Executive Summary

The 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) marks one of the largest infusions of federal funding into the nation’s infrastructure of the last century. This legislation will invest $550 billion of new federal funding in transportation, clean energy, water quality, and broadband infrastructure across the country over a five-year period.[1]

New York City’s infrastructure repair and construction needs are extensive. Many of the city’s bridges, tunnels, and subway lines are over 100 years old.[2] IIJA presents an important opportunity to better support our local economy and long-term thriving, bringing with it the kinds of good jobs and strong infrastructure on which our local businesses, neighborhoods, and families depend. Better understanding how much money the City stands to receive and the projects it will fund is critical to ensuring New York City maximizes the potential benefits.

This report analyzes current and projected IIJA transportation spending in New York City. By tracing the flow of funding from the federal government to state and local levels, the report sheds light on how these federal funds are being spent in the five boroughs. The report’s recommendations aim to better align federal infrastructure funding with active transportation, climate, and safety goals to maximize the potential benefits of these much-needed resources.

Key Findings

- Federal IIJA funding meaningfully supplements local and state investments in New York’s transportation infrastructure. New York State and New York City are set to receive at least $36 billion and $1.58 billion, respectively, in funds dedicated to transportation uses. Both numbers reflect significant funding increases from FAST Act levels, the last federal surface transportation bill passed in 2015.

- Transit projects make up the largest share of IIJA spending in New York. 58%, or $21 billion of the $36 billion transportation funds that New York State is set to receive from the IIJA, is dedicated to transit. New York is the only state in the country to receive more federal funds for transit than roadways. Two large projects in New York City account for roughly half of State transit funds. The Federal Transit Administration awarded a $6.88 billion competitive grant to the Gateway Development Commission for the Hudson Tunnel Project, the single largest grant awarded to any entity out of the IIJA, or any federal program. The MTA also received a $3.4 billion competitive grant to extend the Second Avenue Subway to 125th Street in Harlem, $2.5 billion of which will come from IIJA funds. Both grants are for exceptionally large and vital transit projects with complex engineering needs that have been under development for many years.

- Most of the remaining 42% of statewide IIJA funding is dedicated to formula-funded highway projects. Of the $14.5 billion that New York State is set to receive for roads, bridges, and other roadway-related projects, 95% ($13.79 billion) is from the highway formula program and 5% ($703.8 million) is from competitive highway-related grants. Highway formula funding is also the largest source of funding awarded directly to the City of New York, making up 81% of the City’s IIJA funds. In addition to the highway formula funding directly allocated to the City, the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) will spend an additional $2.2 billion of highway formula funding on projects in the five boroughs.

- New York State is spending roughly half of its NYC-based highway formula funds on projects that expand highways, with little attention to emissions reduction or improving safety, in contradiction to both City- and State-level public policy. By contrast, the City has programmed its highway formula funds for projects with active transportation and sustainability goals. Of the highway formula funding that will be spent in the five boroughs, the State controls $2.2 billion and the City controls $1.28 billion. All of the highway formula-funded projects controlled by the City include active transportation, climate, or safety components. In contrast, over $1 billion of NYSDOT’s highway formula funding being spent in the five boroughs will either add new lanes to highways or widen existing ones. These State-led highway expansion projects undermine state and local climate and transportation safety objectives that aim to reduce car reliance and transportation emissions.

- While competitive grants offer the City opportunities to advance equity, mobility, and resiliency policy goals, they make up a smaller percentage of available IIJA funding. The IIJA expanded the number and dollar amount of competitive grant opportunities that are directly accessible to local governments. These grant programs tend to be more focused on the IIJA’s equity and climate policy goals. The City has responded to this opportunity by convening a task force to aggressively apply for competitive grants. As of July 2023, the City has successfully competed for and received $227 million in competitive transportation-related grants and may receive hundreds of millions more by 2026. However, competitive grant applications are very resource-intensive to develop, with no award guarantee. While the City continues its commendable effort to maximize federal grant opportunities, these findings underscore the need to simultaneously improve programming for the guaranteed sources of formula funds that make up the bread and butter of federal transportation programs.

- While California, Colorado, and Minnesota adopted performance standards to inform the design and selection process and ensure that infrastructure funding advances climate goals, reduces emissions, improves street safety, and prioritizes state of good repair, New York State has not done so. While it has unfortunately been typical for state transportation departments (DOTs) to use formula dollars for traditional highway-building projects, highway formula funding can and should be used more creatively to support projects that meet active transportation, sustainability, safety, and equity goals – as other states have demonstrated.

Summary of Recommendations

- New York State should establish performance standards for safety and sustainability to inform the selection and design of formula-funded transportation projects. Projects receiving federal funds should support state and local goals for improving street safety, advancing equity, and addressing climate change. New York should follow the lead of other states around the country and set clear performance standards to better prioritize projects that ensure these outcomes.

- Increase transparency in the City/State funding relationship. New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) is one of the largest beneficiaries of federal infrastructure spending in New York and will share a portion of state funds with local governments. To enable better planning practices and transparency, NYSDOT should provide clear guidance on the exact amount of funding it intends to spend in or pass onto the City to improve the City’s ability to budget and plan for capital improvements.

- Adopt overdue reforms to the City’s capital process through both State legislation and City implementation to accelerate delivery of infrastructure projects. The City’s successes in securing IIJA funding will only be realized if those funds are spent efficiently. Long delays, cost overruns, and outdated bureaucratic procedures often characterize large capital projects in New York City. Implementing the recommendations of the Capital Projects Reform Task Force and passing accompanying state legislation will enable faster and more cost-effective capital project delivery, to help the City better utilize the federal infrastructure funding it receives.

- Advance implementation of local and targeted hiring in New York City and State. The IIJA lifts federal prohibitions on the use of local hiring provisions for the funding programs that it authorizes. Leveraging this new authority in New York requires the passage of pending state level legislation, as well as continuing to build capacity within the City to support the implementation of local and targeted hiring programs.

- Improve IIJA capital project tracking and spending. The City and State do not currently track the federal funding in a public or easily accessibly manner. A centralized, comprehensive tool to track IIJA funding received and spent by both entities can enhance transparency as well as inform improvements to the project delivery process.

Introduction

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), became law in November 2021. From 2022 through 2026, this legislation will invest up to $1.2 trillion in transportation, clean water and energy, broadband, and resilience projects across the United States, $550 billion of which represents new funding above previously guaranteed federal spending levels. The legislation expanded many existing programs and established new programs, many of which provide funds to states and municipalities in the form of formula-based payments and competitive grants.

The IIJA provides an important opportunity to spur infrastructure projects that can modernize aging systems, support equitable and resilient investments, and improve quality of life for New Yorkers. Millions of people rely daily on the city’s outdated transportation, water, and energy infrastructure, much of which is in poor or deteriorated condition.[3] The various entities responsible for New York City’s infrastructure spend approximately $7 billion per year just to maintain existing transit, utility, and street infrastructure.[4] At the same time, managers of the city’s aging infrastructure must transform it to withstand new challenges, from resiliency improvements to address the increasing threats of climate change to electric vehicle charging networks to support the future of mobility.

Finding sufficient resources to address the scale of these infrastructure needs remains a challenge: the City identified over $14.1 billion worth of state of good repair costs across all agencies from 2024 to 2027.[5] This assessment is likely a significant underestimate of needs, given that the reporting excludes the cost of infrastructure expansion and replacement, assets valued under $10 million, and those leased to public benefit corporations. Maximizing the unique funding opportunity presented through the IIJA is critical to New York City’s efforts to bring existing systems into a state of good repair and modernize our infrastructure for the future.

New York State is set to receive at least $36 billion in federal funding from the infrastructure bill throughout the legislation’s five-year lifespan exclusively for transportation purposes. This funding is a combination of formula dollars distributed at the state level and discretionary grants going directly to municipalities and other eligible entities in New York. These funds will support a wide variety of projects, from upgrading airport infrastructure to making accessibility improvements on public transit. The total amount of funding the City of New York receives is contingent on state-level decisions about the allocation of formula dollars and the City’s ability to compete for discretionary grants at the national level.

