Audit on the Effectiveness of the Mayor’s Office of Housing Recovery Operations’ Build It Back Program

Audit Impact

Summary of Findings

The audit was conducted to determine whether the Build It Back Program achieved its goal of assisting property owners who were affected by Hurricane Sandy. In addition, the audit determined whether the Program made Sandy-affected New Yorkers and communities safer and more resilient.

The audit found that the Mayor’s Office of Housing Recovery Operations (HRO) served 36% of those applicants who initially applied to participate in the program and took protracted periods of time to process applications and to begin construction. On average, construction projects took three years to complete from the date an application was submitted to the date construction finished. The audit also found that HRO did not meet its stated goal of finishing construction by the end of 2016, with nearly 1,600 (40.1%) homes not completed by this time. Further, the introduction of new deadline and acceleration initiatives failed to reduce overall construction completion times.

Intended Benefits

This audit assessed the timeliness and appropriateness of construction services provided by HRO to homeowners affected by Hurricane Sandy. The audit identified several significant issues with the BIB Program including weaknesses in HRO’s application and construction management processes that caused delays in the overall construction timeline.

The audit identified the need to establish and document program timeframes and deadlines at the beginning of a program and to track performance indicators in the recordkeeping system, including timeliness for contractors responsible for application processing and construction management to improve future disaster recovery programs.

Introduction

Background

In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy damaged or destroyed over 17,000 homes in New York City. In the storm’s aftermath in November 2012, the City established the Mayor’s Office of Housing Recovery Operations (HRO) to coordinate recovery efforts.

In June 2013, HRO launched the Build It Back (BIB) Program to meet the repair and reconstruction needs of New Yorkers impacted by the storm. By October 2013, registration for the Program closed. Construction began in March 2014, and by August 2014, HRO completed its first home rebuilding project and started the first home elevation project. In October 2015, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that the Program’s goal was to complete construction by the end of 2016.

The BIB Program covered different types of structures and homes and included multiple processes that changed over time. This audit concentrated on aspects of the BIB Program specific to construction and rehabilitation of single-family homes, as detailed in Appendix I. The BIB Program is now complete and HRO is currently in the process of conducting the final HUD grant closeout, which includes a review of homeowners who received assistance from the Program to ensure that files contain all information required to support the use of federal funds.

BIB Single-Family Program Mission and Goals

HRO created the BIB Single-Family Program to help homeowners, landlords, renters, and tenants within the five boroughs affected by Hurricane Sandy. Specifically, the Program was designed to assist homeowners and other occupants of one-to-four-unit residential properties seeking repair or reimbursement (or a combination of the two), or reconstruction assistance. Both owner-occupied and tenant-occupied properties were eligible for assistance.[1]

The Program sought to repair or rebuild homes of Sandy-affected New Yorkers and make communities safer, more resilient, and better able to withstand future storms. This was primarily achieved by either elevating entire home structures or elevating home utilities above the floodplain. As seen in Figure 1 below, eligible homes were required to be elevated above grade.[2]

Elevation heights are based on the boundaries of the City’s 100-year floodplain, which has a 1% chance of flooding in any given year. According to HRO, in the hardest hit waterfront communities, homes were often elevated 10 to 14 feet.

In some cases, eligible storm-damaged properties in selected areas were purchased by the State or the City. On these sites, future development could be permanently restricted, and the sites could be used as open green space, such as parks, wetlands, wildlife management areas, and beaches. These areas could help mitigate the impacts of future flooding by creating additional space to absorb floodwater.

HRO was responsible for implementing and managing the BIB Program and delivering certain benefits to eligible applicants. HRO managed the Program in coordination with the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), NYC Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), NYC Department of Design and Construction (DDC), NYC Economic Development Corporation (EDC), and NYC Human Resources Administration (HRA).[3] [4]

Figure 1: Elevated Home Before and After Elevation

Source: HRO, Completing The Build It Back Program

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) Program allocated $2.3 billion in funding for the BIB Single-Family Program. The entire allocated amount has been reimbursed to the City as of July 2025 but is still subject to HUD’s Program closeout review. The City, which is the grant recipient, designated the NYC Office of Management and Budget (OMB) as the grant administrator, and HRO as the BIB Program administrator.

As with other federal recovery grants, the City paid upfront for costs associated with grant-funded activities and was later reimbursed. In addition, the City allocated its own resources towards the BIB Program. According to OMB, the City has spent a total of $2,536,305,321 on the BIB Single Family Program. OMB stated that this figure is preliminary, and the City is actively reviewing Program expenditures as part of the closeout process.

