Executive Summary

Basement and cellar apartments, most of which exist within an informal rental market due to regulatory and financial barriers, currently house tens of thousands of New Yorkers, especially working-class immigrants and people of color.[i] As the housing crisis has grown, New York City and State have struggled – and mostly failed – to ensure tenant safety, to navigate conflicts between owners and basement-dwellers, or to provide a predictable system that could attract capital for improvements. One year ago, Hurricane Ida revealed the deadly cost of a decade of inaction, as heavy rains rapidly overwhelmed New York City’s sewer system and took the lives of 13 New Yorkers, 11 of whom drowned in mostly-unregulated basement apartments in Queens and Brooklyn.[ii]

While Ida’s heavy rainfall was unprecedented, and far beyond what the city’s sewer system was built to handle, climate change is accelerating the intensity and frequency of extreme weather events – so Ida will not be the last flash flood that puts the lives and homes of basement-dwellers at risk. Meanwhile, fires remain an even more frequent deadly risk for New Yorkers living in basement apartments. And the risk of eviction for basement-dwelling households, who have no tenant protections at all, presents its own potential disaster.

As cities and states around the country have adopted accessory dwelling unit legislation to ease the housing crisis, basements in New York have been stuck in limbo within a system that fails to support any of the stakeholders involved, and leaves basement-dwellers dangerously at-risk.[iii] There is no registry for basement apartments since they are mostly illegal. In the rare case when the City gains access to a basement unit to investigate a complaint of an illegal apartment, the Department of Buildings’ only option is to issue a vacate order – even if many basement residents would hardly be safer unhoused. Basement-dwellers cannot insist on even minimal protections or improvements (including, for example, the provision of a smoke detector) because they are not formal tenants, and currently lack any tenancy rights. Owners, many of whom are also low-income people of color, typically do not have the necessary resources, financial or otherwise, to meet the onerous regulatory burden to legalize the units.

Years of advocacy by the Basement Apartments Safe for Everyone (BASE) campaign resulted in the passage of the East New York Basement Pilot legislation in 2019 creating the first-ever pathway for the legal conversion of basement and cellar apartments in Brooklyn.[iv] The pilot was designed to bring several dozen basement units up to a modified code and ensure that occupants would not face dangers such as carbon monoxide poisoning, insufficient light and ventilation, and inadequate egress in the event of a fire. Due to the extensive work needed to bring the units up to even the modified code, the steep challenge of compelling action in an informal economy and, especially, the de Blasio Administration’s near elimination of the program through severe budget cuts in the wake of COVID-19, only eight homeowners remain active in the program.[v]

One year after Hurricane Ida, little meaningful action to address the limbo facing basement units has occurred, as legislation to provide a pathway to legalization for basement units stalled last session in Albany. As the City and State consider next steps in responding to the overlapping nature of our affordable housing and climate crises, the anniversary of Hurricane Ida must prompt bolder action – to provide basic, immediate protections to the thousands of New Yorkers currently living in basement units, as well as a pathway to legalization through State legislation.

Fortunately, New York City’s history offers a path forward. The issues facing basement dwellers strongly resemble challenges that loft tenants faced in the early 1980s: an informal system that left loft tenants without physical safety or legal protections; building owners without enforceable legal obligations or a clear path forward to meet them; and outdated City and State laws in the face of a rapidly changing city in crisis.

That crisis was met with the passage of the Loft Law, which provided both immediate protections and rights to tenants and established a comprehensive process for the long-term conversion of commercial and manufacturing buildings to legal, safe residences. While the Loft Law is far from perfect and has its own sets of challenges, it provides a strong model for bringing basement units into the light by requiring basic and potentially lifesaving physical improvements, giving tenants and owners fundamental rights and responsibilities, and supporting a pathway to full legalization.

It is essential that New York City and State act in a similarly bold manner to ensure the health and safety of an even more precarious group of New Yorkers. While the initial loft tenants were often artists without steady income,[vi] basement residents are in general even more vulnerable. Similarly, the owners of manufacturing buildings often had large portfolios and access to capital, whereas many of the owners of illegal basement and cellar apartments are low-income, and often immigrants and people of color who have historically been excluded from homeownership and face ongoing discrimination in access to financing. It is imperative we create a system that balances the needs of both tenants and owners.

This report by the New York City Comptroller’s office proposes the State adopt legislation that creates a new “Basement Resident Protection Law” to provide immediate physical and tenant protections to New Yorkers living in basement units, with clear rights and responsibilities for basement owners and dwellers, as part of a more comprehensive approach to legalizing and expanding accessory dwelling units.

The “Basement Resident Protection Law” would:

- Create a Basement Board reflective of the diverse constituencies affected to administer the program and financial support, develop inspection regimes, and enforce the provision of services and tenant protections;

- Require owners to register all currently occupied basement and cellar units with the Basement Board (resident protections would not be contingent on registration);

- Ensure robust, language accessible outreach to occupants in basement and cellar units to promote awareness of the new program;

- Mandate and provide funding to owners for the installation of basic safety measures, including carbon monoxide and smoke detectors and backflow preventers, to mitigate flooding risks during severe rain events like Hurricane Ida;

- Establish basic rights and responsibilities for basement-dwellers and owners, including the requirement to provide basic services and the legal right to collect rent;

- Immediately protect basement-dwellers from harassment, eviction, and the denial of essential services, and create new pathways for proactive enforcement and better occupancy data for the implementation of early flood warning systems;

- Provide a registration framework that supports and is coordinated with ongoing safety inspections and legalization efforts; and

- Require the City and State to provide affordable housing to New Yorkers living in units deemed to be so unfit for living due to egregious fire safety, habitability and flood risks that they must be vacated.

What is clear from Hurricane Ida is that action to address this issue simply cannot wait. The lives of occupants in basement and cellar apartments are at risk and every storm season poses another threat to occupants and homeowners. They both must be granted a process by which they can implement emergency safety protections, prevent tragic and avoidable deaths, and access support toward longer-term solutions.

Introduction

As climate change brings more intense and frequent storms, neighborhoods across the city will face increased flood risks in the coming decades. Superstorm Sandy and Hurricane Ida, remembered by every New Yorker who lived through them, caused devastation in our city in very different ways. Superstorm Sandy resulted in high winds and catastrophic storm surges in waterfront communities while Hurricane Ida resulted in record-setting rainfalls that led to flash flooding across large inland portions of New York City. As projects are underway to protect our coast lines from another storm like Sandy, we must also address the threats that Hurricane Ida made evident.

New York City has already developed and released Rainfall Ready[vii] and the New Normal[viii] plans that provide a range of short- and long-term interventions to address the risks of flash flooding. Such strategies include improvements to the storm sewer network, design and construction of innovative cloudburst (an intense rain event) and green infrastructure networks to manage intense rainfall, proactive debris clearance and inspections of catch basins, and citywide build-out of FloodNet sensors to capture real-time data on the frequency and severity of flooding. The City now faces the important task of fully implementing these plans. Efforts to address the risks of heavy rains will only be effective if they center frontline communities, prioritize capital investments in those areas that face greatest risks, and improve public communications with proactive and robust multi-lingual outreach.

Public investment in our environmental infrastructure is essential, but there are also immediate policy steps that we can take to prevent the worst possible outcomes from climate change in New York City. Of the 13 who died during Hurricane Ida in New York City, 11 drowned in their homes.[ix] Those who died were predominantly people of color, many of them immigrants, seeking affordable housing in unregulated basement apartments.[x] To avoid any additional deaths during flash flooding we must enact policies that immediately address the safety hazards of basement apartments while creating funding streams and pathways towards the full legalization of those units. New York State’s Loft Law, which established a comprehensive process for the conversion of commercial and manufacturing buildings to legal, safe residences provides a useful legislative framework from which we can build.