This report provides the first comprehensive look at the federal infrastructure funding designated for New York City to date across the IIJA’s transportation programs. This analysis informs recommendations to maximize funding opportunities while improving climate, transportation, and equity outcomes. Given the prominent role played by New York State and other public agencies in distributing infrastructure funding and implementing projects within the City, this report also tracks the flow of funding from the federal government to state and local recipients and recommends strategies to prioritize projects in line with key policy goals.

IIJA Transportation Funding Overview

The IIJA distributes infrastructure funding and resources across several program areas administered through various federal agencies. Transportation makes up most of the funding available through IIJA: 62% is designated for roads, bridges, electric vehicles, airports, ports, rail, and transit programs (Chart 1), and 67% is being administered through the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) (Table 1). The primary mechanisms for dispersing the funds are through formula funds (45%) and competitive application-based grants (37%). (See Appendix for a more detailed breakdown of federal IIJA funding).

Chart 1: National IIJA Funding by Program Area

Source: White House Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Guidebook

Of the $566 billion in transportation funds IIJA provides, Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)-run highway programs account for the largest share (Table 1). FHWA programs for highways, roadway safety, bridges, electric vehicles, and ports and waterways will distribute approximately $338 billion nationwide through 2026, making up 60% of IIJA transportation funds. Federal Transit Administration (FTA) programs comprise the next largest amount of funding, with over $91 billion (16%) budgeted over five years. The Office of the Secretary of Transportation (OST) will manage over $30 billion (5%) worth of competitive grant programs that will fund projects of national significance aligned with the Administration’s policy goals. The remainder of the funding includes USDOT programs for railroads, airports, and maritime infrastructure that will together receive $106 billion.

Table 1: Transportation Funding in the IIJA

| Bureau | Funding (billions) | % IIJA Funds |

| Federal Highway Administration | $338 | 60% |

| Federal Transit Administration | $91 | 16% |

| Federal Railroad Administration | $66 | 12% |

| Office of the Secretary | $30 | 5% |

| Federal Aviation Administration | $25 | 4% |

| All Others* | $15 | 3% |

| TOTAL | $566 | 100% |

Source: White House Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Guidebook

Federal Equity Initiatives

Local and Targeted Hiring

The IIJA marks the first permanent authorization for recipients of federal infrastructure dollars, specifically funds distributed by the Federal Highway Administration (FWHA), to attach local and economically targeted hiring requirements to eligible projects.[6] Such policies require a certain percentage of jobs on a project be reserved for candidates living near the project area or meeting specific demographic criteria. Crafted and implemented thoughtfully, targeted hire policies can ensure that the financial benefits of construction and infrastructure projects reach the highest-need communities.

While the IIJA lifts the federal prohibition against targeted hiring practices, grants awarded under the legislation are still “subject to any applicable State and local laws, policies, and procedures.” State Senators Parker, Ramos, and Bailey introduced state bill A7677/S7387B to enable community hiring in New York, which passed in the 2023 legislative session.[7] If signed by Governor Hochul, the law would amend the New York City Charter, the Education Law, the General Municipal Law, the Labor Law, the Public Authorities Law, and the NYC Health and Hospitals Corporation Act to provide employment opportunities for economically disadvantaged candidates and candidates from economically disadvantaged regions.

In addition to legislative efforts to enable local and targeted hire, the City has also taken critical steps to establish the infrastructure needed to implement local and targeted hiring. In 2022, Mayor Eric Adams signed Executive Order 22 to consolidate the City’s workforce development and community hiring initiatives into a single office which will ultimately oversee implementation of local and targeted hiring efforts and address employment barriers for New Yorkers from economically disadvantaged communities to access jobs created by the IIJA and other major public works projects.

Justice40

The Biden Administration also created the Justice40 Initiative to ensure at least 40% of benefits from federal investments accrue to disadvantaged communities. The Justice40 directive encourages federal agencies to incorporate equity and environmental justice goals into notices of funding opportunities (NOFO) for grants, including new and existing programs created and funded through the IIJA, Inflation Reduction Act, and American Rescue Plan. The pilot program includes 21 federal programs that have developed roadmaps for expedited implementation of Justice40 initiatives.[8]

How Federal Transportation Funding is Being Spent in New York

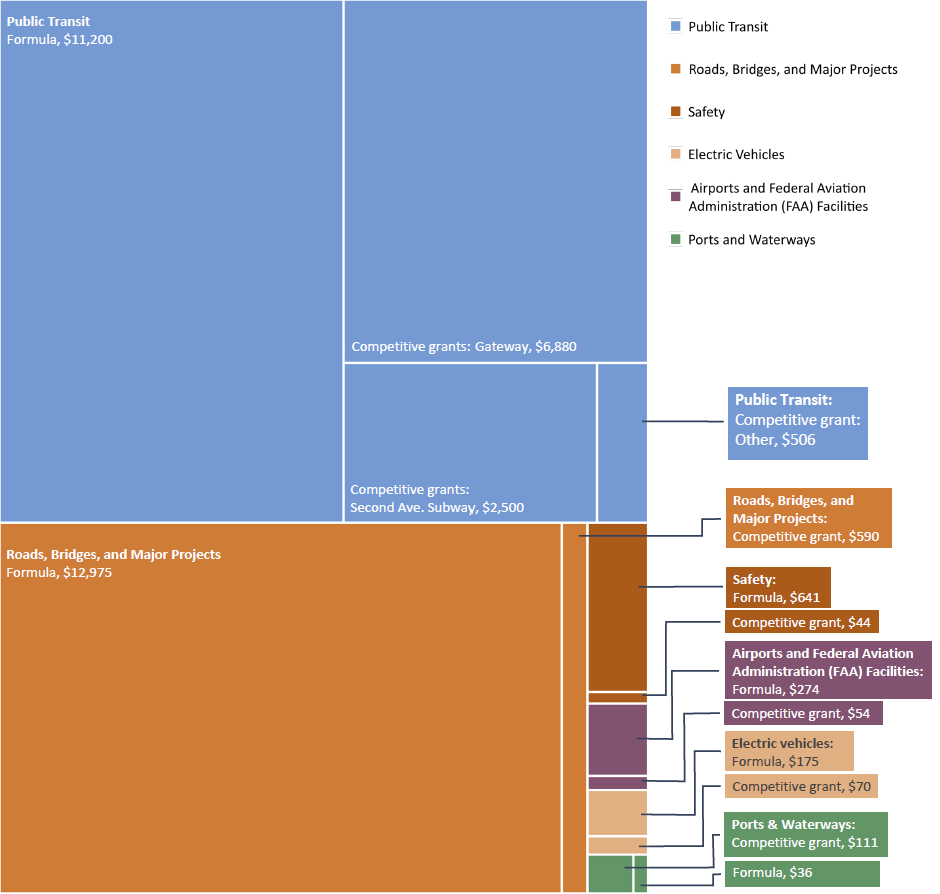

Of the $36 billion in federal transportation funding going to New York State, an estimated $23.3 billion (65%) will be spent in the five boroughs (Table 2).[9] Federal funds flow to state and local governments through multiple programs to different public agencies responsible for maintaining and building infrastructure. As Chart 2 illustrates, most of the federal funding designated for New York will come via formula funding to NYSDOT for highway projects and the MTA for transit projects. NYSDOT can share formula block grant funding with municipalities in its jurisdiction or opt to spend federal funds on its own assets. The City of New York will receive most of its federal funding through formula block grant funding allocated by the State, and a smaller portion from directly applying to competitive grants administered by the federal government.

