Executive Summary

In New York City today, most parents with young children are engaged in paid work. Both parents are in the labor force in more than half of families with children under six, with even higher rates of labor force participation among single-parent households.[1] Every day, these New Yorkers entrust other people to care for their children, make sure they are healthy and safe, and build a strong foundation for future learning. For thousands of families in New York City, child care is a basic need, but for many, and for families with low or moderate incomes in particular, the high cost of care creates a serious financial burden and leaves few preferred child care options, if any, without risking access to other essentials like housing, health care, food, and transportation.

New York City has invested in universal pre-kindergarten for four-year-olds and taken steps to direct similar investments to three-year-olds, but solutions for addressing the affordability and availability of infant and toddler care remain urgently needed, as they are across the country. This report, by New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, analyzes the current landscape for infant and toddler child care in New York City and makes a series of recommendations aimed at making quality child care more affordable and accessible for families with children under three. Findings outlined in this report include:

- A family’s child care bill can be one of their biggest expenses, if not the biggest. A space in a child care center for an infant in New York City costs over $21,000 per year—more than three times as much as in-state tuition at The City University of New York and exceeding median rent in every borough.

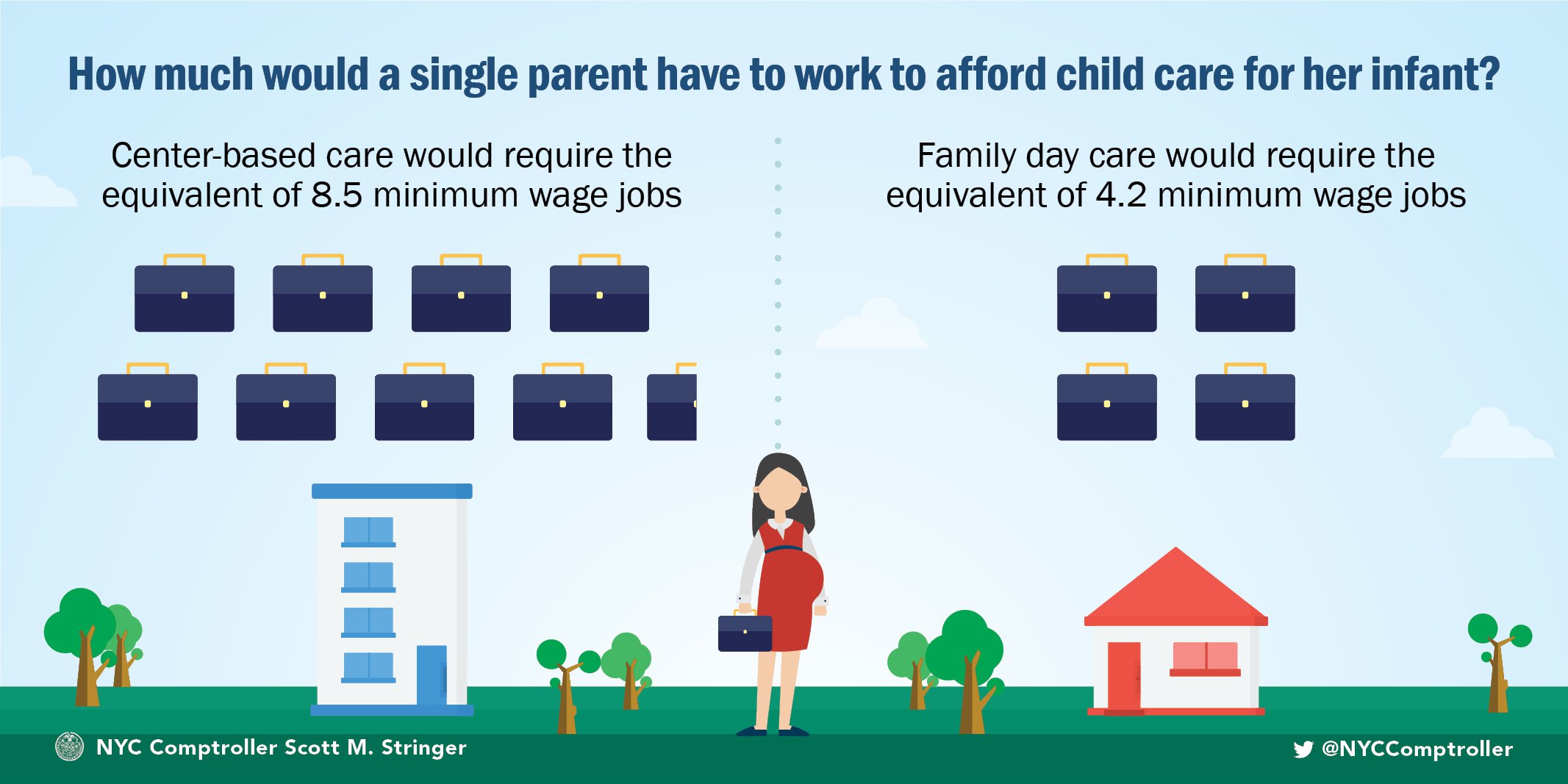

- Center-based care for an infant would consume more than two-thirds (68 percent) of the income of a single parent working full-time at the minimum wage, leaving less than $850 each month for rent, food, utilities, and other necessities. Family day care, care provided in a residence, would eat up one-third of this family’s income.

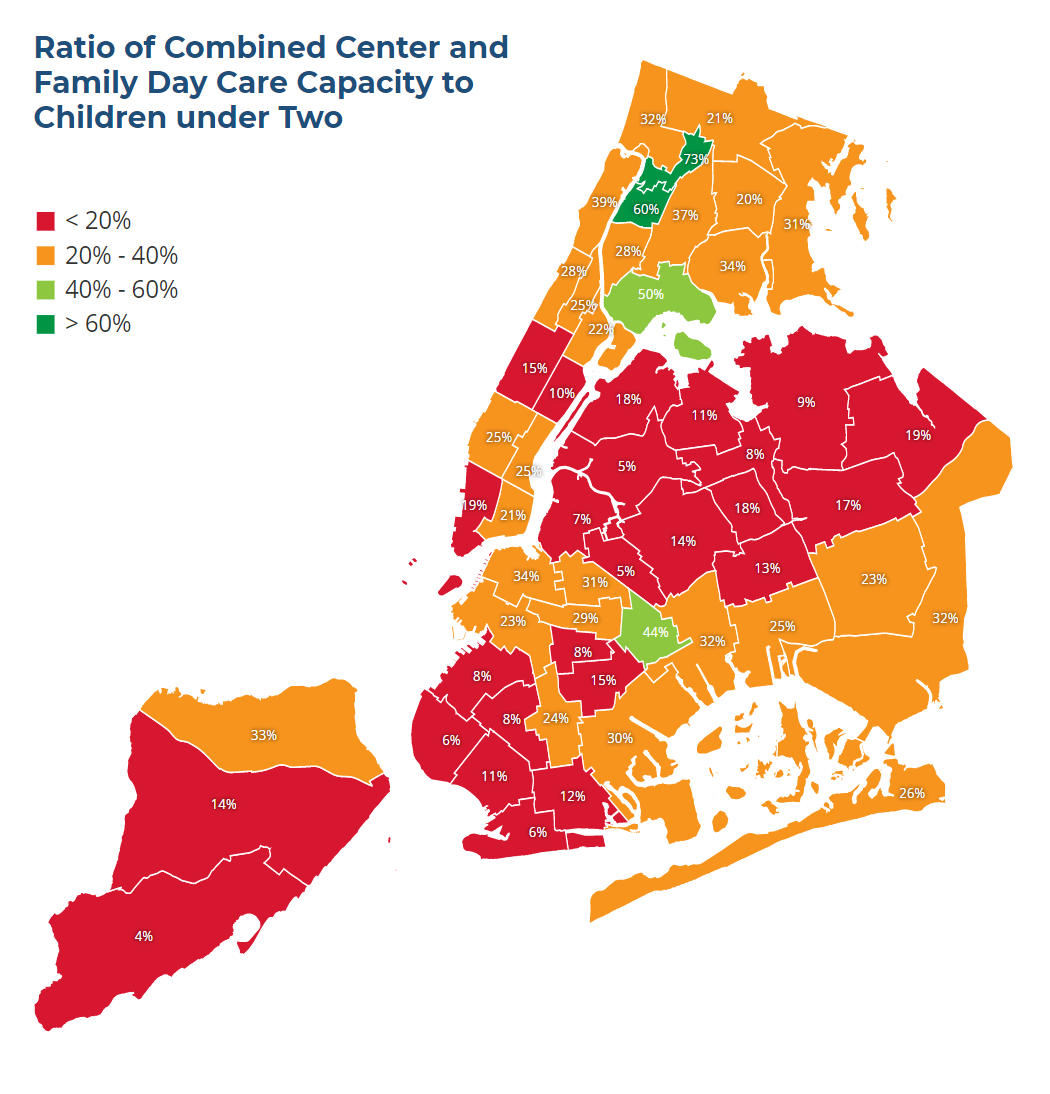

- Child care centers and family day care providers currently have capacity for only 22 percent of children under two in the city. Child care centers, generally located in higher-income communities, have capacity for only 6 percent of children under two, while family day care providers, concentrated in lower-income neighborhoods, can accommodate another 16 percent of children under two.

- Nearly half of all community districts in the city meet the definition of an infant care desert, neighborhoods with a ratio of child care capacity to children of less than 20 percent. In the ten neighborhoods with the least capacity, among them Tottenville, Great Kills, and Annadale in Staten Island, Bushwick in Brooklyn, and Sunnyside and Woodside in Queens, there are more than 10 times as many infants as there are available child care spaces.

- Child care providers make up an overwhelmingly women-led, low-wage workforce. In New York City, 93 percent of employed child care workers are women, and one in four (25 percent) live in poverty, while more than half (53 percent) have incomes low enough to qualify for a child care subsidy.

- Public funding to help families – and providers – offset the costs of child care is woefully inadequate. About one in seven infants and toddlers in families income-eligible for child care assistance actually receives a subsidy, largely due to lack of funding. While an estimated 45 percent of three- and four-year-olds in the city are in publicly funded care, only 7 percent of all infants and toddlers are.

