Inside the Gender Wage Gap, Part I: Earnings of Black Women in New York City

Equal Pay Day, commemorated on April 10th this year, marks the symbolic day that women’s earnings catch up to what men made during the previous calendar year. However, this date, derived from comparing the median earnings of all full-time working women and men, obscures that women are not all equally disadvantaged when it comes to pay inequality. In fact, a closer look at the data reveals that nearly all women of color face larger disparities in earnings and therefore have to work longer into the year to make what white, non-Hispanic men are paid in a single year. In 2018, Black Women’s Equal Pay Day is not observed until August 7th – more than seven months into the calendar.

Equal pay for equal work is a concept as old as labor organizing and remains elusive today, more so for women of color. While the Equal Pay Act of 1963 officially prohibited gender-based wage discrimination, it was not until the passage of the Civil Rights Act the following year that race became a protected class. That women of color experience discrimination at work on the basis of both sex and race—and that it is precisely the intersection of marginalized identities that compounds economic disparities—has long been sidelined in prevailing conversations about equal pay, especially at the national level.

New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer’s April 2018 report Power and the Gender Wage Gap: How Pay Disparities Differ by Race and Occupation in New York City showed that while women make less on average than men in New York City, the gender wage gap is significantly larger for women of color.[i] In this policy brief, the first in a series on the economic experiences of women of color, the Comptroller’s Office further analyzes U.S. Census Bureau earnings data to examine the scale and impact of the gender wage gap specifically for Black women in New York City. Annual data from 2010 to 2016, the latest year available, are analyzed.[ii] Findings detailed in the brief include:

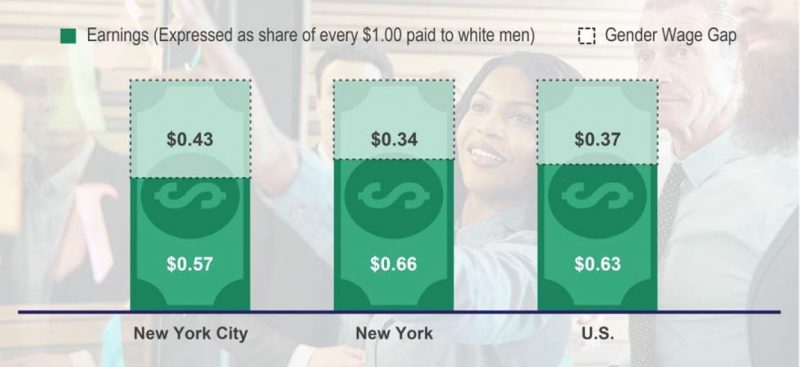

- In 2016, Black women working full-time in New York City made 57 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men—roughly $32,000 less on average.

- The wage gap for Black women in New York City is larger than for Black women in New York and the U.S.—43 cents compared to 34 cents and 37 cents, respectively. If New York City were to observe its own local Black Women’s Equal Pay Day, it would be October 3rd, a full nine months into the year.

- Over a 40-year career, the median full-time working Black woman in New York City would lose on average over $1,274,000 in earnings due to the gender wage gap. She would have to work an additional 30 years to attain the same earnings as her white, male counterpart.

- If the gender wage gap were closed, the more than 350,000 Black women working full-time, year-round in New York City in 2016 would have collectively contributed around $11.2 billion more in earnings to the local economy.

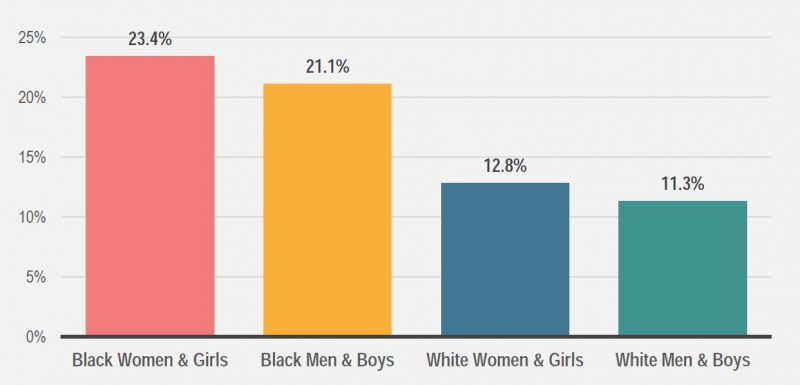

- In 2016, nearly one in four (23.4 percent) Black women and girls in New York City lived in poverty, more than twice the rate among white men and boys (11.3 percent) and nearly twice the rate among white women and girls (12.8 percent).

