The Public Cost of Private Bail: A Proposal to Ban Bail Bonds in NYC

Executive Summary

A basic principle of the American justice system is that all people are innocent until proven guilty, and that defendants should not be unnecessarily punished or detained before a finding of guilt. However, the bail system in New York City subjects tens of thousands of people each year to punitive personal and financial costs prior to conviction (or exoneration).

In general, after a person is arrested and charged with a crime in New York City, they appear in court and face a judge, who decides whether to release the accused, set bail, or hold the person in custody. In many cases, judges in New York City release the defendant on a simple promise to appear for their next court date. However, when a judge decides to impose money bail conditions, the defendant is likely to spend at least some time in jail – often for the sole reason that they do not have the money needed to post bail immediately and must raise it from friends and family, or must navigate the slow, inefficient commercial bail system. At a time when the City is focused on reducing the jail population in order to close the correctional facilities on Rikers Island, ending a system that results in the unnecessary, unproductive, and expensive detention of people prior to a conviction must be prioritized.

In his 2018 State of the State address, Governor Andrew Cuomo endorsed eliminating money bail for all persons charged with a misdemeanor or non-violent felony, while in April 2017 the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform – led by former Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman – recommended prohibiting money bail entirely. These long-term visions are commendable and would end a system that conditions New Yorkers’ freedom on their financial capacity. Moving toward this long-term goal should be a high priority for both New York City and New York State.

However, achieving this vision will require substantial planning and new funding to ensure that the partial or full elimination of bail does not unintentionally result in a larger pretrial jail population. Without viable alternatives to bail, such as supervised release programs, more defendants, rather than less, could face time in jail as they await the conclusion of their case.

As New York moves toward a more equitable criminal justice system, in the near term the City should immediately address one of the most costly and punitive aspects of the justice system: commercial bail bonds. The reliance on exploitative and expensive commercial bail bonds, which have played a growing role in the city’s bail system, has been one of the most prominent drivers of inequities in the system.

With that goal in mind, this report from New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer documents the role that money bail plays in New York City’s criminal justice system and calls for the immediate elimination of commercial bail bonds. The growing role of commercial bonds in the City’s bail system has not been previously well understood. Specifically, this report finds that:

1. Each year, tens of thousands of New Yorkers spend time in City jails simply because they cannot afford to pay bail.

When a person is arrested in New York City and a judge decides to set bail, that person is likely to spend time in jail before making a bail payment. This is the case even when bail is set at relatively low amounts. In fact, in fiscal year (FY) 2017 about 70 percent of people who paid bail were incarcerated for at least some amount of time, in part because the process of posting bail is difficult and time consuming.

More specifically, in FY 2017, there were about 33,000 admissions to New York City jails of people who were unable to pay bail at their first court hearing. However, in nearly 15,000 of these cases, the person was subsequently released after making bail; in more than half of these latter cases, the person made a bail payment and was released within three days. These short jail stays serve little public safety purpose, if any, and come at great expense to taxpayers and the individuals impacted. This group of detainees, who could have avoided jail if bail had been paid at arraignment, collectively spent 119,030 days in jail in the fiscal year.

2. This system imposes a significant cost on the accused, their families, their communities, and all City taxpayers.

The Comptroller’s Office estimates that the marginal cost to the City to detain people pretrial who are unable to pay bail is about $100 million annually, $10 million of which is associated with incarcerating those who ultimately pay bail and are released back into society before their case concludes. In addition, research has shown that people incarcerated before their trial face other costs that include lost jobs, wages, and time with their families, resulting in long-term reductions in their families’ stability and economic mobility. Based on an estimate of the average wages of people in custody, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that detainees in City jails lose about $28 million in wages every year because they have not posted bail and are incarcerated. Pretrial incarceration has further been shown to increase the likelihood of a conviction, particularly from guilty pleas.

3. The commercial bail bond industry plays a growing and costly role in the city’s bail system.

Even as crime and arrests have fallen, the use of private bail bond agents has been growing and now accounts for more than half of all bail postings. In FY 2017, New York City defendants’ and their families and friends posted more than 12,300 private bail bonds, with a total bond value of $268 million. The number of private bail bond postings has grown 12 percent in the last two years, as the total value of bond postings rose 18 percent.

The high and growing use of commercial bonds exacerbates the already punitive nature of the bail system. Unlike bail payments made directly to the courts, including cash bail and other alternative forms of bail, premiums paid to private bail bond companies are generally nonrefundable at the conclusion of the case, even if the person appears at all court hearings. Consequently, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that last year the private bail bond industry extracted between $16 million and $27 million in nonrefundable fees from people arrested in New York City and their family and friends. This sum represents a sizeable transfer of wealth from already low-income communities to the pockets of opportunistic bail bond agents.

Evidence further suggests that some companies collect fees above the legally permitted amount, while also failing to return collateral as required under contract and imposing other restrictions on defendants. In addition, evidence suggests that private bail bond companies may fail to file bonds with the court in a timely fashion, leading to additional and unnecessary delays in a defendant’s release, even after a contract has been signed and all the required fees have been paid and collateral has been posted.

In many respects, New York City’s pretrial justice system treats criminal defendants more fairly than other large cities and the nation as a whole, with relatively high rates of pretrial release and lower bail amounts. Yet, for the tens of thousands of people who are subject to bail conditions every year, the City must make significant strides to ensure no one is unnecessarily detained and punished simply because they are too poor or because the process of posting bail is too onerous and predatory.

With that long-term goal in mind, in order to build a pretrial justice system that relies less on money and more on fairer, faster, more humane, and less costly forms of release, this report recommends that the use of commercial bail bonds in New York City be immediately eliminated. Notably, commercial bail is already entirely banned in four U.S. states and in all other nations of the world, with the exception of the Philippines, and is on the decline in states that have recently implemented bail reforms.

Accomplishing this goal could be done without changing state law, but would be more securely realized through state legislation. Under the state’s existing bail law, prosecutors and judges are already authorized to use alternatives to commercial bail bonds, including less-costly forms of bail such as unsecured and partially secured bonds. These forms of bail allow people to execute bonds by signing affidavits and posting refundable fees and/or collateral with the courts, thereby avoiding the potential for abuse by private bail bond companies and expediting the process of release. Despite being added to state law decades ago, however, these alternative forms of bail are infrequently used today. For that reason, it may be necessary to change the state’s bail law to completely accomplish this goal.

In addition, over the longer term, New York City and State should reduce the use of money bail and shift to other, non-cash forms of bail to ensure a defendant’s appearance at trial, as Governor Cuomo and the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform have already recommended.

Across the country, there is a growing movement to reform bail laws and move to a fairer, more just, and less expensive criminal justice system. New York City’s existing reform efforts have moved the City in the right direction, but more sweeping actions like the abolition of commercial bail bonds are needed.

The Role of Bail in Pretrial Detention

In the U.S. criminal justice system, bail is used as a means of securing a defendant’s freedom before trial while also ensuring that the accused appears in court. After a person is arrested, a judge generally determines whether that person can be released back into society, or if that person should be held in jail – or remanded – until trial.[1] In some cases, a judge will release a person simply on the basis of that individual’s promise to return for trial, which is called “released on recognizance.” Alternatively, a judge can decide to release the person subject to certain non-financial conditions that could include regular check-ins with a supervisor or other forms of monitoring. In other cases, however, a judge may condition release on a financial payment, which could include a cash or bond payment to the court from the defendant, or from a person on behalf of the defendant, known as a “surety.” In this report, all forms of bail requiring a financial payment are referred to as “money bail.” While the U.S. Constitution protects defendants from “excessive bail,” and state laws outline specific factors to be considered, in practice judges in most states maintain significant discretion in setting money bail.[2]

In recent years, many advocates, policymakers, researchers, and others have raised concerns that the use of money bail results in too many people being incarcerated before trial, in many cases simply because that person cannot afford to pay bail, not because that person is unlikely to return to court for trial or poses a public safety risk.[3] Indeed, national data confirms that over six in 10 persons incarcerated in local jails in the U.S. are pretrial detainees, and that pretrial detainees have accounted for 95 percent of growth in the jail population over the last twenty years.[4] Moreover, a significant percentage of these detainees would have been released had they been able to afford bail. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, in 2009 nine out of 10 felony defendants detained before trial who had bail set would have been released had they been able to pay.[5]

New York City has not been immune from these national trends. As discussed in more detail below, the use of bail conditions in pretrial releases led to nearly 33,000 admissions to City jails in the last fiscal year alone. At the end of June 2017, more than one-third of the City’s jail population, or 3,340 people, were detained because they had not posted bail.

The Bail Process in New York City

In New York, judges must adhere to state laws in determining if a person is eligible for pretrial release, but they have wide discretion in deciding if bail should be used as a condition for release and in setting the bail amount. In contrast to many other states’ practices, New York State law does not allow judges to consider public safety in the release or bail decision.[6] Rather, in determining conditions for release, judges are required by New York State law to consider the person’s flight risk by weighing factors such as their character, financial resources, ties to family and community, and criminal record.[7] Judges are also instructed to consider the weight of evidence against the defendant and the sentence that may be imposed, as well as whether the person has been charged with domestic violence. Despite the guidelines in state law, in practice, judges in New York City rely heavily on prosecutors’ bail recommendations when setting bail, and these recommendations generally directly correspond to the severity of the charges.[8]

Overall, the vast majority of New York City defendants return to court, and among the few who miss a court date, most return within 30 days. Based on the most recent available data, in only 4 percent of felony cases and 7 percent of non-felony cases, the defendant did not appear within 30 days.[9]

If a judge sets financial conditions for release, they must either specify a dollar amount, without dictating the form of bail, or specify at least two options of payment for the defendant. In doing so, that judge may choose from nine different types of payment, including cash, insurance bond, credit card, and other types of bond options with the courts, some of which do not require upfront financial payments. (See sidebar on the nine bail options.) However, when bail is set, judges in New York City almost always rely on cash bail and insurance bonds instead of other options that are less financially burdensome to the defendant.[10] Typically, the cash bail amount is set at a significantly lower amount than the bond option, but this is not required by law.

