Executive Summary

Contracting is a powerful tool to achieve New York City’s goals and priorities – and the City has the power to use contracting strategically to make investments that support a vibrant, sustainable, and equitable City. One of the City’s responsibilities is to consider ways to more meaningfully direct portions of the City’s roughly $40 billion in annual contract spending to local businesses owned by women and people of color. Yet the City of New York has historically procured goods and services overwhelmingly from businesses owned by white men. While there are meaningful signs of effort, and some modest indications of progress, that pattern of historic discrimination largely continues: in Fiscal Year 2023 (“FY23”) only 5% of that $40 billion went to businesses owned by women and people of color.[1]

Over the past three decades, the City has developed a robust effort to support investments in Minority- and Women-owned Business Enterprises (“M/WBEs”). This Annual Report on M/WBE Procurement provides analyses to understand how effective the tools of this program are at actually moving the needle. These analyses measure “M/WBE utilization” in compliance with Local Law 174 (“LL 174”) of 2019, which established the City’s modern M/WBE program. LL 174 requires City agencies and elected offices to establish contracting goals to ensure that a designated percentage of their contracted funding is invested in M/WBEs.

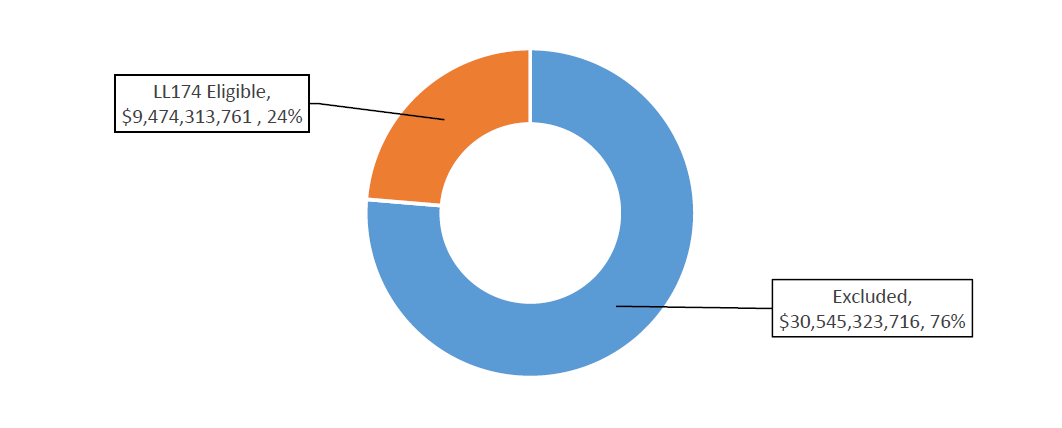

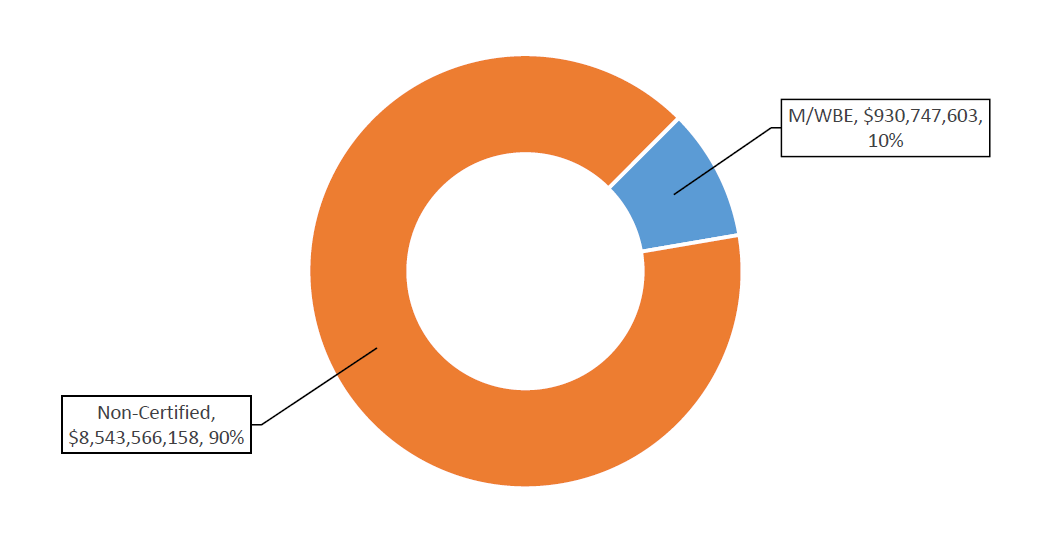

LL 174 only applies to a modest slice of the City’s procurements – only a quarter of the City’s total procurement portfolio is subject to the requirement to set and comply with M/WBE participation goals. But even here, the City is falling short of its mandated objective. M/WBEs are winning more contracts than in prior fiscal years, but less than 10% of the value of even the narrowed portfolio of contracts subject to LL 174 participation goals were registered to M/WBEs. And the “disparity with the disparity” remains. The value of contracts with Black, Hispanic, or women-of-color owned businesses each hover near 1%.

In addition to presenting detailed data on the City’s M/WBE procurement, this Report also evaluates the Administration’s efforts to move the needle. It finds meaningful effort, some progress on prior recommendations, and substantial areas for continued improvement. By shining a spotlight on M/WBE contracting, the Report aims to identify progress, confront shortcomings honestly, and make recommendations for much-needed improvement to help enable the City to deliver on its commitment for M/WBEs to receive their fair share of City contracting.

Current State

- M/WBEs continue to win only a small share of City contracts. M/WBEs accounted for only 5.3% of the value of all new City contracts and Purchase Orders (“POs”) registered in FY23, and just 9.8% of the narrower universe of City contracts and POs subject to M/WBE participation goals under LL 174. Similarly, M/WBEs received only 9.5% of the City’s total spending on prime contracts subject to LL 174 goals in FY23.[2]

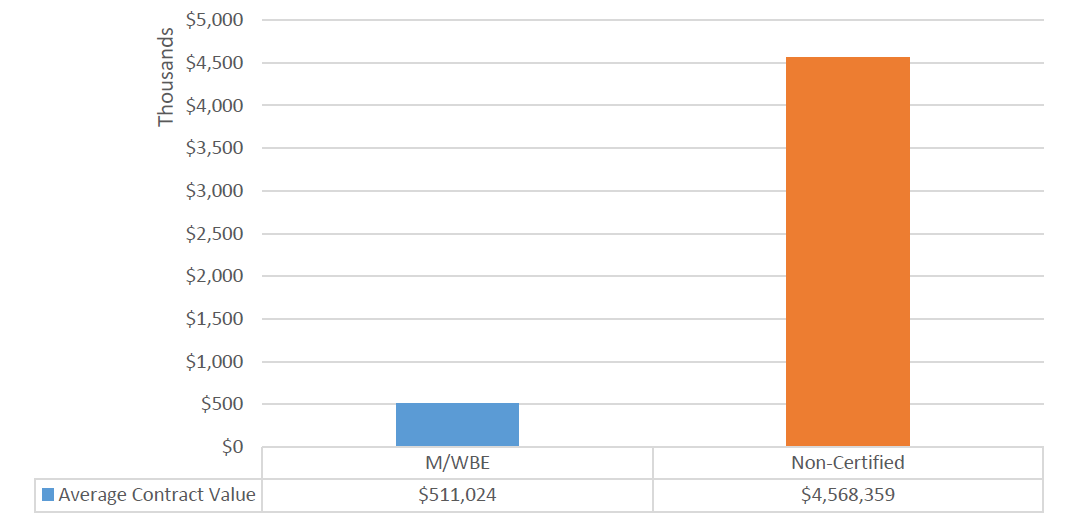

- M/WBEs are winning more contracts, but those contracts are, on average, for a small fraction of the value of the contracts won by firms owned by white men. Though M/WBEs accounted for 61.8% of the total number of new contract registrations and POs subject to LL 174 participation goals, these contracts only account for 9.8% of the total value. The average value of a new contract registered in FY23 to a Non-Certified firm was $4.6 million, over nine times larger than the average value of a new contract registered to a M/WBE, which was just $511,000.[3]

- The “disparity within the disparity” remains severe. The value of contracts with Black, Hispanic, or women-of-color owned businesses each hovers at just 1%.

- Only 1.16% of the value contracts and POs subject to LL 174 participation goals were registered to Black M/WBEs, and only 0.96% to Hispanic M/WBEs.

- Only a combined 1.03% of the value of contracts and POs subject to LL 174 participation goals were registered to businesses owned by women of color (and more than half of these were registered to businesses owned by Asian American women). Male-owned MBEs account for nearly 8 times the count of registered contracts and POs than women-owned MBEs.[4]

- Most M/WBEs don’t benefit from City contracting. In FY23, only about 20% of City-certified M/WBEs had a contract, PO, or approved subcontract registered by the City.[5]

- More than half of contracts awarded to M/WBEs are registered late. Approximately 61% of M/WBEs contracts registered in FY23 were retroactive. This is a particular challenge for smaller firms without sufficient working capital to endure long wait times for payment.

Findings

- Existing City tools don’t do enough to connect agencies and M/WBEs. There is no one centralized place to see planned procurement opportunities. City tools rely heavily on commodity codes that are ineffective in linking M/WBEs and agencies. In focus groups, M/WBES consistently reported this as a significant barrier.

- Agencies are not taking advantage of the increased M/WBE Noncompetitive Small Purchase method (“M/WBE NCSP method”) threshold. Despite the increases in this threshold, which was increased from $500,000 to $1 million during FY 23, and subsequently increased to $1.5 million, the average value of a contract registered using this method was merely $185,762.

- Master Agreements awarded to M/WBEs are not used anywhere near capacity. Despite both large volumes and values of master agreements registered to M/WBEs, they are less likely to be used than those registered to their Non-Certified counterparts and in many instances result in no usage at all.[6]

- Goal-setting oversight is insufficient for contract changes and modifications. As such, the City must ensure it is fully examining and taking advantage of ways to maximize getting dollars to M/WBEs, even beyond the initial contract award.

Recommendations

Recommendation #1: Streamline connections between M/WBEs and Agencies. The City must strengthen its tools to connect M/WBEs to contracting opportunities. The City should create one repository of current and planned procurement opportunities, standardize commodity code selection and searches across agencies procuring similar goods and services, and develop curated resources that simplify the ways to find procurement opportunities and eligible M/WBEs.

Recommendation #2: Assess effectiveness of certification by surveying underutilized firms. Surveys can help the City understand why the vast majority of certified M/WBEs do not do business with the City.

Recommendation #3: Strengthen goal-setting procedures, support, and oversight. The City must establish and enforce standardized expectations for setting goals and monitoring compliance for all eligible contracts, including for contract changes and modifications.

Recommendation #4: Increase utilization of M/WBEs in human services contracting. M/WBEs already offer essential human services, so the City should aim for higher contracting with M/WBEs in this sector. It must ensure that M/WBEs are not precluded from prime contracting opportunities and more effectively establish processes for M/WBE subcontracting across human services contracts.

Agency and Industry Highlights

In addition to providing analyses of the overall state of City procurement with M/WBEs, this Report provides a snapshot for each agency and examines M/WBEs participation by industry. Utilizing a new overall performance metric developed to account for difference among agencies, it examines the relative performance of agencies in doing LL 174-elgible business with M/WBEs as compared to their peers with similarly sized LL portfolios.[7] In FY23:

- Among agencies with large LL 174-eligible contracting portfolios, the Department of Environmental Protect (DEP) was ranked first and the Department of Transportation (DOT) was ranked last. The Office of Technology and Innovation (OTI) had the most relative improvement from FY22.

- Among agencies with moderate LL 174-eligible contracting portfolios, the Department of Homeless Services (DHS) was ranked first and the Department of Citywide Administrative Services (DCAS) was ranked last. DHS also had the most relative improvement from FY22.

- Among agencies with small LL 174-eligible contracting portfolios, the Law Department (LAW) was ranked first and the Department of Finance (DOF) was ranked last. LAW also had the most relative improvement from FY22.

- Among agencies with micro LL 174-eligible contracting portfolios, the Comptroller’s Office (COMP) was ranked first and the Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) was ranked last. The Business Integrity Commission (BIC) had the most relative improvement from FY22.

- The Office of Technology and Innovation (140 registrations), the Department of Transportation (101 registrations), and the Department of Sanitation (62 registrations) made the most frequent use of the M/WBE Noncompetitive Small Purchase method in FY23.

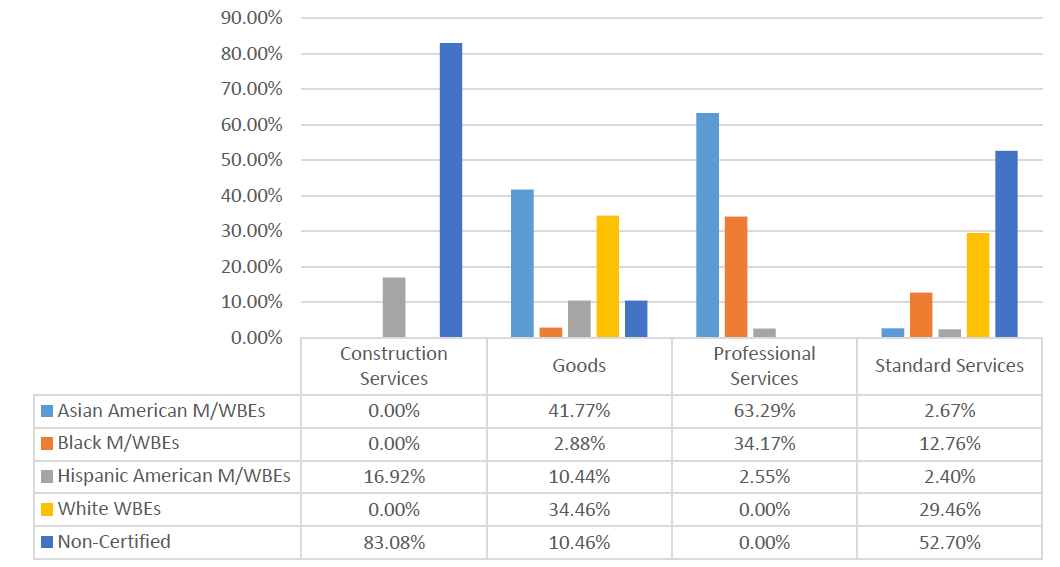

- The Department of Education (“DOE”) is a non-mayoral agency and previously was not subject to LL 174 participation goals. However, in FY23 DOE’s Procurement Policy and Procedures were amended to implement a M/WBE goals program consistent with LL 174. FY23 is the first fiscal year in which the procurement Rules were legally effective. M/WBEs accounted for 8.92% of DOE prime contract and PO registrations subject to participation goals.[8]