Chart 2: New York State IIJA Funding (Millions) by Program Area and Award Type

Sources: FHWA FY 2022 – FY 2026 State-by-State Apportionments, APTA IIJA Public Transit State-by-State Formula Apportionment Table, White House Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Guidebook, New York State Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), New York Metropolitan Transportation Council (NYMTC) Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP), Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) Maps Dashboard, NYS Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), and New York City Mayor’s Office of Operations

Table 2: State and Local Flows of IIJA Funding by Program Area (millions)

| Program Area/Category | Statewide Formula (billions) | Statewide Competitive Grants (billions) | Statewide Total (billions) | Total Spent in NYC (billions)[1] | Awarded to City (billions) |

| Highway Programs (Roads, Bridges, Safety, Electric Vehicles) | $13,791 | $704 | $14,495 | $4,058[2] | $1,488[3] |

| Roads, Bridges, and Major Projects | $12,975 | $590.4 | $13,565 | $4,081 | $1,383 |

| Safety | $641 | $44.2 | $685 | $139 | $87 |

| Electric Vehicles | $175 | $69.6 | $245 | $18 | $18 |

| Public Transit | $11,200 | $9,886 | $21,086 | $18,795 | $66 |

| Airports and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Facilities | $273.6 | $53.8 | $327 | $198 | $0 |

| Ports and Waterways | $35.6 | $111 | $146.6 | $60 | $30 |

| Total | $25,300 | $10,755 | $36,055 | $23,291 | $1,584 |

Sources: FHWA FY 2022 – FY 2026 State-by-State Apportionments, APTA IIJA Public Transit State-by-State Formula Apportionment Table, White House Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Guidebook, New York State Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), New York Metropolitan Transportation Council (NYMTC) Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP), Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) Maps Dashboard, NYS Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), and New York City Mayor’s Office of Operations

Chart 3: IIJA Funding Awarded to the City of New York

* The Competitive Grants represent only the amounts received through June 2023, whereas the formula funding is for the entire five-year term of the IIJA. Assuming that the City maintains a consistent annual rate of successful competitive grant awards, the City could see an additional $500 million of competitive grant funding that would bring the proportion of competitive grants up to 35% of total infrastructure funding for NYC.

Sources: White House Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Guidebook, New York State Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), New York Metropolitan Transportation Council (NYMTC) Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP), Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) Maps Dashboard, NYS Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), and New York City Mayor’s Office of Operations

Formula Funding

USDOT distributes large pots of funding for highway and transit uses in New York State via formula programs, which calculate state allocations based on factors including population, highway mileage, and transit ridership. Additional USDOT-administered formula programs will provide funds to support New York City’s ferries and airports. These programs also received funding increases through the infrastructure bill but make up a smaller share of the total amount of transportation funding spent in the city.

Overall, the largest category of New York’s federal transportation funds comes from formula programs: highway and transit formula funds comprise 69% of IIJA transportation funds controlled by the State (Table 2). The highway formula program is the bread and butter of IIJA funding, estimated to make up 64% of the City’s federal transportation funds through 2026 (Chart 3).

Table 3: Transportation Formula Funding in New York

| Program Area/Category | Statewide (billions) | Awarded to City of New York (billions) |

| Highway Formula | $13,791 | $1,281[4] |

| Transit Formula | $11,200 | $51 |

| All Others[5] | $309 | $25 |

| Total | $25,300 | $1,357 |

Sources: FHWA FY 2022 – FY 2026 State-by-State Apportionments, White House Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Guidebook, New York State Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), New York Metropolitan Transportation Council (NYMTC) Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP), and NYS Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA)

Transit Formula Funding

Transit agencies are major recipients of federal formula funding. Nationally, transit formula programs will receive approximately $69 billion through 2026.[10] During the five-year IIJA period, transit agencies across New York State will collectively receive an estimated $11.2 billion in formula funds to spend on capital improvements to their systems.[11] MTA will receive $10.6 billion of this total, out of which approximately $8.9 billion will fund New York City-based projects.[12] New York State receives much more transit formula funding than anywhere else in the country – a function of the exceptionally high number of transit riders in New York City. In 2022, over three times as many people rode the New York City subway as the nine next largest rapid transit systems in the country combined.[13]

Highway Formula Funding

Highway formula programs nationally represent the largest source of guaranteed funding that states will receive from the infrastructure bill. The IIJA reauthorized the surface transportation program, which doubled the amount of funding for USDOT programs from the 2015 FAST Act, the last federal surface transportation legislation passed in 2015. Nationally, $259 billion of the $566 billion available in IIJA transportation funding (46%) goes towards pre-existing federal aid highway programs, most of which state transportation departments will receive in the form of formula-based block grants.[14] The National Highway Performance Program (NHPP) alone is funded at $148 billion – over twice the size of the next largest IIJA-funded program.[15]

The term “highway formula program” is a bit of a misnomer, as highway funding can be used toward a range of projects from highway maintenance and expansion to street safety and active transportation roadway improvements. Traditionally, however, state transportation departments have used these funds to pay for projects on state-owned roads and the National Highway System. In total, highway formula programs administered by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) will distribute approximately $273 billion of formula funding to states through 2026 and account for approximately 48% of the transportation funding provided through the IIJA (Table 1).[16]

State DOTs have broad discretion over how highway formula resources will be allocated to municipalities. Specific pots of formula funds may focus on certain criteria. For instance, the Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) formula program focuses on safety while the Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) formula program focuses on reducing air pollution derived from vehicles. Recipients of those formula programs must report on relevant metrics for safety, maintenance, and highway reliability as dictated by each program, but federal law does not dictate or require specific performance outcomes. As a result, federal formula dollars tend to be used for traditional roadbuilding and maintenance projects while competitive grants tend to support more multimodal, sustainability-oriented projects.

Of all the highway formula funding spent in the five boroughs, NYSDOT controls $2.2 billion and the City controls $1.28 billion (Table 2).[17] All of the City-controlled highway formula funding is planned for projects that include active transportation, sustainability, or safety components. In contrast, $1.07 billion of the $2.2 billion NYSDOT-controlled highway formula funding spent in the five boroughs will either add new highway lanes to highways or widen existing ones. It is both important and legally required that NYSDOT maintain a state of good repair on highway systems. The State does use highway formula funding to address the design, construction, maintenance, and operations of National Highway System assets and state-owned roadways, although it delegates some of its highway maintenance responsibilities to the City, which receives payment for performing those services. Beyond that baseline obligation to maintain the existing roadway, however, NYSDOT has elected to spend a significant amount of its highway formula funding on expanding highways, with 24 projects across the state that expand highway networks in what one observer has called a “highway expansion binge.”[18]

The largest of the highway expansion projects is a $1.3 billion project to widen the Van Wyck Expressway from three to four lanes in both directions ($730 million of the total Van Wyck project budget is IIJA-funded). In addition to those already-obligated highway expansion projects, NYSDOT also lists two additional projects that would involve extending, widening, or studying the expansion of highways in New York City as “currently under development.”[19] NYSDOT anticipates using federal funding to ultimately implement those two projects, which are estimated to cost a combined total of $165 million.[20]

NYSDOT’s use of highway formula funding for highway projects is unfortunately consistent with the traditional practice of many state DOTs across the country. Such car-oriented projects result in increased emissions and reliance on single-occupancy vehicles[21]—outcomes antithetical to State[22] and City[23] policy goals. While NYSDOT has programed the other half of its formula funding for important projects that address flood mitigation, intelligent transportation system operations, and ongoing highway maintenance, New York lacks statewide, holistic, performance-driven criteria to program highway formula dollars. It is especially troubling that half of NYSDOT’s highway formula funding spent in New York City—the U.S. city with the largest public transit network and lowest rates of car ownership—is being spent on highway expansion. State-level decision makers can and should consider guardrails for how to strategically leverage future highway formula funding to maximize the potential climate, safety, and accessibility benefits of the IIJA.

Competitive Grants

The IIJA significantly expands the number and total dollar amount of grants for which municipalities can compete. USDOT is responsible for administering over $186 billion in IIJA-funded competitive grants, more than any other federal agency.[24] While formula funds are rigidly required to be dispersed to designated entities, such as state DOTs and transit operators, competitive grants have a much wider range of eligible direct recipients including local governments, public agencies, tribal governments, nonprofits, and research institutions. Unlike formula funding amounts, which are set for the IIJA’s five-year term, the City and State can continuously apply for competitive grant opportunities through 2026.

The IIJA’s competitive grant programs are more directly tied to the bill’s equity and sustainability-oriented goals, particularly for the surface transportation program. Dozens of competitive transportation grant programs will distribute billions for street safety, transit expansion, electric vehicle infrastructure, port, airport, and rail projects across the country. Three of the largest transportation discretionary grant programs under IIJA—RAISE, INFRA, and Mega—require that all projects meet defined criteria related to climate, safety, and equity to receive funding. In contrast, most highway formula programs permit spending in support of these outcomes but do not require or encourage it.