Importantly, in some respects, New York City is a national leader in its use of less restrictive pretrial practices. About 70 percent of defendants in New York City are released with a simple promise to return to court, and release rates are even higher for low-level criminal charges.[11] While only 36 percent of defendants charged with a Class A or B felony (the most serious crimes) were released on recognizance in 2015, fully 80 percent of Class A misdemeanor cases (the most severe misdemeanors) and 90 percent of other misdemeanor cases obtained release without bail conditions. As a result of high rates of release without conditions, a smaller percentage of defendants are detained pretrial and rates of pretrial detention are lower in New York City compared with other major metropolitan areas.[12]

In addition, when bail is set, it is typically set at lower amounts in New York City than across the country. The most recent analysis from the U.S. Department of Justice found that in the U.S., the median bail amount set for felony cases in 2009 was $10,000. Comparatively, the median bail set in New York City in 2015 was $5,000 for felony cases and $1,000 for non-felony cases.[13] In stark contrast to these levels, median bail is $40,000 in Chicago’s Cook County and $50,000 in the State of California.[14]

In recent decades, impressive strides have been made in reducing the number of people entering jail overall, including those entering pretrial. Indeed, according to research from the Misdemeanor Justice Project at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, between 1995 and 2015 the number of annual admissions to New York City jails fell from over 120,000 to under 65,000 (46.9 percent), and the average daily jail population dropped from over 18,000 to under 10,000 (47.1 percent).[15] Consistent with this trend, the number of pretrial admissions has similarly fallen by 48.6 percent during this same time (from over 97,000 admissions in 1995 to under 50,000 admissions in 2015).[16]

Nevertheless, there remains ample room for improvement. As described in more detail below, in FY 2017 thousands of New York City residents were incarcerated simply because they were unable to afford bail.

| Judges May Set 9 Types of Bail in New York: |

|---|

|

Pretrial Detainees Account for a Significant Percentage of the City’s Incarcerated Population

According to an analysis of data provided to the Comptroller’s Office by the New York City Department of Correction (DOC), in FY 2017 there were 48,250 admissions to New York City’s jails of people who were awaiting trial.[17] While the total number of pretrial admissions has fallen 14 percent from FY 2015 levels, pretrial detainees nonetheless accounted for 83 percent of all admissions during the last fiscal year. Alternatively, if viewed as a one-day snapshot, pretrial detainees represented 68 percent of the City’s jail population as of June 29, 2017. While the majority of those detained pretrial were charged with a felony, more than one-third were detained after being charged with a misdemeanor.

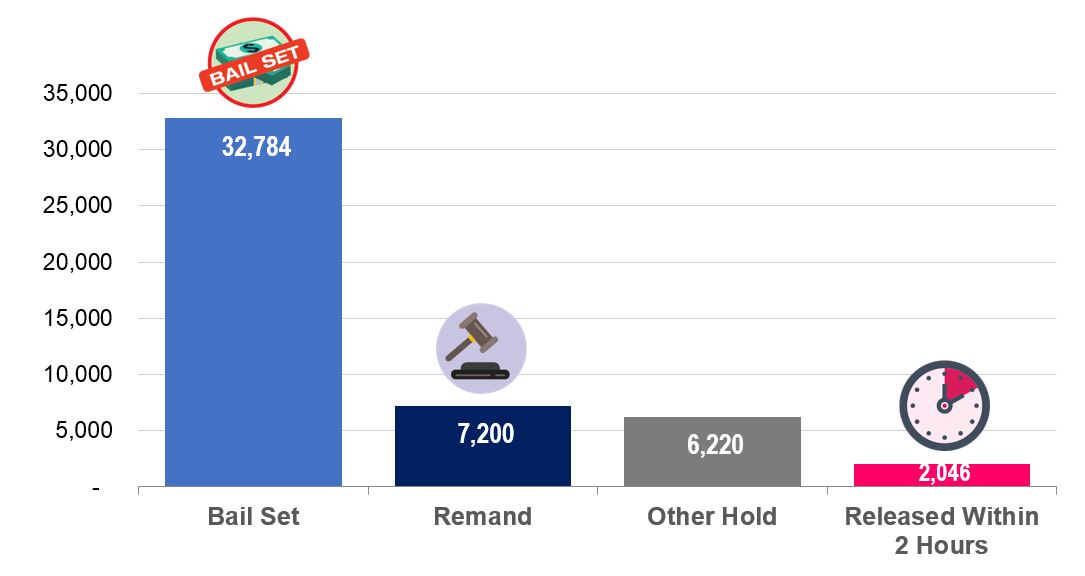

Of the 48,250 pretrial detainee admissions last year, 15 percent were remanded to jail, guaranteeing their detention until at least the conclusion of their case. Another 13 percent entered jail with an outstanding court warrant or administrative hold, such as unpaid fines or another open case, which may have eliminated or complicated the possibility of release, and 4 percent were released within two hours of admission. (See Figure 1.) Bail was set in the other 68 percent of admissions (equal to 32,784 cases), meaning that jail could have been avoided if bail had been posted at arraignment.[18] These 32,784 admissions represent the number of times in FY 2017 that a person was incarcerated in a City jail as a result of being unable to pay bail at arraignment.

Figure 1: Pretrial Detainees Admitted in FY 2017

Source: New York City Comptroller’s Office analysis of New York City Department of Correction data.

Data shows that over 50 percent of the people incarcerated for this reason were Black, while 33 percent were Hispanic, and 9 percent were White. In addition, over 40 percent of these detainees were under the age of 30, including 3,570 admissions of persons younger than 21 years old. Close to one-fifth were diagnosed with a mental illness.

In addition, many of the people admitted into custody before trial had their bail bond amount set at relatively low levels, suggesting that even small financial payments can be difficult for many defendants and their families.[19] Indeed, in nearly one-third of admissions, or 10,257 admissions, bail bond amounts were set at $2,000 or less, which under state law would require an upfront payment of $200 to a bail bond provider in order to be released.

Many Pretrial Detainees Who Are Initially Unable to Pay Bail Are Eventually Released, Often within Days

In general, relatively few people can afford to pay bail at arraignment in New York City, regardless of the amount of bail that is set. In fact, about 70 percent of all people who paid bail in FY 2017 were incarcerated for some period of time before making bail.[20] Of felony cases with bail set, 91 percent were unable to post bail at arraignment in calendar year 2015, while 87 percent of defendants in non-felony cases were also unable to do so, despite lower bail amounts.[21] Similarly, of cases with bail set at amounts below $500, 77 percent of those charged with felonies and 84 percent of those charged with non-felonies did not make bail at arraignment. The strikingly low rates of people able to post bail at arraignment, and therefore avoid time in jail, raise serious concerns about the financial and logistical barriers to paying bail and the subsequent personal and public costs.

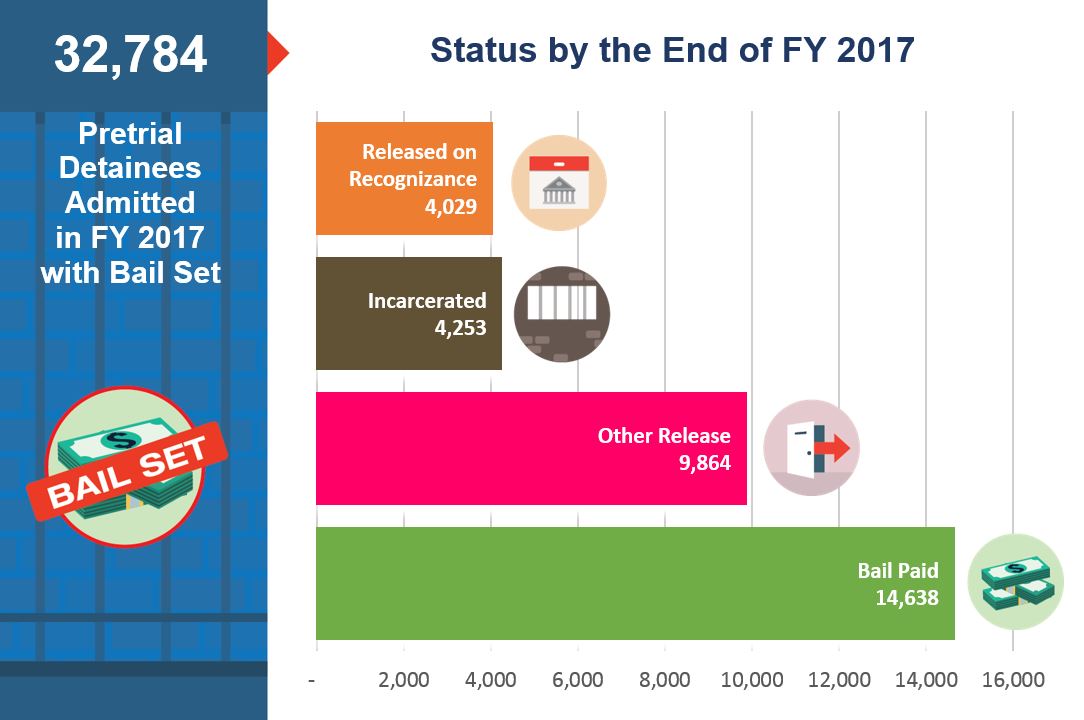

While most people are unable to make bail at arraignment, many do eventually make bail after being admitted into custody and are released. Indeed, as shown in Figure 2, of the 32,784 admissions in FY 2017 resulting from an inability to pay bail, by the end of the fiscal year bail had been paid in 14,638 cases, or about 45 percent of the time. This group of detainees, who could have avoided jail if bail had been paid at arraignment, collectively spent 119,030 days in jail and accounted for 30 percent of all pretrial detainee admissions in FY 2017. For most people, this period of incarceration followed a wait of up to 24 hours in a police holding cell before being brought before an arraignment judge.

