Executive Summary

Afterschool programs are essential to improving student outcomes and supporting working families—especially as New York City faces a growing affordability crisis. The City spends more than $450 million annually on the largest municipal afterschool program in the nation, but still too many schools are unable to provide enough free, high-quality afterschool seats, leaving working families without the care and enrichment their children need to thrive.[1] This challenge is even more acute for the 22% of public-school students with disabilities, whose families are often left with no afterschool options or with the additional burden of finding—and paying for—afterschool programs that can meet their children’s needs.[2]

Mayor Adams’s recent announcement of a new $331 million investment to expand afterschool programming is a welcome step toward a more universal model.[3] But as with past “universal” education initiatives—like Pre-K and 3-K —the Mayor’s vision of universal afterschool continues to leave students with disabilities behind, treating their inclusion as an afterthought rather than a core commitment.

To better understand the City’s existing afterschool ecosystem and the needs of individual school communities in expanding high-quality programming, the Comptroller’s Office conducted a survey of nearly 2,000 New York City public and charter school principals on their afterschool programs, with a focus on understanding the needs of students with disabilities including those with Individual Education Plans (IEPs) that attend community district schools and those with highly specialized needs at District 75 schools.[i] More than 600 school leaders participated in the survey, the complete results of which are presented in the Appendix. According to the survey:

- 74% of District 75 schools that completed the survey have afterschool programs compared to 93% of schools outside of District 75.

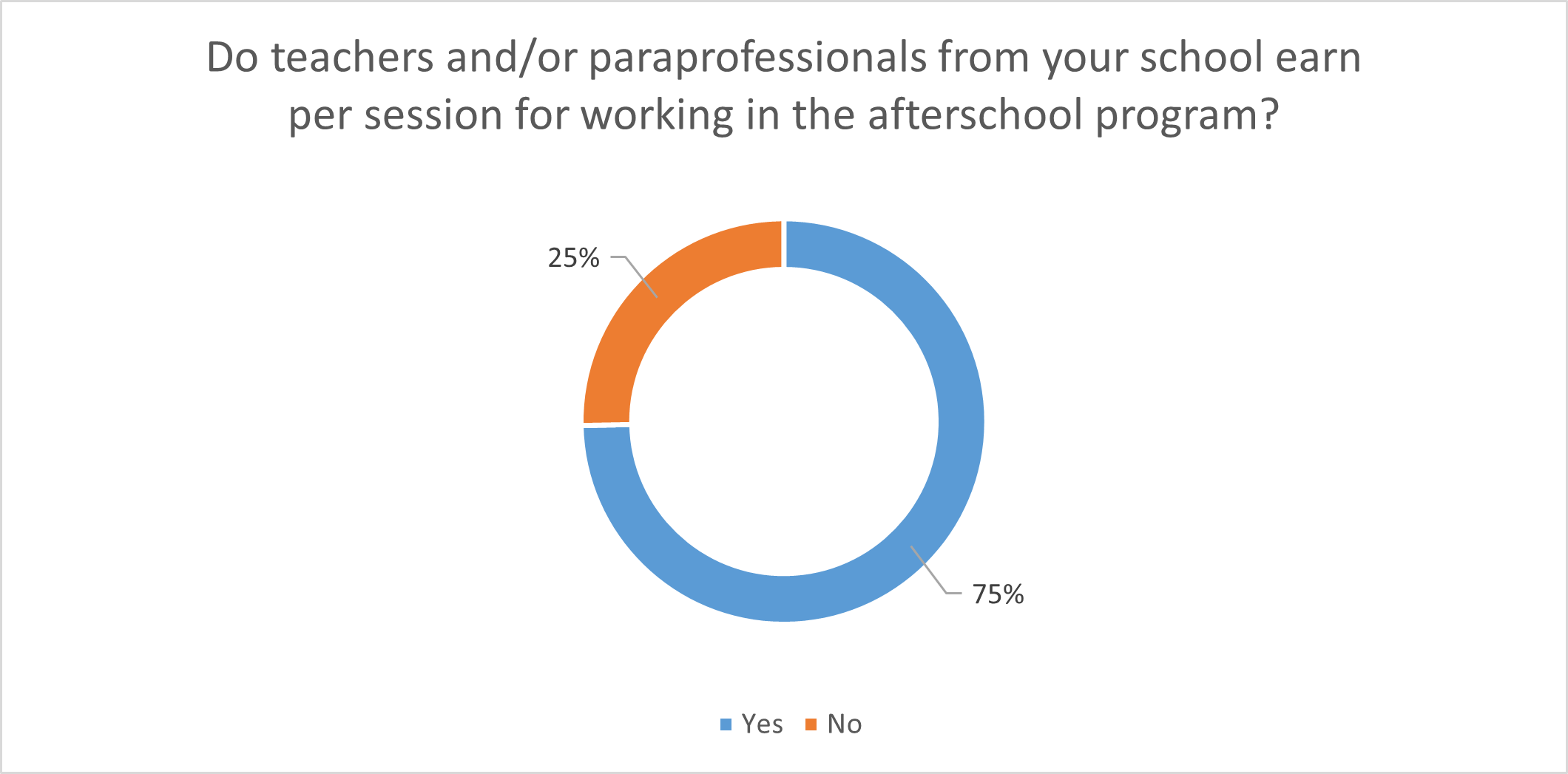

- Structural issues in how afterschool programs are funded and operated leave District 75 programs dependent on paying their own staff per session out of their school budgets, which significantly constrains schools’ ability to meet students’ afterschool needs:

- District 75 programs do not have access to the primary source of supplementary afterschool funding in the City: Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD). Unlike other schools with afterschool programming, most District 75 schools must pay directly for afterschool programming out of their own school budgets.

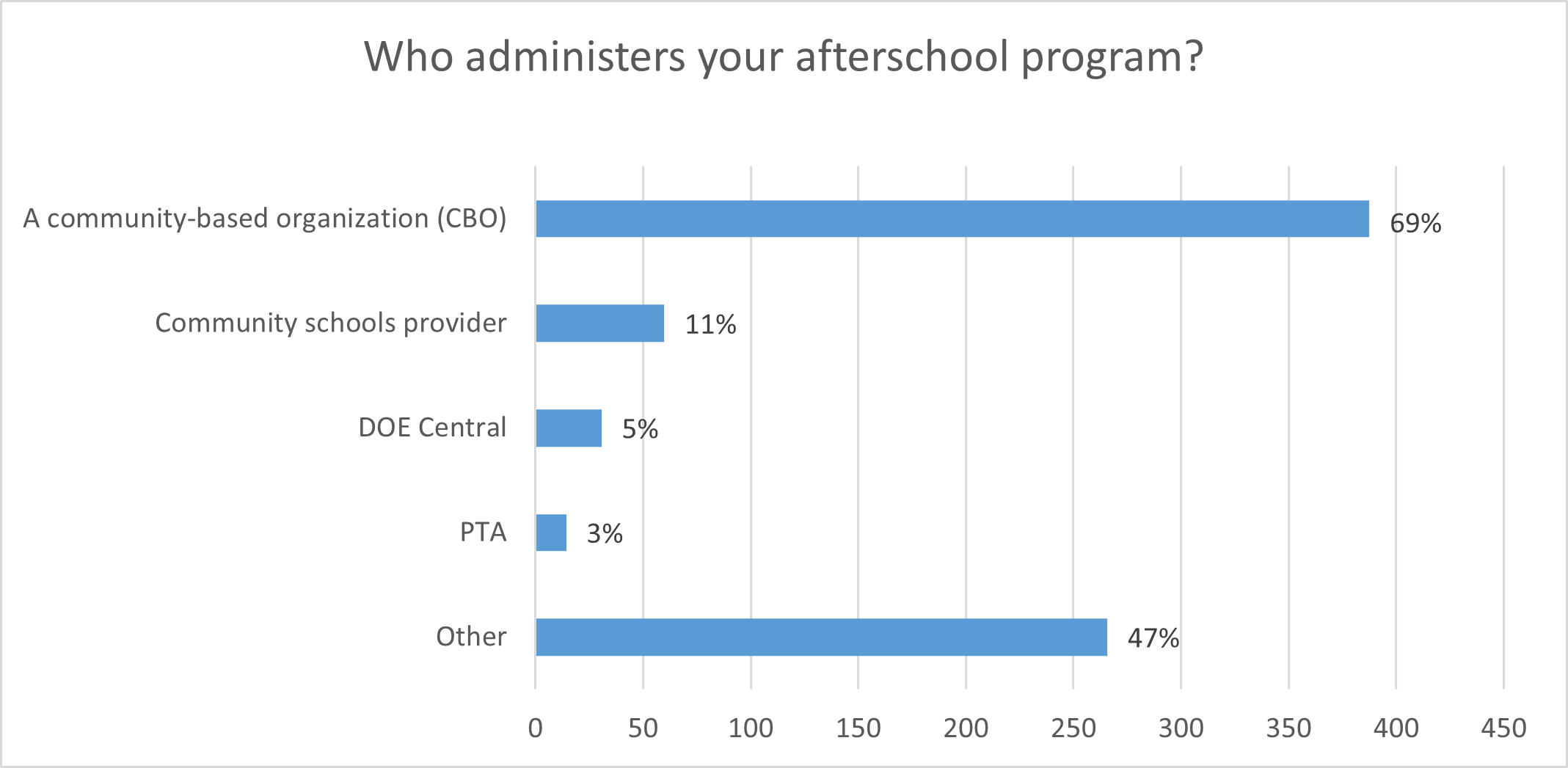

- Most contracted community based organizations (CBOs), which operate the vast majority of afterschool programming in New York City, are unable to meet the specialized needs of District 75 students, leaving District 75 staff to provide those services directly.

- A lack of afterschool bus transportation is a major barrier to afterschool care citywide, posing a particular challenge for the 62,000 students with IEP mandated school bus transportation:

- Nearly a third of all survey respondents and 100% of District 75 respondents named the lack of school bus transportation as a barrier to student afterschool participation.

The 62,000 students with IEPs dependent on school bus transportation in New York City exceeds the total public school enrollment in Seattle, Washington and has increased 9% between June 2022 and June 2024.[4] A true universal afterschool program must ensure that students with disabilities have the same access to afterschool as their peers. To confront this challenge, this report recommends a comprehensive strategy for addressing the needs of students with disabilities as the City designs and rolls out its universal afterschool program, including:

- Create dedicated afterschool funding for District 75 programs;

- Survey schools annually on afterschool needs;

- Increase City Council investment in Cultural After School Adventures (CASA), an afterschool arts program, with a focus on District 75 programs;

- Pilot a specialized Department of Education (DOE) Multiple Task Award Contract to help District 75 schools access appropriate afterschool vendors;

- Collaborate with United Federation of Teachers (UFT) to offer afterschool per session bonuses for special education staff.

To improve access to universal afterschool programs and address long-standing challenges in providing high-quality bus transportation for students with disabilities, the City and State must:

- Prioritize passage of New York State Senate bill S1018/Assembly bill A8440 which amends state education law to allow DOE to use employee protection provisions in new bus contracts. Until this legislation is passed, the DOE should avoid long-term extensions when the school bus contracts expire in June 2025 to keep the door open for a rebid that includes stronger worker protections and service improvements such as afterschool transportation;

- Competitively rebid school bus contracts with updated terms, including afterschool, Summer Rising, and Saturday service.

Background

Even prior to the Mayor’s announced program expansion in April 2025, New York City operated the largest publicly funded after school program in the country, spending $447 million in FY2025, including $427.5 million for DYCD’s Comprehensive After School System (COMPASS) and School’s Out NYC (SONYC) programs, and an additional $19.5 million for CASA. Altogether, City funding for afterschool programming has increased 48% over the last decade, which is largely driven by increased investments in DYCD afterschool programs. Additional funding sources that support school-based afterschool programs include Child Care Block Grant voucher funding, school-based allocations such as Fair Student Funding (FSF) and District 75 funding, federal Title I and Title III funding, and a $38.7 million New York State Learning and Enrichment Afterschool Program Supports (LEAPS) grant.

