Safe and Supportive Schools: A Plan to Improve School Climate and Safety in NYC

Executive Summary

At a time when the nation is deeply embroiled in concerns around school safety, it is not surprising that many strategies for creating safe school environments are under renewed consideration – everything from providing more mental health services to students, to expanded school lockdown drills, to extreme responses calling for arming teachers with guns. The horrific school shooting in Parkland, Florida served as a catalyst to this debate, forcing communities across the country to consider how best to safeguard their students. It is an important and overdue conversation – and one that New York City should seize as an opportunity to re-evaluate its own approach to creating safe and supportive school environments.

To help guide the discussion, this report by the Office of the Comptroller Scott M. Stringer presents a review of current data related to school safety in New York City, and from that data draws a series of holistic recommendations on how to make City schools healthier and more secure.[i] It is based on the premise that “school safety,” as a goal, extends beyond protecting children from external threats, and must include universal school-based mental health services, anti-bullying programs, and school disciplinary systems that students and teachers alike perceive as fair, not only in the rules they establish, but also in how equitably those rules are applied to different students and situations.

Unfortunately, progress in improving the climate of New York City schools has been uneven. When surveyed, students disclose the fact that bullying remains common in schools, and has climbed in recent years. Additionally, despite the significant long-term impacts on students’ academic outcomes, suspensions, issuing summonses, and even arrests continue to be used frequently in schools. These punishments continue to fall disproportionately on students of color. At the same time, while some schools are adopting less punitive, more restorative approaches to conflict resolution and behavioral challenges, without a system-wide, strategic implementation plan to support student mental health in schools and professional development of all school staff in trauma-informed crisis prevention and de-escalation, many schools are poorly equipped to significantly improve school climate.

Research indicates that arrest or court involvement involving students doubles the likelihood that a student will not complete high school. Similarly, suspension from school increases the likelihood that a student will drop out by more than 12 percent. The higher risk of drop out due to arrests and suspensions translates to significant costs, including lost tax revenues and additional social spending to taxpayers. And yet, despite recent improvements, such extreme responses are still common for students in New York City.

Specific findings of this report include:

- In the 2017 student survey, 82 percent of students in grades 6-12 said that their peers harass, bully, or intimidate others in school, compared with 65 percent of students in 2012.

- In 2017, over 17 percent of students in grades 6-12, disagreed or strongly disagreed that they felt safe in hallways, bathrooms, locker rooms, or the cafeteria of the school. Likewise, 23 percent of students in the same age groups disagreed or strongly disagreed that they felt safe in the vicinity of the school.

- In 2017, 17 percent of students surveyed feel that there is no adult in the school in whom they can confide.

- Despite supporting policies to reduce suspensions, the most recent data shows that suspensions increased in City schools by more than 20 percent in the first half of the 2017-18 school year compared with the same time period the year before. Black students are suspended at more than three times the rate of white students.

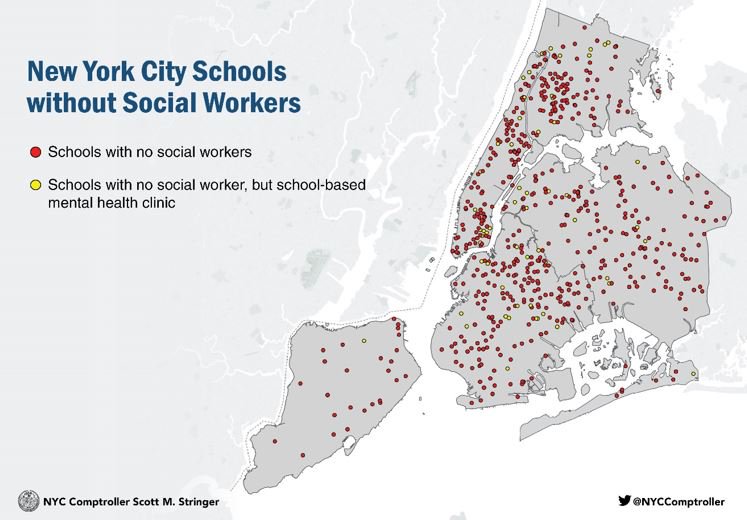

- Of the 612 schools reporting the most violent incidents in the 2016-17 school year, 218 (36 percent) have no full-time social worker on staff. Of those that do have a social worker on staff, caseloads average over 700 students — well above the minimum recommended level of one social worker for every 250 general education students.

- School Safety Agents and NYPD officers issued over 2,000 arrests or summonses in schools in the 2016-17 school year for charges including marijuana possession and disorderly conduct. In newly released data on law enforcement activity in the City’s schools, during the first quarter of 2018, there were 606 summonses and arrests, down from 689 in the same time period in 2017.

- In the 2016-17 school year, students were handcuffed in over 1,800 incidents, including children as young as five years old. More than 90 percent of students handcuffed were Black or Latinx. Similarly, 90 percent of all arrests or summonses involved Black or Latinx students.[ii]

These trends underscore the urgency to apply new strategies to the long-running challenge of system-wide school safety and discipline reform. Without investments in school-based mental health, fostering student social and emotional growth, and clear accountability measures for school climate improvement, too many students will be left to feel that schools are not doing enough to keep them safe and to provide the healthy environment necessary for building strong communities and advancing academic progress.

To address these issues, the Comptroller’s Office recommends that the City and the Department of Education:

Expand small social emotional learning advisories in all schools. Students who have a trusted group of peers and at least one adult to confide in have greater academic outcomes as well as more positive social attitudes and behaviors. Offering a daily or weekly advisory period within the school-day schedule, complete with a structured curriculum and teachers who are supported in implementing it, provides a framework to support and encourage students as they navigate social challenges. Many smaller schools already offer an advisory program and understand the benefits of a small group dynamic. To scale the advisory program to all schools, the DOE should begin by surveying schools to learn how many offer an advisory program within the school day. Additionally, the DOE should mandate that all middle and high schools have advisories in place and ensure schools have access to adequate curriculum supports and professional development.

Expand the Ranks of Social Workers and Guidance Counselors in Our Schools. In most cases, in-school behavior incidents are best dealt with by professionals who are trained in the appropriate responses to emotional or behavioral crises. Yet many schools do not have even a single social worker on staff to respond to school incidents in a trauma-informed way. The City should invest in social workers, ensure they have dedicated time and space in schools to work with students, and ensure school management has the capacity to help them succeed.

Add More Clarity to the Role of School Safety Agents. School Safety Agents (SSAs) are well-equipped to protect students from threats that may exist outside a school building, and to maintain secure school buildings and property. However, their training cannot prepare them – and they should not be expected – to police student behavior or manage mental health crises. In some cases, school administrations rely on Safety Agents or NYPD officers to respond to in-school incidents. In other cases, SSAs may interact with students in a way that is at cross purposes to a school culture based on trust and mutual respect. When Safety Agents interactions with students hinder a supportive school climate, other efforts to build trust within a school are minimized. This misalignment of resources has high economic costs to the City, as well as long-term social costs for children who end up diverted into the criminal justice system as a result of policing in schools. The City should update the Memorandum of Understanding that governs DOE’s relationship with NYPD to clearly outline the appropriate SSA interventions for specific student misconduct scenarios.

Fund a Comprehensive Mental Health Support Continuum. Nationwide, approximately two-thirds of youth with a mental health disorder go untreated. In New York City, with the launch of the ThriveNYC mental health initiative, more supports have become available in schools. However, to address mental health challenges for students – especially in schools with the highest incidents of suspensions and arrests – more targeted interventions and direct services for students are needed. The City should fund a continuum of mental health supports for the highest-need schools including hospital-based mental health partnerships, mobile response teams, and school-based mental health care.

Establish and Oversee System-Wide Trauma-Informed Schools. Students impacted by trauma are present in every school in the City, particularly when that trauma is linked to the chronic stresses of poverty. Because trauma can severely disrupt a student’s academic potential, schools need to support educators in taking a trauma-informed approach to students, through recognizing the signs in children and understanding how to positively respond to their academic and social-emotional behaviors. Classroom discipline that is trauma-informed is consistent, non-violent, and respectful. The Positive Learning Collaborative, an innovative pilot launched in 20 New York City Schools in partnership with the United Federation of Teachers, provides in-depth training to teachers in therapeutic crisis intervention, and supports school-wide bullying prevention and gender-inclusive schools. The City should create a system-wide trauma-informed approach at all City schools.

Expand Baseline Funding for Restorative Practices. Restorative practices, an alternative to exclusionary discipline, emphasize empathy, personal responsibility, and restoring community in the conflict resolution process. Examples from around the nation show that the approach has been highly effective in improving school climate and reducing suspensions. But transitioning to restorative practices requires investment in school-based consulting on implementation and capacity-building, and centralized program supports and evaluation. The City should adopt and sustain funding for restorative justice initiatives for a minimum three-year implementation period, and expand the initiative’s reach to more schools.

