Section I: Executive Summary

On July 30, 2022, New York City (NYC) declared an emergency in response to the spread of the monkeypox virus (MPV), for which 150,000 residents were estimated by the City’s Health Commissioner to be at risk. Just days prior, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) contacted the Comptroller’s Office and City Law Department for permission to use an emergency procurement in its response. Contracted vendors were active in communities throughout the City within a month of the emergency declaration helping to prevent further spread. Less than a year later, a free-standing parking garage located at 57 Ann Street in Lower Manhattan collapsed, killing one person and injuring five others. After securing same-day approval from the Comptroller’s Office and Law Department to use the emergency procurement method, HPD hired Contractors less than 48 hours later to mitigate the risk to adjacent buildings and the surrounding area.

In emergency situations like the examples above, New Yorkers rely on the City to act as quickly as possible to avoid or mitigate an unforeseen danger to life, safety, property, or a necessary service. In those situations, agencies that are already working hard to expeditiously and effectively provide critical services for the public are often challenged to reorient resources much more quickly. To that end, the Emergency Procurement method is a valuable tool that can enable the City to immediately procure and address a serious need for required goods or services that cannot otherwise be met through normal procurement methods. Authorized by sections 315 of the NYC Charter, and section 3-06 of the Procurement Policy Board (PPB) Rules, emergency procurements enable the City to accelerate the sourcing of vendors to meet its emergency needs.

Emergency procurements must be used within the limited purpose outlined in the Charter and PPB Rules: to procure only materials or services needed to avoid or mitigate the danger to life, safety, property, or a necessary service. Even then, emergency procurements should only be used when other procurement methods are not possible – because emergency contracting brings greater risk of transparency, equity and cost issues.

As noted in our July 3, 2023 letter on Cost Containment in Emergency Contracts to all City agencies, emergency contracting is often more expensive than competitive procurement methods since time-strapped agencies cannot wait for more competitive bidders when goods and services are urgently needed. In addition, to expedite the procurement of goods and services, emergency procurements are exempt from certain transparency and accountability procedures that exist for other contracting methods. Moreover, vendors that might otherwise compete for and support the City’s emergency needs face additional barriers to entry, which further limits competition and can drive up costs.

The ideal emergency procurement system exists alongside robust risk assessment and planning mechanisms, so that the City does not have to rely on emergency contracts if its needs can be met by other means. When an emergency procurement cannot be avoided, City agencies involved in every aspect of the procurement process should work together to expedite the advancement of contracts. Agencies must also ensure that there is public transparency into emergency vendors and subcontractors, and that the selected vendors have the requisite expertise and wherewithal to perform as required under their contracts. Accordingly, the recommendations in this report are intended to improve efficiencies in City contracting and enable agencies to best meet our Charter and PPB requirements.

Key Findings

- Delays in the submission of critical information impedes proper and timely oversight reviews.[1]

- Agencies are not doing enough to ensure that prime vendors and subcontractors have been properly vetted, tracked, and evaluated.

- Vendors seeking to compete for and provide emergency goods and services face high barriers.

- Emergency contracts are not subject to the same procurement laws, rules, regulations, and agreements as other methods.

Recommendations

- Integrate risk assessments and data driven forecasting tools into procurement planning.

- Transition goods and services provided under emergency contracts to a competitively sourced contract whenever possible.

- Strengthen accountability for vendor integrity and performance evaluation reviews.

- Reform emergency procurement rules and procedures to achieve more accountability.

Data and Methodology

Unlike contracts procured via other methods, emergency procurements do not have to be registered to be legally effective.[2] Instead of a registration date, this Report refers to the date when an emergency contract filing is reflected in the City’s Financial Management System (FMS). Since FMS is the vehicle by which the City encumbers contract funds, such approvals are necessary for agencies to release payments to emergency vendors. The findings and recommendations contained within this report were developed in accordance with an analysis of 292 new emergency contracts and task orders where filings were reflected in FMS between January 1, 2022, and September 30, 2023.[3] We also analyzed contract management actions that occur throughout the life of a contract, including Payment Information Portal (PIP) approved subcontract records and performance evaluations logged in PASSPort.[4]

Nineteen agencies filed new emergency contracts and task orders valued at over $1.7 billion during the lookback period. While the HPD, which is tasked with hiring contractors to conduct emergency building demolitions, remains the largest driver of the number of emergency procurements in terms of volume, the New York City Department of Homeless Services (DHS) holds the largest share of emergency procurements in terms of dollar value. This is because DHS, whose agency mission is to provide temporary shelter for those in need, is leading the City’s contracting for emergency shelter services for newly arrived asylum seekers. Table 1 provides a breakdown of contract volume and value by agency.

Table 1: Volume and Value of Emergency Contracts by Agency[5]

| Agency | # of Emergency Contracts | Total Contract Value[6] |

| ACS | 1 | $158,691 |

| DCAS | 4 | $2,858,412 |

| DDC | 10 | $123,474,668 |

| DEP | 4 | $21,429,666 |

| DHS | 57 | $753,482,626 |

| DOB | 1 | $630,000 |

| DOC | 6 | $29,447,180 |

| DOHMH | 44 | $14,666,040 |

| DOI | 1 | $6,890,040 |

| DOP | 1 | $500,000 |

| SBS | 1 | $30,000,000 |

| DPR | 1 | $1,196,183 |

| DSS | 2 | $14,947,988 |

| DYCD | 1 | $2,233,301 |

| HPD | 146 | $509,645,202 |

| HRO | 5 | $47,992,767 |

| NYPD | 1 | $5,063,812 |

| NYCEM | 4 | $137,454,406 |

| OTI | 2 | $29,072,865 |

| Grand Total | 292 | $1,731,143,847 |

Primer on Emergency Contracts[7]

When circumstances arise that threaten life, safety, property, or necessary services and cannot be remediated through default procurement methods, the PPB Rules and City Charter enable agencies to accelerate the procurement of goods and services through the emergency procurement method.[8] Key features of the emergency procurement method include but are not limited to:

- Awards can be made more quickly, allowing work to begin sooner. Agencies can select a vendor for an emergency procurement any time after receiving approval to utilize the method from the Comptroller’s Office and the New York City Law Department (Law Department).[9] Since emergency procurements do not require registration to go into effect, vendors can begin work much sooner than they could under other procurement methods.

- Competition can be limited so that agencies are able to select a vendor more quickly. Agencies are required to seek only as much competition when selecting a vendor for an emergency procurement as is practicable given the nature of the emergency.[10]

- Emergency procurements are not bound by the same procurement procedures and requirements as other methods. As this report discusses in greater detail in Section II, emergency procurements are not subject to pre-solicitation reviews, notice of solicitation requirements, vendor protests, and certain public hearing requirements.[11] Emergency procurement vendors are not required to file disclosures in PASSPort as early as those awarded against other methods.[12] They are also not subject to Project Labor Agreements (PLAs), Local Law 63 scheduling, or M/WBE participation goals pursuant to LL179.[13] Finally, while agencies are still required to submit emergency contracts to the Comptroller’s office, registration is not required for the contract to be legally effective.[14]

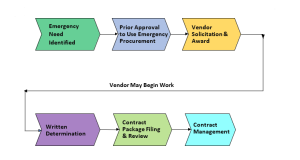

Emergency Contract Life Cycle (Prior Approval through Contract Management)

When there is an emergency situation that cannot be mitigated through the use of normal procurement methods, emergency contracts are advanced and managed through the following phases:

- Emergency Need Identified: As previously discussed, the Charter and PPB Rules only sanction the use of an emergency procurement to avoid or mitigate an unforeseen danger to life, safety, property, or a necessary service. However, even in such circumstances, the Agency Chief Contracting Officer (ACCO) must consider whether the need can be met through an existing contract, or through any other procurement method.