When families are unable to access affordable child care, parents, children, businesses, and whole communities suffer. Lack of quality child care breeds job instability, harms children’s development, and likely drives families out of the city. Taxpayers contribute relatively little toward infant and toddler care, but existing research suggests they do pay heavily over time for the consequences of not doing so, in the form of increased use of public assistance, remedial education, crime, unemployment, and poor health outcomes. On the other hand, researchers have estimated that society can reap an economic return of over $8 for every $1 spent on high-quality early childhood education.[2] Even cost-benefit studies that have found more modest economic returns show that children’s lifetime gains exceed the cost of the programs.[3]

A mix of federal, state, and City funding exists to help families afford child care in the form of subsidies and tax credits, but the current system reaches only a fraction of eligible low-income families in need and does little to address the financial burden of care for families with moderate incomes. In New York City, families with income up to 200 percent of poverty (about $50,000 for a family of four) are eligible for subsidized child care, but for those families who do utilize assistance, the required copayments can be as high as 17 percent of a family’s income, making the benefit itself unaffordable.

Children’s advocates and economic justice organizers alike have long called for greater attention to be paid to care during a child’s earliest years, and recently, a small number of jurisdictions have responded. In June 2018, San Francisco voters approved a ballot measure that would direct new tax revenue to subsidized child care for young children.[4] And in September 2018, the District of Columbia passed a bill that, if funded, would dramatically expand access to subsidized care to children under three over the next decade.[5] New York City can and should be next.

To address the need today and place New York City on a path toward making child care a truly public good, Comptroller Stringer proposes NYC Under 3, a plan to make child care affordable for New York City families with infants and toddlers. When fully phased in, NYC Under 3 would represent the country’s largest municipal-level expansion of child care assistance for families with children under three. The proposal’s recommendations to address the related goals of child care affordability, accessibility, and quality include:

- Affordability: Lowering families’ contributions toward child care and extending child care assistance to working families with incomes up to 400 percent of poverty (about $100,000 annually for a family of four).

Under the Comptroller’s proposal, families’ contributions toward the cost of care would be based on a sliding scale, and families would pay up to a set portion of their income. Fees would range from zero percent of family income for lower income families, to 8 percent for families up to 200 percent of poverty, and rise to a maximum of 12 percent for families at 400 percent of poverty. When fully phased in and assistance is expanded to families at the upper income limit (about $100,000 annually for a family of four), the proposal is expected to more than triple the number of children in City-supported care, benefiting an estimated 84,000 children, including more than 34,000 children who are not currently in paid care.

New York City families would see their out-of-pocket expenses for child care dramatically decrease. A family of four with one child under three and income at about 200 percent of poverty, or just over $50,000 annually, would pay a maximum of around $4,000 a year for child care, less than half what that same family would pay today, if they had access to assistance.

- Accessibility: Dedicating funding for child care start-up and expansion grants and making a capital commitment of $500 million over five years to support the construction and renovation of child care facilities.

To address child care capacity, the Comptroller’s proposal includes offering start-up and expansion grants to child care providers poised to add seats for infants and toddlers. Grants would be competitive, with priority given to providers in neighborhoods with a significant income-eligible population and limited supply of child care. Additionally, the Comptroller proposes a $500 million capital commitment over five years to build space for infants and toddlers. City-owned sites would be targeted first for development of new child care facilities.

- Quality: Increase payments to child care providers and create a fund to expand access to early childhood education training, professional development, and scholarships.

In year one of the proposal, the Comptroller calls for at least $50 million to increase reimbursement for providers currently serving infants and toddlers, lower family contributions, and fund a cost estimation study, which would determine what reimbursement rates should be to support quality child care and living wages for child care workers. As part of this process, wage standards would be established that link attainment of credentials to pay increases and provide parity with public school teachers with the same qualifications. Funding would be dedicated each year to subsidize the cost of meeting training requirements, expand child care providers’ access to professional development and coaching, and support education scholarships.

The Comptroller’s Office envisions that NYC Under 3 would be phased in over a period of six years, with a larger share of funding going toward efforts to address existing flaws in the system and to build the supply of quality care in the initial years. In year one, total spending would be about $180 million, with about 70 percent of funds dedicated to grants to child care providers, capital debt service, and the fund for training and quality improvement. When fully implemented, the total annual cost is estimated to be roughly $660 million. Given that child care is essential for parents to enter or stay in the workforce, the Comptroller proposes paying for the program with revenue from a modest child care payroll tax on private employers in New York City, which would exempt all businesses with payroll under $2.5 million annually, about 95 percent of firms. The proposed payroll tax would be applied quarterly on a graduating scale.

By targeting support to low- and moderate-income families with infants and toddlers, NYC Under 3 would help stabilize child care for those parents facing the greatest barriers to maintaining that care and enable more families to afford formal child care arrangements for the first time. In addition, families would have more resources to meet other basic needs, build savings, and pursue education and job opportunities, which would in turn foster greater economic stability. Indeed, based on the expected increase in child care participation rates, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that maternal employment would increase by about 10 percentage points for eligible families. These newly employed parents would contribute approximately $540 million annually in earnings plus another $78 million in Federal and State Earned Income Tax Credits to the New York City economy.

Access to affordable child care is a fundamental economic justice issue, one that has been ignored for too long. By taking steps to develop an affordable, accessible, and quality infant and toddler care system, one that supports families and dignity for early childhood education and care workers, as outlined in this report, the City can build economic security for families, a more sustainable workforce, and an even stronger foundation for its youngest children—outcomes that ultimately benefit all New Yorkers.

Affordability, Availability, and Quality of Child Care

In today’s economy, the majority of parents are engaged in paid work outside the home. In New York City, both parents are working in more than half (55 percent) of married-couple families with children, while 70 percent of single mothers and 82 percent of single fathers are employed.[6] A full two-thirds (68 percent) of women with children under six are now in the labor force.[7] For New York City families, access to child care that is affordable and reliable is a basic need.

At some point in their children’s lives, nearly all parents rely on other people to care for their children, starting shortly after they are born, through early childhood, and into their children’s elementary school years.[8] Their choices of caregivers vary, with some parents enrolling children in formal child care and pre-kindergarten programs, others hiring nannies or au pairs, and still others enlisting the support of relatives, friends, and neighbors to cobble together enough hours of care each week. Many use a combination of all of the above. National data indicate that nearly nine in ten (87.7 percent) children under five whose mothers work are in a regular weekly child care arrangement (compared to 61.3 percent of all children under five), and one in four (26.7 percent) rely on multiple caregivers.[9]

A substantial body of research has established that child care offers the promise of much more than basic supervision. Indeed, a child’s earliest years are the most consequential time in their development, and child care is an opportunity to nurture critical early socialization and cognitive skills. Child care providers are among children’s first teachers. Their labor, which has traditionally been undervalued, not only ensures that New Yorkers can get to work every day but also that the next generation is safe and healthy and equipped for success as they grow. For children in low-income families in particular, access to high-quality child care provides long-term benefits, which extend to their families and communities and accrue over time: improved health and academic outcomes, increased earnings and economic potential as adults, and reductions in later use of costly remedial education and public assistance.[10]

It was with this appreciation for the importance of early childhood education that New York City established Pre-K for All and began offering free, full-day pre-kindergarten to all four-year-olds during the 2015-2016 school year. And in April 2017, Mayor de Blasio announced 3-K for All, a plan to gradually expand universal pre-kindergarten to all three-year-olds in the city.[11] For those families who would have otherwise paid for child care, the expansion of universal pre-kindergarten translated into thousands of dollars in savings annually. But for families with children too young to access these programs and who need child care, the available options remain costly.

Generally, the younger children are, the more expensive paid care is. That is because the regulations associated with providing licensed care for infants and toddlers typically necessitate more initial and ongoing expenses than care for three- and four-year-olds. In addition to the cost of outfitting a space for infants, which requires cribs and changing tables, licensed providers must hire and retain more staff. In New York City, licensed programs must maintain a minimum adult-child ratio of 1:4 or 1:3 for children under one compared to 1:10 for three- and four-year olds, and fewer infants can be cared for in one group or classroom than older children.[12] Due to the expenses associated with infant and toddler care, child care program costs have gone up as the need for paid care has grown. Nationally, the average cost of full-time, center-based infant care now exceeds that of average in-state college tuition.[13] In New York City, it costs parents more than three times as much as full-time in-state tuition at The City University of New York.[14]

Examining Child Care Affordability in New York City

The best available data on child care costs at the local level come from child care market rates published by the New York State Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS) and are used here as a proxy for the cost of infant and toddler care. OCFS conducts market-rate surveys of a sample of child care providers in order to establish the maximum reimbursement rates for subsidized child care in different regions across the state, and the five counties in New York City comprise one grouping.[15] Since 2014, OCFS has established rates at the 69th percentile, which is intended to ensure families who utilize subsidies can afford the tuition of around seven in ten child care programs.[16] The rates used in this report, then, reflect not average costs but what providers are charging for services at the 69th percentile. Importantly, they do not necessarily correspond with or represent what tuition should be to support high-quality services.[17]

The Comptroller’s Office examined the costs of the two common types of regulated child care programs: center-based, where care is provided in a non-residential location, and family day care, where care is provided in a residence. A third common child care option is informal care, which describes care that is also provided in a home but is license-exempt.

| Types of Child Care Arrangements | |

|

Center-based care (child care center)Care is provided in a non-residential location to three or more children under six-years-old. Staff must include an educational director, and teachers generally must have a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education or related studies or a study plan in place to satisfy the teaching qualifications. Alternative qualifications may be applied to staff of programs caring for children under two-years-old.[18] |

|

Family day care (home-based care)Care is provided in a residence to three or more children who are typically between six-weeks and 12-years-old. Per New York State regulations, at least one caregiver must be present for every two children under two-years-old. Family day care providers may care for up to eight children, if no more than six children are less than school age, while group-family day care providers may care for up to 16 children. Group-family day care providers must have a primary caregiver and at least one assistant. Staff must have at least two years of experience caring for children under six or one year of experience and six hours of training or education in early childhood development.[19] |

|

Informal careCare is provided in a private residence, which may be the home of the child in care, for up to two non-relative children. Providers, who are often friends, family, or neighbors of the children in care, are not required to be licensed. However, in order to participate in and accept payments for subsidized care, providers must meet minimum health and safety standards and be enrolled with a designated legally-exempt caregiver agency.[20] |

As of 2018, when the market-rate survey was last conducted, the annual cost of center-based care at the 69th percentile in New York City was $21,112 for infants and $16,380 for toddlers, or $18,746 on average for children under three.[21] This is almost double the annual cost of family day care, which averaged $10,331 for children under three. The difference in costs likely reflects the added overhead to run center-based programs, which are often large commercial properties, serve more children, and generally require more staffing. Family day care providers, on the other hand, often work out of their own homes, so they do not have to pay additional rent; they also tend to not be able to offer as extensive (and expensive) programming.[22]

As Chart 1 shows, at $21,112 a year, center-based infant care would consume more than two-thirds (67.7 percent) of the annual income of a single parent working full-time at the current minimum wage of $15.00 per hour, leaving less than $850 each month for rent, food, utilities, and other necessities. Family day care would eat up one-third of this family’s income, still well beyond what could be considered affordable. While care is more obtainable for families with two minimum-wage incomes, even two parents with earnings equivalent to the median family income in New York City, a little over $60,000 a year, would spend over one-sixth of their combined incomes on center-based child care, underscoring that cost is a barrier for families across income levels.

