The Demographics of Detention: Immigration Enforcement in NYC Under Trump

Executive Summary

New York is home to 3.3 million immigrants from over 150 countries who contribute to the city in countless ways. Across every industry, immigrants power our local economy, collectively contributing $100 billion in earnings each year, while also helping to shape and define our city’s thriving culture.[1] In short, New York City would cease to be New York without the richness and diversity that immigrants bring every day to our schools, our businesses, our neighborhoods, our cultural institutions and broader civic life.

Despite these contributions, many immigrants in New York City are today living on a knife edge, afraid to leave their homes and communities, worried that one day they will be detained by U.S. immigration enforcement officials and not make it home to their families. These concerns are the painful reality for many of our city’s immigrants. And yet, federal agencies have too often failed to provide the public with comprehensive data about the scope of immigration enforcement actions in New York City.

This report from New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer seeks to provide a more complete assessment of the impact of immigration enforcement in New York City by analyzing data from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and immigration court cases. The data clearly show that immigration enforcement actions have increased under the Trump Administration. Specifically:

- Deportations by ICE officers in New York City increased by 150 percent between the final year of the Obama Administration (Fiscal Year (FY) 2016) and the first full fiscal year of the Trump Administration (FY 2018). Deportations of individuals with no criminal convictions rose even more, going from 313 to 1,144, or 265.5 percent—the largest increase of any ICE field office in the country.

- Administrative arrests (an arrest made for a civil violation of immigration law) by ICE officers in New York City rose by 88.2 percent, going from 1,847 arrests in FY 2016 to 3,476 in FY 2018, the third-highest increase of all ICE field offices. This increase reversed a precipitous decline in arrests by ICE officers in New York City during the last few years of the Obama Administration.

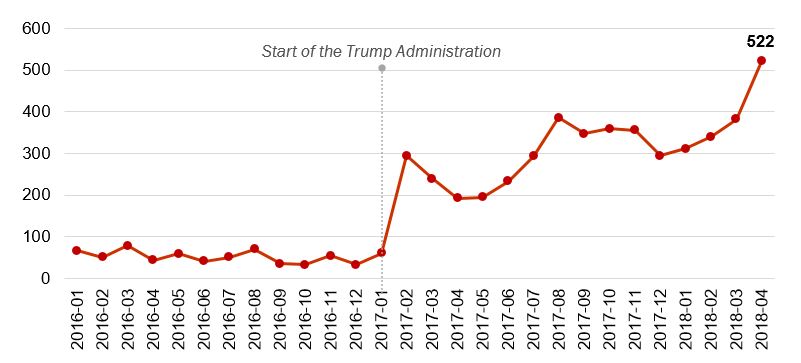

- ICE detainer requests (defined as a request made by ICE to local law enforcement agencies to hold an immigrant in custody longer than the person would otherwise be held so that ICE can gain custody of the immigrant) sent to entities located in New York City have risen significantly during the Trump Administration. Specifically, detainer requests have increased to an average of 312 per month, reaching a high of 522 requests in April 2018, after averaging about 50 per month during the final year of the Obama Administration.

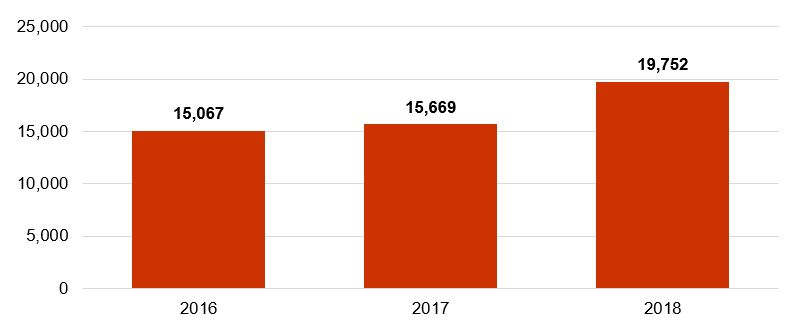

- Immigration court records indicate that the number of new deportation cases involving an immigrant living in New York City grew to an all-time high in FY 2018 of over 19,750 cases—over 30 percent higher than in FY 2016.

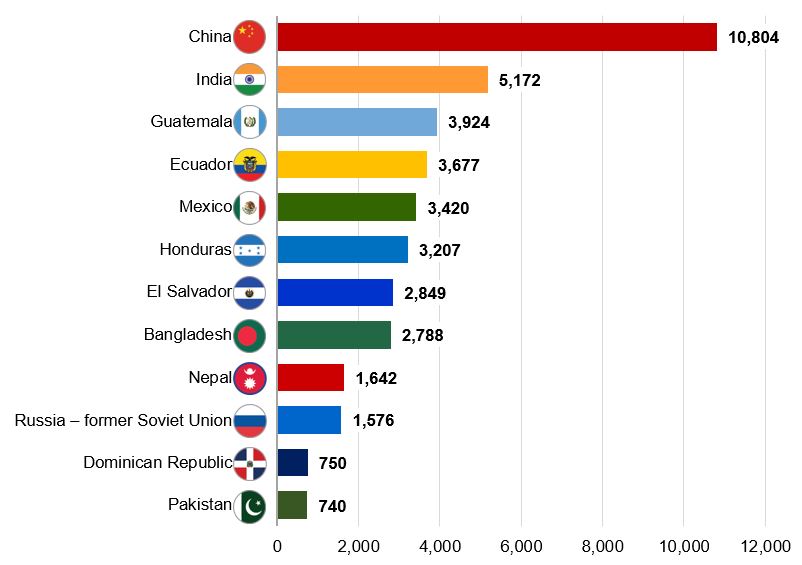

- Chinese immigrants make up the largest nationality of New York City immigrants with immigration court proceedings, with over 10,000 immigration cases (21 percent of cases) begun since FY 2016. Immigrants from India comprise roughly ten percent of all cases, while immigrants from Ecuador account for about 7 percent of cases and immigrants from Bangladesh for about 8 percent of cases.

