Executive Summary

The vast majority of workers in New York City are at-will employees, meaning that they can be fired for any reason that does not violate existing anti-discrimination and retaliation laws, and without being provided with a justification for their firing. As a result, many workers in New York City, particularly in low-wage industries that have historically been plagued by worker exploitation, have been terminated for arbitrary and non-performance-related reasons. To ameliorate this problem, New York City passed first-in-the-nation just cause termination legislation that requires there be just cause for termination in the fast food industry. This report analyzes economic data and past enforcement to determine the impact of Local Laws 1 and 2 of 2021 (“Just Cause Law” or “the Law”) on New York City’s fast food industry and its workforce.

Key Findings

This report analyzed employment survey data and found that, since implementation in July 2021, the Just Cause Law has not led to a decrease in fast food employment nor the number of establishments. This report also examined specific cases investigated by the New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP) in its enforcement of fast food just cause and found that the Law reduced arbitrary firings and strengthened anti-retaliation protections for workers in the industry.

New York City’s Fast Food Industry:

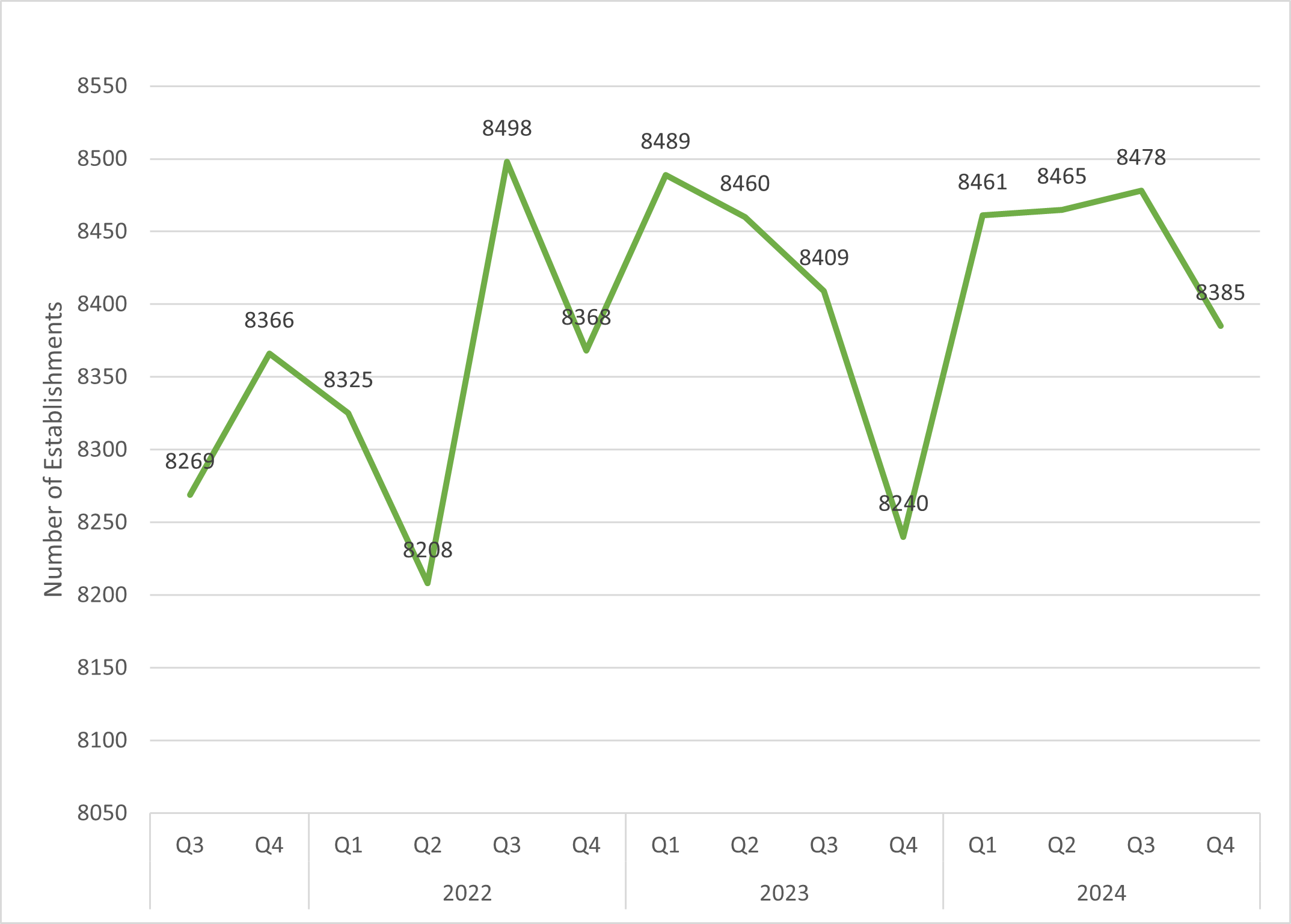

- The number of fast food establishments in New York City has slightly increased since the implementation of the Just Cause Law. Between the third quarter of 2021, when the Law went into effect, and the last quarter of 2024, there was a 1% increase from 8,269 to 8,385 fast food establishments. In this same period, there was an average quarterly increase in establishments of .2%, which was higher than the year and a half before the Law was implemented and on par with the rate of growth for the three-year period before the COVID-19 pandemic.

