Executive Summary

Over the past decade, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has played a central role in expanding access to safe, affordable credit and banking services. Created in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the CFPB has protected millions of Americans through rulemaking, enforcement, and transparency tools.

The Bureau introduced landmark rules across the consumer financial marketplace, including around payday lending, overdraft and credit card fees, buy-now-pay-later products, data privacy, credit reporting, and prepaid accounts. Through enforcement actions against abusive financial service providers, it has secured approximately $20 billion in direct consumer relief and an additional $5 billion in civil penalties.

Today, the CFPB is in crisis. Under the Trump administration and aided by a Republican-led Congress, the agency has been severely weakened. Key consumer protections have been repealed—some permanently—and enforcement actions have ground to a halt, signaling to bad actors that the federal government is unlikely to hold them accountable. In April 2025, nearly 90 percent of the Bureau’s staff were laid off, leaving the agency effectively inoperative.

With the CFPB gutted and other federal financial regulators in retreat, the federal government is no longer equipped to safeguard consumers. States and cities must step in to fill the gap. While preemption and other legal and operational barriers prevent them from replicating everything the CFPB once did, state and local governments have a range of tools to combat abusive financial practices and preserve access to safe, affordable financial services.

New York State and New York City have strong foundations of consumer protection to build on. The State’s Department of Financial Services (DFS) and the City’s Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP) are among the country’s most active regulators. The state has strong usury laws that have prevented payday lenders and other predatory products from establishing a foothold in the state. New York has also banned the reporting of medical debt to credit bureaus and maintains strong protections around debt collection at the state and city level.

At the same time, New York has notable gaps in its consumer protection laws. The state’s primary consumer protection law, New York General Business Law § 349, is among the weakest in the country. And legal loopholes have allowed other ultra-high-cost lenders to evade state usury law, leaving customers facing excessive fees and unexpected debt accumulation. Combined with decades of case law further limiting consumer protection, and limited resources at enforcement agencies, these gaps leave New Yorkers susceptible to financial harm.

This report outlines how New York State and New York City can take action to strengthen consumer financial protection and fill some of the regulatory and enforcement gaps left by the gutting of the CFPB. The analysis draws upon interviews with consumer advocates, financial policy experts, and city, state, and federal regulators; original data analysis; and nationwide policy research, including consumer finance policy in other states. The analysis builds upon the Comptroller’s February Spotlight, which explored trends in banking and credit access in New York City.[1]

This report identifies five priority areas where State and City action is both necessary and feasible, outlined below:

- Regulatory and Enforcement Gaps

New York has one of the weakest consumer protection statutes in the country. Most states prohibit unfair and deceptive acts or practices (UDAP), and the federal government and some states also prohibit “abusive” acts or practices (UDAAP). New York’s consumer protection law, on the other hand, only bans deceptive conduct, limiting the scope of protections available to consumers. In addition, the law’s minimal penalties, ambiguous application to small businesses and nonprofits, and hundreds of judicial rulings that have narrowed its enforceability leave consumers at risk—especially as the federal government abdicates its regulatory responsibilities.

Recommendations:

- Pass the FAIR Business Practices Act (A8427, sponsored by Assembly Member Micah Lasher), which would update N.Y. GBL § 349 to prohibit unfair and abusive practices, expand coverage to small businesses and nonprofits, and increase penalties.

- Fully fund the Attorney General’s Office, the State’s Department of Financial Services (DFS), and the City’s Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP) to ensure they have the resources to absorb increased enforcement responsibilities.

- Set up a statewide “Consumer Protection Restitution Fund” which collects a portion of civil consumer penalties in order to compensate harmed victims who cannot receive restitution from the defendant.

- Banking Access and Affordability

Despite steady progress over the past 10-15 years, many low-income and immigrant New York households remain unbanked or underbanked and rely on costly alternatives. Recent CFPB rules made banking more affordable by limiting excessive fees, but have now been repealed or made unenforceable. The State and City have made some strides in expanding bank access through programs like “Bank On” and Banking Development Districts, but consumer awareness and utilization remain low. Proposed state-level legislation offers additional opportunities to improve bank access in underserved communities and among vulnerable groups.

Recommendations:

- New York State should adopt DFS’s proposed rules limiting overdraft and non-sufficient fund (NSF) fees at state-chartered banks.

- Enact state-level legislation to improve bank access among underserved groups, including measures to require the acceptance of IDNYC as valid identification, mitigate against discriminatory account closure, and provide targeted support for minority depository institutions and credit unions.

- Leverage the City’s and State’s business relationships with banks—via the NYC Banking Commission and via state agencies including DFS and the Office of the State Comptroller—to promote bank accessibility and affordability.

- Expand funding for Banking Development District (BDD) programs and incentivize extra service provision at BDD branches, with a focus on minority depository institutions and credit unions.

- Promote the awareness and adoption of “Bank On” accounts, particularly in underserved communities.

- Non-Bank Financial Products

Emerging fintech products like Earned Wage Access (EWA) offer legitimate use cases in providing short-term liquidity but frequently replicate predatory lending dynamics. These products skirt existing regulatory frameworks and are often riddled with hidden fees and manipulative practices. Other more traditional (non-fintech) products such as rent-to-own and merchant cash advances also circumvent state usury laws, leaving consumers vulnerable.

Recommendations:

- Pass the End Loansharking Act, sponsored by Senator Samra Brouk and Assembly Member Steven Raga), which would bring ultra-high-cost lending products like EWA, rent-to-own contracts, litigation advances, and merchant cash advances under the purview of state lending and usury laws.

- Reject legislative efforts to merely license EWA or similar products without classifying them as loans or limiting excessive fees.

- For all newly emergent consumer lending products, require upfront disclosure of APR-equivalent fees, prohibit deceptive pricing structures (such as soliciting tips), and impose limits on subscription-based lending.

- Consumer Rights

New Yorkers lack strong legal protections to control how financial companies use their personal data. A 2024 CFPB rule granting consumers greater data rights is likely to be vacated under the current federal administration. Other states like California and Oregon offer useful models for protecting consumer data rights, though in many cases financial institutions are at least partially exempt from these regulations.

Recommendations:

- Following the lead of California and Oregon, update New York’s privacy laws to clearly stipulate consumers’ right to access, correct, delete, and limit the sale or use of their personal data.

- Ensure that financial institutions are not exempt from state-level privacy protections, closing the gaps left by federal law.

- Consumer Outreach and Engagement

Although the City and State’s regulatory powers are limited compared to the federal government, they are uniquely well-positioned to reach individuals and families directly, especially those most vulnerable to financial harm. Targeted outreach and individualized support can increase New Yorkers’ awareness of affordable banking options. The CFPB’s public consumer complaint database has become a cornerstone of transparency and accountability in the consumer financial system, but its future is unclear. States and cities have the opportunity to replicate this tool, should the Bureau’s complaint system become inoperative or ineffective.

Recommendations:

- Establish a statewide or citywide public consumer complaint database if the CFPB’s platform becomes inoperative or ineffective.

- Increase public awareness of safe, low-cost banking options through targeted outreach and education.

While the State and City cannot replace the CFPB, there are, as this report demonstrates, a variety of opportunities for New York to better protect its residents from financial exploitation. Given the federal government’s rapid withdrawal from its regulatory responsibilities, New York policymakers must act quickly to protect consumers and build a more fair and resilient consumer financial system.

Background

Trends in Consumer Financial Access in New York

As detailed in the Comptroller’s Office’s February Spotlight, the share of New Yorkers without bank accounts has steadily declined over the past fifteen years, as has the share who rely on high-cost nonbank financial services. Yet in spite of overall progress, gaps in access remain: New York City still has a higher share of unbanked households than other cities and the U.S. as a whole. As the Spotlight demonstrated, low-income households are much more likely to be unbanked: 24 percent of households making less than $30,000 a year are unbanked. That share drops to 4 percent for households making $30,000-75,000, and less than 0.5 percent for households making more than $75,000. The unbanked rate also varies by race: even after controlling for income, Black and Hispanic households are more likely to be unbanked than their white and Asian counterparts.

The increase in access to mainstream financial services both in New York City and nationwide may be partially attributable to technological advancement, such as online and mobile banking. Per the Comptroller’s Office’s analysis, the share of banked New York households accessing their account from a computer rose from 36 percent in 2013 to 57 percent in 2023, and mobile (i.e. cellphone) banking usage increased from 20 percent to 67 percent over the same period.

However, mobile and online banking are less common for low-income households: in 2023, 26 percent of New Yorkers had household income below $30,000, but they made up only 13 percent of mobile and 10 percent of online banking users. This suggests that greater technological access does not fully explain the increase in banking use, particularly among low-income households.

Importantly, major changes to consumer financial regulation and enforcement have also taken place over the past decade. Many of the landmark policy changes have come from federal action, particularly through the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).

The CFPB’s Rise and Retreat

Prior to the inception of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the consumer financial market was loosely regulated by seven federal agencies: the Federal Reserve Bank, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Office of Thrift Supervision, the National Credit Union Administration, the Federal Trade Commission, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Each agency regulated aspects of banks and other financial institutions, but none had a primary focus on consumer financial protection. This system of fragmented regulation and enforcement led to regulatory gaps, inconsistent oversight, and ineffective rulemaking and enforcement.

The CFPB was created in 2010 by the Dodd-Frank Act to unify consumer financial protection under one primary regulator. In the years since, the Bureau has transformed the consumer financial industry—strengthening trust and resiliency in the market, cracking down on some of the industry’s most predatory and abusive practices, and recovering billions in penalties and consumer relief from bad actors.

Much of the CFPB’s impact has come from its rulemaking authority. Over the past ten years, the CFPB has issued rules to strengthen consumer rights and protections for a number of financial products and practices, including buy-now-pay-later products, financial data privacy rights, credit reporting, overdraft fees, prepaid accounts, and credit card late fees.