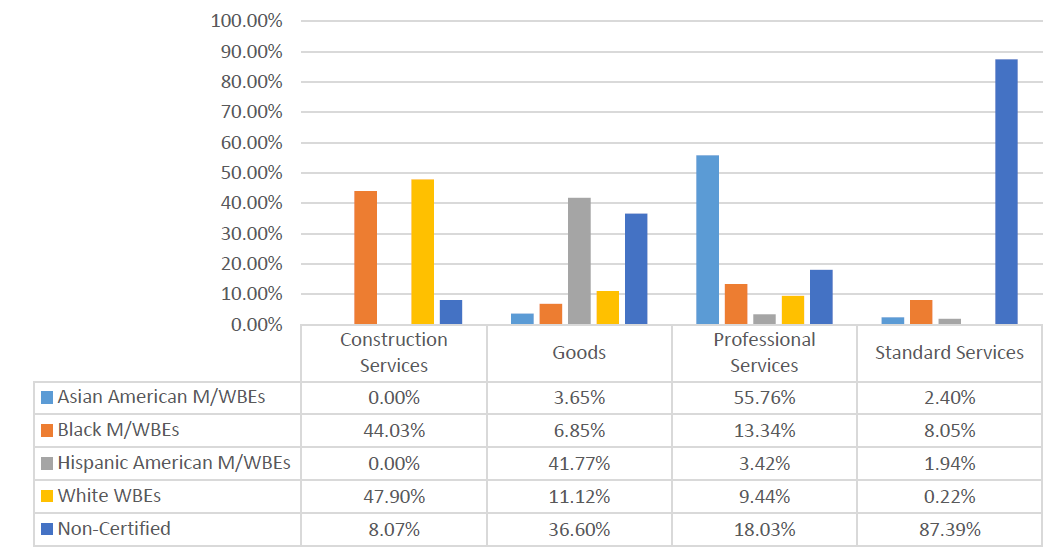

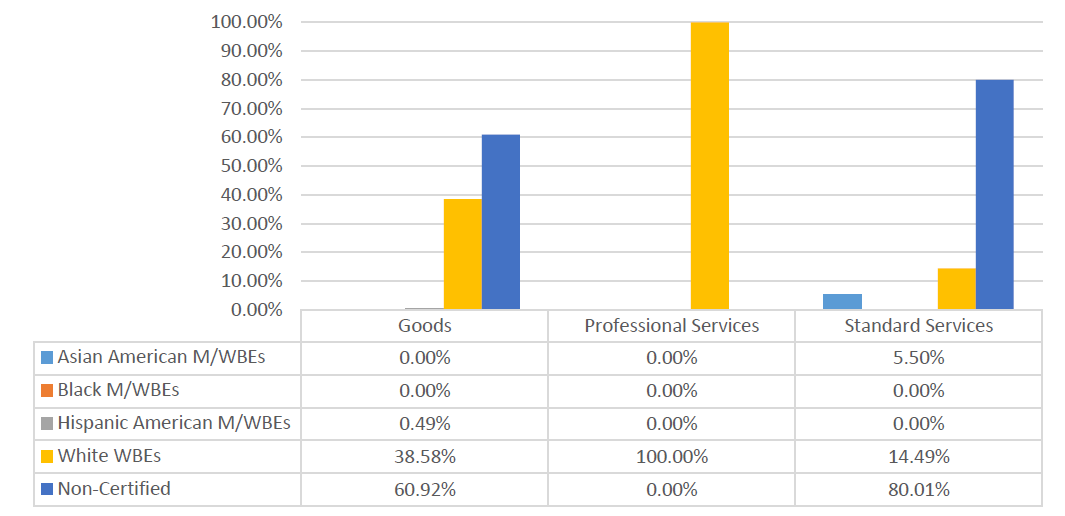

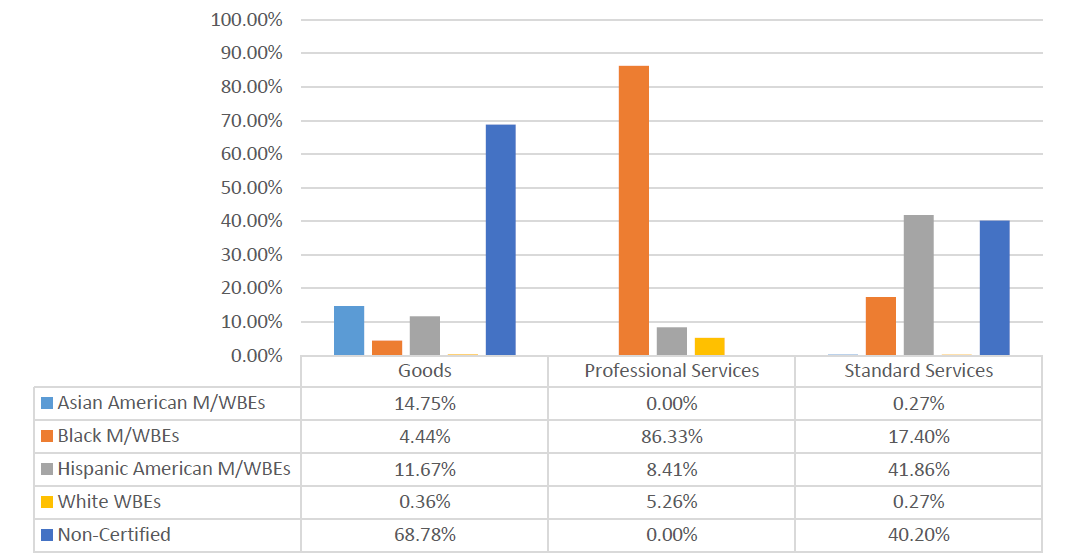

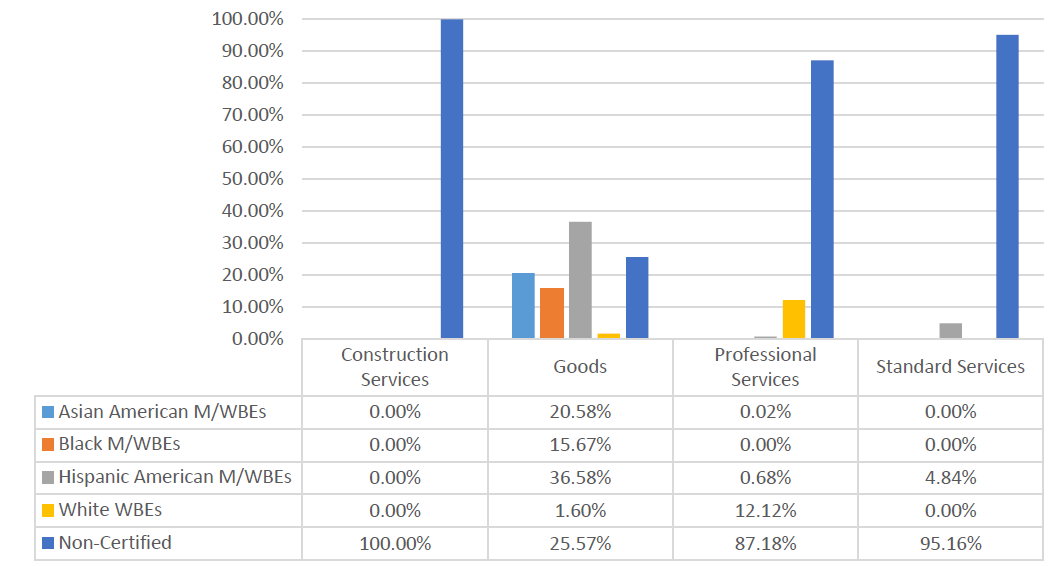

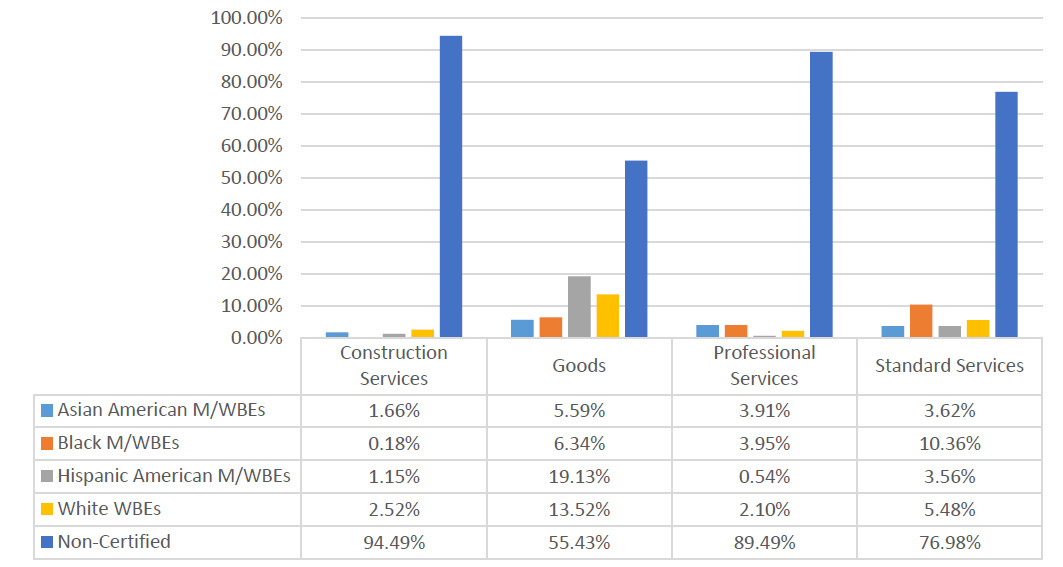

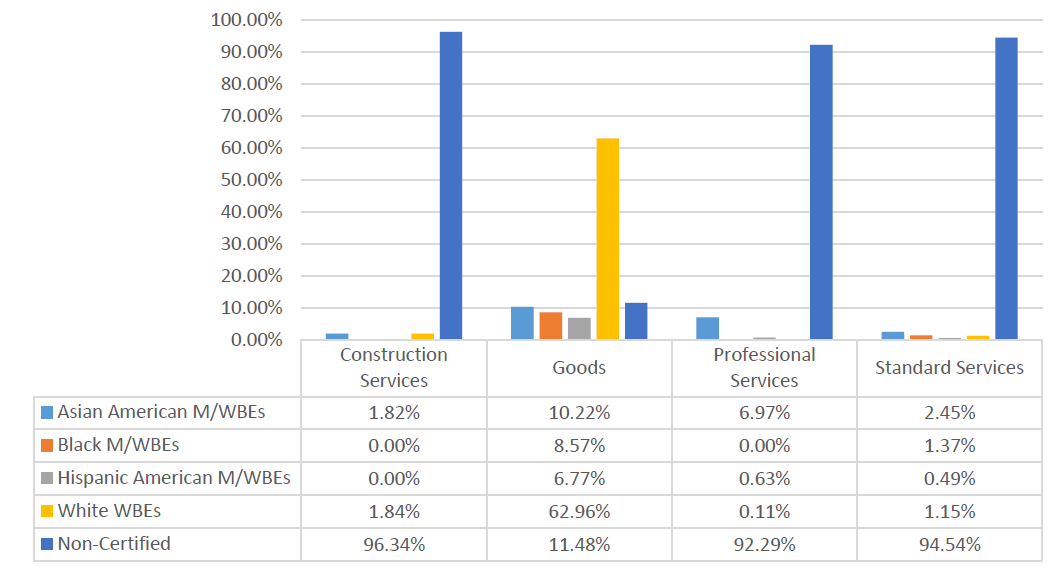

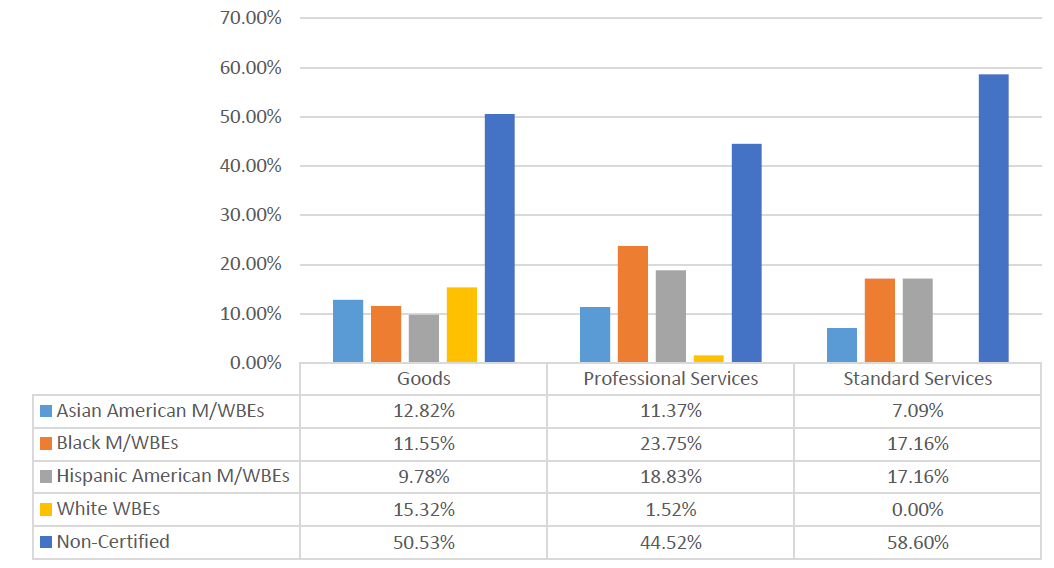

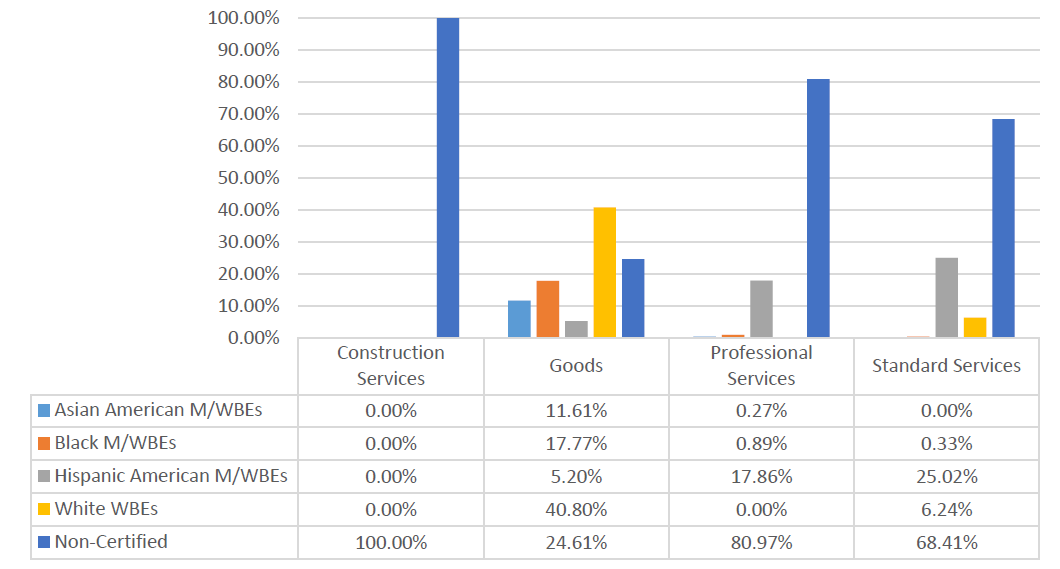

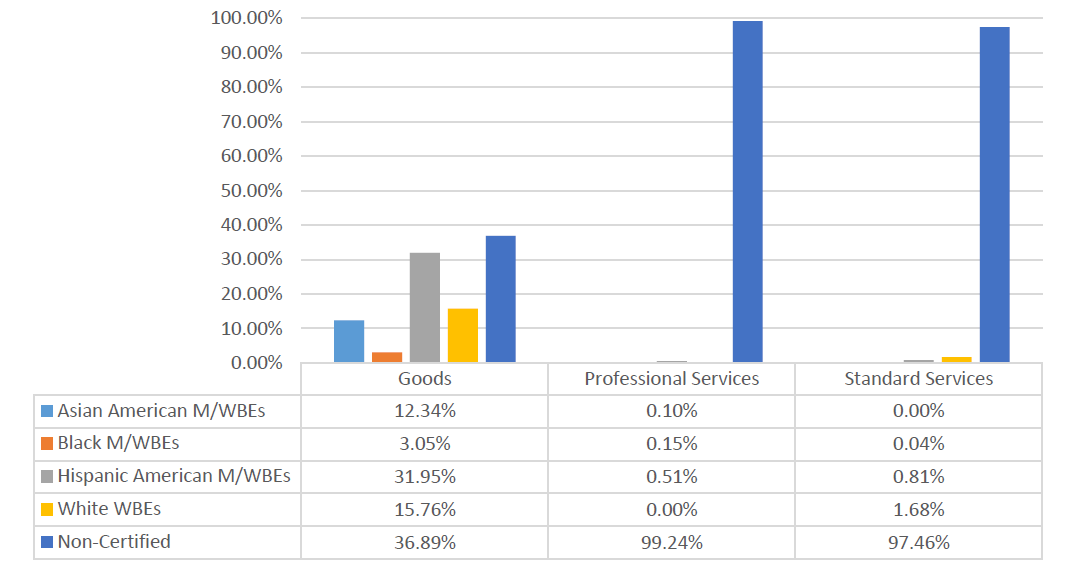

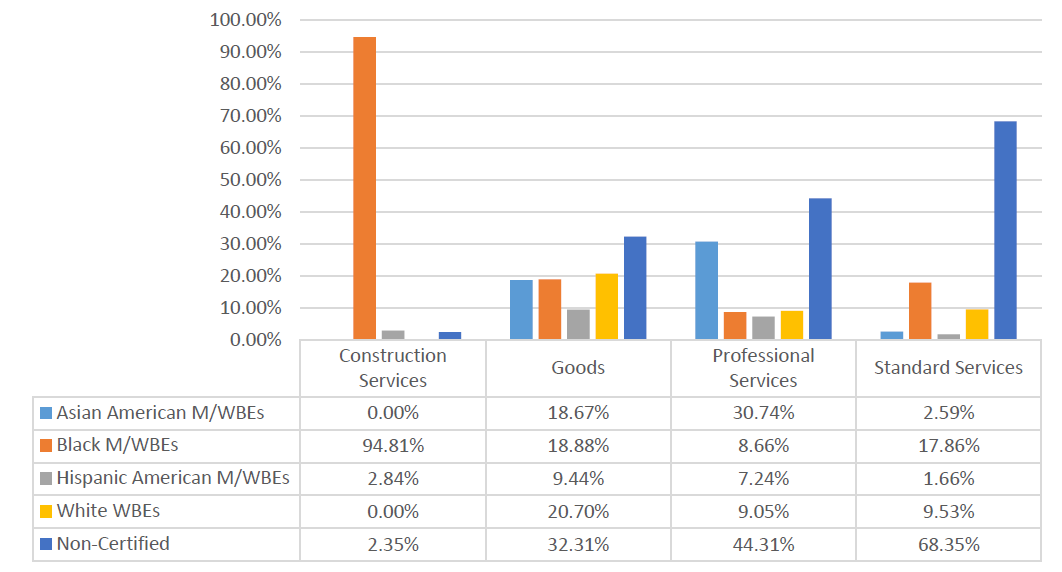

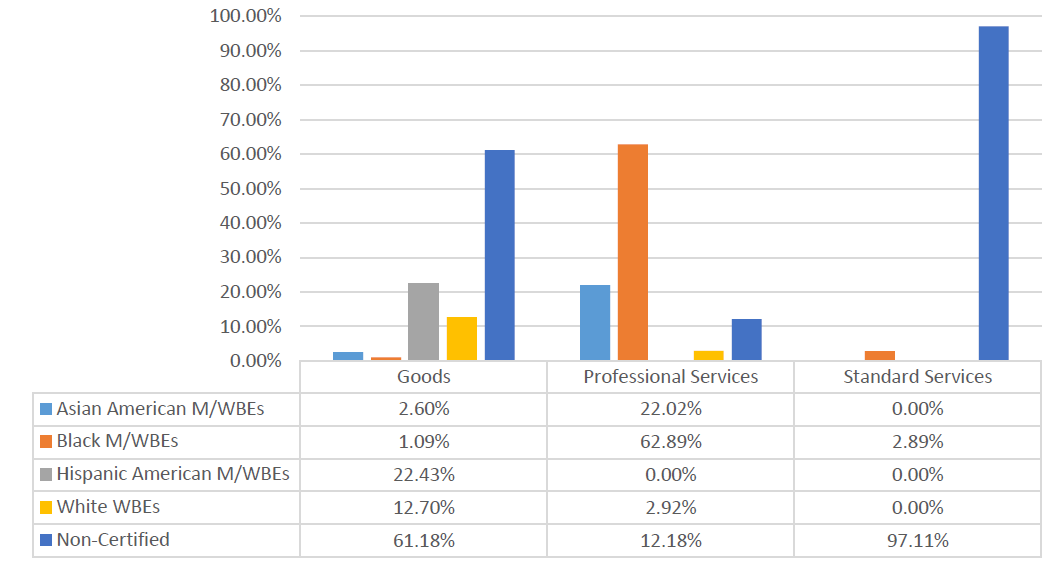

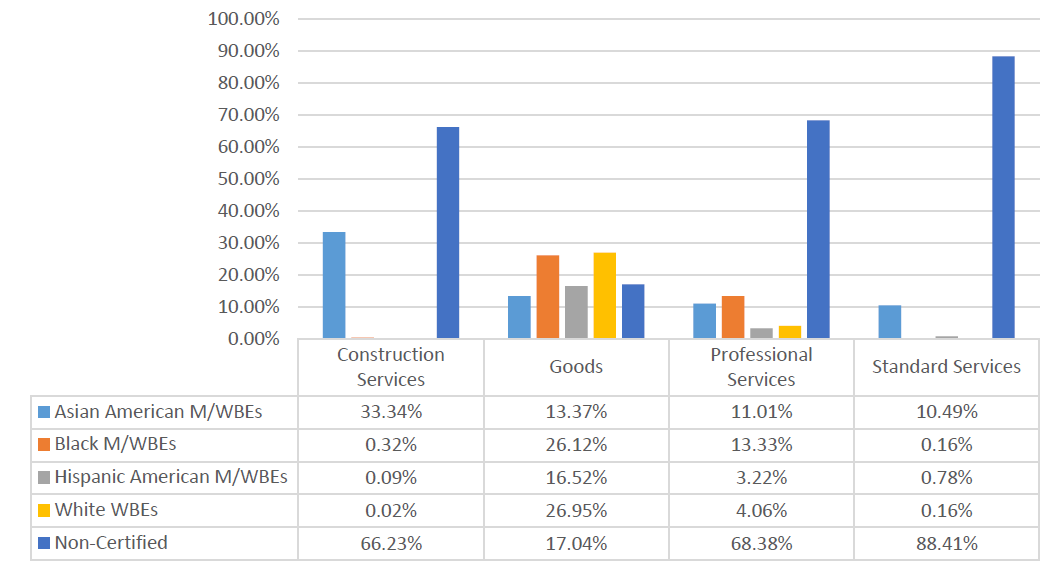

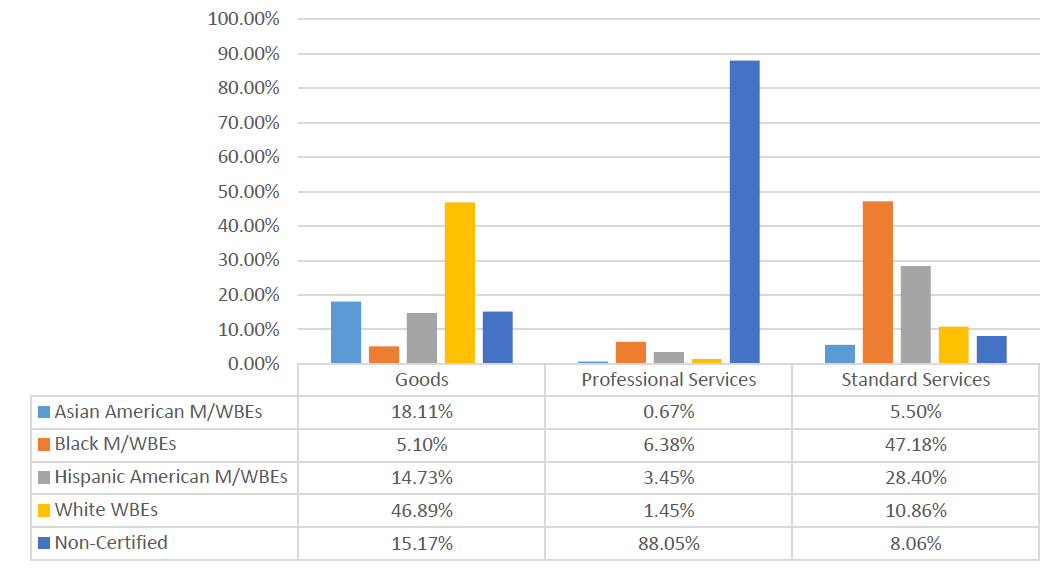

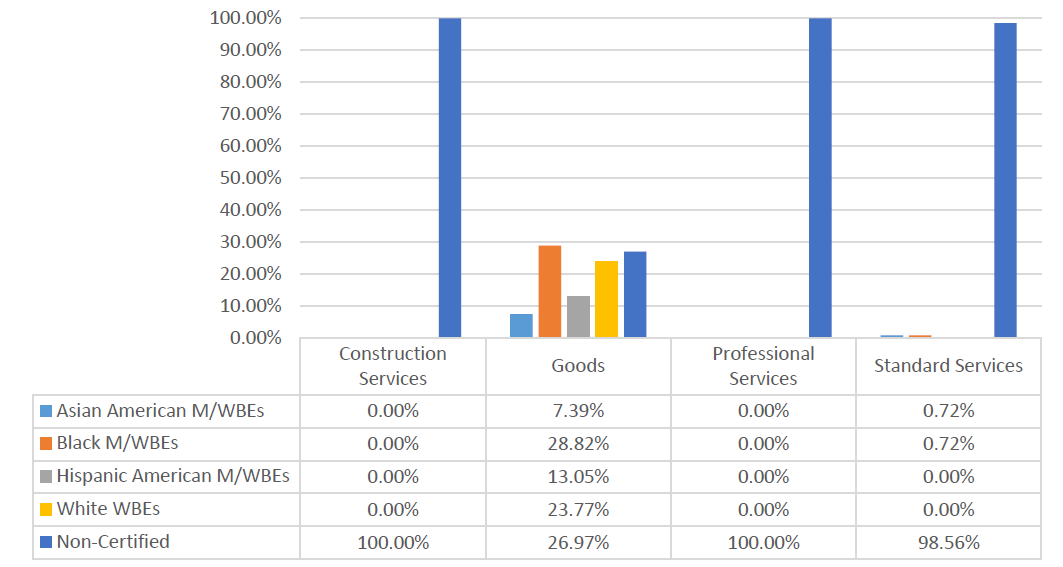

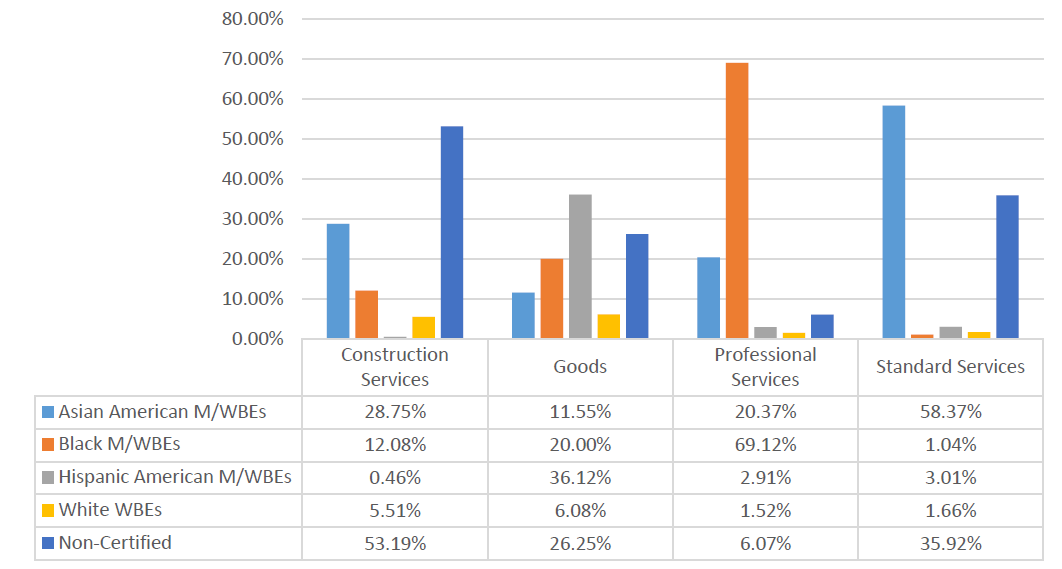

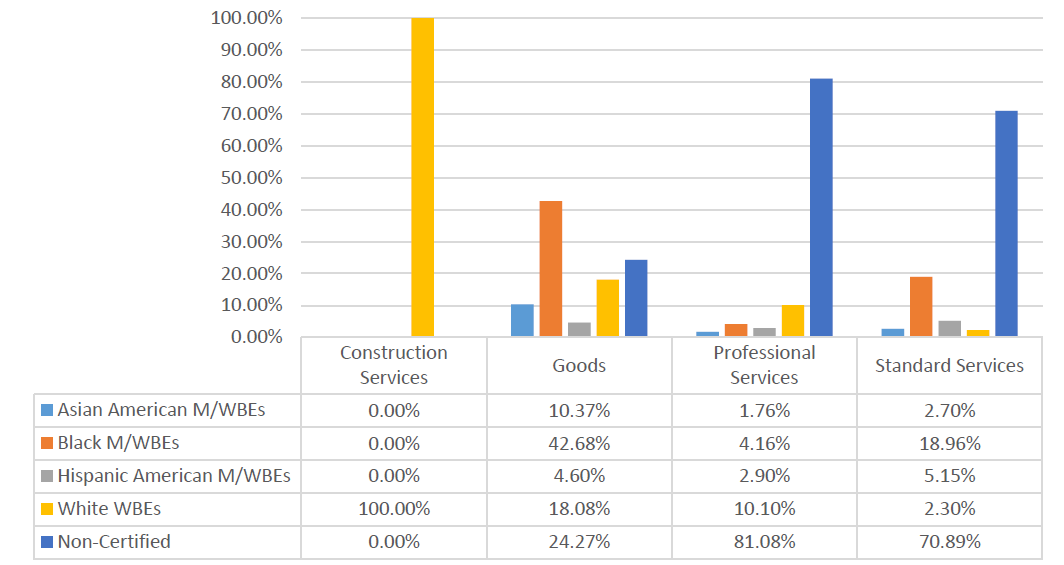

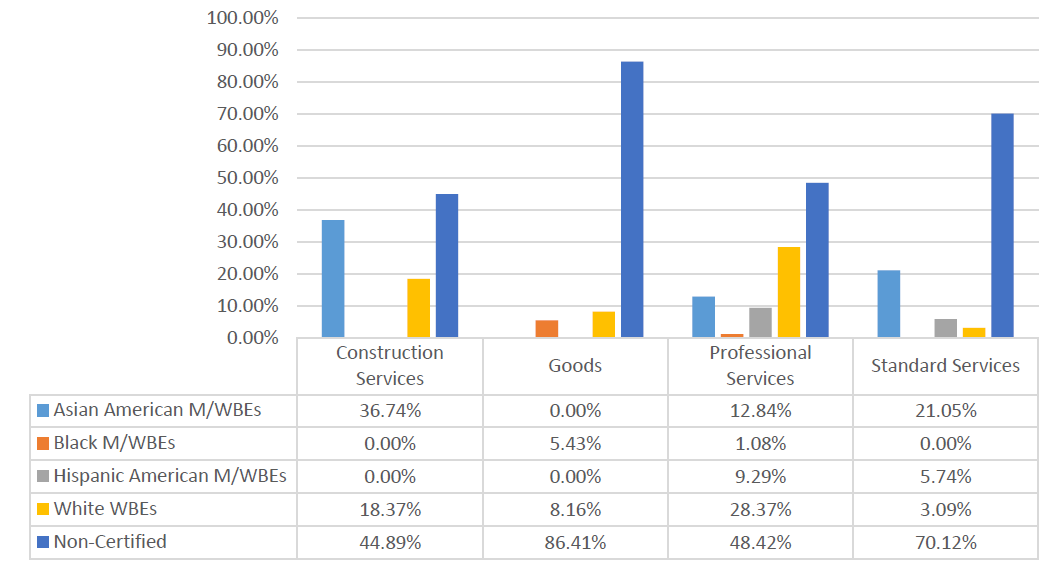

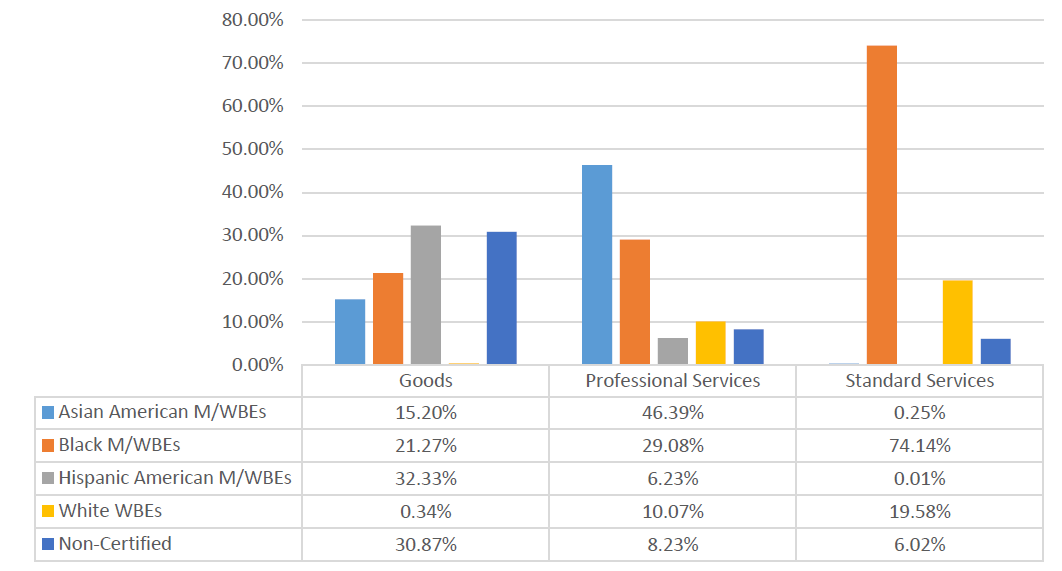

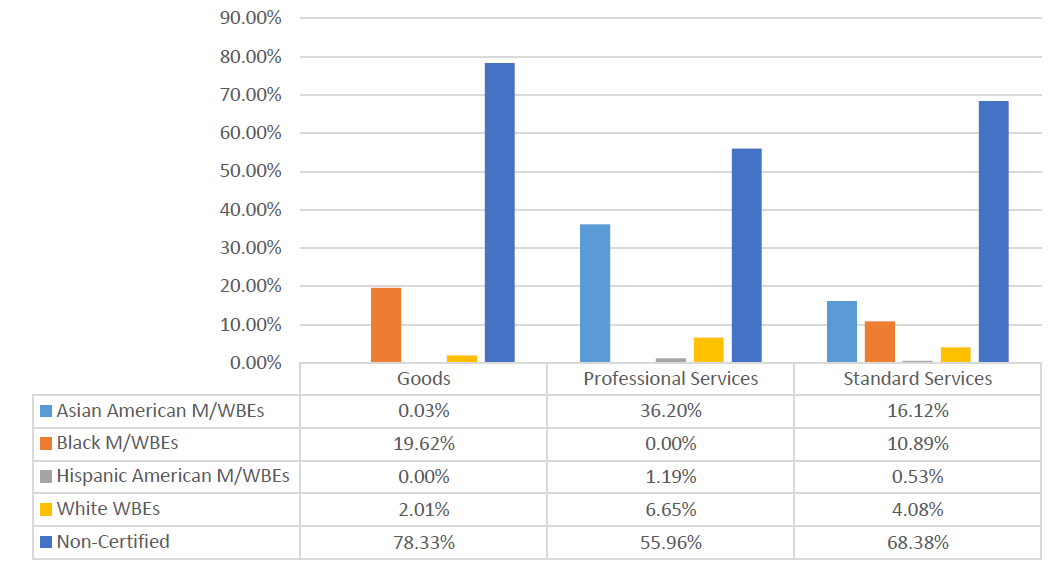

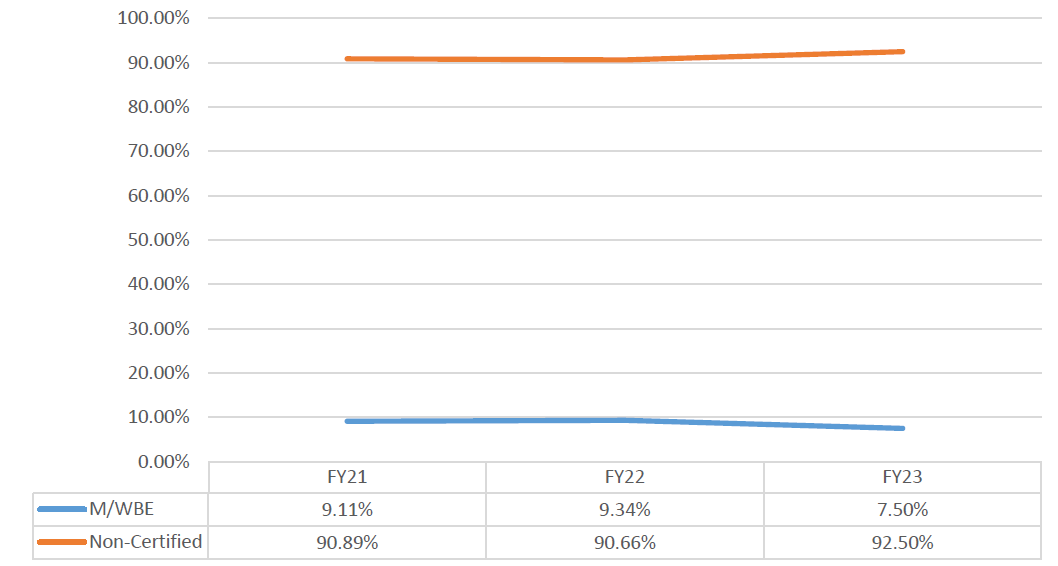

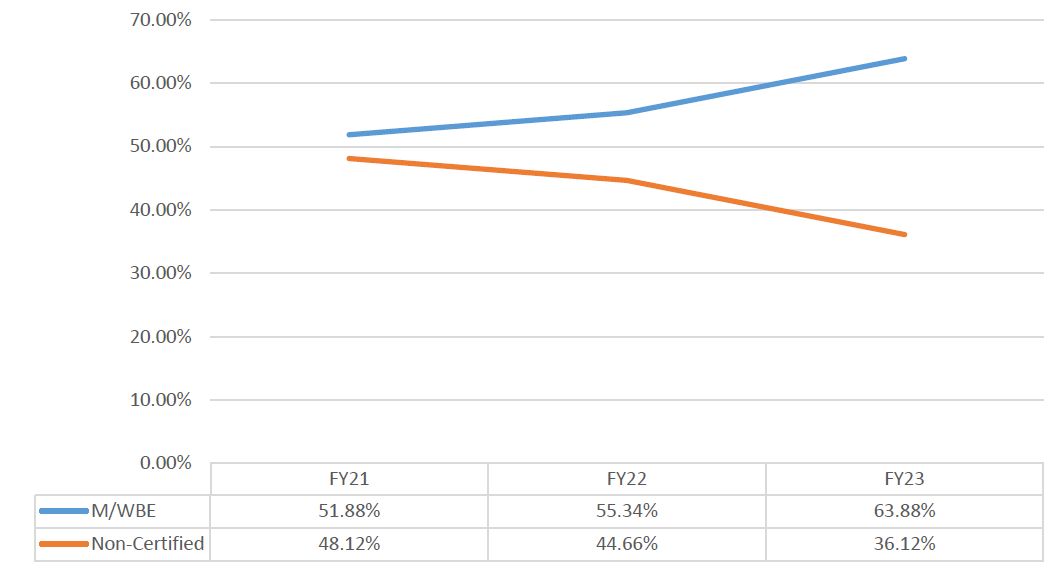

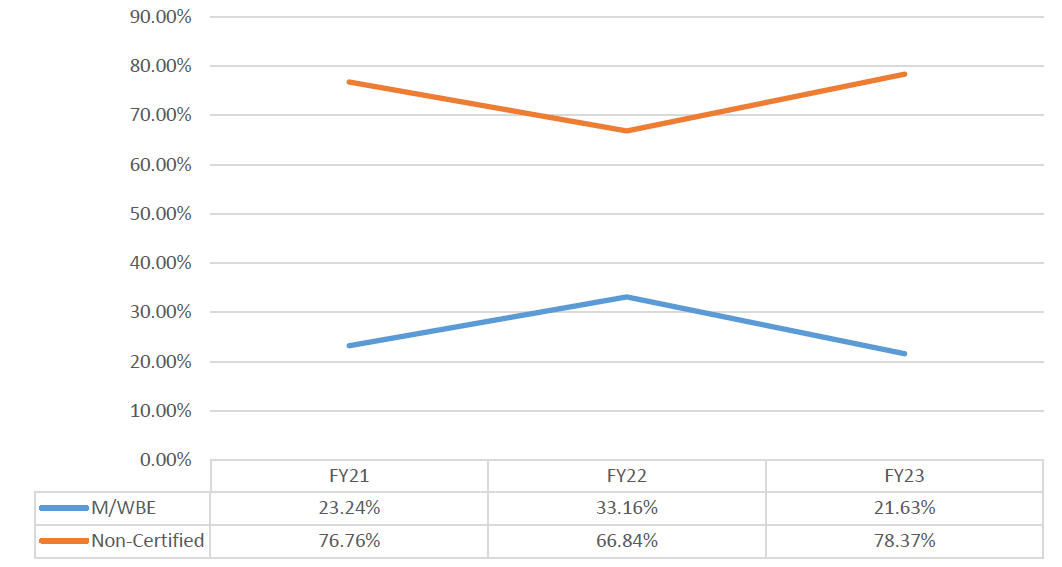

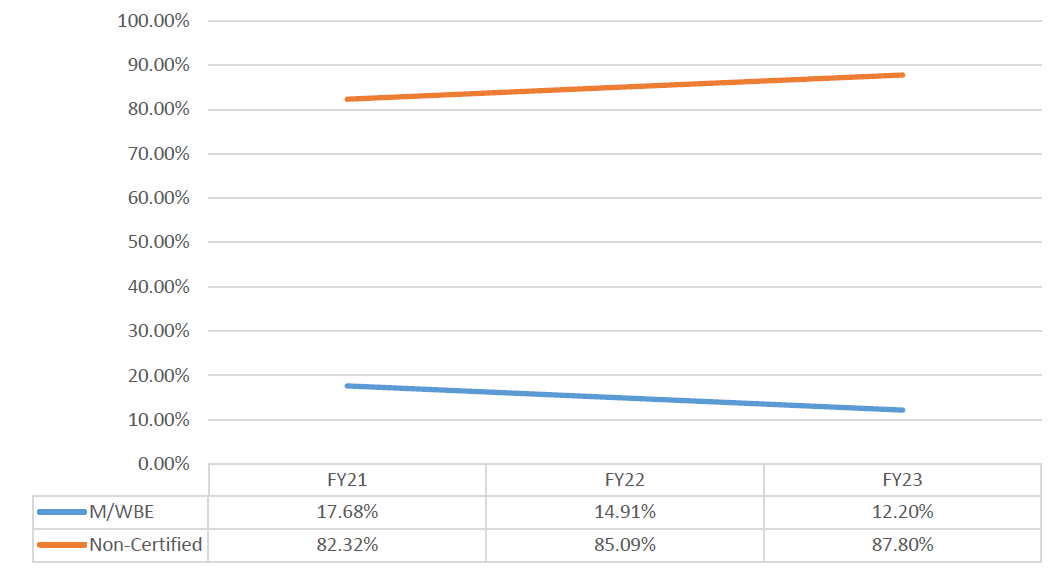

- Contracts for construction services (7.5%) and standard services (12.2%) had lower M/WBE utilization rates than those for goods (63.6%) and professional services (21.63%).

Approach

This Annual Report provides a comprehensive review of the Fiscal Year 2023 (“FY23”) data of prime contracts registered by New York City agencies with this Office to examine if and when M/WBEs are awarded contracts, analyzing by procurement method, dollar value, and industry. Reviewing these indicators shines light on the procedural roadblocks that perpetuate inequities in how the City contracts with M/WBEs.

In preparing for this Report, the Comptroller’s Office held a series of M/WBE Round Tables in each borough to gather stakeholder feedback from small and large M/WBEs across several sectors and industries. The feedback from these M/WBEs informed the findings and recommendations included in this Report. Direct testimonies from the participants of these sessions can be heard in the video, M/WBE Firsthand Stories, found at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V_VdrqwJDHA.

Data

All data for this report was extracted from the City’s Financial Management System (FMS) during the summer and autumn of 2023.[9] This Report largely measures M/WBE utilization in alignment with the requirements codified in LL 174 and Section 6-129 of the New York City Administrative Code (“Administrative Code”). The requirements are applicable only for eligible contracts, which are defined in the “M/WBE Program Overview” section of this Report. Therefore, this data set is limited to the City’s utilization of City-certified vendors and does not report on the utilization of vendors certified by the State as MWBEs or as Disadvantaged Business Enterprises (“DBE”), which may be requirements tied to non-City funding sources.[10] Additionally, this Report excludes data related to the registered Renewals, given that, by definition, these are re-registrations of existing contacts that have been reported on in prior years and are not reflective of new efforts to contract for these goods or services.

Compliance with the requirements of the M/WBE Program can be achieved at both prime and subcontracting levels. However, given that the City does not have the tools to properly track and report on subcontractors, as discussed extensively in last year’s report, the ability to measure compliance with M/WBE participation goals met by subcontracts is limited. Therefore, unless otherwise stated, this Report primarily focuses on analyzing prime contract data.

City procurement systems are limited and do not include the necessary data to confirm if a contract is funded by State or Federal funds. Due to these limitations, LL 174-eligible data in this Report includes some contracts that may actually be excluded from LL 174.

Unless specified, this Report does not include data related to contracts issued by some non-mayoral entities (including at the time of this report the Department of Education, the Economic Development Corporation, NYC Health + Hospitals, and the New York City Housing Authority).[11] In an effort to share information on the use of City dollars more generally, in some circumstances data is included for contracting agencies and procurement actions not covered by LL 174. The report will specify whether analyses pertain to contracts subject to LL 174 participation goals or more generally to other specified data sets. A full list of excluded considerations is included in Appendix C of this Report.

M/WBE Program Overview

The City’s M/WBE program was developed to expand opportunities for minority and women entrepreneurs to access government contracts and grow their businesses. It is currently governed by Section 6-129(b) of the Admin Code, which codifies Local Laws 174 and 176 enacted by the City Council in 2019. This Report often focuses on procurements “subject to LL 174 participation goals”, for which city agencies have a legally mandated responsibility to meet specified M/WBE participation goals. These goals can be met by awarding a prime contract to a M/WBE, or by requiring a Non-Certified prime vendor to subcontract a specified percent of the contract value to M/WBEs. When used effectively, participation goals ensure maximum M/WBE utilization even in circumstances where the chosen procurement method does not result in a contract award to a M/WBE prime.

M/WBE Certification

The Department of Small Business Services (“SBS”) is responsible for certifying that vendors meet the criteria to be designated as a New York City M/WBE (“City-certified”)[12]. Businesses owned by people of color and women are required to be City-certified by SBS in order to be eligible to qualify for procurement opportunities exclusively targeted to M/WBEs such as those via the M/WBE NCSP method[13]. Similarly, agencies may only avail themselves of M/WBE-targeted nimble tools and receive credit towards participation goals when contracting with City-certified M/WBEs. As discussed throughout this report, Certification is a significant first step that M/WBEs take towards their City contracting journey. Unfortunately, throughout the M/WBE Round Tables, M/WBEs expressed frustration at the length and complicated nature of the process[14].

Businesses that want to certify as M/WBEs with other municipalities to either further expand their contracting portfolio or to be eligible for non-City funding opportunities are also required to also be independently certified as a M/WBE with those entities. Given that certification reciprocity does not exist among local public contracting entities, including New York State, Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, and the New York City School Construction Authority, vendors experience the burdens of these time-consuming and mostly duplicative processes many times over. As a member of the Capital Process Reform Task Force, this Office supported the proposal for State Legislation that established certification reciprocity between New York City and New York State. Although the legislation passed in both the State House and Assembly during the 2023-2024 legislative session, the legislation was ultimately vetoed by the Governor in December 2023[15]. This Office remains in support of certification reciprocity and looks forward to its successful passage during the upcoming legislative session.

Procurements Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals

Agencies are required to ensure that M/WBE participation goals are met for all eligible procurements in the following industries[16]:

- Professional services: the provision of various kinds of expert advice and consulting, including legal services, medical services, and information technology and construction-related consulting services

- Standard services: services other than professional services and human services such as custodial services, security guard services, stenography services and office machine repair

- Construction services: dealing in the planning, design, or construction of real property or other public improvements

- Goods (valued up to $1 million): all personal property, including but not limited to equipment, materials, printing, and insurance, excluding land or a permanent interest in land

These goals include specific contracting participation goals for each individual M/WBE category: “Black Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, Women, and Emerging”. While LL 174 permits agencies to set an “unspecified goal,” which a vendor may meet by using an M/WBE regardless of certification category, when setting participation goals, agencies are required to consider the potential for the purchase to provide opportunities for specific categories of M/WBEs to develop greater capacity and to increase competition for city procurements.[17]

Specified Exclusions

In some specified circumstances, agencies are exempt from establishing M/WBE participation goals for contracts procured through the following methods. As a result of these exclusions, less than 25% of total City procurement value for FY23 was subject to LL 174 M/WBE participation goals.[18]

Chart 1: FY23 Value of Contracts and PO Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals

Excluded procurement categories include:

- Human services procurements: in FY23, the $15.8 billion in contract and PO value under the human services industry accounted for nearly 40% of all procurements.

- Any procurement that results in an award to a not-for-profit entity: Contracts and POs registered to not-for-profit entities totaled over $15.14 billion in FY23, accounting for 37.85% of all procurement value.[19]

- Sole source contracts: the $3.4 billion in Sole Source contract and PO value registered in FY23 represents 8.5% of all procurement value in the fiscal year.

- Government-to-Government procurements: Totaling $1.9 billion in contracts and POs in FY23, this method accounted for nearly 5% of all FY23 procurement value.

- Emergency procurements: Totaling $1.1 billion in contracts and POs in FY23, this method accounted for nearly 3% of all FY23 procurement value.

- Intergovernmental procurements (NY State Office of General Services (OGS)/U.S. General Services Administration (GSA)): Totaling $1.4 billion in contracts and POs in FY23, this method accounted for 3.5% of all FY23 procurement value.

- Contracts subject to federal or state funding requirements that preclude the City from imposing M/WBE participation goals or impose their own Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE), MBE, or WBE goals.[20]

- Any procurement that is not competitively awarded (i.e., Required Authorized Sources, etc.)

Exemption for human services contracts is particularly significant, as human services contracts made up the largest share by both volume of contracts and contract value in FY23. Many of these contracts include substantial subcontracting to for-profit firms, which could be subject to M/WBE participation goals. Later sections of this Report detail the impact of excluding nearly half of the City’s procurement portfolio from M/WBE participation goals and offers recommendations to increase utilization in this critical sector.

This Office released “Rethinking Emergency Procurements”[21] on November 30, 2023, which included a focused analysis on M/WBE utilization in emergency procurements. M/WBEs were awarded just 15% of the count of contracts included in the Report’s lookback period, amounting to only 3.5% of the total emergency procurement value.

Additional context and information about the City’s M/WBE participation goals program and governing legislation can be found in Appendix A of this Report.

Assessing the City’s Progress on FY22 Recommendations

While there is no magic wand solution to the decades of systemic racism that continue to perpetuate in NYC’s contracting practices, there are real, tangible steps the City can take to address some of the biggest problems contributing to the inequity. Last year’s FY22 Annual Report on M/WBE Procurement set forth a series of recommendations for procedural updates, systematic enhancements, and legislative reforms. While the City has made progress in some of these areas, much work remains.

This FY23 Report includes updates on key performance indicators presented in last year’s Report as well as an assessment of the City’s progress towards implementing the FY22 recommendations. This Report also includes some additional, focused analyses and offers additional recommendations developed to move the contracting needle in a manner that results in more impactful M/WBE utilization. Taken together, these steps will address some of the key underlying problems that prevent the City from increasing its contracting portfolio with M/WBEs.

| FY22 Report Recommendation | Progress | |

| 1. Ensure that M/WBEs have access to higher value contracts through competitive procurements | 1.1 Establish more PQLs | In progress |

| 1.2 Utilize “Best Value” preferences | In progress | |

| 2. Bolster agencies’ use of existing discretionary procurement methods | 2.1 Achieve broader and higher dollar use of the M/WBE NCSP method | In progress |

| 2.2 Raise the M/WBE NCSP method threshold to $1.5 million | Complete | |

| 2.3 Ensure that discretionary micropurchases and small purchases are more fairly distributed to M/WBEs | In progress | |

| 3. Reform the subcontracting process and incorporate it into PASSPort | No progress | |

| 4. Provide stronger tools to City agencies | 4.1 Update the training and guidance that agencies receive to reflect changes in procurement methods, markets, City goals, and best practices | In progress |

| 4.2 Make data relevant to M/WBE procurement more easily accessible across City data tools and contracting systems | In progress | |

| 4.3 Validate commodity codes so agencies can find the right M/WBEs | No progress | |

| 5. Improve the timeliness of City M/WBE contract registration | No progress | |

Projects Completed

One recommendation from the FY22 Report is complete. Following advocacy by the Mayor’s Office, the Capital Process Reform Task Force (in which the Comptroller’s Office is a participant), and stakeholders, the State Legislature passed and the Governor signed S.7563, which increases the threshold for eligible procurements from M/WBEs from $1 million to $1.5 million. Due to proactive measures by the Procurement Policy Board (“PPB”), which includes representatives appointed by the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services and the Comptroller’s Office, the City was able to quickly operationalize and implement this threshold change. This increased threshold for the M/WBE Noncompetitive Small Purchase method (“M/WBE NCSP method”) offers an avenue for M/WBEs to more effectively compete for larger contracts. This Report offers an assessment of the effectiveness of the City’s use of the procurement method at the thresholds in existence during the reporting period.

The 2023-2024 legislative session yielded more wins that stem out of the work of the Capital Process Task Force. The Task Force was successful in securing legislative approval of Bill S7526 that allows for an expansion of the City’s construction mentorship program to all City agencies.[22] Mentorship has long proven to be a key tool to develop small M/WBEs and support their growth to undertake larger projects and prime contracts. The NYC School Construction Authority has run a successful program for many decades and the State authority was recently granted to DDC during the 2019 session. The DDC mentorship program, although in early stages, is similarly showing the promise of success. The newest legislation will now allow for all NYC construction contracting agencies to establish pathways that provide M/WBEs training, networking, and bidding opportunities to support and increase business opportunities. Additionally, Bill S7385 allows agencies to use Owner-Controller Insurance Programs (OCIP) and Contractor-Controlled Insurance Programs (CCIP).[23] This new way of securing insurance will create greater access to projects for M/WBEs and small contractors by removing the hurdle of prohibitively high insurance costs that have historically prevented M/WBEs from successfully bidding on City projects.

Work In Progress

City agencies have made some progress across many of the other recommendations set forth in last year’s Report, but significant work remains.

In Fiscal Year 2023, the City established 6 new M/WBE-specific Pre-Qualified Lists (“PQLs”). Since then, two agencies released opportunities for M/WBEs to qualify for inclusion on 10 PQLs. This Office will continue to monitor the number of approved M/WBEs in established PQLs and track the City’s issuance of solicitations and contract awards using PQLs to determine if these efforts are effective in increasing M/WBE utilization.

The Mayor’s Office of Contract Services (“MOCS”) issued guidance and training on “best value” in 2023. Analyses in this Report show that 90% of contracts registered via competitive sealed proposal method (CSP) were registered to Non-Certified firms. Better enforcement and utilization of “best value” point or price preferences for competitive procurements remains a critically important priority for the City to address.

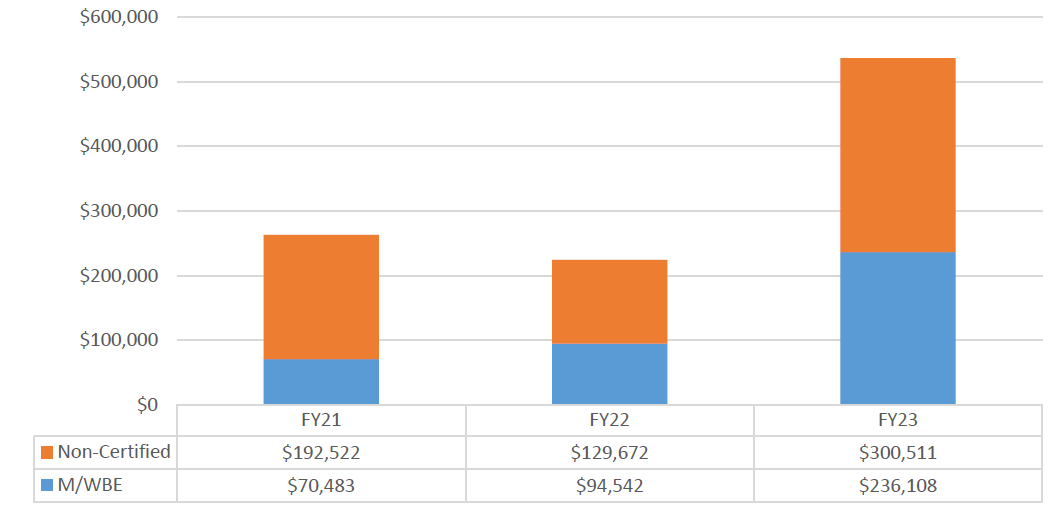

This Report includes a specialized focus on the M/WBE NCSP method in Finding #2. Agencies utilized this method more frequently in FY23, but the average value of a contract registered using this method was only $185,762 – far below the maximum threshold of $500,000 (and up to $1 million at some points in the year). This Office will continue to monitor the use of this method to ensure that agencies are maximizing the State-authorized threshold and utilize it to direct higher dollar value opportunities to M/WBEs.

In FY23 the relative share of the value of small purchases registered to M/WBEs (26%) increased from the prior fiscal year (14%). The share of micropurchases (18%) registered to M/WBEs did not increase from FY22 (17.9%).

This Office has been closely working with the Department of Small Business Services (“SBS”) on integrating key City systems that will streamline M/WBE procurement data. Through these efforts, M/WBE Vendor Profiles are expected to be updated in the SBS Directory to include a link to Checkbook NYC that provides real-time registration and spend data that more accurately reflects the vendor’s contracting capacity. This integration is anticipated to launch in February 2024, and offers agencies up-to-date information to support vendor market research and capacity that are key when targeting vendors for prime contracting opportunities and establishing aggressive and realistic subcontracting goals. Later sections of this Report discuss additional system enhancements that remain unaddressed.

Work Not Started

There are several essential Recommendations in last year’s Report that the City has not begun to address. The City has not effectively validated commodity codes or released any updated guidance to support M/WBE goal-setting, both of which are key to supporting agencies and M/WBEs to connect on contracting opportunities.

As discussed in last year’s Report, as well as emphasized in the Rethinking Emergency Procurements Report[24], reforming the City’s subcontracting process is critical for M/WBE participation as well as to hold the city accountable for vendor integrity and transparency measures. MOCS has announced a planned enhancement to PASSPort to “streamline subcontractor approval and subcontractor payment submission processes”, anticipated to be released in Spring of 2024.

This Report includes a focused section on retroactivity rates for M/WBEs, which have not improved since FY22 (In FY23, 61% of new M/WBE contracts were registered after their contract start date, compared to 55% in FY22). M/WBEs to continue to advance funding, borrow to cover those advances, adjust or delay work, and in some cases provide City services without any guarantee of pay.

Current State

This Annual Report presents data on City procurements that is essential to evaluating efforts to achieve measurable progress in increasing M/WBE utilization. As mentioned in last year’s Report, to better understand the current state of utilization, this Report analyzes trends and progress across 5 key areas of the City’s contracting portfolio:

- The share of contract registration value that was registered to M/WBEs[25]

- The average value of contracts registered to M/WBEs, in comparison to the average value of contracts registered to firms owned by white men

- A disaggregated analysis of key indicators to understand the disparate impacts across racial and gender categories

- The number of unique M/WBEs that do business with the City

- The retroactivity of contract registration for M/WBEs

Taken together, these areas of analysis can demonstrate a more comprehensive understanding of the current state of the City’s utilization of M/WBEs.

It is important to note that the impacts of some newly implemented policies and systems may take some time before they begin to demonstrate measurable value. That said, this Report’s analyses demonstrate that the City and its agencies are still falling short of goals to contract with diverse businesses.

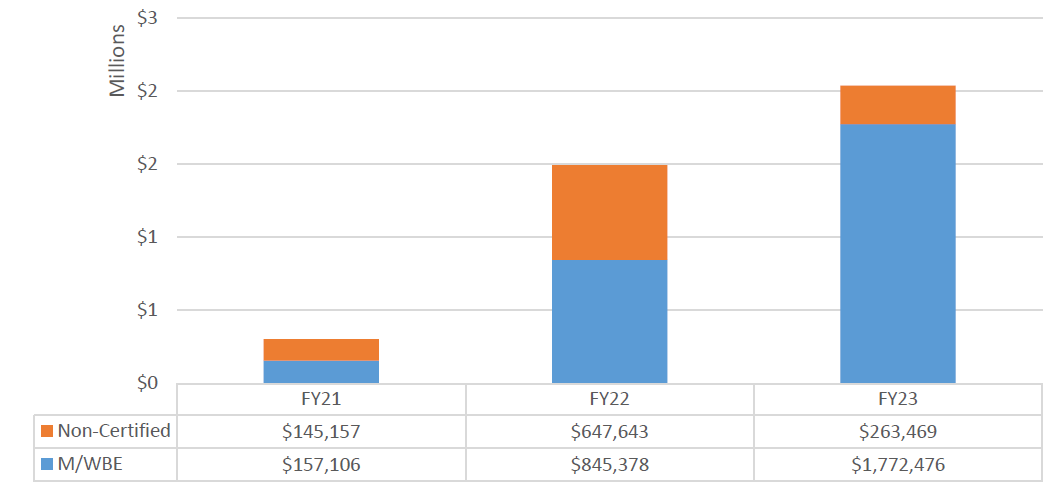

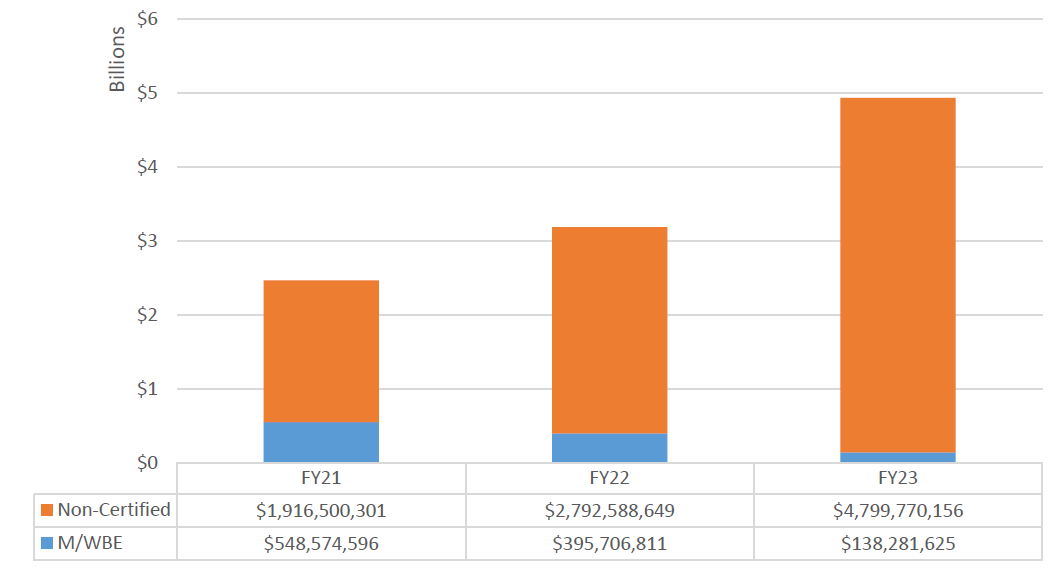

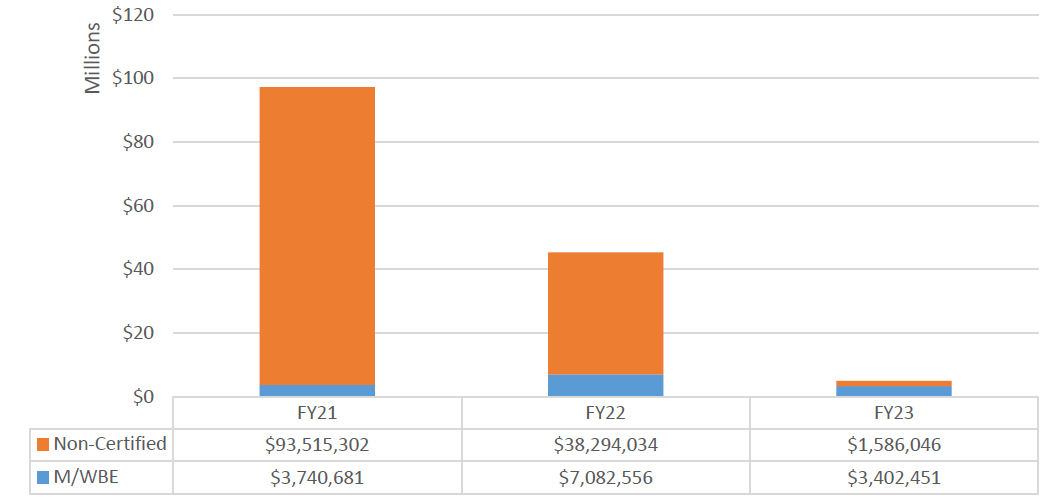

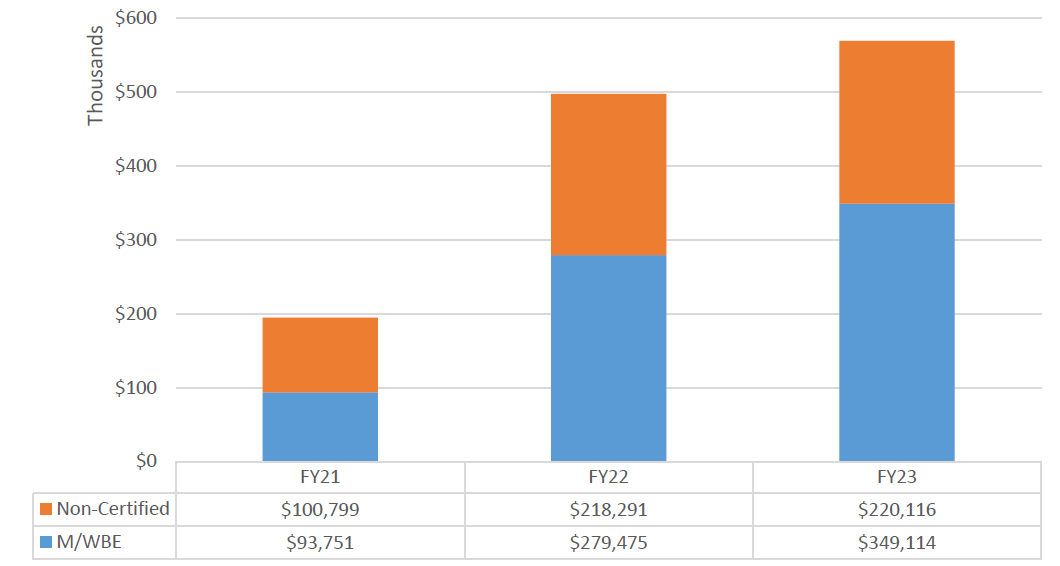

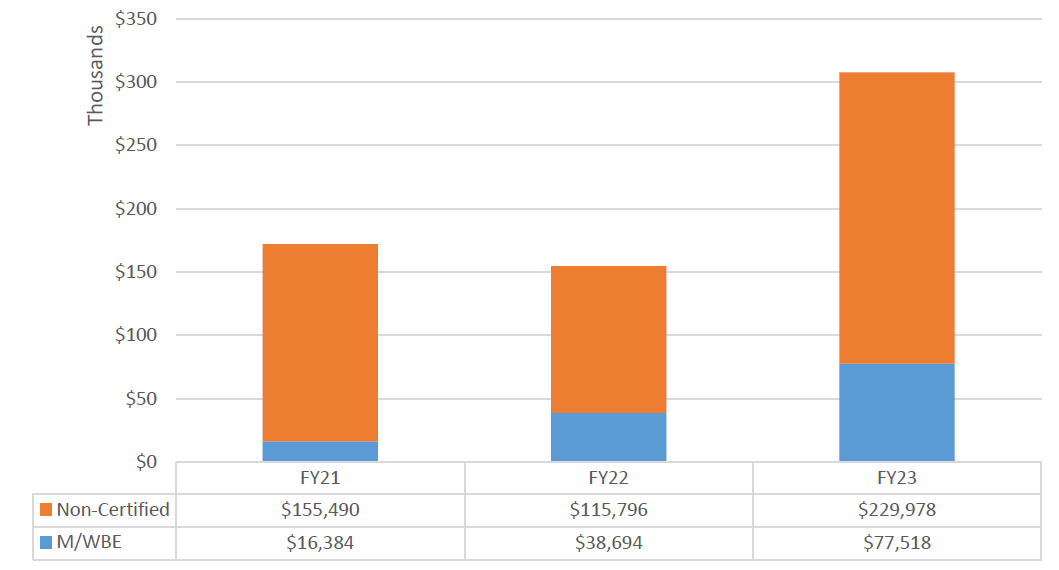

M/WBEs only won 5% of the value of City contracts

In FY23, the City registered 147,196 new prime contracts and POs valued at over $40,019,637,477. This includes many areas of contracting that are not subject to LL 174 participation goals as outlined in the “M/WBE Program Overview” section of this Report, including human services contracts (which account for approximately 40% of the registered contract value citywide). Across all City contracts and POs, 27,070 were registered to M/WBEs, representing 5.33% of the value and 18.39% of the volume. This relative share of registered contracts remains generally stagnant with the share from the prior fiscal year.