School climate is a bedrock education issue. Without cultivating safe and supportive schools for students and teachers alike, other initiatives aimed at improving academic outcomes will not be maximized.

Introduction: Safe and Supportive Environments Are Foundation of Success

In the wake of recent school shootings, school safety has become a high priority issue in school districts across the nation. And while these incidents are incredibly concerning, the reality is that most school violence originates from episodes of harassment or bullying between students, rather than external threats. According to results from the 2015 Centers for Disease Control (CDC) National Youth Risk Behaviors Survey, nationwide, 20 percent of high school students reported having been bullied on school property and 7.8 percent of high school students reported having been in a physical fight on school property within the last school year. Additionally, 5.6 percent of U.S. high school students reported not attending one or more school days in the previous year due to safety concerns, either at school or on their way to school.[iii]

In addition to the obvious immediate threat to students’ physical safety, exposure to in-school violence, including bullying, can also have long-term negative health impacts, for both students who are bullied and those who engage in bullying. Recognizing the serious public health risks resulting from in-school violence, including alcohol and drug use, depression, anxiety, and suicide, the CDC issued guidance on school violence prevention tactics.[iv] Fundamental to school-based youth violence prevention is a positive school climate.

In fact, a healthy school climate goes beyond violence prevention and is understood to be a key strategy in student academic success. A growing body of research indicates that, in addition to violence prevention, positive school climate is a strong indicator of academic achievement, healthy development of students, and teacher retention.[v] A healthy school climate is the foundation for an academically rich school that helps to build student success, and is a crucial aspect in supporting all children, especially those who face additional barriers to academic achievement.[vi] As outlined by the National School Climate Center, school climate can be measured by factors that impact social, academic and physical experience of people in the school. Every successful school is unique in its own way, but all involve several key components: engaged students, teachers and school staff; a safe and respectful school environment, both physically and online; and supportive and fair discipline protocols that are transparent to students, teachers, and families.[vii]

That said, New York City faces sizable challenges when it comes to serving its 1.1 million students. Over half of all children in New York City live at or close to the poverty threshold.[viii] Poverty burdens families with an array of needs that may inhibit students’ academic progress: housing instability, lack of health or mental health care, hunger, or exposure to violence are common examples of barriers that students face each day. Poverty, and the adverse circumstances associated with it, is strongly associated with trauma and chronic stress in children.[ix]

Experts believe that childhood trauma is more common than many realize – affecting as many as half to two-thirds of all students – typically because it can be difficult to detect in children.[x] And yet trauma can have a devastating impact on academic achievement of students. Trauma negatively impacts children’s ability to function in school, reducing capacity for memory or concentration and can also lead to misbehavior or difficulty forming healthy relationships with peers or teachers. In school settings where school discipline policies do not consider the added risks to trauma-impacted children, overly punitive or “zero-tolerance” practices that provide little opportunity for behavior reform may actually exacerbate the effects of trauma.

Additionally, many students enter school with mental health disorders or learning disabilities that require individualized planning and support. Nationally, one out of seven children aged two to eight years have a diagnosed mental, behavioral, or developmental disorder[xi], and one out of five children under 18 have a learning disability.[xii] In New York City, 19 percent of children have a disability that requires additional services.

School Climate in NYC Today

The best place to start in evaluating school climate is by looking at student perceptions of their own safety, and whether they believe people in their schools treat each other fairly and with respect. Of course, no school is immune to student bullying, in-school fights, or other disruptive behaviors. However, a closer review of City data on bullying, safety, harassment, and student surveys provides some insight into students’ daily experiences and shows the areas where the City must improve.

Bullying persists in NYC schools

Bullying is an insidious practice that often thrives in out-of-sight spaces where adults may not be alert to the interpersonal conflicts between students. Despite numerous laws and regulations at the federal, state, and local levels to curb bullying and harassment in schools, these behaviors persist.

In New York, the State’s Dignity for All Students Act (DASA) is the legal framework for both raising awareness of and demanding a more proactive response to episodes of harassment and bullying in schools. The law, passed in 2010, requires that schools name an administrative coordinator who is trained to mitigate and address incidents of bullying or harassment, provide information and resources to students and families about DASA, and report on any material incidents of harassment, bullying or discrimination. The incident reporting must include details about the nature of the harassment when possible, as is described in more detail below.[xiii] In 2013 DASA was amended to include cyberbullying.

New York City implements DASA requirements largely through provisions outlined in Chancellor’s Regulation A-832, which predates the State law. Notably, Chancellor’s Regulation A-832 requires that incidents of harassment or discrimination be officially reported through the DOE’s database tracking system within 24 hours and promptly investigated. It further requires all school staff members to receive training on how to increase awareness and identify harassment, bullying, and discrimination, and learn ways to respond to incidents. Finally, the regulation requires that each school designate a “Respect for All” liaison who will receive training and serve as a point of contact for reporting incidents of bullying and discrimination.[xiv]

Unfortunately, according to numerous accounts from schools and advocates, the Respect for All/DASA coordinator is not consistently implemented in all schools and many students were unable to identify their school’s DASA coordinator when surveyed.[xv] Schools do not receive funding to support the coordinator position, and trainings may consist of instructions conveyed in an email newsletter or optional webinar. This is a far cry from the intention of the law, which was supposed to equip schools with the tools they need to promote safe and supportive environments and to protect students from harassment and discrimination.

As a result of inconsistent and inadequate training, many DASA/RFA coordinators are unprepared to properly investigate and report complaints of bullying and harassment. This likely contributes to underreporting of bullying incidents. In the 2016-17 school year, the most recent full year for which data is available, across 1,585 public schools that reported, there were only 3,660 total incidents of reported bullying or harassment. In 42 percent of schools, there were no incidents reported, and in 96 percent of schools, ten or fewer incidents were reported for the entire school year.[xvi] A similar analysis by the New York State Attorney General’s office in 2016 found that 70 percent of New York City schools reported zero incidents of bullying or harassment and 98 percent reported fewer than ten incidents in the school year.[xvii]

In January 2018, City Council enacted Local Law 51, requiring bi-annual public reporting of data on student bullying, harassment or discrimination, which is tracked in compliance with Chancellor’s Regulation A-832. The first Local Law 51 report, which includes data for the fall 2017 semester (July 1 through December 31) indicates that incidents of bullying may be on the rise with over 4,128 complaints in that time period. The data in this report is unaudited and subject to change as complaints are investigated.

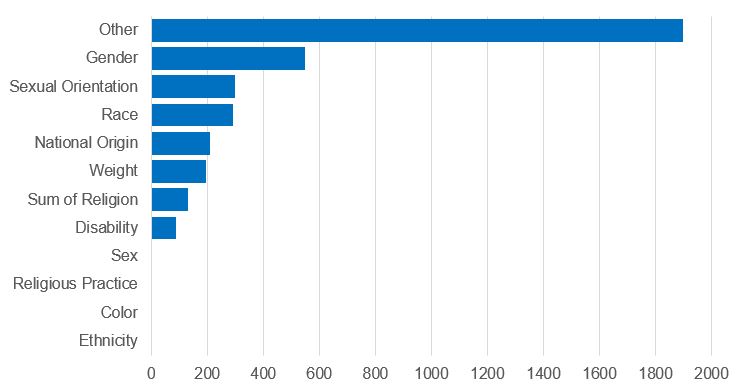

In addition to underreporting, schools provide very few details on the nature of incidents, contrary to the original intent of DASA. School personnel are instructed to classify the nature of the reported incident according to certain categories. Incidents are grouped by what provoked the harassment, whether race, ethnicity, cultural heritage, religion, disability, gender, sex, sexual orientation, or weight. Bias-related incidents are expected to be reported in the category that best captures the offense.[xviii] As seen in Figure 1, however, the vast majority of reported incidents are classified as “other,” possibly signifying a lack of adequate training about the reporting process and the relevance of documenting the types of problems most common in particular school communities.