Figure 2: Pretrial Detainees Admitted With Bail Set in FY 2017 by Discharge Status at End of FY 2017

Note: “Other Release” includes discharges for time served, expired sentences, transfers to state prison, charges dismissed, and acquittals. In 841 cases, the person was transferred to state prison.

Source: New York City Comptroller’s Office analysis of New York City Department of Correction data.

In some cases, people who are admitted into custody with bail set are released without paying bail. In FY 2017, in another 8 percent of pretrial admissions, or more than 4,000 times during the year, the person was initially admitted due to an inability to pay bail but was eventually released without any conditions following a subsequent court hearing. Another fifth of detainees who were admitted during FY 2017 with pretrial bail conditions were released for other reasons, including the completion of their case or a transfer to state prison or another jurisdiction. The remainder remained incarcerated as of the end of the year.

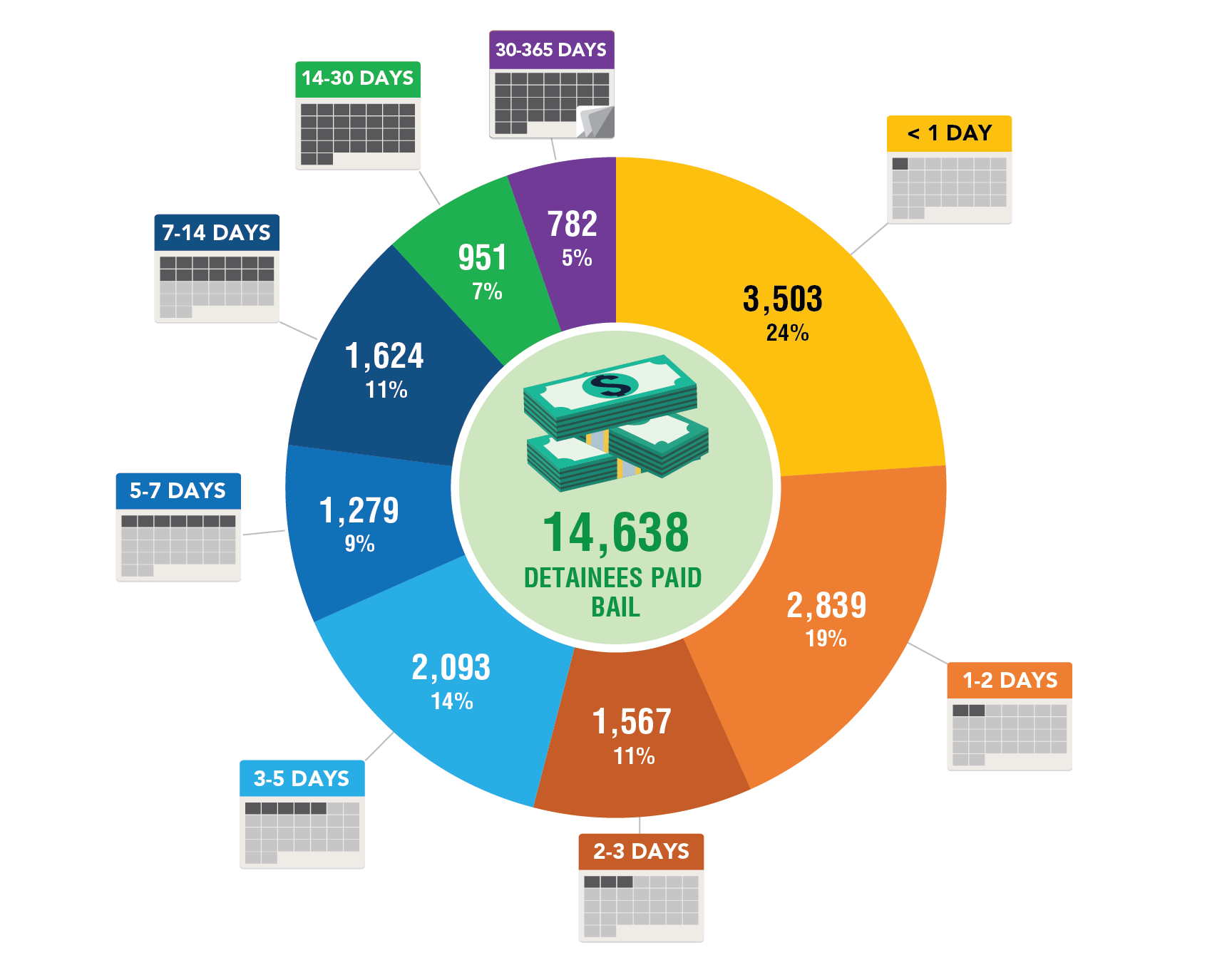

In addition, as shown in Figure 3, many of the people who are admitted after being unable to immediately make bail actually go on to pay bail relatively quickly. In fact, 24 percent of those who were able to post bail in FY 2017 after being incarcerated did so within the first 24 hours. Additionally, in 11,281 cases, or more than one-third of all pretrial admissions in which bail was set in FY 2017, the person was discharged from custody within one week as a result of paying bail. Overall, in more than half of cases in which bail was posted, people left within three days. Such short jail stays serve little public purpose, either in terms of public safety or ensuring defendants do not flee, even though incarceration involves a great expense for both taxpayers and the individuals detained.

Figure 3: Length of Stay Before Posting Bail for Pretrial Detainees Admitted with Bail Set in FY 2017

Note: Includes only detainees with bail set at the time of jail admission. Excludes detainees with a warrant or other hold, including arrests due to a warrant and bail amounts equal to $25 or less, which indicate an administrative hold; detainees discharged within two hours; and detainees remanded to jail.

Source: New York City Comptroller’s Office analysis of New York City Department of Correction data.

Because many detainees with bail set exit jail quickly, they account for a smaller, but still substantial, share of the daily jail population. As of June 29, 2017, New York City jails housed 3,340 people who were detained due to an inability to post bail, accounting for 36 percent of the daily population. Some of these people likely went on to post bail within the next few days, as others arrived in subsequent days.

Some Detainees Are Unable to Make Bail Payments, Even When Bail Is Set at Relatively Low Levels

The actual upfront cost of posting a commercial bail bond is far less than the total value of the bond. Under state law, the maximum upfront fees range from 6 percent to 10 percent of the value. But even those fees can be a burden for many New York City detainees.

On any given day, New York City incarcerates more than 3,000 people who could be released if they were able to post bail. Typically, about 500 of those detained people could be released by posting a bail bond valued at less than $5,000, which typically requires an upfront payment of no more than $460 to the bail bond provider. That number includes over 200 people who could be released by posting a bond valued under $2,000, requiring no more than $200 cash up front. Additionally, more than 900 people could be released with a $10,000 bond or less. (Table 1.) As discussed in more detail below, some companies may charge additional, illegal fees, as well as legally requiring the deposit of collateral. While the upfront fees are nonrefundable, collateral should be returned if the client appears at all court hearings and does not break any stipulation of the bail bond contract.

Table 1: New York City Daily Incarcerated Population by Bail Bond Amount

| Number | Share of Total Population | |

| Bail Bond Set | 3,340 | 36% |

| Below $2,000 | 226 | 2% |

| $2,000-$4,999 | 283 | 3% |

| $5,000-$9,999 | 405 | 4% |

| $10,000-$19,999 | 482 | 5% |

| $20,000-$49,999 | 573 | 6% |

| $50,000-$99,999 | 521 | 6% |

| $100,000-$199,999 | 413 | 4% |

| $200,000 or More | 437 | 5% |

| City Sentenced, No Bail, or Other Hold | 5,872 | 64% |

| Total | 9,212 | 100% |

Note: Population with bail set includes only persons with bail set at the time of jail admission, and excludes detainees with a warrant or other hold, including arrests due to a warrant and bail amounts equal to $25 or less, which indicate an administrative hold.

Source: New York City Comptroller’s Office analysis of New York City Department of Correction data.

Based on bail bond amounts set at the time of admission and maximum fees allowed under state law, as of the end of June 2017, more than 19 percent of the City’s jail population could be released with an upfront, nonrefundable fee of $2,000 or less. (See Table 2.) About 13 percent could be released with a fee of $1,000 or less, and 8 percent could be released with a fee of $500 or less. As previously noted, some of these people were likely released in the next few days after completing the process of posting bail, while others remained incarcerated until the completion of their case.

