Introduction

Empowering people in prison to earn sentence reductions through vocational, educational, rehabilitative or other self-improvement programs is an effective and safe way to enable individuals to return sooner to their homes and communities, increase individuals’ ability to find gainful employment after prison, and reduce the overall prison population.

However, currently less than 20% of incarcerated people serving time New York facilities managed by the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (DOCCS) can earn merit time off their sentences. New York State lawmakers are considering expanding access to merit-based reductions in prison sentences with the Earned Time Act (S. 342/ A. 1085), which would expand the rights of incarcerated people to reduce their time served for successfully completing educational and other programs. The bill would expand merit time eligibility to all incarcerated people, regardless of charge, up to one quarter of the total for determinate sentences and half for indeterminate sentences. These opportunities have been shown to reduce recidivism after release and violence in prison facilities.[1]

By releasing individuals from prison sooner, and providing skills training and education, the Earned Time Act has the potential to give thousands of people opportunities to return to their communities and to the workforce sooner, yielding economic benefits. Additionally, these sentence reductions could result in significant savings in operating costs. The Comptroller’s office modeled the economic benefits and found:

- 12,000 individuals will earn sentence reductions, gaining, in aggregate, 49,000 years free from prison.

- 6,100 returning individuals will gain employment, earning $494 million in wages over the time they would have been held in prison.

- Training and education will enable an additional 1% of returning individuals to find gainful employment and will boost the annual wages of all workers by $700 on average.

- At an average cost of $115,000 per incarcerated person per year to operate prison facilities, these sentence reductions could enable significant cost savings for the State.

With DOCCS experiencing an acute staffing crisis resulting diminished quality of life for staff and incarcerated individuals alike, now is the time to consider ways to safely reduce the prison population and bring New York in line with states across the country who recognize the importance of rehabilitation in incarceration.

New York legislators should pass the Earned Time Act to provide benefits to incarcerated individuals, their communities, and the State.

The Earned Time Act

The Earned Time Act (the Act) expands eligibility for good and merit time to all people incarcerated with less than a life sentence regardless of conviction. The Act also increases the amount of time that incarcerated individuals may earn.

New York State Law currently allows incarcerated individuals to accrue time off their sentence for good behavior or for completing personal enrichment program, called “good time” and “merit time” respectively. Merit time can be earned for completing a GED, higher educational or vocational training program, for obtaining an alcohol or substance abuse treatment certificate, or for participating in at least 400 hours of community service. In order to receive credit for merit or good time, incarcerated individuals must appear before a parole board for consideration and receive an Earned Eligibility Certificate at the discretion of the board. Currently, merit time is only available to people serving sentences for non-violent or drug-related crimes, which equates to less than 20% of the total incarcerated population as of 2025.

The Earned Time Act makes all incarcerated individuals eligible for merit time, regardless of charge. Instead of requiring an inmate to appear before the Parole Board and make the case that they have earned the time, the benefit is given automatically unless prison officials present evidence that the time should not be granted at a hearing. Available earned time is expanded for both determinate sentences (where a single time served is imposed), and indeterminate sentences (where incarcerated individuals serve a range of time dependent on the decision of the Board of Parole). The expanded merit time allowance enables individuals serving determinate sentences to reduce their sentences by one quarter upon completion of designated programming – up from one seventh under current law. Those serving indeterminate sentences reduce their sentences by one half of the minimum sentence. Good behavior time allowances are also expanded, to one half or a determinate sentence or one half the maximum of an indeterminate sentence.

There are measurable benefits to early release. A 2023 meta-analysis reviewing dozens of prison education programs found this programming increases the portion of people employed after release by 1 percentage point and increases their average annual earnings by $700.[2] There are benefits to the prison system, as people who are meaningfully incentivized to pursue self-improvement are less violent in prison, and are 7.5 percentage points less likely to return to prison within three years.[3]

The Comptroller’s Office modeled the potential impacts of this legislation, both in direct expenditures by state government and in broader economic impacts of accelerated release.

Economic Benefits of the Earned Time Act

The Comptroller’s Office estimates individuals earning early release will earn $494 million in wages over the time they would have been incarcerated. This benefit includes:

- Incarcerated individuals returning home from prison sooner and working and earning in their communities.

- The education and skills training provided through the prison education programs, which will allow more people to find employment and boost wages.

- The reduction in recidivism that comes with additional education.

This estimate is based on the DOCCS prison population as of October 2025, apportioned by conviction type (violent, non-violent, or drug-related charges) and sentence length. The model factors a 46% rate of participation in merit time programming (based on observed participation) and an improved non-recidivism rate of 67% (Additional details of the model and data sources are provided below.)