It is clear from the past decade that people of color, immigrant communities, seniors, and low-income New Yorkers will bear the brunt of the negative impacts of climate change. This has not happened by chance. Decades of unequal investment in public infrastructure, siting of harmful and polluting land uses, and redlining policies enacted by our city, state, and federal governments caused racial and economic disparities that continue today. The struggle to reverse the harmful effects caused by those choices will be long and cannot be solved with a silver bullet. Given the frequency at which severe storms and flash flooding will continue to occur, we must act now to protect New Yorkers living in basement apartments.

Overview of Basement and Cellar Apartments in NYC

An accessory dwelling unit (ADU) is a smaller, independent residential dwelling located on the same lot as another building in which one of the units is the primary residence of the owner of the building. The separate apartment must include a bathroom, kitchen, and additional living space. In New York City, the vast majority of ADUs are located underground.[xi]

Below-grade stories in New York City are classified as either basements or cellars: a cellar is a story in which 50% or more of the height from finished floor to ceiling is below the street grade and a basement is a story in which 50% or more of the height from finished floor to ceiling is above the street grade.[xii] New York State’s Multiple Dwelling Law (MDL), which is applicable to buildings with 3 or more units, prohibits any residential use in cellars but allows for residential use, including the creation of an ADU, in basements, as long as the unit complies with all other regulatory requirements.[xiii] The distinction between basements and cellars dates to the original passage of the MDL in 1929, a time in which many people, unable to find affordable housing, were crowded into below-ground apartments.

It is difficult to identify the exact number of residents that live in basement and cellar apartments in New York City because most of the units are illegal and have not been properly permitted or registered. However, advocates and researchers have estimated the number of occupied units using innovative data techniques. In 2008, Chhaya CDC and the Pratt Center for Community Development compared census data from 1990 and 2000 with records on construction and certificates of occupancy. In theory, the number of apartments reported to be available by census data should match the number of new units added through construction, but the researchers found a surplus of approximately 114,000 units. From this number they extrapolated that as many as 300,000 to 500,000 New Yorkers may live in basement and cellar apartments across the city.[xiv]

In fall 2021, the Pratt Center for Community Development updated their 2008 joint research with Chhaya CDC and estimated that about 30,395 illegal basement or cellar apartments are located within just eight community districts, all of which are primarily communities of color.[xv] The variation in the estimates between 2008 and 2021 indicate the immense difficulty in estimating the number of occupied basement and cellar apartments in an ever-changing New York City real estate market and makes clear the need for an approach to safety and regulation that prioritizes door to door outreach and intervention.

Given the demographics of the neighborhoods within which these units are located and based on the experience of advocates, the residents of basement and cellar ADUs are predominantly immigrants, people of color, and working-class New Yorkers. These residents are not served by the traditional housing market and generally cannot afford to live elsewhere. Unless we take immediate action to provide opportunities for tenancy recognition and installation of emergency safety measures towards a pathway of full legalization, it will be these residents that continue to bear the brunt of future climate disasters.[xvi]

Climate Risks to Basements and Cellars in NYC

The Comptroller’s office conducted a geographic analysis to better understand the potential scope of flood risks facing one-, two-, and three-family homes with basements or cellars in New York City. Our analysis is based on the methodology developed by the Pratt Center for Community Development for their interactive Basement Data Dashboard.[xvii] Given current data limitations, our analysis does not attempt to estimate what share of those basements or cellars are currently occupied by New Yorkers. For the purposes of this report, any reference to basements and cellars refers only to basements and cellars in one-, two, and three-family homes. The analysis assumes one basement or cellar per tax lot.

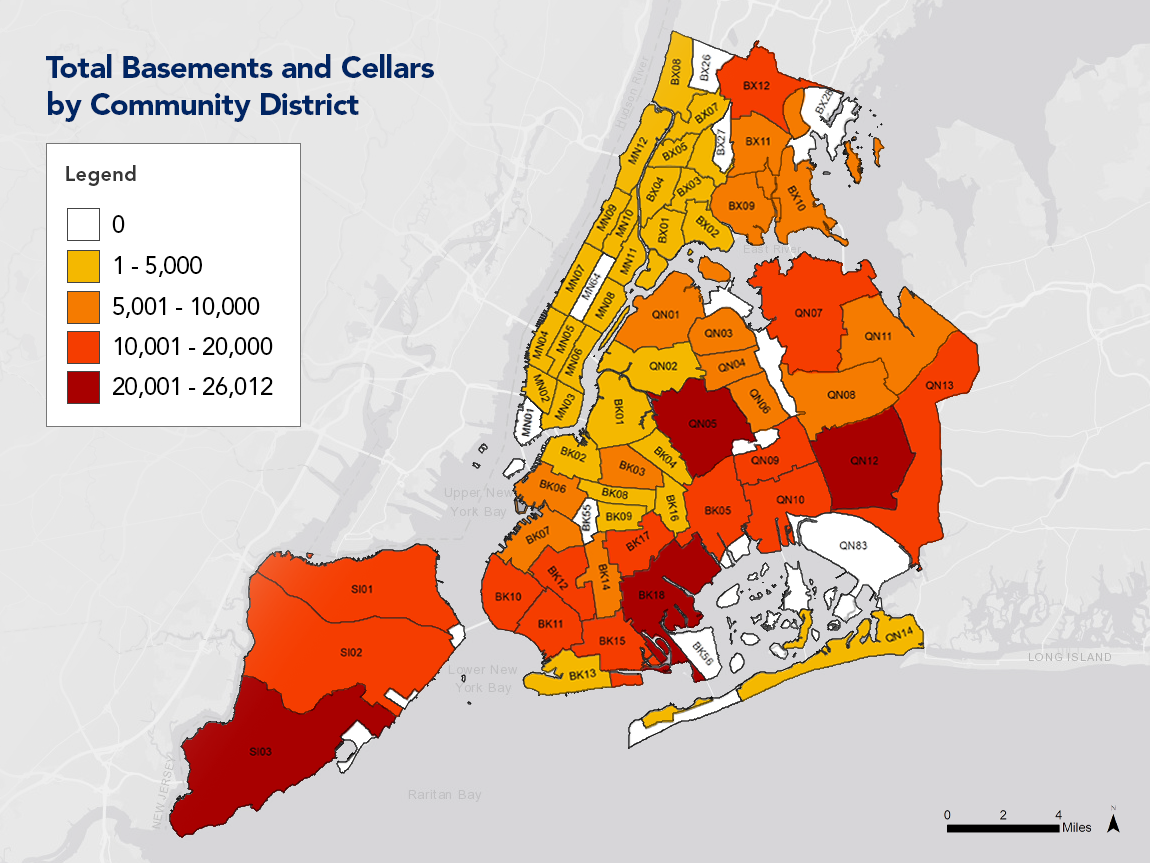

Figure 1 illustrates the estimated distribution of basements and cellars by community district utilizing tax lot data. Our analysis estimates that there are approximately 424,800 basements and cellars in one-, two-, and three-family homes in across the five boroughs.[1] Three of the community districts with the highest concentration of basements and cellars, Queens 12, Queens 5, and Brooklyn 18,[2] are extremely diverse. In all three of these community districts, over 35% of the population are immigrants. Nearly 60% of the population in both Queens 12 and Brooklyn 18 is Black and over 35% of the residents in Queens 5 are Latino.[xviii]

