Introduction

Other Post-Employment Benefits (OPEB) are benefits offered to City employees after their retirement from City service. OPEB are a form of deferred compensation and they generally consist of various types of health insurance coverage. The City has historically chosen to fund OPEB on a pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) basis: the City pays the annual cost of benefits offered to its retired employees from its operating budget. This practice has been variously compared to a hidden cost and a credit card without spending limits.

Alternatively, the City could fund OPEB in a similar fashion as it does pension obligations: by investing annual contributions to obtain returns sufficient to pay future obligations. To be sure, as shown in research by the Pew Charitable Trusts, the long-term funding of OPEB benefits is not common and even States that do choose this option are often far away from full funding.

With the help of data from the Office of the NYC Actuary, this fiscal note shows how much it would cost for the City to shift away from PAYGO toward full funding. Because the amount of accrued unfunded liability is approximately $100 billion, the cost of pursuing long-term funding is substantial. In the scenarios shown in this fiscal note, OPEB contributions would range between $6.6 billion and $8.1 billion in FY 2026.

The OPEB Liability

The OPEB liability is contractual and is set in collective bargaining. As such, it differs fundamentally from pension obligations, which are protected by the New York State Constitution. Nevertheless, changes to the benefits have proven difficult even with the support of labor unions, as recently seen with the proposed shift of Medicare-eligible retirees to a Medicare Advantage plan. Consequently, OPEB are best understood as a long-term liability and are seen as such by rating agencies.

In the analysis, we focus on OPEB excluding the City’s component units that participate in the program (Health + Hospital Corporation, the NYC Housing Authority, the School Construction Authority, and the Water Finance Authority) and the Educational Construction Fund.[1] The Office of the Actuary publishes annual actuarial reports while financial statements are available as part of the City’s Annual Comprehensive Financial Report (ACFR). In the next subsections we provide a short description of the main features of OPEB. Readers are referred to the annual reports for additional details.

Description of Health Benefits

In FY 2024 the OPEB plan had nearly 570,000 members, with approximately 257,300 receiving benefits. The Health Benefits Program generally covers retirees with at least ten years of credited service, their spouses, and their children up to age 26 (or longer if disabled). The City and the component units participating in OPEB generally provide health insurance, Medicare Part B reimbursements, and contribute to Welfare Funds that are administered by labor organizations. Some benefits are provided through the Health Insurance Stabilization Fund (HISF).

Health Insurance. The City and participating component units offer Basic Coverage for hospital and physician services at no cost for retirees participating in the HIP HMO and GHI/EBCBS. Medicare-eligible retirees are offered the HIP VIP Premier (HMO) and GHI Senior Care plans, also at no cost. HIP VIP is a Medicare Advantage plan under Medicare Part C. Senior care, which as of 2023 covered most of the Medicare-eligible retirees, is a Medicare supplemental plan. Retirees can join other plans offered by the City that require contributions.

Medicare Part B. Medicare-eligible retirees can apply for reimbursement of Medicare Part B Premium (both base and Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amounts).

Welfare Funds. The City contributes to Welfare Funds for benefits beyond the Basic Coverage, such as prescription drugs, dental, vision, and others. Welfare Funds also provide a range of non-health related benefits. An analysis of the funds published by this office is available here.

Health Insurance Stabilization Fund (HISF). HISF provides some health-related benefits and also pays annual contributions to the Welfare Funds equal to $165 per active employee and retiree. HISF has suspended certain payments to the Welfare Funds (as well as to the City) in 2022. Its disposable balance was essentially depleted in FY 2024.

The Link Between HISF and the Proposed Medicare Advantage Plan

HISF was created in 1984 “to provide a sufficient reserve; to maintain to the extent possible the current level of health insurance benefits provided under the Blue Cross/GHI-CBP plan; and if sufficient funds are available to fund new benefits.” In essence, HISF was meant to equalize the cost of health insurance under the two plans offered at no cost to employees (HIP and GHI). The City’s administrative code provides that the City must pay the HIP HMO rate. At the time HISF was created, the HIP premium was higher than GHI’s and the City contributed the difference to HISF’s “short-term” fund. As GHI’s premium started exceeding HIP’s, HISF funded the difference. A chronology of the short-term fund and the labor agreements that affected its expenses is available in a companion fiscal note. This fund held $1 million at the end of FY 2024.[2]

In July 2021, the City and the Municipal Labor Committee agreed to enroll retirees covered by Senior Care in a Medicare Advantage plan unless they opted out by October 31, 2021. City contributions to the new Medicare Advantage plan would be zero and continued participation in Senior Care would be fully covered by retiree contributions. The City estimated at the time that the transition would reduce OPEB costs by $600 million annually. This amount was to become an annual revenue source for HISF.

