Review of the New York City Police Department’s Body-Worn Camera Program

Introduction

Background

The New York City Police Department (NYPD) is the largest, and one of the oldest, municipal police departments in the United States, with approximately 36,000 police officers and 19,000 civilian employees. The NYPD is divided into major bureaus for enforcement, investigations, and administration. It has 78 precincts with patrol officers and detectives covering the entire City.

In 2013, the federal court settlement of Floyd v. City of New York (Floyd) mandated NYPD to implement a series of reforms to address unlawful stop and frisk patterns and practices, including changes to its policies, training, supervision, monitoring, and discipline.[1] One of the changes required by the remedial order was for NYPD to implement a body-worn camera (BWC) program to visually and audibly record certain interactions between officers and the public for law enforcement purposes. The goals of the program were (and continue to be) to create objective records of stop-and-frisk encounters, encourage lawful and respectful police-citizen interactions, alleviate mistrust between NYPD and the public, and help determine the validity of accusations of police misconduct. In 2014, a Federal Monitor (Monitor) was appointed to oversee the reforms. The Monitor remains in place today and is required to periodically file public reports detailing NYPD’s compliance.[2]

NYPD’s BWC program began in April 2017, and by August 2019, most officers were assigned BWCs. According to NYPD’s Patrol Guide, all uniformed officers performing patrol duty are required to wear a BWC and must activate it prior to engaging in any police action.[3]

In November 2018, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) published a report on the use of BWCs by law enforcement agencies in the United States. According to the report, the main reasons that local police and sheriffs’ offices acquired BWCs were to improve officer safety, increase the quality of evidence, reduce civilian complaints, and reduce agency liability.

According to a report from the U.S. Department of Justice, police executives cited many ways in which BWCs have helped their agencies strengthen accountability and transparency.[4] They also stated that BWCs are helping to prevent problems from arising in the first place by increasing officer professionalism, aiding agencies in evaluating and improving officer performance, and allowing agencies to identify and correct larger structural problems within their departments. The officials further stated that BWCs have made their operations more transparent to the public and have helped resolve questions following encounters between officers and members of the public. As a result, they report that their agencies are experiencing fewer complaints and that encounters between officers and the public have improved.

NYPD officials indicated that expectations and goals of the BWC program include utilizing BWCs to help ensure officers’ compliance with policies, regulations, and laws (e.g., NYPD’s use-of-force policy, stop-and-frisk policy, policies related to interacting with the public in a respectful manner, etc.). In addition, BWCs provide contemporaneous records of incidents, which may be used as evidence in legal proceedings and as training tools.

BWCs: Use of Cameras

BWCs are small battery-powered cameras worn on officers’ uniforms that capture interactions with the public. Once an officer activates the record switch, there is a one-minute pre-event buffer.[5] The BWC then records all audio and video until the switch is deactivated. Recordings cannot be paused, only stopped. When deactivated, the BWC returns to the buffering state, and the process is repeated.

At the end of their tours, officers must place BWCs in a docking station located at their commands in a location inaccessible to the general public. Once docked, recorded videos are automatically uploaded to a cloud-storage system, Evidence.com, and the BWC is recharged automatically.

As stated previously, officers must activate their BWCs prior to engaging in any police action, including stops, frisks, searches, and use-of-force incidents.[6] BWC footage is reviewed to determine whether cameras were activated late or deactivated early, and whether stops comply with the Patrol Guide. These reviews occur during ComplianceStat meetings, which are held on a regular basis to identify improper stops, frisks, searches, and use-of-force incidents (among other things), and assess BWC compliance rates and address accountability within commands.

In addition, the Federal Monitor reviews BWC footage to assess the constitutionality of stops, frisks, and searches, as well as to determine whether Stop Reports are being prepared. The Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) reviews BWC footage as part of its investigations of misconduct allegations for force, abuse of authority (which includes stops, frisks, and searches), discourtesy, offensive language, and untruthful statements.

NYPD currently uses Axon 3 and Axon 4 cameras.

Stop, Frisk, and Search Encounters

According to NYPD’s Patrol Guide, Investigative Encounters, for every Level 3 Stop (which is any encounter between a civilian and a uniformed officer in which a reasonable person would not feel free to disregard the officer and walk away), the officer is required to complete a Stop Report. Stop Reports are completed in NYPD’s Finest Online Records Management System (FORMS). The data is then fed into NYPD’s Crime Data Warehouse (CDW) system, which includes information about whether there was a sufficient/reasonable basis for the stop, frisk, and search.

NYPD reviews Stop Reports and associated BWC footage to assess whether the stop, frisk, and search was performed according to departmental procedures established in NYPD’s Patrol Guide, Investigative Encounters. At each precinct, sergeants must select and review five videos from the previous month’s recordings by their assigned officers. Sergeants assess whether there was a sufficient basis for the stop, frisk, and search. The sergeants document their findings monthly in Self-Inspection worksheets and indicate follow-up actions where necessary. These include providing officers with instructions, training, or initiating disciplinary action. Sergeants forward the results to Reviewing Lieutenants. The worksheets are maintained at the precinct and are subject to inspection by NYPD’s Professional Standards Division (PSD).[7]

Each quarter, PSD randomly selects five files per sergeant from designated Bureaus, Boroughs, and Specialty Units to review. These Quarterly Inspections are completed using the same criteria as the monthly self-inspections with the exception that completed reviews are returned by the last day of the requesting month to PSD. The Integrity Control Officer (ICO) is responsible for ensuring the timely completion and submission of Self-inspections.[8] In addition, each command’s ICO is responsible for monthly self-inspections of Stop Reports, known as a Stop Report BWC worksheet (802 Worksheet). 802 Worksheets are submitted to PSD for review.

Use-of-Force Encounters

According to NYPD’s Patrol Guide, Force Guidelines, force may be used when it is reasonable to ensure the safety of a member of the service or a third person, or otherwise protect life, and when it is reasonable to place a person in custody or to prevent escape from custody. In all circumstances, any application or use of force must be reasonable, and all members of the service must employ less lethal alternatives and prioritize de-escalation, whenever possible. If the force used is unreasonable under the circumstances, it is deemed excessive and in violation of NYPD policy.[9] The application of force must be consistent with existing law and with NYPD policies, even when NYPD policy is more restrictive than State or Federal law. Depending on the circumstances, both State and Federal laws provide for criminal sanctions and civil liability against officers when force is deemed excessive, wrongful, or improperly applied.

In all use-of-force incidents, an immediate supervisor responds to the scene to assess the circumstances and level of force and/or type of injury, in order to determine the appropriate reporting and investigative requirements. All reportable uses of force by members of the service are investigated, including those found to be within department guidelines. Incidents involving use-of-force must have a Threat, Resistance, or Injury Incident (TRI) Report.

TRI Reports record data associated with a use-of-force incident, including the type(s) of force utilized, the members of the service who used force and/or were subjected to force, any injuries, whether BWC footage recorded the incident, and other circumstances. The existence of a TRI Report determines whether available BWC footage is reviewed by NYPD; if available, the footage is reviewed by NYPD as part of its process for assessing use-of-force incidents.

BWC Freedom of Information Law Requests

The Freedom of Information Law (FOIL), Article 6 Sections 84-90 of the New York State Public Officers Law, provides the public with the right to access records maintained by government entities. FOIL requests must be in writing, reasonably describe the records sought, and contain sufficient detail to allow a search to be conducted. Anyone can submit a FOIL request for BWC footage.

Public Officers Law Section 89(3) requires that, within five business days of receiving a FOIL request, the agency must either grant the request and make the record available, deny the request, or provide a written acknowledgment of the request and notify the requester of a reasonable estimated response date. FOIL includes several exemptions that permit an agency to deny access to a record. Exemptions are weighed based on the potential for harm that would arise if the record were disclosed.

At NYPD, FOIL requests are handled by the Legal Bureau and are usually made through Open Records. Denied FOIL requests can be submitted to NYPD for administrative appeal. If the appeal is denied, the decision can be challenged in court through an Article 78 proceeding.

Objectives

The objectives of this review were to assess NYPD’s implementation and oversight of its Body-Worn Camera Program (BWC), including its internal use of footage to identify use of force and the legitimacy of stops, and its level of compliance with FOIL requests for BWC footage.

The scope of this review was January 1, 2020 through May 21, 2025.

This review was initiated by the Comptroller’s Office based on a complaint that NYPD denied FOIL requests for BWC footage without valid justification, resulting in Article 78 proceedings to obtain FOILed BWC footage. NYLPI indicated that NYPD often refuses to provide footage without valid justification.

Discussion of Review Results with NYPD

The matters covered in this report were discussed with NYPD officials during and at the conclusion of this review. On September 11, 2025, we submitted a Draft Report to NYPD with a request for written comments. We received a written response from NYPD on September 30, 2025.

In its response, NYPD agreed with nine recommendations, essentially agreed with three recommendations (#6, #11 and #13) (indicating the recommendations reflect its current practices), and stated it would consider implementing one recommendation (#12). NYPD also submitted comments questioning the audit team’s methodology and conclusions. Nonetheless, as noted above, NYPD generally agreed with or is considering all of the report’s recommendations.

The full text of NYPD’s responses is included as an addendum to this report.

Key Takeaways

The audit team found that NYPD’s timeliness in responding to FOIL requests needs improvement. In more than half of all cases, NYPD did not meet its stated goal of granting or denying FOIL requests within 95 business days, and in some cases, took far longer. On average, NYPD took 133 business days to grant or deny FOIL requests during the review period. In almost a quarter (1,137 or 24.8%) of instances that were granted/denied beyond 25 business days, it took more than 200 business days to grant or deny requests. Of these cases, 223 (19.6%) did not result in a decision to grant or deny the request for more than 275 business days—more than one year—after receipt. During the review period, the auditors found the longest period to grant or deny a FOIL request was four years.

In addition, NYPD frequently does not provide BWC video in response to FOIL requests without appeals first being filed. In most instances when NYPD did not initially provide footage, the department eventually did provide it, either following an appeal or after an Article 78 proceeding was filed in court. NYPD’s FOIL appeal process resulted in production of BWC footage 97% of the time, and footage was provided after being challenged in court 92% of the time.

The review found that NYPD’s oversight over the BWC program also needs improvement. BWC activation rates are lower than they should be, and NYPD does not make full use of BWC footage to ensure compliance with internal policies. The auditors also found that BWC footage was missing and incomplete, that required reviews of BWC activation were not conducted, that NYPD lacks independent reviews of BWC activation rates, and that NYPD does not consistently conduct reviews of footage or collect related information and documentation that their policies and procedures indicate are required.

