Introduction

New York is a city of neighborhoods, each with its own character and its own distinctive commercial identities. Tremont Avenue in the Bronx. New Dorp Lane in Staten Island. Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn. Dyckman Street in Manhattan. Roosevelt Avenue in Queens. These are just a handful of the iconic “Main Streets” where New Yorkers congregate, socialize, shop, eat, learn, explore, and build their communities.

The mostly mom-and-pop businesses that populate and enrich these corridors—many of them immigrant-owned—are the backbone of our communities and our city. And yet, many are hurting like never before as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic shutdown caused by the virus. Bars and barber shops, restaurants and retail stores, coffee shops and bodegas—all help to define what makes New York City special and all are struggling to stay afloat as our economy sputters back to life.

This report, by New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, offers a blueprint for strengthening the city’s small businesses and the neighborhoods they call home. It is rooted in the belief that for New York City to fully recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, we must strive to build a true, five borough economy—one where every business has the support they need to thrive. Part of that means recognizing that New York City’s small businesses do not exist in a vacuum. They are embedded in a larger neighborhood and street network that is critical to their viability and success. Without active, diverse, well maintained, and easily accessible neighborhoods, businesses and communities cannot thrive in this city.

In fact, one legacy of COVID-19 may very well be a greater primacy of the neighborhood in the lives of New Yorkers, both economically and culturally. As more and more residents stay closer to home, work remotely, and avoid non-essential public transit trips, more time will be spent in their borough and neighborhood. This will place a greater demand on local streets, sidewalks, plazas, bike racks, garbage collection, seating, public bathrooms, parks, playgrounds, libraries, and so many other public goods and amenities that make our neighborhoods lively and functional.

If nothing else, the introduction of outdoor dining and open streets amidst the pandemic has offered a vision of what neighborhoods can look and feel like when the needs of pedestrians and small businesses are elevated above cars and trucks—where people have more room to dine and shop outside, bikes have more space to move safely through our streets, and the air itself is cleaner. These are lessons that should be remembered and used to advance permanent change, not relegated to history. Ensuring equal access to high-quality, well-designed, and well-maintained public spaces, then, must be a core priority in planning for New York City’s future and economic recovery.

Moreover, while COVID-19 left no city neighborhood untouched, it has ravaged communities of color most of all. Going forward, we need to center the needs of these hardest hit businesses and communities with programs and policies that address both the urgent need for immediate, tangible help, with long-term investments intended to spur entrepreneurship and lift up those who help to build wealth in every community.

For the 66,133 Main Street businesses in New York City and their 694,118 employees, the COVID-19 pandemic has been and will continue to be devastating.[1] Fortifying these businesses and neighborhoods while also supporting entrepreneurial opportunities for those displaced, will be a tall order. From Washington to Albany to New York City, from Small Business Services to BIDs to CUNY, every level of government and every city agency, nonprofit, and private company will have to work in lock-step. The future of our small businesses, the future of our local communities, and the future of our economy and workforce depends on it.

Recommendations

Recommendations for Supporting Struggling Main Street Businesses

- Create the NYC Door-to-Door Outreach Team to help small business owners tap into the remaining $150 billion in the Paycheck Protection Program.

- Provide tax credits for independent business to help cover re-opening costs now.

- Create a NYC Tech Corps to help small businesses adopt digital tools and develop an online presence.

- Abolish expeditors at the Department of Buildings.

- Allow businesses a “cure period” to address and fix violations, rather than fining them immediately.

- Allow SNAP benefits to be used at local New York City restaurants.

- Continue to relax liquor regulations and eliminate the City tax on liquor licenses.

- Permanently cap the fees charged by third-party delivery companies.

- Extend the moratorium on commercial evictions and provide legal assistance to businesses involved in legal disputes.

Recommendations for Supporting New Business and Entrepreneurship

- Create single point-of-contact for launching a business and waive permitting and inspection fees for the next 10 months.

- Create a comprehensive inventory of vacant storefronts to help entrepreneurs locate spaces quickly – free of charge

- Provide tax incentives for entrepreneurs in high-vacancy retail corridors.

- Create a “re-entrepreneurship” program connecting retiring business owners to aspiring entrepreneurs.

- Help solo entrepreneurs scale up.

- Help immigrant entrepreneurs scale up, extend into new markets, and open second businesses.

- Harness city procurement for MWBEs and task new Chief Diversity Officers with driving change.

- The City should follow the lead of Cincinnati and adopt a Minority Business Accelerator program.

- Review and reform occupational license requirements.

- Support Small Businesses that Rely on Office Workers.

Recommendations for Building Stronger Neighborhoods to Support Small Businesses

- Repurpose street space for restaurant, retail, and community use, not just automobiles.

- Don’t let vacant spaces stay vacant, be creative.

- The Department of Culture Affairs and BIDs should organize outdoor events to draw New Yorkers to commercial corridors and help artists in need.

- Invest in transit outside of Manhattan to support existing businesses and workers and to help diversify borough economies.

- Improve neighborhood mobility with a massive investment in biking and e-biking and commit to a 1,000 percent increase in ridership over the next three years.

- Tear down the paywall on the 41 commuter rail stations located within the five boroughs.

The Impact of COVID-19 on New York City’s Commercial Corridors

New York was among the first American cities impacted by COVID-19, one of the hardest hit in the world and, with good reason, has been among the most cautious in reopening its businesses and public spaces. As a consequence, the city’s economy has been utterly devastated by the pandemic, particularly Main Street, commercial corridor businesses that were not able to function remotely, have always operated on razor thin margins, and continue to be upended by the acceleration of e-commerce and e-delivery.

Of the staggering 758,000 private sector jobs that have been lost in New York City through June, 187,000 were in food services, 71,000 in retail, and 36,000 in personal services (see Chart 1).[2] Collectively, these industries have accounted for 39 percent of total job losses, despite representing just 18 percent of the city’s pre-pandemic workforce.

Chart 1: Employment in Main Street Businesses in New York City, 2000-2020

United States Department of Labor, “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages,” 2000-2020.

At least 2,800 small businesses closed permanently between March 1st and July 10th, including 1,289 restaurants and 844 retail establishments, marking a permanent loss of jobs, wages, and wealth.[3] Meanwhile, small business revenues have dropped 26.4 percent since early January, ranking New York City 40th among the 52 largest American cities.[4] With each passing day, another partially open or “temporarily” closed business teeters toward insolvency and is shuttering for good.

