Audit Report on the New York City Department of Transportation’s Speed Camera Program

To the Residents of the City of New York:

My office has audited the New York City Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Speed Camera Program (Program). The objectives of the audit were to determine: (1) whether DOT monitors and has adequate controls over the Program; (2) whether DOT accurately issued Notices of Liability (NOL) for violations detected by the speed cameras; and (3) whether speed cameras are functioning and maintained properly. We conduct audits such as this to identify areas where improvements could be made to strengthen the programmatic and fiscal effectiveness of City programs.

The audit found that DOT’s designation of speed zone locations and placement of cameras was compliant with Section 1180-b of the New York State Vehicle and Traffic Law, and that DOT generally monitored the speed camera program well. The audit also found that the number of speeding violations has been reduced over time and that traffic accidents in the vicinity of speeding cameras have also come down, despite overall trends showing increased numbers of accidents due to unsafe speeding.

However, the audit found several problems with the Program and identified areas where DOT’s oversight could be improved. In particular, DOT’s monitoring over rejected speeding events requires improvement. Despite a disproportionate growth and significant year over year increase in rejections based on missing/temporary or obscured license plates, there is no evidence that DOT has taken steps to combat this worsening problem. The auditors estimate that in CY2023 rejections in this category represent an estimated $108 million in foregone revenue and many opportunities to curtail dangerous speeding. This is revenue that New York City could use to expand the speed camera program in future.

The audit makes eight recommendations including that DOT should modify the existing contract and all future contracts to ensure DOT has full access to data related to rejected speeding events; regularly review and analyze rejection data to identify underperforming and inactive cameras and address them as they occur; and work with law enforcement, State agencies, and other cities experiencing problems with missing, temporary, and obscured license plates to identify potential solutions to this growing problem. DOT has accepted all eight of the recommendations, indicating a commendable willingness to make changes for the benefit of New York City.

The results of the audit have been discussed with DOT officials and their comments have been considered in the preparation of this report. DOT’s complete written response is attached to this report.

If you have any questions concerning this report, please email my Audit Bureau at audit@comptroller.nyc.gov.

Sincerely,

Brad Lander

New York City Comptroller

Audit Impact

Summary of Findings

The audit of the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) speed camera program identified several positives. DOT’s oversight over the vendor was generally adequate, the placement of cameras—contrary to understandable concerns expressed by certain stakeholders—was found to be consistent with the requirements of the New York State Vehicle and Traffic Law (VAT), and data reviewed by the auditors suggests positive outcomes from the placement of speed cameras.

The average daily number of notices of liability (NOL) for each fixed speeding camera site decreased from 123 NOLs in Calendar Year 2014 to fewer than 10 in 2022, indicating that cameras may have helped to change driving behavior and reduce speeding. In addition, even though the motor vehicle collision data indicates that the number of accidents with casualties or injuries due to unsafe speed or aggressive driving was trending upward from Calendar Year 2019 to 2023, only 8 of the 45 sampled crashes occurred in locations near a speed camera, suggesting that cameras reduce accidents within the vicinity.

While DOT did many things well, and the cameras appear to assist NYC in increasing traffic safety, the audit found several problems with the Program and identified areas where DOT’s oversight could be improved. DOT does not have full access to rejected speeding event data in the AXSIS system, which is used to archive images and video of speeding events.[1] While DOT does conduct second level reviews before NOLs are issued, it does not review or monitor events rejected by Verra, the contractor responsible for installing and maintaining the cameras. Therefore, DOT does not know whether Verra appropriately rejects speeding events, cannot verify that cameras are appropriately located or positioned, and is unable to identify potential problems that reduce the effectiveness of the Program. A review of Verra’s rejections found errors in 11.7% of the sample. This equates to a potential estimated loss of $865,500 over the sampled period, which only covered six weeks.

The audit also found disproportionate growth and significant year over year increases in rejections based on missing/temporary or obscured license plates, but no evidence that DOT has taken the necessary steps to combat this worsening problem. The current losses associated with rejections in these two categories represented up to $54 million in lost revenue from January to June 2023. While data for the remainder of 2023 was not available to review, the data for the first half of the year is trending upward. Based on the data provided for the first half of the year, a conservative estimate for the full calendar year is $108 million in foregone revenue.

Also, DOT only used an average of 62.5% of its 40 mobile zone vehicles during the last quarter of 2021 and an average of 47.5% during the months of March 2022, June 2022, September 2022, December 2022, March 2023, and June 2023. This is an inefficient use of agency resources, since the City pays close to $4,000 a month to maintain each mobile camera. Over the three-month period in 2021 that the auditors reviewed, the highest deployment rate in one day was 75% (30 vehicles). The corresponding figure for the four sampled months in 2022 and two sampled months in 2023 was 72.5% (29 vehicles).

