink a full 74 percent of their income into rent, leaving that much less for food, utilities, medical care, and other vital necessities.

Given the ever-increasing burden of meeting the rent, it is not surprising that homelessness has soared and remains stubbornly high, with some 60,000 people sleeping in homeless shelters every night.

This report, by Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, defines the scope of New York City’s existing affordable housing problem through a detailed, data-driven analysis of need. In turn, the report proposes a new strategy for building targeted, truly affordable housing over the long term, and a progressive reform to the taxation of home purchases to finance it.

The Most Pressing Need is Among Some 515,000 of the Lowest-Income Households. This report estimates that some 582,000 New York City households face severe housing pressure due to cost and/or crowding, or have already spent a year or more in a homeless shelter due to the shortage of affordable housing options. Two-thirds of these households have incomes that are defined as “extremely low” ($28,170 per year for a family of three), while another 21 percent are “very low” income ($46,950 per year for a family of three). Altogether, 515,000 extremely and very low-income households live precariously close to homelessness.

The Current Allocation of Affordable Housing Resources Does Not Match the Need. The City’s current goal under the Housing New York 2.0 plan is to build or preserve 300,000 units by 2026. While this housing plan is by far the most ambitious in decades, it does not direct resources to address the actual housing need. Only 25 percent of planned housing starts under Housing New York 2.0 are directed toward the 88 percent of households at the lowest end of the economic spectrum, where the need for affordable housing is measurably most acute.

Failing to target the City’s affordable housing resources toward the greatest need will not “move the needle” in the long run. On the contrary, the City will remain increasingly unaffordable and homelessness will stubbornly persist. To meet this challenge, New York City must direct substantially more resources toward addressing the most pressing need. Specifically:

The City Should Direct Capital Budget Resources Toward More Deeply Affordable Housing. New York City should re-direct a greater portion of its affordable housing investments toward those with the greatest need. Re-allocating the roughly 85,000 new construction units remaining under the Housing New York 2.0 plan proportionally toward those most in need – the extremely and very-low income households identified in our analysis – would require roughly an additional $375 million per year in capital investment for the life of the plan, about a 60 percent increase in the current capital budget for new construction.

In addition, the City Should Create an Operating Subsidy Program to be used to help make apartments affordable for extremely and very low-income households, while ensuring that buildings can remain financially healthy and meet ongoing maintenance needs. In both cases, the per-unit operating subsidy should be scaled so as to meet the basic maintenance and operational needs of the building. Funded at up to $125 million annually, the operating subsidy could contribute to the long-term viability of tens of thousands of deeply-affordable units.

Finally, the City must Triple the Set-aside of New Apartments for Homeless Families from 5 percent to 15 percent, and accelerate the placement of homeless families in permanent housing. To accomplish that, the City should apply the 15 percent target to both new construction and preservation units, and should meet the set-aside target each year of the plan. This would be the most effective approach to a meaningful reduction in the shelter population since Mayor Koch reduced the homeless population by one-third in the 1980s through his housing redevelopment plan.

To provide the necessary funding, the City should Eliminate the Mortgage Recording Tax on Home Purchases and Replace It With A More Progressive Real Property Transfer Tax. To finance this investment in more deeply affordable housing, this report outlines a proposal to replace the City’s regressive and inequitable Mortgage Recording Tax (MRT) on home purchases with a more progressive Real Property Transfer Tax (RPTT). In effect, working people are taxed twice – once on the purchase price of their home (the RPTT), and again on the value of the mortgage they use to buy a home (the MRT) – while all-cash buyers avoid the MRT and pay just the RPTT. In effect, all-cash buyers pay at a lower rate for a similarly-priced purchase. And these all-cash buyers are generally wealthy: In the second quarter of 2018, 54 percent of Manhattan home purchases were made with all cash, and nearly 80 percent of apartment sales over $5 million were made with cash.

Under this proposal, a reformed RPTT would be applied to all New York City home purchases equally, regardless of the source of funds. Moreover, the current RPTT rates and thresholds are outdated with respect to the prices of New York City homes, having been set at a time when sales of $1 million homes were much rarer events. Purchases of homes over $1 million are currently taxed at 2.825 percent, compared to 1.825 percent on homes of $500,000 to $1 million, and 1.4 percent on homes of less than $500,000.

That range fails to reflect today’s residential real estate marketplace, where multi-million dollar sales are much more common. A more progressive RPTT with a more graduated rate structure could both lessen the burden on home buyers of modest means while increasing New York City tax revenues by up to $400 million annually – all of which could be dedicated to building more affordable housing.

In addition to these proposals, the Comptroller renews his call for the City to Work with Non-profit Developers to Build Permanently Affordable Housing on Vacant, City-owned Lots. The City should take a more aggressive approach to building on the at least 600 vacant lots that the City owns by utilizing a land trust/bank model and partnering with not-for-profits, which could accommodate at least 20,000 units of new construction.

Clearly, New York City is at a crossroads, faced with a choice of increasing investment in affordable housing to accommodate our growing population and economy, or becoming a city where working people can no longer afford to live and work. The choice should be obvious. Without a wholesale change in our approach to addressing the ever more acute crisis of housing affordability, we are imperiling the future of New York City as a place where all of our residents can thrive. To address this crisis, we must take bold, new actions if we are to create a truly just New York City for all our residents and for generations to come.