Figure 1: Estimated Basement and Cellars by Community District

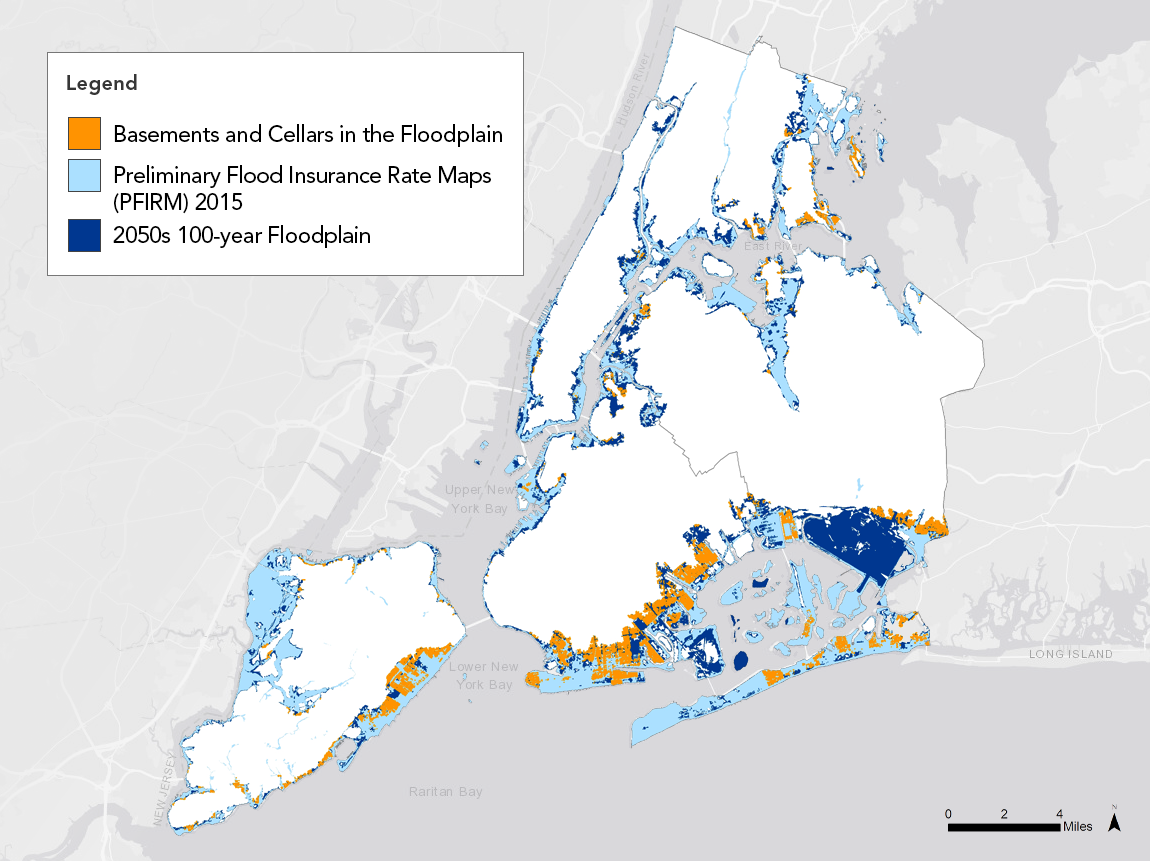

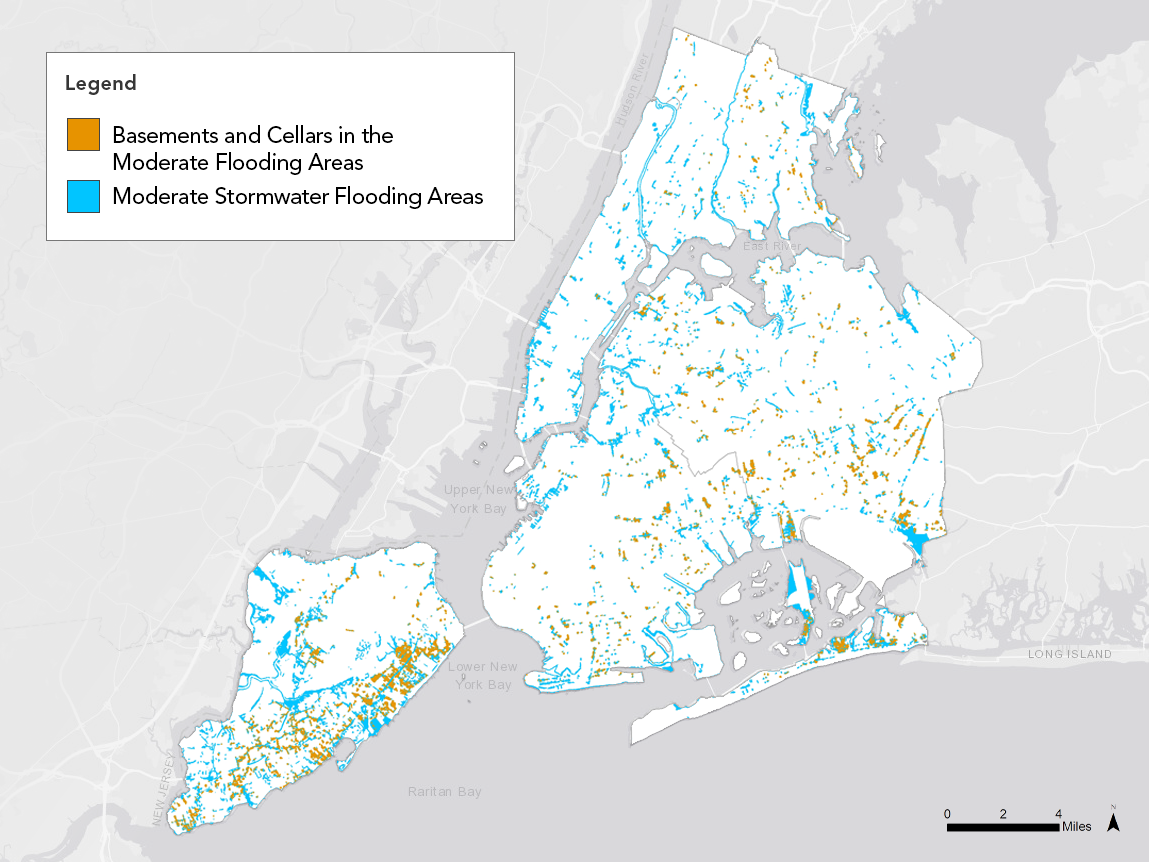

In total, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that about 10%, or 43,000, basements and cellars in one, two, and three family buildings in New York City are currently facing some type of flooding risk. As storms intensify with climate change, the number of basement and cellars facing coastal and extreme rainfall flood risk is estimated to grow to 136,200, a third of all basements and cellars by the 2050s. The analysis below also breaks down risk by specific flood type.

Coastal flooding: Hurricanes, nor’easters, and tropical storms result in sustained destructive winds and coastal storm surge that pose risks to communities and infrastructure located in the floodplain. Around 25,300 (or 6%) of total estimated basements and cellars are located in the current 100-year floodplain. In 30 years, the time horizon for standard mortgages, the number of basements and cellars in the 100-year floodplain will grow to 44,700 (or 10.5%) as the severity of coastal storms increase with climate change.