Finally, since Verra did not provide a listing of cameras for the services being billed, DOT was unable to ensure the contractor’s invoices were accurate. The auditors determined that DOT overpaid Verra $107,483 for cameras that were relocated, inactive, or offline.

Intended Benefits

The audit identified areas where improvements could be made to strengthen the programmatic and fiscal effectiveness of the Speed Camera Program.

Introduction

Background

In 2013, New York State authorized the City of New York to pilot an automated speed enforcement program (also known as the Speed Camera Program) to deter speeding in 20 school zones, as set forth in New York State VAT Law Section 1180-b. VAT allows the City to impose up to $50 in fines on the owner of any vehicle traveling at a speed more than 10 miles per hour above the posted speed limit in a school speed zone.

While some City residents believe that speed cameras “disproportionately affect communities of color,” the law regulates the establishment of school speed zones and requires the City to consider criteria including, but not limited to, the speed data, crash history, and the roadway geometry applicable to such school speed zones.[2] The City is also required to prioritize the placement of photo speed violation monitoring systems (speed cameras) in school speed zones based upon speed data and/or the crash history of designated zones. Speed cameras may not be placed on a highway exit ramp or within 300 feet from the end of a highway exit ramp.

In June 2014, the pilot was expanded to 140 school zones to support the City’s Vision Zero goal of eliminating traffic deaths and serious injuries.[3] In 2019, the number of allowable speed zones increased again to 750, with approximately 2,000 cameras installed in total. Of the 750 speed zones, 710 are monitored by fixed units located within a quarter-mile radius of a selected school building; the remaining 40 are movable and subject to the placement of mobile speed cameras, which are mounted on vehicles and can be deployed by DOT as it deems fit. Initially, speed cameras operated on weekdays between 6am and 10pm, but in August 2022, operating hours were extended to 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

DOT contracted with Verra to install and maintain the speed cameras.[4] Payments to Verra are based on the number of active cameras that Verra maintains and the number of cameras that are installed or relocated at DOT’s request. As the prime contractor of the Program, Verra is responsible for:

- installing and removing speed cameras;

- maintaining and repairing speed cameras or replacing non-functioning cameras;

- maintaining the AXSIS system, which archives images and videos of speeding events captured by the cameras and issues NOLs to vehicle owners;

- conducting an initial review of speeding events, eliminating (i.e., rejecting) certain events based on criteria set by DOT, and purging rejected events after the 45-day retention period. Examples of rejected event categories include fire or emergency medical services (EMS) vehicles, captured images of the speeding vehicles or the vehicles’ license plates that are unclear or obstructed, and vehicles with missing or temporary license plates; and

- providing DOT with access to footage for the remaining speeding events for the agency’s second review.[5]

DOT’s technicians review the remaining speeding events and, if necessary, reject additional events. DOT then prints the NOLs via AXSIS and mails them to vehicle owners.[6] The New York City Department of Finance (DOF) is responsible for collecting the fines assessed. In 2021, the City issued 4.4 million NOLs and collected $243.9 million in fines.[7] In 2022, the City issued 5.7 million NOLs and collected $255 million.

Objectives

The objectives of the audit were to determine: (1) whether DOT monitors and has adequate controls over the Program; (2) whether DOT accurately issues NOLs for violations detected by the speed cameras; and (3) whether speed cameras are functioning and maintained properly.

Discussion of Audit Results with DOT

The matters covered in this report were discussed with DOT officials during and at the conclusion of this audit. An Exit Conference Summary was sent to DOT and discussed with DOT officials at an exit conference held on November 6, 2023. On November 16, 2023, we submitted a Draft Report to DOT with a request for written comments. We received a written response from DOT on December 20, 2023. In its response, DOT agreed in part with the findings and agreed with all the recommendations.

DOT’s written response has been fully considered and, where relevant, changes and comments have been added to the report.

The full text of DOT’s response is included as an addendum to this report.

Detailed Findings

Analysis of data maintained in AXSIS suggests that the Program works to reduce speeding and crashes. DOT’s designation of speed zone locations and placement of cameras was assessed by the auditors and found to be compliant with Section 1180-b of the New York State VAT Law. Speed cameras are widely distributed throughout City neighborhoods. The audit also found that DOT generally monitored the speed camera program well and Verra generally complied with the contract terms and conditions.