This review contains several recommendations, including that NYPD improve responsiveness on FOIL requests when they are initially received, and that it improve its oversight over the BWC Program. These measures are necessary to improve internal accountability.

NYPD Does Not Produce Records in a Timely Manner

FOIL requires NYPD to respond to FOIL requests within a reasonable period, depending on the complexity and circumstances of the request. Within five business days of the receipt of a request, an agency must either grant the request and provide the requested records, deny it (with an explanation), or provide a written acknowledgment of its receipt with a reasonable approximate date by which it will be granted or denied. If an agency determines to grant a request, in whole or in part, and if circumstances prevent disclosure within 20 business days from the acknowledgement date, it must state, in writing, the reason for the inability to grant it within 20 business days and provide a reasonable date by which it will respond.

For the purposes of this review, auditors used a total of 25 business days from the date of the request to assess NYPD’s responsiveness. The auditors also assessed timeliness against NYPD’s internal goal of 95-days. NYPD did not meet this 25-day timeframe 85% of the time and took longer than 95 days to respond to a FOIL request 54% of the time. On average, it took NYPD 133 business days to grant or deny FOIL requests, ranging from zero days (i.e., granted or denied on the same day it was submitted) to more than four years (1,076 business days) after the initial submission.

NYPD Frequently Grants BWC FOIL Requests Following Appeals and Commenced Article 78 Proceedings

Anyone denied access to a requested NYPD record can appeal the decision with NYPD. Of the 355 BWC footage appeals NYPD received between CYs 2020 through 2024, 344 (97%) were granted. Anyone denied a record by NYPD on appeal can challenge the NYPD’s decision in court. Auditors reviewed New York State Courts Electronic Filing (NYCEF) data online and identified 13 cases related to challenges of NYPD’s denial of BWC footage that were filed between January 1, 2020 through March 24, 2025. Twelve (92%) of these cases resulted in NYPD either being mandated by the court to provide the footage, or NYPD providing the BWC footage to settle the matter; the remaining request for BWC footage was denied by the court.

NYPD Needs to Improve BWC Activation Rates

NYPD performs Intergraph Computer Aided Dispatch (ICAD) audits of dispatched 911 calls to determine whether officers recorded incidents in their entirety, as required. The results are communicated to commands for further investigation/remediation. Auditors aggregated the results of the BWC footage reviews NYPD conducted and determined that footage was not on file for 36% of the incidents in the data set. For footage that was on file, BWCs were activated late and/or deactivated early (i.e., recording was stopped before the incident ended) 18% of the time.

NYPD’s Oversight and Monitoring of the BWC Program is Lacking

Auditors also found that NYPD reviews of BWC activation were lacking. Self-Inspections for BWC activation were not conducted for 53% of the sampled months. Further, NYPD did not ensure that all Self-Inspections were reviewed by each command’s Executive Director, as required; ICOs did not always perform required reviews of Stop Reports and related footage (802 Worksheets); NYPD does not independently review BWC footage to identify use-of-force incidents and does not ensure required TRI Reports are filed when force is used (meaning that BWC footage is also not reviewed); and NYPD does not aggregate the results of its reviews of BWC videos to identify anomalies or trends.

Areas for Improvement

NYPD Should Improve its Responsiveness to FOIL Requests for BWC Footage

Although officials from the Comptroller’s Office, Law Department, the Commission to Combat Police Corruption (CCPC), and the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) reported that NYPD generally fulfills their requests for BWC footage in a timely manner, auditors found that NYPD does not grant or deny BWC FOIL requests from the public within a reasonable timeframe, and does not consistently produce footage as required unless administrative appeals and/or court challenges are filed.[10] On average, it took NYPD 133 business days to either grant or deny FOIL requests, ranging from zero days (i.e., granted/denied on the same day it was submitted) to more than four years (1,076 business days) after the initial submission. In addition, of the 355 appeals for BWC footage NYPD received between CYs 2020 through 2024, 344 (97%) were granted.

It Takes the NYPD an Average of 133 Business Days to Grant/Deny BWC FOIL Requests

FOIL affirms a person’s right to know how the government operates. It provides rights of access to records reflective of governmental decisions and policies. FOIL requests must reasonably describe the records sought and contain sufficient detail to allow a search to be conducted. Most requests are made online through Open Records.[11] Anyone can submit a FOIL request for BWC footage.

According to FOIL, within five business days of receipt of a request, an agency must either grant the request and provide the requested record, deny it (with an explanation), or provide a written acknowledgment of its receipt with a reasonable approximate date by which it will be granted or denied. If an agency determines to grant a request in whole or in part, and if circumstances prevent disclosure within 20 business days from the acknowledgement date, it must state, in writing, the reason why it is unable to grant it within 20 business days and a reasonable date by which it will respond. For the purposes of this review, auditors used a total of 25 business days from the date of request to assess NYPD’s responsiveness.

All FOIL requests for BWC footage are handled by the BWC Unit within NYPD’s Legal Bureau. The Unit tracks requests in its Intranet Tracker database, which contains information about the incident, the requester’s contact information, and notes on the progress of the request, as well as separate spreadsheets for tracking requests that were released and denied. If a request is denied, the agency is required to explain why.

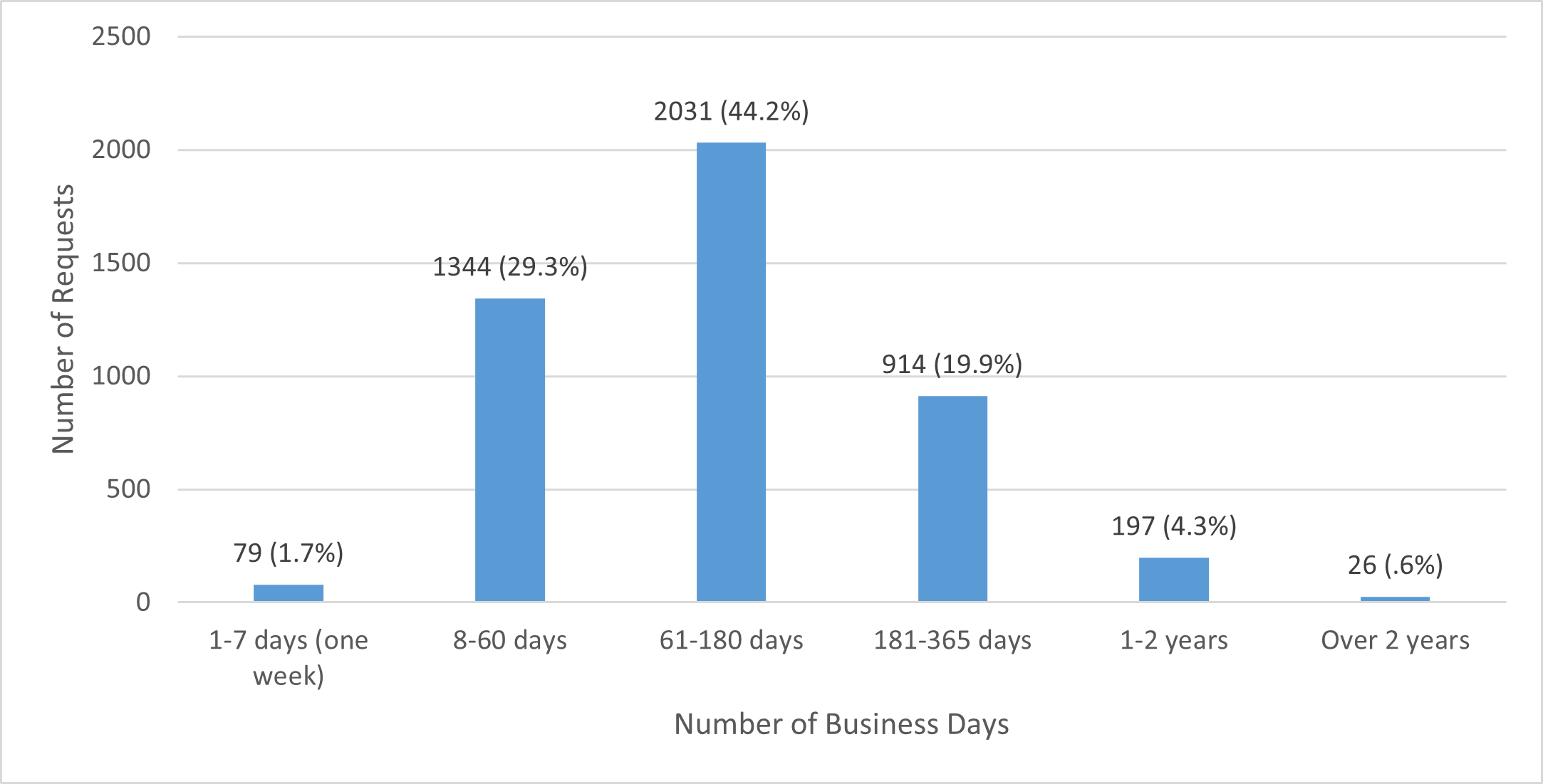

Auditors reviewed 5,427 granted/denied FOIL requests for BWC footage submitted during CYs 2020 through 2024.[12] On average, it took NYPD 133 business days after the FOIL request to make a determination to grant or deny such requests, ranging from zero days (i.e., closed on the same day it was submitted) to more than four years (1,076 business days). Of the 5,427 requests, only 836 (15%) were granted or denied within 25 business days; it took longer than 25 days for the NYPD to grant or deny 4,591 (85%) BWC footage FOIL requests, as shown below in Chart 1.

Chart 1: Number of Business Days Requests Were Granted/Denied Beyond 25-Business-Days

Nearly a quarter (24.8%) of BWC footage requests were granted or denied more than 180 business days after the 25-business day timeframe.[13] NYPD officials stated that due to the high volume of FOIL requests received and its limited personnel, it is not possible to complete FOIL requests within 25 business days.[14] NYPD further stated that its internal goal is to respond to FOIL requests within 95 business days.