Chart 1: Ratio of the Cost of Child Care for an Infant to Income

Note: In converting the $15.00 minimum hourly wage to annual earnings, this analysis assumes full-time work of 40 hours per week, 52 weeks per year.

Source: Comptroller’s Office analysis of New York State Office of Children and Family Services, “Child Care Market Rates Advance Notification” (April 29, 2019), https://ocfs.ny.gov/main/policies/external/ocfs_2019/INF/19-OCFS-INF-03.pdf; New York City Department of City Planning, American Community Survey 2016 5-year estimates, https://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/data-maps/nyc-population/american-community-survey.page.

To better understand how unaffordable child care is for families in New York City, it is helpful to consider about how much families should be spending on child care as a proportion of their income. The federal government states that family copayments for the Child Care and Development Fund, the federal child care subsidy program administered by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), should not exceed 7 percent of family income. This is based on historical data showing that, nationally, families’ average child care expenditures as a percentage of average family income have remained relatively constant at 7 percent.[23] Applying updated U.S. Census Bureau data and isolating child care costs for New York yields a slightly higher affordability benchmark for child care expenses of 8 percent of family income.[24]

Applying an affordability benchmark of no more than 8 percent of family income reveals that New York City families would need annual income of $234,325 to afford center-based infant and toddler care and $129,138 to afford family day care for an infant or toddler without assistance (see Table 1). The former figure is more than three times the median income of New York City families with children and more than eight times the median income of families headed by single mothers.[25] Citywide, 225,000 families with children under three, or 91 percent of families with infants and toddlers, have combined incomes under the affordability benchmark of $234,325. The majority—185,000 families, or three in four families with children under three—have incomes less than $129,138.[26]

Table 1: Cost of Care by Type and Child’s Age

| Center-based care | 0 – 1 ½ years old | 1 ½ – 2 years old | 0 – 2 years old | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Annual cost of center-based care | $21,112 | $16,380 | $18,746 |

| Family income if annual cost = 8 percent of income | $263,900 | $204,750 | $234,325 | |

| Child care affordability wage (hourly) | $126.88 | $98.44 | $112.66 | |

| Family day care | 0 – 2 years old | 2 years old | 0 – 2 years old | |

|

Annual cost of family day care | $10,400 | $10,192 | $10,331 |

| Family income if annual cost = 8 percent of income | $130,000 | $127,400 | $129,138 | |

| Child care affordability wage (hourly) | $62.50 | $61.25 | $62.09 | |

Note: Annual cost of center-based care and family day care for “0-2 Years” reflects weighted average of infant and toddler costs.

Put another way, the child care affordability wage—the combined hourly wage a family would need to afford care without spending more than 8 percent of their income on care—is $112.66 for center-based care and $62.09 for family day care.[27] This means a single parent would have to work the equivalent of 8.5 full-time minimum-wage jobs to afford to enroll their infant in a child care center. Affording family day care would require the equivalent of 4.2 full-time minimum-wage jobs.

The child care affordability wage for center-based care of $112.66 exceeds the median hourly wage of the majority of occupational groups in New York City (see Chart 2).[28] While New Yorkers who work in higher-paying industries are more likely to have the resources to afford their preferred child care arrangement, most New Yorkers’ earnings fall well below the affordability benchmark for both center- and home-based care. With median hourly wages under $15 an hour, many child care providers would not be able to afford care for their own children.[29]

Chart 2: “Child Care Affordability” Wage Compared to Median Hourly Wages by Occupation (First Quarter 2018)

Note: Hourly wages were derived from annual wages and assume 40 hours per week, 52 weeks per year. For the Financial Managers category, data reflect mean wage.

Source: New York State Department of Labor, “Occupational Wages for the New York City Region,” https://www.labor.ny.gov/stats/lswage2.asp (accessed November 15, 2018).

Comparing child care to housing costs, typically considered New Yorkers’ largest monthly expense, offers an additional lens through which to view the high cost of care. According to the Care Index, a research collaboration between New America and Care.com, child care costs in the U.S. comprise on average 85 percent of the cost of rent.[30] At an annual cost of $21,112 or $1,759 per month, market-rate center-based care for infants is equal to 125.2 percent of the citywide median rent ($1,405), exceeding the cost of rent in every borough.[31] Home-based infant care is on average just over three-fifths (61.7 percent) the cost of rent, still a significant expense.[32]

Identifying New York City’s Child Care Deserts

Calculating New York City’s child care affordability wage confirms what families of young children already know: infant and toddler care is expensive, costing more than most families can reasonably afford. But the cost of tuition is not the only barrier to accessing care. Licensed child care providers with capacity for the youngest children are also in short supply. The Comptroller’s Office compared center- and home-based capacity for infants under two-years-old to the number of births in 2015 and 2016 and found that child care centers have capacity for only 6 percent of infants citywide; licensed home-based providers can accommodate another 16 percent.[33] Overall, then, there is estimated to be roughly one child care space for every five infants in the city.

It is important to note that a child care space is not needed for every child under three. Some parents would choose to stay home to care for their infant, hire a nanny, or leave their child in the care of a close relative, friend, or neighbor, regardless of the availability of licensed care. However, the undersupply of care in many areas of the city does suggest that families have uneven access to the care that is available.

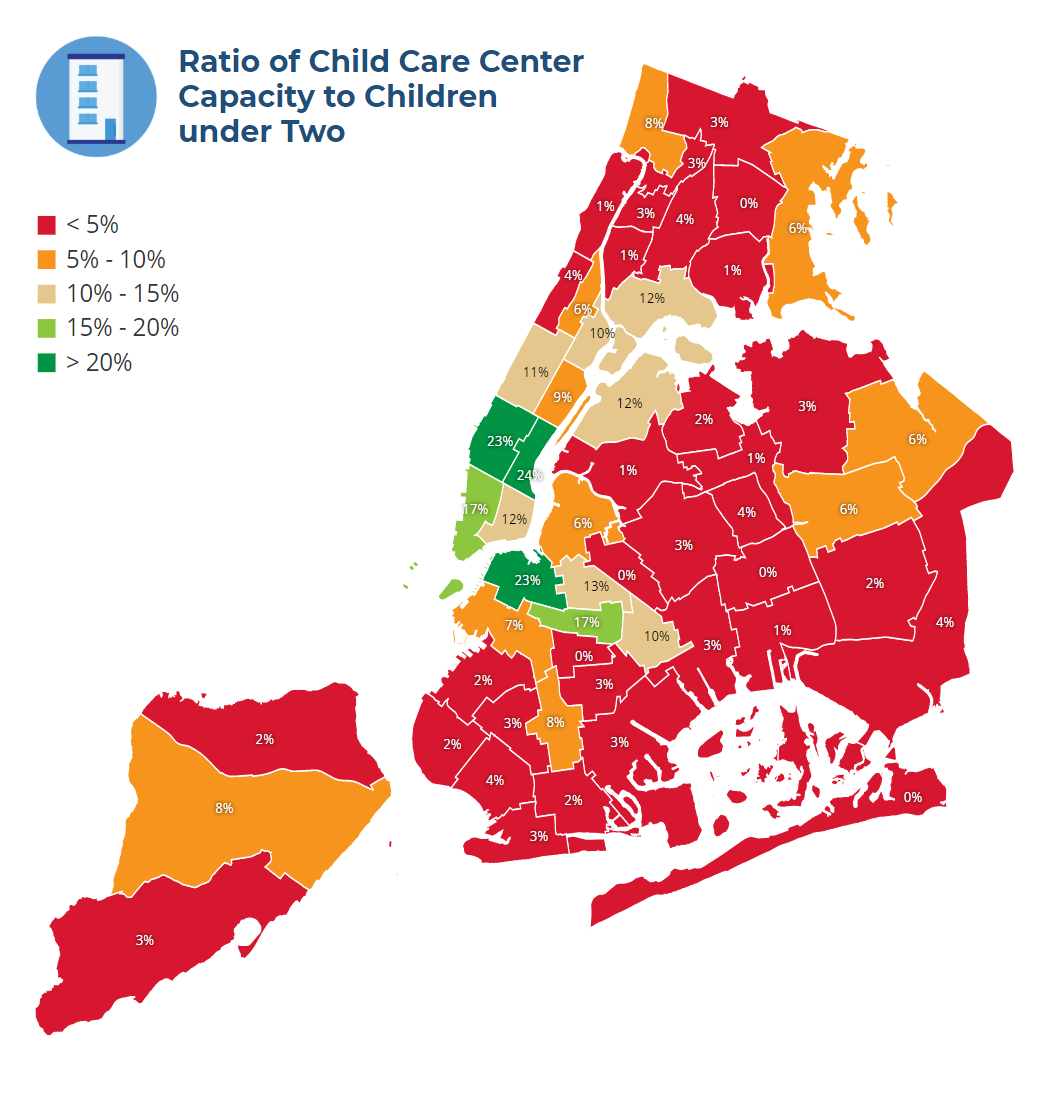

A closer look at center-based infant capacity by neighborhood reveals wide disparities in access, with higher-income communities tending to have greater capacity than lower-income communities. As Map 1 shows, the Murray Hill/Gramercy neighborhood has the highest ratio of center-based infant child care capacity to births (24 percent). The next highest ratio is in Chelsea/Midtown and Brooklyn Heights/Fort Greene, both at 23 percent, followed by Battery Park/Greenwich Village/Soho and Crown Heights North/Prospect Heights at 17 percent. At the other end of the spectrum, there is no center-based capacity for infants in four neighborhoods: Bushwick, Crown Heights South, Pelham Parkway/Morris Park, and Far Rockaway. The ratio is under two percent in 11 neighborhoods. Of the six city neighborhoods with median family income above $100,000, all rank in the top third of neighborhoods for ratio of capacity to births. This likely reflects a growing preference for center-based infant care—for families who can afford it.