Pathways for Assistance for Sandy-Impacted New Yorkers

According to HRO, BIB provided six options, or pathways, for assistance:

- Repair (Moderate Rehabilitation): If an applicant’s home was damaged by Hurricane Sandy, the BIB Program completed any remaining repairs.

- Repair with Elevation (Major Rehabilitation): If an applicant’s home was substantially damaged or could be substantially improved within the scope of the Program, BIB completed any remaining repairs and raised the home to comply with flood elevation standards.

- Rebuild (Reconstruction): If an applicant’s home was demolished or damaged beyond repair, BIB built a new home that was elevated and included resiliency improvements such as elevating all utilities, incorporating mold and salt resistant construction materials, and installing emergency generator connections.

- Reimbursement Only: If an applicant made repairs to their homes or had work completed by a contractor, BIB reimbursed their expenses.[5]

- Acquisition (Redevelopment):

- New York City Acquisition for Redevelopment (AFR): Storm-damaged property was purchased by the Program and set aside for future residential redevelopment or retained by the City for public purposes.

- New York State AFR: Storm-damaged property was purchased by the State.

- Buyouts (Returned to Nature):

- New York City Buyout: Storm-damaged property was purchased by the Program so that future development on the site could be restricted for uses that would mitigate future storm/flood risks.

- Breezy Point Cooperative/Edgewater Park Cooperative: A resettlement grant was earmarked for owners of storm-damaged homes in Breezy Point (Queens) and Edgewater Park (Bronx) to help impacted residents relocate to new homes situated outside of their respective cooperative housing communities.

Application Process

Before the BIB Program could deliver benefits, Sandy-impacted property owners were required to go through an application process. HRO was required to follow certain federal rules and regulations, ensuring, among other things, that:

- Applicants met BIB Program eligibility standards, such as ownership, primary residency, National Flood Insurance Program coverage (for Repair and Reconstruction projects only), property location, Hurricane Sandy damage, structure type,;

- Residential units were elevated according to requirements; and

- Projects complied with the National Environmental Policy Act and other federal, State, and local environmental rules.

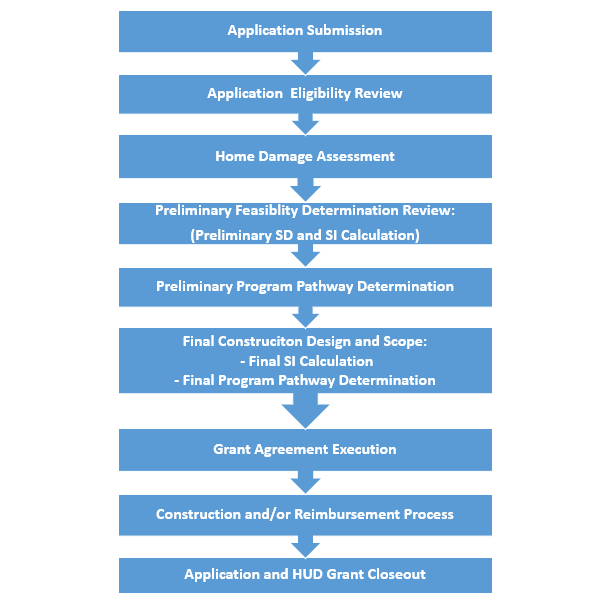

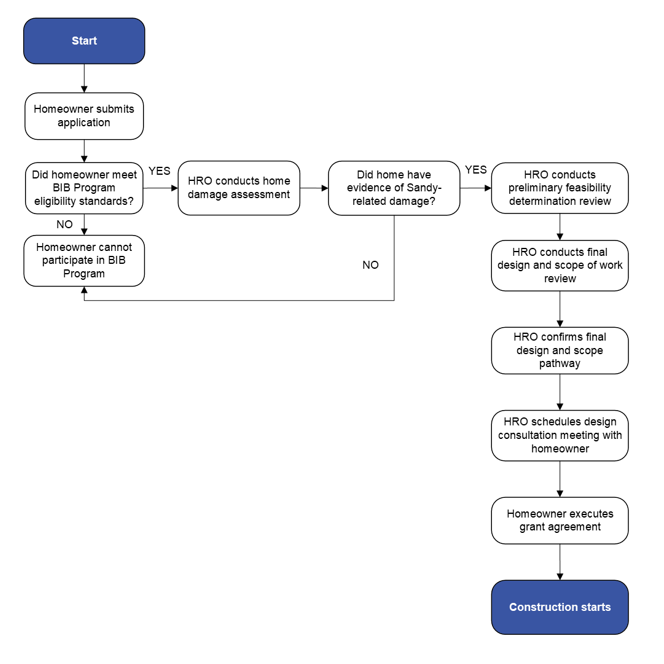

The application process, also outlined in Appendix II, was as follows.