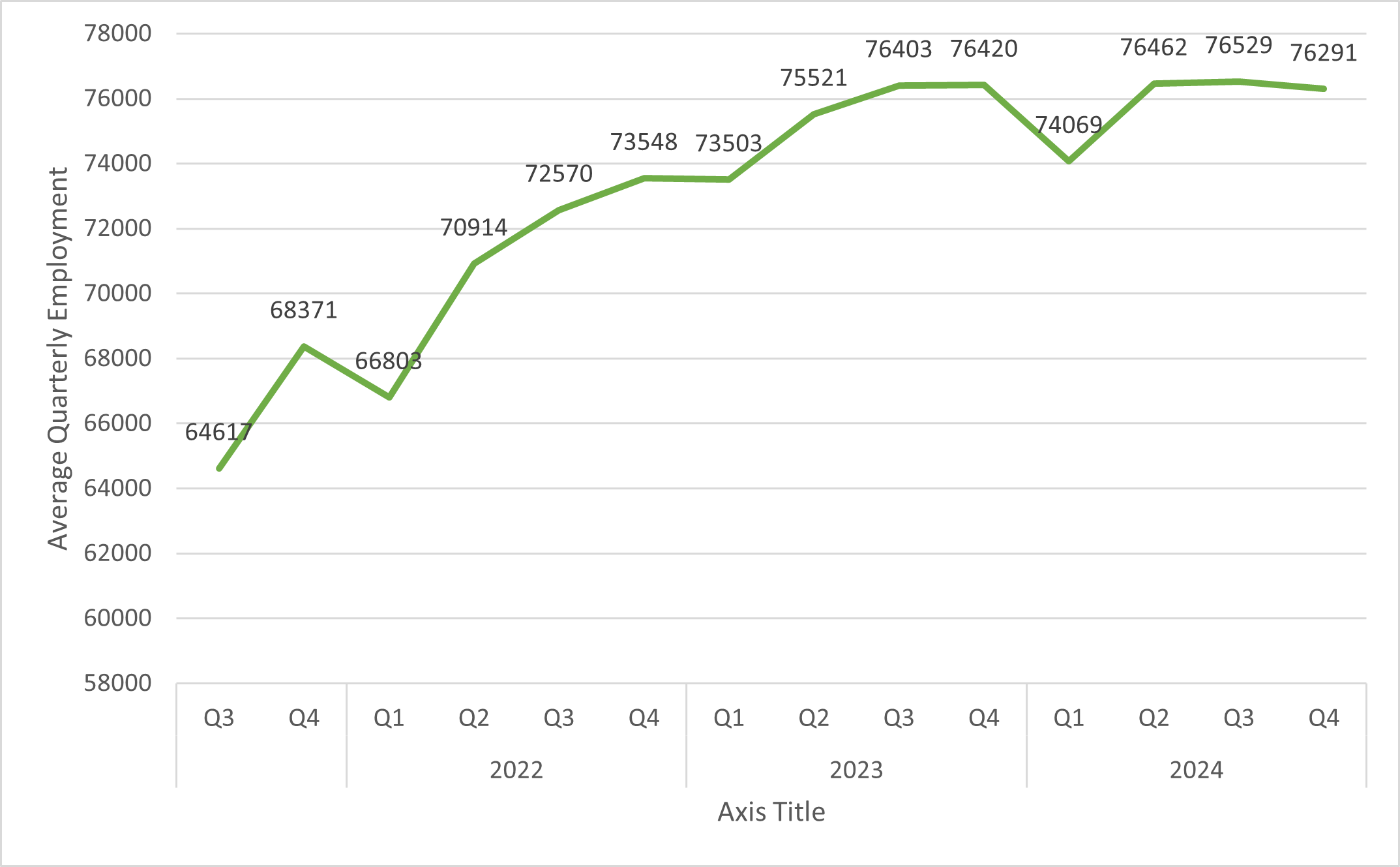

- The number of workers employed in the fast food industry in New York City has increased since the implementation of the Just Cause Law. Between the third quarter of 2021 and the fourth quarter of 2024, there was an 18% increase, from 64,617 to 76,291. In this same period, there was an average quarterly increase in employment of 1.7%, higher than the growth rate for both the year and a half before the Law was implemented and the three-year period before the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The data on fast food establishments and employment does not indicate that the Just Cause Law interfered with the industry’s recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, as post-pandemic, 2022 to 2024, numbers were ultimately closer to the pre-pandemic levels than the pandemic levels:

- Number of establishments: There was an increase of 2% in the number of fast food establishments between the pandemic and post-pandemic period, from 8,271 to 8,398, respectively. While lower than the 8,469 fast food establishments pre-pandemic, the gap between pre-and post-pandemic periods was only 1%.

- Number of Employees: There was around a 25% increase in the number of fast food employees between the pandemic and post-pandemic periods, from 59,534 to 74,086. While this is lower than the number of fast food employees in the pre-pandemic period, the gap between the pre- and post-pandemic periods was only 4%, with 76,802 employees pre-pandemic.