The Growing Need for Affordable Housing

New York City has come a long way since the dark days of the 1980’s, when poverty and crime hollowed out whole neighborhoods, middle-class families fled to the suburbs, and the city’s population fell by over 10 percent. Today, New York City has fully recovered from the fiscal crisis of the 1970s and its aftermath, and successfully weathered subsequent periods of economic stress. Since the low point of the Great Recession in 2009, city employment has increased by over 800,000 jobs, or nearly 90,000 new jobs per year on average, to an historic high of nearly 4.5 million jobs. Today, the unemployment rate is the lowest on record. The city’s population grew by nearly half a million residents between 2009 and 2017, reaching 8.6 million, its highest ever. As the Department of City Planning notes, “[t]he city has not witnessed such a robust pace of growth in over a half-century.”[1]

Partly because of this rebirth, the city’s chronic housing affordability crisis has been made more acute by one key fact: growth in residential units has failed to keep pace with population and job growth. Indeed, while resident employment grew by some 500,000 people since 2009, the city has seen a net increase of only about 100,000 housing units – far fewer than needed to accommodate and sustain its booming economy.[2]

The scarcity of supply relative to population growth has had the inevitable result of pushing rents higher. Between 2009 and 2016, the average rent in New York City increased by 24.5 percent.[3]

The shortage of affordable housing has made the lives of New Yorkers harder in many ways. City dwellers crowd more people into their apartments and pay an ever-increasing share of their income for rent, even though many have seen no increase in their real wages over the decade.[4] This is especially true for extremely-low income and very-low income New Yorkers who work hard every day but continue to struggle to pay the rent (see Income and Affordability sidebar).

Income and Affordability

Income groups are defined for purposes of the City’s affordable housing programs by the City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development, based on federally-determined Area Median Income (AMI) for the New York Area for 2018. Amounts vary by family size; maximum income for a family of three for each band is shown.

| Income Band | Percent of AMI | Family of Three |

| Extremely Low Income | 0-30% | $28,170 |

| Very Low Income | 31-50% | $46,950 |

| Low Income | 51-80% | $75,120 |

| Moderate Income | 81-120% | $112,680 |

| Middle Income | 120-165% | $154,935 |

New York City would all but grind to a halt without these workers, who together fulfill some of the most important jobs within our economy. As shown in Table 1, the New Yorkers in these occupations care for the sick and elderly, staff stores, deliver goods, take care of children, wait on tables, and build homes. Indeed, these New Yorkers face substantial barriers to obtaining affordable housing in today’s New York City, including alarmingly low health insurance enrollment rates, creating the potential for unanticipated economic shocks due to illness. A large number also live in households where no adult is fluent in English, which can significantly inhibit a household’s ability to participate in the broader economy, thus limiting potential housing options.

Table 1: Top 15 Occupations of NYC’s Extremely Low- and Very Low-Income Workers

| Occupation | Number | Median Household Income | Median Rent | Percent with Children in Household | Percent Uninsured | Percent with Limited English |

| Home Health Aides | 66,314 | $27,400 | $1,000 | 49.5% | 6.4% | 28.8% |

| Cashiers | 45,765 | $24,500 | $1,100 | 67.3% | 10.5% | 22.5% |

| Janitors and Building Cleaners | 36,786 | $24,000 | $960 | 36.5% | 17.1% | 25.8% |

| Childcare Workers | 28,967 | $21,450 | $1,000 | 50.3% | 14.8% | 18.4% |

| Retail Salespersons | 28,110 | $21,500 | $1,100 | 41.6% | 14.1% | 19.5% |

| Taxi Drivers and Chauffeurs | 27,011 | $27,500 | $1,200 | 54.8% | 16.8% | 42.1% |

| Maids and Housekeeping Cleaners | 23,587 | $23,900 | $1,100 | 56.2% | 21.5% | 44.4% |

| Construction Laborers | 21,647 | $29,000 | $1,200 | 48.5% | 50.5% | 47.4% |

| Cooks | 21,161 | $25,300 | $1,100 | 46.8% | 31.9% | 40.4% |

| Personal Care Aides | 21,153 | $21,000 | $1,000 | 39.4% | 13.4% | 33.3% |

| Customer Service Representatives | 20,932 | $26,810 | $1,000 | 41.6% | 13.6% | 20.1% |

| Driver/Sales Workers and Truck Drivers | 20,464 | $30,000 | $1,200 | 52.1% | 30.1% | 28.5% |

| Waiters and Waitresses | 19,907 | $29,210 | $1,300 | 48.2% | 22.2% | 32.7% |

| Secretaries and Administrative Assistants | 17,823 | $30,000 | $1,000 | 43.4% | 3.2% | 8.1% |

| Teacher Assistants | 17,362 | $24,000 | $1,100 | 48.4% | 2.5% | 10.9% |

SOURCE: NYC Comptroller’s Office from Census Bureau microdata.

In fact, many working families have already fallen victim to the housing affordability crisis, ending up in homeless shelters. One-third of families with children in shelter have jobs, earning on average less than $20,000 per year, and supporting an average of 1.8 children per family household.[5]

Measuring the Need for Affordable Housing

This report is premised on the idea that a successful housing program must be data-driven and must direct resources where they are most needed. Using Census Bureau data to measure the affordable housing need, the Comptroller’s Office developed an empirical definition of housing need that combines metrics based on rent burden, crowding, and long-term stays in homeless shelters. Each of these factors is discussed in more detail below.

By analyzing the city’s affordable housing landscape in this manner, one can arrive at a true measure of how much affordable housing the City needs to create in order to accommodate our growing population and reduce the scourge of homelessness.

Rent Burden

The most common measure of housing affordability is a household’s rent-to-income ratio. A household is considered “rent burdened” if it spends more than 30 percent of its income on rent, and “severely rent burdened” if it dedicates more than 50 percent of its income to rent.[6]

From 2005 to 2016, rent as a percentage of income increased for New York City tenants regardless of how much money they made, although the challenge was most severe for the lowest-income families, as illustrated in Chart 1. In 2005 the average New York City household with income between $10,000 and $20,000 paid 56.4 percent of its income toward rent (see blue line in Chart 1). By 2016, that figure had increased to more than 74 percent (the red line in Chart 1).

Chart 1: Income Distribution and Rent-to-Income Ratios of NYC Rental Households: 2005 and 2016

SOURCE: NYC Comptroller’s Office from Census Bureau microdata.

Crowding

Crowded housing conditions can also serve as an indicator of housing distress. Studies that have focused on precursors to homelessness have found strong links between crowding and the need to enter shelter.[7] Indeed, crowded living conditions are among the most frequently invoked reasons for homelessness among families entering the City shelter system, following only domestic violence and evictions.

