Executive Summary

Within a school, there is no more important influence on student learning and achievement than having high quality teachers – the gatekeepers of knowledge who light the path not just toward reading, writing and arithmetic, but to colleges, careers and beyond. A strong educator is the single most important in-school factor for improving academic outcomes of students. Like any profession, teaching also requires practice and professional development to build effective skills and expertise. Research increasingly shows that how teachers are prepared directly influences how long they remain in the profession and that real world, on-the-ground preparation exposes teacher candidates to the specific strengths, challenges, and vulnerabilities they will encounter in classrooms.[1]

Unfortunately, far too many teachers across America enter the classroom without adequate time to develop the skills needed to succeed – a problem that is especially acute in New York City, where it is all too common for teachers to have as little as two weeks of classroom training before taking on the myriad responsibilities of running their own classroom. The unfortunate result is that despite the richness of New York City schools, approximately 20 percent of new teachers — a number far higher than the rest of New York State — leave their classrooms each year either to work in another school or district, or to leave the profession all together. This annual exodus exacts not just an enormous fiscal toll on the system, but more importantly an educational one on our students.[2]

Teachers leave their classrooms for many reasons, often due to difficult working conditions. Overcrowded classrooms, lack of support from school or district leadership, or a desire to work in a more collaborative environment are often cited as reasons why teachers leave their school, or the profession. Improving preparation for teachers before they enter the classroom is one area that can affect teacher retention. While other systemic problems related to working conditions will continue to need appropriate mitigation, preparing new teachers well and paving the way for their success is an essential first step in stemming the tide of teacher turnover.

This report, by New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, provides a detailed examination of teacher retention in New York City and reveals how it impacts differing boroughs and school districts, including those most impacted by poverty. It also makes the case for greatly expanding a proven model for improving teacher retention – namely a year-long, paid teacher residency program designed to give new teachers the training and mentorship they need to succeed in the classroom.[3] By ensuring pre-service teachers can experience a rigorous full-year classroom apprenticeship alongside a mentor teacher, candidates can practice the skills they will need to address the social and instructional challenges they will face when leading a classroom of their own.

There is no question that bold action is needed to confront the scope of the problem in New York City, where data compiled by the Comptroller’s Office found that:

- The City struggles to retain its newest teachers. In fact, 41 percent of all teachers hired in the 2012-13 school year left the system within five years. Specifically, of the 4,600 teachers hired in the 2012-13 school year 1,882 teachers, had left the system by 2017-18, roughly equal to the total number of teachers working in Cleveland, Ohio.[4]

- On average, turnover rates across all public schools in New York City are about 15 percent. This compares with annual teacher turnover rates of 11 percent in New York State. Among City teachers with fewer than five years of experience, annual turnover is just under 20 percent.[5]

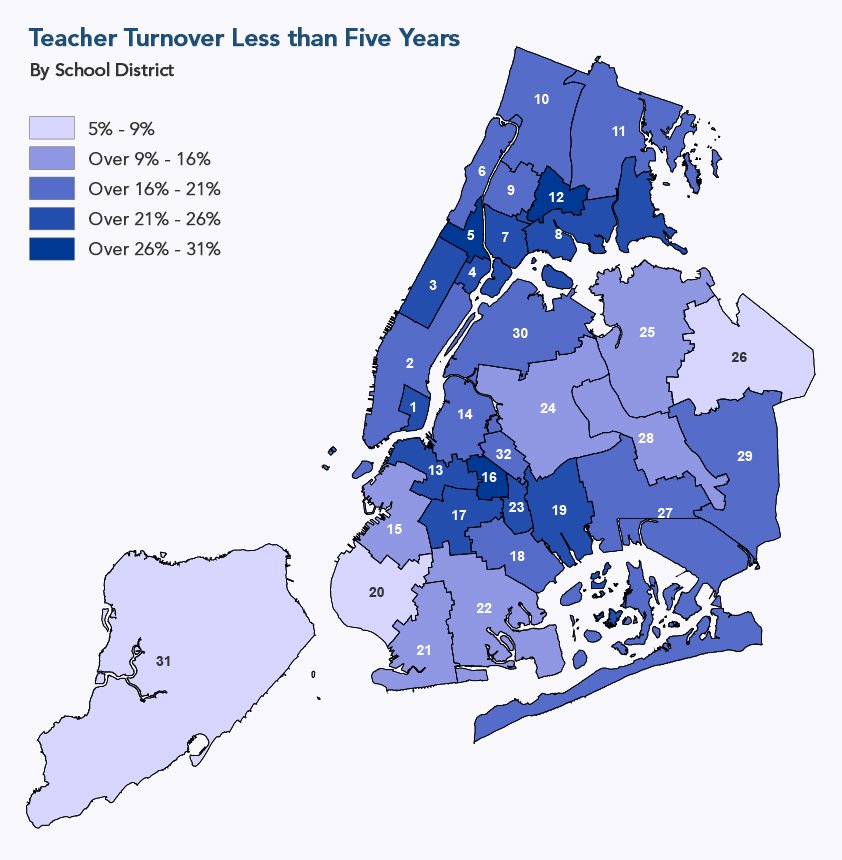

- In some local districts, teacher churn is much higher than the citywide average. Turnover among new teachers in Community School District 12 in the Bronx, for instance, is 31 percent.

- The Bronx and Manhattan both have turnover among teachers with fewer than five years of experience of 22 percent

- To keep up with the constant demand to fill classrooms, the City is continually recruiting and hiring new educators. Approximately one third of teachers in the City have fewer than five years of experience.[6]

- The revolving door of inexperienced teachers is particularly damaging for the City’s most vulnerable students. Data shows that schools in neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty often experience both higher percentages of new, inexperienced teachers, as well as higher rates of turnover, compounding other deep inequities in the system.

- The educational impact of all this turnover is particularly profound when viewed through the prism of teacher specialties. New York City has teacher shortages in fifteen subject areas, including: Math, Science, English as a Second Language, Art and Music Education, World Languages, Special Education, Language Arts, Health and Physical Fitness.[7]

- In addition, despite the diversity of New York City’s student body– which is 41 percent Hispanic, 26 percent African-American, 16 percent Asian and 15 percent white – approximately 60 percent of New York City teachers are white.[8]

To address the problems associated with teacher turnover, the Comptroller’s Office recommends that the City and the Department of Education invest in teacher training through a large-scale, paid teacher residency program that provides a full year of high-quality experiential training in classrooms prior to teacher certification. When fully scaled, a teacher residency program would place 1,000 resident teachers in City schools each year, significantly improving the quality and stability of the teaching pipeline. A teacher residency program of this scale would represent the largest in the U.S. and send a signal that bold investment in education is required to support quality instruction in all classrooms.

Similar programs already exist in Boston, Denver, and Washington D.C., and several successful pilot programs in New York City serve as a model for the nation. In Boston, for example, teachers trained in the residency program have a 20 percent higher retention rate than graduates of traditional university preparation programs. The Urban Teacher Residency (UTR) pilot in New York City has shown much stronger retention in the Title I schools where it places residents. A recent evaluation found that UTR-trained teachers had lower attrition by half when compared to other New York City Department of Education high school teachers.[9]

Specifically, the Comptroller recommends that the City:

- Establish a large-scale teacher residency with capacity to eventually include all teachers currently in the New York City Teaching Fellows preparation program, in order to meet a high proportion of annual classroom staffing needs.

- Follow best practices from model teacher residencies around the U.S. and globally that:

- Ensure participants work under and alongside a single, accomplished mentor;

- Are a year-long commitment;

- Provide a stipend to cover residents’ living expenses during the residency year;

- Reflect a strong collaboration between the school district and institutions of higher education.

- Leverage the partnership between DOE and institutions of higher education in the City to provide residents with reduced tuition. Ideally, this means inviting leaders of higher education institutions early into the planning process to ensure their programs commit to supporting DOE through a strategy of school-based residencies.