In theory, the Paycheck Protection Program was supposed to support these businesses, help them retain staff, and stem job losses. In practice, the program arrived too late, included too many restrictions, was ill-suited for small and urban businesses, and was poorly implemented. Though uptake has increased considerably in recent weeks and important tweaks have been implemented, for far too many small businesses in New York City, the program has proven wholly inadequate.

In fact, across the five boroughs, just 43 percent of eligible Main Street businesses received a PPP loan through the end of June. This ranged from 50 percent of personal services businesses—including barbershops, nail salons, laundromats, and drycleaners—to 41 percent of restaurants (Chart 2).[5]

Chart 2: Share of Main Street Businesses that Received a PPP Loan

| Industry | PPP Loans Received | Eligible Businesses |

Share receiving a PPP Loan |

| Personal Services | 6,309 | 12,744 | 50% |

| Bars | 725 | 1,576 | 46% |

| Retail | 14,946 | 34,780 | 43% |

| Restaurants | 8,590 | 21,195 | 41% |

| Main Street Businesses | 30,570 | 70,295 | 43% |

U.S. Department of Treasure. “SBA Paycheck Protection Program Loan Level Data,” July 6, 2020.

U.S Census Bureau. “County Business Patterns,” 2018.

The majority of these Main Street businesses are run by people of color and immigrant New Yorkers and it is precisely these communities that have been hit hardest by COVID-19. Foreign-born New Yorkers own approximately 70 percent of independent commercial corridor businesses in Queens, 66 percent in the Bronx, 63 percent in Brooklyn, 59 percent in Staten Island, and 57 percent in Manhattan (see Chart 3).[6] Meanwhile, 16 percent of Main Street businesses in the Bronx, 12 percent in Brooklyn, and 8 percent in Queens are black-owned.

Chart 3: Share of Main Street Businesses owned by Foreign-Born New Yorkers

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

These same dynamics and demographics extend to their employees as well, with 73 percent of Main Street jobs in New York City held by people of color, 53 percent by immigrants, and 29 percent by non-citizens.[7] This concentration helps explain, in part, why unemployment rates among Black (24.3 percent), Latinx (22.7 percent), Asian (21.7 percent), and foreign-born (20.6 percent) New Yorkers are nearly twice as high as White New Yorkers (13.9 percent).

Chart 4: Change in Unemployment Rate, February to June, by Demographic Group

Office of the Comptroller from Current Population Survey.

With unemployment surging, New Yorkers struggling, and small businesses on the brink, it is vital that we support and stabilize our commercial corridors in every borough and every neighborhood. That should include an emergency cash assistance fund for immigrants and immigrant-owned businesses left out of the federal stimulus packages to date.

Unlike finance, tech, or insurance, Main Street businesses are not concentrated in just a handful of neighborhoods in a single borough. They are spread across every corner of the city, with 63 percent of the 66,133 Main Street businesses and 47 percent of the 694,118 Main Street jobs located in Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Staten Island.[8]

These small businesses serve New Yorkers where they live and where they work. These are the places where we start and end our days, where we meet new people and old friends, where we establish a sense of place and home. They help to foster and reflect the quirks and character of each of our city neighborhoods.

And yet, these same businesses and community anchors have been struggling for years under the weight of rising rents, ever-growing red tape, and changing technology. While the number of Main Street businesses grew by 36 percent in Brooklyn, 28 percent in Queens, 17 percent in the Bronx, 16 percent in Staten Island, and 10 percent in Manhattan from 2009 to 2019 (see Chart 5) and were responsible for 95,549 of the 428,310 new jobs created outside of Manhattan, commercial vacancies had been surging even prior to the global pandemic.

Chart 5: Growth in the Number of Main Street Businesses, 2009-2019

Now, with the acceleration of e-commerce, mandates around social distancing, and the accumulation of debt, it will be even more challenging for businesses to reopen their doors and reinvigorate empty store fronts. This is particularly true for small businesses, who lack the retained earnings and access to capital of larger corporations and franchises.

If these small businesses are allowed to fold and be replaced by chain stores, it will utterly upend the character of New York City’s neighborhoods and destroy local economies, particularly in low-income, BIPOC, and non-Manhattan neighborhoods.