The expansion in competitive grant opportunities open to cities is an important feature of the IIJA and represents a major development in the federal infrastructure funding landscape. Federal grant programs offer opportunities for the City to directly receive funds for priority projects without NYSDOT involvement. Grants can support transformative, large-scale projects and encourage recipients to develop ambitious plans that may not be achievable without federal support.

Entities throughout New York State have received an estimated total of $10.75 billion in competitive grant funds to date (Table 2), including the two largest IIJA-funded projects, which are both based in New York City. In July 2023, the Gateway Development Commission (GDC) received a $6.88 billion grant for the Hudson Tunnel project, to construct a new tunnel connecting Manhattan to New Jersey and rehabilitate existing ones.[6] This funding is in addition to a prior $292 million MEGA grant awarded to Amtrak for repairs on an earlier phase of the same project. The Hudson Tunnel project is one part of the multibillion-dollar Gateway Program to improve rail connections between Newark and New York City and represents the largest grant awarded to any entity in the country. The Gateway and Second Avenue Subway projects are both funded through the Capital Investment Grant (CIG) program, an FTA-administered competitive grant program that supports large transit expansion projects. These projects make clear that federal funds are critical to advancing projects of this scale and complexity.

The City of New York has also aggressively applied to IIJA’s expanded competitive grant opportunities. As of mid-2023, the City has applied for $1.2 billion worth of competitive grant funds,[25] and successfully received 11 transportation-focused competitive grants valued at a total of $226.8 million (Table 4), with several more grant applications under review. These grants will go toward modernizing the Hunts Point Terminal Produce Market, planning for greenway expansion, implementing a road diet on Delancey Street, and purchasing electric school buses.

Upon the passage of the IIJA, the Deputy Mayor for Operations began convening a task force of the City’s capital agencies to identify promising funding opportunities, provide technical grantwriting assistance, coordinate project scoping, and foster interagency collaboration. This task force has not only helped the City keep track of the sheer number of competitive grant programs and deadlines, but also supported agencies to workshop grant applications and solicit interagency feedback to strengthen scopes of work. The task force has been especially helpful for crafting complex cross-jurisdictional grant applications that can achieve multiple benefits and break down traditional agency grantwriting silos. For instance, the City’s $110 million INFRA grant for Hunts Point (the largest successful City competitive grant application) is a joint initiative between the New York City Economic Development Corporation, NYCDOT, and the Department of Small Business Services. The project includes a new intermodal freight terminal and state-of-the-art sustainable building that will reduce the carbon footprint and strengthen small businesses that are vital to the regional food economy.

Although the City can compete for billions in competitive grant funds at levels that in theory could exceed the amount that the City expects to receive from NYSDOT via formula funds, to date, competitive grants make up just 14% of the City’s total IIJA funding (Table 3) and 30% of the State’s total IIJA funding (Table 2). If the City maintains a consistent annual rate of successful competitive grant awards, the City could see an additional $500 million of competitive grant funding that would bring the proportion of competitive grants up to 35% of total infrastructure funding for NYC. However, the amount of competitive grant funding is unlikely to exceed the amount of formula funding spent within city borders. While the City should continue to leverage its working group to prepare strong grant applications that advance critical initiatives as new competitive programs are announced, it is important to acknowledge that competitive grant applications are extremely resource-intensive to develop and there is no guarantee of funding in the end. This underscores the need to better program the guaranteed sources of statewide highway formula program that make up the bread and butter of federally funded transportation projects.

Table 4: City of New York IIJA Competitive Grants Selected for Award[7]

| Lead Agency(s) | Project/Program | FFY | Grant Program | Grant Amount (millions) |

| NYCEDC / NYCDOT / SBS | Hunts Point Terminal Produce Market Intermodal Facility: Supports the redevelopment of Hunts Point Market to strengthen freight movement while improving local sustainability and quality-of-life outcomes. | 2022 | INFRA (USDOT) | $110 |

| NYCDOE | Electric School Buses: Funds three NYC school districts to purchase 51 new clean school buses. | 2022 | Clean Bus Program (EPA) | $18.3 |

| NYCDOT | Multimodal Access to Transit: Implements pedestrian safety improvements for bus riders along 86th Street in Brooklyn. | 2022 | Bus and Bus Facilities (USDOT) | $9 |

| NYCDOT | Greenway Expansion Study: Funds a concept study to expand the City’s greenway network across the five boroughs. | 2022 | RAISE (USDOT) | $7.25 |

| NYCEDC | Upgrades/Activation of 6 NYC Harbor Sites/Landings for Maritime Freight | 2022 | MARAD (USDOT) | $5.16 |

| CUNY | SEMPACT CUNY Transportation Research Proposal | 2022 | University Transportation Centers Program (USDOT) | $3 |

| NYCDOT | East River Bridges Planning and Development: Funds the planning and development of a 30-year capital construction program for the Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Ed Koch Queensboro bridges | 2022 | Bridge Improvement Program (USDOT) | $1.6 |

| NYCHA | Safe Access for Electric Micromobility | 2023 | RAISE (USDOT) | $25 |

| NYCDOT | Delancey Street Road Diet: Redesigns dangerous features on Delancey street by narrowing lanes, widening sidewalks, and building fully protected bike lanes to improve safety outcomes. | 2023 | SS4A (USDOT) | $21.5 |

| NYCDOT | Safe Routes to Transit: Jerome Avenue Bus Facility Improvements | 2023 | Bus and Bus Facilities (USDOT) | $6 |

| NYCEDC | Broadway Junction Pedestrian Plan | 2023 | RAISE (USDOT) | $20 |

Source: New York City Mayor’s Office of Operations

Programming Highway Dollars: A Comparative Case Study of Formula and Competitive Grant Funded Projects

A comparison of the State-led project to widen the Van Wyck Expressway and the City-led project to create a comprehensive greenway expansion plan offers an illustrative example of the divergent uses of federal transportation dollars that shape project planning processes and outcomes. While both projects receive federal infrastructure funds, the State-led Van Wyck Expressway project is funded by formula highway funds and implements a traditional highway expansion project, while the City-led NYC Greenway Expansion project, funded through a competitive grant, will support the planning process to fill gaps in the City’s multimodal greenway network. To be clear, this is not an argument that all projects funded with IIJA funds should be greenways. Still, comparing these two case studies demonstrates the need for better statewide guardrails for how to prioritize federal funding to advance active transportation, safety, sustainability, and equity goals.

Overview of the Projects

Van Wyck Expressway Widening: NYSDOT is overseeing a $1.3 billion widening of the Van Wyck Expressway, the largest state-administered IIJA-funded project in New York City. This project is intended to increase capacity on a 4.3-mile section of the expressway by adding a fourth lane in both directions and retrofitting bridges and ramps along the route. The project area runs from Hoover Avenue at its northernmost point to the airport entrance at Federal Circle, adjacent to several southeast Queens neighborhoods. Initial construction began in late 2020 and is projected to be completed in 2025.

Filling the Gaps: NYC Greenway Expansion: The City successfully secured a $7.25 million competitive USDOT RAISE planning grant (an IIJA-funded program) to create a series of visioning and action plans intended to build out New York City’s greenway network and enable new multimodal connections. The goals of this project are to improve pedestrian and cyclist safety, create new transportation options and encourage mode shift. The total project budget is $9.06 million, with $7.25 million coming from RAISE and local City capital funds paying for the remainder.[26]

Funding Sources

The Van Wyck Expressway Widening project is funded through two highway formula funding programs, totaling $730 million, with the remainder of the project budget coming from the State. The two federal highway formula sources include $510 million from the National Highway Performance Program (NHPP) dedicated to highway maintenance and operations and $211 million from the Surface Transportation Block Grant Program’s (STBGP) set-aside for large, urbanized areas.[27] Neither program explicitly requires or encourages State entities to propose projects in alignment with any active transportation, climate, or safety goals, but those objectives are allowable. Funds from the NHPP and STBG programs are fungible, in that up to 50% of funds from one can be transferred to other programs, allowing the funding to address a wide range of policy goals. NYSDOT has defined its own goals for the Van Wyck project to more narrowly focus on reducing vehicle travel time, improving “operations and geometry of ramps” (namely, widening the roadway), and addressing structural deficiencies of the asset.[28]

The NYC Greenway Expansion project, on the other hand, was funded through RAISE, a competitive grant program designed for “Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity.” The RAISE application offered an opportunity for the City to propose a project that meets both federal and local policy goals through the expansion of the City’s citywide protected bike lane infrastructure with a focus on expanding the bike network in underserved communities where there are major greenway gaps. The RAISE program is designed for awardees to “to obtain funding for multi-modal, multi-jurisdictional projects that are more difficult to support through traditional DOT programs.”[29] RAISE not only explicitly calls for projects that achieve sustainability and equity performance objectives, it also prompts grant applicants to think outside of the box to scope competitive multimodal projects. The highway formula programs that fund the Van Wyck project, by contrast, do not proscribe such narrow performance-based objectives.