Map 1: Ratio of Child Care Center Capacity to Children under Two

HIGHEST RATIO: Murray Hill/Gramercy has the highest ratio of center-based infant child care capacity to births (24 percent), followed by Chelsea/Midtown, Brooklyn Heights/Fort Greene, and Battery Park City/Greenwich Village/Soho.

LOWEST RATIO: There is limited to no center capacity for children under two in Richmond Hill/Woodhaven, Far Rockaway, Pelham Parkway/Morris Park, Crown Heights South/Prospect Lefferts, and Bushwick.

Neighborhood Neighborhood |

Births in 2015 and 2016 | Center-based Child Care Capacity | Ratio of Center-based Capacity to Births |

| Murray Hill, Gramercy & Stuyvesant Town | 2,515 | 611 | 24% |

| Chelsea, Clinton & Midtown Business District | 3,154 | 718 | 23% |

| Brooklyn Heights & Fort Greene | 3,365 | 766 | 23% |

| Battery Park City, Greenwich Village & Soho | 3,760 | 656 | 17% |

| Crown Heights North & Prospect Heights | 2,653 | 442 | 17% |

| Bedford-Stuyvesant | 4,567 | 599 | 13% |

| Chinatown & Lower East Side | 2,667 | 321 | 12% |

| Astoria & Long Island City | 3,956 | 469 | 12% |

| Hunts Point, Longwood & Melrose | 4,944 | 575 | 12% |

| Upper West Side & West Side | 5,006 | 558 | 11% |

| East Harlem | 3,033 | 317 | 10% |

| Brownsville & Ocean Hill | 2,719 | 277 | 10% |

| Upper East Side | 5,073 | 480 | 9% |

| Flatbush & Midwood | 5,236 | 422 | 8% |

| New Springville & South Beach | 2,908 | 232 | 8% |

| Riverdale, Fieldston & Kingsbridge | 2,198 | 166 | 8% |

| Park Slope, Carroll Gardens & Red Hook | 3,434 | 231 | 7% |

| Bayside, Douglaston & Little Neck | 1,428 | 92 | 6% |

| Briarwood, Fresh Meadows & Hillcrest | 3,666 | 232 | 6% |

| Co-op City, Pelham Bay & Schuylerville | 2,047 | 126 | 6% |

| Central Harlem | 3,080 | 178 | 6% |

| Greenpoint & Williamsburg | 7,318 | 414 | 6% |

| Bensonhurst & Bath Beach | 5,445 | 239 | 4% |

| Queens Village, Cambria Heights & Rosedale | 3,321 | 129 | 4% |

| Hamilton Heights, Manhattanville & West Harlem | 2,137 | 79 | 4% |

| Belmont, Crotona Park East & East Tremont | 5,485 | 201 | 4% |

| Forest Hills & Rego Park | 2,856 | 103 | 4% |

| Borough Park, Kensington & Ocean Parkway | 10,991 | 380 | 3% |

| Brighton Beach & Coney Island | 2,604 | 87 | 3% |

| Bedford Park, Fordham North & Norwood | 4,506 | 145 | 3% |

| East Flatbush, Farragut & Rugby | 3,873 | 121 | 3% |

| Morris Heights, Fordham South & Mount Hope | 4,481 | 138 | 3% |

| East New York & Starrett City | 5,365 | 163 | 3% |

| Canarsie & Flatlands | 4,518 | 132 | 3% |

| Wakefield, Williamsbridge & Woodlawn | 3,420 | 99 | 3% |

| Tottenville, Great Kills & Annadale | 4,676 | 133 | 3% |

| Flushing, Murray Hill & Whitestone | 5,852 | 165 | 3% |

| Ridgewood, Glendale & Middle Village | 3,910 | 104 | 3% |

| Sheepshead Bay, Gerritsen Beach & Homecrest | 4,508 | 111 | 2% |

| Port Richmond, Stapleton & Mariners Harbor | 3,014 | 72 | 2% |

| Bay Ridge & Dyker Heights | 3,823 | 83 | 2% |

| Jamaica, Hollis & St. Albans | 5,973 | 128 | 2% |

| Sunset Park & Windsor Terrace | 5,163 | 93 | 2% |

| Jackson Heights & North Corona | 5,090 | 84 | 2% |

| Howard Beach & Ozone Park | 2,580 | 38 | 1% |

| Washington Heights, Inwood & Marble Hill | 4,352 | 64 | 1% |

| Sunnyside & Woodside | 3,380 | 49 | 1% |

| Elmhurst & South Corona | 5,216 | 74 | 1% |

| Castle Hill, Clason Point & Parkchester | 4,765 | 42 | 1% |

| Concourse, Highbridge & Mount Eden | 5,019 | 38 | 1% |

| Richmond Hill & Woodhaven | 3,781 | 16 | 0% |

| Far Rockaway, Breezy Point & Broad Channel | 2,633 | 0 | 0% |

| Pelham Parkway, Morris Park & Laconia | 2,680 | 0 | 0% |

| Crown Heights South, Prospect Lefferts & Wingate | 2,934 | 0 | 0% |

| Bushwick | 2,590 | 0 | 0% |

| Citywide | 219,668 | 12,192 | 6% |

Source: New York City OpenData, “DOHMH Childcare Center Inspections,” https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Health/DOHMH-Childcare-Center-Inspections/dsg6-ifza/data; New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, EpiQuery Natality Module (2015 and 2016), https://a816-healthpsi.nyc.gov/epiquery/Birth/index.html.

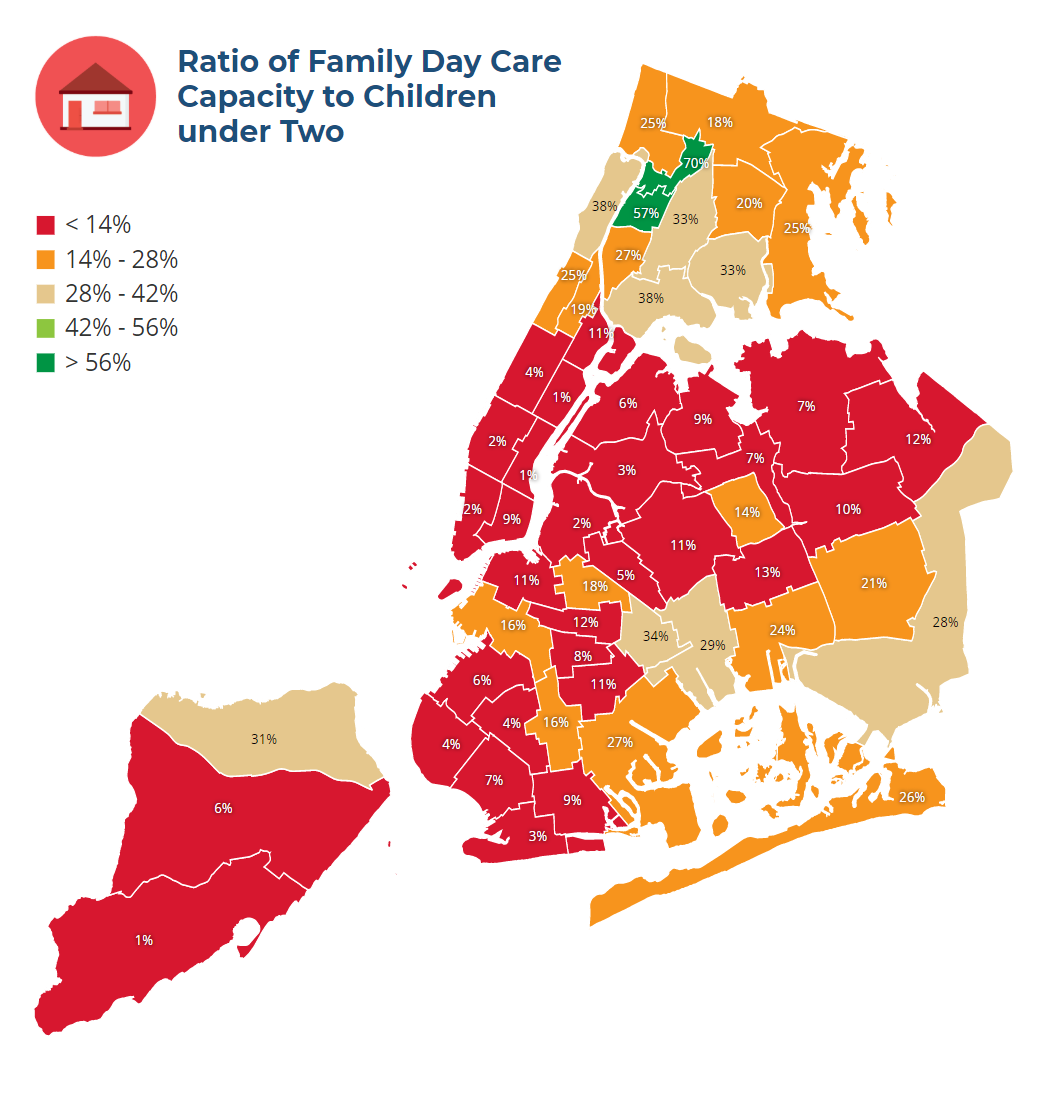

The supply of home-based care also varies substantially by neighborhood; however, providers tend to be concentrated in lower-income communities. Compared to the number of children born in 2015 and 2016, the capacity of home-based providers ranges from one percent in Murray Hill and the Upper East Side, where median household income exceeds $100,000, to 70 percent in Bedford Park/Fordham North and 57 percent in Morris Heights/Fordham South, neighborhoods with median household income of about $33,000 and $24,000, respectively. This disparity reflects the fact that home-based care is a more affordable option on average than center-based care. In addition, some residents in these communities have responded to the demand for affordable child care by launching child care businesses out of their homes.

Map 2: Ratio of Family Day Care Capacity to Children under Two

HIGHEST RATIO: The Bronx neighborhoods of Bedford Park/Fordham North and Morris Heights/Fordham South have the highest ratio of family day care capacity to births at 70 percent and 57 percent, respectively.

LOWEST RATIO: In Murray Hill/Gramercy and the Upper East Side in Manhattan and in Tottenville in Staten Island, family day cares can accommodate only one percent of children under two.