- Between 2010 and 2016, the growth in attainment of bachelor’s and graduate degrees among Black women outpaced that of women across racial and ethnic groups; the proportion of Black women 25-years-old or older with a bachelor’s degree or higher grew 14.5 percent during that time, compared to 9.0 percent for white men.

More than 55 years after passage of the first federal labor law recognizing the harms of wage discrimination on women, wage disparities clearly persist.[iii] But data on earnings capture only part of the story of economic inequality for Black women. The Comptroller’s analysis also finds that Black women are more than three times as likely as white men to work in lower-paying service occupations. And while Black women have the highest labor force participation rate among women of color in the city, they also have the highest unemployment rate. This remains the case despite the fact that attainment of bachelor’s and graduate degrees is rising faster among Black women than nearly every other racial and ethnic group in the city.

The Comptroller’s analysis and Black women’s lived experiences make clear that more work needs to be done to combat structural and social barriers to equal pay. As long as the wage gap persists, the economic security of Black women—and, indeed, the economic health of the city—will be compromised. The gender wage gap not only harms individual Black women and their families, limiting their ability to afford housing and other necessities, pay down debt, and build savings for the future, it also reinforces generational disparities in wealth and constrains economic activity in communities across the city. City government, employers, and community stakeholders can and must do more to close the gap. To that end, this brief concludes with a set of recommendations that will help to achieve pay equity and, ultimately, greater economic security for Black women in the city.

Black Women’s Earnings and the Gender Wage Gap

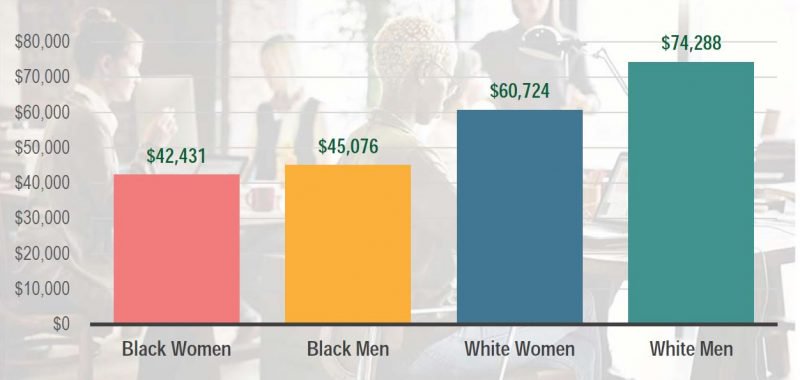

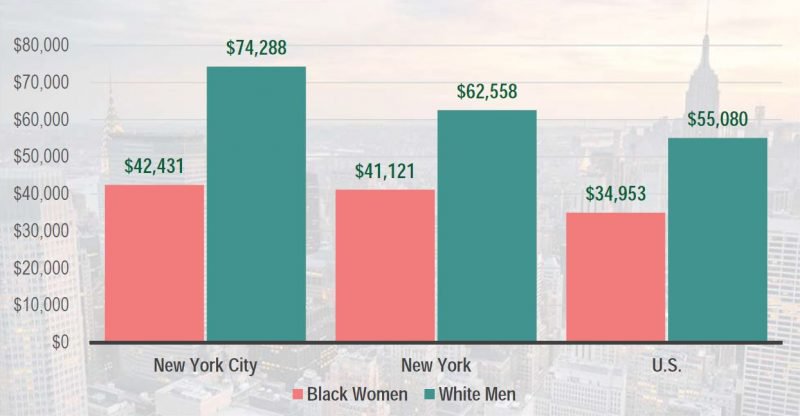

Black women comprise 12.8 percent of the overall labor force in New York City, including more than one in four (26.2 percent) women. Yet, Black women’s median earnings have historically lagged behind the earnings of women and men across racial and ethnic groups. In 2016, the median earnings of Black women who worked full-time, year-round were $42,431, which represented an increase of 9.7 percent from 2010. White men’s median earnings increased 11.1 percent over the same time period, rising from $66,887 to $74,288 annually.