Decision-Making

NYSDOT is the lead agency and sole decision-maker for the Van Wyck Expressway project. NYSDOT held two public hearings as part of the EIS process, after the preliminary designs for the project were already completed. These hearings were sparsely attended, and NYSDOT only reported collecting a total of two comment cards and three oral testimonies between the two events.[30] The City has a modest role to play in reviewing design drawings developed by NYSDOT for the new widened highway, but the City is not a decision-making authority for the project.

In comparison, the NYC Greenway Expansion project is a partnership between NYCDOT, NYC Department of Parks and Recreation, and NYC Economic Development Corporation, exemplifying the intent to integrate various transportation, recreational, land use, and economic development objectives. These three lead agencies will jointly develop a comprehensive citywide greenway vision plan and identify five “early action” communities outside of Manhattan to prioritize implementation, potentially extending greenways along Brooklyn’s Eastern Parkway, Jamaica Bay, the Harlem River in the Bronx, and Staten Island’s North Shore. This effort fulfills the mandate of City Council legislation passed in October 2022, which requires the City to complete a master plan by December 2024, following a public engagement process involving communities adjacent to proposed greenways.[31]

Planning and Construction Funds

One notable distinction between these two projects is that the State’s funding for the Van Wyck project is for construction and City’s funding for the NYC Greenway Expansion is exclusively for planning. Planning and construction are both important phases of the capital process: transformative infrastructure redesign must be informed by a thoughtful planning process, and thoughtful planning should be followed by a clear pathway for construction.

These two projects highlight tensions on either end of the spectrum. When construction projects move forward without robust public engagement, projects may not be responsive to community needs. The emphasis on project shovel-readiness often pushes agencies to speed toward construction timelines. NYSDOT’s limited public engagement efforts are reflected in the project’s intended outcomes that go against many equity and climate goals.

Conversely, when extensive planning processes lack funding commitments or clear timelines for construction, it can erode public trust with people who spent time and effort to share their feedback and result in planning fatigue. Although the City must conduct thorough community engagement to create a greenway master plan, filling all the gaps in the current greenway network could require over $1 billion[32]—money that the City does not currently have in-hand. While the current planning process may position the City competitively for a shovel-ready project in the future, the fate of implementation remains highly uncertain. Only a small number of federal programs offer dedicated funding at the level needed to fully implement complex, multimodal projects.

Policy Alignment

NYSDOT’s Van Wyck Expressway Widening project is quite simply at odds with many of the City’s—and the State’s own—policy goals for reducing transportation emissions and improving congestion. While widening the Van Wyck is meant to reduce travel times to JFK Airport, the project raises climate and environmental quality concerns.

Although the project’s environmental impact statement (EIS) cites an anticipated 8-15 minutes of driving time-savings as the justification for the expansion, long-term evaluations of similar highway widening projects suggest that time-saving effects are temporary at best due to the increase in driving that follows the construction of new highway space.[33] Studies of this phenomenon, known as induced demand, show that adding lanes to highways does not result in meaningful reductions in traffic congestion and travel times return to pre-construction levels within an average of five to eight years.[34] The Van Wyck’s own history previewed similar short-sightedness. Robert Moses famously declined to include space for a transit option when building the expressway, when it would have cost little, rendering transit infeasibly expensive.[35] Initially intended to relieve traffic congestion in Queens when it first opened in 1950, the expressway quickly generated new traffic that overflowed onto local streets.[36] The State’s study for the current expansion explored a no-build scenario as an alternative but did not comprehensively evaluate climate-friendly strategies to improve access to JFK Airport, such as improving transit access or reducing Air Train fares.

The EIS acknowledges the increase in air pollutants as a result of adding more lanes but does not identify any potential increase in greenhouse gas emissions as more drivers use the expressway. Additional traffic on the corridor translates to higher greenhouse gas emissions and particulate matter, with most of the resulting health and environmental burdens falling on surrounding neighborhoods. 85% of residents in communities surrounding the Expressway, including Kew Gardens, Richmond Hill, and Jamaica, are people of color and 30% do not own a car.[37] The City of New York has already designated these neighborhoods as environmental justice communities since 2017.[38] Widening the Van Wyck may bring temporary benefits for drivers, but the project’s impacts to climate and public health will be long-lasting.

In contrast, the City’s Greenway Expansion aims to deliver public health, quality of life, and sustainability outcomes for residents of neighborhoods surrounding the planned network. The $7.25 million the City received from USDOT will be used for planning efforts to determine options for filling gaps in the existing greenway network, creating connections to transit, and improving connectivity between communities. Multiple areas named as potential sites for greenway expansion, including Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn and the North Shore of Staten Island, are designated as environmental justice communities by the City, in need of pollution and carbon mitigating investments. Beyond enhanced mobility impacts, greenways generate sustainability and public health benefits, in the form of mitigating the urban heat island effect, reducing stormwater runoff, and reducing reliance on automobiles. The project is also aligned with both the New York City Streets Plan as well as the Roadmap to 80×50, the City’s climate change and emission reduction plan.

Recommendations

The following recommendations will improve efforts to secure and deploy federal funding for transportation and infrastructure projects that support a safer, more sustainable, and more equitable city.

1. New York State should establish performance standards to inform the selection and design of formula-funded transportation projects.

While current highway formula dollars are programmed for the current five-year IIJA term, the highway formula program is a mainstay of federal infrastructure funding. As such, it is important to equip New York State to use future highway dollars more effectively to advance policy goals. While federal formula programs do not require projects to meet holistic performance criteria, states are allowed to enact stronger and more comprehensive performance standards governing the use of transportation funds in alignment with safety, equity, emissions reduction, and resiliency goals.

The Federal Highway Administration considered strengthening formula funding performance goals. In 2021, FHWA issued a first-of-its-kind six-page memo recommending state transportation departments to take a new approach when using formula funding.[39] The memo included guidance to:

- Prioritize street safety and safety-oriented projects over highway expansion.

- Prioritize roadway repair and maintenance over new construction.

- Eliminate onerous environmental reviews of active transportation projects.

- Invest in local streets where the majority of trips occur over less-used state-owned highways.

- Account for induced demand and greenhouse gas emissions in travel demand models.

Despite the advisory nature of the memo, and FHWA’s lack of legal authority to enforce the guidance that the memo put forward, the memo received immediate backlash from Republican legislators. Senators Mitch McConnell and Shelley Moore Capito issued a letter advising governors to ignore FHWA’s recommendations.[40] Following the 2022 midterm elections, new committee leaders in the House and Senate pledged to formally challenge the memo by triggering a resolution of disapproval under the Congressional Review Act. In response, FHWA leadership opted to retract the memo in February 2023 and formally defer to states on the use of highway formula funding.[41]

In the absence of federal rules or laws to guide the spending of formula dollars, several states have adopted stronger performance standards to ensure that formula-funded transportation projects advance street safety and climate goals.

In 2022, Colorado adopted a rule requiring that new transportation infrastructure investments achieve significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. The state’s transportation department and metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) must now estimate emissions associated with future projects, including from induced demand, and propose mitigation strategies if projections exceed a fixed level.[42] The rule stipulates that mitigation strategies must prioritize transit and active transportation solutions rather than vehicle electrification alone. The State of California finalized a similar rule in 2020, requiring transportation agencies to evaluate projects based on their ability to reduce overall amounts of driving (vehicle miles traveled, or VMT) rather than their impact on traffic congestion.[43] More recently, Minnesota passed a law during the 2023 legislative session requiring the Minnesota Department of Transportation to align highway projects with the state’s emissions and VMT reduction goals.[44]

New York State should follow suit to develop statewide performance criteria that set a comprehensive framework for the selection and prioritization of highway formula funded projects in alignment with state and local policy goals, including but not limited to:

- reducing transportation emissions;

- ensuring maintenance of existing roadways (i.e. state of good repair);

- incorporating pedestrian, transit, and cyclist-friendly multimodal features;

- increasing Vision Zero and safety;

- strengthening the resilience of our transportation infrastructure to meet future climate conditions;

- improving accessibility outcomes;

- investing equitably in underserved communities.

