Protecting Our Most Vulnerable Populations

New York City has emerged as the epicenter of the global COVID-19 pandemic, making the fight to halt its spread within the five boroughs one of the great public health challenges of our time. Many questions remain about how the virus can be fully eradicated and how cities in general can best protect themselves, but one thing is clear already: deep, existing inequities based on class and race have been brought into stark relief by the current outbreak.

Already, we know that Black and Latinx New Yorkers are twice as likely to die of the virus than Whites, a fact presaged by decades of public health disparities pertaining to asthma, diabetes, obesity, and other conditions that can complicate COVID-19, as well as a historic lack of access to quality preventative care in lower income communities of color. Correcting these inequities must be a singular priority of the City moving forward.

More immediately, the current shutdown and quarantine have placed unique stresses and strains on communities of color, immigrants, seniors, and low-income New Yorkers that must be addressed urgently. Consider the single parents, living in poverty, trying to teach their children remotely while struggling to keep them fed. Or the many non-citizens and undocumented New Yorkers living in overcrowded, poorly maintained apartments across the city who are barred from accessing federal benefits, and yet today are increasingly unemployed and struggling to pay the rent or put food on the table.

Or the seniors, many of them living alone, disconnected from family and social supports. Or the disabled, cut off from their nurses and home health aides, whose limited mobility makes navigating the city in this time of long lines and social distancing that much more challenging.

In these trying times, it is essential that vulnerable communities—whether suffering amidst quarantine or with an increased likelihood of COVID-19 infection—are rapidly identified and cared for. This report, by New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, takes a data-driven approach to examining and mapping some of these populations by Community District in the hopes that they may serve to guide the City’s ongoing efforts to help New Yorkers in need, contain the virus, and to arm communities with information that could help to stem the tide.

City government must marshal all the resources of the Department of Social Services, the Department of Health, the Department for the Aging, the Department of Homeless Services, the New York City Housing Authority, Housing Preservation & Development, and other frontline agencies and take a coordinated approach to protecting all vulnerable populations. That should include working with the Mayor’s Office of Data Analytics and the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications to tap into DataBridge, the Citywide data sharing platform.

There are 8.6 million stories in New York, and every single person has their own individual needs in this time of crisis. But we can start by identifying where our most vulnerable populations are concentrated so that we can proactively reach out, get them the resources they need, and hopefully prevent the next person—the next mother, father, or grandparent—from getting sick, going without food, or suffering amidst this pandemic.

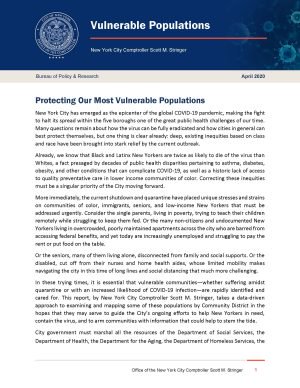

Overcrowded Apartments

In recent years, as neighborhoods across the five boroughs have grown ever more expensive, more and more New Yorkers have been forced to live in crowded conditions. Crammed into basements and illegal subdivisions, bunked up three or four to a room, sleeping on couches—these are the measures that low-income New Yorkers must take to survive in a city with too few housing units for an ever-growing population.

We know already that proximity matters in the spread of COVID-19, and that transmission between family members is one of the leading drivers of the outbreak across the globe. We also know that being marooned in an overcrowded apartment for weeks on end can take a severe physical and mental toll. Identifying communities with high concentrations of overcrowded apartments, then, and providing information to residents in those neighborhoods on how to take precautions, simply makes sense.

In 2018, nearly 290,000 apartment and housing units were overcrowded—with more than one person living per room (see Chart 1). This marks a 17 percent increase over the last decade. Across our housing stock, the shock of the Great Recession is still deeply felt, precipitating a marked increase in overcrowding that has been sustained ever since.

Chart 1

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey. 2008-2018 1-Year Estimates.

Unsurprisingly, overcrowded conditions are not uniform across the five boroughs. In fact, they vary widely by race, ethnicity, geography, and occupation. While less than 10 percent of white New Yorkers live in an overcrowded housing unit, for instance, 15 percent of Black, 24 percent of Asian, and 25 percent of Hispanic New Yorkers do (see Chart 2). Among frontline workers, meanwhile, 16 percent live in overcrowded housing units.[1]

Chart 2

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

These racial disparities are particularly evident when we look across the five boroughs. Overcrowded apartments are particularly prevalent in neighborhoods with high concentrations of immigrants—and which today are among the hardest hit by COVID-19.

Jackson Heights leads the way, with 25.7 percent of rental units that are overcrowded. It is followed by Elmhurst/Corona (25.3 percent), Borough Park (24.7 percent), Sunset Park (20.5 percent), Bedford Park (19.3 percent), Concourse/Highbridge (18.7 percent), Bensonhurst (17.1 percent), East New York (16.6 percent), and University Heights (15.7 percent). By comparison, less than 4.5 percent of units are overcrowded in Battery Park, Greenwich Village, Park Slope, Tottenville, and Murray Hill (see Map 1).