The Bureau has also taken enforcement actions against companies that have violated regulations and consumer rights. As of January 2025, the CFPB has filed hundreds of enforcement actions, obtaining nearly $20 billion for consumers across several types of relief including monetary compensation and canceled debts. Violators have been collectively ordered to pay an additional $5 billion in civil money penalties.

The CFPB’s consumer protection efforts have been highly affected by the national political climate. Created in 2010, the agency was highly active during both President Obama and President Biden’s administrations under directors Richard Cordray and Rohit Chopra, respectively. However, it has been repeatedly weakened during both of President Trump’s terms. During the first Trump administration, acting director Mick Mulvaney froze enforcement action and weakened the CFPB’s existing rules. In 2020, director Kathy Kraninger rescinded part of a 2017 rule that required payday and other high-cost lenders to assess a consumer’s ability to repay before issuing a loan, exposing vulnerable consumers to predatory lenders.

In February 2025, President Trump appointed Russell Vought as the CFPB’s acting director. Vought then closed the CFPB’s headquarters, ordering employees to stop work and not pursue any new or existing investigations. Elon Musk, head of the then-newly created Department of Government Efficiency, advocated for the CFPB to be abolished entirely. A few days later, the Trump administration paused CFPB layoffs after a federal judge’s order. Then, in mid-April, the administration laid off nearly 90 percent of the CFPB’s 1,700 employees in a single day, effectively shuttering the agency.

Congress is currently using the Congressional Review Act to nullify CFPB rules, which would prevent similar rules from being created in the future without Congressional legislation. On May 9, Trump signed measures repealing two CFPB rules that had been established during the Biden administration: the Overdraft Rule that limited the overdraft and NSF fees that could be charged by very large financial institutions, and the Payment Apps Rule that provided supervision for large nonbank companies that offer digital consumer payment applications.

Congressional Republicans are also attempting to overturn 2024 CFPB rules that banned medical debt from appearing on consumer credit reports and set quality control standards for automated valuation models used by mortgage originators. Both the House and Senate also introduced bills in late January that would defund the CFPB, which is funded by transfers from the Federal Reserve System.

In addition to seeking the repeal of established CFPB rules, the Bureau under Trump has also canceled enforcement actions that would have provided billions of dollars in relief to consumers who had been subject to unfair, deceptive, and abusive practices. A case against Capital One alleged the bank had cheated customers out of $2 billion through its dishonest marketing about its savings account interest rates. Another case against Rocket Homes Real Estate alleged that the company provided illegal kickbacks to real estate agents. The CFPB has also dropped a lawsuit against SoLo Funds, an online lender that the agency had accused of deceiving borrowers and imposing unlawful fees.

Nonetheless, “the CFPB is not dead yet,” said a former CFPB regulator we spoke with; “We see the Bureau as being on administrative leave, and there are ongoing efforts to save the agency.” In the meantime, however, state and municipal policymakers will have to consider how they can keep consumers safe and continue to expand access to safe and affordable financial services.

Charting the Consumer Protection Landscape

In this section, to better understand the consumer protection landscape, we review major developments in the consumer financial market over the past 10 to 15 years, identifying limitations and pointing toward opportunities for future legislative, regulatory, and administrative action. Our analysis draws upon a comprehensive review of rulemaking and enforcement actions at the CFPB and other federal regulators; a scan of policy developments and advocacy at the state and city level, both in New York and nationwide; original and secondary data analysis; and interviews with regulators, consumer advocates, and industry stakeholders. We group our findings into five buckets: (1) regulatory and enforcement gaps; (2) banking access and affordability; (3) non-bank financial services; (4) consumer rights; and (5) consumer outreach and education.

Regulatory & Enforcement Gaps

New York has among the weakest state consumer protection laws, leaving residents without critical avenues for recourse

Although New York City has less regulatory enforcement power than New York State, both have agencies that enforce consumer protection laws. New York State’s Department of Financial Services (DFS) regulates financial institutions, including state-chartered banks, and enforces state-level consumer financial protection laws for those institutions. The state Office of the Attorney General (OAG) investigates consumer complaints and files suits against financial institutions that violate consumer protections.

At the city level, New York City’s consumer protection laws are enforced by the Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP), which licenses businesses across many industries and enforces both consumer and workplace laws. DCWP also operates the Office of Financial Empowerment, which provides resources, education, and outreach to improve consumers’ financial health.

Most states’ consumer protection laws prohibit businesses from engaging in unfair (alternatively, “unconscionable”) or deceptive acts or practices (UDAP). Since the passage of Dodd-Frank, the federal government has also prohibited financial providers from engaging in unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts and practices (UDAAP), as has California. The addition of the abusive standard provided a foundation for many of the CFPB’s regulatory and enforcement actions.

The Dodd-Frank Act, sets out the elements necessary for each term:

- Unfair Acts or Practices: (1) the act or practice causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers, (2) the injury cannot be reasonably avoided by consumers, and (3) the injury is not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition.

- Deceptive Acts or Practices: (1) the representation, omission, act, or practice misleads or is likely to mislead a consumer, (2) the consumer’s interpretation of the representation, omission, act, or practice is reasonable under the circumstances, and (3) the misleading representation, omission, act, or practice is material.

- Abusive Practices: the act or practice:

- materially interferes with the consumer’s ability to understand a term or condition of a consumer financial product or service; or

- takes unreasonable advantage of:

- a lack of understanding on the part of the consumer of the material risks, costs, or conditions of the product or service;

- the inability of the consumer to protect the interests of the consumer in selecting or using a consumer financial product or service; or

- the reasonable reliance of the consumer to on a covered person to act in the interest of the consumer.

New York’s General Business Law Section 349 (GBL § 349) is one of the weakest consumer protection laws in the country. A 2018 report from the National Consumer Law Center (NCLC) on state consumer protection laws flagged New York as one of nine states with major gaps in consumers’ ability to enforce UDAP statutes (the provisions enforceable by consumers only include a prohibition on deceptive acts), and one of seven states where consumers have to also prove impact on the public in order to pursue legal action, not just individual harm.

As shown in Chart 1, taken from the NCLC report, New York is one of the few states considered to have major gaps in consumers’ ability to enforce against violations, in large part because it requires consumers to show that a business’s practices impact consumers frequently or as a whole. Because of this limitation, consumers alleging violations cannot receive relief for a single instance of harm. New York has dismissed hundreds of cases where the consumer was only alleging personal harm from a business, not harm to all consumers.[2]

Chart 1. States with major gaps in consumers’ ability to enforce UDAP statutes (National Consumer Law Center)

Source: “Consumer Protection in the States” (2018), National Consumer Law Center.

“It’s hard to overemphasize just how difficult the lack of a complete UDAAP statute makes things in New York,” said a former CFPB attorney who has also worked on consumer protection in New York State. Because New York prohibits deceptive practices, but not unfair or abusive ones, consumers are only protected from business practices that involve deliberately misleading information.

With these gaps, consumers are susceptible to a host of practices that are illegal in most other jurisdictions. A 2012 report from the CFPB cited a case the FTC brought against a mortgage company that failed to release liens after consumers had fully paid their mortgages. This was categorized as an unfair practice but did not meet New York’s standard for deceptive practices and therefore did not violate GBL § 349.

New York’s Attorney General has proposed the Fostering Affordability and Integrity through Reasonable (FAIR) Business Practices Act (A8427, sponsored by Assembly Member Micah Lasher). The FAIR Business Practices Act would revise GBL § 349 to include prohibitions on both unfair and abusive business acts or practices, in addition to the existing prohibition on deception. It would also confirm that GBL § 349 applies to small businesses and non-profits, in addition to individuals, and to residential property transactions (e.g. mortgages). The FAIR Act would also empower the state attorney general’s office to bring action against any person or business operating in New York, regardless of whether they are located in New York. The current provisions of GBL § 349 set fines of $50 per violation, but the FAIR Act would increase the fine to $1000 per violation plus actual damages, with additional damages awarded if the defendant is found to have “willingly or knowingly” violated the Act.

With the expansion of GBL § 349, the state would be able to enforce a wider range of violations and pursue relief for more consumers. In practice, however, it would be doing so without a guaranteed increase in staff or funding. “The FAIR Business Practices Act fixes the consumer protection law in a lot of ways, but it doesn’t necessarily increase the state’s investigative capacity,” said a consumer protection attorney. The attorney general’s office is also burdened with extra enforcement responsibility because of the federal government’s recent stated unwillingness to address violations. The state’s enforcement abilities may therefore be constrained by a lack of additional resources as it takes on responsibilities that formerly fell to the federal government.

Another gap in New York’s enforcement framework for consumer protection is the absence of mechanisms to ensure restitution for harmed consumers when offending companies become insolvent or otherwise unable to pay. In these cases, victims often cannot recover financial compensation they are owed, despite enforcement action ruling in their favor.

To address this problem at the federal level, the CFPB created a Civil Penalty Fund that collects penalties from companies that have violated consumer protection laws and uses those funds to compensate victims who otherwise could not receive their restitution. California similarly established a Consumer Fraud Restitution Fund, and Minnesota has introduced legislation to do the same. These programs offer potential models for New York to establish a similar fund.

Banking Access and Affordability

Federal rollbacks have stalled progress on banking access and affordability, leaving New York to take the lead

The Office of the NYC Comptroller’s recent Spotlight on consumer credit access found that 7.6 percent of New York City households (about 275,000) and 5.1 percent of New York state households (about 418,000) are unbanked—a population that is disproportionately very-low-income (with annual income under $30,000) and Black or Hispanic. The unbanked rate is also higher in New York City than in other major cities and nationwide. Among New Yorkers, the most frequently cited barriers to bank account access are high fees and prohibitive minimum balance requirements.

Although hundreds of thousands of households remain unbanked, access to mainstream banking and credit has improved over the past 15 years, especially for low-income households and communities of color. This shift is attributable in part to targeted regulatory initiatives designed to enhance bank affordability.