Damage Assessment

HRO contractors conducted a Damage Assessment of the applicant’s home. The primary purpose of the Damage Assessment was to gather data for the Program’s Preliminary Feasibility Determination. The Damage Assessment determined whether the home met the Program’s property eligibility requirements, and whether there was visual evidence of Sandy-related damage. It also estimated the costs to repair all storm damage in total, while addressing life, health, safety, and accessibility issues.

Preliminary Feasibility Determination

Following the Damage Assessment, HRO determined the types of benefits an applicant was eligible to receive as part of its Preliminary Feasibility Determination review process. In accordance with HUD requirements and the NYC Building Code, before construction began, HRO was required to perform Substantial Damage (SD) and Substantial Improvement (SI) calculations as part of its Feasibility Determination for each structure receiving assistance in the Special Flood Hazard Area to determine if elevation was necessary.

Pathway Confirmation

During the final design and scope of work process—and prior to starting construction—the home developers conducted a more detailed inspection of an applicant’s home and confirmed the home’s final pathway. Next, the developer met with the applicant to review and finalize construction cost and scope, including design plans. Finally, HRO scheduled a Design Consultation meeting to review the plans with the applicant and sign the grant agreement.

Grant Agreements

All applicants were required to execute a Grant Agreement before receiving assistance from the Program. The Grant Agreement defined the applicant’s responsibilities and obligations in relation to the disbursed funds, as well as the Program’s obligations to the applicant. The Program was required to execute a Construction Grant Agreement, a Reimbursement Grant Agreement, or both, depending on the applicant’s pathway and the agency designated to deliver assistance.

Contractor Options and Agreement Types

Applicants were given the choice to use either a City-managed “Job Order Contractor” (JOC) or a “Chose Your Own Contractor” (CYOC).[6] If applicants chose a City-managed option, the City designated the most appropriate contractor. Applicants that chose their own contractors were given additional flexibility in terms of design and construction, but CYOC projects were still subject to the City’s construction oversight.

According to HRO’s Policies and Procedures, each home rehabilitation project was subject to a construction contract or agreement. If the applicant chose to use a City contractor (JOC), the contractor and property owner were required to execute the BIB Program’s Tri-Party Agreement (TPA), which specified the responsibilities of the Program, the contractor, and the applicant, and established performance measures to ensure timely construction.[7]

If the applicant opted to use the CYOC option, the selected contractor and each property owner were required to execute the Program’s Home Improvement Contract, which describes the responsibilities of the construction contractor and applicant before and during the construction period.[8]

All applicants that received assistance from the Program and whose properties were in a Special Flood Hazard Area were required to obtain and maintain flood insurance.

Applicant Data

As detailed in Table 1 below, 22,436 unique homeowners applied for the BIB Single-Family Program. Of those 22,436 initial applicants, 8,131 were eventually served by the Program; 1,195 were found ineligible; 11,140 either voluntarily withdrew their applications or were withdrawn by HRO; and 1,970 had some other application status, which included “undetermined-in progress,” “construction pre-design,” “renter,” “program review-on hold,” and other categories. Eligible applicants are considered “served” by the BIB Program if they received HUD CDBG-DR benefits.

Table 1: Number of Applicants by Status

| Applicant Status | Number of Applicants |

|---|---|

| Eligible and Served | 8,131 |

| Ineligible | 1,195 |

| Withdrawal | 11,140 |

| Other | 1,970 |

| Total | 22,436 |

Applicants were considered “withdrawn” from the Program if they voluntarily withdrew their applications or were withdrawn administratively by HRO because applicants were either unresponsive or failed to meet Program deadlines.[9]

As detailed in Table 2 below, of the 8,131 applicants served: 537 had their homes repaired; 847 had their homes repaired and elevated; 482 had their homes rebuilt; and 3,585 had their homes repaired by the Program and/or were reimbursed for repairs they had conducted on their own. Additionally, 2,428 applicants were only reimbursed for previous repairs and 252 received relocations and buyouts.

Table 2: Number of Applicants by Assistance Pathway

| Pathway | Number of Served Applicants |

|---|---|

| Repair | 537 |

| Repair with Elevation | 847 |

| Rebuild | 482 |

| Repair with reimbursement | 3,585 |

| Reimbursement only | 2,428 |

| Relocation and Buyouts | 252 |

| Total | 8,131 |

BIB Program Recordkeeping and Tracking

Applicants’ registration data was collected and processed through 311 and transferred into HRO’s Case Management System (CMS), which became operational in June 2013. CMS was developed specifically for the BIB Program using Microsoft Dynamics (a cloud, web-based customer relationship management software program), as the recordkeeping system for the Program’s case management and eligibility review. The information captured in CMS was supplemented by additional datasets available through the NYC Department of Buildings (DOB), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and the NYC Department of Finance (DOF) to help complete and verify applications.