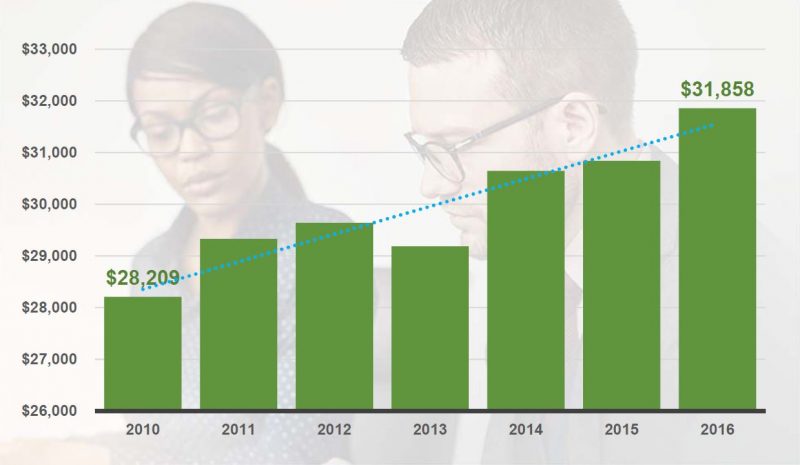

The gender wage gap, expressed as the difference between the median earnings of Black women and white, non-Hispanic men, has gradually increased over time, growing from 42 percent in 2010 to 43 percent in 2016, or from a difference of about $28,000 annually to about $32,000 annually (Chart 1). Put another way, Black women in New York City currently make 57 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men. By comparison, white women make 82 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic men.

Chart 1: Difference in Black Women’s & White Men’s Median Earnings in New York City

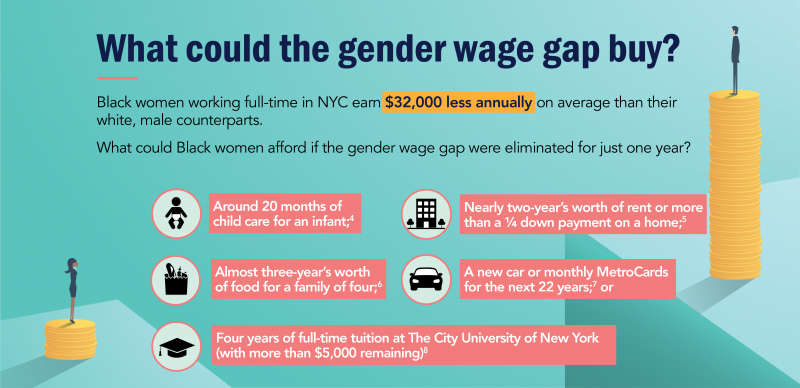

If the gender wage gap were eliminated, meaning that the median full-time working Black woman had earnings equal to the median full-time working white man, Black women working full-time in New York City would have cumulatively earned nearly $210,000 more on average between 2010 and 2016. In 2016 alone, Black women would have earned roughly $32,000 more.

With the current gender wage gap in New York City, Black women stand to lose more than $1,274,000 over a 40-year career in wages alone, on top of foregone retirement savings, investments, and benefits. Given that women are more likely than men to take time away from the workforce to provide care for children, aging parents, or ill relatives, this likely understates the extent of the earnings differentials over time.[ix]

While these losses are deeply felt at an individual and family level, undermining the financial security of Black families across the five boroughs, they also limit economic activity in the city. If the gender wage gap were closed, the more than 350,000 Black women working full-time, year-round in 2016 would have collectively contributed $11.2 billion more in earnings to the local economy.

Comparing the median earnings of women of different racial and ethnic groups to those of white, non-Hispanic men underscores that women are not all similarly situated when it comes to the gender wage gap. Indeed, the fact that Black women’s median earnings are much closer to Black men’s median earnings than to white women’s further points to the role of race, and anti-Black racism, in perpetuating economic disparities (Chart 2). Black women make on average 70 cents for every dollar paid to white, non-Hispanic women but 94 cents for every dollar paid to Black men.