Indeed, federal regulators have made strides to improve bank affordability since the 2010s. As one example, in 2020 several federal financial regulators jointly encouraged supervised banks to offer consumers small-dollar installment loans and lines of credit up to $1,000 at affordable rates. This initiative significantly increased small-dollar credit availability: according to Pew Research, six of the eight largest banks now offer such loans, whereas none did five years ago.

In early 2024, the CFPB finalized a major rule reducing maximum allowable credit card late fees from $41 to $8 and prohibiting adjustments for inflation, winning substantial savings for consumers. However, this rule was vacated in April 2025 after a federal court consent judgment, leaving consumers once again vulnerable to costly fees.

Similarly, a 2024 CFPB rule capped overdraft fees at large financial institutions, offering banks the choice between applying longstanding lending laws to overdrafts (including the disclosure of effective interest rates), limiting fees to $5, or charging fees that match the actual cost of providing the service. Following the introduction of these initiatives, many banks voluntarily reduced overdraft fees dramatically, and the overall value of annual overdraft fees fell from $11 billion to $6 billion. Congress repealed this overdraft protection in May 2025 via the Congressional Review Act, barring the CFPB from reissuing a similar rule without legislation—despite objections from 23 state attorneys general.

In 2024, the CFPB also proposed a rule to restrict nonsufficient funds (NSF) fees, which penalize consumers for attempting a purchase with insufficient funds even when the transaction is immediately declined (and thus no overdraft loan is actually extended). In January 2025, however, the CFPB withdrew the proposed rule.

Given jurisdictional limitations and preemptions, the State cannot fully replace these now-ineffective protections. New York’s Department of Financial Services (DFS) can only regulate state-chartered banks, excluding nationally or out-of-state chartered institutions from its oversight. Furthermore, federal preemption limits New York’s authority over certain products like credit cards issued by out-of-state companies.

Still, New York State and New York City have tools to improve bank affordability and accessibility. As of late 2023, New York has 78 state-chartered banks, thrifts, and credit unions, representing 1,846 branches and approximately $661 billion in deposits within the state’s regulatory purview. Consumer financial policy in other states offers some useful models for New York policymakers to improve affordability. Additionally, the State and City have multiple non-regulatory points of leverage—including the NYC Banking Commission and the Banking Development District program—to promote bank accessibility among both state-chartered and non-state-chartered banks.

State regulators have taken steps to rein in high overdraft and nonsufficient funds (NSF) fees

The State Department of Financial Services (DFS) has actively addressed overdraft fees and nonsufficient funds (NSF) fees at state-chartered banks through regulatory action. In July 2022, DFS issued guidance categorizing specific overdraft practices—such as Authorize Positive Settle Negative (APSN) fees and charging multiple NSF fees for a single transaction—as unfair or deceptive.

Building on this, DFS has proposed a rule to limit overdraft and NSF fees—prohibiting fees on overdrafts of less than $20, fees that exceed the overdrawn amount, over three overdraft or NSF fees per consumer account per day, fees on “Authorize Positive Settle Negative” transactions (also known as APSN, in which the consumer’s balance is sufficient for a purchase at the time of transaction, but not at the time of settlement), and fees on transactions that were immediately declined, among other protections. If finalized, DFS’ proposed rule would position New York as a national leader in overdraft protection.

Chart 2 below depicts the results of a 2021 DFS survey of New York-regulated financial institutions. The survey found that found 81 percent of institutions charged overdraft fees and 68 percent charged NSF fees, while only 34 percent offered low-cost bank accounts like Bank On (discussed in further detail below), highlighting the importance of state-level intervention.[3]

Chart 2

Data from a DFS survey of 60 New York-regulated banks, credit unions, and trust companies.

Source: New York State Department of Financial Services

In September 2024, California enacted two key pieces of legislation targeting excessive overdraft fees. One law prohibits NSF fees on transactions that are immediately declined, including those at ATMs, while another imposes stricter fee disclosure requirements and caps overdraft fees at $14 for state-chartered credit unions.

Bank On accounts are a promising tool for financial inclusion—but low awareness limits their reach

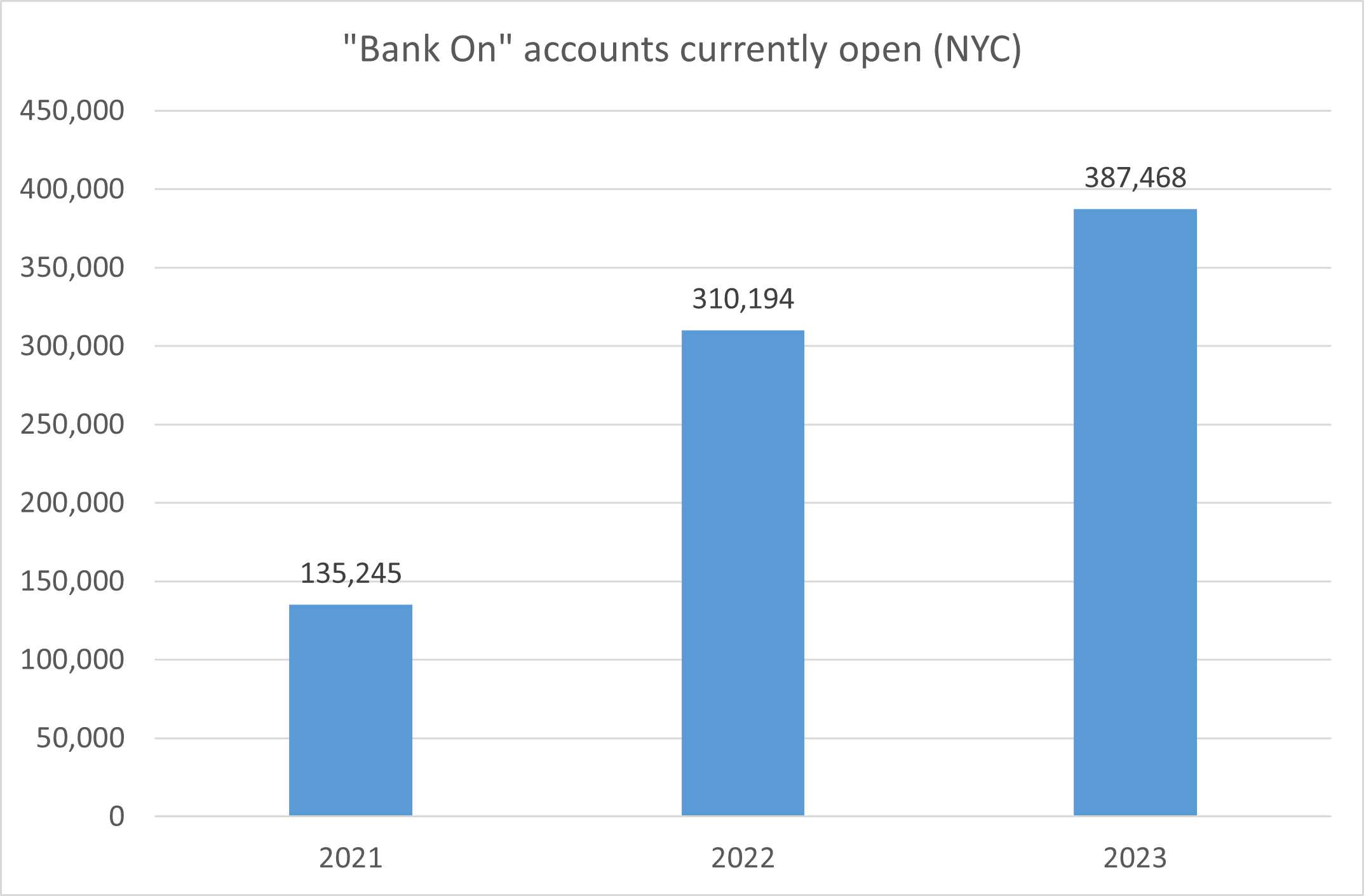

The Bank On initiative provides another significant opportunity to enhance banking affordability. Created by the Cities for Financial Empowerment Fund in 2015, the Bank On certification sets standards for low-cost bank accounts: these accounts must have minimum opening deposits no higher than $25, no overdraft or NSF fees, and free basic banking services. By the end of 2023, over 11 million active Bank On-certified accounts existed nationwide, with availability across 46,350 bank branches covering 89 percent of U.S. zip codes. As shown in Chart 3, the number of open Bank On-certified accounts has increased since 2021.

Chart 3

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; Office of the NYC Comptroller

In New York specifically, “Basic Banking” legislation enacted in 1994 requires state-chartered banks to offer low-fee accounts. Since 2022, DFS has explicitly recognized Bank On accounts as meeting these criteria, helping to expand their availability statewide. As of March 2023, Bank On accounts were offered by 20 state-chartered banking institutions and 34 out-of-state-chartered banks operating in New York.

But despite their broad availability, public awareness of these accounts remains very low. A 2023 CFPB study found that of 36 low- and moderate-income consumers interviewed, none knew about Bank On accounts. Increased public outreach and consumer education are needed to maximize their effectiveness.

Other states and cities offer some insight for increasing consumer awareness. There are 96 Bank On coalitions in cities and metro areas across the country. These coalitions partner with financial institutions, community and advocacy groups, as well as local, state, and federal regulators to run public awareness campaigns, provide financial literacy resources, and negotiate with local banks and credit unions to offer Bank On accounts.

The National League of Cities published a Bank On guide in 2011 to help communities establish Bank On at local banks. While dated, the report provides guidance for Bank On marketing and outreach, along with consumer financial education. Suggested strategies include using market-based research to understand the needs and demographics of the target population, working with marketing professionals to develop awareness strategies, and partnering with participating financial institutions to support program marketing.