The Mayor’s April 2024 announcement included an increase of $331 million in additional DYCD funding incrementally baselined through FY2028, but does not include any increase in support for other school based programs funded by FSF or District 75 funding.[5] DYCD funding currently supports 164,000 afterschool slots. The Mayor’s plan increases DYCD’s existing 164,000 slots by an additional 20,000 seats in kindergarten through 5th grade—grade bands that lack DYCD afterschool seats relative to middle school grades. The FY2026 executive budget includes an initial $21 million investment for 5,000 additional K-5 seats which will be available in fall 2025. The City committed to increasing that allocation to $102 million in FY2027 and $136 million in FY2028, which will add 10,000 more DYCD seats in the fall of 2026 and 5,000 seats in the fall of 2027, bringing total DYCD seats to 184,000 by FY2028. Importantly, the plan will rebid decades-old DYCD contracts with updated rates that better match the current cost of care—something for which CBOs and advocates have long advocated.[6]

While the Mayor’s announcement will increase access to afterschool programming, it will likely still fall short of meeting the citywide need. According to DOE enrollment data, New York City is home to 815,000 children between the ages of 5 and 14 who attend public school.[ii] Using the limited available seat information for publicly funded afterschool programs in New York City, the Mayor’s announcement will increase the total current number of publicly funded afterschool seats to 220,351 students, which includes the 184,000 DYCD seats and an estimated 36, 351 child care block grant funded vouchers administered by the Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) that go to school-age children. The Comptroller’s Office estimates an additional need of 392,000 afterschool seats which remain unfunded by the Mayor’s plan. Given the number of students with IEPs that rely on bus service, an estimated 15% of these unfunded seats represent students with disabilities.

For the 28,000 students in District 75 with highly specialized needs, the Mayor’s plan to increase DYCD-funded CBO-provided afterschool seats will not offer them any additional afterschool opportunities. District 75 programs are funded outside of FSF via a lump sum School Allocation Memorandum (SAM). Any funding for afterschool often comes out of that funding and generally goes toward per session for teachers, as most DYCD funded CBOs are not equipped to meet the specialized needs of District 75 students. This is true even for District 75 programs that are co-located with general education schools.

Analysis

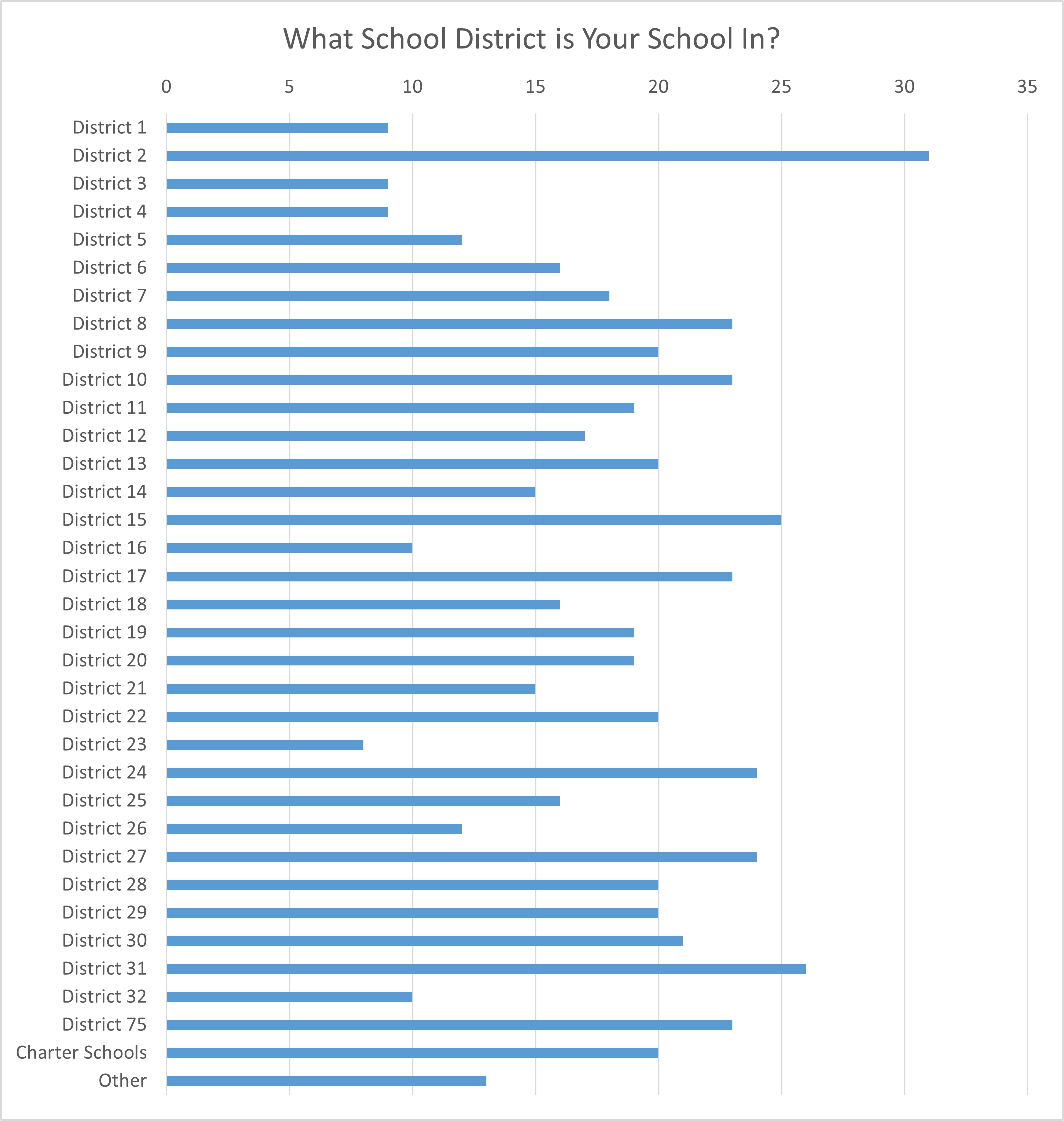

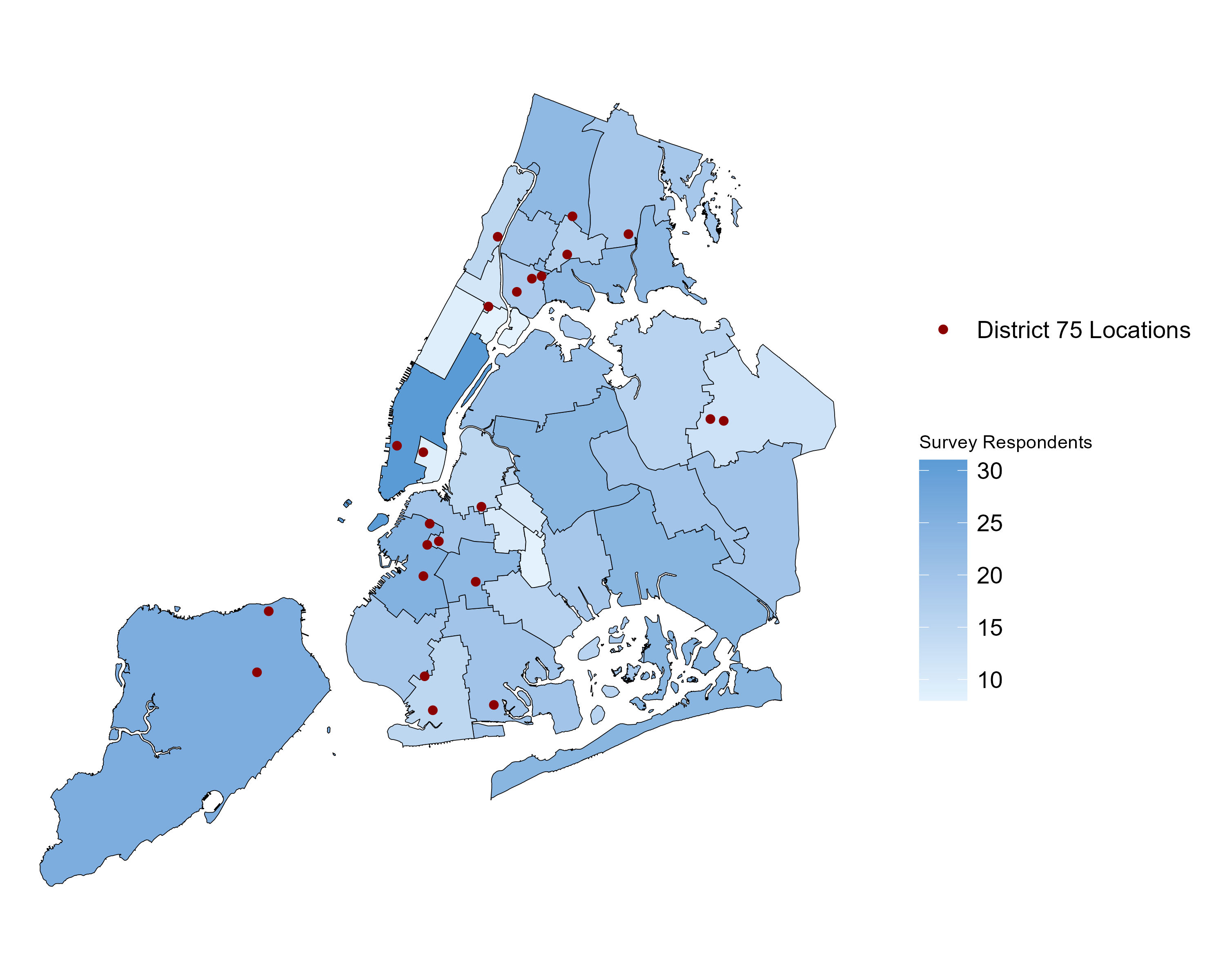

The Comptroller’s Office conducted a survey of public and charter school leaders in March 2025 to better understand the issues confronting school-based afterschool programs. As evident in Map 1, the 627 responses came from school leaders in every New York City school district, including 23 schools in District 75. Additionally, the Comptroller’s Office reviewed historical school bus performance data using DOE’s publicly available Student Transportation Reports published bi-annually in accordance with Local Laws 26, 31, 33 and 34 since the 2018-19 school year.

Map 1. Geographic distribution of afterschool survey responses

Source: NYC Comptroller’s Office Survey of School Leaders[iii]