Chart 2: Median Earnings for Full-Time Work in New York City (2016)

Nationally, Black women’s earnings are lower than white men’s. However, the Comptroller’s analysis found the wage gap in New York City is more pronounced than at the state and national levels, where Black women experience a wage gap of 34 cents and 37 cents, respectively (Chart 3). This is explained largely by the higher earnings of white men in New York City relative to the state and national averages (Chart 4). Moreover, while the gender wage gap has slightly worsened for Black women in New York City since the beginning of the decade, it has remained largely stagnant in New York and has marginally improved at the national level, due to white men’s median earnings increasing by a smaller percentage than Black women’s median earnings.

Chart 3: Gender Wage Gap for Black Women in New York City is Higher than State and National Averages

Chart 4: Median Earnings of Black Women and White Men in New York City (2016)

Nationally, Black Women’s Equal Pay Day—the symbolic day that Black women’s earnings catch up to what white, non-Hispanic men made during the previous calendar year—is August 7th, 2018. However, considering the larger pay disparities Black women across the boroughs face, in New York City, Black women will not catch up to what white men made until October 3rd, a full nine months into the year. Were the gender wage gap to hold steady over a 40-year career, the typical Black woman would have to work an additional 30 years to attain the same earnings as her white, male counterpart.

Occupational Segregation

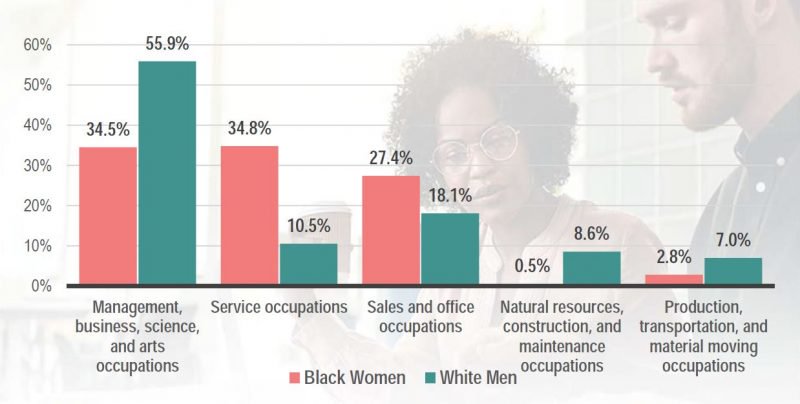

A root cause of the gender wage gap in New York City is that Black women are underrepresented in higher-paying occupations, including finance, law, and engineering, and overrepresented in lower-paying service and sales occupations. While more than half (55.9 percent) of white men work in the category of management, business, science, and arts occupations, only about one-third (34.5 percent) of Black women do. As Chart 5 shows, Black women are more than three times as likely as white men to work in service occupations, such as food service and personal care, and they are also more likely to be concentrated in sales jobs. These service and retail sales jobs tend to be among the less stable, offer lower wages and fewer hours, and provide less room for advancement, which all contribute toward greater economic insecurity for Black women.[x]

Chart 5: Proportion of Black Women & White Men by Occupation (2016)

Since 2010, the proportion of Black women working in management and service occupations has increased, up 4.1 and 3.2 percent, respectively, while the proportion of Black women working in sales and office occupations has steadily decreased over time (down 7.9 percent since 2010). As Baby Boomers retire and age, service jobs, in particular home health aides, will continue to be in high demand, but without corresponding wage growth, these jobs will continue to disproportionately jeopardize the economic wellbeing of Black women.[xi] Ultimately, closing the gender wage gap will not only require boosting wages of service-sector work and increasing the number of Black women in higher-paying fields such as finance and engineering but also addressing inequities that exist in senior-level and managerial roles. In New York City, Black women financial managers make a mere 39 cents for every dollar paid to white male financial managers, proving that entry to more lucrative fields and positions does not equate to equal pay.[xii]

Educational Attainment

Differences in educational attainment also contribute to the gender wage gap in New York City. While one in four (25.0 percent) Black women 25 and older in New York City have attained a bachelor’s degree or higher, more than half (56.6 percent) of white, non-Hispanic men have. These disparities reflect the fact that Black women and white men have on average different access to and opportunities for quality education, beginning at birth.[xiii]

Even so, far more Black women are earning college degrees now than in 2010, when about one in five (21.9 percent) Black women had completed at least a bachelor’s degree. As Chart 6 shows, since 2010, the growth in attainment of bachelor’s and graduate degrees among Black women (14.5 percent) has outpaced that of most other groups in the city, including white men (9.0 percent). This largely aligns with the landscape at the national level as well.[xiv] Although access to higher education does not guarantee access to higher earnings or to a job, more education should on average lead to better earnings and job prospects—opportunities that remain disproportionately inaccessible to Black women despite these higher college completion rates.