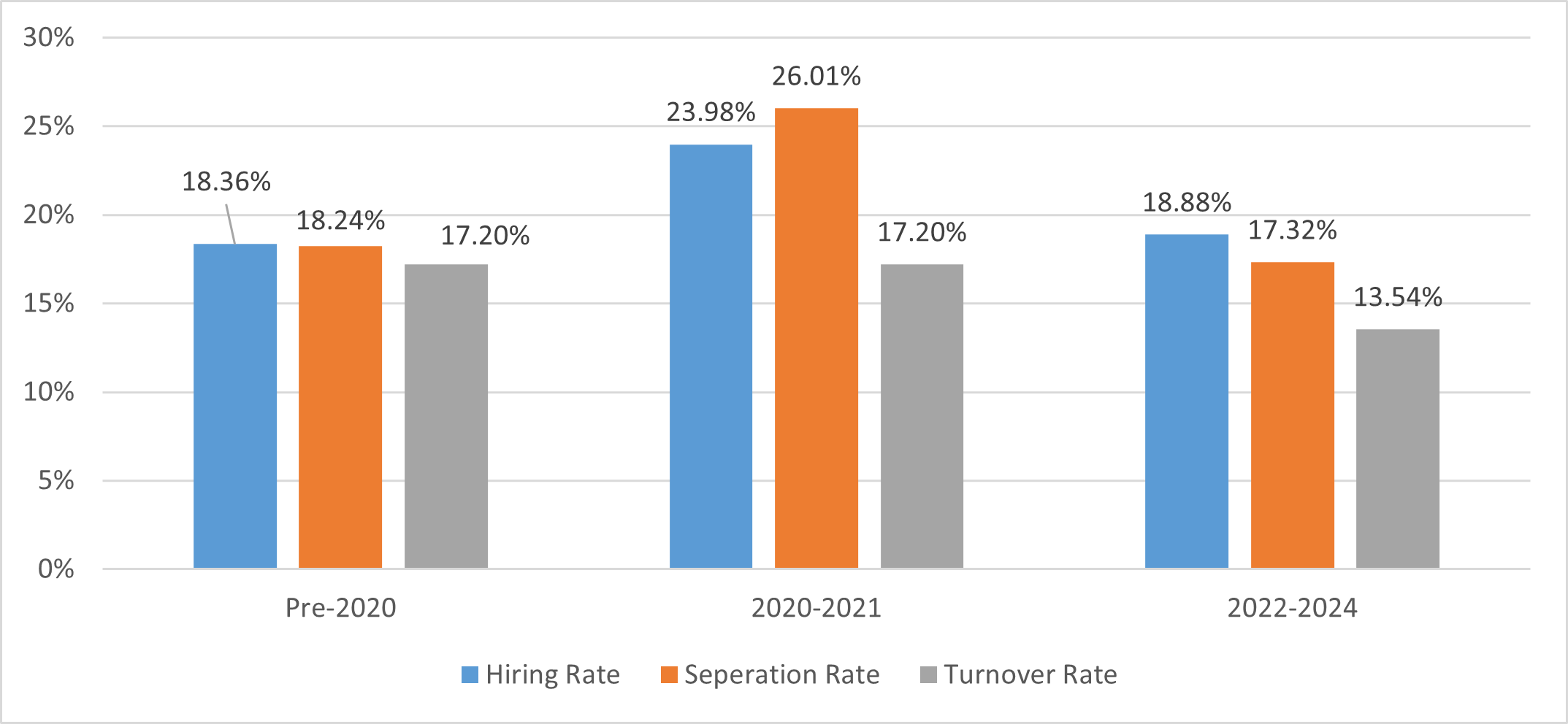

- In addition to aggregate-level data, key metrics capturing labor market flows (hiring, separation, job creation, job destruction, and excess reallocation rates) indicate that the volatility in the fast food industry caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has largely dissipated.

Impact on Workers in the Industry:

- The Just Cause Law has had a positive impact on the working conditions of workers in New York City’s fast food industry. Qualitative evidence from enforcement cases conducted by DCWP demonstrates just cause has protected fast food workers who faced unjust firings while speaking out about issues in the workplace, managing personal emergencies, navigating situations outside of their control, and accessing other worker protections.

Summary of Recommendations:

- Pass legislation that makes just cause the universal standard for all employees. The City Council must pass the Secure Jobs Act (Introduction 0909-2024), a bill introduced by Council Member Tiffany Cabán, that would extend just cause protections to all employees in New York City.

- Enact legislation that establishes deactivation protections, which are tantamount to firing, for app-based delivery workers and for-hire vehicle workers (Intro 1332-2025, sponsored by Council Member Justin Brannan, and Intro 276-2024 sponsored by Council Member Shekar Krishnan, respectively), and fully fund its enforcement.

- Support worker organizing by using a variety of tools – such as procurement, licensing, investments, and information sharing – to empower and inform New Yorkers’ efforts to join a union and collectively bargain.

Background

Just Cause vs At-Will Employment

“Just cause” is a term of employment law referring to a type of employment relationship where workers can “only be fired for specified reasons, such as misconduct, incompetence, or unfavorable economic conditions.”[1] The bulk of just cause employment arrangements exist in the context of employment relationships governed by collective bargaining agreements, negotiated between unions and employers. Outside of the collective bargaining context, a small percentage of employees have some degree of just cause protections granted to them through their individual contracts or official company policies, such as in employee manuals and oral promises made by supervisors detailing a specific duration of employment or standard procedures for dismissal.[2]

With only around 21% of all workers in New York City unionized and just 13.7% of all private sector workers in New York City unionized, most workers in the city are not afforded just cause protections.[3] Instead, most workers in New York City are employed “at-will.” This means, according to the Office of the New York State Attorney General, that employers are “not required to have good cause to fire [an at-will employee]… [an employer] can do this for reasons many people might consider unfair such as, your boss wants to replace you with a member of their own family, you fought with a coworker (even if the other worker is not fired as well), your boss does not like you and you had to come back late from vacation because your flight was cancelled.”[4]