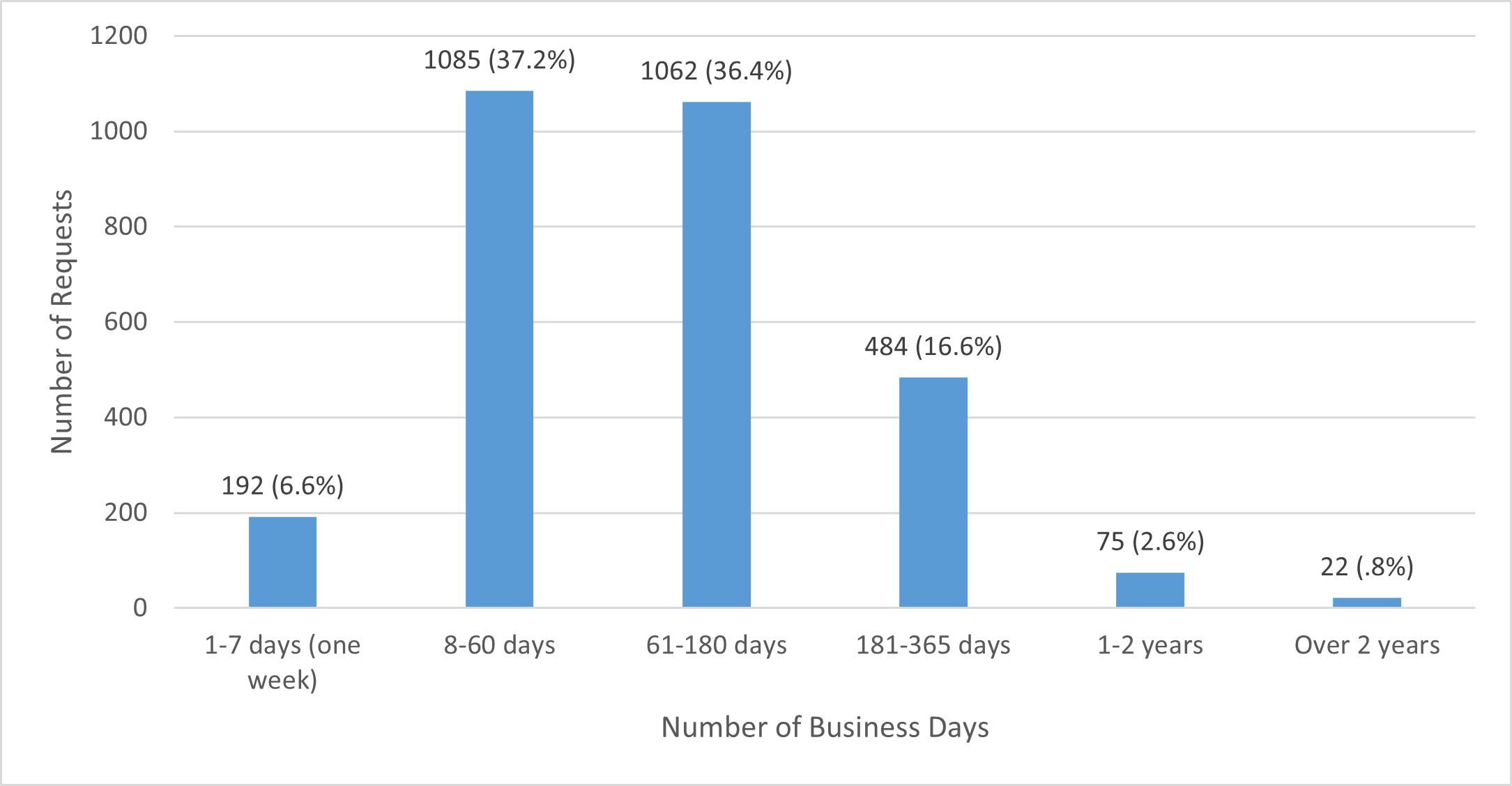

However, NYPD responded to BWC footage FOIL requests within 95 days less than half of the time. Only 2,507 (46%) of the requests were answered within 95 business days. 2,920 (54%) were granted/denied more than 95 business days after receipt, and of these, 581 (19.9%) were decided more than 180 business days after NYPD’s internal target of 95 days, which translates to more than 275 business days after the initial request is received. A breakdown of these requests (where it took NYPD longer than 275 days to respond) is shown in Chart 2.

Chart 2: Number of Requests Granted/Denied Beyond NYPD’s Extended 95-Business-Day Timeline

According to NYPD, judges have held that extended periods of up to 90 business days are reasonable for labor-intensive FOIL requests. NYPD pointed to a 2025 New York County Supreme Court decision, New York Civ. Liberties Union v. New York City Police Dept., which stated that periods of 90 business days have been found reasonable for labor-intensive FOIL requests by New York courts. However, as noted above, NYPD complies with this 90-business-day timeframe only 46% of the time.

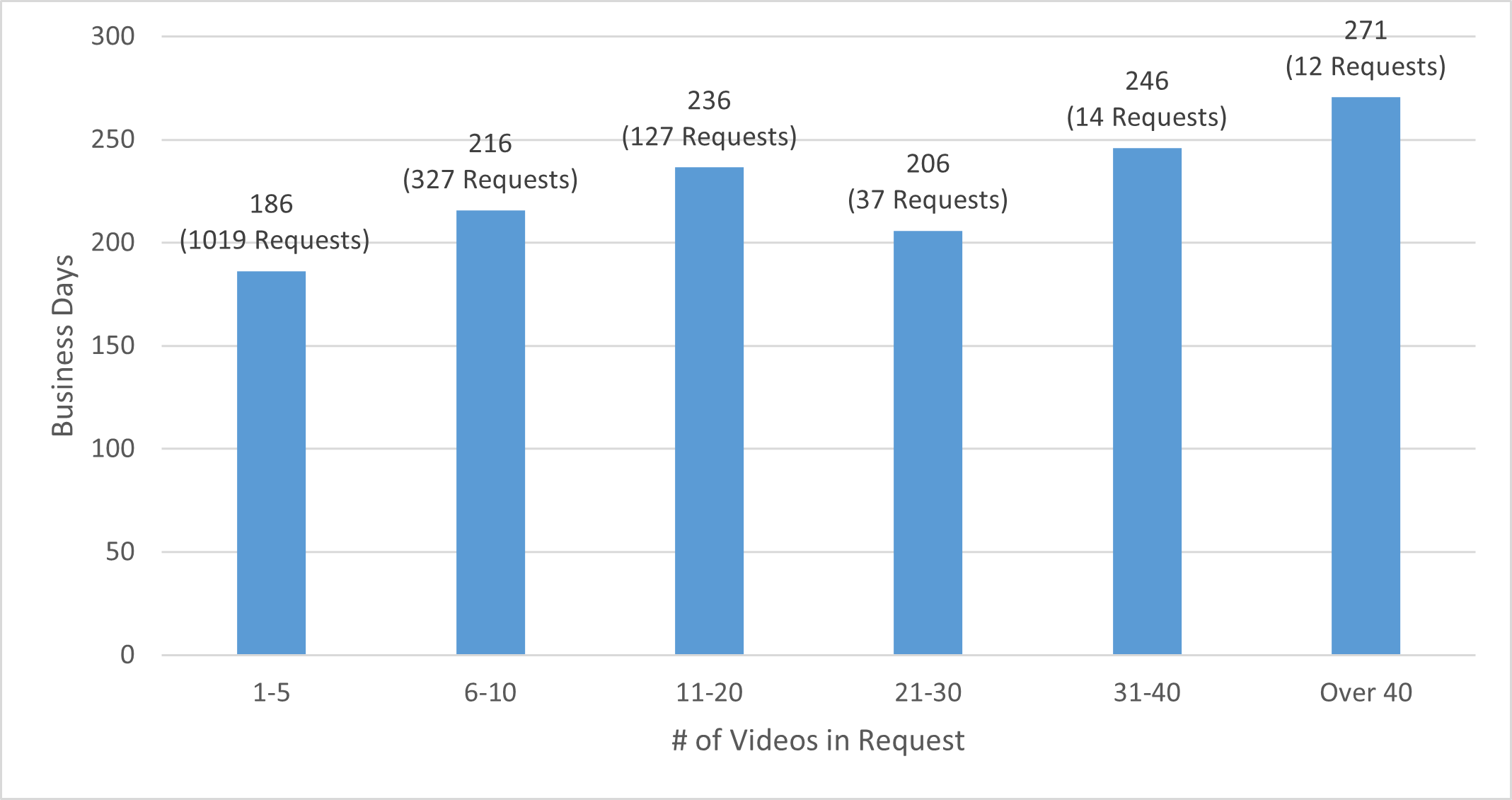

Auditors reviewed 1,536 requests from NYPD’s Log of Releases submitted between CYs 2020 through 2024 and found that as the number of videos per request increased, so too did the average timeframe to provide the footage, as shown in Chart 3 below.

Chart 3: Average Business Days to Grant Request Based on # of Videos in Request

As shown above, for requests that contained one to five videos, NYPD averaged 186 business days to grant the request; for requests with over 40 videos, NYPD averaged 271 business days.

Auditors also reviewed Open Records for the 22 cases that were unresolved for the longest period. All 22 cases had extension comments delineating a new “due date.” Although the dates were all 90 business days from the extension date, the final recorded response period ranged from 342 to 640 business days (a year generally has 260 business days) after the initial due dates.

97% of Denied Footage Requests Were Successful on Appeal

The BWC Unit tracks footage requests it denies in its Log of FOIL Denials. According to the Log, NYPD denied 1,403 requests from CYs 2020 through 2024.[15]

Table 1 below shows a breakdown of the total number of denied requests and the reasons given for each denial in the Log.

Table 1: BWC Footage FOIL Requests Denied by NYPD with Reasons

| Reason | # of Requests | % of Requests Denied |

|---|---|---|

| No 160.50 Waiver[16] | 462 | 33% |

| Interference[17] | 396 | 28% |

| No 160.50/Interference[18] | 100 | 7% |

| Duplicate Request | 251 | 18% |

| No Longer Needed/Obtained Elsewhere | 74 | 5% |

| Other[19] | 120 | 9% |

| Total | 1,403 | 100% |

As shown in the table, 462 requests were denied according to the Log of Denials because no 160.50 waiver was submitted. Of these, 385 were listed as closed according to Open Data. On average it took 109 business days to deny these requests, which is excessive considering NYPD did not need to review footage in these instances, as the reason for denial was a missing form. NYPD should be able to expeditiously determine that a required waiver form is missing and promptly notify the requester.

According to FOIL, anyone denied access to a record can appeal within 30 days from the date the request was denied. First level FOIL appeals are handled by the Records Access Appeals Officer within the NYPD’s Legal Bureau FOIL Unit. The BWC Unit tracks these in its Log of Appeals. According to the Log, NYPD received 355 appeals between CYs 2020 through 2024. Of these, 344 (97%) were granted and only 11 (3%) were denied.[20]

Auditors questioned NYPD officials about the high number of FOIL requests granted following an internal appeal. Officials explained that it generally receives three types of appeals:

- Constructive Denial Appeals: Due to the significant amount of time it takes NYPD to complete requests, requesters file appeals before they receive a determination from NYPD on their original FOIL request. These are generally granted.

