Executive Summary

New York City is in the midst of a deepening youth mental health crisis. Nearly 40% of the city’s high school students report feeling persistently sad or hopeless—the highest rate in over a decade—and suicide remains one of the leading causes of death for adolescents. [1] For many young people, schools have become the frontline point of care. According to Advocates for Children, students are 21 times more likely to seek support for mental health issues at school than at a community-based clinic, and over 70% of students who successfully engage in treatment first initiated services in a school setting.[2] [3] But despite clear demand, New York City public schools are struggling to provide accessible, sustained mental health supports.

School-based mental health supports—ranging from counselors and Article 31 clinics to School Based Health Centers (SBHCs), community schools, and social worker-led counseling—remain fragmented and overstretched. Many of these programs operate through contracts with community-based providers constrained by limited staffing and reimbursement delays. As a result, students are frequently handed referral lists with little follow-up or wraparound care. The lack of a digitized, citywide system for tracking referrals and case notes further fragments the landscape, leaving students vulnerable to falling through the cracks. Financial challenges compound the problem, as delays in Medicaid reimbursement undermine the sustainability of school-based health clinics (SBHCs), and principals are often forced to make tradeoffs between hiring teachers, school counselors, or social workers due to budget limitations.

This report analyzes school-based mental health interventions and the gaps that persist, showing how fragmented funding, workforce shortages, and uneven access continue to limit the City’s ability to meet student needs. It outlines findings and recommendations to build a sustainable mental health system that ensures consistent staffing, expands integrated models like SBHCs, and establishes clear accountability for how mental health resources are funded and delivered across New York City public schools.

Key Findings

- New York City public schools are critically understaffed with mental health professionals, and many schools do not meet national recommended staff-to-student ratios.

- 71% of New York City schools do not meet minimum social worker staffing ratios of one social worker for every 250 students, as set by the National Association of Social Workers (NASW).

- 53% of New York City schools do not meet minimum guidance counselor staffing ratios of one counselor for every 250 students, as set by the American School Counselor Association (ASCA).

- The City is roughly 18% below the national standard for school psychologists. As of September 2025, the Department of Education (DOE) employs 1,543 school psychologists, but the lack of school-level data prevents calculating individual school ratios. Using the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) standard of one school psychologist per 500 students and an enrollment of approximately 884,000 students, New York City Public Schools’ systemwide average is approximately one psychologist per 574 students.

- To meet national standards, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that the DOE would need to hire 2,137 additional social workers and 1,220 guidance counselors, costing approximately $402–$426 million annually. While significant, this cost underscores the need for a phased, strategic approach that targets the highest-need schools first.

- A shortage of clinical and non-clinical mental health staff limits access to care in schools. DOE is limited in hiring “pupil personnel,” New York State Education Department (NYSED) identified titles a New York State certification category for specific school-based roles like school counselors, school psychologists, and school social workers, not including, certain licensed mental health professionals such as, Licensed Mental Health Counselors (LMHCs), Licensed Marriage and Family Therapists (LMFTs), Creative Arts Therapists, peers, and community health workers. These professions cannot be hired directly into school mental health roles unless they have a direct certification classified under pupil personnel, and can only work indirectly with schools through community based-organization (CBO) partnerships or school-linked programs. This structure limits the City’s ability to build multidisciplinary teams and prevents students from accessing the full spectrum of support they need.

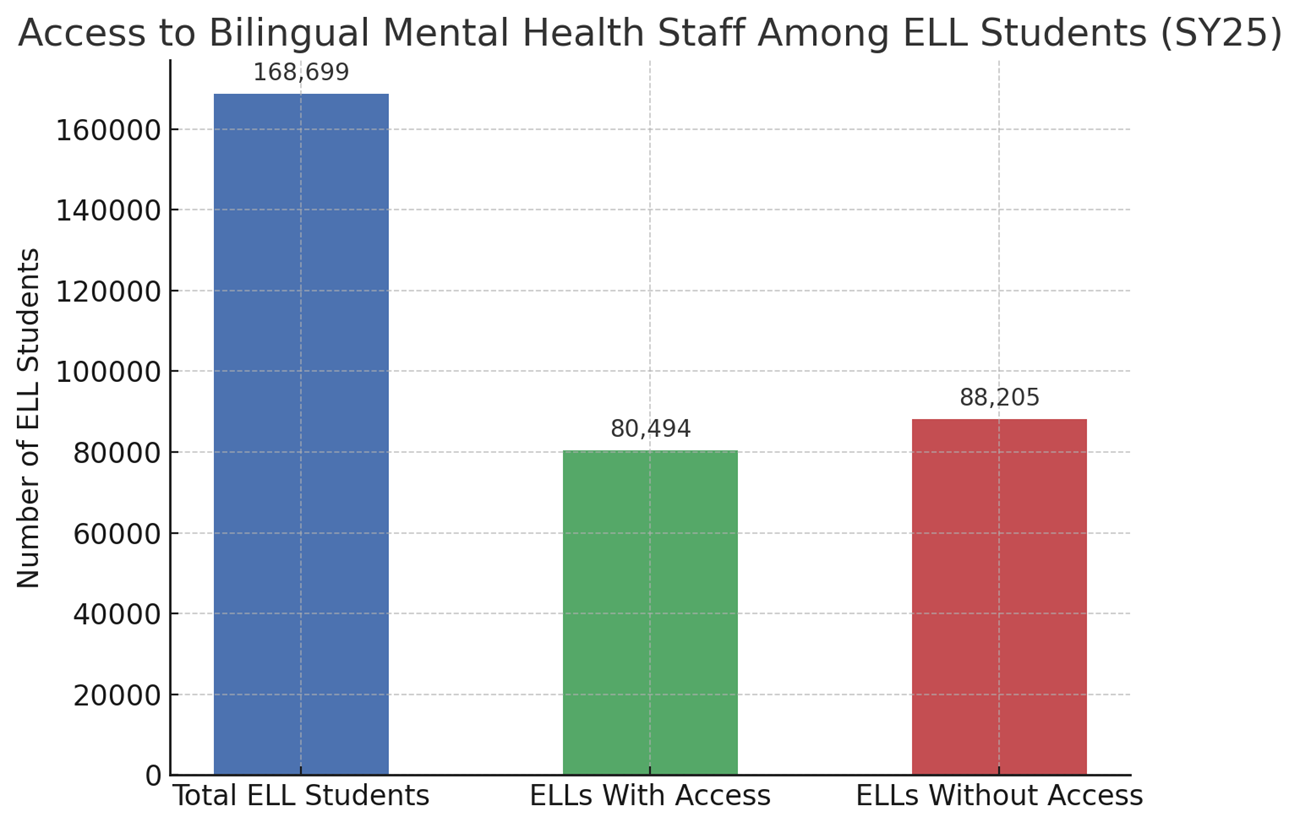

- There were more than 88,000 English Language Learners (ELLs) without access to bilingual mental health staff in the 2025 school year. In school year 2025, New York City public schools enrolled 168,699 English Language Learners (ELLs)—17.5% of all students—yet the system lacks the bilingual mental health staff needed to support them. That year, 1,375 schools had no bilingual guidance counselor, serving 111,259 ELLs, and 1,394 schools had no bilingual social worker, serving 120,264 ELLs. Even more concerning, 1,198 schools had neither, leaving 88,205 ELL students with no access at all to a bilingual mental health staff member.

- New York City Public School students and administrators identify School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs) as the best approach to support high schools with high student populations holistically and DOE students and administrators consistently identified SBHCs as the strongest model for supporting large high schools, noting that students need an on-site space—separate from school staff—where they can access mental health care privately and discreetly. Yet school leaders report that although they recognize the need for an SBHC, they do not know whom to contact or what process exists to request one, resulting in uneven access and ad hoc expansion.

- New York City’s School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs), and the City’s Mental Health Continuum, are underfunded, limiting access to care for high school students. School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs) are severely underfunded relative to the scale of student need. Today, 137 SBHC sites serve 325 schools and 150,680 students, yet the City’s 2025 November Plan includes just $8.2 million in FY 2026—and $8.6 million in the outyears—which the City Council notes supports only 35 centers, leaving the majority without any City funding. The Comptroller’s Office estimates that $20.2 million more is required just to support all currently operating SBHCs. An additional 75 campuses with high schools of 500 or more students—serving 125,697 students—lack any SBHC on site, and creating centers at these locations would require another $20.1 million. In total, fully funding existing SBHCs and expanding to high-population high schools would require $40.3 million, far exceeding current allocations. Meanwhile, the City’s School-Based Mental Health Clinics (SBMHCs) under the Mental Health Continuum face similar funding instability, operating with non-baselined $5 million in FY26 funding to support critical programming across 50 schools serving over 20,000 students. Advocates warn these clinics are already strained by staffing shortages and the lack of permanent funding threatens students’ continued access to reliable, integrated mental and behavioral health care in schools.