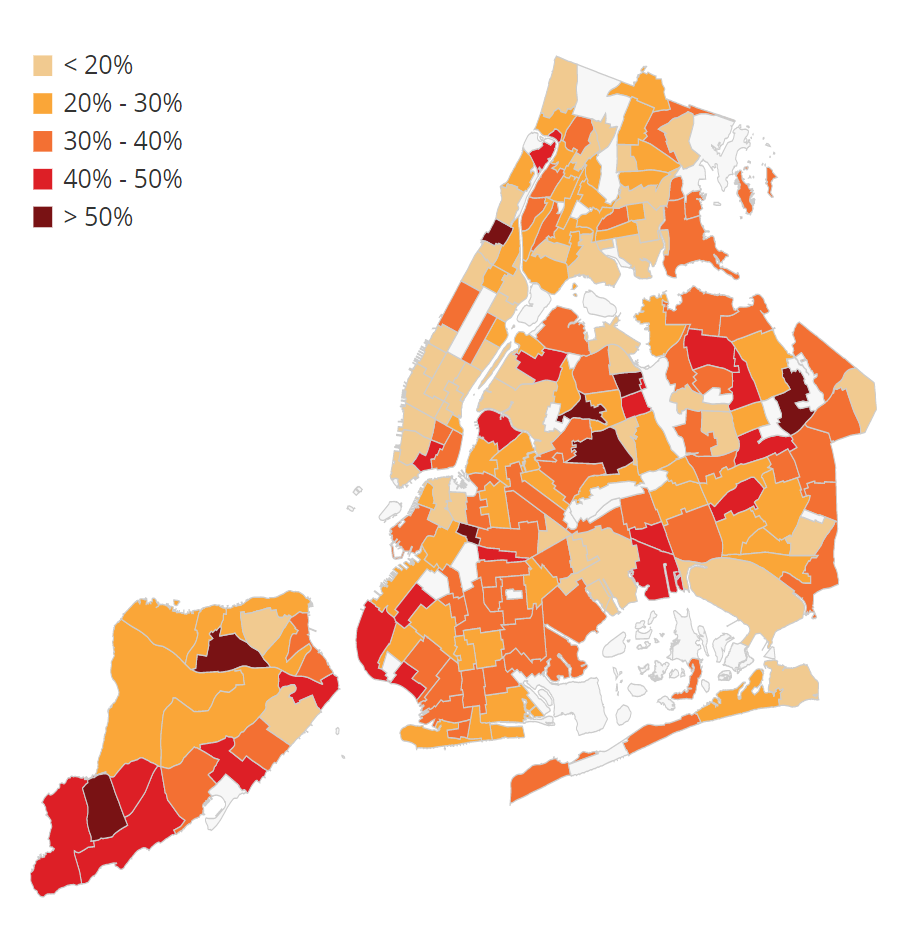

In fact, while just 18 percent of the city’s total private sector workforce is employed in small businesses of fewer than 20 workers, this varies considerably throughout the five boroughs. In 30 neighborhoods in Queens, 27 in Brooklyn, ten in Staten Island, eight in the Bronx, and seven in Manhattan, more than 30 percent of local jobs are in small businesses (see Chart 6). This concentration of small business employment is particularly evident in North Corona (63 percent of local jobs in businesses with fewer than 20 employees), Westerleigh (56 percent), Prospect Heights (52 percent), Elmhurst-Maspeth (51 percent), Rossville-Woodrow (51 percent), Oakland Gardens (51 percent), Hamilton Heights (51 percent), and Middle Village (50 percent).

Chart 6: Share of Local Jobs in Businesses with Less than 20 Employees

United States Census. “LEHD Origin-Destination Employment Statistics,” 2017.

In the weeks and months ahead, the City, State, and Federal government cannot allow vacancies to accumulate in these neighborhoods or any others in the five boroughs. To support existing businesses, spur entrepreneurship, keep our commercial corridors vibrant, and strengthen our city, we must pursue the following action plan:

Recommendations for Supporting Struggling Main Street Businesses

1. Create the NYC Door-to-Door Outreach Team to help small business owners tap into the remaining $150 billion in the Paycheck Protection Program.

After an additional infusion of $320 billion in April, the PPP loan and grant program is now left with $150 billion in untapped funds. Given that only 12 percent of New York City businesses and sole-proprietors have received a PPP loan, it is clear that a huge number have not taken advantage of this program.[9] What they need is swift, hands-on support, and the City should provide it.

The City’s Small Business Services, in collaboration with BIDs and other business associations, should create the NYC Door-to-Door Outreach Team and knock on the door of every Main Street business, reach out to proprietors, and help them prepare paperwork for the PPP program. Neighborhoods that received the fewest PPP loans should be targeted and prioritized. These businesses are entitled to these funds and stand to gain a sizeable infusion of capital. The City should move rapidly to increase marketing and promotion and help business owners leverage the remaining dollars of this centerpiece national relief program.

Beyond the PPP program, the Outreach Team can help distribute information on the ever-changing protocols regarding closing and reopening, street seating, changes to permitting, fines, fees, and taxes, and many other rules and regulations. As part of this effort, the City should build a multi-lingual, multi-ethnic team—modeled after their Tenant Support Unit—to drop off fliers, make calls, and operate an information hotline.

2. Provide tax credits for independent business to help cover re-opening costs now.

As small retail, restaurant, and personal services businesses begin to reopen, they are having to reconfigure their spaces for social distancing while also coping with a smaller customer base. To help these Main Street businesses, the City should create refundable business income tax credits for small, independent, and locally-owned businesses with annual revenue below $5 million. The tax credits will allow them to recoup dollars spent on reconfiguring stores, installing safety equipment, outdoor seating, and any other expenses related to re-opening safely.

3. Create a NYC Tech Corps to help small businesses adopt digital tools and develop an online presence.

Small Business Services should pilot a NYC Tech Corps to help Main Street businesses develop a web presence, expand online sales, and implement digital payroll, sales, and inventory tools. Rather than offering time-consuming classes and tutorials, the Tech Corp would work directly with business owners to design websites, to help purchase business software, and to set-up these tools.

In addition to a full-time staff, the Tech Corps could be fortified by volunteers from New York’s technology sector as well as qualified and multilingual students from CUNY and DYCD internship programs. It should also work in partnership with local business schools, following the example of the “Leading to Grow” program in Birmingham, England, where Aston University and the regional economic development organization are working together to promote digital technology adoption. Local businesses receive tailored support to identify relevant technologies and develop the management capabilities needed to implement them.[10]

4. Abolish expeditors at the Department of Buildings.

There is perhaps no greater indictment of the City’s regulatory superstructure than the existence of expeditors. Called “Filing Representatives” by the Department of Buildings, these private, for-hire fixers have been engrained into the fabric of DOB, charging fees to help would-be business owners navigate the agency and “expedite” the approval process. They should be banned, and replaced by a team of in-house Business Advocates to solve problems for businesses free of charge.

5. Allow businesses a “cure period” to address and fix violations, rather than fining them immediately.

Moving forward, any business violation that does not pose an immediate hazard to the public should be granted a 30-Day “cure period” to address and rectify the issue. Rather than taking a punitive approach and issuing a fine, the City should grant all businesses the opportunity to remediate problems.

6. Allow SNAP benefits to be used at local New York City restaurants.

To support local restaurants and improve access to food, the federal government and New York State should enable SNAP benefits to be used at local, non-chain restaurants.

First, New York State should join Arizona, California, Hawaii, Illinois, and Rhode Island and opt into the federal Restaurant Meals Program, which allows those who cannot cook for themselves or have limited access to a kitchen—including the disabled, homeless, and seniors—to use their Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits to purchase discounted restaurant meals.

Second, Congress should expand this program to enable all SNAP beneficiaries to use their benefits at restaurants, and the City should recruit trusted community messengers fluent in multiple languages to provide updated information on SNAP’s expanded reach and other federal benefits. The allowance could sunset in 12-months, enabling lawmakers to analyze its efficacy and determine whether it should be extended beyond the pandemic.

7. Continue to relax liquor regulations and eliminate the City tax on liquor licenses.

During the pandemic, liquor regulations have been eased, allowing bars and restaurants to sell alcohol to go. These policies should continue and be expanded moving forward.

While many communities are reluctant to issue new or expanded liquor licenses, the challenge is likely to be too few restaurants and bars, not too many, as the economy reopens. To help these businesses make ends meet, the State should expedite the issuance of new liquor licenses, continue to ease regulations on alcohol pick-up and delivery, and repeal the recent executive orders that a) require food to be purchased along with alcohol and b) place the onus on businesses to enforce open container laws.

To help in these efforts, the City should ease regulations on drinking in designated outdoor areas and eliminate its 25% tax on liquor licenses.[11]

8. Permanently cap the fees charged by third-party delivery companies.

In mid-May, the City Council voted to temporarily cap the fees and commissions that restaurants paid to companies like Uber Eats and Seamless. Delivery fees are now temporarily capped at 15 percent and non-delivery services at 5 percent.[12]

Prior to the pandemic, restaurants had been paying as much as 30 percent on delivery commissions—an exorbitant sum for an industry that operates on razor-thin margins. This can no longer be tolerated. To help these businesses both during the pandemic and beyond, caps on third-party delivery companies should be made permanent.