Map 1

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2018 1-Year Estimates. Via Citizen’s Committee for Children of New York. “Overcrowded Rental Housing,” Keeping Track Online.

To make matters worse, many of these overcrowded neighborhoods (like Jackson Heights) also have the least open space and most congested corridors. When exiting the home for essentials or a quick breath of fresh air, finding solitary space and maintaining safe social distancing can be harder than not in these communities. As the weather gets warmer in the coming months, addressing these issues will become increasingly urgent.

Recommendation 1: The City must leverage its large stock of vacant hotels and dormitories to house not only the homeless, but also those living in overcrowded apartments who are in danger of infecting their families and roommates. Those who are potentially infected must be given options to better isolate themselves in order to stop the spread of the virus both now and in the coming months, as other countries have successfully implemented.

Recommendation 2: To help those living in overcrowded neighborhoods with limited park access, the city should expand sidewalks and parks and close streets. They can begin by bumping out the sidewalk into the parking lane along commercial corridors, closing streets within large parks and around the circumference of neighborhood parks, and limiting car access on select residential blocks.

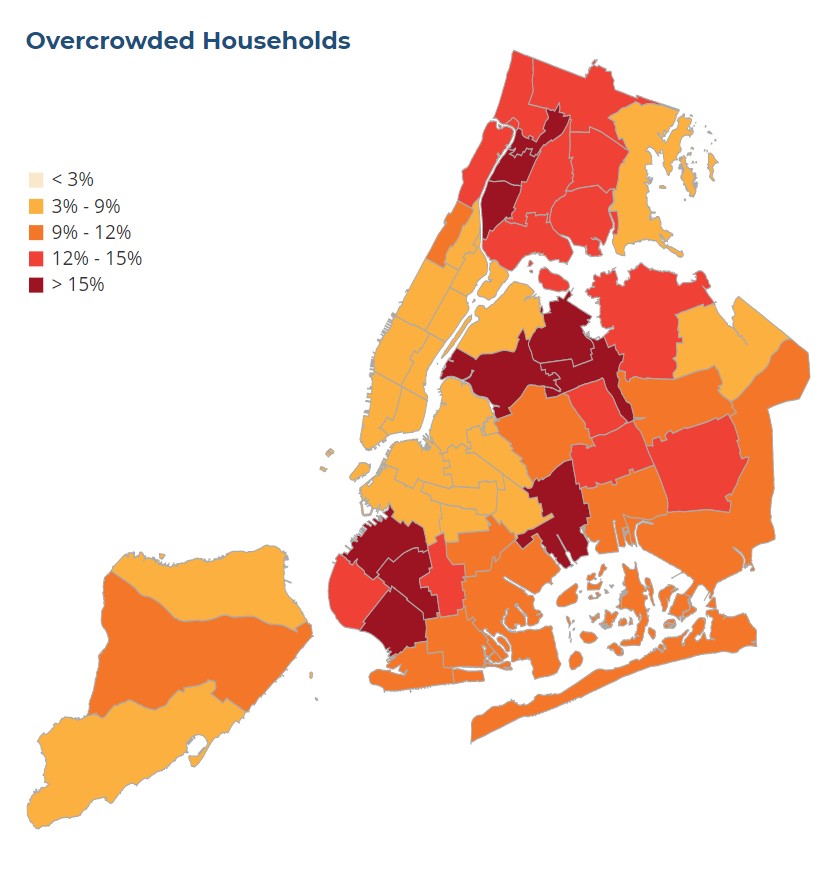

Unsanitary and Unsafe Living Quarters

Much like crowded apartments, being quarantined in poorly maintained and unsanitary housing is deeply unpleasant and potentially unsafe. Peeling paint, holes in the walls, rodent infestations, leaking faucets, broken toilets—for years, hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers have suffered these misfortunes and indignities each evening when they return home from work and school. Now, amidst this crisis, they are inescapable 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Throughout the city, nearly 15 percent of rental housing units reported three or more maintenance deficiencies in the most recent United States Census Housing Vacancy Survey. This ranged from as high as 26 percent of units in the Bronx, to as low as 8 percent in Staten Island.[2]

These conditions are even more acute in individual neighborhoods, many of which suffer staggeringly high rates of maintenance deficiencies. This includes University Heights (35 percent), Brownsville (34.4 percent), Bedford Park (31.5 percent), Crown Heights North (29.5 percent), Riverdale (28.9 percent), Concourse/Highbridge (26.9 percent), Bedford Stuyvesant (26.6 percent), and Hunts Point (25.1 percent). In Ridgewood, South Beach, Queens Village, Bayside, and Howard Beach, meanwhile, less than 3 percent of rental units reported multiple maintenance deficiencies (see Map 2).

Map 2

United States Census Bureau. “Housing Vacancy Survey, Microdata Files,” 2017. Via Citizen’s Committee for Children of New York, “Maintenance Deficiencies,” Keeping Track Online.