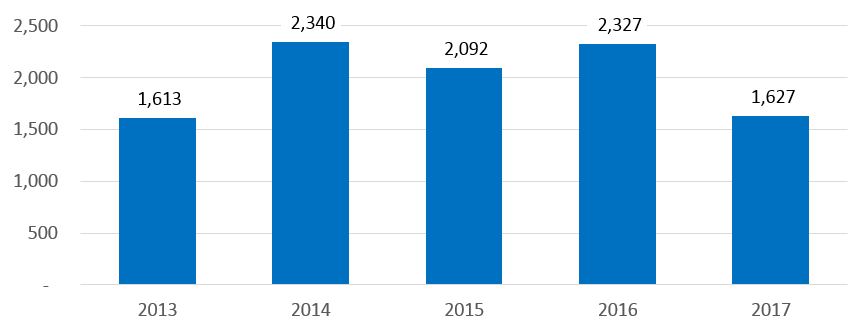

Data provided to the Comptroller’s Office by the Department of Homeless Services indicates that from 2013 through 2017, each month, an average of 167 families with children were found eligible for shelter entry due to crowded living conditions. Chart 2 shows the total number of families with children that entered shelter due to crowding each year for that period.

Chart 2: Families with Children Entering Shelter Due to Crowding, 2013-2017

SOURCE: NYC Department of Homeless Services.

Data from the 2016 American Community Survey indicates that 12.3 percent of the City’s extremely low-income and very low-income households live in crowded conditions, and that 5.3 percent of this cohort lives in severely crowded conditions.[8] New Yorkers classified as extremely low-income or very low-income make up 46.3 percent of the City’s crowded households and 49.4 percent of the City’s severely crowded households.

Shelter as Housing

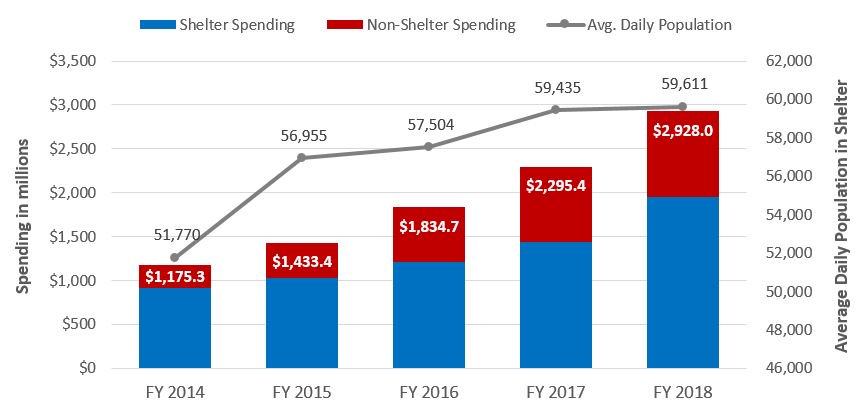

Homelessness has become a seemingly intractable problem in recent years, despite the expenditure of ever-increasing sums to address it. Homeless spending has more than doubled since fiscal year 2014, driven by both rising shelter costs and by spending on programs to help prevent homelessness and find permanent housing for those already in shelters (Chart 3).

Chart 3: Growth in Spending on Homelessness and Average Shelter Population

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller analysis based on Financial Management System data and New York City Department of Homeless Services Daily Census Reports.

Sometimes lost in this discussion is an acknowledgement that City homeless shelters are increasingly serving as long-term housing for New Yorkers, many of whom must balance the rigors of a full-time work schedule with the many requirements imposed on homeless residents by the City. Data provided to the Comptroller’s Office by the Department of Homeless Services illustrates that more than 5,000 families with children have been in the shelter system for more than one year, including more than 2,000 who have been living in a homeless shelter for two years or more – a number that has risen by nearly 15 percent in the year between May 2017 and May 2018.

In short, if the City is ever going to turn the tide on the rising number of homeless people in shelter, it must acknowledge that a shelter bed is not a home, and better align its housing policies with its homeless policies.

The Overall Need

When taken together, the metrics outlined above – the percentage of rent-burdened New Yorkers, those living in overcrowded conditions, and those living long-term in a homeless shelter– begin to sketch the true scope of the City’s affordable housing challenge. Table 2 incorporates the above criteria into an estimate of the number of New York City households in the most urgent need of truly affordable housing.

As shown in Table 2, altogether, more than 572,000 New York City households are severely rent-burdened, meaning that they pay more than 50 percent of their income for rent – including nearly 505,000 households with incomes below 50 percent of Area Median Income. Notably, over 31,000 of these households also live in extremely crowded conditions. Additionally, also shown in Table 2, we estimate that nearly 10,000 households have been in homeless shelters for longer than one year.

Combined, some 582,000 New York City households face severe housing pressure due to cost, crowding, or both, or are simply unable to escape living in a homeless shelter due to the shortage of affordable housing options. Two-thirds of these households have incomes that are less than 30 percent of Area Median Income, or $28,170 per year for a family of three, while another 21 percent live on an income between $28,170 and $46,950 per year for a family of three. Clearly, while housing costs are challenging for many New Yorkers, the need is most acute for those nearly 515,000 households at the lowest end of the income spectrum who are most at risk of homelessness or displacement.

Table 2: Affordable Housing Need: Number of Households by Income

| Need Factor | Income | TOTAL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely Low | Very Low | Low | Moderate | Middle | ||

| Severely Rent Burdened; Not Severely Crowded |

363,126 | 112,343 | 39,236 | 18,444 | 7,752 | 540,901 |

| Severely Rent Burdened and Severely Crowded | 25,545 | 3,886 | 868 | 714 | 143 | 31,156 |

| Long-Term Shelter | ||||||

| – Families with Children | 3,840 | 1,280 | – | – | – | 5,120 |

| – Adult Families | 2,501 | 834 | – | – | – | 3,335 |

| – Single Adults | 1,238 | – | – | – | – | 1,238 |

| TOTAL | 396,250 | 118,343 | 40,104 | 19,158 | 7,895 | 581,750 |

SOURCE: Comptroller’s Office analysis of 2016 American Community Survey and DHS data.

NOTE: See sidebar Income and Affordability on p. 5 for income definitions.