The State’s and City’s business relationships with banks—via Banking Development District programs and the New York City Banking Commission—provide leverage to expand bank access

The state and city Banking Development District (BDD) programs offer additional opportunities to enhance banking access in underserved communities. Initiated by DFS in 1998 and extended to include credit unions in 2019, the state BDD program encourages banks and credit unions to establish branches in underserved neighborhoods by providing up to $10 million in subsidized public deposits and other incentives, such as property tax exemptions.

New York City created its own BDD program in 2003, which complements state incentives with an additional $20 million in subsidized deposits per branch. The collaborative “Enriched BDD” initiative launched in 2004 targets especially underserved areas, offering expanded benefits such as enhanced consideration under the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and workforce development support. A 2009 DFS assessment found that while BDD branches successfully reduced the unbanked population in targeted areas, the program’s effectiveness could be substantially improved with enhanced requirements on service provision, community outreach, and financial education.

Taken together, the State and City BDD programs make banking more accessible, and therefore help families avoid the use of high-cost non-bank financial products, now much less regulated at the federal level.

New York City’s Banking Commission consists of three members representing the Mayor, the Commissioner of Finance, and the City Comptroller. The Commission meets annually to review and approve the list of NYC Designated Banks, which are the only banks allowed to hold City deposits. It also administers the City’s Banking Development District program, approving or rejecting the designation of new Banking Development Districts.

Among other requirements, the Rules of the City of New York require applicant banks seeking designation by the Banking Commission to submit written policies on anti-discrimination in lending, as well as a statement of branch openings and closings within the city over the past three years. Banks that fail to submit their anti-discrimination policies are not eligible for designation. Under the rules, banks must demonstrate they are not disproportionately closing bank branches in low-income neighborhoods in order to be eligible for designation.

Like the Banking Development District programs, the NYC Banking Commission’s designation process can be a tool to incentivize banks to address accessibility barriers and to promote minority depository institutions and credit unions, discussed below.

Minority depository institutions and credit unions remain underrepresented in the City and State’s banking relationships

Minority depository institutions (MDIs) and credit unions play an essential role in expanding access to banking for underserved communities. Research on MDIs—defined as banking institutions which are either majority-owned by people of color or have a majority-minority board of directors and predominantly serve communities of color—indicates that these banks are far more likely to operate in low-income neighborhoods than their non-MDI counterparts and often operate the only brick-and-mortar banks in their respective zip codes. Credit unions, in particular Low-Income Designated credit unions, similarly demonstrate a tendency to serve lower-income neighborhoods and areas where traditional banks are less prevalent.

Despite their importance, MDIs and credit unions are underrepresented in New York City’s and State’s banking relationships. As of 2024, only one MDI, Popular Bank, holds a designation with the City’s Banking Commission. And state law altogether prohibits the City’s Banking Commission from opening depository accounts with credit unions. Both the Banking Commission and the City and State Banking Development District programs could do more to direct support toward these institutions.

Identification requirements and ongoing discrimination limit banking access for marginalized New Yorkers

In addition to overdraft fees, minimum balance requirements, and other financial costs associated with traditional banking, several non-monetary factors act as notable barriers to bank accessibility, particularly for marginalized groups.

Identification requirements can present an important obstacle to bank access for New Yorkers. Most banks require a government-issued photo ID to open an account as well as proof of address, and many require a secondary identification such as a Social Security card. These requirements pose challenges for certain populations who may struggle to obtain necessary documentation, including undocumented immigrants, formerly incarcerated individuals, youth, and individuals experiencing homelessness.

To address issues obtaining other forms of government-issued ID, New York City introduced IDNYC, a free municipal ID program accessible to all New York City residents aged 10 and up, regardless of immigration or housing status. Since its launch in 2015, over 2 million New Yorkers have enrolled in IDNYC. While some banks in New York City accept IDNYC as a valid form of identification, most do not, and there is currently no legal requirement mandating its acceptance. Thus, IDNYC’s potential to expand bank access among vulnerable populations remains limited.

Discrimination also remains an important obstacle to bank access. A 2023 report from the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) finds that Muslim and Black Americans report challenges with account denials, closures, or investigations at rates over twice as high as other demographic groups. These patterns suggest the need for systemic reforms to improve transparency and accountability in account screening and approvals.

Several pieces of legislation have been introduced in Albany in recent years to address these barriers. The Pro-Banking Act (A6662/S163, sponsored by Senator Jessica Ramos and Assembly Member Grace Lee), introduced in multiple legislative sessions, would require all State-chartered banks to accept IDNYC as valid identification for opening an account. The Banking Bill of Rights (A7794/S7583, sponsored by Senator John Liu and Assembly Member Zohran Mamdani), introduced in 2023 in response to the findings from ISPU’s report, would require financial institutions to provide written reasons for account closure or denial of debit/credit card applications and offer applicants an opportunity to contest the decision. As of the time of this writing, neither bill has passed.

Non-Bank Financial Products

Earned Wage Access (EWA) and other high-cost lending products exploit regulatory loopholes to avoid oversight, but models exist to improve the viability of these products

Earned Wage Access (EWA) services have rapidly emerged as an option allowing employees to receive part of their earned wages before payday. These services generally take two forms. In the employer-partner or “direct-to-business” model, providers such as Branch, DailyPay, Wagestream, Payactive, and Even partner with employers to offer early access to wages. In some cases, the employer directly funds the advance, but models also exist in which the provider funds the advance and later recoups it from the employer after payroll deductions. These employer-partnered models are typically associated with lower fees, with some employers even providing the benefit at no cost to workers.

On the other hand, the direct-to-consumer model—offered by providers such as Dave, Earnin, and Brigit—operates independent of employers. That is, the EWA provider directly finances an advance, then after payday deducts the value of the advance plus any fees from the employee’s bank account. It is essentially a short-term loan collateralized by access to the worker’s bank account, much like a payday loan.

The EWA market, though relatively small, has grown rapidly since 2019. A survey from the Financial Health Network found that in 2023, 7 percent of employed households had access to employer-partnered EWA, up from 5 percent a year earlier. The CFPB reported that in 2022, 7 million workers accessed $22 billion in employer-partnered EWA advances, while 3 million workers accessed around $9 billion through direct-to-consumer providers. Data from earned wage access companies indicate that a substantial majority of EWA users earn less than $50,000 per year, a figure which is even lower for direct-to-consumer users, underscoring that these products largely target low-income workers.

Though often marketed as “no fee,” EWA products conceal user costs behind a range of misleading practices. Hidden costs can include expedition fees, processing and per-transaction fees, monthly subscription fees, and even manipulative “tipping” schemes. California’s Department of Financial Protection and Innovation (DFPI) found that among EWA providers that include a tipping “option,” 73 percent of users paid tips—likely a result of these apps including a certain percentage tip as the default payment option, and some even appearing to limit future credit for users who don’t tip. Other manipulative practices around tipping include inadequately disclosing that tips are optional, and claiming that tips help more vulnerable consumers avoid fees.

After accounting for all costs—expedition fees, processing fees, monthly subscription fees, tips, and other costs—California’s DFPI found that EWA products charge an average effective APR of 330 percent or above, the same astronomical interest rates that many payday lenders charge, which are illegal under New York State usury law. Furthermore, a CFPB study found that workers with access to EWA took out an average of 27 transactions per year, contradicting the idea that EWA helps users get through one-off liquidity emergencies.

Proponents of EWA argue that the product presents clear advantages over payday lending. They cite that the absence of brick-and-mortar storefronts allows for lower transaction costs, and that their apps are more efficient at recouping funds. Preliminary research suggests offering EWA as a company benefit may enhance employee retention and recruitment. For workers, proponents argue that EWA presents a significant advantage over payday loans in that EWA providers do not report to credit bureaus, do not involve debt collection agencies, and do not conduct automatic debt rollovers.

But in many ways, the rapid rise of EWA mirrors the rise of payday lending during the 1990s and early 2000s. Both target low-income individuals with products presented as short-term bridges to one’s payday in case of unusual liquidity constraints, even though usage statistics strongly contradict this notion. Like payday lending, hidden fees and unclear terms can leave consumers with high unexpected costs at best and spiraling debt at worst.

The rapid growth of EWA and its popularity among some workers suggests there is genuine demand for products offering short-term liquidity. Still, the exorbitant interest rates, the frequency of use, and the hidden fee structures reveal substantial consumer risks, especially among the low-income worker base that these apps target.

In addition to EWA, several high cost, “traditional” (non-fintech) products have similarly circumvented state lending regulations and usury laws. Rent-to-own contracts allow customers to rent large items such as furniture or appliances, with an option to purchase the item at the end of the term (distinct from a layaway plan). While somewhat regulated in New York, consumers may end up paying up to 325 percent of the sticker price for a particular item. Other schemes, like litigation funding and merchant cash advance, lend to people and small businesses at predatory, triple-digit interest rates.

Under former director Rohit Chopra, the CFPB attempted to bring EWA under the regulatory umbrella of the Truth in Lending Act (TILA). In 2024, the Bureau issued an interpretive rule classifying Earned Wage Access or “paycheck advance” products as consumer loans subject to TILA requirements. But given the Trump administration’s work to rescind major CFPB rules, and its significant rollback of Bureau enforcement efforts, the future status of the Bureau’s EWA guidance remains questionable at best.

Despite federal retrenchment, New York State has begun addressing these regulatory gaps. In April 2025 Attorney General Letitia James sued two EWA providers, DailyPay and MoneyLion, asserting that they operate as illegal payday lenders.

Meanwhile, the New Economy Project, a New York City-based consumer advocacy group, has led a coalition to advance the End Loansharking Act (A4918/S1726, sponsored by Senator Samra Brouk and Assembly Member Steven Raga). The bill expands the definition of “financing arrangement” in New York’s usury law to clarify that the state’s 25% interest rate cap covers Earned Wage Access and other ultra-high-cost lending products like rent-to-own, litigation funding, and merchant cash advances. It would also mandate the transparent disclosure of APR inclusive of all fees and tips and empower the Attorney General’s Office with expanded regulatory authority.