- Lack of Criminal Procedure Law 160.50 Waiver Denials: Requesters seeking footage for incidents that have been sealed. In such cases, footage cannot be released without a written waiver from the individual(s) captured in the footage. If the required waiver is not included in the original request, it is denied. This results in appeals that are typically granted once the waiver has been provided. In some instances, footage may be redacted to protect individuals not included in provided waivers.

- Interference with a Criminal Case Denials: Appeals filed instead of re-opening requests at the initial FOIL level when cases mandating interference are resolved.

NYPD officials stated that these three scenarios reflect a high percentage of the appeals it receives. Of the 355 appeals, 52 were in the Log of Denials and 303 were not. Of the 52 that were in the Log, 33 were denied due to either a lack of waivers and/or interference, with 19 closed for other reasons (e.g., duplicate requests, no longer needed, etc.). Auditors compared the datasets and found that, of 303 appeals not in the Log of Denials, only 14 were in the Log of Releases. The remaining 289 (95%) were not in either log, which indicates they were constructive denial appeals. NYPD added that another scenario occurring less often is that, on appeal, NYPD may remove some redactions that it made at the initial FOIL level based upon a more stringent review of its redaction policies.

Footage Often Provided After Denial Is Challenged in Court

Anyone denied a record by NYPD on appeal can challenge the decision in court. Auditors reviewed New York State Courts Electronic Filing (NYCEF) data online and identified 15 cases filed between January 1, 2020 through March 24, 2025, challenging NYPD’s denial of BWC footage (in some cases, other records were also requested). Two of the 15 cases remain pending. Twelve of the 13 cases resulted in NYPD either being mandated by the court to provide the footage (four instances), or NYPD providing the BWC footage to settle the matter (eight instances).[21] Two of the 12 cases also resulted in NYPD being assessed approximately $4,000 and $80,000 in legal fees. The remaining case was dismissed because the petitioner did not submit a required affidavit, so the court lacked the jurisdiction to hear the motion.

Inadequate Oversight of the BWC Program

Although the auditors found that the overwhelming majority of officers who perform patrol duties had been assigned cameras by June 2024, the same level of success was not found when rates of activation were examined, or when the auditors assessed NYPD compliance with policies and procedures requiring or relating to the collection and review of BWC footage.[22]

In addition to specific instances when NYPD’s compliance with the program indicated insufficient or ineffective internal monitoring, the auditors also found that NYPD’s audit and review of data is insufficient to effectively assess and ensure compliance with BWC use policies.

Overall, 36% of Review Determinations Were Missing BWC Footage and 32 Precincts Were Missing between 37% and 72% of Their Footage

NYPD’s Professional Standards Division (PSD) performs Intergraph Computer Aided Dispatch (ICAD) audits of dispatched 911 calls to determine whether officers recorded incidents in their entirety. However, NYPD does not have a formalized policy for conducting these audits. NYPD officials stated that ICAD reviews are conducted as needed based on available resources. The results are communicated to commands for further investigation/remediation, and the bureaus concerned make use of the data to monitor the work of their subunits at the command and Borough levels.

Auditors tallied all ICAD reviews performed by NYPD’s PSD for CYs 2020 through 2024 to determine whether BWCs were turned on during incidents.[23] The auditors’ analysis of ICAD reviews found that 4,319 (36%) of 12,116 review determinations had no corresponding video on file. [24]

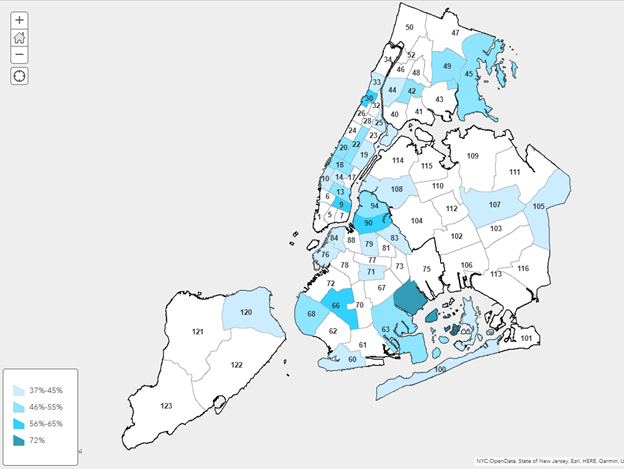

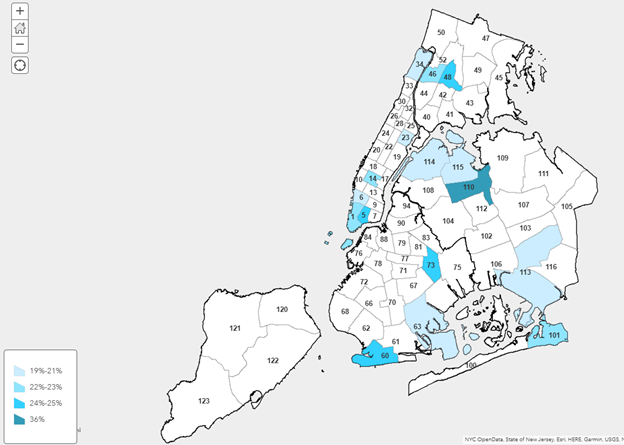

Auditors also aggregated data from ICAD reviews by precinct and found that 32 precincts had higher percentages of no videos on file than the overall average (36%). For 17 precincts the average was between 37% and 45%, for 10 precincts the average was between 46% and 55%, for four precincts the average was between 56% and 65%, and for one precinct the average was 72%. Please see Figure 1 below for a map of the 32 precincts. (Please see Appendix I for a list of the 32 precincts by borough.)

Auditors asked NYPD about these missing videos, and NYPD provided several explanations:

- in some cases, there was no police interaction/involvement related to an ICAD call;

- in some cases, individuals left the scene before officers responded;

- some calls were transferred to another agency (FDNY or EMS); and

- some were categorized as “directed patrols,” during which officers conducted routine inspections of locations (e.g., transit stations, buildings, churches, etc.).

Figure 1: Precincts with a Higher Percentage of BWC Video Missing than the Overall Percentage

Of the 4,319 missing videos, 3,845 (89%) related to circumstances described above. However, NYPD agreed that BWC footage should be available in cases in which officers were actually dispatched and found that the individual had left the scene, as well as for directed patrols.[25] NYPD added that it has been addressing the absence of recordings with the commands at ComplianceStat meetings.

When the call leads to no police interaction, or if the call is transferred to another agency, NYPD stated that there would not be footage associated with these instances, since these calls are coded as such in the ICAD data. However, these remain in the ICAD data and were selected for review. It is unclear why NYPD employees performing the ICAD reviews would not note that footage was not required in these instances, when one of the purposes of the reviews is to determine whether incidents that should be recorded are recorded. Counting a review of such incidents reduces the number of meaningful reviews conducted by the ICAD team. These issues can be attributed to NYPD’s lack of a formalized policy for conducting these reviews, including guidelines for the number, frequency, and sampling plan for reviews.

For the remaining 474 (11%) of 4,319 missing videos, NYPD provided no explanation why video was not on file. These missing videos contravene the NYPD’s stated BWC program goals; it is important that all police actions are recorded and maintained on file to support or dispute any claims made by an officer or civilian.

Incomplete BWC Footage in 18% of Instances Reviewed

Auditors also reviewed NYPD’s ICAD reviews to determine whether BWCs were activated late and/or deactivated early. According to NYPD’s Patrol Guide, recording should begin before the initiation of a police action and must continue until it is concluded. It is important to record the entire incident to ensure that there is a complete contemporaneous record of the event and that officers are complying with the Patrol Guide, and to identify potential improper stops, frisks, searches, and excessive use-of-force incidents.

Based on the ICAD review results, of the 7,797 videos on file, BWCs were activated late and/or deactivated early in 1,436 (18%) instances —specifically, 812 (10%) were activated late, 418 (5%) were deactivated early, and 206 (3%) were both activated late and deactivated early.

Activation Rates Consistently Increased Between 2022 and 2023, but Trends Varied by Borough and Precinct Between 2023 and 2024

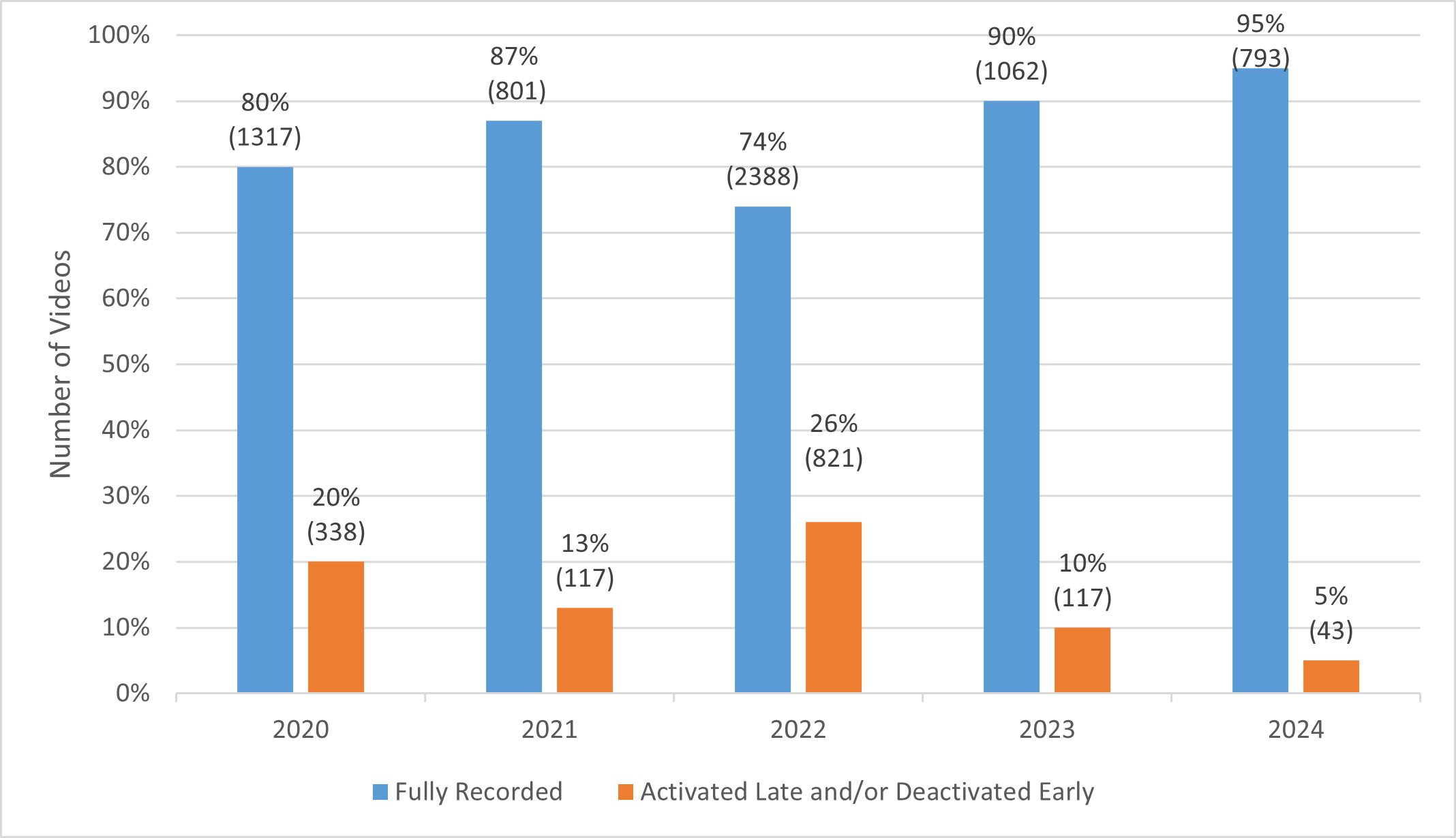

Auditors aggregated the ICAD review results for BWC activation by calendar year, as shown in Chart 4 below.