Figure 1: 2016-17 Nature of Harassment Incidents

Source: NYSED, 2016-17 DASA reports (excludes cyberbullying incidents)

The weakness of the DASA data — which critically relies on adults to report incidents in their own schools — is further underscored by the picture that emerges when students are asked whether bullying is a problem in their schools. Every year, the DOE surveys students in grades 6-12 on a broad range of topics, from how engaged or stimulated they feel in the classroom, to whether students respect one another or bully each other often. In 2017, there was an 82 percent student response rate, similar to student response rates over the past decade.[xix]

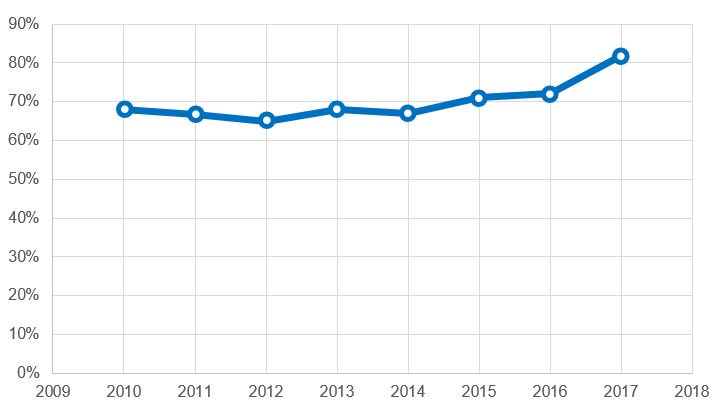

What the survey responses reveal is that bullying is consistently a common experience among students. In 2017, 82 percent of students reported that students harassed, bullied, or intimidated others in school, up from 65 percent of students in 2012 (figure 2). While this question related to bullying has been asked on the student survey for the past eight years, there was a slight change in wording in response options to the question in 2017. Previously, students were asked to respond to whether students harass, bully or intimidate other students none, some, most, or all of the time. In 2017, the response options were none of the time, rarely, some of the time, or most of the time. The graph below represents responses other than ‘none’ from students to the question “At this school students harass, bully or intimidate other students” for the past eight years.

Figure 2: Student Bully Others in School*

Source: NYCDOE Student Survey, public schools only; Excludes transfer high schools, D75 and YABCs

In some schools, the percent of students who report that bullying is common far exceeds this citywide average. Indeed, in 162 schools, more than 60 percent of students surveyed reported that students bully others some or most of the time.

Not surprisingly, at these schools more students also report feeling unsafe in unsupervised areas of the school or outside the school building. In these 162 schools, 30 percent of high school students and 27 percent of middle school students reported not feeling safe in hallways and bathrooms at their school. This compares to about 17 percent of students across all schools who feel unsafe in bathrooms or hallways.

Tracking In-School Incidents

Federal education law requires states to identify schools that are “persistently dangerous” each year. Since 2004, New York State Education Department (SED) has accomplished this by collecting reports of incidents in schools, classifying each as violent or non-violent, weighting certain violent incidents, and designating persistently dangerous schools according to a School Violence Index, a ratio of violent incidents to school enrollment. Schools with a high ratio of violent incidents for two years in a row are designated persistently dangerous, and students enrolled in those schools are given the option to transfer to another school. Additionally, persistently dangerous schools are required to develop and submit to state officials a plan to reduce violence.[xx]

In compliance with the State’s reporting requirements, New York City schools submit Violent and Disruptive Incident Reporting (VADIR) data. This data provides another measurement of school safety in City schools today.

There are some large caveats in the use of VADIR data in measuring school safety. First, in 2016, in response to years of complaints from educators and advocates about VADIR data and reporting, NYSED approved changes to the categories of incidents with an eye to improving the accuracy of the reports.[xxi] Many critics of the old reporting system noted the inconsistency of how schools understood the 20 different categories of incidents – classifications such as “reckless endangerment,” for example, could be interpreted differently by different schools and may have exaggerated the danger of some schools. Others noted that the School Violence Index often disadvantages smaller schools. Under the recent changes to VADIR reporting, which went into effect in the 2017-18 school year, categories of incidents have been clarified and reduced to nine. Data using the updated guidance on VADIR reporting is not yet available.

Secondly, the City has also been found to under-report incidents through VADIR. A 2015 audit by the New York State Comptroller found that the New York City Department of Education failed to report hundreds of incidents to the State Education Department, resulting in skewed school violence ratings. The audit reviewed incident reporting in 10 schools, including both the reports filed with the DOE within 24 hours of an incident occurring, and the VADIR data submitted to the State Education Department. [xxii] Auditors found more than 400 incidents that were never reported to state officials.

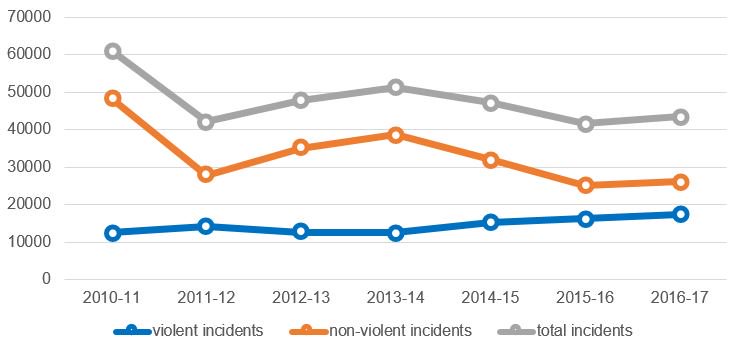

Despite the legitimate concerns with VADIR data, a review of reported incidents over the past seven years highlights some trends worth noting. Between 2010 and 2016, there was an overall decrease in total incidents, with 43,427 public school incidents reported in the 2016-17 school year, down from 61,013 in 2010-11.

Incidents reported through 2016-17, under the previous VADIR guidance, were categorized as either violent or non-violent. Incidents classified as non-violent declined by 46 percent, from 48,406 in 2010-11 to 26,132 in 2016-17. That said, incidents classified as violent actually rose 37 percent during this period from 12,607 in 2010-11 to 17,295 in 2016-17 (see figure 3).

Figure 3: 7-year Incident Trend, Violent vs. Non-violent

Source: NYSED, VADIR reports, includes NYC public schools only

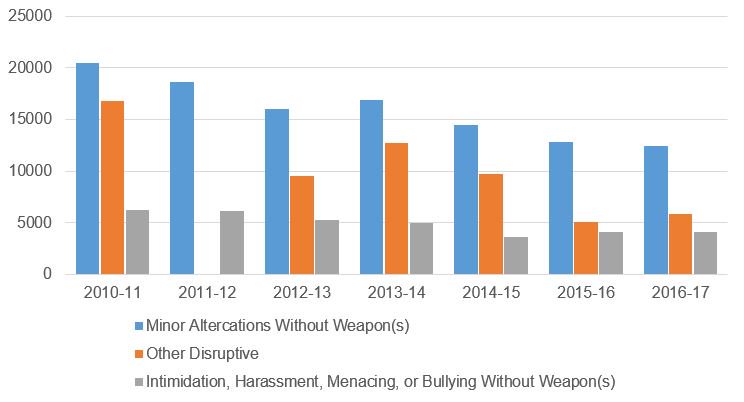

The vast majority of incidents reported in schools are classified as non-violent in VADIR reports. Of the 43,427 total reported incidents in 2016-17, 26,132 (60 percent) were classified as non-violent. Non-violent incidents include minor altercations or disruptive incidents that do not include a weapon, intimidation and harassment, and drug possession, incidents for which response from law enforcement is unnecessary and inappropriate. Over the past seven years, the most commonly reported incident type has consistently been minor altercations without a weapon, with trends declining since 2010-11 when there were 20,433 such incidents, compared with 12,441 in the 2016-17 school year, a 39% change (see Figure 4 below). The next most commonly reported non-violent incident is the ambiguously named classification “other disruptive,” which has also seen an overall decline over the past seven years. (In 2011-12, this incident type was not among the most reported incidents.) Incidents classified as “intimidation, harassment, menacing or bullying” have been the third most commonly reported incident classified as non-violent across New York City public schools since 2010-11.

Figure 4: Most Commonly Reported Non-Violent Incidents

Source: NYSED, VADIR reports, public schools only

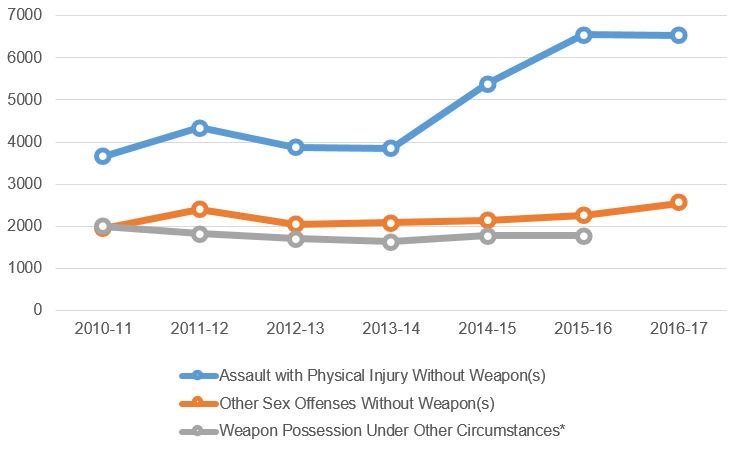

While incidents categorized as ‘violent’ are less common in schools, it is concerning that there has been an increase over the past eight years. As seen in Figure 5, assault has consistently been the leading violent incident reported, and significantly increased since 2010. Assault resulting in a physical injury (not including a weapon) increased by 79 percent, from 3,655 reported incidents in 2010-11 to 6,526 in 2016-17. It is important to note that, while incidents may be categorized as ‘assault’ in schools, this categorization may reflect both serious, violent behavior and much less harmful episodes. For example, a write-up involving a student shoving another student may be categorized as an assault.

