Executive Summary

The January 9, 2022, fire at the Twin Parks development in the Bronx tragically took the lives of 17 New Yorkers, injured dozens, and shocked and horrified people across the five boroughs and beyond. Unfortunately, the underlying factors that led to the fire are all too commonplace. Though attention focused on the lack of self-closing doors, which allowed the fire to spread rapidly and become so deadly, a lack of adequate heat is an underlying condition which continues to plague New York City.

Between 2017 and 2021, there were over 100 fires in New York City residential buildings caused by portable heaters like the one that caused the Twin Parks fire. Over that same period, New Yorkers called 311 nearly one million times to report a lack of heat in their homes. Yet the City of New York’s Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) issued just 21,610 violations to landlords for failure to maintain the minimum required temperature. Such a low conversion rate of complaints to violations suggest that the enforcement regime is not working effectively.

Persistent heat issues – or the chronic lack of heat, year-over-year – are concentrated in a relatively small percentage of buildings: there are 1,077 buildings in New York City in which tenants complained about a lack of heat more than five times each heat season between 2017 and 2021. Those 1,077 buildings account for just 1.5% of buildings in which tenants reported heat issues but represent a disproportionate share (30%) of 311 heat complaints.

Heat complaints and violations are not equally distributed across the city but concentrated in the Northwest and South Bronx, Central Brooklyn and, Northern Manhattan – all neighborhoods in which most residents are people of color. In a cruel irony, this lack of basic building maintenance is occurring as buildings in these communities are sold for increasingly high prices. Instead of improved living conditions under new ownership, existing tenants often simultaneously face decreased services and the threat of rising rents or eviction. Stronger code enforcement, in addition to tenant protections, is necessary to compel landlords, especially those with low-income, immigrant, and tenants of color, to treat the properties they own not just as an investment vehicle, but as people’s homes.

Though less immediately catastrophic than a fire, living without heat for an extended period can cause a serious decline in tenants’ mental and physical health. Residents often turn to unsafe methods, such as the portable heaters, to keep themselves and their families warm. Data-informed inspections, proactive code-enforcement, and escalating penalties, particularly against the worst actors who repeatedly fail to respond to interventions, are essential components of a successful code enforcement regime. While New York City has a strong basis from which to start, we must do more to protect and empower tenants to prevent future tragedies like Twin Parks, and to ensure that everyone across New York City can live in safety and with dignity.

Key Findings

- During the 2017 – 2021 heat seasons, a total of 814,542 heat complaints were made by tenants living in 70,766 unique privately owned buildings.

- Heat complaints and violations are not distributed equally across the city. The top five neighborhoods from which heat complaints are made and in which the City issues violations are majority people of color communities. The population of the five community districts with the highest volume of 311 complaints related to a lack of heat are 93% people of color and the five community districts with the most heat related violations are 89% people of color.

- Almost 80% of heat complaints come from buildings with 5 or fewer complaints made within the same heat season and nearly 90% come from buildings in which there were 10 or fewer heat complaints made in the same heat season, indicating that persistent heat issues are concentrated in around 10% of buildings experiencing heat issues, overall.

- In a small percentage of buildings, lack of heat is persistent and severe. On average, there are over 6,000 unique buildings each year in the five years observed in which tenants complain about a lack of heat more than 5 times and over 1,350 buildings in which tenants complain about a lack of heat more than 20 times.

- There are 1,077 buildings in New York City in which tenants complained more than 5 times each heat season from 2017 to 2021, about 1.5% of all buildings with heat complaints. Just about 30%, or 244,176, of all complaints made city-wide during the 2017 – 2021 heat seasons were made by tenants living in these 1,077 buildings.

- Of those 1,077 buildings in which tenants complained more than 5 times each heat season from 2017 to 2021, over 25% of the buildings (274 buildings), did not have any violations recorded against them, indicating the City did not take any enforcement action related to a lack of heat.

- The City’s active strategies for addressing heat complaints are generally effective when they are deployed. However, they are not deployed in many eligible cases, and the strategic rationale for their deployment is unclear.

- Issuance of violations to a building correlated to a 47% average drop in the number of heat complaints in the following heat season. However, during this five-year period, violations for failure to provide an adequate supply of heat were issued for just 3% of heat complaints.

- Litigation correlated to a 45% average drop in the number of heat complaints in the following year. However, HPD-initiated litigation for heat complaints has dropped significantly in recent years, to a level less than one-third of what it was five years ago.

- The Emergency Repair Program (ERP) correlated with a 38% average drop in the number of heat complaints in the following year.

- HPD’s new Heat Sensor Program, established by City Council legislation in 2020 correlated with a 54% average drop (62% median) in the number of heat complaints in the years after heat sensors were installed, compared to the three prior years. However, the program only currently covers 50 buildings, and enforcement of compliance with the program has been limited.

Recommendations

Use data & technology to inform and prioritize inspections with a focus on buildings with persistent heat complaints.

- Provide code inspectors with comprehensive information about the history of heat complaints of each building they inspect. This should include the number of complaints made in the current and previous heat seasons and from which apartments and during which time of day. This information should inform their inspections and time should be allocated appropriately depending on the severity of the history of complaints.

- Build on this report’s analysis to create and further refine a database of “buildings with persistent heat complaints” to prioritize inspections and proactive code enforcement strategies. While the analysis in this report has defined persistent heat complaints to include the buildings in which tenants complained more than 5 times each heat season between 2017 and 2021, there are countless ways to create a similar dataset aimed at locating the buildings in which tenants are consistently complaining about a lack of heat. The City should conduct additional and variable data analysis to further refine this definition. That universe of buildings should then be used to inform the City’s design of programs and interventions to alleviate lack of heat and better hold landlords accountable.

- For buildings with persistent heat complaints, defined in this report as the 1,077 buildings in which tenants complained more than 5 times each heat season between 2017 and 2021, which are responsible for 30% of all heat complaints over that same period:

- Pass Int. 434 of 2022 (sponsored by Council Member Sanchez), which expands the Heat Sensor Program and enforces landlord compliance. Consider covering all buildings with persistent heat complaints by the Heat Sensor Program.

- Require the City to proactively inspect buildings with persistent heat complaints. The new Real Time Field Force (RTFF) technology should also be used to quickly route inspectors to these buildings and reduce the time it takes to conduct a physical inspection.

- Allow tenants living in buildings with a history of persistent heat complaints to schedule inspections within a window of time in which it is typically most cold in their apartments. These inspections should not trigger landlord notification and tenants should be allowed to schedule them overnight.

Conduct comprehensive site inspections and identify landlords’ willingness to comply

- Conduct joint HPD and DOB inspections of central heating and distributions systems in buildings with persistent heat complaints. This inspection should seek to determine the causes of the outage and be a guiding document for HPD’s enforcement approach.

- Contact the owner of the property to determine the barriers impeding their ability to consistently provide an adequate supply of heat. Where owners are willing to cooperate, make referrals to City and State programs that provide resources and oversight to achieve repairs. Consider requiring that owners of property submit a description of the conditions causing the violation when filing a certification of correction for heat code violations.

Expand Proactive Code Enforcement and Targeted Escalation

- Use the Emergency Repair Program (ERP) or the 7A Program, in appropriate instances, to make comprehensive repairs needed to ensure the adequate supply of heat to tenants if landlords do not meet milestones that demonstrate progress.