- Some detained immigrants may have the ability to obtain release by posting a bond to immigration court. Between FY 2014 and FY 2017, the median bond amount set by immigration judges in New York City was $7,500, which is 50 percent higher than median bail set in felony cases in criminal court in the city. During the first half of FY 2018, the latest data available, bond amounts ranged from $1,500 to $100,000, remaining prohibitive for many immigrants who are detained.[2]

Based on these findings, the report makes a number of recommendations for state and local policymakers in order to better support and protect immigrant New Yorkers. These recommendations include:

- The City should work toward ensuring universal representation for individuals in immigration court by expanding funding for legal services and ending its carve-out that restricts access to City-funded legal services for certain low-income immigrants.

- The City should continue to support the operation of the New York Immigrant Freedom Fund—a project of Brooklyn Community Bail Fund in collaboration with community-based organizations and legal service providers—to help pay bond for those detained during immigration proceedings.

- The State should act to restrict immigration enforcement operations in and around New York courthouses by enacting the Protect Our Courts Act.

As the Trump Administration’s crackdown on immigrants continues, New York City and State will need to closely monitor any new federal policies and respond appropriately. As an initial matter, however, these three actions will help provide relief to New York City immigrants at risk of being swept up in the Trump Administration’s draconian immigration enforcement activities.

The Evolution of Federal Immigration Enforcement Policy

Reflective of the President’s anti-immigrant rhetoric, immigration enforcement policy has changed significantly since President Trump assumed office. While the first six years of the Obama Administration were marked by high levels of immigration enforcement activities and failure by Congress to adopt comprehensive immigration reform, in November 2014, the Obama Administration enacted significant reforms that narrowed the focus of immigration enforcement operations. These reforms directed immigration enforcement agents to prioritize for removal a narrow class of immigrants – namely, only those convicted of certain serious crimes or who had only recently entered the country and did not have family or children in the country.[3] As a result, by the end of the Obama Administration, 99 percent of immigration removal proceedings targeted those who had previously been convicted of crimes or who had entered the country after January 2014.[4]

President Trump’s overhaul of federal immigration enforcement operations was instituted almost immediately following his inauguration. Five days after he was sworn in, President Trump signed Executive Order 13768, which was followed by the issuance of new guidance from then-Department of Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly.[5] Among other changes, these new policies gave ICE significantly increased authority to seek the removal from the U.S. of a much larger number of immigrants, including prioritizing anyone who ICE believed to have committed a “chargeable criminal act,” without regard to whether that act was prosecuted or the person was actually convicted of a crime.

Alone, this single reform significantly increased the authority of immigration enforcement officials to seek the removal of a wider category of immigrants. However, for immigrants living in New York City, this policy change must be viewed in conjunction with the president’s other official actions that have further escalated fear, distrust, and anger in immigrant communities.

Some of those official actions have resulted in both deep reductions in new immigrants entering the country, as well as the revocation of legal protections for immigrants already residing in the U.S. Specifically, to restrict new entrants, the Administration enacted:

- A ban on nationals of seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the U.S.;[6]

- Dramatic cuts in the number of refugees resettled in the country;[7]

- Changes to the criteria used to evaluate asylum claims that make gaining asylum more difficult;[8]

- A reduction in visa issuances;[9] and,

- Criminal prosecution of all people who cross the U.S. border without proper legal authorization while separating children from their parents.[10]

At the same time, the Administration has sought to end Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, both of which provide legal work authorization for immigrants who may otherwise lack that status.[11] The Administration has also proposed changing the criteria used to determine which immigrants are or are likely to become a “public charge” and therefore unable to advance through the immigration process. This expansion of the “public charge” test would make it especially difficult for lower-income immigrants and immigrants with disabilities or health conditions requiring extensive treatment to obtain a visa or permanent resident status.[12]

The breadth of these changes reveals the extent to which the Trump Administration has actively worked to reduce the number of current and future immigrants in the U.S. Two years into the Administration, it is possible to begin to assess the impact that these enforcement changes are having across the five boroughs, and how recent experiences differ from the longer-term trends.

Immigration Enforcement in the Five Boroughs

To understand how immigration enforcement in New York City has evolved in recent years, this report analyzes data from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and from immigration court records. ICE is the lead agency responsible for initiating deportation proceedings for those accused of violating immigration law who are residing in the country and detaining and removing immigrants as a result of those proceedings. ICE publishes some data on its enforcement activities across the country in an annual report but generally reveals little about its operations. Consequently, the richest set of data about immigration enforcement activities comes from immigration court records obtained by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University, which receives information through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) agreement with the federal government.[13]

In general, both data directly from ICE and data from immigration court records show that immigration enforcement in New York City has increased dramatically since the start of the Trump Administration. This increase follows a sharp drop in enforcement activities that occurred toward the end of the Obama Administration. Furthermore, immigration court records provide some indication of who these New Yorkers are, where they live, and how long they have lived in the country.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Activities:

Deportations & Arrests

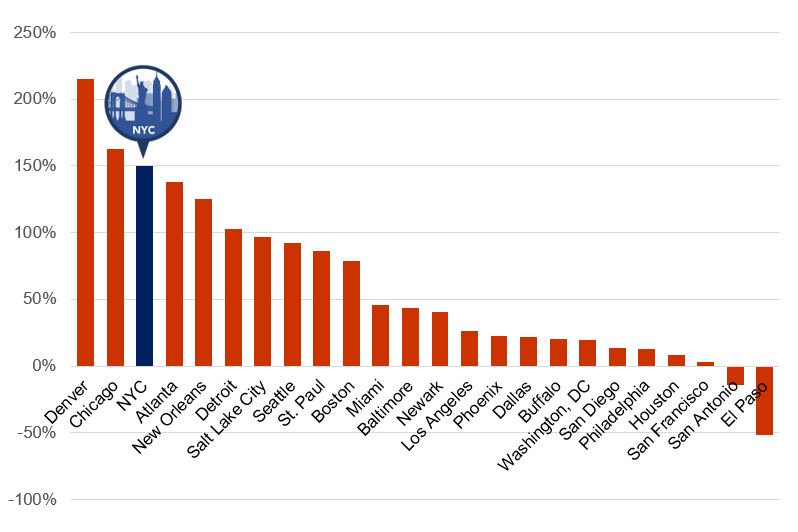

According to data published in ICE’s annual activities reports, deportations and arrests in New York City and beyond increased noticeably in FY 2017 and again in FY 2018, the first complete fiscal year under the Trump Administration.[14] Chart 1 shows that deportations of immigrants by ICE’s New York City office escalated dramatically during this period, increasing from 1,037 to 2,593, or 150.0 percent total, between FY 2016 and FY 2018. On this measure, New York City ranked third in the country, behind only Denver (214.9 percent) and Chicago (162.4 percent) among the ICE’s 24 field offices across the nation.