However, the audit also found many areas for improvement, including DOT’s lack of oversight over rejected speeding incidents captured by speed cameras. The audit found that despite massive increases in the number of drivers circumventing violations with missing, temporary, and obscured plates, DOT has done little to address the problem, potentially costing the City an estimated $108 million in foregone revenue during 2023 and representing many missed opportunities to increase traffic safety.

Data Suggests Speed Cameras Work to Reduce Speeding and Crashes

The auditors reviewed the average daily NOLs for each fixed speeding camera site and found a decrease from 123 NOLs in Calendar Year 2014 to fewer than 10 in 2022, indicating that cameras may have helped to change driving behavior and reduce speeding.

The auditors also reviewed a sample of motor vehicle collision data. Overall, the number of accidents with casualty or injuries due to unsafe speed or aggressive driving has trended upwards between Calendar Years 2019 and 2023, yet only 8 of the 45 sampled crashes occurred in locations near a speed camera. This suggests that speed cameras may be effective in reducing certain crashes, at least in their vicinity.

DOT’s Placement of Cameras Complied with New York State VAT Law Section 1180-b

DOT complied with the NYS VAT Law Section 1180-b requirement when it established the speed zones and determined camera locations. Specifically, DOT combined the crash data provided by the NYPD and GPS speed data collected by Department of Citywide Administration Services’ (DCAS) fleet telematics to create a database of locations. The auditors reviewed the database and compared the data with the speed zones selected and found that the established speed zones were ranked high in the database. The auditors also randomly selected five high ranked streets where DOT chose not to install cameras and considered DOT’s reasoning for not selecting the location, such as a speed bump was installed, or a camera was already installed at a street nearby. After reviewing DOT’s explanations and supporting documentation, the auditors determined that DOT properly placed the cameras in high-risk locations.

DOT Generally Has Adequate Controls in Place and Verra Generally Met Their Obligations Under the Contract

The audit found that DOT generally had adequate controls over the Speed Camera Program. Specifically, DOT has established policies and procedures for processing of violations reviews and issuance of NOLs, reviews accepted violations submitted by Verra and determines whether NOLs should be generated. Additionally, DOT accurately issued NOLs for violations detected by speed cameras and ensured that speed cameras were functioning and properly maintained.

Furthermore, Verra generally met their contractual obligations. Verra installed cameras on new and existing poles throughout the five boroughs per DOT requests and submitted invoices on the monthly basis for the maintenance and installation of speed cameras. Verra also maintained proper insurance coverage and conducted annual calibration inspections on cameras to ensure that cameras functioned properly. Finally, Verra also reviewed all violations that occurred daily and made determinations on which violations would be rejected for various reasons.

Speeding Event Rejections Not Monitored by DOT

The audit found that DOT does not sufficiently monitor speeding events rejected by Verra. While DOT conducts second level reviews of all accepted speeding events before NOLs are issued, DOT does not conduct reviews when Verra decides to reject a speeding event captured by cameras. This is partly due to DOT’s decision not to conduct such reviews, and contractual terms that limit access to information and images that are necessary for DOT to conduct reviews.

The AXSIS system maintains a summary of rejection data by category, but the underlying data is only maintained by Verra for 45 days before it is purged. The contract does not require Verra to provide DOT with access to the underlying data by location, and DOT is unable to access videos or images to determine whether rejected speeding events were properly excluded by Verra. This leaves a crucial determination by Verra without appropriate monitoring or oversight and prevents DOT from assessing whether all cameras or the Program are functioning effectively.

Rejections represent a significant portion of all speeding events detected by speed cameras. There are close to 100 categories under which Verra may reject an event, based on criteria established by DOT. During Calendar Year 2022, Verra rejected 36.6% of all speeding events identified by cameras, and a further 41.5% were rejected during the first six months of Calendar Year 2023. Significant increases in certain rejection categories and errors by Verra in applying DOT’s criteria represent lost opportunities to curb speeding and a potential loss of revenue which could help to offset the cost of the Program. DOT’s inability to identify potential problems for locations with high rejection rates could also reduce the overall effectiveness of the Program.

On March 17, 2023, after this issue was discussed with DOT, agency officials acknowledged that DOT should conduct better oversight of rejected speeding events. The agency stated that it will add the ability to audit rejected events as a requirement in the next contract’s Request for Proposal. Further information concerning related audit findings follows below.

Rejections Related to License Plate Issues May Have Cost the City Over $100 Million in Lost Revenue for Calendar Year 2023

Between January 2019 and June 2023 an analysis of data shows that rejected speeding events increased significantly. This is most likely due to a change in the law as of August 2022, which made cameras operate on a 24-hour basis. The data also shows a corresponding increase in rejections overall, underlining the need to increase monitoring over rejected events.