- Amend the rules enacting Local Law 6 of 2013 (whose lead sponsor was Council Member Gale Brewer), either through HPD-initiated rule amendment, or City Council legislation, to give HPD the power and responsibility to issue an administrative order to landlords to correct underlying conditions that are causing heat violations.

- Pass Int. 583 of 2022 (sponsored by Public Advocate Jumaane Williams), which would increase the penalties for many Housing and Maintenance Code violations and would require HPD to create an annual certification of correction watchlist. HPD would be required to re-inspect any violation to ensure that it was properly addressed by the owner prior to resolution (currently, owner self-certification is allowed).

- Where owners continually fail to address hazardous living conditions and are non-responsive to escalated enforcement strategies, offer preservation purchases (e.g. through HPD’s Neighborhood Pillars program), where buildings are acquired by not-for-profit developers as affordable housing and renovated as necessary.

Expand tenants’ rights and education

- Expand direct multilingual outreach to tenants, particularly in neighborhoods with large numbers of residents who are foreign-born.

- Fund community organizations that educate and assist tenants.

- Pass S3082/A5573, or Good Cause evictions protections.

Introduction

Given the significant impacts of residential fires, New York City has a long history of regulating the built environment for fire safety. Throughout the 19th century, living conditions were terrible for low-income New Yorkers – most working people lived in apartments with limited sunlight and no hot running water in extremely dense neighborhoods with little to no open space. When fires broke out, they spread far and quickly.

Tenement reforms were passed in 1867, 1879, and 1901 and were increasingly effective at ensuring that new buildings were safely constructed. The New York City Housing and Maintenance Code and the New York State Multiple Dwelling Law are the primary laws that currently regulate the standards for existing multi-family dwellings. Legislators regularly update these statutes based on evolving health and safety standards, but a persistent lack of heat, and in some cases devastating fires, such as the one at Twin Parks on January 9, 2022, still occur.

The fire at Twin Parks broke out after a malfunctioning electric heater caught fire. Between 2017 and 2021, there were over 100 fires in New York City residential buildings caused by portable heaters.[i] While a loss of life or serious injury is uncommon, nearly everyone who survives a fire in their home loses personal belongings and many are forced to relocate temporarily or permanently. The trauma, loss of security, and dislocation can cause long-term negative health impacts, including post-traumatic stress disorders.[1] Moreover, living in a home with a persistent lack of heat can lead to a decline in both mental and physical health.

In the immediate wake of the January 9th blaze, New York City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams appointed the Twin Parks Citywide Taskforce on Fire Prevention, which was chaired by Council Member Oswald Feliz, who represents Twin Parks. In May and June 2022, the Council passed laws that reduce the amount of time that a landlord has to respond to, and increase the penalties for, a violation related to self-closing doors, create a self-closing door inspection program, ban the sale of certain types of electric heaters, and expand fire education and language accessibility (sponsored by Council Members Feliz and Nantasha Williams, Immigration Committee Chair Shahana Hanif, and Housing & Buildings Committee Chair Pierina Sanchez).[2]

In addition to these essential pieces of legislation, the City must do more to address the underlying problem of tenants living in chronically cold apartments. Though attention after Twin Parks focused on the lack of self-closing doors, which allowed the fire to spread rapidly and become so deadly, the lack of adequate heat is an underlying condition which continues to plague New York City.

When landlords consistently fail to provide adequate heat, and the City fails to properly intervene, tenants frequently resort to unsafe solutions to keep themselves and their families warm. This includes using affordable, but often unsafe electric heaters and running electric or natural gas stoves for extended periods of time. In the wake of the devastating fire, there is an urgent need to investigate the specific processes by which tenant heat complaints are addressed, identify areas where there is room for improvement, and implement those changes. We must act now to avoid future tragedies like Twin Parks and ensure that all New Yorkers have a safe and warm home.

Overview of the Heat Code Enforcement Process

When a New York City tenant who lives in a privately owned building is not receiving adequate heat and has been unsuccessful in getting their landlord or building manager to address the issue, they typically call 311.[ii] Once a complaint for a lack of heat is received, it is automatically routed to HPD’s Integrated Information System (HPDInfo), and the owner of the building receives an automated call that instructs them to restore the service.[iii]

When multiple tenants in the same building call 311 to complain about a lack of adequate heat, their complaints are linked, and the issue is treated as a building-wide heat outage. Complaints from numerous residents are treated as single complaint and are not investigated separately; all duplicate complaints are closed when the “initial” complaint is closed.

Following landlord notification, HPD reaches out to the resident of the initial complaint to determine if the complaint has been resolved. If the tenant contacted states that heat has been restored, the complaint is closed. If the tenant is unable to be reached or states that the condition has not been corrected, the complaint is routed to the borough office and an inspector is sent to the property to investigate.

Once an inspector arrives at the building and records their inspection in HPD’s internal database, the initial complaint and all associated duplicate complaints are automatically closed. If an inspector cannot gain access to the apartment of the initial complainant, they are instructed to attempt to access other units in the building. If they are unable to gain access to any apartment in the building, the inspector leaves a no access card, which notes the time of their attempted inspection. The complaint is closed, no violation is issued, and no follow up takes place.

