Comments on New York City’s Preliminary Budget for Fiscal Year 2023 and Financial Plan for Fiscal Years 2022-2026

I. Executive Summary

The Preliminary Budget closes the $2.88 billion budget gap projected in November, on the strength of an expected $2.77 billion surplus in FY 2022, derived primarily from $1.60 billion in additional tax revenues and savings of $866 million from the Program to Eliminate the Gap (PEG). Out-year gaps are $2.72 billion in FY 2024, $2.23 billion in FY 2025 and $3.01 billion in FY 2026.

The Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the Financial Plan indicates that the City could end FY 2022 with $1.37 billion in additional resources, driven by higher tax revenues (noting that tax collections through January are $1.6 billion ahead of the November projection, and nearly the same as the Mayor’s total projected increase, with five months remaining in the fiscal year). However, expense risks outweigh tax revenue offsets for the remainder of the plan, with net risks of $119 million in FY 2023, increasing to $1.42 billion in FY 2026. As a result, gaps could reach $3.25 billion in FY 2024, $2.93 billion in FY 2025, and $4.43 billion in FY 2026.

The FY 2023 Preliminary Budget totals $98.54 billion, $8.0 billion less than the modified FY 2022 budget. The drop is attributable to lower Federal COVID relief, which falls to $2.33 billion in FY 2023 from $10.20 billion in FY 2022. Over the five years of the plan, Federal COVID relief, excluding $750 million in unrestricted FEMA relief and $294 million in unrestricted State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund grants, totals $15.24 billion.

Both the Comptroller’s and the Mayor’s baseline economic scenarios assume growth will slow down in tandem with inflation as the economy adjusts to higher interest rates. In these scenarios, there is a decline in personal income and business taxes, with the Mayor front-loading the drop in FY 2022. In the Mayor’s projections, the unexpected strength in the FY 2023 tentative assessment roll is tempered by the assumption of very high reductions from tax appeals. Due to the combination of lower growth in assessments and a higher share of uncollectible levy, the Mayor expects property tax receipts to grow on average by 1.6 percent per year versus the Comptroller’s 2.5 percent.

There are significant new needs proposed by the Mayor in the Preliminary Budget. The larger additions are in Fair Fares, Fair Futures, the Summer Youth Employment Program, and New Family Home Visits for a total of nearly $200 million a year in FY 2023 – FY 2026. The Mayor is also proposing to increase the City’s EITC at a cost of $250 million per year and the creation of two new tax programs to favor the provision of child care at a cost of $50 million per year.

The Financial Plan removes the previously assumed but unspecified labor savings of $500 million per year starting in FY 2023. The Financial Plan also partially addresses funding shortfalls in charter school tuition, pupil transportation, and homeless shelters. The funding is baselined and absorbs $548 million in FY 2023 and nearly $600 million on average in FY 2024-FY 2026. These costs and the removal of the unspecified labor savings are covered by PEG savings of $1.1 billion per year in FY 2023 – FY 2026.

In the Comptroller’s estimate, however, a combination of under-budgeting of recurring expenditures for overtime, charter school tuition, Carter cases, homeless shelters, rental assistance, paratransit, and prevailing wages for shelter security guards; along with the potential extension of a number of ongoing education initiatives supported by time-limited stimulus funds poses additional expense risks of $1.04 billion in FY 2023, $1.10 billion in FY 2024, $1.31 billion in FY 2025, and $2.00 billion in FY 2026.

While the Comptroller’s restated gaps remain manageable by historical standards, they do not reflect key risks. First, with all City labor agreements set to expire by 2023 and collective bargaining set to begin amidst rising inflation, the City’s reserve to fund labor contracts assumes no raises for the first two years and 1 percent raises each year after. A citywide full-year additional raise of 1 percent would cost $450 million annually. Economic risk is more difficult to quantify and stems from the possibility that a fast monetary tightening will push the economy into recession, particularly if repercussions from the Ukrainian conflict were to further stoke inflationary pressures.

In light of these risks, the Financial Plan falls short by increasing reserves by only a nominal amount. A structured approach is needed to regulate deposits into and withdrawals from the City’s Rainy Day Fund, in order to build an adequate cushion to limit the damage of fiscal tightening during future downturns.

Table 1. FY 2022 – FY 2026 Financial Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | Change FYs 2022 –2026 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dollar | Percent | ||||||

| Revenues | |||||||

| Taxes: | |||||||

| General Property Tax | $29,554 | $31,034 | $31,291 | $31,466 | $31,526 | $1,972 | 6.7% |

| Other Taxes | 33,555 | 34,117 | 35,762 | 37,455 | 38,488 | 4,933 | 14.7% |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 921 | 721 | 721 | 721 | 721 | (200) | (21.7%) |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $64,030 | $65,872 | $67,774 | $69,642 | $70,735 | $6,705 | 10.5% |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 7,250 | 6,980 | 7,036 | 7,065 | 7,092 | (158) | (2.2%) |

| Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid | 1,044 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (1,044) | (100.0%) |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (2,153) | (1,850) | (1,848) | (1,838) | (1,838) | 315 | (14.6%) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | (15) | (15) | (15) | (15) | (15) | 0 | 0.0% |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $70,156 | $70,987 | $72,947 | $74,854 | $75,974 | $5,818 | 8.3% |

| Other Categorical Grants | 1,149 | 1,013 | 1,006 | 1,005 | 1,001 | (148) | (12.9%) |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | 730 | 734 | 732 | 731 | 731 | 1 | 0.1% |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 18,014 | 9,385 | 8,644 | 7,928 | 6,902 | (11,112) | (61.7%) |

| State Categorical Grants | 16,490 | 16,417 | 16,642 | 16,888 | 16,943 | 453 | 2.7% |

| Total Revenues | $106,539 | $98,536 | $99,971 | $101,406 | $101,551 | ($4,988) | (4.7%) |

| Expenditures | |||||||

| Personal Service | |||||||

| Salaries and Wages | $31,235 | $30,599 | $30,676 | $30,880 | $31,197 | ($38) | (0.1%) |

| Pensions | 9,932 | 9,665 | 9,048 | 8,176 | 7,561 | (2,371) | (23.9%) |

| Fringe Benefits | 12,298 | 12,643 | 13,729 | 14,683 | 15,398 | 3,100 | 25.2% |

| Subtotal-PS | $53,465 | $52,907 | $53,453 | $53,739 | $54,156 | $691 | 1.3% |

| Other Than Personal Service | |||||||

| Medical Assistance | $6,546 | $6,494 | $6,494 | $6,494 | $6,494 | ($52) | (0.8%) |

| Public Assistance | 1,651 | 1,650 | 1,650 | 1,650 | 1,650 | (1) | (0.1%) |

| All Other | 41,891 | 33,820 | 33,428 | 33,542 | 33,251 | (8,640) | (20.6%) |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $50,088 | $41,964 | $41,572 | $41,686 | $41,395 | ($8,693) | (17.4%) |

| Debt Service | |||||||

| Principal | $3,318 | $4,051 | $4,188 | $4,120 | $4,202 | $884 | 26.6% |

| Interest & Offsets | 3,446 | 3,891 | 4,077 | 4,683 | 5,395 | 1,949 | 56.6% |

| Subtotal Debt Service | $6,764 | $7,942 | $8,265 | $8,803 | $9,597 | $2,833 | 41.9% |

| FY 2021 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | ($6,107) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $6,107 | (100.0%) |

| FY 2022 BSA | $3,732 | ($3,732) | $0 | $0 | $0 | ($3,732) | (100.0%) |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | $250 | $250 | $250 | $250 | $250 | NA |

| General Reserve | $250 | $1,055 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $1,000 | $750 | 300.0% |

| Deposit to Rainy Day Fund | $500 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | ($500) | (100.0%) |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | ($2,153) | ($1,850) | ($1,848) | ($1,838) | ($1,838) | $315 | (14.6%) |

| Total Expenditures | $106,539 | $98,536 | $102,692 | $103,640 | $104,560 | ($1,979) | (1.9%) |

| Gap to be Closed | $0 | $0 | ($2,721) | ($2,234) | ($3,009) | ($3,009) | NA |

NOTE: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 2. Plan-to-Plan Changes

February 2022 Plan vs. November 2021 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 |

| Revenues | ||||

| Taxes: | ||||

| General Property Tax | $122 | $842 | $672 | $439 |

| Other Taxes | 1,481 | (407) | (462) | (232) |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $1,603 | $435 | $210 | $207 |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 110 | 449 | 498 | 498 |

| Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid | 294 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (69) | (401) | (398) | (394) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $1,938 | $483 | $310 | $311 |

| Other Categorical Grants | 29 | 20 | 15 | 15 |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 1,500 | 101 | 31 | 13 |

| State Categorical Grants | 224 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Total Revenues | $3,692 | $611 | $363 | $341 |

| Expenditures | ||||

| Personal Service | ||||

| Salaries and Wages | ($138) | ($346) | ($412) | ($492) |

| Pensions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fringe Benefits | (26) | 316 | 306 | 302 |

| Subtotal-PS | ($164) | ($30) | ($106) | ($190) |

| Other Than Personal Service | ||||

| Medical Assistance | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Public Assistance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All Other | 1,235 | 924 | 927 | 1,096 |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $1,235 | $924 | $927 | $1,096 |

| Debt Service | ||||

| Principal | $0 | $0 | $24 | $26 |

| Interest & Offsets | (27) | (52) | (94) | (103) |

| Subtotal Debt Service | ($27) | ($52) | ($70) | ($77) |

| FY 2021 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| FY 2022 BSA | $2,767 | ($2,767) | $0 | $0 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| General Reserve | ($50) | $55 | $0 | $0 |

| Deposit to Rainy Day Fund | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | ($69) | ($401) | ($398) | ($394) |

| Total Expenditures | $3,692 | ($2,271) | $353 | $435 |

| Gap to be Closed | $0 | $2,882 | $10 | ($94) |

NOTE Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 3. Plan-to-Plan Changes