In addition to CMS, HRO used a Document Management System (DMS), which was added in January 2018. This system served as a repository for all draft and final documents used by the BIB Program, which were generated both within and outside of CMS.

Objectives

The objectives of this audit were to determine whether the Build It Back Program achieved its goals of assisting property owners who were affected by Hurricane Sandy to repair and rebuild their homes or relocate, and whether it made Sandy-affected New Yorkers and communities safer and more resilient.

Discussion of Audit Results with HRO

The matters covered in this report were discussed with HRO officials during and at the conclusion of this audit. An Exit Conference Summary was sent to HRO on July 11, 2025, and discussed with HRO officials at an exit conference held on July 25, 2025. On August 8, 2025, we submitted a Draft Report to HRO with a request for written comments. We received a written response from HRO on September 18, 2025.

In its response, HRO acknowledged that Build It Back encountered significant implementation challenges and agreed with the two recommendations made by this audit. By implementing the audit recommendations, HRO stated that the agency was establishing a new standard for compliance and audit readiness that could be applied to future disaster recovery programs.

HRO’s written response has been fully considered and, where relevant, changes and comments have been added to the report. The full text of HRO’s response is included as an addendum to this report.

Detailed Findings

The audit found several significant issues with the BIB Program. HRO served 36% of those applicants who initially applied to participate in the program, despite excluding only a small percentage based on eligibility. Additionally, HRO took protracted periods of time to process applications and begin construction and did not meet its stated goal of completing construction by the end of 2016.

HRO took two years on average to process a single application and six more months to initiate construction. The Program also experienced a very high attrition rate with 11,140 homeowners withdrawing from the program. Based on available data, at least 1,726 homeowners who applied to the Program later voluntarily withdrew their applications for several reasons, including disagreement with Program options offered by HRO, or because the Program processes were reportedly too long. In addition, at least 403 homeowners had their applications “withdrawn” by HRO because they failed to respond to Program requests or missed Program deadlines, among other reasons. For the remaining 9,011 homeowners, HRO did not track a withdrawal type and/or reason, making it impossible to determine why they did not remain in the Program.

HRO established a construction completion deadline of 2016, but nearly 1,600 (40.1%) homes were not completed by this time. In fact, 565 homes—14%—had not even begun construction by then. For homes that began after the deadline, the earliest construction completion was January 2017 and the latest was February 2023—over 10 years after Hurricane Sandy.

On average, construction projects took three years to complete from the date an application was submitted to the date construction finished. Homeowners were relocated for almost two years on average, with 15 homeowners displaced for over four years. HRO did not have timeframe and deadline policies in place at the start of the Program, which likely contributed to Program delays and uncertainty for homeowners.

A 2019 City University of New York report (Patterns of Attrition and Retention on the Build it Back Program) included results from a survey conducted by the Center for Urban Research that collected data from homeowners who engaged with the Program.[10] The results point to areas of significant dissatisfaction by homeowners that are consistent with, and likely the consequences of, the protracted delays in the application processes and in construction identified by the auditors.

40% of BIB Homes Not Completed on Time Due to Program Inefficiencies

As stated previously, the BIB Program was scheduled to be completed by the end of 2016. In 2013 and 2014, HRO received 22,323 single-family applications. As detailed in Table 3 below, by the end of 2014, HRO had completed 334 construction projects. In 2015, HRO completed a further 1,086 construction projects, bringing the total to 1,420 out of 3,990.

Table 3: Number of Single-family Construction Projects Started, Ongoing, and Completed by Year

| Year | Started | Ongoing | Completed | Total Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 745 | 411 | 334 | 334 |

| 2015 | 1,010 | 335 | 1,086 | 1,420 |

| 2016 | 1,670 | 1,033 | 972 | 2,392 |

| 2017 | 502 | 564 | 971 | 3,363 |

| 2018 | 57 | 181 | 440 | 3,803 |

| 2019 | 3 | 45 | 139 | 3,942 |

| 2020 | 0 | 3 | 42 | 3,984 |

| 2021 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3,987 |

| 2022 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3,989 |

| 2023 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3,990 |

Starting in February 2016, HRO implemented new Program timeframes and deadline policies in an attempt to meet the 2016 deadline and to minimize delays related to application processing and pre-construction. These policies included new timeframes related to scheduling and design meetings, grant agreement signings, and homeowner move-out dates.