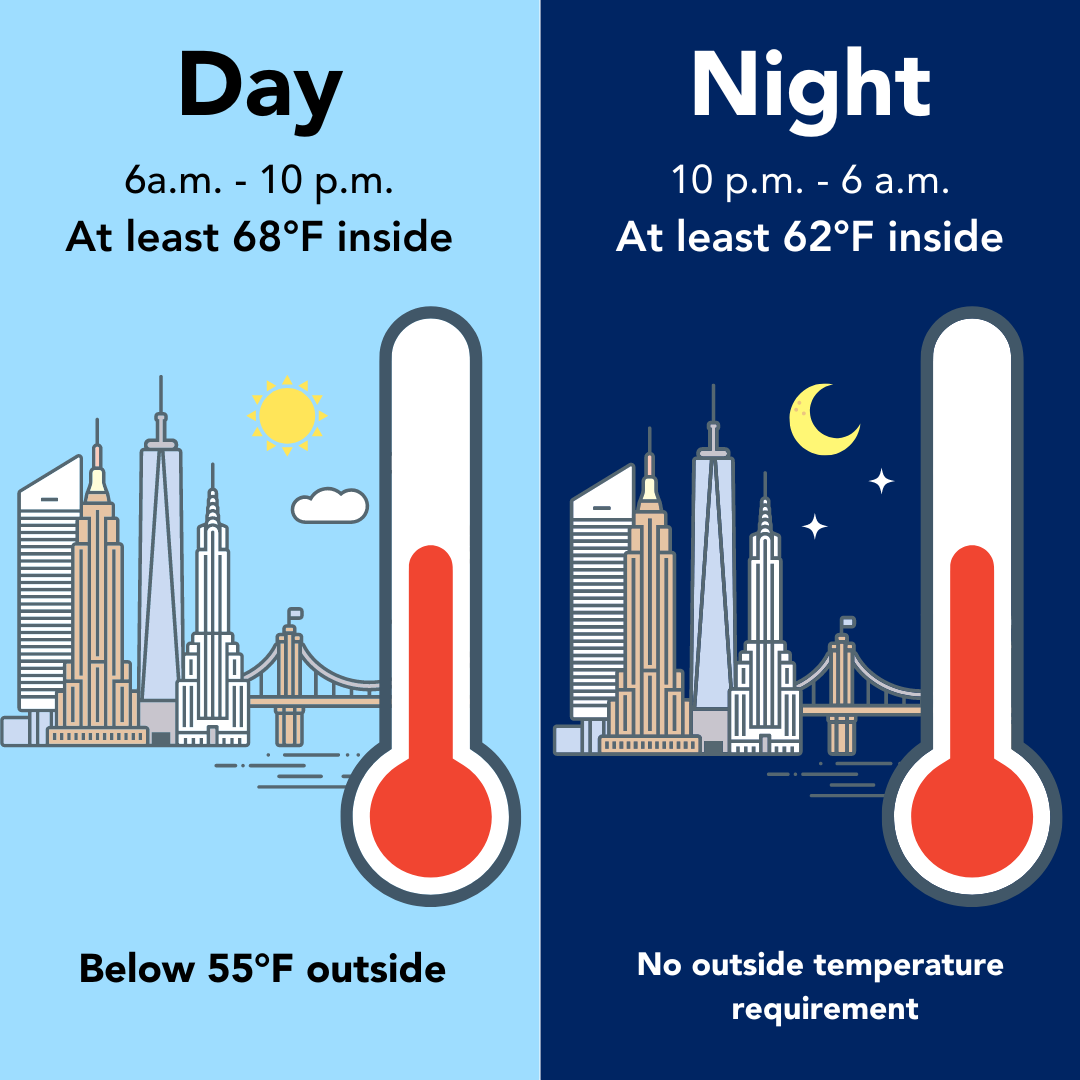

If an inspector gains access and determines that the temperature is below the legally required level, the owner of the building will be issued a Notice of Violation (NOV).[iv] Heat violations are Class C violations, meaning they are considered immediately hazardous and must be addressed by the owner within 24 hours.

Once a violation has been issued, an owner can certify online or through a paper process that they have corrected the violation. HPD reviews the certification for validity and timeliness and, unless there are discrepancies discovered, closes the violation without further inspection. Owners are subject to criminal and financial penalties for false certification and HPD states that it re-inspects a certain percentage of Class B&C violations to ensure that the conditions were corrected as certified.[3]

HPD may initiate legal action in Housing Court to pursue additional enforcement or to collect unpaid civil penalties. A $200 inspection fee may be imposed if a third or subsequent inspection within one heat season results in a violation issued for a lack of heat or hot water. HPD maintenance staff may also correct the conditions, or the City may contract with pre-qualified professionals to make the repairs through the Emergency Repair Program (ERP). After 60 days of lack of payment by the owner the cost of those repairs can be placed as a lien against the property.[4]

| Violation Type | Penalty | Additional Penalty |

| Class C Violation, Heat or Hot Water | $250-$500 per violation per day | $500-$1,000 per day for each subsequent violation at the same building that during two consecutive periods of October 1st through May 31st |

A Brief History of Heat Code Enforcement in New York City

Given the longstanding prevalence and devastating effects of residential fires, there is a long history of organizing for fire prevention and tenant protections in New York City. The Tenement House Act of 1867, the nation’s first comprehensive housing reform law, required that landlords install fire escapes in newly constructed buildings, among several other measures largely aimed at fire safety. In response to ongoing health and safety issues, New Yorkers organized to win additional rights and protections. Increasingly effective tenement reforms were passed in 1879 and 1901. Due to the ongoing persistence of tenants and advocates over the past 150 years, New York City currently has one of the most robust housing code enforcement frameworks in the United States.

New York City’s Housing and Maintenance Code (HMC), first passed in 1967, enshrines tenants’ right to heat and hot water, pest management, and protection from environmental hazards such as lead and mold, among other things. It has been regularly updated since its original passage to include additional landlord requirements and tenant protections. Many tenants have additional rights and avenues for enforcement through other regulatory structures, such as rent stabilization and through agreements with the city, state, or federal government, such as Housing Assistance Payment contracts or regulatory agreements. The Department of Buildings (DOB) and the Fire Department also play a crucial role in enforcing additional standards, such as construction codes, zoning codes, New York State’s multiple dwelling law, and fire safety regulations.

HPD currently employs 200 people with the title of “inspector.” HPD’s inspectors are employed within the Office of Housing Preservation, which had an overall vacancy rate of 18.9% in October 2022.[5] These civil servants respond to approximately 500,000 complaints every year, about 20% of which relate to a lack of heat or hot water. Although there are a few relatively new and small-scale proactive code enforcement programs discussed below, HPD generally only has the capacity to enforce the HMC if tenants in a building complain to 311 about the conditions, and then allow inspectors to enter their apartments. HPD allows tenants to make complaints anonymously, but many tenants still fear landlord retaliation. Many residents may be scared to complain because of their immigration status, have language barriers, or be unaware of the rights.

Drastically under-resourced code enforcement has hamstrung the effectiveness of housing and buildings standards since the original tenement laws were passed in the mid-19th century. It is not enough to simply have rules on the books – the City must make sure that tenants are aware of their rights, fund technology and appropriate levels of staff, and commit to escalatory actions against owners who fail to correct illegal conditions.

Heat Code Enforcement

Analysis of Heat Complaints

Complaints to 311 from tenants in privately-owned buildings related to a lack of heat have declined slightly over the past five years, with an average of 162,908 complaints per year over the 2017 to 2021 heat seasons.[v]

Heat Complaints and Violations, 2017-2022

Just over 51% of all heat complaints made to 311 between 2017 and 2021 were resolved when HPD staff made telephone contact with a tenant in the building from which the complaint was made and confirmed that the condition had been corrected. The initial complaint – and all duplicate complaints – are closed at this point without an HPD staff person conducting a physical inspection.

An additional 24% of all heat complaints over the past 5 years were closed when an inspector was “advised by a tenant in the building” that the heat had been restored. The data published by HPD does not make clear whether the tenant that provided the information that the heat had been restored was the initial complainant or whether HPD gained the information over the phone or in person during a physical inspection.

Just over 13% of complaints were closed because the code inspector was unable to gain access to the apartment of the initial complainant or any other resident in the building whom they attempted to contact. No further action is taken without an additional complaint. Approximately 8% of all complaints are closed after an inspector gains access to the apartment of the complainant or any other tenant in the building and determines that the temperature is above the legally required levels.

Over this five-year period, just 3% of complaints resulted in a violation being written, resulting in just 21,610 violations to landlords for failure to provide an adequate supply of heat, with an average of 4,322 issued annually.[vi] This does not mean, however, that heat is successfully restored the other 97% of the time, since lack of access or failure to reach the initial complainant result in a “resolution” of the complaint, frequently with no evidence the heat has been restored.

Recorded Result of 311 Complaints, 5 Year Average

Results of a Site Inspection, 5 Year Total

Effectiveness of Interventions

During the 2017 – 2021 heat seasons, a total of 814,542 heat complaints were made by tenants living in 70,766 unique buildings, and 21,610 violations for failure to provide heat were issued to the owners of 11,932 unique buildings. In addition to inspecting complaints and issuing violations, HPD has a number of interventions in its arsenal to hold landlords accountable and keep tenants safe.