Under this model, the 11,958 individuals would receive more than 49,000 total years free from prison. The typical person would gain 3 years free; 10,200 individuals would earn more than one year.

This model is based only on the proposed expansions of merit time. Expansions to the amount of good behavior time would add additional time beyond what is modeled here.

The largest portion of the economic benefit is from individuals being able to return to productive society sooner. This analysis first estimated this impact by multiplying the total years of early release by the portion of individuals typically gainfully employed after prison and the average earnings of those employed workers.[4] In this baseline model, 6,000 individuals will be employed and earn $469 million over the time they would have been in prison.

Next, the model estimated the additional economic benefit from the training and education individuals could receive through universal merit time programming, adding to the baseline estimate of individuals employed the additional number of people who would be able to find work, and applying to all workers the typical boost to earnings from increased education or training. These education benefits increase the number of estimated employed workers to 6,100 and add $26 million in income, bringing the total earnings to nearly $494 million.

Individuals released from prison under the Merit Time program are 7.5 percentage points less likely to have returned to prison within three years.[5] For this exercise, our model estimates the number of additional years free that could result from Earned Time Act programming for individuals who do not repeat offend. This reduction in recidivism accounts for 4,300 years and $41 million of the baseline earnings, or $44 million of the earnings with education benefits cited above.

| Individuals earning merit time | 11,958 |

| Total time earned | 49,112 years |

| Total baseline earnings in time earned | $469 million |

| Total earnings including education benefits | $494 million |

| Benefits from education | $26 million |

| Benefits from reduced recidivism (included in total above) | $44 million |

Fiscal benefits

In addition to the benefits that accrue directly to formerly incarcerated individuals and the economic gains in their communities, New York State could face a reduced fiscal burden when more incarcerated individuals are released sooner. As of 2021, the State spends about $115,000 per incarcerated individuals on an annual basis.[6] The DOCCS operations budget in Fiscal Year 2026 is $3.3 billion, the majority of which is directed to supervision of incarcerated individuals.

Fully realizing operational savings would depend on consolidating facilities. But the long-term cost savings from reducing sentences, thus reducing the prison population and the number of needed prison beds and correction posts, would be significant.

Fiscal costs

The Earned Time Act has no direct fiscal implications for New York State.[7] Providing additional education and programming to allow incarcerated individuals to earn time can be provided at little cost to the State. College education, the most expensive educational offering, is financed through federal Pell grants and other private funds, without a cost to New York State.[8] Basic and secondary education is less costly and could be delivered within DOCCS’ existing budget.

Conclusion

New York has been slow to acknowledge the power that rehabilitative programs can have on incarcerated people, lagging behind a diverse set of states that have broader access to good and merit time with demonstrable results.[9] Because the evidence strongly supports the idea that merit and good time programs reduce violence in prison, increase labor force participation, and decrease recidivism, there are good reasons for the state to take this step towards meaningful reform and create a more effective, just prison system.

Data & methodology

This model uses data on the number of individuals currently in DOCCS prisons, estimates the reductions in sentences under the Earned Time Act, and aggregates employment, earnings, and fiscal savings over that total time free from prison.

Sentence reduction

Two DOCCS data sources were combined at the prison facility level to apportion and aggregate individuals’ eligible reduced time under the Earned Time Act.

- DOCCS’ Incarcerated Profile Report data lists the number of individuals in each prison facility by minimum and maximum sentence lengths (in several sentence length groups, from less than 18 months to more than 20 years).[10]

- DOCCS data list the number of individuals incarcerated at each facility by charge type.[11] Charges ‘Drug Felony’, ‘Property/Other’, and ‘Youth/Juvenile Offender’ align with those charges under which individuals are now eligible for merit time. From these charge group counts, a rate was computed for each facility of the portion of incarcerated individuals now eligible.

Under the proposed Earned Time Act, individuals serving indeterminate sentences would be able to earn merit time equal to one-half of their minimum sentence. This would be an increase from the current eligibility of one-sixth of minimum sentence for most eligible charges, or one-third for drug charges. The net additional merit time sentence reductions are thus one-half of the minimum indeterminate sentence for individuals serving charges for which they are currently ineligible for earned time; one-sixth for individuals serving under drug charges; or one-third for individuals under other eligible charges. Because of a lack of more granular sentence data, this model treats all individuals as serving on indeterminate sentences and eligible for the earned time allowances for such sentences (This assumption means this model somewhat overstates the time that may be earned, as current law and the Earned Time Act allow more merit time for individuals with indeterminate sentences than determinate sentences.) Only individuals serving sentences of one year or more are eligible for merit time.