It should be noted that while other states have approached EWA regulation, not all share the same goals in doing so. Some states such as Utah, Nevada, Missouri, Alaska, and Georgia have enacted industry-backed legislation to “license” EWA providers while explicitly exempting them from traditional lending laws, effectively legitimizing their business models, deceptive fees and all. In contrast, California and Maryland have categorized at least some types of EWA as loans subject to more stringent regulation. Other states, like Connecticut, effectively blocked EWA in their state, which led to outcry from the fintech industry and a new bill intended to repeal the law. Attorneys General in jurisdictions including Washington, D.C. and New York have also pursued legal actions against prominent EWA providers. In total, according to National Conference of State Legislators, at least 20 states have pending legislation on earned wage access in 2025, while other states have already passed EWA laws.

Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) products have exposed users to hidden costs and data risks, but recent state legislation has introduced important protections

Like EWA, Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) is an innovation purportedly aimed at solving for a household’s inability to cover immediate expenses. BNPL, which presents a somewhat lower-cost alternative credit option, allows customers to split retail and other purchases into ostensibly interest-free installments—typically four installments paid over six weeks. However, BNPL still comes with risks and costs, which may be unknown to consumers.

Nearly all BNPL users have bank accounts and credit scores, but BNPL use is higher among those with lower credit scorers, lower income, and recent reports of failed credit applications or delinquent payments—suggesting a subprime to near-prime target consumer market. In 2023, approximately 17 percent of U.S. households used a BNPL service, up from just 7 percent in 2021. Major providers include Klarna, Affirm, PayPal, and Sezzle.

In 2022, Chuck Bell at Consumer Reports identified six major gaps in consumer protection associated with BNPL products: (1) a lack of transparency around fees, interest rates, and payment terms; (2) problems with customer service and the right to dispute; (3) the potential for consumers to unwittingly become overextended on credit; (4) costly late fees and overdraft penalties; (5) inconsistent policies around credit bureau reporting; and (6) data privacy and data security issues.

Still, consumer rights advocates recognize that BNPL can have legitimate use cases in extending credit access for big purchases. “In some ways, it’s like a credit card on training wheels,” said an advocate at Consumer Reports, “if they charge interest close to credit card rates.”

Similar to Earned Wage Access products, in 2024 the CFPB issued guidance classifying BNPL lenders as equivalent to credit card providers, and therefore subject to the same Regulation Z protections, which implement the Truth in Lending Act. However, in May 2025, the Trump administration’s CFPB announced that it will longer prioritize enforcement against BNPL providers and hinted it might rescind earlier BNPL guidance.

On May 9, 2025, Governor Hochul signed Article VII of the FY2026 Executive Budget, which includes regulations for BNPL providers. Its definition of BNPL excludes direct financing from a retailer to a consumer (i.e. no third-party lender is involved). The law sets requirements for providers to obtain licenses with the state; transparent loan-term disclosures; standards prohibiting unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts or practices; and consumer data protections. It also empowers DFS to enforce these measures through rulemaking and enhanced oversight.

The new BNPL regulations address many of the concerns cited by Chuck Bell: they set a cap on fees and interest rates and require clear disclosure of payment terms, require fair and transparent refunds and dispute resolution upon consumer request, require lenders to make a reasonable determination that a consumer will be able to repay the loan prior to issuing it, and require consumer consent for data collection before it occurs. The largest unaddressed concern is credit reporting, on which the law is silent, neither requiring nor prohibiting it. This leaves room for a potential future ruling that providers report data to credit bureaus.

Consumer Rights

New York lacks strong data privacy laws to control how financial institutions use consumers’ personal data

The collection and sale of consumers’ personal data by companies was largely ignored in 20th century consumer protection laws because it was not a widespread practice. Technological advancements have enabled companies to collect, use, and distribute a wide range of personal data about consumers. Without data privacy laws, data can be collected without the consumer’s awareness or consent, and the consumer has no control over how the information is used or distributed. This is a newer area of consumer protection, and one where New York’s laws are relatively weak.

In October 2024, the CFPB finalized a rule on data privacy (which it has announced plans to vacate as of May 27, 2025) that granted consumers the rights to access their personal financial data, have it transferred to another provider at their request, revoke access to their data, or have it deleted. While several states have added data privacy rights to their consumer protection laws, a November 2024 CFPB report found that financial service providers were exempt from some or all of the privacy requirements to which other companies were subject. Many state data privacy laws enacted new consumer rights not already in federal law, including the right to ask if a business has collected their data and view the data in some cases, the right to have their data deleted, and the right to have the data transferred to another business.

Enacted in 1999, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) requires financial institutions to take measures protecting against data breaches and prohibits the sharing of personal information without informing the consumer and allowing them to opt out. Because financial institutions are already subject to the GLBA, states generally exempt them from their data privacy laws. However, the GLBA is typically weaker than states’ new data privacy laws. For example, the GLBA does not provide consumers the right to correct information; only allows consumers to opt out rather than opt in to data sharing; provides exceptions that allow financial institutions to share data with third parties without an option for the consumer to opt out, in certain cases; and does not contain a broad mechanism for opting out, thus requiring consumers to inform each financial institution separately.

The CFPB recommends that states minimize data privacy exemptions when possible and consider gaps in federal law when crafting state policies. A state law is not considered inconsistent with the GLBA if the consumer protection provided is “greater than the protection provided” by the GLBA. Therefore, state laws that offer protections beyond the GLBA are generally able to avoid preemption.

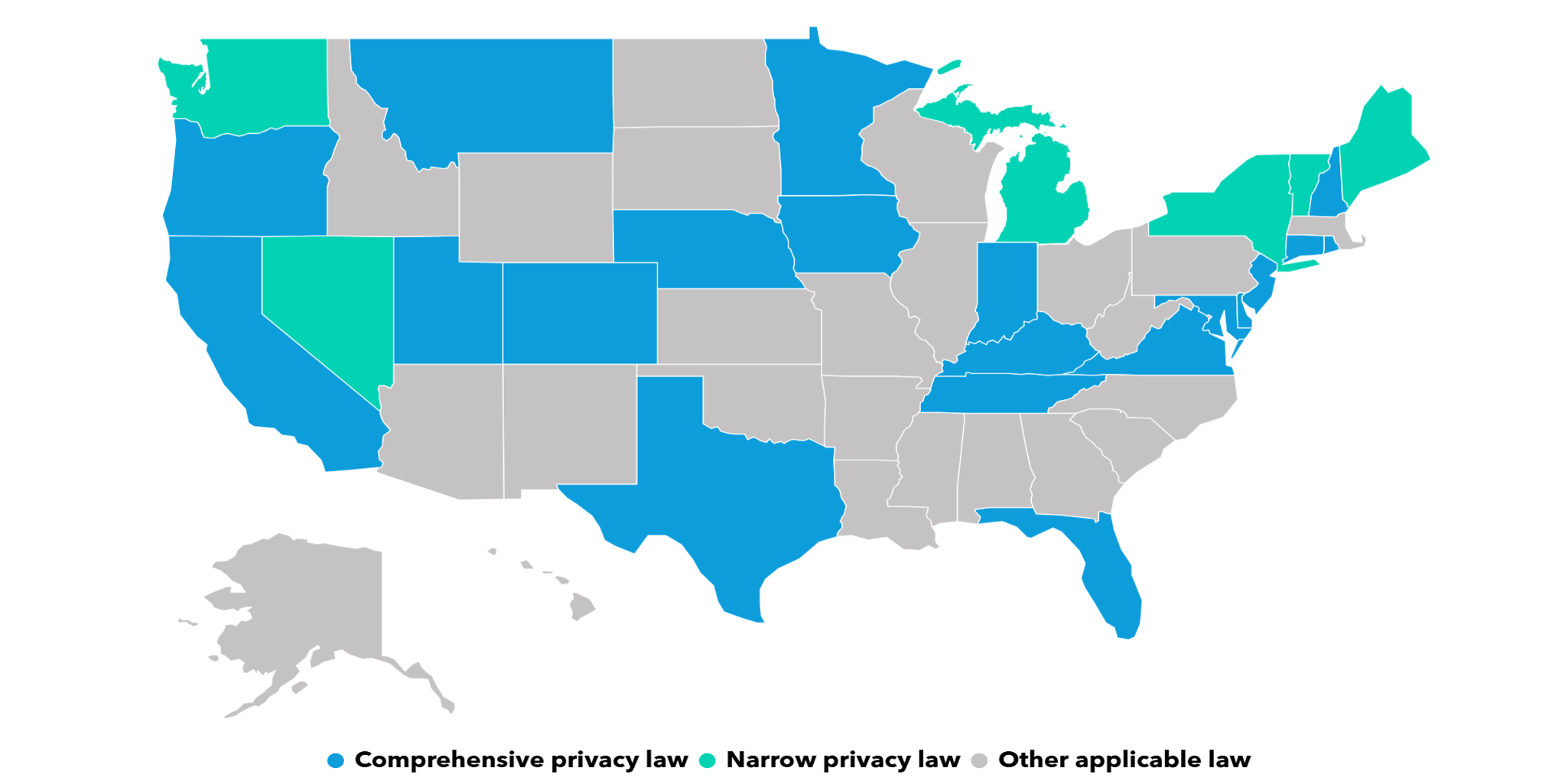

New York’s privacy laws are not particularly robust compared to other states. As shown in Chart 4, copied from a 2025 Bloomberg Law report, New York is one of a few states whose data privacy laws do not address more recently salient issues such as the rights for consumers to correct their data or have it deleted.