Table 1: Volume of All Registered New Contracts and POs Citywide, FY21-23

| FY21 | FY22 | FY23 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certification Type | # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts | # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts | # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts |

| M/WBE | 21,373 | 22.41% | 24,696 | 18.12% | 27,070 | 18.39% |

| Non-Certified | 74,005 | 77.59% | 111,574 | 81.88% | 120,126 | 81.61% |

| Grand Total | 95,378 | 100.00% | 136,270 | 100.00% | 147,196 | 100.00% |

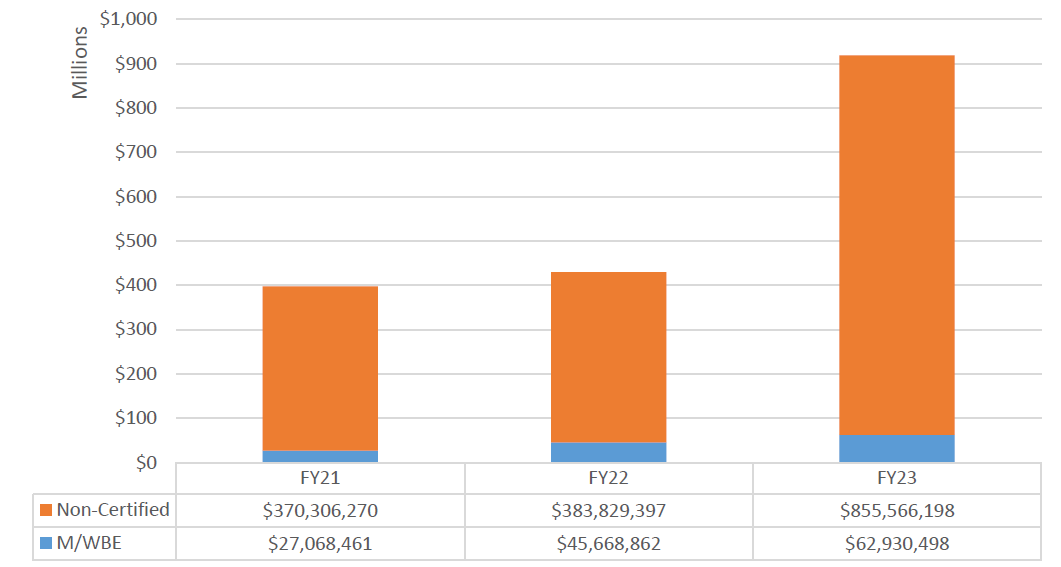

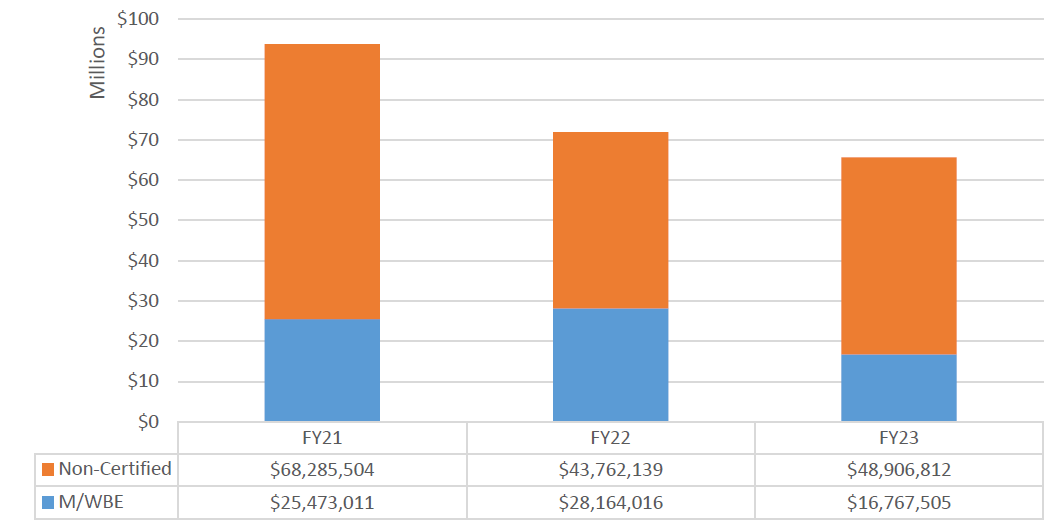

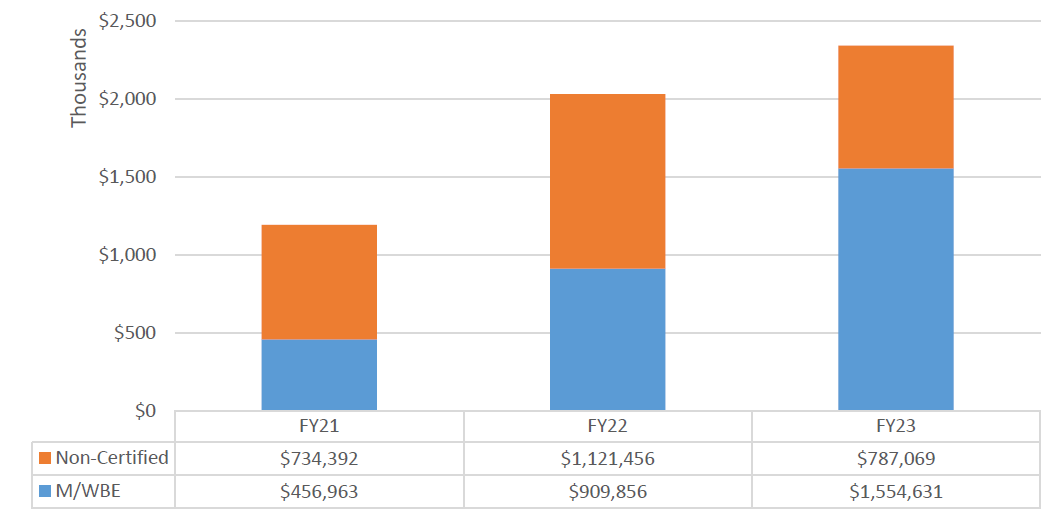

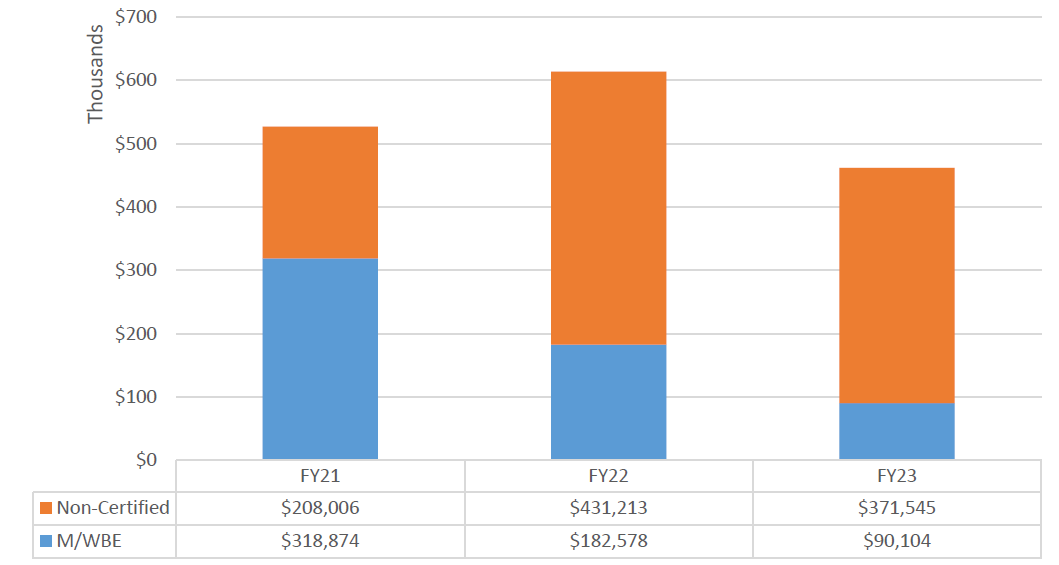

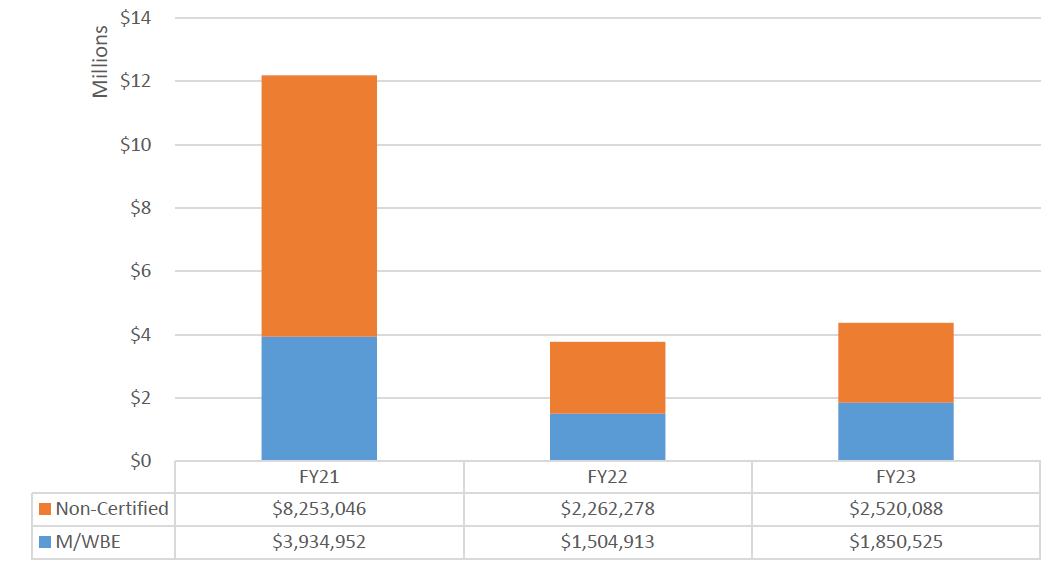

Table 2: Value of All Registered New Contracts and POs Citywide, FY21-23

| FY21 | FY22 | FY23 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certification Type | Total Registered Value | % Share of Value | Total Registered Value | % Share of Value | Total Registered Value | % Share of Value |

| M/WBE | $1,465,189,854 | 4.63% | $2,657,207,856 | 5.96% | $2,132,177,536 | 5.33% |

| Non-Certified | $30,198,591,820 | 95.37% | $41,903,392,903 | 94.04% | $37,887,459,942 | 94.67% |

| Grand Total | $31,663,781,674 | 100.00% | $44,560,600,759 | 100.00% | $40,019,637,477 | 100.00% |

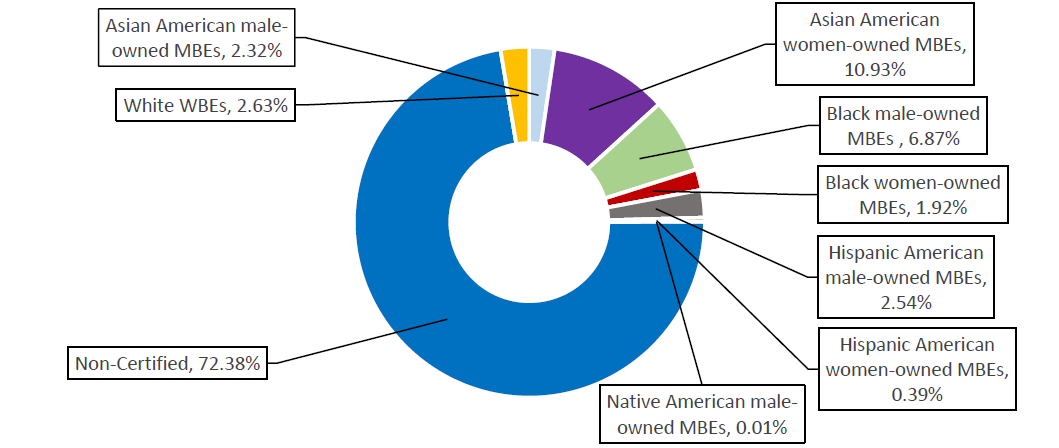

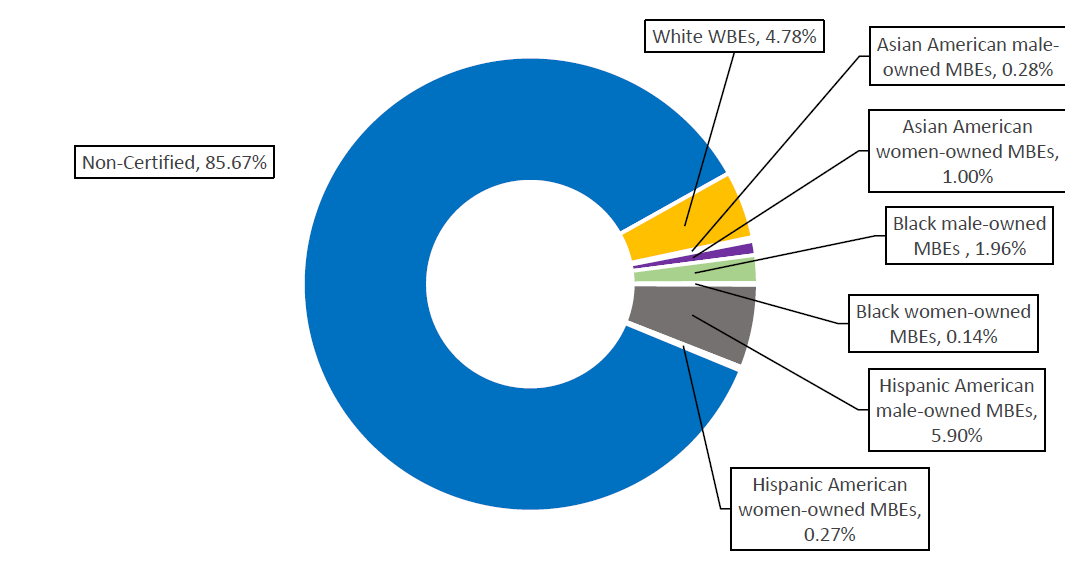

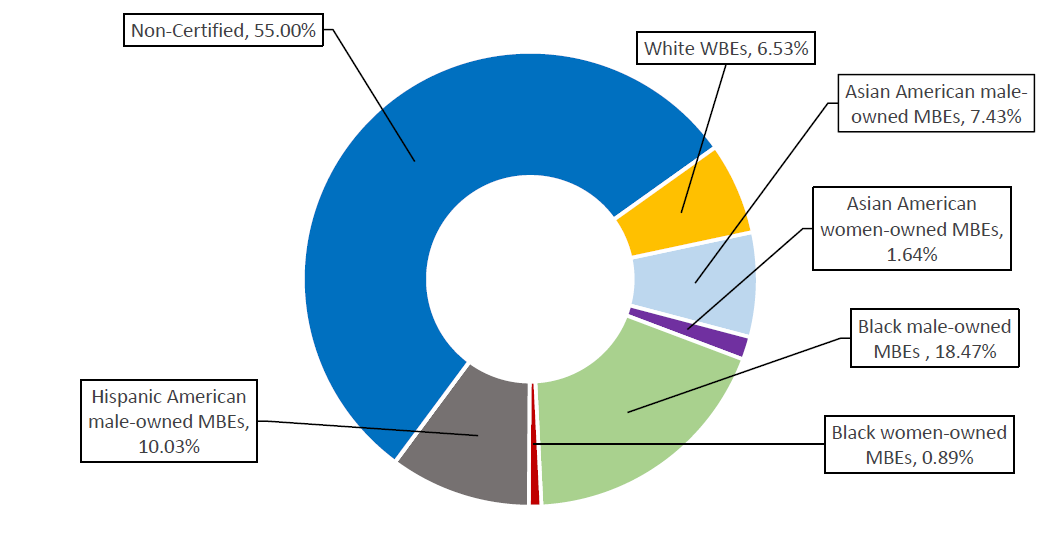

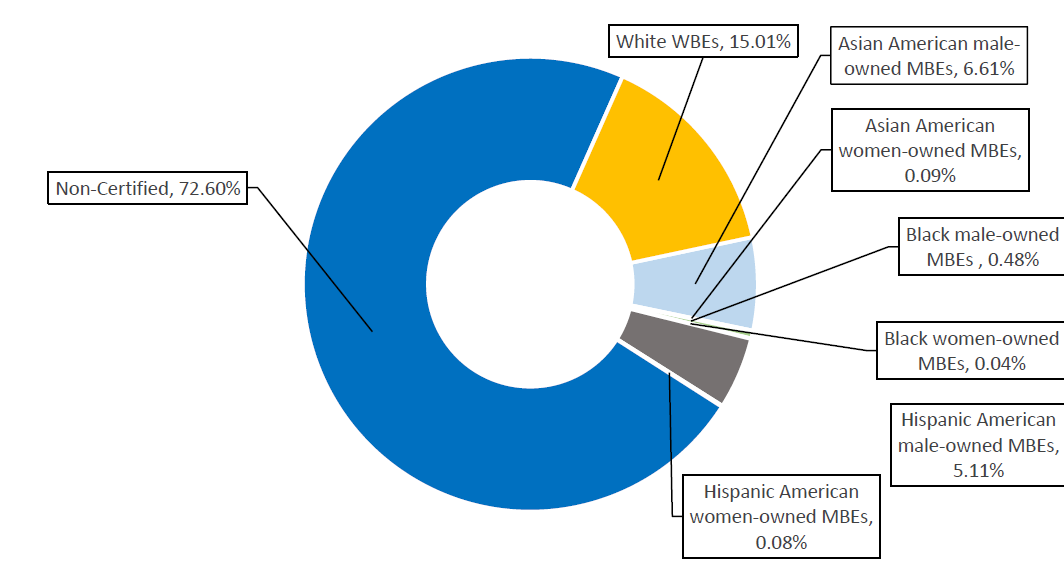

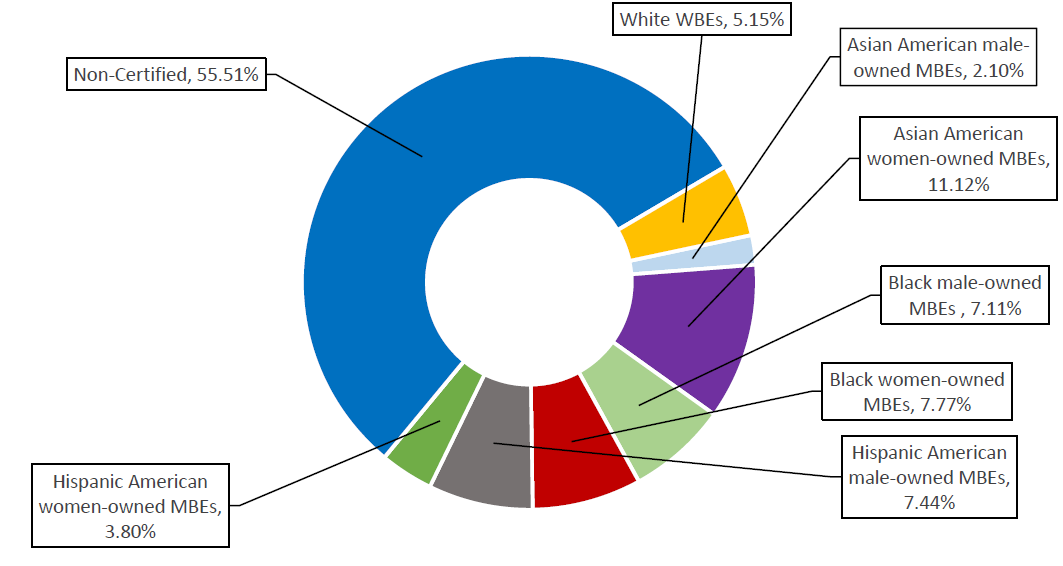

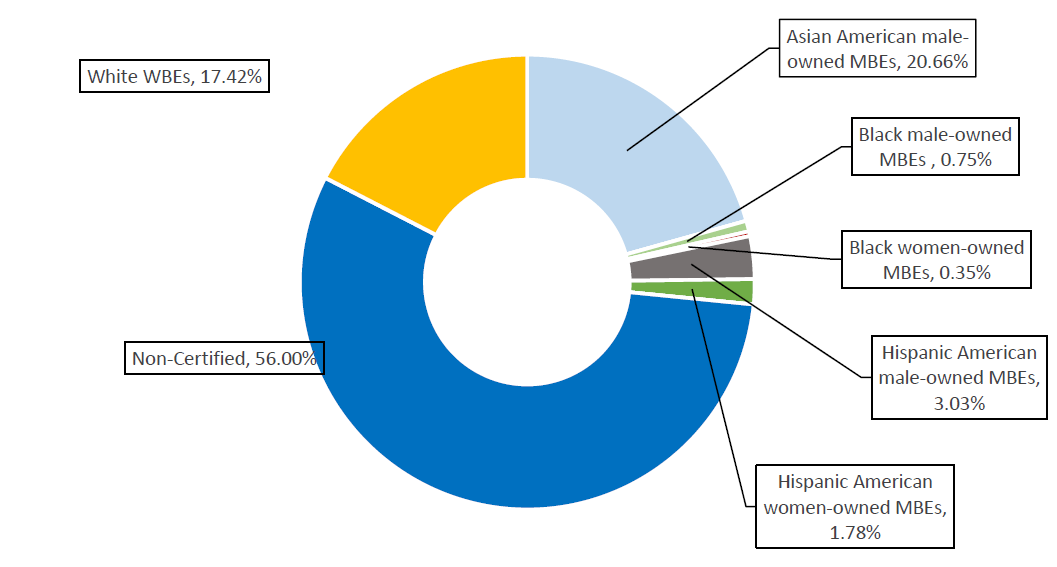

The numbers are somewhat better for new contract registrations and POs subject to LL 174 M/WBE participation goals. Per Tables 3 and 4, M/WBEs accounted for 60.32% of new contracts and POs subject to LL 174 participation goals by count, and 9.82% of the associated value.[26] The 9.82% share reflects a decrease from prior fiscal years.

This small share is especially disappointing, given the actual diversity and demographics of the City. For reference throughout this report: According to the U.S. Census, in 2022, New York City was 31.9% non-Hispanic white, 28.9% Hispanic or Latino, 23.4% Black, 14.3% Asian or Pacific Islander, 0.5% Native American, and 7.1% two or more races. 52% of New Yorkers identify as female, and 48% male.[27]

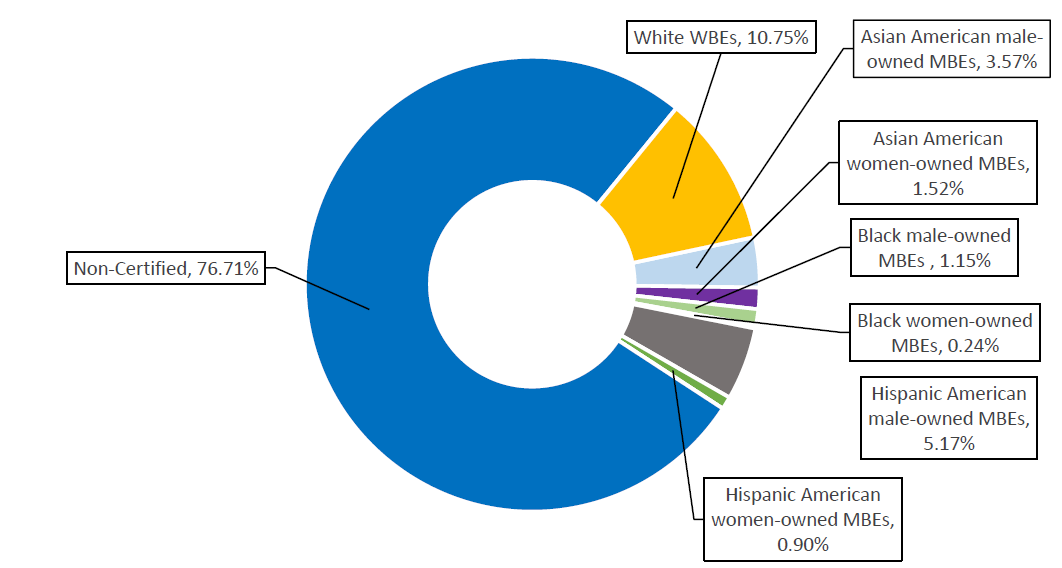

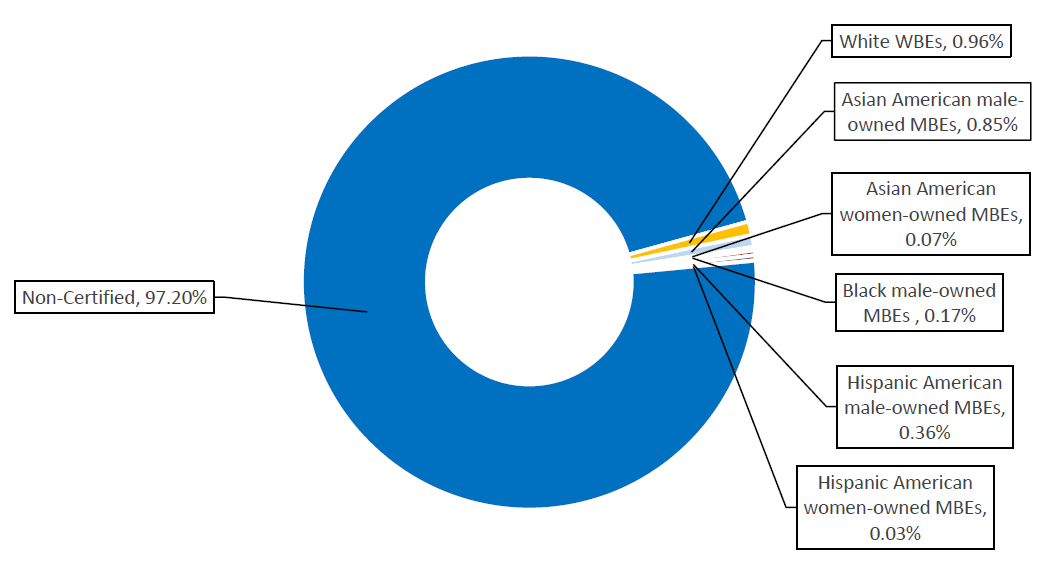

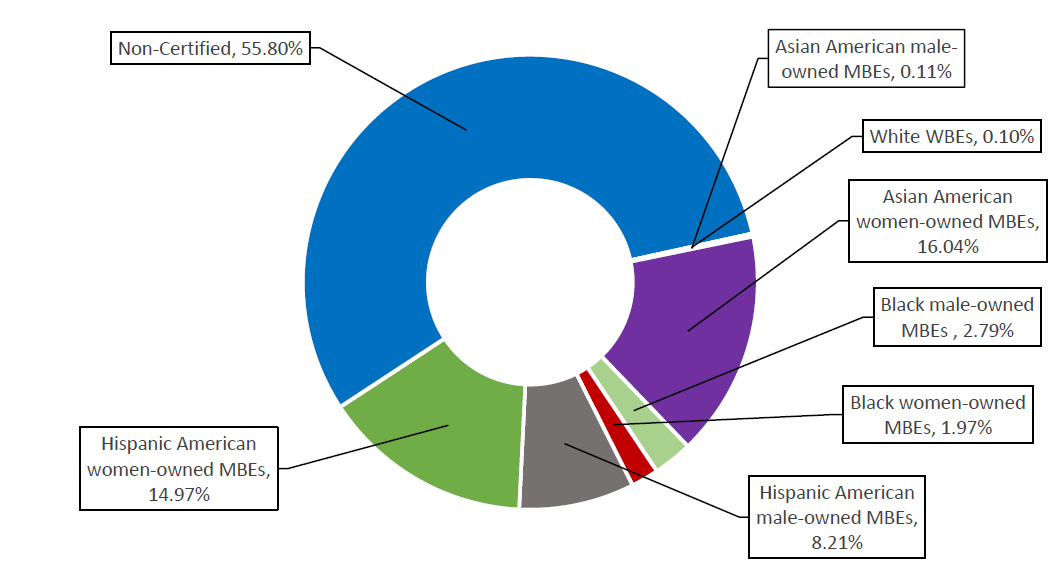

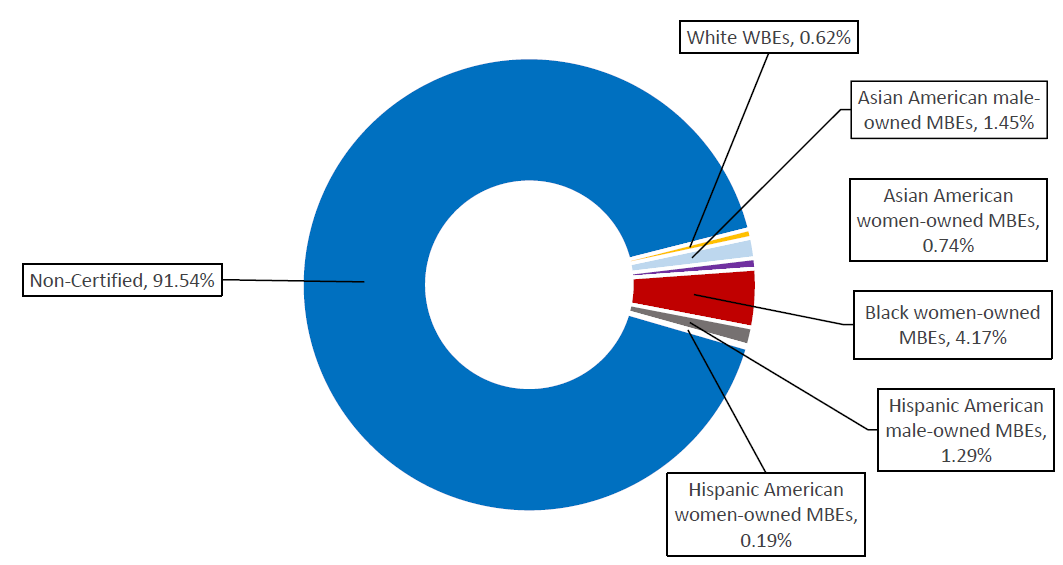

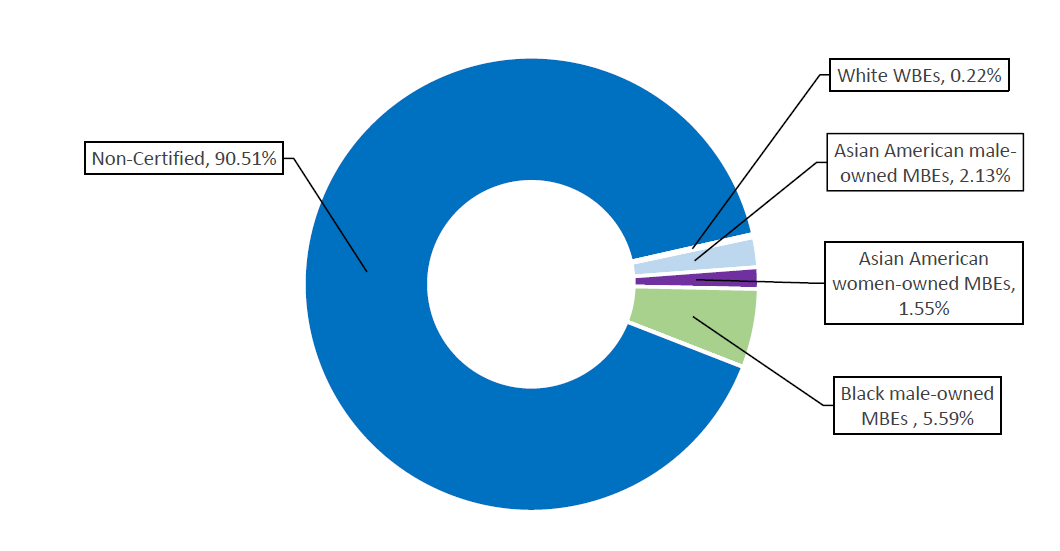

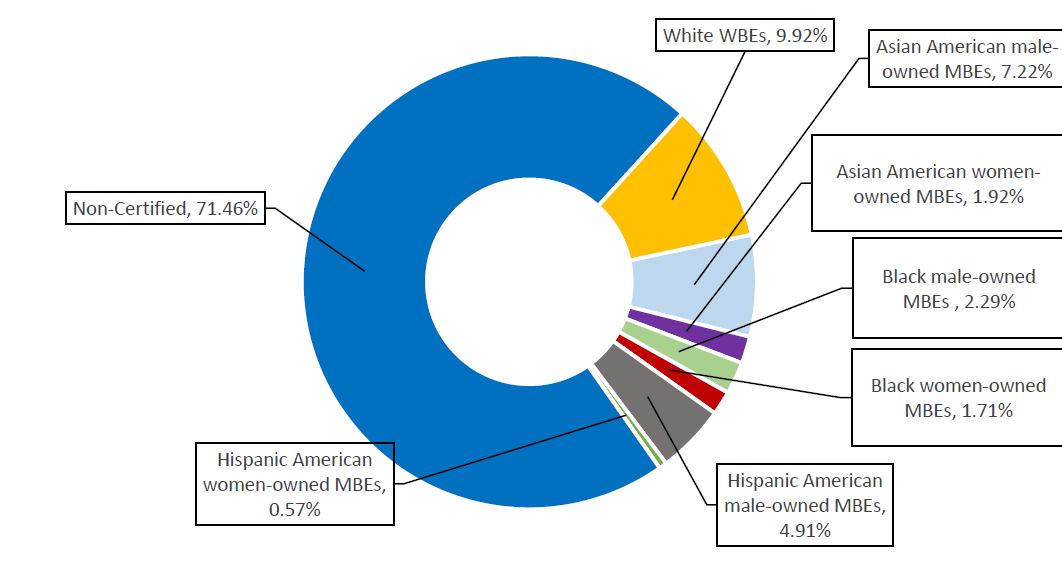

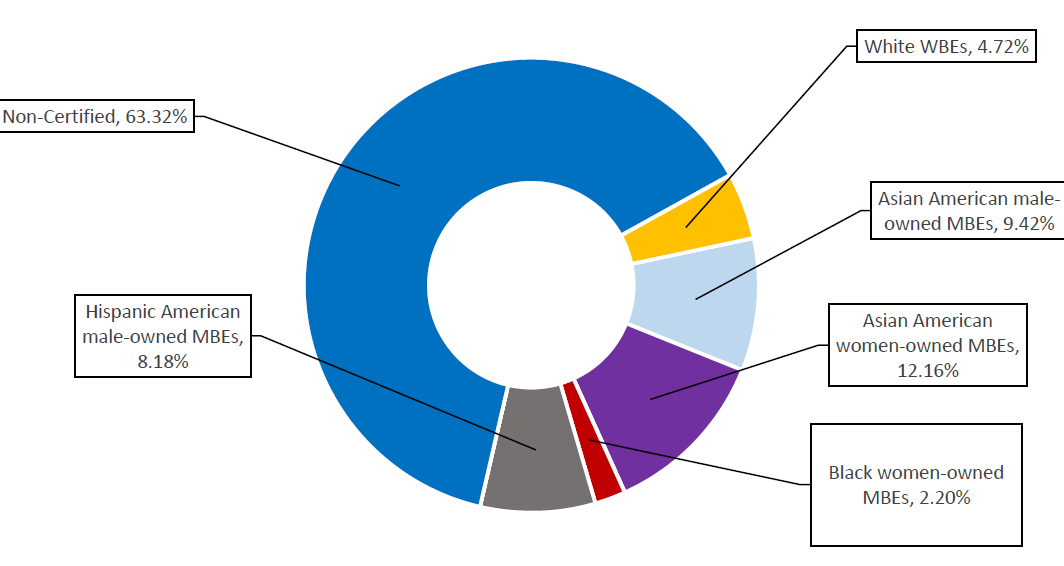

Chart 2: FY23 Value of Contracts and POs Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals

Table 3: Volume of Contracts and POs Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, FY21-23

| FY21 | FY22 | FY23 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certification Type | # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts | # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts | # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts |

| M/WBE | 16,072 | 61.77% | 16,900 | 58.54% | 16,641 | 60.32% |

| Non-Certified | 9,948 | 38.23% | 11,970 | 41.46% | 10,947 | 39.68% |

| Grand Total | 26,020 | 100.00% | 28,870 | 100.00% | 27,588 | 100.00% |

Table 4: Value of Prime Contracts and POs Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, FY21-23[28]

| FY21 | FY22 | FY23 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certification Type | Total Registered Value | % Share of Value | Total Registered Value | % Share of Value | Total Registered Value | % Share of Value |

| M/WBE | $881,827,424 | 16.83% | $972,368,134 | 16.01% | $930,747,603 | 9.82% |

| Non-Certified | $4,357,238,649 | 83.17% | $5,100,754,332 | 83.99% | $8,543,566,158 | 90.18% |

| Grand Total | $5,239,066,073 | 100.00% | $6,073,122,466 | 100.00% | $9,474,313,761 | 100.00% |

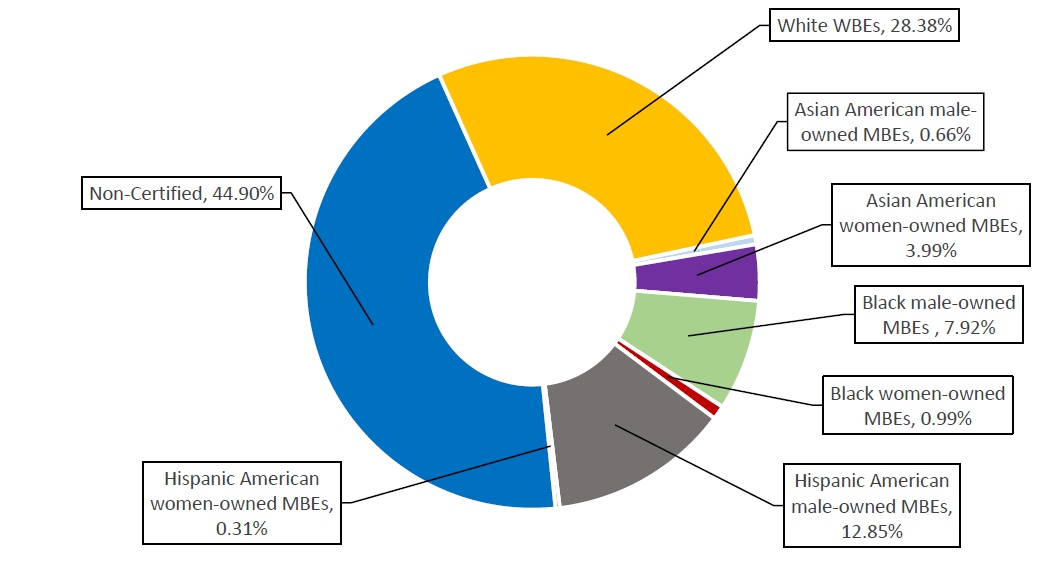

For a number of reasons, including the pervasive underreporting of subcontract data in PIP, this Report’s primary focus is on the utilization of M/WBEs within prime contracting. Mayoral agencies approved subcontract records against just 380 (~13%) of the 2,927 LL 174-eligible prime contracts registered in FY23 at the time the data for this report was pulled from FMS.[29] The 1,246 subcontract records entered for M/WBEs accounted for $539.79 million (44.90%) of the $1.2 billion in recorded subcontract value, significantly exceeding the ratio among prime contracts. It is important to note that subcontract values are not additive to the value of prime contract registrations given that they reflect a subset of the reported prime values. As such, this Report does not combine prime and subcontract utilization figures.

Table 5: FY23 Volume and Value of Subcontracts in PIP Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals

| Certification Type | # of Subcontracts | % Share of Subcontracts | Total Subcontract Value | % Share of Subcontract Value |

| M/WBE | 1,246 | 61.87% | $539,799,664 | 44.90% |

| Non-Certified | 768 | 38.13% | $662,509,594 | 55.10% |

| Grand Total | 2,014 | 100.00% | $1,202,309,258 | 100.00% |

Among the 36 rated agencies in this Report (Mayoral agencies, the Office of the Comptroller, and the DOE), 23 had zero approved subcontract records in PIP against LL 174-eligible prime contracts. DOE was the holder of the largest number of LL 174-eligible contracts in FY23 among this group. Without subcontract records in PIP, there is insufficient detail for oversight agencies to measure that agencies and vendors are both compliant with and progressing towards achieving required M/WBE participation goals.