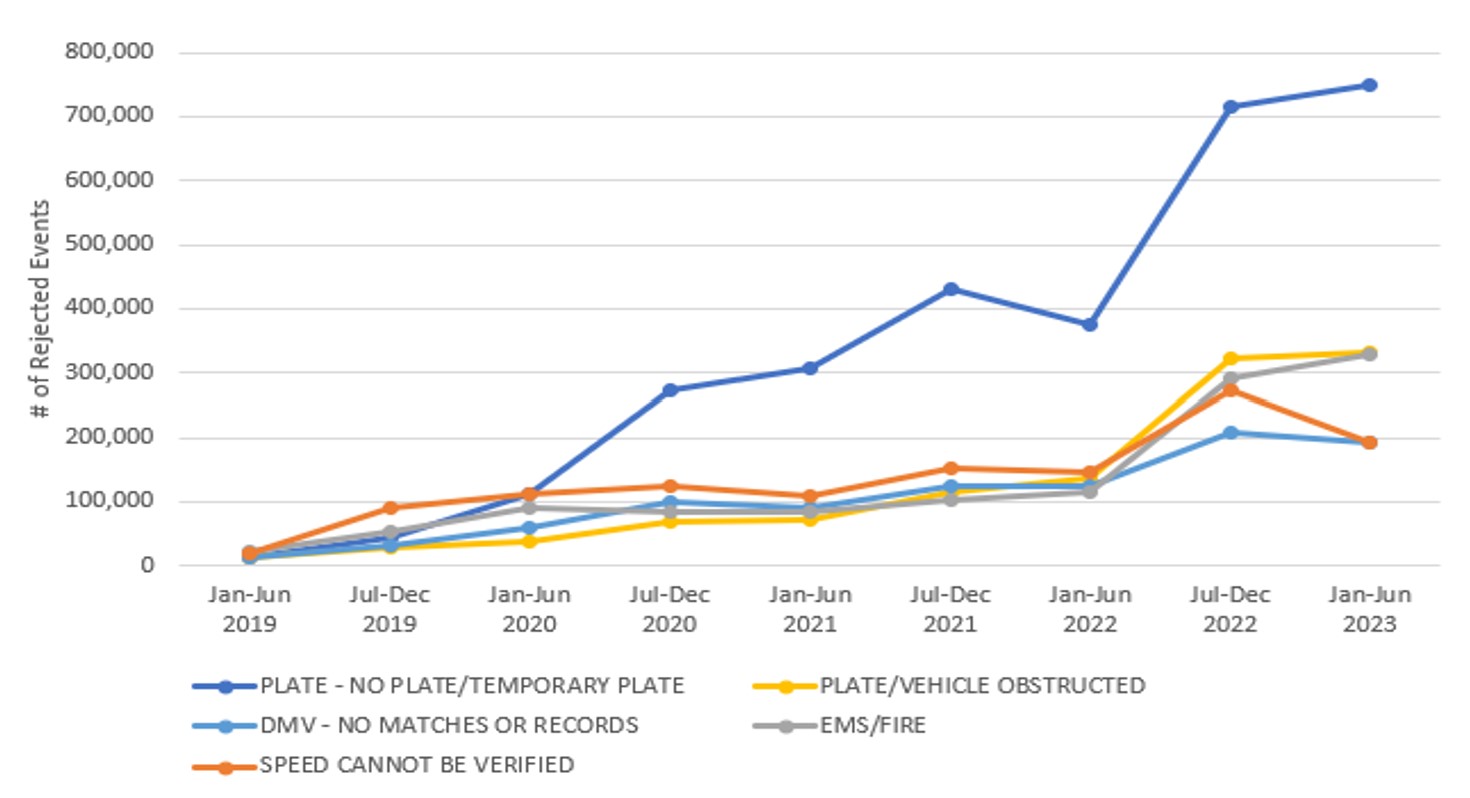

Alarmingly, the data shows a disproportionate increase in rejections based on missing or temporary license plates. Chart I (below) shows the top five rejection categories over this four-and-a-half-year period. Rejections based on missing or temporary license plates far exceeded other rejection reasons, peaking at 748,468 between January and June 2023—226% higher than Plate/Vehicle Obstructions, the next rejection category. Obstructions include when the license plate number, model or make of the vehicle is blocked by other objects when the image is taken. Examples include obstructions by other vehicles or plastic covers that prevent the camera from capturing a clear image of the license plate information. Cases in which drivers deliberately use tape or paint to cover one or more digits of license plates to prevent cameras from reading the number also fall into this category.