- Prior Approval: Agencies must receive “Prior Approval” from both the Comptroller’s Office and the Law Department, who confirm that the situation warrants an emergency procurement and grants permission to the agency to use the emergency procurement [15] In seeking this approval, agencies must describe the threat that exists to life, safety, property or a necessary service, and why the resulting procurement need cannot be met through normal procurement methods. As stated earlier, emergency procurements must be limited to the procurement of only those goods or services necessary to avoid or mitigate the emergency situation (i.e., emergency procurements are not intended to be long-term contracting solutions). For this Office to effectively evaluate the appropriateness of an emergency procurement request, agencies may be asked to provide details about the scope of the contract, the estimated cost, and the anticipated level of competition that will be used to source a vendor. The goal of this inquiry is to verify that the City stays within the parameters set forth by the Charter and PPB Rules when using the emergency procurement method.[16]

- Vendor Solicitation and Award: Since the emergency procurement method is designed to help the City respond to an emergency quickly, the level of competition sought by the contracting agency can be constrained to what is practicable under the circumstances.[17] Some agencies maintain pre-qualified vendor lists (PQVLs) to support common emergency needs, which can be solicited for competitive bids in a timely manner. Other agencies draw from preexisting non-emergency vendor pools associated with existing on-call requirements contracts that cover similar goods and services required by an emergency. In other instances, agencies may only solicit a quote from one or two vendors. No matter the selection method, vendors are legally authorized to begin working immediately after they are awarded (and Prior Approval has been granted). In all cases, agencies still have the obligation to ensure that vendors have the requisite business integrity to justify award of public dollars.

- Written Determination: Agencies must submit a Written Determination, which formally outlines the basis for the emergency and the selection of the vendor, to the Comptroller and Law Department for approval at the earliest practicable time.[18] Such determinations must also include a list of goods, services, or construction being procured; contract prices; the names of solicited vendors; and the past performance history of the awarded vendor. The Written Determination must also be sent to the City Council within fifteen days of award.[19]

- Contract Package Filing and Review: Agencies are required to file a contract package with the Comptroller within 30 days of an emergency contract award.[20] Such packages are subject to an audit of the procedures utilized in the advancement of, and the basis for, a given emergency Various permits, approvals, or clearances that are outside of the procurement process may be required by agencies such as OMB, DOI, DOHMH, DOB, PDC, LPC before an agency can submit a given contract to this Office.

- Contract Management: In addition to other standard contract functions, agencies are responsible for approving subcontractors requested by prime vendors and for conducting performance evaluations on vendors that were awarded emergency contracts.[21] Agencies must also publish a Notice of Award in the City Record after the contract has been implemented if it exceeds small purchase limits.[22]

Chart 1 presents a visual reflecting the phases of the emergency procurement Contract Life Cycle.

Chart 1: Phases of the Emergency Procurement Contract Life Cycle[23]

Section II: Findings

Section II expands on the findings summarized in the Executive Summary.

Delays in the Submission of Critical Information Impedes Proper and Timely Oversight Reviews

To the nimbleness afforded to contracting agencies in emergency situations with important oversight functions, the Charter and PPB Rules require that they submit detailed information about the award earlier in the process than is typically required via a Written Determination.[24] Agencies must also submit emergency contract packages to the Comptroller’s Office as soon as possible for a review of procedures, and to confirm the terms align with what was proposed in the Prior Approval request and outlined in the Written Determination. Timely submission of these documents is critical to ensure that the Bureau of Contract Administration can review and confirm that the contracting agency did not abuse the scope of the emergency procurement and that it contracted with a vendor that has the requisite business integrity to be awarded public dollars. However, the specific time frames set forth in the Charter and PPB rules that govern the timing of these submissions are vague, which results in unjustified delays that do not align with the spirit of the requirements and hinders the ability of this Office to provide the timely and requisite oversight that the public deserves and expects. This Office’s Charter-mandated contract review remains the only part of the procurement process to have a specific, clearly defined timeframe.[25]

In addition to delaying important reviews, the untimely production of Written Determinations and contract packages can leave vendors unsure of their operational requirements and agencies poorly equipped to monitor vendor performance. Vendors are often asked to support emergencies without the surety of contractually defined parameters for their work. Meanwhile, the procuring agencies cannot hold vendors accountable to specified contract terms until well after the emergency work has begun.

Written Determination Submissions[26]

Section 3-06(e)(3) of the PPB Rules lists various details that agencies must provide in a Written Determination, including a list of goods, services, or construction being procured; contract prices; the names of solicited vendors; and the past performance history of the awarded vendor. Both the Charter and PPB Rules require that agencies submit the Written Determination to the Comptroller and Law Department for approval as soon as possible.[27] In practice, most submissions to this Office are not timely and occur months after the start of the contract term, when an agency should reasonably possess all the information required for the Written Determination.

Chart 2 illustrates the share of Written Determinations received by this Office relative to the contract start date. Of the 292 emergency contracts in this dataset, 20% of Written Determinations were submitted over three months after the contract start date.

Chart 2: Written Determination Submission Relative to Contract Start Date[28]

No agency managing large numbers of emergency procurements submitted even half of their Written Determinations within fifteen days of the contract start. Of agencies overseeing at least 40 emergency contracts in our lookback period, HPD was the most successful by submitting 35.62% of its Written Determinations by this milestone. This is especially notable given that they manage the most emergency contracts of any agency. DHS and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) submitted far fewer Written Determinations within fifteen days of contract start (17.54% and 6.82% respectively). While noting that they filed few emergency contracts, DCAS, DDC, and HRO submitted most of their Written Determinations within fifteen days of the contract start.[29]

Contract Submissions

The requirement to register a contract before it becomes effective is waived for emergency procurements under the PPB Rules and Charter, however agencies are required to submit a copy of the contract for an audit of the procedures and the emergency’s basis within 30 days of award.[30] This is a critical mechanism to ensure that the terms of the City’s contract with a vendor match what was previously approved by this Office. As Chart 3 below shows, nearly 85% of emergency contracts in our dataset were filed with this Office well after 30 days of the contract start. As previously noted, vendors have already been awarded the contract and commenced services by the contract start milestone.