Chart 4: Results of BWC Activation 2020 through July 2024[26]

As shown in the chart, there were generally better activation percentages in 2023 (90%) and 2024 (95%) than 2020 through 2022. There was a decrease in 2022, when 74% of videos demonstrated proper activation. However, this is likely the result of a major update to the Patrol Guide in July 2022, which required officers to record all police actions instead of only certain radio codes, which meant officers needed time to adjust to this requirement. This is further supported by the significant increase in proper activation rates during 2023 and 2024.

In addition, auditors aggregated the data by borough.[27] As shown below in Chart 5, each borough saw a decrease in proper activation in 2022, followed by a significant increase during 2023, further supporting the likelihood that the decrease was due to officers needing time to adjust to the new recording requirements included in the July 2022 Patrol Guide update.

Chart 5: Results of BWC Activation by Borough (January 2020 through July 2024)

The picture is more varied when comparing activation rates between 2023 and 2024. While proper activation percentages show further increases in Manhattan, Queens, and Staten Island during this period, activation rates fell in Brooklyn and remained flat in the Bronx. Interestingly, based on CCRB data for CYs 2020 through 2023, Brooklyn had the highest number of use-of-force allegations, followed by the Bronx, as well as the largest percentage increase from 2022 to 2023—72% and 69%, respectively.

During the sampled years, the overall rate of incidents recorded in their entirety was slightly lower in Manhattan (77%) than in the outer boroughs, which have nearly identical rates (82% to 85%). Please see Appendix II for full details.

Auditors also aggregated the data by precinct for the sampled years (January 2020 to July 2024). As stated above, 18% of videos were activated late and/or deactivated early. Sixteen (22%) of the 74 precincts had a higher percentage of videos that were activated later and/or deactivated earlier than the Citywide average of 18%, with 13 precincts between 19% and 24%, and three precincts (5th Precinct in Manhattan, 73rd Precinct in Brooklyn, and 110th Precinct in Queens) with 25% or more.[28] Please see Figure 2 for a map of these 13 precincts. (Please also see Appendix I for a list of the 13 precincts by borough.)

Correlation Between Poor Precinct Compliance and Higher Rates of CCRB Substantiated Allegations

Auditors also reviewed CCRB data by precinct for CYs 2020 through 2023 and found a correlation between substantiated allegations of excessive use of force and missing BWC footage and lower activation rates. Of the 23 precincts with more than the average number of CCRB substantiated use-of-force allegations, six (Precincts 33, 42, 44, 60, 79, and 105) were found to have above-average missing BWC footage on file and six (Precincts 46, 48, 60, 73, 101 and 115) were found to have above-average incomplete BWC recordings.

The causal relationship between poor BWC compliance and substantiated allegations of use of force has not been established, but it nonetheless points to a need for NYPD to review and analyze data, and to identify outliers and take targeted action to improve compliance.[29]

Figure 2: Precincts with a Higher Percentage of Late Activation and/or Early Deactivation than the Overall Percentage

NYPD Does Not Aggregate BWC Data or Perform Trend Analysis

According to the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO), organizations should process data into quality information that management can use to make informed decisions. However, NYPD does not aggregate data or perform trend analyses of its Self-Inspections and ICAD reviews for the purpose of gaining insight into, among other things, its BWC activation rates.

When asked why it does not analyze activation rates, NYPD stated that, “Trend analysis of late activation/early deactivation is not accomplished with a data pull. The reviewer must watch the entire video for context before assessing for proper activation/deactivation. This is done only on [an] ad hoc basis for ComplianceStat and cannot be scaled up to the numerous videos captured yearly.”

NYPD’s claim that assessments cannot be “scaled up” is dubious, since the auditors were able to aggregate and perform a trend analysis of all ICAD reviews performed by NYPD for CYs 2020 through 2024. Because NYPD does not perform a trend analysis of this data, the department’s effectiveness and ability to adapt to ongoing situations is hindered. In addition, NYPD has limited assurance that officers who consistently activate BWCs improperly are identified, or that appropriate corrective action is taken when necessary.

By aggregating and analyzing data, based on the reviews it conducts, NYPD would be able to identify trends, such as precincts or Patrol Boroughs with higher rates of noncompliance with BWC activation, and address behavior accordingly. Aggregating data allows for better decision-making, trendspotting, and improved operational efficiency.

53% of Requested Months Missing Records of Self-Inspections of BWC Activation

NYPD’s BWC Self-Inspection Worksheet instructions require that each month, sergeants from all precincts randomly select five videos recorded by their assigned officers during the previous month. The sergeants review these videos and complete a Self-Inspection Worksheet to document their findings (e.g., did officers activate BWC at appropriate time, was police action entirely recorded, was BWC powered on prior to recording, etc.). They must then indicate follow-up actions where necessary.

To determine whether entire incidents were recorded as evaluated by the sergeants, auditors requested all Self-Inspections completed by 11 randomly selected precincts for April, May, and June of 2020 through 2024, totaling 165 individual months of Self-Inspections (11 precincts x 3 months x 5 years). NYPD was unable to provide Self-Inspections for 87—more than half—of the requested months. Table 2 breaks down the number of months for which Self-Inspection worksheets were not received for each precinct.

Table 2: Number of Months by Precinct that Self-Inspection Worksheets Were Not Received

| Precincts | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 14 | 17 | 28 | 42 | 50 | 63 | 67 | 68 | 101 | 112 | 120 |

| 2020 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| 2021 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2022 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2023 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2024 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 12 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

As shown in the table:

- 14th Precinct (Manhattan): Self-Inspections for 12 (80%) of the 15 months were not provided. None were provided for any of the three months requested for four straight years (2020 to 2023).

- 50th (Bronx) and 63rd (Brooklyn) Precincts: Self-Inspections for 11 (73%) of the 15 months were not provided.

- 67th and 68th Precincts (Brooklyn): Self-Inspections for nine (60%) of the 15 months were not provided.

- 17th Precinct (Manhattan): The only precinct for which Self-Inspections were provided for all 15 months.

According to NYPD, the missing 2020 Self-Inspections were not prepared due to the challenges posed by COVID-19 and other events at the time related to civil unrest and the “defund the police” movement. However, two of the sampled precincts were able to complete Self-Inspections for all requested months for 2020, which raises the question why other precincts were unable to do so. NYPD suggested that for the 2021 through 2024 missing Self-Inspections, administrative and personnel changes (such as retirements, promotions, and resignations) resulted in files being unavailable, despite outreach to former command members. NYPD’s claim that the reviews were conducted, despite the absence of documentation, is not persuasive.

Since NYPD does not aggregate the results of its monthly Self-Inspections for the purpose of performing year-to-year trend analyses, auditors attempted to perform an aggregation. However, due to the limited number of Self-Inspections received, the auditors were unable to perform this task.

No Independent Review of Self-Inspections for BWC Activation

In addition to the reviews noted above, each quarter, PSD randomly selects five files for each sergeant within precincts to review when completing the Self-Inspections (instead of the sergeants selecting them themselves). These reviews are conducted the same way as the monthly inspections; however, once completed, they are sent to PSD.

Officials explained that the Self-Inspection results are submitted to PSD, which saves and tracks that a submission was made, but that no independent review of the substance of the results or the commands’ findings is conducted. As indicated above, some Self-Inspections were missing for 2021 through 2024. The auditors requested self-inspections records for 44 quarters (4 years x 11 precincts), but none were provided for eight quarters, during which time PSD should have received one month of self-inspections from the precincts and therefore should have been able to provide at least one self-inspection in these eight quarters. This again raises questions about whether the Self-Inspections were actually performed.

Of the 1,120 Self-Inspections provided, 75 (7%) did not contain the signature of the command’s Executive Officer, as required, suggesting they may not have been reviewed. If PSD had reviewed the Self-Inspections instead of just tracking that they were submitted, it would have discovered the missing signatures.

Officials added that as of 2025, NYPD is including Self-Inspection reviews in ComplianceStat by highlighting commands that failed to submit quarterly Self-Inspections, and that NYPD is open to recommendations for performing a sampled review of Self-Inspection reports.

Since PSD did not conduct any reviews, there is no independent evaluation of the sergeants’ reviews outside of the precinct. Without performing a review of the Self-Inspections, PSD and NYPD executives have limited assurance that the sergeants’ determinations are correct or that the officers are complying with departmental procedures concerning activation of BWCs. Furthermore, PSD has limited ability to identify instances when retraining or other corrective measures are necessary.

Missing Required Reviews of Stops and Related Footage

NYPD’s Stop Report BWC worksheet (802 Worksheet) instructions require that Integrity Control Officers (ICO) from each precinct perform monthly reviews of the precinct’s last 25 Stop Reports. ICOs review the Stop Reports completed by officers, which are subsequently reviewed by their supervisors to determine, among other things, whether the officers followed the law and NYPD procedures, including those related to stop, frisk, and search. ICOs also assess whether the supervisor appropriately reviewed the stop and, if conducted, the frisk and search. Policy requires ICOs to sample the last five Stop Reports and review BWC footage to determine whether there are corresponding recordings available, whether the Stop Report narrative was consistent with the footage, and whether NYPD procedures were properly applied. If Stop Reports or related footage is missing, this review cannot occur.