Chart 6: Percent Change in Proportion of New Yorkers 25+ Attaining Bachelor’s Degrees or Higher, 2010-2016

One reason why Black women’s achievement in higher education has not yet translated to higher earnings relative to white men likely relates back to occupational segregation. Existing research has established that Black women are underrepresented in fields of study such as STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) that are entry points to more lucrative occupations, such as software developers, mathematicians, and information security analysts, jobs in which there is also expected to be significant growth over the next decade.[xv]

Labor Force Participation and Unemployment

In New York City, six in ten (60.3 percent) Black women over 16-years-old are in the labor force.[xvi] Their labor force participation rate, the highest among women of color, is just slightly lower than white women (60.5 percent). However, at 11.4 percent, the unemployment rate among Black women exceeds that of women across racial and ethnic groups. As Chart 7 shows, the unemployment rate among Black women is more than twice the rate among white women (5.2 percent) and white men (5.6 percent).

Chart 7: Unemployment Rate (2016)

That Black and white women participate in the labor force at similar rates but experience far different levels of unemployment reinforces that Black women face additional barriers to stable employment. This may be partly due to differences in work histories and education, which, as noted above, impact Black women’s employment prospects. However, Black women are also more likely than white women to be primary earners, and therefore more likely to remain connected to the labor force out of economic necessity. To the extent that women in New York City leave the workforce in order to better negotiate family needs, Black women are less likely to be able to do so. Additionally, anti-Black employment discrimination has long played a role in the high rate of unemployment among Black women and men relative to white women and men; a recent study found that discrimination against Black applicants in hiring has remained steady over the last two decades.[xvii]

Poverty and Inequality

Although Black women in New York City are making more money on average now than at the start of this decade, the Comptroller’s Office finds that poverty rates among Black women and girls have also increased. In 2016, nearly one in four (23.4 percent) Black women and girls in New York City lived in poverty, reflecting a 3.8 percent increase from 2010. This is more than twice the rate among white men and boys (11.3 percent) and nearly twice the rate among white women and girls (12.8 percent) (Chart 8). Among the largest racial and ethnic groups, only Latinx New Yorkers experience poverty at higher rates.

Chart 8: Poverty Rate (2016)

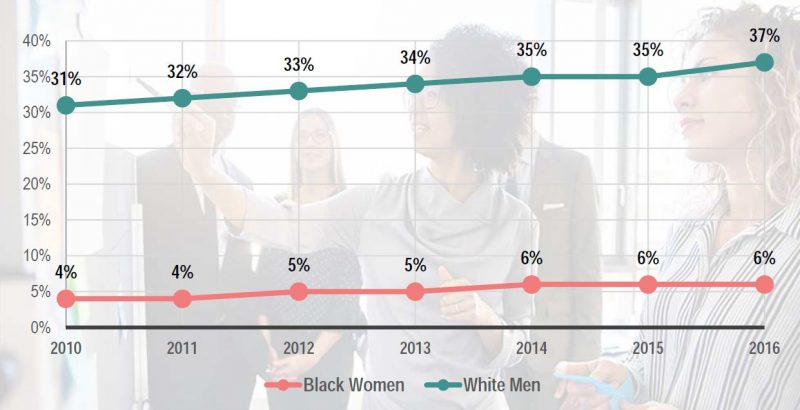

At the same time as poverty has increased, the proportion of Black women earning $100,000 or more has increased 50 percent since 2010. However, these higher earners remain a relatively small percentage of Black women workers overall. In 2016, only 6 percent of Black women working full-time in New York City earned $100,000 or more, compared to 37 percent of white men (Chart 9).