Together, the two rejection categories account for more than a million rejected speeding events between January and June 2023. These rejected speeding events mean that speeding motorists are not held accountable for their conduct, anticipated improvements in roadway safety are less effective than they could be, and the City foregoes revenue for lost opportunities to issue NOLs. Based on data provided by DOT, the foregone revenue reached $54 million between January and June 2023. While data for the remainder of 2023 was not available for review, the data is trending upward. Based on the data provided for the first half of the year, a conservative estimate for the full calendar year is $108 million in foregone revenue.

Chart I: Top Five Rejection Categories

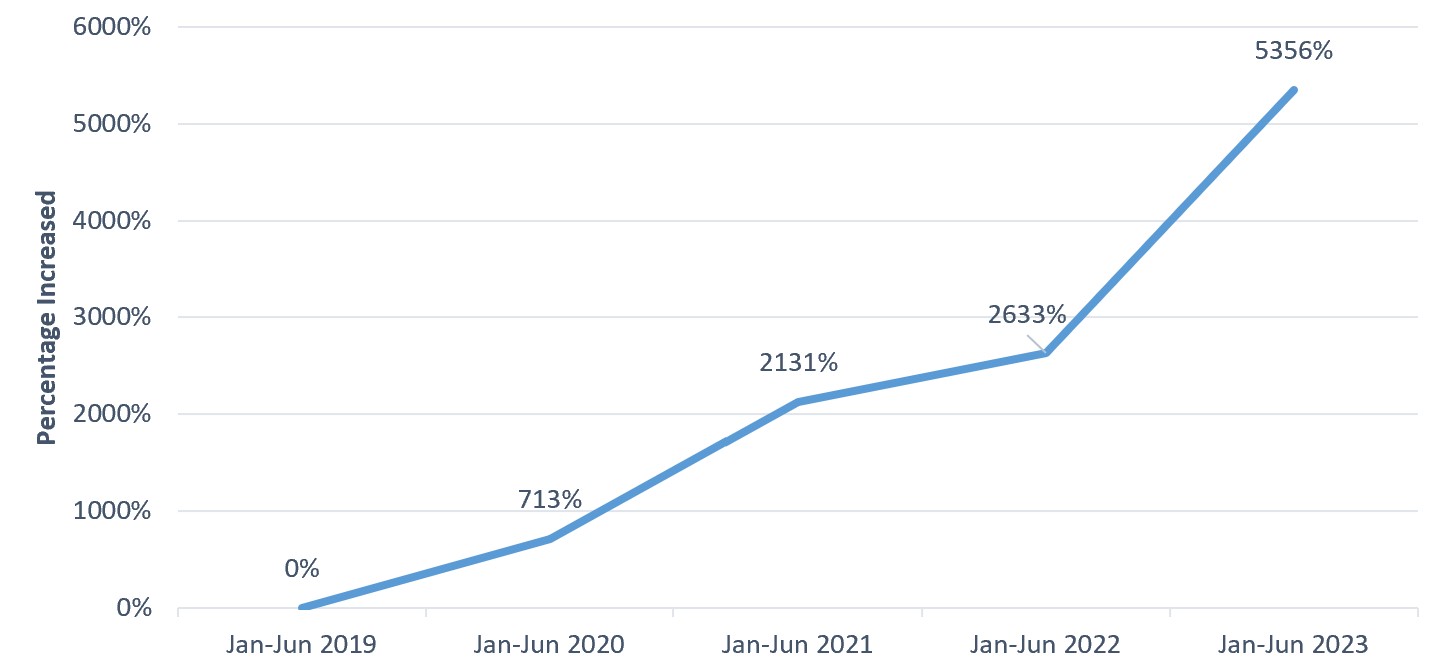

The data also shows a marked increase in the use of this rejection category over time. When compared to the prior four-and-a-half-year period, rejections based on no license plate or temporary license plates increased by 5,356%. See Chart II below:

Chart II: Percentage Increase of No License Plate/Temporary License Plate Rejections

Although DOT cannot reduce the number of vehicles with missing, temporary, or obstructed license plates, it can and should improve its monitoring efforts by analyzing rejection data, identifying problematic locations, and working with other agencies—such as coordinating with NYPD to issue tickets to speeding drivers at high rejection locations where vehicles have missing or temporary license plates, or have their license plates obstructed. DOT should also conduct outreach to other cities and State agencies that experience similar problems with toll evasion (such as the MTA and the NY/NJ Port Authority), to identify potential solutions.