- Social-emotional learning (SEL) and advisory programs provide clinically proven mental health and academic benefits. SEL programs are supported by strong clinical and educational evidence. A 2023 Yale-led meta-analysis synthesizing more than 400 studies across 50 countries found that SEL instruction significantly improves academic achievement and critical mental health outcomes, including emotional regulation, self-efficacy, and optimism. School leaders interviewed by the Comptroller’s Office consistently highlighted advisory models—especially the New York City Outward Bound School’s “Crew” model, a small-group advisory structure where students meet regularly with a consistent adult advisor to build community, practice social-emotional skills, and receive academic and personal support—as reliable structures for consistently delivering SEL. A 2020 evaluation of the Crew model found chronic absenteeism rates of 5.3% in Crew-based schools compared to 11.4% in similar schools without Crew. Administrators, staff, and students interviewed by the Comptroller’s Office strongly endorsed the model for fostering trusted relationships, inclusive communities, and both academic and social-emotional growth. School leaders also emphasized that New York State’s “Portrait of a Graduate,” adopted in 2025, embeds social-emotional benchmarks into statewide expectations, offering schools a clear framework and opportunity to deepen SEL work through regular advisory programming.

- The Department of Education still has no centralized system to track mental health needs or services, leaving thousands of students invisible to the system.

Despite a 2022 NYS Comptroller recommendation and DOE’s plan to adopt the Partners Connect platform by 2025–26, advocates and administrators informed the Comptroller’s Office that no standardized, digitized mental health case-management system exists today. Instead, records are often handwritten, folded into incident reports in systems like the Online Occurrence Reporting System (OORS), or stored in local spreadsheets. Without a unified digital system, DOE cannot track whether students are connected to care, evaluate program effectiveness, or identify emerging needs. Digital case management is standard in health settings, but in DOE, referrals remain scattered across paper files, spreadsheets, and siloed programs—leaving vulnerable students at risk of falling through the cracks. - DOE’s current budget systems do not provide a clear accounting of how much the City spends on school mental health supports. DOE’s mental health spending data is so limited and fragmented that it is nearly impossible to determine how much the City actually invests in school-based supports. Funding is buried within broad budget lines and overlapping streams, and DOE has no system to track mental health expenditures across schools. Without reliable spending information, the City cannot plan for sustainable funding or ensure resources match student need.

Recommendations

To ensure all New York City students can access the mental health supports they need—and to reduce the long-term costs of unmet need escalating into crisis—the City must invest in a sustainable school-based mental health infrastructure. To accomplish this, the Department of Education should:

- Integrate mental health and social-emotional learning (SEL) into the school framework. The DOE should embed mental health into public schools by treating it as a core part of the school health system by integrating universal strengths-based mental health screenings into its existing student screening structure, beginning in elementary school. Modeled on Illinois’ statewide, first-of-its-kind program, these screenings would use standardized assessments, include opt out provisions and strong student privacy protections.[4] By folding these screenings into the same annual routines that identify vision, hearing, and dyslexia concerns, this approach would allow schools to spot emerging issues early and connect students to support before problems escalate.

At the same time, DOE should embed social emotional learning (SEL) and mental health literacy into advisory and homeroom curricula aligned with the State’s Portrait of a Graduate. Embedding SEL and help seeking skills into consistent advisory structures, such as Outward Bound’s “Crew” model, would ensure that students know how to ask for support and build trusted relationships with adults. Together, universal mental health screening and strengthened SEL would begin to create a proactive, schoolwide approach to mental health that catches needs early, builds trust, and makes mental health support a normal part of everyday school life.

- Establish a formal, cross-agency working group to create a financially realistic plan to move DOE toward national mental health staffing standards. Research consistently shows that every dollar invested in early mental health intervention yields $2 to $10 in long-term savings.[5] However, meeting these staffing ratios would require a significant investment—between $401.8 million and $425.5 million per year—and must be weighed against many competing priorities across the school system.[6] A coordinated working group led by DOE’s Office of School Health (OSH) and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH), with representation from school leaders, clinicians, the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), students, and community partners, would develop a phased, fiscally responsible roadmap that prioritizes the most urgent needs while moving the City toward national staffing standards.

- Adopt clear goals and a transparent process to stabilize and expand School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs) and baseline funding for the Mental Health Continuum so students have equitable access to integrated mental and behavioral health care. Stabilizing and fully funding the SBHCs that are already operating would cost the City an additional $20.2 million per year, based on the Community Health Care Association of New York State (CHCA) model ($100,000 per campus plus $100 per student). Bringing SBHCs to all large high schools citywide (500 or more students) would require the opening of 75 new centers, costing the City an estimated additional $20.1 million per year to support. The City should make these investments and pair them with a clear framework for SBHC growth, including a straightforward process for schools to request a center and annual surveys to assess need, capacity, and interest. Additionally, the City should baseline $5 million for the Mental Health Continuum—a partnership between NYC Health + Hospitals, DOE, and DOHMH—which funds several school-based mental health clinics (SBMHCs) plus essential programming like expedited student care, school staff consultations, crisis response, and mental health-related trainings.

- Expand access to Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) training for school faculty and students. The DOE should ensure that all educators and school staff are equipped to recognize and respond to mental health challenges through evidence-based MHFA training. Expanding MHFA training across DOE schools would ensure earlier intervention and stronger referral systems.

- Build intentional pipelines into the mental health workforce. The DOE should expand FutureReadyNYC and higher-education partnerships to create clear pathways from high school through mental health graduate training into mental health professions. Practicum opportunities for high schoolers as peer liaisons and expanded graduate placements would help address workforce shortages and spark long-term careers in the field.

- Diversify the school mental health workforce which should include a broader range of licensed and non-clinical professionals. While State certification rules[1] prevent the DOE from directly employing certain licensed mental health professionals, including Licensed Mental Health Counselors (LMHCs), Licensed Marriage and Family Therapists (LMFTs), Creative Arts Therapists, Licensed Master Social Workers (LMSWs), and peers, the agency has, in principle, far greater flexibility to bring these providers into schools through its contracts and vendor partnerships. In practice, however, current DOE contracting structures prevent schools from fully using this flexibility. Many of these qualified provider types are not consistently included as eligible vendors in DOE contracts, limiting schools’ ability to build multidisciplinary teams. The DOE should revise Request for Proposal (RFP) language and related contract templates so that schools can engage these providers through DOE-managed contracts. The DOE should also establish specialized contract pools or Multiple Task Award Contracts (MTACs) for diverse mental health providers, pre-qualifying vendors to streamline procurement and enable faster onboarding of varied professionals in schools. By expanding its contracting and hiring pipeline through these two changes, the DOE would help address workforce shortages, improve cultural responsiveness, and support a more flexible care model aligned with the City’s broader mental health goals.

- Expand linguistically and culturally responsive mental health services for English as a Second Language (ESL) students. The DOE should increase bilingual staffing, partner with community-based organizations serving immigrant youth, and ensure translation and interpretation capacity across all school-based counseling and health settings. Equitable access to care is essential to fostering trust, reducing disparities, and improving outcomes for multilingual learners.

- Implement a digitized case management system for student mental health.

DOE should expedite its planned collaboration with DOHMH to create a digitized system tracking referrals, services, and outcomes that protects student privacy. A digitized platform, supported by adequate training and staff capacity, would allow schools to track referrals, identify unmet needs, and ensure continuity of care, particularly for students with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) or those referred to external providers. - Establish transparent reporting systems to track and publish all mental health–related spending across the DOE. The DOE should collaborate with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and DOHMH to create a unified, public reporting framework that tracks contracts, programs, and staff positions related to mental health. This enhanced transparency would support equitable resource distribution and informed policymaking.

Background

The Youth Mental Health Crisis

Young people across the United States are experiencing a profound mental health crisis. One in five children in the United States between the ages of 3 and 17 has a mental health condition, yet only 20% of these children receive appropriate mental health services.[7][8] In 2023, nearly 1 in 10 students attempted suicide, and emergency room visits depression, anxiety, and behavioral difficulties rose by 28% between 2011 and 2015.[9] Suicide rates among youth ages 10 to 24 increased by 57% between 2007 and 2018, with over 6,600 deaths in this age range reported in 2020 alone.[10]

Understanding why youth are so vulnerable requires looking at the developmental period itself. Adolescence brings rapid social, emotional, and neurological changes, particularly in areas of the brain that regulate emotion, impulse control, and decision-making. Emotions feel more intense; peer relationships carry more weight; coping skills are still developing. At the same time, teens are forming identity, navigating independence, and managing academic and social pressures—often while experiencing discrimination, community violence, or family instability. Unsurprisingly, half of all lifetime mental health conditions emerge by age 14, and three-quarters by age 24.[11]

– New York City Public High School Student

These national health trends are mirrored—and in some cases intensified—in New York City. In 2023, nearly half (48%) of New York City teens surveyed experienced at least mild depressive symptoms, with up to 25% experiencing persistent anxiety. Disparities are stark: Black and Latinx students, as well as LGBTQIA+ youth and those facing food or housing instability, report higher rates of depressive symptoms, attempted suicide, and barriers to care. Suicide is now the second leading cause of death for teens ages 15–19 in the city.[12] [13]

Mental health challenges directly shape educational outcomes and long-term opportunity. Young people with untreated mental health conditions are more likely to face academic difficulties, increased substance use, involvement in violence, and risky behaviors. In New York City, these risks are compounded by Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), — such a family separation, domestic violence, parental substance misuse, or incarceration, which have lasting effects on brain development and emotional regulation. Nearly one in four children ages 5 to 13 in New York City have experienced three or more ACEs, dramatically increasing the likelihood of chronic mental health problems.[14]