The Housing New York 2.0 Plan

The City’s current affordable housing plan, Housing New York 2.0, which was originally released in 2014 and updated in 2017, sets as a goal the new construction or preservation of 300,000 units of affordable housing by 2026 – the most ambitious numerical goal in modern times. The overall goal includes 180,000 units of affordable housing preserved (that is, rehabbed and refinanced, if necessary, to extend the term of the original regulatory agreement under which the affordability terms were first established), and 120,000 units of new construction. As of June 30, 2018, the plan was over one-third of the way to fulfillment, with 109,767 units completed or underway, including 75,285 units preserved (42 percent of the goal) and 34,482 units newly constructed (29 percent of the goal).[9]

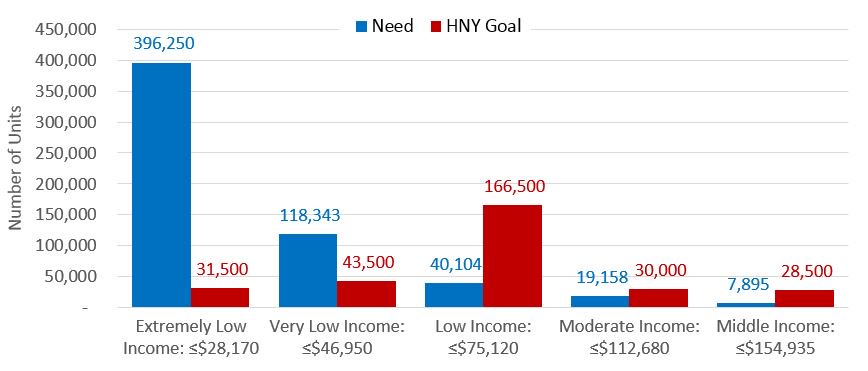

Housing New York 2.0 sets specific goals for units within each income bracket (without distinguishing between preservation or new construction). Under the plan, 166,500 units are for low-income families – those making up to 80 percent of Area Median Income, or $75,120 for a family of three. Another 43,500 units are targeted toward families consider very low-income (making under $46,950 for a family of three), while 31,500 units – 11 percent of the total – are targeted to extremely low-income households (making under $28,170 for a family of 3).

However, as can be seen in Chart 4, the distribution of unit goals by income bands does not correspond to the distribution of the need. As we have shown, the greatest need for affordable housing is among extremely and very low-income households, which comprise 88 percent of the most severely stressed households. The Housing New York 2.0 plan, however, allocates just 25 percent of units for those households. In fact, the plan targets 75 percent of its production to households making more than 50 percent of Area Median Income – but those households represent less than 12 percent of households facing severe rent burdens, crowding, or long-term homelessness.

Chart 4: The Need vs. Housing New York Plan 2.0 Targets

SOURCE: NYC Comptroller’s Office from U.S. Census Bureau and Housing and Vacancy Survey microdata, NYC Department of Homeless Services; Housing New York 2.0 (https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/hpd/downloads/pdf/about/hny-2.pdf).

In short, there is a mismatch between the Housing New York 2.0 goals and the needs of New Yorkers. The City is failing to build enough homes for those most in need – namely extremely and very low-income New Yorkers who are being crushed by rents and living under the threat of homelessness.

Without addressing the need where it is most acute, the chances of success both in making our city more affordable to all, and to finally reducing the scourge of homelessness, are small. Moreover, expanding the supply of housing affordable to the most severely economically-challenged will benefit those on the next rung up the economic ladder by making more affordable units available to low- and moderate-income households, and so on up the ladder.[10]

Of course, doing so will require greater investment by the City. In the next section, we propose a new strategy to provide a more directed and forceful response to the challenge of creating sufficient affordable housing.

Aligning Resources With the Need

Meeting the challenges laid out above – of providing housing for the most at-risk New Yorkers, reducing homelessness, and beginning to relieve the affordability crisis afflicting our city – will require dramatically changing the mix of affordable housing that we are building or preserving. As the preceding section makes clear, to make real progress toward alleviating the housing affordability crisis, New York City should re-prioritize a greater portion of its affordable housing investments toward those with the greatest need, in particular extremely and very low-income households.

Focus New Construction on the Most Urgent Need

The current Housing New York 2.0 plan calls for the construction of 120,000 new units over the life of the plan, of which over 34,000 were completed or underway as of June 30, 2018. But as has been shown, not enough of those units are targeted toward those at the lowest end of the economic spectrum. Shifting the production goals to better align with actual needs would require new targets by income category, as outlined below in Table 3. These would concentrate the remaining new construction unit targets most heavily toward extremely low-income (66,019, or 77 percent) and very low-income (18,044, or 21 percent) households.

Table 3: Housing New York 2.0 and Need-Driven New Construction Production Targets

| Income Range | HNY Goal | Less: HNY Starts | Remaining HNY Goal | Need-Driven Goal |

| Extremely Low | 12,600 | 6,734 | 5,866 | 66,019 |

| Very Low | 17,400 | 3,914 | 13,486 | 18,044 |

| Low | 66,600 | 19,310 | 47,290 | – |

| Moderate | 12,000 | 2,082 | 9,918 | 1,643 |

| Middle | 11,400 | 2,254 | 9,146 | – |

| TOTAL | 120,000 | 34,294 | 85,706 | 85,706 |

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller analysis.

NOTE: The Housing New York goals by income range are imputed from total (new construction plus preservation) goals. Housing New York unit starts are as of June 30, 2018; excluding 188 “other” (mostly superintendent) units. Where starts to date exceed need-driven analysis (low- and middle-income), we show zero incremental need.

Of course, building for deeper affordability is more costly on a per-unit basis, and making more housing units more affordable will require spending more money on a per-unit basis. Using average per-unit subsidy amounts published by the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) for its new construction Mix and Match program, we estimate that construction of new, extremely low-income units requires a subsidy roughly 70 percent greater than that for low-income units; a very low-income unit requires an approximately 30 percent deeper subsidy.[11]

HPD currently has $2.5 billion budgeted for new construction programs for fiscal years 2019 through 2022, or about $630 million per year on average.[12] Distributing the construction of the remaining 85,706 units to better meet the need would require increasing average annual capital commitments by about 60 percent over the remaining life of the plan – or roughly $370 million per year in additional capital funding.