These unsanitary and unsafe housing conditions are particularly prevalent in communities of color. In total, 25 percent of Black and 23 percent of Hispanic New Yorkers live in rental units with three or more maintenance deficiencies—compared to just 9 percent of Asian and White New Yorkers (see Chart 3).

Chart 3

Where We Live NYC. “Housing Conditions,” City of New York.

Equally troubling, it is children and the elderly who are far more likely to be quarantined in dilapidated apartments over the course of this pandemic. A troubling 20 percent of families with children and 15 percent of New Yorkers over the age of 62 live in housing units with significant maintenance deficiencies, as compared to 14 percent of adult families and 11 percent of single adults (see Chart 4).[3]

Chart 4

Where We Live NYC. “Housing Conditions,” City of New York.

Recommendation 3: New Yorkers quarantined in uninhabitable apartments should be given the option of relocating to hotels and dormitories.

Recommendation 4: The City should work with landlords and building services companies to ensure that all cleaning and maintenance workers have access to ample personal protective equipment.

Recommendation 5: The City should create a bank of cleaning supplies, including sanitizing wipes, and open it up to New Yorkers in need. These supplies could be offered at public schools alongside grab and go meals.

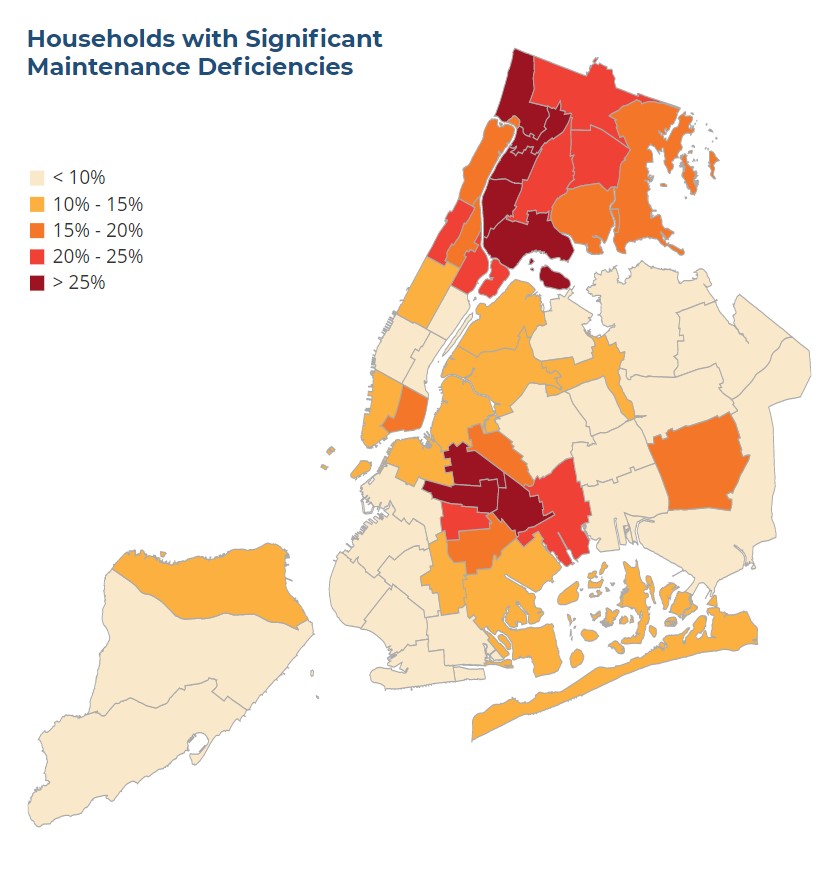

Poverty

For over 1.5 million New Yorkers, poverty is an ever-present condition.[4] Many of these New Yorkers rely on friends, family, and fellow worshippers to make ends meet and to afford the basic necessities. Now, amidst this pandemic and quarantine, many of those lifelines have become frayed.

Low-income families, in fact, are uniquely isolated within their homes. While many New Yorkers are able to FaceTime with friends, check on the news, and keep up with work and school, a large share of New Yorkers have neither broadband internet access to the home nor a cellular data plan. In total, 504,000 New York City households have no internet access. Among those with less than $20,000 in annual income, 38 percent (or 231,000 households) are without an internet connection. This compares to 17 percent of households with earnings between $20,000 and $75,000 and 5 percent for those with income of $75,000 or more (see chart 5).

Chart 5

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2018 1-Year Estimates. Via Citizen’s Committee for Children of New York, “Household Internet Access,” Keeping Track Online.

This disconnection, isolation, and deprivation is particularly grave for single parents, who are confronting all of the usual stresses of parenting while also helping their children learn remotely from home. Across the five boroughs, there are approximately 230,000 single parent households who are living below the poverty line (see Map 3). The densest clusters are in East Tremont/Morrisania (16,605 households), Mott Haven/Hunts Point (14,118), University Heights (13,335), Concourse/Highbridge (12,558), and Soundview (10,576).

Map 3

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2015-2018 3-Year Average. Via Citizen’s Committee for Children of New York, “Child Poverty,” Keeping Track Online.