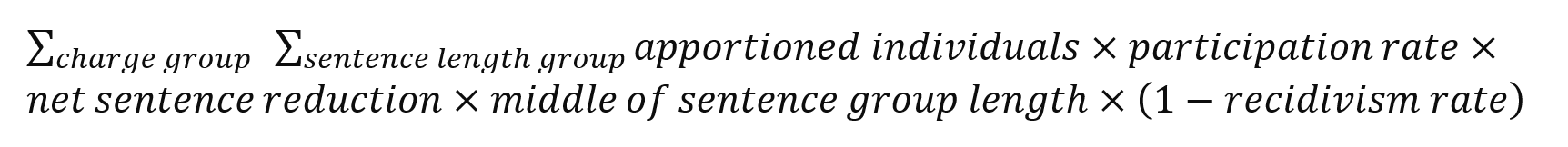

First, using the data on populations by minimum sentences, we subtract the number of individuals with sentences less than 18 months (the shortest category), to get the total eligible individuals at each facility. Then, using the population by charge data, we compute the proportion of individuals in each facility within each charge group (i.e. now-ineligible violent offenses; now-eligible drug charges, and other now-eligible charges). Then we use these by-facility charge proportions to apportion individuals in each sentence length group. Then the apportioned number of individuals in each facility, sentence length, eligibility group was multiplied by the participation rate, multiplied by the net portion of an indeterminate sentence that could be reduced under the Earned Time Act (i.e. one-half for the now-ineligible groups, one-sixth for drug charges, one-third for other charges), multiplied by the number of months for the middle of that sentence group (i.e. 20.5 months for the band 18-23 months). Sentence length groups which would allow a reduction of three years or more were multiplied by the complement of the recidivism rate.

This operation is represented by the formula below:

This estimates the total net time which could be earned under the Earned Time Act reforms by all currently-incarcerated individuals, which approximates the total amount of earned time when the program is fully implemented.

Participation rate

While the Earned Time Act allows all individuals serving to participate, not all individuals will choose to do so, or may not be able to complete the programs because of disciplinary or other issues.

The modeled participation rate of 46% is based on the number of individuals who received merit time hearings as of the most recent year data are available (4,450, in 2006) divided by the number of individuals newly committed on merit-time eligible charges in that year (9,587).[12] This is an indirect and outdated basis for estimating the participation rate, unfortunately more direct data are not available. The Earned Time Act would increase potential gains, and make the benefits more certain for incarcerated individuals, and may expand the merit time programming offered, all of which may increase the portion of individuals making use of this programming. Such an increase in participation would increase the aggregate economic and fiscal benefits above those modeled here.

Recidivism rate

Earned Time Act programming equips individuals in prison to avoid returning to prison by parole violation or new offense and this reduction in recidivism is a key component of the gains in free and productive time.

It is typical to consider the rate of recidivism as the portion of individuals who have returned to prison within three years of release. The measured recidivism rate over the most recent years is artificially low because the pandemic disrupted DOCCS intake and other judicial processes. Therefore, for a baseline recidivism rate, this model looks back to a pre-pandemic rate, using data from DOCCS on the cohort of individuals released in 2016 and their rate of return by 2019.[13] Of this population, 40.6% returned to prison within three years.

Prior research by DOCCS compared the recidivism rates of individuals released early though the merit time program to non-merit time releases. That analysis found the population released through merit time were 7.5 percentage points less likely to return to prison within three years (31.1% for merit time releases; 38.6% for all comparison groups).[14]

From these two empirical sources of data, this analysis models the recidivism rate for individuals released on earned time as 33.1%. For all sentence reductions of three years or more, the total time free is multiplied by the complement of this rate (i.e. 1 minus the recidivism rate, or 66.9%), as a reflection that the individuals who return to prison will not realize their full free time awarded by earned time.

The total free time earned including the improved recidivism rate is subtracted from the alternative model using the existing recidivism rate to determine what gain in free time is from reduced recidivism.

Economic benefit

To compute economic benefit, this total amount of earned time is multiplied by the typical portion of individuals employed on returning from prison and by the average wage of those individuals employed.

Portion of individuals returning from prison employed

There is unfortunately little data available that directly tracks the employment and earnings of individuals leaving prison.

A nationwide report by Brookings Institution used information reported by each state, linked with IRS records, to measure employment and earnings of individuals who were in prison as of 2012 in the years before they were incarcerated and after they were released.[15] That report found that in the year of release, 48% of individuals had any reported earnings. Employment improved slightly in following years: in the first full year after release, 54.5% reported earnings.