Utilize Operating Subsidies to Preserve and Deepen Affordability

Ensuring the long-term sustainability of more deeply affordable units will require not just increased development subsidies, but also funds to ensure that buildings are properly maintained and operated over the long haul. In order to lock in this longevity for extremely low and very low-income units, the City should create a new operating subsidy designed to preserve and enhance affordability. An operating subsidy program could be used either as a preservation tool that would help extend affordability for buildings that might otherwise choose to exit one of the City’s affordable housing programs upon expiration, or to help make buildings affordable to extremely and very low-income households.

An operating subsidy program could benefit buildings in multiple ways. Buildings that received City financial assistance when they were developed often suffer from a degree of deferred maintenance that requires a significant infusion of City capital funding if they are to remain affordable for the long-term, in addition to new financing and tax exemptions. Therefore, one use of an operating subsidy program would be to provide funding for ongoing maintenance needs to prevent deterioration of buildings in cases where existing rent rolls and assistance were insufficient to adequately provide for the upkeep of the building. This would allow the building to retain deep affordability without sacrificing maintenance, or requiring more costly interventions later.

In addition, an operating subsidy could also be used as needed to deepen affordability on a long-term basis by providing a “gap-filler” between rents affordable to extremely and very low-income households and operating costs. While construction subsidies are often necessary for development, if a building does not have sufficient operating resources it will result in foregone maintenance and ultimately lead to higher costs down the road. To prevent this, operating subsidies could be dedicated to making up the gap between operating revenues and the level of expenses necessary for adequate maintenance. Moreover, the amount of subsidy required for project development could likely be reduced if an operating subsidy were available to provide adequate ongoing revenues for operation and maintenance.[13]

Triple the Homeless Set-aside

Households with very-low and extremely-low incomes live one emergency away from homelessness. Consequently, developing more housing units for these New Yorkers will have the added benefit of keeping these households out of the City’s shelter system in the first place. However, the City must also address those for whom a homeless shelter has become de facto permanent housing – in particular to the roughly one-third of families in shelter with adults who work.[14] In conjunction with an increase in production of units affordable to the most economically disadvantaged, therefore, the City should set aside 15 percent of all new construction affordable housing units for homeless families and individuals. Moreover, this target should be met not just over the life of the Housing New York plan, but each and every year, in order to truly make progress in reducing the homeless population. It is imperative that the City stop using shelter as a substitute for permanent housing and accelerate the provision of real permanent housing for homeless households.

As noted above, the total shelter population, and the length of time that families are staying in shelter, have both continued to increase, and currently nearly 10,000 homeless families or individuals have lived in a shelter for a year or longer. The Housing New York 2.0 plan anticipates that a total of 15,000 units, or 5 percent of the total goal of 300,000 units, will be set aside for homeless households, primarily in preservation units. At a City Council hearing in November of 2017, however, HPD indicated that they have placed only 1,200 homeless families into affordable housing as part of Housing New York since 2014 – or just a little over 1 percent of units started by that time.[15] HPD anticipated that in actuality no more than a few hundred units per year would be available to homeless families during the remaining years of the Housing New York 2.0 plan.

Going forward, first priority for placement should go to those who have been sheltered for a significant period of time, and to working households in shelter. This would be the most effective approach to a meaningful reduction in the shelter population in decades, and is not without precedent. Mayor Ed Koch created nearly 15,700 units of homeless housing – comprising more than 10 percent of the units in his 10-year plan. Nearly all of these units were immediately available for occupancy by homeless families in shelters, contributing to the significant decreases in homelessness during this time period.[16] This strategy can – and must – be replicated today.

Use Vacant, City-owned Lots to Build Permanently Affordable Housing

As previously advocated for by the Comptroller’s Office in its 2016 report Building an Affordable Future, the City should take a more aggressive approach to building on the vacant lots that it owns, by utilizing a land trust/bank model and partnering with not-for-profits.[17] Community land trusts are non-profit entities that acquire land with the goal of maintaining control in perpetuity for a given use, such as open space or affordable housing. They traditionally differ from land banks in modest but important ways. Community land trusts anticipate holding onto property indefinitely, while land banks traditionally seek to transfer vacant and undeveloped properties to third parties to combat blight and encourage thoughtful development. In addition, while land banks acquire abandoned lands wherever they are located through a broader range of powers, land trusts typically target properties through purchase or donation. Despite these differences, land banks and community land trusts often share a common mission of preserving or creating some public use or benefit such as the creation of affordable housing. This model blends the powers of a land trust and a land bank to create an even stronger mission driven entity. The Comptroller’s Office estimates that the City owns as many as 1,000 vacant lots – many of which have sat unused for decades – which could support the construction of as many as 38,000 units of permanently affordable housing.[18]

This model would ensure permanent affordability by keeping control of the land in the hands of a mission-driven, not-for-profit or government land bank. In addition, by partnering with not-for-profits, the City can further reduce costs by lowering fees that are often collected by for-profit developers. For instance, most of HPD’s programs for new construction allow a developer fee to be up to 15 percent of the improvement costs and 10 percent of acquisition costs for tax credit projects to be paid to developers. This fee is permitted to be paid out in part by the cash flows from the project. While development fees can vary, working with not-for-profits offers the City the best chance of lowering the total fees paid, ensuring that City dollars get the maximum impact possible.

Create a New, Fairer Funding Mechanism

Focusing the City’s affordable housing programs on extremely and very low-income households will require additional resources. To generate those resources, and restore a level of fairness to how residential properties are currently bought and sold, this report proposes a new approach to how New York City taxes residential property sales that could both raise additional funds for affordable housing and make buying a home purchases more affordable for the middle class.