As is apparent from the map, poverty is particularly concentrated in communities of color. In fact, a staggering 34 percent of Hispanic children, 27 percent of Black children, and 20 percent of Asian children live below the federal poverty line—compared to 16 percent of White children (see Chart 6).[5]

Chart 6

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2015-2018 3-Year Average. Via Citizen’s Committee for Children of New York, “Child Poverty,” Keeping Track Online.

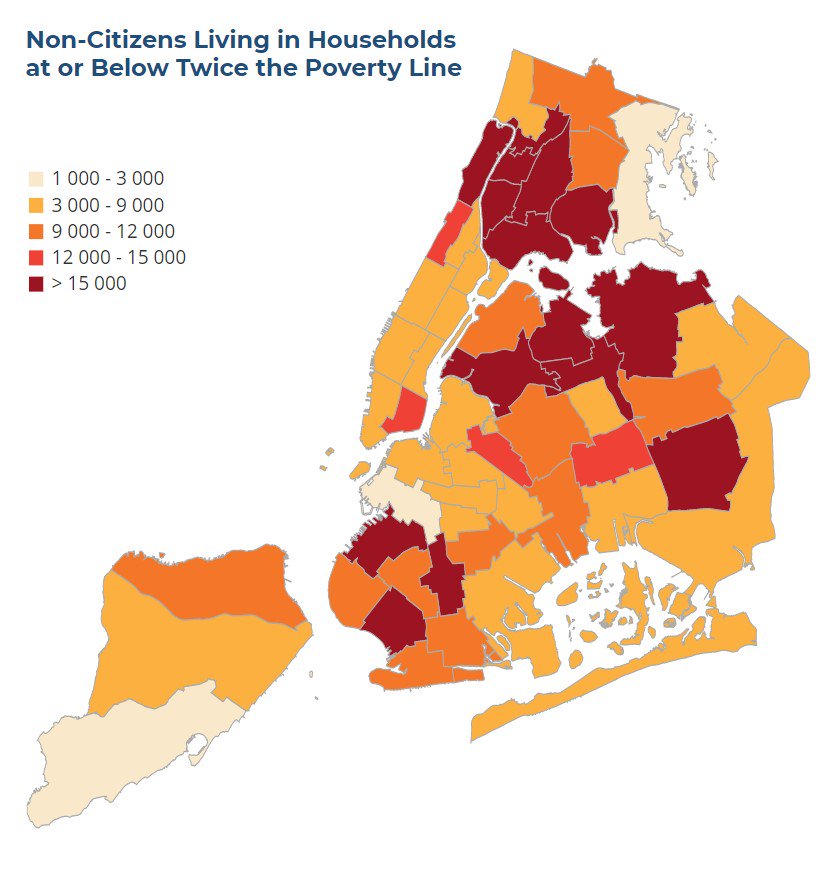

The profound stresses of poverty are also acutely felt by non-citizens. Many safety net programs are not available to immigrant New Yorkers until they become citizens or have been in the country for five years. Undocumented workers, meanwhile, are completely barred from federal benefits, making their day-to-day lives that much more tenuous at a time of rapidly rising unemployment.

Across the city, approximately 666,579 non-citizens live in households at or below 200 percent of the poverty line (see Map 4). They are largely concentrated in Flushing (37,239), Jackson Heights (30,071), Washington Heights (27,279), Sunset Park (26,790), Elmhurst/Corona (25,128), Concourse/Highbridge (24,362), Bensonhurst (23,788), University Heights (23,085), and Bedford Park (22,071).

Map 4

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

Indeed, these figures from the latest U.S. Census American Community Survey without question underestimate the current scope and depth of poverty in New York City. With industries like Retail, Restaurants, Entertainment, and Tourism completely decimated on account of the COVID-19 pandemic, thousands of New Yorkers are suddenly without jobs. Within these fields, 50 percent of employees are foreign-born, 27 percent are non-citizens, and 34 percent have children living at home.[6] As a result, poverty levels, particularly among non-citizens and single parents, have surely risen.

Recommendation 6: While remote learning is a challenge for all children and families, for some, the barriers to engaging remotely with classrooms have been too difficult to overcome. It is critical that the Department of Education track student engagement across all schools and offer additional academic supports, in multiple languages, to students who have not been participating in remote lessons. Additionally, to ensure that students do not fall through the cracks, the Department of Education must develop a comprehensive educational recovery plan to measure learning loss and provide schools with specific, targeted supports to address learning gaps that have developed during the time of remote learning.

Recommendation 7: In response to this pandemic, the City quickly opened a number of regional enrichment centers to provide a safe learning environment for children of first responders. In addition to those students, however, countless children living in shelters, temporary housing, overcrowded conditions, and in poverty are also in need. To ensure their access to instruction, technology, and even basic school supplies, homeless students should be granted access to enrichment centers.

Recommendation 8: Internet service providers should offer 60-days of free service to all New York City households in need, not just “new customers with K-12 or college students.” Meanwhile, cell phone carriers should institute a moratorium on cutting off service and data plans if bills are delayed or delinquent.