“I feel unsafe and scared. I can’t leave the house at night or late because I could face discrimination and racism because of my hijab, because of my religion, because I’m Arab. And that’s because of Trump’s speeches that he attacked Muslims.”

Chart 1: Increase in Deportations by ICE Field Office: FY 2016–FY 2018

Source: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Fiscal Year 2017 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report (December 2017), https://www.ice.gov/removal-statistics/2017; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Fiscal Year 2018 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report (December 2018), https://www.ice.gov/features/ERO-2018.

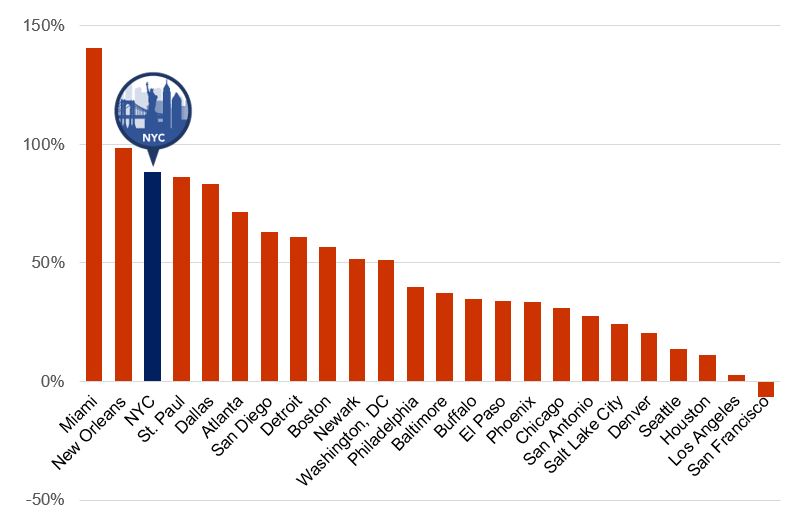

At the same time, arrests by New York City ICE officers increased by 39.5 percent between FY 2016 and FY 2017 and another 34.9 percent between FY 2017 and FY 2018, rising from 1,847 arrests to 3,476 arrests, or 88.2 percent overall. As shown in Chart 2, this was also the third-highest increase observed across the country, exceeded only by the rise in arrests in Miami (140.5 percent) and New Orleans (98.5 percent).

“When I hear the things the new administration says about immigrants, I feel a lot of sadness and indignation because it’s not fair. The majority of immigrants come here to work very hard. New York is a city that has been made by immigrants and we come here to work and give the best that we can give and help the most people we can help. They are not treating us like human beings, but like objects.”

Chart 2: Increase in Arrests by ICE Field Office: FY 2016–FY 2018

Source: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Fiscal Year 2017 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report (December 2017), https://www.ice.gov/removal-statistics/2017; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Fiscal Year 2018 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report (December 2018), https://www.ice.gov/features/ERO-2018.

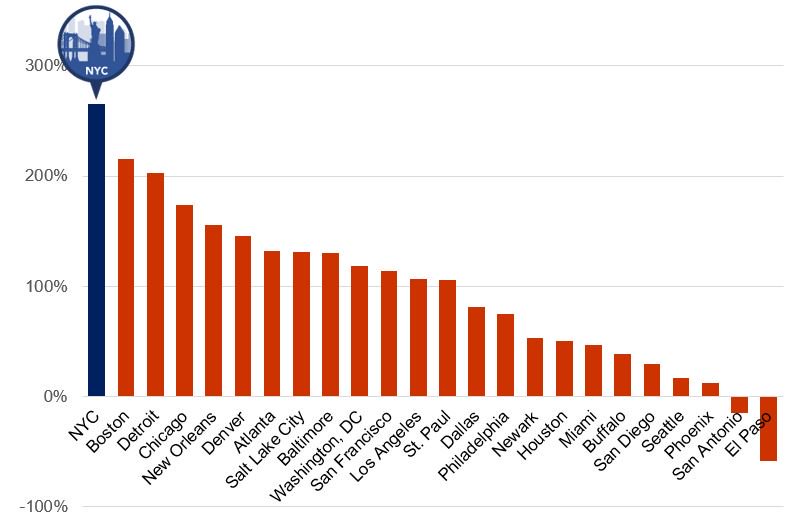

Per ICE’s expanded authority, the overall increase was driven primarily by arrests of individuals with no criminal convictions, who comprised only 13.3 percent of all New York City-area arrests in FY 2016 but more than one-third (36.2 percent) in FY 2018. When looking only at deportations of immigrants with no criminal convictions, New York City experienced the highest increase in enforcement in the nation. As shown in Chart 3, between FY 2016 and FY 2018, deportations of individuals in New York City with no history of a criminal conviction increased by 265.5 percent. These “non-criminal” deportations accounted for 44 percent of all removals in FY 2018, up from 30 percent in FY 2016.

“I have two tumors. I went to a community service center. They told me I cannot enter a shelter because I’m undocumented.”

Chart 3: Increase in Non-Criminal Deportations by ICE Field Office: FY 2016–FY 2018

Source: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Fiscal Year 2017 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report (December 2017), https://www.ice.gov/removal-statistics/2017; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Fiscal Year 2018 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report (December 2018), https://www.ice.gov/features/ERO-2018.