Tidal flooding: A smaller subset of 1,600 basements and cellars in coastal areas are also at risk of being regularly or permanently inundated as sea level rise causes tidal inundation of waterfront lands by the 2050s.

Figure 2: Basements and Cellars at Risk of Coastal Flooding

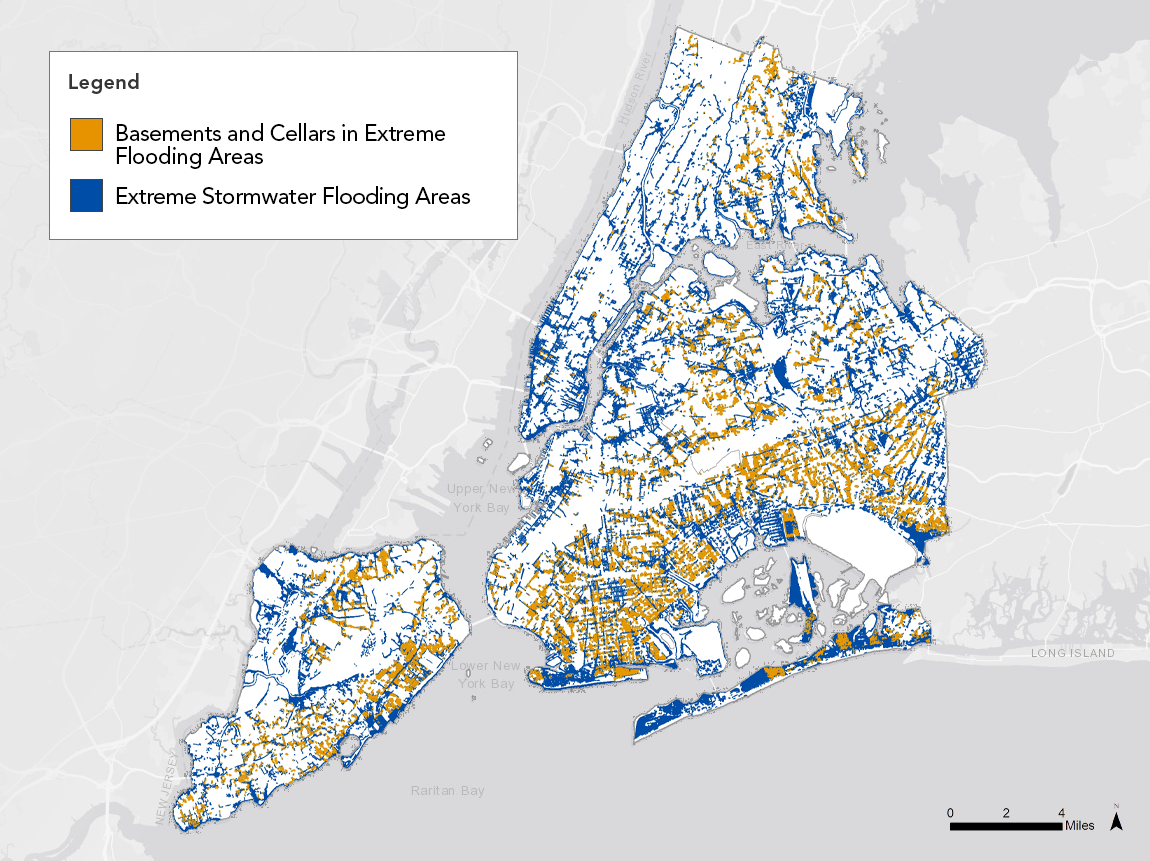

Stormwater flooding: Intense rain events, also known as “cloudbursts,” result in flash flooding, often in inland neighborhoods outside of the coastal floodplain. During cloudburst storms, like Hurricane Ida, heavy rainfall exceeds the capacity of the City’s sewer system, causing huge volumes of stormwater—along with raw sewage in combined stormwater areas—to flow back into the city’s streets, subways, and low-lying homes.[xix]

An estimated 23,200 (5.5%) basements and cellars are in areas at risk of flooding from moderate rainfall, as shown in Figure 3. With climate change, storms will intensify in future decades which will bring more frequent extreme rainfall events by the 2050s. Extreme rainfall will significantly increase flood risk for underground apartments, affecting 136,200 (28%) basements and cellars. About 5,500 basements and cellars, or 1.3%, face both coastal and moderate stormwater flood risks today. The majority of basements and cellars facing both flooding risks are in the south shore of Staten Island, Manhattan Beach in Brooklyn, City Island and Throggs Neck in the Bronx, and the Rockaways, Queens Village, Bellrose and Rosedale in Queens.

Figure 3: Basement and Cellars at Risk of Moderate Stormwater Flooding

Figure 4: Basements and Cellars at Risk of Extreme Stormwater Flooding

Though we cannot know for certain how many of the above at-risk units are currently occupied due to data limitations, the flood maps make clear that there is a growing crisis facing basement and cellar tenants. Homeowners throughout New York City, but particularly in historic Black homeownership neighborhoods such as Hollis and Jamaica, Queens and Canarsie, Brooklyn are at risk for increased flooding over the coming decades. Lack of available data on tenancy limits the efficacy of many policy interventions, such as early flood warning systems, and highlights the need for programs that prioritize door-to-door outreach as flood risks may vary greatly, even between homes located on the same block. The above analysis could serve as a useful starting place for prioritization of the City and State’s direct outreach as storms intensify.

Efforts to Legalize Basement Units

There has been a long history of advocacy efforts to recognize tenancy and legalize basement and cellar apartments in New York City. The Basement Apartments Safe for Everyone (BASE) Coalition was formed in 2006 and includes advocacy and organizing groups from across the city.[3] In 2008 the Pratt Center for Community Development and Chhaya CDC co-released a landmark report, “New York’s Housing Underground,” which included the initial tally of potentially occupied units discussed above.[xx] The report brought much-needed attention to this issue, enumerated the problems, and proffered several recommendations. The BASE Coalition’s demands have since evolved with new data, research, and political realities, but remain remarkably similar.

In 2016, BASE Coalition members, including the locally based group Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation fought for and won the first program to legalize basement and cellar units in the community-wide rezoning of East New York in Brooklyn. Due in large part to this organizing, the local Council Members Rafael Espinal and Inez Barron secured a commitment from Mayor de Blasio to implement a pilot program. In 2019, following a thorough and collaborative research and program design process which included advocates, technical experts, City agencies, and City Council Members, the New York City Council passed Local Law 49, sponsored by then Council Member Brad Lander.[xxi]

Converting a basement into a legal ADU is an onerous, expensive, and complicated process. The legislation eased some of the barriers to ADU legalization, such as reducing ceiling heights under certain conditions, allowing habitable apartments to be created in cellars with at least 2 feet of height above the grade plane, easing requirements around new certificates of occupancy, and creating opportunities for the waiver of existing DOB penalties for participating owners. However, the MDL, which the Council was precluded from superseding, limited the ability for the City to waive requirements. The legislation resulted in HPD’s creation of the Basement Apartment Conversion Pilot Program (BACPP).[xxii]

BACPP’s goal is to bring more units into compliance through capital improvements and upgrades financed with city subsidy. Under BACPP, the City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) was required to conduct outreach and provide financial and technical assistance, either directly or through not-for-profit partners, to owners of one, two, and three family homes within certain areas of Brooklyn CD 5. HPD was also tasked with creating affordable financing options and program development.While there are many factors that vary between homeowners, the typical timeline of a BACPP project is about two to four years.