9. Extend the moratorium on commercial evictions and provide legal assistance to businesses involved in legal disputes.

To protect struggling businesses owners and help keep them afloat, Albany should extend its moratorium on commercial evictions, which expires on August 20th. The moratorium should continue until the city is fully reopened—as is currently the case with residential evictions, thanks to the Tenant Safe Harbor Act.

Meanwhile, the SBS Commercial Lease Assistance program—which, confoundingly, was cut in the recent budget—should be relaunched to provide legal representation to small businesses in commercial lease disputes and negotiations.[13]

Finally, to support business in the hardest hit neighborhoods, the City should look to Detroit’s “Neighborhood Strategic Fund”—a partnership between government and major philanthropic organizations—which is currently providing three-months of rent support for businesses in 10 high-priority commercial corridors in the Motor City.[14]

Recommendations for Supporting New Business and Entrepreneurship

10. Create single point-of-contact for launching a business and waive permitting and inspection fees for the next 10 months.

To expedite and facilitate the launching of a new business (or the modification of an existing commercial space), all businessowners should be assigned a Business Advocate to help them navigate the City bureaucracy and provide assistance with construction permitting, health and safety inspections, liquor license applications, among others. The Business Advocate would serve as a personal representative and case manager for all City interactions, speeding permitting, saving small businesses money, and doing away with costly, for profit expeditors.[15] The corps of business advocates must be multilingual and should be placed within the Mayor’s Office—rather than SBS—so that they have the authority to navigate the inter-agency nature of their job.

In conjunction with this Business Advocate, the City should take cues from San Francisco and provide a single internet portal where business owners can find permitting and licensing requirements and submit necessary paperwork for all agencies and levels of government.[16]

More immediately, the City should waive permitting and inspection fees for businesses that take over a vacant space anytime within the next 10 months. This will incentivize businesses to act fast and begin to revive our commercial corridors.

11. Create a comprehensive inventory of vacant storefronts to help entrepreneurs locate spaces quickly—free of charge.

To support small businesses and quickly fill vacancies, the City should make it far easier for aspiring entrepreneurs to locate storefronts that are well-suited to their needs and set them up for success. As it is, many small businesses have to hunt for spaces through word of mouth or pay costly broker fees to learn what is available and what infrastructure is installed on site. This costs would-be entrepreneurs time and money.

To this end, SBS should work to fundamentally up-end the status quo and create a public-facing inventory of all vacant spaces free of charge, providing information on square-footage, building systems, and any equipment (like stoves) that are already in place.

To populate this database, property owners should be required to alert the City as soon as a commercial space becomes vacant and to share the dimensions, building systems, and currently installed equipment within the space.

12. Provide tax incentives for entrepreneurs in high-vacancy retail corridors.

The City should provide tax credits for aspiring entrepreneurs in retail corridors with persistently high vacancy rates. Small Business Services, working with the Department of Finance, would identify and map retail corridors and monitor vacancy rates. Business owners locating in corridors with vacancy rates above a certain threshold could receive a credit against either the Commercial Rent Tax (in that area of Manhattan to which it applies) or the real property tax (requiring the landlord to calculate that share of rent attributable to retail space when the space is leased).

Even before COVID-19, vacancies were on the rise in New York City. As detailed in Retail Vacancy in New York City, a September 2019 report by the NYC Comptroller’s Office, vacant retail space more than doubled over the last decade, rising to 11.8 million square feet in 2017, up from 5.6 million square feet before the Great Recession.

The COVID-19 pandemic will only increase these already high rates, making it that much more urgent for the City to act.

13. Create a “re-entrepreneurship” program connecting retiring business owners to aspiring entrepreneurs.

In the New York City metro area, nearly half of business owners are over the age of 55 and nearing retirement.[17] Even in normal times, many would simply close their business upon retirement, with little thought to succession and few prospective buyers. This natural evolution too often deprives communities of important sources of wealth creation, as businesses close and the jobs they supported disappear. Today, amidst the pandemic, these closures are likely to be accelerated, with many older business owners preferring to close their business rather than muddle through the challenging and uncertain months ahead.

To avoid this outcome, preserve important anchors of the community, and forestall the loss of existing jobs, customers, and suppliers, the City should launch a Re-Entrepreneurship program, modeled after Quebec, Canada and Catalonia, Spain.

The Reempresa program in Barcelona, for instance, connects existing business owners to aspiring entrepreneurs. Financial advisors rigorously evaluate both the fiscal health of the companies and the qualifications of the “re-entrepreneurs” before they are granted access to the online marketplace. When a match is made, these advisors help manage the transfer and provide business training for new owners.

Small Business Services should explore a similar re-entrepreneurship program in New York City. They can partner with local chambers of commerce and BIDs to survey business-owners and encourage them to prepare succession plans. They can also develop an online marketplace similar to Reempresa and leverage their suite of financial and entrepreneurial services to assist with these business transfers. Special assistance should be provided to women and minority re-entrepreneurs as well as CUNY MBAs, in order to ensure that our city’s business owners reflect the diversity of our residents.

14. Help solo entrepreneurs scale up.

Nearly one million businesses in New York City are “non-employers”—often independent contractors or home-based businesses that are unincorporated. From 2004 to 2018, the number of solo entrepreneurs in New York City grew steadily, from 677,436 to 946,373. Of these, nearly 57 percent were minorities, compared to 34 percent of business-owners who maintain a payroll.[18]

Though a majority of these sole-proprietors have no intention of expanding, studies have found that 5 percent will become an employer-business or will be acquired by one. Still others are poised for growth, but are deterred by the increased regulations, responsibilities, and paperwork required to bring on a first employee. Helping solo entrepreneurs overcome these hurdles to expansion is a promising strategy for boosting New York’s economy and diversifying the business landscape.

While SBS and EDC do offer a number of high-quality business assistance programs, the majority of these focus on entrepreneurs starting new businesses, not solo entrepreneurs looking to scale up. The City should partner with Freelancers Union and other service providers to improve outreach to these solo entrepreneurs and to develop a Business Acceleration Unit dedicated to helping them expand. The City should also work with micro-lenders and credit unions to guarantee small loans for sole proprietors looking to make their first hire—as well as for purchasing equipment and obtaining affordable workspace.