Auditors requested five months (June of each year from 2020 through 2024) of 802 Worksheets from 11 precincts in total (one worksheet per precinct per month). NYPD could not provide worksheets for 11 (20%) of the 55 requested months, consisting of three precincts: the 50th and 67th Precincts were missing four months each, and the 42nd Precinct was missing three months.

According to NYPD, the missing 802 Worksheets for 2020 were not prepared due to the challenges posed by COVID-19 and other events at the time related to civil unrest and the “defund the police” movement. However, nine of the precincts were able to provide 802 Worksheets for 2020. NYPD again indicated (as it did for the missing self-inspections) that 802 Worksheets from 2021 through 2024 were missing due to administrative and personnel changes (such as retirement, promotions, and resignations), despite NYPD’s outreach to former command members. The absence of such records suggests these reviews were not in fact conducted.

By not holding precinct ICOs accountable for the required submission of 802 Worksheets, PSD limits its capacity to conduct quality assurance reviews of the BWC program or the intended internal uses of BWC footage. PSD cannot be certain that officers and their supervisors appropriately applied the law or departmental guidelines regarding stop, frisk, and search incidents. The auditors also could not perform a year-to-year trend analysis due to the missing worksheets.

NYPD and Monitor Reach Different Conclusions Regarding Appropriateness of Stops, Frisks, and Searches

As noted above, as part of their reviews of 802 Worksheets and the last 25 Stop Reports, ICOs must review related BWC footage to determine (among other things): whether there was a recording; whether the narrative on the report for the stop (and frisk and search, if applicable) was consistent with the footage; and whether NYPD procedures were properly applied. This is one of the methods used by NYPD to assess whether officers comply with stop, frisk and search policy, and by extension, the law.

Based on its internal reviews, NYPD concluded not only that the narratives in Stop Reports and BWC footage were overwhelmingly consistent, but also that there was a valid legal basis to conduct the stop in over 98% of the time (as shown in Table 3 below).

Table 3: Number of Instances ICOs Concluded the Stop Report Narrative Was Consistent with BWC Video

| Is Stop Narrative consistent with video? | Is Frisk Narrative consistent with video? | Is Search Narrative consistent with video? | Did officer appropriately apply the law & NYPD procedures? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 213 | 95.5% | 98 | 94.2% | 110 | 91.7% | 219 | 98.2% |

| No | 4 | 1.8% | 4 | 3.8% | 6 | 5.0% | 2 | .9% |

| Inconclusive | 3 | 1.3% | 2 | 1.9% | 4 | 3.3% | 0 | 0% |

| N/A | 1[30] | .4% | ||||||

| Blank | 2 | .9% | 2 | .9% | ||||

| Total | 223 | 100% | 104 | 100% | 120 | 100% | 223 | 100% |

Of the 223 stops reviewed by the ICOs, it was determined that the officer applied the law appropriately and followed NYPD procedures in 219 (98.2%) of them. The Monitor, however, specifically stated that NYPD supervisors do not assess stops correctly, and reported the following regarding stops in its 21st Report:[31]

- Of the 1,203 stops reviewed in 2020, 14% were found to be unconstitutional;

- Of the 1,211 stops reviewed in 2021, 11% were found to be unconstitutional;

- Of the 1,217 stops reviewed in 2022, 11% were found to be unconstitutional; and

- Of the 611 stops reviewed in the first two quarters of 2023, 12% were found to be unconstitutional.

This difference in conclusions is also apparent in the assessment of frisks and searches.

NYPD’s internal reviews conclude that Stop Report narratives articulate a reasonable suspicion to frisk 87% of the time, and to search 90% of the time, but the Monitor reported the following in its 21st Report:

- In 2020, 6% of frisks and 6% of searches were found to be unconstitutional;

- In 2021, 16% of frisks and 20% of searches were found to be unconstitutional;

- In 2022, 24% of frisks and 30% of searches were found to be unconstitutional; and

- In the first two quarters of 2023, 31% of frisks and 33% of searches were found to be unconstitutional.

According to the Monitor’s February 2025 One-Year Update Letter, in the first half of 2024, NYPD supervisors concluded that 99% of stops, 98% of frisks, and 97% of searches were compliant, but the Monitor’s team found substantially lower rates of compliance with the law during the same period, concluding that 89% of stops, 69% of frisks, and 68% of searches were compliant.

Supervisors Inaccurately Complete Stop Reports

Auditors’ review of 75,743 Stop Reports in the Crime Data Warehouse (CDW) found that supervisors incorrectly and/or inconsistently answered certain questions in Stop Reports, as follows:

- In 1,744 instances, the reports indicated that there was an insufficient basis for the frisk while also indicating that no frisk was conducted in 1,005 (57%) of them.

- In 2,898 instances, the reports indicated that there was an insufficient basis for the search while also indicating that no search was conducted in 1,941 (67%) of them.[32]

- Reports indicated there was instruction/training/disciplinary action taken in instances when they also reported there was no frisk and/or search performed.

In addition, ICOs’ completion of 802 Worksheets indicated there was reasonable suspicion for frisks and searches even when the ICOs also concluded that the stops lacked a reasonable basis. According to NYPD’s policy, if a stop cannot be justified, then a search or frisk cannot be justified. Nonetheless, of the 29 instances in which ICO’s concluded there was an insufficient basis to justify a stop, there were four (14%) instances in which the ICO also concluded that there was reasonable basis to frisk, and a further nine (31%) instances in which the ICO still determined there was reasonable suspicion for the search; in these instances, since the ICO determined the stop was not justified, the related frisks/searches should have automatically also been deemed unjustified.

Reviews of Stops Inaccurately Completed by 64% of Sampled Precincts

According to NYPD procedures, the frisk and search fields on the 802 Worksheets can only be completed with a “yes” or “no,” since the ICO is determining whether the supervisor properly performed their review of the Stop Reports.

However, ICOs at seven (64%) of the 11 sampled precincts incorrectly recorded “N/A” for whether the supervisor appropriately performed their review of the Stop Reports. As shown in Table 4 below, in 128 (28.8%) of the 445 reviews, the ICOs incorrectly recorded N/A in the frisk and search fields.

Table 4: Did the Supervisor Properly Perform Their Review of the Appropriateness of the Stop, Frisk, and/or Search?

| Stop | Frisk | Search | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 413 | 92.8% | 252 | 56.6% | 249 | 56.0% |

| No | 6 | 1.3% | 37 | 8.3% | 40 | 9.0% |

| N/A | 0 | 0.0% | 128 | 28.8% | 128 | 28.8% |

| Blank | 26 | 5.8% | 28 | 6.3% | 28 | 6.3% |

| Total | 445 | 100% | 445 | 100% | 445 | 100% |

As a result of these errors, it is unclear in these instances whether the supervisors properly performed their reviews. Auditors met with ICOs from two of these precincts to explain the errors; both ICOs understood the errors and stated that they will complete the 802 Worksheets properly going forward. Auditors asked NYPD to notify the other five precincts of the errors.

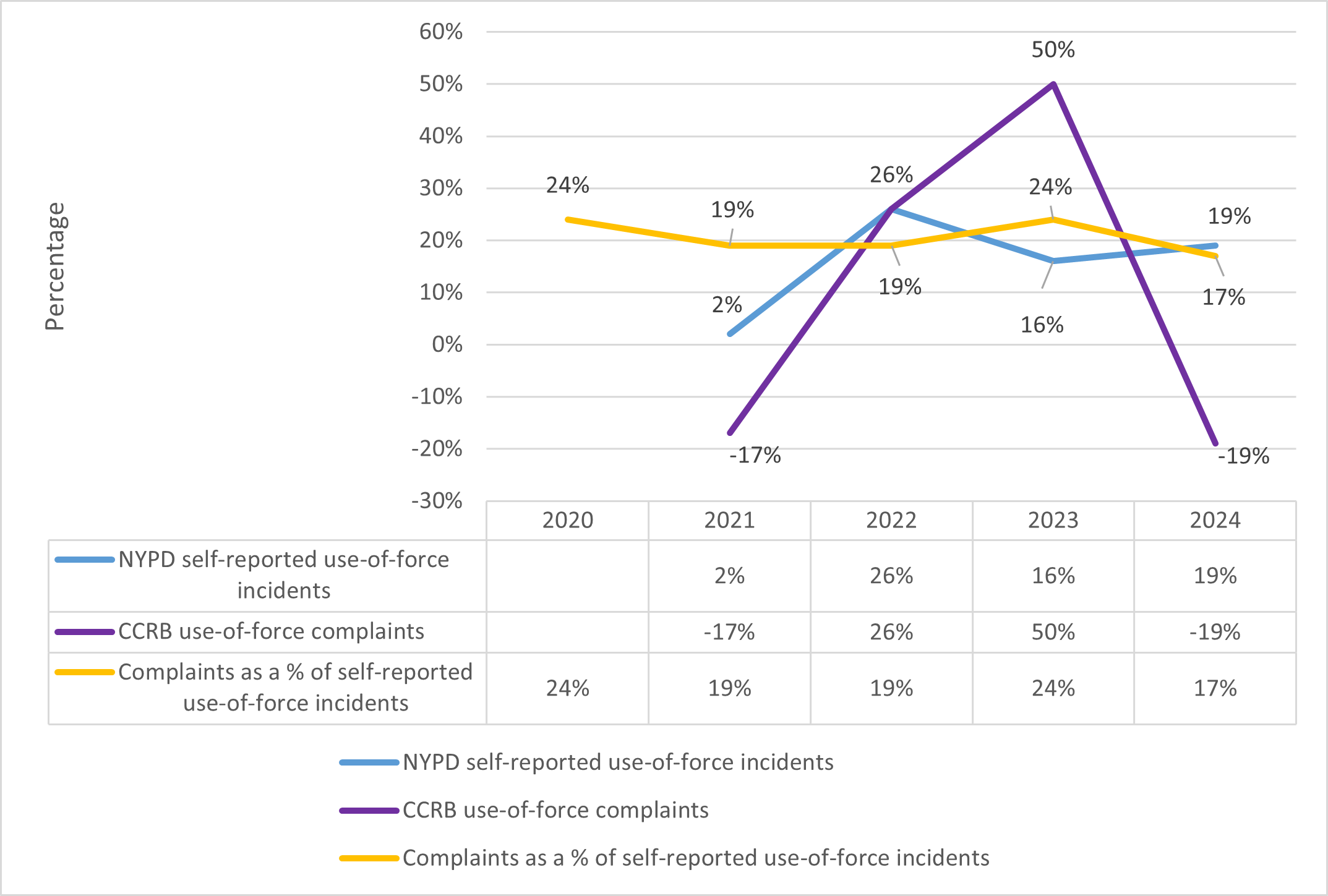

Percentage of Use-of-Force Related Complaints to CCRB Relative to Self-Reported Incidents Ranged from 24% to 17% between 2020 and 2024

According to NYPD’s Patrol Guide, Force Guidelines, force may be used when it is reasonable to ensure the safety of a member of the service or a third person, or otherwise protect life, or when it is reasonable to place a person in custody or to prevent escape from custody. If the force used is unreasonable under the circumstances, it will be deemed excessive and in violation of NYPD policy.[33]

NYPD policy requires that all force incidents be reported on a Threat, Resistance, or Injury (TRI) Incident Report, which includes the type(s) of force used, the officer(s) who used force and/or were subjected to force, any injuries, and any other circumstances surrounding the incident.