First, not-for-profit partners conduct outreach to identify homeowners who may be interested in participating in the program. Once a homeowner expresses interest, they are vetted for eligibility based on their income and their basement or cellar is inspected to determine if the physical characteristics make legalization of the unit possible. If both the owner and the unit are found eligible, an architect develops a scope of work and receives bids from contractors. If the bids are over the maximum subsidy amount of $120,000, the homeowner must contribute funds to the project either through savings or additional financing sources. If the project cost is below the maximum subsidy amount, or if the owner can secure additional money to cover costs, the project moves towards a loan closing. At the loan closing the owner will sign a regulatory agreement with the City of New York that dictates the terms of the funding, including requirements that the owner rent the newly legalized ADU at an affordable rate and continue to live in their home as their primary residence, among several other requirements.[xxiii] This pre-development process could take anywhere from 6-12 months depending on the capacity of the individual homeowner and the resources available at HPD and the nonprofits administering the program.

Once the funding is available, construction starts. If there is a tenant already living in the basement or cellar, they will be temporarily relocated with a right to return to the unit following rehabilitation. Depending on the scope of work, the construction process could last between 12 and 18 months. Following construction, the Department of Buildings inspects the unit, signs-off on the construction, and finally issues a modified Certificate of Occupancy (C of O). It could take an additional 3 to 6 months following the completion of construction for the issuance of the C of O, after which time the unit is fully legalized and ready to be rented.

BACPP was an historic victory towards the legalization of basement and cellar ADUs. However, due in part to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent budget cuts, very few projects were initiated, even after the eligibility period for the program was extended in 2021. According to estimates published by the City, approximately 100 homeowners out of an eligible 8,000 reached the home assessment step laid out in the BACPP process above and, per reporting following Hurricane Ida, only eight homeowners remain in the program due to severe budget cuts.[xxiv]

Barriers to the success of the BACPP include the high cost of construction and relocation, with the estimated conversion cost nearly two to three times as expensive as the City’s maximum subsidy of $120,000, and requirements related to the MDL that can only be changed at the State level.[xxv] The existing condition of the home is also frequently a problem, as many residents need critical repairs to the primary unit in addition to the renovations required in order to legalize the ADU. The program functioned exactly as a pilot should: illuminating the remaining barriers to success while successfully completing several projects. We must build on this victory by addressing the critical issues that hindered more expansive achievement and by providing a process by which tenants can receive immediate safety measures and protections that cannot wait.

In addition to the Basement Apartment Conversion Pilot Program, former Mayor Bill de Blasio made several commitments following the devastating deaths during Hurricane Ida. The commitments related to basement and cellar apartments included creating a citywide database of all subgrade spaces, including occupied basement and cellar apartments; developing mechanisms to provide better communication to basement residents in the event of flash flooding or other severe storms; improving first responders abilities to help tenants in basements in emergencies by running drills and positioning FDNY in particular to respond in the event of flash flooding; contracting with local community organizations to conduct door-to-door outreach to tenants in basement and cellar apartments within flood zones to identify them and provide information on emergency evacuation; connecting shared driveway dry wells to city sewers; and expanding the BACPP citywide.[xxvi] Mayor Eric Adam’s Housing Plan[xxvii] mentioned the legalization of ADUs and on August 26, 2022, the Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget released its “CDBG-DR Draft Action Plan for the Remnants of Hurricane Ida” which committed federal funds to continue studying the feasibility of converting basement apartments, update the City’s evacuation plans for persons living in basement apartments, and create a database of subgrade spaces including those that may be used as basement apartments.[xxviii]

During the 2021-2022 session in Albany, there was an effort to pass statewide legislation that would require localities across the state to amend zoning and building codes to ease the creation of legal ADUs. The legislation includes basement and cellar units, as well as garage units, backyard cottages, granny flats, and other types of ADUs that are common across the State but less so within New York City. The proposed legislation is part of a broader fair housing effort to require local municipalities to eliminate single-family exclusionary zoning to increase the region’s available housing stock. A-4854/S-4547 sought to significantly reduce barriers to converting basements into a legal ADU by addressing the following issues:

Chart 1: Modifications Proposed by A-4854/S-4547

| Modification | Description |

| Allowing cellars to be converted to legal ADUs | Permitting cellar units that are more than two feet above ground to convert would better meet health and safety goals than the current distinction. |

| Easing Floor Area Ratio (FAR) requirements | Cellars are not currently counted in a building’s FAR calculation. Easing this requirement would not increase the size of the building but fix the problem of non-conforming land use with local zoning. |

| Waiving parking requirements | Local zoning often requires the addition of a parking space with an additional unit, which can make the legalization of an ADU infeasible. |

| Exempting ADUs from the requirements of the Multiple Dwelling Law | Adding an ADU to a two-family home triggers the MDL, a far more onerous regulatory scheme that typically makes the addition of an ADU infeasible financially. |

| Permitting 7-foot ceilings | International building standards allow 7-foot ceilings. Higher ceiling height requirements often make the legalization of ADUs financially or architecturally impossible. |

| Reducing minimum square footage requirements for the ADU | Reducing the minimum square footage requirement to 200 square feet in NYC. |

| Easing setback requirements | The footprint of the building is typically not expanded with the creation of an ADU, but zoning requirements must be eased in certain circumstances to account for the legalization of a new unit. |

| Eliminating the need for a new Certificate of Occupancy (C of O) | The process of obtaining a new C of O is onerous and there are other methods by which the City’s Department of Buildings can certify the safety of the unit. |

The legislation gained significant momentum when Governor Kathy Hochul included it in her 2022 State of the State Agenda, but it faced considerable pushback from certain parts of the New York State legislature and was not enacted.[xxix] The fair housing goals of the original legislation are critical, and the fight at the State level to prohibit exclusionary zoning practices continues. However, in response to the urgent need for ADU legislation in New York City, Assemblymember Harvey Epstein and State Senator Brian Kavanaugh introduced a narrower bill that would authorize New York City to enact an ADU legalization program notwithstanding the MDL.[xxx] Unfortunately, this legislation was also not enacted in the 2022 session.

Hurricane Ida made clear that thousands of vulnerable New Yorkers are currently living in unsafe basement units without the most basic safety measures in place, putting them directly in harm’s way in the face of increasingly frequent and severe storms due to climate change. The City and State must work together to address this crisis urgently.

A Useful Precedent: New York City’s Loft Law

This is far from the first time in New York City’s history that we have faced an urgent crisis of vulnerable tenants living in unsafe conditions. Beginning in the 1960s, thousands of tenants moved into loft buildings as the manufacturing industry declined.[xxxi] Landlords struggling to find new industrial tenants were eager to lease them to residential tenants. Some landlords were simply willing to collect rent in any form to avoid foreclosure and maintain their properties, while others were less scrupulous and saw an opportunity to price-gouge tenants to whom they did not need to provide extensive services.

By the time the initial leases expired in the early 1980s, rental prices in Lower Manhattan, where the first residentially occupied lofts were located, had risen significantly.[xxxii] The residents were unwilling to walk away from the homes they had improved over the years and asserted their rights under a law that prohibited a landlord from evicting or collecting rent if they knowingly rented a manufacturing space to a residential tenant without the proper Certificate of Occupancy (C of O).[xxxiii] This rent strike, as well as additional legislative organizing, created the conditions in which the State legislature was compelled to enact the Loft Law of 1982.