15. Help immigrant entrepreneurs scale up, extend into new markets, and open second businesses.

The story of Xi’an Famous Foods is a popular one. Father opens up a superlative restaurant in a basement food court of a Flushing mall. Son goes to top American university, majors in business, partners with his father, and expands the tiny restaurant into a small empire.

While this is perhaps the most notable in the genre, it is hardly unique. To spur this type of business development, Small Business Services should help immigrant entrepreneurs expand into new markets and open new stores. Marketing, promotion, and translation services should be offered to help reach new customers beyond their immediate neighborhood and the City should pilot a new program to help proven, successful entrepreneurs open second businesses throughout the city, expediting permitting and helping with the costs of modifying these new spaces.

16. Harness city procurement for MWBEs and task new Chief Diversity Officers with driving change.

The city should harness its vast, $20 billion procurement budget to better support local, independently owned retailers and MWBEs, especially in communities hardest hit by COVID-19. By shifting more purchases to local vendors—and encouraging other local institutions and larger businesses to do the same—small businesses could be meaningfully aided in both the short- and long-term. The City should be creating aggressive MWBE goals on competitive city contracts and create a preference for MWBEs on non-competitive contracts.

Helping to drive this effort should be the City’s new Chief Diversity Officers within each agency, positions that Comptroller Stringer has long advocated for and that Mayor de Blasio has now committed to hiring. CDOs can and should function as city government’s executive level diversity and inclusion strategists, driving the representation of people of color and women across government, tracking and overseeing the city’s M/WBE programs, and determining whether agencies’ daily practices are equitable. The agency CDO can finally begin to tackle long-standing disparities that are now coming into stark relief—from analyzing how taxpayer dollars are spent through an intersectional lens to removing barriers to doing business with the city, to making sure public service is a viable option for people from diverse backgrounds and experiences.

17. The City should follow the lead of Cincinnati and adopt a Minority Business Accelerator program

In Cincinnati, the Regional Chamber’s Minority Business Accelerator offers local businesses strategy, guidance, capital, and networking opportunities. Working with major corporations that are committed to “more inclusive procurement practices,” the MBA program has helped nearly 70 local MWBEs scale up and tap into private sector supply chains.

In New York City, Small Business Services and the borough chambers of commerce should create their own Minority Business Accelerator. Pairing local MWBEs with locally headquartered corporations, the City can help diversify private sector supply chains and help minority-owned businesses grow.[19]

18. Review and reform occupational license requirements

Barbers, masseuses, nail specialists, cosmetologists, inspectors, interior designers. For each of these occupations, New York State maintains onerous licensing requirements and bureaucratic hurdles before one can begin work or open a business.[20]

Earlier this year, the State of Florida passed a sweeping bill to “loosen or abolish occupational licensing regulations across more than 30 professions, cutting red tape for potentially thousands of workers in the state.”[21] To better support aspiring entrepreneurs, New York should follow suit.

19. Support Small Businesses that Rely on Office Workers.

Many coffee shops, bars, and restaurants in Manhattan, downtown Brooklyn, Long Island City, and other neighborhoods depend on office workers for a majority of their revenue. For these businesses, the rise of remote work represents an existential threat.

To support these businesses, the City must make a concerted effort to sustain its office districts:

-

Support and cultivate growing industries by accelerating the roll-out of 5G and continuing to invest in the life sciences.

In recent years, New York has seen huge growth in healthcare, tech, architecture, design, engineering, advertising and many other fields. In the medium- to long-run, this pandemic should benefit many of these industries. For instance, the acceleration of e-commerce, e-health, e-communications, etc. will benefit tech companies, the reconfiguration of ventilation systems and public spaces should employ many engineers, architects, and designers, and the importance of a robust healthcare system has never been more obvious.

To help bolster these fields, New York City should strengthen and modernize its core infrastructure, especially broadband. Accelerating the rollout of 5G across the city, for instance, will significantly aid the development of robotics, telehealth, logistics, and many other fields that depend on extraordinarily fast internet speeds for product development and distribution.

The City should also redouble its investment in bioscience, with the goal of becoming the capital of public health and research in the world. Building off of the Cornell Tech model, the City can provide space for a new university exclusively dedicated to the life sciences. Repurposing vacant department stores or malls offers one possible avenue for building out a new campus.

-

Recruit back office operations back to New York City.

In recent decades, many New York City finance, legal, accounting, and tech companies have relocated their back-office operations to low-rent cities. COVID-19 offers an opportunity to lure them back. With a potential fall in office demand and declining rents, it may now be affordable to bring these middle-class jobs back, especially for firms who own their buildings or are in long-term leases and now have spare capacity. To assist in these efforts, the City should launch a “Back to NYC” pilot, targeting those companies operating in low-cost states now being ravaged by COVID-19.

-

Support Residential Conversions and Population Growth in Midtown and Downtown.

While many unknowns remain, it seems likely that one of the legacies of COVID-19 pandemic will be a reduced reliance on traditional office space as a way to do business, as more and more people choose to work remotely. This prospect raises profound challenges and opportunities for New York City, particularly in areas of the city—like Midtown Manhattan—that are all but defined by gleaming office towers and the bustling workforce that fill them every day, from bankers and advertisers, to the porters and building workers who keep them working.

The City needs to take an intelligent approach to this new dynamic that focuses on long-term planning, and is informed by the successes and failures of Lower Manhattan. In the years following 9/11, Lower Manhattan slowly rebuilt its office base while experiencing rapid growth in its residential population. The number of people living in Community Board One jumped from 34,420 to over 70,000 from 2000 to 2016, with a significant number of office spaces converted to residential.[22] These residential conversions helped provide a 24/7 community to support all variety of local businesses—while also introducing new demands for schools and open space.

To prepare for continued residential growth in our business districts and build an expanded customer base for local businesses, the City should closely track residential conversions and build out new schools, libraries, and parks in Midtown, Downtown, and other office districts. The goal should be to create vibrant, livable neighborhoods that are based on sound, long-term planning.

Reimagining our Commercial Corridors and Neighborhoods

New York City’s small businesses and commercial corridors do not exist in a vacuum. They are embedded in a larger neighborhood and street network that very much determines their viability and success. How do people get to the commercial corridor? What anchors and amenities attract them to the avenue? How much time do they wish to spend there?

Active, diverse, well-maintained, well-populated, and easily accessible neighborhoods are essential to the survival and success of local businesses and communities. We cannot support our small businesses without also supporting the broader neighborhood where they flourish.

New York is, in fact, a city of neighborhoods. The corner store and coffee shop, the local library, playground, and elementary school, the park, sidewalks, and streetscapes. These places and spaces give color to our everyday lives and provide the lens through which we assess the health, welfare, and vitality of our city as a whole.