While at-will employers are not required to give written justification for a termination, certain laws bar employers from firing at-will workers for specific prohibited reasons. These include terminations based on discrimination against a protected class (such as race, gender, and religion), retaliation for whistleblowing about a violation (such as wage theft or workplace safety hazards), or in response to workers exercising a protected workplace right (such as attempting to organize a union or filing a workers’ compensation claim).[5]

Issues With At-Will Employment

Despite anti-discrimination and anti-retaliation laws that set boundaries on permissible firings, proving that the firing was for an illegal reason can be difficult, in large part due to the lack of a requirement that employers provide workers with a stated reason for their termination. This is particularly the case for workers who lack access to legal counsel or an understanding of how to file complaints with agencies.[6]

Previous research into at-will workers in New York City, through surveys conducted by Data for Progress and The National Employment Law Project, has shown the high prevalence of unjust firings and their negative impacts. A 2023 survey conducted by these organizations found a significant percentage of firings that took place without reasons provided or prior warnings issued, and that many firings were done in retaliation for speaking up about workplace issues. [7] Specifically, the survey found that:

- 60% of fired workers said their employers gave them either no reason or an unfair or inaccurate reason for their termination.

- Nearly 9 out of 10 workers who were fired were given no warning.

- Only 3% of fired workers were offered more training before a termination.

- About 1 in 7 workers were fired or disciplined for speaking up about issues at the workplace.[8]

A 2025 survey from the same organizations found a high prevalence of firings of New York City workers in response to those workers attempting to meet childcare needs and a troubling frequency of unreported workplace discrimination. Specifically, the survey found that:

- 34% of survey participants were fired or disciplined for making time for childcare responsibilities.

- Latino workers self-reported much higher rates of being fired or disciplined for making time for childcare responsibilities (55%) compared with their White (37%) and Black (26%) counterparts.

- Among survey participants who said they experienced unlawful workplace discrimination, such as ethnicity-based discrimination and gender discrimination, 61% said they avoided speaking out due to fear of retaliation.[9]

Fast Food Just Cause Law

Given these aforementioned issues faced by many at-will employees (fear of speaking out about issues at the workplace, an inability to dispute arbitrary firings, stress in managing child and family care responsibilities, limited recourse for disputing illegal retaliatory firings, and more), the City took a historic step by enacting the first-ever law mandating just cause within the fast food industry. In 2021, the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP) began enforcing the Just Cause Law, which prevents fast food employers from firing workers or reducing their hours without providing a legitimate performance-related reason. Specifically, the Law requires that employers provide a written explanation for a firing, reduction of hours of 15% or more, or layoff. In cases where a worker has a job performance issue, the Law stipulates that employers must allow these workers an opportunity to improve prior to termination. This aspect of the Just Cause Law, known as “progressive discipline,” requires that for non-serious job performance issues, an employer must give an employee who is past their probation period multiple disciplinary warnings before firing them. Furthermore, the Law requires that when layoffs occur for a bona fide economic reason, the employer must lay off workers in reverse order of seniority, with the longest-serving workers laid off last, and demonstrate economic hardship via documentation. In addition, employers must also give laid-off or current workers priority to work newly available shifts.[10]

New York City’s Fast Food Industry

Economic data on the fast food industry post-implementation of the Just Cause Law reveal that the Law has not caused a decrease in fast food employment nor the number of establishments, despite fears that the Law might slow its post-COVID-19 pandemic rebound. [11]

Aggregate Labor Market Data

Changes in the Number of Fast Food Establishments and Employment Since July 2021

Data from the New York State Department of Labor’s Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) dataset show that the number of fast food[i] establishments have slightly increased since the implementation of just cause. As seen in Figure 1, in the third quarter of 2021, when the Law went into effect, the number of fast food establishments was 8,269, and by the fourth quarter of 2024, it was 8,385, a 1% increase. Comparing the third quarter of 2023 with the third quarter of 2024, in which there were 8,478 establishments, shows that there was a 3% increase.

In this period, there were no drastic changes between quarters, with the highest shift being a 4% increase in the number of establishments from the second to the third quarter of 2022. The largest decline in the number of establishments was a 2% decline from the third quarter to the fourth quarter of 2023, which was subsequently followed by a 3% increase in the first quarter of 2024.

The average change per quarter in the number of establishments in this period was .2%. This represents an increase from the previous period, the first quarter of 2020 up through the second quarter of 2021, where growth on average was -.8%. While the period immediately before the Law included the COVID-19 pandemic, the growth rate for 2022 to 2024 was about the same as the rate for the three years before the pandemic (2017 to 2019), which was .3%.

The number of workers employed within the fast food industry has increased since the implementation of just cause. As seen in Figure 2 in New York City in the third quarter of 2021, the average number of workers employed at fast food establishments[ii] was 64,617, and by the fourth quarter of 2024, it was 76,291, an increase of 18%. Comparing the third quarter of 2023 with the third quarter of 2024, in which there was an average of 76,529 employees, shows that there was an increase of approximately 18.5%.

The largest quarter change was between the first and second quarters of 2022, where there was an 8% increase. The largest quarterly decline in employment was between the fourth quarter of 2023 and the first quarter of 2024, a 3% decline, which was immediately followed by a 3% increase. On average, employment increased by 2% each quarter in this period.