We analyzed the effectiveness of four interventions: issuance of a code violation, HPD-initiated litigation, the Emergency Repair Program, and the Heat Sensor Program. We compared the number of heat complaints in the heat season in which the intervention occurred to the number of heat complaints in the following heat season as a measure of increased tenant satisfaction.[vii] Because a relatively small number of buildings generate a significantly higher number of complaints each year, it is instructive to examine the median as well as the average to measure the results for a typical building with heat issues. Both datapoints are included in the analysis.

Violations

A failure to provide an adequate supply of heat is a Class C violation, which means that they are considered immediately hazardous. All other Class C violations must be corrected within 21 days, but heat and hot water violations must be corrected by the owner within 24 hours.[6]

After an owner addresses the conditions, they can self-certify that they have corrected the violation through a paper process or through the City’s eCertification system.[viii] Both systems require the owner to provide contact information for the employee or vendor who corrected the condition and to certify that the information provided is true and correct. If an owner has certified correction of the heat violation within the 24-hour time period, they can submit a payment of $250 plus a minimal processing fee to satisfy the civil penalties owed and close the violation.

The system provides a warning that HPD may conduct a reinspection in order to determine that the violation has been corrected as certified and notifies owners that false certification may result in criminal penalties or fines up to $1,000 per violation. HPD indicates that they reinspect a certain number of B and C violations as a check on false certification, but specific data on reinspection rates are not publicly available.[7]

Our analysis indicates that when a landlord is issued a violation for a failure to provide an adequate supply of heat, there are significantly fewer heat related tenant complaints to 311 in the following heat season. The average number of complaints at buildings in which a heat violation was written during the 2017 – 2020 heat seasons was 13.5. In the heat season following the year in which the violation was written that average dropped to 7.3 complaints, or a 46% drop. Within the same sample, the median number of complaints made in the same heat season in which the landlord received a violation was 5.3 and, in the year following, that number dropped to 1 – an 81% drop.

This indicates that, while violations can often be difficult to get recorded, they are typically an effective method of code enforcement.

Reduction in 311 Complaints One Year After a Violation Issued

Of the 21,610 heat violations that were issued to landlords during the 2017 – 2021 heat seasons, 16,288 have been either closed or dismissed. Of the 5,109 violations that remain open, HPD data indicate that 3,656 have no further action beyond HPD transmitting a Notice of Violation to the landlord. The remaining 1,453 –about 7 percent of all heat violations – have some other adverse status, such as a violation being certified late/invalid or an inspector being unable to enter the building to re-inspect.

Litigation

HPD indicates that they typically initiate a court proceeding for all heat violations.[8] During the 2017 – 2021 heat seasons, HPD initiated 10,486 cases against owners for failure to provide adequate heat in 8,126 unique buildings. During the same period, violations were issued to 11,932 unique buildings, indicating that HPD pursued litigation against 68% of the owners of buildings in which heat violations were issued.

While data limitations make it impossible to directly match violations to cases, an analysis of how many buildings are subject to both the issuance of a heat violation and HPD-initiated litigation within the same heat season is a helpful measure to determine if there have been any shifts. We found that there was a significant decline in HPD-initiated cases related to heat violations from 2017 through 2020; while there was a slightly increase from 2020-21 to 2021-22, the number of HPD-initiated cases is less than one-third of what it was five years ago.

Total Violations & Litigation, 2017 – 2022

We analyzed the data further by creating three categories within each heat season, buildings subject to litigation that did not receive a heat violation within the same heat season, buildings subject to both a violation and litigation within the same heat season, and buildings that received violations but against which HPD did not initiate litigation in the same heat season.

Buildings with Either a Violation or Litigation

| Number of Buildings | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 |

| No Violations, Litigation | 1,406 | 679 | 631 | 226 | 320 |

| Violations, No Litigation | 529 | 1,470 | 1,337 | 1,977 | 2,506 |

| Litigation and Violation | 2,802 | 1,632 | 1,130 | 568 | 836 |

To be sure, a backlog of cases because of court closures during the pandemic has limited the Court’s capacity to adjudicate orders to correct violations in a timely manner. However, despite the delays in closing HPD litigation, the Court continues to rapidly dispose of cases seeking tenant evictions (which are concentrated in the same neighborhoods).

New York City Residential Eviction Filings by Zip Code, 2022

Total Heat and Hot Water Violations, 2017-2021 Heat Seasons

Total Heat and Hot Water Complaints, 2017-2021 Heat Seasons

Litigation is an effective code enforcement tool: buildings subject to litigation see a steep drop in heat-related tenant complaints in the following heat season. The average number of complaints at buildings in which at least one case was initiated during the 2017 – 2020 heat seasons was 17.2. In the heat season following the heat season in which the litigation was initiated the average number of complaints dropped to 9.4 complaints, a 45% drop. The median number of complaints made in the same heat season in which HPD initiated litigation was 7.5 and, in the year, following, that number dropped to 1.5, or by 80%.

Publicly available data does not indicate how many of these cases result in civil penalties, the amount of the fines, or the collection rates. A New York State Comptroller’s 2019 audit provided additional information about a small sample size of cases in their 2018 – 2019 observation period. Of the 25 cases they analyzed, 4 were dismissed after the violations were corrected and 21 cases moved through the Housing Court process. Among the 21 cases, HPD reached a settlement with 13 owners, 4 were withdrawn, and 4 resulted in default judgements totaling $184,550.[9] A July, 2022 update by the State Comptroller found that as of the end of March 2022, HPD had yet to collect any of the $1.43 million in default judgements issued in 2021 and that the judgements had been outstanding for on average 243 days.[10]

Emergency Repair Program

If an owner fails to restore heat after a violation has been issued, the City may contract with vendors to do the necessary repair work, or HPD staff make the repairs themselves, under the City’s Emergency Repair Program (ERP). The cost of the repairs is billed to the owner through the Department of Finance; if the owner fails to pay, the fines can be placed as a lien against the building.

Emergency Repair Program enforcement is also an effective strategy. Our analysis of available data indicate that ERP repairs related to a heating system were made in 7,330 buildings between the 2017 and 2020 heat seasons. The average number of complaints at buildings in which HPD or outside vendors made repairs during the 2017 – 2020 heat seasons is 9.7. In the heat season following the year in which the repairs were made that average drops to 6.0 complaints, a 38% drop. The median number of complaints made in the same heat season in which the city or an outside vendor made repairs is 4.1 and, in the year, following, that number drops to 0.5, or an 88% drop.

Heat Sensor Program

Local Law 18 of 2020 requires HPD to identify 50 buildings every two years that have a significant history of heat complaints and violations.[11] The owners of those buildings are required to install a heat sensor in the living room of every unit in the building by the beginning of the heat season in which the property is selected for the program. Tenants can opt-out of the program if they so wish after they are notified by the owner. In addition to collecting data on the temperature of the apartment, HPD conducts an inspection of the building every two weeks, regardless of whether any heat complaints are made by tenants. The building remains in the program for four years; however, an owner may request to be discharged from the program sooner if they can demonstrate that they have taken permanent action to improve the provision of heat, or if HPD did not issue any violations in the preceding heat season. HPD may also elect to cease the bi-weekly inspections if no violations are found by January 31.

Among the 50 buildings in the program: 8,818 complaints were made by tenants reporting a lack of heat, 473 violations were issued, 151 litigations initiated, and 36 buildings had repairs related to the heating systems during the 2017 – 2021 heat seasons.