One clear consequence of this crisis is chronic absenteeism. One in three New York City public school students was chronically absent last school year, often due to anxiety, depression, or trauma-related school avoidance. “School refusal,” is a form of emotionally based school avoidance (EBSA) in which a young person struggles to attend school because emotional distress makes the environment overwhelming. These absences reflect mental health needs, but without early intervention, they spiral into long-term disengagement.[15]

– New York City Public High School Student

A second major stressor is the way schools respond when a child is in crisis. Investigations by THE CITY and ProPublica show that schools continue to call NYPD School Safety Agents and police officers to manage students in distress an average of 3,200 times each year since 2017, despite a 2014 legal settlement that was supposed to limit 911 calls to only when a student poses an “imminent and substantial risk of serious injury” to themselves or others.[16] [17] Unless a parent arrives in time to intervene, police transfer students to EMTs, who bring them to emergency rooms for psychiatric evaluations, often without a full assessment or adequate follow up. Racial disparities are severe: Between Q1-Q3 in 2025, Black students accounted for 45% of all “child in crisis” incidents—nearly double their share of the public-school population and Hispanic students represented 41%. Black students also experienced the highest restraint rate (11%).[18]

In 2024, the Department of Education (DOE) updated Chancellor’s Regulation A-411 to require that every school establish a multidisciplinary Crisis Intervention Team comprised of a school administrator, counselors and/or social workers, teachers, a Substance Abuse Prevention and Intervention Specialist (SAPIS), the school nurse, and any available school-based mental health providers (such as Article 31 Clinic staff). This team must meet monthly, develop a Crisis Intervention Plan as part of the Consolidated School and Youth Development Plan, and engage in regular de-escalation training and professional development. However, despite the mandate, many schools lack sustainable funding and the necessary resources to hire enough staff for these teams, making it difficult to fully comply with the regulation’s requirements in practice.[19]

These capacity challenges were echoed in a 2022 audit conducted by the New York State Comptroller,[20] which found that many New York City public schools lacked adequate mental health staffing and had limited training for educators to recognize students in distress.

The audit also revealed that DOE had not ensured compliance with the state mandate for mental health instruction in health education and lacked systems to monitor program quality or effectiveness. A 2024 follow-up found progress on several corrective actions but reported that DOE still did not have a mechanism to monitor schools’ implementation of mental health curriculum.

Social Media Impact on Youth Mental Health

These challenges and gaps in school-based mental health supports are unfolding alongside another accelerating pressure on young people: social media. Data indicates a strong association between problematic social media use and worsening mental health outcomes for adolescents. A 2025 study found that 40% of depressed and suicidal youth receiving clinical care reported problematic social media use, characterized by distress when unable to access platforms, coupled with higher depressive symptoms and anxiety levels.[21] National surveys echo this pattern: roughly half of teenagers perceive social media as having a negative effect on peers’ mental health, and almost half report spending excessive time on these platforms, which contributes to anxiety, low self-esteem, isolation, cyberbullying, disrupted sleep, and exposure to harmful content.[22]

In response to these concerns, New York City filed a lawsuit in California Superior Court in February 2024 targeting five major social media companies—including TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, and YouTube — alleging that addictive design features and engagement-maximizing algorithms significantly contribute to the youth mental health crisis. The City sought damages and equitable relief to fund prevention and treatment, citing more than $100 million annually in related costs for schools and public hospitals. In October 2025, the City withdrew that complaint to refile[2] in New York and join multidistrict federal litigation.[23]

At the State level, Governor Kathy Hochul signed into law New York State’s “bell-to-bell” cell phone ban for all K-12 public schools as part of the FY2026 budget following youth listening sessions with students, educators, and families. Effective September 2025, the law requires students to keep devices turned off and securely stored throughout the entire school day—including lunch and passing periods. To support implementation, the State allocated $13.5 million for storage infrastructure, and New York City committed an additional $25 million to ensure schools can comply.[24]

Mental Health Services in NYC Public Schools

Over the past two decades, the City and State have made significant investments into youth mental health, building programs that span prevention, early intervention, crisis response, and access to care. Together, these initiatives reflect an evolving timeline of efforts to address the needs of young people across New York.

Citywide Initiatives

Schools are a critical touchpoint for mental health, serving as trusted community hubs where students spend much of their day and are most likely to access vital supports. In New York City, School Mental Health (SMH), established in 2005 as a joint initiative between the DOE and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH), was established to ensure every student could access high-quality mental health resources, supporting learning, resilience, and wellness. Guided by the Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) and the public health prevention model, SMH intends to deliver programming across three tiers: Tier 1 provides universal, schoolwide efforts to promote well-being and mental health literacy, Tier 2 offers small group supports for students at risk, and Tier 3 delivers individualized interventions for those with more intensive needs. DOE states on their website that each school and district is equipped with a framework for identifying, supporting, and referring students for further care and have access to the programming needed to support students.[25]

Launched in 2015, ThriveNYC was the de Blasio administration’s comprehensive mental health initiative, aimed at expanding access to care and embedding mental health support across agencies, schools, and neighborhoods. It delivered more than 30 programs, placing clinicians and social workers in over 240 schools, supporting clinics in 129 high-needs schools, training educators, and expanding services for runaway, homeless, and LGBTQ+ youth. ThriveNYC became one of the nation’s largest local mental health efforts, but faced criticism for unclear budgets and metrics. In 2021, it was restructured and rebranded as the Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health (OCMH).[26]

Mayor Eric Adams continued to elevate youth mental health a central priority through its Care, Community, Action mental health plan. In 2023, the administration launched NYC Teenspace, a free tele-mental health service for all New Yorkers ages 13 to 17, offered through a $25 million contract with Talkspace.[27] Since its launch, more than 21,000 teens have used the service. However, the program quickly drew criticism from advocates, including the New York Civil Liberties Union, the Parent Coalition for Student Privacy, and AI for Families, who raised concerns about online tracking on the Teenspace landing page. They warned that sensitive student data might be collected and stored by Talkspace. In response, the Health Department required Talkspace to remove all trackers and cookies and develop youth-specific privacy and intake protocols.[28]

The Adams Administration also expanded access to in-school clinical care. On March 17, 2025, Mayor Adams announced the opening of 16 new School-based Mental Health Clinics (SBMHCs) operated by H+H), building on five existing clinics from the Mental Health Continuum initiative and $700,000 in State OMH grants, these clinics—along with rapid-referral pathways into H+H outpatient services—now serve more than 20,000 students across 50 schools in the South Bronx and Central Brooklyn. SBMHCs are Article 31 clinics operated within schools that provide exclusively mental health services, such as individual, group, and family therapy; psychiatric evaluations and medication management; crisis intervention; case management; service coordination; and peer support. The City’s Mental Health Continuum supports clinics through H+H providing funding support, operational staffing, rapid-referral pathways to outpatient services, and facility space in ~50 high-need schools, though without baselined funding. However, the failure to baseline funding for the Continuum has left these programs financially unstable, undermining long-term planning, workforce retention, and sustained service delivery.[29]

School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs) in New York City, Article 28–licensed clinics within schools that deliver primary care, preventive services, reproductive health care, and mental health services to students, regardless of insurance status, are also facing significant budgeting concerns. SBHC providers warn that the State’s proposed Medicaid managed care “carve-in”—which would replace direct fee-for-service reimbursement with contracts across multiple private insurers—could destabilize the system by lowering reimbursement rates after the temporary hold, increasing administrative burden, risking clinics being deemed out-of-network, and triggering additional closures, particularly for hospital-sponsored sites already operating at thin margins.[30]

SBHCs have already faced closures. Between 2018-2023, H+H closed 19 SBHCs between 2018 and 2023, serving more than 13,700 students, and SUNY Downstate closed five clinics serving 10 schools in 2022 due to budget and operational strain.[31] While DOHMH formally began funding SBHCs in the early 1990s, New York City’s investment in school health access began earlier under Mayor Koch, who allocated $700,000 in City Tax Levy funds in the early 1980s to deploy public health nurses into high-need schools laying the groundwork for later SBHC integration. Mayor Dinkins expanded City funding for school health initiatives and under Mayor Bloomberg’s administration, capital funding expanded to modernize and develop school-based health infrastructure and strengthen reproductive health services. Mayor de Blasio continued this trajectory by providing funding support for school-based clinics through ThriveNYC funding.[32]

Finally, policymakers have also begun to strengthen peer-led supports. In January 2025 Council Member Linda Lee introduced Intro. 989-B,[33] requiring the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to toolkits that help middle and high school students establish student-led wellness clubs. Paired with DOE guidance on school implementation, the initiative aims to expand accessible, student-driven spaces for connection, community, and mental health support.

Importantly, in recent years, New York State has taken several steps to strengthen youth mental health, including a Medicaid settlement to expand intensive home- and community-based services, [34] new Youth Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams, and a statewide “phone-free schools” law. [35] These changes will shape the mental health landscape for many New York City students by increasing community capacity and shifting expectations around school climate and student wellbeing. However, the impact on students ultimately depends on how DOE integrates these changes into its current mental health infrastructure.