In DOT’s response, DOT stressed that the purpose of the Program is to deter speeding and save lives, noted that revenue generation is only a byproduct of the Program, and stated that it is a mischaracterization to blame the loss of revenue on DOT. While the auditors understand DOT’s position and agree that DOT has not caused the problem, it is also true that DOT had taken no action to address the problem prior to this audit. Rejected speeding events reduce revenue that could fund future expansion of the Program, and the ability of drivers to effectively circumvent speeding cameras undermines the fundamental purpose of the Program by allowing speeding to go unchecked and without consequence.

Incorrect and Undocumented Rejections by Verra

Auditors also found errors in some of Verra’s rejection determinations, and an absence of records needed to substantiate others.

Between November 15 and December 31, 2022, Verra rejected over 400,000 speeding events. Almost all of those—98%—were rejected under 23 of DOT’s 80 rejection categories. Auditors reviewed 195 of the rejected speeding events, all of which belonged to these majority categories, and found that 23 (11.7%) had issues: 12 (6.1%) were rejected inappropriately because Verra incorrectly applied rejection criteria, and 11 (5.6%) could not be substantiated because Verra lacked evidence that would support their conclusions.

The 12 inappropriate rejections fell under five DOT categories, with the majority percentage rejected under two: “EMS/Fire” and “No Vehicle Present.”[8] For EMS/Fire rejections, which constituted the highest percentage of rejections within the five categories, the auditors found one of the 26 selected samples to be erroneous. In that instance, Verra mischaracterized a postal vehicle as an EMS/Fire response vehicle. For rejections categorized as No Vehicle Present, the second-highest percentage of rejections within these categories, Verra mistakenly concluded no vehicle was present in 4 of the 10 samples reviewed. Vehicles were present; however, Verra rejected them if the speeding vehicle was not in the stated lane, or if they could not determine the lane in which the speeding vehicle was traveling. For the remaining seven incorrectly rejected events, one was rejected based on the expired operating hours (i.e., 6am to 10pm); five garbage trucks were rejected using the bus lane rejection criteria; and one was rejected due to a speeding vehicle straddling lanes.

Auditors were unable to determine whether another 11 speeding events rejected under two categories—six under the “Violation Date is Past Enforceable Date” category, and five under the “Stale Date” category—were rejected correctly. For both categories, the rejection hinges on DMV providing information within timeframes established in Section 1180-b of the VAT Law: 14 business days for New York residents and 45 business days for non-residents. Verra stated that information from DMV was not transmitted back to Verra due to technical issues. However, Verra was unable to provide evidence to support its claim that DMV was at fault.

According to DOT officials, the speeding vehicles’ information, such as license plate, model, and make, must be matched with DMV’s records for NOLs to be issued to vehicle owners. If Verra cannot obtain the vehicles’ information within the established timeframes, DOT cannot issue the NOLs to vehicle owners. Verra does not maintain documentation needed to verify DMVs’ untimely responses.

The percentage of incorrect or insufficiently documented rejections (11.7%) was small in the sample but could potentially indicate significant numbers of missed opportunities to issue NOLs, as well as lost revenue, given the very high volume overall. Auditors estimated lost revenue for the six-week period to be around $865,500.

Certain Cameras Had Unusually High Rejection Ratios

The auditors found that, in December 2022, images captured by certain cameras resulted in very high rejection rates when compared to total events captured. For example, one camera located in Brooklyn captured 1,031 speeding events, but 950 of these were rejected. Another camera located in Queens captured a total of 702 speeding events, but DOT was only able to issue 13 NOLs to vehicle owners—this equates to a 98% rejection rate.

Most of the rejections from these two cameras were categorized as “No Vehicle Present.” Verra admitted during the audit that it incorrectly applied DOT’s rejection criteria for this category, which may account for the problem.

During the same period, auditors also found that 67 cameras captured no speeding events at all. DOT stated that 60 of these were offline due to relocation of the cameras, lack of power, testing in progress, and other issues, which explained why these 60 cameras were not capturing any speeding events during December 2022. For the remaining seven cameras, DOT stated it was due to low traffic volume caused by construction or other activities.

High rejection rates and cameras that capture no speeding events are potential issues that DOT should be aware of and promptly address. When raised with DOT, the agency indicated that it generally does not relocate or reposition cameras unless there is an issue due to construction or closing of a school. Their plan is to wait until all 2,220 cameras have been installed and then re-assess overall placement.

DOT should reconsider its policy not to redeploy cameras where specific problems have been identified, such as in the case of the two cameras identified above with very high rejection rates. It would make sense to evaluate the cause of problems with specific cameras as they occur and take remedial action on an ongoing basis.