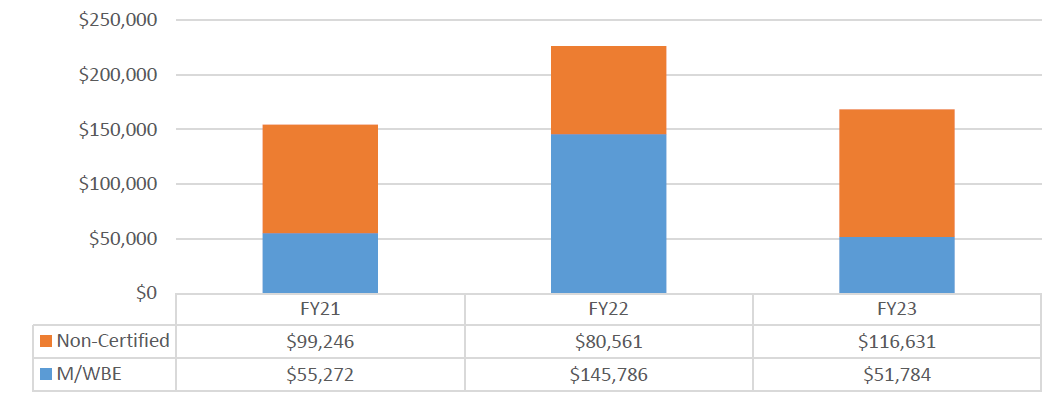

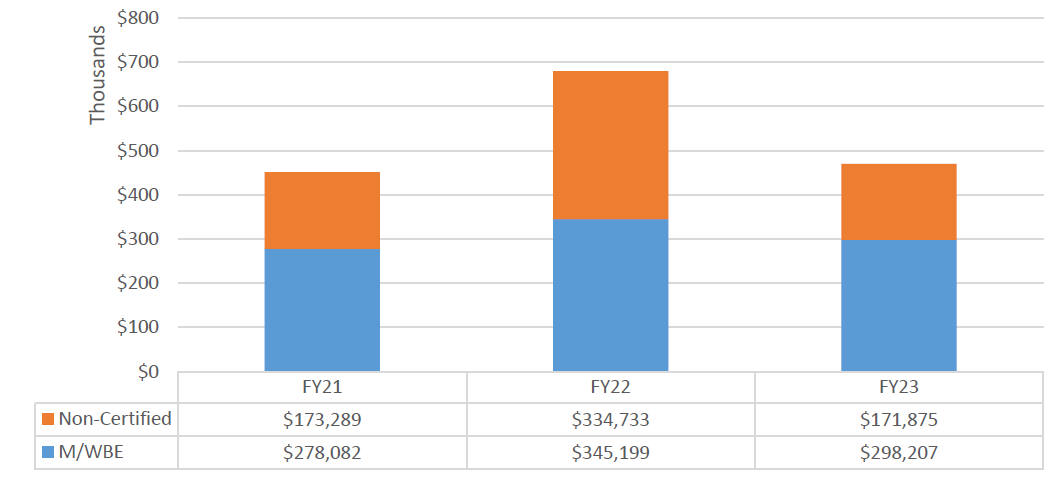

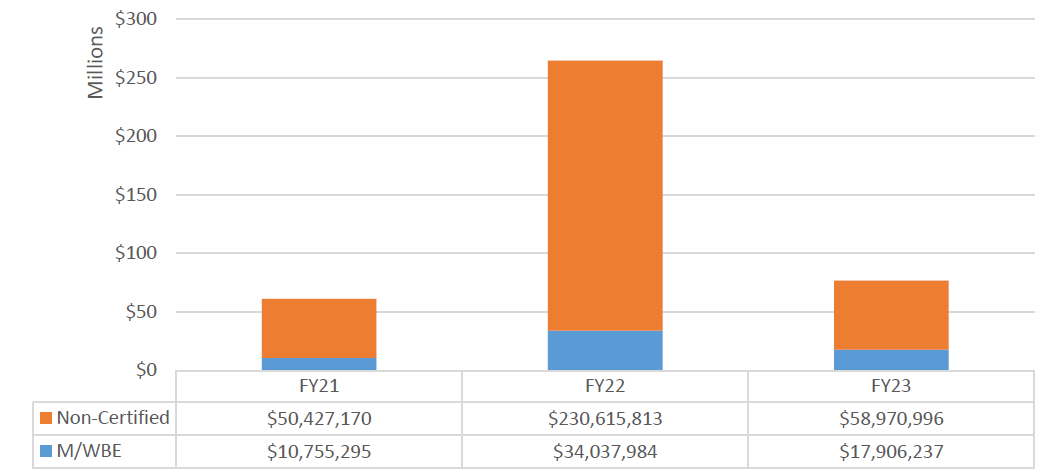

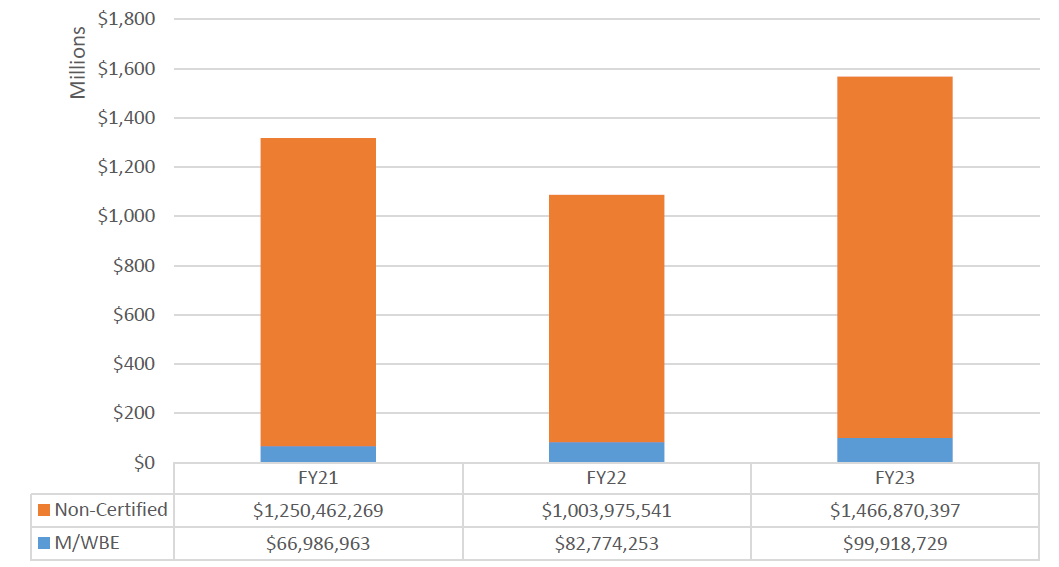

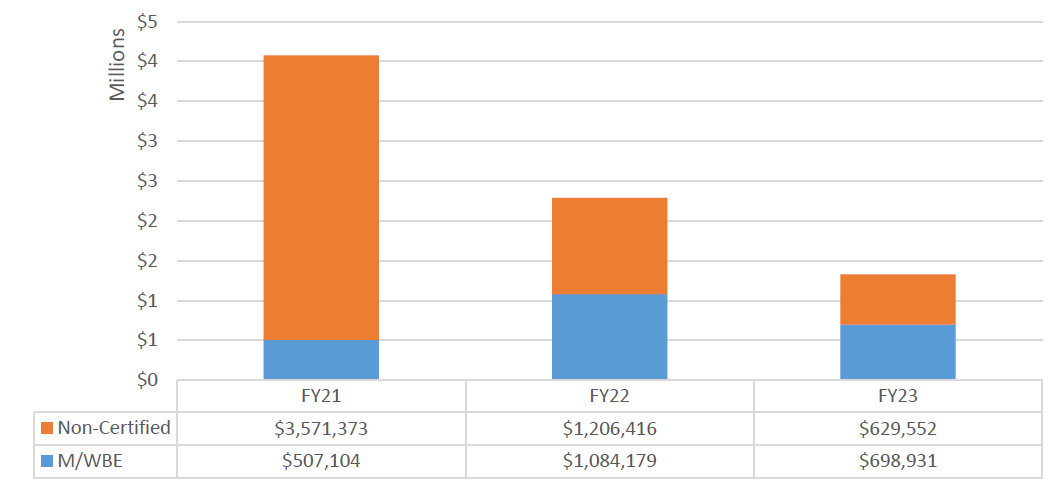

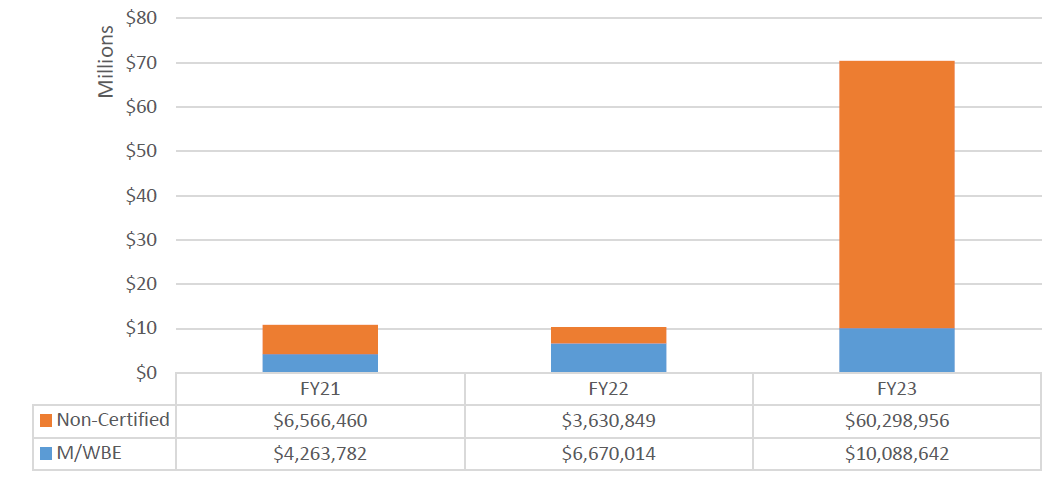

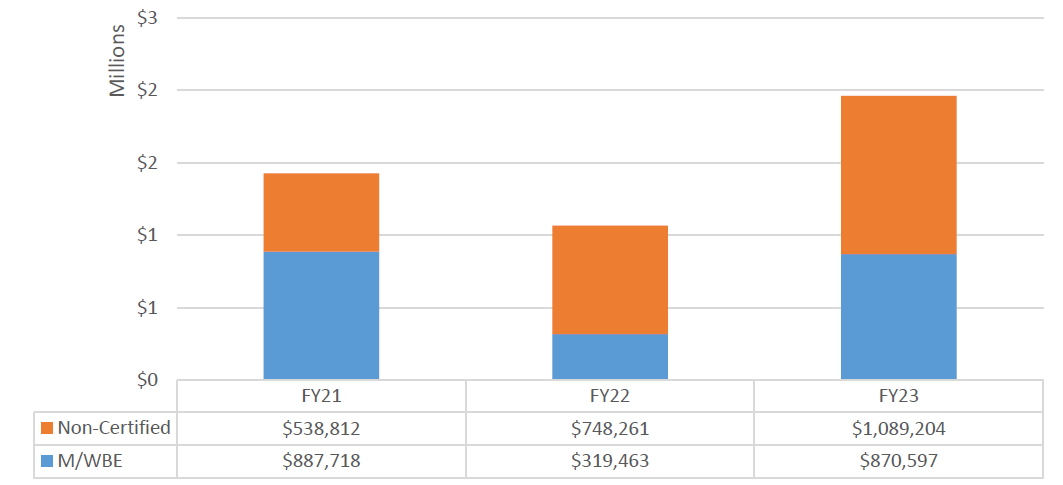

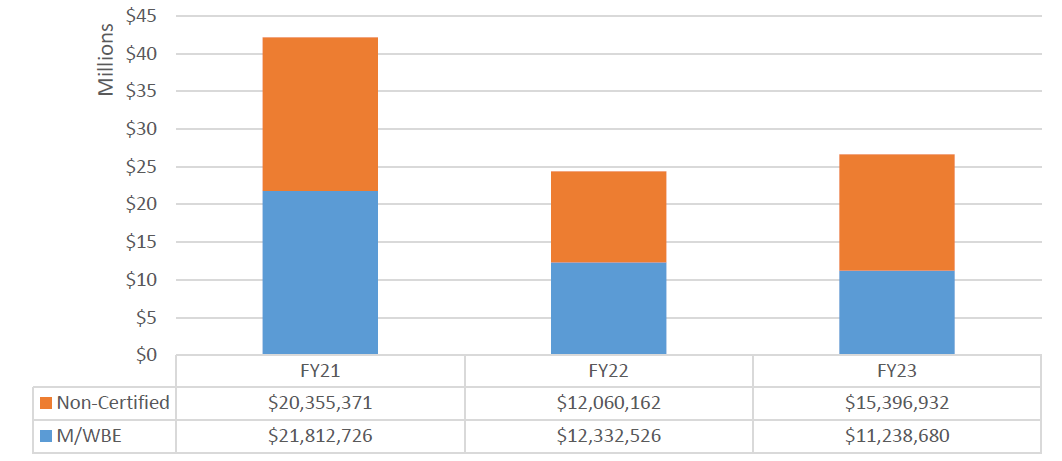

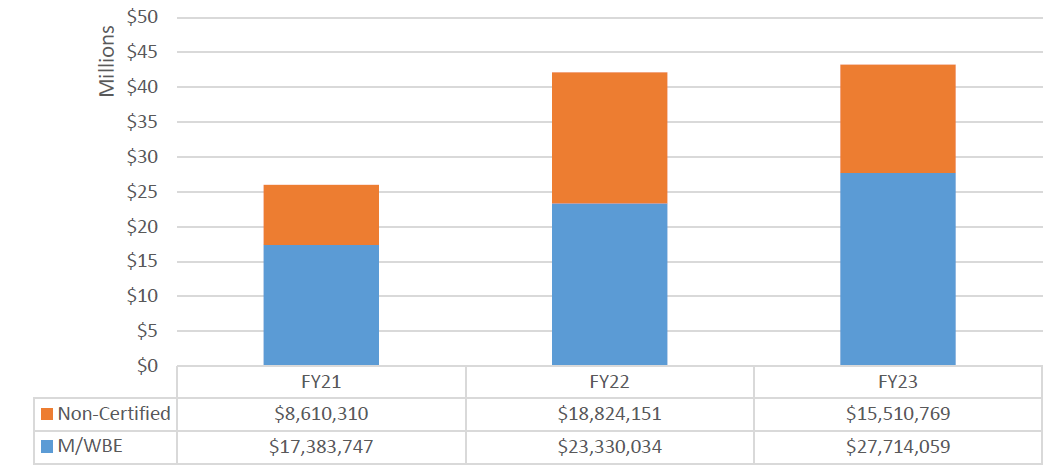

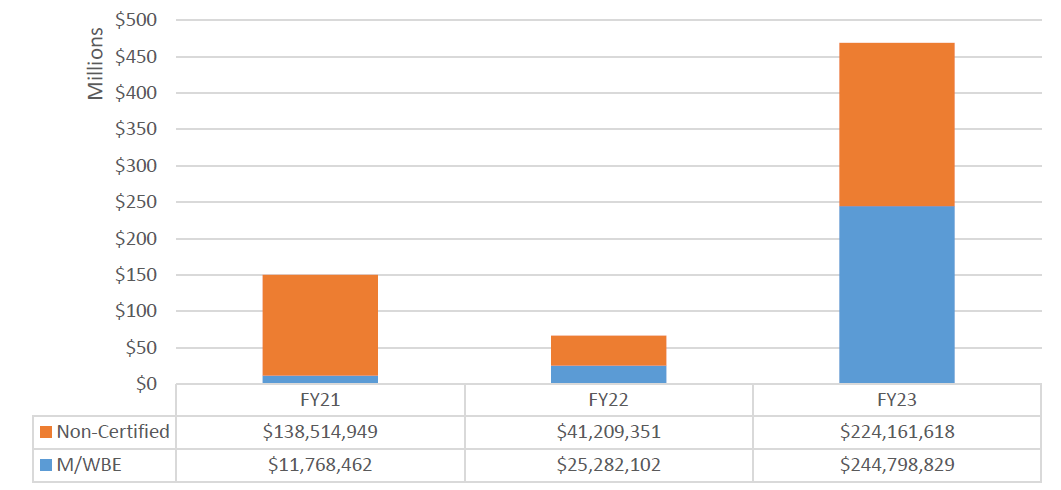

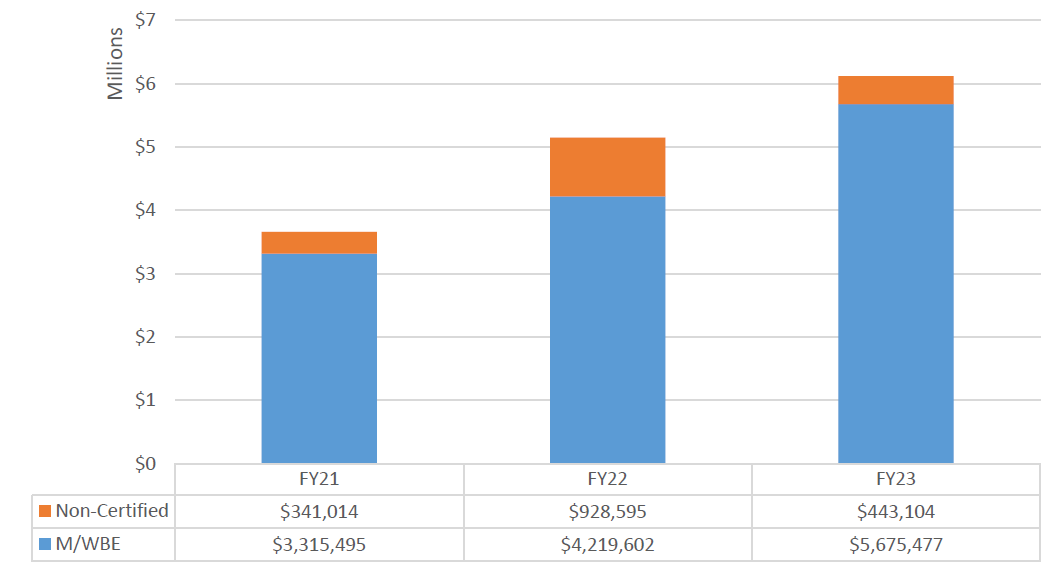

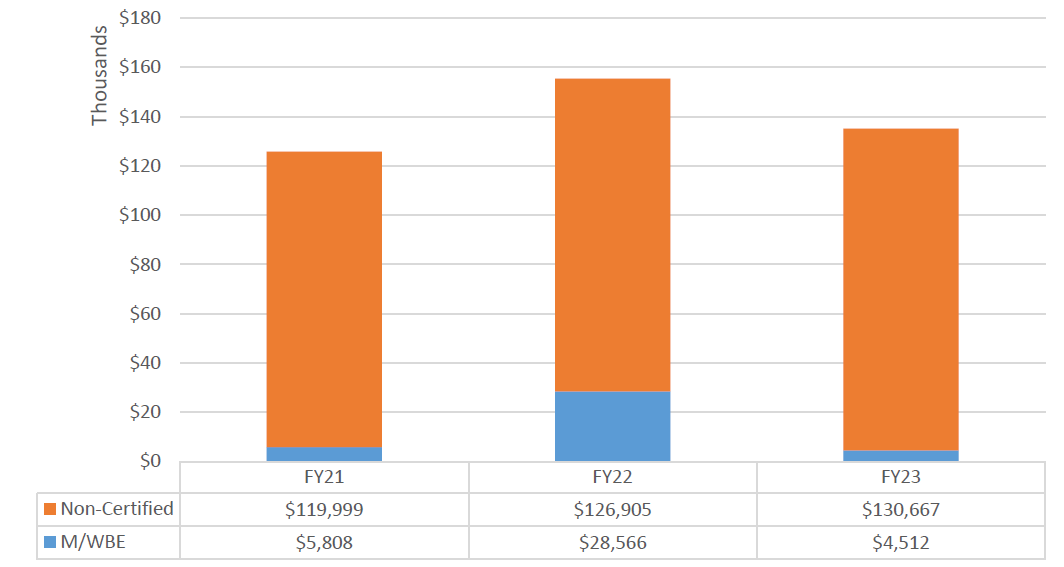

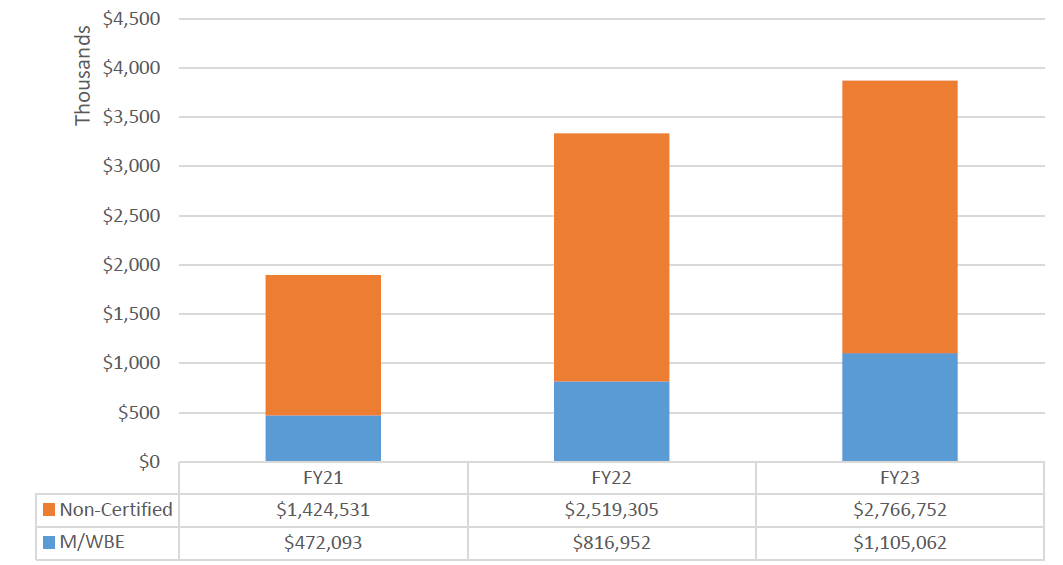

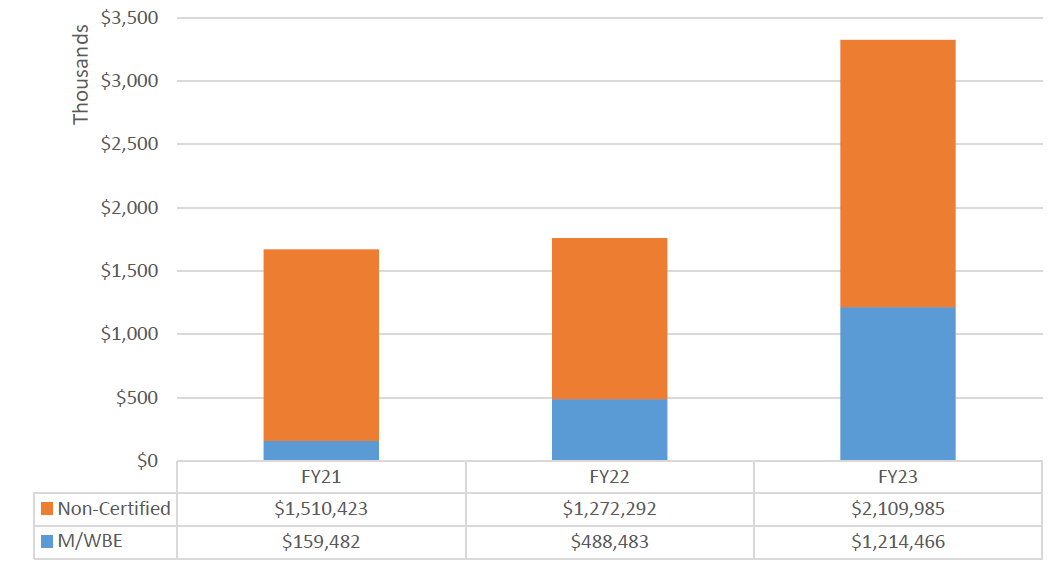

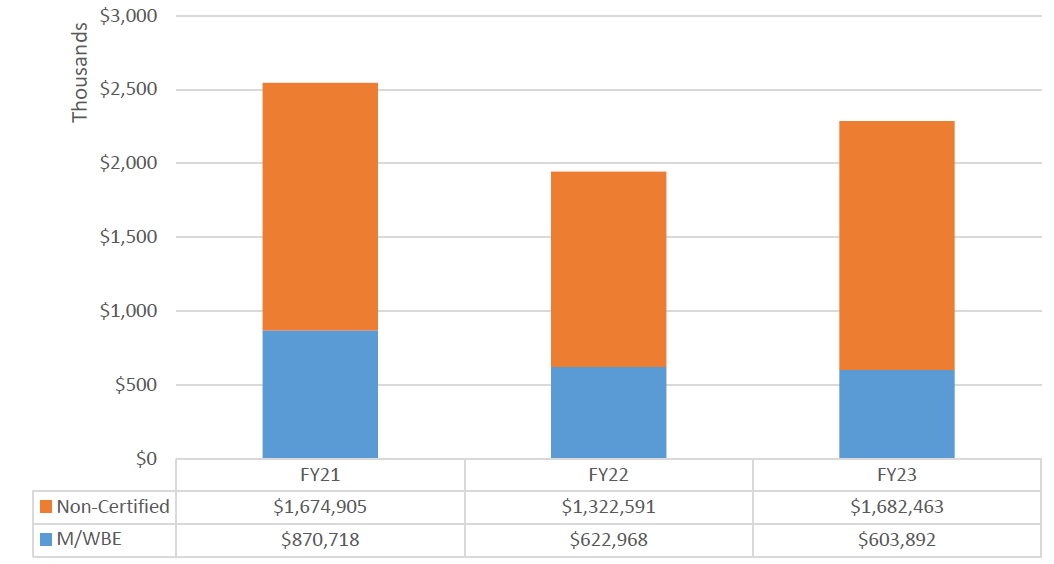

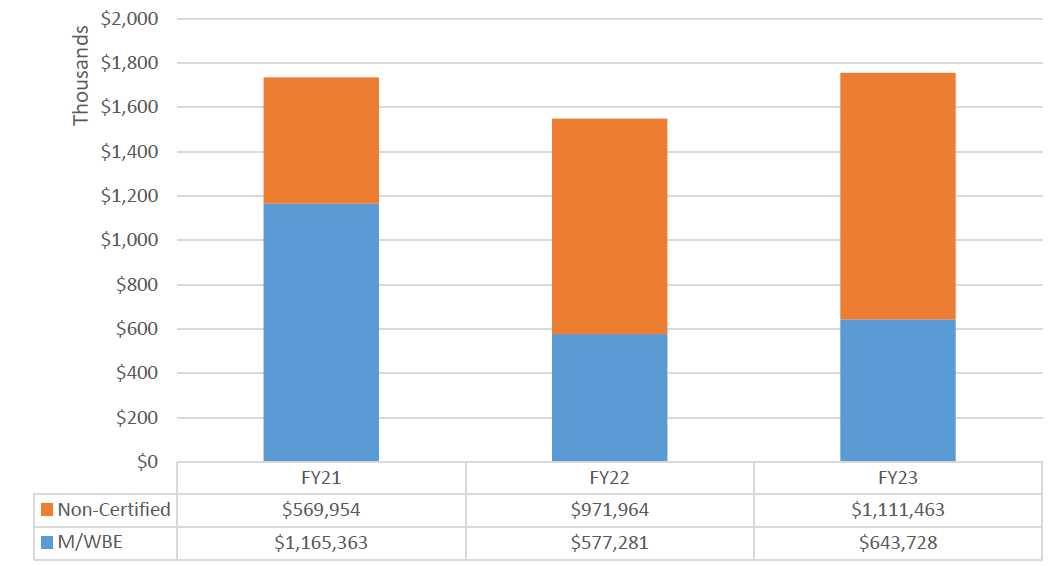

Spend

In addition to analyzing contract registration data, this Report also summarizes data relating to the City’s actual payments to vendors. This includes all payments made to both prime and sub vendors in FY23 (regardless of the year the contract was registered in).

To determine what spending was subject to LL 174 performance goals, individual transactions were mapped their corresponding contract or purchase order. LL 174 exclusions were then applied based on the characteristics of the contracts or POs associated with vendor payments.

The City spent a total of $11.79 billion in FY23 (prime contracts registered in FY23 and prior fiscal years subject to LL 174 participation goals), 9.51% of which ($1.12 billion) was spent with M/WBE primes.

Table 6: Prime Spend Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, FY21-23[30]

| FY21 | FY22 | FY23 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certification Type | Total Registered Value | % Share of Value | Total Registered Value | % Share of Value | Total Registered Value | % Share of Value |

| M/WBE | $551,356,188 | 9.84% | $531,495,571 | 9.45% | $1,122,110,711 | 9.51% |

| Non-Certified | $5,053,372,286 | 90.16% | $5,091,193,324 | 90.55% | $10,676,634,838 | 90.49% |

| Grand Total | $5,604,728,473 | 100.00% | $5,622,688,895 | 100.00% | $11,798,745,549 | 100.00% |