February 2022 Plan vs. June 2021 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 |

| Revenues | ||||

| Taxes: | ||||

| General Property Tax | $122 | $842 | $672 | $439 |

| Other Taxes | 1,552 | (407) | (462) | (232) |

| Tax Audit Revenues | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: Taxes | $1,674 | $435 | $210 | $207 |

| Miscellaneous Revenues | 377 | 508 | 575 | 591 |

| Unrestricted Intergovernmental Aid | 1,044 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Less: Intra-City Revenues | (262) | (410) | (409) | (404) |

| Disallowances Against Categorical Grants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal: City-Funds | $2,833 | $533 | $376 | $394 |

| Other Categorical Grants | 124 | 20 | 15 | 15 |

| Inter-Fund Revenues | 5 | 9 | 7 | 6 |

| Federal Categorical Grants | 4,317 | 141 | 41 | 20 |

| State Categorical Grants | 537 | 109 | 16 | 11 |

| Total Revenues | $7,816 | $812 | $455 | $446 |

| Expenditures | ||||

| Personal Service | ||||

| Salaries and Wages | ($188) | ($212) | ($270) | ($348) |

| Pensions | (105) | (804) | (1,612) | (2,421) |

| Fringe Benefits | (79) | 804 | 796 | 793 |

| Subtotal-PS | ($372) | ($212) | ($1,086) | ($1,976) |

| Other Than Personal Service | ||||

| Medical Assistance | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Public Assistance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All Other | 5,033 | 1,509 | 1,358 | 1,541 |

| Subtotal-OTPS | $5,033 | $1,509 | $1,358 | $1,541 |

| Debt Service | ||||

| Principal | ($185) | $213 | ($113) | $40 |

| Interest & Offsets | (80) | (662) | (411) | (590) |

| Subtotal Debt Service | ($265) | ($449) | ($524) | ($550) |

| FY 2021 BSA and Discretionary Transfers | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| FY 2022 BSA | $3,732 | ($3,732) | $0 | $0 |

| Capital Stabilization Reserve | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| General Reserve | ($50) | $55 | $0 | $0 |

| Deposit to Rainy Day Fund | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Less: Intra-City Expenses | ($262) | ($410) | ($409) | ($404) |

| Total Expenditures | $7,816 | ($3,239) | ($661) | ($1,389) |

| Gap To Be Closed | $0 | $4,051 | $1,116 | $1,835 |

NOTE: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

Table 4. Risks and Offsets to the February 2022 Financial Plan

($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap)

| FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | |

| City Stated Gap | $0 | $0 | ($2,721) | ($2,234) | ($3,009) |

| Tax Revenues | |||||

| Property Tax | $15 | $317 | $696 | $957 | $1,122 |

| Personal Income Tax | 426 | (257) | (165) | 49 | 114 |

| Business Taxes | 247 | 66 | (209) | (325) | (450) |

| Sales Tax | 214 | 361 | 55 | (98) | (89) |

| Real Estate Transaction Taxes | 416 | 37 | (135) | (301) | (452) |

| All Other | 7 | 27 | (60) | (54) | (54) |

| Audit | 80 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

| Subtotal Tax Revenues | $1,405 | $801 | $432 | $478 | $441 |

| Non-Tax Revenues | |||||

| Fines | $60 | $29 | $26 | $26 | $26 |

| Interest Income | 0 | 14 | 45 | 33 | $36 |

| Subtotal Non-Tax Revenues | $60 | $43 | $71 | $59 | $62 |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Overtime | ($431) | ($348) | ($150) | ($150) | (150) |

| Charter School Tuition | 0 | 0 | (240) | (320) | (500) |

| Carter Cases | (100) | (300) | (300) | (300) | ($300) |

| 3K Expansion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (376) |

| Special Ed Pre-K Expansion | 0 | 0 | 0 | (47) | (95) |

| DOE Mental Health Services | 0 | 0 | 0 | (37) | (86) |

| Community Schools Expansion/Sustainability | 0 | 0 | 0 | (27) | (54) |

| Homeless Shelters | 0 | (117) | (117) | (117) | (117) |

| Rental Assistance | 0 | (177) | (177) | (177) | (177) |

| Paratransit Funding | (28) | (55) | (77) | (91) | (105) |

| Prevailing Wage for Shelter Security Guards | 0 | (41) | (41) | (41) | (41) |

| VRDB Interest Savings | 30 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 |

| eFMAP Savings | 180 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General Reserve | 250 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | ($99) | ($963) | ($1,027) | ($1,232) | ($1,926) |

| Total (Risks)/Offsets | $1,366 | ($119) | ($524) | ($695) | ($1,423) |

| Restated (Gap)/Surplus | $1,366 | ($119) | ($3,245) | ($2,929) | ($4,432) |

NOTE: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

II. The City’s Economic Outlook

The U.S. Economy in 2021

The U.S. economy grew robustly in 2021, with real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increasing 5.7 percent from 2020, and at an even faster annualized rate of 7.0 percent in the fourth quarter. It was the quickest pace of annual growth since 1984, driven by the ongoing rebound from the pandemic, low interest rates, and the $1.9 trillion in economic stimulus from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

Seasonally adjusted U.S. employment rebounded to 149.1 million in December 2021, up from 143.0 million in January 2021, and only 2 percent below the all-time high of 152.5 million in February 2020. The seasonally adjusted U.S. unemployment rate fell from 6.4 percent in January 2021 to 3.9 percent in December, approaching the pre-pandemic low of 3.5 percent in January 2020.

Although over 6 million returned to work through the course of the year, many Americans who dropped out of the labor force during the pandemic, have stayed out. The seasonally adjusted labor force participation rate was 61.9 percent in December, up from a low of 60.2 percent in April 2020, but still well below the pre-pandemic 63.4 percent of February 2020.

This economic rebound occurred despite a pandemic which, by many measures, continued through the year. The CDC reports 459,365 U.S. deaths for which COVID was the primary or contributing factor in 2021, even higher than the 385,474 in 2020, the first year of the pandemic.

With the pandemic ongoing and the economy still reeling early in the year, the Federal government passed the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 in March, providing $1.9 trillion in tax credits, fiscal aid to states, school aid, support for small businesses, rental assistance, and direct payments to Americans.

The Federal Reserve held the federal funds rate close to zero percent through the year, and continued its assets purchase program to provide liquidity and lower long-term rates, increasing its balance sheet by over $1.4 trillion in 2021.

Low borrowing costs and the ongoing desire of many to work from home stimulated demand for housing, particularly outside of major cities. The Case-Schiller home price index rose 18.8 percent in 2021, the fastest pace of home price appreciation since the 1987 inception of the index.

Rising home prices were just one factor driving U.S. inflation. The Consumer Price Index was up 7 percent in 12 months ending December 2021, the fastest rate of U.S. inflation in the since 1982. As low interest rates facilitated borrowing, and fiscal stimulus put more money in the pockets of many Americans, demand for goods rose. The U.S. economy struggled to meet this demand. Overseas goods production remained disrupted by COVID and COVID containment measures, such as those in China, and U.S. ports, particularly on the west coast, were congested by the large volume of imports. Domestically, decreased labor force participation meant fewer workers were available to move products around the county, onto shelves, and into the hands of consumers, exerting upward pressure on wages and consumer prices.

But rising inflation has not been contained to the markets for goods and homes. Inflation in the service sector, as measured by the CPI for services less rent of shelter, has been elevated for most of 2021 and hit 4.7 percent in January 2022, from January a year ago, the highest rate of increase since 2008. Service sector inflation has the potential to grow even worse with many still out of the labor force, and consumer demand transitioning back to pre-COVID spending patterns, which include more travel, dining out, and spending on entertainment and other services away from home.

U.S. Economic Outlook

As U.S. COVID cases, hospitalizations and deaths continue to fall without new COVID variants of concern on the horizon, inflation presents the greatest immediate threat to an ongoing U.S. economic recovery. Some price pressures are due to COVID-related supply chain disruptions, and can be expected to abate over time as the world’s economy adjusts. Some inflation is attributable to prices rebounding from depressed pandemic lows, particularly earlier in 2021, and is temporary. But some inflation is attributable to fiscal stimulus and loose monetary policy, which contribute to ongoing excess demand. The Federal Reserve will have to raise U.S. interest rates to slow the overheated economy and bring greater price stability.

Taming inflation without throwing the economy back into recession is delicate business. Prolonged periods of low interest rates have a tendency to inflate the prices of homes, stocks and other assets. When interest rates start rising it can reveal speculative excesses in new and over-leveraged sectors of the economy.

U.S. inflationary concerns are compounded by the war in Ukraine. Russia is a major exporter of oil, gas, and metals, and both Russia and Ukraine are among the world’s largest grain exporters. War and trade sanctions drive food and oil prices higher (prices which have a disproportionate impact on lower-income Americans), further complicating the Federal Reserve’s policy tightening without pushing the economy into a recession.

New York City’s Economic Condition and Outlook

New York City entered 2021 with private employment at a seasonally adjusted 3,464,000 in January, down from a pre-pandemic high of 4,095,000 in February 2020. A winter COVID surge peaked with over 8,000 cases on January 4th, 2021. Restaurants were closed to indoor dining, Broadway and many entertainment venues remained shuttered. The U.S. remained closed to most international visitors, schools were closed to in-person learning, and most office workers continued working remotely.