If there is any silver-lining to the COVID-19 crisis, it is that our neighborhoods have come into sharper focus in recent months, and investing in their maintenance and vitality has become even more essential. As New Yorkers stay close to home, work remotely, and avoid non-essential public transit trips, more time is being spent within the borough and neighborhood. This could ultimately be beneficial for local, Main Street businesses, provided they can weather the pandemic and their neighborhoods are equipped to handle the continued influx of local activity.

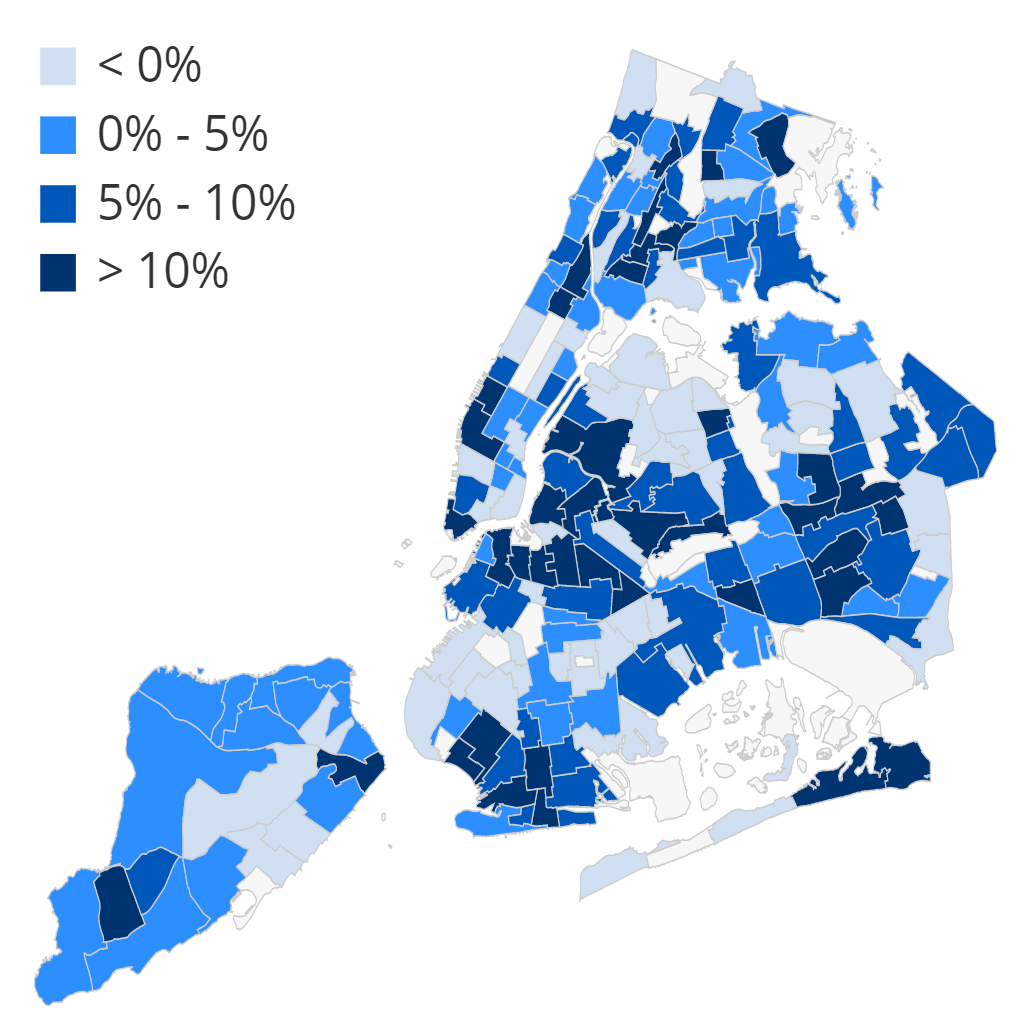

Over the last decade, in fact, 40 New York City neighborhoods saw their population grow by more than ten percent and 97 neighborhoods experienced local employment growth of over 20 percent (see Chart 7). This surge in activity had produced more customers, more businesses, and more vibrant commercial corridors. It has also strained existing infrastructure and placed pressure on streets, sidewalks, plazas, bike racks, garbage collection, seating, water fountains, bathrooms, parks, playgrounds, libraries, and so many other public goods and amenities that make our neighborhoods lively and functional. Part of this is a function of gentrification, as more and more traditional communities of color saw an influx of new people and new businesses over the last decade or so. Going forward, it is essential that the city work to minimize displacement by building more affordable housing that is actually affordable to working people, and creating programs that connect local residents to new, local jobs.

Chart 7: Employment and Population Growth in New York City Neighborhoods, since 2010

| Population Growth

2010-2018 |

Employment Growth

2010-2017 |

|---|---|

|

|

Population: NYC Department of City Planning. “Neighborhood Tabulation Areas,” 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

Employment: United States Census. “LODES Dataset”, 2017. Only includes private sector employment.

Amidst the global pandemic, the strictures of social distancing, and travel limitations, these pressures and strains on city neighborhoods have only grown more profound. To counter the ill effects of COVID-19, then, the city’s streets and neighborhoods will be an important arena for action.

Now more than ever, more space is needed for seating and shelving to assist local restaurants, retail, barber shops, and nail salons. More space is needed for social distancing and lining up for testing and temperature checks. More space is needed to ensure equitable access to parks, plazas, and playgrounds and to create more magnetic and vital neighborhoods. And more space is needed for bus and bike lanes to help people travel around their neighborhoods as subway use is curtailed.

Main Street business owners, employees, and customers are, in fact, poorly served by our hub-and-spoke subway system and are heavily dependent on alternative forms of transit. Nearly 35 percent of those working along non-Manhattan commercial corridors walk, bike, or ride the bus to work—compared to less than 20 percent of all other commuters (see Chart 8). To help these employees get to work and to help their businesses expand their customer base, then, improving and rethinking our five borough transportation network is key.

Chart 8: Employees of Non-Manhattan, Main Street Businesses are much more likely to walk, bike, or ride the bus to work

United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

Moreover, as we improve access to our commercial corridors, it is essential that we also maintain activity, so that they remain places where people want to travel and spend their time. To this end, we cannot allow vacancies to accumulate and we cannot allow street life to wane. Investments in entrepreneurship (as discussed above), community facilities, public art and performances, and outdoor markets and retail, will be key.