The average change per quarter in the number of employees in this period was 1.7%. This represents an increase from the previous period, the first quarter of 2020 up through the second quarter of 2021, where growth on average was -.5%. In addition to being higher than the previous period, which included the COVID-19 economic disruption, the rate for 2022 to 2024 was greater than the rate for the three years before the pandemic, which was .9%.

Figure 1: Number of Fast Food Establishments in New York City, Second Half of 2021 to 2024

Figure 2: Average Quarterly Employment at Fast Food Establishments in New York City, Second Half of 2021 to 2024

Pandemic Recovery

As the Just Cause Law was being implemented, the COVID-19 pandemic was winding down. Data on the number of workers and establishments during the post-pandemic period does not indicate that the Just Cause Law interfered with the fast food industry’s recovery. While the post-pandemic employment and establishment numbers are lower than the pre-pandemic numbers, they are closer to what the industry looked like before the pandemic than during the pandemic.

As seen in Table 1, the number of establishments increased from 8,271 to 8,398 between the pandemic and the post-pandemic period, respectively. This was an increase of 127 establishments, or 2%, which was greater than the difference between the pre- and post-pandemic periods, 71 establishments, or 1%. Similarly, for employment, there was around a 25% increase between the pandemic and post-pandemic periods, which was significantly greater than the difference between the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic periods, 4%. This expansion of employment suggests continued sectoral recovery and demand growth.[12]

Table 1: Establishments, Employment, and Wages, Fast Food Industry, in New York City

| Period (average) | Establishments | Employment |

| Pre-Pandemic (2017-2019) | 8,469 | 76,802 |

| Pandemic (2020–2021) | 8,271 | 59,534 |

| Post-Pandemic (2022–2024) | 8,398 | 74,086 |

Labor Market Flows

In addition to aggregate labor market figures, data on labor market flows in the larger restaurant industry[iii] in New York City does not show that the Just Cause Law has interfered with the industry’s post-pandemic recovery.

Quarterly Workforce Indicators (QWI) data, tracking how restaurant jobs in New York City turn over and adjust, does not show that the Just Cause Law has interfered with the industry’s post-pandemic recovery. Key metrics from this data indicate that the volatility incurred by the COVID-19 pandemic has dissipated.

Two key metrics are hiring rates, the share of jobs in a quarter that employers fill with new hires, and separation rates, the share of jobs that end in a quarter, including quits and discharges. As seen in Figure 3, before 2020 (2018 and 2019), the hiring and separation rates were 18.36% and 18.24%, respectively, with a turnover rate of 17.2%, which already reflects a high-churn industry. During the 2020 and 2021 period, hiring rose to 23.98% and separations to 26.01%, while turnover remained at 17.2%, showing intense gross flows as firms shed and rehired workers through the pandemic shock. In the 2022 to 2024 period, hiring and separations fell back to 18.88% and 17.32%, and turnover dropped to 13.54%. The sector continued to hire and separate workers at high rates, but overall churn is lower than before 2020.