Given the nascency of the program, the data on the reduction of heat complaints following the installation of the sensors is limited, but promising. We found that there were 45 complaints on average in the three years prior to the installation of the heat sensors and in the two heat seasons following installation the number of complaints was reduced to 20.5, a 54% drop. The median number of complaints was 21 in the prior year and reduced to 8 in the year following installation, representing a 62% reduction.

However, the 2022 update to the 2019 New York State Comptroller’s audit of the City’s heat code enforcement system found that the effectiveness of this program has been limited by landlords’ failure to comply – noting that 56% of the buildings in the Bronx (10 out of 18) did not install the heat sensors required by the law.[12] In order for this program to be successful the City should work directly with tenants to educate them on the heat sensor technology and its benefits, install them directly in the apartments of residents if owners fail to do so and bill the owner for the cost. In addition, there should be meaningful escalatory actions against landlords for failure to comply with the law.

Complaints Do Not Recur Significantly in Most Buildings

During the 2017 – 2021 heat seasons, heat complaints were made by tenants living in 70,766 unique buildings. On an annual basis, complaints made by tenants regarding a lack of heat, come from an average of 29,000 buildings.

In the vast majority of cases, heat complaints do not recur in the same buildings. Over this period, 78% of heat complaints come from buildings in which there were 5 or fewer complaints made in the same heat season, and nearly 90% of heat complaints came from buildings in which there were 10 or fewer heat complaints made in the same heat season. While it is hard to know for certain, the nonrecurrence of complaints suggest that in most cases, tenant complaints about a lack of heat to 311 trigger a code enforcement process that results in the issue being resolved.[ix]

Complaints & Violations, Totals & Building Totals

| Heat Season | Total Complaints | Unique Buildings with Complaints | Total Violations | Unique Buildings with Violations |

| Oct. 2017 – May 2018 | 192,512 | 32,092 | 4,757 | 3,331 |

| Oct. 2018 – May 2019 | 183,534 | 29,247 | 4,562 | 3,102 |

| Oct. 2019 – May 2020 | 148,279 | 25,521 | 3,553 | 2,467 |

| Oct. 2020 – May 2021 | 155,176 | 27,132 | 3,857 | 2,545 |

| Oct. 2021 – May 2022 | 135,041 | 25,540 | 4,881 | 3,342 |

Persistent Bad Actors

However, a lack of heat is persistent and severe in a small percentage of buildings. While no tenant should have to live without essential services for any amount of time, a temporary outage of heat is a very different experience than spending months, or in some cases years, in a cold apartment.

A consistently cold home has been proven to cause negative health impacts, particularly for individuals with existing health conditions, children, and the elderly. Residents living in a cold home are at higher risk of respiratory illnesses, increased blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease.[13] In addition to physical health impacts, living for a long time in a home without heat can lead to social isolation, loss of sleep and a decline in mental health, including increased risk for anxiety and depression.[14] Tenants may resort to unsafe options such as portable, electric heaters or temporary use of their electric or natural gas stoves to warm their homes. Both of these methods pose serious fire risks, in addition to carbon monoxide hazards that can have both acute and long-term effects.[15]

On average, each heat season there are 6,170 unique buildings in which tenants complain about a lack of heat more than five times and 3,572 buildings unique buildings in which tenants complain about a lack of heat more than 10 times. There are, on average only 1,357 buildings each year in which tenants complain about a lack of heat more than 20 times.

Complaints Received by Building in a Heat Season

| Complaints | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 |

| 5 or fewer | 24,665 | 22,414 | 20,103 | 21,210 | 20,290 |

| 6 to 10 | 3,560 | 3,231 | 2,601 | 2,883 | 2,603 |

| 11 to 20 | 2,204 | 2,014 | 1,616 | 1,785 | 1,569 |

| More than 20 | 1,663 | 1,588 | 1,201 | 1,254 | 1,078 |

Analysis of Buildings with Persistent Heat Complaints

In order to better understand patterns of persistent heat complaints over the five-year observation period, we created a dataset of buildings in which tenants complained more than 5 times each heat season. [x] 1,077 buildings meet this criterion.

Buildings with Persistent Complaints, 2017-2021 Heat Season

During the 2017 – 2021 heat seasons, 244,176, or 30% of the total 814,542 heat complaints made across New York City, were made by the residents living in just these 1,077 buildings (which represent just 1.5% of the buildings from which complaints were made). Of the 1,077 buildings with persistent heat complaints, 803 of the buildings had at least one of the four interventions examined during the five-year period (primarily violations and litigation). 2,022 violations were issued to owners of 661 of the 1,077 buildings. 1,214 litigations were initiated against owners of 603 of the 1,077 buildings. However, 274 buildings, over 25% in the chronically troubled buildings dataset, did not have any interventions related to an inadequate supply of heat from the City.

Buildings with at Least One Intervention in 5 Years of Study

| 2017 - 2022 Experience | Buildings with Intervention | Buildings Without Intervention |

| Violation | 661 | 416 |

| Litigation | 603 | 474 |

| Contracted Repair | 241 | 836 |

| HPD Repair | 127 | 950 |

| Heat Sensor Program | 43 | 1,034 |

| No Intervention | 803 | 274 |

Despite these ongoing, and in some cases escalated enforcement actions, tenants continue to complain about a lack of heat in their homes. As the map and chart make clear, these buildings are not equally distributed across the city but rather are predominantly clustered in the Northwest and South Bronx, Central and Eastern Brooklyn, and Washington Heights, Inwood, and Harlem.

Community District Locations of Buildings with Persistent Complaints

| Community District | Number of Buildings |

| Bronx 07 | 103 |

| Bronx 4 | 86 |

| Manhattan 12 | 69 |

| Bronx 5 | 64 |

| Brooklyn 14 | 60 |

| Brooklyn 9 | 57 |

| Brooklyn 17 | 50 |

| Bronx 8 | 43 |

| Bronx 9 | 39 |

| Manhattan 10 | 37 |

Historic Disinvestment and Speculation

Heat complaints, violations, and buildings with persistent heat problems are predominant in areas of the city in which a majority of the residents are people of color. The five community districts with the highest volume of 311 complaints related to a lack of heat are in Northern Manhattan, the Northwest Bronx, and Eastern Brooklyn. On average these community districts are 93% people of color. The five community districts with the most heat related violations, located in similar areas, are 89% people of color.[xi]

Many of these neighborhoods were subject to redlining in the late 1930s, which limited the ability for homeowners and landlords to receive low-cost, low-risk mortgages.[16] This practice, in addition, to a myriad other policy decisions and economic factors, led to a serious decline in the [physical] condition of many buildings in communities of color. In New York City, this disinvestment resulted in landlord abandonment and arson and high levels of municipal foreclosure of privately-owned buildings.

While much has changed in New York City’s housing market in recent decades, problems of chronic disrepair, including a lack of consistently provided heat, persist as an issue for many residents. But rather than abandonment, a lack of basic maintenance is often now coupled with high sales prices, large mortgages, and upward rent pressure.

A recent report from University Neighborhood Housing Program (UNHP), a Bronx based housing organization, and Local initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) found that buildings that were sold for the greatest price increases, or that took on the greatest amount of additional debt, had significantly more violations per unit than those that did not.[17] The report also makes clear that landlords who purchased their buildings at speculative prices or took on high levels of debt were more likely to successfully evict tenants.