Table 2: New York City Daily Incarcerated Population by Nonrefundable Bail Bond Fee Enabling Release (As of June 29, 2017)

| Number | Share of Total Population | |

| Maximum Bond Fee | 3,340 | 36% |

| $500 or Less | 768 | 8% |

| $501-$1,000 | 446 | 5% |

| $1,001-$2,000 | 578 | 6% |

| $2,001-$5,000 | 678 | 7% |

| $5,001-$10,000 | 422 | 5% |

| More than $10,000 | 448 | 5% |

| City Sentenced, No Bail, or Other Hold | 5,872 | 64% |

| Total | 9,212 | 100% |

Note: Population with bail set includes only persons with bail set at the time of jail admission, and excludes detainees with a warrant or other hold, including arrests due to a warrant and bail amounts equal to $25 or less, which indicate an administrative hold.

Source: New York City Comptroller’s Office analysis of New York City Department of Correction data.

The Costs of Pretrial Detention

In addition to the human costs that people arrested in New York City experience while in jail, New York City faces sizeable fiscal costs associated with detaining people who are unable to pay bail. Moreover, spending time in jail imposes additional personal and financial costs for the detainee that also impacts their family, their community, and the character of the city as a whole. As discussed in more detail below, these costs could be reduced if fewer people were detained as a result of being unable to make bail payments, particularly in the cases of people who are detained for relatively short periods of time while their family or friends work to collect enough funds to post nominal bail amounts or waiting for a bond to be approved.

Taxpayer Costs

The detention of people who have yet to be found guilty of a crime but are nonetheless incarcerated because they are unable to pay bail, particularly for extremely short periods of time at low bail amounts, imposes an unnecessary and significant cost on taxpayers.

The City spent $2.6 billion in FY 2017 to house an average of 9,500 people on a daily basis, or an average daily cost of about $740 per person, taking into account fringe and other benefits paid to correctional staff, as well as services provided by the City’s Department of Correction (DOC) and other agencies.[22] These costs include average daily costs of $79 per person on medical services provided by Health+Hospitals and the City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, but exclude additional legacy costs from capital expenditures and lawsuit settlements.[23]

Due to the relatively fixed cost structure of DOC, most of these costs cannot be reduced in the short-term, even if the jail population falls. In fact, as the average daily population has decreased by 23 percent in the last five years, the total DOC budget has grown by 27 percent.[24] The Department’s inability to curb spending stems from several factors. In recent years, climbing violence and legal mandates have prompted investments in new programs, staff training, and security measures. DOC must also continually operate full facilities for certain special populations, such as young adults and women. Additionally, for security reasons DOC must maintain officers at specific locations, known as “fixed posts.” For these reasons, DOC can only achieve significant savings if an entire housing wing is closed, which the City’s Independent Budget Office (IBO) has reported would require reducing the average daily population by 100 or more.[25]

IBO estimates that if population reductions are large enough to enable closing a housing unit, the City could save $81 per day per person.[26] Using this estimate of marginal savings, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that it costs the City about $100 million annually to detain people pretrial solely because they are unable to pay bail. Of that sum, $10 million is associated with incarcerating those who ultimately pay bail and are released back into society. These costs represent the amount of money that could be saved if people were not detained for the sole reason that they lacked the money to secure their own release.

In addition, while population declines may not immediately result in large cost savings, fewer admissions and detainees would free up staff time for other productive services. For example, the intake process can last up to 16 hours, consuming enormous staff time.[27] Similarly, each person who enters the jail system must undergo an extensive medical exam to screen for communicable diseases, substance abuse, and mental health disorders, among other medical conditions. Each medical screening requires an average of four hours.[28] To provide such screenings for the nearly 15,000 detainees who entered jail in FY 2017 and eventually posted bail, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that the City had to maintain at least 35 full-time medical personnel.[29] These medical workers could otherwise be engaged providing more comprehensive and timelier services to other incarcerated individuals. Importantly, these required screenings and additional work required to admit a person into custody make the cost of admitting a person for a relatively short period of time particularly costly.

City jails also routinely rely on correction officer overtime to staff jails and respond to incidents. In FY 2017, uniformed overtime totaled $240 million at DOC, or $22,130 per correction officer.[30] Overtime is an expensive way to manage staffing needs and exposes officers to fatigue and potentially unsafe working conditions. A smaller jail population could facilitate reductions in overtime use.

Personal Costs

In addition, incarceration results in numerous negative impacts on the detained, that person’s family, and their community. For instance, research has documented how pretrial incarceration can result in negative economic consequences for the detained person and their family, including lost wages, lost jobs, lost property, and family disruptions.[31] According to the New York City Criminal Justice Agency, about 40 percent of defendants held on bail are employed, with median earnings of $400 per week, or $20,800 per year.[32] Given this average salary, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that detainees lose about $28 million in wages every year because they have not posted bail and are incarcerated.[33] The full extent of wage losses due to incarceration is likely far larger, as many detainees will also lose their jobs following an arrest or if they do not show up to work.

Incarceration has also been linked to lower lifetime earnings. Specifically, research from the Pew Charitable Trusts found that people who have been incarcerated experience annual earnings reductions of 40 percent and lose as much as nine weeks of employment annually.[34] In addition to lost income, pretrial detainees lose property or have their property stolen at relatively high rates, creating additional economic hardships.[35]

These negative impacts of incarceration extend across generations. In addition to the negative behavioral and mental health impacts of losing a parent to incarceration, children of people who are detained have been found to be more likely to drop out of school, depriving them of future earnings, and also are more likely to engage in future criminal activity.[36] As education levels and parental income are indications of a child’s future economic mobility, the impacts of incarceration are inter-generational, making it even harder for low-income children to escape poverty.[37]

Detainees, and their families and friends, also face extra costs and fees while the person is incarcerated. In FY 2016, family and friends of persons under custody in New York City jails deposited more than $17 million to jail commissary accounts.[38] These funds allow people in jail to buy food and toiletries, pay for phone calls, or post bail. According to the website of the private company that provides phone service to DOC detainees, local calls cost $0.50 for the first minute and $0.05 for each additional minute, while long distance calls cost $0.21 cents per minute.[39]

Private money transfer companies operating in New York City jails collected an additional $2 million in fees from relatives and friends that used the phone, internet, or kiosks to deposit commissary funds. In 2016, the New York City Public Advocate introduced a bill to limit these fees, which range from $4.95 for depositing up to $20 by phone, to $11.95 for phone deposits between $200 and $300.[40]

The physical isolation of Rikers Island, which is accessible by only one bus line and a narrow bridge, further adds personal costs to family members who want to see their loved ones. Long waits and security procedures at the visitors’ center can force families, including children, to spend all day waiting for a few, brief moments together.[41] Not surprisingly, the DOC reports higher rates of visitors at its borough-based facilities than its Rikers Island facilities.[42]

Along with these economic costs, there are numerous other negatives effects associated with pretrial incarceration. As has been well documented in the case of the New York City jail facilities on Rikers Island, the conditions in detention facilities are horrific, with high rates of violence, overcrowding, and unsanitary conditions.[43] High jail populations often combine with lack of healthcare access, resulting in the prevalence not only of bacterial and infectious diseases but of untreated mental illness.[44]

Evidence also indicates that, compared to those released within 24 hours, those detained during the pretrial period were more susceptible to re-arrest before trial, conviction, and recidivism.[45] The New York City Center for Court Innovation found that, after controlling for other variables, pretrial detention increased the likelihood of a criminal conviction by 10 percentage points for misdemeanor charges and 27 percentage points for felonies.[46] The study further found that pretrial detention increases the likelihood of a jail sentence by 40 percentage points for those who are convicted of a misdemeanor and by 5 percentage points in felony cases. Similarly, a 2017 study authored by professors at the University of Pennsylvania found that “pretrial detention causally increases a defendant’s chance of conviction, as well as the likely sentence length.”[47] Evaluations of supervised release programs in Brooklyn and Manhattan also concluded that a defendant’s liberty while awaiting trial reduced the likelihood of a guilty verdict.[48]

Additionally, research from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation found that, compared to those held for less than 24 hours, low-risk defendants held for two to three days were 17 percent more likely to commit another crime within two years, and defendants held for eight to 14 days were 51 percent more likely to recidivate.[49] A 2016 study of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh further found the assignment of bail resulted in a 6 to 9 percent increase in recidivism rates.[50]

Pretrial detention has also been shown to increase the likelihood of guilty pleas, regardless of innocence or guilt, in part because defendants unable to afford bail who are incarcerated pretrial have little ability to reach more favorable plea agreements or leave custody without pleading guilty.[51] A 2016 study authored by faculty at Princeton, Stanford Law School, and Harvard Law School documented that those detained pretrial were more likely to plead guilty, and as a result, have less connection with the formal labor market, meaning less income and less likelihood of receiving benefits tied to work including the Earned Income Tax Credit following release.[52]

Those who eventually post bail are subject to additional costs. If a defendant, or her family or friends, pay cash bail, those funds are inaccessible for the duration of the case and often remain inaccessible for several months afterward. While the City aims to return cash bail within eight weeks if the person has returned to court at all scheduled hearings, the process can take many more months or even years. The Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, which opened a charitable bail fund in April 2015, reports that the receipt of cash bail following the conclusion of a case often significantly exceeds eight weeks.[53] While in 17 percent of cases in which funds had been returned, the funds were received in less than two weeks, in 12 percent of cases, the process took more than six months. Additionally, as of September 2017, the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund reported 45 instances in which cases had been disposed more than one year ago, but bail funds had not yet been returned. A 2014 New York State Comptroller audit similarly uncovered instances in which bail funds were not properly distributed in accordance with court orders.[54]

For defendants who enlist the assistance of a private bail bond agent or company, the personal costs are even greater and include nonrefundable fees, additional time to process bond payments, and potentially the loss of collateral. As discussed below, private bail bonds, and their associated costs, are a growing component of New York City’s bail payment system.