Establishing stronger, performance-based formula policies directing the use of transportation funding at the state level can ensure that federal dollars are being spent in a manner that advances state and local key policy goals. Such a policy could be established by State law, Executive Order, or NYSDOT rule.

2. Increase transparency in the City/State funding relationship

NYSDOT is the single largest beneficiary of IIJA funding in New York and will receive an estimated $13.7 billion through 2026 from highway formula programs alone. IIJA gives NYSDOT broad discretion over how much money to share with local governments. Traditionally, the amount of funding passed onto city entities is the result of negotiations between the State and City. Between 2022 and 2026, $2.2 billion of the $3.7 billion (65%) in NYSDOT funds set to be spent in New York City is reserved for state-administered projects leaving just above $1.2 billion for City use (32%). On an annual basis, this represents a 52% increase from the City’s previous allocation of $157 million per year.[45] The remaining portion of highway formula funds will go the MTA and other, smaller managers of infrastructure in the city.

To eliminate uncertainty and improve transparency around federal funding, NYSDOT should provide timely guidance on how it intends to share formula funds with local governments. This will allow the City to better prepare for future projects, account for federal funding in its capital budget, and enable a more equitable funding split between the City and State.

3. Adopt overdue reforms to the City’s capital project delivery process through both State legislation and City implementation to accelerate delivery of infrastructure projects.

Efforts to maximize federal funding must be accompanied by actions to spend that funding efficiently. Construction costs in New York City are among the highest in the world,[46] necessitating measures to eliminate delays and potential cost overruns on major projects. While the City has begun implementing the recommendations from its 2022 Capital Process Reform Task Force to streamline capital project approvals and improve interagency coordination, much work remains.[47]

The Task Force proposed a nine-part State legislative package to substantially accelerate timelines and reduce the cost of capital projects in New York City, like those funded by IIJA. In the 2023 session, the State Legislature adopted bills to permit the City to utilize electronic bidding, allow wrap-up insurance, and expand M/WBE utilization. Those bills await the Governor’s signature.

However, the Legislature did not take up proposals to give the City authority to use progressive design-build and other alternative delivery methods, or to allow online public comment hearing formats rather than requiring in-person hearings. In-person hearings almost always have poor attendance, yet add several weeks to project timelines. State-level elected officials should consider the remaining legislation for adoption during the 2024 legislative session.

At the same time, the City must move expeditiously to implement the Task Force recommendations that do not require State legislation. These actions include strategies to improve the project pipeline, reform procurement, streamline internal City approvals, grow the number of New Yorkers who can participate in capital planning, manage projects more effectively, and adopt performance management and public reporting.

4. Advance implementation local and targeted hiring at the state and city levels.

For the first time, the IIJA allows cities and states to attach targeted hiring requirements to infrastructure projects funded with federal dollars. Instituting a targeted hiring requirement for federally funded projects can support the City and State’s economic development goals, ensuring crucial infrastructure dollars are recirculated within the local economy. However, fulfilling the full potential of this provision of the IIJA will require state and local action.

During the 2023 legislative session, the Legislature passed A7677/S7387B to amend applicable state and city laws to allow targeted hiring for economically disadvantaged candidates and candidates from economically disadvantaged regions on state-funded infrastructure projects. It is critical that Governor Hochul signs state bill A7677/S7387B expeditiously to allow New York City to take advantage of the hiring permissions in the IIJA and ensure more New Yorkers have access to these jobs.

In addition to passing the state legislation, both the City and the State must establish and strengthen procedures to implement local and targeted hiring on IIJA projects. The State has not yet publicly announced plans for local or targeted hiring on its IIJA projects, but the City has launched initiatives to advance local and targeted hiring.

New York City’s Executive Order 22 was a vital step towards establishing the Mayor’s Office of Workforce Development and Community Hiring. That order consolidates the City’s workforce development and community hiring initiatives into a single office to oversee implementation efforts and address employment barriers for New Yorkers from economically disadvantaged communities to access jobs created by the IIJA and other major public works projects. Once A7677/S7387B is signed into law, the City can begin implementing targeted hiring on IIJA projects.

As an immediate next step, the City could consider procuring software that enables front-end tracking of local and targeted hiring efforts, prevailing wage compliance, and other labor standards. Unlike many other jurisdictions around the country, the City does not currently have a system in place to proactively compile this key workforce information and typically only investigates compliance following a complaint. Proactively adopting this technology will set a strong foundation for the City to implement a citywide community hiring program.

Since the vast majority of IIJA funding spent in New York City will be spent by state agencies, especially NYSDOT and the MTA, the City should implement local and targeted hiring and workforce development initiatives in order to take advantage of this opportunity, which will allow New Yorkers to share in the economic benefits that local projects bring.

5. Improve IIJA tracking and spending

Currently, no centralized tracking mechanism exists to identify how IIJA funding is spent in New York City, or statewide. The data underlying this analysis came from several sources, including the statewide transportation improvement program (STIP), the White House’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding tracker, press releases, the City’s competitive grant tracking efforts, MTA’s internal grant accounting, and federal program announcements. The data from these sources were often inconsistent and incomplete, and these sources are all updated on different schedules.

The City and State should develop a way to transparently and effectively track IIJA funding. Such a tracker should identify the amount and source of federal funds, project status, schedule, location, and spend-down rate of all federally funded projects. Such a tracker should also include applications submitted to competitive grant programs, and whether those grants were successfully awarded. Project location data will also enable the City to understand its ability to meet Justice40 goals for equitable distribution of federal resources. Because competitive grant spending is handled on a reimbursement basis, an IIJA grant tracker would also be useful to ensure that the federal government is reimbursing the City for the full amount of funding awarded. The inclusion of project schedules could also help identify sources of delay specific to federally-funded initiatives.

It is especially important to be able to effectively track IIJA funding because the City’s ability to achieve the sustainability agenda set forth in PlaNYC heavily relies on the City’s ability to secure federal funding. Nearly all PlaNYC commitments hinge on the availability of federal funding for implementation. Major initiatives contingent on federal funding in PlaNYC include the Seaport Coastal Resilience project, the Climate Strong Communities program, a backwater valve program, the Cloudburst initiative for stormwater management, a new voluntary land acquisition and housing mobility program, ten resilience hubs by 2030, and public access improvements along waterways.[48] IIJA grant tracking will ensure public transparency and accountability for these critical initiatives.

City IIJA grant tracking need not be a separate platform, and could be integrated into the City’s Capital Projects Tracker. As the result of Local Law 37 of 2020, sponsored by then Council Member Brad Lander, the City is currently working to expand its citywide Capital Projects Tracker to include all projects in the City’s capital budget (not just those over $25 million) and add additional project details. Further improvements to the tracker should also include more visibility into the specific sources of federal funding and project locations.

Conclusion

The IIJA represents a much-needed infusion of federal funding into modernizing our infrastructure. The projects receiving federal funds, such as the Second Avenue Subway Phase 2 extension, the Hunts Point Terminal Produce Market redevelopment, and the Van Wyck Expressway widening, will have immediate and long-term impacts on City infrastructure that New Yorkers use daily.

Federal funding can be a critical resource to upgrade our roadway and transit systems to prioritize safety, accessibility, sustainability, equity, and quality of life outcomes—but only if the criteria for selecting and prioritizing projects align with those objectives. State-level decision makers can and should develop strong performance-based evaluation criteria to ensure that our federal dollars fund projects that advance our policy goals, following the lead of other forward-looking state DOTs. A centralized project tracking system should provide transparent and up-to-date information on the status, funding sources, and implementation timeline for all federally funded projects to ensure that our federal spending is timely and equitable. Lastly, the State and City must continue to advance efforts to reform capital project delivery and advance local and targeted hiring so that we can make the most of the federal funds we receive to improve our infrastructure, present and future.