DOT Did Not Maximize Its Use of Mobile Zone Vehicles

Based on mobile zone vehicle records for the last quarter of Calendar Year 2021, DOT, on average, used just 25 of its 40 vehicles. The highest one-day deployment rate was 75% (30 vehicles), while the lowest was 35% (14 vehicles). According to DOT officials, the agency experienced a staff shortage during the pandemic. However, based on mobile van daily deployment records for the months of March 2022, June 2022, September 2022, December 2022, March 2023, and June 2023, DOT used only 19 of its 40 vehicles on average during these six months. The daily deployment rate ranged from 22.5% (9 of 40 vehicles) to 72.5% (29 of 40 vehicles) on any given day during the period. The City continues to pay maintenance fees close to $4,000 per camera per month, whether they were in use or not. This is wasteful spending; DOT should ensure each camera is deployed or should reduce the number of mobile cameras provided under the contract.

DOT Should Improve Its Billing Review Process

DOT does not ensure that the billing invoices are accurate and, as a result, overpaid Verra for inactive or relocated cameras. Verra charges a monthly maintenance fee of over $4,000 for each active camera; however, the monthly invoices only list the total number of cameras without an itemized list of each active camera. Without this information, DOT cannot determine whether Verra properly billed the City.

The auditors requested and reviewed invoices which included an itemized list of cameras covered by the invoice, for the period of October to December 2021. The auditors determined that Verra overbilled the City as follows:

- Five instances where three cameras were relocated but were still being assessed a total of $20,915 for previous locations;

- Five instances where four cameras were either not activated or offline for the entire month, but were still being charged $21,555 in monthly maintenance fees; and

- 32 newly installed cameras that were charged for prorated maintenance fees, totaling $8,243, but were only activated in subsequent month(s).

The auditors determined that DOT overpaid Verra $50,713 for the period of October through December 2021 (an error rate of 0.12% when compared with total payments made to Verra for installation and maintenance services provided during the last quarter of 2021). DOT also overpaid an additional $56,770 for one camera that was relocated for a 14-month period from August 2020 to September 2021.

DOT should recoup these amounts from Verra since this camera was billed erroneously for both the old and new locations.

Recommendations

To address the abovementioned findings, the auditors propose that DOT should:

- Modify the existing contract and all future contracts to ensure DOT has full access to data related to rejected speeding events, including images and videos.

DOT’s response: DOT agreed with this recommendation.

- Request access to camera footage for all rejected speeding events in the AXSIS system on a regular basis and conduct sample-based reviews to determine whether rejections were appropriate, and if not, reverse the rejections and issue NOLs to vehicle owners.

DOT’s response: DOT agreed with this recommendation.

- Provide Verra and its subcontractor with additional guidance and training on DOT’s rejection criteria.

DOT’s response: DOT agreed with this recommendation.

- Regularly review and analyze rejection data to identify underperforming and inactive cameras and address them as they occur.

DOT’s response: DOT agreed with this recommendation.

- Work with law enforcement, State agencies, and other cities experiencing problems with missing, temporary, and obscured license plates (impacting speeding, red light, and bus lane cameras, and tolls) to identify potential solutions to this growing problem.

DOT’s response: DOT agreed with this recommendation.

- Determine whether it is cost effective to maintain all 40 mobile speed camera vehicles.

DOT’s response: DOT agreed with this recommendation.

- Obtain a list of cameras being billed by Verra and carefully reconcile these to the active camera list before approving payment.

DOT’s response: DOT agreed with this recommendation.

- Recoup $107,483 from Verra in overcharged maintenance fees and determine whether any additional amounts should be recouped if Verra overcharged the same relocated camera beyond December 2021.

DOT’s response: DOT agreed with this recommendation.

Recommendations Follow-up

Follow-up will be conducted periodically to determine the implementation status of each recommendation contained in this report. Agency reported status updates are included in the Audit Recommendations Tracker available here: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/services/for-the-public/audit/audit-recommendations-tracker/

Scope and Methodology

We conducted this performance audit in accordance with Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (GAGAS). GAGAS requires that we plan and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions within the context of our audit objectives. This audit was conducted in accordance with the audit responsibilities of the City Comptroller as set forth in Chapter 5, §93, of the New York City Charter.

The scope of this audit was January 2019 to June 2023.

To achieve the audit objectives, the auditors reviewed New York State Vehicle and Traffic Law 1180-b, interviewed DOT officials, and reviewed DOT documentation to obtain an understanding of the Program, including the methodology used to establish the speed zones and determine locations of cameras, the criteria and rationale used to reject the footage captured by the cameras, the process of issuing NOLs via the AXSIS system, and the oversight process of Verra’s performance and billings. To determine Verra’s responsibilities, the auditors reviewed the contract between DOT and Verra and interviewed Verra’s staff to obtain an understanding of Verra’s operation, including installing and removing speed cameras, pre-screening of the footage captured by the speed cameras, data retention policy, and billing process.