Survey Findings

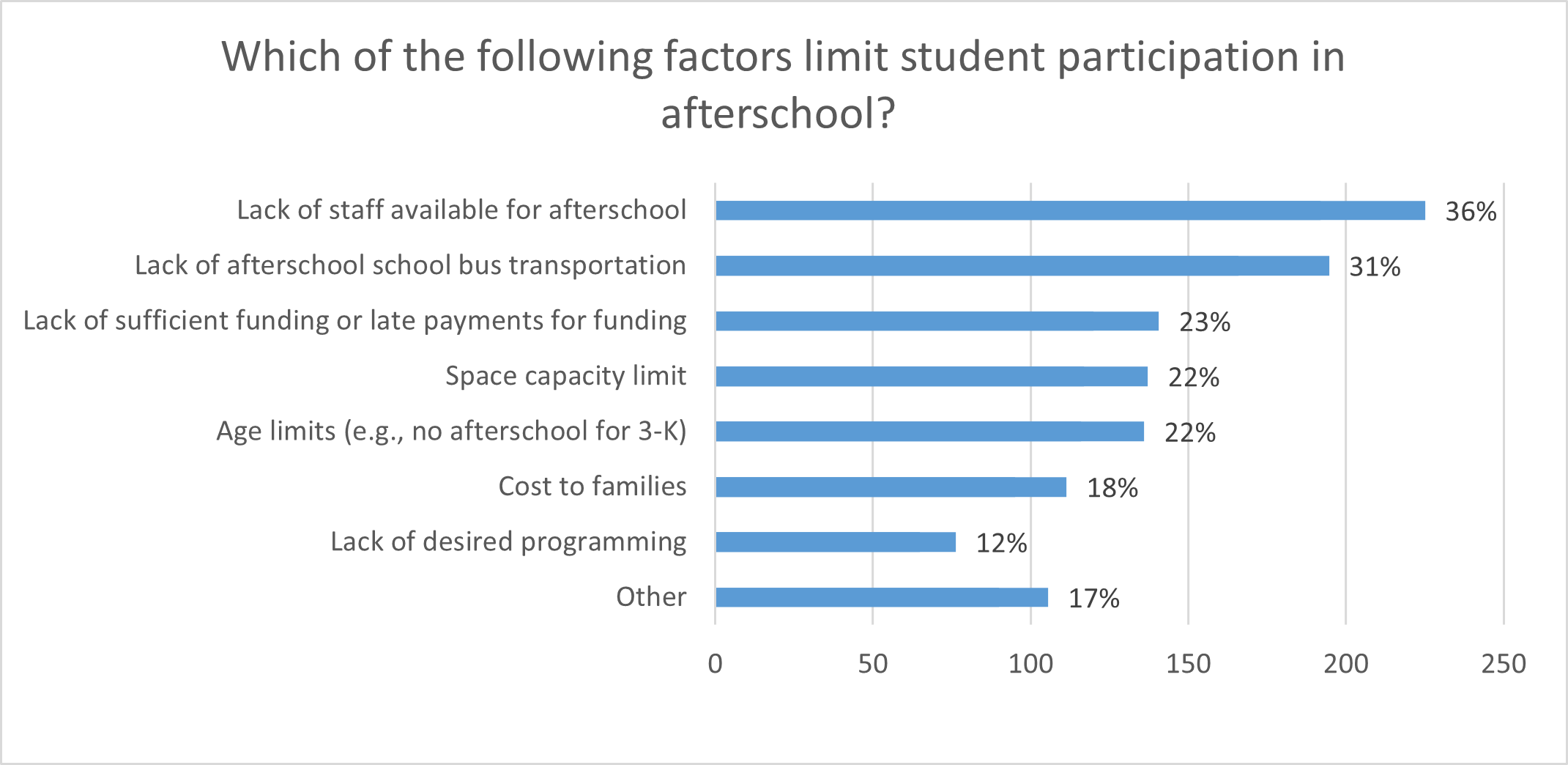

Students with disabilities have less access to afterschool than many of their peers. 93% of non-District 75 school leaders who responded to the survey reported having afterschool programming. Yet only 74% of District 75 school leaders who responded to the survey reported having afterschool programs. Based on findings from the survey there are two reasons for this disparity in afterschool programming for District 75 students. The first major issue is the lack of afterschool busing. 100% of District 75 respondents with afterschool programs reported that lack of busing is a barrier to student participation.

Lack of school bus transportation limits access to afterschool outside of District 75 as well. This includes a lack of access for students in temporary housing who have legally mandated busing based in the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act of 1987, as well as students with disabilities who have mandated busing that attend community district schools. Overall, 32% of all respondents noted that lack of afterschool transportation is a barrier to student participation.

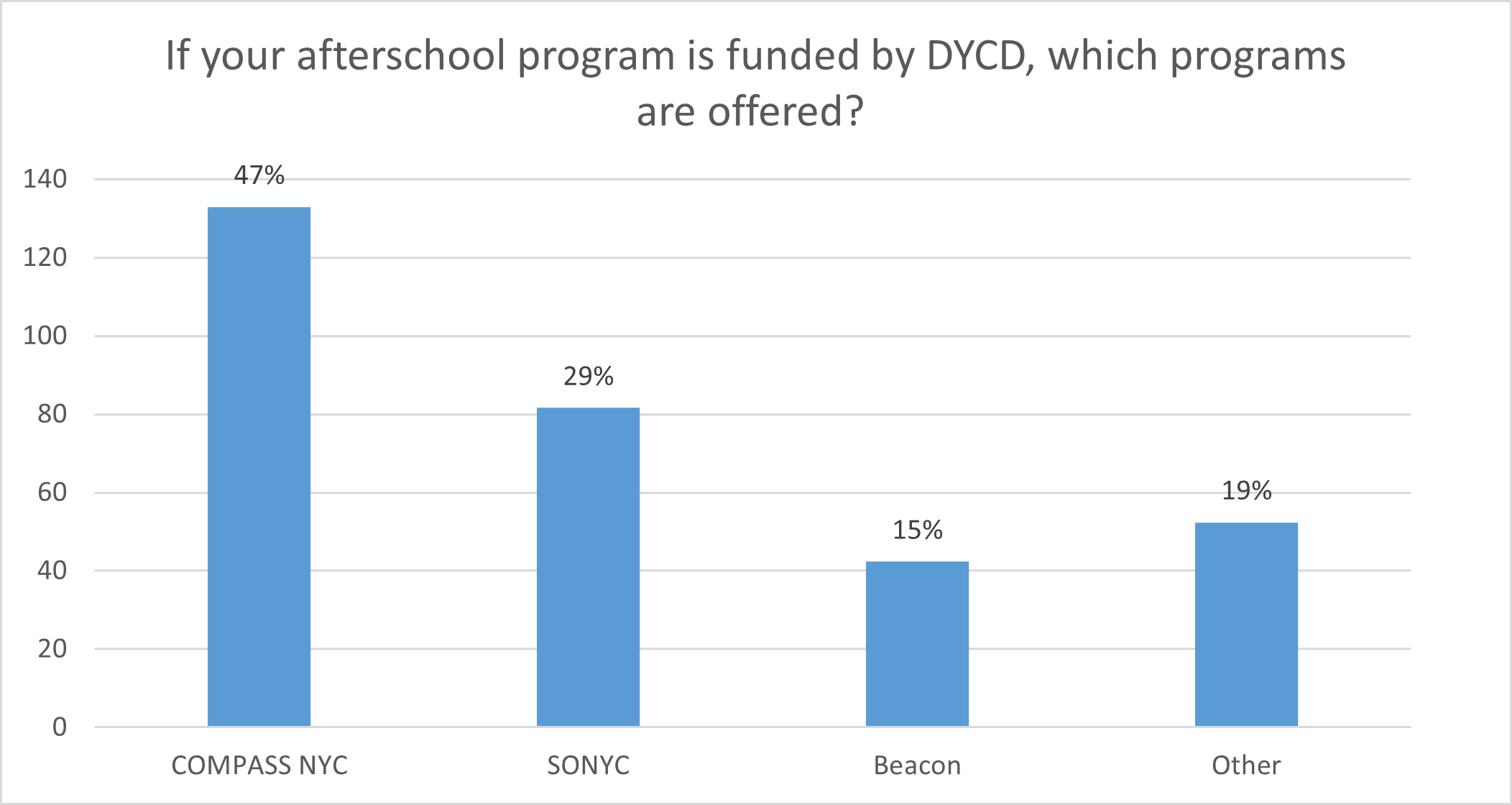

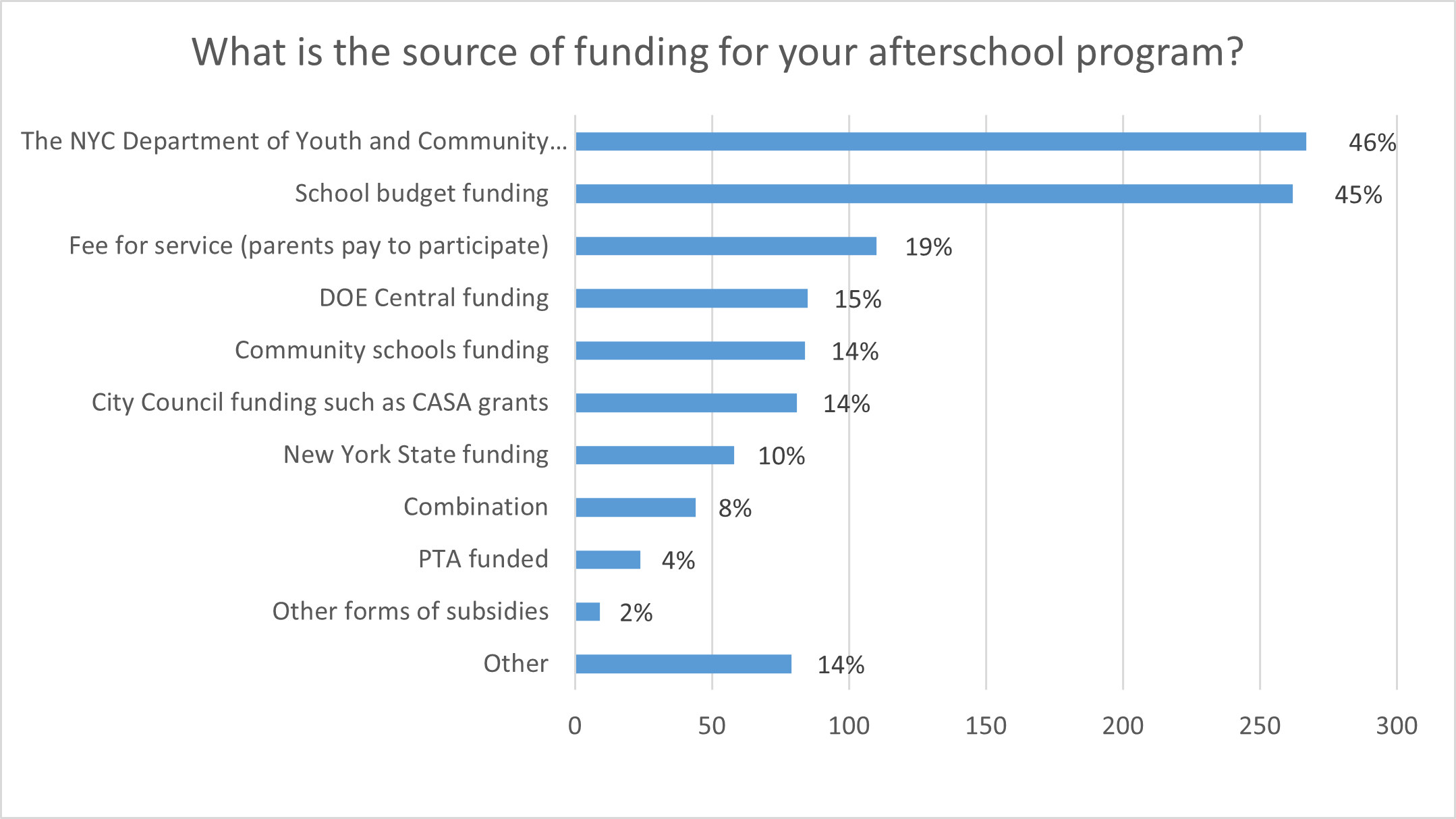

The second major barrier to afterschool access for District 75 schools is the limited types of funding available to them. Survey results indicate that many District 75 schools do not have access to programs funded through DYCD—the largest source of afterschool funding citywide (utilized by 49% of other schools)—which enables partnerships with CBOs to provide programming (see Chart 1). Instead, District 75 programs rely more heavily on funding from DOE Central: 71% of District 75 programs surveyed are funded this way, compared to just 13% of other schools.

District 75 schools also receive significantly less support from City Council CASA grants, which fund arts-based partnerships with CBOs—only 6% of the District 75 schools benefit from CASA grants, compared to 15% of other respondents. This funding imbalance impacts how programs are administered. While 90% of the afterschool programs overall are managed by CBOs, District 75 schools rely far more on school-based programming provided by school staff according to the survey. As a result, 50% of District 75 afterschool programs surveyed are administered directly by DOE Central, compared to just 7% of other schools. Despite the lack of public funds available, there are also fewer fee-for-service programs where parents pay for program costs in District 75 (6%) compared to all other respondents (20%). This dynamic dramatically constrains the reach of these in-school programs and often leaves families to figure out afterschool programming on their own.

Chart 1: Reported Funding Sources for Afterschool Programs

Source: NYC Comptroller’s Office

Student Transportation Data Findings

DOE provides contracted school bus transportation to 145,000 NYC students, including an increasing number of students with disabilities.[7] The Comptroller’s Office estimates that in the last school year, approximately 60,000 students were assigned “curb-to-school” bus routes, a designation which indicates that a student is picked up and dropped off at their residence (as opposed to a communal bus stop) and is almost entirely comprised of students with IEP mandated transportation. The number of students with curb-to-school routes in June 2024 increased by 9% over June 2022.

Chart 2: Increasing numbers of students that require curb-to-school bus service

Source: NYC Department of Education

Unfortunately, DOE’s provision of school bus service fails to meet the needs of many families and students in New York City. This is in part due to outdated contract terms—52 school bus vendors currently operate under contracts that, for the most part, have not been competitively rebid since 1979.[8] DOE’s current contracts do not include service for afterschool, weekend programs, and Summer Rising, preventing students who rely on bus transportation from participating in these activities.[9]

Rebidding DOE’s bus contracts to provide needed updates like afterschool service is complicated. The 17,500 drivers that provide contracted bus service for DOE have essential labor protections under the current contracts. DOE’s ability to rebid its bus contracts and include these labor protections is hampered by a 2011 State Court of Appeals decision (L&M Bus Corp. v New York City Dept. of Educ.). This ruling prevents the City from issuing new contracts without removing the Employee Protection Provisions (EPPs), which guarantee drivers their jobs along with their wage and benefit levels when their employer goes out of business and/or a different contractor is awarded the job.[10] Legislative intervention from New York State is needed to both preserve the EPPs and allow the DOE to competitively rebid these contracts to improve bus service while adequately protecting workers. Senate Bill S1018/Assembly Bill A8440 accomplishes this as an amendment to NY State Education Law.[11] The passage of this bill would allow DOE to competitively rebid their bus contracts, modernize and upgrade terms including provision of afterschool transportation, and greatly improve the lives of the families and students that rely on these services and the hard-working drivers that provide them.