Neighborhood Neighborhood |

Births in 2015 and 2016 | Family Day Care Capacity (estimate of children <2) |

Ratio of Family Day Care Capacity to Births |

| Bedford Park, Fordham North & Norwood | 4,506 | 3,139 | 70% |

| Morris Heights, Fordham South & Mount Hope | 4,481 | 2,555 | 57% |

| Hunts Point, Longwood & Melrose | 4,944 | 1,903 | 38% |

| Washington Heights, Inwood & Marble Hill | 4,352 | 1,647 | 38% |

| Brownsville & Ocean Hill | 2,719 | 932 | 34% |

| Castle Hill, Clason Point & Parkchester | 4,765 | 1,588 | 33% |

| Belmont, Crotona Park East & East Tremont | 5,485 | 1,802 | 33% |

| Port Richmond, Stapleton & Mariners Harbor | 3,014 | 925 | 31% |

| East New York & Starrett City | 5,365 | 1,580 | 29% |

| Queens Village, Cambria Heights & Rosedale | 3,321 | 938 | 28% |

| Canarsie & Flatlands | 4,518 | 1,212 | 27% |

| Concourse, Highbridge & Mount Eden | 5,019 | 1,344 | 27% |

| Far Rockaway, Breezy Point & Broad Channel | 2,633 | 689 | 26% |

| Co-op City, Pelham Bay & Schuylerville | 2,047 | 518 | 25% |

| Riverdale, Fieldston & Kingsbridge | 2,198 | 543 | 25% |

| Hamilton Heights, Manhattanville & West Harlem | 2,137 | 527 | 25% |

| Howard Beach & Ozone Park | 2,580 | 620 | 24% |

| Jamaica, Hollis & St. Albans | 5,973 | 1,263 | 21% |

| Pelham Parkway, Morris Park & Laconia | 2,680 | 528 | 20% |

| Central Harlem | 3,080 | 597 | 19% |

| Wakefield, Williamsbridge & Woodlawn | 3,420 | 618 | 18% |

| Bedford-Stuyvesant | 4,567 | 800 | 18% |

| Park Slope, Carroll Gardens & Red Hook | 3,434 | 557 | 16% |

| Flatbush & Midwood | 5,236 | 830 | 16% |

| Forest Hills & Rego Park | 2,856 | 400 | 14% |

| Richmond Hill & Woodhaven | 3,781 | 492 | 13% |

| Bayside, Douglaston & Little Neck | 1,428 | 177 | 12% |

| Crown Heights North & Prospect Heights | 2,653 | 318 | 12% |

| East Flatbush, Farragut & Rugby | 3,873 | 444 | 11% |

| East Harlem | 3,033 | 344 | 11% |

| Ridgewood, Glendale & Middle Village | 3,910 | 436 | 11% |

| Brooklyn Heights & Fort Greene | 3,365 | 367 | 11% |

| Briarwood, Fresh Meadows & Hillcrest | 3,666 | 381 | 10% |

| Jackson Heights & North Corona | 5,090 | 470 | 9% |

| Sheepshead Bay, Gerritsen Beach & Homecrest | 4,508 | 414 | 9% |

| Chinatown & Lower East Side | 2,667 | 234 | 9% |

| Crown Heights South, Prospect Lefferts & Wingate | 2,934 | 243 | 8% |

| Elmhurst & South Corona | 5,216 | 364 | 7% |

| Bensonhurst & Bath Beach | 5,445 | 365 | 7% |

| Flushing, Murray Hill & Whitestone | 5,852 | 383 | 7% |

| Astoria & Long Island City | 3,956 | 253 | 6% |

| New Springville & South Beach | 2,908 | 183 | 6% |

| Sunset Park & Windsor Terrace | 5,163 | 300 | 6% |

| Bushwick | 2,590 | 120 | 5% |

| Borough Park, Kensington & Ocean Parkway | 10,991 | 468 | 4% |

| Bay Ridge & Dyker Heights | 3,823 | 159 | 4% |

| Upper West Side & West Side | 5,006 | 178 | 4% |

| Sunnyside & Woodside | 3,380 | 118 | 3% |

| Brighton Beach & Coney Island | 2,604 | 80 | 3% |

| Chelsea, Clinton & Midtown Business District | 3,154 | 59 | 2% |

| Greenpoint & Williamsburg | 7,318 | 128 | 2% |

| Battery Park City, Greenwich Village & Soho | 3,760 | 59 | 2% |

| Tottenville, Great Kills & Annadale | 4,676 | 60 | 1% |

| Upper East Side | 5,073 | 51 | 1% |

| Murray Hill, Gramercy & Stuyvesant Town | 2,515 | 21 | 1% |

| Citywide | 219,668 | 35,714 | 16% |

Source: New York State Office of Children and Family Services Child Care Regulated Programs, https://data.ny.gov/Human-Services/Child-Care-Regulated-Programs/cb42-qumz/data; New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, EpiQuery Natality Module (2015 and 2016), https://a816-healthpsi.nyc.gov/epiquery/Birth/index.html.

The Comptroller’s Office combined the number of licensed center-based and home-based child care spaces in each neighborhood to identify “child care deserts,” or communities with limited or no access to care.[34] According to national U.S. Census Bureau data, about one in five children under three are in an organized child care center or family day care.[35] Therefore, the Comptroller’s Office defined child care deserts as any neighborhoods with a ratio of provider capacity to births of less than 20 percent.[36] Applying this definition reveals that 25 neighborhoods, or just under half of all neighborhoods in New York City, are infant care deserts. In 11 communities, seven of which are in Brooklyn, there are more than ten times as many infants as there are available child care spaces. Capacity is most limited in Tottenville, Great Kills, and Annadale in Staten Island, where providers can accommodate only four percent of children under two, and in Bushwick in Brooklyn and Sunnyside and Woodside in Queens, where there are only enough spaces for five percent of children under two.

Based on this analysis and U.S. Census Bureau data, overall, roughly 4 million New Yorkers, including 100,000 children under two, live in an infant care desert.[37] If the ten highest-income neighborhoods in the city are excluded—communities in which families facing a shortage of licensed care are more likely to employ nannies—20 neighborhoods with licensed child care capacity under 20 percent still remain. Roughly 3 million New Yorkers, including about 80,000 children under two, live in these communities.[38]

Map 3: Ratio of Combined Center and Family Day Care Capacity to Children under Two

HIGHEST RATIO: Licensed capacity for infants is highest in Bedford Park/Fordham North and Morris Heights/Fordham South in the Bronx, due to the relatively high proportion of in-home providers in these communities.

LOWEST RATIO: Overall capacity is most limited in Tottenville/Great Kills in Staten Island, Bushwick in Brooklyn, and Sunnyside/Woodside in Queens, where providers can accommodate fewer than five percent of children under two.

Neighborhood Neighborhood |

Births in 2015 and 2016 | Combined Center- and Home-based Capacity | Ratio of Center- and Home-based Capacity to Births |

| Bedford Park, Fordham North & Norwood | 4,506 | 3,284 | 73% |

| Morris Heights, Fordham South & Mount Hope | 4,481 | 2,693 | 60% |

| Hunts Point, Longwood & Melrose | 4,944 | 2,478 | 50% |

| Brownsville & Ocean Hill | 2,719 | 1,209 | 44% |

| Washington Heights, Inwood & Marble Hill | 4,352 | 1,711 | 39% |

| Belmont, Crotona Park East & East Tremont | 5,485 | 2,003 | 37% |

| Castle Hill, Clason Point & Parkchester | 4,765 | 1,630 | 34% |

| Brooklyn Heights & Fort Greene | 3,365 | 1,133 | 34% |

| Port Richmond, Stapleton & Mariners Harbor | 3,014 | 997 | 33% |

| East New York & Starrett City | 5,365 | 1,743 | 32% |

| Riverdale, Fieldston & Kingsbridge | 2,198 | 709 | 32% |

| Queens Village, Cambria Heights & Rosedale | 3,321 | 1,067 | 32% |

| Co-op City, Pelham Bay & Schuylerville | 2,047 | 644 | 31% |

| Bedford-Stuyvesant | 4,567 | 1,399 | 31% |

| Canarsie & Flatlands | 4,518 | 1,344 | 30% |

| Crown Heights North & Prospect Heights | 2,653 | 760 | 29% |

| Hamilton Heights, Manhattanville & West Harlem | 2,137 | 606 | 28% |

| Concourse, Highbridge & Mount Eden | 5,019 | 1,382 | 28% |

| Far Rockaway, Breezy Point & Broad Channel | 2,633 | 689 | 26% |

| Howard Beach & Ozone Park | 2,580 | 658 | 25% |

| Central Harlem | 3,080 | 775 | 25% |

| Murray Hill, Gramercy & Stuyvesant Town | 2,515 | 632 | 25% |

| Chelsea, Clinton & Midtown Business District | 3,154 | 777 | 25% |

| Flatbush & Midwood | 5,236 | 1,252 | 24% |

| Jamaica, Hollis & St. Albans | 5,973 | 1,391 | 23% |

| Park Slope, Carroll Gardens & Red Hook | 3,434 | 788 | 23% |

| East Harlem | 3,033 | 661 | 22% |

| Wakefield, Williamsbridge & Woodlawn | 3,420 | 717 | 21% |

| Chinatown & Lower East Side | 2,667 | 555 | 21% |

| Pelham Parkway, Morris Park & Laconia | 2,680 | 528 | 20% |

| Battery Park City, Greenwich Village & Soho | 3,760 | 715 | 19% |

| Bayside, Douglaston & Little Neck | 1,428 | 269 | 19% |

| Astoria & Long Island City | 3,956 | 722 | 18% |

| Forest Hills & Rego Park | 2,856 | 503 | 18% |

| Briarwood, Fresh Meadows & Hillcrest | 3,666 | 613 | 17% |

| Upper West Side & West Side | 5,006 | 736 | 15% |

| East Flatbush, Farragut & Rugby | 3,873 | 565 | 15% |

| New Springville & South Beach | 2,908 | 415 | 14% |

| Ridgewood, Glendale & Middle Village | 3,910 | 540 | 14% |

| Richmond Hill & Woodhaven | 3,781 | 508 | 13% |

| Sheepshead Bay, Gerritsen Beach & Homecrest | 4,508 | 525 | 12% |

| Bensonhurst & Bath Beach | 5,445 | 604 | 11% |

| Jackson Heights & North Corona | 5,090 | 554 | 11% |

| Upper East Side | 5,073 | 531 | 10% |

| Flushing, Murray Hill & Whitestone | 5,852 | 548 | 9% |

| Elmhurst & South Corona | 5,216 | 438 | 8% |

| Crown Heights South, Prospect Lefferts & Wingate | 2,934 | 243 | 8% |

| Borough Park, Kensington & Ocean Parkway | 10,991 | 848 | 8% |

| Sunset Park & Windsor Terrace | 5,163 | 393 | 8% |

| Greenpoint & Williamsburg | 7,318 | 542 | 7% |

| Brighton Beach & Coney Island | 2,604 | 167 | 6% |

| Bay Ridge & Dyker Heights | 3,823 | 242 | 6% |

| Sunnyside & Woodside | 3,380 | 167 | 5% |

| Bushwick | 2,590 | 120 | 5% |

| Tottenville, Great Kills & Annadale | 4,676 | 193 | 4% |

| Citywide | 219,668 | 47,906 | 22% |

Source: New York City OpenData, “DOHMH Childcare Center Inspections,” https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Health/DOHMH-Childcare-Center-Inspections/dsg6-ifza/data; New York State Office of Children and Family Services Child Care Regulated Programs, https://data.ny.gov/Human-Services/Child-Care-Regulated-Programs/cb42-qumz/data; New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, EpiQuery Natality Module (2015 and 2016), https://a816-healthpsi.nyc.gov/epiquery/Birth/index.html.