In September 2016, HRO also developed the Accelerate Build It Back initiative, which allowed City agencies to expedite projects through the City’s pre-construction approval processes. The main purpose of the initiative was to accelerate the development process through a series of waivers and variances to ensure that homes were built correctly and expeditiously.[11] As detailed previously in Table 2, there were 8,131 single-family applications served by the Program. Of those applications, 5,451 received construction benefits, such as repairs, repairs with elevation, or rebuilding. The auditors attempted to assess timeliness for all 5,451 applications, but the auditors were unable to analyze construction timeframes for 1,461 projects because there was no data available in CMS.

Based on the available data for the remaining 3,990 applications served, the average length of time from when homeowners submitted their applications to completion of construction was 1,140 days (approximately three years). This timeframe ranged from a minimum of 241 days to a maximum of 3,513 days (almost a decade).[12]

After HRO implemented deadlines and acceleration initiatives, which began in February 2016, the time to initiate construction decreased from an average of 217 days to 104 days. However, the number of days to complete construction projects increased from an average of 164 days to 283 days. As a result, the average time to initiate construction and complete construction increased by six days; in addition to not ensuring completion by 2016, as planned, the introduction of new policies and initiatives also failed to reduce overall completion times.

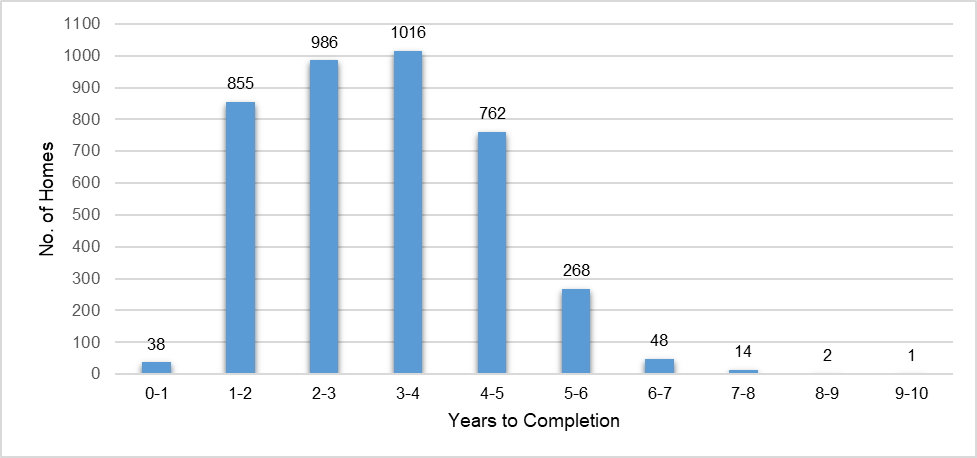

As detailed in Chart 1 below, most of the homes were completed in less than five years; 855 homes took one to two years to complete; 986 took two to three years; 1,016 took three to four years; and 762 took four to five years. For homes that took longer than five years to complete, 268 homes took five to six years, 64 took longer than six years, and one home took almost ten years to complete.

Chart 1: Single-family Home Completion Timeframes

In its response, HRO acknowledged that the Program did not meet the 2016 deadline and stated that delays were caused by a variety of factors, many of which were out of the City’s control, such as federal and local regulations. HRO officials stated that the City had to amend zoning regulations to allow for increased building height, design flexibility, and exemptions to support flood-resilient construction. In addition, HRO cited technical challenges such as elevation of attached homes or homes in dense neighborhoods and lead and asbestos remediation and also stated that construction was delayed due to the limited availability of qualified residential contractors.

HRO officials stated that the Accelerate Build It Back initiative, along with new deadline policies, cut the average time to initiate construction from 217 days to 104 days, as was determined by this audit. However, as stated above, the initiative was not implemented until September 2016 and failed to reduce overall completion times.

HRO’s Controls Over Application and Construction Times Were Inadequate

On average, it took HRO nearly two years (727 days) to process an application, 188 days to initiate construction, and 227 days to complete construction once it began, as detailed in Table 4 below.

Table 4: Application Processing and Construction Timeliness

| Stage | Min Days to Complete | Max Days to Complete | Average Days to Complete |

|---|---|---|---|

| Application Review and Grant Agreement Signing[13] | 41 | 2,182 | 727 |

| Construction Initiation | 1 | 2,467 | 188 |

| Construction Completion | 1 | 1,705 | 227 |

HRO could have monitored construction timelines better. As previously mentioned, contractors were required to sign a Tri-Party Agreement (TPA) or a Home Improvement Contract, both of which included the job order completion time for each project. However, HRO did not ensure that TPA and Home Improvement Contract terms were consistently and accurately tracked in CMS. More rigorous recordkeeping would have allowed HRO to systematically monitor and address delays.