Together, these efforts show substantial activity across agencies—but they also reveal deep inconsistencies in implementation, unstable funding, and uneven access, underscoring the need for a more coordinated, accountable, and sustainable citywide school mental health strategy.

DOE Mental Health Workforce Shortages

Even as the City and State have expanded mental health programs in schools, the ability to deliver these services is consistently limited by a severe and persistent workforce shortage. Mental health staffing remains one of the most significant barriers to meeting students’ needs. Guidance counselors, social workers, school psychologists, and community-based clinicians each play distinct roles—academic and emotional support, crisis intervention, family engagement, assessment, and individualized treatment. However, staffing gaps stretch these professionals thin, reducing the quality of services and eroding students’ trust that help will be available when they need it.

According to the New York State Comptroller’s Office, the number of clients served by state-licensed mental health clinics increased by more than 50% between 2009 and 2021, while staffing grew by only 37.7%. As a result, the staff-to-client ratio dropped by 24.8%, from 10.5 full-time clinicians per 1,000 clients in 2009 to 7.9 in 2021. Workforce growth has largely occurred in the private sector—concentrated in practices that rarely accept insurance—while staffing in publicly funded settings continues to decline.[36] These dynamics have left publicly funded clinics, including Article 31 school-based clinics, struggling to recruit and retain licensed staff. The New York City Comptroller’s Agency Staffing Dashboard shows that vacancy rates in human services agencies remain elevated as of November FY 2026: approximately 9.2% at the Department of Social Services (DSS), 10.3% at the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), and 11.1% at DOHMH—all well above the citywide average of 5.8%.[37]

Nonprofit providers – many of which operate or staff schools-based mental health clinics – are similarly experiencing acute workforce shortages. According to a 2024 report by the Center for an Urban Future, human service nonprofits in New York City reported an average vacancy rate of 15.6%, with many indicating 30%–45% vacancies for clinical and client-facing positions such as case managers, peer navigators, and crisis counselors. These nonprofit providers, often contracted to operate or supplement school-based mental health clinics, struggle to fill positions due to low wages, weaker benefits, and mandatory in-person work requirements.[38]

These layered shortages—across schools, City agencies, and nonprofit partners—underscore that expanding mental health access will require not only new programs but a coordinated strategy to grow, support, and stabilize the behavioral health workforce.

Methodology

To assess the current school mental health landscape and the supports available to New York City public school students, the Comptroller’s Office used a mixed-methods approach that included qualitative interviews and roundtables, site visits to public schools, detailed analyses of DOE and Office of Payroll Administration and Financial Information Services Agency (OPA/FISA) datasets, reviews of public School Allocation Memorandums (SAMs), and relevant New York State Comptroller audits.

To assess compliance with national best practices for mental health staffing, the Office calculated per-school ratios for guidance counselors and social workers using DOE-reported staffing counts and final audited enrollment data for School Year (SY) 2024–2025. Because DOE does not publicly report school psychologist data, figures for psychologists were derived from FISA payroll data under the titles CLSPQ and E0763. Schools excluded from the ratio analysis included D75, D79, LYFE, Alternative Learning Centers, and Pre-K Centers. Estimated costs were generated using UFT salary schedules for title School Counselor and School Social Worker for September 2025, accounting for fringe, in comparison to the analysis of staff needed to meet recommended ratios.

For the analysis of bilingual staffing, the Office cross-referenced DOE’s guidance counselor and social worker staffing report with the NYC DOE’s Demographic Snapshot from 2024-2025 to identify the number of English Language Learners (ELLs) attending schools with and without bilingual mental health staff.

To generate cost estimates for SBHC funding needs, the Office utilized the funding methodology recommendation from the Community Health Care Association (CHCA). DOE’s 2025–2026 list of SBHCs provided the number of currently operating SBHCs, and DOE enrollment files as well as the Demographic Snapshot were used to estimate student access to SBHCs and associated funding needs for support. These enrollments include K-12 and Charter schools but exclude D79 and D75 due to differences in funding, support, and enrollment data availability for those programs. To estimate the City funding needed to open new SBHCs, the Office used current school location data in the Location Code Generation and Management System (LCGMS) to identify school campuses where large high schools had no access to SBHC services. The Comptroller’s Office identified large high schools as schools with 500 or more students, and limited analysis to standalone high schools (excluding secondary schools and K-12 schools). That data was matched to the enrollment files referenced previously to estimate the number of students these new centers would support.

Where DOE data was incomplete or unavailable, the Office used OPA/FISA position titles, prior audit findings, and publicly available datasets to construct reasonable estimates. Because DOE does not maintain a centralized case management or service-tracking system, it was not possible to determine the number of students who received or were awaiting school-based mental health services, nor to calculate total DOE spending on student mental health.

Overview: Funding for Mental Health Services in Schools

Current data on mental health spending within DOE is severely limited, fragmented, and inconsistently categorized, making it extraordinarily difficult to determine how much the City invests in school-based mental health supports. Funding for mental health is often embedded within broad budget structures or distributed through overlapping streams, and DOE does not maintain a system capable of tracking mental health expenditures across schools. As a result, producing a precise estimate of total City spending is not possible.

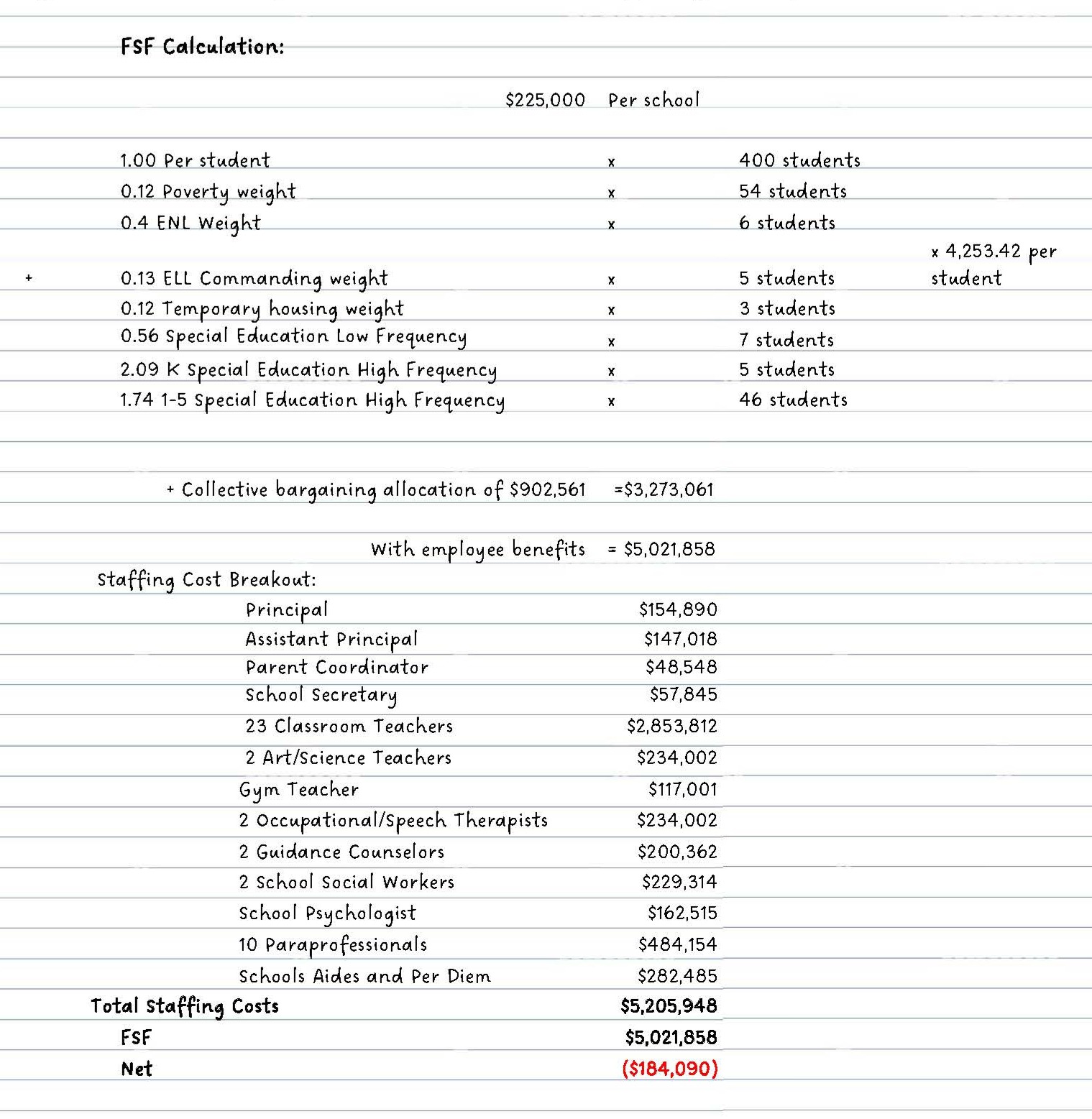

This report instead draws on the best available data—combining budget records, staffing files, School Allocation Memorandums, and qualitative insights from school leaders—to provide a clearer picture of funding streams and constraints affecting mental health supports in public schools. Fair Student Funding (FSF) is the largest and most flexible pot of funding in most school budgets and the primary source of staffing funding available to principals. According to the school leaders interviewed for this report, a substantial portion of funding used to hire mental health staff—including social workers, counselors, and related providers—comes from FSF. FSF is a weighted funding formula implemented across all traditional public schools in the city; it allocates resources according to the number of enrolled students and adjusts for specific needs—including grade level, special education status, English language learner status, academic intervention, and other needs—by applying extra funding “weights” to students likely to require more resources. Each school first receives a base allocation, then per-pupil amounts determined by these weights, which are intended to reflect the higher costs of supporting students with greater needs.