Chart 9: Proportion of Full-time Workers in NYC, by Gender and Race, with Earnings of $100,000 or more

Causes and Impacts of Economic Disparities

The causes of economic disparities are many and interconnected. Structural barriers, including uneven access to quality education and child care, inflexible hours, inadequate accommodations for pregnant and nursing mothers, and exclusionary hiring and performance evaluation processes, all contribute to women remaining in more junior and lower-paying roles, if not getting pushed out of the formal workforce altogether. Social barriers—including entrenched expectations around who is ‘right’ for a certain job, who should study certain subjects, or what value is assigned to certain work—contribute to occupational segregation and keep Black women concentrated in low-wage sectors.[xviii] All of these barriers are rooted in historical inequities that have made Black women historically poor relative to white men.[xix]

While differences in education and occupation likely account for a significant portion of the wage disparities observed in New York City, existing research confirms that a gender wage gap remains in their absence. Specifically, controlling for occupation, as the Comptroller’s April 2018 analysis did for instance, revealed gaps as large as 61 cents on the dollar.[xx] A model that economists Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn developed to disaggregate the causes of the gender wage gap in the U.S. concluded that 38 percent of the gap in women’s and men’s earnings cannot be explained by observable differences, such as work experience, and must be attributed to “unexplained factors.”[xxi] These unexplained factors include different negotiating styles, as well as unconscious bias and overt discrimination.

Although there is no precise way to measure how much gender- and race-based discrimination contributes to economic insecurities among Black women in New York City, institutionalized sexism and racism have undoubtedly reinforced and reproduced them over time, often in insidious ways. To the extent that power structures have served to keep Black women disempowered, they have also prohibited many from coming forward to report the discrimination they face. The pathways, both perceived and actual, that are available to Black women to even discuss wage disparities can be further limited by their immigration status, as well as gender identity, sexual orientation, disability, and religion.

The good news is that the gender wage gap is not inevitable. The bad news is that it persists, with harmful, widespread, and long-lasting consequences. Pay disparities equate to unequal spending power, compromising Black women’s ability to accumulate wealth. And the effects compound over women’s lifetimes and across generations, impacting women’s capacity to pay down debt, build retirement savings, contribute to their children’s education, and access the kinds of opportunities that all New Yorkers hope to provide for themselves and their families. The well-established gender gap in unpaid labor, which includes hours spent providing informal care, heightens these economic harms and creates a doubly uneven playing field for women, especially women of color.[xxii]

Eliminating the gender wage gap would surely have a positive impact on a host of economic, social, and health outcomes associated with economic insecurity, including the relatively high maternal mortality rate among Black women, rates of domestic violence and assault, and prevalence of obesity, among others. In New York City, as across the country, Black women are overrepresented among all women-headed households, and families rely heavily on their income.[xxiii] Closing the gap in earnings between Black women and white men, then, would have a cumulative effect, helping to reduce poverty rates among children and improving child outcomes associated with living in or near poverty over time.

Realizing Economic Justice for all Black Women

This brief shows that, despite vast contributions to the city, great attachment to the labor force, and high achievement in education, Black women face striking, persistent disparities in earnings and other indicators of economic well-being, including high rates of unemployment and poverty. In recent years, policy developments to raise the minimum wage and to improve access to work supports such as paid sick and family leave have been significant steps in the right direction, but the Comptroller’s analysis—and Black women’s lived experiences—make clear that additional solutions are needed.

What would an economic justice policy agenda inclusive of Black women look like? The four overarching recommendations below offer a starting point, but it will take concerted, proactive work between government, employers, educators, and community leaders to begin to address the structural racism and sexism underlying existing disparities. Moreover, Black women are not a homogenous group, so this work must be attentive to intragroup differences and careful not to reproduce the same exclusionary practices that have perpetuated inequalities among women across race.