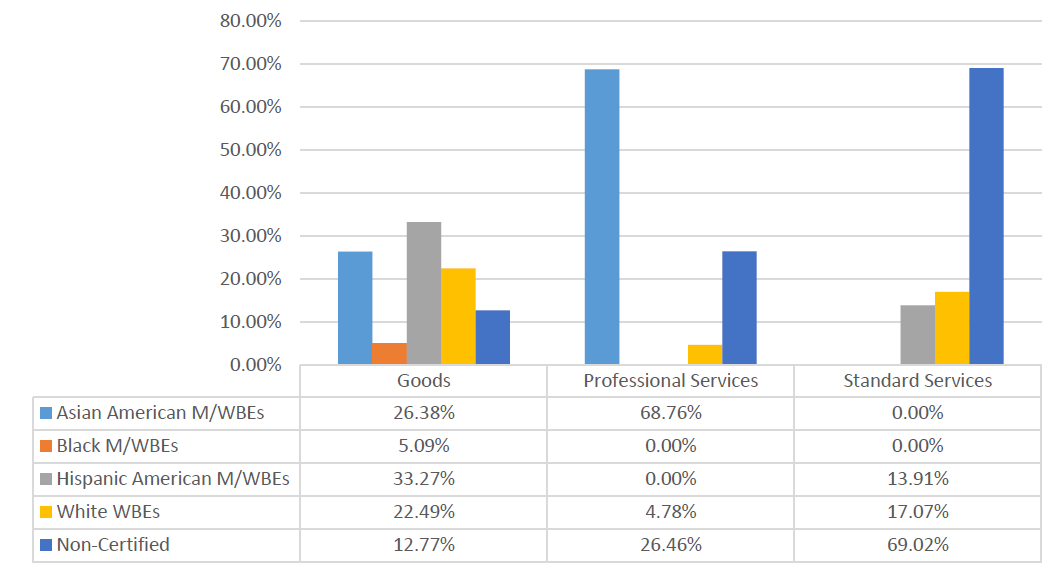

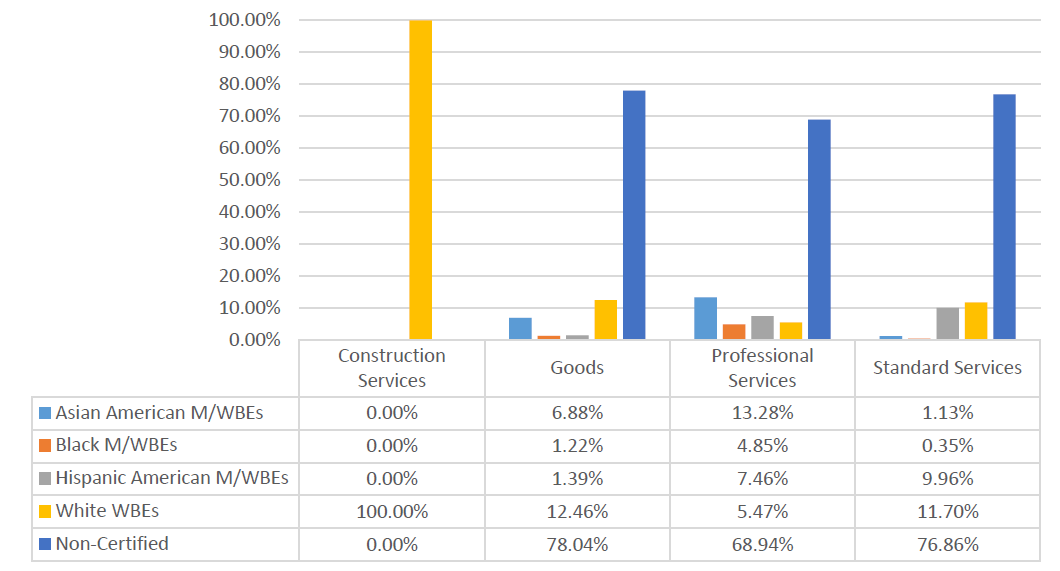

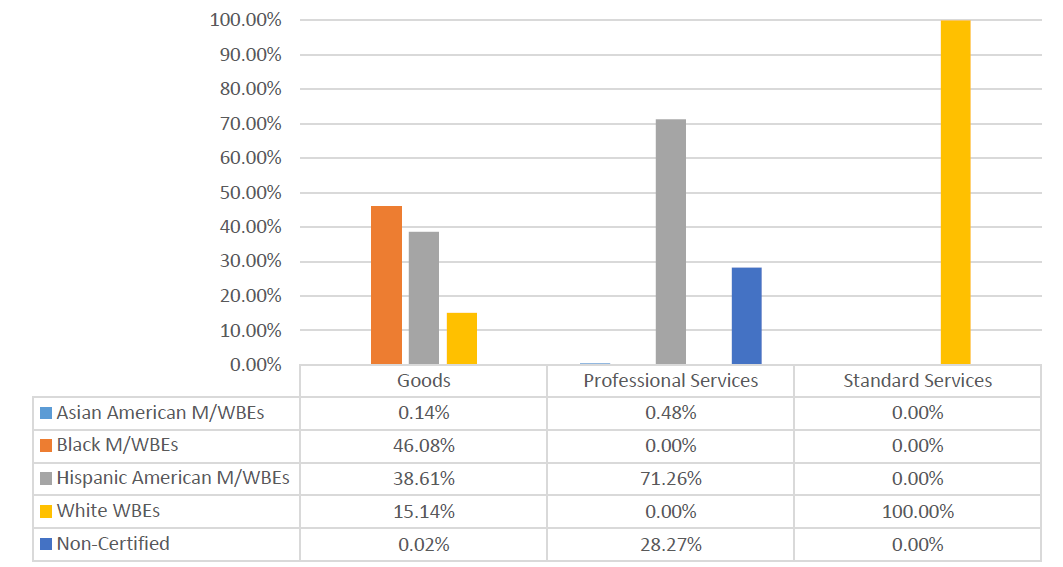

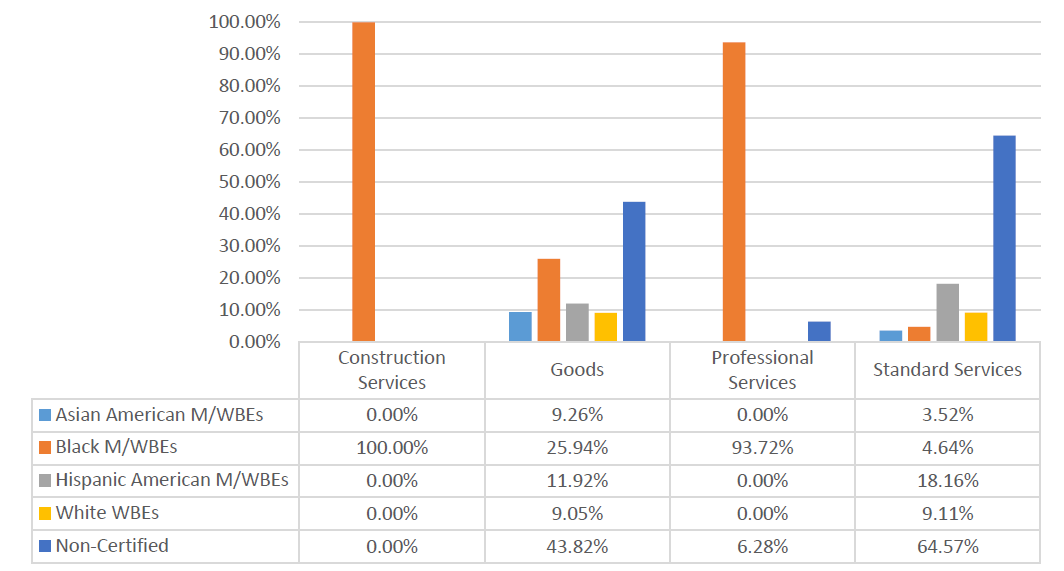

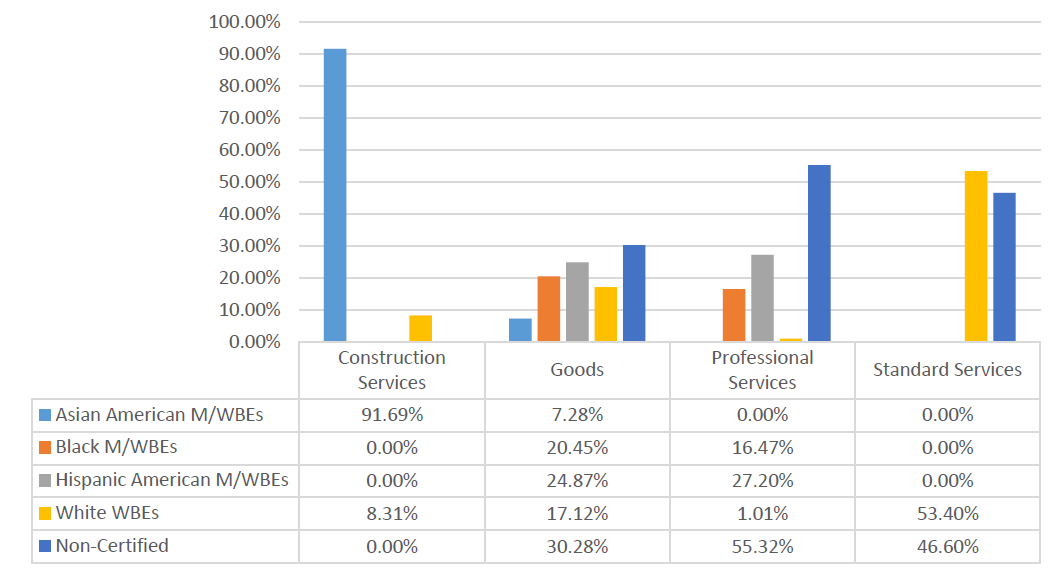

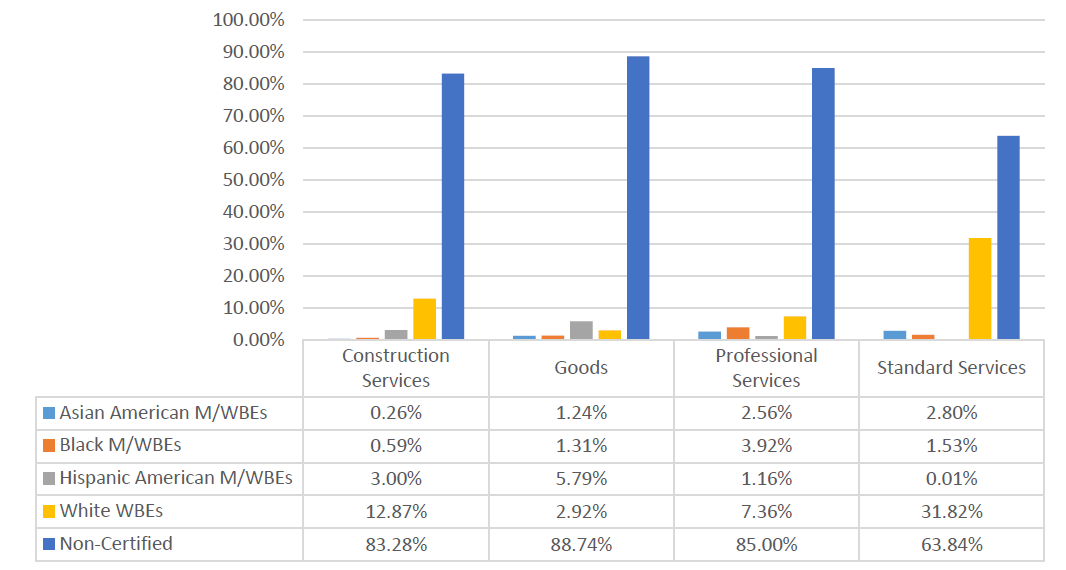

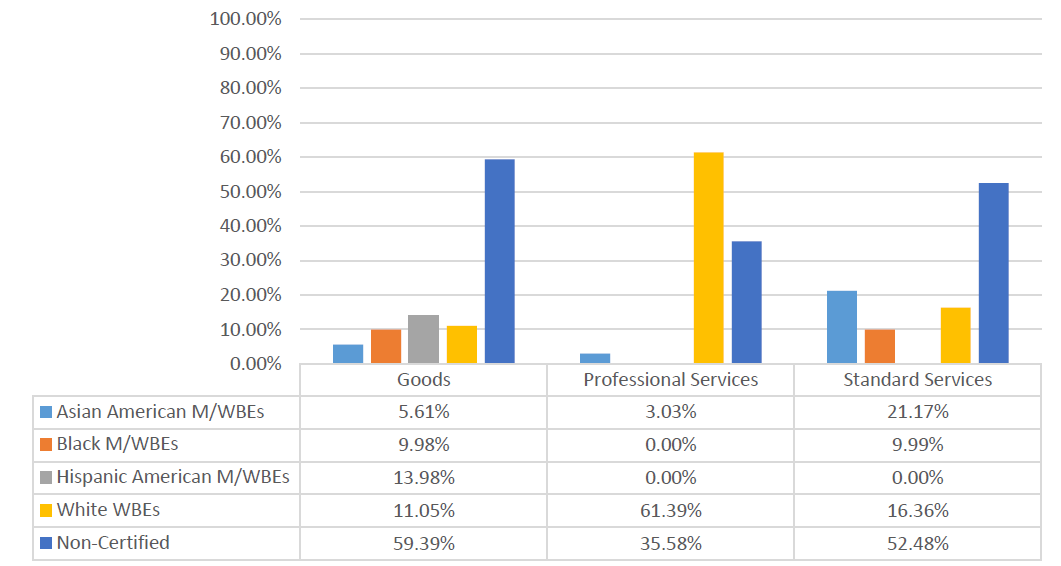

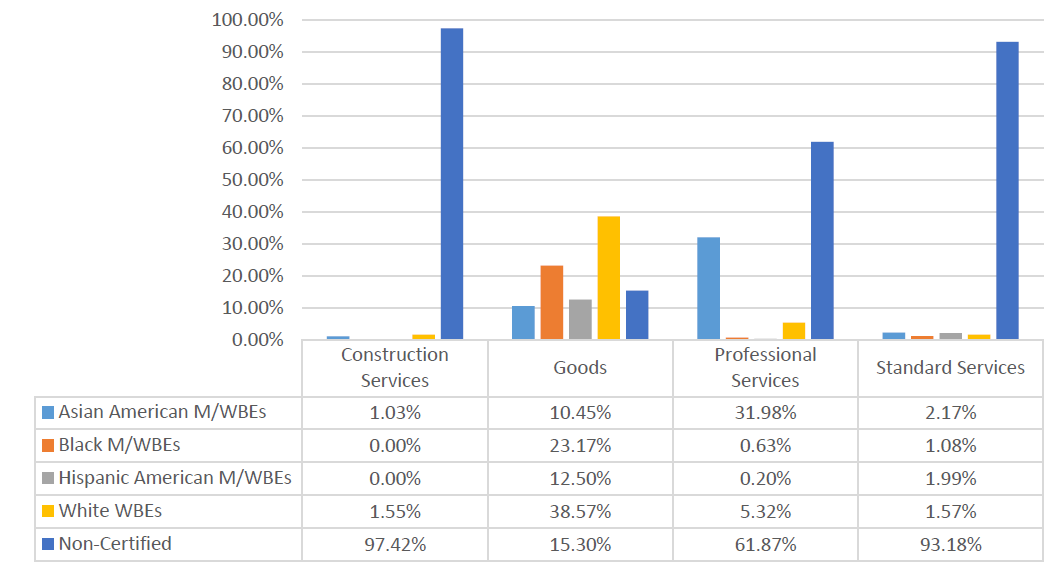

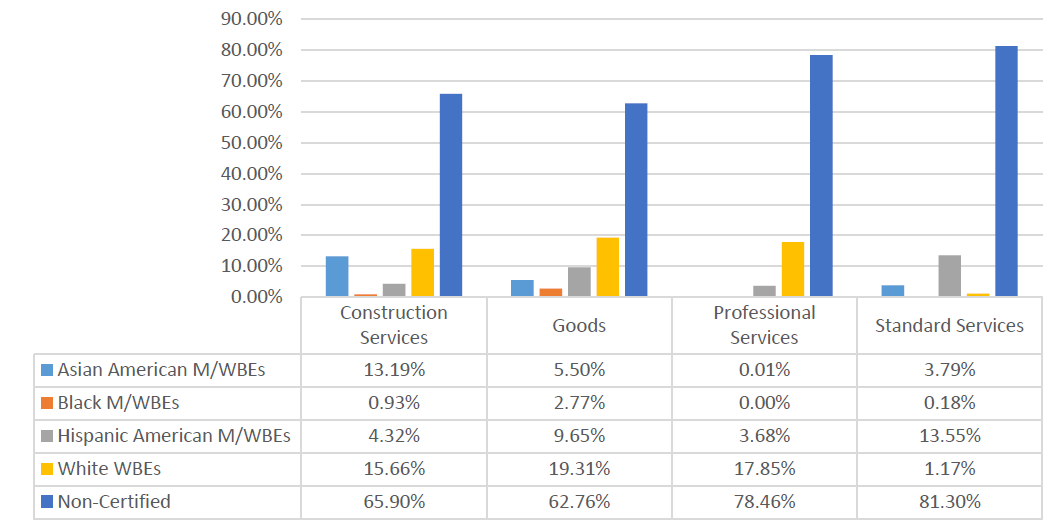

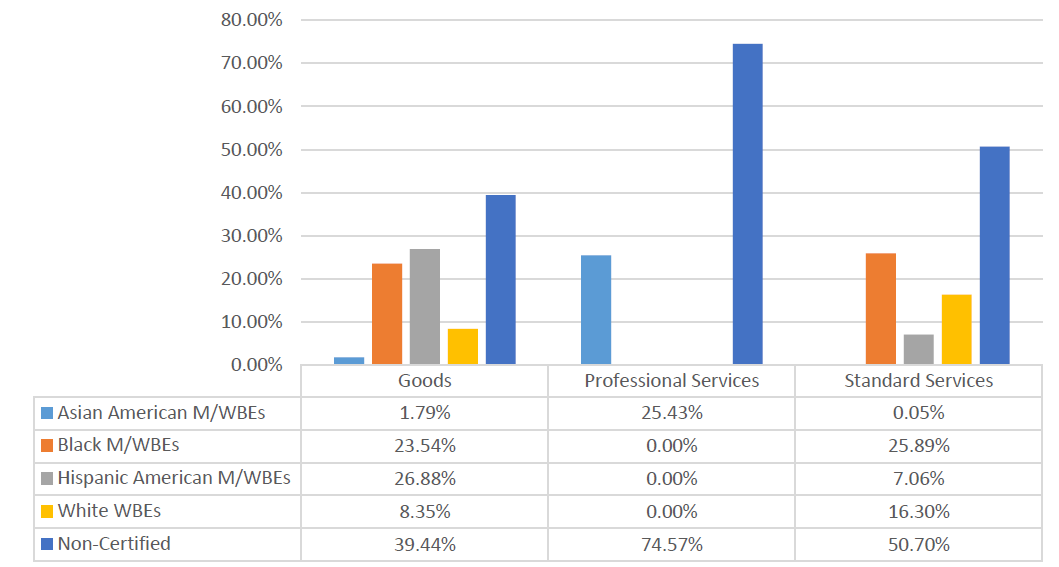

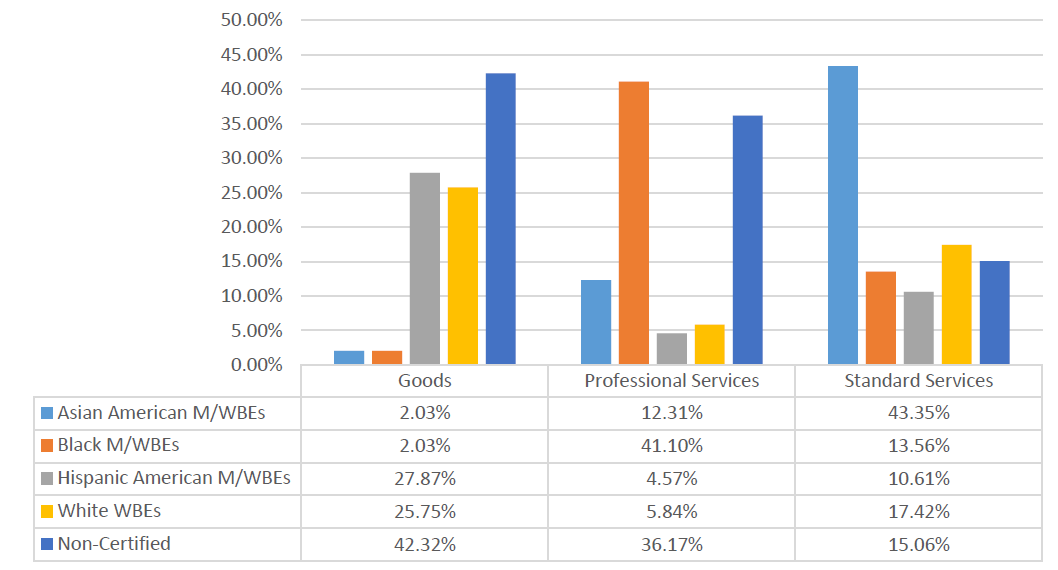

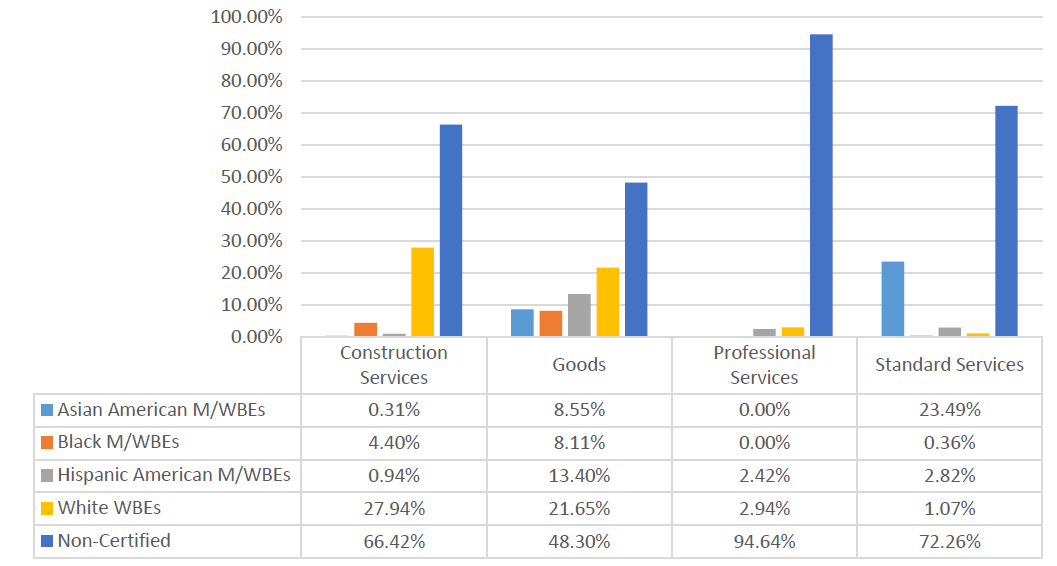

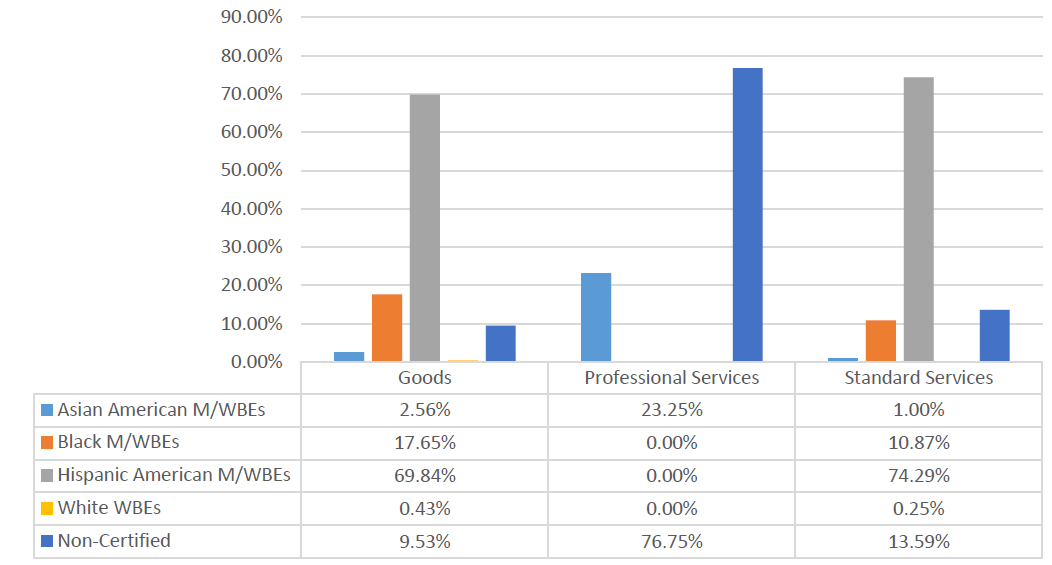

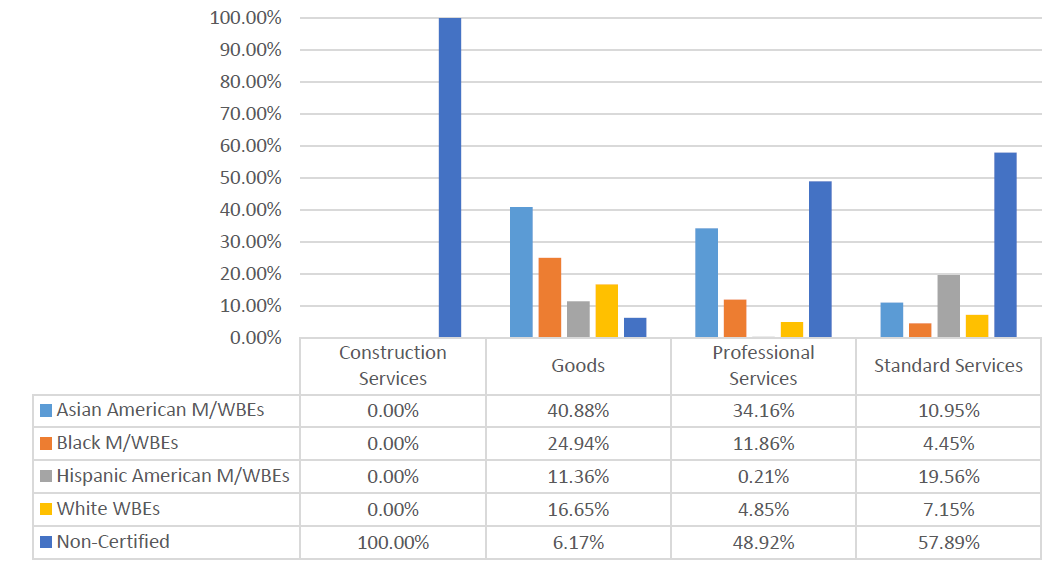

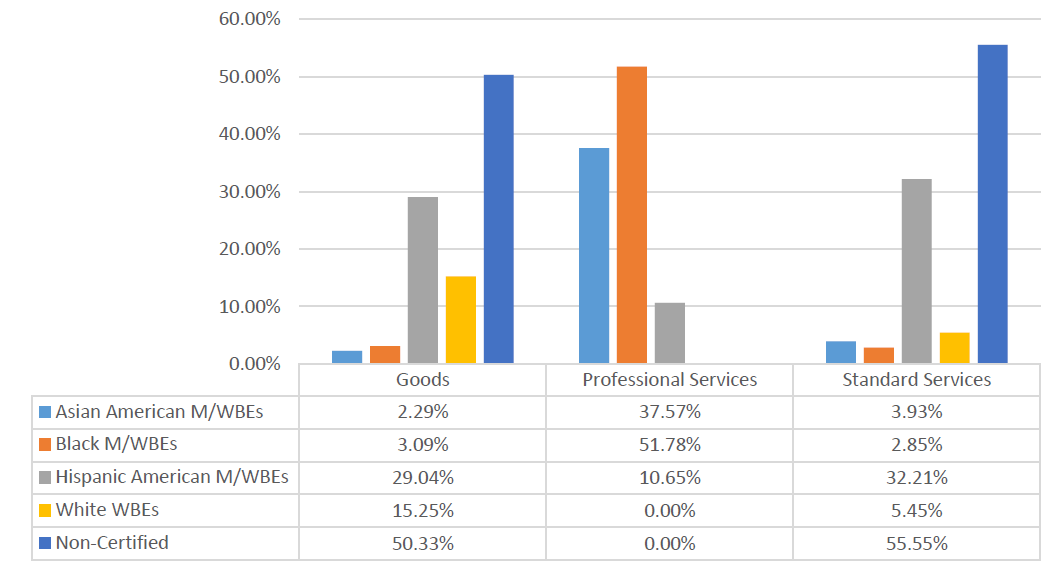

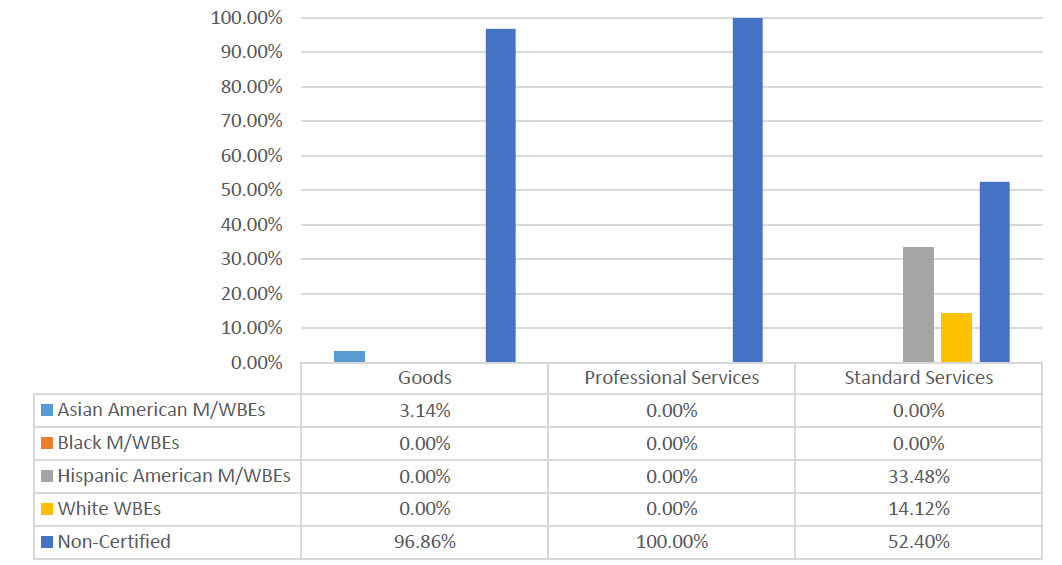

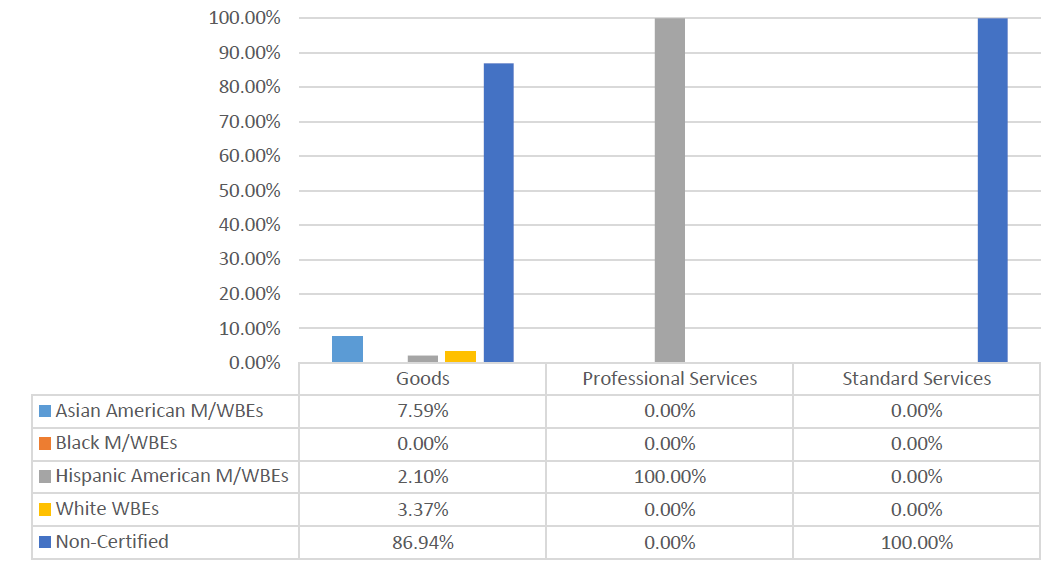

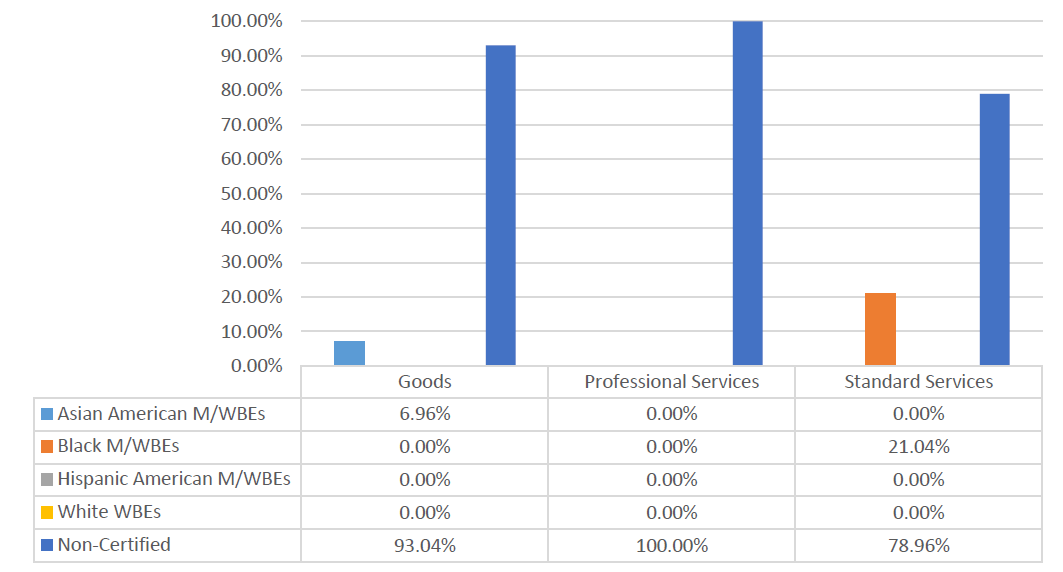

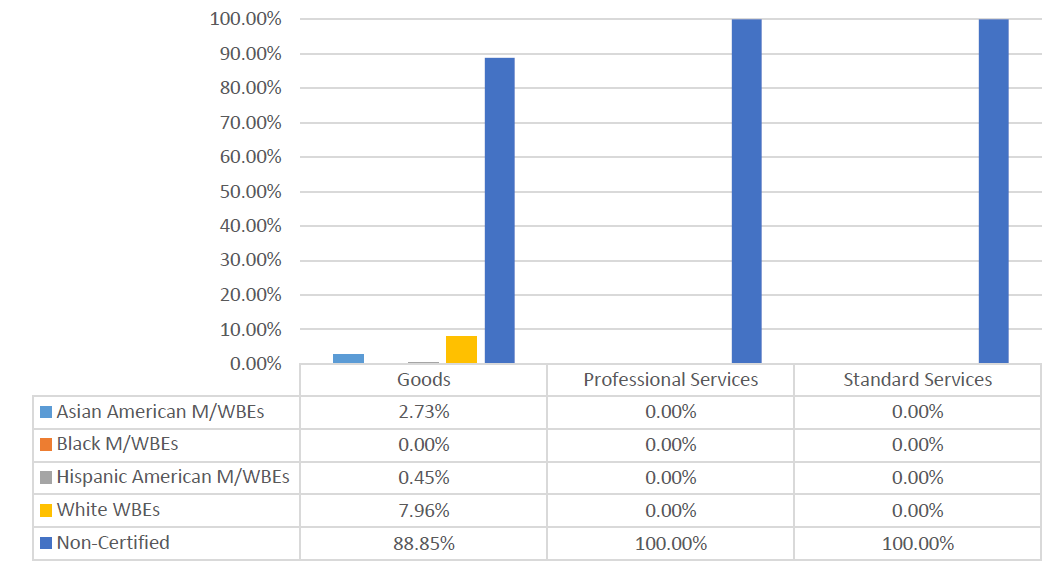

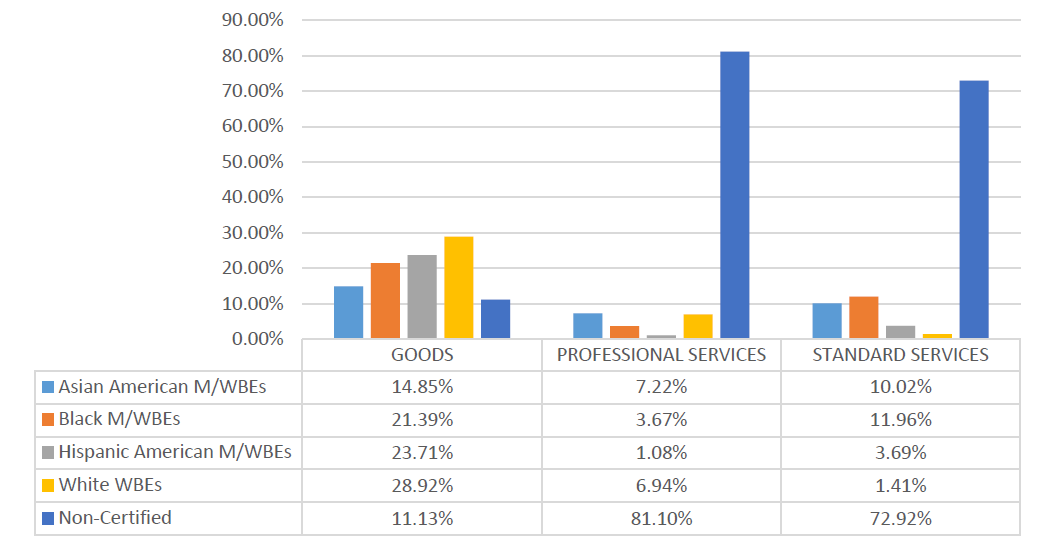

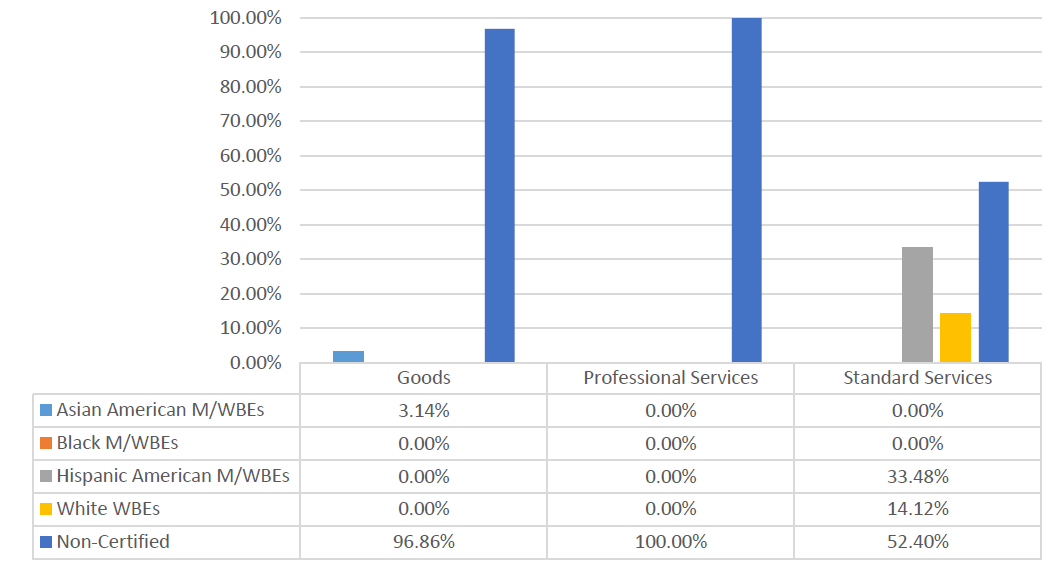

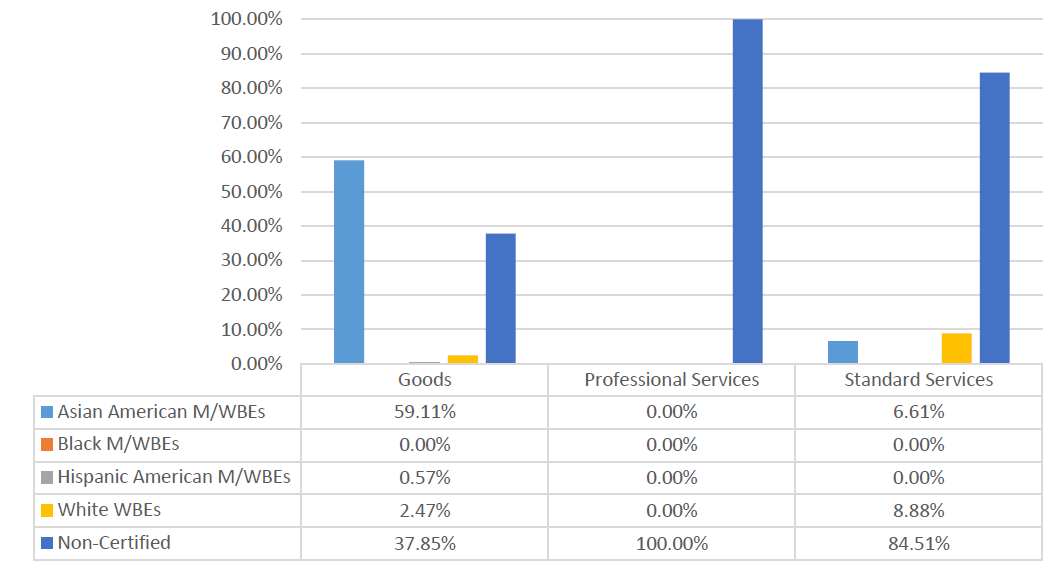

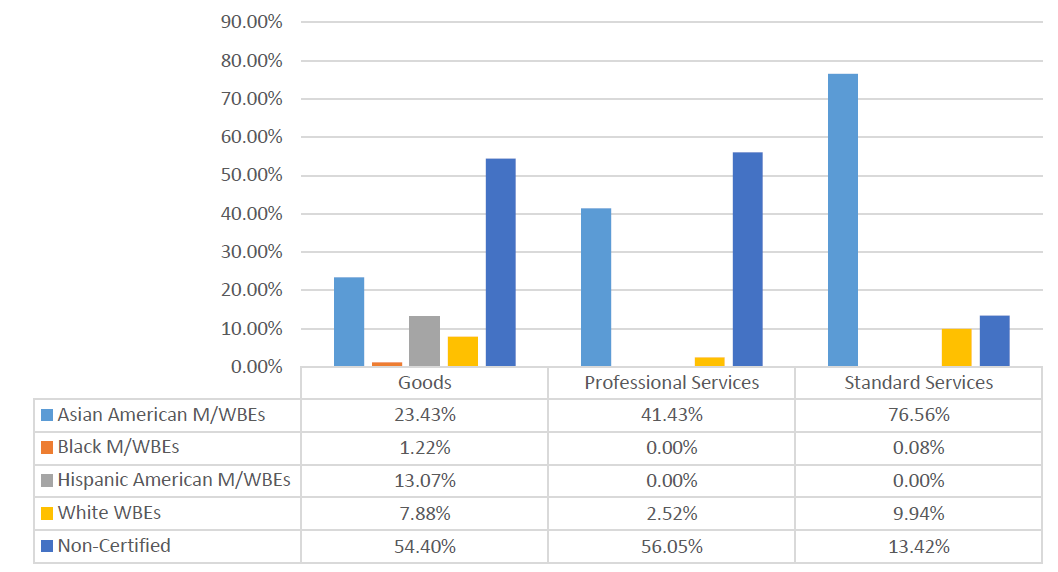

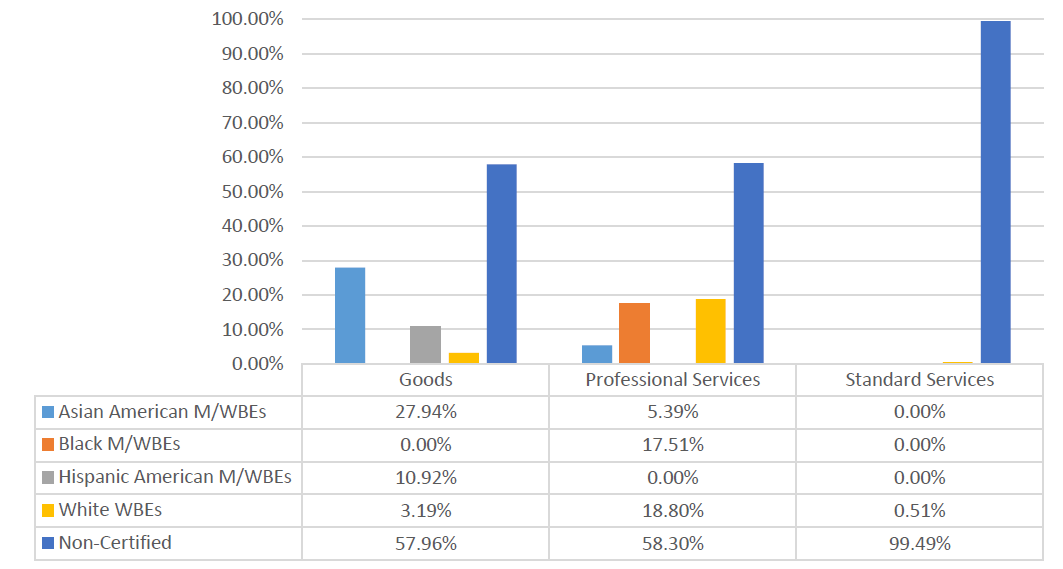

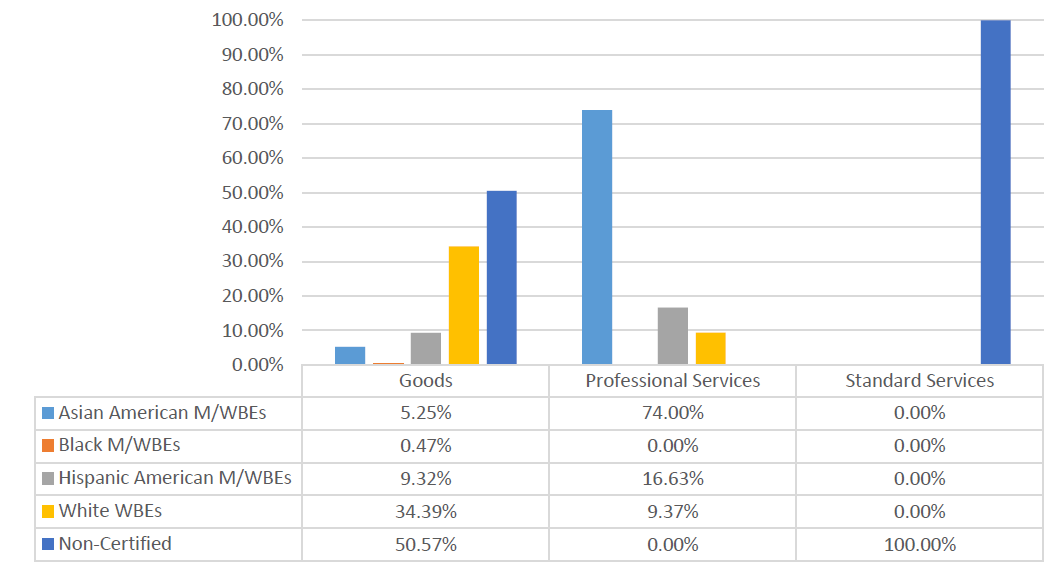

By Industry

M/WBE utilization varies depending on the industry. The construction services and standard services industries see some of the lowest spending and registration values to M/WBEs. Only 7.50% of construction services and 12.20% of standard services prime contract registration value subject to LL 174 participation goals were registered to M/WBEs. Similarly, only 10.80% of prime construction services spending and less than 6.14% of prime standard services spending was with M/WBEs. Additional details analyzing M/WBE utilization at the industry level can be found in the “M/WBE Utilization by Industry” section of this Report.

Table 7: FY23 Value of M/WBE Contracts and POs Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, by Industry

| M/WBE | Non-Certified | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Total Contract and PO Value | % Share of Contract and PO Value | Total Contract and PO Value | % Share of Contract and PO Value |

| Construction[31] | $244,140,108 | 7.50% | $3,010,027,727 | 92.50% |

| Goods <$1 million | $108,509,861 | 63.88% | $61,346,485 | 36.12% |

| Professional Services | $463,911,348 | 21.63% | $1,681,146,490 | 78.37% |

| Standard Services | $111,198,858 | 12.20% | $800,249,022 | 87.80% |

| Grand Total | $927,760,175 | 14.32% | $5,552,769,725 | 85.68% |

The M/WBE prime vendor share of FY23 spending shows similar variations across industries.

Table 8: FY23 Prime Vendor Spend Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, by Industry

| M/WBE | Non-Certified | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Total Value | % Share of Value | Total Value | % Share of Value |

| Construction | $401,936,812 | 10.80% | $3,318,175,322 | 89.20% |

| Goods <$1 million | $111,379,347 | 43.40% | $145,227,630 | 56.60% |

| Professional Services | $366,770,386 | 19.69% | $1,495,804,018 | 80.31% |

| Standard Services | $228,697,563 | 6.14% | $3,498,268,712 | 93.86% |

| Grand Total | $1,108,784,107 | 11.59% | $8,457,475,681 | 88.41% |

It is important to note that these trends look different for subcontracted spending across industries. M/WBEs receive higher shares of subcontracted spending than Non-Certified firms in construction, professional services, and standard services. M/WBEs only receive a very small share of Goods subcontracted spending, as there is little subcontracting in this industry generally.

Table 9: FY23 Subcontractor Spend Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, by Industry

| M/WBE | Non-Certified | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Total Value | % Share of Value | Total Value | % Share of Value |

| Construction | $184,291,683 | 51.48% | $173,696,842 | 48.52% |

| Goods <$1 million | $2,993,891 | 42.85% | $3,992,454 | 57.15% |

| Professional Services | $50,874,280 | 64.59% | $27,886,145 | 35.41% |

| Standard Services | $37,147,293 | 48.50% | $39,449,582 | 51.50% |

| Grand Total | $275,307,147 | 52.91% | $245,025,022 | 47.09% |

M/WBEs are winning more business, but their contracts are for a small fraction of the value of the contracts won by firms owned by white men

In FY23, M/WBEs accounted for 60.32% of the volume of new contract registrations and POs subject to LL 174 participation goals. However, these contracts only account for 9.82% of the respective value.[32]

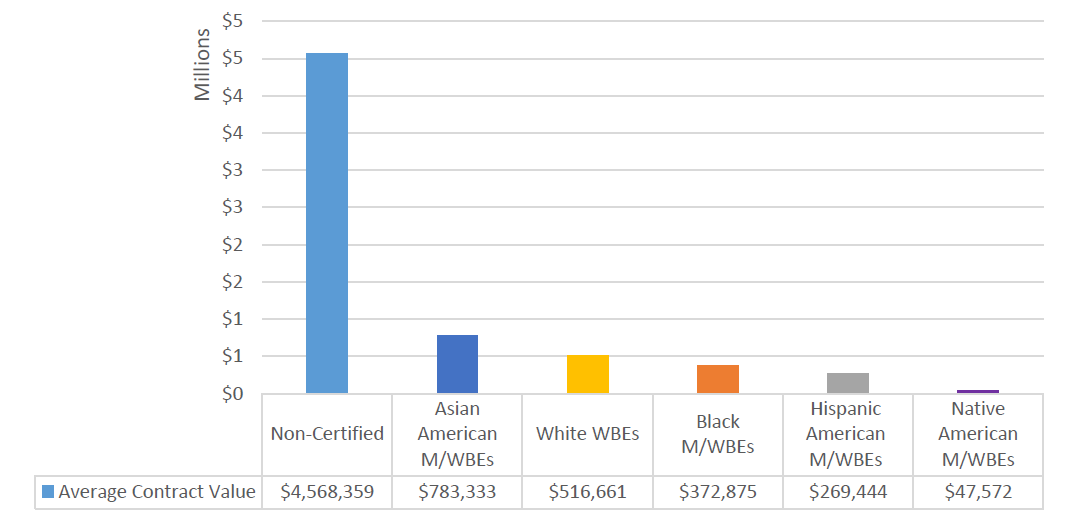

Year-over-year analyses show a key factor contributing to the City’s underutilization of M/WBEs: among FY23 registrations subject to LL 174 participation goals, the average dollar value of a prime contract registered to a M/WBE ($511,000), was approximately 11% of the average dollar value of a prime contract registered to a Non-Certified firm ($4.56 million).[33]

Chart 3: FY23 Average Value of Contracts Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals[34]

Award Method Analyses

A tension exists in the City’s M/WBE procurement: Award methods with agency discretion – such as Micro purchase, Small Purchase, and the M/WBE NCSP method – are more likely to result in a prime contract with an M/WBE; however, these discretionary methods generally result in lower-dollar-value contracts. That said, even within competitive methods – both Competitive Sealed Bid (CSB) and Competitive Sealed Proposal (CSP) – the average contract value for M/WBEs is far lower than for Non-Certified firms.

This analysis also underscores the need for more stringent goal setting and subcontractor tracking and reporting. In FY23, 94.14 % of Negotiated Acquisition contracts were registered to Non-Certified firms. While the basis for using the Negotiated Acquisition method is largely dictated by a limited availability of vendors which therefore makes it difficult to implement policy directives to encourage increased prime contracting, it highlights procurement opportunities where the City could achieve higher M/WBE utilization through subcontracting.

Additional information about each of these procurement methods can be found in Appendix A of this Report.

Table 10: FY23 Contracts by Award Method, Citywide[35]

| Award Method Category | M/WBE | Non-Certified | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts | # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts | |

| CSB | 150 | 23.08% | 500 | 76.92% |

| CSP | 81 | 9.82% | 744 | 90.18% |

| Accelerated Procurement | 9 | 14.06% | 55 | 85.94% |

| Demonstration Project | 0 | 0.00% | 8 | 100.00% |

| Innovative Procurement | 2 | 1.87% | 105 | 98.13% |

| Micropurchase | 24,380 | 18.00% | 111,069 | 82.00% |

| Negotiated Acquisition | 41 | 5.86% | 659 | 94.14% |

| Small Purchase Contracts – General | 1,127 | 25.92% | 3,221 | 74.08% |

| M/WBE NCSP method | 1,042 | 100.00% | 0[36] | 0.00% |

| Grand Total | 26,556 | 18.51% | 116,884 | 81.49% |

All of the major procurement methods result in far less than a third of the contracts going to M/WBEs. While M/WBEs fare better in some discretionary procurement methods that have specified maximum values, those do not yield meaningful spend given the low value of the thresholds. For example, M/WBEs account for 18% of micro-purchase contracts that have a threshold cap of $35,000 for construction and $20,000 for all other procurements.

Even within these lower-value methods, M/WBEs are registering contracts at average values far below the caps. During FY23, the M/WBE NCSP method was capped at a maximum value of $500,000 or $1,000,000. But the average value of a contract registered using this method was only $185,762.

Table 11: FY23 Average Value of Contracts by Award Method, Citywide

| Award Method | M/WBE – Avg Contract Value | Non-Certified – Avg Contract Value |

| CSB | $3,156,492 | $9,581,813 |

| CSP | $5,292,247 | $14,930,265 |

| Accelerated Procurement | $237,915 | $2,988,859 |

| Demonstration Project | $0 | $1,427,562 |

| Innovative Procurement | $980,659 | $1,739,332,847 |

| Micropurchase[37] | $3,715 | $2,858 |

| Negotiated Acquisition | $1,163,580 | $3,001,350 |

| Small Purchase Contracts – General[38] | $32,363 | $28,824 |

| M/WBE NCSP method[39] | $185,762 | $0 |

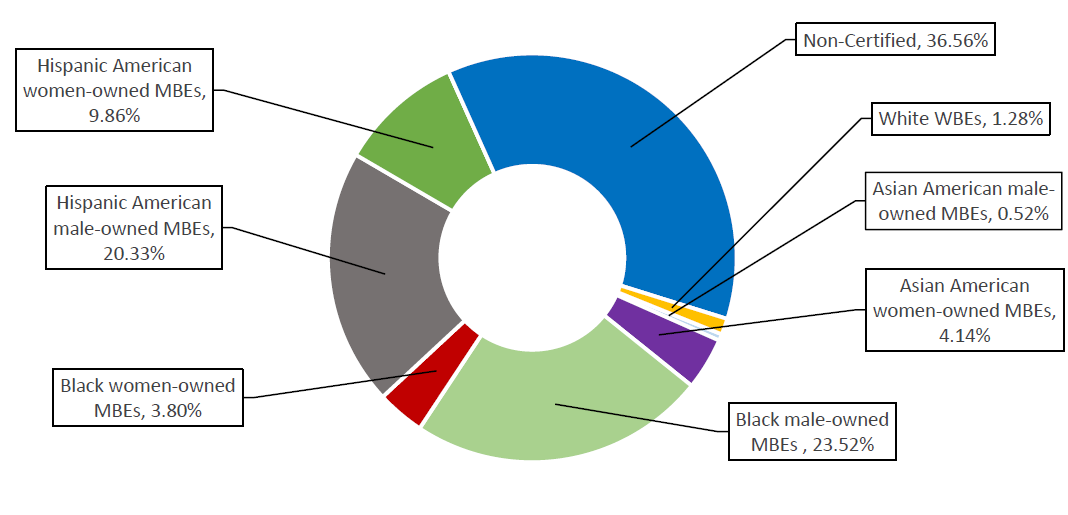

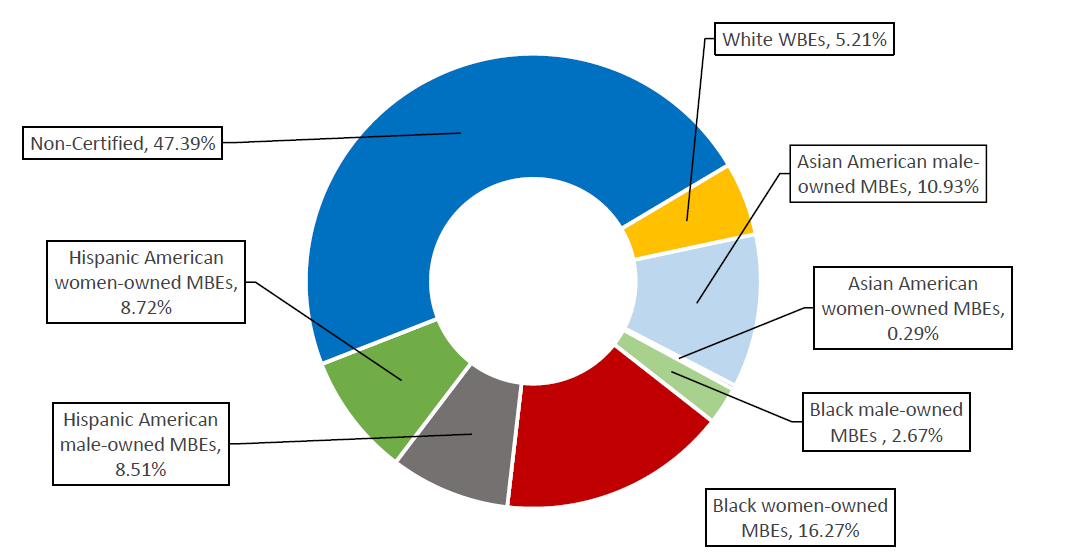

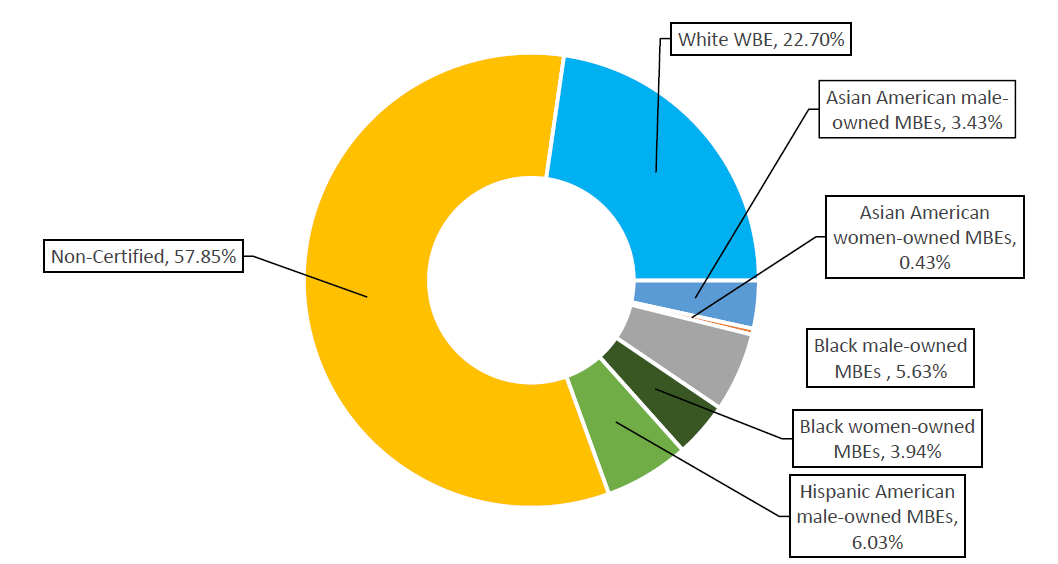

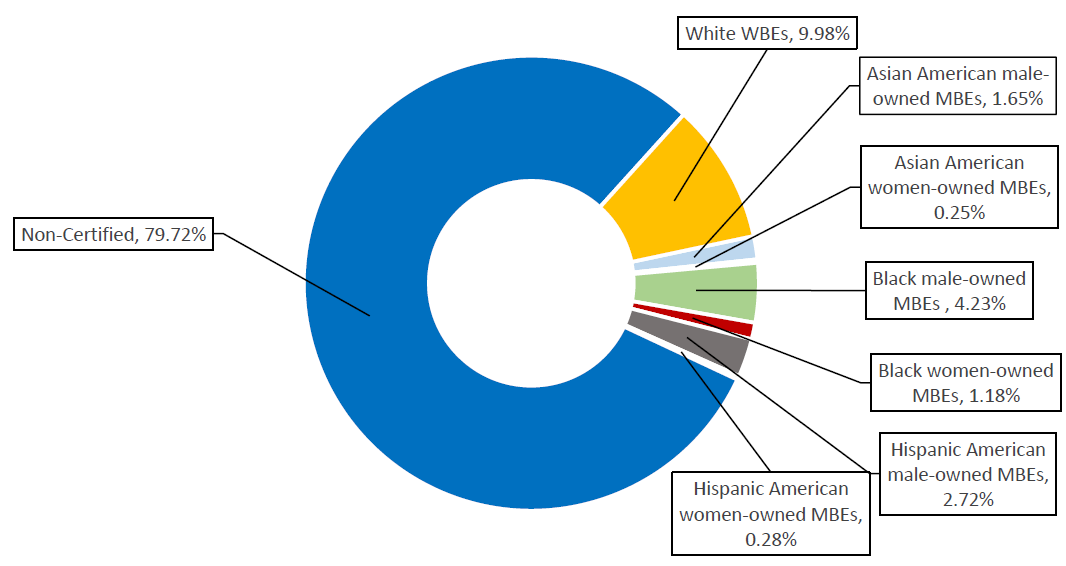

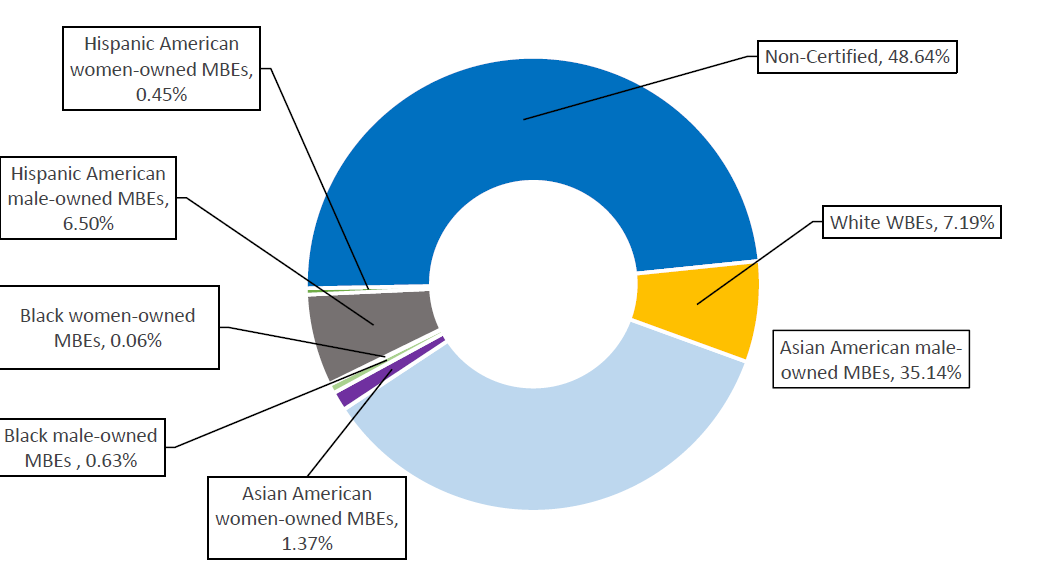

Disaggregated By Race

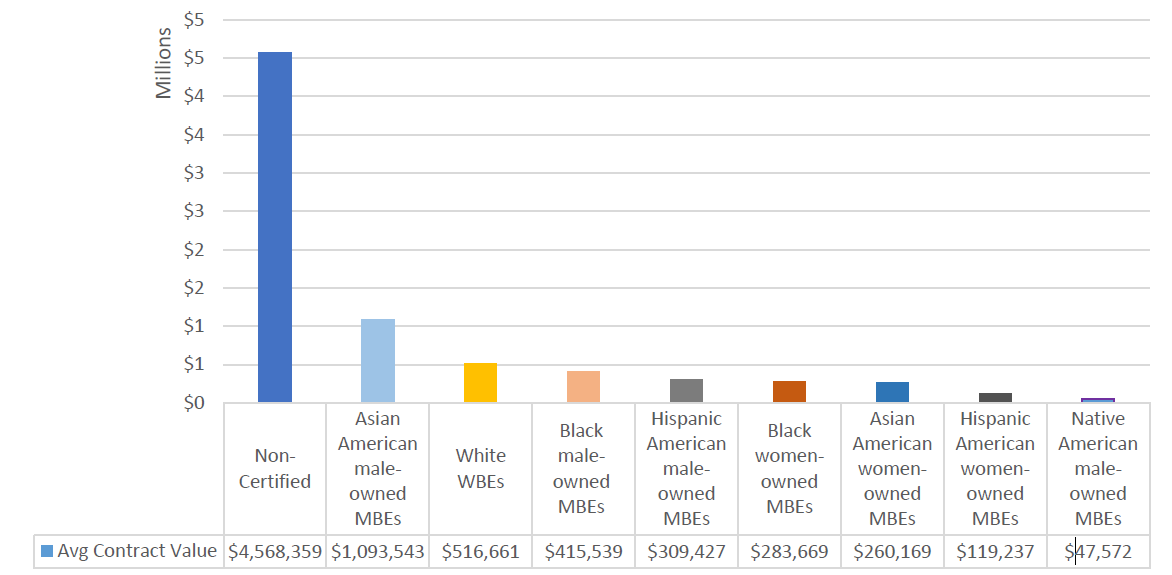

Certain underutilized M/WBE categories earn less lucrative contracts than others. Businesses owned by white women and Asian American males have much higher average values than those owned by Black people, Hispanic people, and Native American people. Though, it is worth noting that the higher average contract value for Asian American M/WBEs is driven by several high-value MMA1 contracts registered to Asian American male-owned MBEs under OTI. As this Report will discuss further in Findings #3, the full value of MMA1 contracts is often underused, if at all.