A Fairer Approach to Taxing Home Purchases

Under current law, a buyer who is able to pay all cash for the purchase of a condo in a luxury building is taxed for that purchase at a lower rate than a working family who must borrow to finance the purchase of their home. That is because the City and State both impose not just a Real Property Transfer Tax (RPTT) on the value of the transaction, but also a Mortgage Recording Tax (MRT) on the value of mortgages used to finance a purchase. In short, a buyer who purchases a residential housing unit with all cash pays the RPTT, but avoids the MRT, while a family buying their first home by putting 20 percent down and borrowing the rest, pays both. This regressive system should be reformed by repealing the City’s MRT on home purchases, and enacting a more progressive Real Property Transfer Tax (RPTT).

Under the current system, the MRT is imposed by both New York City and New York State, with a combined rate of 2.05 percent for residential mortgages up to $500,000 and 2.175 percent on residential mortgages greater than $500,000.[19] In 2016, mortgage recording taxes imposed on residential mortgages generated $500.7 million in City tax revenue.[20]

While the MRT only applies to real estate purchases made with a mortgage, the RPTT is applied like a sales tax on all New York City real estate transactions, including co-op apartments and all-cash transactions. Both New York City and New York State impose the RPTT. Combined City and State RPTT rates on residential New York City property are currently 1.4 percent on transactions less than $500,000; 1.825 percent on transactions between $500,000 and $1 million; and 2.825 percent on transactions over $1 million. In calendar year 2017, the RPTT generated $755 million in City tax revenue based on $55 billion in residential (co-op, condo, and 1-3 family) real estate transactions in New York City.[21]

As seen in Table 4 below, currently the RPTT and MRT rates on residential property are nominally progressive. More expensive New York City homes and larger residential mortgages are taxed at higher rates.

Table 4: Current Transaction Tax Rates on New York City Residential Property

| RPTT | MRT | |||||

| City | State | Combined | City | State | Combined | |

| Up to $500,000 | 1.000% | 0.400% | 1.400% | 1.500% | 0.550% | 2.050% |

| Over $500,000 up to $1 million |

1.425% | 0.400% | 1.825% | 1.625% | 0.550% | 2.175% |

| Over $1 million | 1.425% | 1.400% | 2.825% | 1.625% | 0.550% | 2.175% |

SOURCE: Office of the City Comptroller.

But, because the MRT applies only to those who must borrow in order to buy a home, the overall impact of transaction taxes on home purchases is in effect regressive. That is the case because in general, the higher the price, the less likely it is that a home purchase is financed with a mortgage. Indeed, all-cash purchases are hardly a rarity in New York City. In the second quarter of 2018, 54 percent of Manhattan home purchases were made with all cash, the highest level since Miller Samuel starting tracking this metric, including 78.9 percent of apartments over $5 million.[22] In contrast, about 63 percent of sales under $500,000 in Manhattan included financing.[23]

These high-wealth all-cash buyers avoid the MRT entirely, but as previously explained, the typical New York City worker who takes out a mortgage to buy their first home cannot do so. In effect, the MRT penalizes the vast majority of first-time home buyers and those of modest and even middle-class incomes. To illustrate:

- The buyer of a $550,000 condo who is able to pay cash is assessed only the RPTT of 1.825 percent, resulting in a tax bill of $10,038.

- Meanwhile, a buyer who puts down 20 percent and takes out a mortgage for the remaining 80 percent for the same apartment, pays the RPTT, plus the MRT of 2.05 percent on the amount borrowed ($440,000). This results in total transaction taxes (RPTT + MRT) for the mortgage purchaser equal to 3.465 percent of the purchase price, or $19,058 – almost twice the rate of the cash buyer for the same home.

The combined impact of RPTT and MRT for different home prices and levels of financing is shown in Table 5. Although home buyers pay RPTT at higher rates on more expensive properties, and borrowers pay MRT at higher rates on larger mortgages, the most important determinant of the total transaction tax burden is the amount of the purchase price that must be financed. The combined transaction tax burden is nominally progressive (from the top to bottom of Table 5) but is in fact regressive the greater the amount financed (from left to right).

Table 5: Cumulative City and State Transaction Tax Rates on New York City Residential Property, by Purchase Price and Percent Financed

| Price | Percent Financed | |||

| 0% | 75% | 80% | 90% | |

| Up to $500,000 | 1.400% | 2.938% | 3.040% | 3.245% |

| Over $500,000 up to $1 million | 1.825% | 3.456% | 3.565% | 3.783% |

| Over $1 million | 2.825% | 4.456% | 4.565% | 4.783% |

SOURCE: Office of the City Comptroller

As seen in Table 5, purchases over $1 million are taxed at 2.825 percent, compared to 1.825 percent on homes of $500,000 to $1 million, and 1.4 percent on homes of less than $500,000. A strong argument can be made, however, that New York City’s current RPTT rates and thresholds are outdated with respect to current prices, in part because they were set at a time when sales of homes over $1 million were still fairly rare occurrences in New York City.[24] That is not the case today: Streeteasy.com currently lists almost 150 New York City homes for sale at prices over $20 million, and over 200 New York City studio apartments for sale for over $1 million.[25] In short, the evolution of housing prices justifies a more progressive rate structure, in line with what many other global cities already do.

Compared to other cities favored by international investors, New York City’s current transaction tax rates on residential property are low. In 2018, Vancouver increased their highest tax rate on transfers of residential property to 20 percent, and Singapore increased their highest transfer tax rate imposed on investors in residential property from 15 percent to 25 percent. The U.K imposes a transfer tax as high as 15 percent on London sales over £1.5 million, and Hong Kong imposes transfer taxes of 15 percent on sales of residential property.[26]

Of course, concerns have been raised that higher effective rates might reduce the overall volume of sales, particularly at the higher end of the market. However, the recent experience of the U.K. suggests that any impact would be minimal. Indeed, although there has been much commentary on the effect of the Stamp Tax in the U.K. (similar to the RPTT), it is difficult to disentangle the impact of that from other broader economic phenomena – notably the British exit from the European Union (or Brexit), which has already led to a slowdown in the hiring of highly-compensated finance professionals from the British capital, and expected job losses.[27] Many observers believe that the Stamp Tax had a “minimal impact” on housing market activity.[28] Similarly, there is little evidence of long-term market impacts from the transaction tax increase in Vancouver.[29]

Under this proposal, the reformed RPTT would be structured in such a way as to protect cash purchasers of more modest means, such as retirees using accumulated home equity. A more graduated, progressive rate structure could also bring the RPTT more in line with current residential real estate prices and raise revenue to be used toward affordable housing development.