Under the prior VADIR reporting requirements, the most commonly reported incidents classified as violent, included:

- Assault with physical injury without a weapon

- Other sex offenses without a weapon

- Weapon possession (through screening or under other circumstances)

Going forward, under the updated reporting requirements to the State Education Department (SED), categories have been simplified and will no longer include certain categories such as ‘reckless endangerment’ or ‘criminal mischief’.

Figure 5: Three Most Commonly Reported Violent Incidents*

Source: NYSED, VADIR reports, NYC public schools only

*Weapon Possession was not a top reported violent incident in 2016-17.

Same Schools Show Chronic Problems

While some interpersonal conflict among students is typical and far from surprising in most schools, it is clear that a handful of schools show chronic deficiencies in preventing, de-escalating, and appropriately responding to behavior-related conflicts and violent incidents. Many of these same schools have the highest suspension rates, high rates of chronic absence, and most have very poor ratings from student surveys on indicators that contribute to school climate.

DOE administration has indicated that Borough Field Support Centers work in conjunction with district superintendents to monitor incident reports and school survey data to identify schools in need of support.[xxiii] And yet, notably, of 612 schools reporting the most violent incidents in the 2016-17 school year, 218 (36 percent) have no full-time social worker on staff.[xxiv] Of those that do have a social worker on staff, caseloads average over 700 students, well above the minimum recommended level of one social worker for every 250 general education students.[xxv]

Student Survey Data

As previously noted around the issue of bullying, student opinions about safety in their schools often document a different reality than what administrators might choose to project. Ask any student whether they feel safe or respected, or if they feel they have an adult to confide in at school, and a picture emerges of how a school prioritizes a supportive and inclusive community.

In fact, since 2007 these questions and many more are asked of all New York City students in grades 6-12 each year in the annual student survey. The student survey, which is anonymous, gathers information about students’ experiences on a range of issues, from how engaged or stimulated they feel in the classroom, to whether students respect one another. In 2017, there was an 82 percent student response rate, similar to student response rates over the past decade.[xxvi]

In fact, many public school students in New York City report feeling isolated and unsafe in unsupervised parts of schools or in the neighborhoods surrounding schools. These metrics also are connected to chronic absenteeism, which has a direct impact on student achievement. For this reason, many believe that survey results should be used as a leading indicator for school and district leaders when deciding how to direct resources to improve school climate.[xxvii]

Trends

Using a consistent sample of eight years of survey results that span two separate mayoral administrations, trends reveal that very little has changed in students’ perceptions of school climate. This analysis is based on a review of survey responses to seven questions asked over the past eight years. Four questions have been asked consistently in the last eight years. Three additional questions, while not included in the student survey each year, have appeared on the survey a number of times throughout both the Bloomberg and de Blasio administrations.

The questions related to school climate that have been included on the student survey each year are:

- Most students at this school treat each other with respect. (Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree)

- I feel safe outside around this school. (Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree)

- I feel safe in the hallways, bathrooms, locker rooms, and cafeteria of this school. (Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree)

- At this school students harass, bully or intimidate other students. (None of the time, Rarely, Some of the Time, Most of the Time)

Given the individualized experience of students in schools across the City serving a variety of age categories, it would be inappropriate to draw conclusions about citywide progress based solely on responses. However, some patterns provide a basis for further inquiry.

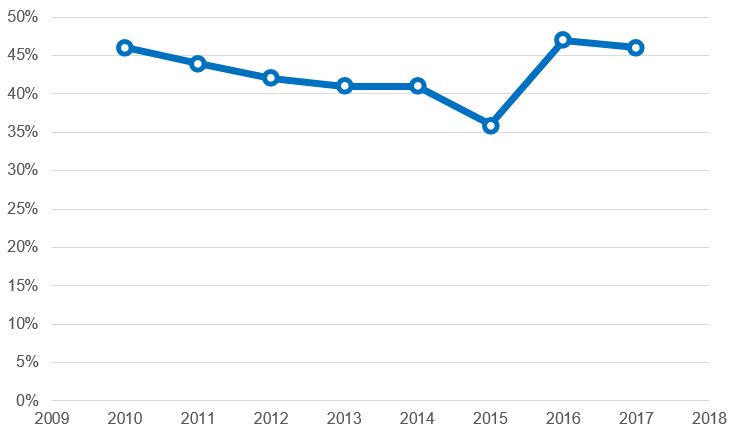

Respect

Specifically, about 46 percent of students stated that they disagreed or strongly disagreed that students in their school treat one another with respect. While there had been a decline in the number of students who disagreed with the statement, it has again risen to the same level as in 2010 (figure 6).

Figure 6: Most students treat each other with respect

Disagree/Strongly Disagree

Source: NYCDOE Student Survey, public schools only, excludes transfer high schools, D75 and YABCs

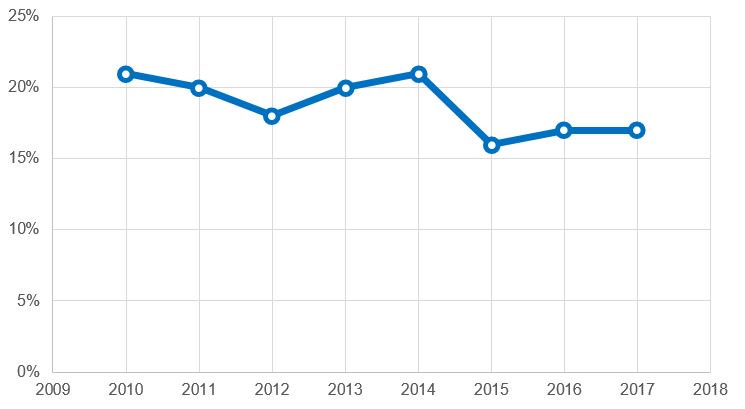

Feel Safe in Schools

Overall, students’ sense of their own safety has improved slightly in the past several years. Specifically, in 2017, 17 percent of all 6-12 grade students citywide, disagreed or strongly disagreed that they felt safe in hallways, bathrooms, locker rooms, or the cafeteria of the school, down from 21 percent in 2010 (figure 7).

While important to note the improvement in students’ sense of safety in schools, it cannot be overlooked that 63,000 New York City middle and high school students (17 percent) do not feel safe in unsupervised areas of school. This alone should be a catalyst for deeper analysis of the factors that contribute to student safety at the individual school level.

Figure 7: I feel safe in the hallways, bathrooms, locker rooms, and cafeteria of this school

Disagree/Strongly Disagree

Source: NYCDOE Student Survey, public schools only, excludes transfer high schools, D75 and YABCs

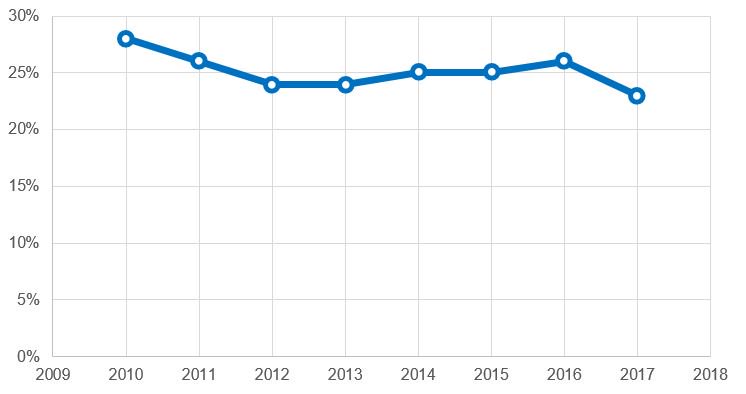

Feel Safe Outside Schools

Similarly, in 2017, 23 percent of 6-12 grade students disagreed or strongly disagreed that they feel safe outside around the school, compared with 28 percent in 2010 (figure 8).

Figure 8: I feel safe outside around this school

Disagree/Strongly Disagree

Source: NYCDOE Student Survey, public schools only, excludes transfer high schools, D75 and YABCs

School Discipline

Two questions related to school discipline have not been asked in the student survey each year, making it impossible to track the change in students’ responses to those questions over time. However, the questions provide a point-in-time sense of how students believe school discipline issues are handled and are instructive as they show a lack of change between years.