Chart 4: FY23 Average Value of Contracts Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, by M/WBE Category

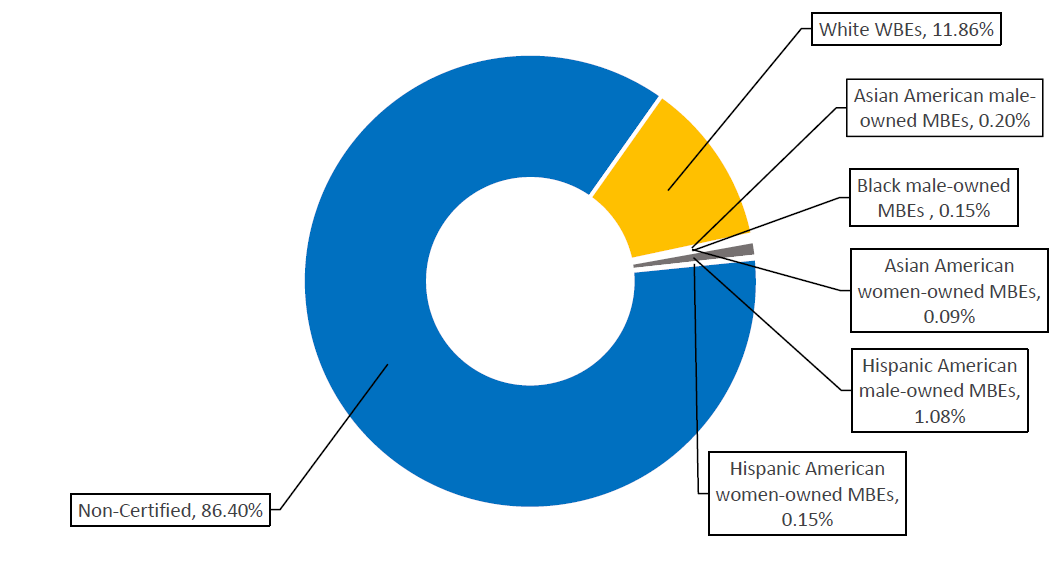

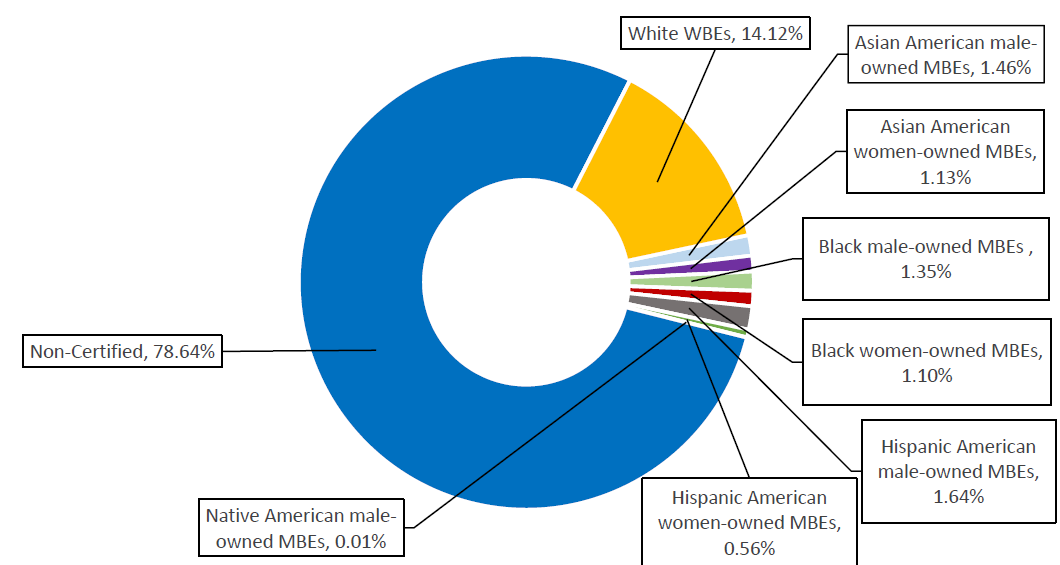

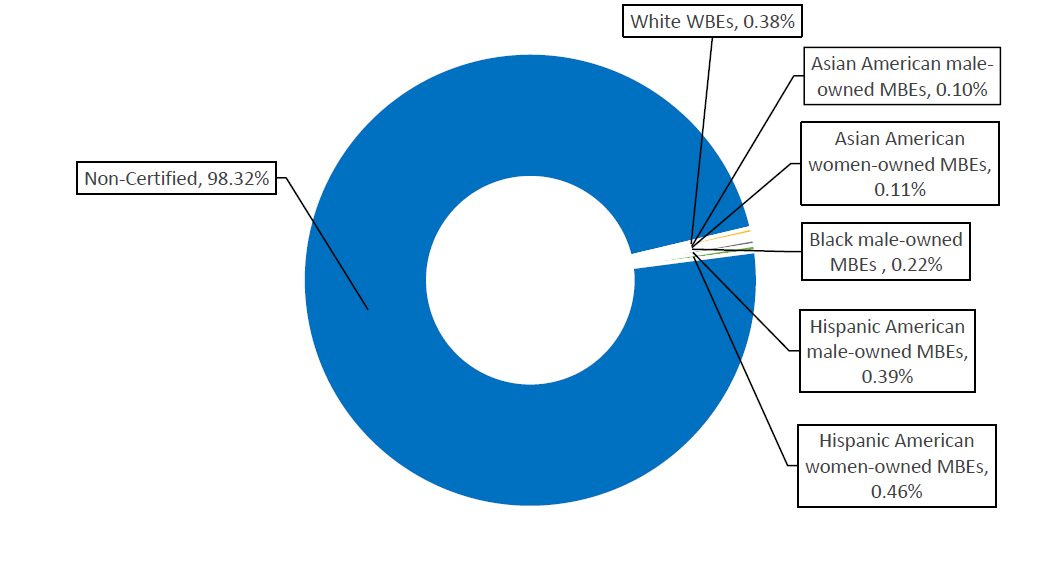

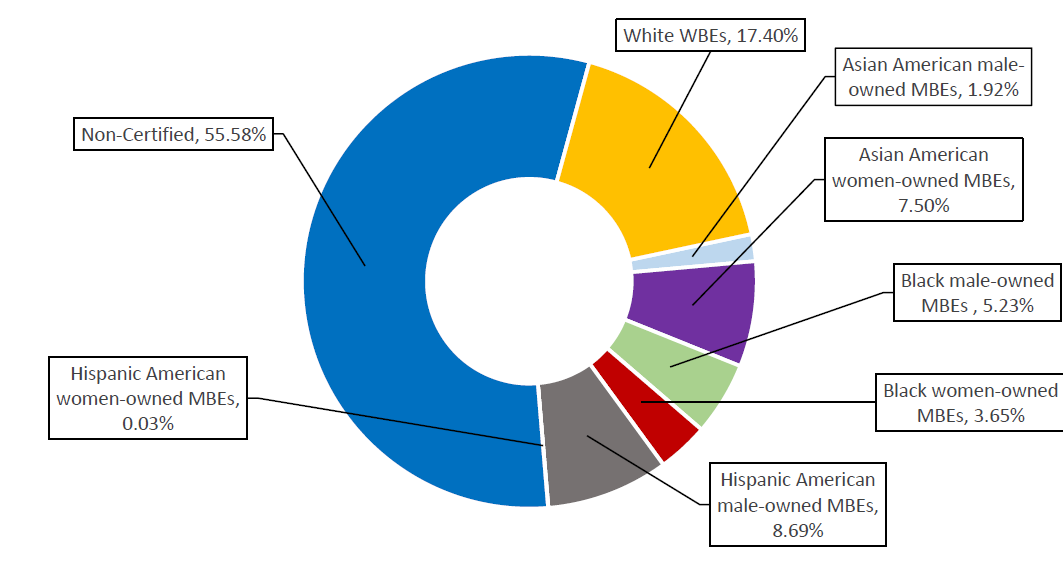

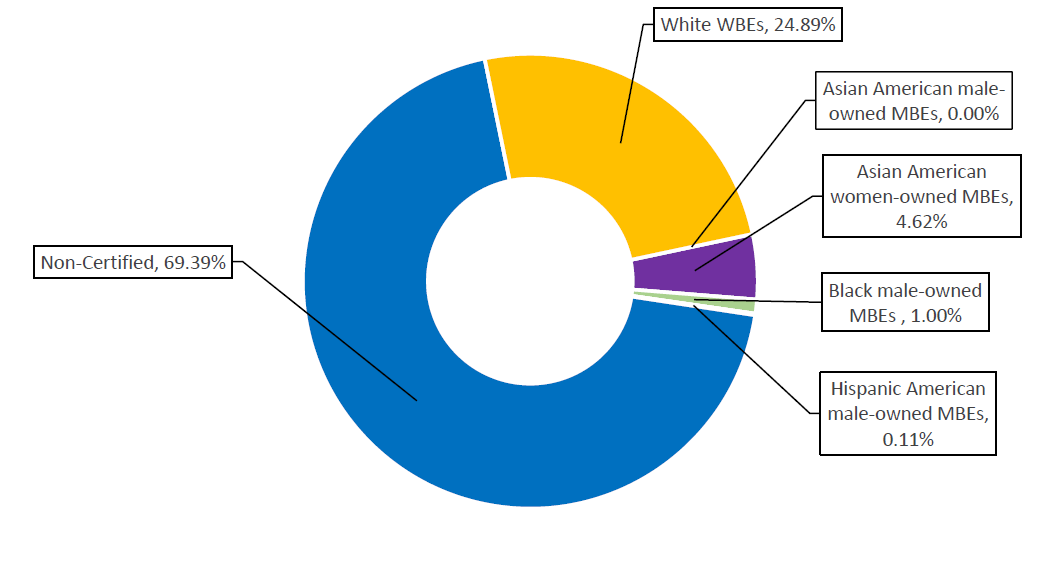

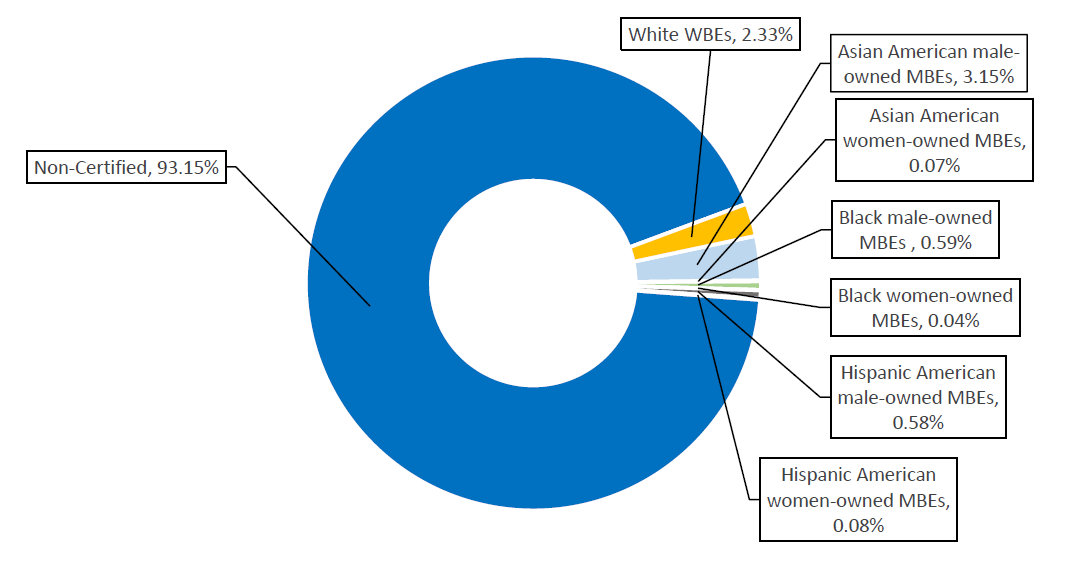

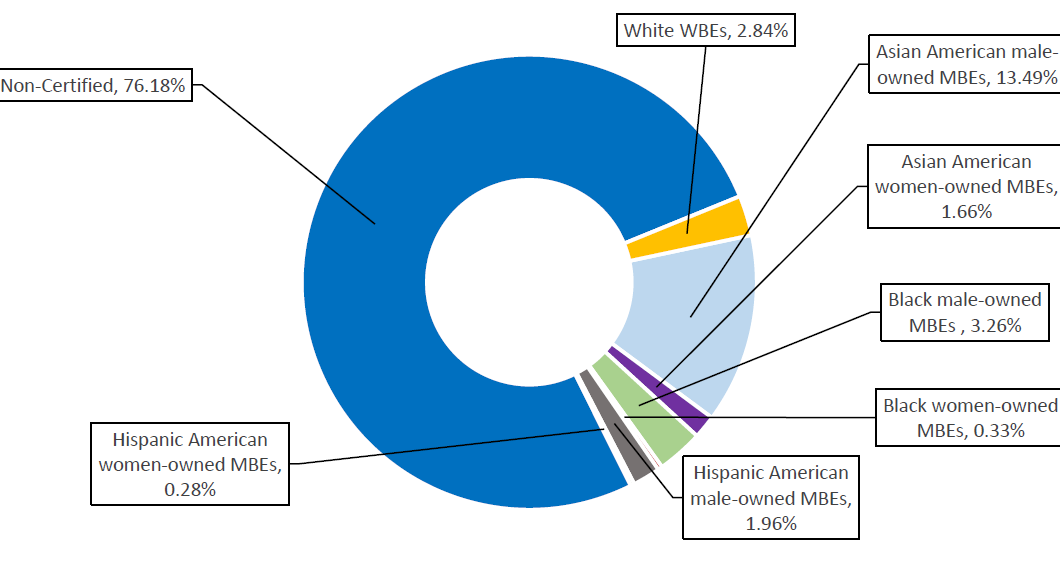

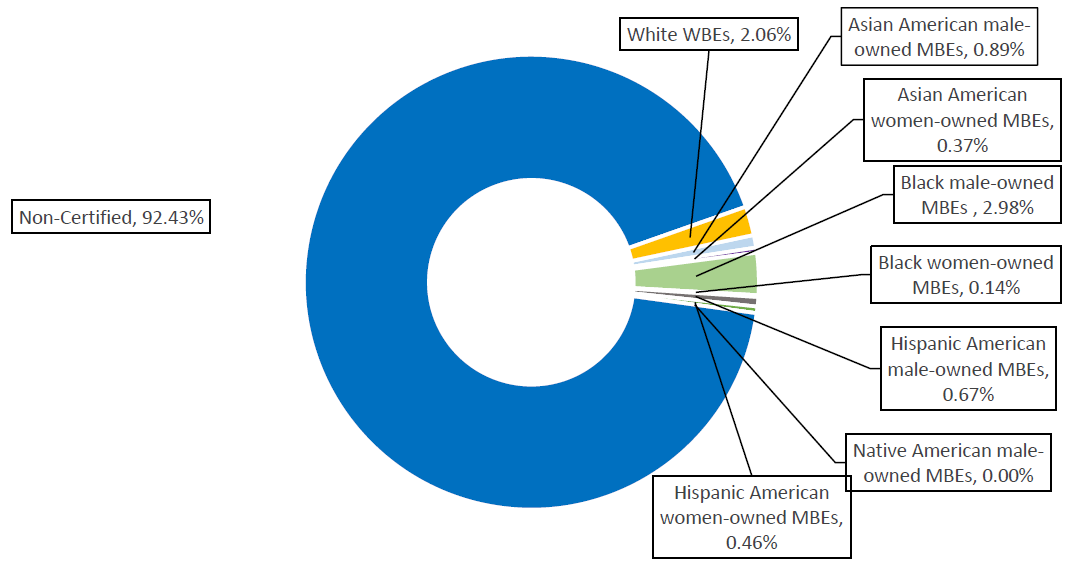

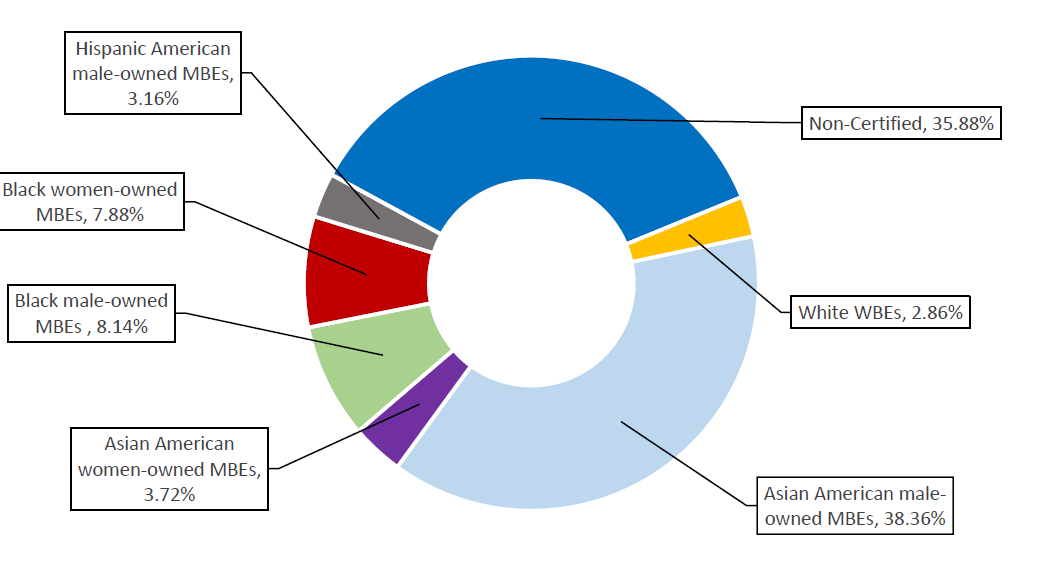

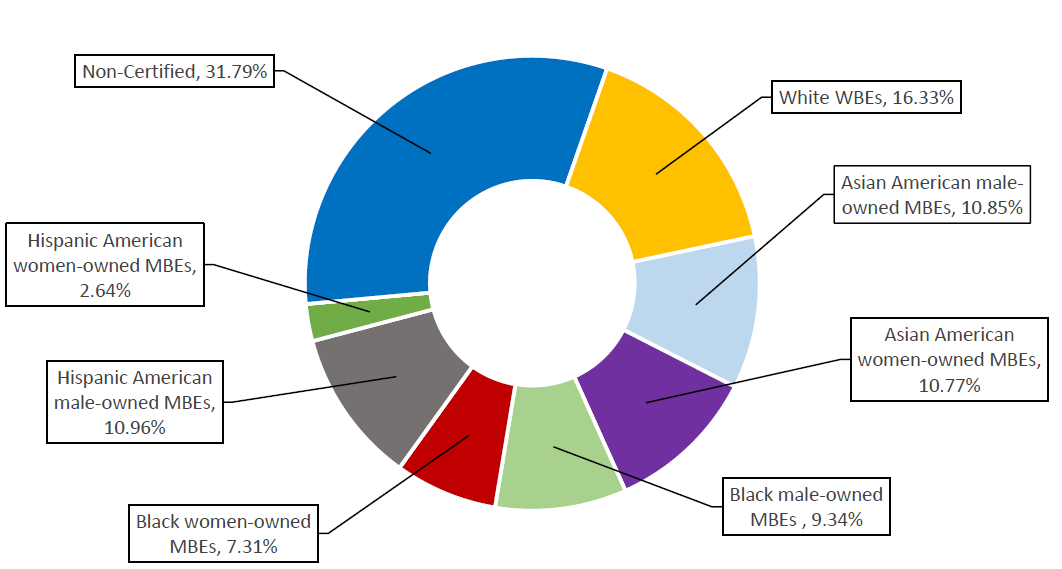

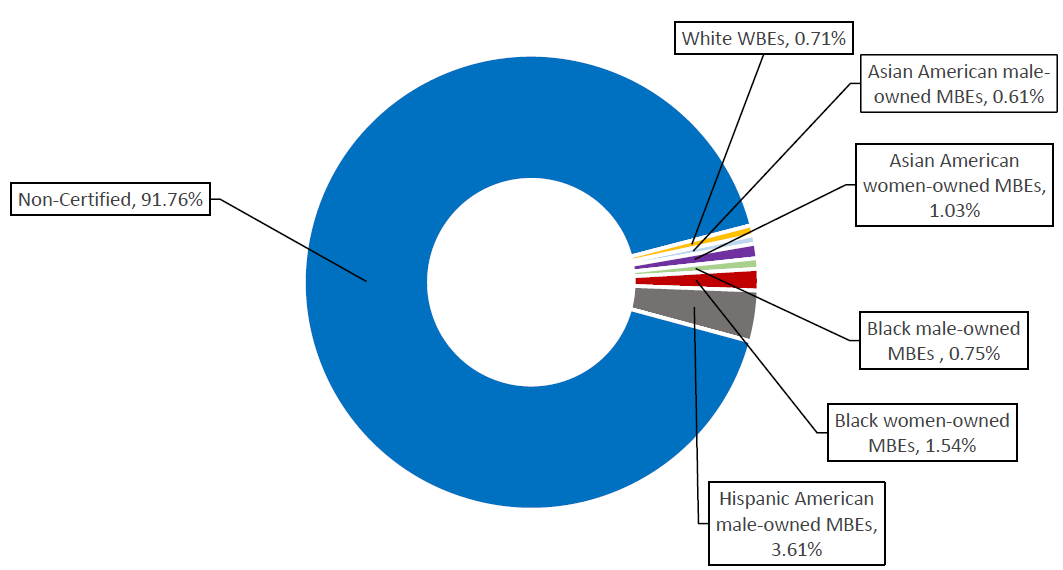

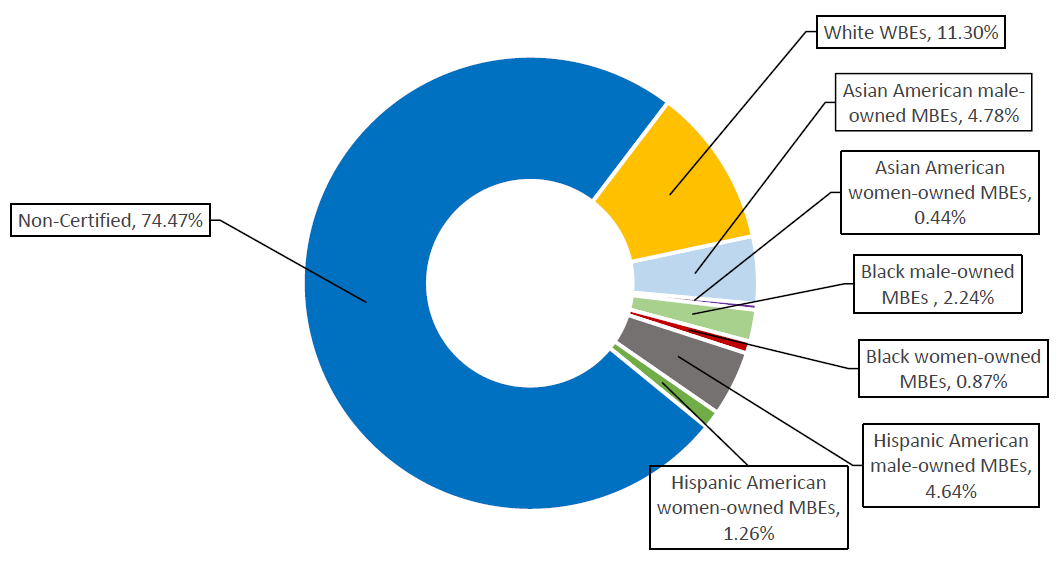

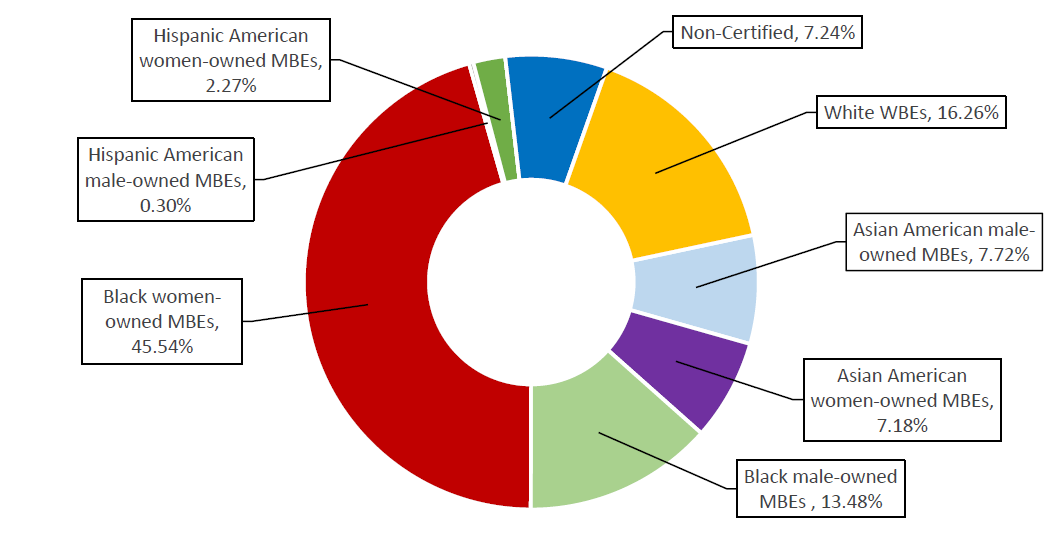

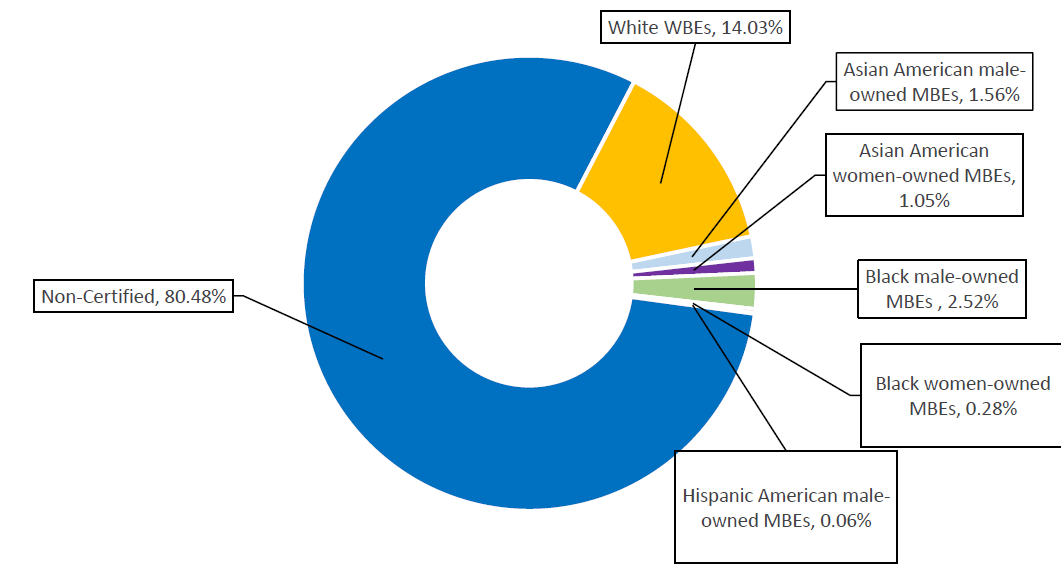

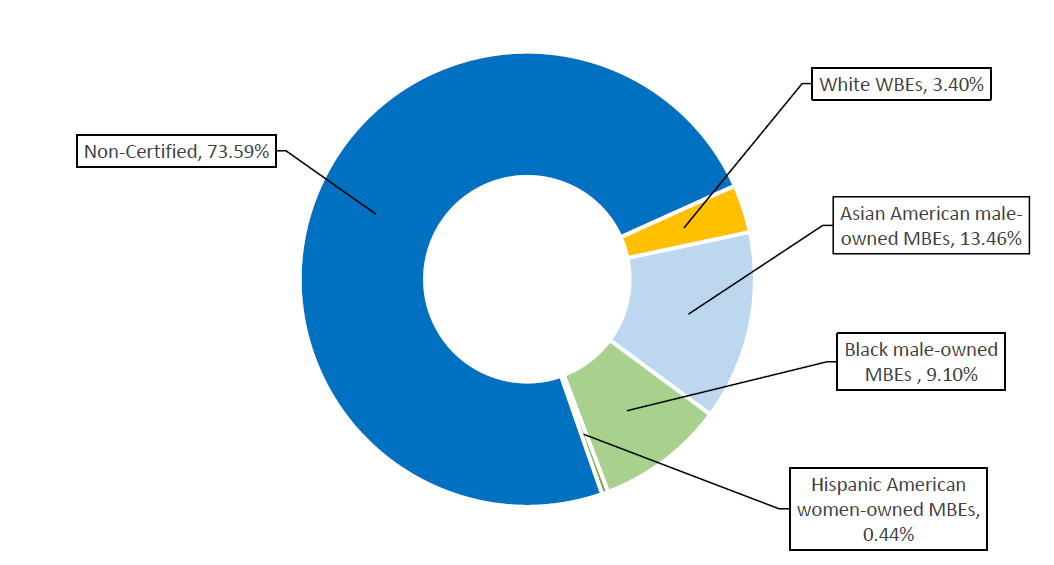

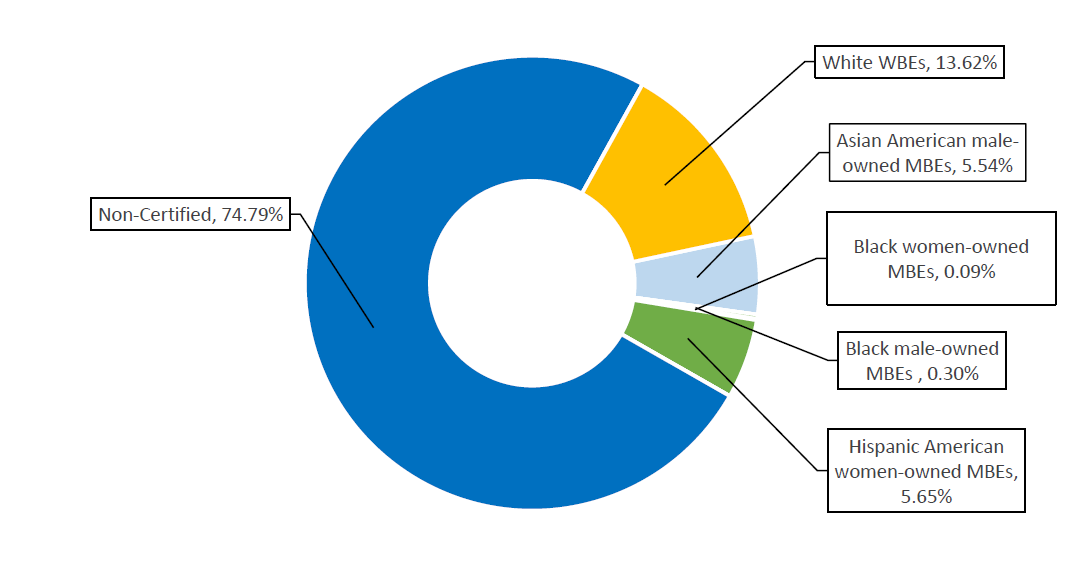

The “disparity within the disparity” remains severe. The value of contracts with Black, Hispanic, or women-of-color owned businesses each hovers at just 1%

The City underutilizes all M/WBEs across all racial and gender categories. Therefore, in order to meaningfully support all M/WBEs, the overall share of the City’s contracting portfolio going to M/WBEs must be increased. Otherwise, it will continue to assess mere pennies across M/WBEs.

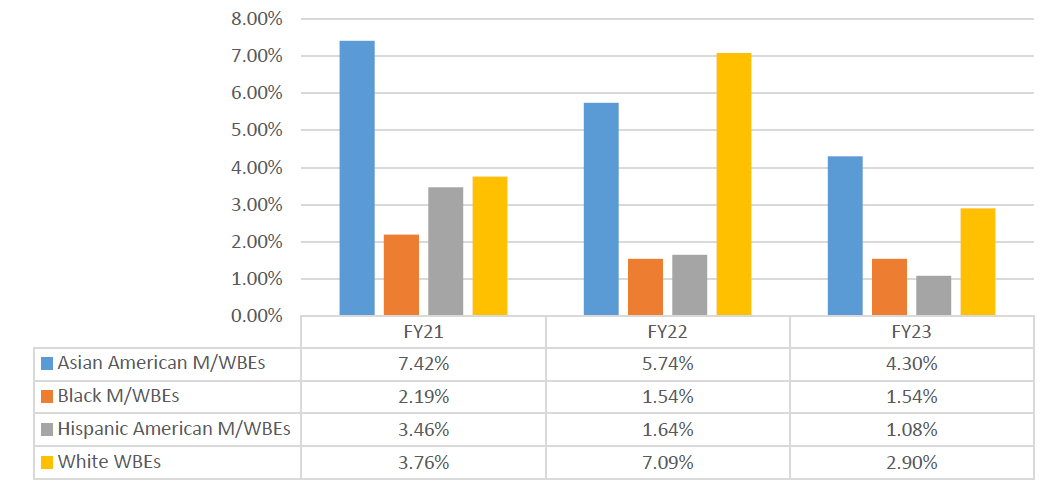

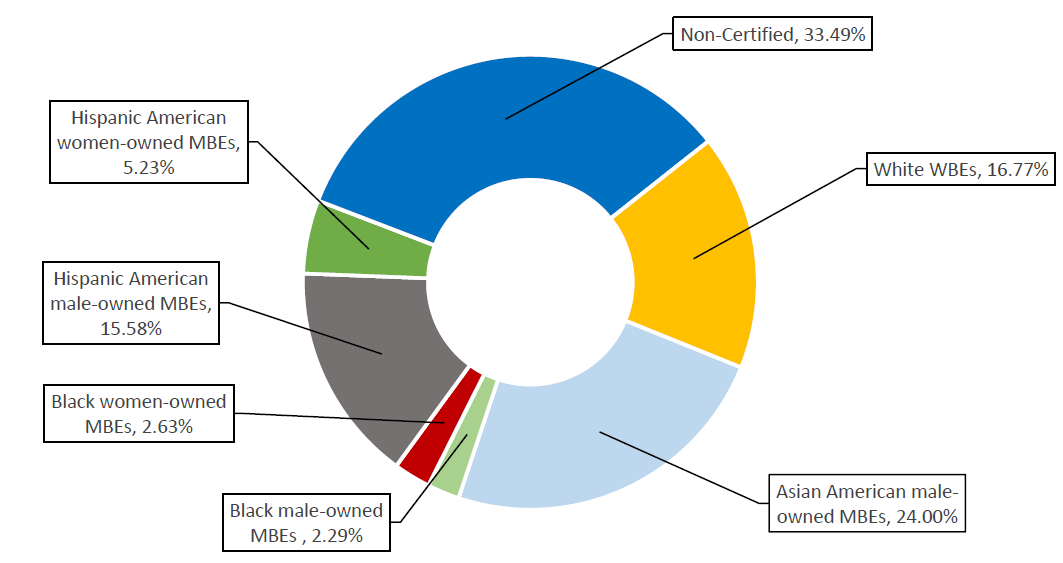

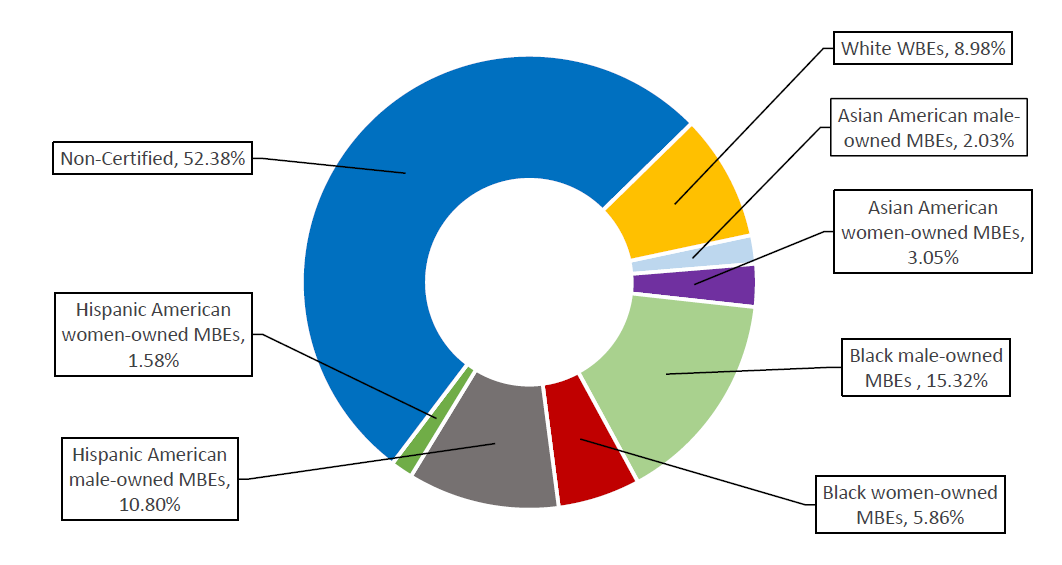

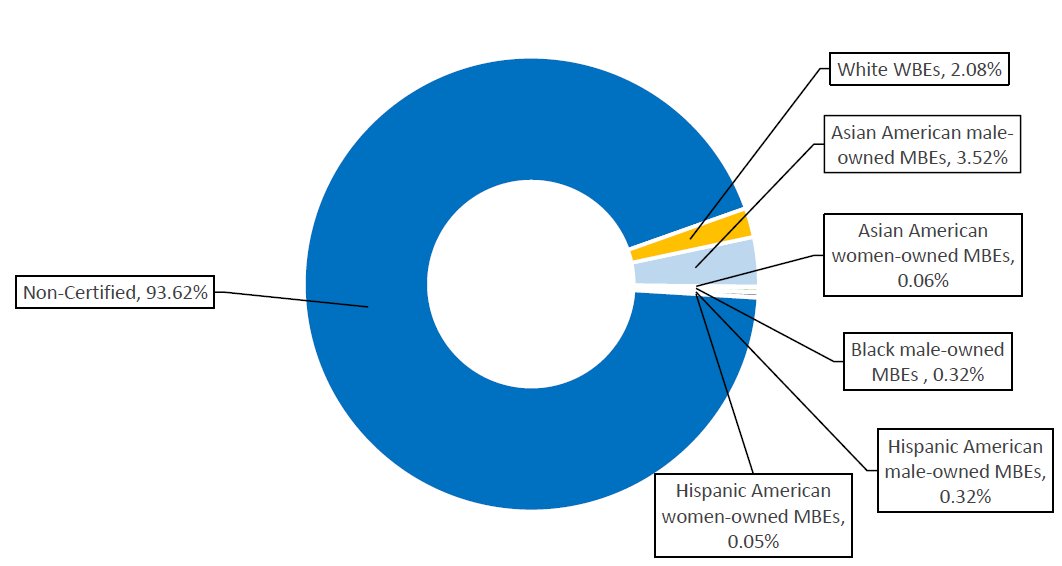

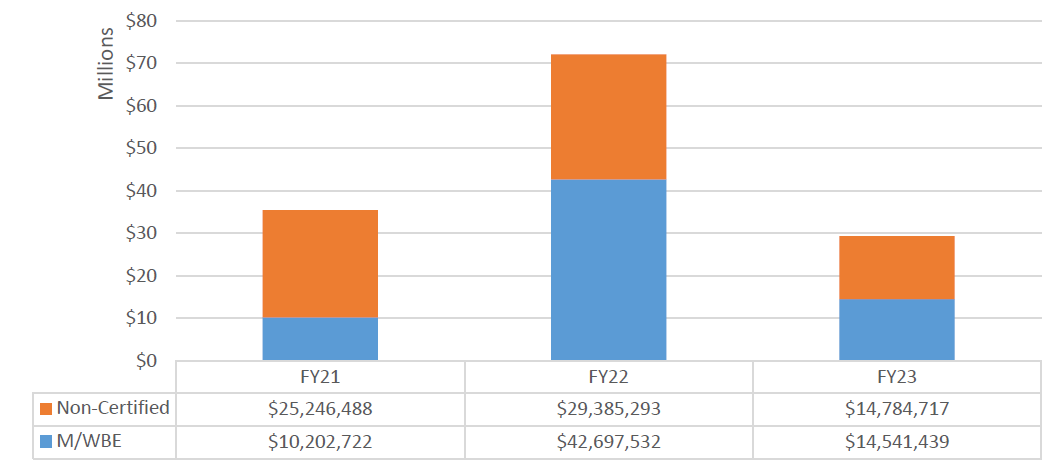

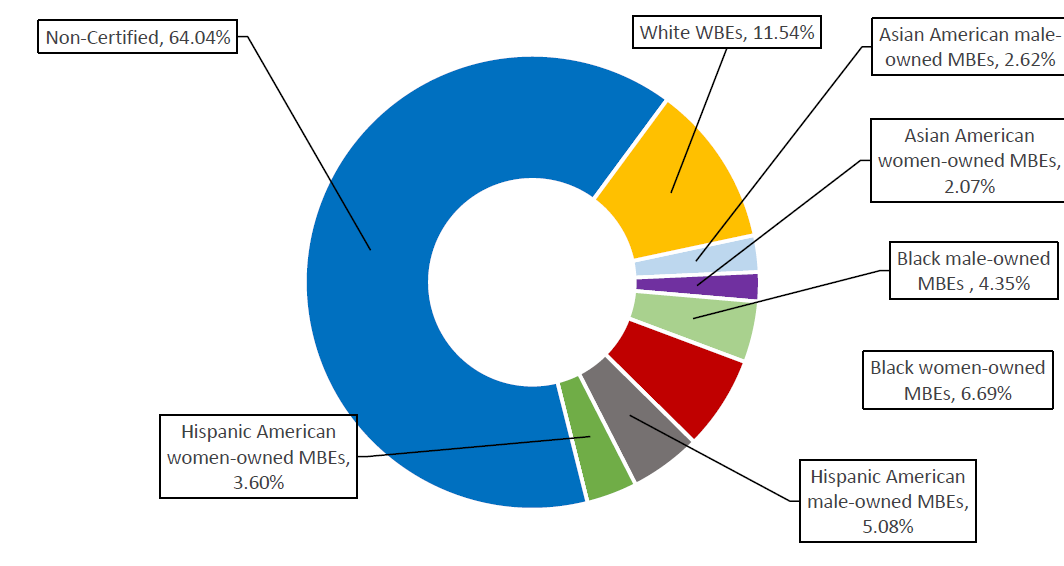

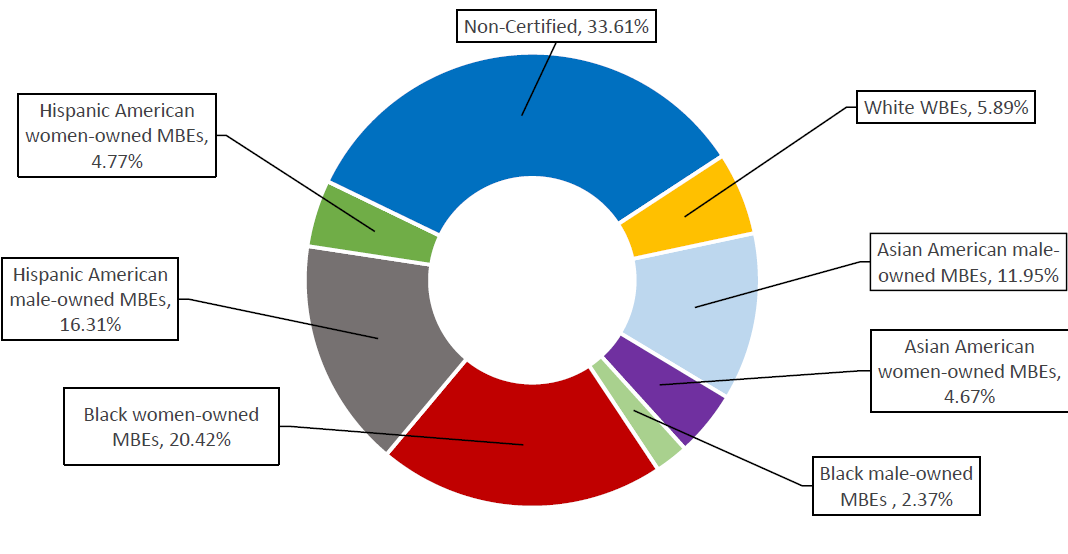

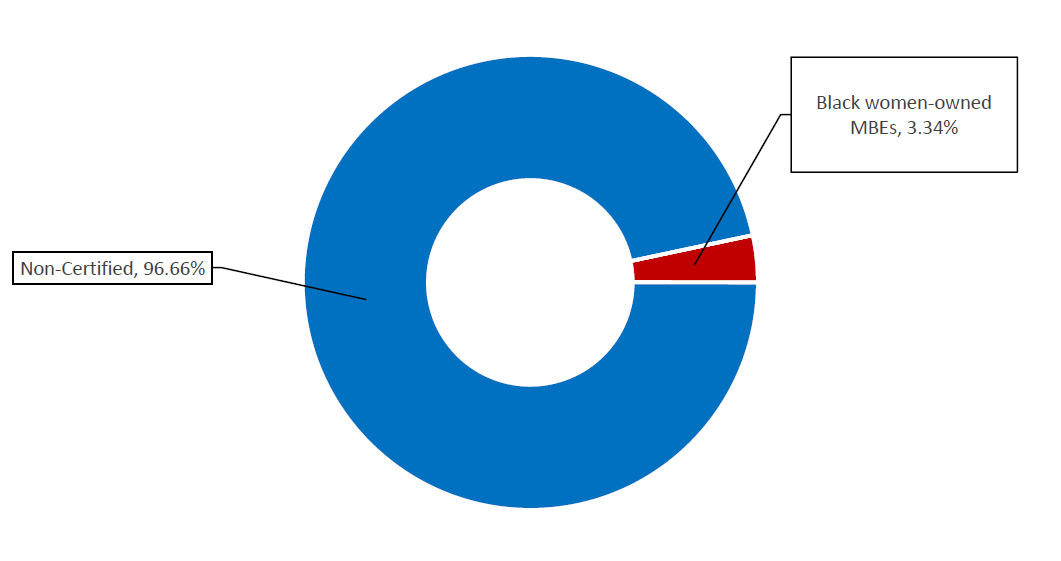

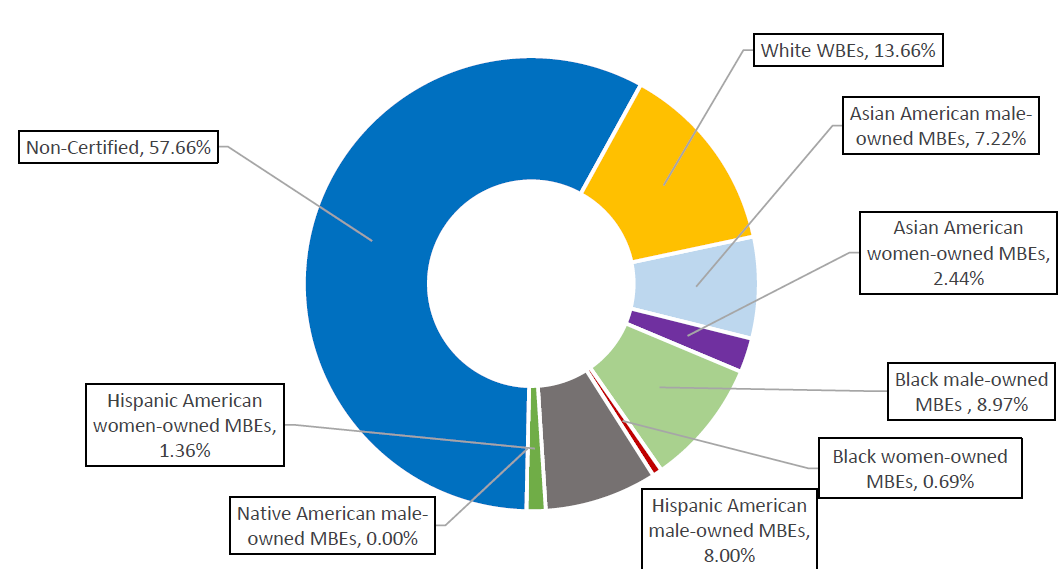

When there is utilization within the M/WBE community, the data reveals that certain M/WBE categories are positively impacted less successfully. Only 1.16% of the value contracts and POs subject to LL 174 participation goals were registered to Black M/WBEs, and only 0.96% to Hispanic M/WBEs.

Overall, the City’s utilization of MBEs owned by women is significantly less than the low utilization of MBEs owned by males. Within each racial category, male certified firms consistently represent larger shares of the counts and value of registered contracts and POs. Male-owned MBEs account for nearly 8 times (11,244) the count of registered contracts and POs than women-owned MBEs (1,465). Only 10.52% of the value of contracts and POs subject to LL 174 that were registered to M/WBEs were registered to MBEs owned by women.