- Phase in implementation gradually, so that the New York City Teaching Fellows program can continue to fill classroom vacancies quickly, while also training a subset of teachers through a year-long in-classroom apprenticeship under the mentorship of a highly qualified teacher. The City could expect to regain some of the initial investment in a large-scale teacher residency program through cost savings from improved teacher retention. Some costs could be repurposed as well, such as funding for substitute teaching or tutoring, as some instructional tasks are shifted to residents.

- Focus on quality by ensuring that adequate time and funding are available so that each school that hosts a cohort of residents would spend a year in a centrally-coordinated partnership development phase with the approved teacher preparation provider. This time would be spent identifying and planning recruitment needs, aligning curriculum with school and district needs, planning how to incorporate coursework into residents’ classroom experience, and establishing a partnership that emphasizes continuous improvement.

- Develop and support effective mentor teachers so that they have the skills and resources necessary to fully integrate residents into the daily routines of their classrooms. For example, mentor teachers will need to be familiar with adult learning patterns and have the necessary tools to provide instructional coaching and effective feedback to residents. Mentors will need to be well aware of the sequence of coursework being completed by residents so it can be practiced appropriately in the classroom. Providing opportunities for mentoring can serve to expand the teacher leadership/career pathway program launched in New York City in 2013-14, which has been shown to help retain experienced teachers as well as improve their instructional practice.[10]

At full scale, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that a large scale residency would have an annual cost of about $40 million. This does not, however, take into account potential savings from redistributing some instructional tasks within schools where residents are placed, including substitute teaching, tutoring, or leading afterschool instructional activities. Such an important investment in a world-class professional teaching workforce can be expected to benefit students, teachers, schools, and the City we live in for generations to come.

With a robust teacher residency program, New York City can prepare teachers for the real challenges of working in schools while reducing teacher turnover and its associated costs. Most importantly, when teachers are well-prepared, students are more likely to succeed. In a City with such huge disparities across schools, having a consistent pipeline of highly qualified and well-prepared teachers will help bring equity to the largest school system in the nation.

Introduction: Today’s Teaching Profession

The teaching profession in the U.S. today is at a crossroads. Across the country, teachers have been laboring under stagnant wages and slashed budgets. At the same time, the need to attract talented teachers to the profession has never been greater. Research increasingly illustrates the positive role teachers play in driving academic gains, particularly for low-income students. A strong educator is the single most important in-school factor in improving academic outcomes for students, with deep implications in everything from literacy to college completion.[11]

Despite the importance of the teaching profession to a vibrant society, fewer college students consider the teaching profession a viable career option. Recent analysis of U.S. Department of Education data by the Rockefeller Institute reveals that individuals completing teacher preparation programs in New York State dropped by 39 percent between 2010 and 2015. In the 2015-16 school year, 14,716 people completed teacher preparation in New York State, down from 24,135 in 2010.[12] These trends are mirrored within the City University of New York, with enrollment and completion of education programs on the decline. Total fall enrollment in classroom teacher programs at CUNY was 11,147 in 2018, down from 12,845 in 2010, a 13 percent decrease (see figure 1). Similarly, CUNY’s training programs are also graduating fewer teachers, with 2,193 graduates in 2017, down from 3,198 in 2010.[13]

Figure 1: Total Fall Enrollment in CUNY Education Programs

Source: CUNY Institutional Research Database (IRDB)

Indeed, as American teachers increasingly head to state capitols to give voice to the inequitable pay and limited opportunities for professional advancement, it is little wonder that the profession struggles to attract newcomers.

The first and most obvious factor in this nationwide decline is that salaries that are significantly lower than for similarly educated professionals. A 2018 report from the Economic Policy Institute found that total wages and benefits for teachers have stagnated relative to other comparably educated workers, and in no state in the U.S. do teachers earn a wage that is comparable with other college graduates.[14]

In addition to low pay, the profession also lacks supportive working conditions to encourage teachers to thrive throughout their careers. Many early career teachers enter the profession driven by eagerness to make a positive difference in the lives of children and youth, but upon entering schools, are faced with challenges that can quickly erode their enthusiasm. Lack of support, overcrowded classrooms, facilities problems, need for basic supplies, or few opportunities for meaningful collaboration or decision-making are demoralizing for professionally trained, talented educators and can significantly impact a teacher’s decision to leave the classroom.[15] According to results from the national Teacher Follow-up Survey (TFS), the most frequently cited reason teachers quit after their first year on the job is dissatisfaction with working conditions.[16] As with any profession, providing a clear career pathway and incentives to develop and improve ensures that the most talented are encouraged and rewarded for their efforts.

Given the declining interest in the teaching profession, it is crucial to target investments towards retaining those who make the choice to become teachers. Providing teacher candidates an affordable pathway to high-quality preparation is key to improving teacher retention. Researchers have found that teachers with little or no preparation leave at rates two to three times as high as those who have had comprehensive preparation.[17] Nations with the highest student achievement ratings have aggressive career ladders for teachers, with school structures that expect – and support – teachers to perfect their teaching practice through formal mentoring and coaching. In these arrangements, mentor teachers work alongside pre-service and early-career teachers and benefit from increases in compensation, responsibility, and autonomy in their career. Early career teachers who are paired with a mentor gain both personal insight and constructive feedback from experienced teachers.[18]

Impacts of Teacher Turnover

High teacher turnover has a deep impact on municipal education budgets. According to research by the Learning Policy Institute, teacher turnover, particularly in dense, urban districts, can cost a school district as much as $20,000 per teacher.[19] This includes the cost of recruiting new teachers, and providing on-boarding training and professional development. When a teacher leaves after one or two years, this investment is effectively lost and creates the need for ever-more recruitment, making it difficult for school systems to build a stable workforce.

Perhaps the deepest impact of high teacher turnover is felt by students, especially in schools with concentrated poverty where many students already face steep challenges to learning. A study published in 2013 observed academic outcomes of 850,000 New York City fourth and fifth grade students over eight years.[20] The study considered the average effect of teacher turnover on student achievement and found that in grades with the highest levels of turnover, students scored lower on standardized tests in both math and English language arts, with particularly strong effects on struggling students. Turnover was also found to have a deeply negative impact on other teachers who remained in a school. Diminished trust and eroded morale are prevalent in schools with high teacher turnover, important environmental factors that also contribute to student achievement. [21]

Teachers who work in high poverty districts are most at risk for leaving the profession before five years – nationwide, teachers in such schools with high concentrations of students of color have 70 percent higher turnover rates than average.[22] These schools tend to be chronically under-resourced and are often difficult working environments that lead to high turnover. In some cases, such schools are geographically isolated making it difficult to recruit and retain a stable workforce. High need schools especially face a revolving door of new teachers, straining the ranks of established teachers who remain in the school and imperiling school improvement efforts. Teachers of color, who are in high demand in districts across the nation, disproportionately teach in such schools and have lower teacher retention rates than white teachers.[23]

Retention, not Recruitment, to Blame

While enthusiasm for the teaching profession has suffered recently, teacher shortages facing many states and cities across the U.S. are not caused solely by failed recruitment efforts. Rather, high rates of teacher turnover are a much more significant, and costly, part of the equation. A 2017 report by the Learning Policy Institute (LPI) reviewed data from the National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey to understand which teachers are most prone to leaving the profession and why. The study found that teacher turnover rates are significantly higher in Title I schools serving predominantly low-income students, and schools that have large concentrations of students of color. Likewise, teachers who teach math, science, special education, and English language learners are more likely to leave their job than teachers of other subjects.[24] Of the teachers who leave the profession, according to LPI, more than two-thirds leave for a reason other than retirement. On a global scale, teacher attrition rates in the U.S. are twice as high as in other nations with high performing education systems.[25]

Some amount of turnover is expected in any industry and can have the positive effect of weeding out individuals who are poorly suited to the field. However, when attrition levels exceed standard hiring, it is often a sign that something is broken in the career pipeline. To make the most of human capital, industries typically work to build a strong pool of professionals with training that is purposefully aligned to industries’ needs. In the medical profession, for example, medical schools are both highly selective and rigorous, ensuring top performers enter the field. Medical training requires in-depth experiential learning that is directly aligned to actual needs of the medical field – medical students serve as residents in a hospital or clinic for three to five years before completing their degree and becoming fully certified doctors. This deeply practical learning environment is essential for adequately preparing doctors for the challenges of the profession.

Unfortunately, within teacher training programs there is not always a similar alignment between educational theories and practices taught and the actual needs and working conditions in schools. While this is changing in some states and municipalities, the best examples of teacher preparation aligned to district educational goals can be found in other countries, namely the same high-performing educational systems that also boast low teacher attrition, including Finland, Singapore, and Shanghai. In these countries, teacher preparation programs require extended clinical classroom training that successfully bridges theory and practice.[26] When teachers’ training adequately prepares them for the range of student needs they will encounter in the classroom – not just in theory, but through experiential practice – teachers are more effective from their first day on the job. Schools and students benefit because resources are not constantly needed to hire and train new teachers.

New York City: A System Marked by Churn

Constant Need for Classroom Teachers

New York City’s public schools employ over 78,000 teachers and are constantly in need of qualified teachers.[27] Despite rigorous and ongoing recruiting throughout the school year, turnover is high and teacher shortages persist, especially in certain schools or teaching areas. To fill these gaps, each year the Department of Education hires approximately 6,000 new teachers each school year.[28]

Before describing the extent of the turnover problem in New York City, it is important to start with a note on the terminology used in this report. For our purposes, teacher attrition refers to employees who leave the profession entirely, whether through retirement, resignation, or termination. Turnover is more expansive and includes both those who leave the system for good, as well as teachers who may leave their classroom and move to either another teaching position in a different school, or a new position within school administration but remain on the DOE payroll. New York State metrics track average turnover of teachers, while City payroll data can provide a more detailed look at attrition. Findings from both of these data sources are used and discussed below.

Those who move within the profession or leave the classroom: turnover rates in NYC

The rate at which teachers left New York City schools or classrooms reached a troubling high in the 2012-13 school year when the teacher turnover rate was 18.6 percent of all teachers, and 20.5 percent of all new hires with less than five years of experience. Since that time, the rate of turnover has fluctuated in the City, and after several years of decline, in 2017-18, teacher turnover rates stood at about 15 percent for all teachers and 19 percent for teachers with fewer than five years of experience, as of the most recent data reported to the State Education Department (Figure 2).[29] For comparison, in Chicago approximately 20 percent of teachers leave their classrooms each year.[30]

Figure 2: Teacher Turnover Rates – NYC

Source: Comptroller’s Office analysis DOE metrics as reported in the New York State Department of Education Report Card Database

New York City has significantly higher teacher turnover than the statewide average, which in 2017-18 was about 11 percent (Figure 3). The national turnover rate is about 16 percent.[31]

Figure 3: Turnover Rate Among All Teachers, NYC vs. NYS

Source: Comptroller’s Office analysis DOE metrics as reported in the New York State Department of Education Report Card Database.

As is the case nationwide, turnover rates in New York City vary greatly by academic areas, grade levels taught, location and other characteristics of the school. Schools with high concentrations of poverty and high-need students typically have the highest rates of teacher turnover. For example, among the City’s former Renewal Schools, a group of schools singled out as needing targeted resources to address low academic performance, turnover among teachers was 21 percent in the 2015-16 school year, higher than the city average.[32]

Teacher turnover is also higher in certain areas of the City, which can be masked by citywide numbers. In the 2017-18 school year, Staten Island had a teacher turnover rate of just 8 percent. Meanwhile, average turnover in the Bronx was approximately 19 percent, and over 22 percent among teachers with fewer than five years of experience (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Average Teacher Turnover by Borough

Source: Comptroller’s Office analysis DOE metrics as reported in the New York State Department of Education Report Card Database.

Further distinction is found at the district level. Among new teachers in Community School District 5 in Manhattan, turnover was 29 percent compared with the average turnover of 22 percent for new teachers in the borough, or 18 percent among new teachers in neighboring district two. District 12 in the Bronx had an average turnover rate of 26 percent among all teachers, and 31 percent among new teachers, significantly higher than statewide averages.

New Teacher Turnover Across NYC Community School Districts

Source: New York State Education Department, Report Card data, 2017-18

Those who leave: attrition rates in New York City

Citywide, about seven percent of teachers left the system between September 2017 and September 2018, similar to the nationwide attrition rate of about eight percent. The City’s attrition rate has for the most part remained constant, over seven percent and under eight percent, for the past decade.[33]

Of all the teachers who leave the Department of Education each year, more resign than retire or are terminated (Chart 2). Using data collected by the United Federation of Teachers, in 2016, 2,694 teachers resigned, more than the combined total of those who retired (1,816) or were terminated (234). Teachers who resign may be leaving the profession altogether, or leaving employment by the City Department of Education for another agency or jurisdiction.

Chart 2: NYC Teacher Retirements, Resignations, Terminations

Source: Comptroller’s Office analysis DOE payroll data collected by the UFT.

To better understand the scope of the City’s difficulty retaining newly hired teachers, the Comptroller’s office analyzed payroll data of cohorts of teachers, hired by DOE in the last ten years.[34] The analysis tracked the percentage of each cohort that left the DOE each year over five years, to arrive at a cumulative average of the percentage of a cohort that left the system within five years. DOE data show that over the past 10 years, more than 40 percent of teachers leave teaching within their first five years (Table 1). Specifically, of the 4,600 teachers hired in the 2012-13 school year, nearly 41 percent, or 1,882 teachers, had left the system by 2017-18.

Table 1: Loss of Pedagogues by Cohort, 2007-2017

| Year Hired | Yr < 1 | 1 Yr | 2 Yr | 3 Yr | 4 Yr | 5 Yr | 5 -year Cumulative Loss |

| 2007 – 2008 | 2.8% | 6.2% | 10.4% | 8.6% | 6.5% | 4.9% | 39.3% |

| 2008 – 2009 | 2.2% | 8.6% | 10.7% | 8.0% | 7.3% | 5.5% | 42.4% |

| 2009 – 2010 | 3.3% | 9.8% | 8.9% | 6.4% | 5.5% | 5.7% | 39.6% |

| 2010 – 2011 | 5.2% | 10.3% | 8.3% | 6.8% | 6.8% | 5.8% | 43.2% |

| 2011 – 2012 | 3.5% | 10.6% | 9.1% | 8.5% | 7.1% | 5.5% | 44.3% |

| 2012 – 2013 | 2.7% | 8.9% | 9.4% | 8.4% | 6.7% | 4.8% | 40.9% |

| 2013 – 2014 | 3.8% | 9.5% | 8.4% | 6.6% | 5.3% | – | |

| 2014 – 2015 | 2.1% | 11.4% | 9.1% | 6.8% | – | ||

| 2015 – 2016 | 2.8% | 12.0% | 8.2% | – | |||

| 2016 – 2017 | 2.9% | 12.3% | – | ||||

| 2017 – 2018 | 2.2% | – | |||||

| Average | 3.0% | 10.0% | 9.2% | 7.5% | 6.4% | 5.4% | |

| Cum Avg | 3.0% | 13.0% | 22.2% | 29.7% | 36.1% | 41.5% |

For the purpose of better understanding teacher retention, isolating the long-term employment trends among early career teachers is helpful. Based on averages since the 2007-08 school year, of teachers who leave the system within the first year of teaching, about half are due to resignations. After a year of teaching, however, resignations begin to steadily increase to account for 71 percent of departures after one year of teaching, and about 80 percent of all departures after two years of teaching (Chart 3). Resignations are by far the most common reason for early career teachers leaving, with terminations steadily declining to less than seven percent of all departures at a teacher’s tenth year of service.

Chart 3: Reason for departures by years of service, 2007 – 2017

Source: Comptroller’s Office analysis DOE payroll data reported in the New York Citywide Human Resource Management System. Data current as of April 2019.

Where New Teachers Work

In 2018, about a third of teachers Citywide had fewer than five years of teaching experience, according to reports in the annual Mayor’s Management Report. As shown in Chart 4 below, after a period of decline, the percentage of novice teachers in the system has been increasing steadily over the past five years. In FY 2006, 40 percent of all teachers had fewer than five years of experience. Over the next eight years, this percentage declined 40 percent to 24 percent in FY 2013, before increasing again to 33 percent in FY 2018.

Chart 4: Percent of teachers with fewer than 5 years of experience

Source: NYC Comptroller’s analysis of Mayor’s Management Reports, FY06-FY18.

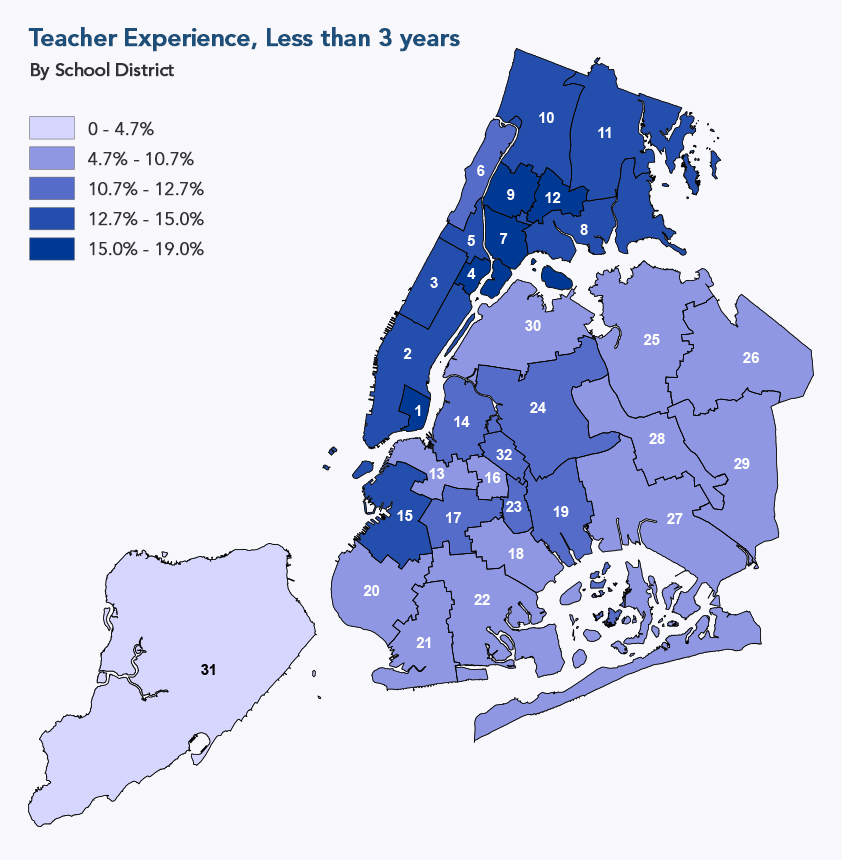

A different dataset, provided to the New York State Education Department and reported in the State Report Card Database, provides the percentages of teachers with fewer than three years of experience by local community school district. Certain districts have much higher percentages of the newest teachers. Teachers with fewer than three years of experience account for more than 16 percent of all teachers in Community School Districts 7, 9 and 12 in the Bronx and Districts 1 and 4 in Manhattan (see map below). [35]

It is important to reiterate that novice teachers are, on average, less effective than teachers with more experience.[36] Additionally, turnover among early career teachers adds additional, hidden costs in New York City schools. Hard-to-staff schools that experience a constant churn of novice teachers are caught in a vicious cycle where school improvement plans become much harder to realize, in part because teaching staff is continually changing, further contributing to systemic inequities across the district. It is critically important, then, to ensure that the City seeks ways to incentivize equitable distribution of experienced teachers, and to ensure that students in high-need schools are not routinely exposed to the most inexperienced teachers who are also most likely to leave.

Percentage of teachers with fewer than three years of experience, by district

Source: New York State Education Department, Report Card Database, Map shows three years average, 2015-2017

Teacher shortage areas in NYC

Despite continual recruitment and hiring, New York City still has considerable teacher staffing needs. The U.S. Department of Education documents teacher shortage areas by state and district, and publishes the findings annually to assist recruitment efforts and individual teachers who are seeking available job opportunities. According to the most recent reported shortage areas, from the current 2018-19 school year, New York City has teacher shortages in fifteen subject areas, including: Math, Science, English as a Second Language, Art and Music Education, World Languages, Support Staff, Special Education, Language Arts, Health and Physical Fitness.

Teacher shortages in any subject area are concerning. However, in the case of instruction for multilingual learners (MLLs), these shortages also represent the City’s lack of compliance with State regulations. Recently adopted regulations require that multilingual Learners are provided “opportunities to achieve the same educational goals and standards that have been established by the Board of Regents for all students.” To accomplish this, the regulation mandates staffing levels, and requires units of study for MLL students at varying proficiency levels. Integrated English as a New Language instruction (ENL), now mandated for MLL instruction, requires more teachers certified in English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL).[37] With over 160,000 multilingual learners enrolled in New York City schools, recruiting and retaining well-qualified teachers who can support this population is crucial to academic progress for these students, in accordance with state regulations.[38]

New York City schools lack teachers of color

The importance of a racially diverse teaching force that reflects the demographics of the student body is an issue that has gained renewed attention in New York and across the nation. Education researchers have examined the benefits that teachers of color bring to classrooms, particularly their varied perspectives on subject material, as well as the value of the interpersonal connections with students of color.[39]

In New York City, roughly 60 percent of the teaching force is white, while less than 15 percent of the student body is.[40] Recognizing the importance of and need to hire a more diverse workforce, in 2016 the de Blasio administration launched the NYC Men Teach initiative, which focused on recruiting men of color to join the teaching profession. The initiative had an original goal of placing 1,000 men of color in City classrooms by December 2018. According to the FY18 Mayor’s Management Report, the program has placed approximately 400 full-time teachers in New York City classrooms, with another 542 participants enrolled in teacher training programs through CUNY.

Nationwide, targeted recruitment efforts have resulted in exceptional growth of the number of teachers of color in classrooms, more than three times the growth rate of white teachers.[41] The success of recruitment, however, has been overshadowed by the high turnover experienced by teachers of color nationwide; in the 2012-13 school year, retention among teachers of color was 8 percent lower than for white teachers.[42]

High turnover among teachers of color is driven by several factors. As noted above, teachers of color more often teach in urban schools with high concentrations of poverty which also have higher teacher attrition. Additionally, teachers of color also more often enter the career through an alternative teacher certification programs, which typically have higher turnover rates (as will be discussed below).[43]

In New York City, the NYC Men Teach program shows promise for placing more male teachers of color in classrooms. However, to protect this progress, New York City must work to ensure that all teachers are well prepared before entering the classroom and are receiving necessary supports and mentorship to ensure long-term success.

Alternative Certification Programs

Quality teacher preparation

Investing in the preparation of teachers and supporting them in the early years of their careers has long-term benefits for the entire education system. Teachers who are better prepared to address the special circumstances and academic needs of their students are not blindsided by the very real challenges facing many schools, particularly those with high concentrations of low-income students. As evidenced by numerous teacher surveys, however, many teachers do not feel their training fully prepares them for actual needs in their classrooms. A recent survey of New York City teachers found that less than 30 percent felt that they were “very well prepared” to provide instruction after their graduation.[44] Roughly a quarter of teachers surveyed responded that their training left them very well prepared to work with unique learners, including English language learners or students with special needs. A separate analysis of national teacher survey data found that teachers who felt inadequately prepared also responded that they were more likely to leave their teaching assignment within the year.[45]

On the other hand, when teacher candidates spend significant quality time in the classroom under the mentorship of a strong, experienced teacher-mentor as part of their preparation and prior to managing their own classroom, turnover is cut by as much as half.[46] Unfortunately, there is significant variation in the quality and opportunities for experiential learning offered across teacher preparation programs.

Traditional Programs

The traditional, university-based teacher preparation model does often require a few months of student teaching, typically built into the program’s credited coursework. Under this model, the teacher candidate pays for this professional experience through tuition, and is uncompensated for contributions they make to the school as a student teacher. Student teachers deserve to be paid for the work they do in classrooms – an inequity that is often overlooked. Many university-based programs are unaffordable for students with limited means, or unattractive for potential teachers who are unwilling to accumulate debt during their training. Such an arrangement presents a significant deterrent for attracting a pool of high-quality candidates from diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds.[47]

Alternative Programs

Alternative pathways to certification follow a model separate from traditional university programs. These programs typically incentivize recruitment into the teaching profession by offering reduced tuition and an accelerated timeline for training. By quickly preparing teacher candidates before placing them in the classroom as the lead teacher of record, these training programs may offer as little as two weeks of experiential training.

The Residency Model: A Proven Path

The residency model shows real promise for providing preparation that is closely aligned to actual needs in classrooms, while also improving teacher retention. Seen as a best practice in the highest performing educational systems around the world, teacher residencies have begun to take root across the U.S., with small pilots in cities including Boston, and Denver, as well as several in New York City. No residency program, however, operates on a scale that fully meets all district hiring needs.

As residents, teacher candidates spend a full year working in a classroom alongside an expert teacher who serves as a coach, mentor and guide and receiving feedback on their teaching practice. Once a resident becomes the lead teacher, usually in the second year of the residency program, they often continue to receive support and feedback. Similar in some ways to clinical medical residencies, teaching residencies give new teachers exposure to a range of academic or behavioral challenges in classrooms. With residents working under the direction of a seasoned professional, common classroom challenges become rich learning opportunities. And because a resident teacher functions as a co-teacher, schools benefit from a relatively inexpensive method to effectively reduce class-size.

NYC’s Current Alternative Preparation Programs

In response to the constant demand for classroom teachers, New York City has invested in several alternative teacher certification programs that quickly train and place teachers into schools, filling either hard-to-staff classrooms, or high-need subject areas. Some of these programs focus on fast-track teacher preparation, typically by enrolling teacher candidates in intensive summer coursework and then, by the start of the school year, participants are hired full-time by the Department of Education and begin working as the main teacher of record in a hard-to-staff classroom while completing coursework in the evenings. Little to no classroom experience is provided prior to program participants becoming full-time teachers.

The advantages of alternative teacher certification cannot be overlooked. With the focus on rapid preparation, these programs fill a need for recruitment in schools with chronic teacher vacancies. By offering free or reduced tuition, alternative certification programs make it much more affordable to obtain a teaching degree, opening access to the teaching profession to a wider and more diverse pool of candidates who might not have otherwise considered becoming a teacher. For example, both NYC Teaching Fellows and Teach for America (TFA) are highly selective programs that recruit talented professionals into New York City schools while removing financial barriers to achieving an education degree. TFA offers grant funds as well as transitional loans and food or housing support to new recruits, prior to their earning their first paycheck. TFA also prioritizes recruiting a diverse pipeline of teachers: in New York City, 62 percent of the 2016 cohort were people of color, 53 percent came from a low-income background, and 8 percent identified as LGBTQ. This is similar to the 2016 cohort from the NYC Teaching Fellows, which reported 66 percent of participants who self-identify as a person of color.[48]

Because program participants teach full-time, earning a full salary and benefits while completing their degree requirements, there is less need to take on student loan debt. And though burn-out is certainly an open concern, alternative preparation programs are fast-paced and intensive by design, attracting a select pool of high achievers.

On the other hand, teachers who enter the profession through these alternative pathways are less likely to remain in their schools or in the profession.[49] A 2017 analysis by the New York City Independent Budget Office (NYCIBO) of teacher retention rates by various teacher preparation programs shows the extent of variation in teacher retention between various pathways into teaching. According to the NYCIBO’s analysis, about 78.5 percent of new teachers who enter the profession through the city’s Teaching Fellows program remained at their original school after the first year, just slightly less than those who enter through a traditional pathway (80.7 percent). But by the third year, just 41 percent of teachers trained through the Teaching Fellows remained at their original school, compared with 60 percent of traditionally-trained teachers.[50]

| Total cohort | Percent who remained at original school after 1 year | Percent who remained at original school after 3 years | |

| NYC Teaching Fellows | 2,536 | 78.5% | 41.1% |

| TeachNYC Select | 428 | 74.2% | 51.6% |

| Teach for America* | 244 | 84.3% | 23.9% * |

| Traditional Pathway | 134 | 80.7% | 60.3% |

Source: NYCIBO: New York City Public School Indicators: Teachers: Demographics, Work History, Training and Characteristics of Their Schools. June 2017.

The goal of many alternative certification programs, including the NYC Teaching Fellows program, is to recruit teachers into hard-to-staff schools. By design, these programs place participants in challenging school settings, often those with high concentrations of poverty, and high teacher turnover. Based on the same IBO analysis, 36 percent of NYC Teaching Fellows, and 54 percent of Teach for America teachers were working in high poverty schools in 2014-15, compared with 24 percent of teachers who had gained certification through a traditional university pathway.

The high turnover among teachers trained in the City’s alternative certification programs suggests that such fast-track preparation lacks fundamental elements necessary for fully preparing teachers, particularly those who will be working with populations of high needs students or in otherwise challenging conditions. Experiential learning – prior to working solo in the classroom – is largely absent from the largest alternative certification programs, despite the value it adds to teacher preparation and its proven contribution in encouraging new educators to enter the profession. Without intending it, these certification programs may actually add cost through increased teacher turnover rates in already high-need schools.

| New York City Teaching Collaborative | |

|

Recognizing the need for and value of in-classroom preparation for teachers, New York City has been piloting the New York City Teaching Collaborative, which provides a four-month apprenticeship for program participants. While the program doesn’t fully match the profile of a full residency program, participants spend a full semester working in a high-need classroom as partner teachers alongside an experienced teacher who functions as an instructional coach. Participants receive a stipend during the apprenticeship and are provided with feedback and evaluated for effectiveness. Following the apprenticeship, teacher candidates are placed in the classroom. To date, DOE has not published outcomes on retention of teachers trained in this program. |

| NYC Teaching Fellows | |

|

NYC Teaching Fellows. Since 2000, the New York City Teaching Fellows program has recruited and trained new teachers in a highly selective and rigorous program. According to DOE estimates, over 12 percent of today’s teaching force in New York City, including 22 percent of all special education teachers, are alumni of the NYC Teaching Fellows program.[51] The program was run by The New Teacher Project until DOE announced in 2017 that it would begin managing the program in-house. The FY2019 budget for the New York City Teaching Fellows program was just over $22 million.[52]

Fellows in the program attend evening classes towards work on their master’s degree in education while serving as a full-time classroom teacher in a high need public school. The Department of Education partially subsidizes the cost of earning the master’s degree at a partner institution, and participants must commit to teaching throughout their degree program. |

Models of Success

As local districts increasingly seek policy solutions to the problems of teacher turnover, more attention has been given to teacher preparation programs. Some alternative preparation programs in other cities, and several here in New York City, provide a model for embedding in-classroom experiences into teacher training through extended residencies. Each of these share several common features, as well as offer interesting elements of program design to address a district’s unique circumstances. Importantly, however, there are no examples of residencies in the U.S. that meet a significant portion of annual district hiring needs.

Boston

Boston has the oldest teacher residency program in the nation, in operation since 2002. It has also set the standard in many ways for residency programs that have followed in other cities, in how programs are shaped and sustained. Since its beginning, Boston Teacher Residency has graduated over 600 teachers, with over 70 percent remaining in the Boston Public Schools through their sixth year. This compares with a 51 percent retention rate among graduates from traditional university preparation programs.[53]

The Boston Teacher Residency is a partnership between the Boston Public Schools (BPS) and the Boston Plan for Excellence (BPE), a local education fund that collaborates closely with BPS on the projects it finances. Through this partnership structure, BPE houses the residency programs and shares program costs and decision-making with BPS. BTR is partnered with UMass Boston which provides accreditation for courses towards residents’ Master’s degree. However, all courses are designed and taught by faculty of BTR. This unique oversight gives BTR considerable latitude in hiring instructors and developing and refining course content.

What makes the arrangement between the Boston Teacher Residency and UMass Boston exceptional and unique is the flexibility allotted to BTR to define the curriculum, evaluate how well it is aligned with the needs in schools and then make necessary adjustments.

In 2012, an independent academic review of the Boston Teacher Residency shed light on how the program has impacted both the pipeline of teachers in Boston Public Schools, as well as student achievement. The researchers found that the Residency program was able to attract a much more racially diverse pool of graduates than the first year BPS teaching cohort as a whole. And the positive impact on the teaching pipeline was clear: BTR grads were much more likely to teach in STEM fields, and to remain teaching through their fifth year. In terms of impact on student outcomes, however, the results are less clear. While BTR teachers were not more effective in raising student test scores in math or ELA than other first year teachers, by their fifth year teaching, BTR graduates outperform other veteran teachers in math outcomes.[54]

Denver

The Denver Teacher Residency (DTR) program has been uniquely focused on investing in and transforming the human capital within Denver’s public school system. The program began ten years ago, shortly after the teachers union ratified a plan to offer teachers a pay differential based on a school’s location or a teacher’s specific role within a school, as well as performance-based compensation for teachers. This paved the way for the district to recognize excellent teacher quality as being fundamental to school improvement efforts, and Denver Public Schools began to seek opportunities to invest in and cultivate a stronger pipeline of talented teaching professionals.

The result became the Denver Teacher Residency, a pilot program embedded in the school district, and implemented in partnership with the University of Denver Morgridge College of Education. The DTR was never sufficiently large to meet all of the district’s hiring needs; at its peak it graduated about 65 teachers each year, compared with annual district hiring of over 900 teachers. But the valuable lessons learned over the past decade have caused the district to now prioritize residential teacher training for a majority of its teachers. The pilot program in Denver is now transitioning as the district movesto bring the successes of the residency program to scale.

From the beginning, DTR sought to make strategic investments in the people who work most closely with students and are the most influential in improving student outcomes: teachers. Many districts often overlook the importance of developing human capital in favor of other resources, such as curriculum or standards-aligned metrics. Instead, Denver Public Schools chose to prioritize developing the capacity of the teaching workforce to provide excellent instruction in all school populations, and to hone school leaders who are able to create school communities that foster excellent instruction. As a result, the system created exceptional learning environments and built pathways both for new teachers, as well as training and professional development of teacher mentors.

A recent report that summarized some of the successes of the program:

“Over time, DTR became so much more than a hiring pipeline as it worked to shift school cultures, grow teacher leaders by elevating high-performing staff into pre-service mentors, and create rich and collaborative teaching and learning environments.”[55]

Denver Public Schools has indicated that it is now seeking ways to scale the program in such a way that the majority of new teachers entering DPS will have completed training in a residency program. This vision will begin, as the original residency did, with partnerships with institutions of higher education – in this case, with eleven colleges and teacher preparation programs. Building on the strong foundation of the DTR pilot, Denver is leading the way in building a strong and diverse pipeline of highly qualified, equity-minded teachers across all of Denver Public Schools.

Pilots in New York City

Several smaller teacher residency pilots already exist in New York City and offer a glimpse of the potential for institutional partners that exist among the City’s rich higher education resources. These programs all feature similar components including paid living expenses for residents, pairing residents with a mentor teacher, and providing a full year of experience working in a New York City public school classroom. However, existing programs do not come near to producing the number of teachers the City needs to fill classrooms each year, necessitating ongoing reliance on the Teaching Fellows. One example of a successful residency is detailed below, but it should be noted that the City has been exploring several alternative pathways to teaching that offer more robust in-classroom opportunities.

New Visions for Public Schools Urban Teacher Residency

In 2008, New York City-based education non-profit New Visions for Public Schools launched an innovative residency program designed with the intent to ensure teachers received an immersive clinical experience during their training. The program design emphasized giving teacher candidates in-classroom experience where they would be exposed to a range of student abilities, and given the tools, mentorship, and coaching to practice making decisions about appropriate academic supports and interventions.

The Urban Teacher Residency (UTR) began as a partnership between CUNY Hunter College, New Visions, and the City’s Department of Education. It has since expanded and now runs a similar but separate program in partnership with CUNY Queens College. As of 2018, the UTR has graduated over 250 high school teachers with a focus in special education, teaching English to speakers of other languages, math, science or English. In a highly structured two-year program, participants earn their Masters of Education from Hunter or Queens College, and use a curriculum developed in collaboration with professionals from New Visions. In the first year of the program, participants are paired with a mentor teacher and spend a full year working as a resident teacher in a high-need high school. Participants enrolled through Hunter College are placed in one of New Visions’ charter network high schools while Queens College participants are placed in a New York City district high school.[56]

District high schools that serve as host sites for residents are carefully selected based on several characteristics. Participating schools must receive Title I funding, to ensure residents are trained in an environment where student poverty is common. In addition, schools must not screen students as part of the admission process, to ensure a broad spectrum of skills and abilities are represented in the student population. Participating schools must also have enough well-developed functions of teacher collaboration in place – such as teacher team meetings, or collaborative student evaluation sessions – to expose residents to a range of possibilities within teaching. Importantly, host schools must be able to commit to paying the resident’s stipend during their first year. This allocation of $25,000 comes out of the principal’s school budget.

During the year of residency, residents have numerous opportunities to hone their instructional practice in the classroom, under the direction of the lead classroom teacher who serves as a mentor. Residents co-teach at least one class with the mentor teacher each day, and teach one class as the lead teacher, with support and feedback from the mentor. Mentor teachers are carefully selected and given additional compensation to reflect the new leadership responsibilities they’ve assumed. For the resident, tuition at Queens College is deferred until completing the program, at which time candidates repay about half the cost of the Master’s degree to NYC DOE through paycheck reductions spread over two years. Following the year of residency, teacher candidates are hired as full-time teachers in a high-need school in New York City while completing the necessary coursework towards their degree.

A recent independent evaluation of the Urban Teacher Residency has confirmed the program’s positive impact in three key areas.[57] First, the evaluation found that students of UTR-trained teachers performed as well or better than peers taught by teachers trained in other programs. Positive impacts were even more pronounced in math and science, and among students of color. Second, UTR teachers had higher retention in Title I schools with large concentration of students of color where teacher turnover tends to be the highest. Approximately 15 percent of UTR-trained teachers left teaching within three years, compared with 34 percent of other new teachers working in comparable Title I schools in New York City. Third, the evaluation found that the Urban Teacher Residency was highly effective in recruiting, mentoring and coaching teachers of color, with close to 60 percent of the most recent graduates being teachers of color.

Teaching Residents at Teachers College (TR@TC)

Another successful collaboration between the City and higher education can be seen at Columbia University’s Teachers College. Teaching Residents at Teachers College (TR@TC) is a robust teaching residency that prepares participants through a year-long, paid residency. As of 2017, the program reported retention rates of 94 percent among program graduates.[58] Residents are paired with mentor teachers as well as a residency supervisor, who consistently observes the resident and offers guidance and reflection on progress. Mentors are provided a stipend and considerable scholarship to attend Columbia’s Teachers College as well as health insurance assistance. Upon completion, residents make a commitment to teach in high-need schools in New York City for a minimum of three years.

American Museum of Natural History

This unique residency program is housed within the Richard Gilder Graduate School at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), and awards program completers a Master of Arts in Teaching degree, with specialization in grades 7-12 earth science. It prepares science teachers to work in four schools in New York City and Yonkers. During the 10-month classroom residency, participants are paired with a mentor teacher in addition to regular work alongside teachers of multi-lingual learners and students with disabilities.[59]

The above models offer an intriguing glimpse of what is possible for scaling teacher residencies in New York City. By focusing on training sites that represent a complete picture of the opportunities and challenges of teaching in urban schools, along with establishing support and guidance for developing mentor teachers, each model ensures that participants gain valuable experience crucial for effective teachers. These programs successfully reduce financial barriers to participating, by offering reduced tuition, as well as stipends for living expenses during the year of residency. And while each program is both highly selective and rigorous, teacher candidates are given significant support throughout the program, and into their teaching career.

International Best Practices

Among nations that score highest on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), an international educational assessment of 15 year olds, many of the leading nations share a strong teaching profession. A recent comparative analysis of the top performing systems found that educational districts in Australia, Canada, Finland, and Singapore share several practices that are typically common to teacher residencies. For example, these systems all feature teacher training programs that are highly selective and very rigorous, requiring in-depth clinical training in the classroom. Teacher preparation in these nations is partially or fully subsidized, as is professional development throughout a teacher’s career. The collaborative nature of teaching is cultivated in high-performing systems: rather than novice teachers struggling in isolation, schedules allow teachers adequate time to plan, collaborate, and conduct inquiries into their teaching practice.[60]

The strong performance of students in these nations is clear. But the strength of the teaching profession is equally impressive. For example, fewer than three percent of teachers in Singapore resign each year, due largely to policies designed to elevate the teaching profession and support teachers’ success, both as they prepare for the classroom and throughout their careers.[61]

Recommendation: Time to Expand Teacher Residencies in New York City

To better prepare early career teachers for the profession and to reduce turnover, New York City needs to invest in a large-scale, paid, year-long teacher residency program. There is clear evidence that residencies significantly improve teacher retention.

New York City’s students would directly benefit from teachers who were better prepared at the outset of their careers; New York City schools would benefit from the continuity of a stable teaching staff and the additional capacity from teaching residents to take on instructional functions such as substitute teaching or tutoring; and the City would benefit from long-term cost savings resulting from lower turnover. Absent a major shift in state and federal education policy that would require year-long clinical teacher preparation prior to certification, it is necessary for the City to direct resources to make experiential learning a standard for all teachers who enter the profession through city-funded alternative certification pathways. As the nation’s largest school district, New York City could direct resources to fund resident teacher positions for as many teachers as are currently participating in the Teaching Fellows alternative certification program. By closely aligning a residency to meet the district’s hiring and school improvement needs, the City has the potential to improve the quality and retention of its workforce, reduce class-sizes in schools where residents are placed, and build ladders of opportunity for current teachers to become mentors in resident classrooms.

Critical elements of teacher residency programs: incentivize strong, experiential training

Residency programs in other cities vary in programmatic design, but there are certain key features common to all successful residency programs.

Residents work under and alongside a single, accomplished mentor teacher in a high-functioning classroom. Successful residency programs ensure that each resident is paired with an expert teacher, with whom they collaborate and co-teach, and who serves as a mentor teacher, offering feedback and evaluation. This relationship has clear benefits for the resident, who gains in-depth classroom experience along with guidance in developing their teaching practice. The mentor teacher also benefits from increased salary as well as opportunities to practice advanced leadership skills and the presence of a committed and qualified co-teacher in their classroom.

Residencies are year-long commitments for teacher candidates. Being immersed in the work and life of a classroom for a full school year provides teacher candidates opportunities to experience a full curriculum cycle and how a classroom and individual students evolve through various transitions that take place over time. The first month of school, weeks leading up to state exams, or transitions after extended holiday breaks are all times when students may exhibit particular academic or behavioral needs and a resident teacher benefits from observing and learning from the full academic cycle of these transitions. Likewise, schools benefit from yearlong placements because residents, in their role as co-teachers, effectively reduce class sizes and contribute to larger school improvement goals by serving as additional instructional staff.

Residency programs provide a stipend to cover candidates’ living expenses during the residency year. Not all residential programs are able to offer living stipends to residents in addition to reduced or free tuition. However, it is considered a global best practice to provide a modest living stipend for the residency year. It ensures that while residents are focused on developing the skills they will need as teachers, they are not forced to take on additional student debt or juggle secondary work schedules which compromise the quality of their residential experience. A clear parallel can be found in the medical profession, where government funds support stipends for medical students during their residency training as well as subsidies for medical teaching hospitals. A stable workforce of well-trained physicians is considered a public necessity, and is supported through public funds. Similarly, ensuring consistently well-prepared teachers is essential for a strong, equitable education system.

Residency programs reflect a collaboration between a school district and an institution of higher education, with shared responsibilities of program development, oversight and evaluation, and an emphasis on quality. The goal of the partnership is always to meet the district’s particular staffing and school improvement needs. An open and collaborative partnership encourages deeper reciprocity between education theory and the daily practice of teaching through teacher preparation curricula that is directly related to residents’ clinical classroom experience. A well-aligned collaboration between the district and teacher training institutions – with regular feedback channels to inform both curriculum and instructional practice – helps ensure that new teachers are ready on “day one” to contribute to goals for educational quality and subject area needs set by the district.

Furthermore, successful residency partnerships must intentionally focus on quality and continuous improvement from the beginning. Ideally, each school that hosts a cohort of residents would spend a year in a partnership development phase with the approved teacher preparation provider. This time would be spent developing plans for recruiting a diverse pipeline of teachers, developing a sequence of coursework aligned with residents’ daily classroom experience, and establishing a feedback loop to ensure district school improvement needs are a shared goal. Additionally, each school where residents work would need to recruit and prepare mentor teachers. These mentor teachers require skill-building to ensure they are familiar with adult learning patterns, and have the necessary tools to provide instructional coaching to residents and integrate them into the daily routines of their classrooms. The focus on quality requires time and investment from participating schools, and accordingly requires financial compensation for dedicated staff.

What an investment in teacher residencies in NYC would look like

There are currently no examples of implementing teacher residencies on a large scale in the U.S. To phase in a program in New York City that could reliably train as many as 1,000 teachers hired in City schools each year would require some upfront costs.[62] This investment would be partially offset by the long-term cost savings expected from lower teacher turnover among early career teachers. Currently, taxpayers subsidize the costs of placing under-prepared and under-supported teachers in classrooms where it is expected that a large percent will leave the profession within a few years. A more strategic investment in high-quality teacher preparation will strengthen the pipeline of teachers, ensure more equitable access to strong teachers across schools, and reduce costs associated with high teacher turnover in the long run.

Several variables would affect the true cost of launching a large-scale teacher residency program in New York City. Key factors to consider include whether the full cost of tuition would be covered and the amount of stipend offered to both residents and mentor teachers. In addition, programmatic costs need to be factored in, including: school-based staff to liaise between residents, the university partner, and the schools where residents are placed; professional development and coaching for mentors; and program evaluation.

Residencies also offer potential for some cost offsetting in schools where residents are placed. Prepared to Teach, a project within Bank Street College of Education that supports school districts in implementing teacher residencies, has outlined various cost models for how to redistribute some funding in order to support teacher residencies.[63] As an example, with careful program design, residents could take on additional instructional tasks in schools, such as substitute teaching (especially within their assigned classroom), or afterschool tutoring. While contractual issues that would need to be addressed, by assigning these functions to residents, schools may decrease expenses while also giving residents valuable opportunities to hone their teaching skills.

Transforming NYC’s alternative teacher preparation programs

Organizations like Prepared to Teach that support the work of scaling teacher residencies in other cities emphasize the importance of phasing in the residency program while phasing out quick-entry programs. This is done so that immediate hiring needs continue to be met, while simultaneously bringing cohorts of residency-trained teachers into the system. As these teachers enter the workforce, the school district can anticipate improved retention rates and associated cost savings. These cost saving can then be reallocated back into the residency program, improving its financial sustainability.[64]

To begin to introduce a large-scale teacher residency program, the City could adopt a five-year phase-in time frame. In the first year the City would continue to recruit enough teachers to fill shortage areas through the NYC Teaching Fellows. At the same time, the City would invest in 250 additional recruits into a residency-style program. Rather than being placed directly into the classroom as current Teaching Fellows are, these candidates would be enrolled into a year-long co-teaching residency. Priority for the residency would be given to candidates seeking certification in high-need subject areas, including TESOL, Math, Science, or other specific teacher shortage areas.

In the second year of the phase-in, the first cohort of 250 residency-trained teachers would be eligible for hiring in hard-to-staff classrooms, and the number of recruits in the original Teaching Fellows program could be reduced by 250. By incrementally increasing the number of participants in the residency program each year and decreasing the number of students in the Teaching Fellows program, the program budgets for each would begin to balance. Assuming teacher retention would increase among those trained in a high-quality residency program, as more residency-trained teachers enter classrooms, eventually fewer new hires would be needed each year.

A sample phase-in schedule plan could resemble the following:

5 Year Phase-in of Teacher Residencies Accommodates Immediate Staffing Needs

-

Year

1- 250 residents

- 1000 NYC Teaching Fellows

-

Year

2- 750 residents

- 500 NYC Teaching Fellows

- Year 2 cohorts (500 residents) begins working in schools

-

Year

3- 750 residents

- 500 NYC Teaching Fellows

- Year 2 cohorts (500 residents) begins working in schools

-

Year

4- 1000 residents

- 250 NYC Teaching Fellows

- Year 3 cohort (750 residents) begins working in schools

-

Year

5- 1000 residents

- Teaching Fellows discontinued

- Year 4 cohort (1000 residents) begins working in schools

- Cost savings from increased teacher retention

With increased retention, the need to recruit, hire and train new teachers will also decrease, and the savings can be funneled back into the residency program.

Assuming the five-year attrition rate would be reduced by half to about 20 percent for teachers in the residency program, annual savings directly from increased retention would eventually amount to about $4 million each year.[65]

In addition, repurposed resources and staffing structures within DOE’s allocation to schools can ensure upfront funding is available to support a teacher residency program. Some funding currently directed to professional development could be reallocated, for example. In addition, costs for some academic functions in schools – such as substitute teaching, tutoring, or afterschool – could possibly be reduced if resident teachers take on these functions as part of their year of residency.[66]

This proposal assumes that much of the program architecture within the New York City Teaching Fellows program could be efficiently expanded or repurposed to accommodate the first phase of a teaching residency program, rather than duplicating costs with a separate administrative office. As the teaching residency grows, it would gradually replace the current Teaching Fellows program. While some additional centrally-located program staff may be needed to support program design and coordination, it is assumed that administrative costs would generally equal the current budget of the Teaching Fellows program.

To scale this model effectively, it is important to identify and partner with qualified institutions of higher education (IHE). Higher education partners, willing to commit to shifting their teacher preparation programs to school-based residency programs, can help DOE identify the principals and partner school sites that would most benefit from housing an annual cohort of teacher residents. Close collaboration with IHE partners in curriculum and professional development planning ensures the program design is directly aligned with DOE’s instructional and school improvement needs. To support this partnership, DOE should consider convening IHE partners early in the program design phase to clarify roles and responsibilities, define a shared vocabulary for instructional leaders, and establish expectations for residents’ performance.

Certainly some additional costs would be involved that may not be currently factored into costs of the Teaching Fellows program. Some examples include:

- Program expenses. Particularly in the development phases, the City would need to invest in program costs such as curriculum development, program evaluation, and recruitment of both residents and mentors.

- Partnership development funding. While much of the program development would be managed centrally, some additional work may fall on schools and would require compensation. These costs may include ensuring coursework is fully integrated into residents’ daily classroom experience, and that additional instructional opportunities are available to residents, such as substitute teaching, mentoring, or leading afterschool activities. Conservatively, these costs would be up to $75,000 annually per school hosting a cohort of ten residents to cover the salary of a dedicated program coordinator at each site. To accommodate 1,000 residents when fully scaled, this proposal would need to provide funding to 100 schools at an annual cost of $7.5 million

- Resident costs. While the Teaching Fellows program already covers the cost of tuition for program participants, a residency would provide an additional living stipend of $30,000. For 1,000 residents, this would add about $30 million annually in program costs in addition to current tuition costs.

- Funding for mentor teacher pay differential and professional development. To compensate mentor teachers for the additional leadership tasks they assume when hosting a resident in their classroom, additional pay is necessary. A specific sequence of professional development is also needed, particularly for mentor teachers’ first year working in the program. Assuming approximately $7,500 per mentor, this proposal would require $7.5 million annually.[67]

It is important to remember that these investments are not simply increased costs. Rather, it is expected that investing in high-quality teacher preparation will yield significant cost savings as teacher retention increases and instructional quality improves. These long-term impacts go beyond simply improving the pipeline of effective teachers in the City, and represent a larger investment in education, in communities, and building a more sustainable City for all New Yorkers.

Acknowledgements

Comptroller Scott M. Stringer thanks Elizabeth Bird, Senior Policy Analyst and the lead author of this report. The Comptroller also extends his thanks to David Saltonstall, Assistant Comptroller for Policy; Tammy Gamerman, Director of Budget Research; Preston Niblack, Deputy Comptroller for Budget; Eng Kai Tan, Budget Bureau Chief; Archer Hutchinson, Web Developer and Graphic Designer; and Susan Watts, Director of Visual Content.

Comptroller Stringer would also like to recognize the contributions made by Alaina Gilligo, First Deputy Comptroller; Sascha Owen, Chief of Staff; Matthew Rubin, Deputy Chief of Staff; Shanifah Rieara, Assistant Comptroller for Public Affairs; Tian Weinberg, Senior Press Officer; Tyrone Stevens, Director of Communications; Hazel Crampton-Hays, Press Secretary; Dylan Hewitt, Director of Intergovernmental Relations; Alyson Silkowski, Associate Policy Director; Adam Forman, Chief Data and Policy Officer; and Nichols Silbersack, Deputy Policy Director.

Comptroller Stringer is grateful to the external reviewers who read earlier drafts of the report and whose incisive and thoughtful feedback continues to refine and ground this work.

Endnotes

[1] Ingersoll, R., & Smith, T. M. (2004). Do Teacher Induction and Mentoring Matter? Retrieved from: https://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/134

[2] New York City turnover rates are calculated using data from New York State Education Department, 2017-18 Report Card Database. Accessed from: https://data.nysed.gov/essa.php?year=2018&state=yes.

[3] Guha, R., Hyler, M.E., and Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). The Teacher Residency: An Innovative Model for Preparing Teachers. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Accessed from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/Teacher_Residency_Innovative_Model_Preparing_Teachers_REPORT.pdf

[4] New York City New Hire and Separation details from October 1 through September 30. Data as reported in the Citywide Human Resource Management System. The Comptroller’s Office analysis of payroll data focused on four titles of pedagogues, and did not include other school or district staff such as guidance counselors, psychologists, school administrative or support staff, etc. Data may be retroactively updated. Comparison data on teachers in Cleveland from Ohio School Report Cards, District Details.

[5] New York State Education Department, 2017-18 Report Card Database. The analysis by the Comptroller’s Office of NYC staff data used averages reported by school district.

[6] FY 19 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report, Accessed from: https://www1.nyc.gov/site/operations/performance/mmr.page.

[7] U.S. Department of Education, Teacher Shortage Areas, New York City, 2018-19. Accessed from: https://tsa.ed.gov/#/reports.

[8] New York City Independent Budget Office, May 2014: Demographics and Work Experience: A Statistical Portrait of New York City’s Public School Teachers. Accessed from: https://ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/2014teacherdemographics.html

[9] Rockman, et al. New Visions for Public Schools – Hunter College Urban Teacher Residency Project. A Different, More Durable Model. September 2018. Accessed from: http://rockman.com/docs/downloads/TQPXCombinedReport_10.23.18-1.pdf.