While the availability of licensed care shows that families’ options are generally limited, what the data do not and cannot capture are that these options are further shaped and reduced by other factors families weigh when selecting a provider, including access to transportation, a need for culturally responsive care, and proximity to workplaces, among others. Moreover, the Comptroller’s analysis only shows available spaces and not available hours in a day, given data limitations. But families who need access to child care during ‘nontraditional’ hours, such as nights and weekends, have even fewer center- and home-based options and would be more likely to use informal care arrangements as a result.[39] The existence of a child care space does not reflect its relative quality either, as discussed in more detail below.

Assessing Child Care Quality

Unlike with child care affordability and accessibility, little data exist on the overall quality of care in the city, despite the fact that surveys show parents are concerned about finding high-quality early learning environments for their children, and providers are eager to develop higher quality programming.[40] Beyond the State’s and City’s licensing requirements, which outline minimum provider qualifications and training, there is no universally applied standard or rating system. What measures of quality do exist, such as accreditation, serve to indicate certain features of individual programs but do not capture all quality programs in the city. For example, only a small proportion of centers and home-based programs in New York are accredited by two of the main national early childhood education accrediting agencies, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) and the National Association for Family Child Care (NAFCC).[41] However, the process of becoming an accredited program and then maintaining that status requires capacity and resources that many providers simply cannot spare. Indeed, child care is labor-intensive, especially for infants and toddlers, making it an expensive proposition not only for families but also for providers.

Over the last two decades, states have moved to adopt child care Quality Rating and Improvement Systems, or QRIS, in order to better measure quality, help providers meet higher quality standards, and market their programs. Forty-four states, including New York, now have a QRIS, compared to only 16 a decade earlier.[42] As in other states, New York’s QRIS, QUALITYstarsNY, assesses child care quality against a set of best practices in early childhood development, providing programs with a rating of up to five stars. However, QUALITYstarsNY is underdeveloped relative to some other state QRIS due to lack of public funding, and providers are not mandated to participate. As of September 2018, a total of 147 center-based and 67 home-based child care programs in New York City—214 total—were participating in the QRIS, or an estimated 2.4 percent of center and family day care programs in the city.[43] None of the programs’ ratings have been made public.

New York City Providers Participating in QUALITYstarsNY

| Borough |  Center-Based Care Center-Based Care |

Home-Based Care Home-Based Care |

Total |

| Bronx | 22 | 15 | 37 |

| Brooklyn | 64 | 27 | 91 |

| Manhattan | 25 | 6 | 31 |

| Queens | 24 | 3 | 27 |

| Staten Island | 12 | 16 | 28 |

| Citywide | 147 | 67 | 214 |

Source: QUALITYstarsNY, “Who We Serve,” http://qualitystarsny.org/discover-serve.php (data current as of September 2018).

Data related to known components of quality early childhood settings, in particular adequate compensation for providers, suggest that child care workers in New York City are having to overcome significant constraints on quality, not unlike most child care workers across the country. The child care workforce has historically been a low-wage workforce, and this remains the case in New York City. According to a 2017 report by the Restore Opportunity Now campaign, median hourly wages of women working in child care in the private sector are about one-third below the median wages of women in the private sector overall.[44] Analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data shows one in four (25 percent) employed child care workers in the city live in poverty, and more than half (53 percent) have incomes that would qualify them for subsidized child care.[45] These providers are predominantly women (93 percent), and overwhelmingly women of color.[46]

The low compensation among the workforce generally means that opportunities for professional development—those that would improve the quality of care but might also offer a path for career advancement—are unworkable for many child care providers without significant financial assistance. Training and workshops, coaching and mentoring, and credential or degree programs in which providers can develop foundational and specialized knowledge in early childhood development are critical to gaining the most out of children’s earliest years but can cost thousands of dollars. Fortunately, there are a number of organizations in New York City that offer no- or low-cost professional support, and New York State, through OCFS, funds the Educational Incentive Program (EIP), which provides scholarships to eligible child care providers to help offset the cost of approved training and education.[47] The maximum annual EIP scholarship in 2019 is $2,000 for college courses and $1,250 for training toward a Child Development Associate (CDA) Credential. Publicly funded resources for training may be particularly beneficial for home-based providers, who tend to be disconnected from the institutional support that larger centers, or organizations overseeing many centers, may offer.

Disparities in compensation and access to resources like professional development undermine the quality of child care services by reinforcing recruitment and retention problems in certain parts of the system. National data indicate that providers who serve infants and toddlers earn less than counterparts who teach pre-kindergarten children at every level of education, which may be a disincentive to serve young children.[48] In New York City, salary disparities between equally qualified teachers in City-contracted community-based organizations and in New York City public schools have driven staff to leave positions in community-based programs for higher-paying jobs at the Department of Education.[49] Such poor retention and high job turnover is harmful not only to the sustainability of child care programs but also for sustaining quality in early childhood education, where continuity of caregivers is linked to healthy child development and with resources for training and quality improvement limited.

Impacts of Child Care Access

Clearly, the affordability and availability of infant and toddler care remains a severe challenge in New York City, as it is in the rest of the country as well. A nationally representative survey of parents with young children—conducted by NPR, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health—found that two-thirds (67 percent) of parents have limited child care options, with one-fifth (19 percent) stating they only have one.[50] Equally unsurprising is that nearly three in four (71 percent) parents report child care has caused serious financial problems for their family.[51] A Care.com survey on child care spending found that one in four parents has gone in to debt, or further in debt, to pay for child care.[52] How parents navigate child care decisions—whether to pay for care and, if so, what type of care to use—has both short- and long-term implications for their family’s economic security. But the constraints on these decisions can also impact their children’s health and development, as a growing body of research now shows.

Parental Employment and Earnings

Access to reliable child care is closely tied to job stability. A 2013 Campaign for Children survey of more than 5,700 parents in New York City found that the vast majority (95 percent) rely on child care programs to be able to work.[53] The inverse—that unreliable child care breeds job instability—is also true. For low-income families, who are more likely to work in sectors with fewer job protections, where they are paid by the hour and have limited sick or personal leave, unreliable or unstable child care can be especially costly. Missing work when child care arrangements fall through can lead to the loss of their jobs and their families’ only source of income. Moreover, lapses in child care not only create economic uncertainty for families in the short term but can also add up to lower wealth over a lifetime and a greater likelihood of living in or near poverty in old age.[54]