In a completely lone state, the City remains largely unsuccessful in contracting with businesses owned by Native Americans. The SBS Online Directory of Certified Businesses (“SBS Directory”) only includes 3 firms certified as Native American WBEs of which none had a contract or PO registered since FY21. [40]

Table 12: FY23 Contracts and POs Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, by M/WBE Category and Gender

| M/WBE Category | # of LL Contracts and POs | % Share of LL Contracts and POs | Total LL Contract and PO Value | % Share of LL Contract and PO Value | % Share of All M/WBE LL Value |

| Asian American male-owned MBEs | 9,237 | 33.48% | $357,149,048 | 3.77% | 38.37% |

| Asian American women-owned MBEs | 776 | 2.81% | $50,593,556 | 0.53% | 5.44% |

| Black male-owned MBEs | 857 | 3.11% | $109,563,850 | 1.16% | 11.77% |

| Black women-owned MBEs | 368 | 1.33% | $36,498,152 | 0.39% | 3.92% |

| Hispanic American male-owned MBEs | 1,145 | 4.15% | $91,243,143 | 0.96% | 9.80% |

| Hispanic American women-owned MBEs | 321 | 1.16% | $10,782,402 | 0.11% | 1.16% |

| Native American male-owned MBEs | 5 | 0.02% | $150,509 | 0.00% | 0.02% |

| Native American women-owned MBEs | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0% |

| White WBEs | 3,932 | 14.25% | $274,766,943 | 2.90% | 29.52% |

| M/WBE ALL (Excluding Non-Certified) | 16,641 | 60.32% | $930,747,603 | 9.82% | 100.00% |

| Non-Certified | 10,947 | 39.68% | $8,543,566,158 | 90.18% | N/A |

| Grand Total | 27,588 | 100.00% | $9,474,313,761 | 100.00% | N/A |

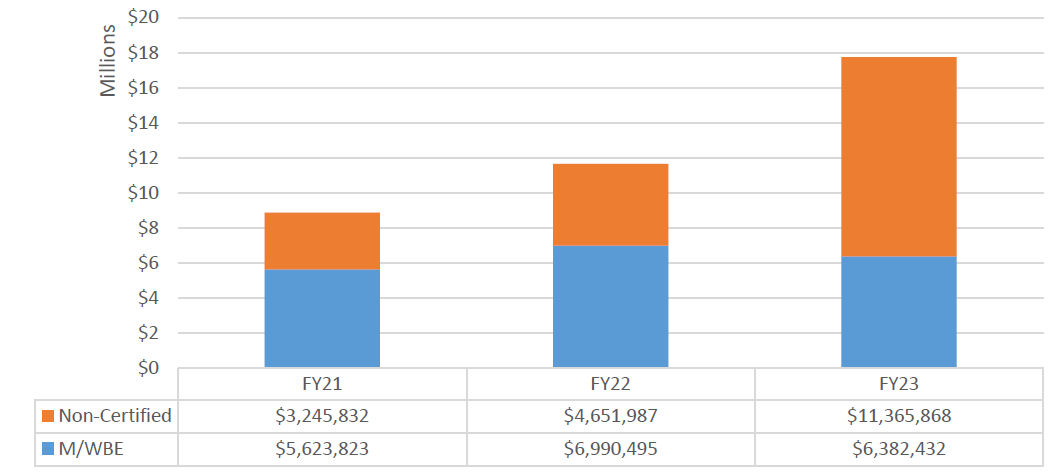

Chart 5: Value of Contracts and POs Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, by M/WBE Category, FY21-23[41]

Table 13: FY23 M/WBE Contracts and POs Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, as a Share of Total M/WBE Contracts, by M/WBE Category

| M/WBE Category | # of Contracts and POs | % of M/WBE Contracts and POs | Total Value | % Share of M/WBE value | % Share of All LL Value |

| Asian American M/WBEs | 10,013 | 60.17% | $407,742,604 | 43.81% | 4.30% |

| Black M/WBEs | 1,225 | 7.36% | $146,062,002 | 15.69% | 1.54% |

| Hispanic American M/WBEs | 1,466 | 8.81% | $102,025,546 | 10.96% | 1.08% |

| Native American M/WBEs | 5 | 0.03% | $150,509 | 0.02% | 0.00% |

| White WBEs | 3,932 | 23.63% | $274,766,943 | 29.52% | 2.90% |

| Grand Total | 16,641 | 100.00% | $930,747,603 | 100.00% | 9.82% |

These trends are true in analyzing both contract registrations and spend data – though, Black M/WBEs received an even smaller portion of prime spending in comparison to other M/WBE categories.

Table 14: FY23 Prime Spending Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, by M/WBE Category

| M/WBE Category | Total Spend | % Share of Total LL 174 Spending | % Share of Total M/WBE Spending |

| Asian American M/WBE | $461,341,167 | 3.91% | 41.11% |

| Black M/WBEs | $99,820,024 | 0.85% | 8.90% |

| Hispanic American M/WBEs | $247,067,825 | 2.09% | 22.02% |

| Native American M/WBEs | $19,976 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| White WBEs | $313,861,719 | 2.66% | 27.97% |

| Non-Certified | $10,676,634,838 | 90.49% | N/A |

| Grand Total | $11,798,745,549 | 100.00% | 100% |

As noted earlier in this Report, Asian American male-owned MBEs and white women-owned WBEs have higher average contract values compared to the remaining M/WBE categories. Excepting Native American M/WBEs, women-owned MBEs consistently have lower average contract values than their male counterparts within racial categories.

Chart 6: FY23 Average Value of Contracts Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, by Race and Gender

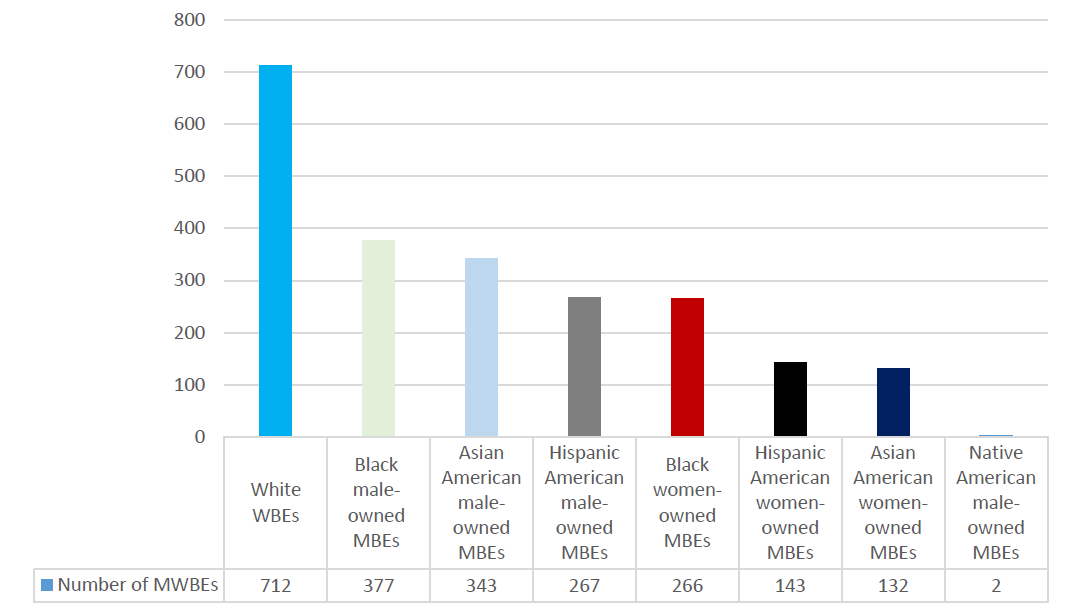

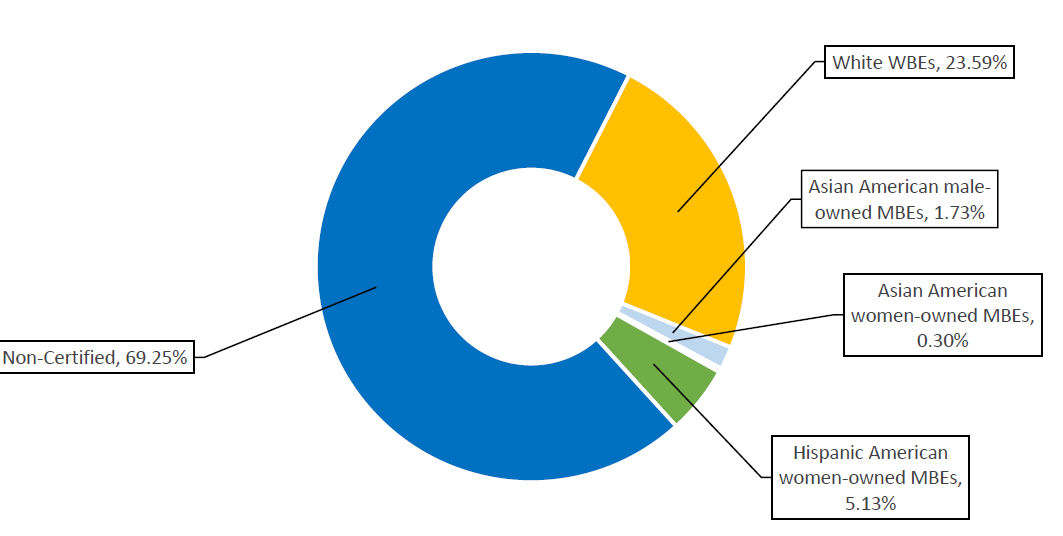

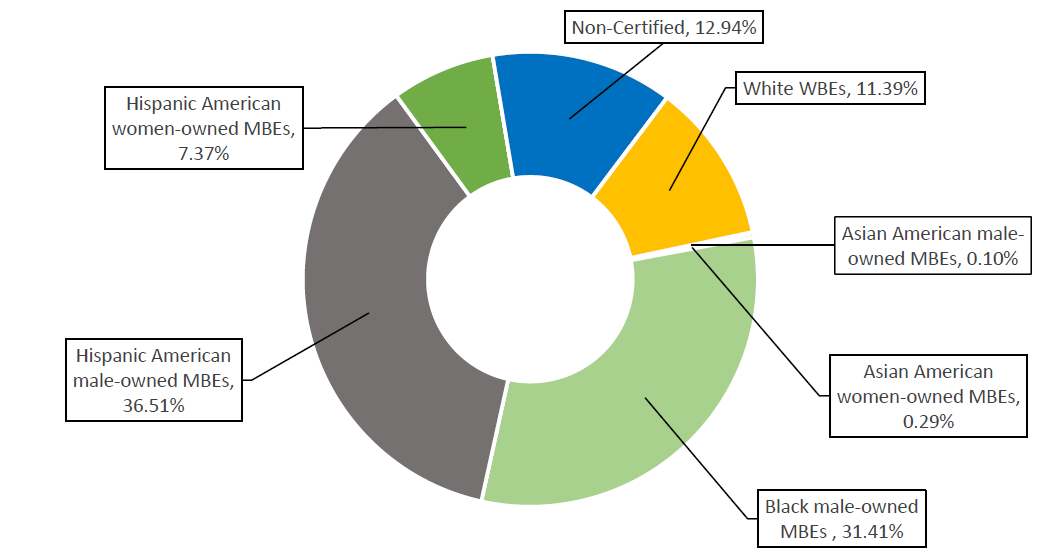

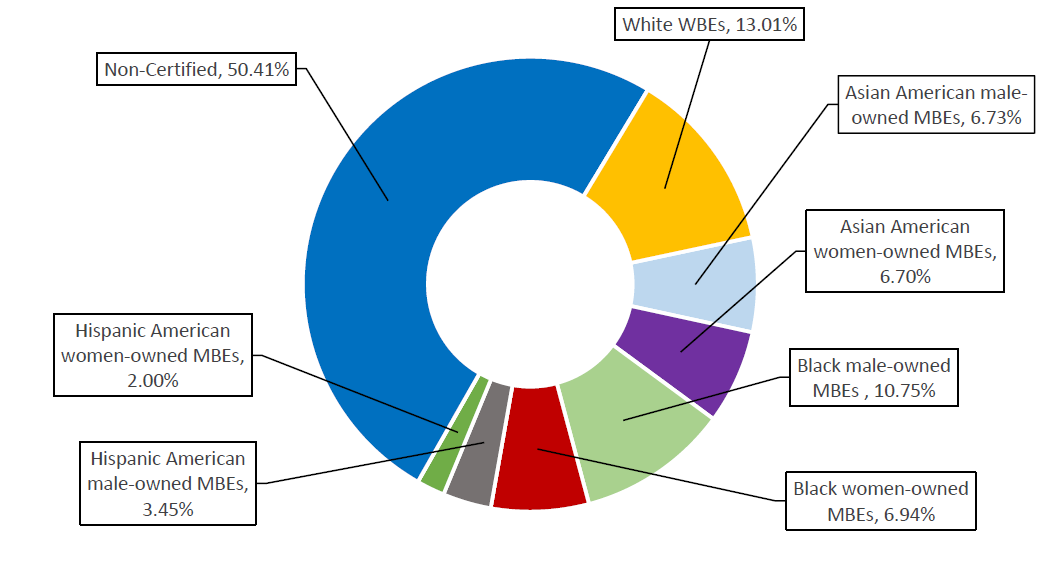

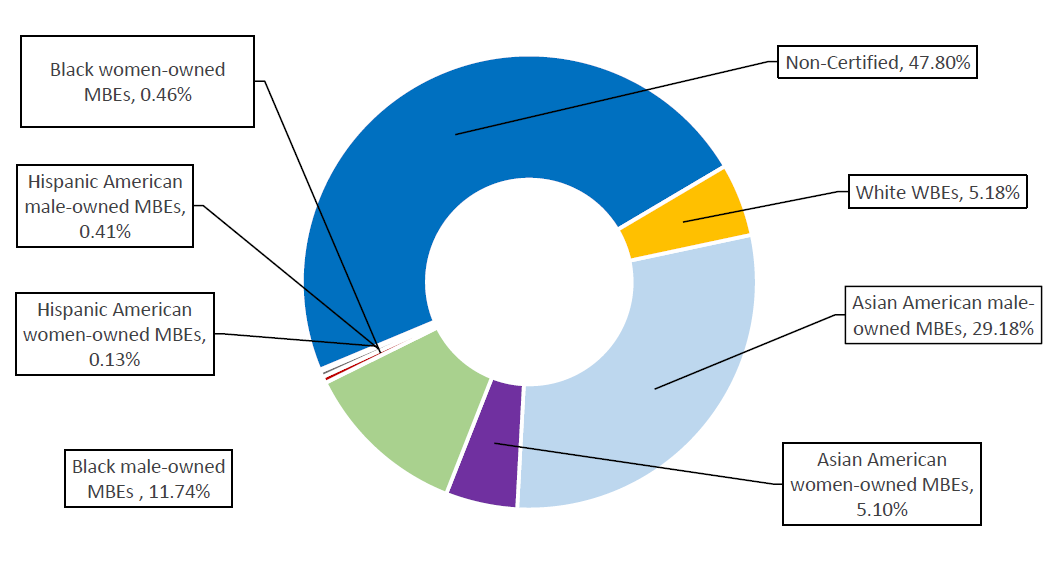

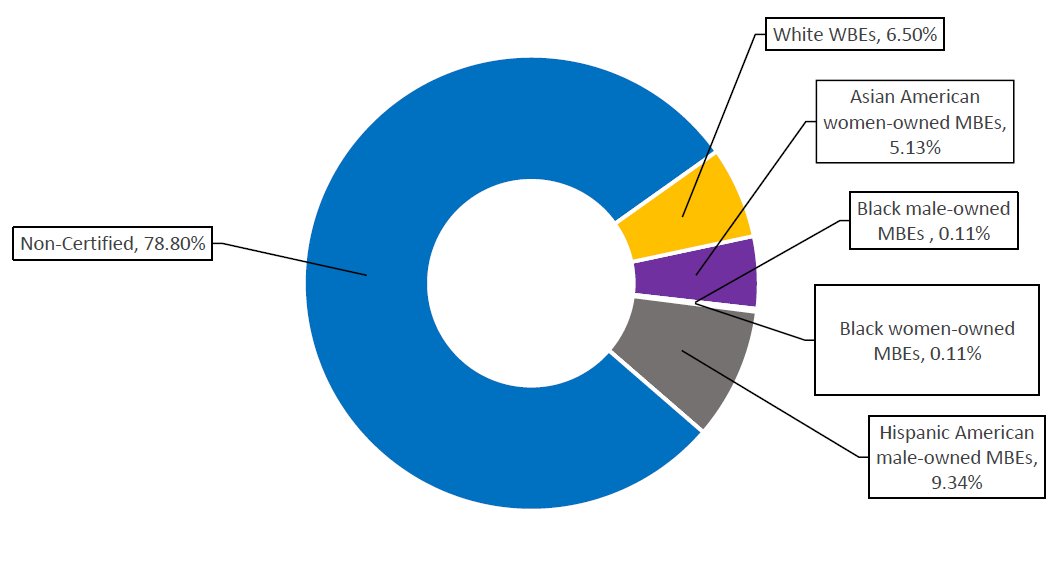

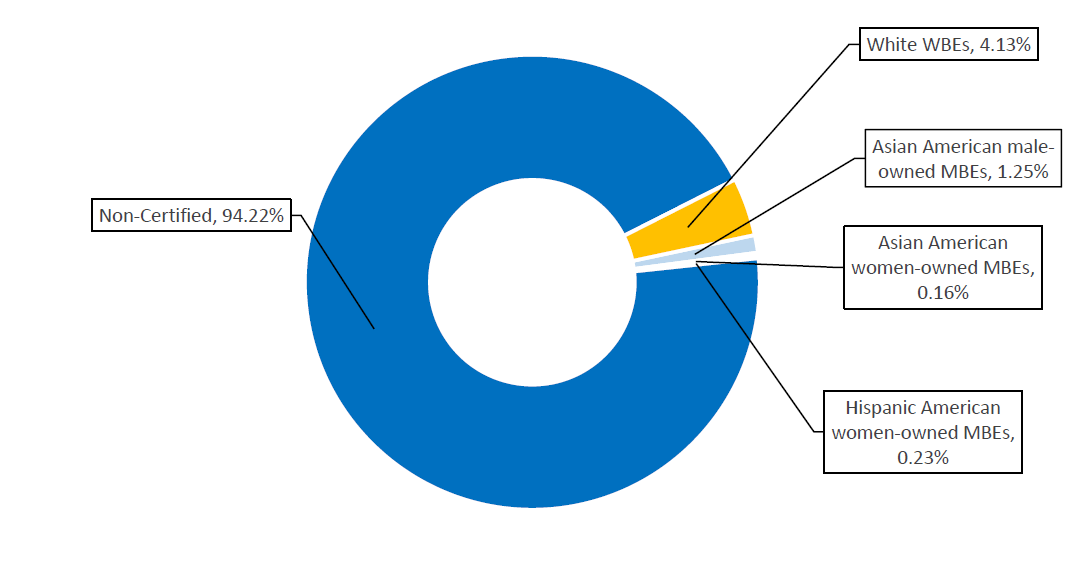

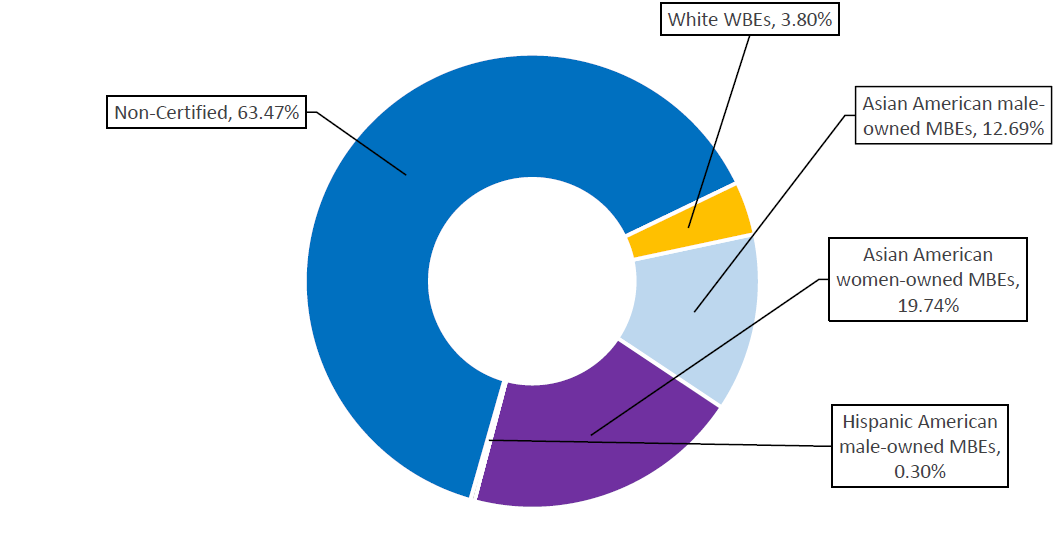

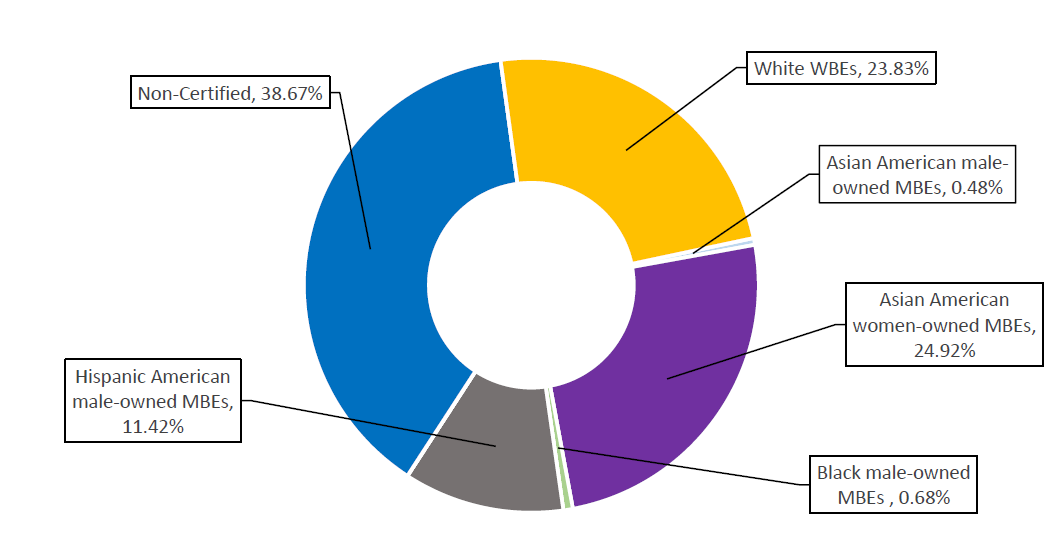

Most M/WBEs don’t benefit from City contracting

As of June 30, 2023 there were 10,992 City-certified M/WBEs in the SBS Directory. 2,242 of these certified M/WBEs entered a new contract, subcontract, or PO with the City in FY23. Though this is the highest number of unique M/WBEs with a new registration in any year on record, this still only represents 20% of all certified M/WBEs. White WBEs made up the largest share of vendors with a new contract, subcontract, or PO in FY23.

Table 15: Unique M/WBEs with New Prime Contracts, POs, or Subcontracts, FY21-23

| M/WBE Category | FY21 | FY22 | FY23 |

| Asian American male-owned MBEs | 305 | 344 | 343 |

| Asian American women-owned MBEs | 110 | 150 | 132 |

| Black male-owned MBEs | 268 | 324 | 377 |

| Black women-owned MBEs | 173 | 244 | 266 |

| Hispanic American male-owned MBEs | 221 | 244 | 267 |

| Hispanic American women-owned MBEs | 104 | 136 | 143 |

| Native American male-owned MBEs | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Native American women-owned MBEs | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| White WBEs | 679 | 733 | 712 |

| All Male-Owned MBEs (Not Reflected in “Total”) | 796 | 915 | 989 |

| All Women-Owned MBEs (Not Reflected in “Total”) | 387 | 530 | 541 |

| Total | 1,862 | 2,178 | 2,242 |

Chart 7: FY23 Unique M/WBEs with New Prime Contracts, Purchase Orders, or Subcontracts

More than half of contracts awarded to M/WBEs are registered late

In FY23, over 61% of new contracts with M/WBEs were registered retroactively, after the beginning of their contract term, compared with the 65.94% rate for procurement contracts citywide. This forces M/WBEs to advance funds out of limited working capital, to seek to borrow in order to start the project, or to delay work. In some circumstances, it means M/WBEs are providing City services without any guarantee of pay. This is especially challenging given that average M/WBE contract sizes are smaller, and that many M/WBEs are small businesses that lack sufficient working capital and may have a more challenging time borrowing from traditional lending institutions.

Table 16: FY23 New M/WBE Contract Registrations by Retroactive Category, Citywide

| Retroactive Category | # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts | Total Contract Value | % Share of Contract Value |

| On Time or Early | 1,110 | 38.73% | $891,021,844 | 44.24% |

| Late – Within 30 Days | 655 | 22.85% | $331,736,207 | 16.47% |

| Later – Between 31-180 Days | 925 | 32.27% | $590,567,782 | 29.32% |

| Very Late – Between 181-365 Days | 126 | 4.40% | $159,695,276 | 7.93% |

| Latest – More than 1-Year | 50 | 1.74% | $41,024,601 | 2.04% |

| Grand Total | 2,866 | 100.00% | $2,014,045,710 | 100.00% |

Retroactivity rates are even higher for contracts registered using the M/WBE NCSP method, despite the fact that this Office has delegated authority to allow agencies, with appropriate oversight measures, to self-register contracts procured pursuant to this method. In doing so, M/WBEs that have been awarded contracts procured by agencies through this method do not wait up to 30 calendar days for their contract to be reviewed and registered by this Office which helps to reduce potential delays in payment. Yet, despite the time savings this delegation provides, agencies are still self-registering contracts after their start date at an even greater rate than for M/WBE contracts that are registered by this Office.

Table 17: FY23 M/WBE NCSP Method Registrations by Retroactive Category, Citywide

| Retroactive Category | # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts | Total Contract Value | % Share of Contract Value |