The finding that taking on more debt is an indicator of poorer maintenance quality and increased evictions runs counterintuitive to the notion that increased investment in multifamily buildings automatically benefits existing tenants and improves housing quality. Additionally, the report found that multifamily buildings were most likely to be resold for the greatest increase in price in neighborhoods with higher levels of poverty, higher black and Latino populations, and a higher percentage of adults who have obtained college degrees. Indicators that the authors believe correlate with current patterns of gentrification. Making clear that, simply facilitating investment in multifamily buildings in previously disinvested communities will not necessarily improve physical conditions and may in fact worsen them. Both effective code enforcement and tenant protections play an integral role in ensuring that landlords re-invest rent and capital into their buildings and treat properties as more than just investment vehicles but as homes.

Barriers to Effective Enforcement & Recommendations

Difficulty Getting Violations Recorded

This report’s analysis found that violations are typically an effective method of code enforcement, resulting in an average 46% decline in heat complaints in the heat season following the year in which the violation was issued. However, the extremely low conversion rate of complaints to violations, just about 3%, makes clear the level of difficulty that many residents face when trying to get the heat restored in their homes. There are several factors that make the process of getting a violation recorded challenging for tenants and limit the effectiveness of heat code enforcement.

Timing of Inspections

Unlike peeling paint, a broken door jamb, or leaking faucet, the provision of heat is variable over time and across apartments in a multifamily building. Responding to heat complaints in a timely manner is therefore essential to HPD’s ability to capture the point of time at which it is not being adequately provided. Further, some organized tenants have claimed – as did several interviewed during the State Comptroller’s 2019 audit – that building owners temporarily turn the heat on in advance of an inspection in order to evade violations, shutting it off shortly after the inspection and beginning anew tenants’ herculean effort to get a violation recorded.[18] HPD has stated that they have an informal internal standard of addressing heat related complaints within 26 hours of receiving them.[19] The State Comptroller’s 2019 audit found that on average HPD responded to heat complaints in 3.1 days in 2018 and 2.1 days in 2019. An August 2022 follow-up states that the inspections continue to occur, on average, within 2 days from when a lack of heat is reported.

HPD has consistently rejected recommendations from both New York City and New York State Comptrollers, and other tenant advocate organizations, to establish formal timeframes for the resolution of heat complaints.[20] Given the volume of heat related complaints, there are practical limitations on how quickly code inspectors can respond to each complaint, but the use of data and technology to route inspectors to buildings with chronic heat issues can address capacity concerns.

Lack of Tenant Notification of Inspection

Tenants are not able to schedule and do not receive advance notice of inspections. While the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the number of New Yorkers who are working from home, many residents are not available during the day to grant access to their apartments for inspection. Without advance notice, residents cannot properly plan to provide access to their homes. This is likely to be especially true in low-income neighborhoods, in which heat complaints predominate, where fewer people have jobs that allow them to work from home.[21]

A 2015 audit by the New York City Comptroller found that antiquated computer systems required inspectors to return to the office each day to perform data entry, limiting staff effectiveness and the time that inspectors could spend in the field.[22] Technology upgrades made over the past 7 years, most significantly the recent implementation of Real Time Field Force (RTFF) technology, have greatly improved HPD’s ability to efficaciously meet its mission.

Thus far, there is limited, publicly available data on the details of this technology, but HPD reports that the software allows inspectors to initiate and close inspections in the field and to upload more detailed information. It also allows for code inspectors to receive assignments when they are out in the field rather than receiving a route sheet each morning from their borough office. However, RTFF technology does not currently provide contact information to inspectors’ until they initiate the building inspection, limiting the ability to give tenants’ advance notice.[23]

Providing advance notice to tenants would lower the frequency of times that inspectors are unable to gain access to apartments, increase the utility of code inspectors’ time, and limit tenant frustrations over consistently missing HPD staff.

Duplicate Complaints

The manner by which heat complaints are currently collapsed into one “initial complaint” may obscure how well heat is being provided in each apartment in the building. There are many factors that may make the distribution of heat in a building uneven, but HPD’s current process does not adequately account for this nuance. This means the system cannot always effectively distinguish instances when individual apartments are persistently cold from the broadest problems. Given the number of heat-related 311 complaints, some level of grouping is necessary in order to avoid multiple inspectors being sent to the same buildings, but data-informed inspections may make the process more effective, particularly in buildings with chronic and severe levels of heat complaints.[xii]

It is unclear what information code inspectors have related to the history of heat complaints when they arrive at a building for an inspection, but a code inspector should have comprehensive data on what units have been grouped into the initial complaint and how many times complaints for a lack of heat have been made by each tenant and during which time of day. Inspectors can then use their time more efficiently, inspecting multiple apartments in one visit instead of coming back the following day or week when a different unit files the first complaint and is listed as the initial complainant.

Recommendations: Use data & technology to inform and prioritize inspections with a focus on buildings with persistent heat complaints

- Provide code inspectors with comprehensive information about the history of heat complaints of each building they inspect. This should include the number of complaints made in the current and previous heat seasons and from which apartments and during which time of day. This information should inform their inspections and time should be allocated appropriately depending on the severity of the history of complaints.

- Build on this report’s analysis to create and further refine a database of “buildings with persistent heat complaints” to prioritize inspections and proactive code enforcement strategies. While the analysis in this report has defined persistent heat complaints to include the buildings in which tenants complained more than 5 times each heat season between 2017 and 2021, there are countless ways to create a similar dataset aimed at locating the buildings in which tenants are consistently complaining about a lack of heat. The City should conduct additional and variable data analysis to further refine this definition. That universe of buildings should then be used to inform the City’s design of programs and interventions to alleviate lack of heat and better hold landlords accountable. For buildings with persistent heat complaints, defined in this report as the 1,077 buildings in which tenants complained more than 5 times each heat season between 2017 and 2021, which are responsible for 30% of all heat complaints over that same period:

- Pass Int. 434 of 2022 (sponsored by Council Member Sanchez), which expands the Heat Sensor Program and enforces landlord compliance. Consider covering all buildings with persistent heat complaints by the Heat Sensor Program.

- Require the City to proactively inspect buildings with persistent heat complaints. The new Real Time Field Force (RTFF) technology should also be used to quickly route inspectors to these buildings and reduce the time it takes to conduct a physical inspection.

- Allow tenants living in buildings with a history of persistent heat complaints to schedule inspections within a window of time in which it is typically most cold in their apartments. These inspections should not trigger landlord notification and tenants should be allowed to schedule them overnight.

Lack of Holistic Information about the Building

The existing framework of code enforcement addresses episodic heat complaints from the large majority of buildings; however, it does not result in a sufficiently strategic or coordinated approach to resolve heat issues in buildings with persistent complaints. The City needs a more holistic, data-informed, strategic approach to focus more attention on the worst buildings, identify the barriers that are preventing the consistent delivery of adequate heat, and then develop and implement a plan to work with landlords willing to correct conditions, compel recalcitrant ones to address the issues, or seek ownership transfer in the worst cases.