The Loft Law amended the MDL to create a new class of buildings, known as interim multiple dwellings (IMDs). Prior to legislation, New Yorkers residing in converted commercial or manufacturing buildings had little fire and safety protections and did not have a process to require their landlord to install those protections or to insist upon basic services such as heat, hot water, and electricity. Eligible tenants secured several rights, such as protection from eviction, the right to essential services, and the right to receive a rent-regulated lease following the legalization of the unit. Landlords benefited from a clear, more achievable process through which they could receive a residential C of O for their buildings and legally rent the units, including modifications and easing of the requirements of the MDL.

The circumstances that led to the Loft Law and the legislative spirit of the bill are similar to the current situation in New York City’s occupied cellar and basement apartments. With the manufacturing industry fleeing New York City, many loft landlords turned to artists looking for affordable joint-live workspaces to collect rental income. The legislature, aware of the unlikelihood that industry would return to Lower Manhattan en masse, was interested in keeping these neighborhoods occupied and in maintaining the financial health of the properties. There was therefore a mutual benefit between tenants looking for a particular type of affordable housing and landlords who needed a new type of tenant and income stream given changes to the global economy that were largely uncontrollable at the local level.

Today, there is a massive shortage of affordable housing in New York, causing many of the most financially precarious New Yorkers to turn to illegal, often unsafe apartments for housing. As we work towards ending the affordable housing crisis, we must acknowledge that people will continue to seek shelter in basement and cellar apartments regardless of the apartment’s legal status. Similarly, while some owners of buildings with illegal basement apartments are predatory actors seeking profit above all else, many others are homeowners facing their own rising housing costs or other forms of financial precarity, who have rented extra space out to family or friends in order to make ends meet. When these two groups find each other there is a mutual benefit and a mutual, yet asymmetric, risk. Homeowners risk high fines for illegally renting out space while tenants face serious health and safety concerns. Legalizing these units reduces this risk and serves both constituencies by providing much needed, safe affordable housing to working-class New Yorkers, and providing more reliable, legal cash flow to owners who may be struggling to keep their homes due to rising costs.

The Loft Law was by no means perfect. Several amendments to the bill have been made over the years. Amendments in 2010, 2013, 2015 and 2019 expanded the covered units, and legislation signed at the end of 2021 provided loft tenants with access to housing court to address harassment and neglect and expanded harassment and eviction protections while a case remains pending before the Loft Board. However, provisions permitting the sale of rights to the IMD landlord remain despite efforts to reform. Though imperfect, the law did, however, confront the realities of a changing city and prioritize tenants’ safety and protections along the way.

Hurricane Ida made clear that a “harm reduction” approach to addressing this issue simply cannot wait. Every storm season presents greater risks to tenants and owners alike. They must be granted a process by which they can implement emergency safety protections, access support, and prevent tragic and avoidable deaths.

Creation of a Basement Board

The State should pursue the passage of a “Basement Resident Protection Law” to create a new Basement Board, based on the Loft Board.[4] With the passage of such a law, any occupied basement or cellar unit, as of the enactment of the law, would be automatically covered. Owners of buildings with occupied basement and cellar apartments would be legally obligated to register their units by a certain date and all occupants living in a basement or cellar apartment, regardless of whether the owner had properly registered the unit, would receive certain rights. The legislation would authorize the temporary legal status of basement and cellar apartments for five years. Community outreach, technical assistance support and financial benefits would notify and create incentives for owners to register their units while deadlines for compliance and ability to levy fines would provide enforcement power to the City, if necessary.

Outreach

Under the proposed Basement Resident Protection Law, the City and State would be required to fund local community-based organizations to conduct language accessible outreach to both owners and occupants living in buildings with basement and cellar apartments to inform them of their obligations and rights. Under the law, the City and State would also be required to directly fund and implement widespread outreach and notification, such as advertising in subway lines that serve the neighborhoods in which the majority of the ADUs are located, television, radio and print ads, participation in Community and Borough Board meetings, among other forms of outreach.

Safety Inspections

Safety inspections of basement and cellar units would be conducted over time. Under existing regulations, nearly all basement and cellar units would be deemed uninhabitable and be issued a vacate order. Therefore, one of the first tasks of the Basement Board would be developing flood and fire risk profiles, both for the prioritization of inspections and for the determination of habitability following the physical inspection of the unit. Those risk profiles would balance tenant safety with unnecessary displacement. The 5,500 basement and cellars at risk for both inland and coastal flooding, identified previously in this report, are a clear place to begin inspections, especially in neighborhoods that data analysis has shown may have a concentration of occupied basement or cellar units, such as Canarsie and Flatlands in Community District 18 in Brooklyn.

If it is ever determined that the unit is uninhabitable, due to fire, flooding, or other safety concerns, the resident would automatically receive a rental-assistance voucher and assistance from a community-based partner in securing affordable housing. An automatic voucher provision is an improvement on the current system in which evicted basement dwellers must go through New York City’s shelter system before they can access rental assistance. Given the demographics of many basement dwellers, it is crucial that City and State work to make rental assistance accessible to all New Yorkers regardless of immigration status.[5]

In addition, the owner of the building would also be eligible to receive assistance from community partners, including referrals to trained homeownership counselors who would provide financial counseling and work to secure financial assistance for the homeowner, if needed after the loss of rental income.

Rights and Responsibilities of Owners and Occupants

The law would require all owners of currently occupied basement or cellar units to register with the Basement Board. Failure to do so could result in enforcement action from regulatory agencies, including the issuance of fines.

Owners would be required to immediately install – with financial assistance from the City and State – the following safety measures and ongoing services:

- A smoke and carbon monoxide detector: Fire safety was the primary concern for basement and cellar ADUs prior to Hurricane Ida, so it is essential that these units have these minimum protections put into place.

- A backwater protection valve (also known as a back flow preventer valve): A backwater valve can help prevent sewer water from rising from the city sewer into basement and cellar ADUs. The back water protection valve closes and blocks sewer water from entering the unit.[xxxiv]

- Essential services: Provision of heat, hot water, and electricity to tenants on an ongoing basis.

The Basement Board could also require additional safety measures, such as flood sensors or fire suppression technology, especially as new or improved technology is developed.[xxxv] Registration of the unit would confer the owner the right to collect rent, and the right to legally pursue an eviction for non-payment of rent or other nuisance behavior in violation of the terms of the lease. Tenants would be entitled to a lease and receive protections from eviction, including immediate good cause eviction protections, which provides tenants the right to a renewal lease with annual rent increases no greater than 3% or 1.5 times the consumer price index. Tenants of basement and cellar units would have the right to report the lack of heat, hot water, electricity, or landlord harassment to the Basement Board, which would investigate and assess fines accordingly, in addition to adjudicating disputes between tenants and owners.

Technical and Financial Assistance for Owners

With the registration of the unit, owners would be eligible for fine forgiveness related to penalties for past illegal use of a basement or cellar should they exist, and first access to funding and technical assistance for the installation of the emergency safety measures. The first owners to apply would also be prioritized for financial programs and assistance for full legalization, including the provision of technical assistance to shepherd them through that process in a manner similar to the BACCP. Low-income homeowners, regardless of the timing of their registration, would be entitled to technical assistance and financial support from the City, State, and/or community-based partners. Owners would be incentivized to fully legalize the ADU by the end of the 5-year authorization, bringing basements from “interim” dwellings to housing units covered by other applicable City and State laws.