Nonetheless, newly approved vaccines brought the hope of a timely end to the pandemic, and a return to normal life. Vaccines remained in short supply through the winter months, with eligibility extended to those between 65 and 75 in January, to restaurant workers and taxi drivers in February, and those over age 50 in April. February also brought a return to indoor dining and fitness in New York City, and a return of middle-school students to in-person learning. High school students returned to schools in March.

However, the process of reopening was not smooth. The July wave caused by the Delta variant led most New York City businesses to postpone their return to offices. In August, New York City began requiring proof of vaccination for indoor dining, at gyms, and at indoor entertainment venues. In September, Broadway reopened with a vaccine mandate and mask requirement for theatre goers, and most municipal workers returned to offices full-time. In October, the City announced unvaccinated teachers would be put on unpaid leave, and in November announced the same would apply to other unvaccinated municipal employees. November also brought a reopening of the U.S. to international visitors. Through the course of the year greater vaccine availability, and widespread mandates, brought the vaccinated share of New York City residents steadily higher, rising above 80 percent in December.

Calendar year 2021 ended with the arrival of the even more infectious Omicron variant, and another winter COVID surge. 56,790 new cases were reported on December 27th, a pandemic high to be surpassed only by the 60,612 on January 3, 2022. However, the economic repercussions appear to have been less severe.

The reopening of the economy in 2021 fell short of a full return to normal. New York City private employment finished the year at a seasonally adjusted 3,682,000, up 218,000 from January, but 413,000 below the pre-pandemic peak of 4,095,000 in February of 2020. Job losses from pre-pandemic levels were concentrated in the Accommodation and Food Services and Retail sectors, and employment in these sectors is likely to remain depressed from pre-pandemic levels, as many of the office workers that once patronized Manhattan bars, restaurants and stores on a daily basis continue to work remotely, at least part of the time.

Table 5. New York City Employment and Changes as of December 2021

| (Seasonally Adjusted, thousands) | Dec. ‘21 | Change from Feb. 2020 Peak | Change from Apr. ‘20 Lows | Change from Jan. ‘21 | Change from Nov. ’21 |

| Total Private Employment | 3,682 | (413) | 509 | 218 | 15 |

| Financial Activities | 457 | (30) | (12) | (10) | (0) |

| Information | 222 | (7) | 16 | 14 | 2 |

| Professional and Business Serv. | 738 | (40) | 50 | 44 | 6 |

| Educational Services | 232 | (24) | 2 | 4 | (1) |

| Healthcare and Social Assistance | 799 | (21) | 88 | 26 | (1) |

| Arts, Entertainment & Recreation | 77 | (18) | 26 | 25 | 4 |

| Accommodation and Food Serv. | 251 | (122) | 143 | 78 | 2 |

| Other Services | 161 | (34) | 32 | 6 | (0) |

| Retail Trade | 301 | (44) | 71 | 15 | 2 |

| Wholesale Trade | 123 | (17) | 14 | 4 | 1 |

| Transportation and Warehousing | 121 | (14) | 22 | 15 | 1 |

| Utilities | 15 | (1) | (0) | (0) | (0) |

| Construction | 132 | (30) | 44 | (3) | (2) |

| Manufacturing | 53 | (12) | 14 | 0 | 1 |

Source: N.Y. Dept. of Labor, seasonally adjusted by NYC OMB

Continuing patterns of remote work present one of the greatest challenges to New York City’s economic recovery going forward. New York City’s holiday COVID surge depressed year-end office occupancy to 10 percent of pre-pandemic levels, the lowest in 2021.[1] Although office occupancy is recovering, telecommuting is likely to remain an important part of office work going forward, and this will continue to be felt in the demand for retail and office space.

Although New York City office vacancy fell to 124 million square feet at the end of 2021, down from a peak of almost 128 million square feet in the second quarter, it remains well above pre-pandemic levels. Average asking rents per square foot have fallen from a $69 at the end of 2019 to around $65 at the end of 2021.

Chart 1. Total New York City Office Square Footage Available for Rent, and Average Asking Rents

Source: CoStar

The Comptroller’s Office forecast has robust New York City economic and employment growth continuing in 2022, as COVID cases continue to decline without a resurgence from new COVID variants or resort to non-pharmaceutical interventions. Economic growth is forecast to slow in the outyears as interest rates rise steadily to rein in inflation, cooling asset and labor markets, but without throwing the economy into recession.

Table 6. Selected Economic Indicators, Annual Averages,

Comptroller and Mayor’s Forecast, 2021 to 2026

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SELECTED U.S. ECONOMIC INDICATORS (ANNUAL AVERAGES) | |||||||

| Real GDP (2012 $, % Change) | Comptroller | 5.7 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.1 |

| Mayor | 5.7 | 4.1 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.4 | |

| Payroll Jobs, (Change In Millions) | Comptroller | 3.9 | 5.5 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| Mayor | 3.9 | 5.5 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | |

| Fed Funds Rate, (Percent) | Comptroller | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| Mayor | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.4 | |

| 10-Year Treasury Notes, (Percent) | Comptroller | 1.4 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 3.8 |

| Mayor | 1.4 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 3.0 | |

| SELECTED NYC ECONOMIC INDICATORS (ANNUAL AVERAGES) | |||||||

| Real GCP (2012 $, % Change) | Comptroller | 5.6 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 2.0 |

| Mayor | 10.8 | 6.7 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 2.9 | |

| Payroll Jobs, (Change In Thousands) | Comptroller | 44 | 237 | 132 | 127 | 30 | 3 |

| Mayor | 44 | 192 | 130 | 120 | 100 | 69 | |

| Wage-Rate Growth, (Percent) | Comptroller | 5.0 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.9 |

| Mayor | 5.2 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.5 | |

III. The FY 2023 Preliminary Budget

The FY 2023 Preliminary Budget released on February 16th totals $98.54 billion, $8.0 billion less than the modified FY 2022 budget. The decline in the budget stems primarily from a drop in Federal categorical grants as Federal COVID relief begins to wane. Federal categorical grants are projected to decline by $8.63 billion, with Federal COVID relief projected to drop by $7.87 billion to $2.33 billion in FY 2023, and taper off to $7 million by FY 2026. The City-funds FY 2023 Preliminary Budget, which is funded with City-generated revenues, is projected to increase by $831 million from FY 2022, a 1.18 percent growth.

The Preliminary Budget closes a $2.88 billion budget gap projected in November, primarily on the strength of a $2.77 billion increase in prepayments of a portion of FY 2023 debt service with FY 2022 budget surplus. Revenues in the Preliminary Budget are $611 million more than projected in the November Plan. However, a substantial portion of this is offset by an increase of $496 million in expenditures, excluding reductions from prepayments.

The increase in revenues stems primarily from revisions to City-funds revenues and Federal categorical grants which were revised upwards by $483 million and $101 million, respectively. Changes to Federal categorical stems primarily from technical modifications, about $51 million of which were revisions to grants from the Homeland Security Grant Program.

The City-funds revenue increase is driven by an increase of $833 million in property tax revenues, reflecting higher than expected taxable billable assessed value in the recent tentative property tax assessment roll. Non-property tax revenues were reduced by a net $107 million. Sales tax revenue was revised downward by $196 million, prompted by the emergence of the Omicron variant which the City expects will suppress consumer spending growth in the second half of FY 2022 and slow tourism recovery. Some of the downward revision to sales tax revenue is offset by increases in other non-property tax revenues, primarily increases of $59 million in business tax revenues, $14 million in commercial rent tax revenues, and $13 million in personal income tax (PIT) revenues. The City’s tax revenue forecast also includes three tax initiatives which, if enacted, will reduce tax revenues by $300 million annually, beginning in FY 2023. The tax initiatives propose increasing the earned income tax credit at a cost of $250 million annually; a property tax abatement to property owners for retrofitting property space for childcare centers at a cost of $25 million annually; and a childcare business tax credit for businesses providing child care space at their place of business at a cost of $25 million annually.

FY 2023 non-tax City-funds revenues show a modest increase of $43 million from the November Plan mainly as a result of a $58 million increase in its estimate of overnight interest revenue in anticipation of Fed funds rate increase over the Plan period. Technical adjustments to other non-tax revenues offset some of this increase.

Table 7. Changes to FY 2023 City-Funds Estimates

from the November 2021 Plan

| ($ in millions) | |

| Gap to be Closed – November 2021 Plan | ($2,882) |

| Revenues | |

|---|---|

| Property Tax Revenues | $833 |

| Non-Property Tax Revenues | (107) |

| Tax Program | (300) |

| Non-Tax Revenues | 43 |

| Revenues From PEGs | 14 |

| Total Revenue Changes | $483 |

| Expenditures | |

| Agency Expenditures | $926 |

| Savings from PEGs | (1,112) |

| Eliminate Unspecified Labor Savings | 500 |

| General Reserve | 55 |

| Total Expenditure Changes | $369 |

| Gap To Be Closed Before Prepayments | ($2,768) |

| FY 2022 Prepayment of FY 2023 Debt Service | $2,768 |

| Gap to be Closed – February 2022 Financial Plan | $0 |

FY 2023 City-funds expenditures, before accounting for the reduction in debt service from FY 2022 prepayments, show a net increase of $369 million from the November Plan. The increase is due to the elimination of $500 million of unspecified labor savings included in prior financial plans, a $926 million increase in agency spending driven by $799 million in new needs, and a $55 million increase to the FY 2023 General Reserve. Anticipated spending reductions of $1.11 billion from Program to Eliminate the Gap (PEG) initiatives offsets all but $369 million of the spending increase.