Further, HRO’s policies did not delineate how the agency could track, monitor, or enforce construction timeframes. Established Program-level construction deadline practices should have, at a minimum, prescribed timeliness standards for rehabilitation and reconstruction projects. HRO’s policies also did not outline construction timeline extension terms for Construction Managers who oversaw general contractors.

HRO should have had timeframe and deadline policies in place by the start of Program. While each construction project was unique and faced its own set of challenges, the lack of such policies likely contributed to Program delays, as well as uncertainty—and, in some cases, undue or extended burdens—for homeowners.

The lengthy application processing times may have been partially caused by the number of meetings and phone calls conducted by Program officials, as well as the prolonged timeframes to complete property damage assessments. According to the 2019 CUNY study, homeowners disagreed or strongly disagreed that the number of meetings and phone calls required to complete forms and collect initial documents (57%), finalize scope and design (56%), and discuss construction (57%) was reasonable. Additionally, 59% of served homeowners disagreed or strongly disagreed that the length of time to complete the property damage assessment was reasonable.

Timelines Caused High Attrition and Long Periods of Homeowner Displacement

The lack of adequate controls over timelines for application and construction processes resulted in high attrition rates and long periods of homeowner displacement. Of the 11,140 withdrawn applications, records indicate that at least 1,726 single-family applicants voluntarily withdrew from the Program.

The lengthy application processing times may have caused the high Program attrition rate. According to the 2019 CUNY study, 47% of surveyed Program participants who eventually left the Program felt that processing times were too long. The survey also found that 43% felt that quicker processing and delivery of Program benefits would have persuaded them to remain in the Program.

Some projects involved the displacement of homeowners and occupants due to construction activities, such as elevation, reconstruction, and abatement of hazardous materials. These homeowners and occupants were entitled to Temporary Relocation Assistance (TRA). TRA benefits—which included reimbursement for rental expenses incurred for replacement housing, utility expenses, and moving expenses—were generally limited to 14 months following execution of the Grant Agreement.

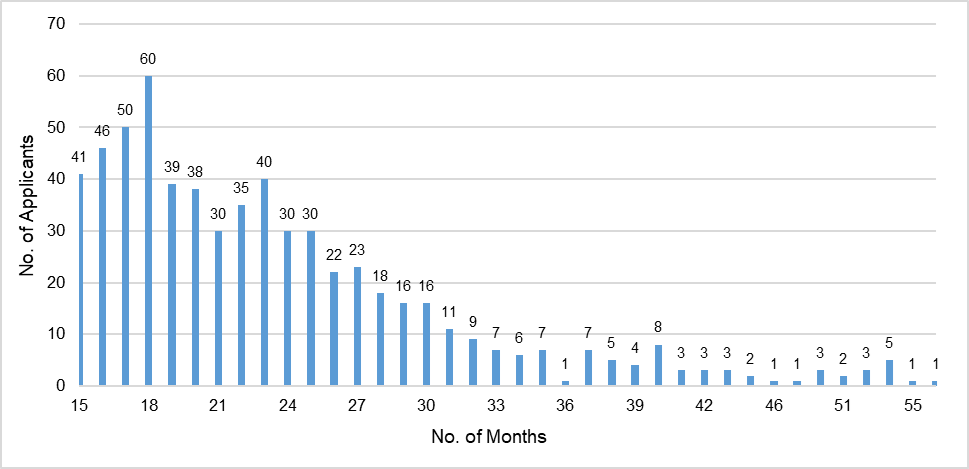

Of the 860 applicants who were temporarily relocated, 627 were displaced from their homes for longer than 14 months. On average, these applicants were temporarily relocated for 24 months. As shown in Chart 2 below, 409 homeowners were relocated for 15 to 24 months, 166 homeowners were relocated for 25 to 36 months, 37 homeowners were relocated for 37 to 47 months, and 15 homeowners were relocated for 49 to 56 months. In all instances, TRA was extended beyond the 14-month period.

These temporary relocations also led to dissatisfaction with the program. According to the 2019 CUNY study, served applicants were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with resources and support offered by the program to help with relocation (56%). Applicants found it difficult or very difficult to relocate themselves and their family or roommates (73%), or tenants (72%), in order for construction to start.