When asked if discipline is applied fairly in schools, about 30 percent of students in grades 6-12 disagree or strongly disagree, consistent between 2010 and 2017. Likewise, in 2010, 22 percent of students disagreed or strongly disagreed that School Safety Agents promote a safe and respectful environment in school. In 2017, 20 percent did as well.

A third question, which has only been included on the survey since 2013, asks students whether there is at least one adult in the school in whom they can confide. Over the past five years, on average 17 percent of students disagreed.

School climate, absenteeism, and academic performance

Unsurprisingly, student survey responses to questions about school climate show a close connection to higher rates of chronic absence, defined as missing 10 percent or more of school days each year. In schools with high rates of chronic absence, student responses to survey questions reveal that more students feel unsafe, disrespected, isolated, bullied or harassed.

The contrast is particularly striking compared with schools with low rates of chronic absence. At 93 schools with chronic absenteeism rates over 50 percent in 2016-17:

- 51 percent of student survey respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that students in their school treat each other with respect, compared with 30 percent in schools that had chronic absence rates below 10 percent, and

- 20 percent of students disagreed or strongly disagreed that they felt safe in hallways, bathrooms, locker rooms, or the cafeteria, compared with 10 percent of students in schools with chronic absenteeism rates under 10 percent.

These patterns are particularly evident in certain districts. For example, District 8 in the Bronx has a chronic absenteeism rate of 45 percent. In schools across District 8, 56 percent of students disagree or strongly disagree that students treat each other with respect, 53 percent say that students bully other in school “some or most of the time,” and 36 percent disagree or strongly disagree that discipline is applied fairly in school. Such negative school experiences work against school and district efforts to improve attendance.

Chronic absenteeism is a leading indicator of lower academic performance and an important red flag for students who develop disciplinary issues.[xxviii] Research focused on the Baltimore City Public School district found that chronic absence is actually the strongest predictor of high school drop-out rates.[xxix] Furthermore, observations based on analysis of the school climate survey mirror academic research from other urban school districts that found students who report negative ratings for school climate are more likely to attend schools with high rates of chronic absenteeism, and that schools with the poorest ratings in school climate also had significantly higher rates of chronic absence.[xxx]

It is important to emphasize that, in general, these citywide numbers mask trends in individual schools where school climate and student safety have improved or worsened substantially. But the larger consideration is that students’ perception matters – and should be considered a meaningful indicator of risk or achievement for principals and district superintendents.

City’s Discipline Protocol Needs Repair

Encouraging a school environment where students feel safe and episodes of harassment are minimal requires a strong mental health and social-emotional support system, balanced with school discipline policies that are fair for all students. Instead, for decades New York City has built and maintained a disciplinary structure that is erratic in implementation and disproportionate in the impacts it leaves on students. In addition, positive supports like social workers and mental health interventions are not available for all schools in the system. As documented below, there are enormous hidden costs to the current discipline protocols in place in many schools, including use of suspensions and interventions by the NYPD.

Suspensions

Exclusionary discipline practices, like suspensions, remain common in many schools despite recent efforts by the de Blasio Administration and the Department of Education to reduce suspension rates. High suspension rates in schools often signal that learning environments are not structured to maximize student academic success. Indeed, research has shown that individual school policies and attitudes toward discipline are the primary contributor to high suspension rates, rather than student behavior.[xxxi] Essentially, when school administrators apply best practices in inclusive schools and classrooms, teachers and staff have the resources they need to de-escalate behaviors before suspensions are necessary. Furthermore, research indicates that alternatives to suspension and exclusionary discipline methods have the highest impact on both decreasing involvement in the juvenile justice system and improving graduation rates.[xxxii]

The City has repeatedly cited reduction in suspension rates in schools as evidence of progress in improving school climate. However, the most recent data released from July-December 2017 documents a 21 percent increase in suspensions compared with the same time period from the previous year.[xxxiii] This is a dramatic uptick after several years of declining suspensions. In the 2016-17 school year, the most recent school year for which there is a full year of data available, there were 46,571 removals or suspensions across all districts, a 6 percent decrease over the previous year in which there were 49,590 removals or suspensions.

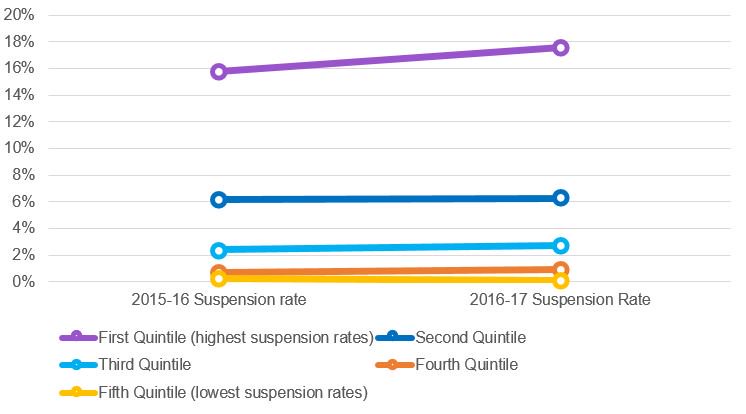

Despite the downward trend in suspensions in previous years, a closer look reveals that much of the progress in reducing suspensions has been driven by schools that already had few suspensions. In fact, schools that have the highest rate of suspensions actually saw an increase in the 2016-17 school year. Figure 9 below represents data for 1,618 schools that had suspension and enrollment data for school years 2015-2016 and 2016-2017. Among these, schools with the lowest suspension rates saw no significant change. At the same time, in the 324 schools in the quintile with the highest suspension rates, average suspension rates increased 2 percent from 16 percent in 2015-16 to 18 percent in 2016-17.

Figure 9: Average Suspension Rates by Quintiles

Year-Over-Year Comparison

Source: NYC DOE Suspension Reports 2015-16 and 2016-17, pursuant to LL 93

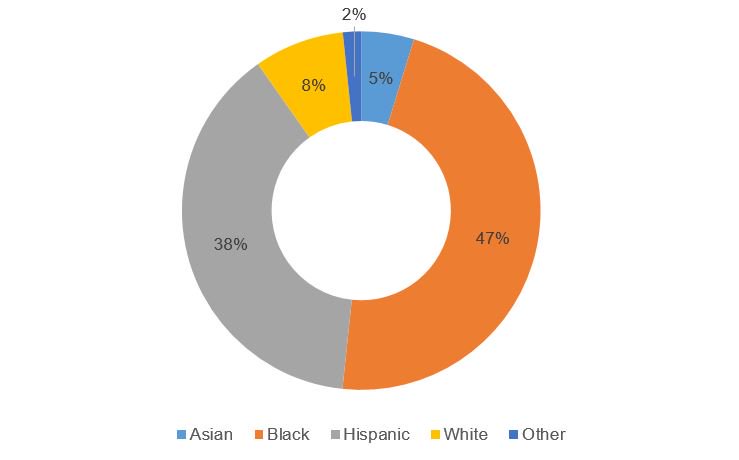

In New York City as elsewhere, suspensions have a disproportionate impact on Black and Hispanic students. Black students are suspended at more than three times the rate of white students. In the 2016-17 school year, Black students comprised about 26 percent of the student body but received 47 percent of all suspensions (figure 10), and 52 percent of all suspensions longer than five days. Together, Black and Hispanic students represent 67 percent of all enrolled students, but 88 percent of all students with multiple suspensions in the school year. This is consistent with previous years.

Figure 10: Total Suspensions* by Race

*Includes both principal and superintendent suspensions

Source: NYC DOE, 2016-17 Suspension reports, pursuant to Local Law 93

Given the prevalence among New York City students of trauma-related conditions, mental health disorders or a disability, the Department of Education’s continued use of harsh disciplinary responses in schools is deeply concerning. Although Mayor de Blasio and DOE’s leadership have signaled interest in improving school climate and reforming discipline policies in schools, changes have been limited to a handful of schools. Moreover, spending on law enforcement in schools, who may be involved in school discipline, reveals that the stated commitment to discipline reform has not been supported with direct funding, guidance or training for alternative approaches.

Of course, New York City is not alone as a large, urban district working to reform its practices of exclusionary discipline. Los Angeles School District has also prioritized reduction of suspensions, particularly for “willful, defiant” behavior.[xxxiv] While suspensions have decreased in Los Angeles, overall suspensions continue to disproportionately affect Black and Latinx students.[xxxv] Likewise, Chicago has also begun to adopt alternative practices to “zero-tolerance” discipline, yet in schools that predominantly serve low-income Black and Latinx students, suspension rates remain high.[xxxvi]

Unfortunately, simply adopting policies to make it more difficult to suspend students does not equip school leaders or teachers with the resources they need to offer alternatives to suspensions.