Recommendations

Build towards a truly universal system of afterschool that includes all students with disabilities

- Create dedicated afterschool funding for District 75 programs. DOE should survey every school annually as part of the budgeting process on their afterschool needs and funding sources and create an afterschool School Allocation Memorandum (SAM) for District 75 programs.

- Increase City Council investment in CASA by $10M per year prioritizing funding to District 75 schools. This Department of Cultural Affairs administered program matches individual schools with afterschool arts providers. DOE has been increasing the number of co-located District 75 programs across the city to ensure students can attend schools in more inclusive settings in their own neighborhood. The City Council should support this effort by allocating additional CASA funding to District 75 programs.

- DOE should pilot an Afterschool for All Multiple Task Award Contract (MTAC) to identify vendors that can support District 75 programs. Centrally procured MTACs give schools choice and flexibility in selecting vendors for needed services. An Afterschool for All MTAC would allow schools to secure specialized programming for students with disabilities that they may not be able to access via local CBOs.

- Collaborate with UFT to create an afterschool per session bonus to encourage special education teachers and paraprofessionals to participate in extended day programming.

Rebid DOE’s bus contracts

- Pass New York State Senate bill 1018/Assembly bill 8440 to allow DOE to reprocure their bus contracts while maintaining critical employee protections. Until that bill is passed, DOE should limit its extensions on existing contracts to just one year. All but one of DOE’s school bus contracts expire on June 30 and DOE must not enter long term extensions that would preclude rebidding the contracts by next June.

- Competitively rebid the City’s bus contracts and update terms to include afterschool and weekend service. The inequity in access to afterschool due to lack of school bus service, especially for students with disabilities in every school, is profound and can only be addressed by adding afterschool, Saturdays and Summer Rising to a new busing Request for Proposals (RFP). DOE must begin a new procurement process that will allow new bus contracts to be in place before the start of FY2028.

Conclusion

The City is at a pivotal moment for students with disabilities, who make up one-fifth of all New York City public school students yet continue to be left out of so-called “universal” initiatives like Pre-K and 3-K. Afterschool is no exception—and for the Mayor’s universal afterschool plan to live up to its name, it must include a clear path for students with disabilities to participate.

Until the City centers students with disabilities in its decision-making, families will continue to shoulder this burden—fighting for access to afterschool programs, special education preschool seats, basic building accessibility, and reliable transportation to get to school on time. The City must prioritize funding to assure universal access and inclusion for all students, including students with disabilities.

Acknowledgements

This report was authored by Lara Lai, Senior Policy Analyst and Strategic Organizer for Education; Robert Callahan, Director of Policy Analytics; Matan Diner, Strategic Organizer, Workers Rights; and Annie Levers, Deputy Comptroller for Policy. Jacob Bogitsh, Policy Data Analyst, Daniel Levine, Senior Data Analyst and Products Manager, and Sara Azcona-Miller, NYC Urban Fellow supported the data analysis and research. Archer Hutchinson, Creative Director, and Addison Magrath, Graphic Designer, led the report design with assistance from Graphic Designer Addison Magrath.

Methodology

The office of the Comptroller developed a survey for school principals to assess school-based afterschool programs citywide. The survey was emailed to all NYC DOE and charter school leaders on March 14, 2025 with a return date of March 28, 2025.

The survey was comprised of 33 questions that addressed sources of funding, seat capacity and funding limitations, barriers to families from participating. The Comptroller’s Office emailed the survey to nearly 2,000 NYC schools and programs. 627 school leaders responded and that data was aggregated and analyzed. This included responses from 23 District 75 programs.

Historical school bus complaint data was collected and analyzed using DOE’s publicly available Student Transportation Reports published bi-annually in accordance with Local Laws 26, 31, 33 and 34 since the 2018-19 school year.

The number of students assigned to curb-to-school routes has increased from 2022 to 2024. From 2023 to 2024, the number of students assigned to curb-to-school routes grew by 3,419—approximately a 6% rise.

Appendix

Aggregate Results from the Comptroller’s Survey of New York City School Principals on Afterschool Programs