Major new need in six agencies, the Department of Education (DOE), the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), the Department of Social Services (DSS), the Department of Homeless Services (DHS), the Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD), and the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) account for $745 million, or 93 percent, of the FY 2023 new needs, as shown in Table 8. With the exception of the increase in charter school tuition funding and the re-estimate of shelter cost, the new needs in these agencies represent the baselining of FY 2022 spending needs to the outyears of the Plan. While the City has fully funded the charter school tuition rate increase in FY 2023, the additional outyear funding addresses only half of the needs identified in prior estimates by the City.

Table 8. Major New Needs in Six Agencies Account for $745 million of FY 2023 New Needs

| Agency | Initiatives | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOE | Charter Schools | $0 | $282 | $216 | $313 | $313 |

| Pupil Transportation | 0 | 134 | 184 | 185 | 185 | |

| ACS | Fair Futures | 0 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| DSS | Fair Fares | 16 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 |

| DHS | Shelter Cost Re-estimate | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 | 132 |

| DYCD | Summer Jobs | 0 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| SYEP Slot Expansion | 8 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | |

| DOHMH | New Family Home Visits | 0 | 30 | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| Total | $155 | $745 | $731 | $828 | $828 |

FY 2022 Budget Stabilization Account (BSA)

Since the November Plan, the City has recognized a net $2.77 billion of additional resources in the FY 2022 budget. Because these resources are not required to balance the current fiscal year’s budget, they are used to increase the FY 2022 Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), bringing the total FY 2022 BSA to $3.73 billion. The BSA will be used to prepay $1.96 billion of Transitional Finance Authority (TFA) Future Tax Secured (FTS) debt service and $1.77 billion of General Obligation (G.O.) debt service. As shown in Chart 2, these additional resources are the result of:

- A reduction of $50 million in the FY 2022 General Reserve;

- A net savings of $400 million from adjustments to prior-year accruals;

- Program to Eliminate the Gap savings of $866 million in FY 2022;

- An increase of $1.60 billion in tax revenues;

- An increase of $31 million in non-tax revenues; less

- Additional City-funds spending of $477 million

Chart 2. The February Plan Increases the BSA by $2.77 Billion

($ in millions)

Program to Eliminate the Gap (PEG)

On January 10, the City issued a letter to City agencies calling for agencies to develop program to eliminate the gap (PEG) to reduce agency City-funds by 3 percent in each of FY 2022 and FY 2023. Excluding savings from centrally budget expenses in the miscellaneous budget and debt service, agency PEGs total $820 million in FY 2022 and $943 million in FY 2023 — 2.1 percent and 2.7 percent, respectively, of the FY 2022 and FY 2023 November Plan City-funds expenditures in these agencies.

In total, including savings from debt service, and centrally funded expenditures, the February Plan PEGs total $1.99 billion in the first two years of the Plan and $5.36 billion over the Plan period. PEG initiatives are concentrated in FY 2022 and FY 2023 with outyear budget relief provided by recurring benefits from PEGs in the first two fiscal years of the Plan. As shown in Table 9, $407 million of the $866 million FY 2022 PEGs are recurring PEGs with estimated benefits of about $500 million in each of the outyear of the Plan. In FY 2023, all but $4 million of the PEGs are recurring PEGs, with estimated outyear benefits of more than $550 million annually. Recurring benefits account for almost 90 percent of the budget relief over the Plan period.

Table 9. Recurring PEGs Account for $4.81 Billion of the $5.36 Billion Budget Relief Over the Plan Period

| ($ in millions) | FY 2022 PEGs | FY 2023 PEGs | FY 2024 PEGs | FY 2025 PEGs | FY 2026 PEGs | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total PEGs | ||||||

| FY 2022 Benefits | $866 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $866 |

| FY 2023 Benefits | 566 | 560 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,126 |

| FY 2024 Benefits | 515 | 579 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 1,113 |

| FY 2025 Benefits | 518 | 589 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 1,125 |

| FY 2026 Benefits | 516 | 595 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 1,129 |

| Total | $2,981 | $2,322 | $57 | $0 | $0 | $5,360 |

| Recurring PEGs | ||||||

| FY 2022 Benefits | $407 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $407 |

| FY 2023 Benefits | 499 | 556 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,055 |

| FY 2024 Benefits | 504 | 579 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 1,101 |

| FY 2025 Benefits | 510 | 589 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 1,118 |

| FY 2026 Benefits | 515 | 595 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 1,128 |

| Total | $2,435 | $2,317 | $57 | $0 | $0 | $4,809 |

Almost two thirds of the PEG benefits over the Plan period are from vacancy reductions Citywide and spending reductions in the Department of Education. Vacancy reductions account for 3,080 of the PEG headcount reduction in FY 2022, and more than 3,300 of the reductions in each of the outyears of the Plan, and is expected to generate savings of $127 million in FY 2022, and an average of $291 million in each of the outyears. DOE PEGs, excluding vacancy reductions, are estimated to generate savings of $256 million in FY 2022 and more than $483 million in each of the outyears. Savings in FY 2022 include $110 million in central reduction and $55 million in State pre-K revenue offset. In the outyears, lower enrollment is projected to generate savings of about $375 million a year along with reductions of 3,227 full-time headcount in each year. Overall, PEG initiatives are expected to reduce full-time headcount by 3,205 in FY 2022, 7,026 in FY 2023, and 7,044 in each of FY 2024 through FY 2026. Other significant PEG savings include accrual savings of $113 million in the Police Department from unfilled uniform and civilian positions in the current fiscal year, and savings of $33 million in FY 2022 and $49 million in each of the outyears in DHS from the closing of hotel shelters for families with children.

Risks and Offsets

As Table 10 shows, the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the February Plan shows additional resources of $1.37 billion in FY 2022 and risks beginning at $119 million in FY 2023 and growing to $1.42 billion by FY 2026. The additional resources in FY 2022 are due to the Comptroller’s Office’s higher revenue forecast in excess of expense risks. In the outyears, while the Comptroller’s Office’s revenue forecast is higher than the Plan projections in each year, they are more than offset by the Comptroller’s Office’s expenditure risks. The Comptroller’s Office projects that tax revenues will be above the Plan forecast by more than $1.4 billion in FY 2022, $801 million in FY 2023, and an average of $450 million in each of the outyears of the Plan. The Comptroller’s Office also projects higher non-tax revenues from fines and interest income in each year of the Plan, ranging from $43 million to $71 million. The Comptroller’s Office’s tax revenue forecast is discussed in more detail in “Comptroller’s Office Revisions and Projections, FY 2022 – FY 2026” beginning on page 21.

The Comptroller’s Office estimates that expenditures could exceed the Plan projections in each year of the Plan, beginning at $99 million in FY 2022 and growing to $1.92 billion by FY 2026. The largest risk in FY 2022 is attributable to overtime spending, which the City estimates will remain close to the lows experienced during the pandemic. However year-to-date spending indicates otherwise, as discussed in “Overtime” beginning on page 36.

Risks to the City’s expenditures beginning in FY 2023 reflect the lack of, or insufficient funding of recurring expenditures, the so-called fiscal cliffs. These shortfalls include funding for charter school tuition, Carter cases, homeless shelters, rental assistance, prevailing wages for shelter security guards, and a number of core education initiatives supported by stimulus funds. Altogether, fiscal cliffs pose risks of $635 million in FY 2023, $875 million in FY 2024, $1.07 billion in FY 2025, and $1.75 billion in FY 2026. Fiscal cliffs account for two-thirds of the expenditure risks in FY 2023, growing to 91 percent by FY 2026.

Other expenditure risks include the City’s funding for paratransit. While the State requires the City to increase its funding of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s (MTA) net paratransit deficit from 33 percent to 50 percent, funding for paratransit in the Financial Plan does not reflect the increase in funding requirement. The Comptroller’s Office estimates that increasing the funding to 50 percent would increase the City’s paratransit funding by $28 million in FY 2022 and $105 million by FY 2026.

The City’s conservative estimates of interest rates on variable rate debt bonds (VRDB) provide some offset to expenditure risks. The Comptroller’s Office estimates that debt service on VRDB could be less than the Plan projections by $30 million in FY 2022 and $75 million annually in FY 2023 through FY 2026.

Looming on the horizon is the upcoming round of collective bargaining which could pose a significant risk to the budget. The City set aside resources in its labor reserve assuming zero percent increases in the first two years of the contracts and 1 percent increase in each year thereafter. Each additional percentage point in wage increases would cost $450 million per year.

It should also be noted that the risk to the economic outlook is now tilted to the downside as the Federal Reserve will lift interest rates with the intention of lowering inflation without pushing the economy into a recession, while the Ukrainian conflict could introduce further inflationary pressures and push asset prices lower.

Overall, the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of the Plan indicates that the City could end FY 2022 with a budget surplus of $1.37 billion and a deficit of $119 million in FY 2023. The analysis also shows larger gaps of $3.25 billion in FY 2024, $2.93 billion in FY 2025, and $4.43 billion in FY 2026.