Costs of Suspensions

Suspensions have negative consequences for students even after graduating high school. In New York City, suspensions may be indicated on a student’s permanent academic record, and may be negatively used against that student when applying to college or other post-secondary opportunities. Nationwide, suspension is a strong predictor of whether a high schooler will drop out. A 2016 study from The Center for Civil Rights Remedies at UCLA sought to determine both the impact of suspensions on high school graduations as well as the fiscal impact of suspensions. The study found in many cases students who are suspended from school have additional challenging circumstances, including a history of poor academic performance and relatively low family income. Even when controlling for these other factors, however, researchers found that suspension from school increases the likelihood that a student will drop out by more than 12 percent.[xxxvii] As a result, the research concluded that nationwide, suspensions translate to at least $11 billion in lost tax revenues and $35 billion in social costs, clearly a significant cost burden to taxpayers.[xxxviii]

Suspensions also have a real economic cost on New York City. According to an analysis by the Center for Popular Democracy, each year the City spends approximately $30 million to operate Suspension Hearing Offices and Alternative Learning / Suspension Centers where students go to serve a long-term suspension.[xxxix] By way of example, $30 million would be enough money to hire 350 social workers or guidance counselors, or build capacity to implement and expand restorative justice programs across schools citywide.

NYPD responses

In some cases, violations of school conduct that result in a student’s suspension may also trigger a second punishment from law enforcement, with potentially more severe outcomes. Through a Memorandum of Understanding established in 1998, the NYPD stations officers, known as School Safety Agents (SSAs), in every school in New York City. School Safety Agents are charged with securing school buildings from outside threats while also protecting students’ rights.

After the initial transfer of authority for school safety from educators to the NYPD, and in response to a rising number of arrests and concerns of over-policing students, in 2007 community advocates began to call for greater transparency of school safety issues. In 2011, Local Law 6, the Student Safety Act, was adopted, and required DOE and NYPD to submit annual data reports to the City Council on students who have been arrested or suspended, as well as information on incidents in schools, disaggregated by race, gender and disability status.[xl]

In 2015, Local Law 93 was adopted, expanding the scope of the Student Safety Act of 2011. Local Law 93 requires biannual reports to be submitted and made publicly available, and to include greater details on the number of NYPD violations issued in schools, whether restraints were used, and how many complaints were made against SSAs and other NYPD officers due to school-related incidents.

Through the public reporting pursuant to the Student Safety Act, the public has a better understanding of how the NYPD responds to student behavioral incidents in New York City public schools and which groups of children are most often impacted.

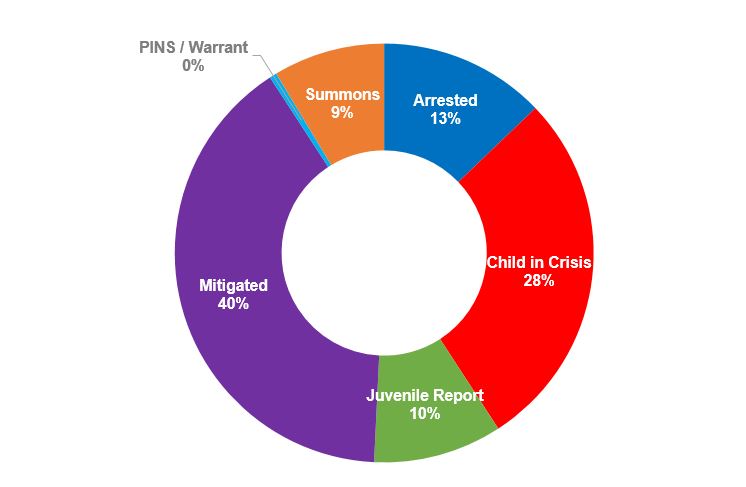

In the 2016-17 school year, School Safety Agents and NYPD officers intervened in behavioral incidents, on average, over 50 times a day, citywide. Reported data separates each intervention by six types: arrests, summonses, child in crisis events, juvenile reports, mitigated events, and PINS warrants (Figure 11).[xli] Each type of intervention has associated long-term social and economic costs, as is described below. Newly released data from the first quarter of 2018 shows decreases in all law enforcement interventions in schools, suggesting that recent investments in improving school climate may be having a positive impact.[xlii] Arrests were down by 20 percent compared with the first quarter of 2018. Use of restraints during police interactions with students also appears to be decreasing, with a 13 percent decline in the first quarter.

While these trends are encouraging, it is important to also emphasize the unintended consequences of having law enforcement present in schools. As officers of the NYPD, Safety Agents are authorized to use some police-style tactics in apprehending students suspected of an infraction, including the use of handcuffs.

In the 2016-17 school year, students were handcuffed in over 1,800 incidents, including children as young as five years old. More than 90 percent of students handcuffed were Black or Latinx.[xliii] Despite declining trends, there were still 499 incidents that involved restraining a student in the fourth quarter of 2017. Such an experience can have lasting negative impacts, especially for children suffering from other traumatic life experiences, such as those associated with poverty.[xliv]

Figure 11: School Safety Agent Interventions 2016-17

Source: NYC School Safety Data, Compiled reports from July 2016-June 2017

Arrests and Summonses

Arrests and summonses can be issued by a School Safety Agents or NYPD officer in schools. In the 2016-17 school year, there were 2,073 arrests or summonses conducted in schools, including 48 instances that involved children 12 or under. Arrests and issuing summonses account for 22 percent of all reported NYPD/School Safety Agent interactions with students. In the fourth quarter of 2017, there were 695 arrests or summonses, up from 627 during the same time period of 2016. The majority of arrests and summonses are issued by NYPD officers rather than SSAs. Summons violations are most commonly for possession of marijuana or fighting, while arrests involve more serious behavior – half of all student arrests in 2016-17 were on charges of assault or robbery.[xlv] In many cases, arrests of students may be carried out in schools for behavior that originated off-site. For example, a child or adolescent suspected of shoplifting in the neighborhood may be arrested while in school. Students may be handcuffed during an arrest or in any event for which a summons is issued. In the 2016-17 school year, metal restraints were used in 88 percent (1,093 times) of all arrests and 15 percent (125 times) of all summonses.

Social costs of arrests and summonses of students

Arrests and summonses have lasting long-term impacts on students and communities. Both result in student absence from school and lost instructional time. Furthermore, an arrest or summons can jeopardize a student’s – and his or her family’s – housing or immigration status. In NYCHA or DHS homeless shelters, for instance, housing may be revoked if there is evidence of criminal behavior.[xlvi] Employers also may have little tolerance for a students’ criminal record, even if an incident report was the result of a minor offense in school. Additionally, when a student is arrested or issued a summons for a violation, the school administration may also suspend a student for the same offense, resulting in a double punishment.

Moreover, student interactions with the criminal justice system increase the likelihood of a student dropping out of high school. In a longitudinal study assessing the effects of first time arrests or court involvement on students in a school setting, researchers found that arrests double the likelihood that a student will not complete high school, and court appearances quadruple that likelihood. For youths with no record of misbehavior in school, a court appearance is especially harmful.[xlvii]

The effectiveness of issuing summonses to students for minor incidents or misbehavior in schools has proven to be minimal. According to a John Jay College of Criminal Justice report on summonses, of all summonses issued to 16- and 17-year olds in 2015, over 40 percent were dismissed as legally insufficient. As pointed out in a 2007 report by the New York Civil Liberties Union, summonses written in school as a response to breaking a school rule are likely dismissed at a higher rate, since there is typically no crime involved.[xlviii]

Additionally, warrants are issued for the arrest of students who fail to appear for a scheduled court date, either because they are unfamiliar with the process, lost the summons slip, or are afraid to appear in court.[xlix] The entire process can cause students to miss multiple days of schools, may require that parents take time off work to accompany them in court, and can be sentenced to pay a $250 fine for a violation, a significant burden for many students and families.

Child in Crisis / EMS transfers

Child in crisis events are those in which a child or adolescent in emotional distress is removed from the school and transferred, typically by ambulance, to a hospital for psychological evaluation. These events are reported separately by the NYPD, FDNY, and the Department of Education, depending on which agency made the call for emergency transfer. EMS transfers are reported by the school, and Child in Crisis events are reported by the NYPD; however, there are clear overlaps in reporting these incidents.[l]

As with other disciplinary practices, the City and DOE have recently taken steps to curb the overuse of EMS transfers. A 2013 lawsuit filed in federal court alleged that school personnel were overly reliant on EMS transfers as a way of responding to childhood behavior issues because school staff, due to lack of training or resources, were unable to appropriately intervene and calm a child experiencing an emotional disturbance.[li] In 2014 the plaintiffs and Department of Education reached a settlement requiring new protocols be followed to avoid unnecessary EMS transfers for students having emotional or psychological crises. The settlement also expanded the number of staff trained in Therapeutic Crisis Intervention for Schools (TCIS) in schools with especially high rates of EMS transfers due to a child’s emotional condition.[lii] Chancellor’s Regulation A-411 outlines the protocols for crisis de-escalation training and support planning for all schools.[liii]

In the 2016-17 school year the NYPD reported 2,702 instances in which students were transferred to a hospital due to their emotional condition, or about 15 trips every school day, citywide. Children may be handcuffed or restrained during these events, and in the 2016-17 school year, restraints were used 12 percent of the time during Child in Crisis events, including for children as young as five years old. Nearly 90 percent of all Child in Crisis events involve Black or Hispanic children.