Recommendation 9: WiFi service should be upgraded at all homeless shelters immediately so that families can access critical information more readily and students can do their schoolwork more efficiently.

Recommendation 10: New York is among of the few states that allows SNAP beneficiaries to use their EBT card to buy groceries online. And while this capability is more important than ever, the wait times for orders are currently stretching into the weeks and delivery fees are often exorbitant. To address these issues, companies like Amazon, ShopRite, and Walmart should allow SNAP beneficiaries to skip the cue and wave all delivery fees.

Recommendation 11: Amidst this pandemic and thereafter, all taxpayers should be treated the same, regardless of their citizenship status. As such, cash assistance and unemployment insurance should be extended to anyone holding an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number who is not eligible to obtain a Social Security Number and the State and City should work together to fully fund gaps in the federal safety net. Moreover, to ensure that no one is left behind and to circumvent any federal restrictions, the City should work with private partners to establish an emergency relief fund for all undocumented workers.

Living Alone, Stranded at Home

Amidst this pandemic, many New Yorkers are feeling severely isolated. They are stuck at home, cut off from friends and loved ones, lonely and anxious. In a city of small apartments and smaller living rooms, it is in the streets and parks and bars and theaters where our social lives are played out and fulfilled. Under quarantine, this is no longer possible.

For those living alone, these feelings of separation and isolation are particularly acute. Approximately, 1,015,000 New Yorkers live in apartments and homes by themselves, including 346,717 in Manhattan, 278,582 in Brooklyn, 200,119 in Queens, 151,174 in the Bronx, and 38,075 in Staten Island.[7] And while affording to live alone in a city as expensive as New York is certainly a privilege for some, now, in a time of quarantine, it is a liability for many.

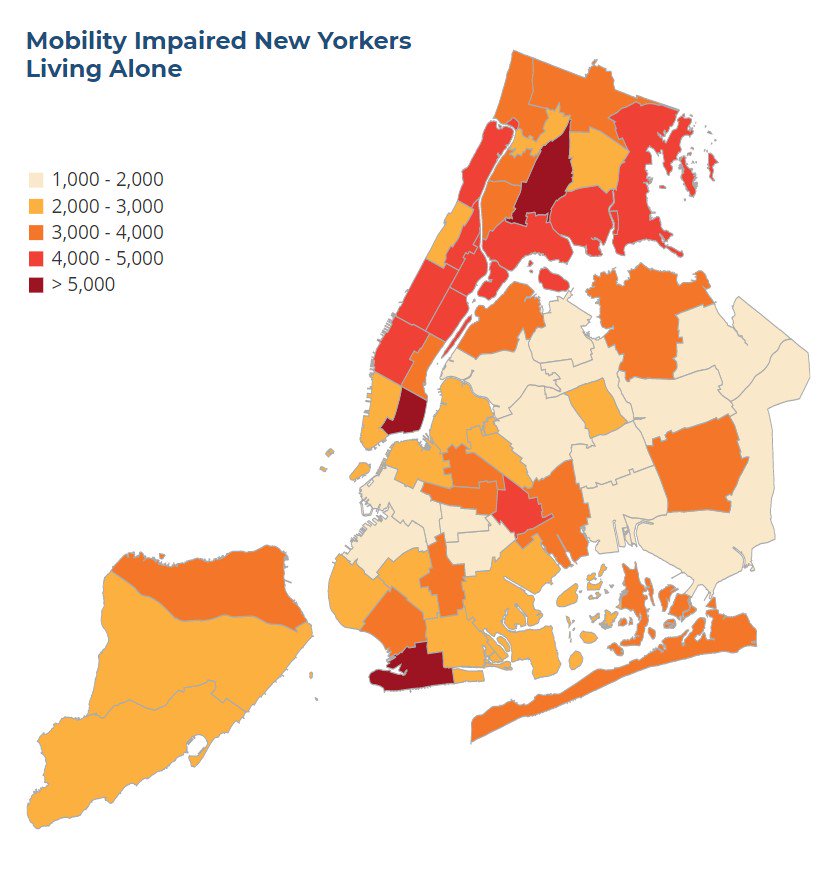

This is particularly true for those with disabilities. Throughout the City, there are approximately 169,142 mobility-impaired New Yorkers living alone and largely dependent on home health aides and other support services. Many of these resources are difficult to access during the pandemic and many home health aides are being forced into the tragic decision of choosing between sheltering in place with their patients or their own families.[8]

Looking at the neighborhood-level, the Lower East Side (5,785) has the largest number of mobility impaired residents living alone (see Map 5). It is followed by East Tremont/Morrisania (5,288), Coney Island (5,123), Hunts Point/Mott Haven (4,800), East Harlem (4,757), Washington Heights (4,752), Central Harlem (4,733), Unionport/Soundview (4,663), Upper East Side (4,541), and Brownsville (4,511).