Detainer Requests

One of the ways that ICE gains custody of an immigrant is by sending a “detainer” request to a different law enforcement agency that has custody of an immigrant that ICE is seeking to deport.[15] Data on ICE detainer requests sent concerning individuals in New York City show a similar pattern in recent years. While New York City has a stated policy of not complying with ICE detainer requests, except in limited cases, the monthly number of ICE detainers sent concerning individuals in New York City has risen rapidly during the Trump Administration after a period of decline at the end of the Obama Administration.[16]

As shown in Chart 4, between January 2016 and January 2017, ICE sent about 50 detainers monthly to New York City-based law enforcement entities. Since the start of the Trump Administration, however, detainer requests have increased significantly to an average of 312 per month, rising to 522 requests in April 2018. Importantly, these data do not indicate whether these detainer requests were complied with by the recipient of the request. The New York City Police Department has reported that the department did not comply with the 1,023 detainer requests it received during FY 2017.[17]

Chart 4: Monthly ICE Detainers Sent to New York City: January 2016 – April 2018

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, Immigration and Customs Enforcement Detainers.

Combined, these two datasets suggest a resurgence in ICE enforcement activities under the Trump Administration. But enforcement is only a prelude to what is very often a long, arduous, and expensive court process for immigrants caught in the system.

Immigration Court Data:

Cases brought before an immigration court are generally how the U.S. government orders the deportation of immigrants who are found to no longer be allowed to reside in the U.S. Cases do not necessarily result in removal from the country, as many immigrants with cases are allowed to remain in the U.S. for a variety of reasons. However, as with data about ICE, court data provide a useful prism through which to view changes in immigration enforcement activities in recent years.

Consistent with patterns in ICE data, court records suggest that an increasing number of immigrants in New York City are becoming involved in immigration enforcement proceedings. In fact, as shown in Chart 5, the number of cases involving an immigrant residing in New York City grew to an all-time high of 19,752 cases begun in FY 2018. In total, over 50,000 cases involving a New York City resident were begun in the last three fiscal years.

“If they arrest me, who’s going to take care of my children?”

Chart 5: Number of Cases Involving New York City Residents by Year: FY 2016 – 2018

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, Details on Deportation Proceedings in Immigration Court.

The growth observed in FY 2018 represents a 26.1 percent increase from FY 2017 and a 31.1 percent increase from FY 2016. Notably, the increase in New York City residents with immigration court cases far outpaces the country as a whole, where the number of cases filed nationally grew by only four percent between FY 2017 and FY 2018 and only six percent between FY 2016 and FY 2018.

As discussed in more detail below, TRAC data provides more information about New York City immigrants with court cases.

“America symbolizes a lot of hope, a lot of dreams – but when it comes to this part, it kind of broke my heart. To know my family is breaking apart because of immigration status….Back in the day, I know everybody’s dream is coming to America. Me too. But I never expect it’s going to be in this situation.”

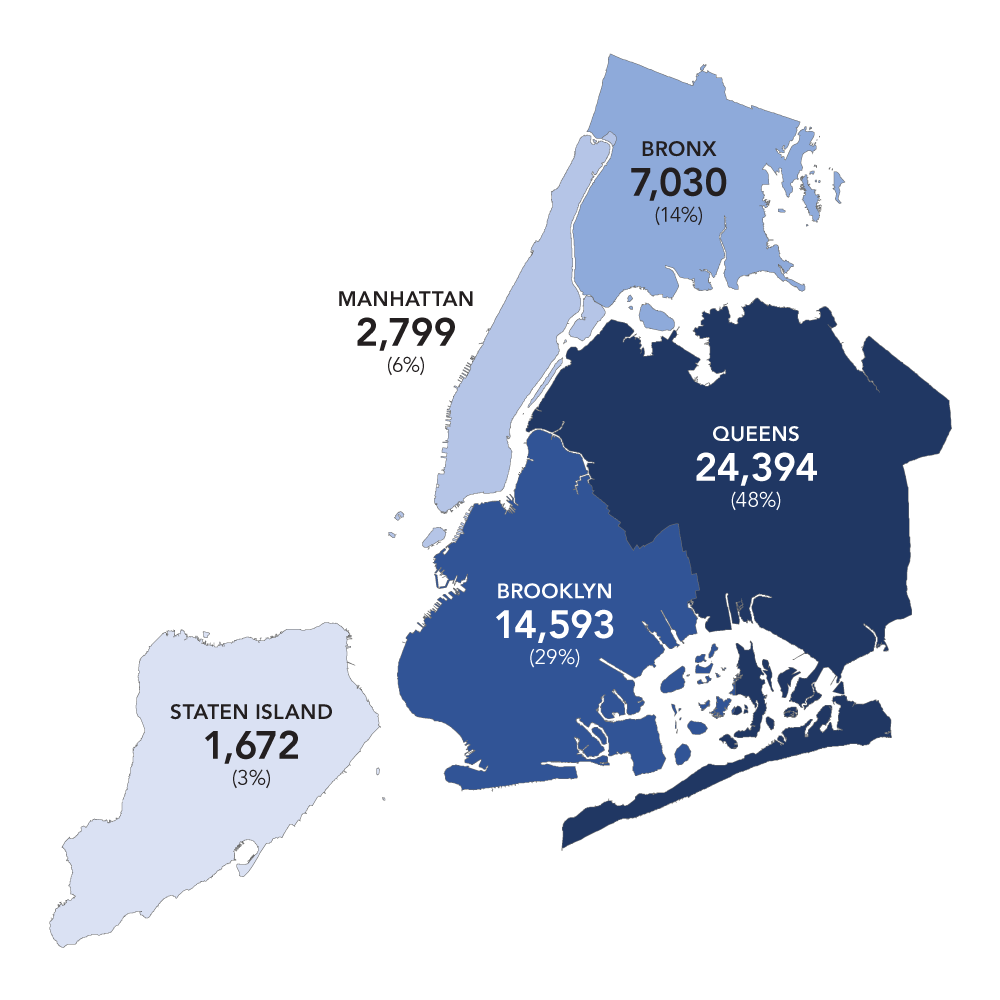

Borough of Residence

As shown in Chart 6, almost half of all cases (48 percent) begun since FY 2016 involve immigrants residing in Queens, while about three in ten cases (29 percent) involved a Brooklyn resident, followed by 14 percent in the Bronx, and under ten percent in Manhattan and Staten Island combined.