Pursuant to the reporting requirements outlined in the Student Safety Act, the Department of Education reports on its response to students’ medical and mental health emergencies, noted as EMS Transports. In some cases, these transports correspond to the NYPD’s Child in Crisis events. For the 2016-17 school year, DOE reported 7,850 student EMS transports, or about 43 times every school day, citywide.[liv] These transports represent all cases for which a student was taken to the hospital, including an injury due to a fall or other accident, medical condition other than injury, emotional condition of the child, and suicidal behavior/ideation. Of these, students with disabilities are transferred at more than twice the rate of general education students.[lv]

In this same time period, of these 7,850 transports, approximately 1,320 EMS transfers were the result of the emotional condition of the child, approximately 17 percent of the total EMS transports.[lvi] District 75, the City’s non-geographic school zone for special education students, had the highest rate of EMS Transfers: 287 times students were transferred by EMS to a hospital for psychiatric evaluation due to the emotional condition of the child, or 26 percent of all emergency transfers in the district.[lvii]

Needless to say, the effect of EMS transfers can be exceptionally traumatic for children, especially for students with disabilities. In schools and districts where EMS calls are made frequently, more intensive supervision and training is needed to ensure school staff are able to mitigate a behavioral episode or prevent it from further escalation. The goal must always be to support students so they can participate in classroom activities and avoid unnecessary trips to the emergency room. Such transfers are wasteful and needless disruptions from instructional time, and are also an inefficient use of emergency response resources. Additionally, restraining and transporting a student to an unfamiliar location can exacerbate problematic behavior or even lead to new disruptive behavior. Restraining children while in emotional distress can be especially damaging psychologically, resulting in a range of negative long-term impacts including Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.[lviii]

Juvenile Reports

Juvenile Reports are essentially official reports filed in lieu of an arrest or summons. These reports typically involve children under the age of 16 and are filed for behavior for which NYPD could arrest a student or issue a summons but choose to file a juvenile report instead.[lix] In the 2016-17 school year, School Safety Agents or NYPD officers issued 960 juvenile reports, and restraints were used about 16 percent of the time in these cases.

In some cases, school observers have found that juvenile reports are issued in circumstances in which a student also receives a suspension, effectively doubling the punishment for the same offense. This raises questions about whether, through these responses by the NYPD and School Safety Agents, the City is unnecessarily duplicating efforts in responding to student misbehavior.

Mitigated events

Mitigated events account for 40 percent of SSA interventions in schools in the 2016-17 school year. These are incidents that the NYPD considers a violation for which an arrest or a summons could be carried out but are appropriately referred to the school administration for discipline. Students may be handcuffed or restrained as a result of the intervention, but are not processed by the NYPD. Restraints were used in 76 mitigated events last year, or about 2 percent of the time.

The interventions outlined above represent the most extreme, yet still common, responses to student behavior by the NYPD and School Safety Agents. Such involvement with the police, can be devastating to children, especially when handcuffs or restraints are used and when a child has suffered prior traumatic experiences. As identified in a 2017 report by Advocates for Children, the disproportionate use of handcuffs or restraints on Black and Latinx children, as well as students with disabilities may be considered a violation of State law that prohibits use of physical restraints to discourage specific behaviors. Further, handcuffing students with disabilities during emotional or psychological distress may be a violation of their civil rights, protected under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).[lx]

Total Spending on NYPD in Schools

Over the past three years, the cost of staffing approximately 5,000 school safety agents in all schools has averaged about $378 million, with increases in the annual budget each year.[lxi] New York City far outspends other large school districts on safety agents and police enforcement in schools. Costs for school security in New York City – including staffing agents and maintaining screening equipment – is approximately $322 per student.

In the decades since the School Safety Agent position has been introduced into City schools, the latitude with which some school administrators have come to delegate basic monitoring of student behavior to safety agents has changed. While there are certainly valid reasons for staffing and monitoring entrances for building safety, it is clear that there can be unintended consequences when law enforcement is present in schools. Safe and supportive schools ensure that all adults in the building are positively contributing to a school environment that supports student success. This must include School Safety Agents and NYPD officers who at any time enter a school building.

At current staffing levels, there is about 1 safety agent per 228 students. This compares with a citywide average ratio of guidance counselors to students of 1:375, and social workers to students of 1:612, discussed in more detail below.

Other School-Based Responses: Social Workers, Mental Health, and Restorative Practices

Social Workers

For comparison, across over 1,600 schools, the City currently employs a combined total of 4,173 guidance counselors and social workers in schools. Over 65 percent of schools (1,375 schools) have at least one full time guidance counselor on staff and 90 percent have either a full time or part time guidance counselor on staff.

Citywide, the DOE claims an average student-counselor ratio of about 1:274 students, which represents a combined ratio of guidance counselors or social workers per student.[lxii] Guidance counselors have numerous duties within a school that go beyond supporting behavioral or mental health of students. Guidance counselors at the high school level may be required to assist with course scheduling, review student’s academic credit accumulation to keep students on track for graduation, or provide students support in applying to colleges, internships, or other post-secondary opportunities. Social workers, whose training and expertise equip them for supporting emotional or mental health of students and are more likely to have dedicated time to work with students one-on-one, are less common in schools than guidance counsellors. In the 2016-17 school year, 725 schools serving students across all grades – 45 percent of all schools– had no social worker. This includes 240 elementary schools, 194 high schools, and 159 middle schools:

Schools With No Assigned Social Worker 2016-17

| School Type | Number of Schools |

| Early Childhood | 12 |

| Elementary | 240 |

| High School | 194 |

| Middle School (6-8) | 159 |

| K-12 All Grades | 16 |

| K-8 | 57 |

| Secondary School (6-12) | 47 |

Many of the schools that lack a social worker also lack any mental health supports. While schools without social workers or mental health supports are located across the City, many are clustered in parts of the Bronx and the Lower East Side (see Map, below).

Mental Health

Despite near-universal agreement that mental health care in schools is vital for both the academic progress of students and efficient operation of classrooms, what is actually available in New York City public schools is a patchwork of services, with each school provided different resources to meet the needs of the school community. In some cases, resources are intended to support schools in high-poverty areas where needs may be greatest. And yet, in many other cases, high-need schools are left with minimal access to the behavioral and mental health supports they need.

Schools designated as Community Schools, which receive additional funding to partner with community-based organizations and mental health providers, conduct mental health assessments for students, and provide mental health services, including counseling, for enrolled students. In the 2016-17 school year 56 Community Schools operated school-based mental health clinics.[lxiii] Some schools that are not designated Community Schools may also have school-based mental health services. Approximately 200 public schools, including Community Schools, house a mental health clinic.

In addition to these school-based resources, the Thrive NYC mental health initiative makes 100 mental health consultants available to all schools in the city for mental health support. The program, which has an overall four-year budget of $850 million, provides various agencies with resources to incorporate mental health supports into their services, with a portion funneled into the DOE for mental health consultants to conduct assessments in schools and direct schools to outside providers. While ThriveNYC has successfully raised awareness of mental health needs in schools, the program does not yet target resources to schools with the highest mental health needs and consultants are not direct service providers working with students.[lxiv]

However, more is needed to provide targeted interventions for students with unmet mental health challenges or exposure to trauma. Despite the promise of the Thrive NYC initiative and the mental health supports in Community Schools, a significant number of schools with similar populations of students cannot adequately address unmet mental health needs through ThriveNYC’s interventions.