In short, as explained in more detail below, replacing the MRT with a restructured RPTT would treat all purchases the same for tax purposes, regardless of the source of funds, and make New York City tax policy fairer and more progressive, while raising hundreds of millions of dollars to finance affordable housing development.

Table 6: Current and Proposed NYC Transaction Taxes Rates on Residential NYC Property

| Current Tax Regime

(RPTT + MRT) |

Proposed

(RPTT only) |

|||

| Purchase Price | Percent Financed | All Transactions | ||

| 0% | 75% | 90% | ||

| Up to $500,000 | 1.400% | 2.938% | 3.245% | 1.000% |

| $500,001 – $1 Million | 1.825% | 3.456% | 3.783% | 2.000% |

| $1 – $2 Million | 2.825% | 4.456% | 4.783% | 3.500% |

| $2 – $5 Million | 2.825% | 4.456% | 4.783% | 5.000% |

| $5 – $10 Million | 2.825% | 4.456% | 4.783% | 6.500% |

| Over $10 Million | 2.825% | 4.456% | 4.783% | 8.000% |

SOURCE: Office of the City Comptroller.

NOTE: Combined City and State rates. The proposed City RPTT rate would be the last column less the combined State RPTT rates (0.40 percent up to $1 million and 1.4 percent over $1 million).

A specific proposal to repeal the residential MRT and replace it with an updated RPTT is outlined in Table 6. Under this model, the rate schedule and thresholds would tax all buyers the same, regardless of whether one is paying in cash or borrowing. This proposal would result in tax liabilities roughly similar to the current rate on all-cash purchases up to $1 million, after which the rate would gradually rise to a top marginal rate of 8 percent for homes over $10 million. This model would result in a lower effective rate on mortgage-financed home purchases up to between $2 million and $5 million (depending upon the amount financed). Unlike the current RPTT, the rates would be applied marginally – that is, the rates would apply to each bracket of the purchase price rather than to the entire purchase price.[30]

The Office of the Comptroller estimates that the rate schedule in Table 6 would increase tax revenues by up to $400 million annually on average. The restructured RPTT revenue increase should be explicitly earmarked to support the City’s increased investment in deeply affordable housing.

Conclusion

This report has documented the growing need for housing for New York City’s lowest income residents. While the city economy has boomed since the Great Recession, adding a record number of jobs and employing more and more New Yorkers, housing production has not kept pace, putting upward pressure on rents and prices. Moreover, many of the new jobs created in the last decade have been low-paying service-economy jobs, from home health aides and cashiers, to waiters and drivers.

The result has been a crisis of housing affordability that has grown increasingly acute. Over 580,000 New York households pay more than 50 percent of their income for rent – nearly 90 percent of whom get by on less than $48,000 annually for a family of three. The population living in homeless shelters has effectively doubled in the last 12 years, from 31,350 in May 2006 to 61,421 in June of 2018, with a monthly tally that has not dropped below 60,000 since November 2015. One out of every six households in shelter has been there for a year or more, even while a third of families in shelter are employed.

To address this crisis, our city needs to take a new approach, better suited to the today’s needs. First and foremost, we must address the housing need where it is most acute – among the very low and extremely low-income families who are most severely burdened by rent – and are therefore the most vulnerable to homelessness. This will require refocusing and expanding the resources dedicated to affordable housing to deepen the affordability of units produced under the current Housing New York 2.0 plan. As things stand, the production goals under HNY for extremely and very low-income units are simply insufficient to make meaningful inroads, given the scale and depth of the need.

Second, to help preserve deeply affordable housing and stem the loss of affordable units, the City should create an operating subsidy program that would help avoid the deferred maintenance that often leads to expensive interventions to preserve buildings later on, or fill the gap between what is needed for sustainable maintenance and operations in more deeply affordable projects.

And finally, we must recognize that the homelessness crisis in our city is above all an affordability crisis. Solving it requires tripling the current target for units available to homeless families, expanding the target to include both new construction and preservation units – and meeting that target every year.

The resources needed to address the growing need for more affordable housing could be provided by a simple reform of the existing tax regime for property transactions, increasing fairness and progressivity, promoting middle-class homeownership, and raising hundreds of millions of dollars annually for affordable housing. These steps should be combined with a more aggressive use of available but vacant City-owned land, and embedded in a fairer, more community-based long-term comprehensive planning process.

These are bold proposals, but it is clear that continuing on the present path is simply not enough to meet the growing need. We must take bold new actions if we are to create a truly just New York City for all our citizens and generations to come.

Acknowledgements

The Comptroller wishes to thank Brian Cook, Assistant Comptroller for Economic Development, and Andrew McWilliam, Senior Research Economist in the Bureau of Budget, for their primary authorship of this report, along with Preston Niblack, Deputy Comptroller for Budget, and David Saltonstall, Assistant Comptroller for Policy. Additional research was provided by Stephen Corson, Senior Research Analyst, and Jacob Bogitsh, Economic Development Policy Analyst. Zachary Steinberg, Deputy Director for Policy, and Carol Kostik, former Deputy Comptroller for Public Finance and her team, as well as several external reviewers, provided constructive comments and suggestions on earlier drafts. The Comptroller also thanks Angela Chen, Senior Web Developer and Graphic Designer and Archer Hutchinson; Frank Giancamilli, Director of Communications; Ilana Maier, Press Secretary; and Tian Weinberg, Press Officer.

[1] New York City Department of Planning, “Current Estimates of New York City’s Population for July 2017,” http://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/data-maps/nyc-population/current-future-populations.page

[2] Comptroller’s Office estimate based on multiple sources, including the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey and New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey, and New York City Department of Finance property tax rolls.

[3] Office of the Comptroller calculation based on the U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey.

[4] Households in roughly the lower one-third of the wage distribution saw just a 1.2 percent increase in real average wages between 2009 and 2017. Office of the Comptroller analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (www.bls.gov/cew).