In December 2024, the NY State Court of Appeals ruled that the City must cover the cost of the Senior Care plan because it is lower than a cap set by the HIP HMO plan. Given that the majority of Medicare-eligible retirees chose Senior Care over a Medicare Advantage plan already offered by HIP VIP Premier, and that both options would be available at no cost to them, the ruling effectively means that the planned savings and participation in the new plan cannot be achieved. The Court of Appeals has yet to rule on a separate lawsuit where the City claims it does not have to offer multiple plans to Medicare-eligible retirees. Should the City prevail, it could be allowed to offer only a Medicare Advantage plan to all Medicare-eligible retirees.

The OPEB Liability

The Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) statement 45 required the alignment reporting of OPEB to that of pensions starting in 2006. This means that the City started reporting the value of benefits already accrued as the value of assets that back the liability. In order to create a vehicle to hold assets and pay for health benefits, Local Law 19 of 2006 created the Retiree Health Benefits Trust (RHBT). RHBT was established “for the exclusive benefit of retired city employees and their dependents” and its sole purpose is to “fund the health and welfare benefits of retired city workers and their dependents.”

The trust ended its first year with a balance of $1.0 billion, against an accrued liability of $55.0 billion. Stated differently, the City’s FY 2006 unfunded OPEB liability was $54.0 billion. In FY 2024, it was $98.2 billion. The unfunded OPEB liability is reflected in the City’s statement of net position and is the largest contributor to its deficit, as explained in the 2024 State of the City’s Economy and Finances (see Table 15).[3]

The operation of RHBT. The City pays for OPEB through the RHBT and through direct payments out of its general fund. The latter generally benefit the City’s component units who reimburse the City for the cost. Mechanically, each year the City makes contributions to RHBT to cover the PAYGO amount of the benefits. Occasionally, the City contributes more than the PAYGO amount, therefore increasing the year-end RHBT balance. Excess contributions can have two purposes:

- Pre-pay the next year’s PAYGO amount. These contributions are temporary and are used to lower the upcoming fiscal year expenditures.

- Fund the OPEB liability. In theory, these contributions should remain in the RHBT balance and be invested in a diversified portfolio.

However, RHBT was and remains principally a vehicle for PAYGO payments, for two reasons. First, there are no mandated deposits into RHBT and the City can draw down its balance by appropriating less than the full PAYGO amount. In fact, RHBT has been used in the past as a de facto rainy-day fund to cover budgetary needs.[4]

Second, RHBT invests uniquely in cash and cash-equivalent assets. A portfolio truly aimed at funding the OPEB liability would be diversified across asset classes, with periodic reviews of asset allocations, and it would earn a higher risk-adjusted return. The only reason to justify leaving money on the table is that RHBT is not, in fact, funding the OPEB liability.

Normal Cost and PAYGO Amount. The normal cost of OPEB is the actuarial value of the benefits accrued in a given year for active employees, while the PAYGO amount is the actual amount paid for retirees. To calculate the normal cost, the City’s actuary generally makes and revises assumptions regarding future use to benefits, the cost of health insurance, and a discount rate. After the enactment of GASB statements 74 and 75 in FY 2017, the City has used a variable discount rate based on the Municipal Bond 20-year Index Rate. This injected a certain amount of volatility into the estimates, particularly at times when the interest rate environment changes rapidly.