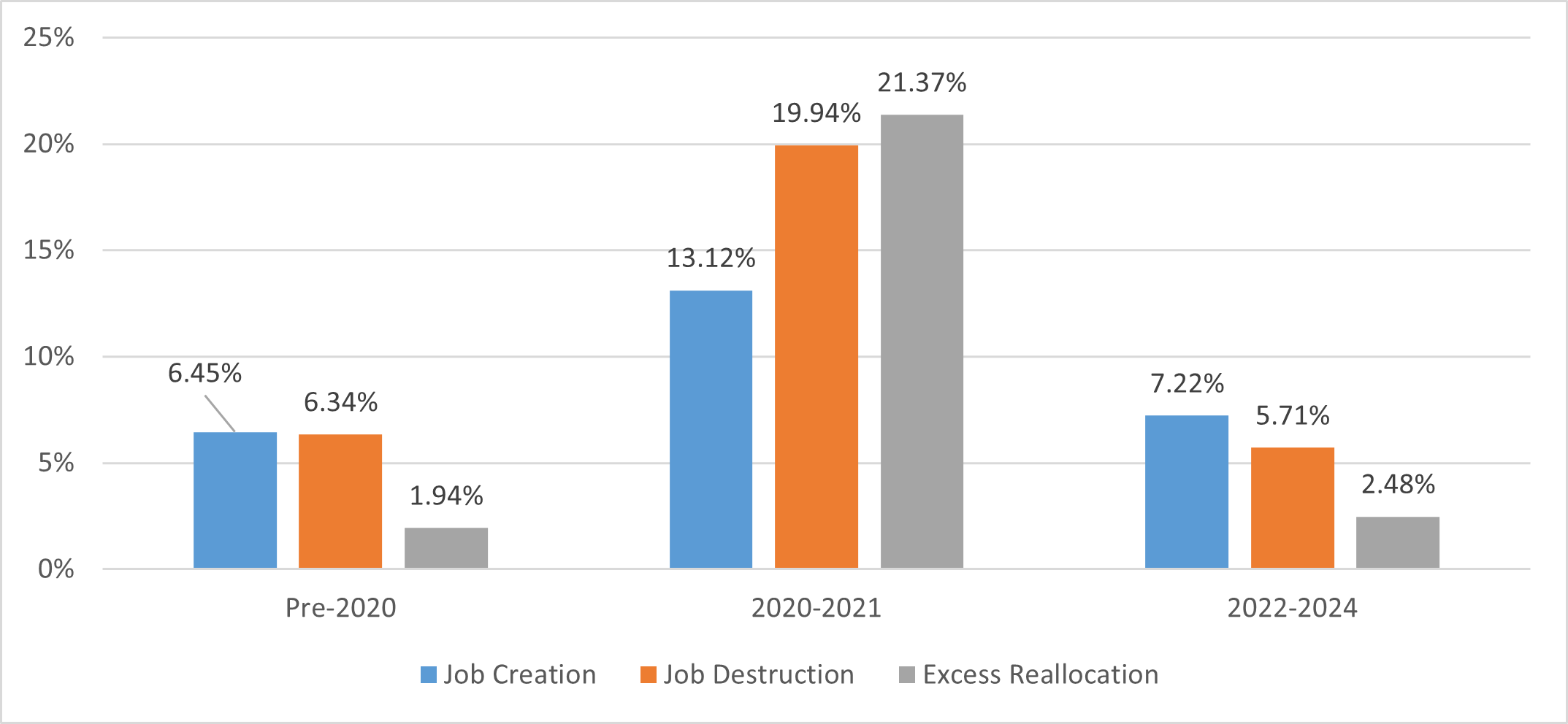

Furthermore, as seen in Figure 4, the job creation rate, the share of employment added at expanding establishments, rose from 6.45% in the pre-2020 period to 13.12% in the 2020 and 2021 period, then settled at 7.22% in the 2022 to 2024 period. The job destruction rate, the share of employment lost at contracting or closing establishments, increased from 6.34% to 19.94% during 2020–2021 and then fell to 5.71% in 2022–2024. The excess reallocation rate, which measures job flows beyond what is needed to account for net growth, jumped from 1.94% pre-2020 to 21.37% in 2020–2021, then declined to 2.48%. These numbers show a brief period of extreme reshuffling during the height of the pandemic, followed by a return to job creation and destruction rates that are close to, and slightly above, pre-2020 levels.[13]

Figure 3: Average Hiring, Separation, and Turnover by Period at New York City Restaurants

Figure 4: Average Job Creation, Destruction, and Excess Reallocation by Period at New York City Restaurants

Fast Food Just Cause’s Impact on Workers in the Industry

From 2021 to 2024, in cases where violations of the Fast Food Just Cause Law were found, DCWP won back over $185,900 in restitution and penalties for 48 workers in 55 closed cases.[14] In addition, in 2025, there have also been major settlements for just cause violations, including at Chipotle, a Pizza Hut franchise (owned by Chaac Pizza Northeast, LLC,[iv] ) and Starbucks.[15] [16] At Starbucks in 2025, there were two Just Cause settlements: one involving an unlawful termination, which was settled for more than $3,500; and a groundbreaking settlement, announced on December 1, 2025, for $38 million for violations of the Fair Workweek Law, covering over 15,000 workers at 300 locations. Among other aspects of the Fair Work Week Law, the latter settlement found that Starbucks had violated the provision of the Just Cause Law that bars employers from reducing hours by more than 15% without just cause or a bona fide economic reason.[17] [18]

Zooming into the stories of fast food workers who filed complaints or participated in DCWP investigations shows the Just Cause Law’s positive impact on workers.

First, the Law has protected workers speaking out about issues in the workplace. In one case, a Starbucks worker in Queens who had been involved in a unionization drive was fired. The worker suspected that he had been fired without just cause, while his employer claimed that he was fired for falsely reporting workplace violence and for missing part of a multipart COVID screening protocol. An investigation from DCWP determined that there was no evidence for the employer’s accusation of false reporting and that, with respect to the second claim, employees had breached the protocol regularly with no prior repercussions, indicating that the worker had been singled out. As part of a settlement between DCWP and Starbucks, the worker was ultimately reinstated and provided with restitution.[19]

In addition, the Law has protected workers managing emergencies in their personal lives. At a Subway franchise in Brooklyn, a set of workers had suddenly needed to take a day off due to unexpected circumstances. Despite the fact that they had found coworkers to cover their shifts in advance, they were fired from their jobs. In investigating the case, DCWP found that they had been fired without just cause or bona fide economic reason, and that their employer had failed to give them a written explanation of their termination, according to the settlement. The Department also found that the Subway franchisee did not have the required system of progressive discipline in place.[20]

The Law has also protected workers from discipline when infractions took place due to reasons outside of their control. In one case, as revealed in a 2025 petition filed by DCWP, a worker at a Starbucks in Brooklyn was fired for falsely logging their work start time, when they arrived at 6:45 am, but were unable to open the store due to company rules barring individual employees from opening a retail location without at least one other co-worker. The worker only entered the store after another co-worker arrived at 7:06 am. In its investigation, DCWP found that the worker had been fired in violation of the Just Cause Law.[21]

Lastly, the Just Cause Law has protected workers attempting to access rights under other NYC workplace laws without retaliation. In 2022, Cava settled with DCWP in a case where a worker was fired in retaliation for accessing time off under the Earned Safe and Sick Time Act (“ESSTA”), which was a violation of both the ESSTA and the Just Cause Law.[22]

Policy Recommendations

Given the positive impact of the Fast Food Just Cause Law on the lives of workers without harming the industry’s economic growth, just cause protections should be expanded across New York City’s labor market.