Chart 3: Submission Relative to Contract Start Date

Contract terms, conditions and scope are what agencies use to hold vendors accountable. Despite this, agencies and vendors can go months or longer before a contract has been executed and a corresponding contract package has been assembled and submitted to this Office. For instance, an HPD contract awarded to the United Jewish Council of the East Side Inc. for a housing navigator program was not filed with the Comptroller until 497 days after the contract start.[31]

In another example, the Department of Small Business Services () requested prior approval to utilize the emergency procurement method on May 13, 2021, relating to the need for emergency economic resiliency programming amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. This Office provided approval a day later, but over seventeen months elapsed before SBS submitted a Written Determination. In fact, the Written Determination was submitted after the contract package, only after this Office uncovered the agency’s lack of compliance during a review of procedural requisites.[32]

Agencies Are Not Doing Enough to Ensure That Vendors and Subcontractors Have Been Properly Vetted, Tracked, and Evaluated

The approval to use an emergency procurement method does not exempt agencies from the responsibility to vet vendors and subcontractors or to conduct required performance evaluations. However, since these contracts tend to be for shorter durations by nature, it is often the case that such requirements are not happening quickly enough, if at all.

Vetting Vendors

When making any new emergency contract award, agencies must ensure that prospective vendors and subcontractors have the requisite expertise and wherewithal to perform as required. Failing to properly vet a prospective vendor can leave the City doing business with an entity that does not have sufficient integrity to justify the award of public dollars, or is otherwise unable to meet the contract requirements. For instance, on September 5, 2023, the Comptroller’s office returned a $432 million HPD emergency contract with Rapid Reliable Testing NY, LLC over concerns inclusive of the vendor’s lack of experience in providing temporary housing and support services and the agency’s process for selecting this vendor for the award.[33] Much of the information that caused concern was uncovered during our review of the contract package , more than three months after the contract start date.[34]

Agencies entering an emergency procurement may not have access to as much vendor information by the contract start as they would under another procurement method. In order reduce delays in the delivery of essential goods and services, emergency procurement vendors are not required to submit disclosures in PASSport until after the contract has been filed, which is well after work has begun. [35] These disclosures provide agencies with crucial information regarding both prime and subcontractors, as well as their principal owners and officers. They also play an important role in enabling the agency to confirm a vendor’s responsibility, typically before work begins, as required by PPB Rules.

Subcontract Approvals

Although it is common for contracts to utilize one or more subcontractors, most agencies are not reportingin PIP, which is the system of record for related approvals and payments. Agencies may be compliant with applicable guidelines, but until these records are reflected in PIP there is insufficient detail for oversight agencies to confirm that agencies are aware of, vetting, and approving subcontractors that are selected to work on emergency procurement contracts. There is also no transparency into whether prime vendors are properly recording payments made to subcontractors. Among the seventeen agencies with emergency procurement contracts in our dataset, only eight had recorded at least one approved subcontractor in PIP. Relatedly, of the 292 contracts in our dataset, only 73 were linked with at least one approved subcontractor in PIP.

These figures reflect a significant underreporting of subcontractors that are supporting emergency work in NYC. For instance, this Office requested that DHS provide the names of associated subcontractors when filing emergency asylum seeker shelter contracts. Of the 51 contracts where DHS listed at least one subcontractor within the lookback period, only twelve had one or more approved subcontracts in PIP. In one specific case, DHS reported to this office that there were five distinct subcontractors associated with an asylum shelter managed by Highland Park Community Development Corp, but none are recorded in PIP.[36]

Table 2 provides a breakdown of contracts with PIP-approved subcontract records, by agency.

Table 2: Emergency Procurement Contracts with PIP-Approved Subcontracts, by Agency

| Agency | # of Contracts with PIP Approved Subcontracts | Total Emergency Contracts |

| ACS | 0 | 1 |

| DCAS | 0 | 4 |

| DDC | 7 | 10 |

| DEP | 2 | 4 |

| DHS | 12 | 57 |

| DOB | 0 | 1 |

| DOC | 1 | 6 |

| DOHMH | 0 | 44 |

| DOI | 0 | 1 |

| DOP | 0 | 1 |

| SBS | 0 | 1 |

| DPR | 1 | 1 |

| DSS | 0 | 2 |

| DYCD | 0 | 1 |

| HPD | 48 | 146 |

| HRO | 0 | 5 |

| NYPD | 1 | 1 |

| NYCEM | 1 | 4 |

| OTI | 0 | 2 |

| Grand Total | 73 | 292 |

Among the agencies with emergency procurements discussed in this report, HPD is the largest contributor of emergency subcontractor records in PIP. HPD was responsible for 239 of 315 (75.87%) total subcontract records entered in PIP against just 48 contracts. This Office is unable to verify how many subcontracts are associated with the other , against which there were no approved records in PIP.

As noted in our FY22 Annual Report on M/WBE Procurement, the lack of reporting in PIP stems from the fact that the City’s subcontracting ecosystem is still largely paper-based, with most required steps still occurring outside of electronic systems. City procurement rules and contract conditions specify that each subcontractor must be approved by the contracting agency before starting work.[37] To account for the reality that City contracts are often filed after the contract work has already started, the City has created a preliminary approval process that allows prime vendors to front-load subcontractor approvals. The preliminary approval process obligates prime vendors to complete and submit a paper Subcontractor Approval Form (SAF) to the contracting agency for an offline review, outside of a centralized system. The agency’s review of the paper SAF is often protracted, and sometimes does not happen at all.

Since many of the validation activities also occur offline and are not directly tied to contract management activities in a system, contracting agencies, prime vendors, and subcontractors can face difficulty interacting with each other in a meaningful, transparent fashion. This lack of reporting also reduces the public’s transparency into which businesses have been tasked with supporting the City’s emergency response.

Performance Evaluations

PPB rules require agencies to evaluate vendor performance on an annual basis to determine if they met the requirements of the contract.[38] Given the relatively short durations of emergency contracts, agencies typically conduct performance evaluations of emergency procurements only after the contract has expired. This is the case even though PPB rules require that evaluations be completed “sufficiently far in advance of the end of the contract term to determine whether an existing contract should be extended, renewed, terminated, or allowed to lapse.”[39] This is particularly critical for emergency procurements in instances where agencies are deciding if an emergency contract should be extended or when other agencies are considering vendors for an emergency procurement. In practice, agencies are not finalizing these performance evaluations in a timely manner.

As of September 2023, only 58 of the 292 contracts in our dataset (19.86%) had performance evaluations finalized in PASSPort.[40] Most of these evaluations were entered more than 30 days after the original contract expiration date. There were no performance evaluation records for the remaining 234 contracts in our dataset, including for 114 contracts that surpassed their original contract expiration date. Chart 4 provides a breakdown of performance evaluation status relative to the contract end date.

Chart 4: Status in PASSPort, Relative to Contract End Date:[41]

Of the 292 contracts covered in this Report, 174 had contract start dates prior to September 30, 2022 (one year before the end of our lookback period). None of these 174 contracts had performance evaluation records finalized in PASSPort within a year of their contract start date as required by the PPB Rules.[42] All 58 contracts with evaluations were entered more than a year after their contract start dates, while 116 contracts were still missing performance evaluation records. For instance, HPD had yet to record a performance evaluation for a contract with GN Construction Inc. that had a contract start date of January 30, 2020.[43]

Vendors Seeking to Compete for and Provide Emergency Goods and Services Face High Barriers

The City’s onerous and lengthy procurement process has created considerable processing delays that hinder the ability of businesses, especially nonprofits and M/WBEs, to get paid on time and sustain and grow their businesses. The emergency procurement process, due to its unpredictable and urgent nature, can make it especially difficult for nonprofits and M/WBEs to fairly compete for these opportunities. In FY23, the average emergency contract was filed with this Office, thereby allowing for the vendors to be paid, 144 days (nearly 5 months) after the start of the contract term.[44] Vendors pursuing emergency contracting opportunities are expected to provide the City with goods, services, or construction without guarantee of timely pay. An agency’s decision to utilize this procurement method may be discouraging (or even disqualifying) for M/WBEs, nonprofits and small vendors that might lack sufficient working capital and may have a more challenging time borrowing from traditional lending institutions. Since the terms and conditions associated with an emergency procurement may not always be clear at the outset of an emergency, M/WBEs and small businesses may have a harder time demonstrating their ability to adapt to evolving needs, relative to larger firms.