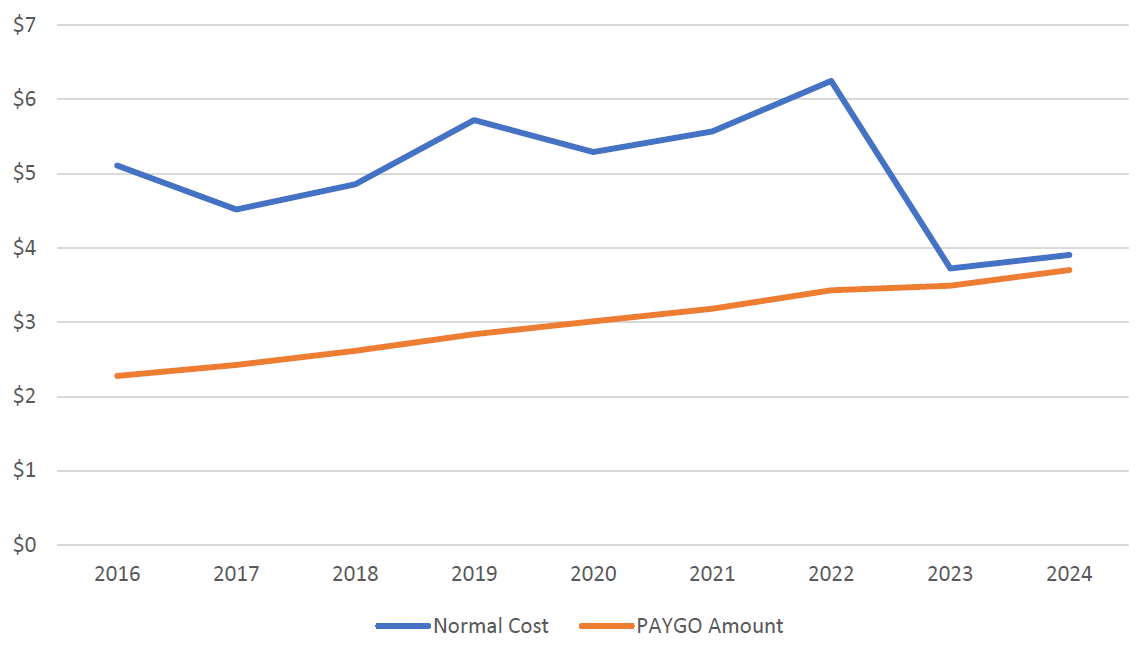

Chart 1 shows the normal cost and the PAYGO payment over time. The first observation is that while the City only pays the PAYGO amount, each year an even larger benefits amount is earned by current employees. Funding of retiree benefits on a PAYGO basis also means that their cost will be shouldered by future taxpayers.

The second observation is the large decline in normal cost in FY 2023. This is due to the higher discount rate driven by tighter monetary policy. Specifically, the discount rate increased from 2.2% to 4.1% in FY 2022. Because the normal cost is calculated on a one-year lag, the effect is reflected in FY 2023.

Chart 1. Normal Cost and PAYGO Payments for the Health Benefits Program ($b)

Source: Office of the NYC Actuary, GASB 74/75 OPEB Report (see table of page 58). Data excludes the City’s component units.

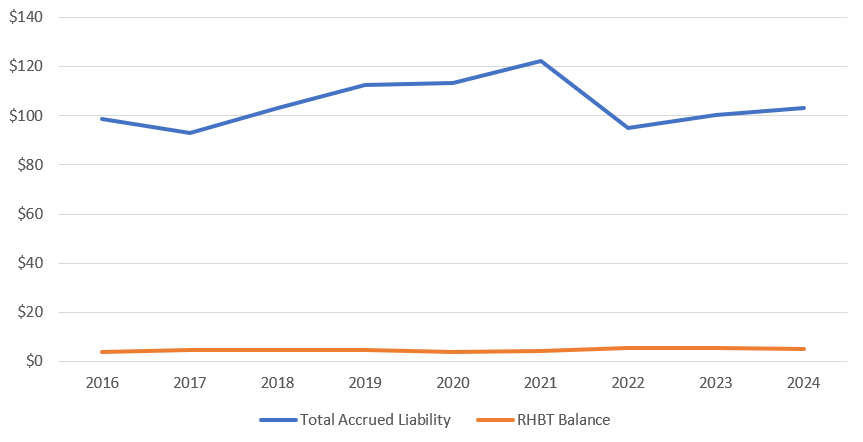

Accrued and Unfunded OPEB Liability. To show the amount of underfunding, Chart 2 shows the total accrued liability against the RHBT balance. The difference between the two lines is the net OPEB liability, or Unfunded Accrued Liability (UAL).

Should the City decide to fund the OPEB liability, it would have to pay for the normal cost going forward and amortize the unfunded accrued liability. Reducing the cost and/or extent of the coverage would reduce the funding need. For instance, the Office of the NYC Actuary estimated that the shift from Senior Care to Medicare Advantage would have reduced the accrued OPEB liability by $18 billion in FY 2023.

Chart 2. Accrued OPEB Liability and RHBT Balance ($b)

Source: Office of the NYC Actuary, GASB 74/75 OPEB Report (see table of page 58). Data excludes the City’s component units. The RHBT balance includes pre-payments of PAYGO contributions.