Table 10. Risks and Offsets to the February 2022 Financial Plan

($ in millions, positive numbers decrease the gap and negative numbers increase the gap)

| FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | |

| City Stated Gap | $0 | $0 | ($2,721) | ($2,234) | ($3,009) |

| Tax Revenues | |||||

| Property Tax | $15 | $317 | $696 | $957 | $1,122 |

| Personal Income Tax | 426 | (257) | (165) | 49 | 114 |

| Business Taxes | 247 | 66 | (209) | (325) | (450) |

| Sales Tax | 214 | 361 | 55 | (98) | (89) |

| Real Estate Transaction Taxes | 416 | 37 | (135) | (301) | (452) |

| All Other | 7 | 27 | (60) | (54) | (54) |

| Audit | 80 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

| Subtotal Tax Revenues | $1,405 | $801 | $432 | $478 | $441 |

| Non-Tax Revenues | |||||

| Fines | $60 | $29 | $26 | $26 | $26 |

| Interest Income | 0 | 14 | 45 | 33 | $36 |

| Subtotal Non-Tax Revenues | $60 | $43 | $71 | $59 | $62 |

| Expenditures | |||||

| Overtime | ($431) | ($348) | ($150) | ($150) | (150) |

| Charter School Tuition | 0 | 0 | (240) | (320) | (500) |

| Carter Cases | (100) | (300) | (300) | (300) | ($300) |

| 3K Expansion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (376) |

| Special Ed Pre-K Expansion | 0 | 0 | 0 | (47) | (95) |

| DOE Mental Health Services | 0 | 0 | 0 | (37) | (86) |

| Community Schools Expansion/Sustainability | 0 | 0 | 0 | (27) | (54) |

| Homeless Shelters | 0 | (117) | (117) | (117) | (117) |

| Rental Assistance | 0 | (177) | (177) | (177) | (177) |

| Paratransit Funding | (28) | (55) | (77) | (91) | (105) |

| Prevailing Wage for Shelter Security Guards | 0 | (41) | (41) | (41) | (41) |

| VRDB Interest Savings | 30 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 75 |

| eFMAP Savings | 180 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| General Reserve | 250 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | ($99) | ($963) | ($1,027) | ($1,232) | ($1,926) |

| Total (Risks)/Offsets | $1,366 | ($119) | ($524) | ($695) | ($1,423) |

| Restated (Gap)/Surplus | $1,366 | ($119) | ($3,245) | ($2,929) | ($4,432) |

Revenue Analysis

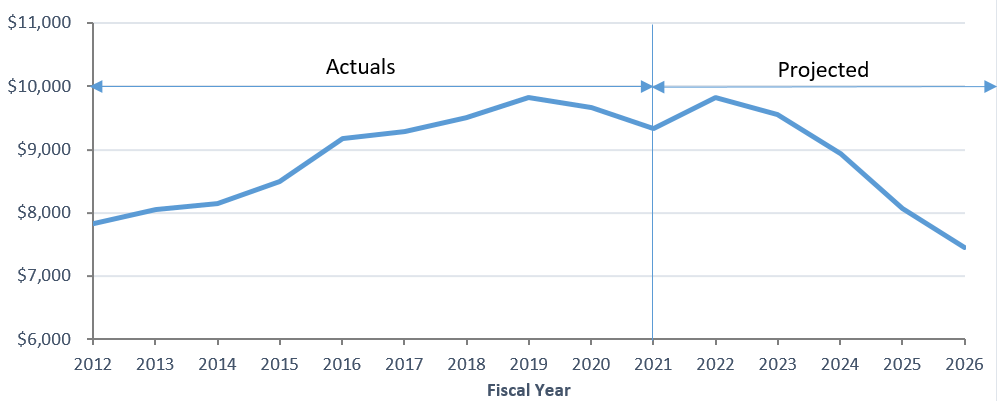

Total revenues in the February Plan are estimated to decline over the plan period from $106.5 billion in FY 2022 to $101.5 billion in FY 2026. The projected decline is largely due to decreases in federal aid related to the pandemic that boosted City revenues in FY 2022. City-funds revenues are projected to grow from $72.0 billion in FY 2022 to $77.7 billion in FY 2026. These projections reflect the City’s assumption of continued economic recovery over the Plan with City employment expected to recover to reach pre-pandemic levels in FY 2025. Tax revenue growth is expected to be driven primarily by non-property tax revenues, which are expected to increase by $4.7 billion from $34.5 billion in FY 2022 to $39.2 billion in FY 2025. Property tax revenue is projected to increase significantly in FY 2023 by 5.0 percent, but the City projects that growth thereafter will remain essentially flat[2]. Non-tax City-funds revenues is projected to remain relatively stable, growing modestly from $5.10 billion in FY2022 to $5.25 billion by FY 2026.

Tax Revenues

The City revised local tax revenues upwards in the current fiscal year by $1.6 billion compared to the November Plan. The revision is just $30 million above year-to-date collection trends through January (Table 12). The City however, did not carry forward collection trends through the remainder of the fiscal year. Tax revenues fiscal year-to-date through January grew 3.8 percent, and the City projects they will end FY 2022 2.3 percent lower than in FY 2021. The City’s increased revenue projections for FY 2023 – FY 2026 are mainly due to higher estimates for property tax revenue while overall revisions to non-property tax revenues were minor as shown in Table 11 below. The City is also proposing three new tax programs which are estimated to cost the City $300 million beginning in FY 2023.

Table 11. Revisions to the City’s Tax Revenue Assumptions

February 2022 Plan vs. November 2021 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 |

| November 2021 Financial Plan | $62,427 | $65,437 | $67,564 | $69,435 |

| Revisions: | ||||

| Property Tax | 124 | 848 | 678 | 445 |

| Personal Income (PIT) | 428 | 13 | 49 | 109 |

| Business | 404 | 59 | (67) | $13 |

| Sales | 265 | (196) | (165) | (75) |

| Real-Estate Transactions | 342 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All Other | 40 | 11 | 15 | 15 |

| Tax Audit | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tax Program | (300) | (300) | (300) | |

| Total | $1,603 | $435 | $210 | $207 |

| February 2022 Financial Plan – Total | $64,030 | $65,872 | $67,774 | $69,642 |

Table 12. Current Year to date Collections Trend vs. November 2021 Plan

| ($ in millions) | YTD Variance Through Jan. 22 |

|---|---|

| Property Tax | ($18) |

| Personal Income | 412 |

| Business | 261 |

| Sales | 442 |

| Real Estate Transactions | 419 |

| Other | 57 |

| Total | $1,573 |

Comptroller’s Office Revisions and Projections, FY 2022 – FY 2026

The Comptroller also revised current fiscal year projections to reflect higher than anticipated collections. Unlike the City’s, the Comptroller’s forecast assumes that some of this strength will carry forward through the remainder of the fiscal year, particularly for sales tax, income and business tax revenue. For FYs 2023 – 2026 there are major differences particularly for the forecast of property tax revenues, which the Comptroller anticipates will be considerably higher than the City’s estimates. Other differences are summarized in Tables 13 and 14 below. Higher interest rates will have a dampening effect on asset prices causing personal income tax (PIT) revenue to decline in the near term, slowing the growth of corporate profits, and causing real estate transactions to decline. These corrections are relatively moderate in comparison to the sharp downturns that the City experienced in 2002 and 2009. The risk to the forecast are tilted downward as the Fed faced a tough balancing act even before factoring in geopolitical uncertainty. At the time of this report, the forecast does not incorporate potential downside effects deriving from the Ukrainian conflict.

A more detailed discussion of the major revenue sources and differences in projections follows.

Table 13. Risks and Offsets to the City’s Tax Revenue Projections

| ($ in millions) | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 |

| Property | $15 | $317 | $696 | $957 | $1,122 |

| PIT | 426 | (257) | (165) | 49 | 114 |

| Business | 247 | 66 | (209) | (325) | (450) |

| Sales | 214 | 361 | 55 | (98) | (89) |

| Real Estate Transaction | 416 | 37 | (135) | (301) | (452) |

| Other | 7 | 27 | (60) | (54) | (54) |

| Audit | 80 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

| Total | $1,405 | $801 | $431 | $478 | $441 |

Table 14. Tax Revenue Forecast, Growth Rates

| FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | FYs 2022 – 26 Average Annual Growth |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Property | ||||||

| Mayor | -6.1% | 5.0% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 1.6% |

| Comptroller | -6.0% | 6.0% | 2.0% | 1.4% | 0.7% | 2.5% |

| PIT | ||||||

| Mayor | -6.1% | 3.9% | 4.0% | 4.1% | 1.9% | 3.5% |

| Comptroller | -3.3% | -0.8% | 4.7% | 5.6% | 2.3% | 2.9% |

| Business | ||||||

| Mayor | -4.4% | -0.2% | 0.6% | 2.8% | 4.7% | 2.0% |

| Comptroller | -0.9% | -2.7% | -3.4% | 1.2% | 3.1% | -0.5% |

| Sales | ||||||

| Mayor | 17.7% | 5.5% | 8.4% | 6.8% | 2.9% | 5.9% |

| Comptroller | 21.0% | 7.3% | 4.4% | 5.0% | 3.0% | 4.9% |

| Real Estate Transactions | ||||||

| Mayor | 28.2% | -9.4% | 5.6% | 5.4% | 2.9% | 0.9% |

| Comptroller | 49.6% | -21.1% | -2.0% | -1.7% | -3.5% | -7.5% |

| All Other | ||||||

| Mayor | 6.6% | 5.0% | 8.1% | 5.3% | 1.8% | 5.0% |

| Comptroller | 6.9% | 5.8% | 4.6% | 5.6% | 1.8% | 4.5% |

| Audit | ||||||

| Mayor | -19.2% | -21.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | -5.9% |

| Comptroller | -12.1% | -3.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | -0.8% |

| Total Tax with Audit | ||||||

| Mayor | -2.3% | 2.9% | 2.9% | 2.8% | 1.6% | 2.5% |

| Comptroller | -0.2% | 1.9% | 2.3% | 2.8% | 1.5% | 2.1% |

Property Taxes

Property tax revenue accounted for the most significant revision to the FY 2023 – FY 2026 projections for both the Comptroller and the City.[3] The higher estimates reflect recently released data from the Department of Finance (DOF) FY 2023 tentative roll which indicated that market values for most property types have rebounded significantly from the declines experienced last year. The most significant increase was for Class 4 commercial properties whose value, according to DOF’s estimates, rebounded by 11.7 percent in FY 2023 after last year’s decline of 17.4 percent Market values for most property types now exceed or are near pre-pandemic levels.[4]

Based on the tentative assessment roll alone, the City’s property tax levy would increase by almost $2.4 billion. Each year, however, adjustments occur from the time the tentative values are released in January to the final roll, released in May. There are two main sources for these adjustments — 1) data on property exemptions is not fully available when the tentative roll is released and 2) property owners can contest their tentative assessments. During the past five years these reductions have averaged 1.2 percent across all Class types. In the current Financial Plan, the City is assuming an overall reduction of 3.9 percent.