To determine whether the speed camera zone placements were based on DOT’s established criteria, the auditors reviewed the site placement ranking methodology that included GPS speed data collected from DCAS’ fleet telematics and crash data that includes the number of people killed or seriously injured. The auditors then compared the placement ranking data with the speed zone locations to determine whether the zones were established appropriately. The auditors also randomly selected five locations that ranked high but were not selected for placement of a camera and obtained an explanation from DOT as to why these locations were not selected. To determine the effectiveness of the Program, the auditors analyzed the crash data and determined the number of crashes that occurred during January 2019 to June 2023 caused by unsafe speed or aggressive driving. The auditors then randomly selected five crash samples for every six-month period and determined whether the crash locations had any speed cameras nearby.

The auditors also analyzed the location of the speed cameras and the number of NOLs issued for October, November, and December 2021 (months with the highest payments) to identify speed cameras that might not be installed in ideal locations or functioning properly due to a low number of issued NOLs. In addition, the auditors randomly selected 100 speed cameras to determine whether the cameras were installed at the stated locations.

To determine whether DOT utilized all 40 vehicles equipped with speed cameras (mobile speed zones), the auditors analyzed the Daily Deployment Reports for the period from October 2021 to December 2021 and March 2022, June 2022, September 2022, December 2022, March 2023, and June 2023 to determine the average usage of the vehicles.

To determine whether Verra properly billed DOT, the auditors judgmentally selected and reviewed the invoices for October, November, and December 2021, which were the months with the highest payments.

To determine whether the speeding events were properly rejected, the auditors also randomly selected and reviewed 195 out of 424,528 rejected events captured during November 15 through December 31, 2022, the period available at the time of the request. The auditors then reviewed video images of each sampled speeding event from Verra’s AXSIS system and inquired with Verra and DOT officials for explanations on any unclear determinations. The auditors also analyzed reports of NOLs issued and violation rejections for all fixed camera activity for December 2022, based on the availability of the data, to determine the effectiveness of the cameras and to identify the cameras that had high rejections. To determine whether there were any notable changes to the rejection categories, the auditors obtained speeding event rejection and NOL issuance statistics from January 2019 to June 2023 and analyzed and compared changes within the top five rejection categories.

The auditors also selected a random sample of 50 cameras to determine if annual calibration inspections were conducted by reviewing the most current calibration certificates.

Although the results of the sampling tests were not projectable to their respective populations, these results, together with the results of the other audit procedures and tests, provided a reasonable basis for the auditors to determine whether DOT monitored and had adequate controls over the Program, accurately issued NOLs for violations, and that speed cameras were functioning and maintained properly.

Addendum

See attachment.

Endnotes

[1] AXSIS is Verra’s proprietary back-office platform for processing violations, which, among other things, prints and mails citations, generates evidence packages and system generated reports, adjudication support, and manages data.

[2] A January 21, 2022, Streetsblog NYC article, “Speaker Adams Offers Misinformation on Speed Cameras.”

[3] Vision Zero is a citywide initiative with the goal of eliminating death and serious injuries from traffic incidents. As part of the initiative, the City lowered the default speed limit from 30 mph to 25 mph and installed cameras throughout the City for speeding, red light, and bus lane violations. The Dangerous Vehicle Abatement bill also allows the New York City Sheriff to seize and impound vehicles with 15 or more finally adjudicated school zone speed camera violations or five or more finally adjudicated red light camera violations during any 12-month period, unless the registered owner completes an approved safe vehicle operation course.

[4] Verra was formerly known as American Traffic Solutions, Inc. It meets some of its contractual obligations through subcontractors which Verra is responsible for overseeing.

[5] During Calendar Year 2021, Verra had two contracts with DOT for services providing to the Speed Camera Program. One of the contracts was originally solicited in 2013 for the automated red light and bus lane enforcement and the speed camera was added to the contract subsequently. When the Program expanded in 2019, DOT granted an emergency contract to Verra to support the expansion of the Speed Camera Program. The emergency contract expired on July 31, 2022, and the original contract with Verra for the red light, bus lane, and speed cameras was renewed twice. The current contract expires in December 2024.

[6] DOT does not have access to the rejected events data in AXSIS, including videos, images, or rejected locations.

[7] The fine for each speed camera NOL is $50.

[8] The other rejection categories included Event Not Within Enforceable Time Period, Garbage Truck Street Sweeper, and Other.