A prominent theme in interviews conducted for this report is that the FSF formula does not fully cover the costs of mandated Individualized Education Program (IEP) services, which often specify mental health supports and staffing that schools must provide including school-based counseling, psychological services, or social skills interventions. These services are essential to ensuring students with disabilities receive a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment, as required under federal and state law[3]. Yet the Comptroller’s 2023 Course Correction report found that many students with IEPs do not receive all of their mandated supports, with the deepest gaps in predominantly Black, Hispanic, and high-poverty districts. [39]

School leaders described stretching limited FSF dollars to meet both legally mandated IEP staffing and rising student mental-health needs. Many said they must make difficult hiring choices because the real cost of mandated services exceeds what the funding formula provides. As a result, schools often fall short of delivering required supports, leaving vulnerable students waiting for—or going without—critical services, which undermines academic progress and widens existing mental-health inequities.

Figure 1: Elementary School FSF and Staff Budgeting Example

Mental health supports are also funded through specific School Allocation Memorandums (SAMs) – annual, targeted funding streams that supplement FSF and help schools hire staff or advance key initiatives.

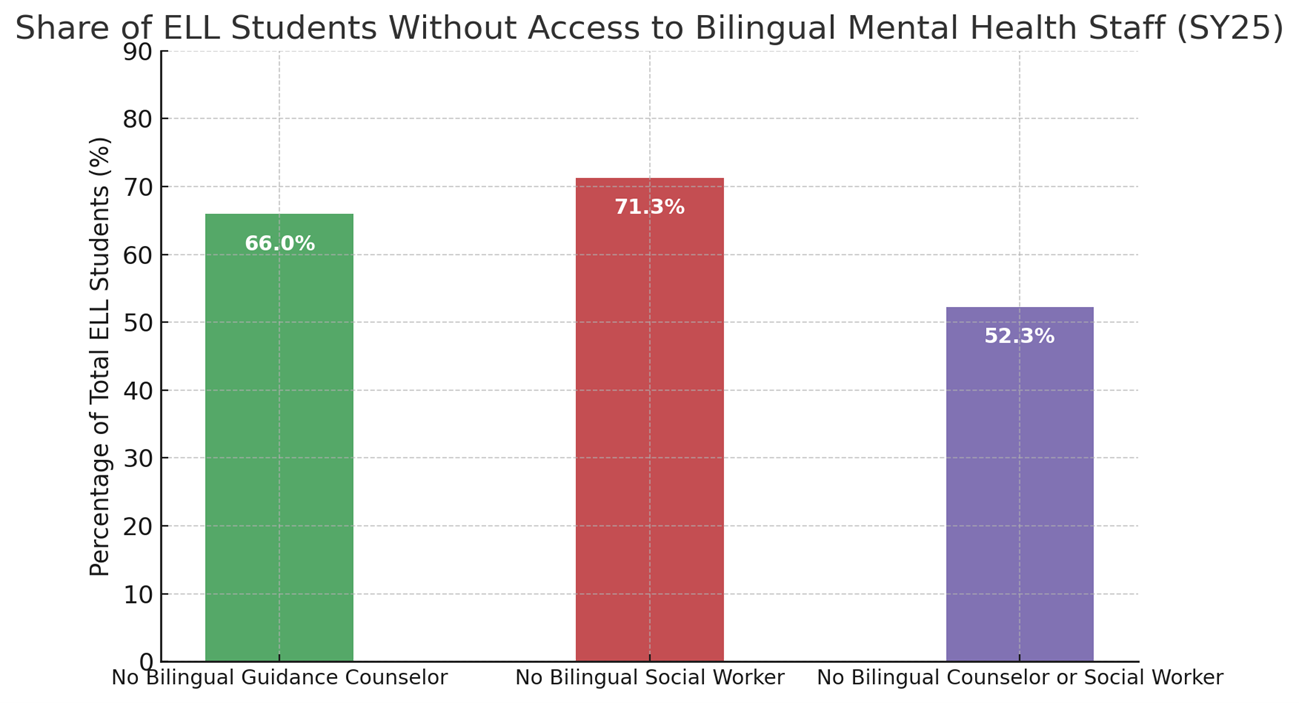

In the City’s Fiscal Year (FY) 2025, there were three SAMs dedicated specifically to mental health funding: SAM 40 Counseling Initiatives, SAM 62 Mental Health Continuum, and SAM 47 Psychologist-in-Training Allocation. SAM 40 is the largest, distributing $100.2 million in tax-levy funding to schools in FY 2025. SAM 47 distributed $2.1 million for one-year salaried internships for monolingual and bilingual school psychologists for hard-to-staff districts. SAM 62 distributed $639,459 in FY 2025 to support the Mental Health Continuum, a DOE–H+H–DOHMH partnership that builds school-based capacity and provides culturally responsive, family-centered care. Across the 1,519 schools in the analysis, larger schools received less SAM mental health funding per student, widening disparities in per-capita resources, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Mental Health Funding Per Student through SAMs, FY 2025 By School Enrollment Size

Source: NYC Department of Education, Office of the New York City Comptroller

Key Findings

New York City public schools face a critical shortage of mental health professional staff due to inadequate funding, and many schools do not meet national recommended staff-to-student ratios.

– New York City Public High School Student

School administrators report that they struggle to afford mental health services—including some mandated under IEPs—and often face significant constraints when trying to hire more mental health staff or expand supports. National best practices set clear ratios for mental health staffing at schools: one guidance counselor per 250 students,[40] one social worker per 250,[41] and one school psychologist per 500[42] depending on need. The DOE reports directly on the total number of Guidance Counselors and Social Workers in schools, seen in Figure 3 for the SY24-25 school year:

Figure 3. Total Number of Guidance Counselors and Social Workers, SY24-25

| Title | Total | Full-time | Part-time |

| Guidance Counselor | 3,222 | 3,193 | 29 |

| Social Worker | 2,013 | 2,005 | 8 |

| Total | 5,235 | 5,198 | 36 |

Source: New York City Department of Education[43]

Note: Totals are inclusive of guidance counselors and social workers in the Absent Teacher Reserve, Schools Response Clinicians, High Needs SWs, Bridging the Gap SWs, High Needs, GC, and Single Shepherds. Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

DOE provides Guidance Counselor and Social Worker staffing data by school, making it possible to compute per-school staffing ratios for the general school population. These ratios were calculated for K-12 general education schools, excluding D75, D79, LYFE, Alternative Learning Centers and Pre-K Centers. In the sampled 1,519 remaining schools, there were 2,998 Guidance Counselors and 1,818 Social Workers in SY24-25. Ratios of students to staff were created based on the final audited enrollments of SY24-25, as provided by the DOE.

The table below shows the number and percentage of the 1,519 sampled schools meeting the 1:250 ratio for guidance counselors and social workers in SY24-25.

Figure 4. School Mental Health Staffing Ratios, SY24-25

| Staff Title Category | Schools Meeting 1:250 Ratio | % Meeting Ratio | Schools Not Meeting 1:250 Ratio | % Not Meeting Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Workers | 447 | 29% | 1,072 | 71% |

| Guidance Counselors | 711 | 47% | 808 | 53% |

Source: Department of Education, Office of the New York City Comptroller

Most schools do not meet the mandated ratios for either social workers or guidance counselors. In addition to the 1,072 schools not meeting the 1:250 ratios for social workers and 808 schools not meeting the 1:250 ratio for guidance counselors, 657 schools are not meeting the recommended ratio for both guidance counselors and social workers. There are 106 schools with 0 guidance counselors and 186 with 0 social workers, although only 2 schools have neither a guidance counselor nor a social worker.

– New York City High School Student

The distribution of schools with no guidance counselors is skewed heavily towards younger grades. There are only 11 high schools with 0 guidance counselors, compared to 83 elementary schools. The distribution is less skewed for social workers, where 60 elementary schools have 0 social workers compared to 49 high schools.

The DOE does not report on School Psychologists, so the Comptroller’s Office used the OPA/FISA system to find the number of positions budgeted under that title (codes CLSPQ and E0763). FISA shows the DOE has 1,543 school psychologists as of September 2025. However, there is no way to tie the School Psychologist staffing data back to specific schools to compute if the recommended staffing ratio of students to psychologists is being met, due to lack of available aggregated DOE data. In a 2022 audit by the State Comptroller of mental health services in schools, that office was also unable to compute the school psychologist ratios due to lack of publicly available data. When OSC requested this data from the DOE they found that “each of its 1,524 schools has access to a school psychologist, […] However, a school psychologist was not always on-site full time at every school; their availability ranged from 1 to 4 days per school week.”[44]

Interviews with school leaders revealed significant funding challenges that limit their ability to expand mental health supports. Principals reported being forced to choose not only which staff positions they could afford with limited funds, but also how to balance these decisions against urgent infrastructure and safety needs. One administrator described having to prioritize repairs and construction updates on an aging school building, even though they would have preferred to invest in student resources and expand access to mental health care on campus. Leaders also shared that they are increasingly receiving students entering high school with IEPs who had not received their mandated supports in earlier grades, compounding academic and emotional needs in schools with limited resources.