This analysis uses a simplified, round, 50% as the baseline portion of individuals employed when returning from prison.

Typical earnings for individuals returning from prison

Because of barriers to employment, lost skills training, and generally low levels of educational attainment, individuals returning from prison typically have low earnings.

The same Brookings Institution report also summarizes earnings for the population who were in prison as of 2012, finding the average annual tax-reported earnings (of those who were employed) at $13,889 in the first full year after incarceration. Inflated from 2014 (the most recent year of data on which that report is based) to 2025 dollars, that amount equates to $19,079.

Education benefits

Increased education opportunities in prison can substantially boost earnings of individuals after incarceration because this population has low levels of educational attainment and literacy. Individuals in prison are 50% more likely than individuals who never go to prison to have earned only a high school degree or less,[16] and 62% of individuals in state prisons had not completed high school (as of 2016).[17]

Education benefits can boost aggregate economic benefits in two ways: individuals who would not otherwise have been employed can find employment (the employment benefit) and workers who are employed can earn on average higher wages (the earnings benefit).

Increased employment with education

A meta-analysis combining the 149 separate estimates from 79 studies of the impact of prison education programs summarized employment benefits by type of education.[18] Adult basic education and secondary education were found to have the slightest impact on employment: the rates of employment for participants in these programs were 0.66 percentage points and 0.54 percentage points higher than those of non-participants, respectively. Vocational programs boosted employment by 2.5 percentage points, and college programs increased employment by 4.7 percentage points.

A meta-analysis[19] found the average odds ratio across 22 studies at 1.13 (signifying participants in education programs are 13% more likely to be employed than those who do not); from that aggregated odds ratio, the study authors compute a 0.9 percentage point increase in the rate of employment for participating individuals.

Increased earnings with education

The meta-analysis reports the average earnings premium from education in prison to be $141 per quarter (in adjusted 2020 dollars). Inflated to 2025, that is equivalent to $699 annually.

Fiscal savings

Fiscal savings of the entire reduction in incarcerated time are estimated as total years of reduced sentences multiplied by the per- incarcerated individuals cost of operating prisons.

Per-incarcerated individual costs of prison facilities

Vera Institute of Justice’s analysis of the DOCCS budget found the cost for operating New York state prisons was $114,831 per incarcerated individual (as of 2021).[20]

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Dan Levine, Senior Data Analyst & Products Manager, and Robert Callahan, Director of Policy Analytics. Thanks to Center for Community Alternatives for information on the Earned Time Act.

Endnotes

[1]https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2019/09/Merit_Time_Through_2006.pdf

[2] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12103-023-09747-3

[3] https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2019/09/Merit_Time_Through_2006.pdf

[4] https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/es_20180314_looneyincarceration_final.pdf; See detailed methodology below.

[5] https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2019/09/Merit_Time_Through_2006.pdf

[6] https://vera-institute.files.svdcdn.com/production/downloads/GJNY_DOCCS-Budget-Explainer_10.25.22.pdf

[7] https://nyassembly.gov/leg/?bn=A01128&term=2023&Memo=Y#:~:text=FISCAL%20IMPLICATIONS%3A-,None,-to%20the%20State

[8] https://doccs.ny.gov/college-programs ; https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2023/10/college-report-2023_final_20231024.pdf

[9]https://www.communitiesnotcagesny.org/our-demands#Earned-Time-Act; https://www.justiceroadmapny.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/CNC-Earned-Time-Act.pdf

[10] DOCCS. Incarcerated Profile Report. October 2025. 2025.10.01-uc-profile.pdf

[11] DOCCS. Security Level and Facility by Crime Group, Under Custody. https://data.ny.gov/Public-Safety/Security-Level-and-Facility-by-Crime-Group-Under-C/7whc-b5e4

[12] https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2019/09/Merit_Time_Through_2006.pdf; https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2019/09/Court_Commitments_2006.pdf

[13] https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2022/10/2016-releases_three-year-post-release-follow-up-final-.pdf

[14] https://doccs.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2019/09/Merit_Time_Through_2006.pdf

[15] https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/es_20180314_looneyincarceration_final.pdf

[16] https://www.mackinac.org/s2024-02

[17] U.S. Department of Justice: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Survey of Prison Inmates. https://spi-data.bjs.ojp.gov/

[18] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12103-023-09747-3

[19] https://bja.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh186/files/Publications/RAND_Correctional-Education-Meta-Analysis.pdf

[20] https://vera-institute.files.svdcdn.com/production/downloads/GJNY_DOCCS-Budget-Explainer_10.25.22.pdf