Buildings in which tenants persistently complain about a lack of heat should be subject to a joint HPD and DOB inspection of the central heating and distribution systems. This inspection should seek to determine the various causes of the outage. For example, is the boiler defective and in need of major or minor repairs, is the distribution system the problem, does the super or property manager have the training needed to properly run the system, do the radiators need to be bled, are there enough funds to pay for heating fuel, are energy inefficient windows in certain units the primary cause, or is there no physical reason for a lack of heat despite frequent tenant complaints? Given the wide array of underlying, and often co-occurring problems that may be causing a persistent lack of heat, better information is essential in order locate the source and to determine the best course of action.

Next, HPD should contact the owner of the property to determine what barriers are impeding their ability to consistently provide an adequate supply of heat. Landlords who state that they do not have the funds necessary to make repairs should be referred to community organizations that can help them apply for Weatherization Assistance Programs or HPD loan programs, which both provide low-cost financing and tax exemptions (along with a regulatory framework to ensure that funds are invested into the building as agreed-upon and that tenant protections are in place). Landlords who are working cooperatively with HPD towards an outcome that addresses the underlying issue but may not be able to afford to cost of heating fuel in the short term may also be eligible for City programs that arrange for the delivery and cover the cost of fuel.

Recommendations: Conduct comprehensive site inspections and identify landlords’ willingness to comply

- Conduct joint HPD and DOB inspections of central heating and distributions systems in buildings with persistent heat complaints. This inspection should seek to determine the causes of the outage and be a guiding document for HPD’s enforcement approach.

- Contact the owner of the property to determine the barriers impeding their ability to consistently provide an adequate supply of heat. Where owners are willing to cooperate, make referrals to City and State programs that provide resources and oversight to achieve repairs. Consider requiring that owners of property submit a description of the conditions causing the violation when filing a certification of correction for heat code violations.

Failure to Address Underlying Causes

If landlords fail to correct the underlying conditions that are causing a persistent lack of heat, are uninterested in the programs, or do not meet program milestones that demonstrate progress, HPD must use other enforcement tools, such as ERP and the 7A Program to directly make the repairs. Pursuant to New York State law HPD can seek the appointment of a 7A administrator if privately-owned buildings have conditions that are dangerous to tenants’ health and safety. The 7A administrator, takes over operation of the building, collecting tenants’ rent and managing the property. Through this program, HPD can also make repairs to or replace major systems, such as a boiler.[xiii]

It is unclear based on publicly available data how the City makes decisions about how to use ERP or initiate 7A cases, but information provided by community organizations suggests that when either program is used, the repairs do not always address the underlying issue. Rather than temporary fixes or scattershot repairs, the city should comprehensively address the issue after a significant investigation that locates the root of the problem, following a landlord’s failure to address it.

Local Law 6 of 2013 gave HPD the power to issue an administrative order to correct underlying conditions that are causing violations of the Housing and Maintenance Code of New York City. While the current HPD rules limit the program to addressing mold or leaks, such limitation does not exist in the authorizing law. Upon either HPD-initiated amendments to those rules, or City Council legislation to explicitly require HPD to do so, this program could be expanded to address underlying issues related to heat.

As per the rules of these programs, the cost of the repairs should be billed to the property owners through their Department of Finance property tax bills. If the owner fails to pay those liens, and continues to neglect the property, the City should work with not-for-profit “preservation purchasers” who may be interested in purchasing the building, overseeing any additional rehabilitation that is necessary, and owning and operating the building as affordable housing in perpetuity.

Recommendation: Expand Proactive Code Enforcement and Targeted Escalation

- Use the Emergency Repair Program (ERP) or the 7A Program, in appropriate instances, to make comprehensive repairs needed to ensure the adequate supply of heat to tenants if landlords do not meet milestones that demonstrate progress.

- Amend the rules enacting Local Law 6 of 2013 (whose lead sponsor was Council Member Gale Brewer), either through HPD-initiated rule amendment, or City Council legislation, to give HPD the power and responsibility to issue an administrative order to landlords to correct underlying conditions that are causing heat violations.

- Pass Int. 583 of 2022 (sponsored by Public Advocate Jumaane Williams), which would increase the penalties for many Housing and Maintenance Code violations and would require HPD to create an annual certification of correction watchlist. HPD would be required to re-inspect any violation to ensure that it was properly addressed by the owner prior to resolution (currently, owner self-certification is allowed).

- Where owners continually fail to address hazardous living conditions and are non-responsive to escalated enforcement strategies, offer preservation purchases (e.g. through HPD’s Neighborhood Pillars program), where buildings are acquired by not-for-profit developers as affordable housing and renovated as necessary.

Reliance on Tenant Complaints

New Yorkers may be scared to file 311 complaints because they fear reprisal from their landlord, including retaliatory evictions, further denial of service, and where they are undocumented, immigration enforcement. Rent regulation provides tenants with the peace of mind that advocating for their health and safety won’t result in retaliatory evictions, but most tenants in New York City live in unregulated units and do not have a right to a renewal lease. With a vacancy rate of less than 1% for apartments that rent below $1,500,[24] many New Yorkers may be choosing to live in unsafe apartments rather than complain and risk homelessness. Tenants in New York City can currently make anonymous complaints about building-wide conditions, such as a lack of heat, but many may not know about this option or may be unaware of their rights, particularly if English is not their first language or if they are recent immigrants.

Recommendations: Expand tenants’ rights and education

- Expand multilingual direct outreach to tenants, particularly in neighborhoods with large numbers of residents who are foreign-born.

- Fund community organizations that educate and assist tenants in asserting their rights.

- Pass, S3082/A5573, which would provide “Good Cause” evictions protections, guarantee renewal leases, and reduce fears of retaliatory evictions for reporting unsafe conditions.

Conclusion

New York City has a long history of organizing for fire prevention and tenant protections to address the longstanding prevalence and devastating effects of residential fires. Unfortunately, under-resourced code enforcement has hamstrung the effectiveness of housing and buildings standards since the original tenement laws were passed in the mid-19th century. The City’s active strategies for addressing heat complaints are generally effective when they are deployed. However, they are not deployed in many eligible cases, and the strategic rationale for their deployment is unclear. This report’s analysis makes evident that it is not enough to simply have rules on the books – to effectively enforce the City’s heat code the City must take a more coordinated and strategic approach to resolving heat complaints. Stronger data-driven code enforcement, in addition to tenant protections, is necessary to compel landlords, especially those with low-income, immigrant, and tenants of color, to treat the properties they own not just as an investment vehicle, but as people’s homes.

Methodology

The Comptroller’s Office drew from datasets published by the Office of Housing, Preservation & Development on the city’s Open Data portal to serve as the foundation of data for this report. The figures reported are the result of the following inquiries:

- Housing Maintenance Code Complaints | NYC Open Data (cityofnewyork.us) – Accessed in November 2022. Date Field: ReceivedDate

- Complaint Problems | NYC Open Data (cityofnewyork.us)- Accessed in November 2022

- Housing Maintenance Code Violations | NYC Open Data (cityofnewyork.us)- Accessed in November 2022. Date Field: ApprovedDate

- Housing Litigations | NYC Open Data (cityofnewyork.us)- Accessed in November 2022. Date Field: CaseOpenDate

- Handyman Work Order (HWO) Charges | NYC Open Data (cityofnewyork.us) – Accessed in December 2022. Date Field: HWOCreateDate

- Open Market Order (OMO) Charges | NYC Open Data (cityofnewyork.us)- Accessed in December 2022. Date Field: OMOCreateDate

The universe of residences in these data are limited to privately held properties; complaints in NYCHA facilities are not included. Each of these data were filtered to include only entries recorded after July 1st, 2017. The Housing Maintenance Code Complaints dataset was merged with the Complaint Problems dataset on Complaint ID and filtered to include only Problem Codes pertaining to lack of heat and/or hot water (CodeIDs 2713, 2715, 2716, 2833). Entries in the Complaint Problems data without a matching ComplaintID were excluded from the analysis, representing approximately 8 percent of entries. The resulting data were further de-duplicated to result in a single entry per Complaint ID. HPD will often group individual calls to 311 under a single ComplaintID when the complaints relate to a similar concern close in time. In a 2019 audit, the Office of the State Comptroller noted several thousand instances in which complaints were likely erroneously grouped under a single complaint ID when they took place weeks or years apart. In subsequent audit responses, HPD indicated that they have made numerous system improvements to prevent this from happening in the future.