Chart 6: Number and Share of Cases Involving NYC Immigrant by Borough: FY 2016 – 2018

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, Details on Deportation Proceedings in Immigration Court.

Nationality

As shown in Chart 7, during the last three years, Chinese immigrants made up the largest nationality of New York City immigrants, with over 10,000 immigration cases (21 percent of cases) begun. Immigrants from India made up about ten percent of all cases, while immigrants from Ecuador accounted for about seven percent of cases and immigrants from Bangladesh for about eight percent of cases. Collectively, immigrants from Mexico and Central America (specifically Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador) accounted for 27 percent of all cases. Chart 6 shows the number of New York City immigrants involved in immigration court proceedings across a number of nationalities between FY 2016 and FY 2018.

Chart 7: Select Nationalities of New York City Immigrants with Immigration Court Cases: FY 2016 – 2018

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, Details on Deportation Proceedings in Immigration Court.

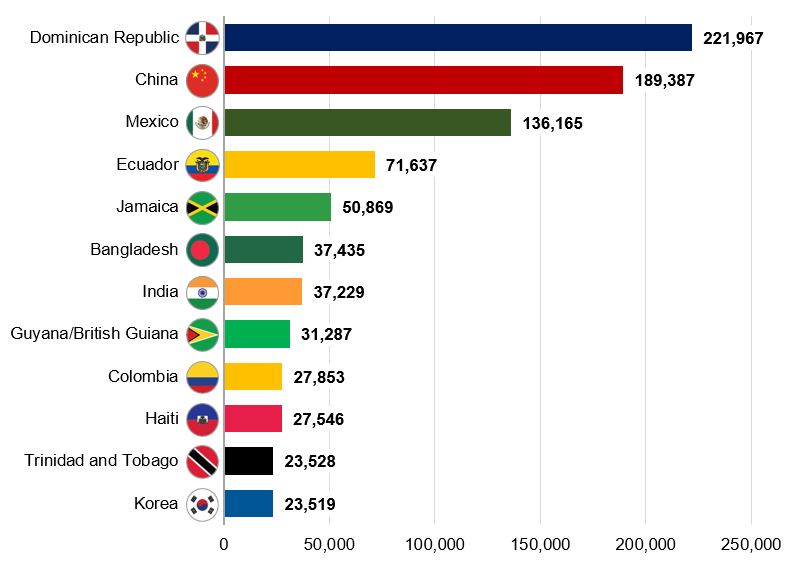

Notably, these immigration court demographics do not precisely reflect the breakdown of non-citizens living in New York City (see Chart 8). For instance, among the twelve countries with the highest number of defendants, six were not represented among the countries with the largest number of non-citizens residing in the city—Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nepal, Russia, and Pakistan.

Chart 8: Non-Citizens Living in New York City, by Country of Origin

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2017 1-Year Estimates.

Length of Residence in U.S.

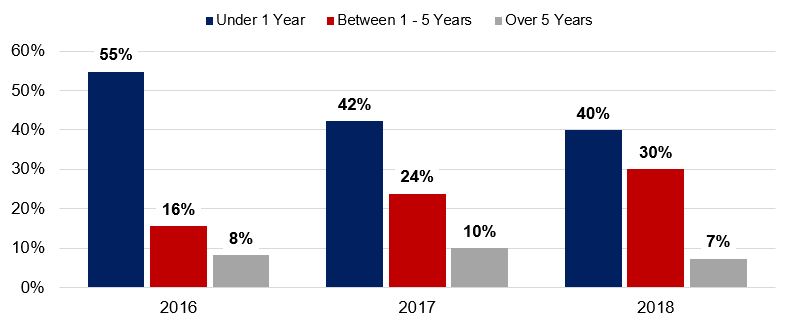

Importantly, given the Trump Administration’s immigration enforcement policy to no longer prioritize for deportation only those residing in the U.S. for a short period of time, a growing percentage of immigration cases involving New York City residents involve immigrants who have lived in the U.S. for longer periods of time. As shown in Chart 9, the share of cases involving New York City immigrants who have lived in the U.S. for under a year has fallen from 55 percent of all cases in FY 2016 to 40 percent of cases in FY 2018. During the same period, the share of cases involving a New York City immigrant who has lived in the U.S. for between one and five years has risen from 16 percent to 30 percent. This trend is similar across the country for all immigrants with removal cases.[18]

“I am a single mom and so my biggest fear is being in a situation where I am not able to take care of my children. If anything were to happen to me, I would be in fear of how my three girls would be able to live day to day.”

Chart 9: Length of Residence in U.S. Prior to Immigration Case for NYC Residents: FY 2016 – 2018

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, Details on Deportation Proceedings in Immigration Court.

Recommendations

Countering the Trump Administration’s aggressive enforcement agenda in order to protect New York City families requires a comprehensive, multipronged approach. While the City and State have implemented a number of supportive policies and programs already, as discussed below, more can be done at all levels of government to build a more humane and just immigration system.

1) The City should work toward providing truly universal representation for individuals in immigration proceedings by expanding existing funding for legal services and removing the carve-out that restricts certain immigrants’ access to City-funded services.

Unlike in criminal court, people in immigration court are not guaranteed the right to an attorney. This means that immigrants without access to legal representation, including children, are left to defend themselves in court, in what is a deeply complex area of law and what may not be their primary language, against expert government lawyers. Lack of representation in these cases increases the risk for exploitation and of outcomes that are not in the individual immigrant’s interest or favor.