To help address these inequities and close existing pay gaps, this brief recommends the following:

- Guarantee access to family-sustaining wages: Although the minimum wage will reach $15 per hour in New York City by the end of 2018, Black women are concentrated in jobs in which the minimum wage is too often the ceiling, rather than the floor. The City and State should promote additional strategies to raise wages, strengthen protections, and address the devaluing of jobs in which women are overrepresented. This includes supporting existing campaigns to increase and enhance the Earned Income Tax Credit and to boost the wages of New York City’s early childhood educators, the majority of whom are women.[xxiv] It also includes increasing access to and protecting the collective bargaining process. Existing research shows that the gender wage gap narrows for women in unions, but especially for Black women.[xxv]

- Expand and create equitable access to affordable child care and paid leave: Greater access to resources like child care as well as paid time off to care for loved ones would help Black women remain connected to the workforce and advance in their careers. Strategies to do so include expanding access to subsidized child care, including for women who work nontraditional hours such as nights and weekends, typical of service-sector jobs. And while most private employers in New York City are now required to provide earned paid sick leave and paid family leave to their employees, improvements can be made. For example, a private right of action for paid sick leave would enhance enforcement. In addition, paid parental leave should be extended to all municipal workers, tens of thousands of whom, overwhelmingly women of color, still lack access to leave following the birth or adoption of a child.

- Invest in programs to increase educational and occupational equity: In order to address educational and occupational segregation, policies and programs should be adopted that support access to higher education, increase recruitment in higher-paying occupations, and raise the visibility of Black women in leadership and roles in which they have historically been underrepresented. New York City’s Tech Talent Pipeline and the State’s “If You Can See It, You Can Be It” initiative offer different models of public-private partnerships designed to achieve these aims. Additional resources should be invested in such efforts, with an emphasis on programming informed by and targeted directly to young girls of color. The City should also examine strategies to direct more capital specifically to Black women entrepreneurs and to sustain Black women-owned businesses.

- Strengthen enforcement of anti-discrimination laws and practices: Despite the fact that New York City has among the strongest anti-discrimination laws in the country, discrimination clearly persists. That is why oversight and enforcement of current statutes must be vigilant. This includes not only holding those in violation accountable but also raising awareness among impacted communities about existing rights and means of seeking recourse. It is imperative that the City foster an environment where Black women are comfortable and have the means to safely come forward to share their experiences of discrimination. It also means using the City’s legislative and regulatory powers to create greater transparency around compensation and promote the use of standardized pay rates.

Endnotes

[i] New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, Power and the Gender Wage Gap: How Pay Disparities Differ by Race and Occupation in New York City (April 10, 2018), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/newsroom/on-equal-pay-day-comptroller-stringer-releases-first-of-its-kind-analysis-spotlighting-massive-gender-and-racial-wage-gaps-by-occupation-in-new-york-city/.

[ii] U.S. Census Bureau data cited in this brief are derived from the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis of American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. Unless specified otherwise, data cited as current are 2016 5-Year Estimates, the latest available.

[iii] Institute for Women’s Policy Research, The Gender Wage Gap by Occupation 2017 and by Race and Ethnicity (April 2018), https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/C467_2018-Occupational-Wage-Gap.pdf.

[iv] New York State Office of Children and Family Services, “Local Commissioners Memorandum” (September 6, 2016), http://ocfs.ny.gov/main/policies/external/OCFS_2016/LCMs/16-OCFS-LCM-18.pdf.

[v] The NYU Furman Center, CoreData.nyc; The estimate of the cost of a down payment assumes a 20 percent down payment on a home at the median sales price in New York City (see pg. 14 of The NYU Furman Center and Citi, NYU Furman Center/Citi Report on Homeownership & Opportunity in New York City (August 2016), http://furmancenter.org/files/NYUFurmanCenterCiti_HomeownershipOpportunityNYC_AUG2016.pdf.

[vi] Estimate based on the cost of a “low-cost” food plan (second most expensive plan), as defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, inflated by 28 percent to account for higher grocery prices in New York City. Cost does not include food eaten away from home. See the Comptroller’s Office’s Affordability Index: https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/affordability-index/.

[vii] MTA, “Fares & MetroCard,” http://web.mta.info/metrocard/mcgtreng.htm; Car price estimate based on Kelley Blue Book average July 2018 transaction prices, https://mediaroom.kbb.com/2018-08-01-Demand-Quickly-Backing-Away-from-Cars-Pushing-Average-New-Car-Transaction-Prices-Up-for-July-2018-According-to-Kelley-Blue-Book.

[viii] The City University of New York, “Tuition & Fees,” (accessed July 3, 2018), http://www2.cuny.edu/financial-aid/tuition-and-college-costs/tuition-fees/.

[ix] Kim Parker, “Women more than men adjust their careers for family life,” Pew Research Center (October 1, 2015), http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/10/01/women-more-than-men-adjust-their-careers-for-family-life/.