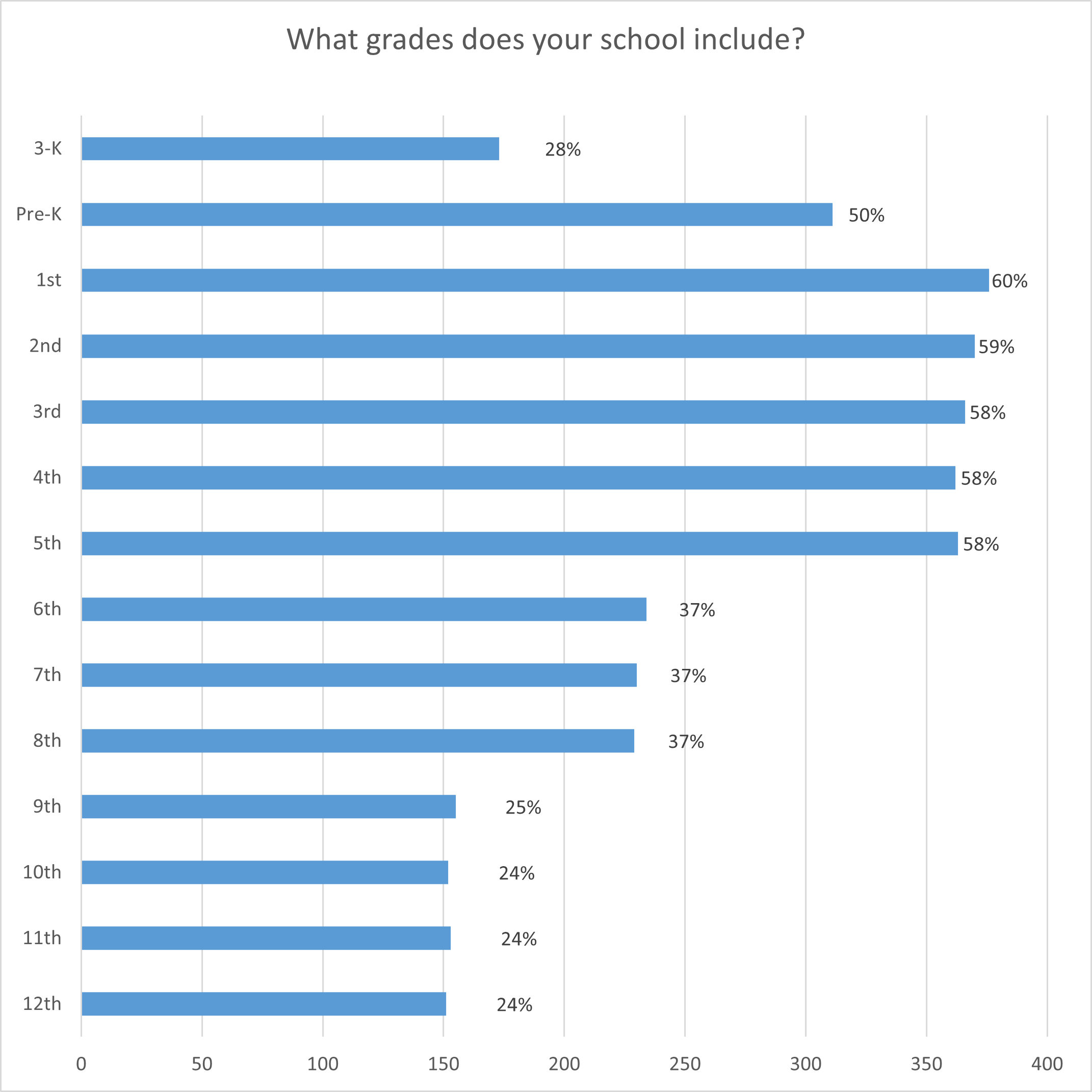

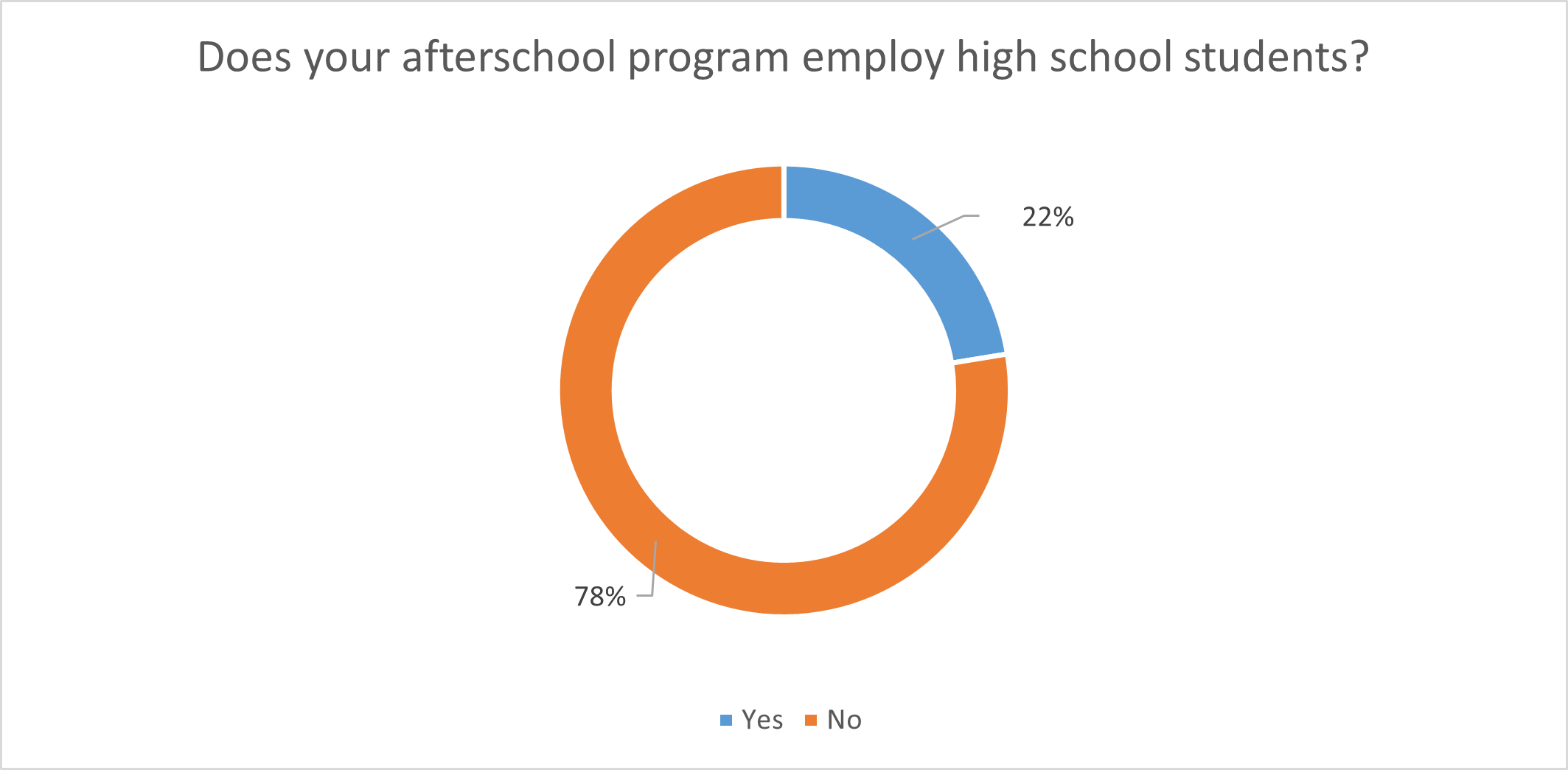

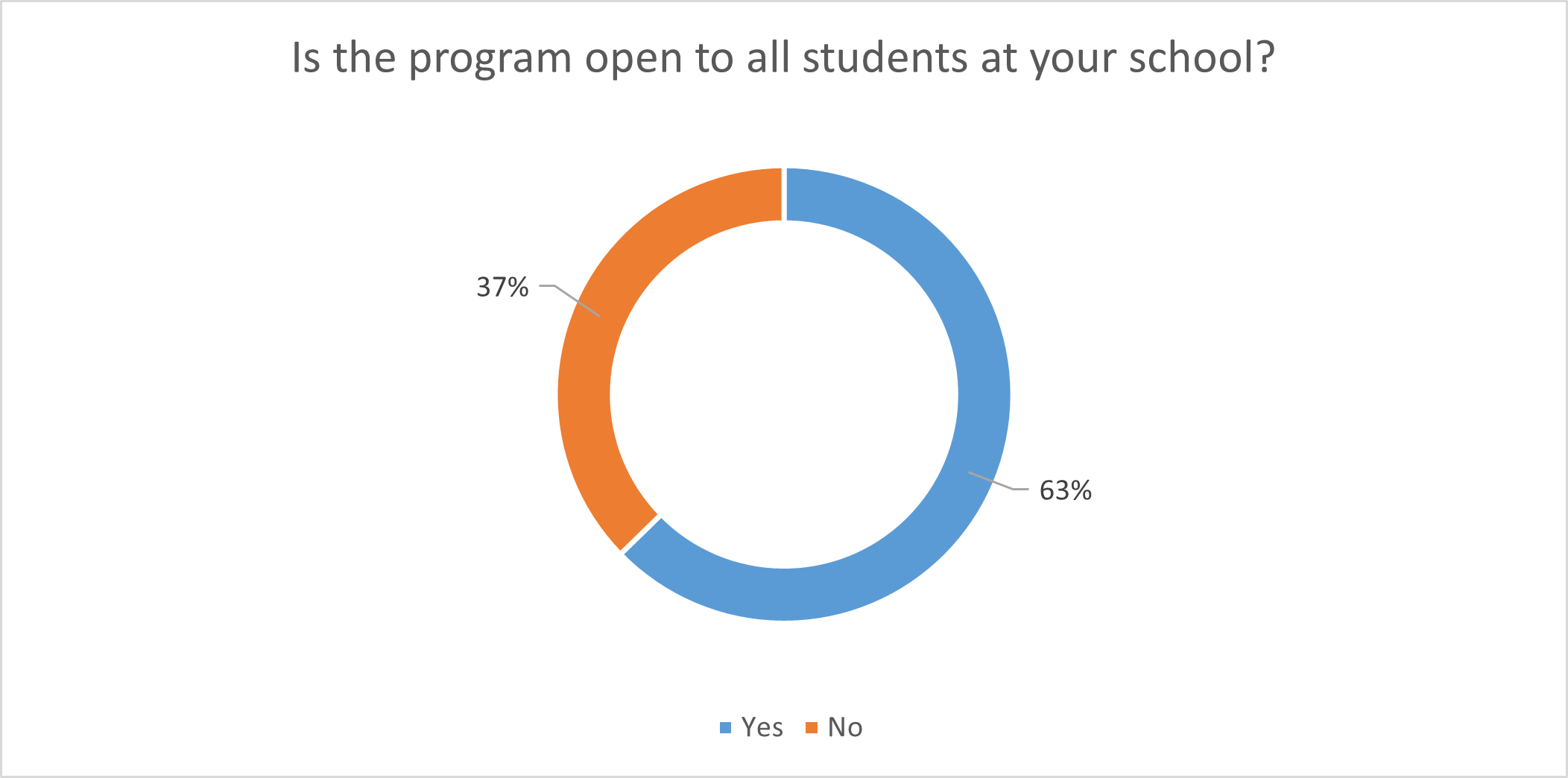

Chart A1

Note: These values have been standardized from the raw survey.