The Role of Commercial Bail Bonds

A growing number of defendants in New York City make bail by using private insurance bonds issued by a bail bond agent or company. When using a bail bond, a defendant (or a person on behalf of the defendant) signs a contract with a bail bond provider, at which point that provider then posts bail on behalf of the defendant. The bail bond provider becomes liable for the full amount of bail if the defendant fails to appear; however, bail bond agents do not consistently pay the courts, and typically, providers indemnify themselves against the full liability.[55] Most bail bond contracts specify that if the defendant does not attend all court dates, the client will forfeit collateral and/or be subject to additional financial charges.

Unlike bail paid directly to the court in cash, however, state law stipulates that a portion of the funds paid to a bail bond provider, also known as the premium or fee, may be retained by the provider, regardless of the disposition of the case and even if the defendant appears at all court hearings. This is the case because conceptually the premium compensates the bail bond provider for the risk incurred by posting a bond on a client’s behalf. Under state law, this premium is limited to 10 percent for bail amounts under $3,000. For any bail amount over $3,000, the provider may collect an additional 8 percent for amounts above $3,000 but below $10,000, and another 6 percent for amounts in excess of $10,000.[56] State law explicitly states that agents cannot “charge or receive, directly or indirectly, any greater compensation for making a deposit or giving bail.”[57] If the defendant’s family or friends cannot pay the full fee up front, additional costs may be incurred to finance a loan.

In addition to this premium, bail bond companies are also allowed to demand that defendants or their families post unlimited amounts of collateral to support the issuance of a bond. Through a bond contract, these private actors may also impose restrictions on defendants’ personal liberties, such as curfews or required meetings. A violation of the contract can be grounds for forfeiting collateral, as well as re-arrest and a return to jail.[58] Bail bond companies may also refuse to provide their services and typically do so for smaller bond amounts.

Despite the large role of private bail bond providers in determining a person’s pretrial freedom, the industry is the subject of frequent complaints. In his 2016 State of the State speech, Governor Andrew Cuomo called for reforming bail bond practices, noting that the industry is subject to “little regulation” with some “bad actors” engaging in “predatory pricing and contracting practices” that have a “disproportionate negative impact on low-income people.”[59]

Private Bail Bonds Play a Growing Role in New York City’s Bail System

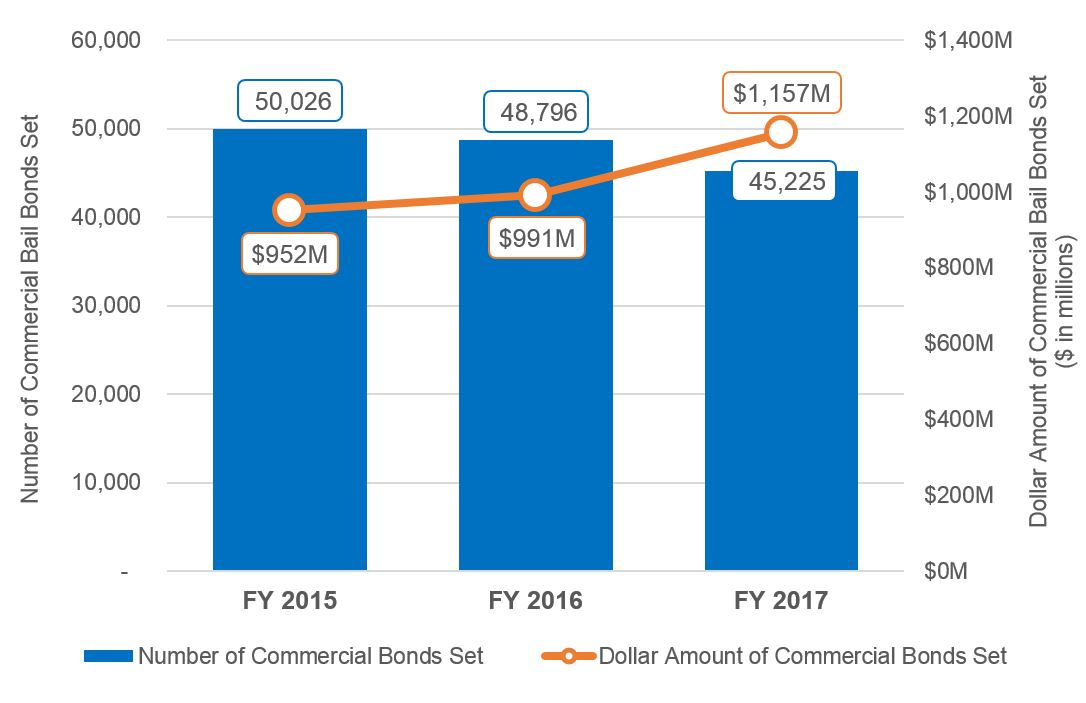

Based on data provided to the Comptroller’s Office by the State’s Unified Court System, judges set bail with a bail bond option in 45,225 cases in FY 2017, as shown in Figure 4. While this is down about 10 percent from FY 2015, the total dollar amount of bail bonds set has risen in each of the last three years to over $1.1 billion in FY 2017. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4: Number and Dollar Amount of Commercial Bail Bonds Set in New York City, FY 2015 to FY 2017

Source: New York City Comptroller’s Office analysis of data provided by the New York State Unified Court System.

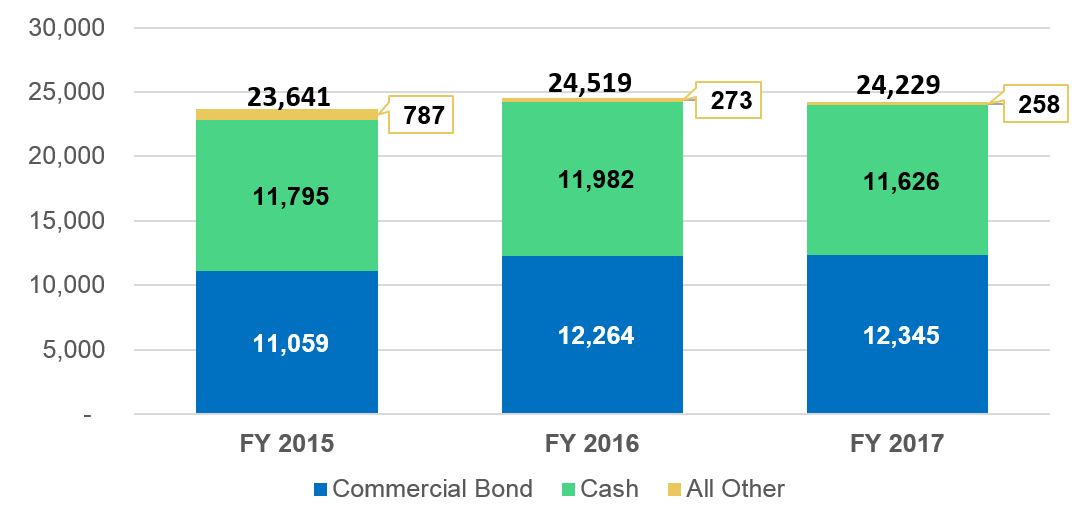

Court data shows that while bail bonds are being set in fewer cases each year, a rising number of New Yorkers are using private bail bonds to make bail. As shown in Figure 5, in both FY 2016 and FY 2017 private bail bonds accounted for more than half of all bail postings in New York City.

Figure 5: Number of Bail Postings by Type

Source: New York City Comptroller’s Office analysis of data provided by the New York State Unified Court System.

While the number of cash bail postings fell between FY 2016 and FY 2017, bail bond postings increased to 12,345 instances. Since FY 2015, the use of bail bonds is up 12 percent, while cash postings have declined about 1 percent.

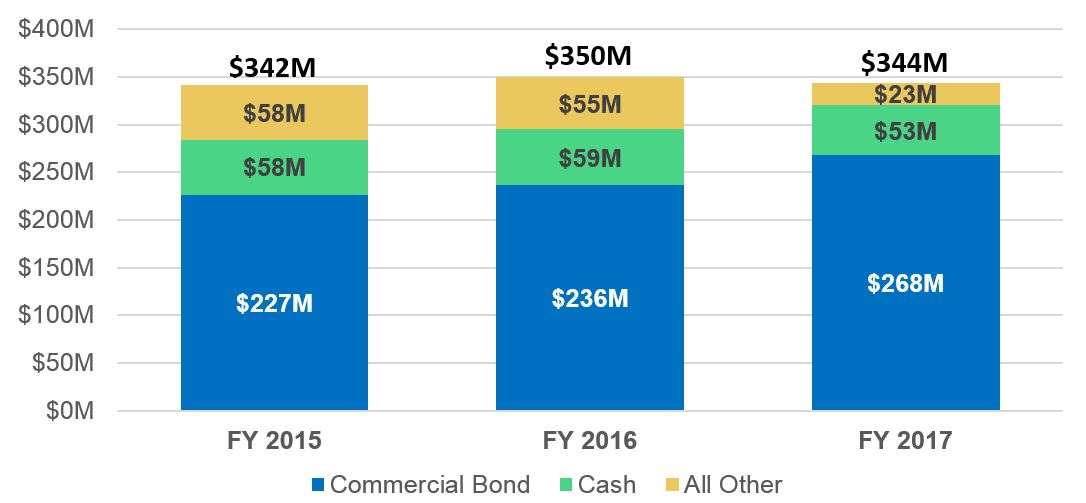

A similar trend can be seen in the dollar amount of bail bonds posted in recent years. As shown in Figure 6, the amount of bail bonds posted has increased 18 percent, from $227 million in FY 2015 to $268 million in FY 2017, while the value of cash posting has fallen 8 percent, from $58 million to $53 million during the same time.