Table 5: Comparison of the Number of Reported Use-of-Force Incidents According to NYPD’s Open Data[34] [35] and Use-of-Force Complaints Reported to CCRB

| Year | NYPD # of self-reported use of force incidents | % increase over prior year | # of use of force complaints reported to CCRB | % increase over prior year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 6,706 | 1,582 | ||

| 2021 | 6,862 | +2% | 1,314 | (17%) |

| 2022 | 8,705 | +26% | 1,651 | +26% |

| 2023 | 10,155 | +16% | 2,476 | +50% |

| 2024 | 12,066 | +19% | 2,015 | (19%) |

The auditors also considered the proportionality of self-reported incidents to CCRB complaints and found less pronounced changes, but still showing ups and downs by year. As shown below in Chart 6, the proportion of CCRB complaints relative to self-reported complaints is higher in 2020 and 2023 (24%) and lower in 2021 (19%), 2022 (19%) and 2024 (17%). These represent improvements in three of the five years.

Chart 6: Comparison of NYPD’s Self-Reported Incidents and Use-of-Force Allegations Reported to CCRB

NYPD Does Not Ensure Use-of-Force Incidents Consistently Result in Completion of a TRI Report

According to NYPD’s Patrol Guide, a TRI Report is required to be completed for every use-of-force incident. Although NYPD reviews TRI Reports to determine whether there is corresponding BWC footage as part of its ComplianceStat meetings, NYPD does not independently review BWC footage first, as the primary source, to identify instances when force was used, and subsequently determine whether a TRI Report was completed. This means that unless a TRI Report is submitted, BWC footage of use-of-force incidents is not reviewed as required.

Auditors reviewed CCRB’s substantiated allegations of excessive use-of-force incidents and selected 25 incidents to determine whether there was a corresponding TRI Report. NYPD acknowledged that a TRI Report was required for 17 of the 25 selected incidents; however, for four (24%) of the 17 incidents, a TRI Report was not prepared.

For the remaining eight incidents, NYPD stated that no TRI Report was required. According to officials, when someone files a use-of-force complaint with CCRB, they may sometimes include names of officers who were at the scene as backups to the responding officers, even if they were not directly involved in the incident. Officials further stated that an allegation of force in a CCRB complaint does not necessarily confirm that force was used and therefore does not automatically require the completion of a TRI Report. Although auditors do not disagree with NYPD’s explanation in theory, all incidents in the sample were substantiated by CCRB. Although NYPD’s determinations may not concur with CCRB’s in these cases, the fact that CCRB’s independent review substantiated these allegations indicates that force of some kind was used. According to NYPD policy, a TRI Report is required when any force is used, even if it is found to be reasonable.

It is important to document each use-of-force incident in a TRI Report for analysis and tracking purposes. This helps NYPD determine whether there are any trends in the amount and degree of use-of-force incidents, and whether any corrective actions should be taken to address these incidents.

Recommendations

Based on this review, the auditors have identified several areas for improvement in NYPD’s oversight of the BWC program. NYPD should:

Improve FOIL Response

- Increase Legal Bureau staffing levels and make additional efforts to address FOIL requests timely.

NYPD Response: NYPD agreed with this recommendation.

- Provide timely notice to requesters that a required 160.50 waiver document is missing.

NYPD Response: NYPD agreed with this recommendation.

Improve Administrative Oversight

- Take steps to ensure that all officers who perform patrol duties are immediately provided with cameras.

NYPD Response: NYPD agreed with this recommendation.

- Formalize a policy for conducting ICAD reviews including the number, frequency, and sampling plan of reviews, and include in the methodology that ICAD interactions that are not required to be recorded be excluded from the reviews and replaced with additional samples.

NYPD Response: NYPD agreed with this recommendation.

- Investigate causes of lower activation rates in certain boroughs and precincts and take steps to ensure they continue to improve across the City.

NYPD Response: NYPD agreed with this recommendation.

- Conduct an overall assessment of its BWC program to determine whether the program has improved compliance with policies, regulations, and laws, including respectful interaction with the public.

NYPD Response: NYPD essentially agreed with this recommendation, indicating that it reflects its current practice.

Auditor Comment: While NYPD conducts various types of reviews, it did not conduct an overall assessment of its BWC program. The auditors encourage NYPD to assess whether the program has improved compliance with policies, regulations, and laws.

Aggregate Results of BWC Reviews

- Aggregate the results of its various BWC reviews (e.g., ICAD reviews, Self-Inspections, 802 Worksheets, etc.) to identify anomalies or trends and address them accordingly.

NYPD Response: NYPD agreed with this recommendation.

Improve Completion and Reviews of Documentation

- Ensure that Self-Inspections are completed monthly as required.

NYPD Response: NYPD agreed with this recommendation.

- Ensure independent reviews of Self-Inspections are conducted by PSD.

NYPD Response: NYPD agreed with this recommendation.

- Ensure that 802 Worksheets are completed monthly as required.

NYPD Response: NYPD agreed with this recommendation.

Improve Stop, Frisk, and Search Adherence

- Take additional steps to ensure compliance with its Stop/Frisk policy by identifying improper stops.

NYPD Response: NYPD essentially agreed with this recommendation, indicating that it reflects its current practice.

Auditor Comment: The federal monitor reported that NYPD reached different conclusions regarding the appropriateness of stops. Therefore, the auditors encourage NYPD to take additional steps to ensure accurate assessments of the appropriateness of Stops/Frisks.

Improve Monitoring of Use-of-Force

- Review a sample of BWC footage from Level 2 and Level 3 Investigative Encounters to determine whether force was used and whether a TRI Report was completed, as required.

NYPD Response: NYPD stated that it “will consider this recommendation.”

Auditor Comment: As indicated in the report, NYPD does not independently review BWC footage first, as the primary source, to identify instances when force was used, and subsequently determine whether a TRI Report was completed, but these are necessary steps to ensure internal compliance with its policies. The auditors encourage NYPD to implement this recommendation.

- Ensure that TRI reports are completed for all use-of-force incidents.

NYPD Response: NYPD essentially agreed with this recommendation, indicating that it reflects its current practice.

Auditor Comment: The review found that TRI reports were missing for 24% of the sampled use-of-force incidents. Therefore, the auditors encourage NYPD to take additional steps to ensure TRIs are completed for all use-of-force incidents.

Appendix I

Precincts with Missing BWC Video and/or Late Activation and Early Deactivation Percentages Higher than the Overall Averages

| Precinct | Borough | No Video on File Greater than Overall Average of 36% | Late Activation and/or Early Deactivation Greater than Overall Average of 18% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Precinct | Manhattan | 22% | |

| 5th Precinct | Manhattan | 25% | |

| 6th Precinct | Manhattan | 21% | |

| 9th Precinct | Manhattan | 56% | |

| 10th precinct | Manhattan | 45% | |

| 13th Precinct | Manhattan | 47% | |

| 14th Precinct | Manhattan | 41% | 23% |

| 18th Precinct | Manhattan | 50% | |

| 19th Precinct | Manhattan | 42% | |

| 20th Precinct | Manhattan | 54% | |

| 22nd Precinct | Manhattan | 51% | |

| 23rd Precinct | Manhattan | 21% | |

| 25th Precinct | Manhattan | 42% | |

| 30th Precinct | Manhattan | 56% | |

| 33rd Precinct | Manhattan | 43% | |

| 34th Precinct | Manhattan | 19% | |

| 42nd Precinct | Bronx | 48% | |

| 44th Precinct | Bronx | 40% | |

| 45th Precinct | Bronx | 53% | |

| 46th Precinct | Bronx | 23% | |

| 48th Precinct | Bronx | 24% | |

| 49th Precinct | Bronx | 46% | |

| 60th Precinct | Brooklyn | 44% | 24% |

| 63rd Precinct | Brooklyn | 50% | 19% |

| 66th Precinct | Brooklyn | 58% | |

| 68th Precinct | Brooklyn | 49% | |

| 69th Precinct | Brooklyn | 72% | |

| 71st Precinct | Brooklyn | 45% | |

| 73rd Precinct | Brooklyn | 25% | |

| 76th Precinct | Brooklyn | 42% | |

| 79th Precinct | Brooklyn | 40% | |

| 83rd Precinct | Brooklyn | 40% | |

| 84th Precinct | Brooklyn | 41% | |

| 90th Precinct | Brooklyn | 56% | |

| 94th Precinct | Brooklyn | 52% | |

| 100th Precinct | Queens | 38% | |

| 101st Precinct | Queens | 23% | |

| 105th Precinct | Queens | 37% | |

| 107th Precinct | Queens | 43% | |

| 108th Precinct | Queens | 37% | |

| 110th Precinct | Queens | 36% | |

| 113th Precinct | Queens | 19% | |

| 114th Precinct | Queens | 19% | |

| 115th Precinct | Queens | 19% | |

| 120th Precinct | Staten Island | 40% |

Appendix II

Results of BWC Activation by Borough (2020 through July 2024) – Full Details

| The Bronx | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2020 |

Fully Recorded | 212 | 82% |

257 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 45 | 18% | ||

|

2021 |

Fully Recorded | 137 | 87% |

158 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 21 | 13% | ||

|

2022 |

Fully Recorded | 463 | 78% |

592 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 129 | 22% | ||

|

2023 |

Fully Recorded | 284 | 93% |

307 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 23 | 7% | ||

|

2024 |

Fully Recorded | 69 | 93% |

74 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 5 | 7% | ||

|

Total |

Fully Recorded | 1,165 | 84% |

1,388 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 223 | 16% | ||

| Brooklyn | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2020 |

Fully Recorded | 333 | 79% |

420 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 87 | 21% | ||

|

2021 |

Fully Recorded | 253 | 84% |

300 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 47 | 16% | ||

|

2022 |

Fully Recorded | 676 | 79% |

856 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 180 | 21% | ||

|

2023 |

Fully Recorded | 192 | 99% |

194 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 2 | 1% | ||

|

2024 |

Fully Recorded | 124 | 91% |

136 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 12 | 9% | ||

|

Total |

Fully Recorded | 1,578 | 83% |

1,906 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 328 | 17% | ||

| Manhattan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2020 |

Fully Recorded | 373 | 78% |

479 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 106 | 22% | ||

|

2021 |

Fully Recorded | 203 | 93% |

219 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 16 | 7% | ||

|

2022 |

Fully Recorded | 579 | 66% |

878 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 299 | 34% | ||

|

2023 |

Fully Recorded | 167 | 88% |

190 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 23 | 12% | ||

|

2024 |

Fully Recorded | 184 | 98% |

187 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 3 | 2% | ||

|

Total |

Fully Recorded | 1,506 | 77% |

1,953 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 447 | 23% | ||

| Queens | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2020 |

Fully Recorded | 197 | 77% | 256 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 59 | 23% | ||