According to City Human Resource Management System (CHRMS) data, as of the end of September 2025, the DOE employed a total of 2,427 School Social Workers, 3,376 Guidance Counselors, and 1,574 School Psychologists, seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5. September 2025 DOE Mental Health Staffing and Annual Cost

| Title Category | # of Staff | Annual Cost (Salaries and Fringe) |

|---|---|---|

| Social Workers | 2,427 | $417,129,604 |

| Guidance Counselors | 3,376 | $595,052,815 |

| School Psychologists | 1,574 | $284,668,568 |

| Total | 7,377 | $1,296,850,986 |

Source: FISA/OPA Payroll data; City Human Resource Management System (CHRMS), September 2025

Note: The number of staff counted through FISA reporting is slightly different from the year-end FY 2025 numbers provided by the DOE, both because it is at a different point in time and comes from a different source. Fringe was calculated using the UFT rate of 52%.

The Comptroller’s Office projects that the DOE would need to hire 2,137 Social Workers and 1,220 Guidance Counselors to sufficiently staff schools to meet the recommended 1:250 ratio for social workers and guidance counselors at the 1,519 schools sampled as seen in Figure 4. The school needs range from 1-5 additional guidance counselors needed per school, and from 1-17 additional social workers needed per school.

Figure 6. Mental Health Staffing Resources Needed to Meet Recommendations

| Title | Number of Staff Needed | Low Estimate | High Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Workers | 2,137 | $264,104,650 | $271,715,276 |

| Guidance Counselors | 1,220 | $137,715,162 | $153,811,354 |

| Total | 3,357 | $401,819,811 | $425,526,630 |

Source: Office of the New York City Comptroller

Note: To calculate the cost of hiring additional staff, the Comptroller’s Office took a low and high salary from the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) staff schedules for entry-level staff, based on qualifications, as of September 2025. Entry-level Social Workers range from a low salary of $81,307 to high of $83,650, and Guidance Counselors from $74,264 to $82,944. The Office then added in the UFT fringe benefits rate of 52% and multiplied by the projected staff need to land on the following cost estimates.

A shortage of school-based mental health professionals—both clinical and non-clinical —prevents students from accessing care.

Interviews with students revealed that many cannot access timely school-based mental health services due to waitlists, understaffed clinics, or counselors managing unmanageable caseloads. For many, the demand for services far outpaces the number of available staff, resulting in delayed interventions, shorter sessions, or referrals outside the school system—often with limited follow-up or continuity of care. Students also reported that these persistent access challenges have eroded their trust in school-based mental health professionals and guidance counselors, noting that existing staff are too overextended to provide support tailored to their needs.

– New York City Public High School Student

School administrators expressed a need for more diverse clinical and non-clinical mental health staff for schools, but reported lacking the necessary funding to hire them. Administrators and advocates also emphasized that available funding streams are extremely limited in the types of mental health staff they can support, and even in schools that have mental health–related roles, these positions often cannot provide direct clinical services.

Across New York City, the behavioral health workforce in schools remains concentrated in a small number of professions—primarily master’s-level social workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists. Although the number of professionals across these disciplines has grown in recent years, the rate of growth has not kept pace with rising demand for services.[45] These roles are essential, but they represent only part of a broader ecosystem that includes Licensed Mental Health Counselors (LMHCs), Licensed Marriage and Family Therapists (LMFTs), Addiction Counselors, Creative Arts Therapists, Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioners, Occupational Therapists (OTs), and bachelor’s-level Social Workers (BSWs). Non-clinical providers like Peer Specialists, Peer Support Workers, and Community Health Workers (CHWs) also bring valuable expertise in engagement, lived experience, and continuity of care.

However, New York State Education Department (NYSED) certification requirements and NYC Department of Education (DOE) hiring practices prioritize “pupil personnel” titles, such as School Social Worker, School Psychologist, and School Counselor, for direct DOE employment in core mental health roles. Even though outside mental health professionals can bill Medicaid directly in private practice, Article 28/31 clinics, or managed care plans, they cannot fill DOE pupil personnel positions without additional NYSED school certification. This alignment with Medicaid school-based billing rules and IEP team staffing mandates means the primary pathway for LMHCs, LMFTs, OTs, peers, and other non-certified professionals to serve students onsite is through community-based organization (CBO) partnerships, OMH- or DOHMH-funded school-linked programs (like SBHCs and SBMHCs), and pilot initiatives—not direct DOE hiring. Thus, while these professionals are not categorically excluded from schools, DOE’s current infrastructure limits their integration into core school-based mental health teams in favor of state-certified roles.[46] [47] [48] [49] As a result, schools and clinics often rely on a narrow set of providers to respond to a wide range of student needs. This limits the ability to form multidisciplinary teams, where varied skill sets can be applied to prevention, treatment, and follow-up.

Social-emotional learning (SEL) and Advisory Programs Provide Clinically Proven Mental Health and Academic Benefits.

SEL programs are backed by strong clinical and educational evidence demonstrating their vital role in supporting students’ mental health and overall well-being. A comprehensive 2023 meta-analysis[50] led by Yale researchers synthesized results from over 400 experimental studies involving more than half a million K-12 students across 50 countries. The study found that SEL instruction significantly improves not only academic achievement but also critical mental health outcomes. Clinically, SEL programs enhance students’ emotional regulation, self-efficacy, and optimism, which are foundational skills for coping with stress, anxiety, and depression. Students participating in SEL reported reduced levels of anxiety, stress, depression, and suicidal ideation compared to peers without such instruction. They also experienced stronger feelings of connection, inclusion, and improved relationships with teachers and peers, which are factors clinically linked to resilience and psychological well-being.[51]

Researchers emphasize that emotional regulation skills gained through SEL—such as mindfulness, anger management, goal setting, and positive self-talk—are crucial for creating a mental state receptive to learning and growth. When students feel emotionally regulated and safe, they are better able to focus, retain information, and engage academically.

School leaders highlighted advisory models—especially the Outward Bound “Crew” model—as reliable structures for consistently delivering SEL outcomes. Students typically remain in the same Crew group throughout their entire school tenure, providing a stable community where trust and supportive relationships deepen over time. Administrators noted that this continuity encourages honest reflection, help-seeking, and the development of both academic and social-emotional skills.

The Crew model brings small groups of grade-level peers together several times each week to build academic and social-emotional skills through team building, conflict resolution, and self-reflection. A 2020 evaluation of the NYC Outward Bound Crew model by Metis Associates found that Crew participation led to significant reductions in chronic absenteeism: .3% in Crew-based schools compared to 11.4% in similar schools without Crew. Administrators, staff, and students strongly endorsed the model, crediting Crew with creating trusted relationships, fostering inclusive communities, and providing both academic and moral support. Nearly four in five students reported that their Crew leader cared about them, and educators highlighted the model’s value in supporting SEL, academic growth, and connections between families and schools over the course of a student’s middle or high school years.[52]

School leaders also emphasized that New York State’s “Portrait of a Graduate”[53] framework presents a key opportunity to integrate SEL into everyday school life, and that regular advisory programs, such as the Crew model, are the most practical and effective means for doing so. Adopted by the Board of Regents in July 2025, the framework defines the core skills, mindsets, and competencies that every student should develop by graduation. Because social-emotional benchmarks are embedded within these statewide standards, schools have a clear incentive and roadmap for deepening SEL work through advisory programming.

NYC Public School students and administrators identify School-Based Health Centers as the best approach to support high schools with large student populations holistically and discreetly.

School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs) are medical health centers operated by local hospitals, medical centers, and community organizations located inside school buildings. Overseen by the New York State Department of Health (DOH) and DOHMH, SBHCs typically include a team of healthcare professionals such as physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, mental health professionals, social workers, medical assistants, and health educators.

SBHCs provide medical care to students regardless of insurance or immigration status. While SBHCs bill Medicaid and private insurance when possible, families are not responsible for any out-of-pocket costs. According to this report’s analysis of the DOE’s NYC School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs) 2025–2026 file [54], 137 SBHCs currently serve 325 K-12 and charter schools, with many centers supporting multiple co-located schools. The highest concentration of SBHCs is in the Bronx.[55]

Interviews reveal that comprehensive high schools, which serve large student populations, face chronic shortages of mental health supports and services. Stakeholders—including advocates, school leaders, and students—emphasized the need for private, safe spaces where young people can seek care discreetly. All students interviewed reported fear that teachers, guidance counselors, or administrators might disclose sensitive information to their parents or guardians, deterring them from seeking help.