Figure 6: Dollar Amount of Bail Postings by Type

Source: New York City Comptroller’s Office analysis of data provided by the New York State Unified Court System.

One potential explanation for the rising use of bail bonds is that the profile of pretrial detainees has also changed in recent years, with a growing percentage of pretrial detainees being charged with felonies.[60] Bail amounts for felony charges are generally much higher than for misdemeanors.[61]

Bail Bonds Are a Costly Way to Pay Bail

As previously discussed, fees paid to bail bond companies are not refundable, whereas cash bail paid to the court is returned to the defendant if they appear at all court hearings. Consequently, bail bonds are a very costly way for defendants and their families to make a bail payment. Based on the fees bail bond companies are legally allowed to charge under state law, the Office of the Comptroller estimates that people arrested in New York City—almost all of whom are City residents—and their families and friends paid between $16 million and $27 million per year in nonrefundable fees to private bail bond companies. These fees represent a significant transfer of wealth from largely low-income communities to the pockets of bail bondsmen and insurance companies that could potentially be avoided if bail were paid to the court directly in other, existing forms, or if private bail bonds were otherwise prohibited.[62]

That said, the amount of fees New York City residents pay to these bail bond companies is likely higher than the above estimate, based on a review of cases that suggest bail bond companies pocket fees in excess of those legally allowed. According to documents provided to the Office of the Comptroller by the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, bail bond companies may not consistently adhere to these legal limits:

- In a case from September 2015, a person paid $300 to a bail bond company for a $1,000 bond, including a $100 premium and $200 in illegal “courier fees.” The person was initially informed that the money was refundable. The defendant waited for five days in Rikers Island before bail was finally posted by the bond company. At the conclusion of the trial, the company refused to refund the $300. According to a complaint filed with New York State Department of Financial Services (DFS), which regulates bail bond companies, this person was told by the bail agency first that the money would be refunded, then that there was a 90-day waiting period to be refunded, and then finally that the money would not be refunded at all.

- In a 2013 case, a defendant’s family paid $530 to a bail bondsman to secure a $2,500 bail bond, including $200 in fees over the legal limit and $80 in collateral. According to documents, the case had concluded and the defendant had met all bail conditions. However, the family was not able to get the collateral back, or a refund for the $200 fee, since the bondsman’s license had been revoked and another company started operating at his agency’s address. In response to a complaint, DFS said that they no longer held jurisdiction over the issue since the bondsman in question was no longer licensed.

- In February 2016, a person paid a bail agency $4,260 to secure the release of a defendant with a $25,000 bail bond, including a legal premium of $1,760, an illegal fee of $1,000, and $1,500 in collateral. The company did not provide the payee with a signed copy of the contract and took eight days to post bail. According to the payee, following the conclusion of the case, the company refused to return the illegal fee of $1,000.

Evidence also suggests that the industry has been able to exploit gaps and deficiencies in state law governing bail bond practices to the detriment of consumers. For example, a recent court case clarified that one common practice in the industry – retaining bond premiums even if the court denied the bail application and the defendant remained in custody – was in fact illegal, leading DFS to issue guidance to the industry.[63]

Even with this action, however, significant gaps in the law remain, including a lack of explicit limits on the amount of time that can pass before a bail bond agent files a bond in court or returns collateral upon the defendant meeting his or her obligation to appear in court. In fact, as noted above, case documents provided by the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund suggest that at least some bail bond companies are not consistently posting bail in a timely manner. This troubling practice prolongs a person’s time in custody, contributing to the high costs to the City of incarcerating people simply as a result of their inability to make bail. As noted above, more than 12,300 commercial bail bonds were posted in FY 2017.

In addition to exploiting gaps in the law, there is evidence that the commercial bail bond industry in New York City has failed to comply with existing rules and regulations issued by DFS. Specifically, while the State requires that all bail bond companies and agents be licensed by DFS, a report issued by the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund in June 2017 determined that out of 76 distinct bail bond companies “openly operating” in New York City, nine companies were not licensed by the State.[64] Similarly, the report identified six companies that used “fictitious” trade names and another six which were doing business at locations that were not registered with DFS. Finally, the report found numerous examples of obfuscation, including unclear signage, confusing use of pseudonyms, and evasiveness.

Problems with the bail bond industry are not unique to New York; numerous concerns about the industry have been expressed across the U.S.[65] Just across the Hudson River, in 2014, New Jersey’s Commission of Investigation found the bail bond industry to be “highly prone to subversion by unscrupulous and improper practices that make a mockery of the public trust.”[66] As explained by the Justice Policy Institute, “for profit bail bonding is a system that exploits low income communities; is ineffective at safely managing pretrial populations; distorts judicial decision-making; and, gives private insurance agents almost unlimited control over the lives of people they bond out.”[67] Indeed, as a result of these and other concerns, private bail bonds are entirely banned in four U.S. states (Kentucky, Wisconsin, Oregon, and Illinois) and in every other country in the world with the exception of the Philippines.[68]

Consistent with these findings, regulators in other states have taken action against the bail bond industry for violations of local laws.[69] Following a multiyear investigation that raised concerns that included charging fees in excess of state-allowed limits, regulators in Minnesota entered into a consent decree with the industry to improve oversight and promote compliance with the law.[70] And, a probe by the FBI in Louisiana also resulted in the removal of multiple judges from the bench as a result of corruption involving the bail bond industry.[71] For these reasons, the New York City Criminal Justice Agency, the American Bar Association, and the Association of the Bar of the City of New York have all endorsed prohibiting commercial bail bonds.[72]

Commercial Bail Bonds Should be Banned in New York City

While the City has begun to take steps to speed up the process of posting bail, the private bail bond industry remains an impediment to a timely and affordable pretrial release for many defendants. To address the acute problems posed by commercial bail bonds, and build on the reforms that have already been made, commercial bail bond companies should be banned in New York City. Accomplishing this objective could be done without changing state law, as the New York bail law already authorizes bail to be set in forms other than commercial bonds. However, because commercial bail bonds are still widely used, fully realizing this goal would likely require the passage of legislation amending the bail law. Such legislation could be narrowly tailored to prohibit commercial bail bonds only in New York City, or could be included as part of a more comprehensive but longer-term project of ending the use of money bail entirely.

Eliminating private bail bonds could be done without jeopardizing public safety, increasing the number of people who fail to appear in court, or causing more people to be incarcerated. That’s because unlike other parts of the State, New York City already benefits from a relatively robust pretrial services program and other services that can help ensure that the elimination of private bail bonds does not negatively impact public safety or result in more people being incarcerated as a result of an inability to pay bail.[73]

New York City’s pretrial services are provided by the Criminal Justice Agency (CJA), which is funded through City taxpayer dollars with an annual budget of about $18 million that supports about 200 staff.[74] CJA conducts an interview with every defendant and uses a risk assessment tool to provide a release recommendation to the court. In addition, CJA notifies released defendants of their upcoming court dates, and the agency operates a supervised release program in Queens for non-violent felony cases, with the explicit goals of providing an alternative to bail and reducing the pretrial detention population without compromising public safety.

Additionally, research from CJA has shown that cash bail is equally as effective as private bonds in ensuring a defendant’s return to court and that for low-risk defendants, release on recognizance and release on bail produce similar rates of failure-to-appear in court.[75] In addition, according to a 2013 study of defendants in Colorado, unsecured bonds (which only require a defendant to pay money should he or she not appear in court) have the same effectiveness as private bail bonds in securing defendants’ return to court and in protecting public safety.[76] This study also found that pretrial release rates were significantly higher for defendants offered an unsecured bond, thus avoiding the myriad negative impacts of incarceration that include increased rates of re-arrest and higher conviction rates.

Importantly, under state law, readily available alternatives to financially onerous commercial bail bonds already exist—including unsecured bonds, partially secured bonds, and secured bonds. Unsecured bonds require no upfront cash payment by the defendant. To post bail with a partially secured bond, the defendant (or a family member or friend) must deposit up to 10 percent of the bond amount with the court. The responsible party must also document their employment and income and swear under oath that they are liable for the full amount if the defendant does not return to court. To execute a secured bond, the responsible party must deposit personal property valued at least as much as the bond amount or real property having at least twice the bond value. In stark contrast to private bail bonds, in all cases, the deposit or the collateral is returned if the defendant makes all court dates; defendants and their families are not exposed to illegal fees or practices; and the bond is executed as soon as the paperwork is complete.

Despite their existence in state law since 1970, these types of bonds are not commonly used in New York City. Few defense attorneys request alternative forms of bail, and many judges report being unfamiliar with the process and paperwork involved.[77] Even if judges are aware of these alternatives, they may be wary of the time required to complete the process, which requires three separate forms, including information about the responsible party’s employment and income.

Greater use of these types of bonds could help reduce the number of people in jail before trial, particularly for people who have been charged with a misdemeanor. As previously stated, about one-third of all pretrial detainees admitted after being unable to pay bail were charged with a misdemeanor. As misdemeanor charges are among the least severe, people charged with misdemeanors often have bail set at relatively low levels or are released on their own personal recognizance. Therefore, in addition to reducing the financial burden that results from nonrefundable payments associated with bail bonds, the use of less financially onerous bail options that are already authorized under state law has the potential to make it easier for people to make bail, thereby reducing the number of people incarcerated.