The City’s M/WBE Program excludes large areas of City contracting including emergency procurements.[45] Even absent a policy directive to engage with M/WBEs, the laws governing the program mandates agencies to conduct outreach encouraging M/WBEs to compete for emergency contracts.[46] Most recently, on August 8, 2023, Mayor Eric Adams issued Executive Order 34 (“EO 34”) to encourage better accountability and outcomes for M/WBE vendors.[47] Among other mandates, the new EO requires mayoral agencies to consider at least one quote from an M/WBE vendor on all emergency procurements.

Enforcement of this EO is needed along with other strategies to improve M/WBE participation given that M/WBEs were awarded just 15% (45 of 292) of the emergency contracts during our lookback period, amounting to only 3.45% of the total emergency procurement value. While the City’s asylum-seeker response has increased the share of non-profit prime vendors involved in emergency contracting (30% of contracts reflecting 40% of the emergency procurement value in our dataset), the M/WBE participation rate is still low even after removing these M/WBE ineligible contracts from the analysis (22% of contracts reflecting under 6% of emergency procurement value). Chart 5 displays the share of emergency contract value awarded to M/WBE prime vendors.

Chart 5: Emergency Contracts Value by M/WBE Prime Category

As noted in our previous finding, the available subcontractor data in PIP is incomplete, which makes it difficult to draw broad conclusions from an analysis of what was reported.[48] Of the available data, M/WBEs make up 42% of approved subcontracts and 43% of the total subcontract value ($55.96 million of $129.65 million) Table 3 provides a breakdown by of PIP-approved subcontract value by M/WBE category.

Table 3: PIP-Approved Subcontract Value by M/WBE Category

| M/WBE Category | Total Subcontract Value | Share of Subcontract Value |

| Asian M/WBEs | $12,870,608 | 9.93% |

| Black M/WBEs | $1,341,628 | 1.03% |

| Hispanic M/WBEs | $6,513,858 | 5.02% |

| White WBEs[49] | $35,232,723 | 27.18% |

| Non-Certified | $73,690,115 | 56.84% |

| Grand Total | $129,648,932 | 100.00% |

Emergency Procurements Are Not Subject to the Same Laws, Rules, Regulations, and Agreements as Other Methods

To provide the City with the flexibility it needs to respond quickly in emergency situations, the emergency procurement method is exempt from many laws, rules, procedures, and processes governing procurement and contracting, which are otherwise designed to make City procurement open, competitive, and inclusive. Accordingly, emergency procurements should only be used when absolutely necessary. The following is a list of procedures and requirements from which emergency procurements are exempt, or that have been otherwise modified for emergency procurements to help expedite the advancement of the contract.[50]

- Pre-solicitation reviews[51]

- City Record notice of solicitation requirements[52]

- Contract public hearings (including public notices)[53]

- Vendor ability to appeal non-responsiveness and non-responsibility determinations

- Vendor protests[54]

- Vendor PASSPort questionnaires do not have to be entered until 30 days after the contract has been filed in FMS[55]

- LL63 requirements[56]

- LL174 M/WBE Participation Goals[57]

- Project Labor Agreements for construction contracts

In addition to the items above, the City’s “Fair Share” Charter requirements and rules are silent on whether or how they apply to emergency procurements, which the City has increasingly relied upon to site shelters, sanctuary sites, and Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Centers (HERRCs) to provide critical services to new arrivals seeking asylum. “Fair Share” requirements were adopted in 1989 to encourage the City to make a concerted effort to ensure that communities are both getting their fair share of amenities like parks and libraries and doing their fair share to confront and help solve citywide problems like homelessness. Fair Share applies to a long list of City facility types, including contracted City facilities and services such as homeless shelters, and requires the City to produce a series of analyses and disclosures when siting new facilities to assess neighborhood impact and distributional fairness. As of November 2023, the City had not produced Fair Share analyses for any of the City’s 20 HERRCs or 129 DHS-managed shelter sites.[58]

Section III: Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Integrate Risk Assessments and Data Driven Forecasting Tools into Procurement Planning

The City should expand its utilization of non-emergency procurement tools, and other proactive means, to prepare for emergencies in more transparent, equitable, and cost-effective ways. To support this goal, we recommend that the City assemble an interdisciplinary team made up of procurement professionals, data analysts, and emergency response experts to identify goods, services, or construction that may be needed in future emergencies. By elevating such needs ahead of time, agencies would be better equipped to respond in emergency situations while relying on emergency procurements less.

Canvass Agencies for Relevant Citywide Contracts

Agencies can also look at risk assessment findings, and their own emergency contracting history, to identify gaps that may be filled by procuring new citywide master agreements. For instance, from December of 2022 through June of 2023, DOHMH filed 28 new emergency contracts for community engagement services relating to MPV distribution. These were emergency procurements with some of the same vendors that DOHMH had not long before contracted on an emergency basis for community engagement services relating to COVID. With better planning, DOHMH may have anticipated the need for community engagement services for a health-related pandemic, given the prior occurrences. As of the date of this report, it does not appear that DOHMH has initiated a procurement strategy to put in place long-term community engagement services that can be deployed if the City needs to manage another health pandemic.[61]

Build New Pre-Qualified Vendor Lists (PQVLs)

When an emergency procurement cannot be avoided, agencies should expand their use of PQVLs to improve efficiency and boost competition when soliciting emergency contracts. PQVLs create efficiencies by offering opportunities to vendors confirmed in advance to have requisite experience, or otherwise be capable of meeting the City’s needs.[62] Expanding their use would require agencies to evaluate prior emergency procurements purchases and to look for additional vendors that provide frequently needed goods, services, and construction. HPD already uses PQVLs to solicit competitive bids for emergency demolition projects, which are the largest drivers of their emergency procurements, and in doing so, is able to realize better competition.

Moreover, this Office continues to support the recommendation of the Capital Process Reform Task Force to increase the use of M/WBE exclusive prequalified lists.[63] Some agencies have successfully utilized both types of PQVLs, but wider adoption of PQVLs is needed to direct higher-dollar-value contracting opportunities to eligible M/WBEs, particularly targeting underutilized M/WBE Categories. In addition to the utilization advantages, agencies may also establish PQVLs that, as a condition of prequalification, require a significant portion of any awarded contract funds be spent with M/WBEs (either as prime vendors or through subcontracting).