Table 15 summarizes the City’s and the Comptroller’s assumptions. The Comptroller concurs with the City’s assumption that reductions to assessments for Class 4 Properties could be almost 140 basis points higher than the average reduction. The current tentative roll indicates that Class B/C office market values have rebounded to almost 93 percent of their pre-pandemic level, similar to the recovery rate of Class A buildings. Based on office market data provided by Cushman and Wakefield, however, Class B/ C office properties have been disproportionally affected by higher direct vacancy rates.

The main difference between the Comptroller’s and the City’s estimates of the tentative to final roll reductions are due to different assumptions for residential Class 1 and Class 2 properties. The City is assuming that higher than average reductions will occur for both Class 1 and Class 2 properties. These assessments however appear to be in line with market value conditions. As reported by StreetEasy, rents and vacancies as of December 2021 for rental properties, which form the basis for Class 2 assessments, are near the pre-pandemic levels and therefore are generally consistent with the levels reported in the tentative assessment roll. Class 1 properties were largely unaffected by the pandemic as DOF market values also imply.

Table 15. Tentative to Final Roll Changes in Assessed Value: Comptroller vs City

| Class Type | OMB Declines Tentative to Final, $ M | OMB Declines Tentative to Final, % | Comptroller Declines Tentative to Final, $ M | Comptroller Declines Tentative to Final, % | 5 YrAvg Chg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | -$615 | -2.6% | -$81 | -0.3% | -0.3% |

| Class 2 | -$3,400 | -3.1% | -$1,361 | -1.3% | -1.3% |

| Class 3 | -$112 | -0.6% | $276 | 1.4% | 1.4% |

| Class 4 | -$4,200 | -3.3% | -$4,134 | -3.3% | -1.9% |

| Overall | -$8,327 | -3.0% | -$5,299 | -1.9% | -1.2% |

As a result of the different assumptions regarding residential properties, the Comptroller’s starting point for the final FY 2023 levy is $203 million higher than the City’s. While both the Comptroller and the City assume slowing growth for residential properties due to higher interest rates and a slowing economy, the City assumes growth in assessed values of 1.2 percent, while the Comptroller forecasts growth of 2.6 percent. These differences account for most of the higher levy estimate over the remainder of the Plan. For Class 4 properties, both the Comptroller and the City assume that growth will be essentially flat as office properties continue to face headwinds from high vacancies and the potential impact of shifts in demand due to increased work from home. Differences in the levy forecast for Class 1 and 3 are also minor.

In addition to these differences in the levy forecast, the Comptroller’s office assumes that offsets in property tax collections resulting from delinquencies and cancellations will be about 50 basis points lower than the City’s estimate, or about $150 million – $200 million throughout the Plan period.

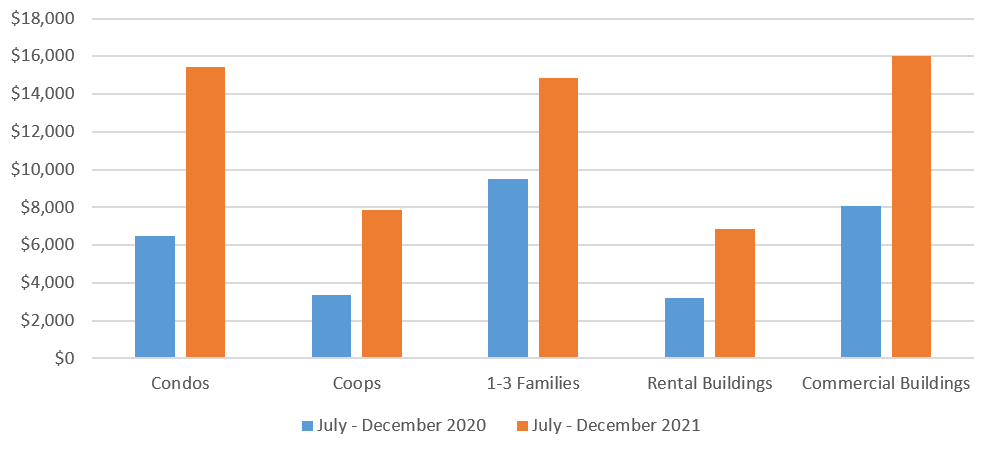

Real Estate Transaction Taxes

FY 2022 has been an exceptional year for real estate related taxes so far. Part of this strength is the result of the rebound from the complete halt that occurred in 2020 due to lockdowns and uncertainty that kept potential buyers on the sidelines. Once the City opened and the distribution of vaccines restored confidence, delayed purchases and new deals started to take place. All major real estate categories have witnessed significant gains in sales (Chart 3). The combined revenues from real estate-related taxes (the Real Property Transfer Tax and the Mortgage Recording Tax) in the first seven months of FY 2022 exceeded $1.84 billion — only $100 million short of the entire collections for FY 2021.

Chart 3. Real Estate Sales by Major Categories

($ in millions)

As a result of the bounce back from delayed deals and strong residential market recovery, the Comptroller’s Office projects an increase of 49.6 percent in the combined revenues from real estate-related taxes in FY 2022 to $2.9 billion (through January, the growth rate in FY 2022 is 94.6 percent). This is approximately $416 million higher than the City’s forecast. In the outyears, the combination of slowing growth in NYC employment and the drying up of refinancing activity due to increases in interest rates result in projected declines from FY 2022’s lofty levels. Differences with City’s forecast are summarized in Tables 13 and 14.

Personal Income Tax

Personal Income tax (PIT) collections continued to grow at a solid pace in FY 2022 and are 7.8 percent higher year to date through January. Much of the strength is due to withholding which was 9.8 percent higher year over year, reflective of both the continued rebound in City employment as well as strong wage growth from Wall Street bonuses. Non-withheld income is up by a more moderate 2.3 percent, due to unusual weakness in the offset component which is down by almost 38 percent.

The Comptroller’s and the City’s forecasts for withholding are very similar so the discussion of forecast differences is limited to non-withheld income.

Offsets are payments made by the State to the City to account for the fact that the exact distribution of liability between the State and the City is not known initially when filers submit estimated payments. As this distribution becomes known later, a true-up occurs which has resulted in the City receiving large payments from the State, typically in October. This year, however, the City only received $231 million compared to the $423 million it received in the prior year and the two years before then. The lower payment may be the result of the April 15 tax filing date being pushed back to May 15th last year. This provided the State with more information to pay the City upfront its share of estimated payments in May, therefore reducing October’s payment. Since the overall liability due to the City didn’t change, this simply moved the timing of receipts.

The question therefore, in addition to unusual uncertainty regarding April payments and liability, is the pattern of offsets going forward. [5] The Comptroller’s assumptions for FY 2022 and FY 2023 with regards to both April payments and offsets are significantly different compared to the City’s. The City is assuming that payments associated with non-withheld liability will drop quickly this year and then remain essentially flat in FY 2023, before slightly growing in FY 2024 (see Table 16 below). The Comptroller is assuming a lower decline to occur this year, with additional declines in FY 2023 and FY 2024 given the stock market’s recent performance. The forecast assumes a decline in the S&P500 to occur as a result of Fed tightening (8.9 percent between December 2021 and December 2022). The forecast does not incorporate potential repercussions from the Ukrainian conflict.

With regards to timing issues, the City anticipates offset payments to remain at almost half the 2021 level, attributing this lower level to a permanent change in the timing of payments.[6] The State’s recent budget however indicates that offset payments will likely be close to $1.4 billion in Fiscal Year 2023, a trend of payments that would be more consistent with past experience. The Comptroller’s Office assumes that after this year’s anomaly, offset payments will resume their normal timing pattern.

Table 16. Non-Withheld Income FY 2021-2024

| City | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 |

| Estimated Payments + Settlements |

$3,685 | $2,699 | $2,674 | $2,764 |

| Offsets | 1,282 | 640 | 702 | 689 |

| Total | $4,967 | $3,339 | $3,376 | $3,453 |

| Comptroller | FY 2021 | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 |

| Estimated Payments

+ Settlements |

$3,685 | $2,950 | $2,206 | $2,238 |

| Offsets | 1,282 | 765 | 900 | 1,000 |

| Total | $4,967 | $3,715 | $3,106 | $3,238 |

In the Comptroller’s scenario, PIT resumes growth in the outyears of the Plan. The Comptroller’s outyear forecast for PIT growth in FY 2025 and FY 2026 is similar to the City’s, as shown in Table 14.

Sales Tax

The Comptroller projects sales tax revenue to grow by 21.0 percent in FY 2023. This increase is driven by a rebound in sales tax revenue related to the tourism sectors (accommodations, restaurants and bars and transit). Sales tax revenue from the tourism sector had collapsed at the height of pandemic due to travel restrictions and business closures. Restrictions imposed on foreign travelers, which were lifted only recently had a disproportionate impact on New York City. With the removal of most travel restrictions, City sales tax related to the tourism sectors rebounded to almost 80 percent of pre-pandemic levels as of December 2021. Despite concerns that the recent spread of the Omicron variant would once again sharply curtail travel and spending, the threat to tourism appears to be waning.