Chart 4. States with consumer data privacy laws (Bloomberg Law)

Source: Bloomberg Law 2025

Oregon and California are two of the twenty states boasting more comprehensive legal regimes. Oregon’s Consumer Privacy Act, passed in July 2024, includes disclosure requirements for companies processing data, allows consumers to correct or delete data, and endows the state attorney general with enforcement capability. The state has also implemented a public awareness campaign and a complaint database for consumers to flag violations.

California’s 2018 Consumer Privacy Act was amended in 2023 to include similar provisions. It was the first state to enact a comprehensive data privacy law, which gave consumers the right to know how their data is collected and used, have their collected data deleted, opt out of having their data sold or shared, correct inaccurate data, limit the use and disclosure of sensitive personal information, and be protected from discrimination for exercising these rights.

New York’s last update to its privacy laws was the 2019 SHIELD Act, which amends the 2005 Information Security Breach and Notification Act. It expanded the earlier definition of private information to include biometric and password information and requires anyone who discovered a breach to notify impacted customers and the state attorney general. However, it does not contain disclosure standards or require companies to obtain consent before collecting and processing consumer data. In 2023, the State Senate passed the New York Privacy Act, which would have enacted these provisions and empowered the attorney general to conduct oversight on companies that collect or sell data, but the bill was not passed into law.

New York State has some of the strongest debt collection and credit reporting protections in the country

New York State and New York City have among the strongest debt collection and credit reporting protections in the country. In January 2025, the City’s Department of Consumer and Worker Protection (DCWP) published new rules for debt collectors, which will take effect in October. The provisions include expanded reporting requirements to show actions taken in other languages, and communication requirements with consumers (e.g. limits on communication frequency and more strict disclosure standards).

In 2022, New York State passed the Consumer Credit Fairness Act, which strengthened consumer protections around debt collection. The act lowered the statute of limitations to file a debt collection action and added more requirements for collectors attempting to enforce a debt.

In 2023, New York became the first state to prohibit medical debt from appearing on credit reports. The CFPB finalized a similar rule in January 2025 and is now seeking to vacate it, but New Yorkers are protected from this potential reversal because of the existing state law.

Consumer Outreach and Engagement

Even with limited regulatory power compared to the federal government, the State and City can play a pivotal role in expanding access to safe financial services through public education and direct support

New York State’s power over financial providers is limited: it can only regulate state-chartered banks, but has no authority over federally chartered banks or banks chartered out of state. It also has no authority over products like credit cards, whose issuers are subject to the laws of the state they are based in. New York City has even less power in this regard, as much financial regulation is preempted by the state.

In spite of these limitations, New York State and City are well-positioned to reach consumers directly. “From a soft power perspective, cities have a lot of power to help consumers through outreach to community groups, stakeholders, and the public, and by helping consumers exercise their rights,” said one former CFPB staffer. A consumer advocate from Consumer Reports agreed: “The City’s level of contact with residents is a major asset. They can do a lot to help people find the financial path that’s most affordable to them.”

New Yorkers are often unaware of the resources available to them through the state and local government. Although many banks in New York offer Bank On-certified accounts or other free and low-cost basic banking options, awareness among consumers is low, as discussed previously. A 2023 CFPB spotlight on consumer experiences with overdraft programs found that none of the 36 low- and moderate-income consumers interviewed were familiar with Bank On accounts, which do not have overdraft fees, among other affordability standards. Multiple consumer advocates mentioned that despite their benefits, Bank On accounts have low uptake rates, in large part because of low awareness. A well-targeted public awareness campaign by the state or city could likely expand the use of affordable banking options like Bank On accounts.

In addition to broad public awareness campaigns, the City has strong existing infrastructure for individualized financial counseling. DCWP operates Financial Empowerment Centers in all five boroughs, offering free one-on-one financial counseling on topics including opening and maintaining bank accounts, addressing concerns with debt, and establishing or improving credit. These Centers provide further opportunities to improve awareness and uptake of affordable banking options. They are also well positioned to reach vulnerable groups, particularly immigrants who may be unaware that they can safely utilize these resources. Public awareness campaigns should make clear that affordable banking and financial counseling are available to all New Yorkers, regardless of their situation.

The CFPB’s complaint portal has proven essential to consumer protection—and could inform similar efforts in New York

The CFPB has accepted consumer complaints since 2011, primarily via an online form. A consumer can submit a complaint about an issue caused by a specific company across a number of financial products. The complaint data is publicly available in a searchable database, allowing anyone to access complaints by company, date submitted, product type, or issue. As part of the this report, the Comptroller’s Office conducted an original analysis of the public complaint database; key findings from that analysis are summarized below.