The OMO and HWO datasets were filtered to only include WorkTypeGeneral fields “7AFA”, “ELEC”, “HEAT”, “PLUMB”, “STOPAG”, and “UTIL”, all of which contained substantial instances of heat and hot water repairs conducted by contractors or employees of HPD.

The Comptroller’s Office qualitatively consolidated 20 unique dispositions in the Complaint Problems dataset’s field StatusDescription into 6 categories according to whether a complaint resulted in Contact or Inspection, and if the matter was Corrected, concluded with No Access, or a Violation Issued/Not Issued.

All data were associated with a Heat Season beginning on June 1st and concluding on May 31st according to the Date Field listed above. For example, a violation with an ApprovedDate of November 15th, 2017 would be associated with the 2017-18 Heat Season. A full list of all BuildingIDs present in any dataset was created, and counts were taken for each record for each Heat Season that received a complaint, violation, or other intervention by HPD.

Geographic data were matched to Pluto 22v3 by matching Borough and Block Lot (BBL) to associate Buildings with Latitude and Longitude coordinates. There are a small number of duplicate records created by the process of matching Building IDs to BBLs, as HPD records are inconsistent over time, sometimes attributing a Building ID to the address of the subject building, and in other cases to an address for the owner of record, as discovered through the data validation process. Where duplicate records were generated, results were de-duplicated by Building ID. Total complaints and violations at the building level were aggregated at the community district level and summed to create a single five-year total for Community District maps. Map visuals were created in ArcMap, ArcGIS Pro, and ArcGIS Online.

Acknowledgements

Celeste Hornbach, Director of Housing Policy, was the lead author of this report with support from Robert Callahan, Director of Policy Analytics and Annie Levers, Assistant Comptroller for Policy. The data analysis was led by Robert Callahan, Director of Policy Analytics with support from Jacob Bogitsh, Senior Policy Analyst. Report design was completed by Archer Hutchinson, Graphic Designer. Additional graphics support provided by the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development. Outreach to stakeholders was conducted by Nicole Krishtul, Strategic Housing Organizer and Louis Cholden-Brown, Senior Advisor & Special Counsel for Policy and Innovation provided expertise throughout.

Thank you to the Gambian Youth Organization, the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition, Heat Seek, Saint Nicks Alliance, and Cooper Square for generously providing your time and expertise.

Endnotes

[1] “Recovering Emotionally after a Residential Fire.” American Psychological Association. American Psychological Association, 2013. https://www.apa.org/topics/disasters-response/residential-fire.

[2] “Council Votes on Legislative Package to Strengthen Fire Safety Inspired by Tragic Twin Parks Fire in Bronx.” New York City Council, 19 May 2022. https://council.nyc.gov/press/2022/05/19/2186/.

[3] Bureau of Audit, “Audit Report on the Department of Housing Preservation and Development’s Handling of Housing Maintenance Complaints, ME13-106A.” New York City Comptroller, June 30, 2015. https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/audit-report-on-the-department-of-housing-preservation-and-developments-handling-of-housing-maintenance-complaints/

[4] “Emergency Repair Program.” New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, Accessed January 6, 2023. https://www.nyc.gov/site/hpd/services-and-information/emergency-repair-program-erp.page.

[5] Bureau of Policy, “Title Vacant: Addressing Critical Vacancies in NYC Government Agencies.” New York City Comptroller, December 6, 2022. https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/title-vacant/.

[6] “ABCs of Housing.” New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, Accessed January 6, 2023. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/hpd/downloads/pdfs/services/abcs-of-housing.pdf.

[7] NYC Comptroller Bureau of Audit, Report ME13-106A

[8] “Heat and Hot Water.” New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, Accessed January 6, 2023. https://www.nyc.gov/site/hpd/services-and-information/heat-and-hot-water-information.page.

[9] Division of State Government Accountability, “New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development: Heat and Hot Water Complaints 2019-N-3” New York State Comptroller, September, 2020. https://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/state-agencies/audits/pdf/sga-2020-19n3.pdf.

[10] Division of State Government Accountability, "30-Day Response to Heat and Hot Water Complaints Report 2022-F-3.” New York State Comptroller, July 13, 2022. https://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/state-agencies/audits/pdf/sga-2022-22f3.pdf.

[11] “Heat Sensors Program.” New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, Accessed January 6, 2023. https://www.nyc.gov/site/hpd/services-and-information/heat-sensors-program.page#:~:text=HPD%20will%20conduct%20inspections%20during,compliance%20with%20the%20heat%20requirements.

[12] New York State Comptroller, Report 2019-N-3

[13] “Advice Leaflets,” Centre for Sustainable Energy, Accessed January 6, 2023. www.cse.org.uk/advice-leaflets.

[14] Baraniuk, Chris. “Energy crisis: How living in a cold home affects your health.” BBC, November 7, 2022, www.bbc.com/future/article/20221107-energy-crisis-how-living-in-a-cold-home-affects-your-health.

[15] “Carbon Monoxide Poisoning.” Mayo Clinic, 16 Oct. 2019, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/carbon-monoxide/symptoms-causes/syc-20370642.

[16] Nelson, Robert K. and Edward L. Ayers, “Mapping Inequality.” American Panorama, Accessed January 6, 2023. https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=12/40.654/-74.064&mapview=graded&city=brooklyn-ny&area=D3&text=downloads&adimage=2/40/-152.903

[17] Greenberg, David M. et al, "Gambling with Homes, or Investing in Communities.” Local Initiatives Support Corporation, March, 2022. https://unhp.org/pdf/Gambling_with_Homes.pdf

[18] New York State Comptroller, Report 2019-N-3

[19] NYC Comptroller Bureau of Audit, Report ME13-106A

[20] Andre, Astrid and Office of the Public Advocate, “Inequitable Enforcement: The Crisis of Housing Code Enforcement in New York City.” Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development, July 1, 2008. https://anhd.org/report/inequitable-enforcement-crisis-housing-code-enforcement-new-york-city

[21] “New York City’s Frontline Workers,” New York City Comptroller, March 26, 2020, https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/new-york-citys-frontline-workers/.

[22] NYC Comptroller Bureau of Audit, Report ME13-106A

[23] Solomon, Aida et al, "Heat and Hot Water Complaints Report 2022-F-3,” New York State Comptroller, July 13, 2022, https://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/state-agencies/audits/pdf/sga-2022-22f3.pdf.