[x] Stephanie Luce, Sasha Hammad, and Darrah Sipe, Short-Shifted (2015), http://retailactionproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/ShortShifted_report_FINAL.pdf.

[xi] “Home Health Aides and Personal Care Aides,” Occupational Outlook Handbook, Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/home-health-aides-and-personal-care-aides.htm. As shown in the Comptroller’s Quarterly Economic Updates, overall employment gains are being made primarily in low-wage and medium-wage industries, not high-wage industries. See, for example, Q12018 NYC Quarterly Economic Update (May 2018), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/new-york-city-quarterly-economic-update/.

[xii] New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, Power and the Gender Wage Gap: How Pay Disparities Differ by Race and Occupation in New York City (April 10, 2018), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/newsroom/on-equal-pay-day-comptroller-stringer-releases-first-of-its-kind-analysis-spotlighting-massive-gender-and-racial-wage-gaps-by-occupation-in-new-york-city/.

[xiii] See discussion, for example, on how access to education creates a “wealth feedback loop” in Amy Traub, Laura Sullivan, Tatjana Meschede, and Tom Shapiro, The Asset Value of Whiteness: Understanding the Racial Wealth Gap (February 2017), https://www.demos.org/sites/default/files/publications/Asset%20Value%20of%20Whiteness_0.pdf.

[xiv] Black Women’s Roundtable, Black Women in the US 2017: Moving Our Agenda Forward in a Post-Obama Era (March 2017), https://www.ncbcp.org/BWR2017Report4thEdition.BlackWomenintheU.S.040617final.pdf.

[xv] U.S. Department of Commerce, “Women in STEM: 2017 Update” (November 2017), http://www.esa.doc.gov/sites/default/files/women-in-stem-2017-update.pdf; “Fastest Growing Occupations,” Occupational Outlook Handbook, Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/ooh/fastest-growing.htm.

[xvi] The labor force is defined here as the proportion of the total 16 and older population that is employed or unemployed. The unemployment rate is the proportion of the civilian labor force that is unemployed. The American Community Survey (ACS) and Current Population Survey (CPS) collect labor force data differently, using different questionnaires and reference periods. As a result, ACS figures and those produced and reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which inputs CPS data, may vary.

[xvii] Lincoln Quillian, Devah Pager, Ole Hexel, and Arnfinn H. Midtbøen, “Meta-analysis of field experiments shows no change in racial discrimination in hiring over time,” PNAS (August 2017), http://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/early/2017/09/11/1706255114.full.pdf.

[xviii] Institute for Women’s Policy Research and National Domestic Workers Alliance, The Status of Black Women in the United States (June 2017), https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/The-Status-of-Black-Women-6.26.17.pdf.

[xix] National Economic & Social Rights Initiative, A New Social Contract: Collective Solutions Built By and For Communities (May 2018), https://www.nesri.org/sites/default/files/ANSC%20Report%20Web%20Final_0.pdf.

[xx] New York City Comptroller Scott M. Stringer, Power and the Gender Wage Gap: How Pay Disparities Differ by Race and Occupation in New York City (April 10, 2018), https://comptroller.nyc.gov/newsroom/on-equal-pay-day-comptroller-stringer-releases-first-of-its-kind-analysis-spotlighting-massive-gender-and-racial-wage-gaps-by-occupation-in-new-york-city/.

[xxi] Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations, Journal of Economic Literature (2017), https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/jel.20160995.

[xxii] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, “Employment: Time spent in paid and unpaid work, by sex,” OECD.Stat, https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=54757.

[xxiii] The New York Women’s Foundation, Economic Security and Well-Being Index for Women in New York City (March 2013), https://www.nywf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/New-York-Womens-Foundation-Report.pdf.

[xxiv] The Comptroller’s Office’s Earned Income Tax Credit proposal is accessible at https://comptroller.nyc.gov/reports/fighting-poverty-and-expanding-opportunity-the-earned-income-tax-credit-in-nyc/.

[xxv] Elise Gould and Celine McNicholas, “Unions help narrow the gender wage gap,” Economic Policy Institute (April 2017), https://www.epi.org/blog/unions-help-narrow-the-gender-wage-gap/.