Methodology

This report relied on multiple local, regional, state, and federal sources to track IIJA spending in New York City.

To identify competitive grants awarded to projects based in New York City, the Comptroller’s Office cross-referenced data from the White House’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) Maps Dashboard alongside City and MTA records of their grant awards.

Analysis of federal formula funding and spending by both NYSDOT, MTA, and NYCDOT drew from NYSDOT’s Statewide Transportation Improvement Programs (STIP) and New York Metropolitan Transportation Council’s (NYMTC) Transportation Improvement Plans (TIP) for the years covered by the IIJA (2022 through 2026). USDOT funding tables for FHWA and American Public Transit Association (APTA) tables for FTA formula programs informed the total amount of formula funding NYSDOT and MTA expect to receive through 2026. MTA also provided estimates of transit formula spending in New York City. The City provided public estimates of the level of suballocated funds available to the New York City. The data in this report drawn from these sources is current as of June 30, 2023.

Comptroller’s Office staff conducted informational interviews with multiple agencies responsible for administering or monitoring federally funded projects and grants, including NYSDOT, NYMTC, NYCDOT, NYCEDC, the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Operations, as well as the Regional Plan Association.

Finally, information on national levels of IIJA spending in this report relied on the White House’s Guidebook to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

The data from these sources were often inconsistent and incomplete. The Comptroller’s Office cross-referenced multiple data sources with individual agency reporting to create as comprehensive and accurate of a picture as possible of the federal funding flows to New York City and State. Estimates for the amount of highway formula funds spent in New York City and suballocated to NYCDOT were compiled from multiple sources, including New York State’s FFY 2023-2026 STIP, New York State’s FFY 2019-2022 STIP (provided directly by NYSDOT to the NYC Comptroller’s Office), NYMTC’s most recent quarterly update of the FFYs 2023-2027 Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP) Project Listing, and funding estimates provided by the City of New York. However, funding information in NYMTC’s most recent quarterly updated TIP differs from NYMTC’s adopted TIP for the same time period, and both differ slightly from information in the latest NYSDOT STIP and project obligation list for FFY 2022. Additionally, the City of New York confirmed receipt of some competitive grant awards that do not appear in the White House’s BIL Maps Dashboard. These sources are updated on different timelines and include some conflicting or inconsistent information. This report reflects the Comptroller’s Office’s best understanding of the available data.

Acknowledgements

This report was authored by Sindhu Bharadwaj, Senior Policy Analyst for Transportation, Sanitation, and Infrastructure, and Louise Yeung, Chief Climate Officer. Dan Levine, Policy Data Analyst, and Annie Levers, Deputy Comptroller for Policy, supported the data analysis. Archer Hutchinson, Creative Director, led the graphic design and report layout.

Appendix: Reference Tables

National IIJA Funding by Program Area

| Program Area/Category | Funding Amount (billions) | % of IIJA Funds |

| Roads, Bridges, and Major Projects | $325.67 | 39% |

| Public Transit | $82.59 | 10% |

| Clean Energy and Power | $74.95 | 9% |

| Broadband | $64.41 | 8% |

| Water | $64.25 | 8% |

| Passenger and Freight Rail | $63 | 7% |

| Resilience | $37.87 | 5% |

| Safety | $37.63 | 4% |

| Airports and Federal Aviation Administration Facilities | $25 | 3% |

| Environmental Remediation | $21.6 | 3% |

| Electric Vehicles | $18.63 | 2% |

| Ports and Waterways | $16.67 | 2% |

| Other | $8.64 | 1% |

| Total | $840.91 | 100% |

Source: White House Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Guidebook

National IIJA Funding by Administering Agency

| Administering Agency | Funding Amount (billions) | % of IIJA Funds |

| Department of Transportation | $565.61 | 67% |

| Department of Energy | $74.91 | 9% |

| Environmental Protection Agency | $60.86 | 7% |

| Department of Commerce | $51.16 | 6% |

| Department of Interior | $30.61 | 4% |

| Department of Defense (Army Corps of Engineers) | $17.06 | 2% |

| Federal Communications Commission | $14.21 | 2% |

| Department of Agriculture | $9.77 | 1% |

| All Others* | $16.72 | 2% |

| Total | $840.91 | 100% |

*Other agencies administering IIJA funds include the Appalachian Regional Commission, Denali Commission, Department of Health and Human Services, and Department of Homeland Security

Source: White House Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Guidebook

U.S. Department of Transportation Funding

| Bureau | Funding Amount (billions) | % of USDOT IIJA Funds |

| Federal Highway Administration | $337.89 | 60% |

| Federal Transit Administration | $91.37 | 16% |

| Federal Railroad Administration | $66 | 12% |

| Office of the Secretary | $30.35 | 5% |

| Federal Aviation Administration | $25 | 4% |

| All Others* | $15 | 3% |

| Total | $565.61 | 100% |

*Other USDOT bureaus responsible for IIJA programs include FMCSA, PHMSA, NHTSA, and the Maritime Administration.

Source: White House Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Guidebook

FHWA Formula Program Funding Across New York State (FFY22-FFY26)

| FHWA Formula Program | New York State Apportionment (millions) |

| National Highway Performance Program | $5,943 |

| Surface Transportation Block Grant Program | $2,891 |

| Highway Safety Improvement Program | $640 |

| Railway-Highway Crossings Program | $32 |

| Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality Program | $1,038 |

| Metropolitan Planning | $171 |

| National Highway Freight Program | $302 |

| Carbon Reduction Program | $257 |

| PROTECT Program | $293 |

| Bridge Improvement Program | $2,044 |

| National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Program | $175 |

| Total | $13,786 |

Source: FHWA FY 2022 – FY 2026 State-by-State Apportionments

IIJA Transportation Funding Across New York State (FFY22-FFY26)

| Program Area/ Category |

Statewide Formula Funding (millions) | Statewide Competitive Grants (to date) (millions) | Statewide Total (millions) | Total Funding Awarded Directly to City of New York (millions) |

| Roads, Bridges, and Major Projects | $12,975 | $590.4 | $13,565 | $1,383 |

| Public Transit | $11,200 | $9,886 | $21,086 | $66 |

| Safety | $641 | $44.2 | $685 | $87 |

| Airports and FAA Facilities (to date) | $273.6 | $53.8 | $327 | $0 |

| Electric Vehicles | $175 | $69.6 | $245 | $18 |

| Ports and Waterways (to date) | $35.6 | $111 | $147 | $30 |

| Total | $25,300.2 | $10,755.2 | $36,055 | $1,584 |

Sources: White House Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Guidebook, New York State FFY 2023-2026 Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) Maps Dashboard, NYS Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), and New York City Mayor’s Office of Operations

Footnotes

[1] Encompasses all funding invested in the five boroughs, including funding controlled by State and federal entities (like MTA, Port Authority, Army Corps of Engineers, and NYSDOT).

[2] Estimates for the amount of highway formula funds spent in New York City and suballocated to NYCDOT were compiled from multiple sources, including New York State’s FFY 2023-2026 Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), New York State FFY 2019-2022 Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (provided directly by NYSDOT), the most recent quarterly update of New York Metropolitan Transportation Council’s (NYMTC) FFYs 2023-2027 Transportation Improvement Plan (TIP), and funding estimates provided by the City of New York. These sources are updated on different timelines and include some conflicting or inconsistent information. This report reflects the Comptroller’s Office’s best understanding of the available data. See Methodology section for more details.

[3] See previous footnote.

[4] Excludes funds from programs that NYS has yet to allocate, including the Bridge Formula Program, Promoting Resilient Operations for Transformative, Efficient, and Cost-saving Transportation (PROTECT) formula program, and National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program.

[5] Encompasses formula funding for aviation and FAA facilities, ports, ferries, and waterway programs to date.

[6] FTA will disburse the $6.88 billion for the Gateway project in tranches, meaning GDC will receive portions of the total award over a period of several years. It is likely FTA will deliver part of the $6.88 billion grant after the IIJA expires in 2026.

[7] The grant information in this table is current as of June 30, 2023.