[5] Office of the Comptroller analysis of Department of Homeless Services data for family households in shelter with a child under 18 present, as of January 24, 2017.

[6] The thresholds for rent burden and severe rent burden are established and used by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

[7] Shinn, M. et al. (1998) “Predictors of Homelessness Among Families in New York City: From Shelter Request to Housing Stability”. American Journal of Public Health (1998). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1508577.

[8] The most commonly used definition of crowded housing is a dwelling unit that is occupied by more than one person per room. Severely crowded housing is defined as a dwelling unit that is occupied by more than 1.5 persons per room.

[9] City of New York, “Housing New York,” http://www1.nyc.gov/site/housing/action/by-the-numbers.page

[10] The reverse effect – how an increase in supply at higher prices “filters down” to ease price pressures among lower-priced units – is articulated in Been, V., Ellen, I.G., O’Regan, K.: “Supply Skepticism: Housing Supply and Affordability,” forthcoming in Housing Policy Debate. (http://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/Been%20Ellen%20O%27Regan%20supply_affordability_Oct%2026%20revision.pdf)

[11] New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, “Mixed Income Program: Mix & Match Term Sheet.” https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/hpd/downloads/pdf/developers/term-sheets/mixed-income-mix-match-term-sheet.pdf

[12] Comptroller’s Office analysis of the FY 2019 Executive Capital Commitment Plan. The principal HPD new construction production programs include the Extremely Low and Low Income Affordability (ELLA) program, the Mixed Income Mix and Match program, and the Mixed Middle Income program. Other new construction programs include the OurSpace program for supportive housing for the formerly homeless, and the Small Homes Development (Large Sites), New Infill Homeownership Opportunities, and Neighborhood Construction Programs.

[13] According to HDC’s Maintenance and Operating Expense Standards, a newly constructed building must generate approximately $7,027 per year per unit before taxes and debt service, or approximately $586 per month, to remain healthy and sustainable. This standard, which is based on prevailing wages for building staff, could provide a benchmark for any shortfalls that an operating subsidy could be used to make up. http://www.nychdc.com/content/pdf/Developers/HDC%20New%20Construction%20Expense%20Standards.pdf

[14] According to data provided to the Comptroller’s office by DHS, 4,353 out of 13,000 families with children in shelter reported earned income (33 percent), and 698 out of 2,516 adult families reported earned income (28 percent), as of January 2017.

[15] Committee on General Welfare hearing: “Oversight – HPD’s Coordination with DHS/HRA to Address the Homelessness Crisis,” Hearing Transcript, pp. 105 ff. Available at: http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=3199363&GUID=088AAF62-BC9B-4628-B3EF-CC1F84658976&Options=&Search=

[16] Between March 1987 and July 1990, the total shelter population fell by 37 percent, from 28,737 to 18,144. The average length of stay also declined from 398 days to 132 days during the same period. Coalition for the Homeless, New York City Homeless Municipal Shelter Population, 1983-Present. (http://www.coalitionforthehomeless.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/NYCHomelessShelterPopulation-Worksheet1983-Present_June2018.pdf)

[17]New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, Building an Affordable Future: The Promise of a New York City Land Bank (February 2016) https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/building-an-affordable-future-the-promise-of-a-new-york-city-land-bank/

[18] HPD estimates that there are approximately 600 buildable vacant or underused properties.

[19] The higher rate applies to all commercial mortgages, a portion of which is dedicated to funding the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). That funding source would not be affected by this proposal.

[20] Including mortgage refinancings. Statistical Profile of the New York City Mortgage Recording Tax, Calendar Year 2016, The City of New York Department of Finance, Division of Tax Policy, August 2017.

[21] Statistical Profile of the New York City Real Property Transfer Tax, Calendar Year 2016, The City of New York Department of Finance, Division of Tax Policy, June 2017.

[22] Elliman Report, 2nd Quarter 2018, Manhattan Sales, https://www.elliman.com/pdf/63978c27e625f9367e8bfd8f0e026d01cf805609.

[23] Stefanos Chen, “Manhattan Buyers’ Market Widens,” The New York Times (Oct. 1, 2018) (https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/01/realestate/manhattan-buyers-market-widens.html)

[24] The current rate structure was set in 1989.

[25] https://streeteasy.com, accessed March 27, 2018.

[26] Vancouver: http://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/taxes/property-taxes/property-transfer-tax/understand/additional-property-transfer-tax; London: https://www.gov.uk/stamp-duty-land-tax/residential-property-rates; Singapore: https://www.iras.gov.sg/IRASHome/Other-Taxes/Stamp-Duty-for-Property/Working-out-your-Stamp-Duty/Buying-or-Acquiring-Property/What-is-the-Duty-that-I-Need-to-Pay-as-a-Buyer-or-Transferee-of-Residential-Property/Additional-Buyer-s-Stamp-Duty–ABSD-/; Hong Kong: https://www.gov.hk/en/residents/taxes/stamp/stamp_duty_rates.htm

[27] Morgan McKinley, “Infographic: London Employment Monitor December 2017,” https://www.morganmckinley.co.uk/article/infographic-london-employment-monitor-december-2017 (accessed January 28, 2018).

[28] RICS, https://www.rics.org/Global/RICS_Housing_Market_Forecast_2018_191217_mt.pdf (accessed January 28, 2018).

[29] “Issue 18-09: Price of New Housing,” https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/data/statistics/infoline/infoline-2018/18-09-price-new-housing.

[30] Currently, the sale of a New York City home for $999,999 is subject to an RPTT rate of 1.825%, and therefore tax of $18,250. A property selling for $1 million, one dollar more, is subject to an RPTT rate of 2.825% on the entire transaction amount, and therefore incurs tax of $28,250. This “cliff” distorts the home market as buyers and sellers find creative ways to keep the transaction prices on home sales under the $1 million threshold, and thereby avoid the $10,000 penalty. A better system would apply RPTT rate increases only at the margin, as with income tax rates. A lower tax rate would be applied to the first $500,000 of the sales price, a higher rate to the next $500,000, and so on. This would reduce the market distortions imposed by the current RPTT system.