| On Time or Early | 314 | 30.13% | $56,981,117 | 29.44% |

| Late – Within 30 Days | 320 | 30.71% | $56,108,648 | 28.99% |

| Later – Between 31-180 Days | 359 | 34.45% | $71,551,726 | 36.97% |

| Very Late – Between 181-365 Days | 38 | 3.65% | $7,239,413 | 3.74% |

| Latest – More than 1-Year | 11 | 1.06% | $1,683,132 | 0.87% |

| Grand Total | 1,042 | 100.00% | $193,564,035 | 100.00% |

Table 18: FY23 Volume of Retroactive M/WBE Contracts, by Award Method

| Award Method | # of Contracts | % of contracts are registered late |

| NCSP | 1,042 | 69.87% |

| CSB | 150 | 45.33% |

| CSP | 81 | 71.60% |

| Innovative | 2 | 50% |

| Negotiated Acquisition | 41 | 95.12% |

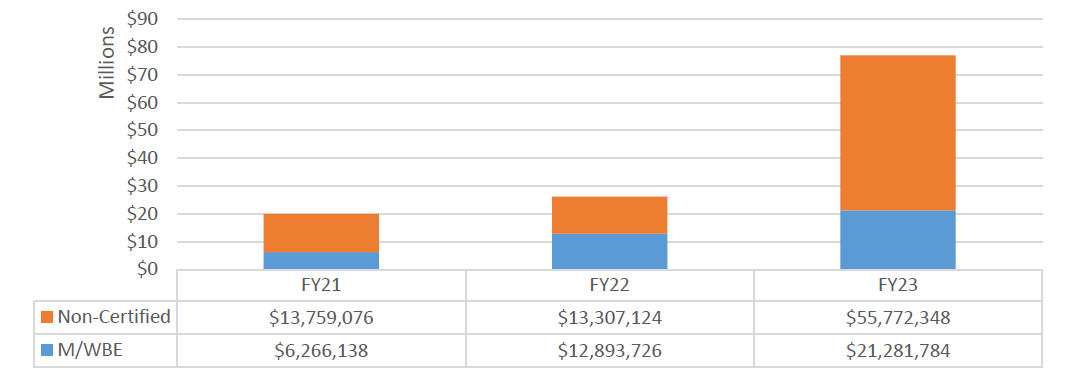

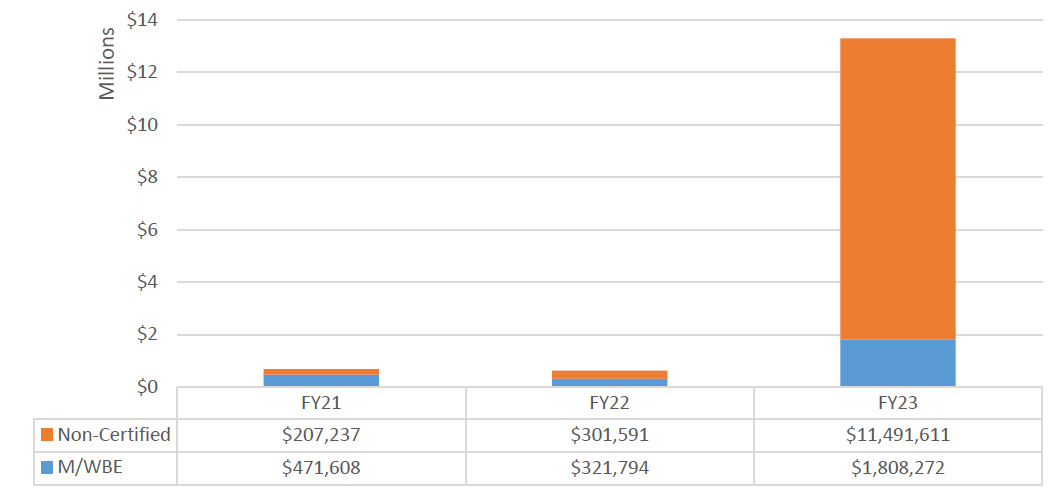

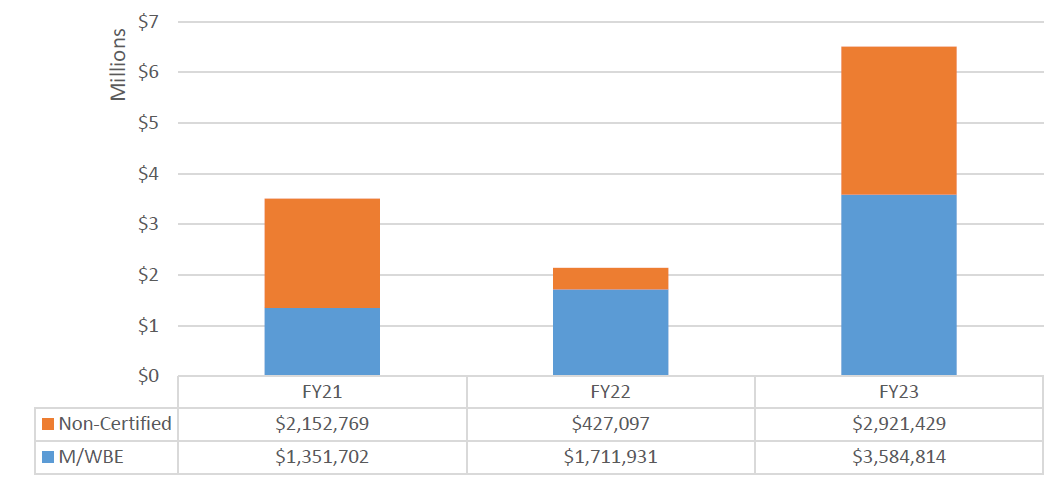

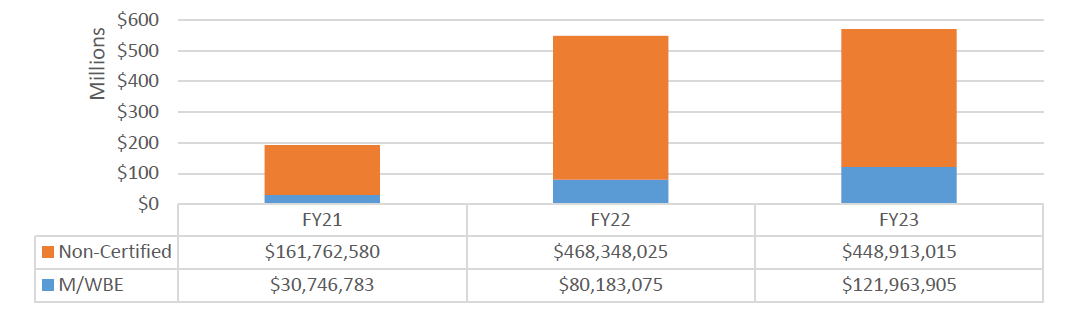

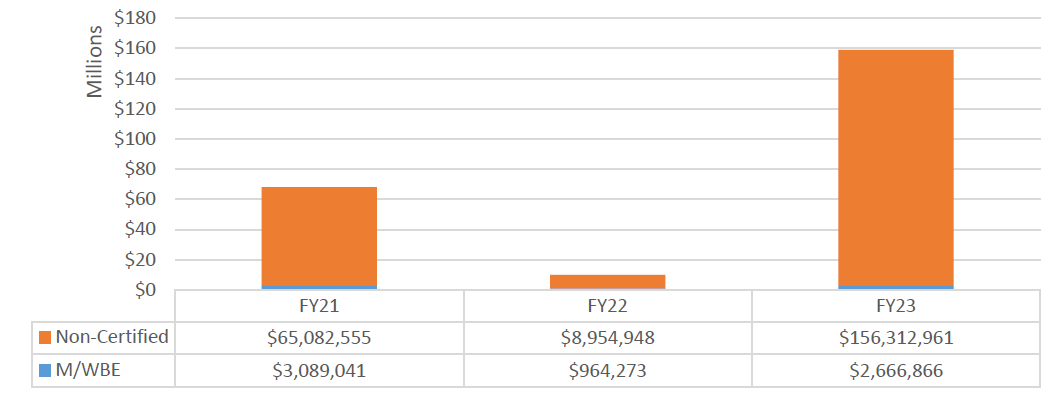

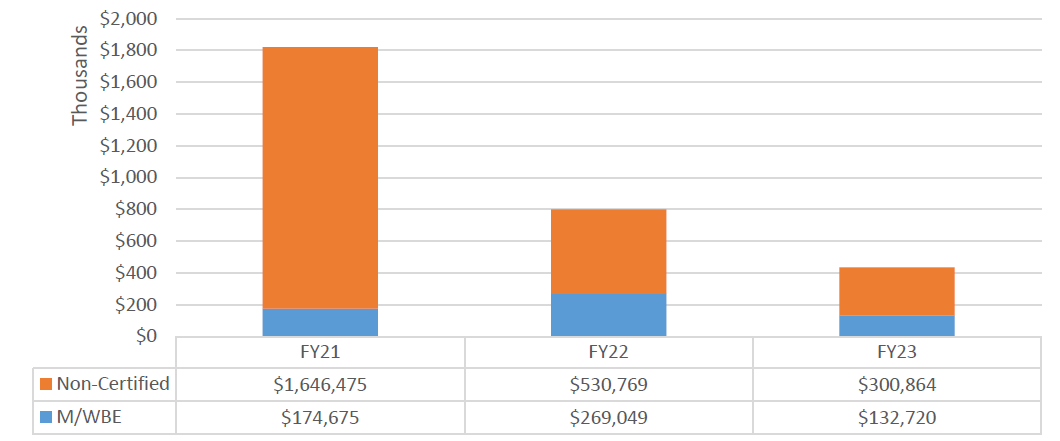

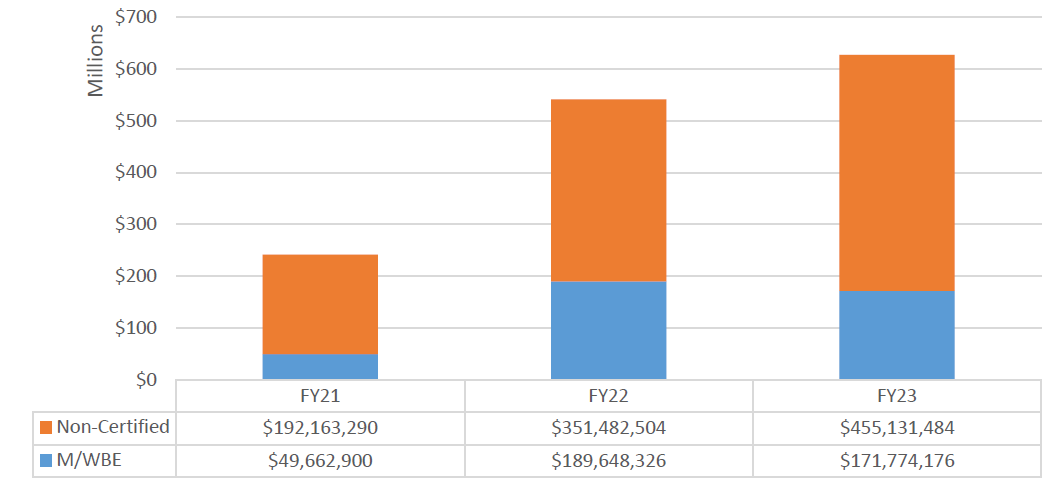

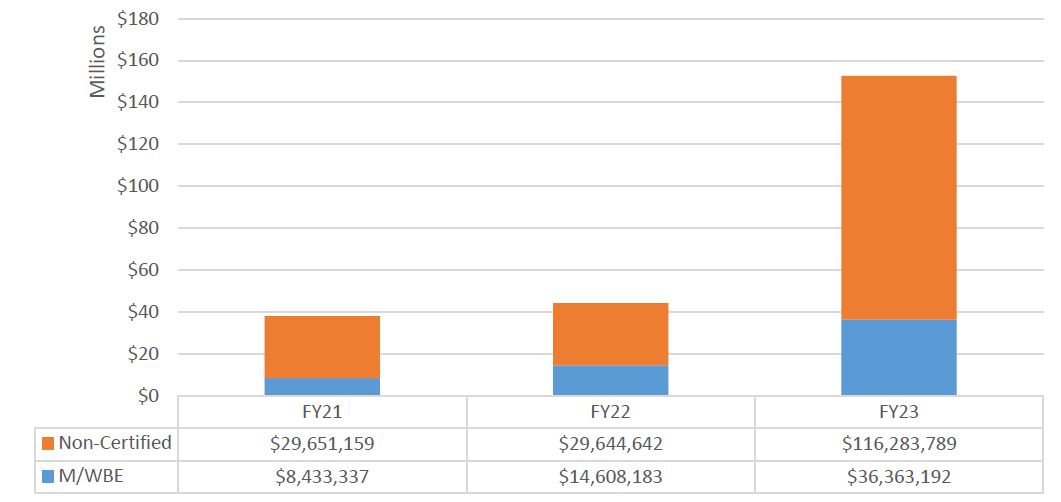

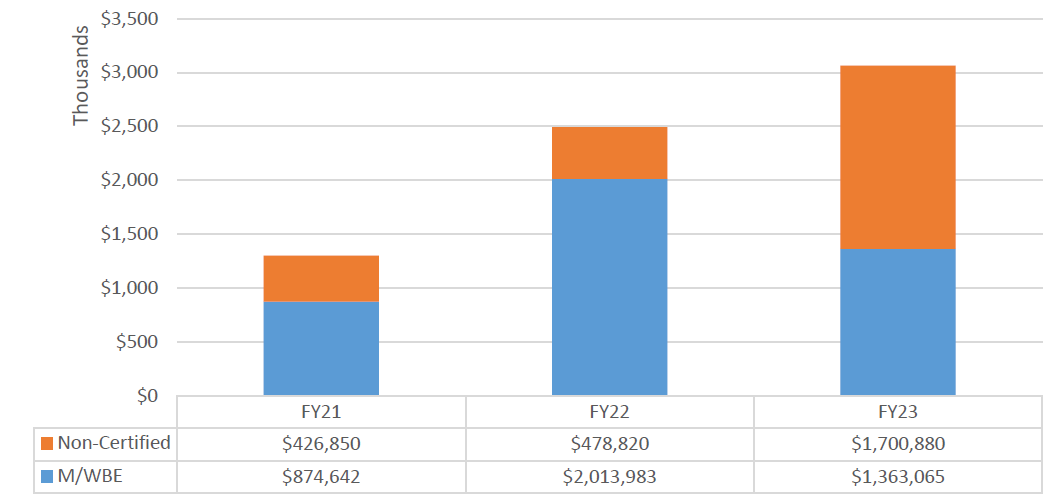

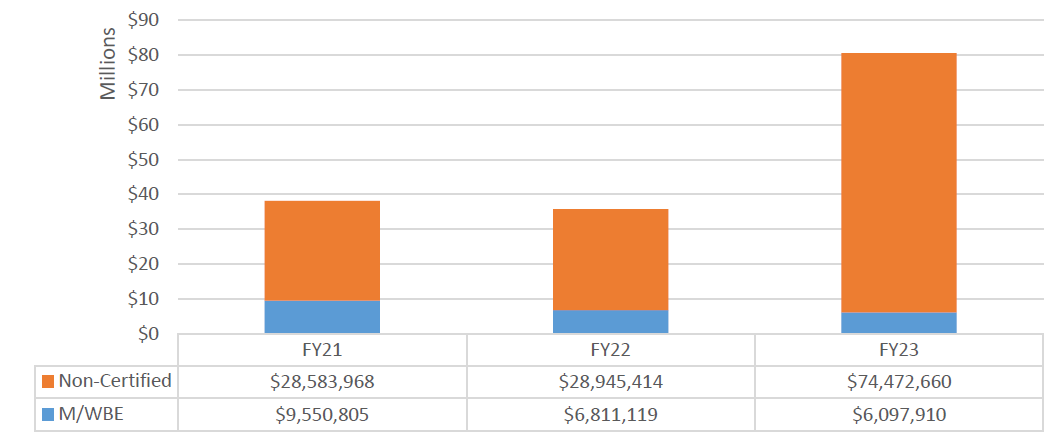

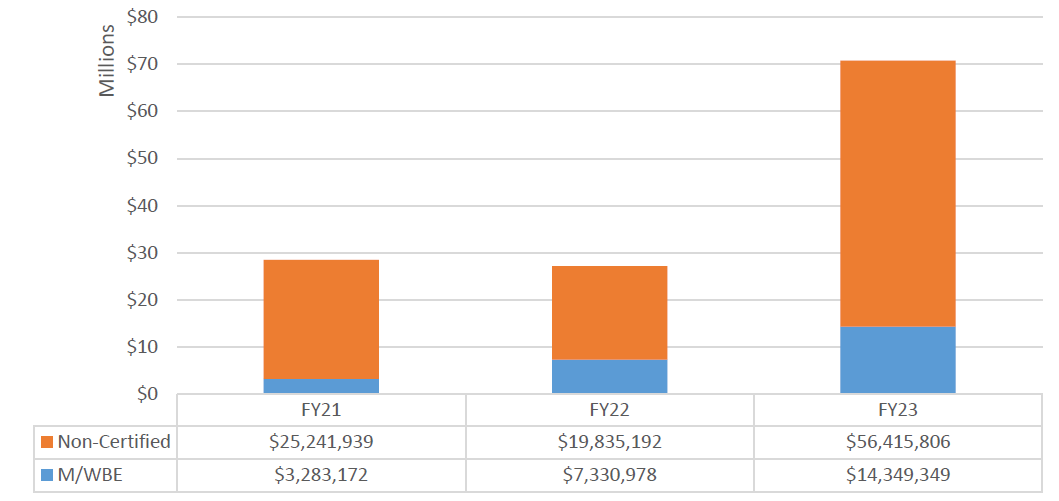

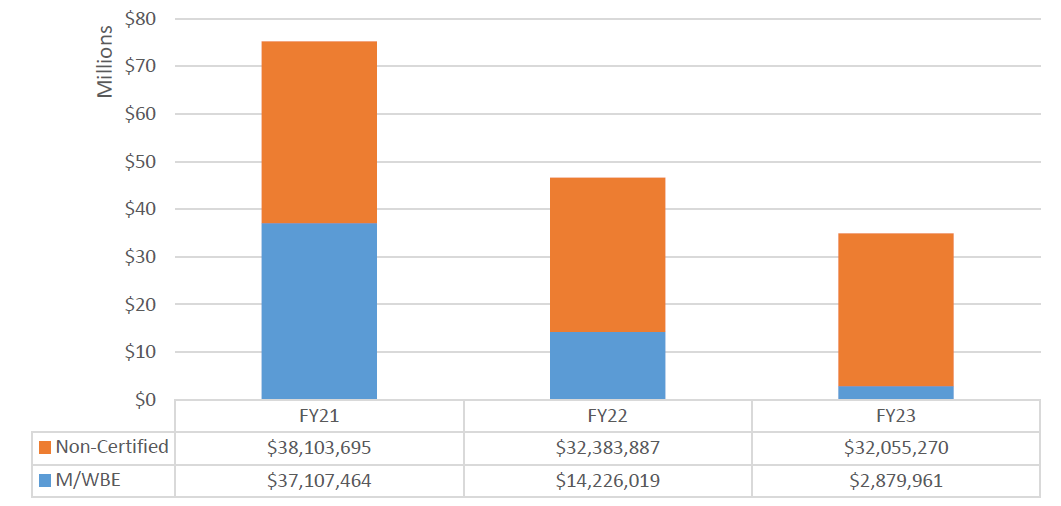

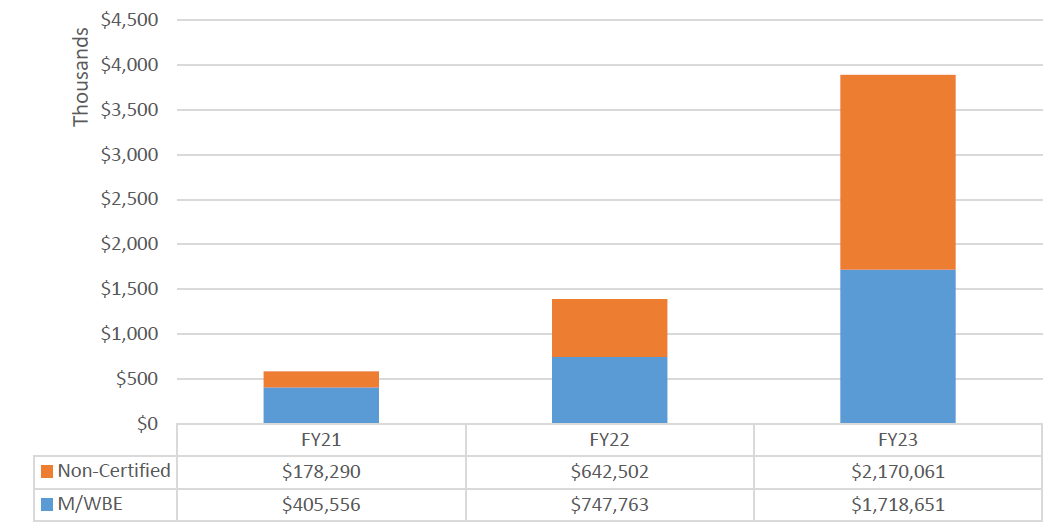

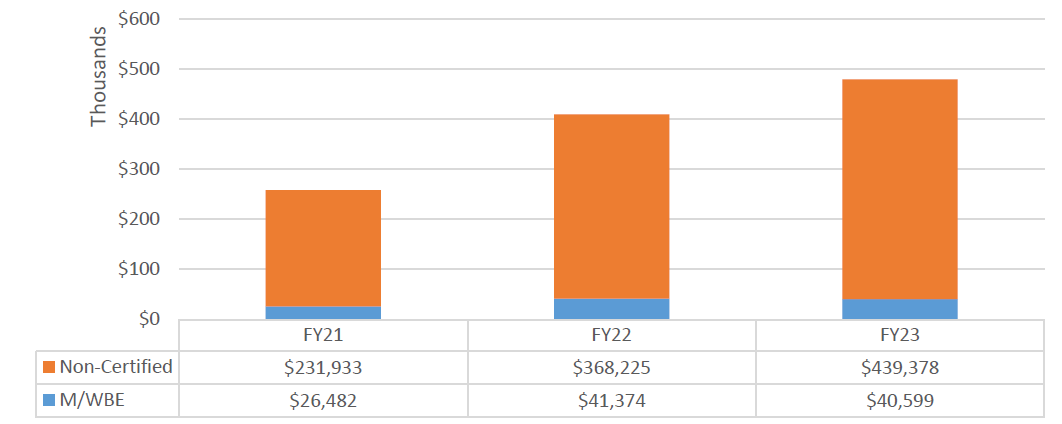

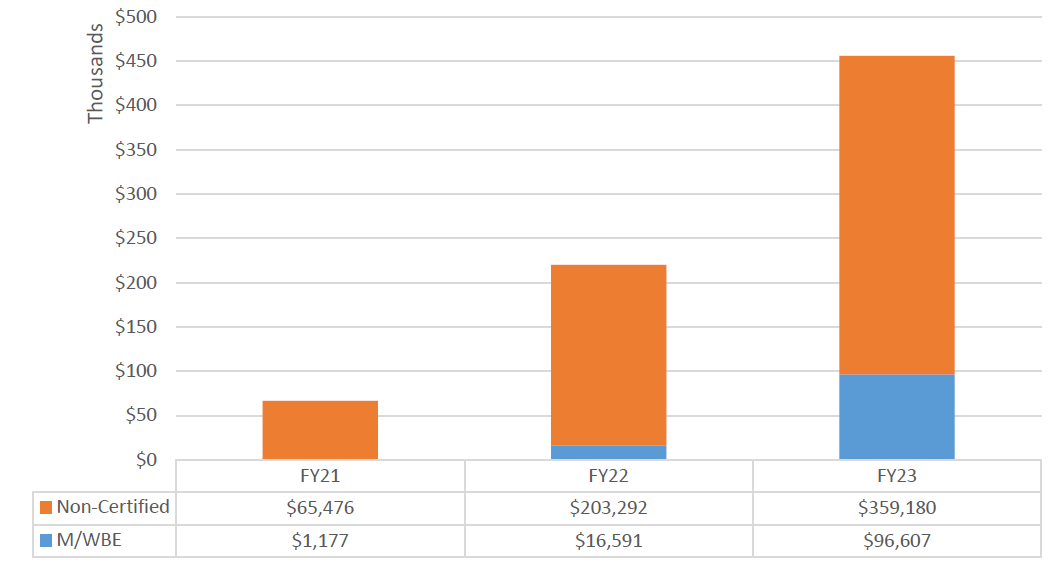

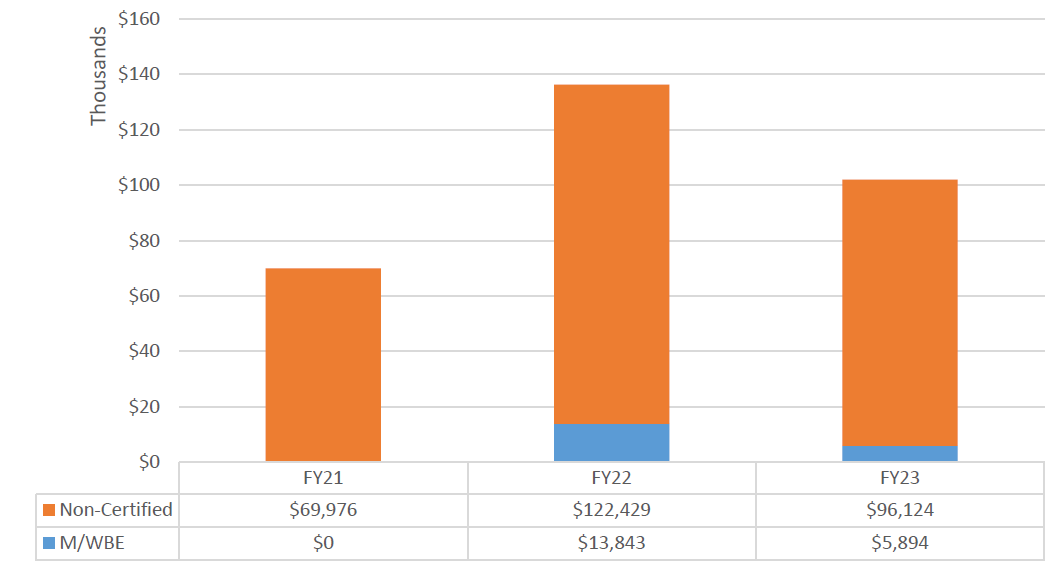

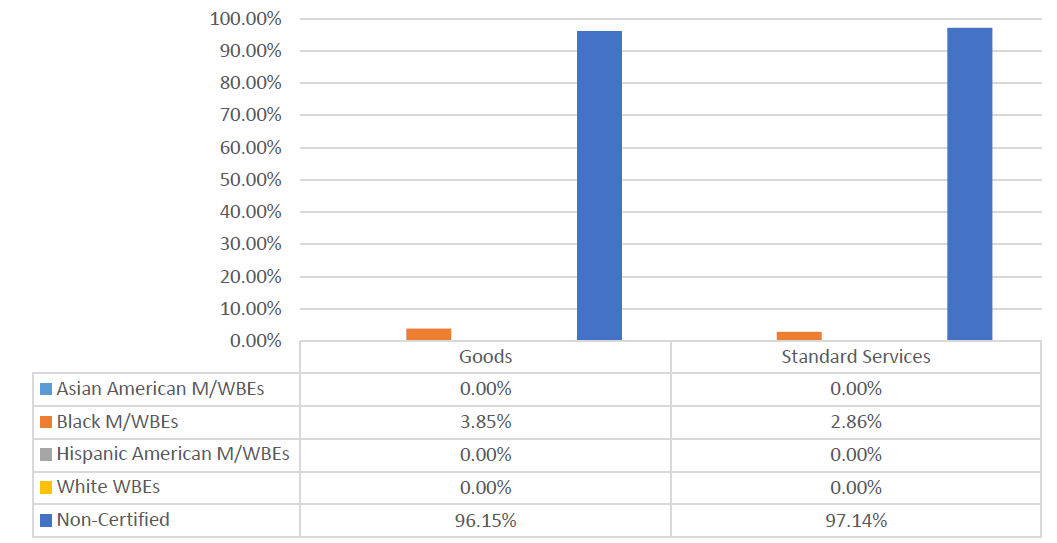

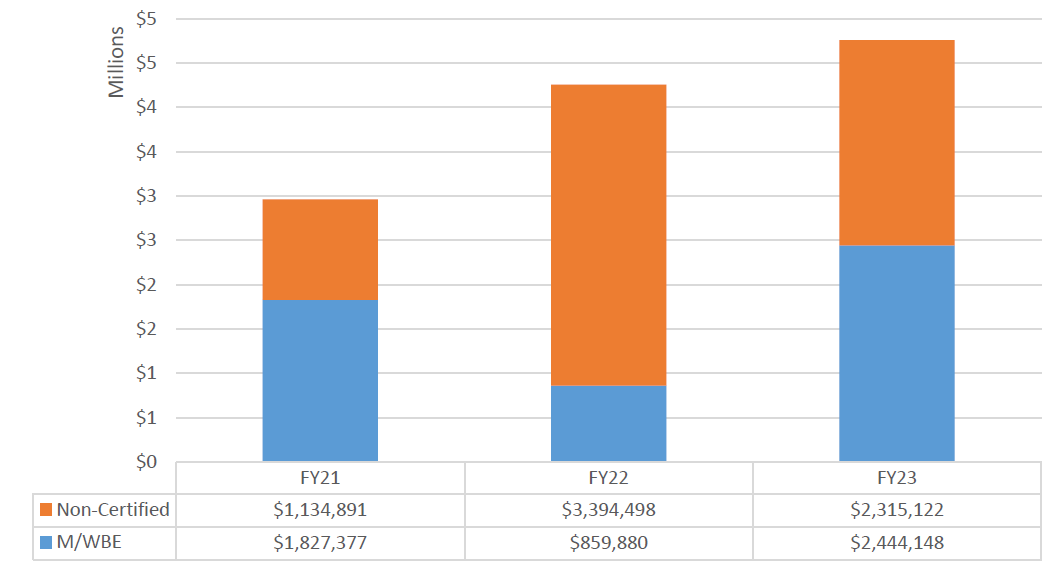

Specialized Focus: Department of Education

In prior years, the Department of Education (“DOE”), which is not a mayoral agency, was not subject to LL 174 participation goals. However, in 2023 the DOE’s Panel for Education Policy approved changes to their Procurement Policy and Procedures (“PPP”) that require the DOE to implement a M/WBE goals program consistent with LL 174. FY23 is the first fiscal year in which these new procurement Rules were legally effective. As such, and given that DOE has the largest procurement portfolio in the City, this year’s Report includes a focused analysis on its M/WBE utilization and compliance with LL 174. This Office is not able to fully assess the DOE’s compliance with M/WBE goals, as DOE failed to record any subcontract records in PIP at the time data for this Report was pulled.[42]

Table 19: Volume of DOE Contracts and POs Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, FY21-23 (DOE ONLY)

| FY21 | FY22 | FY23 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certification Type | # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts | # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts | # of Contracts | % Share of Contracts |

| M/WBE | 3,780 | 7.30% | 5,690 | 7.03% | 8,382 | 8.92% |

| Non-Certified | 47,967 | 92.70% | 75,296 | 92.97% | 85,560 | 91.08% |

| Grand Total | 51,747 | 100.00% | 80,986 | 100.00% | 93,942 | 100.00% |

52.36% of the DOE LL 174-eligible value in FY23 (for both M/WBEs and Non-Certified vendors) was from master agreements (MA1s). The largest of these contracts, accounting for nearly half of the value going to M/WBEs in FY23, was a $58.84 million agreement to Pro Con Group Inc. for the installation, repair, and replacement of steel doors for buildings under the DOE’s jurisdiction.[43] As of January 2023, nearly a full year into its five-year term, only $374,000 of this contract’s value has been expended.

Table 20: Value of DOE Contracts and POs Subject to LL 174 Participation Goals, FY21-23 (DOE ONLY)

| FY21 | FY22 | FY23 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certification Type | Total Registered Value | % Share of Value | Total Registered Value | % Share of Value | Total Registered Value | % Share of Value |

| M/WBE | $30,746,783 | 15.97% | $80,183,075 | 14.62% | $121,963,905 | 21.36% |

| Non-Certified | $161,762,580 | 84.03% | $468,348,025 | 85.38% | $448,913,015 | 78.64% |

| Grand Total | $192,509,362 | 100.00% | $548,531,100 | 100.00% | $570,876,920 | 100.00% |

Findings

In addition to the year-over-year analyses that develop an understanding of the Current State of M/WBE utilization, this Report has also undertaken additional targeted analyses to identify specific areas of focus.

Finding #1: Existing City tools don’t do enough to connect agencies and M/WBEs

There were over 147,000 prime contract and PO opportunities and over 2,000 subcontracting opportunities subject to M/WBE participation goals in FY23, yet only 2,242 M/WBEs ended up with a registered contract, PO, or subcontract. There are thousands of businesses that go through the time- and resource-intensive process to become M/WBE-certified that never see a dollar of City funded contracts for the goods or services they provide—even if the City purchases that same good or service. The City is not doing enough to connect M/WBEs to the right agencies, and vice versa.

1.1 There is not one centralized place to see planned procurement opportunities

The City’s contracting is managed across dozens of different Agencies, mayoral Offices, and handfuls of non-mayoral Elected Officials. As such, M/WBEs struggle to figure out when and which agencies purchase the types of goods and services that they can offer. Yet M/WBEs are encouraged and expected to create and manage relationships with procurement officials across this complicated web. Without setting a clearer, easier path, M/WBEs remain disconnected from the City agencies that need them to provide critical goods and services and support the growth of M/WBE utilization. The City should do more to help connect M/WBEs to the agencies who are looking for them.

Although in some circumstances City agencies are already required to publish lists of their planned contracting opportunities for each fiscal year, navigating across the lists is tedious, and it would take anyone hours to comb through hundreds of discrete spreadsheets across many dozen websites:

- M/WBE Procurement Plans: Pursuant to Administrative Code §6-129(g), for each upcoming fiscal year the City publishes an annual plan for each agency that details the anticipated contracting opportunities that are subject to M/WBE participation goals. Although the plans include information that may help an M/WBE find a relevant procurement opportunity (e.g., description of services/goods, procurement method, and industry), MOCS publishes this information in a discrete file for each of the 32 represented Agencies. These Plans are not available in PASSPort, the procurement sourcing tool that all vendors are encouraged to use to connect with relevant procurement opportunities, adding layers to the cumbersome search. Furthermore, these plans are published only once annually, therefore are not reflective of any new opportunities that develop during the course of the year.

- Annual Contracting Plans: Local Law 63 (“LL 63”) amended §312(a) of the City Charter in 2011 and requires that the Mayor, through MOCS, publishes an Annual Contracting Plan and schedule for standard and professional services contracts valued above $200,000. These Annual Contracting Plans offer a baseline of anticipated procurement opportunities and can be a helpful resource for M/WBEs who offer these types of services. However, as with the M/WBE Plans, MOCS also publishes each agency’s Annual Contracting Plans as a discrete Excel file. Unlike the M/WBE Plans, amendments to Agency Plans are required to be posted, and appear as yet another separate file. To put this in perspective, to review the FY24 Citywide procurement standard and professional services opportunities, an M/WBE must manually review thousands of rows of data across 105 unique files.

- Human Services Plans: The City also publishes annual plans for human services agencies that set forth agencies’ anticipated human services procurement actions for the fiscal year. Although human services contracts are exempt from LL 174 M/WBE participation goals, these Plans are helpful to M/WBEs that may be capable of providing the service as a prime or to pursue contracting as a subcontractor to the prime vendor. Once again, MOCS publishes two discrete files for each human services agency, requiring vendors to review 20 individual spreadsheets just to understand the portfolio of these opportunities.

In all, these Plans (which do not even cover non-mayoral agencies or certain goods and construction procurements) run counter to their intended goal to help facilitate the transparency of City contracting opportunities. Navigating the City’s contracting processes is difficult enough and M/WBEs should not be expected to encounter challenges with first even understanding the procurement ecosystem.

1.2 Commodity codes are ineffective in linking M/WBEs and agencies

Agencies rely on the SBS Directory to find eligible M/WBEs to target their outreach. They primarily search for M/WBEs using a commodity code. A commodity code is a standardized number for a product or service that a vendor might offer to the City. Commodity codes are national, standardized indices used across many municipalities and are not unique to New York City. City procurement portals PASSPort and FMS also rely on commodity codes as the basis for alerting vendors about relevant open procurement opportunities.

Commodity codes are often too general and cast too wide of a net, leading to challenges for agencies to find M/WBEs that are truly capable of providing the goods or services that are being procured. Other times, commodity codes may be so narrow that they incidentally fail to include M/WBEs in the procurement competition pools for goods and services they are able to provide. Furthermore, the sheer volume of commodity codes is unruly. The New York City Commodity Code Listing offers thousands upon thousands of code options across 250 main categories, amassing 161 pages. While maybe helpful at some time, the Listing includes a column that indicates whether the Commodity Code was used on a New York City contract or purchase order “in the recent past”– but the document has not been updated in over a decade.

Furthermore, the Commodity Codes available for M/WBEs to select for their PASSPort accounts are different than the Codes available to them in their SBS Directory Vendor Profile.

M/WBEs are set up to fail if one of their essential links to learn about procurement opportunities is as cumbersome and convoluted as selecting the appropriate Commodity Codes.

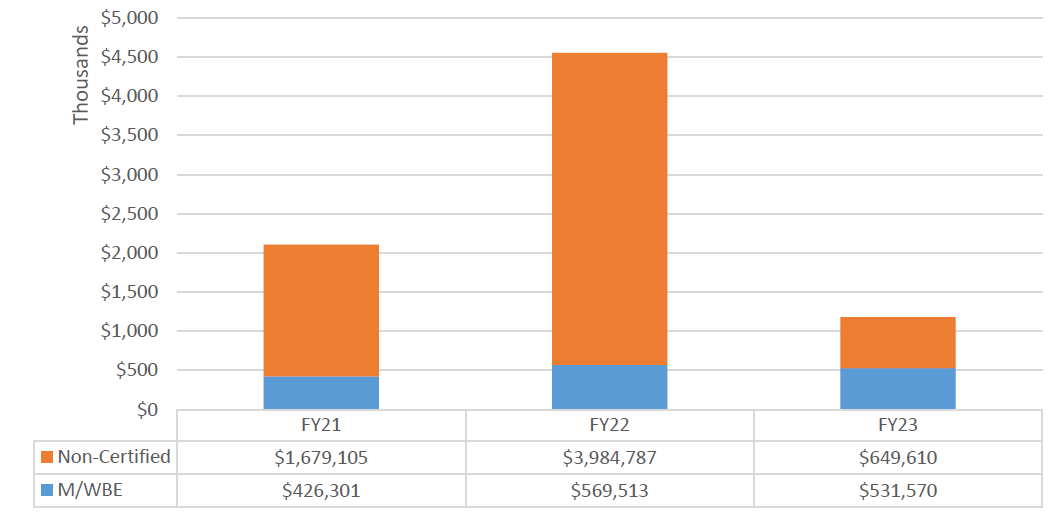

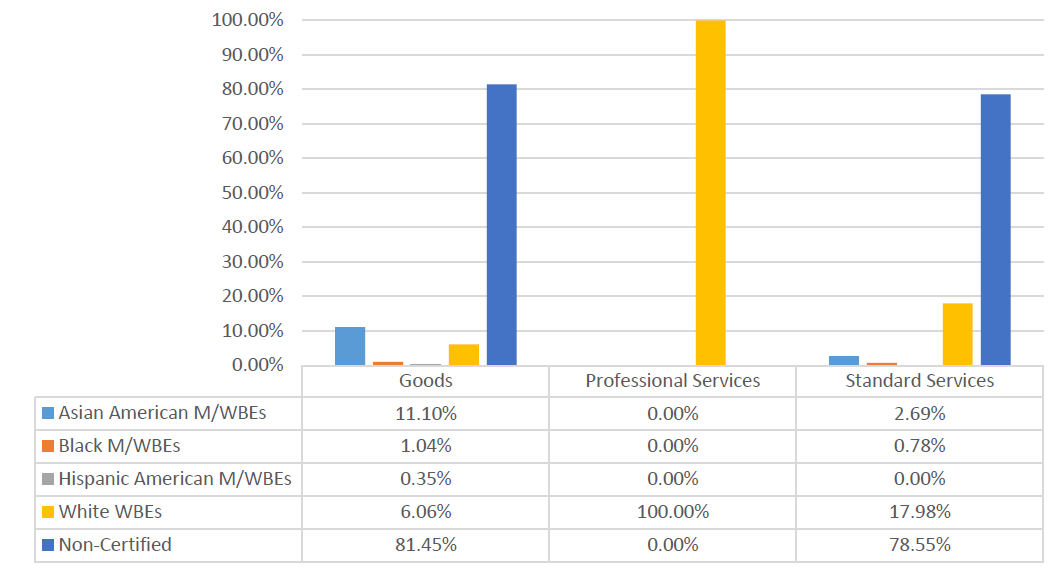

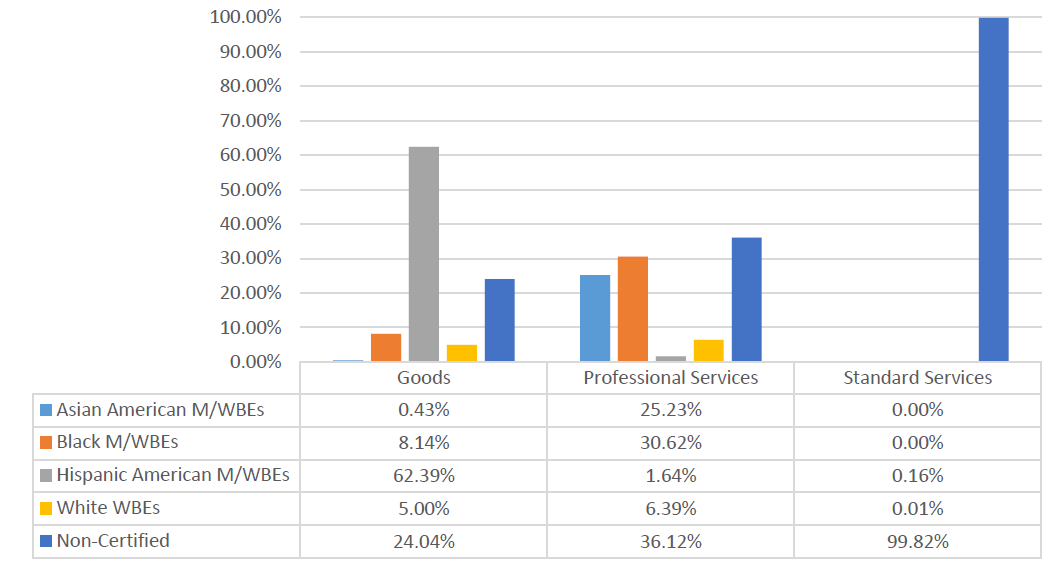

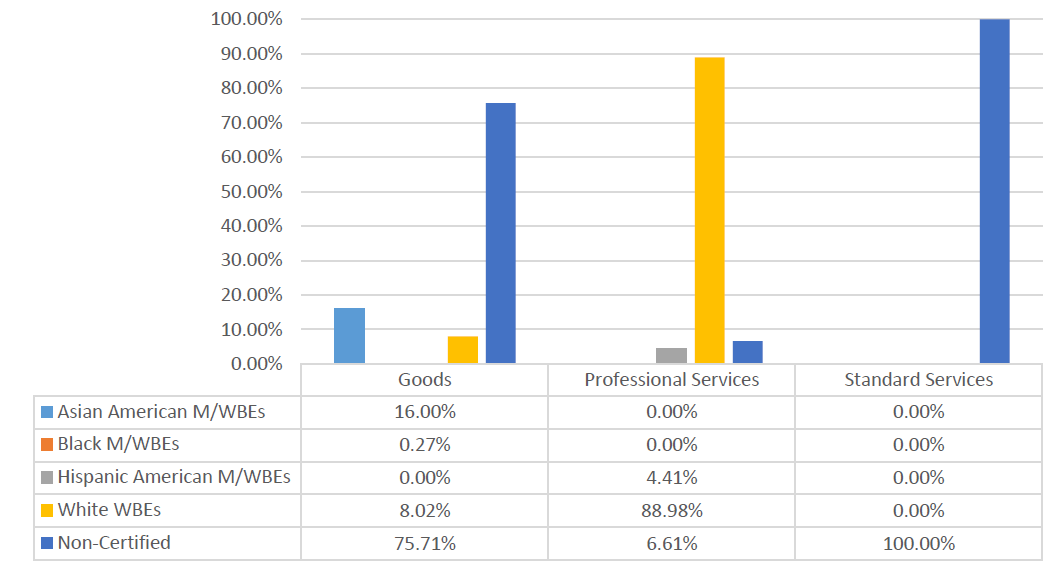

Finding #2: Agencies are not taking advantage of the increased M/WBE NCSP method threshold

The M/WBE NCSP method has a threshold that is significantly higher than those for micro- and small purchases and should be one of the City’s most effective tools in driving prime contract awards to M/WBEs.[44] This Office has been closely monitoring the use of this method, as it makes up a significant share of new contract registrations for M/WBEs (36.36% in FY23). In FY23 city agencies registered 1,042 contracts via the M/WBE NCSP method, valued at over $193 million.[45] Despite being able to use this method up to $500,000 (or $1 million at some points of the year), the average value of a contract registered using this method was merely $185,762.[46]

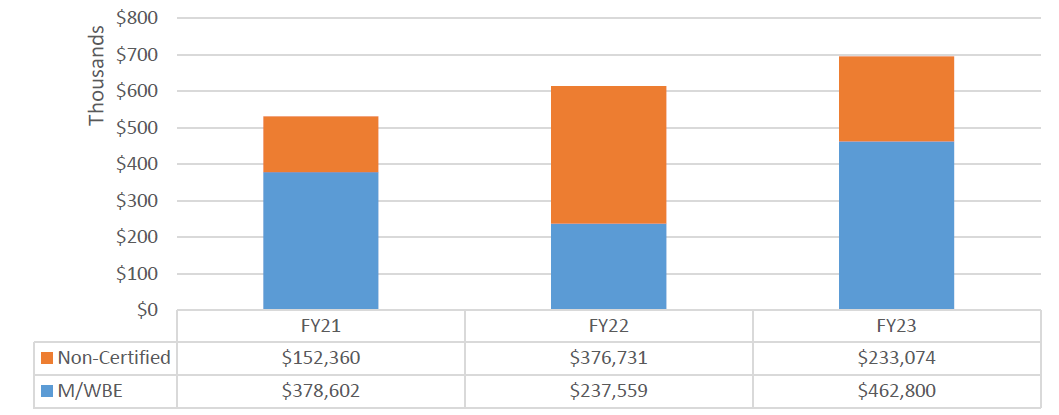

Table 21: Contracts Registered via M/WBE NCSP Method, Citywide, FY21-23

| Fiscal Year | # of M/WBE NCSP Registrations | NCSP % Share of All M/WBE Registrations | Total Value of M/WBE NCSPs | AVG Contract Value of M/WBE NCSP |

| FY21 | 814 | 38.80% | $85,565,524 | $105,117 |

| FY22 | 928 | 33.29% | $124,946,120 | $134,640 |

| FY23 | 1,042 | 36.36% | $193,564,035 | $185,762 |

| Grand Total | 2,784 | 35.91% | $404,075,679 | $145,142 |

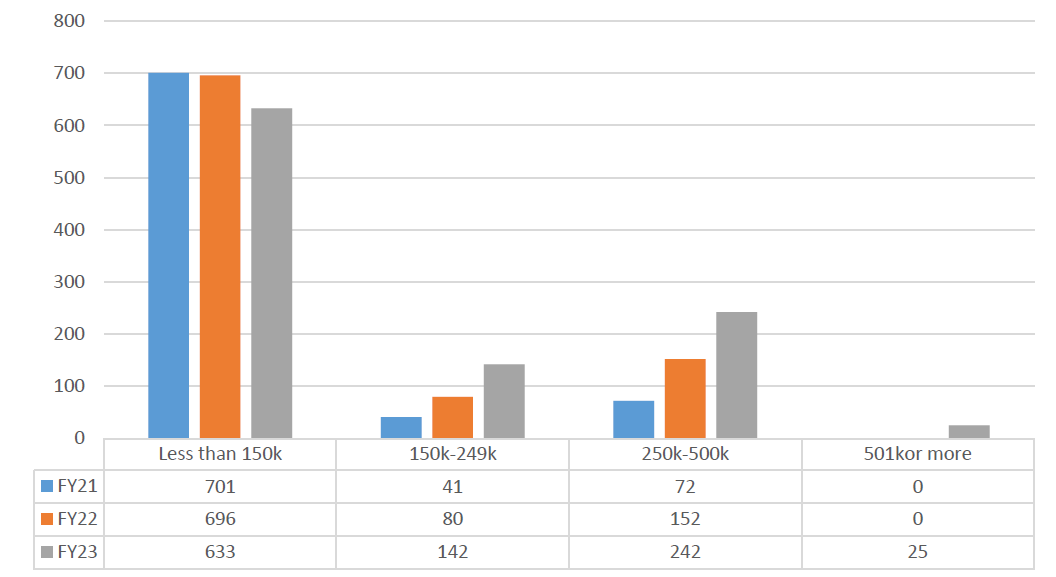

In FY23, city agencies used the M/WBE NCSP method more, and for a slightly higher individual contract total value, than in prior fiscal years. However, FY23 registration data illustrates that many agencies focused their use of this method at values far below the maximum threshold. In FY23, 74.38% of contracts registered using this method were below $250,000, at least half of the maximum value permitted by the Rule[47]. Only 25 contracts registered using this method in FY23 were valued over $500,000[48]. Nearly two thirds (60.75%) of the contracts registered using this method did not exceed $150,000, the initial cap set back in 2017 and which is only $50,000 more than the Small Purchase method, which already has latitude for discretion to award to M/WBEs.

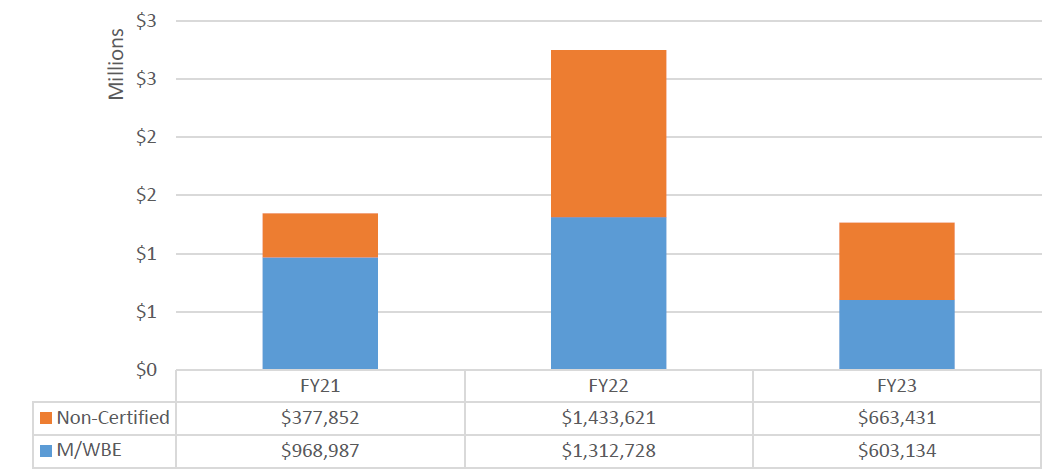

Chart 8: Volume of Contracts Registered via M/WBE NCSP Method, Citywide, FY21-FY23

Table 22: FY23 Value of Contracts Registered via M/WBE NCSP Method, Citywide, by M/WBE Category[49]

| Contract Value | Asian American | Black | Hispanic American | White WBE | Native American | Total | Percent |

| Less Than $150K | 161 | 168 | 184 | 117 | 3 | 633 | 60.64% |

| $150K – $250K | 42 | 36 | 33 | 31 | 0 | 142 | 13.67% |

| $250K – $500K | 69 | 50 | 35 | 31 | 0 | 185 | 17.81% |

| $500K – $1M | 19 | 28 | 7 | 28 | 0 | 82 | 7.89% |

| Grand Total | 291 | 282 | 259 | 207 | 3 | 1,042 | 100% |

Compared to Citywide registration data, agencies’ use of the M/WBE NCSP method in FY23 was more evenly distributed across M/WBE categories. However, within Black and Hispanic American M/WBEs, male-owned firms represent much larger shares of the counts of registered contracts then woman-owned firms. The City only registered 3 contracts total to male-owned Native American MBEs in FY23. All three of these contracts were registered through the M/WBE NCSP method.

A disaggregated analysis of the average value of contracts registered using this method reveals similar disparities as average value analyses of all award methods – the average value of contracts registered to Asian American male-owned MBEs and White woman-owned WBEs are higher than those of other underrepresented M/WBE categories.

Table 23: FY23 Contracts Registered via the M/WBE NCSP Method, Citywide, by M/WBE Category

| M/WBE Category | # of NCSP Contracts | NCSP Share of Total M/WBE Category Registrations | Percent of All M/WBE NCSP Registrations | AVG M/WBE NCSP Value |

| Asian American male-owned MBEs | 135 | 28.07% | 12.96% | $229,888 |

| Asian American women-owned MBEs | 156 | 54.17% | 14.97% | $184,976 |

| Black male-owned MBEs | 208 | 46.53% | 19.96% | $186,890 |

| Black women-owned MBEs | 74 | 24.67% | 7.10% | $189,982 |

| Hispanic American male-owned MBEs | 208 | 47.71% | 19.96% | $138,722 |

| Hispanic American women-owned MBEs | 51 | 40.48% | 4.89% | $158,901 |

| Native American male-owned MBEs | 3 | 100.00% | 0.29% | $47,572 |

| White WBEs | 207 | 26.37% | 19.86% | $210,822 |

| Grand Total | 1,042 | N/A | 100% | 168,469 |

This Office will continue to closely monitor the citywide use of this method to ensure that it is being utilized to the maximum extent possible to direct high dollar-value contracts and take affirmative steps to eliminate bias and the underutilization of certain M/WBE groups. As one of the conditions for delegating agencies the ability to self-register contracts awarded pursuant to this method, this Office mandated additional oversight and reporting requirements aimed at ensuring that agencies are using the threshold to its fullest potential. As of this calendar year, the City must publish quarterly reports that set forth its review of 10% of new or modified contract awards that were made pursuant to other methods even though they were otherwise eligible to be made via the discretionary method or at its fullest capacity. The analysis will highlight whether agencies are strategically reviewing procurement portfolios and identifying all potential opportunities for use of the method. In instances where agencies have failed to maximize the use of the NCSP, MOCS and OM/WBE must identify the reasons for its lack of utilization and either address systemic roadblocks and/or develop enhanced training. Similarly, this Office will use the information to determine whether the delegation of registration authority remains appropriate.

Along with City and private sector partners on the Capital Process Reform Taskforce, this Office advocated for State legislation to further increase the NCSP threshold. As of December 2023, and due to proactive measures taken by the PPB of which this Office is a voting member, the City now has the ability to use the method for eligible procurements that do not exceed $1.5 million. Therefore, these recommends are especially important moving forward to position agencies to most effectively utilize the increased threshold.

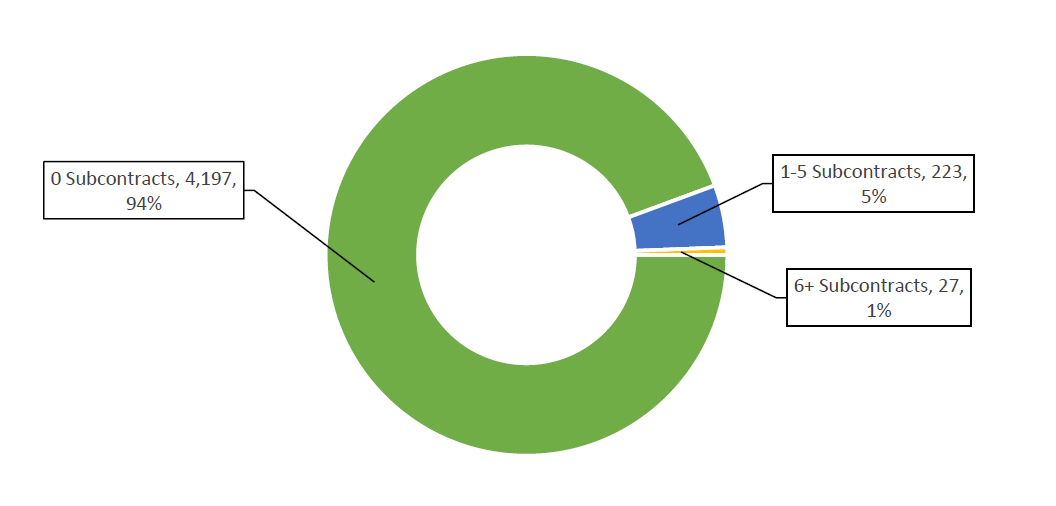

Finding #3: Master Agreements awarded to M/WBEs are not used anywhere near capacity

Multiple Master Agreements (MMA1s) are a class of contracts used by agencies to establish a pool of prime vendors that can be kept “on call” to provide services on an as-needed basis. The actual utilization of the contract is processed through a task order, which is separately registered with this Office. The City’s use of this framework is warranted when the City anticipates regularly needing a particular contracted service, but the level to which it may be needed is unclear. MMA1s are commonly used for as-needed legal services or managerial or IT consulting services. This framework is more efficient than the processing of individual, months-long procurements. MMA1s are generally awarded to multiple vendors, and task orders may be issued through either a “mini-bid/proposal” competition or on a rotational basis.

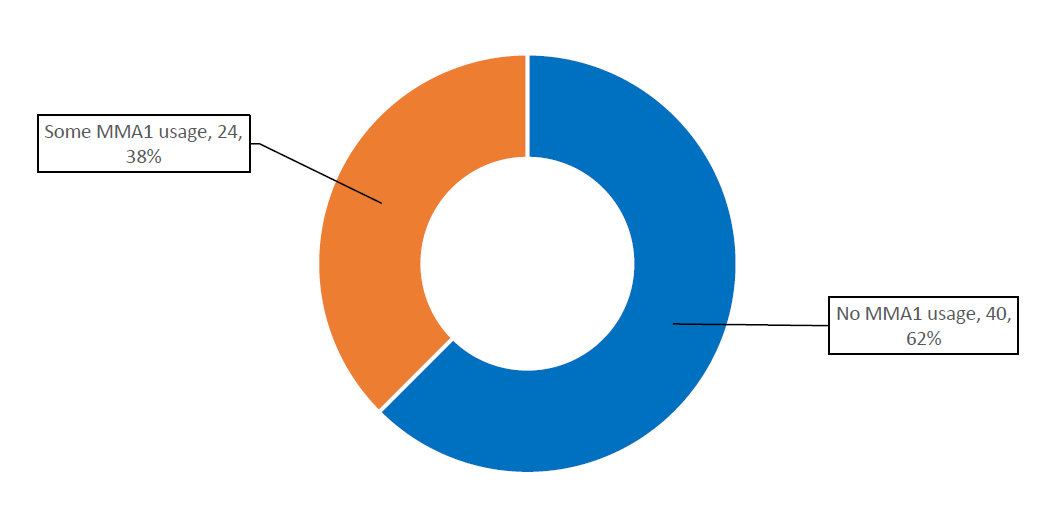

Given the unknown need, MMA1s typically establish a high maximum value capacity. As such, it is common for MMA1s to be underused relative to their maximum value capacity, or not used at all. The LL 174-mandated M/WBE utilization reports that are released by MOCS and SBS rely solely on contract award data to determine utilization and MMA1s awarded to M/WBEs are counted as awards valued at the maximum value capacity. However, more detailed analysis reveals the actual truth –despite both large volumes and values of MMA1 contracts registered to M/WBEs, these contracts are less likely to be used than those registered to their non-certified counterparts and in many instances result in no utilization at all.

It is important to take a closer look to understand how these underused MMA1 contracts may be incidentally misrepresenting actual M/WBE utilization. These analyses examine LL 174-eligible MMA1 contracts that were registered between FY16-FY23 (and have since expired) to best confirm final rates of use.[50] “Usage rate” is calculated by comparing the final value of a given MMA1 contract against the sum of funds issued against all corresponding task orders.[51]

M/WBE MMA1s were less likely to be utilized

Of the 625 MMA1 contracts in the specified dataset, less than 30% were registered to M/WBEs. The share of MMA1s that were not used (i.e. no task orders were issued, or no funds were issued against associated task orders) was 8% higher for contracts awarded to M/WBEs than their non-certified counterparts. The average value of these unused MMA1s was $6.32 million, resulting in over $485 million that was inaccurately reported toward M/WBE utilization totals.

Table 24: Usage of MMA1s, FY16-FY23

| Usage | # of MMA1s | % Share of MMA1s | Avg MMA1 Value | Total Original Contract Value |

| M/WBE | 178 | 28.48% | $8,016,322 | $1,306,139,752 |

| No Usage | 77 | 43.26% | $6,324,352 | $485,024,980 |

| Up to 33% Use | 56 | 31.46% | $8,468,027 | $448,196,994 |

| Between 33-66% Use | 15 | 8.43% | $7,068,701 | $93,024,638 |

| Between 66-99% Use | 30 | 16.85% | $11,989,675 | $279,893,140 |

| Non-Certified | 447 | 71.52% | $16,911,107 | $5,640,516,736 |

| No Usage | 158 | 35.35% | $6,356,666 | $1,064,953,252 |

| Up to 33% Use | 152 | 34.00% | $17,966,072 | $2,664,936,355 |

| Between 33-66% Use | 56 | 12.53% | $40,390,730 | $766,145,311 |

| Between 66-99% Use | 72 | 16.11% | $21,275,565 | $1,108,583,026 |

| 100% Use or More | 9 | 2.01% | $3,371,924 | $35,898,792 |

Table 25 examines LL 174-eligible MMA1 usage rates for contracts held by M/WBEs and Non-Certified vendors by agency. Agency-specific analyses show that OTI, DSS, and DCAS each utilized M/WBE MMA1s at higher rates than their Non-Certified counterparts.

Table 25: MMA1 Usage Rates by Agency

| M/WBE | Non-Certified | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agency | Total # of MMA1s | Average Usage Rate of MMA1 Contract | Total # of MMA1s | Average Usage Rate of MMA1 Contract |

| COMP | 0 | N/A | 6 | 4.02% |

| DCAS | 3 | 48.37% | 12 | 27.91% |

| DCP | 1 | 23.87% | 6 | 44.65% |

| DDC | 124 | 17.73% | 161 | 19.23% |

| DHS | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | N/A |

| DOC | 1 | 0.00% | 4 | 23.14% |

| DOT | 1 | 1.57% | 10 | 30.14% |

| DPR | 17 | 14.85% | 70 | 32.27% |

| DSS | 7 | 42.59% | 60 | 23.38% |

| FDNY | 1 | 0.00% | 0 | N/A |

| DOF | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2.07% |

| HHC | 0 | N/A | 1 | 0.00% |

| HPD | 0 | N/A | 2 | 100.00% |

| LAW | 0 | N/A | 2 | 57.03% |

| MAYOR | 2 | 0.00% | 35 | 10.43% |

| NYCEM | 2 | 4.00% | 8 | 32.23% |

| OTI | 18 | 50.12% | 68 | 33.33% |

M/WBE MMA1 Contract Value is Consolidated Among Fewer Vendors

Analyses found that half of M/WBEs awarded MMA1s saw little to no value from them. Of the 130 unique M/WBEs that were awarded LL 174-eligible MMA1s, 64 had only one such contract in the seven-year lookback period. Moreover, 40 of these contracts were totally unused, meaning that the awarded vendors never saw a dollar of their MMA1 contract value. Chart 9 provides a breakdown of contract usage among M/WBEs that were awarded a single MMA1.

Chart 9: Usage of Contracts Awarded to M/WBEs with One MMA1

While it is known that the maximum contract capacity for MMA1s may never be met, the City must be more transparent in its use of this MMA1 structure. M/WBEs are required to dedicate a lot of time and valuable resources to respond to procurement opportunities (and if successful, to manage the award and contract execution processes). Similarly, resource-strapped agencies expend significant time on reviewing proposals and processing contracts through the City’s complicated procurement processes. In the interest of targeting resources to results that add value, agencies should be more mindful of establishing MMA1 contracts with measure. To do otherwise not only wastes resources, but also gives M/WBEs the false hope of ever receiving true dollars from the City.

Unused MMA1 contracts also give the City the unfair benefit of claiming utilization that is not in fact real. Unused MMA1s impact the City’s data by overinflating utilization figures, focusing attention away from areas of City contracting that continue to be unsuccessful in getting real dollars to M/WBEs. More effective and efficient use of these contracts is necessary to ensure that the City’s projections and planning for M/WBE utilization more accurately reflect the reality of the contracts’ impact.

Finding #4: Goal-setting oversight is insufficient for contract changes and modifications

Last year’s Report discussed the gaps in the City’s ability to effectively monitor participation goals set on prime contracts. As a result, the City is not only unable to assess compliance with the requirements set forth in LL 174, but it also is unable to measure the utilization of M/WBEs at the subcontract level where most participation goals are set to be achieved. The City has failed to address several findings included in that Report—the goal-setting process remains onerous, the subcontractor tracking system has not been digitized for transparency, and reporting processes remain paper-based–all of which remain a barrier for meaningful M/WBE utilization.

This lack of oversight is exacerbated for certain contract changes and modifications subject to LL 174 participation goals. While not as visible as prime contracts, these contract management actions are additional avenues by which the City spend money. As such, the City must ensure it is fully examining and taking advantage of ways to maximize getting dollars to M/WBEs in these areas.

Contract changes (such as amendments and construction change orders) occur after the initial solicitation and procurement of a prime contract and are triggered by a need for new, additional scope. This additional scope typically results in adding more value to the prime contract. However, by the time changes are issued, the original contract M/WBE participation goal is no longer sufficient, as the market and contract value may have changed. Yet goal-setting at the time of contract modification is not enforced or a standard part of the change process. This is a missed opportunity to assess whether the original goal remains suitable. Revised goals could also refocus attention to address disparities among M/WBE Categories.

In some circumstances, the practice of adjusting goals at the time of contract modification is not at an agency’s discretion. LL 174 requires agencies to review “the scope of work for the contract, and the scale and types of work involved” for any change order which exceeds the greater of ten percent of the contract or $500,00 to determine whether a participation goal should be modified[52]. However, there are no checks and balances currently in place to ensure that agencies comply with this requirement. This impacts many contracts – in FY22 alone, the City registered 1,748 value-associated modifications.

There are similar compliance concerns for task or work orders associated with eligible master agreements, some of which are discussed in Finding #3 of this Report. Because the scope of the work is unknown at the time of the procurement of the prime contract (and work is not, in fact, guaranteed), LL 174 requires that M/WBE participation goals be set on any issued task orders. Task order goals compliance is difficult to evaluate and enforce because task orders are not generally subject to most City oversight reviews. City systems provide limited insight into participation goals on individual task orders, so there is inconsistency in how goals are set by different agencies against the same (or similar) master agreements. This issue becomes compounded with master agreements used by multiple agencies that do not have one central agency responsible for management.

Recommendations

Recommendation #1: Streamline connections between M/WBEs and Agencies

1.1 Create one repository of current and planned procurement opportunities