Provide Guidance to Agencies on Additional Alternative Sourcing Methods

Agencies should also explore other non-emergency sourcing methods to make emergency purchases quickly and inexpensively before turning to emergency procurements. For instance, section 162 of New York State Finance Law allocates a preferred source status to vendors which exempts them from competitive procurement requirements in the interest of advancing special social and economic goals.[64] Agencies must utilize preferred sources for certain procurements where they have been designated by the State.

Additionally, agencies can currently utilize the M/WBE Noncompetitive Small Purchase (NCSP) method to make purchases up to $1 million without a formal competitive process. This is one of the City’s most effective tools in driving prime contract awards to M/WBEs. In addition, this method is designed to move contracts forward more quickly than other competitive procurement methods and is available for agencies to leverage when procuring goods, services and construction. On June 6, 2023, the New York State Senate passed legislation that will amend the City Charter to increase the dollar threshold for the M/WBE NCSP method from $1 million to $1.5 million. Once signed by the Governor, this increased threshold will allow agencies to utilize this expedited method for more purchases.

This Office and the mayoral Administration have also encouraged City agencies to achieve broader and higher dollar use of this method by shifting away from long-standing contracting practices and methods that may not always result in strong M/WBE participation. To that end, the New York City Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) was recently approved to register certain goods contracts procured through the M/WBE NCSP method under the Master Agreement (MA1) transaction code in the City’s Financial Management System (FMS). This new approach will further enable the City to partner with qualified M/WBEs to replenish goods to DCAS’ Central Storehouse and will allow agencies to make faster orders and more cost-effective purchases of essential goods. Whenever possible, agencies should not only maximize use of these Master Agreements before turning to emergency purchases, but also examine their existing portfolio to identify ways to improve M/WBE participation while also entering into long-term contracting solutions.

Recommendation 2: Transition Goods, Services, Or Construction Provided Under Emergency Contracts to a Competitively Sourced Contract Whenever Possible

City agencies filed more than 130 extensions to emergency contracts that had previously received Prior Approval between January 1, 2022, and September 30, 2023. While there may be several valid reasons to extend an emergency procurement (for example, delays in construction timelines), the City should proactively plan to transition projects from emergency procurements to more competitively and transparently procured contracts. Table 4 breaks down the share of emergency contract modification by length of the term extension.

Table 4: Contract Extensions Filed Between January 1, 2022, and September 30, 2023

| Contract Extension Term | # of Mods | % Share of Mods |

| 1-30 days longer | 11 | 8.03% |

| 31-90 days longer | 15 | 10.95% |

| 91-180 days longer | 29 | 21.17% |

| 181-365 days longer | 66 | 48.18% |

| More than 1 year longer | 16 | 11.68% |

| Grand Total | 137 | 100.00% |

As early as when an agency first solicits a new emergency contract, it should consider whether the sought-after work, if still needed in the future, can be transitioned to a new contract under an alternative sourcing method. Not only do such transitions offer the City an opportunity to secure more competitive pricing, but the replacement contracts will be subject to transparency and accountability provisions for which emergency procurements are exempt. Additionally, by frontloading considerations about the duration of an emergency need and the feasibility of transitioning that need to an alternative method, agencies can make more informed decisions about what amount of competition to seek when making the initial emergency award.

Recommendation 3: Strengthen Accountability for Vendor Integrity and Performance Evaluation Reviews

Irrespective of the sourcing method, agencies are mandated to ensure that awarded prime vendors and subcontractors are operating in good legal standing, and that they have the requisite experience and capacity to meet the City’s needs. This is especially true in the context of emergency procurements where the City is expending public dollars to address an emergency where lives may depend on the quality of the City’s response.

At all levels, agency staff involved in the vendor selection process must be sufficiently trained to conduct thorough vendor reviews, not only with an eye towards ensuring integrity, but financial capacity and relevant experience. To aid agencies with this responsibility, the City must proactively encourage vendors to submit PASSPort disclosure questionnaires at the earliest entry points to doing business with the City. Depending on the situation, this may be when a vendor first enrolls in PASSPort, when they become certified by SBS as an M/WBE, or when they establish a business profile in FMS or PIP. In addition to avoiding contracting delays, earlier PASSPort disclosures provide crucial information regarding both prime and subcontractors, as well as their principal owners and officers, that when used in conjunction with other vetting tools, can provide agencies with greater insight into a vendor’s background.[65]

Relatedly, the City should prioritize addressing the lack of subcontractor tracking and reporting in PIP. This Office continues to advocate for the elimination of the paper-based subcontractor submission and review process and for the incorporation of the PIP subcontractor process into PASSPort with end-to-end functionality. An online platform that allows for document submission, review and approval steps, and information sharing would streamline subcontractor approvals so they could be recorded and available to the public before the end of a contract’s term. It would also allow the City to collect more reliable, trustworthy, and transparent data to monitor compliance, while providing oversight agencies with more surety that subcontractors were properly vetted.

[66] They should also occur more frequently than once annually given the relatively short duration of emergency contracts. Through the performance evaluation process, agencies would be able to increase oversight of, and support for, vendors that are often operating for months without a formal contract and codified operational requirements. Timelier completion of these evaluations would also ensure that other agencies have access to critical performance data sooner, which may be needed to inform their own procurement decisions.

Recommendation 4: Reform Emergency Procurement Rules and Procedures to Achieve Greater Accountability

While emergency procurements expedite the provision of emergency goods, services, and construction, the process to advance emergency contracts can be slow and inefficient. The City must streamline the emergency procurement process to reduce processing timelines and to make details about emergency contracts available sooner.

Some of the reasons for the City’s inability to submit Written Determinations and contract packages in a timely manner, in keeping with the spirit of the Charter and PPB rules, stem from textual ambiguities in the relevant statutes. For instance, the PPB Rules require that Written Determinations should be submitted to this Office and the NYC Law Department for approval at the “earliest practicable time,” a standard that has not been interpreted with consistency across agencies.[68] Updating the Charter and PPB rules to clarify these terms would encourage more predictability and compliance among agencies to meet the submission requirements that are already in place.

Beyond changes that would address timeliness, amending the PPB Rules would also give the Board an opportunity to assess whether they provide for sufficient transparency. For example, in setting forth the enumerated requirements of a Written Determination, the PPB Rules do not currently include critical procurement details such as the anticipated contract duration or the basis for a vendor’s responsibility determination, including the status of the vendor’s PASSPort disclosures. While an emergency may be a basis to allow for the late filing of a vendor’s disclosure forms under PPB §2-08(e)(3), such disclosures should be required sooner than the current standard, which is tied to the filing date of the contract in FMS. These details are needed by oversight agencies to ensure that agencies are using emergency procurements within the limited scope set by the Charter and PPB Rules, and that they are adequately vetting vendors before awarding them these critical contracts.

The Administration must also prioritize improvements to PASSPort and related systems that would enable agencies to more easily establish and process emergency contracts. Without these enhancements, agencies will continue to struggle with inefficient contract processing tools that currently fail to provide timely public access to emergency procurements information through systems such as PASSPort Public, which have otherwise been significant public transparency successes.