FY 2023 revenues are also boosted by the expiration of the distressed hospital sales interceptor which subtracted $250 million and $150 million from revenues in FY 2021 and 2022, respectively.[7] The rate of growth decelerates as tourism approaches pre-pandemic levels by the end of FY 2025 and year-over-year growth comparisons become less favorable. By the end of the Plan, sales tax growth slows to about 3 percent reflecting growth in employment and wages.

The differences with the City’s forecast are shown in Tables 13 and 14. As previously noted, the City did not carry forward the momentum from actual collections in the current or the next fiscal year (in fact, the City increases sales tax by slightly less than collections as of December 2021). As a result, the Comptroller’s estimates for sales tax revenues are considerably higher in the near term while outyear differences are more muted.

Business Income Taxes

Revenue from Business Taxes (GCT and UBT) combined grew strongly during the pandemic and year-to-date collections exceeded the November forecast by $261 million as of January. The current strength in local business tax revenue is due to both the surge in Wall Street profits to a near record $58 billion in the most recent year and favorable fiscal policy which provided direct assistance to corporations (through the Paycheck Protection Program) and boosted consumer income through expanded unemployment benefits and stimulus checks.

These tailwinds are not expected to continue in the remainder of the Plan. The Comptroller’s office projects a decline in Wall Street profits throughout the Plan period. As a result, the Comptroller estimates Business Tax revenue is projected to decline by almost 2.5 percent on average in FY 2022 through FY 2024 before stabilizing over the remainder of the Plan. The City is projecting even greater declines in the near term but a quicker recovery in the out years as shown in Tables 13 and 14.

Audit Revenues

The City’s forecast assumes that audit collections, which have averaged nearly $1 billion annually over the last decade will decline from an estimated $921 million in FY 2022 to $721 in the out years. While recognizing that audit revenues could be volatile, the Comptroller assumes that revenue from audits will hover more closely to the long-term average. The resulting differences between the City and the Comptroller’s forecast for audit revenue are shown in Table 13 and 14.

City Tax Programs

The City is proposing three tax programs to assist low-income households and households with children. The Mayor is asking the State to enact legislation that would boost the EITC the City provides to low income households from the current five percent match of Federal EITC. The cost to the City would be roughly $250 million. In addition, to help childcare needs the Mayor is proposing property tax credits for the retrofitting of childcare centers and business tax credits for the provision of onsite childcare. Together, the two programs are estimated to cost $50 million per year.

Miscellaneous Revenues

Miscellaneous revenues in the FY 2023 Preliminary Budget remain essentially unchanged from the November Plan with a net increase of $48 million to $5.13 billion. The revision reflects mainly increases of $65 million in projected revenues from interest income and $13 million in water and sewer revenues. These increases are partially offset by small declines in projected revenues from fines and forfeitures, charges for services and other miscellaneous revenues.[8]

The revised FY 2022 forecast also increased slightly from the November Plan projection by a net $41 million, including $10.5 million in PEGs. Projections for fines and forfeitures, licenses, franchises and permits, water and sewer and other miscellaneous revenues inched up by a combined $65 million while projections for rental income and charges for services declined by $2 million and $22 million respectively. Table 17 shows the changes in the FY 2022 miscellaneous revenue projections since the November Plan.

Table 17. Changes in FY 2022 Estimates

January 2022 Plan vs. November 2021 Plan

| ($ in millions) | November | January | Change |

| Licenses, Permits & Franchises | $657 | $672 | $15 |

| Interest Income | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| Charges for Services | 1,024 | 1,002 | ($22) |

| Water and Sewer Charges | 1,668 | 1,682 | 14 |

| Rental Income | 248 | 246 | ($2) |

| Fines and Forfeitures | 1,065 | 1093 | 28 |

| Other Miscellaneous | 385 | 393 | $8 |

| Total | $5,056 | $5,097 | $41 |

Revenue projections for licenses, permits and franchises increased by a net $15 million. This revision is mostly due to an increase of $27.9 million in mobile telecom franchises and a $5.7 million increase in payments from the LinkNYC program. Revenue projection from cable television franchise declined by $17 million, and ferry concessions and building permits declined by $2 million and $2.5 million respectively.

Charges for services declined by a net $22 million. This was primarily due to a projected $17 million decline in revenues from fire inspection fees and a decline in projected revenues from NYPD towing operations of $9 million due to the closing of the Manhattan Tow Pound in Pier 76. Projected revenues from fees associated with the 421-A Housing Program increased by $12 million.

Estimated revenues from fines and forfeitures increased by a net $28 million. This includes increases of $15 million in projected revenues from penalties related to late filling of Property Income and Expense (“RPIE”) statement, $15 million in bus lane camera fines and $4.5 million is speed camera fines. Projected court fines, Taxi and Limousine stipulation/settlement fines and health tribunal fines decreased by a combined $7.2 million. Estimated revenues for the category “other miscellaneous”, which comprises mostly non-recurring revenues increased by a net $8 million.

Revisions to the outyear miscellaneous revenue forecasts reflect primarily upward revisions to projected interest income to account for expected rises in short-term interest rates. Total miscellaneous revenue is projected to remain stable, averaging $5.2 billion annually in FYs 2023-2026.

Based on collection trends and changes in local laws, the Comptroller’s Office expects revenues from fines to be above the City’s forecast by $60 million in FY 2022, $29 million in FY 2023 and $26 million in each of FYs 2024-2026. These additional revenues result from the Comptroller’s Office projections for Environmental Control Board (ECB) fines (from the DOF collection unit), RPIE late penalties, as well as parking violation and camera fines. In addition, based on current interest rate forecasts, the Comptroller’s Office projects interest income will be above the City’s projection by $14 million in FY 2023, $45 million in FY 2024, $33 million in FY 2025 and $36 million in FY 2026. The Comptroller’s Office is also monitoring revenues from the contract with JC Decaux for the operation of the City’s bus stop shelters. The company has already missed two quarterly payments this fiscal year for a total of $30 million.

Federal and State Aid

The February Financial Plan projects total Federal and State aid of $35.55 billion (including unrestricted aid) in FY 2022, supporting over 33 percent of the City’s expenditure budget. Compared with the November Plan, the City has reflected an increase of $2.02 billion in the current year comprising of $1.79 billion in Federal aid and $224 million in State grants.

The increased Federal funding predominantly stems from continued recognition of COVID-related grants totaling about $1.66 billion. This includes $1.04 billion in Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reimbursement mainly for costs associated with test kits, vaccinations and testing and tracing activities. The City also recognizes $319 million in other stimulus funding that includes $152 million in Emergency Solutions Grant under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) for homeless assistance and prevention, $94 million in American Rescue Plan Act-State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (ARPA-SLFRF) for a variety of programs (more than half of which are for vaccine booster incentives and 311 personnel) and $51 million in ARPA transit funding mainly in support of Staten Island Ferry operations. In addition, the City has reflected $294 million in unrestricted aid funded with ARPA grants. According to the City, the $294 million stems from ARPA SLFRF-eligible spending that occurred in FY 2021 but were covered by other funding sources, hence making these receipts available as unrestricted aid in the current year.

The February Plan increases bring the total Federal stimulus funding anticipated by the City to $16.29 billion in FY 2022-FY 2026, as shown in Table 18. The largest component is the $6.70 billion in combined ARPA and Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSAA) education funding incorporated into the DOE budget, followed by $4.60 billion in ARPA-SLFRF and $3.29 billion in FEMA grants (including unrestricted aid) currently reflected in the February Plan. Together, these three major funding sources constitute nearly 90 percent of the Federal COVID stimulus funding assumed in the Plan.

Table 18. Projected Federal COVID Stimulus Funding

February 2022 Plan

| ($ in millions) | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | Total |

| ARPA-SLFRF | $3,335.9 | $287.9 | $225.9 | $451.9 | $0.0 | $4,301.6 |

| ARPA-CRRSAA Education | 3,018.2 | 1,771.3 | 1,383.9 | 529.8 | 0.0 | 6,703.2 |

| FEMA | 2,536.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2,541.0 |

| Coronavirus Relief Fund | 194.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 194.4 |

| Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity Grants | 461.9 | 101.3 | 6.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 569.2 |

| All Other | 657.1 | 168.9 | 56.9 | 41.8 | 7.1 | 931.8 |

| Subtotal | $10,203.5 | $2,333.4 | $1,673.7 | $1,023.5 | $7.1 | $15,241.2 |

| Unrestricted Aid-FEMA | $750.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 | $750.0 |

| Unrestricted Aid-ARPA SLFRF | 294.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 294.0 |

| Subtotal | $1,044.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 | $0.0 | $1,044.0 |

| Grand Total | $11,247.5 | $2,333.4 | $1,673.7 | $1,023.5 | $7.1 | $16,285.2 |

Source: NYC Office of Management and Budget.

Under State grants, the majority of the February Modification increase is in education, comprising of charter supplemental tuition aid ($80 million), charter lease aid ($55 million) and pre-k administration grant ($55 million). An additional $35 million has been reflected in other areas mainly for social services, criminal justice and Board of Election programs.