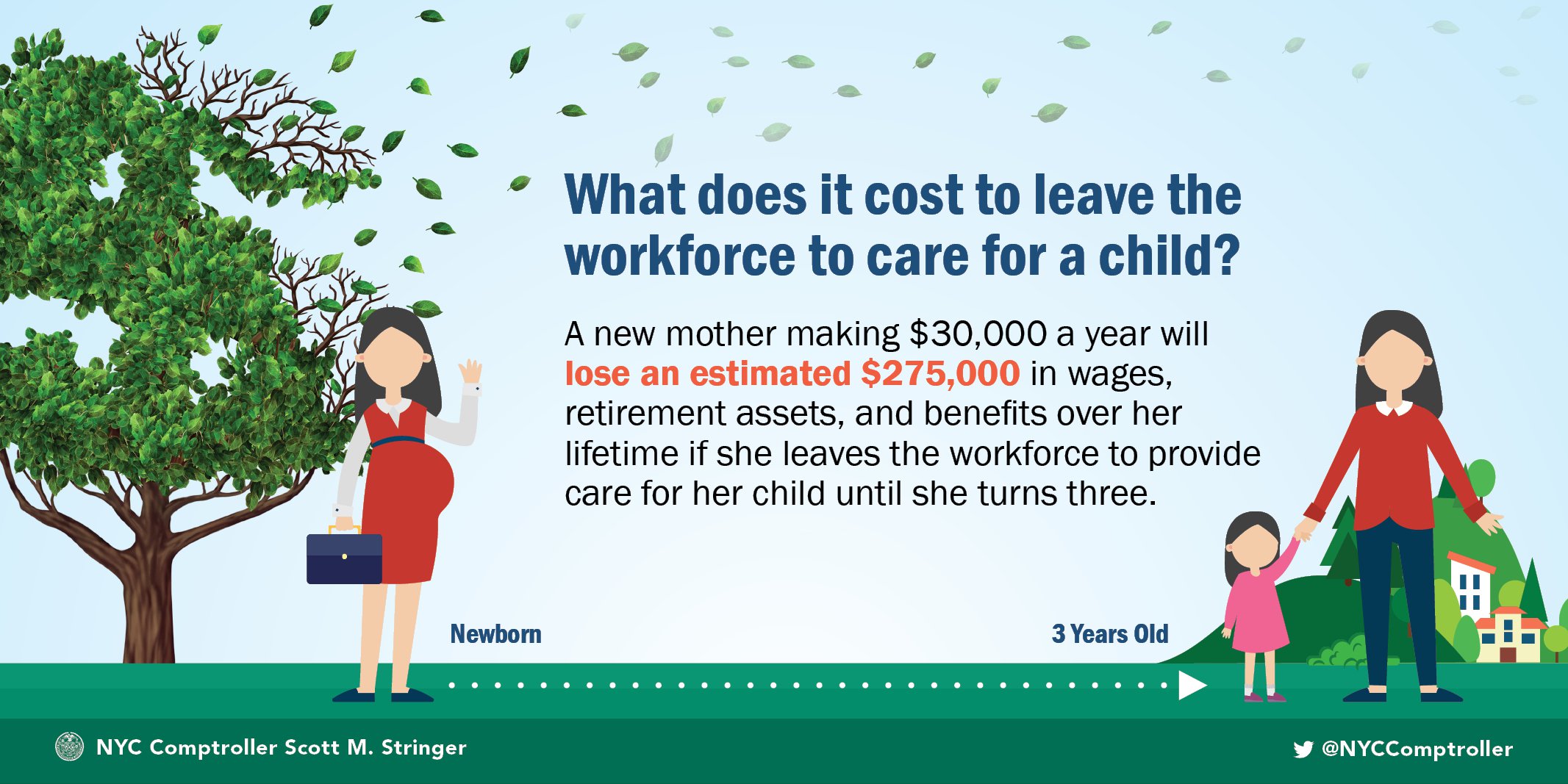

Although child care enables parents to work, the price tag can also have a perverse impact on employment. This is especially the case for secondary earners, for whom it may be more cost-effective in the short term to provide care themselves than to work and pay for child care. According to Care.com’s survey, nearly one in four (23 percent) parents switch from a full-time to a part-time schedule or become a stay-at-home parent to save on child care.[55] While such an arrangement may solve the immediate problem of affording child care, the long-term costs are significant—and gendered. As women are more likely than men to be secondary earners and to assume caregiving responsibilities, women are more likely than men to forego paid work to care for children full-time.[56] In her 2001 book The Price of Motherhood Ann Crittenden famously estimated that a mother’s decision to leave the workforce to provide care costs on average $1 million in lost and reduced earnings over her lifetime. This “Mommy Tax,” as coined by Crittenden, and women’s persistently disproportionate share of unpaid care work remain major drivers of the gender wage gap today.[57]

What does it really cost to leave the workforce to care for a child?

The average age of first-time mothers in New York City is 28.[58] At that age, according to a tool developed by the Center for American Progress, a new mother making $30,000 a year—about half the median income of New York City families—will lose an estimated $275,000 in wages, retirement assets, and benefits over her lifetime if she leaves the workforce to provide care for her child until she turns three.[59] Market-rate center-based care over the same three-year period would cost around $56,000, more than half her total salary but one-fifth her potential lost income.[60]

Since 2000, women’s labor force participation has fallen in the U.S. while it has risen in other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countries, including Canada, the United Kingdom, and France, where mothers have access to more generous leave and subsidized child care programs.[61] A recent analysis attributed five percent of the decrease in overall women’s employment and 13 percent of the decrease in employment among mothers with children under five between 1990 and 2010 to the rising cost of child care.[62] In total, U.S. families give up $8.3 billion in lost wages each year because of a lack of child care, according to the Center for American Progress.[63] This does not account for the costs to cities and states in lost tax revenue.

Child Development and Wellbeing

Young children’s cognitive, physical, and socioemotional development is highly influenced by their early environments and relationships. Nurturing and responsive infant and toddler care is vital, particularly given the pace at which children’s brains grow; by age three, more than 80 percent of brain development is already complete.[64] Yet, the high cost and inaccessibility of infant and toddler care can drive families to use child care arrangements that may be of a lower quality or less reliable than they would otherwise choose. For example, in unregulated environments, the ratio of providers to children may be too low for caregivers to provide safe, attentive care. This disadvantages children in the short term and, as skill begets skill, can lead to persistent achievement gaps.[65]

Low-income families are more likely than families with more moderate means to experience adverse early childhood environments. Developmental gaps have indeed been found to emerge across socioeconomic lines. A 2009 analysis of nationally representative data by Child Trends found gaps in cognitive, social, and health outcomes between children in families below and above 200 percent of poverty as early as nine months old, with disparities growing by age two.[66] Eighty-eight percent of infants in families below 200 percent of poverty were found to have multiple risk factors for poor outcomes.[67] That meaningful developmental gaps are evident in infancy further underscores the need for high-quality care before pre-kindergarten.[68]

Longitudinal studies confirm that children from low-income backgrounds make significant developmental gains in high-quality early childhood education programs, and that the individual and social benefits extend into adulthood.[69] One of the most well-known studies, the Abecedarian Project, found that at age 21, those who had received a high-quality early education program from birth to age five scored higher on cognitive tests, were more likely to have gone to college or have a skilled job, and were less likely to have been a young parent compared to those who had not been in the program.[70] At age 30, the program participants were more likely to have been consistently employed full-time and less likely to have utilized public assistance, indicating that they experienced greater financial stability as adults.[71] Reductions in crime and in the use of costly remedial education and public assistance, demonstrated in an extensive body of early education research, illustrate that high-quality child care benefits whole communities and multiple generations.[72] Indeed, researchers have estimated that society can reap an economic return of over $8 for every $1 spent on high-quality early childhood education.[73] Even cost-benefit studies that have found more modest economic returns show that children’s lifetime gains exceed the cost of the programs.[74]

Calling New York City Home

Child care expenses will likely alter the demographics of New York City in the years to come, if they have not already. A 2017 poll commissioned by the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York found that 76 percent of New York City parents worry about being able to afford to raise a family in the city, and nearly half (44 percent) have considered moving outside of the city to be able to better afford care. Communities of color appear to feel this pressure more acutely; while less than one-third (29 percent) of white respondents state that they have considered moving, more than half (51 percent) of Black respondents and three in four (74 percent) Latinx respondents do.[75] Not all prospective parents who contemplate leaving the city will choose to or have the resources or ability to do so, but child care is undoubtedly a major driver of families’ decisions regarding where to live.

Child Care Assistance in New York City

In the U.S., families shoulder the majority of the cost of child care, especially for infants and toddlers. As of 2011, parents of only 3.4 percent of children under one and 4.2 percent of one- and two-year old children received government assistance—federal, state, or local—to help pay for child care (see Chart 3).[76] A patchwork system of federal, state, and local funding does exist to help bring down the child care to income ratio and provide families with more than one child care option, but resources are limited.[77]

Chart 3: Percent of Children Under Five in U.S. Whose Families Receive Child Care Assistance

Source: Lynda Laughlin, Who’s Minding the Kids? Child Care Arrangements: Spring 2011 (2013), Current Population Reports, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2013/demo/p70-135.pdf.

While the types of child care assistance are generally the same throughout the country, jurisdictions set different eligibility guidelines. In New York City, fully or partially subsidized child care is available to eligible low-income families and families receiving cash assistance; in addition, families with income below $30,000 are eligible for a refundable tax credit, the New York City Child Care Tax Credit. For higher-income families with infants and toddlers, assistance is limited to modest federal and state child care tax credits.

Subsidized Care

Families may access subsidized child care through enrollment in one of the City’s contracted center- or home-based child care programs, EarlyLearn NYC, or by obtaining a voucher, which can be used to pay for care in a center, family day care, or by an informal provider. In New York City, both types of subsidized child care are funded with a mix of federal, state, and City dollars, and families seeking care must therefore meet all of the applicable federal, state, and local eligibility requirements. Importantly, the federal grant programs Head Start and the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), the primary source of child care funding, are means-tested, and the availability of assistance is subject to annual appropriations by Congress.

New York Child Care Regulations

Families guaranteed a child care subsidy:

· Families receiving cash assistance

· Families with income at or below 200 percent of poverty whose cash assistance case closed in the prior year

· Families eligible for public assistance but choosing subsidy only

Families eligible for a child care subsidy only if additional funding is available:

· Families with income up to 200 percent of poverty

Federal law and HHS regulations give states wide flexibility to establish CCDF program eligibility rules, but income eligibility is capped at 85 percent of state median income, equal to around $78,000 for a family of four in New York.[78] New York State restricts eligibility further. State law requires local jurisdictions to provide child care subsidies to families receiving or transitioning from cash assistance first, and if additional funding is available, localities may then make subsidies available to families with income up to 200 percent of poverty who meet additional programmatic or categorical eligibility rules, including being engaged in work or education, experiencing homelessness, or having a protective services need for care.[79] However, CCDF has never been funded at a level sufficient to serve all those eligible, even when supplemented with other funding sources.[80]

In administering child care subsidies, New York City uses the state maximum income eligibility limit of 200 percent of poverty (about $50,000 for a family of four).[81] But families above 100 percent of poverty have tended to comprise a small share of those served. As of 2015, 90 percent of children in subsidized care were in families between zero and 130 percent of poverty.[82] While the number of children utilizing subsidized care at any given time varies, as families transition out of programs and become newly eligible or ineligible, overall enrollment has remained relatively steady since Fiscal Year 2014, with roughly 30,000 children enrolled in contracted EarlyLearn NYC programs and voucher enrollment at about 67,000.[83]

Data obtained from the New York City Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) by the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York, Inc. show fewer infants and toddlers are served than pre-kindergarten and school-age children.[84] About one-quarter of EarlyLearn NYC spaces (26 percent) and just under one-quarter of vouchers (23 percent) were used by children under three, with infants more likely to be using a voucher and toddlers more likely to be in EarlyLearn (see Chart 4).[85] Based on U.S. Census Bureau data, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that only about one in seven children under three in income-eligible families is served.[86] EarlyLearn contracts are transferring from ACS to the New York City Department of Education (DOE) in 2019, and DOE will be managing a new system of birth-to-five contracted programs. While DOE is committed to expanding slots for three-year-olds over time (in line with the vision of 3-K for All), as of the time of writing, it is not known whether the new contracts will preserve these slots for infants and toddlers.

Chart 4: Use of Subsidized Care by Type and Age Group

Source: Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York, Inc., Keeping Track Online: The Status of New York City Children, “Child Care Voucher Utilization for All Children,” “Enrollment in EarlyLearn Contracted Care for All Children,” and “Enrollment in Subsidized Child Care for All Children,” https://data.cccnewyork.org/data#any/3.