Restorative Practices

To reverse the trend of exclusionary and discriminatory discipline, there has been a nationwide movement, including in New York City, toward restorative practices as a framework for building community, and strengthening cultural awareness and inclusion. Restorative practices emphasize conflict resolution and focus on accountability within the entire community when behavior impacts individuals in a school. Within this framework, schools see positive results for improving school climate.[lxv]

With an emphasis on proactive engagement in the school community, schools that commit to restorative practices find that conflicts are deterred, and suspensions and recidivism drop significantly. Case studies from the U.S., Canada and England illustrate deep impacts that result when schools fully adopt restorative practices. For example, an urban high school in Philadelphia implemented restorative practices in 2008 and saw violent incidents drop by forty percent and suspensions decrease by half.[lxvi] An assistant principal in the school reflected on the transition to restorative practices and how it impacted student behavior: “What restorative practices does is change the emotional atmosphere of the school. You can stop guns, but you can’t stop them from bringing fists or a poor attitude. A metal detector won’t detect that.”[lxvii]

In New York City schools, these practices are beginning to take root. In 2016, in concert with the City Council, DOE has introduced a tiered Restorative Practices program in schools with high numbers of violent incidents. The program implements Restorative Practices in 25 schools through staff training and support through borough field offices. In addition, 14 other schools across 12 districts received a funding allocation to hire restorative justice coordinators for the past two years. In Spring 2016 DOE also implemented a pilot that introduced Restorative Practices to 35 schools in District 18.

Funding for these pilot initiatives so far has come directly from Council allocations including $1.7 million in the FY17 and an additional $1.5 million in FY18 for restorative justice programs.[lxviii] This includes training some school staff in participating middle and high schools and staffing a restorative justice coordinator to oversee implementation in 14 schools. Unfortunately, these initiatives have not yet been funded with the intent to significantly increase capacity or scale citywide. Furthermore, to date there has not been a full evaluation of these initiative’s impacts. While many have pointed to a drop in suspensions in the 2016-17 school year as a positive sign of large scale school climate improvement, the spike in suspensions in the first half of 2017-18 signals a need for greater coordination – including implementation oversight – of restorative practices in more schools. Additionally, because the above are all short-term pilot projects, many of the current restorative justice initiatives may be at risk after funding stops.

Other pilot initiatives

Additional initiatives are being piloted by the DOE to reduce bullying in schools.[lxix] In particular, an $8 million suite of initiatives aimed at curbing bullying in schools and supporting LGBT clubs in schools includes an online bullying complaint portal.[lxx] Also, the Single Shepherd pilot program increases guidance counselors and academic advisors in districts 7 and 23. Another pilot initiative is the Positive Learning Collaborative, a joint project between the United Federation of Teachers and the DOE, and currently in place across 20 schools. This initiative seeks to provide holistic and intensive training to all school staff to prevent crisis situations and deescalate conflicts when they arise. A component of evaluation has been built into the project by administering surveys to participating schools to measure improvements in school climate. Early results from the initiative show strong signs of promise. Schools participating in the initiative report a 53 percent improvement in overall school climate, and have seen a 46 percent decrease in suspensions.[lxxi]

While the City and DOE have begun to tacitly pilot initiatives in schools that better school climate, it is important to evaluate the effects of doing so while also maintaining traditional discipline practices and procedures that have been in place for decades and which may actually undermine reforms. Additionally, there are few accountability measures in place to ensure schools and teachers are receiving the resources and training promised. Without a clear and dedicated strategic investment plan for improving school climate there is little hope for long-term, citywide change.

In general, there has not been a commitment to expand funding for pilot initiatives to improve school climate. Since the convening of the Mayor’s Leadership Team on School Climate and Discipline in 2015, the Department of Education has begun to pilot new initiatives within some schools with the intent to reduce violence and bullying, and curb suspensions and other overly punitive disciplinary responses, and improve school climate. The convening of the Leadership Team was an important first step towards progress. Unfortunately, too few of that group’s recommendations have been implemented. Given the scale of need among New York City students for supportive schools that take a more trauma-informed approach to discipline, recent attempts at improvements must be met with a larger financial commitment to a system-wide emphasis on supportive schools.

Recommendations

With the high economic and social cost to the City of current disciplinary practices, it is important that the city adopt a strategy to support positive school climate in all schools. Research indicates that mental health professionals and guidance counselors are best positioned to respond to behavioral incidents and can drastically reduce the numbers of incidents that require involvement from police.

The DOE needs to adopt a system-wide and well-funded plan to build a positive and respectful climate in all schools, to reduce bullying, and to end harsh discipline practices that exacerbate the effects of trauma in vulnerable youth. With the appointment of a new Chancellor, the City has an opportunity to take the following steps to invest in school climate and reform discipline policies:

- Expand small social emotional learning advisories in all schools. Students who have a trusted group of peers and at least one adult to confide in have greater academic outcomes as well as more positive social attitudes and behaviors. Offering an advisory period within the school-day schedule, complete with a structured curriculum and teachers who are supported in implementing it, provides a framework to support and encourage students as they navigate social challenges.Many smaller schools already offer an advisory program and know firsthand its benefits. When each student is known well by at least one adult in the school community, this relationship can serve as anchor in preventing conflict and navigating difficult life situations. Teachers and administrators in schools that currently follow an advisory structure are ideally positioned to offer guidance and leadership in implementing in other schools.With some schools throughout the City already incorporating advisory within the school day, the DOE should survey school principals to better assess both the needs and existing resources across the system. As it offers a recommended advisory curriculum for all middle and high schools, DOE should leverage and incentivize the expertise of teachers who have successfully taught an advisory curriculum. Many of these teachers are leaders in this field and their skills and insights should guide the DOE as it determines best practices for establishing social emotional learning advisories in middle and high schools citywide.To successfully scale the advisory model, it is crucial that teachers are supported throughout the transition. While some teachers may be eager to have the opportunity to engage with students beyond the traditional academic setting to foster their emotional development, for others this new role could be intimidating. It is important that teachers are given enough time to prepare for advisory lessons, and professional development and support in understanding the advisory curriculum and how to best implement it with students.

- Provide universal mental health supports by expanding the ranks of social workers and guidance counselors in schools. The majority of in-school incidents are best dealt with by professionals experienced in collaborative problem solving and crisis de-escalation. The DOE must ensure that schools are fully staffed with trained and supported social workers and guidance counselors, and the administrators needed to support those professionals, who are given dedicated time and space in the school building to meet with students and respond to emotional or behavioral crisis events.Social workers are especially crucial for increasing the capacity of schools to connect students and families with mental health supports and resources. While guidance counselors may also be tasked with articulating student academic programs or providing college or other post-secondary counseling, social workers can be attuned to the social-emotional needs of students and provide a liaison to families who may also be in need of support or services.Other school districts provide a case study in this area. For example, an Alabama program fully subsidizes behavioral counselors for all elementary schools. Through the agreement, counselors are assigned to primarily work on improving behavior, supporting mental health, and developing non-cognitive skills in students. A review of the program found that the investment was directly linked to reduced fighting and violence in schools.[lxxii] Additionally, research based on data from the Alachua County School District in Florida found that lower counselor to student ratios significantly reduced both the recurrence of disciplinary problems and number of students involved, and that effects were greater for low-income and minority students.[lxxiii]

- Systemize trauma-informed response. With such a high proportion of New York City students living at poverty or near-poverty levels, including one in 10 students experiencing homelessness, students impacted by trauma are present in every school.[lxxiv] Trauma plays out in many ways in student behavior, and can disrupt a child’s academic trajectory. To limit the negative impact of trauma for students, it is important that more schools prepare staff to recognize the signs of trauma in children. Once those children are identified, schools should also provide training to help educators and school staff learn positive approaches to support students, such as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) and Restorative Practices.

A trauma-informed school encourages shared responsibility for student success among all student-facing school staff, rather than expecting individual teachers or social workers to “manage” student behavior. A team-based approach is supportive for both students and the adults who work with them.

Organizing staff and resources around the needs of students is essential.[lxxvi] At the school level, this can be accomplished by implementing an early warning protocol. By meeting weekly and using real time data, a team of school administrators, social workers and school climate leaders review root causes of students’ attendance, behavior, or academic concerns and seek holistic ways to support students academically, socially and emotionally. Especially when paired with small group advisories, this protocol ensures that each student is known well by at least one adult who can serve as a point of contact for students in promoting positive pro-social behaviors in school.

This early warning protocol can also be replicated at the district and central level. District leaders, reviewing data from student surveys and incident reports, are equipped to see warning signs of schools that may need additional support or resources. Oversight is critical for ensuring accountability and efforts to improve school climate should ultimately be overseen by a central office, accountable to either a Deputy Mayor or the Chancellor.

- Expand and secure funding for Restorative Practices.

In addition to the current Restorative Justice pilots in some schools, the City should adopt and sustain funding for restorative justice initiatives for a minimum three-year implementation period, and expand the initiative’s reach to approximately 300 schools. Funding would provide:- Full-time school-based restorative practices directors in 100 high need schools

- Eight district-based restorative practice program managers to provide school-based consultation on restorative justice implementation

- Regular (annual or bi-annual) professional development in school climate improvement and capacity building

To ensure consistency in implementation, DOE should ensure central-level coordination and regular progress monitoring.