Map 5

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

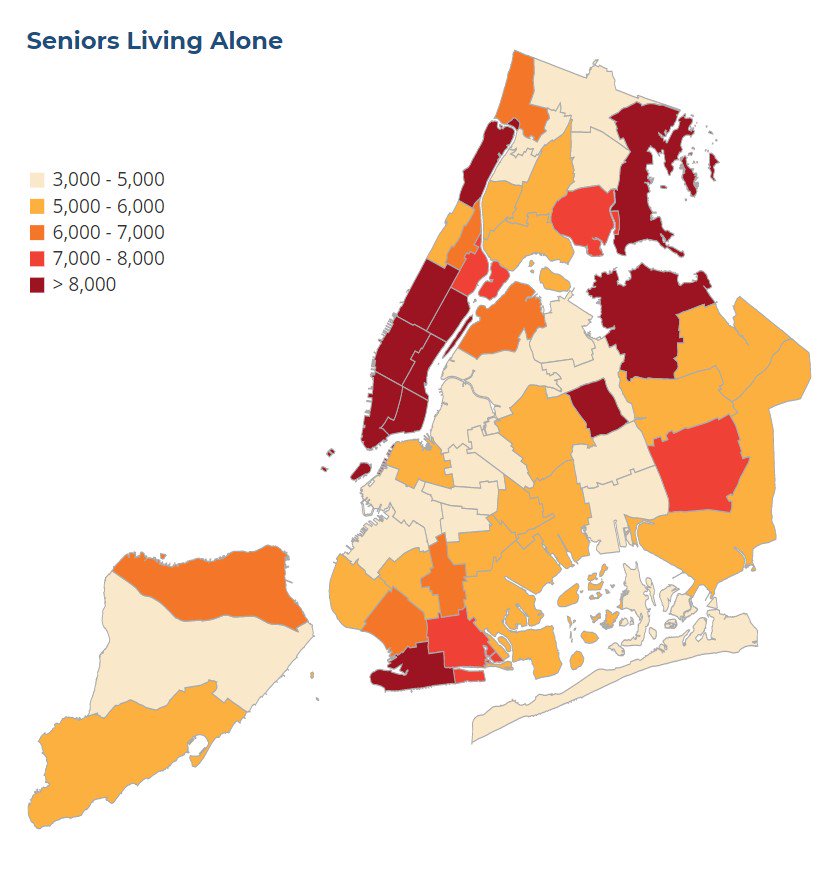

Looking more broadly, older New Yorkers of all stripes are under severe strain during this crisis. Because COVID-19 can be particularly fatal for the elderly, leaving the home and shopping for groceries carries a serious risk. As a result, many are strictly homebound and, for those living alone, utterly isolated.

In fact, one third of all New Yorkers who live alone are over the age of 65. Manhattan neighborhoods lead the way, with approximately 18,646 seniors living alone in the Upper East Side, 16,695 in the Upper West Side, 12,887 in Murray Hill, and 11,199 in Chelsea—as well as 10,524 in Flushing (see Map 6).

Map 6

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

Recommendation 12: The State and City must work closely with home health aides and agencies to ensure that aides and nurses have access to medical-grade personal protective equipment. They should also develop a unified safety protocol for home health aides so that those working for multiple agencies and with multiple clients are not getting conflicting instructions and advice.[9]

Recommendation 13: The City should continue to aggressively ramp up food delivery and make an effort to proactively reach out to every senior in the five boroughs (via robocalls, emails, texts, door hangers, etc.) to ensure that they know how to request home delivered meals. Senior service providers and community-based organization that serve New Yorkers with limited English proficiency should be utilized to help seniors sign-up for meal delivery.

Recommendation 14: The City should be coordinating with senior service providers across the city to cross-check that every senior they serve is successfully receiving home delivered meals and to ensure that all providers are being fully utilized and leveraged in the City’s efforts to ramp up meal delivery and combat social isolation.

Recommendation 15: Pharmacies must prioritize delivery requests to homebound and vulnerable households.