This Office has been an active participant since the Administration resumed convening the PPB and we look forward to continuing the work along with our fellow board members to amend the Rules to bring necessary clarity and reform to the procurement process. We are also open to working with our partners at the NYC Law Department and the Administration, on behalf of contracting agencies, to reform current processes for submitting, tracking, and approving emergency contract Prior Approval and Written Determination requests. Rather than have email be the primary mechanism by which these critical approvals are managed, a centralized system to house and process these requests would facilitate more timely submission of these documents to secure approval and better track and advance emergency procurements.

Section IV: Asylum Contracts

New York City has welcomed tens of thousands of asylum seekers since spring of 2022, entering into contracts across many agencies to provide shelter, meals, medical care, and legal assistance to new arrivals. This office 194 emergency and non-emergency contracts related to the City’s asylum response in the procurement pipeline as of July 31, 2023. A list of these contracts and related information is periodically refreshed on our Office website.[69]

From July 2022, when the City received Prior Approval to utilize the emergency procurement method to establish an arrival center and additional shelter facilities, through September 30, 2023, 74 related emergency contracts were filed with this Office and reflected in FMS.[70] As previously noted, DHS is leading other agencies in total contract value because it is leading the City’s contracting for emergency shelter services for newly arrived asylum seekers. The $1.38 billion in contract value for these asylum contracts represents nearly 80% of the total emergency procurement value in our dataset. Table 5 provides a breakdown of asylum contracts by volume and value across the contracting agencies.

Table 5: Emergency Asylum Contracts by Agency

| Agency | # of Emergency Contracts | Total Contract Value |

| DCAS | 1 | $2,000,000 |

| DDC | 6 | $1,161,869 |

| DHS | 57 | $753,482,626 |

| DOI | 1 | $6,890,040 |

| DSS | 2 | $14,947,988 |

| HPD | 2 | $432,240,000 |

| HRO | 2 | $7,932,767 |

| NYCEM | 1 | $135,000,000 |

| OTI | 2 | $29,072,865 |

| Grand Total | 74 | $1,382,728,155 |

Document Submission Trends

The timing of Written Determination submissions for asylum emergency procurements was generally on par relative to the larger share of emergency contracts in our dataset. Chart 6 provides a breakdown of Written Determination submissions relative to contract start dates, the point at which agencies reasonably should be aware of information required under section 3-06 of the PPB Rules. 27% of asylum Written Determinations were submitted within fifteen days of the contract start date, relative to 29% for emergency procurements overall.

Chart 6: Asylum Written Determination Submissions Relative to Contract Start Date

On the other hand, similar to the overall data set, a disproportionately low (27%) share of asylum contract packages were submitted within 30 days of the contract start Chart 7 provides a breakdown of contract package submissions relative to contract start dates.

Chart 7: Asylum Contract Submissions Relative to Contract Start Date

M/WBE Participation Trends

As is the case with the broader pool of emergency procurements in our lookback period, M/WBEs only make up a small portion of asylum contract awards and value. M/WBE prime vendors account for 5% (5 of 74) of emergency asylum contracts and just 2% of emergency procurement contract value. Chart 8 displays the share of emergency contract value awarded to M/WBE prime vendors.

Chart 8: Emergency Asylum Contract Value by M/WBE Category

Subcontracting

The lack of adequate enforcement and reporting of subcontractors holds true for asylum emergency procurement as well. City agencies have recorded subcontractor approvals for just 21% (16 of 74) of asylum related emergency contracts in PIP. As part of our post contract submission review, this Office learned that although DHS referenced subcontractors associated with 51 of its contracts in their package filings, only twelve of these contracts had at least one subcontract record in PIP.

Table 6: Emergency Asylum Contracts with PIP-Approved Subcontracts, by Agency

| Agency | # of Contracts with PIP Approved Subcontracts | # of Emergency Contracts |

| DCAS | 0 | 1 |

| DDC | 3 | 6 |

| DHS | 12 | 57 |

| DOI | 0 | 1 |

| DSS | 0 | 2 |

| HPD | 0 | 2 |

| HRO | 0 | 2 |

| NYCEM | 1 | 1 |

| OTI | 0 | 2 |

| Grand Total | 16 | 74 |

The 16 emergency contracts with at least one subcontractor record reflected in PIP, account for only 40 total approved subcontractors. As evidenced by the earlier DHS example, given the size and scope of many of these contracts, it is not unreasonable to assume that agencies are not reflecting all approved subcontractors in PIP. Unless and until these records are reflected in PIP, oversight agencies cannot confirm which subcontractors are working on emergency projects, what they are being paid, or even if agencies have properly vetted and approved them.

This Office has only the information recorded in PIP to rely upon when assessing the utilization of MWBE subcontractors. Based upon the total value ($87 million) of PIP-approved subcontract records, MWBE firms account for just 27% ($23.6 million). Table 7 provides a breakdown of emergency asylum subcontract value across M/WBE categories.

Table 7: Share of PIP-Approved Emergency Asylum Subcontract Value by M/WBE Category

| M/WBE Category | Subcontract Value | % Share of Value |

| Asian M/WBEs | $11,425,952 | 13.13% |

| Black M/WBEs | $68,226 | 0.08% |

| Hispanic M/WBEs | $5,552,283 | 6.38% |

| White WBEs | $6,608,075 | 7.59% |

| Non-Certified | $63,361,602 | 72.82% |

| Grand Total | $87,016,139 | 100.00% |

Performance Evaluations

Although the majority (59 of 74) of the emergency contracts related to the City’s asylum response have been operating for less than a year, there were no completed performance evaluation records in PASSPort for them. With dozens of extensions currently pending for DHS shelter contracts, the administration should prioritize the completion of associated evaluations as soon as possible.

Section V: Appendices

Appendix 1 – Key Sections of the NYC Charter

Section 315. Emergency procurement.

Notwithstanding the provisions of section three hundred twelve of this chapter, in the case of unforeseen danger to life, safety, property or a necessary service, an emergency procurement may be made with the prior approval of the comptroller and corporation counsel, provided that such procurement shall be made with such competition as is practicable under the circumstances, consistent with the provisions of section three hundred seventeen of this chapter. A written determination of the basis for the emergency and the selection of the contractor shall be placed in the agency contract file, and shall further be submitted to the council no later than fifteen days following contract award, and the determination or summary of such determination shall be included in the notice of the award of contract published pursuant to section three hundred twenty-five of this chapter.

Appendix 2 – Key Sections of the PPB Rules

Section 3-06 EMERGENCY PURCHASES.

- Definition of Emergency Conditions. An emergency condition is an unforeseen danger to life, safety, property, or a necessary service. The existence of such a condition creates an immediate and serious need for goods, services, or construction that cannot be met through normal procurement methods.

- Scope. An emergency procurement shall be limited to the procurement of those items necessary to avoid or mitigate serious danger to life, safety, property, or a necessary service.

- Authority to Make Emergency Purchases.

- Any agency may make an emergency procurement when an emergency arises and the agency’s resulting need cannot be met through normal procurement methods.

- The Agency shall obtain the prior approval of the Comptroller and the Corporation Counsel.

- The Agency shall submit at the earliest practicable time a determination of the basis of the emergency and the selection of the contractor, as set forth in Section 3-06(e)(3) of these Rules to the Comptroller and the Corporation Counsel for approval as soon as possible.