Recommendations for Building Stronger Neighborhoods to Support Small Businesses

20. Repurpose street space for restaurant, retail, and community use, not just automobiles.

The recent influx of outdoor dining has transformed commercial corridors and offered a vision of street spaces that serve a wider variety of needs and uses beyond driving and parking. Moving forward, these “open restaurant” permits should be automatically renewed each year, spanning from March 15th to November 1st.

Thus far, approximately 8,000 businesses have signed up for outdoor seating. This is a far cry from the 22,000 bars and restaurants that populated New York prior to the pandemic and enrollment has been particularly low in neighborhoods like Flushing, Sunset Park, and Midtown.[23] The City must do a better job enrolling the other 14,000 business owners and, even more urgently, expand the program to clothing stores, bodegas, nail salons, and other businesses that could display their products and offer their services outside of their storefront.

More curbside space should also be designated for pick-ups, drops offs, loading, unloading, and garbage storage along commercial corridors. This will help businesses and customers, reduce double parking in the city, and declutter our sidewalks.

In conjunction with these reforms, the City must begin widening commercial and residential sidewalks to make them more passable for shoppers, strollers, and wheel chairs and provide more space for crucial amenities like street seating, street vendors, bus shelters, garbage bins, bike parking and public bathrooms. These sidewalk expansions can be rapidly and affordably built out by expanding into the roadway with the use of planters and bollards.

To help coordinate these street improvements, design standards should be quickly established and a DOT employee should be co-located at every BID office to assist with the rollout and oversite of new public spaces.

More broadly, the City should create a vast system of “shared streets” where cars are only permitted to travel five miles per hour in residential neighborhoods and select commercial streets. As in Barcelona and Montreal, these shared streets can be integrated through a larger network where car travel is largely confined to major thoroughfares, while quieter residential and commercial blocks are primarily left to bikes, pedestrians, cafes and restaurants, and leisure activities (see below). The latter is well suited for much of Manhattan as well as the many grid sections of Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Queens.

Love, Patrick. “Superblocks are transforming Barcelona. They might work in Australian cities too,” The Conversation, September 17, 2019.

21. Don’t let vacant spaces stay vacant, be creative.

From large malls and department stores to small retail frontage, the pandemic will likely lead to an uptick in vacant space in various neighborhoods. Moving forward, the City should work with landlords, take advantage of low rents, and consider ways to help fill these spaces.

In the near-term, many can and should be leveraged to provide additional public school space as the City struggles to re-open safely. In the long-term, other civic uses might include libraries, artist studios, community centers, and childcare centers. Meanwhile, in larger spaces, subsidizing LifeScience labs and green tech startups, modelled after New Lab at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, could kickstart new industries in the five boroughs.

Finally, the City should work with CUNY colleges and other universities with more secluded campuses—like St. Johns, Manhattan College, York College, Fordham, and others—to build out classrooms along commercial corridors in order to bring more people, street life, and customers to these neighborhoods.

22. The Department of Culture Affairs and BIDs should organize outdoor events to draw New Yorkers to commercial corridors and help artists in need.

The Department of Cultural Affairs, BIDs, and artists and arts organizations throughout the city should organize music, dance, theater, and entertainment pop-ups along every commercial corridor in the five boroughs. Partnering with Make Music New York, the MTA’s Music Under New York—which currently has 350 participating groups that perform in the subway—and others, every BID can sponsor regular performances throughout August and September.

Artists can perform and show their work at plazas and other public spaces where social distancing can be properly upheld. The Mayor’s Office of Film, Theater, and Broadcasting, meanwhile, should provide streamlined permitting for these outdoor cultural events, as it already does for film shoots.

23. Invest in transit outside of Manhattan to support existing businesses and workers and to help diversify borough economies.

New York City’s hub-and-spoke subway system is poorly suited for our growing city, for our five borough economy, and for the business owners, workers, and customers who travel to our commercial corridors each day. To improve job access, expand customer bases, and reduce car dependency, then, we must dramatically improve non-Manhattan transit.

This should begin with the City adding 100 miles of bus lanes over the next two years and the MTA continuing its efforts to redesign the bus network to better reflect contemporary commuting patterns. It must also include major improvements in our bike network and commuter rail integration (see below), as well as long-term investments in expanding subway service and reviving moribund lines.

Investing in non-Manhattan transit will not only support Main Street businesses, but also attract higher-wage companies and industries, which have trouble attracting and retaining talent due to their location beyond the city’s transit hubs. While tech, design, and film businesses have rapidly expanded throughout the five boroughs, high-paying jobs are still very much concentrated in Manhattan. This is largely driven by the centrality, office density, and extraordinary transit network that flow millions of workers on and off the island each day.

And while many business owners have tried to open offices in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx, many have quickly realized that it is faster and easier for employees living in Crown Heights or Corona to get to Midtown than it is for them to travel within their own borough to job sites in Williamsburg or Astoria.

To address these transit gaps, help stimulate new business development, and improve travel for business owners, employees, and customers, it is imperative that the City and MTA dramatically improve transportation outside of Midtown and Downtown.

24. Improve neighborhood mobility with a massive investment in biking and e-biking and commit to a 1,000 percent increase in ridership over the next three years.

As New Yorkers remain close to home and reorient their worlds around what’s local, the bicycle is poised to be the transit mode of New York City’s future. To help residents circulate around their neighborhoods and boroughs and to help workers travel to jobs sites throughout the five boroughs, the City must set an iron commitment of increasing bike ridership by 1,000 percent in the next three years.

Given that 75 percent of auto trips and 55 percent of transit trips in NYC are under five miles, supplementing these commuting and leisure trips with bikes and e-bikes is certainly viable.[24] To do so, the City will have to quickly design and build out a network of continuous, connected, and conflict-free bike lanes that accommodates not just the experienced rider, but that is safe, robust, and intuitive enough to attract the large number of New Yorkers who are interested in riding and bike commuting, but wary of the city‘s busy streets. Specifically, the City should:

- Increase the number of protected bike lanes by 100 miles in the next two years and by 350 miles in the next five yearswith a deliberate effort to create an interconnected and robust network of lanes. To this end, the DOT’s Green Wave Plan should be fully funded and accelerated and the Regional Plan Associations’ Five Borough Bikeway should be pursued.

- Install a dozen miles of bike priority streets.Common in Belgium and the Netherlands, the City should create streets throughout the five boroughs where cars are permitted, but only as “invited guests” that must follow slowly behind bikes. These streets should be color-coded and have clear symbols to mark that they are dedicated to bikes.

- Expand Citi Bike to all five boroughsand provide a deep subsidy for low-income New Yorkers.