In recognition of the critical and growing need for legal services, New York City has increased funding in recent years for a number of programs that provide free legal representation to immigrant New Yorkers, dedicating about $48 million in total in FY 2018.[19] One of the largest such programs is the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project (NYIFUP), a nationally-recognized public-private partnership that supports the provision of lawyers for certain lower-income detained immigrants in deportation proceedings.[20] According to an analysis by the Vera Institute for Justice (Vera), the program has been incredibly successful at helping individuals represented exercise the protections afforded to them under law and remain in the U.S. Specifically, Vera’s analysis found that prior to NYIFUP, only four percent of unrepresented detained cases resulted in an outcome that allowed the immigrant to remain in the U.S. But, for those clients who received legal services through NYIFUP, Vera projected that almost half would be allowed to remain in the U.S.[21]

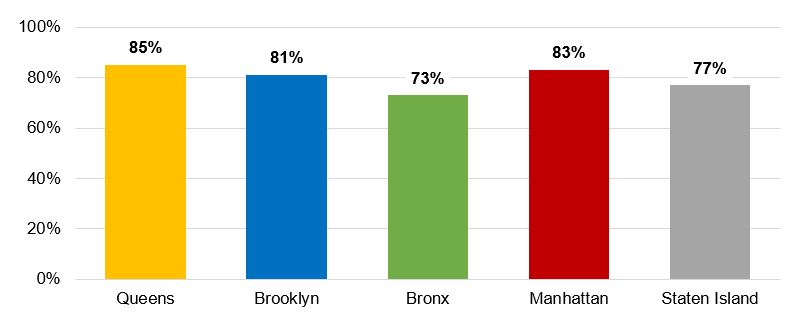

In part because of the investments the City has made in immigrant legal services, the rate of legal representation is relatively high in New York City compared to other jurisdictions across the country. According to TRAC data, about 82 percent of all New York City residents with pending immigration court cases have legal counsel, with representation rates highest for immigrants in Queens and lowest in the Bronx (see Chart 10). However, given the large number of immigration cases involving New York City residents pending an outcome, there are still almost 12,000 New Yorkers with pending cases who do not have legal counsel. In addition, the increase in immigration proceedings under the Trump administration is straining the capacity of legal services providers, already stretched by the large number of cases.[22]

Chart 10: Proportion of Individuals in Immigration Court with Legal Representation by Borough

Source: Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, Individuals in Immigration Court by Their Address, Pending Cases with and without Attorneys.

No New Yorker should be separated from their family or their community simply because they cannot afford legal representation. In order to prevent needless and costly removals and uphold due process for immigrant New Yorkers, the City should commit to working toward universal representation for all immigrants facing removal proceedings, including the detained and non-detained population. Doing so will require expanding existing funding for legal services providers, including through programs like NYIFUP, and also, importantly, removing the carve-out that currently exempts immigrants convicted of certain crimes from receiving legal services through City-funded providers.[23]

Under the criminal carve-out, in place since 2017, the City requires legal service providers to screen potential clients based on certain criminal convictions and then prevents those lawyers from using any City funds to serve those immigrants, even if they may have the ability to prevent deportation, or secure legal status, despite a criminal conviction. The City’s policy in this regard has been criticized by a range of stakeholders, including the New York City Bar Association and Human Rights Watch, under the grounds that all people deserve access to legal counsel when appearing in court, particularly those who may have options for relief from deportation.[24] Currently, legal services to this segment of detained immigrants are funded by an anonymous donation arranged by the City Council of $250,000.[25] For non-detained removal defense clients, and for those seeking affirmative immigration benefits, there is currently no private funding to cover legal services barred by the criminal carve-out. In order to truly achieve universal representation, the City must eliminate this unnecessary and unproductive criminal carve-out and allow legal services providers to serve all clients equally.

2) The City should continue to support the operation of the New York Immigrant Freedom Fund—a project of the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund in collaboration with community-based organizations and legal service providers—to help pay bond for those detained during immigration proceedings.

As with criminal court defendants, some immigrants are afforded the opportunity to post bond and be released from detention during their immigration case. In the criminal context, one of the ways that the City and State help people afford bond is by authorizing the creation of, and helping to finance, charitable bond funds.[26] Under State law, these charitable bond funds are allowed to pay bail for certain people who would otherwise be likely to spend time incarcerated in a City jail. Applying this type of program to detained immigrants has recently been explored both locally and nationally.

Historically, for New York City, immigrants are detained and later released in about 24 percent of cases, while about 1.5 percent of all cases result in detention during the course of the immigration proceeding. National trends, as outlined in two separate reports from TRAC, indicate that immigrants are making more appeals to have bond set and are receiving custody hearings (at which judges decide whether to release detained individuals on bond) at higher rates.[27] Data provided to the Comptroller’s Office by the Executive Office of Immigration Review at the U.S. Department of Justice show that the median bond amount set by immigration judges in New York City has remained relatively steady over the last several years at $7,500, which is 50 percent higher than median bail set in felony cases in criminal court in the city.[28] For many immigrants in the court system, $7,500 is an enormous sum of money, but for some, bond is set even higher. Indeed, through the first half of FY 2018, the most recent data provided, bond amounts ranged from $1,500 to as much as $100,000, with 13 percent of cases over $10,000.[29]

“In the last two years because of the political climate, I’ve had to become more aware of what’s going on in the country because as a recipient of DACA, when Trump came into office attacking DACA, it was very scary. It was very scary to not know what was going to happen with the one thing keeping me safe.”

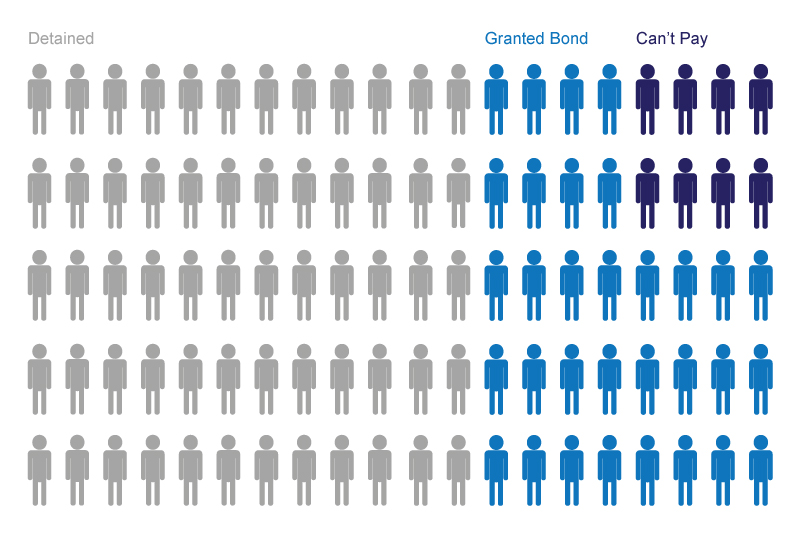

Not all detained immigrants who appeal for bond are granted it. In fact, during the first eight months of FY 2018, according to a TRAC report, only 37.5 percent of detained immigrants in New York City with a hearing were granted bond.[30] Additionally, having a bond set does not necessarily mean that the detained immigrant was able to afford the bond payment. For some immigrants, making a bond payment of many thousands of dollars is unaffordable, as is the case for many defendants in criminal court, and national data suggest that about one in five immigrants who have bond set in their case are ultimately unable to pay that bond (see Chart 11).[31] This may lead to prolonged periods of detention, which, in addition to the trauma associated with being detained, can extend and heighten the hardships experienced by detained immigrants’ family members, colleagues, and neighbors.