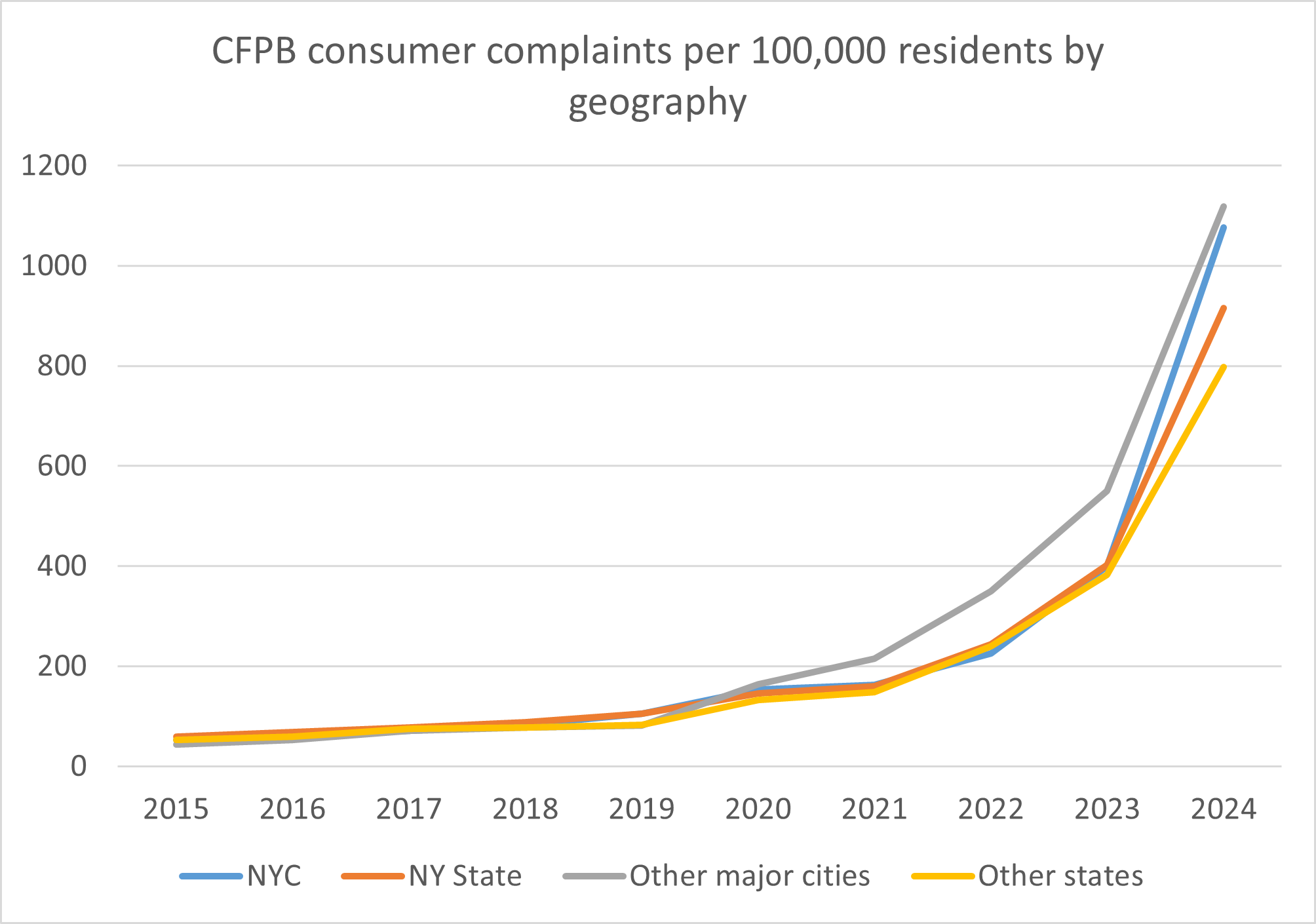

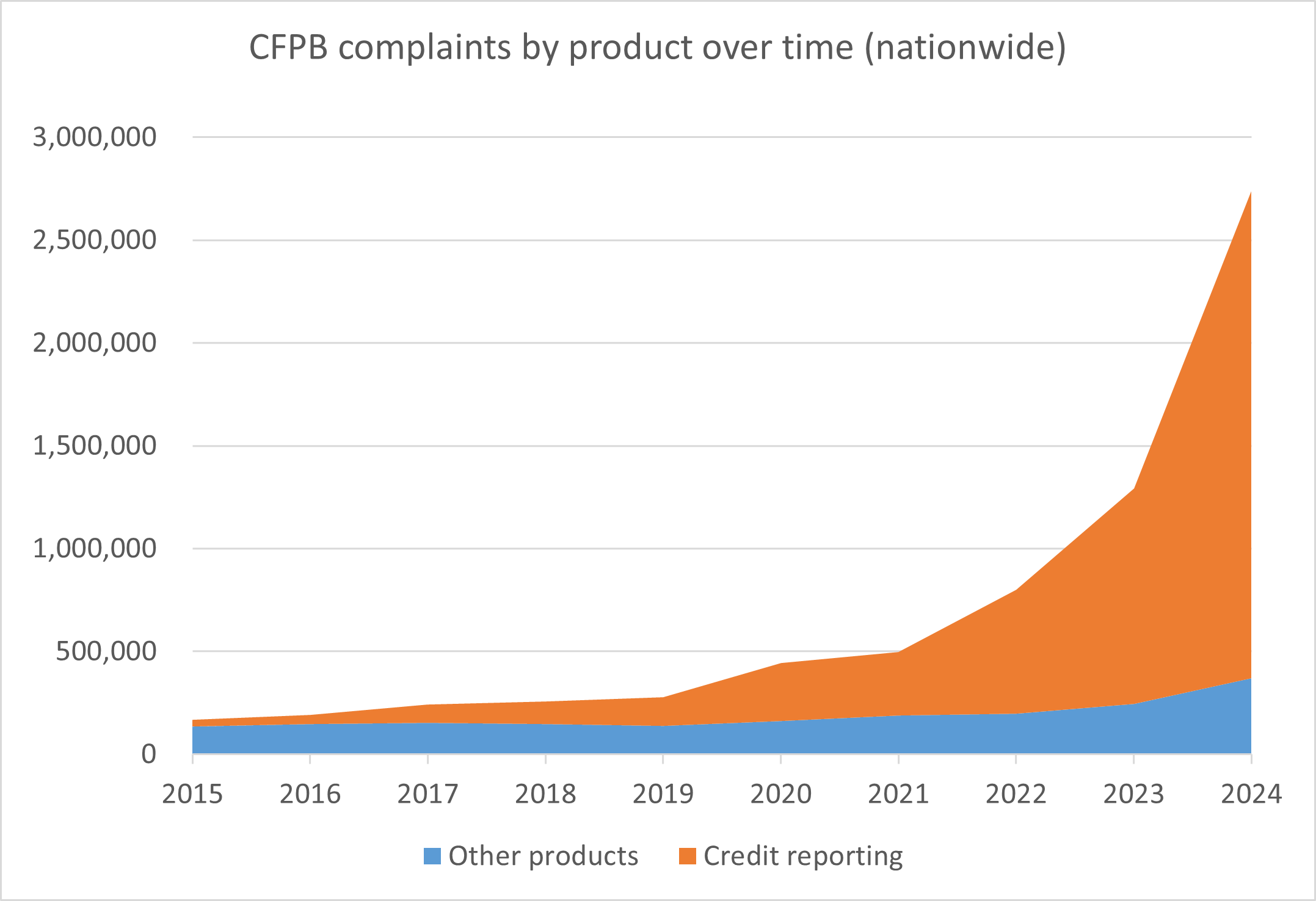

Both within New York and nationwide, the number of complaints filed has gone up every year, and has skyrocketed since 2022, as shown in Chart 5. New Yorkers submitted over 30,000 complaints in 2022, 51,000 in 2023, and 125,000 in 2024—jumping more than 300 percent in only two years. This year, over 40,000 complaints were logged in the first quarter alone, putting 2025 on track to have the highest number of complaints in the database’s history.

Chart 5

Source: CFPB Consumer Complaint Database; Office of the NYC Comptroller

As shown in Chart 6, credit bureau complaints have accounted for a greater share of total complaints every year, and they now represent the vast majority. A former CFPB employee cited several potential reasons for both this shift in composition and the greater quantity of complaints across all areas. These include growing consumer awareness of the CFPB, changes to the complaint form which allows complaints to be submitted against multiple companies for a credit reporting issue, an increase in usage of credit repair companies that often file complaints on behalf of consumers, and occasional viral posts and social media influencers who provide guidance or templates for submitting complaints with the goal of improving credit scores.

Chart 6

Source: CFPB Consumer Complaint Database; Office of the NYC Comptroller

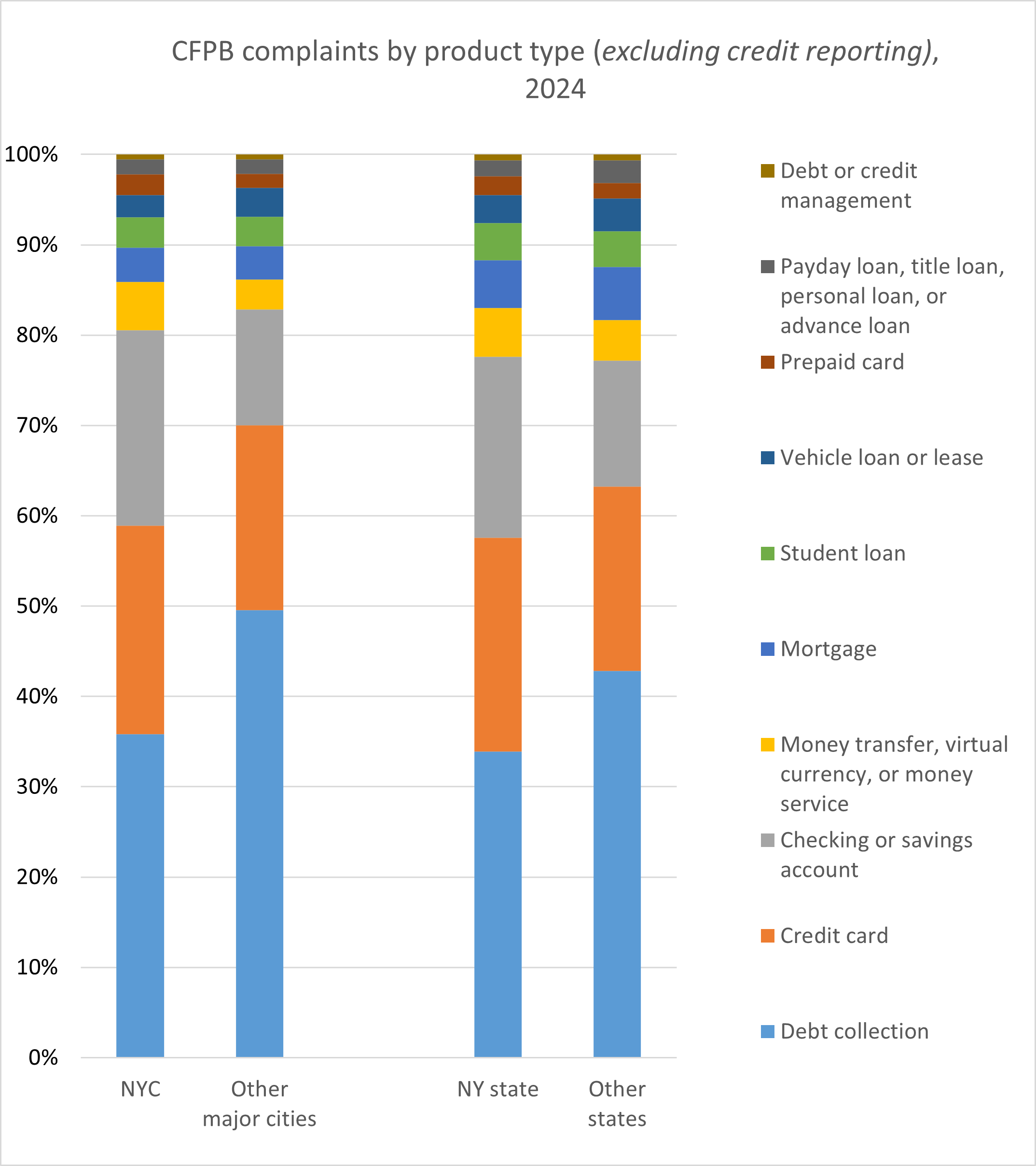

Consumers continued to submit complaints about a variety of other products. As shown in Chart 7, most of these complaints related to issues with debt collection, credit cards, and bank accounts. New York City and State have lower shares of complaints about debt collection than other cities and states, likely due to strong state protections. Most debt collection complaints in 2024 either related to collection attempts on debts the consumer did not owe, or problems with misleading, unclear, or missing written notifications. Credit or prepaid card complaints cover more diverse issues such as problems with incorrect information on statements, company investigations, and getting a new credit card. Most complaints about bank accounts involved managing or closing an account.

Chart 7

Source: CFPB Consumer Complaint Database; Office of the NYC Comptroller

After a complaint is submitted, the CFPB sends it directly to the company, which then has 60 days to provide a final response to both the CFPB and the consumer. Nearly all (99 percent) of the complaints in the database were closed within 60 days. Multiple advocates and regulators noted that companies tend to be more responsive to complaints sent via the CFPB than those coming directly from consumers. “We’ve seen real success with the Bureau’s complaint database,” said one consumer advocate. “Companies actually respond to consumer complaints, where they might not otherwise. And it’s a great way for policymakers to look at trends in the market.”

Complaints can result in several outcomes for the consumer. Broadly, a consumer can either receive relief or not. Relief can be non-monetary (e.g. incorrect information corrected on a credit report) or monetary (e.g. a refund from a scam). As more complaints have been received over time, the proportion of complaints resulting in relief has also gone up: before 2022, consumers received relief for just 20 percent of all complaints. In 2022, that rate jumped to 35 percent, and in 2024, 50 percent of complaints resulted in relief to the consumer. A former bureau employee attributed this increase to pressure put on credit bureaus by the CFPB: in the early 2020s, credit reporting agencies tended to close complaints quickly without considering the merits of individual complaints, but the CFPB’s advocacy and criticism of this practice caused them to improve their responses, resulting in more relief for consumers.

Complaint submissions vary by geography and tend to be more common in lower-income neighborhoods. Within New York City, the Bronx had the most complaints by population in 2024 (2,151 complaints per 100,000 people), while Manhattan and Staten Island submitted the fewest complaints, at around 900 per 100,000 people. The rate of complaints receiving relief was consistent across boroughs and reflects the national trend.

The inverse correlation between median household income and complaints per capita also roughly holds across U.S. cities, as shown in Chart 8 below. A former bureau employee theorized that credit repair organizations target low-income communities more than wealthier areas, and this is reflected in complaint density. They also noted that some areas, like Florida, have especially active credit repair markets even after accounting for income.