– New York City Public High School Student

Interviewees identified SBHCs as a holistic model of care by embedding medical, mental health, and preventive services directly into schools. According to the New York School-Based Health Foundation, 26% of all student visits to Data Hub SBHCs were for behavioral health services. During the 2023–24 school year alone, 12,922 students made 68,816 behavioral health care visits to SBHCs; 57% of these students were female and 43% male.[56]

– New York City Public High School Student

New York City SBHCs, and the City’s Mental Health Continuum, are underfunded, leading to staffing and programming constraints.

SBHCs bill health insurers for services provided when students have coverage, but they may not be able to receive reimbursement for all services. For example, preventive services including health education or other counseling services may not be reimbursed, and other services may require prior authorization from a student’s managed care plan. Limited Medicaid reimbursement and a patchwork of funding sources create significant financial challenges for these clinics. According to Children’s Aid Society, operator of 6 SBHCs in the City, insurance billing covers only about half of operational costs, and State grants have been cut by $5.8 million since 2013.[57]

The City’s 2025 November Plan included $8.2 million in FY 2026 funding for SBHCs, and $8.6 million baselined in the outyears of the City’s budget. According to the City Council, the City’s funding goes to support 35 SBHCs currently operating in New York City public schools, with other SBHCs not receiving any City funding.[58] The Community Health Care Association (CHCA), representing SBHCs in New York, has called for the City to support all SBHC clinics by implementing a funding model that includes a baseline of $100,000 per school campus, plus $100 for each student enrolled.[59] This support would bring all SBHCs to a level of consistent funding similar to the few centers currently contracted with DOHMH, which receive a fixed annual base award of $100,000 per site plus a unit rate per student enrolled in the school. If applied similarly to the DOHMH funding methodology, this funding could support either personnel services (PS) or Other-than-Personnel Services (OTPS) to supplement state grant funding and insurance billing reimbursement.

Analyzing the DOE’s public list of the 137 SBHCs operating in the current school year, the Comptroller’s Office estimates that 150,680 students are being served at the 325 public and charter K-12 schools operating at those 137 locations.[4] (Many clinics serve two or more co-located schools, although this research excluded D75 and D79 schools from estimates.) Using DOE figures and CHCA’s recommended funding model, the Comptroller estimates that an additional $20.2 million in City funding would be needed to support currently operating SBHCs.

Figure 7. Funding Current Public School-Based Health Centers

| Total Centers Open | 137 |

| Students Enrolled on Participating Campus | 150,680 |

| Baseline $100K Per Campus | $ 13,700,000 |

| $100 per Student Enrolled | $ 15,068,000 |

| Total Recommended | $ 28,768,000 |

| Baselined City Funding | $ 8,551,453 |

| Remaining Need | $ 20,216,547 |

Interviews reveal that comprehensive high schools, which serve large student populations, face chronic shortages of mental health supports and services. Comparing the list of SBHC locations and school location data from LCGMS[60], there are currently 75 school campus locations without an SBHC on site that include a high school serving 500 or more students. The 108 schools on those campuses currently serve 125,697 students. As shown in Figure 7, operating centers at these 75 locations would require an estimated additional $20.1 million in City funding (utilizing the same CHCA recommended funding model), with additional funding needed for any space leasing or renovations.

Figure 8. Costs of Supporting New SBHCs at High Schools with more than 500 Students

| New School-Based Health Centers | 75 |

| Students Enrolled on Campuses | 125,697 |

| Baseline $100K Per Campus | $7,500,000 |

| $100 per Student Enrolled | $12,569,700 |

| Estimate for New Centers | $20,069,700 |

| Recommended Support for Currently Open Centers | $20,216,547 |

| Combined Cost For New and Existing SBHCs | $40,286, 247 |

Note: This estimate does not include the increase that would be necessary in State funding for SBHCs and assumes that all schools could provide space for a clinic without capital expansion.

In addition to SBHCs, the City’s School-Based Mental Health Clinics (SBMHCs) under the Mental Health Continuum face significant funding instability. According to advocates like Advocates for Children, CCCNY, and Dignity in Schools, these clinics rely on Continuum funding to sustain core programming—including expedited care, staff consultations, crisis response, and family engagement—across 50 schools serving 20,000+ students in the South Bronx and Central Brooklyn, yet the program operates without baselined support. Although the FY26 Executive Budget restored $5 million, following Council calls to baseline it, this allocation funds only one year, leaving clinics at risk of staffing shortages, service cuts, and inability to expand. A March 2025 Chalkbeat report highlights that due to the lack of permanent, stable funding, SBMHCs have already experienced strain, including an 18% vacancy rate among social workers as of late 2024. Advocates and officials warn that this funding uncertainty complicates long-term planning and threatens students’ access to consistent, integrated mental and behavioral health care in schools.

English Language Learners (ELLs) Face Stark Barriers to School-Based Mental Health Care.

Access to school mental health services is even more limited for English-language learners (ELLs), despite rising enrollment and heightened immigration-related stress. Immigrant and ELL students may carry trauma, face immigration-related stress, or struggle with a shortage of bilingual clinicians and English as a second language (ESL) teachers. Interviews revealed a broad consensus that schools cannot recruit enough qualified bilingual teachers, leading many to improperly seek waivers for less common languages—affecting thousands of students.

A recent audit by New York City Comptroller Brad Lander found significant failures in the City’s responsibility to educate ELL students. Nearly half (48%) of reviewed student records showed ELL students were not enrolled in required English as a New Language (ENL) or bilingual courses, nor provided sufficient instructional time as mandated by state regulations. About 40% were taught by teachers without proper ENL or bilingual certification. These deficits in support for ELLs extend directly into mental health services.

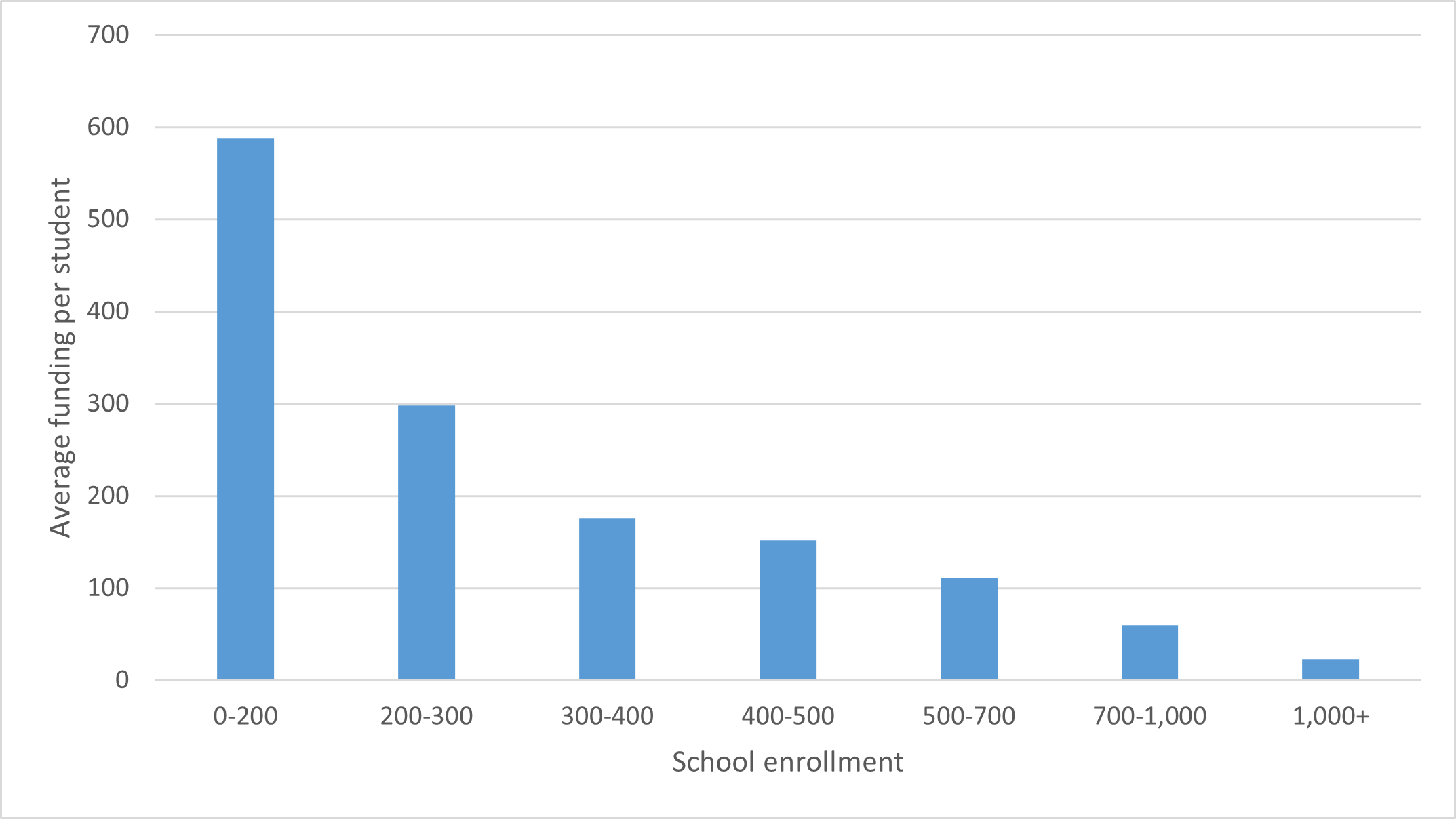

In SY25, there were 168,699 ELLs citywide (17.5% of total enrollment), but only 286 bilingual guidance counselors and 217 bilingual social workers across all schools., as seen in Figures 9 and 10.