The Cost of Fully Funding the OPEB Liability

To fully fund the OPEB liability, the City would need to make annual contributions for: 1) the normal cost of future benefits; and 2) the amortization of OPEB’s UAL. In addition, the City needs State legislation to restrict the use of funds and mandate the amount to be deposited into RHBT. Similar to what happens for the pension systems, RHBT funds would need to be managed and invested based on recurring strategic allocations approved by a trustee or board of trustees. The legislation would also fix a long-term investment return target and formulas for phasing in changes in actuarial assumptions, deviations from the investment return target, retirement behavior, and so on. Legislation could also require recurring independent audits of the OPEB plan and actuarial assumptions (as is the case for the City’s pension funds). More detailed “core elements” for funding OPEB plans are provided by the Government Finance Officers Association.

The Amortization of the Pension UAL

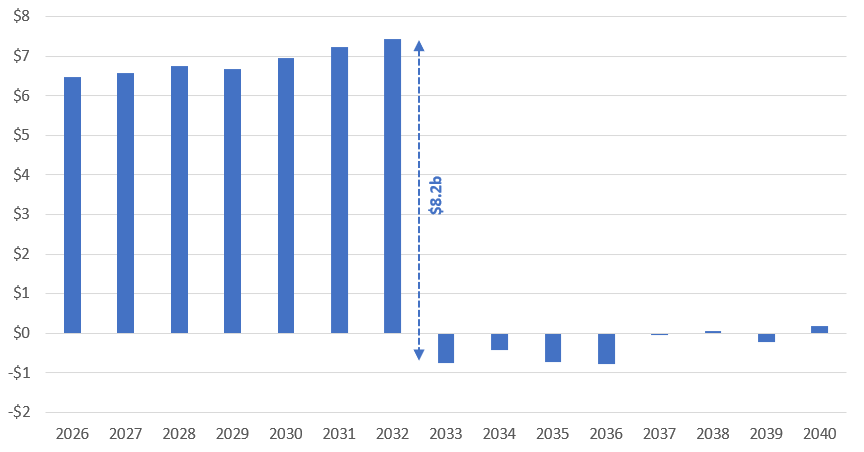

Before delving into cost estimates for OPEB, it is worth looking at the City’s pension UAL. Under State law enacted in 2013, the City and other obligors are required to make payments to amortize the initial pension UAL. As a result of the legislation, the City’s net pension liability has been steadily declining in since FY 2013, both in absolute terms and as a percentage of personal income (see this Office’s December 2024 State of the Economy and Finance, Chart 12). The amortization of the initial UAL ends in FY 2032, when the pension systems would be fully funded assuming all assumptions are met as projected.

The amortization payments cover a base amount set in relationship to the initial pension UAL, which was set assuming investments would achieve a 7% rate of return. Since then, the systems have on average been able to achieve this rate of return. Every year, the contribution amount changes based on, among other things, changes to actuarial assumptions, retirement behavior and life expectancy, as well as actual investment returns. These changes are usually phased in over several years.

A crucial feature of the amortization formula is that the base payment increases by 3 percent each year. This was meant to keep UAL payments at an approximately constant share of total payroll cost (assuming the latter would also grow at 3 percent). The 3% growth of base payments is the main determinant of the increasing projected contributions through FY 2032 shown in Chart 3. The end of the amortization of the initial pension UAL determines a “contribution cliff” in FY 2033. The cliff is made larger by credits accumulated by the systems over time. The credits mean that the systems would be more than fully funded in FY 2032 and contributions would turn negative in FY 2033 and onward. Based on preliminary FY 2026 estimates, UAL contributions for the five systems would drop by $8.2 billion between FY 2032 and FY 2033.

Chart 3. Projected Pension UAL Contributions ($b)

Source: Office of the NYC Actuary, preliminary FY 2026 estimates.