A recent study of the use of unsecured and partially secured bonds in New York City found promising outcomes associated with the use of these types of bonds, but also documented the extent to which cash bail and commercial bail bonds dominate the bail system.[78] The Vera Institute of Justice followed the outcomes of 99 cases in which the judge set an unsecured or partially secured bond. While the sample size was small, the study found that 100 percent of cases with unsecured bonds and 33 percent of cases with partially secured bonds set were able to post bail at arraignment. As noted earlier, the City’s overall bail-making rate at arraignment is a far lower 10 percent in felony cases and 13 percent in non-felony cases. Defendants who posted unsecured and partially secured bonds also had similar rates of failure-to-appear in court and rates of re-arrest while awaiting trial as compared to citywide averages. Vera also reported that cases in which judges set alternative forms of bail tended to involve a more lengthy appeal from the defense attorney, including more detailed descriptions of the circumstances of the charge and the defendant’s financial capacity. Overall, Vera found that few city defense attorneys ever request alternative forms of bail.

Following the release of Vera’s report, the Office of Court Administration responded with some positive steps to shorten and simplify the required forms for unsecured, partially secured, and secured bonds.[79] Additionally, the City Council recently provided $150,000 in funding for Vera to study “how to more accurately assess the financial means of a pretrial detainee’s ability to post bail and measure release rates at arraignment.”[80]

Abolishing Commercial Bail in New York City Would Advance Local and National Bail Reform Efforts

While New York City and State policymakers have yet to address problems with the private bail bond industry, a number of reforms have been made recently to the bail system, driven in part by the goal of reducing the number of people in pretrial detention to help facilitate the closure of the jail facilities on Rikers Island. Specifically, in 2016 City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito established an independent commission on New York City criminal justice and incarceration reform, chaired by former Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman. The commission, consisting of leaders in law, academia, business, and the nonprofit sector, published a report in 2017 that, among other things, called on the City to close Rikers Island’s jail facilities. To do so, the report advocated for numerous reforms to the criminal justice system, including expanding pretrial services, making further use of pretrial release and community-based supervision programs, reducing arrests, and moving away from the use of money bail.[81]

In the wake of this effort, the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice published a separate report outlining strategies the City would be pursuing as part of efforts to close the jail facilities on Rikers Island, including a number of changes to existing pretrial policies. Specifically, the report promoted an expansion of supervised release programs as an alternative to incarceration and indicated that the City will pursue the creation of a modern, risk assessment tool to help judges better evaluate the likelihood that a defendant will return for trial.[82] As part of bail reforms in other jurisdictions, including New Jersey, improved risk assessment tools have recently been adopted.[83]

The report also called for additional changes to make it easier for defendants to pay bail, including online payment, placing ATMs in courthouses, and expanded use of “bail facilitators” who serve as contacts and sources of information for relatives of defendants.[84] Many of these reforms were first recommended in 2015 as part of a City-funded study conducted by the Center for Court Innovation that made 17 recommendations for improving the bail system.[85]

A number of policy changes have been announced in recent years as part of these efforts. For instance, in 2015 Mayor de Blasio announced an expansion of “supervised release” programs for misdemeanor and non-violent felony cases, excluding domestic violence.[86] Supervised release provides judges with an alternative to setting bail by facilitating a defendant’s return to their community, subject to certain supervisory conditions. More recently, in June 2017 the City Council passed several measures intended to make it easier for defendants to post bail in a timely manner. One measure requires the Department of Correction to accept bail payments at any time of day and to release defendants for whom bail is posted within five hours.[87] A second new law allows the Department of Correction to delay transfer of detained defendants to Rikers Island to allow more time for bail payment, and a third measure requires the Department to provide incarcerated individuals written information about bail and options for paying bail, and to provide “bail facilitators” who will meet with defendants to assist in posting bail.[88] Finally, at the state level, the New York Charitable Bail Act, adopted in 2012, allows nonprofit organizations, frequently referred to as community bail funds, to pay bail amounts of $2,000 or less for defendants charged with misdemeanors who otherwise could not afford bail.[89]

In making these reforms, New York City and State have joined a growing number of jurisdictions that have implemented or proposed more sweeping changes to bail policies and practices to reduce the role of money in the pretrial justice system.[90] For example, recently enacted reforms in New Jersey (see side box, “Bail Reform in New Jersey”), concerning risk assessment tools as well as other broader reforms, show signs of reducing the number of people detained before trial, and efforts to move away from money bail are also underway in Colorado and New Mexico.[91]

| Bail Reform in New Jersey |

|---|

| In January 2017, New Jersey implemented a sweeping criminal justice reform statute which aimed to minimize the role of cash bail in favor of conditions based on risk and financial ability.[92] While still relatively recent, the new reforms appear to have resulted in fewer people being detained before trial. The New Jersey Judiciary reported that during the first three months under the new reforms, roughly 75 percent of new defendants were released with varying levels of pretrial monitoring, while 12.4 percent were detained, and 10.7 percent were released on recognizance.[93] This stands in contrast to the state of affairs before these reforms were made wherein, according to the Drug Policy Alliance, 73.3 percent of those detained had “pretrial status,” and 38.5 percent remained in holding solely because of inability to pay.[94] From January 1, 2017 to July 31, 2017, New Jersey’s non-sentenced pretrial detention population fell by 16 percent.[95] |

At the same time, courts across the country are also spurring reform, including in Maryland and in Harris County, Texas, where a judge ordered that Harris County cease detaining people charged with low-level crimes who cannot afford bail on grounds of equal protection and due process, citing the practice as “wealth-based discrimination.”[96] In addition, a report issued in October 2017 by the Pretrial Detention Reform Workgroup established by the Chief Justice of California called for reforms in California to move away from money bail so as to cease incarcerating people solely due to their inability to afford bail.[97] These efforts have not been lost on federal policymakers either, with Senators Rand Paul and Kamala Harris recently introducing the “Pretrial Integrity and Safety Act,” which among other things, encourages states to replace money bail with pretrial services and risk assessments to reduce the number of people incarcerated simply because they are unable to afford bail.[98]

Abolishing commercial bail bonds in New York City would further advance these goals and help New York City and State remain national leaders in the efforts to build a fairer and stronger justice system.

Conclusion

This report has documented the negative financial and personal costs associated with New York City’s pretrial justice system, particularly around the use of private bail bonds. Too often, people arrested in New York City find themselves subject to the inhumane conditions of Rikers Island jails for a matter of days while their family or friends try to gather enough resources to make an expensive payment to a bail bondsman in order to get their loved one back to their families and communities. As described previously, for many reasons, neither the City nor its residents benefit from this reality.

Therefore, reforms that will reduce those costs, and end the unjust practice of detaining people before they have been found guilty of a crime simply because they do not have adequate financial resources to make bail, are urgently needed. A critical first step in this process should be the elimination of private bail bonds from New York City’s court system.

Abolishing commercial bail bonds would further existing City efforts to reduce the jail population and close the jail facilities on Rikers Island in two ways. First, without the opportunity to select private bail bonds, judges would be encouraged to set bail in more affordable forms, reducing the number of people who enter jail because their bail is set at an unaffordable level. Second, given that private bail bond providers have been found to delay bail posting, ending this practice would help to reduce the length of jail stays resulting in fewer people incarcerated at any given time.

At the same time, over the long term, New York’s justice system should be one in which money is not a factor in whether or not someone is detained in jail or retains their personal liberties while awaiting trial. Accomplishing this objective will take time but is critical to building a fairer and more just society and to reducing the jail population to a level that would enable the closure of the Rikers Island jail complex.

Acknowledgments

Comptroller Scott M. Stringer thanks Tammy Gamerman, Director of Budget Research, and Zachary Schechter-Steinberg, Deputy Policy Director, the lead authors of this report. He also acknowledges the contributions of David Saltonstall, Assistant Comptroller for Policy; Eng Kai Tan, Budget Bureau Chief; Rosa Charles, Senior Budget Analyst; Lawrence Mielnicki, Chief Economist; Preston Niblack, Deputy Comptroller for Budget; Jennifer Conovitz, Special Counsel to the First Deputy Comptroller; Marvin Peguese, Deputy General Counsel; Nicole Jacoby, First Deputy General Counsel; Katherine Diaz, General Counsel; Joseph Asprea, Policy Intern; Angela Chen, Senior Web Developer and Graphic Designer; and Archer Hutchinson, Web Developer and Graphic Designer.

Endnotes

[1] Harvard Law School Criminal Justice Policy Program, Moving Beyond Money: A Primer on Bail Reform (October 2016), http://cjpp.law.harvard.edu/assets/FINAL-Primer-on-Bail-Reform.pdf.

[2] Harvard Law School Criminal Justice Policy Program, Moving Beyond Money: A Primer on Bail Reform (October 2016), http://cjpp.law.harvard.edu/assets/FINAL-Primer-on-Bail-Reform.pdf.

[3] Stevenson, M. and Mayson, S., Bail Reform: New Directions for Pretrial Detention and Release (March 13, 2017), http://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2747&context=faculty_scholarship.

[4] Bureau of Justice Statistics, Jail Inmates at Midyear 2014 (June 2015), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/jim14.pdf. Stevenson, M. and Mayson, S., Bail Reform: New Directions for Pretrial Detention and Release (March 13, 2017), http://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2747&context=faculty_scholarship.

[5] Stevenson, M. and Mayson, S., Bail Reform: New Directions for Pretrial Detention and Release (March 13, 2017), http://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2747&context=faculty_scholarship.

[6] Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, A More Just New York City (April 2017), p. 51, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/577d72ee2e69cfa9dd2b7a5e/t/58f67e6846c3c424ad706463/1492549229112/Lippman+Commission+FINAL+4.18.17+Singles.pdf.