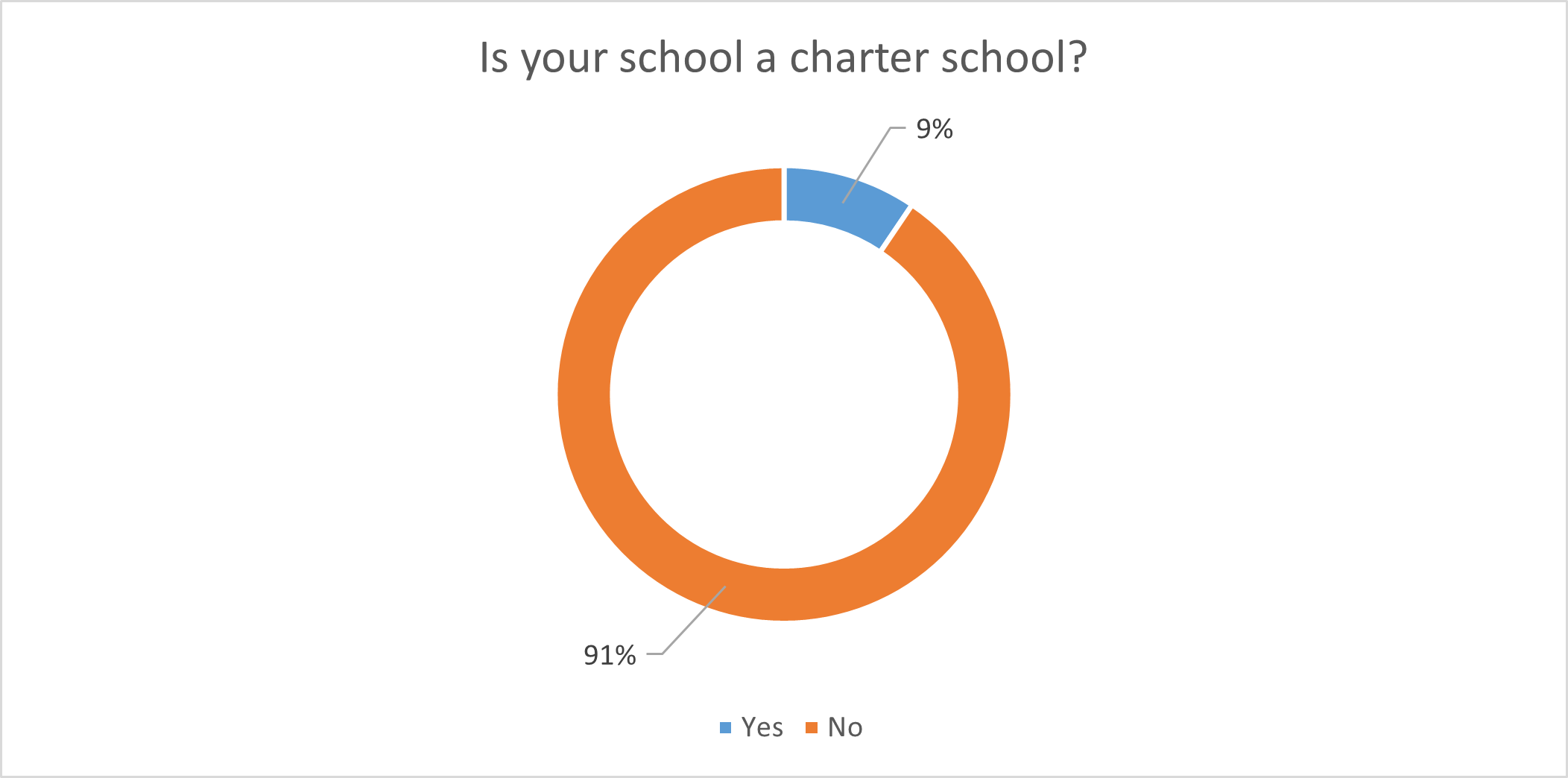

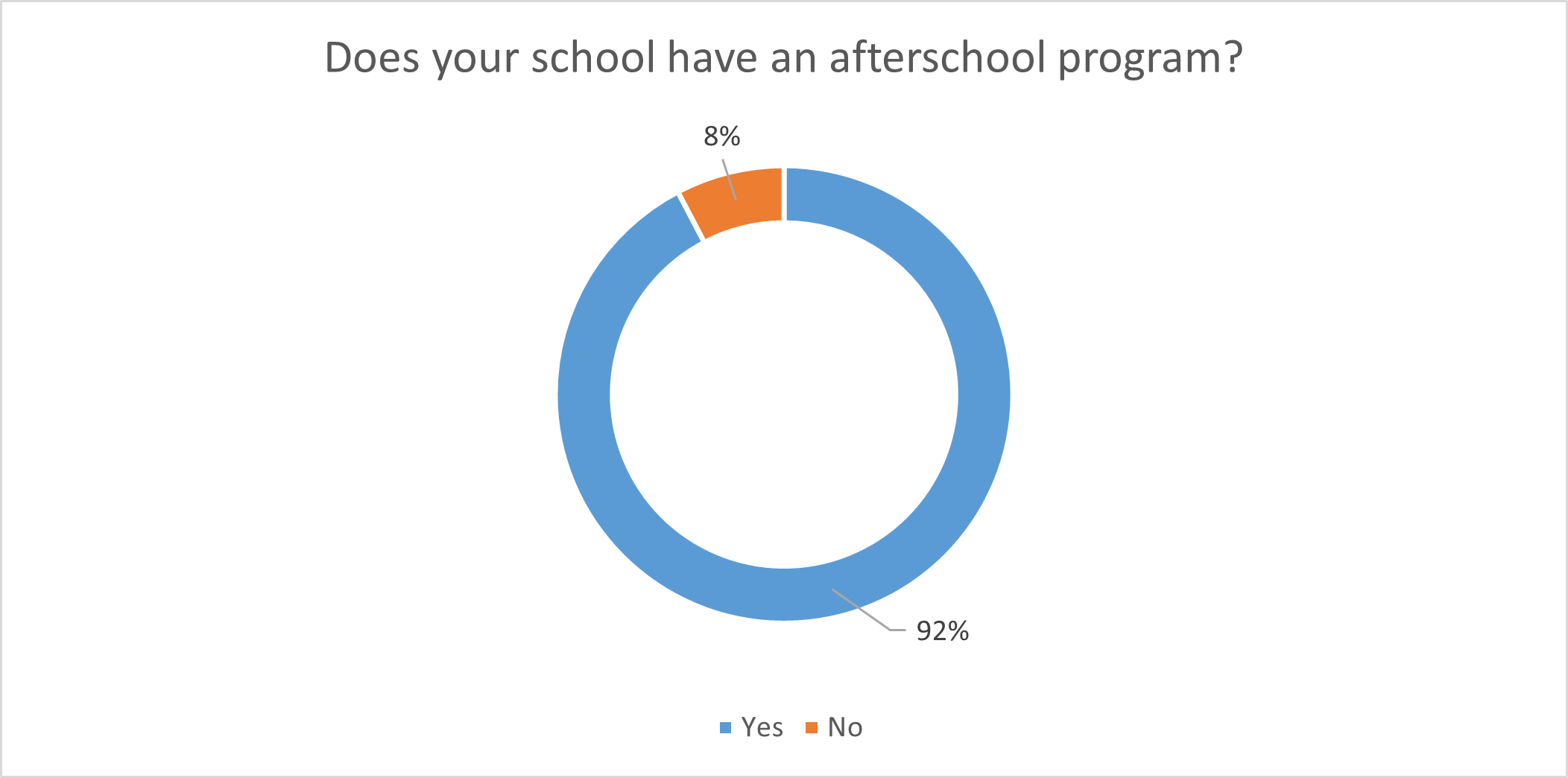

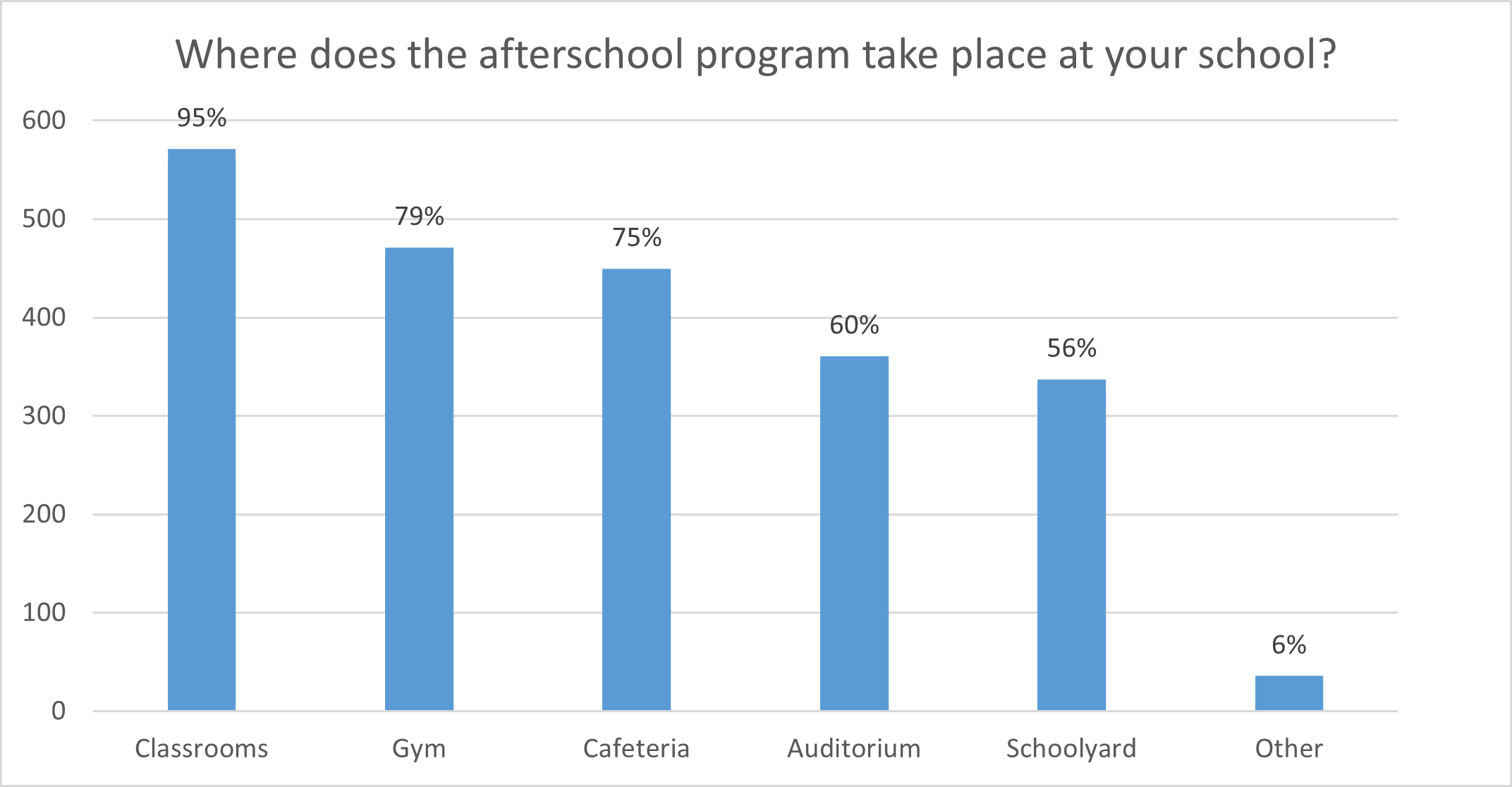

Chart A2

Number of respondents: 627

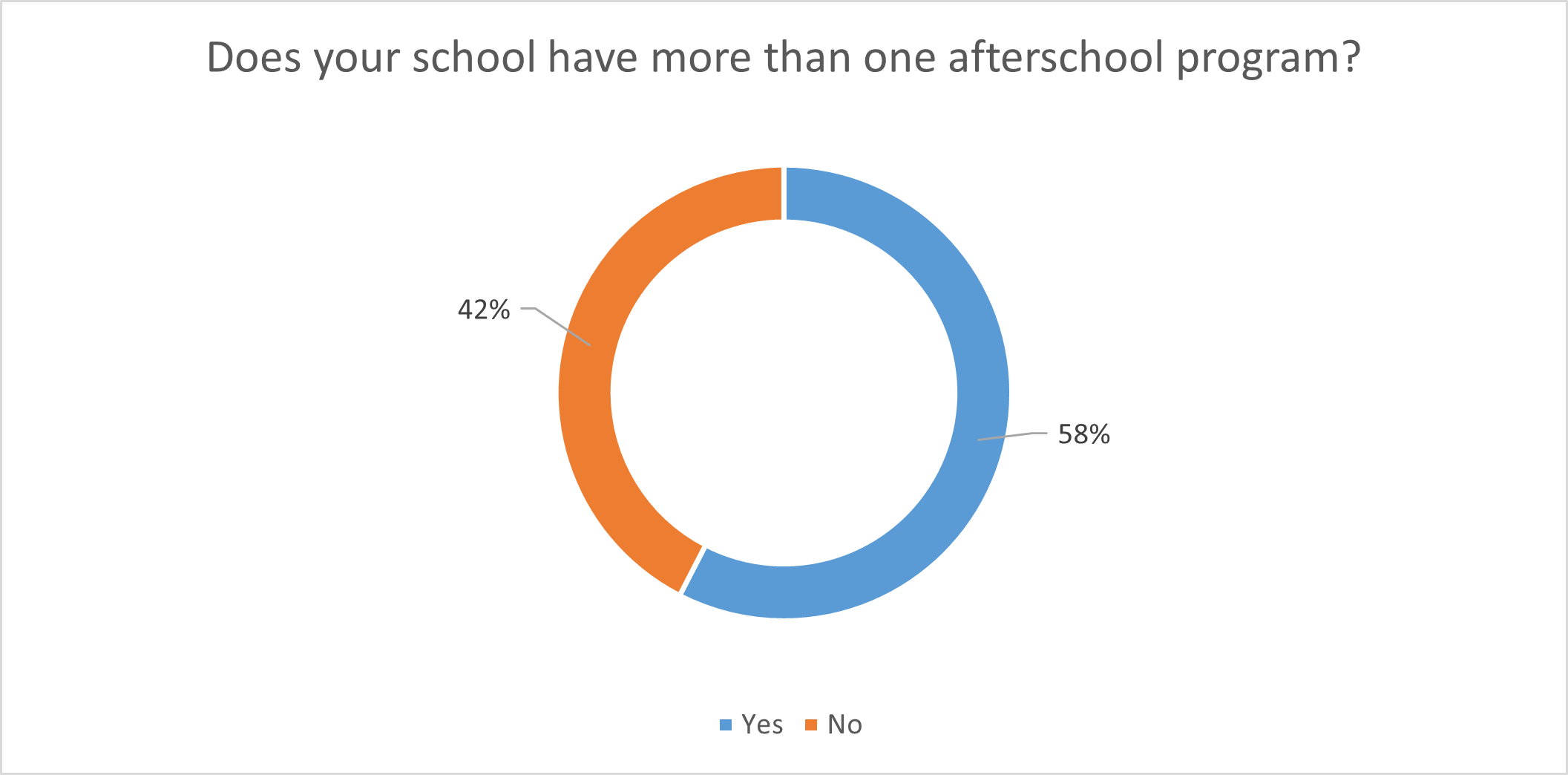

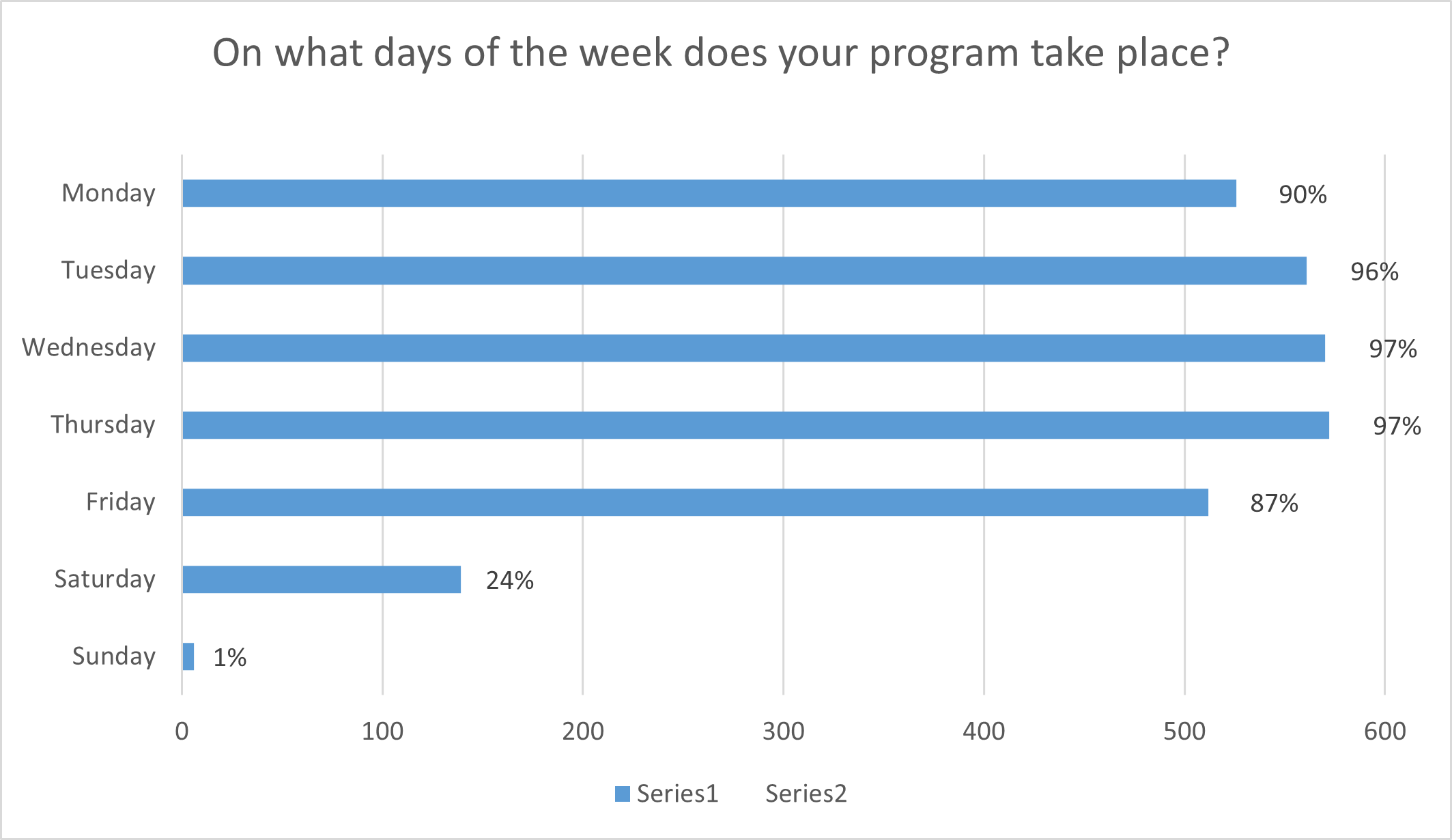

Chart A3

Number of respondents: 624

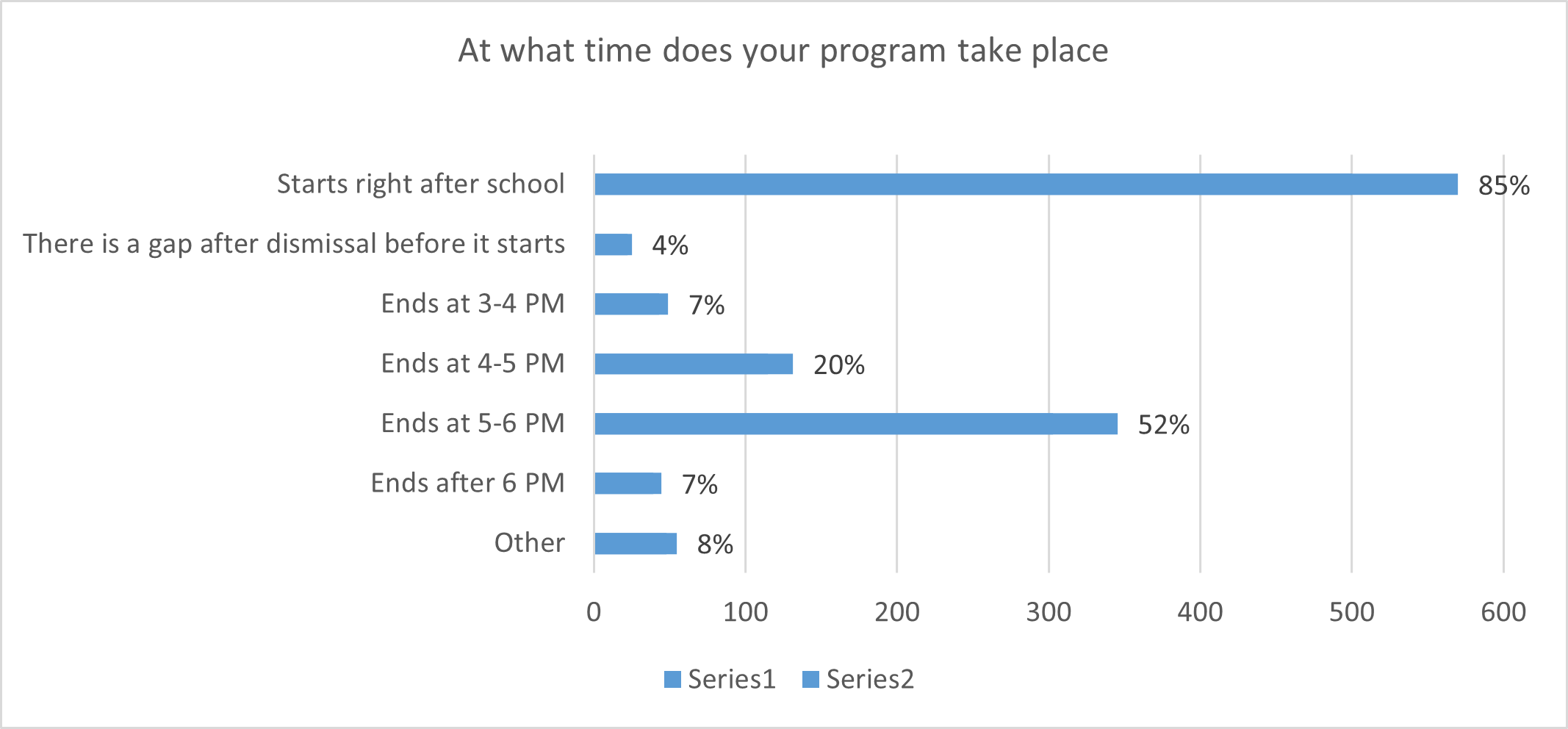

Chart A4

Number of respondents: 625

Chart A5

Number of respondents: 601

Chart A6

Number of respondents: 581

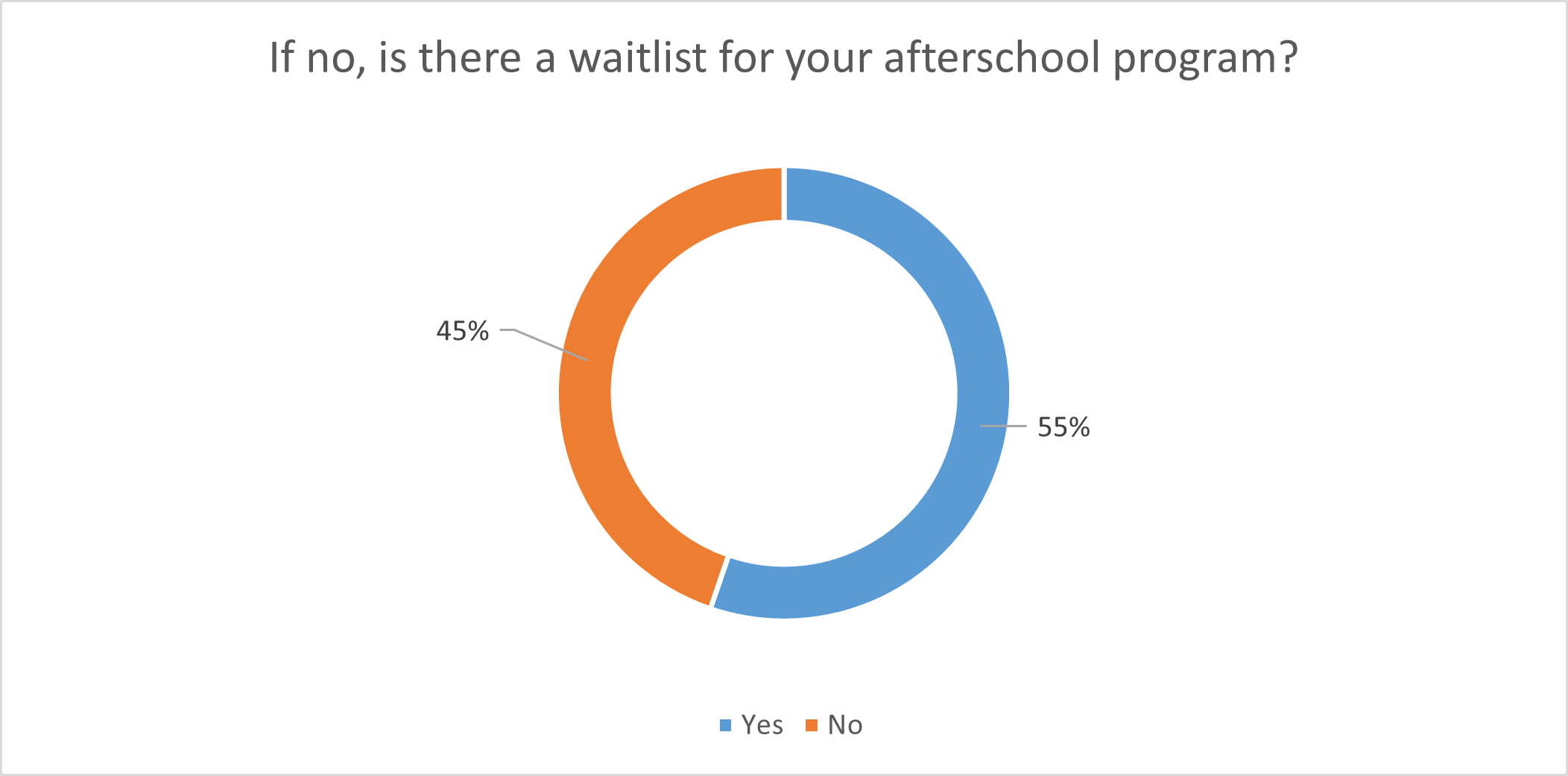

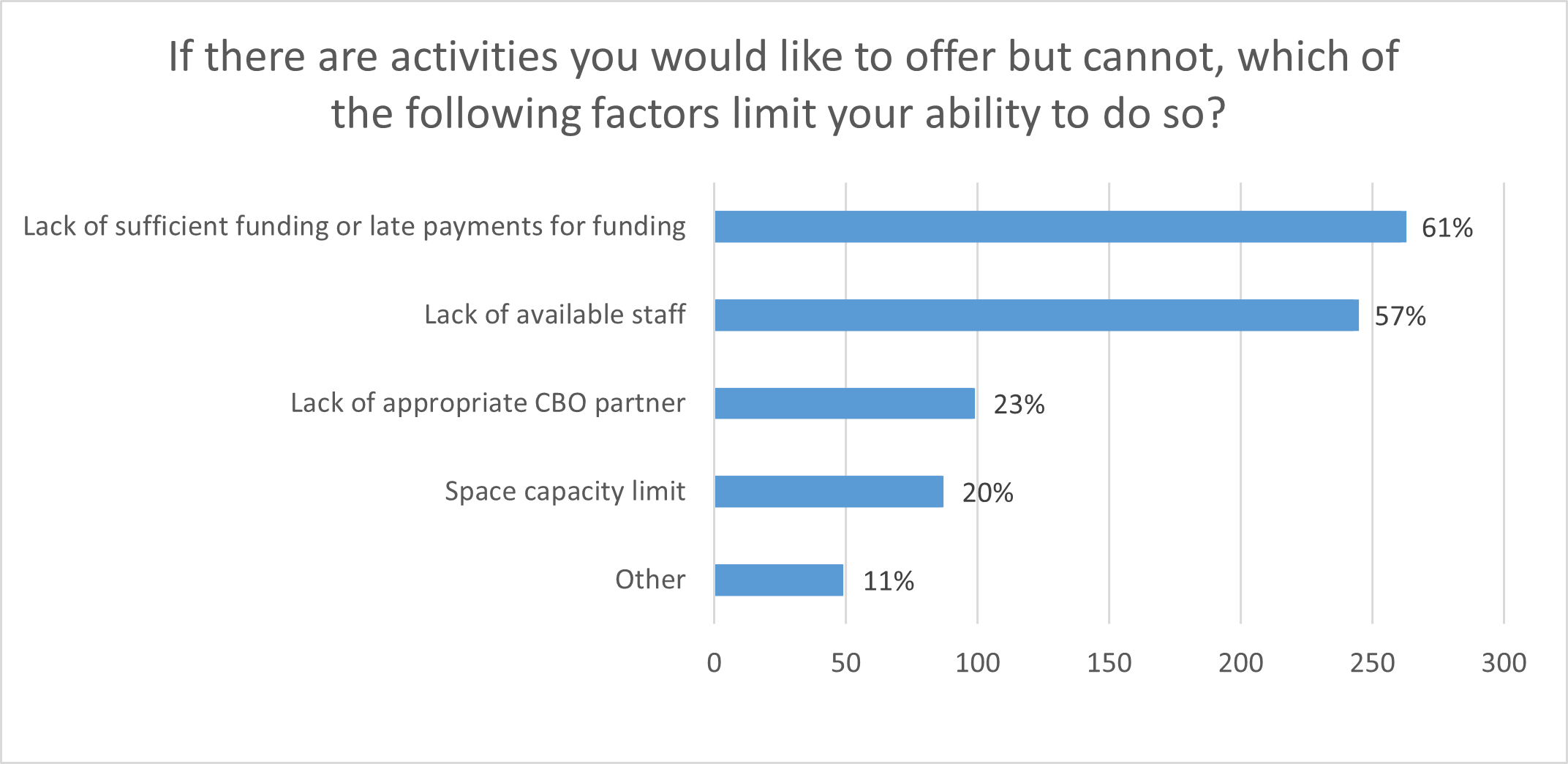

Chart A7

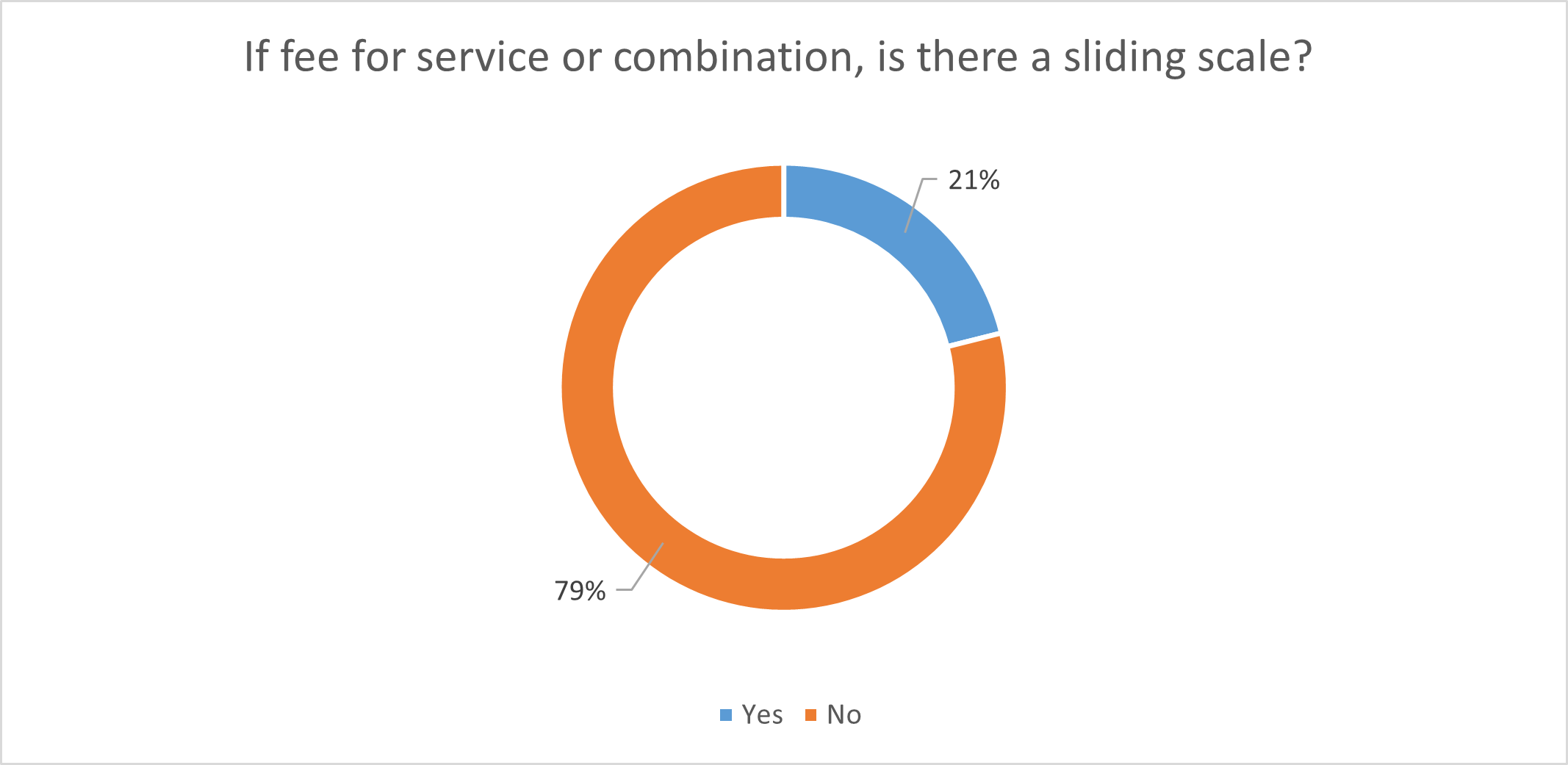

Number of respondents: 204

Chart A8

Number of respondents: 582

Chart A9

Number of respondents: 278

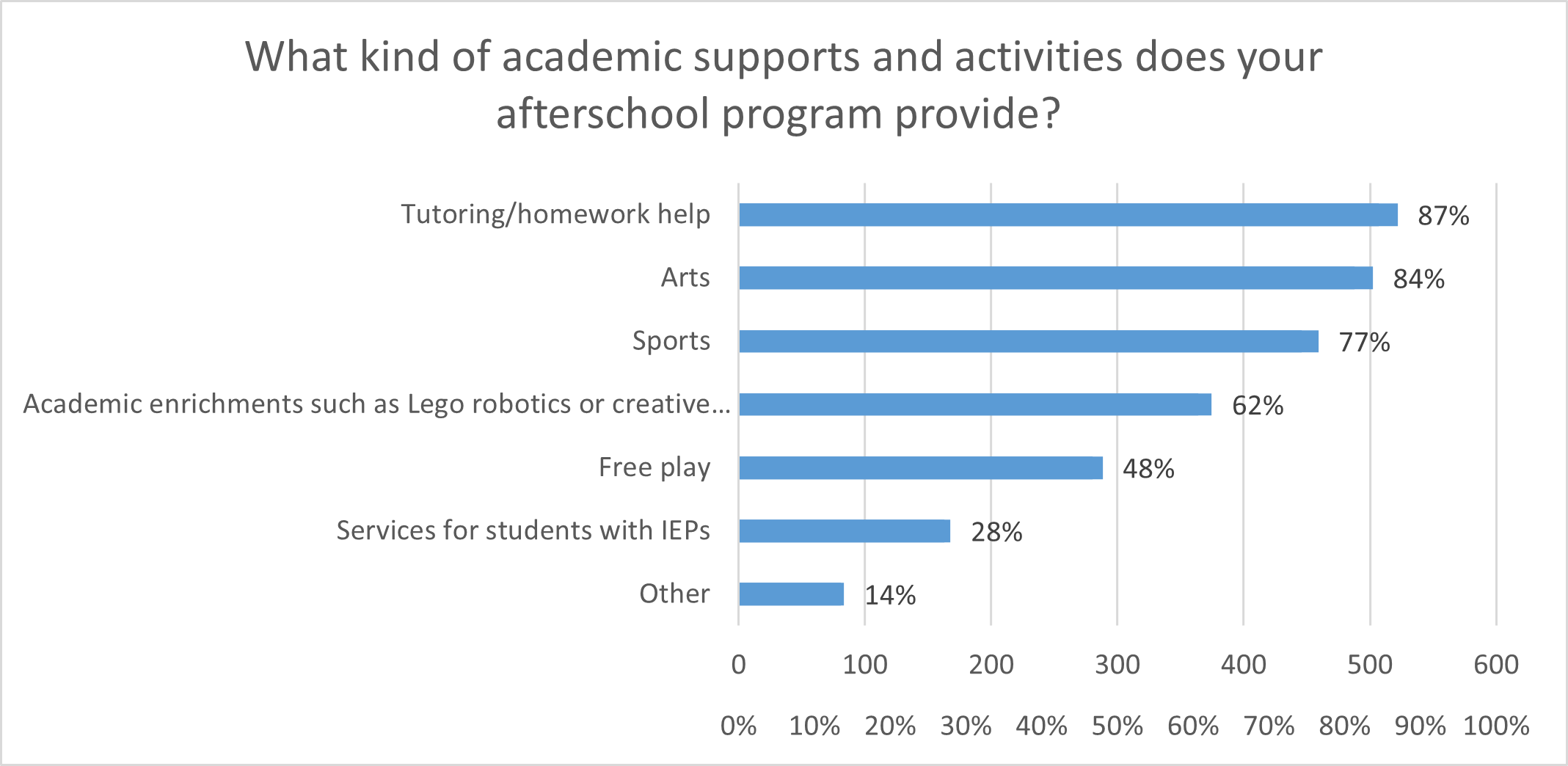

Chart A10

Number of respondents: 553

Chart A11

Number of respondents: 584

Chart A12

Number of respondents: 587

Chart A13

Number of respondents: 587

Chart A14

Number of respondents: 585

Chart A15

Number of respondents: 587

Chart A16

Number of respondents: 118

Chart A17

Number of respondents: 533

Chart A18

Number of respondents: 583

Chart A19

Number of respondents: 432

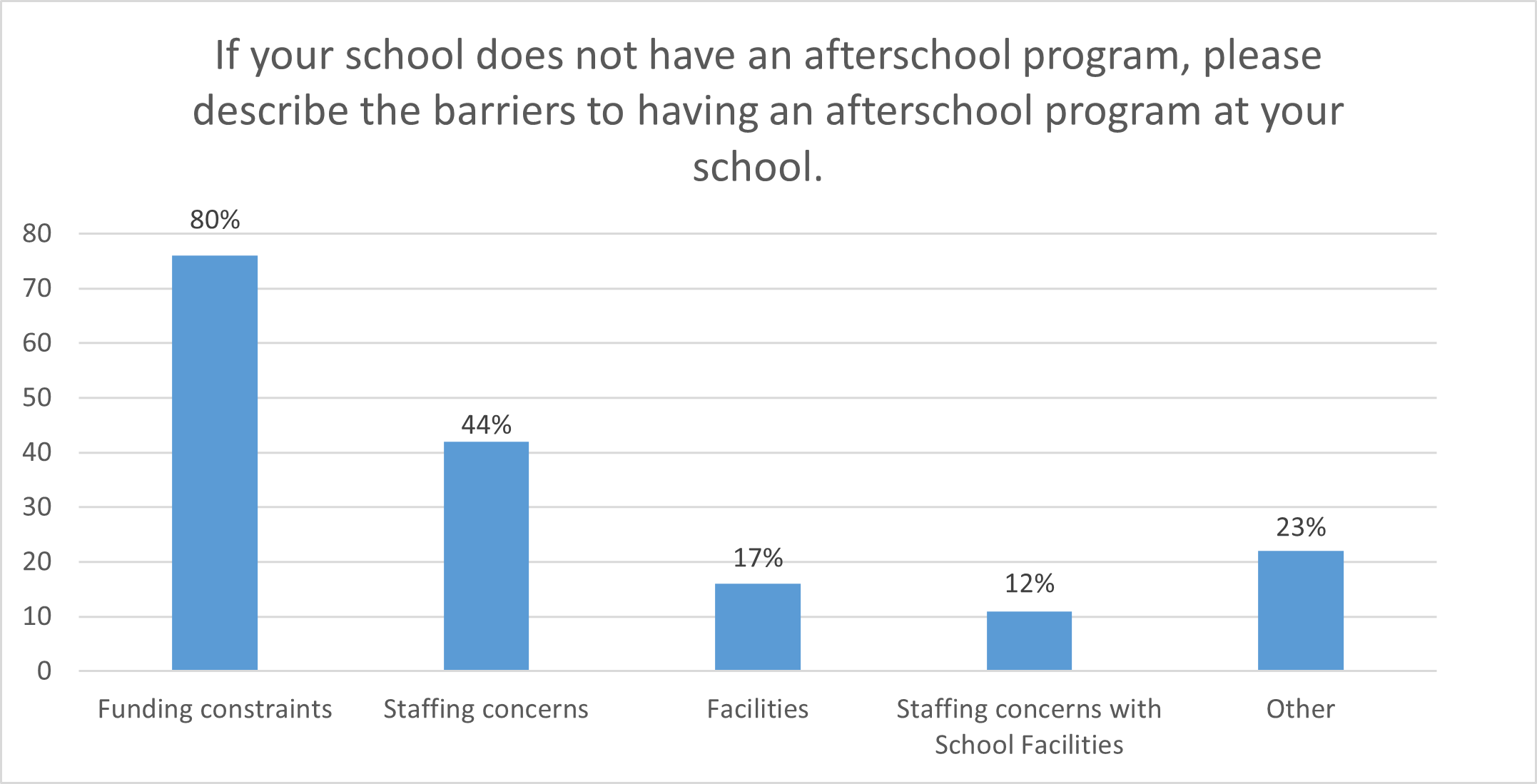

Chart A20

Number of respondents: 95

Footnotes

[i] District 75 is a non-geographic citywide district of 63 programs providing highly specialized instructional support for students with significant challenges that can include autism, cognitive delays, and sensory and emotional disabilities. A student’s IEP will recommend the type of District 75 program that meets that student’s educational needs. Leaders from 23 District 75 programs responded to the survey, representing 37% of the programs citywide.