|

2021 |

Fully Recorded | 208 | 86% |

241 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 33 | 14% | ||

|

2022 |

Fully Recorded | 394 | 72% |

544 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 150 | 28% | ||

|

2023 |

Fully Recorded | 278 | 83% |

334 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 56 | 17% | ||

|

2024 |

Fully Recorded | 380 | 94% |

403 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 23 | 6% | ||

|

Total |

Fully Recorded | 1,457 | 82% |

1,778 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 321 | 18% | ||

| Staten Island | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2020 |

Fully Recorded | 202 | 83% |

243 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 41 | 17% | ||

|

2021 |

Fully Recorded | 0 | N/A |

0 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 0 | N/A | ||

|

2022 |

Fully Recorded | 276 | 81% |

339 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 63 | 19% | ||

|

2023 |

Fully Recorded | 141 | 92% |

154 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 13 | 8% | ||

|

2024 |

Fully Recorded | 36 | 100% |

36 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 0 | 0% | ||

|

Total |

Fully Recorded | 655 | 85% |

772 |

| Activated Late and/or Deactivated Early | 117 | 15% | ||

Addendum

Endnotes

[1] In Floyd v. City of New York, plaintiffs brought a class action lawsuit against the City and the NYPD alleging that the City’s stop-and-frisk practices violated their Fourth and Fourteenth Amendment rights.

[2] https://www.nypdmonitor.org/resources-reports/.

[3] A police action is any police service as well as law enforcement or investigative activity conducted in furtherance of official duties, including responding to calls for service; addressing quality of life conditions; handling pick-up assignments; and any self-initiated investigative or enforcement actions, such as witness canvasses, vehicle stops and Investigative Encounters. Routine consensual conversations with members of the public carried out as part of community engagement efforts are not considered police action.

[4] Police Executive Research Forum. Implementing a Body-Worn Camera Program: Recommendations and Lessons Learned, 2014.

[5] Once powered on, the BWC automatically records (without audio) in one-minute intervals. When the officer begins recording, the one-minute video is saved and attached to the full video. This is intended to capture a video of an incident just before a recording begins.

[6] A “stop” is a police encounter in which an officer temporarily detains an individual with a reasonable suspicion that they are committing, have committed, or are about to commit a crime. Although not under arrest, the individual is not free to leave. A “frisk” may occur during a stop, when an officer reasonably believes the individual has a weapon and is permitted to pat down the outer clothing. If they feel an object and reasonably believe that it could be a weapon, they can reach inside the clothing to determine whether the object is a weapon. A “search” occurs when an officer puts their hands into an individual’s pockets or clothing, looks inside a bag or container, etc.

[7] PSD is responsible for: (1) assisting in accomplishing NYPD’s objectives by applying a systematic approach to developing and implementing compliance mechanisms; (2) providing objective and independent evaluations to reduce risk, improve operations, and devise corrective solutions to noncompliance; (3) developing and implementing compliance mechanisms to ensure individual and institutional compliance with Department policy, applicable laws, and external oversight; and (4) assessing effectiveness of training and policy in achieving desired risk reduction outcomes and conducting all other independent evaluations at the direction of the First Deputy Commissioner.

[8] One of the many functions of the ICO is to ensure that the patrol supervisor/unit supervisor reviews the Stop Report of the officer who conducted the stop. The ICO also ensures that appropriate actions are taken when necessary. This review may include the assessment of related BWC footage. The ICO then determines if the patrol supervisor/unit supervisor appropriately evaluated whether the information presented reasonably supports the conclusion that the officer’s actions were based upon reasonable suspicion.

[9] When appropriate and consistent with personal safety, officers will use de-escalation techniques to safely gain voluntary compliance from a subject to reduce or eliminate the necessity to use force. If this is not safe and/or appropriate, officers will use only the reasonable force necessary to gain control or custody of a subject. The use of deadly physical force against a person can only be used to protect officers and/or the public from imminent serious physical injury or death.

[10] According to City Charter Section 808(b), the Comptroller’s Office, the Law Department, the Commission on Human Rights (CCHR), CCPC, and CCRB can obtain BWC footage without submitting a FOIL request. CCHR stated that it does not request footage from NYPD. A November 2021 report by the Department of Investigation (DOI) assessed NYPD’s policies and practices of sharing BWC footage with these agencies.

[11] Some requests are sent by mail and are added to Open Records by NYPD.

[12] In its response to the Draft Report, NYPD stated that the review repeatedly uses data from 2020 as a baseline for measuring trends in stops, use-of-force incidents, FOIL compliance, and CCRB substantiations and that doing so is “methodologically flawed” because, due to the COVID 19 pandemic, there was a steep drop in interactions with the public and disruption to the functioning of the criminal justice system. NYPD further stated that any reference to data shifts relative to 2020 should acknowledge limitations of these comparisons. However, as explained to NYPD, the review scope goes back to 2020 because 2020 was the first full year after implementation of the BWC program. In addition, the report makes no mention of data shifts for FOIL compliance.

[13] In its response to the Draft Report, NYPD objects to the use of the 25-day timeline as the benchmark for FOIL compliance and asserts that, based on case law, it is always entitled to comply within 95 days. However, case law is based on individual cases and establishes legal precedent for cases with similar facts, and not all cases are similar. Further, NYPD does not acknowledge that it fails to meet even the 95-day timeframe most of the time.

[14] In its response to the Draft Report, NYPD complains that the auditors ignored the extraordinary increase in FOIL requests between 2018 and 2024; however, the obligation is a legal one that does not vary based on the volume of requests. NYPD should have increased resources to keep up with demand.

[15] The log is based on FOIL # (which includes the year) rather than Date of Request, because for some 2020 FOIL #s, the log shows a 2019 Date of Request, and for some 2019 FOIL #s, the log shows a 2020 Date of Request.

[16] Footage shows an arrest/summons. Prosecution has ended and resulted in the footage being sealed. Sealed footage cannot be released without a 160.50 waiver obtained by the requester, which NYPD was not provided.

[17] Footage shows an arrest/issuance of a summons that was still being prosecuted or open in court. NYPD denied the request pending prosecution of the arrest/summons.

[18] Applies to various scenarios (e.g., the footage may involve multiple individuals; one individual’s arrest may have been open so interference was cited, and another individual’s arrest may have been closed and sealed and no 160.50 waiver was provided).

[19] Includes various reasons (e.g., medical privacy, the request contained insufficient information, etc.).

[20] In its response to the Draft Report, NYPD notes that over 85% of the appeals resulting in reversal were constructive denials, and it objects to the report’s presentation of this issue. However, the report clearly identifies the number of constructive denial appeals and explains what that means.

[21] In its response to the Draft Report, NYPD objects to the report’s conclusion that its FOIL denials were frequently overturned on the basis that the number of court challenges is small, but the report cites the full population of cases that were identified after a search of the New York State Courts Electronic Filing data.

[22] Of the 19,598 officers who perform patrol duties, 835 (4%) were not assigned a BWC, according to data provided by NYPD. The department stated that 820 of those officers were not required to be assigned a BWC and provided documentation to support this (e.g., some were ranked Captains or higher, some were on terminal or military leave, etc.). The remaining 15 were not assigned a BWC as of the time the June 2024 report was generated. In August 2024, NYPD provided the auditors with documentation showing that the remaining 15 officers had been assigned BWCs.

[23] NYPD uses ICAD, which is part of the 911 system, as its primary system for managing calls, dispatching assistance, and tracking incidents.

[24] In its response to the Draft Report, NYPD objects to the finding related to missing BWC footage. However, the report notes that the 36% was based on the ICAD review determinations, and the results were not extrapolated to represent the overall condition throughout NYPD.

[25] NYPD explained that in some instances 911 callers sometimes call back and advise that a NYPD response is no longer needed.

[26] Data as of July 2024, when it was received by the auditors.

[27] No ICAD reviews were performed in 2021 for Staten Island.

[28] ICAD reviews were conducted for 74 of the 78 precincts.

[29] In its response to the Draft Report, NYPD claims the report suggests a link between substantiated allegations of excessive use of force and missing BWC footage even though the report acknowledges that “the causal relationship between poor BWC compliance and substantiated allegations of use of force has not been established.” There may in fact be a causal connection but that was outside the scope of the review. NYPD should use data comparisons to identify precincts with higher levels of noncompliance and assess impact on substantiated allegations of use of force. The correlation is concerning.

[30] This “N/A” is likely an error by the ICO, as this column should only be completed with a “yes” or “no.”

[31] In its response to the Draft Report, NYPD stated the ICOs and the Monitor are not looking at the same set of stops and then later stated that there is no guarantee that these samples include the same stops. However, the report does not state that the Monitor reviews the same Stop Reports as the ICOs. This information was used to illustrate the point made by the Federal Monitor in its Twenty-First Report, Monitor’s Compliance Report, September 4, 2024, that NYPD supervisors do not assess stops correctly.

[32] In its response to the Draft Report, NYPD objects that the report makes much of the discrepancies identified in the ICO self-assessments. However, it is important for ICOs to correctly complete assessments. Auditors are encouraged that NYPD has taken steps to clarify the self-assessment form.

[33] When appropriate and consistent with personal safety, officers should use de-escalation techniques to safely gain voluntary compliance from a subject to reduce or eliminate the necessity to use force. If this is not safe and/or appropriate, officers should use only the reasonable force necessary to gain control or custody of a subject. The use of deadly physical force against a person can only be used to protect officers and/or the public from imminent serious physical injury or death.

[34] Open Data is free public data published by City agencies and other partners.

[35] Data is based on information captured on TRI Reports.