The Cost of Funding the OPEB Liability

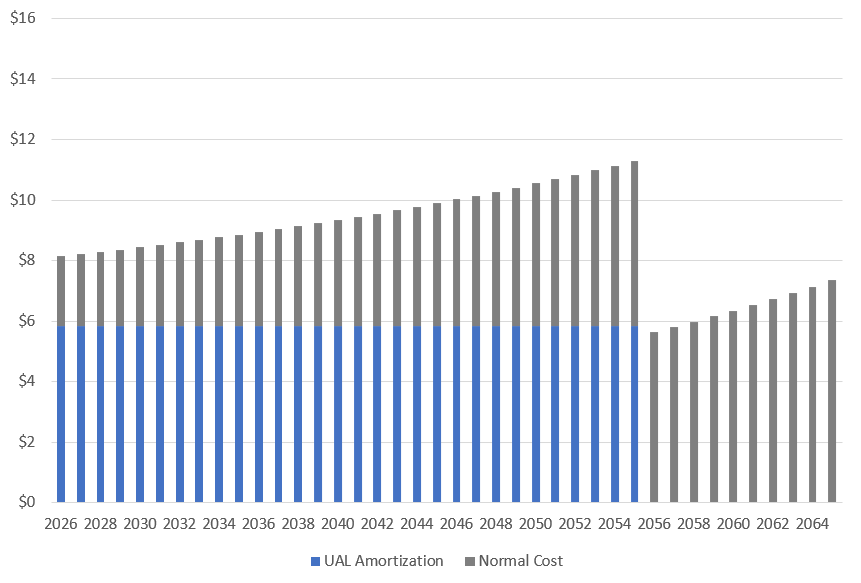

The cost estimates are based on two main assumptions: that the target rate of return on investments is set at 7% (the same as the pension funds) and that the normal cost grows at 3% per year. This is the assumption driving the amortization of the pension UAL and is an approximation of the long-term growth rate of payroll costs. The rate of return assumption immediately reduces the FY 2024 normal cost from $3.9 billion to $2.0 billion. By the same token, the total FY 2024 accrued liability drops from $103.3 billion to $74.9 billion. The estimates assume that the FY 2024 balance of RHBT is not drawn down (in fact, it would lose its function of de facto rainy-day fund going forward) and that the amortization of UAL is over 30 years. There are two scenarios for the amortization of UAL: 1) payments are a fixed percentage of payroll (and therefore grow at 3% annually); or 2) payments are a fixed dollar amount. The projection horizon is 30 years (FY 2026 to FY 2055).

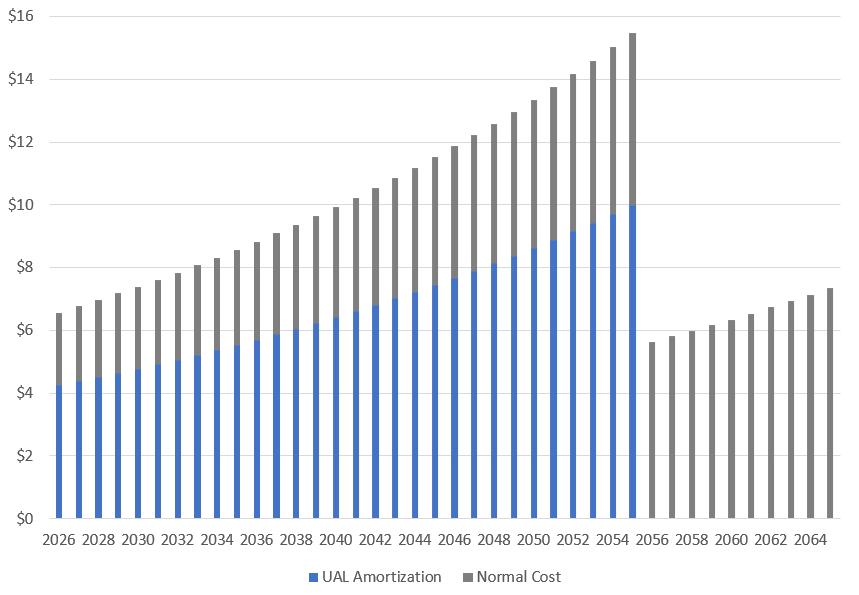

Chart 4 shows the amount of normal cost, UAL amortization payment, and their total under the assumption that amortization is a constant percentage. Under this scenario, the first UAL payment would be $4.2 billion and the total would start at $6.6 billion and grow at 3% annually. Total contributions peak at $15.5 billion in FY 2055, the last year of UAL amortization.

Chart 4. Projected OPEB Contributions – Fixed % UAL ($b)

Source: Office of the NYC Actuary, FY 2025 estimates.

Chart 5 shows contributions under the assumption that the UAL amortization is a fixed dollar amount. The main difference between the fixed percentage and the fixed dollar amount is that contributions start higher in the latter and grow at a slower pace until their peak of $11.3 billion in FY 2055.