[ii] While high school age students also participate in afterschool activities such as clubs and sports teams, those programs are not the focus of this report.

[iii] This map excludes 30 respondents from other non-geographic districts, including Charter Schools, Affinity Schools, and Transfer High Schools.

Endnotes

[1] From Stumbling Blocks to Building Blocks: A History of Afterschool in New York City. (2025, January 23). Partnership for Afterschool Education. https://pasesetter.org/resources/from-stumbling-blocks-to-building-blocks-a-history-of-afterschool-in-new-york-city

[2] New York City Department of Education Demographic Snapshot 2023-2024. Accessed at https://infohub.nyced.org/reports/students-and-schools/school-quality/information-and-data-overview

[3] Mayor Adams unveils ambitious plan to achieve universal after-school programming. (2025, April 29). The Official Website of the City of New York. https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/261-25/mayor-adams-ambitious-plan-achieve-universal-after-school-programming-upcoming#/0

[4] NYC Council Executive Budget Hearing – Education (2025, May 20). The New York City Council – Meeting of Committee on Education on 5/20/2025 at 10:00 AM

[5] Mayor Adams unveils ambitious plan to achieve universal after-school programming. (2025, April 29). The Official Website of the City of New York. https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/261-25/mayor-adams-ambitious-plan-achieve-universal-after-school-programming-upcoming#/0

[6] Bamberger, C. (2025, January 31). NYC after-school providers warn programs could close without more funds. New York Daily News. https://www.nydailynews.com/2025/01/30/nyc-after-school-providers-warn-programs-will-close-without-more-funds/

[7] NYC Council Committee on Education Oversight Hearing (2024, September 30). https://legistar.council.nyc.gov/MeetingDetail.aspx?ID=1230079&GUID=FC4D7817-BD5A-4527-9AB9-4DC16D2E3D91&Options=info|&Search=

[8] New York City Yellow Bus Service. (2022, April ). New York Appleseed. https://www.nyappleseed.org/wp-content/uploads/NYA_YellowBusReport_April2022_Final-1.pdf

[9] Fahy, C. Behind school bus mess, a 45-year-old contract that’s hard to change. (2024, October 1). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/01/nyregion/nyc-school-bus-delays.html

[10] Matter of L&M Bus Corp. v New York City Dept. of Educ., 71 AD3d 127, modified. (2011, July 27). (https://www.nycourts.gov/Reporter/3dseries/2011/2011_05114.htm

[11] Senate Bill S1018/Assembly Bill A8440. An act to amend the education law, in relation to contracts for the transportation of school children. https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2025/S1018