Chart 2: Homeowners Relocated for Longer than 14 Months

In its response, HRO stated that while attrition was high, the CUNY study showed that many withdrawals were based on personal choice or evolving household circumstances and not solely programmatic failure. However, as detailed above, nearly half of the applicants who left the program felt that processing times were too long and 43% said quicker processing would have persuaded them to remain in the program. The CUNY study also showed that applicants who left the program were dissatisfied with how HRO accounted for the funds they received from other sources and applicants’ expenses.

HRO acknowledged that the Program did not fully anticipate the extended duration of displacement of homeowners, particularly during the early program stages. According to HRO officials, relocation periods were long due to the complexity of elevation and reconstruction projects, regulatory delays, and site-specific challenges. HRO stated that it later introduced process improvements to shorten project durations. However, as previously stated, after HRO implemented deadlines and acceleration initiatives, the number of days to complete construction projects increased from an average of 164 days to 283 days.

Center for Urban Research’s Survey Results Point to Homeowner Dissatisfaction in Many Aspects of the Program

As noted above, the 2019 survey conducted by CUNY’s Center for Urban Research evaluated the satisfaction of BIB Program participants. The survey found that applicants voluntarily withdrew from the Program for several reasons, including long processing times (48%), dissatisfaction with Program options (38%), and difficulty completing paperwork and providing documents (34%).

The survey also found those served by the program were very dissatisfied or dissatisfied at very high rates across many aspects of the program, including: acquisition or buyout benefits (69%), construction benefits (57%), and reimbursement benefits offered (54%); and the scope of work (55%), designs (54%), and other design options offered by the program, such as finishes, countertops, and cabinets (61%). Additionally, served applicants strongly disagreed or disagreed with the damage assessment accuracy (54%) and duration (59%). It seems likely that some of the dissatisfaction reported by CUNY relates to the protracted application and construction processes identified during the audit.

Recommendations

To address the abovementioned findings, the auditors propose that HRO should implement the following recommendations for future disaster recovery programs:

- Document timeframes and deadlines in policies and procedures at the beginning of a program for program staff and/or case management contractors to monitor application processing, and for contractor managers to monitor construction activities, to ensure their timely progression and completions.

HRO Response: HRO agreed with this recommendation.

- Establish and track performance indicators in the recordkeeping system, including timeliness for contractors responsible for application processing and construction management.

HRO Response: HRO agreed with this recommendation.

Recommendations Follow-up

Follow-up will be conducted periodically to determine the implementation status of each recommendation contained in this report. Agency reported status updates are included in the Audit Recommendations Tracker available here: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/services/for-the-public/audit/audit-recommendations-tracker/

Scope and Methodology

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (GAGAS). GAGAS requires that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions within the context of our audit objective(s). This audit was conducted in accordance with the audit responsibilities of the City Comptroller as set forth in Chapter 5, §93, of the New York City Charter.

The scope of this audit was from June 2013 to June 2025.

To obtain an understanding of various BIB Program administrative procedures utilized to implement the Program, the auditors reviewed multiple versions of the New York City Build It Back Single-Family Policy Manual,[14] Grant Agreement Generation and Scheduling Standard Operating Procedure (SOP),[15] HRO Reimbursement Review: Process and Procedures, Record Keeping and Document Management SOP,[16] TRA Review SOP,[17] NYC BIB HRO Compliance SOP: 1-4 Unit Homes revised in December 2016, Design Guidance: Substantial Damage and Substantial Improvement, Rebuild Program: City-Selected Developer Program Procedures, Rebuild Program: Choose Your Own Contractor Program Procedures, NYC Build-It-Back Rebuild Program Terms, DDC Office of the Engineering Audit SOP for BIB Program, and NYC BIB HRO Contract Audit SOP: 1-4 Unit Homes. Further the audit team reviewed HRO BIB Program training materials and job aids. In addition, the auditors reviewed HUD’s annual monitoring reports.

The auditors interviewed relevant agency officials from HRO’s Budget & Compliance team to gain an understanding of the Build It Back application process and HRO’s progress in closing out the applications.

The auditors conducted walkthroughs with HRO’s IT team to gain an understanding of its computerized systems, CMS and DMS, which contain application-relevant information and supporting documentation. The auditors obtained data sets related to applications and eligibility, generated by HRO on December 21, 2023, from CMS. In addition, the auditors obtained read-only access to CMS and DMS.

To assess the completeness of HRO’s list of served applications, the auditors independently generated a list of application data from CMS and reviewed fields such as construction completion, key turnover, warranty dates, or reimbursement amounts, which would indicate that an applicant was served. The auditors compared the list to HRO’s served list and requested clarification on the discrepancies.