Additional Protection and Resources

With this program in place and units registered with the Basement Board, the City, State, and community partners would have more accurate data and listservs to implement early warning systems, an initiative that would make a real difference but has been challenging to put in place, in the face of forthcoming floods. The city would also be better positioned to implement proactive enforcement approaches to these units, to address safety concerns more effectively, and better adapt to emerging risks in the face of climate change.

A program such as this will require appropriate funding and resources to succeed. The legislation must come along with funding for robust community-based outreach in addition to broad advertising campaigns to ensure that both tenants and owners are informed of their rights and responsibilities. To incentivize owners to come forward to register units, the City and State should commit to covering the cost of purchasing and installing the emergency tenant protection measures including, but not limited to, a smoke and carbon monoxide detector and a backflow preventer. The City and State must also appropriately fund a voucher program for tenants who must be rehoused in order to keep them safe. These funds must be provided in addition to a significant capital investment from the City and State, which is needed in order to implement full legalization programs. The $85 million included in the State’s five-year housing plan is a significant commitment made after years of organizing and is a good starting place for further investment.

Conclusion

One year ago, Hurricane Ida took the lives of 13 New Yorkers, 11 of whom drowned in their basement apartments in Queens and Brooklyn. As storms intensify with climate change, our analysis indicates that the portion of basements and cellars at-risk for flooding is estimated to grow from ten percent to roughly a third of all basements and cellars in one-, two-, and three- family homes by the 2050s. While only a portion of those basements and cellars are occupied, research has shown that the majority of New Yorkers who live in these units are working class, immigrants, and people of color who cannot afford to live elsewhere. Many of the owners of homes with basement and cellar apartments are also low-income people of color.[xxxvi] Without action from the City and State, it will be these tenants and homeowners who continue to suffer losses in the face of climate change.

We hope the Basement Board proposal outlined in this report sparks conversation and incites additional action. A thorough engagement process with diverse stakeholders will be needed to further develop this proposal to ensure it meets the needs of New York City’s impacted communities and is appropriately resourced. The development of risk profiles of occupied units will support the prioritization of safety inspections and inform the amount of funding needed to rehouse tenants in unhabitable units. The protections proposed in this report must be secured in addition to the passage of and robust funding for the full legalization of basement apartments.

Acknowledgements

Celeste Hornbach, Senior Policy Advisor, was the lead author of this report with support from Annie Levers, Assistant Comptroller for Policy and Louise Yeung, Chief Climate Officer. The data analysis was led by Robert Callahan, Director of Policy Analytics and Jacob Bogitsh, Senior Policy Analyst. Report design was completed by Angela Chen, Senior Web Developer and Graphic Designer, and Archer Hutchinson, Graphic Designer. Additional research was completed by Louis Cholden-Brown, Senior Advisor and Special Counsel for Policy and Innovation.

Thank you to the Basement Apartments Safe for Everyone (BASE) Coalition for their feedback and for the decades of work that they have done advocating for basement tenant and owners. Additional thanks are owed to Sylvia Morse and Rebekah Morris at the Pratt Center for Community Development for generously sharing their data methodology with our office. Thank you to Make the Road NY, Legal Aid Society, and the Regional Plan Association for providing thoughtful feedback on the report.

Methodology

To identify tax lots with basements and cellars in one-, two-, and three-family homes, the Comptroller’s Office collaborated with the Pratt Center for Community Development. The analysis conducted in this report was informed by the methodology used to produce their Basements Data Dashboard. The process filters the Department of City Planning’s MapPLUTO 22v2 dataset to include only residential tax lots reported as containing one to three units with either a basement or a cellar feature. The Comptroller’s Office’s identified approximately 50,000 more units owned by an LLC, which the Pratt Center excluded.

Once the universe of tax lots with basements and cellars was identified, the universe was then spatially joined to the New York City Planning Community District Tabulation Area Shapefile and exported as a database file (.dbf) to identify the number of tax lots in each community district. The analysis assumed one basement or cellar per tax lot, but does not assume that the basement or cellars are occupied.

To assess the number basement and cellars facing flood risk, the tax lots with basements and cellars were then overlaid with shapefiles for several flooding types:

- Coastal flooding: Current coastal flooding was determined using the 2015 FEMA’s Preliminary Flood Insurance Rate Work Map (PFIRM). Future coastal flooding was determined using the 2050s 100-year floodplain, derived from climate projections by the New York City Panel on Climate Change (NPCC).[6]

- Tidal flooding: areas anticipated to be inundated by sea level rise were determined using the 90th percentile NPCC projections for high tide in the 2050s.[7]

- Stormwater flooding: areas at risk of stormwater flooding were determined using the Moderate and Extreme Rainfall Flooding Scenarios developed by the NYC Department of Environmental Protection.

A “Select by Location” query was performed to identify tax lots falling fully or partially within each floodplain geography. The selection was limited to the explicit geography of the published maps without an additional buffer zone. Selected lots were then exported as database files and totaled to assess city-wide, boroughwide, and community district statistics.

The total number of unduplicated basements and cellars currently facing any type of flood risk was calculated by summing the tax lots that intersected with either the 2015 PFIRM, the Moderate Stormwater Flooding boundaries, or both geographies. The total number of unduplicated basements and cellars facing future flood risk was calculated by summing the tax lots that intersected the 2050s 100-year floodplain, the Extreme Stormwater Flooding boundaries, or both geographies.

Footnotes

[1] Our estimate is slightly higher than the number produced by the Pratt Center due to the inclusion of homes owned by Limited Liability Companies or Limited Partnerships as these properties would be covered by our proposal.

[2] Queens Community District 12 is composed of the following neighborhoods: Hollis, Jamaica, Jamaica Center, North Springfield Gardens, Rochdale, South Jamaica, St. Albans. Queens Community District 5 is composed of the following neighborhoods: Glendale, Maspeth, Middle Village, Ridgewood. Brooklyn Community District 5 is composed of the following neighborhoods: Bergen Beach, Canarsie, Flatlands, Georgetown, Marine Park, Mill Basin, Mill Island, Paerdegat Basin.

[3] Current BASE members include: Chhaya Community Development Corp, Communities Resist, Cypress Hills Local Development Corp., Center for New York City Neighborhoods, Minkwon Center, Neighborhood Housing Services of Jamaica, Pratt Center for Community Development, and Queens Legal Services.

[4] The Basement Board would consist of members appointed by the Mayor of New York City and approved by a majority vote of the New York City Council (also known as “advice and consent of the Council”). The Council’s hearing and approval process would ensure members of the Basement Board are representative of the diverse constituencies, including homeowners and tenants, impacted by its policymaking and create more accountability and transparency in the appointment process.

[5] This can be done with the passage of Housing Access Voucher Program (S2804/A3701), which explicitly states that housing assistance would be available without regard to immigration status.

[6] Per the NYC Department of City Planning (DCP) Flood Hazard Mapper, “the future floodplain shapefile is based on a layering of high estimates for sea level rise by the NPCC on top of the 2013 PFIRM base flood elevations for the 1% annual chance floodplain.”

[7] Per DCP Flood Hazard Mapper, these layers were “based on a 2010 Digital Elevation Model for New York City using a modified bathtub approach provided by NOAA. The layers do not accurately depict inundation on over-water structures, such as docks and piers, and are not reliable for areas outside of New York City. The layers illustrate the scale of potential flooding on land, not the exact location, and do not account for erosion, rapid subsidence, or future construction.”