- Source Selection. The procedure used shall assure that the required items are procured in time to meet the emergency. Given this constraint, such competition as is possible and practicable shall be obtained.

- Public Notice and Filing Requirements. Solicitations in emergency procurements are subject to the following public notice and reporting requirements:

- Solicitations pursuant to a finding of emergency are not required to be published in the City Record.

- The agency shall publish notice of the award of the emergency contract in accordance with Section 3-06(f).

- A determination of the basis for the emergency and the selection of the vendor must be filed with the Corporation Counsel and the Comptroller, and must further be submitted to the City Council no later than fifteen days following the contract award. The determination must include:

- the date emergency first became known;

- a list of goods, services, and construction procured;

- the names of all vendors solicited;

- the basis of vendor selection;

- contract prices;

- the past performance history of the selected vendor;

- a listing of prior/related emergency contract; and

- PIN.

- Notice of Award.

-

- Notice of a contract award exceeding the small purchase limits shall be published at least once in the City Record, within fifteen calendar days after contract registration.

- Such notice shall include:

- summary determination of the basis for the emergency stated to be either a case of an unforeseen danger to life, safety, property, or a necessary service;

- agency name;

- PIN;

- title and/or brief description of the goods, services, or construction procured;

- name and address of the vendor;

- dollar value of the contract;

- procurement method by which the contract was let; and 100

- citation of the reason under Section 315 of the City Charter providing justification for the chosen method of procurement.

-

Appendix 3 – Emergency Contract Summaries by Agency Summaries by Agency

| Agency | # of Contracts | Total Contract Value | % Share of WDs Submitted Within 15 Days of CS | % Share of Contracts Submitted Within 30 Days of CS | # of Asylum Seeker Contracts | Value of Asylum Seeker Contracts |

| ACS | 1 | $158,691 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0 | $0 |

| DCAS | 4 | $2,858,412 | 75.00% | 25.00% | 1 | $2,000,000 |

| DDC | 10 | $123,474,668 | 70.00% | 80.00% | 6 | $1,161,869 |

| DEP | 4 | $21,429,666 | 25.00% | 0.00% | 0 | $0 |

| DHS | 57 | $753,482,626 | 17.54% | 15.79% | 57 | $753,482,626 |

| DOB | 1 | $630,000 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0 | $0 |

| DOC | 6 | $29,447,180 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0 | $0 |

| DOHMH | 44 | $14,666,040 | 6.82% | 2.27% | 0 | $0 |

| DOI | 1 | $6,890,040 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 1 | $6,890,040 |

| DOP | 1 | $500,000 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0 | $0 |

| DOSBS | 1 | $30,000,000 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 0 | $0 |

| DPR | 1 | $1,196,183 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 0 | $0 |

| DSS | 2 | $14,947,988 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 2 | $14,947,988 |

| DYCD | 1 | $2,233,301 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0 | $0 |

| HPD | 146 | $509,645,202 | 35.62% | 13.70% | 2 | $432,240,000 |

| HRO | 5 | $47,992,767 | 60.00% | 60.00% | 2 | $7,932,767 |

| NYPD | 1 | $5,063,812 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0 | $0 |

| OEM | 4 | $137,454,406 | 25.00% | 25.00% | 1 | $135,000,000 |

| OTI | 2 | $29,072,865 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 2 | $29,072,865 |

| Total | 292 | $1,731,143,847 | 28.42% | 15.75% | 74 | $1,382,728,155 |

Acknowledgements

Dan Roboff, Director of Procurement Research Analysis and Reporting, was the lead author of this report with support from Emerson Lazellari, Senior Data Analyst; Caleb Gruder, Summer Intern; Michael Raybetz, Summer Intern; James Leidy, CUNY Fellow; Kerri Nagorski, Director of Procurement Policy and Partnerships; Daphnie Agami, Senior Advisor and Counsel to the Deputy Comptroller; Michael D’Ambrosio, Assistant Comptroller for the Bureau of Contract Administration; and Charlette Hamamgian, Deputy Comptroller, Contracts and Procurement. The data analysis was led by Dan Roboff, with support from Emerson Lazellari, James Leidy, Caleb Gruder, and Michael Raybetz. Report design was completed by Archer Hutchinson, Graphic Designer.

Endnotes

[1] For the purposes of this report, “oversight agencies” refers to the Law Department and the Comptroller’s Office, which confirm Prior Approval requests and review Written Determinations pursuant to PPB § 3-06

[2] See NYC Charter §328(d)(1) and PPB § 2-12(e). However, agencies are required to submit a copy of the contract for an audit of the procedures and the emergency’s basis with 30 days of award.

[3] The analysis in this report is restricted to new contracts and task orders processed under award method 6 (Emergency Procurements) during the stated lookback period. Unless otherwise noted, emergency modifications filed during this period are not reflected in this report. Similarly, pending emergency actions were excluded from the analyses in this report unless they were approved in FMS within the lookback period. Contracts that were executed pursuant to E.E.O 101, and its successors, were excluded from this analysis. DOE’s emergency contracts are similarly processed outside PPB rules and were therefore excluded.

[4] PASSPort is the City of New York’s end-to-end digital procurement platform that manages every stage of the procurement process from vendor enrollment, to the solicitation of goods and services, to contract registration and management.

[5] Unless otherwise noted, all analyses in this Report refer to emergency contracts or subcontracts within the lookback period of January 1, 2022 through September 30, 2023.

[6] The award value of MMA1 contracts are not reflected in these totals as they represent contract capacity only. Instead, the award value of project task orders entered under these MMA1s are reflected.

[7] This primer outlines the emergency procurement process for agencies subject to PPB rules. Certain entities like the Department of Education and the Health and Hospitals Corporation are not subject to PPB rules and follow alternative procedures for soliciting and executing emergency contracts. This report also does not cover emergency contracts processed under suspension of PPB rules, as was the case under Emergency Executive Order 101 of 2020, and its successor orders.

[8] PPB § 3-06 (c); NYC Charter § 315

[9] NYC Charter § 315

[10] PPB § 3-06(d)

[11] PPB § 2-02(b), PPB § 2-10(a), PPB § 2-11(b)(1)(iii), PPB § 3-06(e)(1), and NYC Charter § 325(d)

[12] PPB § 2-08(e)(3)

[13] Refer to the NYC Contract Primer for more information about the procedures and requirements referenced in this paragraph. https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/contract-primer/#_ftnref8

[14] PPB § 2-12(e)(1)-(4) and NYC Charter § 328(d)(1)

[15] PPB § 3-06(c)(2)

[16] If the agency finds that a vendor can only be procured at an amount exceeding the value names in the initial approval, the agency must submit another request for approval by the Comptroller and Law Department.

[17] PPB § 3-06(d)

[18] PPB § 3-06(c)(3) and PPB § 3-06(e)(3)

[19] PPB § 3-06(e)(3) and NYC Charter §315 also stipulate that a written determination be submitted to the City Council within fifteen days of the contract award, although this body does not have the authority to approve or reject the determination. Measuring compliance with this requirement is beyond the scope of this Report.