The federal climate in recent years, specifically as it relates to child care, helps explain some of the pressures and constraints on the system locally. Federal funding for CCDF has been declining in constant dollars since 2002, and nationally, the number of children receiving a child care subsidy had reached all-time lows in 2015.[87] In 2014, Congress passed new health and safety requirements for subsidized child care but did not appropriate funds to support their implementation, which compounded the program’s fiscal challenges. In 2017, the Center for Law and Social Policy (CLASP) estimated that states would need $1.4 billion above the current funding levels just to enforce the new standards and maintain existing child care slots.[88] As a result, a number of states, New York included, requested waivers to extend the timeline for implementation.[89] According to OCFS, complying with all of the new federal regulations without additional resources would have resulted in an estimated 65,000 to 70,000 families across the state losing access to subsidized child care.[90]

In early 2018, as part of a budget deal to keep the federal government running, members of Congress agreed to increase spending for CCDF over the next two federal fiscal years. And in March 2018, Congress appropriated $2.4 billion in new funding for CCDF, bringing total annual discretionary funding to $5.2 billion. Those who advocated for the additional dollars hoped this new funding would allow states to fully implement the revised federal health and safety regulations while also expanding subsidies to more children.[91] However, New York estimates the new requirements will cost $78 million to implement, making expansion a challenge in the short term.[92]

Even if subsidies were fully funded, some barriers to accessing care would remain. Federal and state rules regarding income eligibility exclude moderate-income families who need assistance, and for families near poverty, their required contribution toward the cost of care can be prohibitively high. OCFS directs localities to ensure family copayments, which must be based on a sliding scale, per State statute, do not exceed 35 percent of a family’s income above poverty. ACS in turn utilizes a fee schedule that caps copayments at 17 percent of income.[93] This is more than twice the Comptroller’s Office’s target affordability benchmark of 8 percent. For a family of three at 200 percent of poverty ($42,660), 17 percent of income is more than $7,000 a year, or about $600 a month, more than 40 percent of median rent in the city.[94]

In addition, the funds that child care providers who participate in the existing subsidy system are reimbursed for services may be too low to support the actual cost of care and ensure fair wages for staff. The latest child care market rates released by OCFS, the ceiling for reimbursement to providers, are in most cases higher than those produced by the last market-rate survey; however, the 2019-20 State Budget did not include funding to support the rates in New York City at the 69th percentile, and other gaps remain.[95] The Center for American Progress’ cost modeling on infant and toddler care, for instance, puts the cost of meeting minimum health and safety standards in New York at about 13 percent higher than the maximum reimbursement rates for family day care in the city.[96] A recent study of early childhood education programs run by United Neighborhood Houses’ member settlement houses put the gap between government funding and expenses at 41 percent, including a per-child gap of 56 percent for center-based infant and toddler care.[97]

OCFS lowered reimbursement rates from the federally-recommended 75th percentile of the market-rate survey to the 69th percentile in 2014 in order to limit reducing the number of families that could be served. However, this resulted in reduced payments to providers, already struggling to maintain services. At the same time, the issue of how best to set reimbursement rates was being raised during the federal reauthorization of CCDF, and federal law now gives states permission to explore alternative strategies beyond the traditional market-rate survey.[98] State legislation has been introduced that would require OCFS to implement a cost estimation model that would establish the actual costs of care, but in the meantime, providers continue to depend on other sources of revenue to cover any shortfalls.[99]

Tax Credits

New Yorkers may claim several tax credits to help offset the cost of qualifying child care services. At the federal level, the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC) provides up to $1,050 to families with one child and up to $2,100 to families with two or more children up to age 13. Because the federal CDCTC is nonrefundable, it provides limited benefit for families with little or no tax liability. At the state level, the New York Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, worth up to 110 percent of the CDCTC, is, in contrast, refundable, and families are able to receive the credit amount that exceeds their tax liability.[100] Neither the federal CDCTC nor the New York State CDCTC are means-tested, so benefits are distributed across all income levels.

In 2007, New York City became only the second city in the country to establish a local child care tax credit. Unlike the federal and state credits, the New York City Child Care Tax Credit (NYC CCTC) targets support to families with children up to age four and income near poverty. Families with annual income under $30,000 are eligible, and the maximum value of the refundable credit is $1,733.[101] In 2016, 13,810 filers claimed the credit, and the average credit was $343.[102] If the maximum NYC CCTC were combined with the maximum federal and state child care tax credits, a family with one child would receive $3,071. This can represent significant savings for families, particularly those with low incomes who are utilizing a less expensive form of care; however, it equals less than one-sixth (16 percent) of the average annual cost of center-based infant and toddler care. While families who qualify for the NYC CCTC are also income-eligible for subsidized care, there is, as noted earlier, no guarantee of a subsidy unless families are receiving or transitioning from cash assistance.

Elected officials have proposed expansions to existing child care tax credits but few proposals to date have targeted substantial benefits to low-income families. Notably, the Enhanced Middle Class Child Care Tax Credit, which first passed as part of the fiscal year 2017-18 State Budget in April 2017 and supplements the existing New York State Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, increases refundable tax credits by a maximum of $260 for families with annual income between $50,000 and $150,000.[103]

As with the subsidy system, the provision of child care benefits through the tax code has certain limitations. Even if all child care tax credits were refundable and expanded to more closely reflect actual child care costs, some low-income families would still see no or little benefit. Specifically, because the credits are disbursed as a lump sum annually and child care payments must be made throughout the year, typically on a weekly or monthly basis, tax credits are not as helpful for parents with limited or irregular sources of income.

Policy Recommendations

New York City is certainly not exceptional in failing to provide adequate support to parents of infants and toddlers, though the high cost of living in the city compounds the challenges associated with affording quality child care. The U.S. ranks 34th out of 36 OECD-member countries in public spending on child care and early education, ahead of only Turkey and Ireland. And compared to the OECD average of 0.7 percent, child care spending represents only 0.3 percent of gross domestic product in the U.S. Denmark, which bests all OECD countries in child care enrollment (61.8 percent, compared to 28.0 percent in the U.S.) and has the lowest child poverty rate (2.9 percent, compared to 19.9 percent in the U.S.), spends roughly four times more on early childhood education and care as a percentage of GDP than the U.S.[104]

Other countries’ approaches to child care make clear that poor access is not inevitable. Families with low and moderate incomes do not inherently need to worry about making ends meet if or once they have children, but U.S. policies have made that the norm. Fortunately, a broad range of local and national stakeholders representing a variety of political ideologies and fields, from academia to advocacy, have called for a reimagining of the nation’s child care system. While they may not agree on what form it should take—proposals from prominent think tanks and officials vary—they agree that current levels of assistance are wholly inadequate and that government must be a major part of the solution.[105]

Several members of Congress have also taken up the fight for better child care, including by advocating for substantial new public investments in subsidies. In September 2017, U.S. Senator Patty Murray, the Ranking Member of the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, and U.S. Representative Bobby Scott, now the Chair of the House Education and Labor Committee, introduced the Child Care for Working Families Act, which would authorize funding needed to broaden eligibility for child care subsidies, nearly doubling CCDF’s income limit from 85 percent of state median income to 150 percent, and guarantee assistance for all who are eligible.[106] In addition to subsidizing care for millions of previously unassisted families, the bill would direct funds to construct and renovate child care facilities and ensure all child care providers are paid a living wage. While it remains unclear whether a federal investment in child care of this scale will be made in the near-term, the bill does offer a vision of what it will take to make child care truly accessible to all.[107]

At the state level, relatively little action has been taken to implement a comparable plan. In fact, in recent years some states had moved in the opposite direction, further restricting eligibility for subsidies in order to patch together funding to meet the 2014 federal quality regulations.[108] To the extent that state and local governments have made investments in early childhood programs, most have prioritized pre-kindergarten reform over infant and toddler care, with a majority of states working to build and increase enrollment in state-funded pre-kindergarten programs. As of 2018, 44 states (including New York) and the District of Columbia had established such programs, collectively reaching 33 percent of all four-year-olds and 6 percent of all three-year-olds nationwide.[109] In a handful of localities, however, attention is gradually shifting to infants and toddlers. In San Francisco, voters approved a ballot measure in June 2018 that would raise approximately $150 million in tax revenue to expand subsidized child care for children under four.[110] And in September 2018, the Council of the District of Columbia passed and Mayor Muriel Bowser signed a bill that would, if funded, extend eligibility for subsidized child care to every child under three in the District within ten years.[111]

The Comptroller’s Office estimates that New York City currently spends roughly $1.6 billion on early childhood education and care for children under five, but only about $250 million, or 16 percent, on infants and toddlers.[112] Analysis of data on the Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York, Inc.’s Keeping Track Online database shows that about 45 percent of all three- and four-year-olds in the city are enrolled in publicly-funded care, compared to only 7 percent of the city’s infants and toddlers (see Chart 5).[113] While investments in pre-kindergarten are important, and the Comptroller supports the City’s introduction and expansion of 3-K for All, failing to adequately fund infant and toddler care misses an opportunity, as this report shows, to reach families when the costs of care are most burdensome, children’s development is most rapid and dynamic, and the potential return on each dollar invested is greatest.[114]

Chart 5: Estimated Share of NYC Children in Publicly Funded Care, by Age Group

Source: Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York, Inc., Keeping Track Online: The Status of New York City Children, “Enrollment in Publicly Funded Care for Children Under 5” and “Population of Children Under 5,” https://data.cccnewyork.org/data#any/3. Publicly funded care includes subsidized child care (EarlyLearn NYC and vouchers) and universal pre-kindergarten (3-K for All and Pre-K for All).

Making Quality Child Care for Infants and Toddlers Affordable and Accessible: Introducing “NYC Under 3”

The inadequacy of the current support system necessitates bold solutions and new investments. Currently, not enough families get help paying for care, and many who do still struggle to afford it. Meanwhile, the supply of licensed infant care is limited, and child care workers remain among the lowest paid human services employees in the city, compromising child care quality and providers’ livelihoods.[115] Significant federal resources for child care are undoubtedly needed, but every day New York City fails to take action is another day thousands of families’ access to greater economic security is denied.

To lessen the financial burden of child care, both for parents and the workforce that provides this essential service, and to support increased capacity for the city’s youngest children, the Comptroller’s Office is proposing a multi-year plan to make quality affordable infant and toddler care a reality for New York City families. The proposal, NYC Under 3, includes a series of recommendations aimed at addressing the related goals of child care affordability, accessibility, and quality, outlined in detail below: (1) lowering families’ contributions toward child care and extending child care assistance to working families with income up to 400 percent of poverty, (2) dedicating funding for child care start-up and expansion grants and making a capital commitment of $500 million to support the construction and renovation of child care facilities, and (3) increasing payments to providers and creating a fund to expand providers’ access to training and technical assistance.

1. Affordability: Lower families’ contributions toward child care and extend child care assistance to working families with income up to 400 percent of poverty (about $100,000 annually for a family of four).