Chart 5. Projected OPEB Contributions – Fixed $ UAL ($b)

Source: Office of the NYC Actuary, FY 2025 estimates.

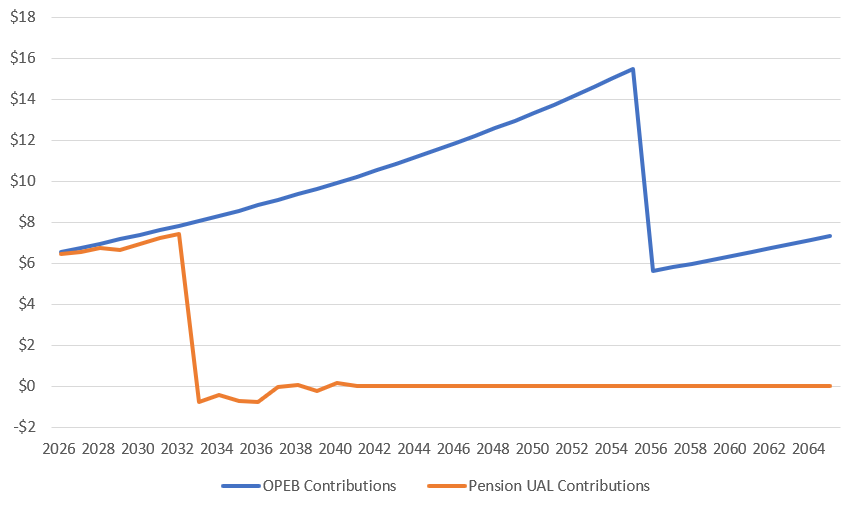

Chart 6 compares the pension UAL payments with projected OPEB contributions in the fixed percentage scenario. The chart shows that OPEB contributions would be comparable to the pension UAL payments before the latter drop off. It appears unlikely that the City could find sufficient fiscal space to be able to afford both the pension UAL and OPEB contributions. However, it would be theoretically possible to start funding OPEB once the pension UAL payments drop off.

Chart 6. Projected OPEB (Fixed % UAL) vs. Pension UAL Contributions ($b)

Source: Office of the NYC Actuary. Pension UAL contributions are preliminary FY 2026 estimates.

Conclusions

Through collective bargaining, the City has for decades offered health coverage to its retirees. However, the City has not accumulated sufficient assets to fund this long-term obligation and is paying for benefits on a PAYGO basis.

This fiscal note answers a simple question: what would it cost to put the City on a path to fully fund OPEB obligations? The accrued liability was approximately $100 billion in FY 2024 and the annual cost of future benefits was $3.9 billion. These amounts could be lowered by investing funds to obtain a higher long-run rate of return. Even so, the annual cost would be substantial, starting at least at $6.6 billion annually and growing from there, roughly equal to the annual amortization (ending in 2032) of the City’s pension UAL.

Acknowledgements

This fiscal note was prepared by Francesco Brindisi, Executive Deputy Comptroller for Budget and Finance, with the assistance of the Office of the NYC Actuary. Archer Hutchinson, Creative Director, led the report design and layout. The author is thankful for the comments received on earlier drafts and is responsible for any errors.

Endnotes

[1] The NYC Educational Construction Fund (ECF) participate in the NYS Health Insurance Program (NYSHIP) and postretirement health benefits are not paid by the City.

[2] In 1995, the City transferred to HISF the reserve for claims incurred but not yet paid by “GHI/CBP/Blue Cross Basic Plan, all optional rider coverage, the Blue Cross Supplemental Hospital Reserves, and the Blue Cross Hospital Advantage Payments.” It is this Office’s understanding that this reserve represents the balance of HISF’s “core” fund, which is not disposable. At the end of FY 2024, this fund held $844 million. Due to its structural deficit, HISF suspended its $165 contributions to the Welfare Funds (which accumulated through a number of labor agreements) and an annual $112 million transfer to the City (pursuant to a 2009 agreement). In order to fund the difference between the GHI and HIP premium, the Office of the Comptroller estimated that the City should pay an additional $500 million in FY 2025.

[3] Given its sheer size, the unfunded OPEB liability all but guarantees the dubious distinction of placing the City at the bottom of the “Truth in Accounting” rankings of financial rectitude.

[4] Given these mechanics, the annual drawdowns of the RHBT balance cannot exceed the value of that year PAYGO contribution, net of any prepayment from previous fiscal years.