To determine if HRO reimbursed, repaired, repaired and elevated, or rebuilt homes on a timely basis, the auditors calculated the amount of calendar days it took HRO to review an application and sign a grant agreement, initiate construction, and complete construction based on application processing and construction dates obtained from CMS, DMS, and the New Closeout system.

To determine whether HRO deadlines and acceleration initiatives, which began in February 2016, improved construction timelines, the auditors calculated and compared the number of calendar days it took to initiate construction and complete construction before and after the initiatives began.

To determine the length of time homeowners were displaced, the auditors obtained Temporary Relocation Assistance start and end dates from CMS and calculated the length of time between the two dates. Additionally, the auditors analyzed the applicants that were displaced for longer than 14 months, the program’s general limit, by calculating the maximum, minimum, and average time spent displaced.

The auditors reviewed the 2019 Patterns of Attrition and Retention in the Build It Back Program study conducted by the Center for Urban Research (CUR) at CUNY Graduate Center. As part of the study, CUR independently developed and conducted an online survey of BIB using participants’ email addresses obtained from HRO. CUR sent out over 14,300 surveys and received 1,387 responses, resulting in a response rate of approximately 10%. Survey data was collected by CUR on a confidential basis and only CUR had access to the data. When evaluating the survey results, the auditors considered the response rate, survey independence, and survey design and administration. The auditors attempted to obtain the survey data from CUNY. However, CUNY stated that it was unable to release the survey data due to agreed-upon confidentiality with the survey respondents.

The results of the above tests provided a reasonable basis for the auditors to evaluate whether HRO properly assisted homeowners impacted by Hurricane Sandy and whether it made Sandy-affected New Yorkers and communities safer and more resilient.

Appendix I

Flowchart of BIB Processes Specific to Single-Family Homes

Appendix II

Flowchart of Application Process Specific to Single-Family Homes

Addendum

Endnotes

[1] Beginning in 2015, applicants whose homes were not eligible for repair or reconstruction were offered State or City acquisition/buyout options.

[2] According to the New York City Building Code, “grade” is the level of the curb as established by the City engineer in the Borough President’s office, measured at the center of the front of a building, or the average of the levels of the curbs at the center of each front if a building faces more than one street.

[3] EDC activated an existing contractor to assist HRO with setting up the program and engaged design firms to conduct damage assessments, scoping, and hazards testing.

[4] HRA procured a broad case management contract with a vendor that provided eligibility review and counseling services.

[5] The BIB Program did not have sufficient funding to reimburse all applicants at 100% of their eligible reimbursement amounts. The Program’s standard reimbursement amount was 60% of an applicant’s total eligible reimbursement amount.

[6] All construction under the BIB Program was initially managed by the City. The Program was modified over time to include homeowner-managed construction and direct reimbursement for work done by homeowners in 2014. Direct grants became available in October 2015.

[7] Construction on a property was required to begin within 15 days of the applicant signing the TPA. The Grant Agreement signing was scheduled within eight days of the applicant signing the TPA.

[8] The contractor was required to begin construction work on the date specified in the Notice to Commence issued by the Program and complete the work within the time period specified in the Home Improvement Contract.

[9] Applicants’ unresponsiveness or failure to meet Program deadlines included failure to sign a grant agreement within 14 days from the date of design consultation date; failure to meet targeted deadlines; failure to meet move-out date; failure to accept approved pathway within 14 days of a notification, etc. Applicants voluntarily withdrew from the Program because they may have disagreed with the accuracy of the home damage assessment or the Program options presented to them, had difficulty with administrative paperwork, and/or felt that Program processing times were too long.

[10] CUNY, Patterns of Attrition and Retention on the Build it Back Program

[11] For example, the Program would sign certain construction forms on behalf of the homeowner to expedite the processing of the forms and their approvals. In addition, the Program would defer certain Department of Buildings requirements to sign off on homes that met specific guidelines.

[12] The auditors used the best available data related to construction work such as warranty start dates, key turn over dates, construction start and end dates, construction substantial completion and completion dates, or construction scheduled start and end dates.

[13] HRO required the Grant Agreement to be signed and notarized three days prior to construction. If the agreement was not received, the construction timeline would be altered. The receipt of the Grant Agreement was recorded in CMS, which triggered a notification in CMS that construction could commence.

[14] There are 10 versions of the manual available. The document was revised by HRO eight times between March 2014 and December 2021.

[15] There are 11 versions of the SOP available. The document was revised by HRO nine times between February 2014 and October 2015.

[16] There are 11 versions of the SOP available. The document was revised by HRO 10 times between March 2016 and November 2016.

[17] There are 16 versions of the SOP available. The document was revised by HRO 15 times between March 2015 and June 2016.