In the FY 2023 Preliminary Budget, the City assumes $25.8 billion in Federal and State assistance, reflecting a modest increase of $106 million since the November Plan. The increase includes $46 million for the second installment of stimulus transit funding mainly for the Staten Island Ferry and $51 million in Homeland Security grants. Compared to the current fiscal year, Federal and State support of the expense budget would fall to 26 percent in FY 2023 as stimulus funding declines by nearly $9 billion year-over-year. Moreover, following the strong growth in State education aid in FY 2022, the City anticipates more modest growth over the Financial Plan. State aid is expected to grow at an annual rate of 0.7 percent, increasing from $16.5 billion in FY 2022 to $16.9 billion in FY 2026. Over the remainder of the Plan, Federal and State grants are projected to fall sequentially to $25.3 billion in FY 2024 and $24.8 billion in FY 2025 before reaching $23.8 billion in FY 2026, essentially mirroring the trend in stimulus funding in the latter years of the Plan.

State Executive Budget

On January 18th, Governor Hochul proposed a budget for the state fiscal year that begins on April 1st. As proposed, the state fiscal year (SFY) 2023 budget would have a negative net impact on the City’s Financial Plan of $114 million over the remainder of the current year, including $50 million in lost City sales tax revenue due to the extension of a temporary intercept, and a modest positive net impact in FY 2023 (Table 19).

For the first time in modern history, New York State forecasts baseline surpluses in every year of its financial plan, including a $5 billion surplus in the current year. Federal stimulus funds combined with higher-than-expected tax revenue, boosted by tax rate increases last year, have allowed the Governor to propose new spending programs while also committing to higher state reserve levels.

Under the Governor’s Executive Budget, the State would provide $2.2 billion in property tax relief for homeowners, $1 billion for healthcare worker bonuses, and an additional $350 million for tax relief to small businesses and an additional $100 million for New York City theaters and music venues. The Governor also set aside $2 billion in pandemic recovery funding for the Legislature to allocate.

However, the proposed State budget would also permanently extend the Distressed Provider Relief Fund, which intercepts $200 million in annual sales tax revenue from New York City and $50 million from other counties to support financially distressed healthcare facilities throughout the State. The original intercept was adopted in 2020 and was scheduled to expire this fiscal year. Similarly, the State Executive Budget proposes to permanently require the Office of the Manhattan District Attorney to annually transfer $40 million of revenue from deferred prosecution agreements to the Criminal Justice Discovery Compensation Fund to help fund statewide compliance with discovery laws.

Table 19. Potential Impact of Proposed FY 2023 State Budget

| ($ in millions) | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | Total Two-Year Impact |

| Formula-based School Aid | ($68) | $60 | ($8) |

| Other Positive Spending Impacts | $29 | $194 | $224 |

| Maintain child care market rate | $0 | $48 | $48 |

| Increase adoption support | $0 | $26 | $26 |

| Increase General Public Health Works | $3 | $14 | $16 |

| Increase transit operating aid | $11 | $45 | $57 |

| Increase other transportation aid | $15 | $62 | $77 |

| Other Negative Spending Impacts | ($15) | ($59) | ($73) |

| Changes to Public Assistance benefits | ($8) | ($32) | ($39) |

| Special education schools COLA | ($7) | ($27) | ($34) |

| Revenue Impacts | ($60) | ($192) | ($252) |

| Sales tax intercept | ($50) | ($200) | ($250) |

| Modernize tax law for vacation rentals | $0 | $28 | $28 |

| Small business tax relief | ($10) | ($20) | ($30) |

| Total Net Impact | ($114) | $3 | ($109) |

Source: NYS Division of Budget and NYC Office of Management and Budget

School Aid

The Governor’s proposed budget maintains the State’s commitment to fully fund Foundation Aid in FY 2024. Formula-based aid to the City would increase 4.5 percent from $11.8 billion to $12.3 billion, including a $345.9 million increase in Foundation Aid. Expense-based aids, including transportation aid and building aid, would be fully funded and increase by $185 million.

Outside of the budget, the State authorized an 11 percent cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) for special education provider rates. The City is responsible for 40 percent of the increase, at an estimated cost of $27 million in FY 2023. The Executive Budget also includes $100 million to address student learning loss and mental health to be provided over two years through the Recover from COVID School Program. Districts would be required to match State grants with their Federal pandemic relief funds.

The Executive Budget would also require all new school bus purchases or leases to be zero-emissions by July 1, 2027. The mandate would expand to all school busses on the road by July 1, 2035, closely mirroring New York City legislation that requires all school buses in use to be electric zero-emission by September 1, 2035.[9] The City would be able to claim transportation aid for zero-emission bus charging or hydrogen fueling stations, and school districts would be allowed to lease or finance zero-emission buses over a period of 10 years, rather than the current five years for diesel buses.

Other Executive Budget Proposals

The Governor’s budget would also replace existing 421a (“Affordable New York”) tax credits with a new incentive program. The proposed “Affordable Neighborhoods for New Yorkers” program would maintain the general structure of the old program but expand requirements for affordable housing. Other housing proposals in the State budget include allowing New York City to legalize existing accessory dwelling units (ADUs) on owner-occupied residential lots, repealing the maximum density of residential floor area ratio (FAR) in the City, and implementing new programs to encourage hotel and office space conversions in the City.

The Executive Budget would also increase State aid for public health and transportation, while enhancing and accelerating the provision of public assistance benefits at an estimated cost to New York City of $31.6 million in FY 2023. New costs would be offset by an estimated $28 million in FY 2023 by subjecting vacation rentals to the City’s hotel fee revenue and requiring vacation rental marketplace providers, such as AirBnB, to collect and remit sales taxes.

The Governor’s budget also includes proposals to extend design-build authority for certain New York City agencies for five years through December 31, 2027 and extend mayoral control of city schools for four years.

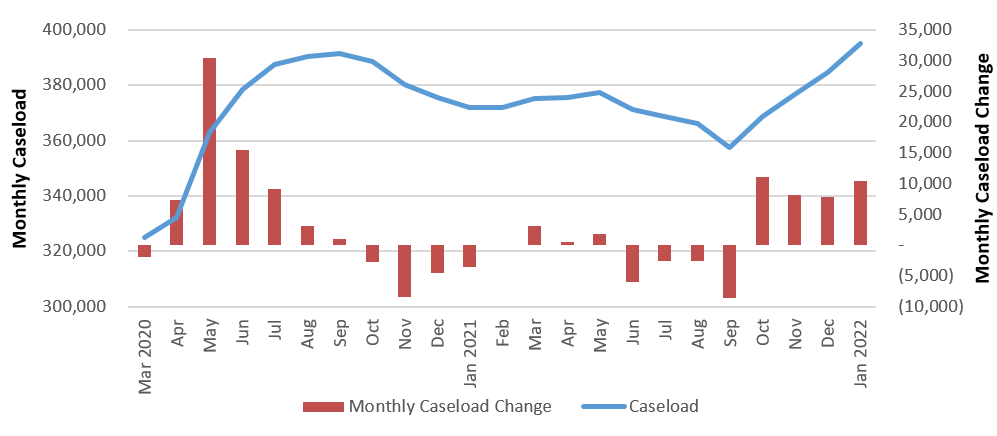

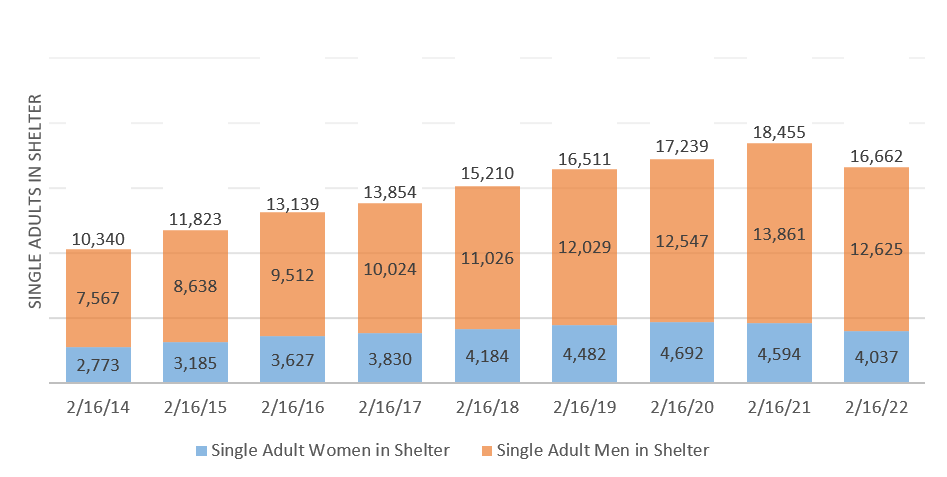

Expenditures Analysis

Total-funds FY 2023 expenditures in the February Financial Plan are projected to drop by $8.0 billion from FY 2022. Both FY 2022 and FY 2023 expenditures include prepayments which lower debt service expenditures in these fiscal years. In addition, FY 2022 expenditures are reduced by the use of FY 2021 resources to prepay part of retiree health insurance costs. FY 2022 expenditures are also further reduced by the take-down of the general reserve and the re-estimates of prior-year accruals. After adjusting for prepayments, and excluding re-estimates of prior-year accruals and reserves, expenditures are projected to drop by a smaller $7.60 billion to $100.96 billion, as shown in Table 20. However, the FY 2022 budget includes $8.55 billion of COVID-19 related expenditures which are expected to drop to $1.02 billion in FY 2023. Netting out COVID-19 related spending, expenditures are projected to grow by $880 million in FY 2023.

Table 20. FY 2022 – FY 2026 Expenditure Growth

Adjusted for Prepayments

| ($ in millions) | FY 2022 | FY 2023 | FY 2024 | FY 2025 | FY 2026 | Growth FYs 22-26 |

Annual Growth |