[20] PPB § 2-12(e)(3)

[21] PPB § 4-01 and PPB § 4-13

[22] PPB § 3-06(f)(1)

[23] Although contract management is display as the final step in this life cycle, many related activities begin as soon at the vendor begins its work. For instance, agencies are responsible for vetting and approving subcontractors, and overseeing prime vendor compliance.

[24] NYC Charter §315, PPB §3-06(c)(3) and PPB §3-06(e)(3)

[25] NYC Charter §328(a). See also A Better Contract for New York: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/A-Better-Contract-for-New-York_Joint-Task-Force-Action-Memo-update.pdf

[26] Written Determination submissions are typically made over email, with a copy later included with the contract package. All Written Determination submission dates were extracted from a manual review each contract packages in the dataset.

[27] The Charter and PPB also require that Written Determinations be submitted to the City council within 15 days of an emergency contract award, however measuring compliance with this requirement is beyond the scope of this report.

[28] Chart 2 uses “WD” to abbreviate Written Determination and “CS” to abbreviate Contract Start

[29] DOI, DPR, and SBS each had a single contract in our dataset. All three submitted their Written Determinations within 15 days of the contract start as well.

[30] See PPB § 2-12(e). NYC Charter §328(d)(1) has a similar clause, but states that the agency shall submit the contract “as soon as is practicable”

[31] Contract CT1-806-20238807700

[32] Contract CT1-801-20238803578. Prior Approval was provided on May 31, 2021. Written Determination was submitted on September 29, 2022, six days after the contract package was filed (September 23, 2022)

[33] CT1-806-20248801671

[34] For more information, about this Office’s position on the Rapid Reliable contract, please refer to Comptroller Lander’s letter on the contract: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/letter-on-return-of-rapid-reliable-testing-ny-llc-contract-20248801671/ and Comptroller Lander’s testimony on Asylum Seeker Contracts: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/newsroom/comptroller-lander-delivers-testimony-on-asylum-seeker-contracts-before-the-city-council-committees-on-oversight-and-contracts/

[35] See PPB § 2-08(e)(3))

[36] CT1-071-20238806008. The reported subcontractors were Beacon Hill Staffing Group, LLC; Xclusive PC & IT Inc.; Clean City Laundry, Inc; Regina Caterer’s; and Universal Protection Services, LLC.

[37] PPB § 4-13(c)

[38] PPB § 4-01(a- c)

[39] PPB § 4-01(b)

[40] Procurement and Sourcing Solutions Portal (PASSPort) is the City of New York’s end-to-end digital procurement platform that manages every stage of the procurement process from vendor enrollment to the solicitation of goods and services, to contract registration and management.

[41] This chart uses the abbreviation “PE” for performance evaluation.

[42] PPB § 4-01(a- c)

[43] CT1-806- 20228801396

[44] As previously noted, the Charter requires the Comptroller’s office to complete its contract reviews within 30 days. The vast majority of these delays relate to the process before an emergency contract is submitted.

[45] The City’s MWBE program is currently governed by Section 6-129(b) of the N.Y.C. Administrative Code, which codifies Local Laws 174 (“LL 174”) and 176 (“LL 176”) enacted by the City Council in 2019

[46] N.Y.C. Admin Code §6-129 (h)(2)(a) – Agencies shall engage in outreach activities to encourage MBEs, WBEs and EBEs to compete for all facets of their procurement activities, including contracts awarded by negotiated acquisition, emergency and sole source contracts, and each agency shall seek to utilize MBEs, WBEs and/or EBEs for all types of goods, services and construction they procure.

[47] EO 34 builds upon a previous Executive Order 59 (”EO 59”) issued by Mayor deBlasio on July 28, 2020 that stated that agencies “shall not categorically exempt Emergency contracts from M/WBE participation goals, and shall instead, to the extent practicable in light of the nature of the procurement, follow the procedures set forth in Section 6-129(h) and (i) of the N.Y.C. Administrative Code to set goals for the contract.”

[48] Accounting for 239 of the 315 subcontract records, HPD is responsible for the majority of these PIP-approved reports.

[49] Note: A single subcontract to Gramercy Group Inc., a Caucasian Women Business Enterprise, is a significant driver of value, accounting for $24.78 million alone. The subcontract is associated with CT1-850- 20221411613, awarded to Liro Engineers Inc. For the emergency demolition of structures on Hart Island. The Gramercy subcontract accounts for over 90% of the value across eight PIP-approved subcontracts associated with this project. Two other WBEs, and one Black M/WBE were also awarded small subcontracts.

[50] Refer to the NYC Contract Primer for more information about the procedures and requirements referenced in this section. https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/contract-primer/#_ftnref8

[51] PPB § 2-02(b))

[52] NYC Charter § 325(d) and PPB § 3-06(e)(1). Note: Notices of Award are still required to be published within 15 days of filing in FMS

[53] PPB § 2-11(b)(1)(iii)

[54] PPB § 2-10(a))

[55] PPB § 2-08(e)(3)

[56] NYC Charter § 312(a)

[57] NYC Admin Code § 6-129(b)

[58] More information and analysis on the City’s Fair Shair requirements can be found on our website. This Office recently released a policy report on Fair Share: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/fair-share-siting-new-york-citys-municipal-facilities/ as well as an audit of the City’s compliance with Fair Share requirements: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/audit-report-on-new-york-citys-compliance-with-fair-share/

[59] PPB Rules §3-02(t), (j).

[60]DDC has successfully utilized multiple master agreements, such as MMA1-850-20228805268, a requirements contract for construction management services, to support the City’s emergency needs. Under the existing terms of the master agreement, DDC procured construct management services via a task order (CTA1-850- 20238804094) to support the establishment of Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Centers (HERRC) for asylum seekers.

[61] Following Superstorm Sandy, the Department of Design and Construction worked with NYCEM, oversight agencies, and other agency partners to establish the City’s On-Call Emergency Contract (OCEC) Program. This program, whose second generation is being led by NYCEM, centers around leveraging competitive procurement methods to pre-position contracts to provide support in critical areas of need during emergencies. The contract categories include but aren’t limited to construction services, debris removal, IT services, environmental testing, and other services that may be needed to support City operations for future emergencies. It can only be used following a City and/or State emergency declaration.

[62] NYC Charter §324

[63] In April 2022, then First Deputy Mayor Lorraine Grillo announced the development of a Capital Process Reform Task Force. The Comptroller’s Office is a proud and active member of the Task Force, which seeks to advance legislative and procedural changes in support of a more efficient and equitable capital process. The final set of immediate recommendations from this Task Force were published in January 2023.

[65] When vetting the information disclosed along with other sources for review, an agency may learn of inconsistencies or questionable disclosures made, which may result in the need for further review. While these disclosures are available in connection with most other procurement methods, this remains a large gap as it relates to EPs, which are typically high value contracts.

[66] PPB § 4-01(b) required performance evaluations to be completed “sufficiently far in advance of the end of the contract term to determine whether an existing contract should be extended, renewed, terminated, or allowed to lapse”

[67] PPB § 3-06(c)(3)

[68]NYC Charter § 315

[69] View the Comptroller’s landing page for Asylum Data here: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/services/for-the-public/accounting-for-asylum-seeker-services/overview/

[70] This figure does not capture non-emergency contracts that the city has utilized to support asylum seekers. Pending actions are also not reflected in these totals.