Asthma and Air Quality

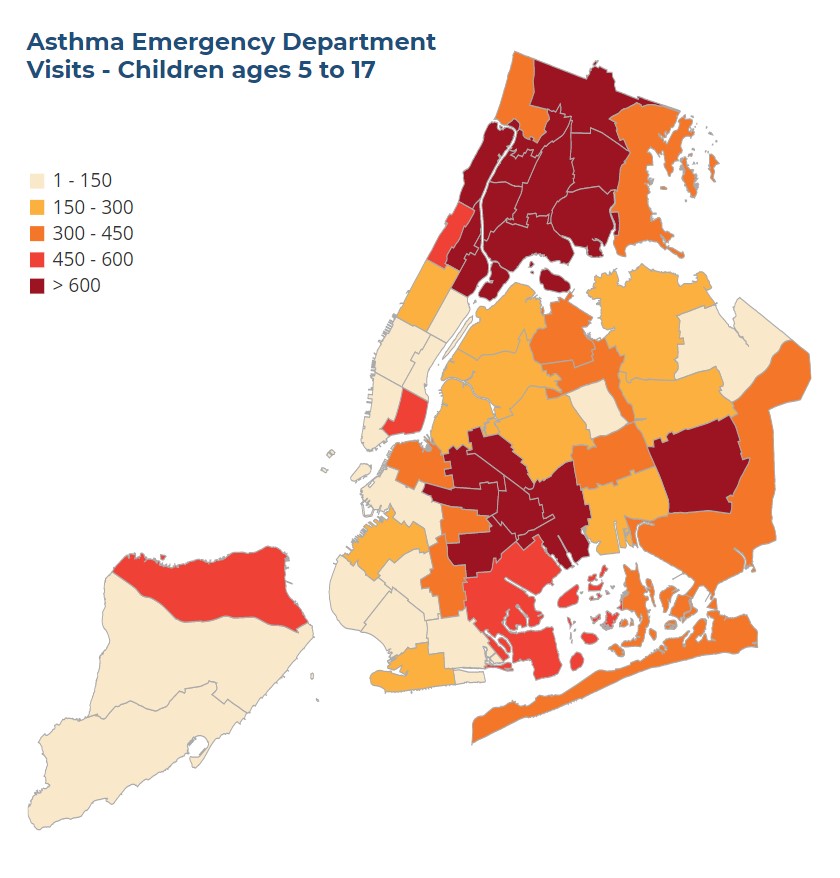

Elderly New Yorkers are not the only ones who are more likely to suffer severe symptoms from COVID-19. Those with existing respiratory difficulties and those who live in neighborhoods with high rates of air pollution are also at high-risk.

Like many inequalities in New York City, these disparities often play out along racial and ethnic lines. Black New Yorkers, for instance, are nearly seven times more likely to visit the emergency room due to asthma-related complications than white New Yorkers, and Hispanic New Yorkers are over three times more likely (see Chart 7).[10]

Chart 7

New York State Department of Health. “New York State Asthma Surveillance Summary Report,” Table 6-1: Asthma Emergency Department Visit Rate per 10,000 Residents. October 2013.

Looking across the five boroughs, these severe respiratory conditions are particularly egregious in the Bronx. Among children age 5-17, there are approximately 10,479 asthma-related emergency room visits each year within the borough. This far outpaced Brooklyn (7,808), Queens (4,210), Manhattan (4,178), and Staten Island (739).

In total, in six Bronx, one Brooklyn, and one Manhattan neighborhood, more than 1,000 asthmatic children visit the emergency room each year (see Map 7). Topping the list were Hunts Point (1,762), East Tremont (1,659), Unionport/Soundview (1,172), Concourse/Highbridge (1,157), University Heights (1,109), Bedford Park (1,105), Brownsville (1,083), and East Harlem (1,028).[11]

Map 7

New York City Department of Health and Mental Health. “Environment & Health Data Portal,” 2018.

These asthmatic conditions are strongly linked to poor air quality, both inside apartments and outdoors. High rates of air pollution can cause and exacerbate respiratory difficulty, which helps explain why higher levels of particulate matter are associated with higher death rates from COVID-19.[12]

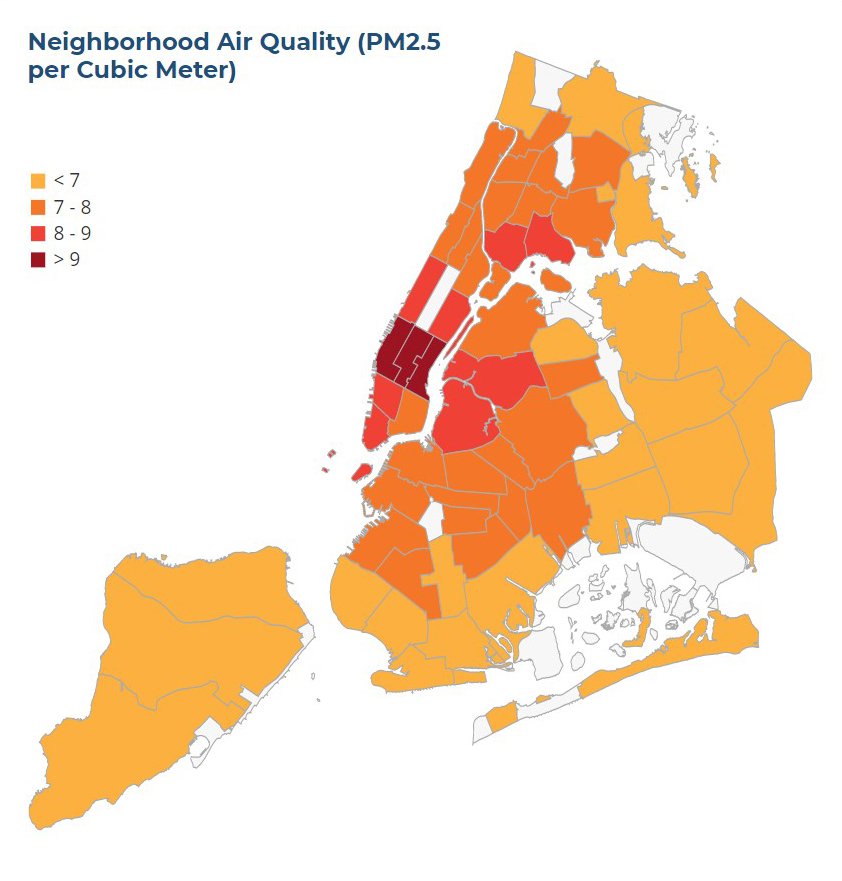

Across the city, concentrations of noxious air pollution (including PM 2.5) are largely found in congested neighborhoods that are densely packed with buildings, cars, and highways. The highest levels were found in lower Manhattan, western Brooklyn and Queens, and the South Bronx (see Map 8).