- Pass legislation that makes just cause the universal standard across all employment in New York City. The City Council should pass the Secure Jobs Act (Intro 0909-2024), a bill introduced by Council Member Tiffany Cabán, that would extend just cause protections to all employees[v] in New York City.[23] The bill would take all aspects of the Fast Food Just Cause Law—the requirement of a just cause or bona fide economic reason for a firing or hours reduction of 15%; advanced and written notice provided; progressive discipline; and reverse seniority order for firings—and provide them to all employees in New York City.

- Enact legislation that establishes deactivation protections for app-based delivery workers and for-hire vehicle workers. With around 65,000 app-based delivery workers and 84,700 drivers working for rideshare companies, app-mediated workers who are classified as independent contractors also work in at-will arrangements.[24] [25] As a result, platform companies can deactivate workers from the app or indefinitely block access to the work platform for a prolonged period of time, sometimes even permanently. To ensure deactivations are not done arbitrarily, and only for performance-related reasons, legal protections that establish just cause-like rules for deactivations are needed. These protections are spelled out in two recently passed City Council bills: Introduction 276-2024 (sponsored by Council Member Shekar Krishnan) and Introduction 1332-2025 (sponsored by Council Member Justin Brannan), which would provide these protections for rideshare drivers and app-delivery workers, respectively. [26] [27] These deactivation protections should be signed into law, and DCWP should be fully funded to ensure effective enforcement.

- Support worker organizing across New York City. In addition to City Council legislation, the City should play a role in helping to expand collective bargaining agreements, particularly within the private sector, where under 14% of workers are unionized. Union membership and collective bargaining are not only the best tools to protect workers from arbitrary terminations, but also have been proven to help improve wages, occupational safety, and access to benefits. [28] The City can support worker organizing by using a variety of tools – such as procurement, licensing, investments, and information sharing – to empower and inform New Yorkers’ efforts to join a union and collectively bargain.

Conclusion

New York City took an important step by establishing the Fast Food Just Cause Law. The Just Cause Law has improved the job quality of fast food workers while not impeding the industry as it continues to rebound from the pandemic. Given this success, these protections should be afforded to more workers in New York City. mean

Methodology

Aggregate data on the total number of establishments and employees came from the New York State Department of Labor’s Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages dataset. The data analyzed included data falling within the 6-digit NAICS code, 722513: Limited-Service Restaurants, to capture fast food establishments. The data was analyzed at the county level. As a result, all figures from this data cited in this report are the totals or averages of all five counties that make up New York City: Bronx, Kings, New York, Queens, and Richmond.

Labor flows data came from the U.S Census’ Quarterly Workforce Indicators dataset. The data analyzed included data falling within the 4-digit NAICS 7225, Limited-Service Eating Places, to capture fast food establishments. The data was analyzed at the county level. As a result, all figures from this data cited in this report are rates of all five counties that make up New York City: Bronx, Kings, New York, Queens, and Richmond.

Both datasets have coverage limitations. As noted by Pickens and Sojourner (2025), the QCEW industry code 722513 (Limited-Service Restaurants) includes all workers potentially affected by New York City’s Just Cause Law, but also many who are not covered. [29] Only employees in chain establishments with 30 or more locations nationwide fall under the Law, and supervisory workers are excluded, though included in the data. Nationally, about 19 percent of industry employment is supervisory, suggesting that about one-fifth of the QCEW sample is unaffected by the regulation.

The issue is larger in the QWI data, where the most detailed category is the four-digit code 7225 (Food Services and Drinking Places). Employment in 722513 represents only about 21% of the total 7225 employment across New York City counties, meaning that most workers in the QWI sample are not covered by the just-cause provisions.

Acknowledgements

This report was authored by Matan Diner, Research and Policy Analyst for Workers’ Rights and Aida Farmand, Senior Tax Policy Analyst, with support from Rebecca Lynch, Deputy Director of Workers’ Rights and Annie Levers, Deputy Comptroller for Policy. Archer Hutchinson, Creative Director, led the graphic design and report layout.

[i] Establishments falling under the 6-digit NAICS code, 722513: Limited-Service Restaurants.

[ii] Average number of employees across all 3 months of the quarter

[iii] For this section, data is only available at the 4-digit NAICS code, “Restaurants and Other Eating Places,” a broader category that includes fast food restaurants among other types of restaurants.

[iv] The settlement was for the franchise’s failure to offer and award shifts to existing employees before hiring new employees.

[v] The bill does not apply to workers under a collective bargaining agreement. It also only applies to workers who are classified as employees and not to independent contractors.

[1] Hoyt, E. (2018). Constraining Labor’s “Double Freedom”: Revisiting the Impact of Wrongful Discharge Laws on Labor Markets, 1979-2014. University of Massachusetts Amherst https://scholarworks.umass.edu/entities/publication/d3764446-36c7-4a48-b423-1403c1b53ed8

[2] Ibid

[3] Milkman, R., & van der Naald, J. (2024). The State Of The Unions 2025: A Profile Of Organized Labor In New York City, New York State, And The United States. City University of New York School of Labor and Urban Studies. https://slu.cuny.edu/public-engagement/research-publications/state-of-the-unions/

[4] Office of the New York State Attorney General. Termination: Workers’ Rights. https://ag.ny.gov/resources/individuals/workers-rights/job-termination

[5] Ibid

[6] The National Employment Law Project. Adopt ‘Just Cause’ Job Protections Against Unfair Firings. https://www.nelp.org/explore-the-issues/worker-power/just-cause/