Chart 11: What Happens to Detained Immigrants in NYC after Receiving a Bond Decision?

Source: Comptroller’s Office estimate based on data on detained immigrants who receive a decision on bond (“Detained” in figure) between October 2017 and May 2018; TRAC Immigration, “Three-fold Difference in Immigration Bond Amounts by Court Location,” http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/519/ and “What Happens When Individuals are Released on Bond in Immigration Court Proceedings?,” http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/438/.

To help detained immigrants afford bond payments and obtain their release, the City should continue to support the implementation of a local immigration bond fund. The City recently provided a small amount of money to help launch operations for a first-ever New York City immigration bond fund. This fund, the New York Immigrant Freedom Fund (NYIFF), is a project of the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund (BCBF) and came together as a result of their collaborative work with other community-based organizations and legal service providers. The NYIFF is currently operating and will publicly launch, with an online landing page, in early 2019. Going forward, the City should continue to assist and provide additional critical funding to support BCBF’s operational costs for NYIFF. Doing so would meaningfully aid detained immigrants and would deepen the City’s support for local residents impacted by the immigration enforcement system.

3) The State should act to restrict immigration enforcement operations inside New York courthouses.

One of the ways in which ICE agents have become more aggressive under the Trump Administration is by arresting (or seeking to arrest) immigrants who appear in State court for local matters. According to the Immigrant Defense Project, ICE arrests or attempts to arrest inside New York courthouses increased by 1,200 percent in one year, growing from 11 occurrences in 2016 to 144 in 2017, including 97 in New York City alone.[32]

ICE’s predatory targeting of people who appear in State court for any reason is harmful to New York’s justice system. Indeed, this practice has been criticized by a wide range of stakeholders, including the New York City Bar Association, which wrote that ICE’s activities in and near State courthouses “pose[s] a threat to the New York State court system’s ability to ensure access to justice and the state’s overall community-based public safety goals.” [33] Similarly, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has argued that “the presence of [ICE] officers and increased immigration arrests have created deep insecurity and fear among immigrant communities, stopping many from coming to court or even calling police in the first place.” The ACLU goes on to say that “[t]he impact of immigration enforcement at courthouses greatly undermines the security of vulnerable communities and the fundamental right to equal protection under the law, shared by noncitizens and citizens.”[34]

Legislation known as the Protect Our Courts Act has been introduced in both the New York State Senate (Senate bill 425) and Assembly (Assembly bill A2176), which, if enacted, would restrict ICE agents from arresting people in New York State courts unless that ICE officer had a judicial warrant.[35] Currently, ICE agents use administrative warrants that are signed by an ICE official, not a judge, when arresting a person at a courthouse. Under this legislation, however, ICE officers would be required to obtain a warrant that is issued by a federal judge in order to arrest a person, be them a victim, a witness, a defendant, or a visitor in support of a family or community member, in or in the vicinity of a courthouse. This reform would add additional protections for immigrants and ensure that they could appear in court and obtain justice without being arrested for an unrelated civil immigration matter.

Endnotes

[1] New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, Our Immigrant Population Helps Power NYC Economy (January 2017), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/our-immigrant-population-helps-power-nyc-economy/.

[2] Comptroller’s Office analysis of Varick Street Immigration Court Bond Completion data from FY 2009 through the first six months of FY 2018, provided to the Comptroller’s Office by the Executive Office for Immigration Review, U.S. Department of Justice.

[3] U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Policies for the Apprehension, Detention and Removal of Undocumented Immigrants” (November 20, 2014), https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/14_1120_memo_prosecutorial_discretion.pdf; The White House Office of the Press Secretary, “Fact Sheet: Immigration Accountability Executive Action” (November 20, 2014), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2014/11/20/fact-sheet-immigration-accountability-executive-action.

[4] U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “FY 2016 Immigration Removals,” https://www.ice.gov/removal-statistics/2016.

[5] E.O. 13768, “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States” (January 25, 2017), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/01/30/2017-02102/enhancing-public-safety-in-the-interior-of-the-united-states; U.S. Department of Homeland Security, “Enforcement of the Immigration Laws to Serve the National Interest” (February 20, 2017), https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/17_0220_S1_Enforcement-of-the-Immigration-Laws-to-Serve-the-National-Interest.pdf.

[6] Adam Liptak and Michael D. Shear, “Trump’s Travel Ban Is Upheld by Supreme Court” (June 26, 2018), The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/26/us/politics/supreme-court-trump-travel-ban.html.

[7] Dara Lind, “Under Trump, refugee admissions are falling way short – except for Europeans” (September 17, 2018), Vox, https://www.vox.com/2018/9/17/17832912/trump-refugee-news-statistics.

[8] Tal Kopan, “Trump administration to turn away far more asylum seekers at the border under new guidance” (July 12, 2018), CNN, https://www.cnn.com/2018/07/11/politics/border-immigrants-asylum-restrictions/index.html.

[9] Abigail Hauslohner and Andrew Ba Tran, “How Trump is changing the face of legal immigration” (July 2, 2018), The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/how-trump-is-changing-the-face-of-legal-immigration/2018/07/02/477c78b2-65da-11e8-99d2-0d678ec08c2f_story.html?utm_term=.eb7160c1540a.