Endnotes

[1] UPDATED FACT SHEET: Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. (2021, August 8). The White House. www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/08/02/updated-fact-sheet-bipartisan-infrastructure-investment-and-jobs-act

[2] Infrastructure. (n.d.). NYC Department of Design and Construction. www.nyc.gov/site/ddc/projects/infrastructure.page

[3] Denecke, A. (2022, July 21). New York Earns C on its 2022 Infrastructure Report Card; Solid Waste Strong, Roads and Transit Most in Need. 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure. https://infrastructurereportcard.org/new-york-earns-c-on-its-2022-infrastructure-report-card-solid-waste-strong-roads-and-transit-most-in-need/

[4] Jones, C., Blackburn, J., Freudenberg, R., Taylor, T. A., Pernanand, R. (2023 March). Building Better Streets: Improving Capital Street Infrastructure Delivery for a Re-envisioned Right-of-Way. Regional Plan Association (RPA). https://rpa.org/work/reports/building-better-streets

[5] Asset Information Management System (AIMS): Condition and Maintenance Schedules for Major Portions of the City’s Fixed Assets and Infrastructure. (2022, December 8). City of New York. www.nyc.gov/assets/omb/downloads/pdf/as12-22.pdf

[6] Bipartisan Infrastructure Law – Section 25019(a) “Local Hiring Preference for Construction Jobs”. (2022, June 8). U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration. www.fhwa.dot.gov/construction/hiringpreferences/qanda060822/

[7] State of New York: 7387B – 2023 – 2024 Regular Sessions – in Senate. (2023, May 22). New York State Senate. https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2023/S7387B

[8] Justice 40: A Whole-of-Government Initiative. (n.d.). The White House. www.whitehouse.gov/environmentaljustice/justice40/

[9] Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) Maps Dashboard. (2023). The White House|BUILD.gov https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/BIL_Map_Data_CAOMAR172023.xlsx

[10] Bipartisan Infrastructure Law: Estimated State-by-State Public Transit Formula Apportionments. (2022, January 1). American Public Transportation Association. www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/APTA_IIJA_Public_Transit_State-by-State_Formula_Apportionment_Table_01-01-2022.pdf

[11] ibid

[12] Estimate provided by MTA

[13] Public Transportation Ridership Report: Fourth Quarter 2022. (2023, March 1). American Public Transportation Association. www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/2022-Q4-Ridership-APTA.pdf

[14] FY 2022 – FY 2026 State-by-State Apportionments Under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Public Law 117-58 (Bipartisan Infrastructure Law). (n.d.). Federal Highway Administration. www.fhwa.dot.gov/bipartisan-infrastructure-law/docs/Est_FY_2022-2026_Apportionments_Infrastructure.pdf

[15] A Guidebook to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. (2023, May). The White House|BUILD.gov. www.whitehouse.gov/build/guidebook/

[16] ibid

[17] STIP Project List and Data Download, (n.d.). New York State Department of Transportation. https://www.dot.ny.gov/programs/stip/stip-project-rpt

[18] Kuntzman, G. (2022, June 30). As US Supreme Court Guts EPA Power, NYS Goes on a Highway Expansion Binge. Streetsblog NYC. https://nyc.streetsblog.org/2022/06/30/as-us-supreme-court-guts-epa-power-nys-goes-on-a-highway-expansion-binge

[19] Shore PKWY Viaduct Rehab Over Shell RD/Subway Yard, Kings CO: Project ID No.X02172. (n.d.). New York State Department of Transportation. https://www.dot.ny.gov/portal/pls/portal/MEXIS_APP.DYN_PROJECT_DETAILS.show?p_arg_names=p_pin&p_arg_values=X02172

[20] Bruckner EXPWY Mobility Improvements I-95 and NY 908A (Hutchinson River PKWY to Bartow Ave.), Bronx, NYC: Project ID No. X73179. (n.d.). New York State Department of Transportation. https://www.dot.ny.gov/portal/pls/portal/MEXIS_APP.DYN_PROJECT_DETAILS.show?p_arg_names=p_pin&p_arg_values=X73179

[21] Issue Brief: Estimating the Greenhouse Gas Impact of Federal Infrastructure Investments in the IIJA. (2021, December 16). Georgetown Climate Center. https://www.georgetownclimate.org/articles/federal-infrastructure-investment-analysis.html

[22] Getting From A to B. (n.d.). New York State: Climate Act. https://climate.ny.gov/Get-Involved/Getting-from-A-to-B

[23]NYC Streets Plan. (2021, December 1). New York City Department of Transportation. https://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/pdf/nyc-streets-plan.pdf

[24] A Guidebook to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. (2023, May). The White House|BUILD.gov. www.whitehouse.gov/build/guidebook/

[25] Adams, E. (2023, April). PlaNYC: Getting Sustainability Done. The City of New York. https://climate.cityofnewyork.us/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/PlaNYC-2023-Full-Report-low.pdf

[26] Raise Grants: Rebuilding America Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity. [Fact Sheet]. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Transportation. https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/2022-09/RAISE%202022%20Award%20Fact%20Sheets_1.pdf

[27] New York City FFYs 2023-2027 TIP Project Listing. (2023, June). New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. www.nymtc.org/Portals/0/Pdf/TIP%20products/TIP%20Project%20Listings%202023/June/New%20York%20City%20FFYs%202023-2027%20TIP%20Project%20Listing%20(June%202023).pdf?ver=heQIOzr0Ti-2iWXVrii-0g%3d%3d

[28] Van Wyck Expressway Capacity and Access Improvements to JFK Airport Project FDR/FEIS – Executive Summary. (n.d.). New York State Department of Transportation. https://www.dot.ny.gov/vwe/repository/VWE_Project_FEIS_Executive_Summary.pdf

[29] About RAISE Grants. (n.d.). U.S. Department of Transportation. https://www.transportation.gov/RAISEgrants/about

[30] Van Wyck Expressway Capacity and Access Improvements to JFK Airport Project FDR/FEIS – Chapter 5: Public Involvement. (n.d.). New York State Department of Transportation. https://www.dot.ny.gov/vwe/repository/VWE_Project_FEIS_Chapter_5-Public_Involvement.pdf

[31] Local Laws of the City of New York for the Year 2022: No.115. (n.d.). The New York City Council. https://nyc.legistar1.com/nyc/attachments/6f47fb9a-27af-49d8-b46d-e35be218ee62.pdf

[32] Kuntzman, G. (2022, August 11). What Does Schumer’s ’Greenway Bucks’ Mean for NYC. Streetsblog NYC. https://nyc.streetsblog.org/2022/08/11/what-does-schumers-greenway-bucks-mean-for-nyc

[33] Van Wyck Expressway Capacity and Access Improvements to JFK Airport Project FDR/FEIS – Chapter 5: Public Involvement. (n.d.). New York State Department of Transportation. https://www.dot.ny.gov/vwe/repository/VWE_Project_FEIS_Chapter_5-Public_Involvement.pdf

[34] Handy, S., and Boarnet, M. G. (2014a). Impact of Highway Capacity and Induced Travel on Passenger Vehicle Use and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Policy Brief. Prepared for the California Air Resources Board. Retrieved from: https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/Impact_of_Highway_Capacity_and_Induced_Travel_on_Passenger_Vehicle_Use_and_Greenhouse_Gas_Emissions_Policy_Brief.pdf

[35] Nonko, E. (2017, July 27). Robert Moses and the decline of the NYC subway system. https://ny.curbed.com/2017/7/27/15985648/nyc-subway-robert-moses-power-broker

[36] Marzlock, R. (2012, October 11). Making way for Moses’ new Van Wyck. https://www.qchron.com/qboro/i_have_often_walked/making-way-for-moses-new-van-wyck/article_5ac5ae08-3c28-5871-b005-b78e7d05306d.html

[37] Demographics by Neighborhood Tabulation Area (NTA). (2020, November). New York City Department for the Aging. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/dfta/downloads/pdf/reports/Demographics_by_NTA.pdf

[38] New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. (n.d.). Environmental Justice Areas [Map]. https://nycdohmh.maps.arcgis.com/apps/instant/lookup/index.html?appid=fc9a0dc8b7564148b4079d294498a3cf

[39] Pollack, S. (2022, April 8). Policy on Using Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Resources to Build a Better America. US Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/legsregs/directives/notices/n4510867.cfm