Map 8

New York City Department of Health and Mental Health. “Environment & Health Data Portal,” 2018.

From the BQE to the Bruckner, the East Side Highway to the Long Island Expressway, each of these areas have numerous highways and thoroughfares coursing through. In a typical year, PM2.5 emissions from cars and trucks are responsible for 320 premature deaths and 870 emergency department visits in New York City.[13] Amidst the COVID-19 outbreak, a lifetime of exposure of these emissions threatens to become even more dangerous and deadly.

Recommendation 17: The COVID-19 pandemic should serve as a clarion call to dramatically improve New York City air quality. This should begin by scaling back dozens of miles of highway lanes throughout the South Bronx, western Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island as part of a larger review of the City’s highway infrastructure. As we face huge budget holes in the coming years, rather than spending billions of dollars reconstructing our unsafe and outdated 1950s highway infrastructure, we should instead save that money, devote it to upgrading public transit, and unwind our dependence on cars and trucks.

Recommendation 18: Beyond highways, the collapse of automobile traffic on local streets and thoroughfares during the pandemic has offered a glimpse of a city less plagued by car congestion, honking horns, vehicle emissions, and reckless driving. Moving forward, the city should use this period and the upcoming months to dramatically reallocate street space, including widening sidewalks, pedestrianizing select neighborhoods, expanding the bus and bike lane network, siting public toilets and water fountains, reallocating parking spots for delivery vehicles and mid-block garbage receptacles, creating 5 m.p.h. slow zones in residential neighborhoods so that children and others can play on the street, and many more sensible interventions.

Recommendation 19: In countries that are beginning to recover from COVID-19, like China, car usage is returning to pre-pandemic levels, but transit usage is still low—largely due to fears regarding the spread of the virus. Such an outcome in New York City would be disastrous for air quality, congestion, and traffic deaths.

Once deemed safe to riders and transit workers alike, the MTA should dramatically increase subway and bus service frequencies in the early morning, late night, and on weekends to help draw riders back to the system. Subways and bus routes should maintain high frequency service all-day, seven days a week in order to minimize overcrowding and so that all New Yorkers—especially frontline workers and the recently unemployed who primarily live in the outer reaches of the outer boroughs and often travel during the off-peak—can get to work and job interviews quickly and without delays.

This should be achieved in tandem with a frequent and strict cleaning regiment throughout the system and the stepping up of protections for all transit workers.

End Notes

[1] For the definition of frontline workers, see: Office of the Comptroller. “New York City’s Frontline Workers,” March 2020.

[2] United States Census Bureau. “Housing Vacancy Survey, Microdata Files,” 2017. Via Citizen’s Committee for Children of New York, “Maintenance Deficiencies,” Keeping Track Online.

https://data.cccnewyork.org/data/table/1254/maintenance-deficiencies#1254/1443/25/a/a

[3] Where We Live NYC. “Housing Conditions,” City of New York. https://wherewelive.cityofnewyork.us/explore-data/housing-conditions/

[4] United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

[5] United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2015-2018 3-Year Average. Via Citizen’s Committee for Children of New York, “Child Poverty,” Keeping Track Online. https://data.cccnewyork.org/data/table/96/child-poverty#9/14/40/a/a

[6] United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

[7] United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

[8] Leland, John. ”She Had to Choose: Her Epileptic Patient or Her 7-Year-Old Daughter,” New York Times. March 22, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/22/nyregion/coronavirus-caregivers-nyc.html

[9] ibid

[10] New York State Department of Health. “New York State Asthma Surveillance Summary Report,” Table 6-1: Asthma Emergency Department Visit Rate per 10,000 Residents. October 2013. https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/ny_asthma/pdf/2013_asthma_surveillance_summary_report.pdf

[11] New York City Department of Health and Mental Health. “Environment & Health Data Portal,” 2018. http://a816-dohbesp.nyc.gov/IndicatorPublic/VisualizationData.aspx?id=2383,4466a0,11,Summarize

[12] Friedman, Lisa. ”New Research Links Air Pollution to Higher Coronavirus Death Rates,” New York Times. April 7, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/07/climate/air-pollution-coronavirus-covid.html

[13] Department of Health and Mental Health. ”The Public Health Impacts of PM2.5 from Traffic Air Pollution,” City of New York. http://a816-dohbesp.nyc.gov/IndicatorPublic/traffic/index.html