- 1,375 schools had no bilingual guidance counselor, despite enrolling 111,259 ELLs.

- 1,394 schools serving 120,264 ELLs had no bilingual social worker.

- 1,198 schools had neither, leaving 88,205 ELLs without access to a bilingual mental health (MH) staff member.

One of the most concerning examples is Fort Hamilton High School in Brooklyn, which enrolled 740 ELL students in SY25 but had no bilingual social worker or guidance counselor.

Figure 9: Share of ELL Students Without Access to Bilingual MH Staff (SY25)

Figure 10: Access to Bilingual MH Staff Among ELL Students (SY25)

Interviews with school leaders underscored how immigration-enforcement related stress drives mental health need. Students from immigrant families face unique stressors including fear of deportation, discrimination, language barriers, and trauma from family separation, all of which increase vulnerability to mental health challenges and complicate access to care in schools.

The constant threat of deportation and detainment weigh heavily on some students’ lives:

- In June 2025, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detained an 11th-grade NYC public school student during a routine asylum hearing.[61]

- In August 2025, a 7-year-old student, her 17-year-old brother, and their mother were detained following an immigration check-in.[62]

- As of early October 2025, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has escalated enforcement actions targeting immigrant youth; according to a Department of Health and Human Services memo obtained by NBC News, ICE has begun offering unaccompanied migrant children aged 14 and older $2,500 to “self-deport.”.[63]

School leaders also reported trafficking risks for migrant students but said they lacked the staffing and resources to intervene. These dangers are real and documented: in October 2025, a Queens Village man was indicted for labor trafficking and grand larceny after allegedly stealing nearly $20,000 from a Bangladeshi student who was on a visa, imprisoning him, forcing him to do unpaid household work under threat of deportation, and denying him access to education while restricting his movement.[64]

Despite these mounting pressures, schools do not have the bilingual, culturally responsive mental health staff needed to support ELL students.

There is no formal digitized case management system for tracking students who have interacted with or need school mental health services.

An August 2022 audit by the New York State Comptroller found that DOE does not maintain a centralized data system for collecting and analyzing student mental health information in order to aggregate, document, and analyze mental health-related data such as referrals, services, and program outcomes. The audit recommended that DOE develop such a system, noting that without it DOE cannot assess program effectiveness, identify emerging needs, or ensure services reach students as intended.

In a May 2024 follow-up, DOE officials shared plans to collaborate with the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to use its “Partners Connect” data system, which will collect, document, and analyze mental health-related information for public school students. DOE had indicated this system would be active in the 2024–25 school year. However, school leaders interviewed for this report indicate that no formal digitized system has been implemented to track which students have received–or need–mental health services.

Administrators, school staff and advocates report that records, if kept, are written physically and indicate a need for a digitized system, with appropriate staffing, to provide effective mental health case management for students seeking services. Without such infrastructure, students are often left to seek support on their own in the community, where long waitlists are common. This failure is particularly harmful because individuals in crisis require immediate care and intervention. The absence of a coordinated system limits schools’ ability to ensure that students are connected to appropriate services, that these services are consistent and that provers have up to date information on a student’s needs, undermining continuity of care and leaving vulnerable young people at risk.

School leaders emphasized that while the creation of such systems is essential, its success will depend on adequate staffing, comprehensive training, and sustained support. Until a coordinated approach is established, schools remain limited in their ability to guarantee timely, appropriate care for students.

Recommendations

To ensure all New York City students can access the mental health supports they need—and to reduce the long-term costs of unmet need escalating into crisis—the City must invest in a sustainable school-based mental health infrastructure. To accomplish this, the DOE should:

- Integrate mental health and social-emotional learning (SEL) into the school framework. The DOE should embed mental health into public schools by treating it as a core part of the school health system by integrating universal, strengths-based mental health screenings into its existing student screening structure, beginning in elementary school. Modeled on Illinois’ statewide, first-of-its-kind program, these screenings would use standardized assessments, include opt out provisions and strong student privacy protections.[65] Illinois’ universal mental health screenings law makes annual mental health screening available at no cost to students in grades 3–12, sets expectations for tools and follow‑up, and includes strong provisions for parental notification and student confidentiality. By folding these screenings into the same annual routines that identify vision, hearing, and dyslexia concerns, this approach would allow schools to spot emerging issues early and connect students to support before problems to escalate.

Positive screens would be followed by a tiered response: classroom and small group SEL strategies, and warm handoffs to mental health professionals or school-based health center clinicians for students with greater needs.

Universal mental health screenings would be carried out by existing school health and mental health staff. This could include nurses, members of the school’s crisis response team, staff from onsite mental health programs, partners from community organizations who provide behavioral health services in the building, or designated school personnel such as psychologists, social workers, counselors, and, when appropriate, administrators who have received the required training. All staff involved in administering the screening should be trained in the specific screening tools being used, as well as proper documentation procedures, confidentiality requirements, and protocol to identify students in need and ensure students receive appropriate follow up if needed.

At the same time, DOE should embed social emotional learning (SEL) and mental health literacy into advisory and homeroom curricula aligned with the State’s Portrait of a Graduate. Embedding SEL and help seeking skills into consistent advisory structures, such as Outward Bound’s “Crew” model, would ensures that students know how to ask for support and build trusted relationships with adults. Together, universal mental health screening and strengthened SEL would create a proactive, schoolwide approach to mental health that catches needs early, builds trust, and makes mental health support a normal part of everyday school life.

- Establish a formal, cross-agency working group to create a financially realistic plan to move DOE toward national mental health staffing standards. Research consistently shows that every dollar invested in early mental health intervention yields $2 to $10 in long-term savings. Staffing investment is a foundational step to building schools’ capacity for early mental health intervention. But meeting these staffing ratios would require a significant investment—between $401.8 million and $425.5 million—and must be weighed against many competing priorities across the school system.[66] A coordinated working group led by DOE’s Office of School Health and DOHMH, with representation from school leaders, clinicians, the United Federation of Teachers, students, and community partners, can develop a phased, fiscally responsible roadmap that prioritizes the most urgent needs while moving the City toward national staffing standards.

This Working Group would evaluate real-time school-level staffing needs, assess hiring and retention barriers, and identify systemic obstacles that prevent schools from obtaining and sustaining adequate mental health teams. The Working Group should also produce regular public reports that track progress toward meeting national staff-to-student ratios.

By institutionalizing this coordinated effort, the City can move beyond ad-hoc, year-to-year staffing decisions and begin building a realistic, fiscally responsible, and proactive path toward the level of mental health staffing that students have needed for years.

- Adopt enhanced and measurable goals to strengthen and expand School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs) and baseline funding for the Mental Health Continuum so that students have equitable access to integrated mental and behavioral health care. Stabilizing and fully funding the SBHCs that are already operating would cost the City an additional $20.2 million per year, based on the Community Health Care Association of New York State (CHCA) model ($100,000 per campus plus $100 per student). Bringing SBHCs to all large high schools citywide would require 75 new centers, costing the City an estimated additional $20.1 million per year to operate, with additional funding needed for start-up. The City should make these investments and pair them with a clear framework for SBHC growth, including a straightforward process for schools to request a center and annual surveys to assess need, capacity, and interest. This process should include regular communication with school leadership, dedicated points of contact, and annual surveys to assess demand, operational capacity, unmet mental health needs, and interest in hosting an SBHC.

Comprehensive, high-population schools with chronic unmet mental health needs should be prioritized first, reducing the scale of investment required for full citywide expansion while ensuring alignment with class-size mandates and space constraints. A formal process will also help the City develop long-term relationships with schools, improve coordination, and generate the data needed to guide future expansion.

Additionally, the City should baseline $5 million for the Mental Health Continuum, a critical funding stream supporting several of the City’s SBMHCs, as well as a range of essential programs. This funding underpins expedited access to mental health care for students experiencing acute needs, provides consultation and training supports for school staff to better identify and address emerging mental health issues, and ensures crisis response teams can rapidly intervene when urgent situations arise. Furthermore, the Continuum invests in Collaborative Problem Solving training, equipping educators and mental health professionals with tools to address behavioral challenges through compassionate, evidence-based methods, and prioritizes culturally responsive family engagement, fostering stronger partnerships between schools and the diverse communities they serve. Securing this funding as a baseline would not only maintain current staffing and programming levels but also provide a foundation for expanding services to reach more students across the City.

- Expand access to Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) training for school faculty and students. All educators and school staff should be equipped to recognize and respond to mental health challenges through evidence-based MHFA training.

According to interviews conducted by the Comptroller’s Office, school administrators report that MHFA has increased staff confidence in addressing student mental health needs and improved schoolwide awareness of early warning signs. MHFA is already embedded in State legislation and promoted by the Mental Health Association in New York State. By expanding MHFA training across DOE schools would ensure earlier intervention and stronger referral systems.