[10] Salvador Rizzo, “The facts about Trump’s policy of separating families at the border” (June 19, 2018), The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/fact-checker/wp/2018/06/19/the-facts-about-trumps-policy-of-separating-families-at-the-border/?utm_term=.f55238201d26.

[11] Dara Lind, “Judge blocks Trump’s efforts to end Temporary Protected Status for 300,000 immigrants” (October 4, 2018), Vox, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/10/4/17935926/tps-injunction-chen-news.

[12] New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer letter to U.S. Department of Homeland Security (December 10, 2018), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/newsroom/press-releases/comptroller-stringer-urges-department-of-homeland-security-to-rescind-public-charge-rule/.

[13] TRAC Immigration, http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/.

[14] U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, “Fiscal Year 2017 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report” (December 2017), https://www.ice.gov/removal-statistics/2017; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Fiscal Year 2018 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report (December 2018), https://www.ice.gov/features/ERO-2018.

[15] TRAC Immigration, “Latest ICE Data on Detainer Usage Updated Through April 2018,” http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/522/.

[16] Local Law 59 of 2014 restricts NYPD compliance with detainer requests only to cases where the request is accompanied by a warrant from a federal judge and the person to which the request pertains has been convicted of a “violent or serious” crime or listed on a terrorist database. Local Law 28 of 2017 further limited City collaboration with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in relation to immigration enforcement.

[17]New York City Police Department, “Summary of Statistics on ICE Detainers, October 1, 2016 to September 30, 2017,” https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/nypd/downloads/pdf/analysis_and_planning/civil_immigration_detainers/summary-civil-immigration-detainers-2016-2017.pdf

[18] TRAC Immigration, “Immigration Court Cases Now Involve More Long-Time Residents,” http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/508/.

[19] Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs, “Testimony of Commissioner Bitta Mostofi,” New York City Council Oversight Hearing: The Need for Legal Representation in Immigration Court under Trump (December 19, 2018), https://legistar.council.nyc.gov/View.ashx?M=F&ID=6950156&GUID=46892767-280D-468B-91B9-68D4A3440517.

[20] https://www.cityandstateny.com/articles/politics/new-york-city/budget-immigrants-legal-costs.

[21] Vera Institute of Justice, Evaluation of the New York Immigrant Family Unity Project: Assessing the Impact of Legal Representation on Family and Community Unity (November 2017), https://storage.googleapis.com/vera-web-assets/downloads/Publications/new-york-immigrant-family-unity-project-evaluation/legacy_downloads/new-york-immigrant-family-unity-project-evaluation-summary.pdf.

[22] Legal Aid Society, “Testimony Beofre New York City Council’s Committee on Immigration,” New York City Council Oversight Hearing: The Need for Legal Representation in Immigration Court under Trump (December 19, 2018), https://legistar.council.nyc.gov/View.ashx?M=F&ID=6950156&GUID=46892767-280D-468B-91B9-68D4A3440517.

[23] Jeff Coltin, “NYC covers immigrants’ legal costs for those without a criminal conviction” (June 14, 2018), City & State, https://www.cityandstateny.com/articles/politics/new-york-city/budget-immigrants-legal-costs

[24] Human Rights Watch, “New York City: Don’t Exclude Certain Immigrants from Legal Services” (May 31, 2018), https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/05/31/new-york-city-dont-exclude-certain-immigrants-legal-services; New York City Bar Association, The Need to Fund Immigration Legal Services without a Carve-out Based on Certain Convictions (January 31, 2018), https://www.nycbar.org/member-and-career-services/committees/reports-listing/reports/detail/the-need-to-fund-immigration-legal-services-without-a-carve-out-based-on-certain-convictions.

[25] Liz Robbins, “Mayor and City Council Make Deal on Lawyers for Immigrants” (July 31, 2017), The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/31/nyregion/mayor-and-city-council-make-deal-on-lawyers-for-immigrants.html.

[26] Teresa Mathew, “Why New York City Created Its Own Fund to Bail People Out of Jail” (December 1, 2017), CityLab, https://www.citylab.com/equity/2017/12/nyc-bail-fund/546155/.

[27] TRAC Immigration, “Three-fold Difference in Immigration Bond Amounts by Court Location,” http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/519/; TRAC Immigration, “What Happens When Individuals Are Released On Bond in Immigration Court Proceedings?,” http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/438/.

[28] New York City Criminal Justice Agency, 2015 Annual Report, p. 22, http://www.nycja.org/lwdcms/doc-view.php?module=reports&module_id=1577&doc_name=doc; Comptroller’s Office analysis of Varick Street Immigration Court Bond Completion data from FY 2009 through the first six months of FY 2018, provided to the Comptroller’s Office by the Executive Office for Immigration Review, U.S. Department of Justice.

[29] Comptroller’s Office analysis of Varick Street Immigration Court Bond Completion data from FY 2009 through the first six months of FY 2018, provided to the Comptroller’s Office by the Executive Office for Immigration Review, U.S. Department of Justice.

[30] According to TRAC Immigration, between October 2017 and May 2018, 514 cases (of 1,357, or 37.9 percent) were granted bond. TRAC Immigration, “Three-fold Difference in Immigration Bond Amounts by Court Location,” http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/519/.

[31] TRAC Immigration, “What Happens When Individuals Are Released On Bond in Immigration Court Proceedings?,” http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/438/

[32] Immigrant Defense Project, “ICE Courthouse Arrests in New York,” https://www.immigrantdefenseproject.org/wp-content/uploads/IDP_IceCourthouseArrests_Infographic-FINAL.png.

[33] New York City Bar Association, “Recommendations Regarding Federal Immigration Enforcement in New York State Courthouses,” https://s3.amazonaws.com/documents.nycbar.org/files/2017291-ICEcourthouse.pdf.

[34] ACLU, “Freezing out justice: How immigration arrests at courthouses are undermining the justice system,” https://www.aclu.org/issues/immigrants-rights/ice-and-border-patrol-abuses/freezing-out-justice?redirect=issues/ice-courthouse.

[35] Senate Bill S425, https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2019/S425; Assembly Bill A2176, https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2019/a2176.