[7] Tung, I., Sonn, P., Dandekar, A., Pinilla, A., & Solis, A. (2023). Fired Without Warning or Reason: Why New Yorkers Need Just Cause Job Protections. Data For Progress. https://www.filesforprogress.org/memos/nyc_just_cause_secure_jobs.pdf

[8] Ibid

[9] Fairclough II, T. (2025) NYC Workers Face Discipline and Firings Related to Family Responsibilities, and Many Are Hesitant to Speak Out About Discrimination and Harassment in the Workplace. Data For Progress. https://www.dataforprogress.org/blog/2025/5/1/nyc-workers-face-discipline-and-firings-related-to-family-responsibilities-and-many-are-hesitant-to-speak-out-about-discrimination-and-harassment-in-the-workplace

[10] The New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection. (2021). Fast Food Worker Just Cause Job Protections Effective July 4. https://www.nyc.gov/site/dca/news/016-21/fast-food-worker-just-cause-job-protections-effective-july-4#:~:text=The%20just%20cause%20protections%20go,DCWP%20administered%20panel%20of%20arbitrators.

[11] Dobre, S & Carey, P. (2021). New York City Fast-Food Employers Beware: Just-Cause Needed for Firing. Bond, Schoeneck & King PLLC. https://www.bsk.com/news-events-videos/new-york-city-fast-food-employers-beware-just-cause-needed-for-firing#:~:text=Consequently%2C%20service%20industry%20workers%20returning,practices%20of%20just%2Dcause%20discharge

[12] The New York State Department of Labor. Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages. https://dol.ny.gov/quarterly-census-employment-and-wages

[13] United States Census Bureau. Quarterly Workforce Indicators. https://www.census.gov/data/developers/data-sets/qwi.html

[14]The New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection. (2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024) Worker Protection Metrics at the New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP). https://www.nyc.gov/site/dca/workers/annual-highlights.page

[15] The New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection. (2025). In Honor of Labor Day, NYC DCWP Announces $3 Million Secured for Workers From Four Companies. https://www.nyc.gov/site/dca/news/026-25/in-honor-labor-day-nyc-department-consumer-worker-protection-3-million

[16] The New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection. (2025). DCWP Announces Nearly $4 Million in Worker Relief From Four Major Businesses in Celebration of May Day. https://www.nyc.gov/site/dca/news/013-25/dcwp-nearly-4-million-worker-relief-four-major-businesses-celebration-may

[17] (2025) Consent Order, The New York City Department Of Consumer and Worker Protection V. Starbucks Corporation. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/dca/downloads/pdf/media/Starbucks-Consent-Order.pdf

[18] The New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection. (2025). Mayor Adams, DCWP Announce $38 Million Settlement With Starbucks. https://www.nyc.gov/site/dca/news/032-25/mayor-adams-dcwp-38-million-settlement-starbucks-largest-worker-protection

[19] Brown, J. (2023). A Starbucks Worker Fired for Organizing Got His Job Back Thanks to NYC “Just Cause” Laws. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2023/02/new-york-city-just-cause-firing-law-at-will-employment-starbucks-union-organizing

[20] Brendlen, K. (2021). City settles first case under new ‘Just Cause’ law, penalizes Mill Basin restaurant. Brooklyn Paper. https://www.brooklynpaper.com/city-settles-just-cause-mill-basin/

[21] (2025). Wrongful Discharge Petition, The New York City Department of Consumer and Worker Protection V. Starbucks Corporation. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/dca/downloads/pdf/media/Petition-DCWP-v-Starbucks-Corporation-2024-03348-ENF.pdf

[22] Office of the New York City Comptroller Brad Lander. (2025). Employer Wall of Shame. https://comptroller.nyc.gov/services/for-the-public/employer-violations-dashboard/employer-wall-of-shame/#Cava

[23] Cabán, T. (2024). Wrongful discharge from employment. The New York City Council. https://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=6702337&GUID=A3AAF187-7341-4ADF-B05B-CDDD1FFE2000&Options=Advanced&Search=

[24] Workers Justice Project. Los Deliveristas Unidos. https://www.workersjustice.org/en/ldu#:~:text=Los%20Deliveristas%20Unidos%20(LDU)%20organizes,are%20classified%20as%20independent%20contractors

[25] Schneider, T. (2025). Taxi and Ridehailing Usage in New York City. Toddwschneider.com. https://toddwschneider.com/dashboards/nyc-taxi-ridehailing-uber-lyft-data/

[26] Krishnan, S. (2024). Wrongful deactivation of high-volume for-hire vehicle drivers. The New York City Council. https://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?ID=6557685&GUID=B1AD10BE-3B1B-4782-8AE8-65B9C1E20563&Options=ID%7cText%7c&Search=276

[27] Brannan, J. (2025). Wrongful deactivation of app-based delivery workers. The New York City Council. https://legistar.council.nyc.gov/LegislationDetail.aspx?From=Alert&ID=7480055&GUID=265D0ED3-FB2F-48B9-AF70-79973B11E094&Options=Advanced

[28] McNicholas, C., Poydock, M., Shierholz, H., & Wething, H. (2025). Unions aren’t just good for workers—they also benefit communities and democracy. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/unions-arent-just-good-for-workers-they-also-benefit-communities-and-democracy/

[29] Pickens, J., & Sojourner, A. (2025). Effects of Fair Workweek Laws on Labor Market Outcomes. W.E Upjohn Institute For Employment Research. https://research.upjohn.org/up_workingpapers/420/