[7] New York State Criminal Procedure Law, §510.30, http://codes.findlaw.com/ny/criminal-procedure-law/cpl-sect-510-30.html.

[8] Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, A More Just New York City (April 2017), p. 43, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/577d72ee2e69cfa9dd2b7a5e/t/58f67e6846c3c424ad706463/1492549229112/Lippman+Commission+FINAL+4.18.17+Singles.pdf.

[9] New York City Criminal Justice Agency, 2015 Annual Report, p. 35, http://www.nycja.org/lwdcms/doc-view.php?module=reports&module_id=1577&doc_name=doc.

[10] New York City Center for Court Innovation, Navigating the Bail Payment System in New York City (December 2015), pp. 7-9, https://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/documents/Bail%20Payment%20in%20NYC.pdf.

[11] New York City Criminal Justice Agency, 2015 Annual Report, p. 17, http://www.nycja.org/lwdcms/doc-view.php?module=reports&module_id=1577&doc_name=doc.

[12] Vera Institute, “Incarceration Trends,” http://trends.vera.org/incarceration-rates?data=pretrial.

[13] U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties, 2009 – Statistical Tables (December 2013), p. 19, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/fdluc09.pdf. New York City Criminal Justice Agency, 2015 Annual Report, p. 22, http://www.nycja.org/lwdcms/doc-view.php?module=reports&module_id=1577&doc_name=doc.

[14] Sheriff’s Justice Institute, Central Bond Court Report (April 2016), p. 2, https://www.chicagoreader.com/pdf/20161026/Sheriff_s-Justice-Institute-Central-Bond-Court-Study-070616.pdf. Public Policy Institute of California, Pretrial Detention and Jail Capacity in California (July 2015), p. 4, http://www.ppic.org/content/pubs/report/R_715STR.pdf.

[15] Chauhan, P., Hood, Q.O., Balazon, E.M., Cuevas, C., Lu, O., Tomascak, S., & Fera, A.G. with an Introduction by Jeremy Travis, Trends in Custody: New York City Department of Correction, 2000-2015 (April 2017), p. 19, http://misdemeanorjustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/DOC_Custody_Trends.pdf.

[16] Chauhan, P., Hood, Q.O., Balazon, E.M., Cuevas, C., Lu, O., Tomascak, S., & Fera, A.G. with an Introduction by Jeremy Travis, Trends in Custody: New York City Department of Correction, 2000-2015 (April 2017), p. 20, http://misdemeanorjustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/DOC_Custody_Trends.pdf.

[17] Excludes jail admissions resulting from a criminal conviction or a parole violation.

[18] Estimate includes only detainees with bail set at the time of jail admission. Additional detainees may have had bail conditions set at subsequent court hearings. To isolate the population who could be released from jail upon posting bail, the following groups are excluded: detainees with a warrant or other hold, including arrests due to a warrant and bail amounts equal to $25 or less, which indicate an administrative hold; detainees discharged within two hours; and detainees remanded to jail.

[19] In many cases, pretrial detainees had two different bail amounts set – one for cash bail and one for commercial bail bonds. This report uses the higher bail amount set for commercial bail bonds.

[20] Based on data provided by the New York City Criminal Courts, bail was posted 24,229 times in FY 2017. Including all people who had bail set at arraignment or at later court hearings, New York City jails released people 17,276 times in the last fiscal year following payment of bail.

[21] New York City Criminal Justice Agency, 2015 Annual Report, p. 23, http://www.nycja.org/lwdcms/doc-view.php?module=reports&module_id=1577&doc_name=doc.

[22] Based on an average daily population of 9,500 in FY 2017, as reported in the FY 2017 Mayor’s Management Report. Cost estimate includes centrally funded fringe benefits and pension costs, as well as medical services provided by the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and New York City Health+Hospitals. The figures for fringe benefits and pension costs are estimated as of April 2017, as presented in the FY 2018 Executive Budget Message of the Mayor. The estimated cost excludes debt service, judgments and claims, and legal services. In FY 2017, debt service added daily costs of $56 per inmate, and tort claim settlements and judgments added $9 per inmate per day in FY 2016. Fringe benefits include the cost of retiree health insurance.

[23] Includes expenditures of $238 million at Health+Hospitals and $36 million at the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene in FY 2017. In FY 2016, there were 3,658 tort claims filed against the City for personal injury at a correction facility and $14 million paid in total judgments and settlements related to correction facilities. Given that these judgements are frequently the result of incidents that occurred in previous years, the persistently high levels of violence in jails suggests that claims against the City and judgements and settlements are likely to rise in future years. New York City Office of the Comptroller, Claims Report: Fiscal Year 2016 (February 2017), p. 35 and p. 37, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/Claims-Report-FY2016.pdf. New York City Mayor’s Office of Operations, Mayor’s Management Report for Fiscal Year 2017: Department of Correction (September 2017), http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/operations/downloads/pdf/mmr2017/doc.pdf.

[24] New York City Office of the Comptroller, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2017 (October 2017), p. 350 and p. 393, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/wp-content/uploads/documents/CAFR2017.pdf.

[25] New York City Independent Budget Office, Letter to Council Member Rory Lancman (May 16, 2017), http://www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/pretrial-detention-rates-may-2017.pdf.

[26] New York City Independent Budget Office, Letter to Council Member Rory Lancman (May 16, 2017), http://www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/iboreports/pretrial-detention-rates-may-2017.pdf. In 2009, DOC reported potential marginal savings of $74 per day. Parsons, J., Wei, Q., Rinaldi, J., Henrichson, C., Sandwick, T., Wendel, T., Drucker, E., Ostermann, M., DeWitt, S., and Clear, T., A Natural Experiment in Reform: Analyzing Drug Policy Change in New York City, Final Report to the National Institute of Justice (January 2015), p. 164, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/248524.pdf.

[27] New York City Center for Court Innovation, Navigating the Bail Payment System in New York City (December 2015), p. 17, https://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/documents/Bail%20Payment%20in%20NYC.pdf.

[28] Correctional Health Services, CHS Access Report: August 2017, p. 3, http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/boc/downloads/pdf/access-reports/august-access-report.pdf.

[29] Estimate assumes one health worker performs a four-hour medical screening, and staff work 35 hours per week and 48 weeks per year.

[30] In FY 2017, DOC employed 10,862 uniformed officers as of the end of the year.

[31] Pew Charitable Trusts, Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility (2010), http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2010/collateralcosts1pdf. Baradaran Baughman, S., Costs of Pretrial Detention, Boston University Law Review (Vol. 97:1, 2017), https://www.bu.edu/bulawreview/files/2017/03/BAUGHMAN.pdf. McLaughlin, M., Pettus-Davis, C., Brown, D., Veeh, C., and Renn, T., The Economic Burden of Incarceration, Concordance Institute for Advancing Social Justice Washington University in St. Louis, (July 2016), https://joinnia.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/The-Economic-Burden-of-Incarceration-in-the-US-2016.pdf. National Health marriage Resource Center, Incarceration and Family Relationships: A Fact Sheet, http://www.mfldiobr.org/uploads/1/1/6/4/11641397/incarceration-and-family-relationships.pdf.

[32] New York City Criminal Justice Agency, Testimony to the New York City Council (January 18, 2017), http://www.nycja.org/resources/details.php?id=1343.

[33] Based on an average daily population of 3,340 detainees who have bail set at the time of admission. Estimate assumes 71 percent of incarceration days (or five of seven days per week) lead to lost wages.

[34] Pew Charitable Trusts, Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility (2010), p. 11, http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2010/collateralcosts1pdf.

[35] Baradaran Baughman, S., Costs of Pretrial Detention, Boston University Law Review (Vol. 97:1, 2017), p. 5, https://www.bu.edu/bulawreview/files/2017/03/BAUGHMAN.pdf.

[36] Baradaran Baughman, S., Costs of Pretrial Detention, Boston University Law Review (Vol. 97:1, 2017), p. 7, https://www.bu.edu/bulawreview/files/2017/03/BAUGHMAN.pdf. National Health Marriage Resource Center, Incarceration and Family Relationships: A Fact Sheet, http://www.mfldiobr.org/uploads/1/1/6/4/11641397/incarceration-and-family-relationships.pdf.

[37] Pew Charitable Trusts, Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility (2010), p. 18, http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2010/collateralcosts1pdf.

[38] Estimate based on 360,000 deposits and an average deposit of $48. Frank Doka, Deputy Commissioner of the New York City Department of Correction, Testimony to the New York City Council (September 26, 2016), p.2, http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=2683889&GUID=6C31F208-4D65-4D87-818A-EA334710FD4A&Options=&Search=.

[39] Based on a local call to a DOC facility. Securus Technologies, “Rate Quote” (accessed September 29, 2017), https://securustech.net/call-rate-calculator.

[40] Intro 1152-2016, http://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=2683889&GUID=6C31F208-4D65-4D87-818A-EA334710FD4A&Options=&Search=. J Pay, Inc., Testimony to the New York City Council (September 26, 2016).

[41] Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, A More Just New York City (April 2017), p. 27, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/577d72ee2e69cfa9dd2b7a5e /t/58f67e6846c3c424ad706463/1492549229112/Lippman+Commission+FINAL+4.18.17+Singles.pdf.

[42] New York City Department of Correction, Visitation Quarterly Report for the 4th Quarter of FY 2017, http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doc/downloads/pdf/INTRO_706_REPORTING_4th_QUARTER_FY17_7-26-17.pdf.