Chart 8

Source: CFPB Consumer Complaint Database; American Community Survey; Office of the NYC Comptroller

In our conversations with consumer advocates and former CFPB staff, the consumer complaint database was brought up repeatedly as one of the Bureau’s greatest strengths. The database is still online, but it is unclear to what extent complaints are being addressed, if at all, by the current CFPB. The database has been an important source of relief for consumers and accountability for companies, and it would be a helpful resource to implement at a state or city level, both to support consumers who are harmed and to incentivize companies to improve their treatment of consumers.

The DCWP, DFS, and New York State Attorney General’s office each have online portals for consumers to submit complaints, but none offer a searchable public database of past complaints. This feature of the CFPB’s complaint system allows consumers to see if their issue is recurring, identify frequent violators, and learn what type of relief they can expect for a particular problem. It also encourages companies to resolve complaints efficiently and improve sources of consumer issues.

Recommendations

Recent actions taken by the Trump Administration and Congress to weaken or altogether eliminate federal consumer protections have accelerated the need to address the shortcomings in and bolster New York’s own legal, regulatory, and administrative framework. The following recommendations, which map on to the five key issue areas covered in this report—regulatory and enforcement gaps, banking access and affordability, non-bank financial products, consumer rights, and consumer outreach and education—would help guard against further encroachment by the federal government and set New York on a path toward claiming among the strongest consumer protections in the country.

Strengthen Enforcement Powers and Resources

- Pass the FAIR Business Practices Act (A8427, sponsored by Assembly Member Micah Lasher), as proposed by the Attorney General’s Office.

Regulators and consumer advocates consistently identify New York’s weak consumer protection statute (GBL § 349) as one of the state’s most significant barriers to realizing a safe and accessible consumer financial marketplace. The FAIR Business Practices Act addresses the biggest weaknesses of GBL § 349. As one former CFPB employee noted, “It could make New York a national regulatory leader on UDAP, the way California is with emissions standards.” The Act adds prohibitions against “unfair” and “abusive” corporate practices, explicitly extends consumer protections to small businesses and non-profits, increases penalties for violating the law, and wipes away decades of pro-corporate case law that has greatly narrowed the scope of consumer harms that can be litigated.

- Fully fund the Office of the Attorney General, DFS, and DCWP so they have the staff and technical capability to investigate and act against harmful practices.

This is especially important while the federal government neglects its regulatory responsibilities. In the coming years, consumers will likely have to increasingly rely on state and city regulators for protection and relief. For regulators like DFS and DCWP and for the state attorney general, “it’s not just about formal power,” noted a consumer advocate at Mobilization for Justice. “It’s about manpower. These agencies need funding to protect consumers.”

- Set up a statewide “Consumer Protection Restitution Fund”— similar to the CFPB’s Civil Penalty Fund—which would collect a portion of civil consumer penalties in order to compensate consumers who cannot receive restitution from the defendant.

At times, consumers harmed by deceptive business practices are unable to obtain the restitution they are owed because the defendant (i.e. the business or person that harmed the consumer) has become insolvent or otherwise incapable of paying. To address this, the state should create a dedicated Consumer Protection Restitution Fund, modeled after the CFPB’s Civil Penalty Fund.

The fund would be financed by collecting a portion of the civil penalties imposed upon businesses found in violation of consumer protection law, along with unclaimed consumer restitution payments. The fund would then be used to compensate individual victims in cases where restitution from the defendant is not feasible. In addition to the CFPB, similar funds have been adopted by California and Minnesota. Establishing a Consumer Protection Restitution Fund in New York would broaden the state’s ability to provide restitution to all victims of harmful business practices.

Advance Affordable Banking Options

- Enact DFS’ proposed rule limiting overdraft fees at state-chartered banks.

Before its repeal under Trump and the Republican Congress, the CFPB’s 2024 rule limiting overdraft fees at very large financial institutions saved consumers over $6 billion in one year. Now, the state has the opportunity to preserve and build on at least some of the protections the CFPB’s rule previously offered New Yorkers. While the Department of Financial Services cannot regulate nationally chartered banks or those chartered out-of-state, it can limit excessive fees at the 78 state-chartered banks, thrifts, and credit unions operating in New York, accounting for almost 2,000 branches and over $660 billion in total customer deposits.

DFS’ proposed rule on overdrafts would make banking considerably more affordable for millions of New Yorkers. The rule would prohibit overdraft fees on overdrafts of less than $20; fees that exceed the overdrawn amount; over three overdraft or non-sufficient funds fees per consumer account per day; “Authorize Positive Settle Negative” fees, which occur when the consumer had enough funds for the purchase at the time of transaction, but not at the time of settlement; and fees on transactions that were immediately declined; among other protections.

- Enact legislation to improve bank accessibility, including measures to require the acceptance of IDNYC as valid identification, mitigate against discrimination, and provide targeted support for minority depository institutions and credit unions operating in underserved communities.

To address non-monetary barriers to bank accessibility, the State should enact the Pro-Banking Act (A6662/S163, sponsored by Senator Jessica Ramos and Assembly Member Grace Lee) and the Banking Bill of Rights (A7794/S7583, sponsored by Senator John Liu and Assembly Member Zohran Mamdani). The Pro-Banking Act would require state-chartered banks to accept IDNYC as valid identification to open a bank account, enabling access among groups that often have difficulties obtaining another form of government-issued photo ID, including undocumented immigrants, youth, and people experiencing homelessness. The Banking Bill of Rights, introduced in response to documented discrimination against Muslim and Black New Yorkers, would mandate banks provide clear explanations for account closures and denials, and provide consumers the opportunity to contest these decisions.

Additionally, state legislation could empower New York City to promote the presence of minority depository institutions and credit unions within underbanked communities. First, the State should amend existing law to authorize the City to open depository accounts with credit unions, something the City Banking Commission is currently unable to approve. Second, state legislation could establish an M/WBE-style program tailored specifically to MDIs, facilitating increased access to city contracting opportunities and incentivizing greater MDI presence across the city.

- Leverage the City’s and State’s business relationships with banks—via the NYC Banking Commission and state agencies including DFS and the Office of the State Comptroller—to promote bank accessibility and affordability.

The State and City conduct business with banks in multiple ways, presenting potential levers for creating broader access to affordable banking. As discussed in this report, the New York City Banking Commission meets annually to vote on whether to continue doing business with banks that holds City deposits,[4] and also approves or rejects the designation of new Banking Development Districts. While the State does not have an exact equivalent to the NYC Banking Commission, it can similarly use its business relationships with banks, as well as BDD designation, to influence bank behavior—including at nationally-chartered and out-of-state-chartered banks, which are otherwise outside of the state’s regulatory purview.

The State and City should prioritize doing business with banks that demonstrate a commitment to affordability. That includes voluntarily reducing or eliminating excessive overdraft, NSF, and credit card late fees, as well as offering low-cost checking accounts, such as “Bank On,” and adequately advertising them to customers.

The City and State should also use their business relationships with banks to address non-monetary barriers to bank accessibility. For example, the City Banking Commission should require that designated banks accept IDNYC as a valid form of identification to open an account. Additionally, any bank found liable for discrimination should be made ineligible for Banking Commission designation.

- Promote awareness of minimal cost “Bank On” accounts in underserved communities.

As of 2023, 54 banking institutions offered Bank On accounts in New York, 34 of which were chartered federally or out-of-state. The State Department of Financial Services encourages banks operating in New York State to offer Bank On accounts, the national standard for minimal-cost checking and savings accounts, but also notes that the existing Bank On accounts have seen “inadequate uptake” and that “many consumers remain unaware that these types of accounts exist.”

To increase utilization of these more consumer-friendly accounts, the State and City should enhance consumer marketing, public outreach, and financial education. Strategies described in the National League of Cities’ Bank On toolkit offer a good starting point. The State should also require that banks adequately train consumer-facing staff on the availability of these types of products.

- Expand funding for the City and State Banking Development District (BDD) programs and incentivize extra service provision at BDD branches, with a particular focus on minority depository institutions and credit unions.

Established in 1997, the New York State BDD program has brought at least 58 active bank branches to underserved communities across the state (including NYC), while the City BDD program has brought at least another 24. Both the State and City should expand funding for their BDD programs to encourage further bank openings in places that need them.

In addition, New York City should expand the “Enriched BDD” program to all BDD districts. That is, the City should offer extra incentives for BDD banks which provide enhanced programs and amenities that meet the unique needs of their community, such as financial education workshops, affordable products (like Bank On accounts), extended hours of operation, multilingual staff, workforce development programs, and special products and services tailored to the community.

Finally, given the tendency for minority depository institutions and credit unions to serve low-income neighborhoods and communities of color more frequently than traditional banks, the State and City BDD programs should provide extra consideration to promoting these forms of banking institutions.

Regulate High-Cost Non-Bank Financial Products

- Pass the End Loansharking Act (A4918/S1726, sponsored by Senator Samra Brouk and Assembly Member Steven Raga), as promoted by the New Economy Project and its coalition.

New consumer fintech products like Earned Wage Access (EWA), along with legacy alternative financial services like rent-to-own contracts, litigation advances, and merchant cash advances, act as very-high-cost lenders but evade state lending law and usury caps due to legal loopholes. These products impose effective APRs that can exceed 300% and often obscure true borrowing costs through hidden fees, vague repayment terms, and manipulative “tipping” schemes. The End Loansharking Act would bring these products under the purview of state lending and usury laws where they belong.

- Reject legislative efforts to merely “license” ultra-high-cost lending products without protecting against harmful business practices.

Industry-backed legislation like Assembly Bill A258A—which would establish licensing for “income access services” like EWA—serve only to legitimize providers’ predatory and deceptive lending practices, and exempt them from rate caps and Truth in Lending Act requirements. A consumer advocate noted that these bills can act as Trojan horses. “It gets a foot in the door for future exploitation by app-based lending products,” he said.

- For all newly emergent consumer lending products, require clear disclosure of fee structures, APR equivalents, and consumer rights; ban solicitation of “tips”; and limit subscription fees.