Endnotes

[i] Zaveri, M., Haag, M, Playford, A. & Schweber, N. (2021, September 2). N.Y.C. storm’s toll highlighted New York’s shadow world of basement apartments. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/02/nyregion/nyc-basement-apartments-flooding.html

[ii] Hogan, Gwynne. (2022, July 12) NYC basement apartments are still unregulated despite Hurricane Ida deaths last fall. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/07/12/1111131985/nyc-basement-apartments-are-still-unregulated-despite-hurricane-ida-deaths-last-

[iii] Accessory Dwelling Units.org (n.d.) ADU Regulations by City. https://accessorydwellings.org/adu-regulations-by-city/

[iv] New York City Housing Preservation & Development (n.d.) Home Repair and Preservation Financing: Basement Apartment Conversion Pilot. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/hpd/services-and-information/basement-apartment-conversion-pilot-program.page

[v] Zaveri, Mihir. (2021, September 14). 11 Deaths Put Focus on N.Y.C.’s Failure to Make Basement Apartments Safe. New York Times. 11 Deaths Put Focus on N.Y.C.’s Failure to Make Basement Apartments Safe – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

[vi] Lange, Alexandra (2022, June 22). How the New York Loft Reclaimed Industrial Grit as Urban Luxury. Blomberg CityLab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-06-22/a-design-history-of-the-new-york-loft

[vii] New York City Department of Environmental Protection. (n.d.) Rainfall Ready NYC Action Plan. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/dep/whats-new/rainfall-ready-nyc.page

[viii] New York City Office of the Deputy Mayor for Administration. (2022) The New Normal: Combatting Storm-Related Extreme Weather in New York City. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/orr/pdf/publications/WeatherReport.pdf

[ix] Hogan, Gwynne. (2022, July 12) NYC basement apartments are still unregulated despite Hurricane Ida deaths last fall. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/07/12/1111131985/nyc-basement-apartments-are-still-unregulated-despite-hurricane-ida-deaths-last-

[x] Burke, M. & Griffith, J. (2021, September 4). Ida victims: What we know about those killed in N.Y., N.J. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/ida-victims-what-we-know-about-those-killed-n-y-n1278469

[xi] American Planning Association, (n.d.) Accessory Dwelling Units. https://www.planning.org/knowledgebase/accessorydwellings/

[xii] New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, (n.d.) Housing Quality / Safety Basements and Cellars. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/hpd/services-and-information/basement-and-cellar.page#:~:text=A%20basement%20is%20a%20story,an%20adult%20to%20fit%20through.

[xiii] Multiple Dwelling Law, https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/buildings/pdf/MultipleDwellingLaw.pdf

[xiv] Neuwirth, Robert. (March 2008). New York’s Housing Underground: A Refuge and Resource. Chhaya Community Development Corporation. Layout 1 (chhayacdc.org)

[xv] Afridi, L. & Morris, R. (October 2021). New York’s Housing Underground: 13 Years Later. Pratt Center for Community Development. https://prattcenter.net/uploads/1021/1634833975615756/Pratt_Center_New_Yorks_Housing_Undergound_13_Years_Later_102121.pdf

[xvi] The White House. (n.d.). Environmental Justice. Environmental Justice – The White House

[xvii] Pratt Center for Community Development (n.d.) Basements Data Dashboard. https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/pratt.center/viz/NYCBasementsandCellars/CouncilDistricts

[xviii] New York City Department of City Planning. (n.d.) Community District Profiles. https://communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov/

[xix] New York City Mayor’s Office of Resiliency (May 2021). New York Stormwater Resiliency Plan: Helping New Yorkers understand and manage vulnerabilities from extreme rain. stormwater-resiliency-plan.pdf (nyc.gov)

[xx] Neuwirth, Robert. (March 2008). New York’s Housing Underground: A Refuge and Resource. Chhaya Community Development Corporation. Layout 1 (chhayacdc.org)

[xxi] Pratt Center for Community Development. (August 2020). Basement Apartment Conversions. https://prattcenter.net/uploads/0221/1612807654673221/Pratt_Center_BASE_Campaign_Presentation_reduced.pdf

[xxii] New York City, N.Y. Local Law 49 of 2019 (uncodified).

[xxiii] Pratt Center for Community Development. (n.d.) The Basement Apartment Conversion Pilot Program: Homeowner Resource Guide. https://prattcenter.net/uploads/0820/1597188504756703/BACPP_Guide_-_Full_Layout_-_DRAFT.pdf

[xxiv] New York City Office of the Deputy Mayor for Administration. (2022) The New Normal: Combatting Storm-Related Extreme Weather in New York City. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/orr/pdf/publications/WeatherReport.pdf

Zaveri, Mihir. (2021, September 14). 11 Deaths Put Focus on N.Y.C.’s Failure to Make Basement Apartments Safe. New York Times. 11 Deaths Put Focus on N.Y.C.’s Failure to Make Basement Apartments Safe – The New York Times (nytimes.com)

[xxv] New York City Office of the Deputy Mayor for Administration. (2022) The New Normal: Combatting Storm-Related Extreme Weather in New York City. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/orr/pdf/publications/WeatherReport.pdf

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] New York City Mayor’s Office. (2022). Housing Our Neighbors: A Blueprint for Housing and Homelessness. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/home/downloads/pdf/office-of-the-mayor/2022/Housing-Blueprint.pdf

[xxviii] New York City Mayor’s Office of Management and Budget. (2022). CDBG-DR Draft Action Plan for The Remnants of Hurricane Ida. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/cdbgdr/documents/nyc-hurricane-ida-action-plan-08-26-22.pdf

[xxix] Reisman, Nick. (2022, February 18). Hochul Scraps Accessory Dwelling Unit Plan. Spectrum Local News. https://spectrumlocalnews.com/nys/central-ny/ny-state-of-politics/2022/02/18/hochul-scraps-accessory-dwelling-unit-plan

[xxx] New York State Senate. (2022, May 10). Assembly Member Epstein and Senator Kavanagh Announce Bill Empowering New York City to Safely Legalize Existing Basement Apartments. https://www.nysenate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/brian-kavanagh/assembly-member-epstein-and-senator-kavanagh-announce-bill

[xxxi] Lange, Alexandra (2022, June 22). How the New York Loft Reclaimed Industrial Grit as Urban Luxury. Blomberg CityLab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-06-22/a-design-history-of-the-new-york-loft

[xxxii] The original loft law only covered buildings in Manhattan, but the law has been amended several times since to include additional areas in Brooklyn and to create new windows of eligibility in which tenants can apply to the Loft Board and ask for inclusion in the program. See a map of the building that the New York City Loft Board regulates here: https://nycbuildings.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=ee89bac48a7b4a15b897e124ce5b0c33

[xxxiii] Peck, Jamie. (2017, June 20) A People’s History of NYC’s Jeopardized Loft Law. Village Voice. https://www.villagevoice.com/2017/06/20/a-peoples-history-of-nycs-jeopardized-loft-law/

[xxxiv] New York City, N.Y. Local Law 49 of 2019 (uncodified).

[xxxv] Citizen’s Housing & Planning Council. (February 2020). Basements Almanac New Concepts & Technology For Improving the Safety and Habitability of Basement Apartments in New York City. https://chpcny.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/basementsalmanac.pdf

[xxxvi] Pratt Center for Community Development. (n.d.) Basement Apartments Safe for Everyone Campaign. https://prattcenter.net/our_work/basement_apartments_safe_for_everyone_base_campaign