- Follow the lead of Paris and Italy and generously subsidize the purchase of e-bikes. Whether traveling long distances or traversing steep bridges, e-bikes enable riders of all ages and fitness levels to travel around the city. In response to the COVID-19 crisis, the Italian government introduced a 70-per-cent subsidy (capped at $540) for the purchase of new bikes and e-bikes.[25]New York should pursue similar measures.

- Mandate that all office buildings and schools provide bike storage inside buildings, as well as secure bike racks on every commercial block. Offices should also be required to allow bicycles on passenger elevators, not just freight elevators.

- Repave and reconstruct roadsto ensure that bike lanes are not pockmarked with unsafe cracks and potholes. As part of this effort, the pavement conditions of bike lanes should be made into a separate category in the Mayor’s Management Report and continuously monitored by the City’s inter-agency Street Conditions Observation Unit.

- Install traffic cameras to monitor and enforce bike lanesso that they remain free of obstruction and illegal parking. New York City bus lanes are already monitored via camera enforcement and cities like London are expanding these capabilities for bike infrastructure. xviii

- Repurpose a lane of traffic on the East River bridges for biking. Traffic on the East River Bridges has been falling for decades and will decline even faster whenever Congestion Pricing is implemented. In response to these trends, the City should dedicate a lane of traffic exclusively for bikes, beginning with the Brooklyn and Queensboro Bridges.

- Offer classes to new and inexperienced cyclists to help them ride safely in the city. Across the five boroughs, there are many New Yorkers who are interested in biking, but lack the experience and confidence to ride. Organizations like Bike New York provide a wide range of classes for new riders to help them get started. The City should help to promote these classes and provide them with funding to help expand their offerings.

- The United States Senate should pass the Moving Forward Act, which would extend commuter tax benefits to include bikes, e-bikes, and bike share memberships. These benefits are already available to car and public transit commuters and would provide bike riders with a pre-tax benefit of up to $54/month to cover commuting costs.

25. Tear down the paywall on the 41 commuter rail stations located within the five boroughs.

Flushing, Jamaica, Queens Village, East New York, East Harlem, Melrose, Tremont. While these neighborhoods may be scattered across Queens, Bronx, Brooklyn, and Manhattan, they share many things in common. First, they are home to more Main Street and frontline workers than nearly any neighborhoods in New York City. Second, they each have LIRR and Metro-North stations that provide high-quality transit service, but are almost entirely unused due to prohibitively high fares.[26]

Now is the time to tear down this commuter rail paywall and dramatically improve transit access and equity. With suburban, white collar commuters likely to work from home for the immediate future, there is a distinct opportunity to open up the 41 Metro-North and LIRR stations located within the five boroughs. In fact, 62 percent of all commuter rail riders are employed in remote-work industries, second only to ferryboats (68 percent) among transit modes.[27]

Moving forward, the fare for all in-city trips should be reduced to the price of a MetroCard and transfers between commuter rail, subway, and bus should be free. Free transfers should also be extended to suburban commuters and trains should run at a minimum of every 15 minutes all day, every day, seven days a week around the city hub.

Endnotes

[1] United State Department of Labor, “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages,” 2019. “Main Street” industries include personal services (NAICS codes 8121, 8123, and 8129), restaurants (NAICS code 7225), bars (NAICS code 7224), and retail (NAICS codes 44-45).

[2] New York State Department of Labor. “Current Employment Statistics: Data for New York City,” June 2020.

[3] Data on restaurants and retail was provided by Yelp to the Office of the Comptroller.

The overall small business number is from: Haag, Matthew. ”One-Third of New York’s Small Businesses May Be Gone Forever.” New York Times. August 3, 2020.

[4] Womply, via tracktherecovery.org

[5] For the PPP loans, the following ”business types” are excluded: ”independent contractors,” ”self-employed individuals,” and ”sole proprietorships.” These are generally considered ”non-employers,” are not included in the Census’ Community Business Patterns dataset, and generally do not have storefronts.

[6] United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.

“Main Street” businesses are found under the following industry codes: 4670-5790, 8680, 8690, 8970-9070, and 9090.

[7] ibid

[8] United State Department of Labor, “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages,” 2019.

[9] Office of the New York City Comptroller. ”The Failure of the PPP in NYC,” July 15, 2020.

[10] Donahue, Ryan and Joseph Parilla. “Deploying industry advancement services to generate quality jobs,” Brookings Institute. July 23, 2020.

[11] https://www1.nyc.gov/site/finance/taxes/business-retail-beer-wine-and-liquor-license-tax.page#:~:text=The%20tax%20is%2025%25%20of,days%20in%20that%20tax%20year.

[12] Lucas, Amelia. ”Local lawmakers provide struggling restaurants with temporary relief from food delivery fees,” CNBC Markets. May 15, 2020.

[13] https://anhd.org/press-release/usbnyc-elimination-commercial-lease-assistance-program-will-accelerate-displacement

[14] Lewis, Pamela. “Supporting microbusinesses in underserved communities during the COVID-19 recovery,” Brookings Institute. July 23, 2020.

[15] Edelen, Amy. ”New initiative aims to help small businesses with L.A. permitting burdens.” Los Angeles Times. August 16, 2016.

[16] Bierg, Alexander. ”San Francisco, notorious for business regulations, opens up one-stop permit shop.” California Economic Summit. February 21, 2013.

[17] Office of the Comptroller. ”The New Geography of Jobs,” April, 25, 2017.

[18] ibid

[19] Donahue, Ryan and Joseph Parilla. “Deploying industry advancement services to generate quality jobs,” Brookings Institute. July 23, 2020.

[20] Department of Labor. ”Occupations Licensed or Certified by New York State.” https://labor.ny.gov/stats/lstrain.shtm

[21] Boehm, Eric. ”Florida Just Passed the Most Sweeping Occupational Licensing Reform in History,” Reason. July 1, 2020.

[22] ”Manhattan Community Board One: Summary Report.” http://home2.nyc.gov/html/mancb1/downloads/pdf/Studies%20and%20Reports/Full%20Presentation_2016%20Accomplishments.pdf

[23] Office of the New York City Comptroller. ”New York by the Numbers Weekly Economic and Fiscal Outlook,” August 3, 2020.

[24] Regional Planning Association. “The Five Borough Bikeway,” June 2020.

[25] Mass Transit Magazine. ”ITALY: Italians who buy a new bicycle to get up to 500 euros from government,” May 12, 2020.

[26] Office of the New York City Comptroller. ”New York City’s Frontline Workers,” April 2020.

[27] United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates.