Executive Summary

New York City is the artistic and creative epicenter of the country and, in many respects, the world. It is where the cultural treasures of our great museums meet the ad firms of Madison Avenue, where high fashion struts among the sound stages of Astoria, where Broadway theatres can be found a stone’s throw from some of the finest architectural, educational and publishing institutions across the globe. But the “creative economy” is more than just an agglomeration of cultural pursuits: It is a defining economic sector for New York City – on par with finance, real estate or law – with its own policy challenges and pressures deserving of rigorous review and analysis.

This report, by New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, offers a comprehensive, up-to-date look at the city’s ever-changing creative economy. The creative sector, as we define it in this report, includes any industry the primary output of which is creative or cultural – from museums and art galleries, to film and television production, theater and dance companies, fashion, publishing, advertising, and more. Today, New York City’s creative sector directly employs over 293,000 people, paying $30.4 billion in wages. It is greater than the sum of its parts, providing tens of thousands of jobs not just for artists and actors, but for museum administrators, sewing machine operators, sound technicians, and the myriad other jobs that make up the creative economy, not to mention the hotel and restaurant workers, suppliers, construction workers and others whose jobs rely in some measure on the sector. Altogether, the sector is responsible for some $110 billion in total economic activity – or one in every eight dollars churning through the City’s economy.

293,000

People Employed, 2017

$30.4 B

Total Wages Paid, 2017

$110 B

Total Economic Activity, 2017

Findings of this report include:

- The creative sector accounts for 13 percent of the city’s total economic output. In total, one out of every eight dollars of economic activity in the city – $110 billion in 2017 – can be traced directly or indirectly to the sector.

- Creative industries are increasingly concentrated in New York City. An astonishing 12 percent of all creative industry jobs in the United States are located within the five boroughs – compared to less than 3 percent of all jobs nationally. Certain industries are especially highly concentrated in New York City, with one out of every five fashion design jobs in the United States (21.2 percent) now located in the city, a level of concentration that is also true for advertising (22.1 percent) and for publishing (19.3 percent).

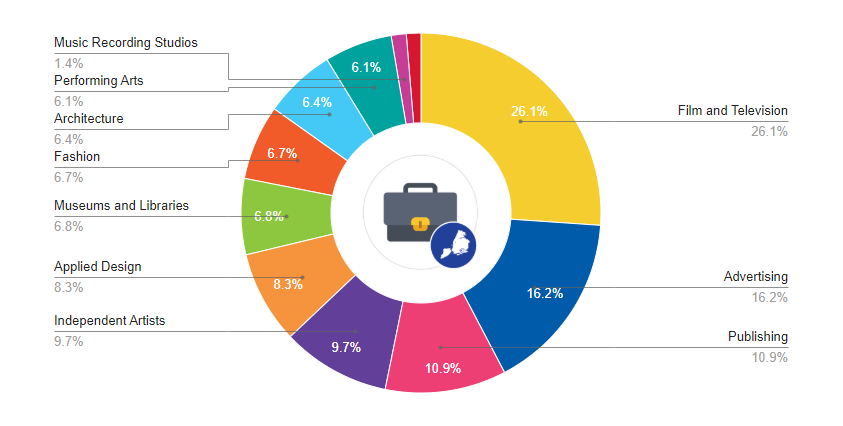

NYC Creative Sector Employment, 2017

- The creative economy is increasingly a part of the knowledge economy. The fashion industry exemplifies the dynamics: While employment in fashion production plummeted 43 percent – by far the steepest decline of any industry in the city – the fashion design sector in the city boomed between 2008 and 2017 – up nearly 27 percent, a rise second only to advertising and film & television.

The report also takes a close look at the sector’s workforce. Among the significant findings of this report are:

- Volatile employment situations for some creative workers and high rates of self-employment contribute to economic insecurity. About one third of New York City-based actors did not have active employment in 2017, as did 21 percent of musicians. Part-time work is also prevalent: More than half of actors and nearly half of musicians and dancers and entertainers reported working part time. Moreover, 36 percent of New York City-based creative workers were self-employed in 2017, compared to just 10 percent of the City’s overall workforce. These workers lack access to benefits and protections available to employees, such as affordable health insurance and unemployment insurance.

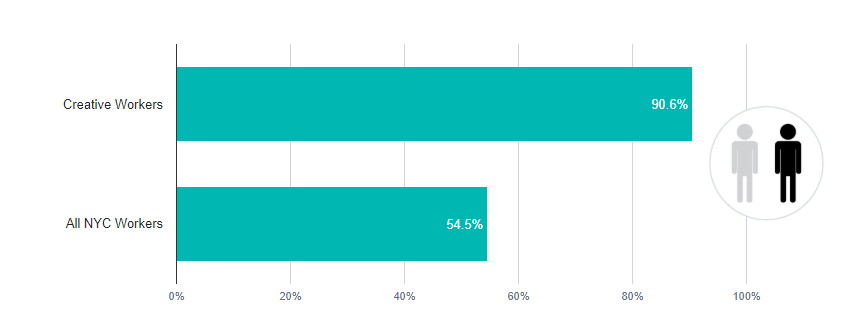

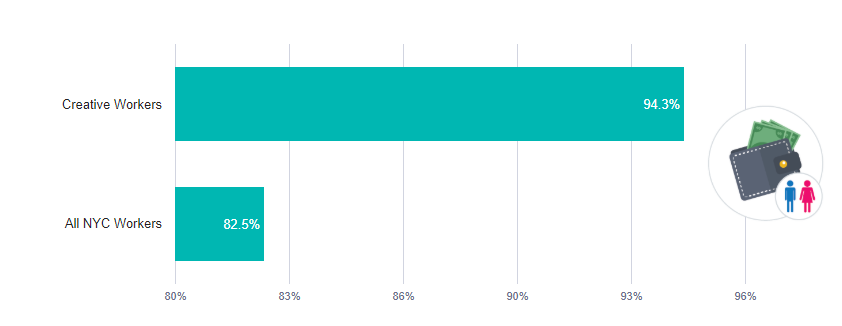

- While persons of color represent 68 percent of the city’s total population, they account for only 34 percent of the workers in all creative occupations. But non-white creative workers overall earn 91 cents on the dollar compared to their white counterparts – a much better ratio than the citywide average for all workers of just 54.5 cents on the dollar. Female creative workers, who comprise 49% of the creative workforce – close to the citywide ratio – earn 94 cents on the dollar compared to their male counterparts – also considerably better than the citywide ratio of 82.5 cents.

- Finding affordable places to live and work for creative sector workers has become an ever-steeper challenge – leading to profound migrations across the five boroughs in recent years. While Manhattan neighborhoods south of 96th Street have lost residents in creative occupations, other, more affordable areas of the city have gained, with the steepest increases in Brooklyn’s Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant; and Washington Heights, Inwood and Marble Hill in Upper Manhattan.

Change in Residents in Creative Occupations by Neighborhood, 2008-2017

Finally, this report looks at the robust network of government and other supports aimed at promoting creative industries and workers, and expanding access to the arts and culture.

- The New York City Department of Cultural Affairs (DCLA) is the largest cultural grant-making agency in the country, providing $181 million in support to cultural organizations in New York City in City fiscal year (FY) 2018.

- The Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment supports film and television production, as well as other supports to the film, TV, theater, music, advertising, publishing, and digital content sectors

- The State and City’s film and television tax credits led to a boom in production in the five boroughs.

- Numerous other programs and initiatives provide piecemeal support to other components of the sector and promote creative sector careers.

Nevertheless, more can and should be done to strengthen and sustain the city’s sprawling yet often fragile cultural eco-system. To fortify and grow the creative sector and expand access to New Yorkers of all incomes and ethnicities, the City must first and foremost treat the sector as the economic engine and resource that it is, and at the same time tackle the challenge of making the City more secure and affordable for creative workers. If New York City is allowed to become a place with limited economic footholds for artists, writers, and others who yearn to stake their claim, it will cease to be a beacon for creative types across the globe and the city will pay a steep price – in both economic activity and the cultural riches that have long defined the five boroughs. Supporting the creative economy more broadly will require both targeted investments in specific industries, as well as broad based investments aimed at making New York City a more affordable place to live, work and create.

Among the recommendations outlined further in this report are the following three areas of focus:

1. Value and Promote the Creative Sector

Given the importance of the creative sector to the City’s economy and to the lives of its residents, the City should adopt a more pro-active and cohesive approach to promoting the sector:

- Strengthen the City’s role in sustaining the creative sector: The City should establish an office and interagency task force under the Deputy Mayor for Economic Development with the role of supporting and promoting the creative sector. The office would oversee and coordinate the work of the several City agencies and entities (DCLA, EDC, MOME, NYC & Company) that currently provide support to one or more industries within the creative sector.

- Create and promote Cultural Districts: City and/or State support and sponsorship to replicate the success of existing cultural districts to drive visitors, develop the local economy, and connect local communities to their cultural offerings.

- Improve the capital funding process for cultural nonprofits: Streamline the cumbersome and costly process for providing capital funds for equipment and facilities to non-profit arts and cultural organizations, which currently hinders the City’s efforts to support small organizations in particular.

- Establish Creative Economy Zones. Creative Economy Zones would be zoned to promote development of space for creative industries.

- Foster creative incubators: Explore partnerships with industry to establish creative sector incubators where early-career creative professionals and start-ups can access low-cost space and equipment.

- Utilize existing public space. Use space in DOE schools, which have a wide array of artist facilities and space, to provide low-cost space to non-profit cultural organizations and artists.

2. Deepen Connections to Local Communities

Enhancing diversity in the creative sector requires starting early to provide opportunity for students and youth. To provide the benefits of arts education, expand access to the City’s cultural offerings, and open pathways for all New Yorkers to creative careers, the City should undertake the following steps:

- Increase arts/creative education in schools: Following a 2014 report by the Comptroller, DOE increased funding for arts education in schools. But the City still falls short of New York State requirements for arts education. The City should ensure that every New York City school has access to a full-time arts educator, and work with local arts organizations as resources for public school arts education.

- Promote creative sector careers: The City should partner with industry and the non-profit sector to create accessible training, apprenticeship, and other work-based learning programs in the creative industries.

- Bolster support for cultural programming for at-risk and underserved youth: Arts and culture programming and education offers a safe space to learn new skills, express emotion, and take risks. At-risk and underserved youth in particular should have the opportunity provided by arts programming, which can also help serve as a career pathway.

3. Support the Creative Workforce

Many members of the creative workforce face the numerous challenges associated with part-time and “gig” work. The following measures would help them and other similarly-situated workers in other sectors:

- Support state legislation to combat wage theft. New York State should enact protections for independent workers that build on the City’s 2017 “Freelance Isn’t Free Act” which guarantees freelancers the right to a written contract, full and timely payment, and protection from retaliation.

- Supporting access to quality, affordable benefits. The City or State should partner with private organizations to create a welfare benefits fund for creative workers, and enable withholding to fund benefits.

- Enhance economic security of the self-employed. Using a welfare benefits fund as an employer under New York State labor law, independent workers could be recategorized as employees to give them access to unemployment insurance and workers compensation.

- Create new affordable housing and workspaces. A more ambitious effort to create affordable living and working space for creative professionals is needed in the face of the rising affordability crisis.

New York City’s Creative Economy

The Sector at a Glance

New York City’s creative economy is world-renowned and core to the city’s global identity and brand. From the theaters of Broadway to the advertising firms of Madison Avenue, from the New York City Ballet to the performances on the runway at Fashion Week, the Metropolitan Museum to the Bronx Zoo, New York is synonymous with art, culture, and creativity.

More than just a symbol, the creative sector is a major part of, and contributor to, New York City’s economy. It provided employment to some 293,000 people in 2017 and paid $30.4 billion in total wages. Some 15,000 firms and institutions provided employment to over 231,000 people in New York City’s creative sector in 2017. In addition, over 62,000 workers in the sector are self-employed – a figure which has grown at nearly twice the rate of growth of those employed in a business or non-profit organization. Altogether, New York City’s creative sector represents about 5.4 percent of private employment in the City, and 6.7 percent of wages paid in the City.

Table 1: Overview of New York City’s Creative Sector, 2008 and 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Bureau of Labor Statistics and Census Bureau American Community Survey.

But those figures understate its total economic impact. Workers in other industries — both specialized, such as the crafts and trades that serve theaters and film production companies, and other more general, such as hospitality, legal services, and transportation — provide goods and services to the arts and culture industries and would not exist in the same numbers without them. The spending of these firms and their employees induces further economic activity. Including the workers directly employed in the creative industries, the suppliers of goods and services to those industries, and the induced economic activity, total output of the industry was roughly $110 billion in 2017 – nearly 13 percent of total City output, or nearly one in every eight dollars.[1]

The sector, as we define it for purposes of this report, is varied, and includes advertising agencies, design and architecture firms, the fashion industry, film and television production, art dealers, galleries and auction houses, sound recording, museums and libraries, theater and the performing arts, and book and periodical publishing.[2] (Profiles of each industry can be found in the Appendix.)

As shown in Chart 1, the largest industry was film and television, which includes motion pictures production, television broadcasting, and cable services, and employed over 76,500 people in 2017. The next largest industries were advertising and publishing, which employed approximately 47,600 and 31,900 people, respectively.

Chart 1: NYC Creative Sector Employment, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Bureau of Labor Statistics and Census Bureau American Community Survey.

While many workers in these sectors hold creative occupations – actors and editors, musicians and designers, architects and photographers – overall roughly 60 percent of workers in the sector hold other jobs – from grant writers to IT administrators, sales agents to security guards, theater ushers to human resources managers. In addition, thousands of artists, writers and performers work independently – members of the “gig economy” long before the term was invented.

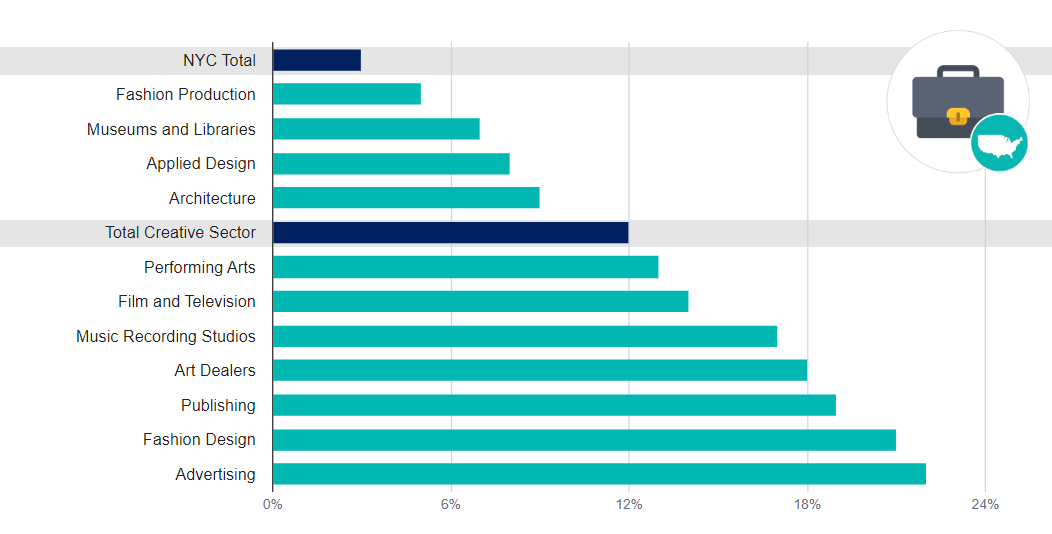

The sector as a whole, and to one degree or another, all of its industries, are highly concentrated in New York City, with sectoral shares of national employment well in excess of the City’s overall share of total national employment. New York City employment in the creative sector as a whole is nearly 12 percent of total U.S. employment in the sector; by contrast, total New York City employment in all sectors of the economy is less than 3 percent of total U.S. employment. As shown in Chart 2, some industries are particularly highly concentrated, such as advertising (22.1 percent of U.S. employment); fashion design (21.2 percent), and publishing (19.3 percent) – but even fashion production employment, which has shrunk rapidly over the last few decades, remains higher than average, at 5.4 percent. With a few exceptions, the degree of concentration has only increased in the last decade, from 10.2 percent overall in 2008, to 11.9 percent in 2017.

Chart 2: Creative Sector Shares of National Employment by Industry, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Bureau of Labor Statistics and Census Bureau American Community Survey.

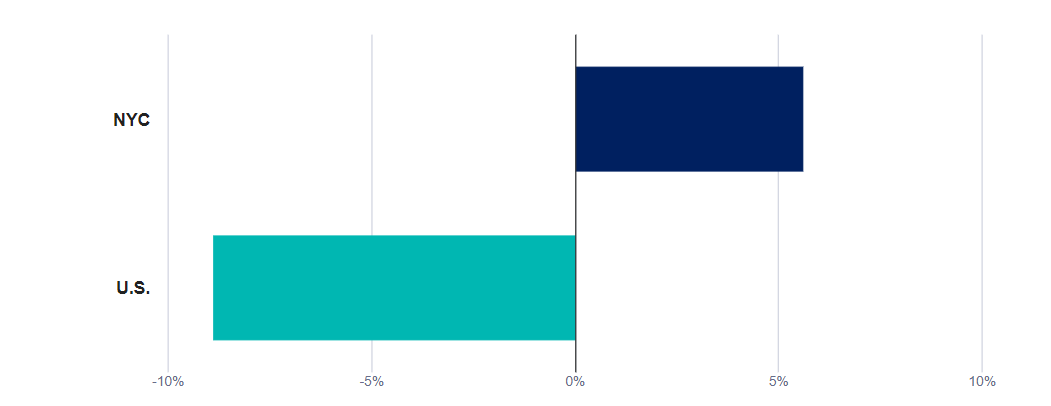

Relative to the record employment growth in the City as a whole over the last decade, employment in the creative sector (excluding self-employment) has lagged somewhat, rising 5.6 percent compared to a 15.6 percent increase in total City jobs. But relative to the U.S. as a whole, where creative sector jobs declined by nearly 9 percent, New York’s creative sector has fared extremely well in the last decade (Chart 3). Job growth was greatest in Brooklyn and, to a lesser degree, Queens.[3]

Chart 3: New York City’s Creative Sector Has Grown

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Bureau of Labor Statistics and Census Bureau American Community Survey.

But growth has not been distributed evenly among creative industries, as seen in Chart 4. While most sectors have seen growth, three of the industries expanded by more than the citywide rate since the recession, while three others have contracted – fashion production, publishing, and music recording.

Chart 4: Percent Change in NYC Creative Employment by Industry, 2008 to 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Bureau of Labor Statistics and Census Bureau American Community Survey.

The $30.4 billion earned by creative sector workers in 2017 was up 23 percent from 2008. Total wage growth in the creative sector was slightly below the rate of growth of wages over all in New York City of 29.3 percent over the same period. Wage growth for creative sector employees was higher (23.6 percent) than for the self-employed (18.5 percent).

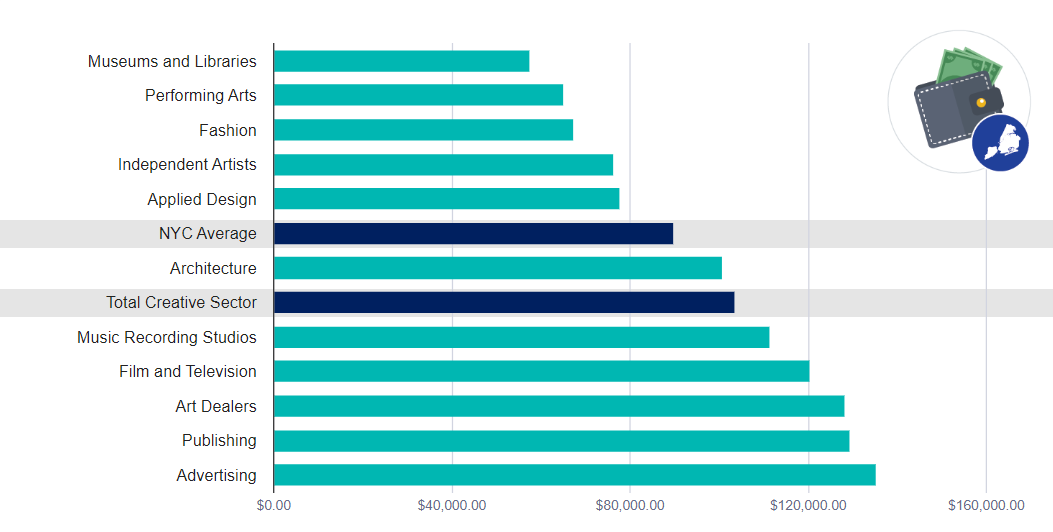

Across all sectors of the creative economy, the average creative sector wage (including the self-employed) increased by 15.2 percent from $89,864 in 2008 to $103,486 in 2017. As shown in Chart 5, average wages vary greatly by industry – from an average of $57,416 in the museums, historical sites, zoos, parks, and libraries sector to over $129,478 in publishing and $135,334 in advertising. Six creative industries have average wages exceeding the city average for all industries of $89,766. Four of these have also experienced job growth since the recession – advertising, architecture, art dealers, and film and television.[4]

Chart 5: NYC Creative Economy Average Wages, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Bureau of Labor Statistics and Census Bureau American Community Survey.

NOTE: Includes both employed and self-employed. Salaries and wages only, excluding benefits.

The Creative Workforce

Nearly 228,000 New Yorkers are employed in a creative occupation, as detailed in Table 2 below. This figure includes both those who work in one of the creative industries discussed above, as well as the tens of thousands of other creative workers who are employed in other sectors – such as the graphic designer at a tech firm, or the editor working for a trade association, or the architect at a real estate development firm.

While creative workers are often relatively high earners – especially amongst those employed in private-sector firms – many creative workers are self-employed or lack steady employment and earn relatively low wages from their chosen profession. This is even more true for minorities and women, who are both underrepresented in creative professions, and generally less well-paid. Coupled with often high student debt loads and the increasing difficulty of finding affordable housing, New York City is becoming a challenging place to live for many workers in the sector.

Employment

From 2008 to 2017, the resident creative workforce grew 12.8 percent, outpacing growth of 8.2 percent in the total resident workforce. Together these creative workers represent 5.5 percent of the City’s workforce – up slightly as a share from 2008. The largest number – 61,496, or one-quarter of the total – are designers. Editors, writers and authors are the next most numerous at over 48,000.

Table 2: The Creative Workforce in New York City

| Occupation | 2008 | 2017 | Pct. Change |

| Actors | 9,255 | 11,509 | 24.4% |

| Agents | 5,629 | 5,402 | -4.0% |

| Architects | 12,703 | 13,216 | 4.0% |

| Artists | 17,681 | 17,447 | -1.3% |

| Sound Operators and Media Editors | 13,750 | 16,935 | 23.2% |

| Dancers and Entertainers | 5,215 | 5,312 | 1.9% |

| Designers | 52,530 | 61,496 | 17.1% |

| Writers, Authors and Editors | 41,513 | 48,053 | 15.8% |

| Musicians | 12,218 | 14,221 | 16.4% |

| Photographers | 12,185 | 11,709 | -3.9% |

| Producers and Directors | 19,167 | 22,455 | 17.2% |

| Total, Creative Occupations | 201,846 | 227,755 | 12.8% |

| Total, All NYC Occupations | 3,817,552 | 4,131,157 | 8.2% |

| Creative Workers as Percent of Total | 5.3% | 5.5% |

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

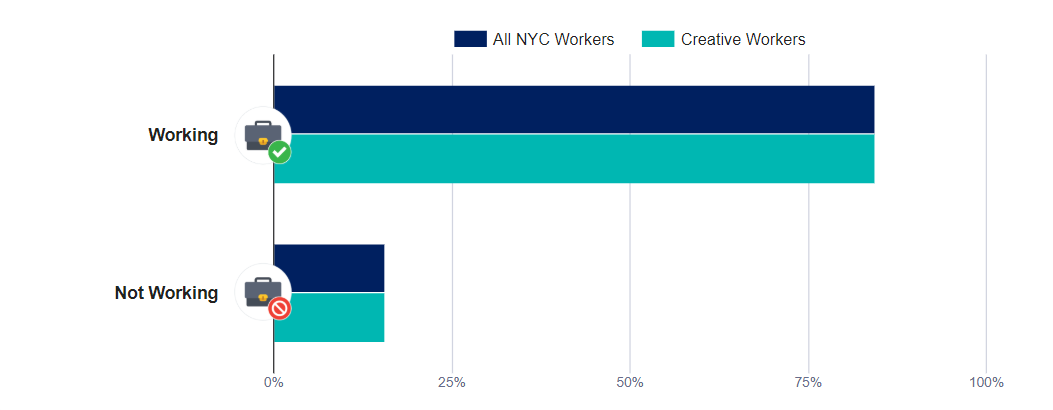

Overall, New Yorkers with creative occupations report comparable levels of active employment to other city residents reporting an occupation. As Chart 6 below illustrates, 84.4 percent of creative workers who live in New York City are working, nearly identical to the citywide average of 84.3 percent for all workers. However, these averages belie challenging labor markets for certain types of creative workers.

Chart 6: Employment Status of New York City Creative Workers vs. All New Yorkers, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

Many creative workers in New York City, such as actors, musicians, and photographers, must navigate volatile employment situations, due to the frequently short-term, “gig” nature of their work. One third of New York City-based actors did not have active employment in 2017, well above the creative workers’ average of 15.6 percent, as seen in Chart 7. Musicians also faced employment challenges with 21 percent indicating that they were not working.

Chart 7: Share of New York City Creative Workers without Active Employment by Occupation, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

Part-time work is also prevalent. Among creative workers, nearly one quarter reported working part time in 2017 (Chart 8). More than half of actors and nearly half of musicians and dancers and entertainers reported working part time. Full-time employment is more common for architects, designers, producers and directors.[5]

Other creative New Yorkers may not be able to support themselves with earnings from creative employment alone. For example, a survey of Off-Off Broadway staff found that only 10 percent made their living exclusively from the theater.[6] About two-thirds of these creative workers reported having a full-time or part-time job outside of their roles in theater productions.

Chart 8: Share of Employed NYC Creative Workers Engaged in Part-time Work, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

Creative workers have also historically exhibited high self-employment rates, and this holds across all occupational categories that comprise the creative workforce, as shown in Chart 9. Overall, 36 percent of New York City-based creative workers were self-employed in 2017, compared to just 10 percent of all New Yorkers. Photographers reported the highest self-employment rate – 71 percent – followed by musicians with a 57 percent self-employment rate. Other occupations are more typically employed by firms, including producers and directors, agents, designers and architects, but all still show high rates of self-employment.

Chart 9: Share of Self-Employed NYC Creative Workers, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

The precarious and volatile employment status of many creative workers also can leave them without access to worker protections and benefits available to regular employees. The self-employed generally have lower rates of health insurance coverage than the employed. Twenty-six percent of self-employed actors, and nearly 17 percent of photographers, dancers and entertainers, lack health insurance. For those with volatile employment and income, the risk of losing health insurance is elevated. Independent and freelance workers also lack the unemployment insurance and worker’s compensation benefits enjoyed by employees.

Diversity

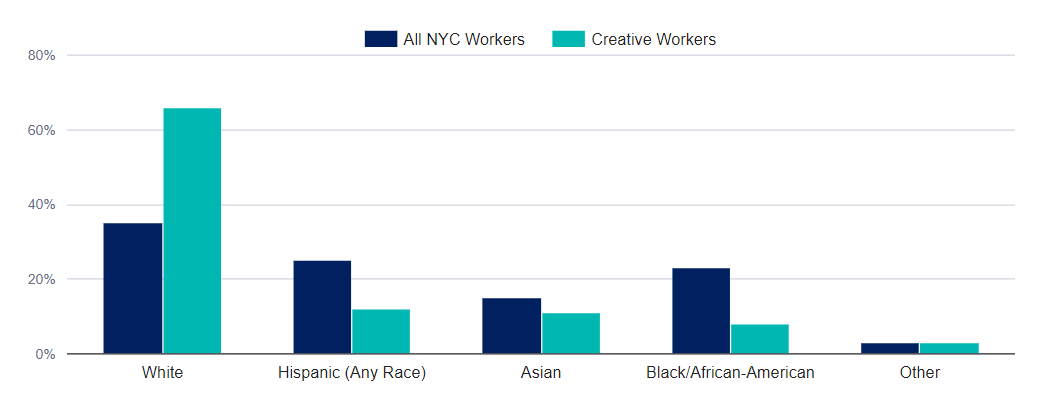

Workers in creative occupations in New York City come from diverse backgrounds, but not to the extent of the overall population. As shown in Chart 10, while one-third of the city’s population is non-Hispanic white, about two-thirds of workers in creative occupations are white. In contrast, black residents make up just 8 percent of creative occupations, far below their 24 percent share of the total city population. Likewise, Hispanics’ share of the creative workforce is less than half their share of the general population. This imbalance has barely budged in the last decade. From 2008 to 2017, the non-Hispanic white share of creative workers in the city dropped just four percentage points from 70 percent to 66 percent.

Other research has produced similar findings. In 2014, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Association of Art Museum Directors sought to document these well-known disparities by conducting a demographic survey of art museum staff.[7] Among the most educated and highly paid positions – curators, conservators, educators and leadership – the Foundation found that 84 percent of staff were non-Hispanic white. Even more discouraging, the survey found that the lack of diversity was pervasive even among museums’ youngest cohorts. The only two art museum job categories with a roughly even split between whites and non-whites were security and facilities. Similarly, a City-commissioned study in 2019 found that non-Hispanic whites make up 68 percent of senior staff at the city’s nonprofit cultural groups and 69 percent of their boards.[8]

Chart 10: Racial Distribution of NYC Creative Workers Compared to Overall NYC Workforce, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

The racial divide is more pronounced in certain occupations. More than 77 percent of editors, writers and authors are non-Hispanic white, and about 82 percent of producers and directors are non-Hispanic white. Every single creative occupation category is majority white with sound operators and media editors being the most diverse, with about 44 percent of the resident workforce filled by non-white New Yorkers.

Chart 11: Racial Distribution of NYC Creative Workers by Occupation, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

The gap between white and non-white earnings is much less in the creative sector than in the city’s workforce as a whole, and has been improving. Median earnings of non-white creative workers were 20 percent less than white creative workers in 2008, and 9 percent less in 2017 (Chart 11). This compares favorably with the city’s workforce as a whole, where non-white workers made fully 45 percent less than their white counterparts in 2017 – a figure that has essentially stayed the same since 2008.

Chart 12: Ratio of Non-white to White Earnings – Creative Workers and All NYC Workers, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

The wage gap was highest among musicians where non-white workers made 42 percent less than their white counterparts in 2017. The gap in median wages among actors, producers and directors, and photographers were all larger than 20 percent. In contrast, non-white artists and performers made more than their white colleagues.

Chart 13: Non-white/White Median Earnings Ratio by Occupation, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

NOTE: *Results should be interpreted with caution due to small sample size.

In terms of gender, the city’s creative workforce overall is somewhat closer to the makeup of the broader city adult population. In 2017, 49.7 percent of all working New Yorkers were female whereas 48.9 percent of New York City creative workers were female – a slight improvement over 2008 when 45.7 percent of New York City creative workers were female.

Chart 14: Gender Distribution of NYC Creative Workers vs Adult Population, 2008 and 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

Some creative occupations are more male-dominated than others. In 2017, 72 percent of musicians, 70 percent of broadcast sound and media operators and editors, and 66 percent of architects and photographers, were male. On the other end of the spectrum were designers, and editors, writers and authors where a majority of the positions were held by women.

Chart 15: Gender Distribution of NYC Creative Workers by Occupation, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

Gender inequities in earnings in creative occupations have declined very modestly. Female creative workers made 6 percent less than male creative workers in 2017. As with race, this compares favorably with the city workforce as a whole, where women earn 17.5 percent less than men.

Chart 16: Female/Male Earnings Ratio – Creative Workers and All NYC Workers, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

The gender wage gap was highest among photographers, where women made 33 percent less than men, followed by artists, architects, and broadcast sound and media technicians. Female actors and performers made more than men, by 21 percent and 60 percent respectively.

Chart 17: Female/Male Median Earnings Ratio by Occupation, 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

NOTE: *Results should be interpreted with caution due to small sample size.

In acknowledgement of the lingering inequities in the cultural sector, one of the key goals of the City’s CreateNYC strategic plan is to make the city’s arts and cultural sector reflect the diversity of the city’s population. To this end, the City has pledged to increase funding for nonprofit arts and culture organizations that serve low-income neighborhoods and underserved communities, expand cultural internship opportunities for CUNY students, and require Diversity, Equity and Inclusion plans from the city’s largest cultural institutions.[9]

Affordability

In no small measure as a result of the precarity of employment and income for certain creative occupations discussed above, and because of lingering inequities in pay based on gender and race, workers in the creative fields often face particularly daunting challenges in making a home in a high-cost locale such as New York City.

For starters, many creative sector workers begin their careers with high student debt loads. The Center for an Urban Future (CUF) found that among four-year universities with the highest net tuition in America, the top ten are all classified as schools of art, music or design.[10] CUF attributed the higher price of an arts education to the need for lower class sizes and specialized equipment and spaces. According to a survey of art school alumni conducted by the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project, student debt had a “major impact on career choices” for 34 percent of graduates in the last five years but only 15 percent of older graduates.[11]

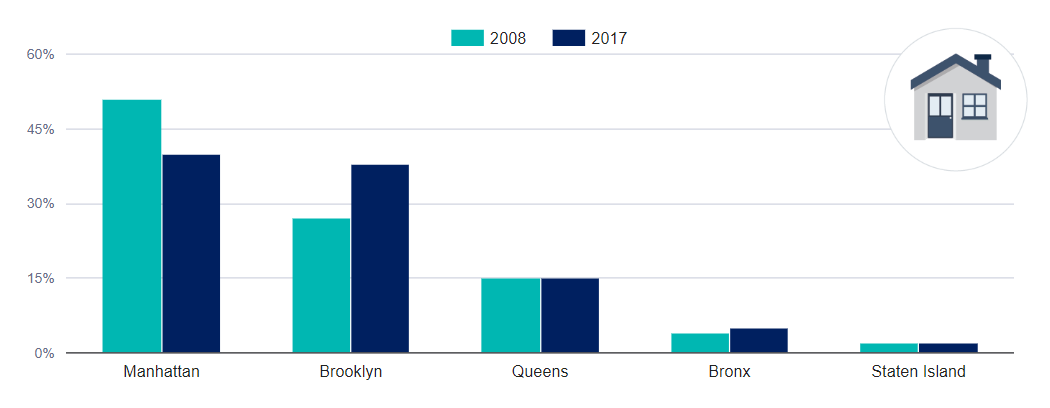

Like most New Yorkers, creative workers face growing challenges to finding affordable housing. Volatile employment and heavy student debt add to the challenges creative sector workers face in the city’s tight housing market. Between 2008 and 2017, the median contract rent in the city rose 35 percent, outpacing growth in average wages in nearly all creative industries.[12] Given the growing affordability challenges for creative workers, it is not surprising that over the last decade New Yorkers in the creative occupations have been spreading from higher-rent neighborhoods that had once functioned as strongholds for those working in the arts and culture sector to lower-rent areas outside of Manhattan.

As shown in Chart 18, Manhattan housed more than half of the city’s resident creative worker population in 2008, but its share fell to 40 percent in 2017, as the number of creative workers living in Manhattan contracted. During this period, Manhattan’s share of the city’s overall population held steady at 20 percent in 2008 and 19 percent in 2017. In contrast, the number of residents in creative occupations boomed in the other boroughs. From 2008 to 2017, Brooklyn’s share of resident creative workers rose from 27 percent to 38 percent; the Bronx and Queens gained slightly in share as well.

Chart 18: Resident Creative Workers Population by Borough in 2008 and 2017

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller estimates based on Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

In 2008, the Upper West Side was the neighborhood with the highest concentration of people working in creative occupations, housing nearly 18,000 creative workers, or roughly 9 percent of the total creative population. But by 2017 there were only approximately 14,000 creative workers living in the neighborhood, or 6 percent of all city creative workers. Declines of more than 2,000 creative residents also occurred in the neighborhoods of Chinatown and the Lower East Side; Chelsea, Clinton, and Midtown Manhattan; Murray Hill, Gramercy & Stuyvesant Town and Battery Park City, Greenwich Village and SoHo.

The exodus of creative workers from Manhattan has produced a more dispersed population throughout the city, as the maps below detail. Whereas just one-third of New York City neighborhoods had boasted 2,000 or more creative workers within their boundaries in 2008, that percentage grew to more than half by 2017.

As these Manhattan neighborhoods have lost resident creative workers, other more affordable areas of the city have gained, with the steepest absolute gains occurring in Bushwick; Bedford-Stuyvesant; and Washington Heights, Inwood and Marble Hill.

Chart 19: Change in Number of Creative Professionals for Selected Neighborhoods, 2008 to 2017

From education to community engagement, from career opportunities to creative expression, New York nonprofits play an essential and diverse role in the city’s creative sector. These organizations provide a platform for new and emerging artists. They help preserve the history and culture of neighborhoods, ethnic groups, and ancient civilizations. They offer extraordinary educational opportunities, both inside and outside city schools. And they inspire all New Yorkers, whether as a participant, visitor, or audience member.

The city is home to nearly 2,200 cultural non-for-profit organizations with over $7 billion in annual direct contribution to the economy of the City, including $3.5 billion in wages and salaries to households employed by these institutions.[13] The remaining $3.5 billion of the budgets of these not-for-profit organizations are used to purchase goods and services outside of what their own employees provide. We estimate that, in total, this sector contributes nearly $11 billion to the New York City economy when including the spillover or multiplier effect of employment generated by businesses providing goods and services to these organizations. The city’s not-for-profit cultural sector draws about $8.8 billion in annual revenue from a combination of public and private sources.[14]

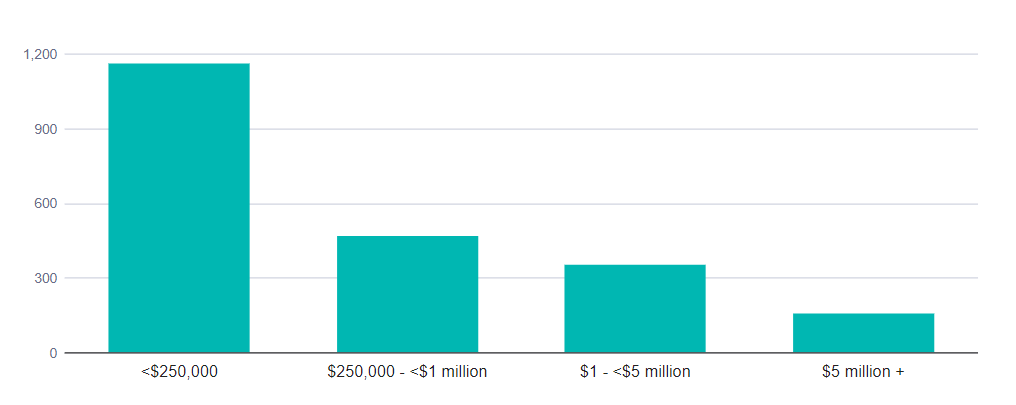

One core strength of the city’s cultural sector is its diversity of small-, mid-, and large-sized nonprofit organizations. As displayed in Chart 20, New York City cultural not-for-profits vary widely in size, with 163 organizations with annual budgets in excess of $5 million and at least 1,167 groups with budgets less than $250,000. Twelve of the largest and best known nonprofits accounted for nearly $2 billion (nearly 30 percent of the total) in direct contributions to the economy, based on their 2017 financial filings.[15]

Chart 20: Not-For-Profit Arts and Cultural Organizations in New York City, by Size of Annual Budget

SOURCE: DataArts, accessed October 18, 2019.

The not-for-profit sector, consistent with its mission, makes art and culture widely available. According to DataArts, of the 120 million people who attend performances and museum visits each year in the city, 60 percent were free to the public, enhancing the experience of living in or visiting the greatest cultural city in the world. Additionally, not-for-profit cultural organizations provided volunteer opportunities for nearly 115,000 New Yorkers.

Non-profit cultural organizations typically rely on a mix of three broad revenue sources: ticket or “gate” sales, private fundraising, and government support. In total, nonprofit cultural organizations raised nearly $2.2 billion in private contributions in 2018 from individuals, directors, corporations, and private foundations.

But not all nonprofits can count on a reliable donor base or an annual fundraising gala, and even among those that can, most operate on tight margins. Smaller arts and culture non-profits are particularly vulnerable to rising costs: A survey conducted by the Long Island City Partnership in late 2015, for example, revealed that 40 percent of local art and cultural groups did not think they would still be in the neighborhood in five years or were not sure.[16] The study cited rent and difficulty finding appropriate space as the primary reasons.

Government plays a critical role in keeping these cultural organizations afloat and enabling nonprofits to operate across the city, particularly in lower-income neighborhoods with limited local wealth to draw upon. In the next section we highlight the government commitment to culture and the arts in New York City.

Government Support

City government supports the creative sector in a variety of ways, through several different agencies and entities:

- The Department of Cultural Affairs administers grant funding to non-profit artistic and cultural organizations.

- The Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment (MOME), housed in the Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications, provides programming in support of the film and TV, theater, music, and publishing industries as well as education and training programs.

- The Economic Development Corporation (EDC) supports the fashion industry, and creative technology. EDC initiatives for the fashion industry include the Made in NY Campaign, Fashion Production Fund, Fashion Future Graduate Showcase and Fashion Manufacturing Initiative, as well as NYCxDesign which showcases NYC design work across a variety of design specialties.

- Relatedly, NYC & Company, a nonprofit that provides marketing services under a City contract, promotes tourism in the City, much of which is driven by the City’s cultural offerings.

No one agency or office in City government is charged with overseeing the broader sector, however, leading to inconsistent attention and fractured policymaking relative to one of the City’s key sectors.

City Funding for Culture and the Arts

Recognizing the value of culture and the arts to New York City, the City government provides direct support to cultural organizations through several different channels, including operating and capital subsidies for 34 organizations in the City’s Cultural Institutions Group (CIG) as well as individual grants of varying amounts for non-profit arts and cultural organizations each fiscal year that are awarded through the Department of Cultural Affairs’ Cultural Development Fund (CDF). The City Council also allocates funding to cultural organizations – over $28 million budgeted in City fiscal year 2020 – through a variety of initiatives.

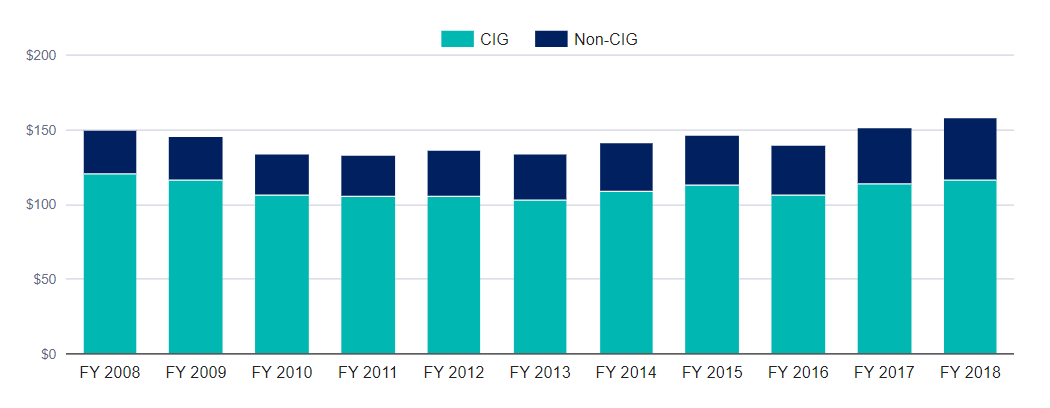

During the last recession, DCLA funding fell 11 percent over two years from $161 million in FY 2008 to $143 million in FY 2010. Funding was not restored to pre-recession levels until FY 2015. Following the passage of a law requiring the City’s first comprehensive cultural plan, the Mayor and City Council funded an additional $19 million in the FY 2017 budget for cultural organizations, bringing total funding to $182 million, a nearly 12 percent increase from the prior year.[17]

The majority of DCLA’s budget provides direct support for cultural organizations. In FY 2018, operating grants to the 33 CIGs and other non-profit institutions and organizations totaled $158 million. The department also committed $75 million in capital funding in FY 2018. The FY 2019 budget also included $3 million in grants for individual artists and smaller organizations ineligible for direct city funding.[18]

Chart 21: Department of Cultural Affairs Grants, $ in millions

Source: Office of the Comptroller

Cultural Institutions Group

The City provides direct financial support to non-profit cultural organizations in the form of operating and capital subsidies. Through a public-private partnership dating back to 1869, the City provides direct financial support to 34 non-profit cultural organizations that operate on City-own property, collectively known as the Cultural Institutions Group (CIG).[19] CIG members receive capital and operating support from the City to help meet basic maintenance, security, energy and other costs. In return for this support, these institutions are committed to ensuring access to cultural, historical and scientific programming for all New Yorkers.

The CIG represents a broad spectrum of cultural endeavor, from art and natural history museums to historical societies, theaters, concert halls, performing arts centers, botanical gardens and zoos. Institutions range from the internationally renowned Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Academy of Music to community-based organizations such as the Jamaica Center for Arts and Learning, the Bronx Museum of the Arts, and the Staten Island Botanical Garden.

About three-quarters of the City’s grants to non-profit organizations go to the CIGs, who make up just 3 percent of total grantees. In FY 2018 $116 million out of $158 million in operating subsidies went to the CIGs. Nonetheless, operating subsidies to the CIGs remain below their peak of $120 million in FY 2008.

Individual funding amounts for the CIGs are determined historically and are not formula-driven.[20] The top three recipients – the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History and the Bronx Zoo – collectively received $55 million in FY 2018, close to half of total CIG funding. Individual amounts have been relatively stable over time. Although the City’s largest and most renowned institutions receive the largest amounts, the smaller institutions generally rely more heavily on DCLA funding. For example, while The Metropolitan Museum’s $24 million grant made up less than 7 percent of its annual revenue in 2016, DCLA’s grant to the Bronx County Historical Society – the smallest CIG grant recipient – accounted for about 36 percent of that organization’s total revenue.[21]

Grants to Other Cultural Organizations

Non-CIG organizations must apply and compete for DCLA funding through the Cultural Development Fund. In the last few years, subsidies to these groups have grown at a faster clip than CIG funding, increasing by 27 percent from $32.3 million in FY 2014 to $41 million in FY 2018. Faster growth has been driven by both a higher number of grantees and higher award amounts. The number of organizations receiving grants increased from 881 to 937 and average grants grew from about $37,000 to $44,000.

Most of the non-CIG grants are concentrated in Manhattan. As shown in Table 3, Manhattan-based organizations account for 65 percent of the organizations receiving grants in FY 2018 and 61 percent of total grant funds. This composition has remained largely unchanged since FY 2014, as shown in Table 4.

Table 3: Borough Distributions of FY 2018 Non-CIG Grants

| No. of Organizations | Grants | Average | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Share | Amount | Share | ||

| Bronx | 44 | 4.7% | $3,308,625 | 8.1% | $75,196 |

| Brooklyn | 194 | 20.7% | 7,759,775 | 18.9% | 39,999 |

| Manhattan | 608 | 64.9% | 25,124,850 | 61.3% | 41,324 |

| Queens | 71 | 7.6% | 3,924,500 | 9.6% | 55,275 |

| Staten Island | 20 | 2.1% | 886,600 | 2.2% | 44,330 |

| Total | 937 | 100.0% | $41,004,350 | 100.0% | $43,761 |

Source: https://data.cityofnewyork.us/Recreation/DCLA-Programs-Funding/y6fv-k6p7

Table 4: Grants to Non-CIG Cultural Organizations FY 2014 and FY 2018

| FY 2014 | FY 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Share | Amount | Share | |

| Bronx | $2,527,835 | 7.0% | $3,308,625 | 8.1% |

| Brooklyn | 5,846,085 | 17.8% | 7,759,775 | 18.9% |

| Manhattan | 19,942,585 | 63.0% | 25,124,850 | 61.3% |

| Queens | 3,373,580 | 10.1% | 3,924,500 | 9.6% |

| Staten Island | 651,855 | 2.0% | 886,600 | 2.2% |

| Total | $32,341,940 | 100.0% | $41,004,350 | 100.0% |

Close to one-third of the grants awarded in FY 2018 were to multi-disciplinary organizations, many of which support individual artists and organizations with resources, networks, and funding, such as the Queens Council on the Arts and the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council. As Table 5 shows, theater groups are the second largest recipient of non-CIG grants, followed by music organizations, museums, and dance companies.

Table 5: DCLA Grants to Non-CIG Cultural Organizations by Discipline

| FY 2014 | FY 2018 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Share | Amount | Share | |

| Multi Discipline Orgs. | $10,154,965 | 31.4% | $13,429,430 | 32.8% |

| Theater | 5,604,750 | 17.3% | 6,427,360 | 15.7% |

| Music | 3,909,610 | 12.1% | 4,830,775 | 11.8% |

| Museum | 3,862,655 | 11.9% | 4,469,160 | 10.9% |

| Dance | 3,322,450 | 10.3% | 3,919,075 | 9.6% |

| Visual Arts | 1,471,205 | 4.5% | 2,160,525 | 5.3% |

| Unclassified | 875,745 | 2.7% | 1,658,475 | 4.0% |

| Film/Video/Audio | 1,192,450 | 3.7% | 1,251,995 | 3.1% |

| Literature | 600,615 | 1.9% | 800,525 | 2.0% |

| Humanities | 441,765 | 1.4% | 511,200 | 1.2% |

| Architecture/Design | 374,645 | 1.2% | 471,125 | 1.1% |

| Folk Arts | 264,985 | 0.8% | 434,005 | 1.1% |

| Science | 103,275 | 0.3% | 196,100 | 0.5% |

| Photography | 57,775 | 0.2% | 164,100 | 0.4% |

| Other | 15,760 | 0.0% | 163,050 | 0.4% |

| New Media | 84,035 | 0.3% | 117,450 | 0.3% |

| Crafts | 5,255 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Total | $32,341,940 | 100.0% | $41,004,350 | 100.0% |

Source: Department of Cultural Affairs

Capital Funding

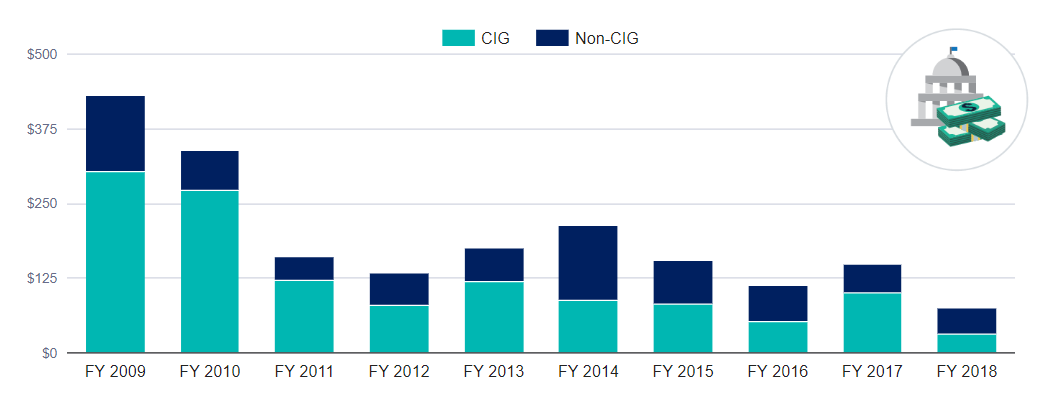

The Department of Cultural Affairs provided $1.94 billion in capital funding to cultural organizations across the City in the decade between fiscal years 2009 and 2018. Two-thirds, or $1.25 billion, went to members of the Cultural Institutions Group, while other cultural organizations received $692 million in capital funding. Capital commitments peaked in FY 2009, at $430 million, and fell as the capital budget was cut in the wake of the 2008-09 recession.[22] But while operating and programmatic support has increased steadily since fiscal year 2013, capital funding has remained at or below $150 million annually in the last four fiscal years.

The current administration has de-emphasized capital funding for members of the Cultural Institutions Group. In the last three years, City-funded capital commitments for members of the CIG have averaged less than one-third of their level from FY 2008 through FY 2014.

Chart 22: DCLA Capital Commitments, FY 2009-FY 2018, $ in millions

Source: Office of the Comptroller from New York City Financial Management System data.

Some 200 non-CIG cultural organizations received a total of $692 million in capital funds from the City over the last decade. The range of recipients is broad, spanning large, well-known cultural institutions such as the Whitney Museum, Park Avenue Armory, or Signature Theater, to smaller, local organizations such as the Louis Armstrong House, the Central Brooklyn Jazz Consortium, or the St. George Theater. The largest single non-CIG capital grant in the past decade was for construction of The Shed, a multi-disciplinary cultural performance space which opened in Hudson Yards in March 2019.

Because of restrictions on the kinds of projects that are eligible to receive City capital funding, cultural organizations that are not on City-owned property typically receive capital funding for equipment that is not attached to real property, including lighting and audio systems, ticketing scanners, or computer equipment. Nonetheless, some organizations have received funding for construction of new facilities and for expansions or renovations of existing buildings. These types of projects require the City to retain a first priority lien on the property owned or leased by the cultural organization for a term equivalent to the bonds issued to finance the project.

The process of drawing down capital funds is notoriously onerous for non-profits of all kinds, including cultural organizations. The many steps, from capital eligibility determination, to ensuring and documenting adherence to various City and other governmental requirements, to submitting payment requests, require multiple layers of review and extensive and detailed documentation. The entire process can place smaller and less financially robust organizations into a position of considerable financial strain.

Federal and State Funding

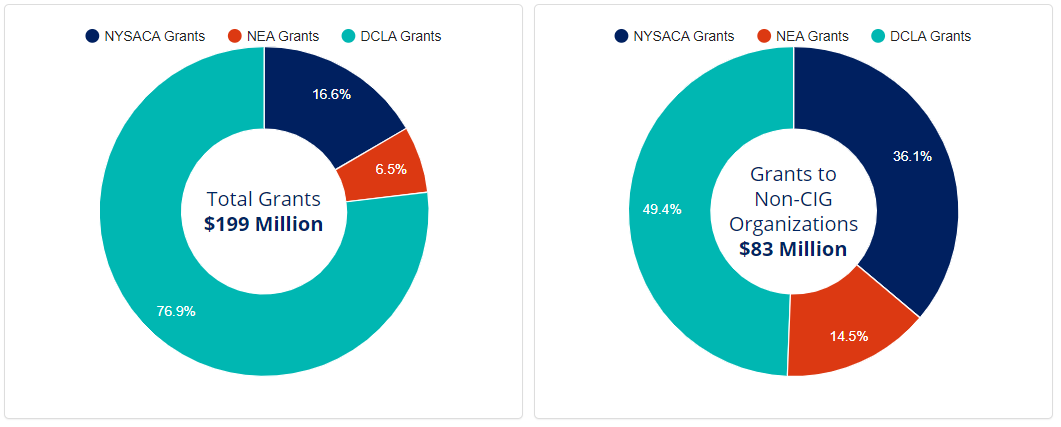

In addition to City support, non-profit cultural organizations in the City also receive grants from the Federal and State governments. The Federal grants are disbursed primarily by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), while State grants are disbursed primarily by the New York State Council for the Arts (NYSCA).

Federal and State support is much less than that provided DCLA, accounting for less than a quarter of total government funding for non-profit cultural organizations in FY 2018 (Chart 23).[23]

Chart 23: FY 2018 Government Funding for Non-Profit Cultural Organizations, $ in millions

SOURCE: Office of the Comptroller; Department of Cultural Affairs; National Endowment for the Arts; New York State Council on the Arts.

Federal funding through the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) benefits over 400 city arts and cultural organizations. After peaking at $20.3 million in federal fiscal year (FFY) 2009 as part of the federal stimulus program in response to the recession, total NEA grants to city organizations have been roughly flat for the last seven years, averaging $13.9 million since FFY 2012. The average grant size is roughly $32,000 per recipient.

The New York State Council for the Arts (NYSCA) provided grants to over 1,200 city cultural groups in state fiscal year 2018. NYSCA funding for city arts and culture rose from $20.3 million in State fiscal year (SFY) 2012 to $33.1 million in SFY 2018. SFY 2018 grants include $2.7 million in State Regional Economic Development funding, of which $1.5 million are grants to 26 organizations for “workforce readiness.” The SFY 2018 grants also include six capital grants totaling $7.5 million. The majority of NYSCA grants, which average under $20,000, are for general support, whether operating or programmatic.[24]

Unlike DCLA, NYSCA does provide grants to individual artists. About 80 artists per year – primarily in film and media and music, but also in theater and dance – receive grants each year.

Federal and state funding for the arts and culture provides a crucial additional source of revenue for smaller organizations. Most of the Federal and State grants are awarded to non-CIG organizations. Of the $33.1 million NYSCA grants to 1,234 New York City non-profit cultural organizations in State fiscal year (SFY) 2018, $29.8 million were made to non-CIG organizations. Similarly, of the $13.3 million NEA grants to 451 city organizations in Federal fiscal year (FFY) 2017, $12.2 million were awarded to non-CIGs.

Many of the same organizations that receive funding through DCLA also are the recipients of NEA and NYSCA grants, although 45 percent of organizations that received government funding between 2012 and 2018 received it from only one of the three organizations.

As with City support, Manhattan-based organizations received the bulk of the NEA and NYSCA grants. As shown in Table 6, Manhattan-based organizations received more than 70 percent of NEA and NYSCA grants in FFY 2018 and SFY 2018. Together, non-profit cultural organizations in Manhattan and Brooklyn received more than 90 percent of NEA and NYSCA grants in FFY2018 and SFY 2018, respectively.

Table 6: NEA and NYSCA Grants to Non-CIG Cultural Organizations

| NEA Grants (FFY 2018) | NYSCA (SFY 2018) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Share | Amount | Share | |

| Bronx | $405,000 | 3.3% | $1,057,934 | 3.5% |

| Brooklyn | 2,501,500 | 20.5% | 5,450,754 | 18.3% |

| Manhattan | 9,074,500 | 74.4% | 22,443,107 | 75.2% |

| Queens | 195,000 | 1.6% | 614,868 | 2.1% |

| Staten Island | 25,000 | 0.2% | 261,500 | 0.9% |

| Total | $12,201,000 | 100.0% | $29,828,163 | 100.0% |

Note: FFY: federal fiscal year (October 1, 2017 to September 30, 2018); SFY: state fiscal year (April 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018)

Other Government Support

Besides direct support to non-profit cultural organizations, City support is also provided to the creative sector through a variety of other programs.

Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment

In 1966, Mayor John Lindsay established the Mayor’s Office of Film, Theater and Broadcasting, the first of its kind in the world, helping to boost film production in the 1960s and 1970s.[25] Today, the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment (MOME) continues to coordinate and support film and television production, but also provides broader support to the film, TV, theater, music, advertising, publishing, and digital content sectors.

MOME has a number of career development programs, including programs focused on women in film, TV and theater, and training programs for production assistants, post-production, animation, and other occupations.

MOME also sponsors programs to both promote the sector and to enhance access to its offerings, including Broadway in the Boros and NYC Music Month.

The City’s Office of Nightlife, created in 2017, is also housed at MOME.

New York State and City Film Tax Credits

Many government and industry officials argue that the expansion of the City’s film industry is due in large part to numerous tax incentives that New York State offers to the industry to keep production costs competitive with other localities. Tax credits specific to the film industry were first instituted in New York State in 2004 when the State established the Film Production Tax Credit program. This provided production companies with a 10 percent tax credit for costs related to actual film shooting that took place in New York State. New York City, under the Bloomberg Administration, coupled the State credit with its own credit equal to 5 percent of eligible production costs, as part of a program of the Mayor’s Office of Film, Theatre and Broadcasting, dubbed the “Made in NY” initiative.[26]

The credits were seen as a necessary measure to stem the tide of film production that had relocated to other localities that were offering a more favorable tax environment. In particular, beginning in 1997, the Canadian government and its provinces had approved generous rebates, which combined could total up 70 percent of production costs for foreign producers who agreed to shoot in the country. Prominent TV series and films such as Chicago and New York Minute, which ostensibly were based in American cities, were shot on location in Toronto. New York, along with other States, responded by offering their own credits to film companies.[27]

Since their first establishment in 2004, the tax credit program was subsequently expanded to provide both greater benefits and include post-production activities and commercials as well. The New York City film production credit program, however, expired on December 31, 2011.

Film Production and Post Production Tax Credits

In its current form, the State allocates up to $420 million per year for film production and post production ($25 million of the total credits are allocated to post production). Production companies may be eligible to receive a fully refundable credit of 30 percent of qualified production and post-production costs incurred in New York State.

For the period 2015-2022, productions with budgets over $500,000 can receive an additional 10 percent credit on qualified labor expenses incurred in upstate counties. There is a maximum of $5 million per year that can be allocated for the additional 10 percent credit on qualified labor expenses.

Commercial Production Tax Credits

The State also allocates $7 million per year to encourage qualified production companies to produce commercials in New York State. The $7 million per year consists of three components for companies: shooting commercials Downstate ($3 million), shooting Upstate ($3 million), and those demonstrating incremental “growth” in commercial production ($1 million).

Other Film & Television Incentives

Both New York City and State have offered various one-time incentives and supports to the film and television industry. For example, in the early 2000s, the City helped jumpstart development of Steiner Studios at the largely abandoned Brooklyn Navy Yard by contributing $28 million in infrastructure improvements.[28] Steiner is now the largest studio in New York.[29] More recently, the City pledged $36 million in tax credits to York Studios for constructing new studio space in the Soundview neighborhood of the Bronx.[30] The State has also actively supported the industry through one-time subsidy deals. Following the retirement of David Letterman, the State awarded $11 million in tax credits and a $5 million capital grant to retain The Late Show in New York City.[31] The State’s development agency, Empire State Development, also facilitated the sale of a former state-owned prison on Staten Island in 2014 to Broadway Stages to be converted into a 100,000 square foot film and television production studio space.[32]

New York State Musical and Theatrical Production Credit

New York State provides a refundable tax credit for musical and theatrical producers to tour productions and tryouts within New York State outside of New York City. The credit is equal to 25 percent of qualified expenditures, against either the business franchise tax or personal income tax (for sole proprietors or partnerships). To be eligible, a company must produce a live, dramatic stage presentation on a tour that consists of eight or more shows in three or more localities. The credit covers production and transportation costs.

CreateNYC

The de Blasio administration has also stepped up efforts to diversify cultural organizations and expand access to arts and culture in underserved areas of the City. In January 2016, DCLA launched an initiative to promote and cultivate diversity among staff and audiences in cultural organizations, and in July 2017, the administration released its first comprehensive cultural plan for the City, CreateNYC, laying out a blueprint for expanding the cultural sector and supporting arts organizations and artists in all five boroughs. The cultural plan includes milestones established to review progress and evaluate implementation. The Plan includes strategies to diversify funding distribution in underserved communities, including people with disabilities, preserve and develop workspaces for artists, encourage professional development of cultural workers from diverse communities and increase access to arts, culture and science education.

IDNYC

The de Blasio administration created a municipal identification card in 2015, IDNYC, one feature of which was to provide cardholders with free annual memberships at members of the Cultural Institutions Group and other cultural organizations, as well as discounts at several entertainment venues. According to a 2016 evaluation of the program’s first 18 months, some 45 percent of cardholders said that access to memberships at cultural institutions was “quite a bit” the reason for getting an IDNYC card.[33]

Culture Pass

Public interest in accessing New York’s cultural offerings remains strong. Culture Pass is a program for cardholders of the Brooklyn Public Library, the New York Public Library, and the Queens Library. Using their library cards, New Yorkers 13 and older can reserve passes and get free admission to dozens of New York City cultural institutions, including museums, historical societies, heritage centers, public gardens, and more. In the first week the Culture Pass was operating, New Yorkers reserved 9,500 tickets, and libraries experienced an influx of library card applications.[34]

Percent for Art

The Percent for Art law initiated by Mayor Ed Koch in 1982, requires that one percent of the budget for eligible City-funded construction projects be spent on artwork for City facilities. The program is administered by the Department of Cultural Affairs. According to data posted by the Department in November 2018, since inception, more than 300 Percent for Art projects have been completed at about 270 City facilities by 300 artists across the City.

Educational Programming

Several City programs promote arts education. Materials for the Arts is an interagency collaboration (DOE, DCLA, and Department of Sanitation) which provides a way for companies and individuals to donate supplies to nonprofit organizations with arts programming in public schools.

Additionally, the New York City Department of Education provides instruction in art and music to students at all grade levels in certain schools. According to the latest “Arts in Schools Report,” published by the City’s DOE, over the last four years the City added 444 new full-time certified arts teachers.[35] In the 2017-18 fiscal year, the total school budget for the arts was $433 million, according to the report, including $402 million in personnel costs, $23 in arts services and other arts-related expenses and $8 million in arts supplies and equipment.[36]

The City Council’s Cultural After School Adventure, or CASA, program, provides grants to schools in each Council district to work with a cultural organization to provide arts and culture programming for students. The CASA program is funded at $18.6 million in FY 2019.

After-School and Senior Center Programming

In addition to funding provided through DCLA, the City’s Department for Youth and Community Development (DYCD) and the Department for the Aging (DFTA) fund a wide variety of arts, music and other cultural programs for children and seniors. In addition to the CASA program funded through DCLA, in FY 2018 the City Council allocated close to $2 million to fund more than 100 grants for after-school programs involving art, dance, theater, museums, or music.[37] More than half of the funding was allocated to the Sports and Arts in Schools Foundation, which offers a range of performing and visual arts after-school programs to underserved students, in addition to sports and academic classes. The Council also provided more than $3.3 million in FY 2019 to support arts programming for seniors through the SU-CASA program.

NYCxDesign

Initiated in 2013 by the New York City Council, NYCxDesign is an annual event held in May, modeled on Fashion Week, to highlight the City’s design industry. It is sponsored by the City’s Economic Development Corporation (EDC) with the collaboration of the other City agencies, the Council, and a steering committee consisting of members of the design industry. With an estimated attendance of 347,000 in 2018, including 99,000 visitors from outside the New York City area, the event highlights design in a broad range of disciplines, from digital and tech, to engineering, home furnishings, manufacturing, and others.[38]

Cultural Districts

During the fiscal crisis of the 1970s, the group of museums lining Fifth Avenue created a consortium called Museum Mile.[39] The group held its first annual festival in 1978 and has since attracted more than one million total visitors to its annual events.

Today there are a variety of models for arts and cultural districts in New York City. Some districts offer grants to artists and artistic organizations, while other arts districts work simply to promote their members. Some receive City funding, while others are entirely self-funded.

To date, the City’s largest initiative to create a cultural district involved a public-private partnership between the City, the State, and existing cultural institutions in downtown Brooklyn.[40] The long-term effort to create the Brooklyn Cultural District included a rezoning in 2004 and involved the NYCEDC, the Department of Cultural Affairs, the Department of Housing Preservation and Development, the Department of City Planning, and more than $100 million in public investment from the City for the creation of cultural and performing arts space and affordable housing.[41] The district’s formation was anchored by the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), and cohesion among the dozens of disparate groups within the district is further facilitated by two nonprofit organizations – the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, which also manages three local Business Improvement Districts, and the Downtown Brooklyn Arts Alliance, which advocates for the needs of the community.

Other examples of existing cultural districts in the city include the Kaufman Arts District, Fourth Arts Block, which leads the East 4th Street Cultural District, and the Little Haiti Cultural and Business District in Flatbush.

Space

In February 2017, the City announced a $136 million commitment to a ‘Made in New York’ Campus at Bush Terminal in the Sunset Park section of Brooklyn, to be used for both garment manufacturing and film and television production. The City pledged that the investment would “support” more than 1,500 permanent jobs. The subsequent RFP sought bidders to “develop and operate a best-in-class production facility campus for film and television production, video and photo shoots, sound-recording, and emerging media sectors such as AR/VR.”

Artist Workspace and Housing

The City also provides some assistance to help provide affordable living and work space to working artists.

AREA

As a step toward providing affordable living and work space for artists in New York City, Mayor de Blasio announced in 2015 a commitment to create 1,500 units of affordable housing and 500 units of artist workspaces over a decade under the Affordable Real Estate for Artists, or AREA, program. A Request for Expressions of Interest (RFEI) was issued in early 2018 and a first round of qualifying arts organizations was announced in 2019. The selection as a qualifying organization only means that EDC and DCLA “may discuss” future development projects incorporating affordable artist workspace on City-owned sites with those organizations. To date, no projects have begun under the AREA initiative.

Zoning and Development

Working artists who are certified as such may qualify for joint live/work space in select zoning districts in the SoHo and NoHo neighborhoods. Certification permits fine artists working on a professional level who demonstrate a need for a live/work loft space to reside in specific lofts zoned for manufacturing.

The City is redeveloping the former Spofford juvenile detention center in the Bronx into a live/work campus, anticipated to include 15,000 square feet of artist workspace.

Recommendations for Strengthening and Sustaining the Creative Sector

Art and culture, creativity and innovation permeate city life: from its world-class cultural institutions, to its leading role in fashion, advertising, and publishing, to its numerous tech start-ups – New York City is synonymous with creativity.

Yet the City cannot take for granted its historic role as a beacon for artists and other creative workers to be inspired and collaborate with the best in their fields. Along with other workers and businesses, artists and creative institutions struggle with rising rents and the changing nature of work in the 21st century economy.

For the creative sector to survive in a city that is increasingly inaccessible to artists and creative ventures, City government must recognize and embrace that the creative sector and its workforce are central to New York – both of its economy and of its “brand.” The sector brings life and character to local neighborhoods, offers employment to tens of thousands of New Yorkers, attracts visitors from around the globe, and stimulates economic activity in many other supporting industries.

The following recommendations lay out a vision to retain and strengthen the City’s creative workers and industries, and fortify New York City’s place in the world as the preeminent creative capital.

Support and Promote the Creative Economy

As a major and defining economic sector, the City needs to treat the creative sector and its industries as assets to be valued, promoted, and cultivated. The City should take a more cohesive, comprehensive, and pro-active approach to promoting its creative sector through the following measures:

1. Strengthen the City’s role

The City should establish an office and interagency task force under the Deputy Mayor for Economic Development with the role of supporting and promoting the creative sector.

Current city policymaking with respect to the creative sector is fragmented and limited in scope. Different city agencies interact with different parts of the sector, but no agency or office has a larger strategic vision for or role in the sector, and there is no institutional cheerleader/promoter. As a result, the City’s policy attention is not commensurate with the importance and impact of the sector, both as an economic engine, and as a resource for New Yorkers – from cultural enrichment, to career pathways.

The City, through a deputy mayor-level office, should be seeking to promote the sector, motivate tourism and its associated employment, and to facilitate and aid education and training to ensure the existence of a qualified workforce to meet industry demands. Individual agencies should be tasked with developing – and funded and staffed to implement – broader visions as promoters and cheerleaders for their sectors: DCLA should become not just a grants administrator, but a cheerleader and promoter of the city’s cultural organizations. MoME should become not just a permitting agency, but a cheerleader and promoter of the film and television industry (and potentially other sectors as well). NYC & Company should do more to promote the City’s cultural offerings across all five boroughs (see Cultural Districts, below). Finally, EDC should establish a Creative Sector desk that would work with industries in the sector to identify their needs and challenges and take the lead in crafting multi-agency responses to help ensure the future strength of the sector.

As an important first step, the City should undertake a comprehensive assessment of the sector’s varying needs and the challenges faced by creative workers, and produce a strategic plan for the creative sector. The City of London has recently recognized the central role of its creative sector through the creation of a Cultural Infrastructure Plan.[42] The plan recognizes the challenges of affordability that confront the creative sector in London as much as they do in New York City, and proposes four strategies to help address them. Perhaps the London Plan’s greatest significance is to recognize the important contribution of the creative sector, both as an economic engine and as central to the vibrancy of London, and to begin to treat the sector holistically. New York City should undertake a similar assessment and planning exercise to develop a unified and cohesive approach to this all-important sector.

2. Create and promote cultural districts

One night each year, the city shuts down traffic along Fifth Avenue from 82nd Street to 105th Street for the Museum Mile Festival, and the museums open their doors for free to all. This partnership and campaign has increased the visibility of the participating museums and created a world renowned cultural destination. This model of collaboration should be replicated across the city; doing so would help visitors and residents alike discover new cultural resources; promote tourism and development; and strengthen local communities.

Other cultural consortiums already exist across the boroughs with varying levels of funding, City support, and activity, including the Brooklyn Cultural District, Kaufman Arts District, Fourth Arts Block (Lower East Side), and the Little Haiti Cultural and Business District in Flatbush. In September 2018, the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership launched the inaugural Downtown Brooklyn Arts Festival, which included performances, tours, and free outdoor programming from diverse institutions within Brooklyn’s Cultural District.[43]

According to the University of Pennsylvania’s study of New York City’s cultural assets, additional cultural clusters exist in Flushing, Jackson Heights, Long Island City, and Elmhurst in Queens; Harlem, Washington Heights, and Inwood in Manhattan; the South Bronx; St. George, Staten Island; and Flatbush, Bushwick, Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, and Sunset Park in Brooklyn.[44]

New cultural districts could exist in different forms across the city, depending on the needs and desires of local institutions. But one common component should be new signage and wayfinding tools to help visitors – and residents – navigate neighborhoods and unify disparate institutions into a single marketing brand. As local community groups have noted, outside of Manhattan’s grid, city streets can be intimidating and confusing, creating a barrier to accessing the diverse array of city cultural assets.[45] One initiative to facilitate navigating new neighborhoods was the launch of the free LIC Art Bus in 2014.[46] The bus is supported by a philanthropic contribution and makes stops on Saturdays and Sundays in the Spring through Fall at Socrates Sculpture Park, The Noguchi Museum, SculptureCenter and MOMA PS1.

Cultural districts should also be featured and promoted by NYC & Company, the City’s official marketing organization and convention and visitors bureau.

The New York State Legislature has proposed legislation to create state-designated arts and cultural districts, under guidelines established by the State Council of the Arts.[47] A designated district would be eligible for development opportunities, technical assistance in applying for grants, and marketing guidance, provided by the Council and Empire State Development. According to the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies, at least 15 states have a formalized role in the establishment of cultural districts.[48] Most of these states offer technical assistance, but a few also offer tax incentives and exemptions such as sales tax exemptions for goods produced or sold within the district and income tax credits for artists living or working in the district.

Jersey City offers another model. In 2016, Jersey City’s Council approved changes to Journal Square that aims to create an official Art District. The plan aimed to create “cultural amenities” by offering bonuses to potential developers in local buildings if they include spaces for theaters, art galleries, art and dance studios, museums, libraries, rehearsal studios, cafes, or general retail along the corridor. The new zoning also established bonuses for contributions to a public arts fund.

3. Improve the process for providing capital funds to cultural organizations

The process by which the City funds capital projects to non-profit cultural organizations – whether equipment purchases, facility upgrades and renovations, or completely new theaters or other buildings – is slow, rife with bureaucratic hurdles, and financially burdensome, particularly for smaller organizations. The City should conduct a thorough business process review to determine where there are possible redundancies and inefficiencies, where the most significant bottlenecks are, and how the process can be streamlined while protecting the public interest in the use of taxpayer capital funds. In recognition of the financial burden faced by organizations that have to pay out funds and then wait for the City to reimburse them, a bridge loan program, similar to that run by the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services and the Fund for the City of New York, should be studied, that could provide short-term operating cash loans to help smaller organizations that may have difficulty accessing or affording commercial lines of credit.

4. Establish Creative Economy Zones

In November 2014, the New York City Council released a report called “Engines of Opportunity,” which proposed changes to zoning laws including the establishment of “creative economy districts.”[49] These new districts would permit greater commercial density and the development of loft-style buildings in the city’s existing industrial zones. The concept would promote a mix of high-tech manufacturing, creative employment, and office space while limiting allowable space for competing uses such as hotels and storage. For example, the American Can Factory, a 13,000 square foot former manufacturing facility in Gowanus, was converted to provide space for small businesses in design, the arts, publishing, architecture, printing, music equipment, and sound recording, among other uses.

5. Foster creative incubators